1. Introduction

Liver tumors rank as the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) representing the most prevalent form. HCC is frequently diagnosed at advanced stages, underscoring the critical need for early detection strategies. The five-year survival rate correlates strongly with disease stage, dropping to ≤20% in late-stage cases [

1]. Major risk factors for HCC include:

Liver cirrhosis (viral hepatitis B/C-induced, alcoholic/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis) [

2].

Genetic disorders (alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, tyrosinemia, hemochromatosis) [

3,

4].

Toxic liver injury (e.g., steroid hormone drugs) [

3].

Fatty liver disease (alcoholic or non-alcoholic, with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) driving a global rise in HCC incidence [

5,

6,

7].

Currently, in clinical practice, a tumor-specific marker, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), is used for screening risk groups, disease progression, and survival prognosis. The alpha-fetoprotein test proposed in 1964 to detect serum fractions of embryonic alpha-globulins as a diagnostic marker of HCC is still used in clinical practice [

8,

9,

10]. AFP remains a widely used biomarker due to its low cost, ease of measurement, and wide availability. It should be noted that its sensitivity and specificity it is insufficient for both early diagnosis and widespread screening. In this regard, it is important to search for new, more specific and sensitive markers, including proteins whose content increases or decreases in the tumor. A feature of a significant part of human proteins is their existence in several or many modifications — proteoforms. For example, the above-mentioned AFP exists in several variants of glycosylated forms (proteoforms). And the tests measuring the fucosylated form of AFP (AFP-L3) used in clinical practice show greater sensitivity and specificity (according to some studies, up to 95%) [

11]. Another marker, which is also present in 50-60% of patients with HCC, is des-gamma-carboxy-prothrombin (DGP or PIVKA-II). It is an abnormal (non-modified) prothrombin that is formed due to vitamin K deficiency or impaired metabolism in the liver. In HCC, liver cells lose the ability to carboxylate prothrombin, which leads to an increase in the blood level of its unmodified form [

12]. The examples of AFP-L3 and DGP show that measuring the content of specific proteoforms provides better results [

13]. At the same time, a combination of AFP, DGP and AFP-L3 allows achieving a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of more than 97% [

14].

Therefore, the proteoforms are the promising objects in biomarker studies [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Over the past decades, the use of a combination of two-dimensional electrophoresis (2DE) with panoramic mass spectrometry (integrative top-down proteomics) has become a promising approach to studying proteoforms, which effectively implements the capabilities of these methods [

16,

19,

20,

21]. As a result, for each of the proteins presented in the sample, due to preliminary fractionation, it is possible to obtain information on proteoform patterns in various conditions. Comparative analysis of such patterns in the norm and in HCC allows reducing labor costs for searching for specific proteoforms as potential tumor markers. Therefore, obtaining information on proteoforms and their profiles is especially relevant, given the numerous changes within the human proteome in cancer diseases [

22].

In prior work, we applied the same approach in the model experiment of HCC – comparative analyses of liver and the cell line HepG2 [

23]. The current study expands these findings to clinical samples, revealing critical insights into HCC-specific proteoform signatures.

2. Materials and Methods

Human HepG2 cells were cultured, collected, and extracted in the same way as was described before [

23,

24].

Liver tissue samples from patients with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma were provided by the First Department of Abdominal Surgery and Oncology of the B.V. Petrovsky Russian Scientific Center of Surgery. Two samples were obtained from each patient: tumor tissue and control liver tissue in test tubes containing the RNAlater stabilizing solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Tissue pieces (HCC and non-tumor part of the liver) weighing ~1 g were obtained at the Blokhin Institute (Moscow, Russia). The sample collection protocol was approved by the Institute ethics rules. Protocol No. 01/14/21 of the Meeting of the Medical and Ethical Committee of the B.V. Petrovsky Russian Scientific Center of Surgery. Informed consent was signed by all patients and donors. The samples after surgery were completely immersed in the test tubes with RNAlater solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA), where they soaked for 24 hours at room temperature. Then, the samples were stored in this solution at -80°C.

2.1. Extraction of Proteins

For extraction, the sample was placed in a ceramic mortar with liquid nitrogen. The frozen sample was crushed with a ceramic pestle, and the resulting powder was transferred to 1.5-ml test tubes (Eppendorf, Germany), approximately 200 mg per test tube. To exclude proteolytic and chemical degradation of proteins, further sample preparation was carried out on ice. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with protease inhibitors (500 μl) was added to each tube, pipetted, and then centrifuged (2 min, 5000 g, 4°C). After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed. The procedure was repeated, and the resulting pellet in each tube was dissolved in 600 μl of lysis buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 1% dithiothreitol (DTT), 2% ampholytes, pH 3–10, a mixture of protease inhibitors), processed 6 times with a SONOPULS HD 2070 ultrasonic homogenizer (Bandelin Electronic, Germany) in the following mode: 2 sec pulse / 2 sec pause (6 times), and centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 g, at a temperature of 4°C. The supernatant was collected, divided into 100 μl aliquots, and stored at -80°C. Five pairs of samples (control and tumor) were processed in this manner.

2.2. Filter Aided Sample Preparation (FASP) Method

Panoramic proteomic analysis of the obtained extracts was performed using filter processing and subsequent mass spectrometry (the so-called Filter Aided Sample Preparation (FASP) method) [

25]. Centrifuge concentrators (Microcon YM–30, Merck, USA) were used for this purpose. Extracts containing the required amount of protein (300 μg) were placed in concentrators and sequentially treated with solutions: (a) for the reduction of disulfide bonds (100 mM DTT in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5), then (b) for the alkylation of sulfhydryl groups (50 mM iodoacetamide, 8 M urea, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5), (c) for hydrolysis with trypsin (Trypsin Gold, Promega, USA). Each of the steps was accompanied by preliminary mixing on a Yellowline TTS 2 shaker (IKA, Germany) for 20–30 sec incubation in a Comfort Thermomixer (Eppendorf, USA) and centrifugation at 9800 g for 15 min at 20°C. After each step, the sequentially used solutions were removed by adding 200 μl of washing solution (8 M urea in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5). Reduction was performed by incubation for 1 h at 56°C. Alkylation was performed by incubation for 1 h in the dark at 20°C. Before hydrolysis, the samples were washed twice with 200 μl of buffer solution (50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.5). For hydrolysis, trypsin (Trypsin Gold, Promega, USA) in a buffer solution of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.5 was used. The trypsin concentration required for hydrolysis was taken based on the mass ratio of the total mass of the enzyme / the total mass of the protein - 1/100. Incubation was carried out overnight at 37°C. To stop trypsinolysis, 50 μl of 30% formic acid solution were added to the hydrolysates on the filters. The resulting peptide solution was transferred to clean 250-μl glass inserts (Agilent, USA) and dried in a vacuum concentrator (Concentrator 5301, Eppendorf, Germany) at 45°C. Before MS analysis, the dried peptides were dissolved in 20 μl of a 5% formic acid solution. The final concentration was 1 μg/μl, based on the calculations that the mass of the total protein taken for analysis is equal to the mass of peptides in the sample.

2.3. Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis (2DE)

The procedure of 2DE was performed using an immobilized pH gradient (IPG gel strips 7 cm (pH 3–11) (GE Healthcare, USA)) as described previously [

26,

27]. In short, samples prepared according to

Section 2.1 were mixed with rehydration buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 2% CHAPS, 0.3% DTT, 2% IPG buffer, pH 3–10, 0.001% bromophenol blue) in a final volume of 150 µl. Passive rehydration was performed at 4°C overnight to maximize sample loading into the gel. IEF was performed at 20°C on a Hoefer™ IEF100 instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with the manufacturer’s preset settings for 7-cm strips. IEF was terminated upon reaching 9000 volt-hours. Before separation according to molecular weight, gel strips with pI-separated proteins were incubated 10 min in an equilibration solution: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 6 M urea, 2% SDS, 30% glycerol, and a reducing agent of 1% DTT. Then DTT was replaced with an alkylating agent of 5% iodoacetamide (10 min). The strips were sealed with a hot solution of 0.5% agarose prepared in electrode buffer (25mM Tris, pH 8.3, 200 mM glycine, and 0.1% SDS) on top of the polyacrylamide gel (14%), and run in the second direction [

26,

27]. Gels stained by Coomassie Blue R350 were scanned by ImageScanner III and analyzed using Image Master 2D Platinum 7.0 (GE Healthcare). For the sectional 2DE analysis, this gel was cut into 96 sections with determined coordinates [

28,

29]. Each section (~0.7 cm²) was shredded and treated with trypsin. Tryptic peptides were eluted from the gel by extraction solution (5% (v/v) ACN, 5% (v/v) formic acid) and dried in Speed Vac. For complete reduction, 300 μL of 3 mM DTT and 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate were added to each section and incubated at 50°C for 15 minutes. For alkylation, 20 μl of 100 mM IAM were added, and samples were incubated in the dark at RT for 15 min. The peptides were eluted with 60% ACN and 0.1% TFA and dried in Speed Vac.

2.4. ESI LC-MS/MS Analysis

Tandem mass spectrometry analysis was conducted in duplicate on an Orbitrap Q-Exactive mass spectrometer (“Thermo Scientific,” USA) as it was described previously [

26,

27]. The data were analyzed by SearchGui [

30] using the following parameters: enzyme – trypsin; maximum of missed cleavage sites – 2; fixed modifications – carbaidomethylation of cysteine; variable modifications – oxidation of methionine, phosphorylation of serine, threonine, tryptophan, acetylation of lysine; the precursor mass error – 10 ppm; the product mass error – 0.01 Da. As a protein sequence database, UniProt (October 2014) was used. Only 100% confident results of protein identification were selected. Exponentially modified PAI (emPAI), the exponential form of protein abundance index (PAI) defined as the number of identified peptides divided by the number of theoretically observable tryptic peptides for each protein, was used to estimate protein abundance [

31]. Visualization of the obtained data was performed on the PeptideShaker platform (v.1.16.45). For subsequent analysis, proteins for which at least 2 unique peptide sequences were found were considered identified.

2.5. Analysis and Statistical Processing of Data

In the case of data obtained by FASP method, calculations of the emPAI(%) – emPAI of the particular protein/isoform normalized to the sum of all emPAIs in the sample – were performed in Microsoft Excel 2010 using the following formula:

For the sectional 2DE analysis, calculation of emPAI(%) was performed by normalizing the sum of emPAIs for the proteoforms of the individual protein to the sum of the emPAI values of all identified proteoforms in the sample.

where

p

1 + р

2 + р

3 + p

n is the sum of emPAI values of proteoforms related to a specific isoform of the protein-coding gene (PCG), and

is the sum of emPAI values of all identified proteoforms in the sample. The resulting normalized emPAI value reflects the absolute quantitative content of protein in molar percentage concentration for a specific PCG in the sample.

A statistical assessment of the reliability of the results was performed using the Student’s t-test with a significance level of p<0.05. For further analysis, proteins corresponding to the following criteria were selected in each of the analyzed groups: fold change (FC)≥1.5 and/or presence only in malignant cells. Visualization of statistical data was performed in the Graph Pad Prism program (version 8.0.1) (

https://www.graphpad.com).

Functional annotation of the identified proteins in three categories: biological processes, molecular functions and protein classes, was performed using the PANTHER web resource [

32]. Graphical representation of proteoform patterns was performed in the form of three-dimensional graphs in the Microsoft Excel program.

3. Results

3.1. Proteomic Profiling of Samples from Patients with HCC

3.1.1. Panoramic Proteomic Profiling

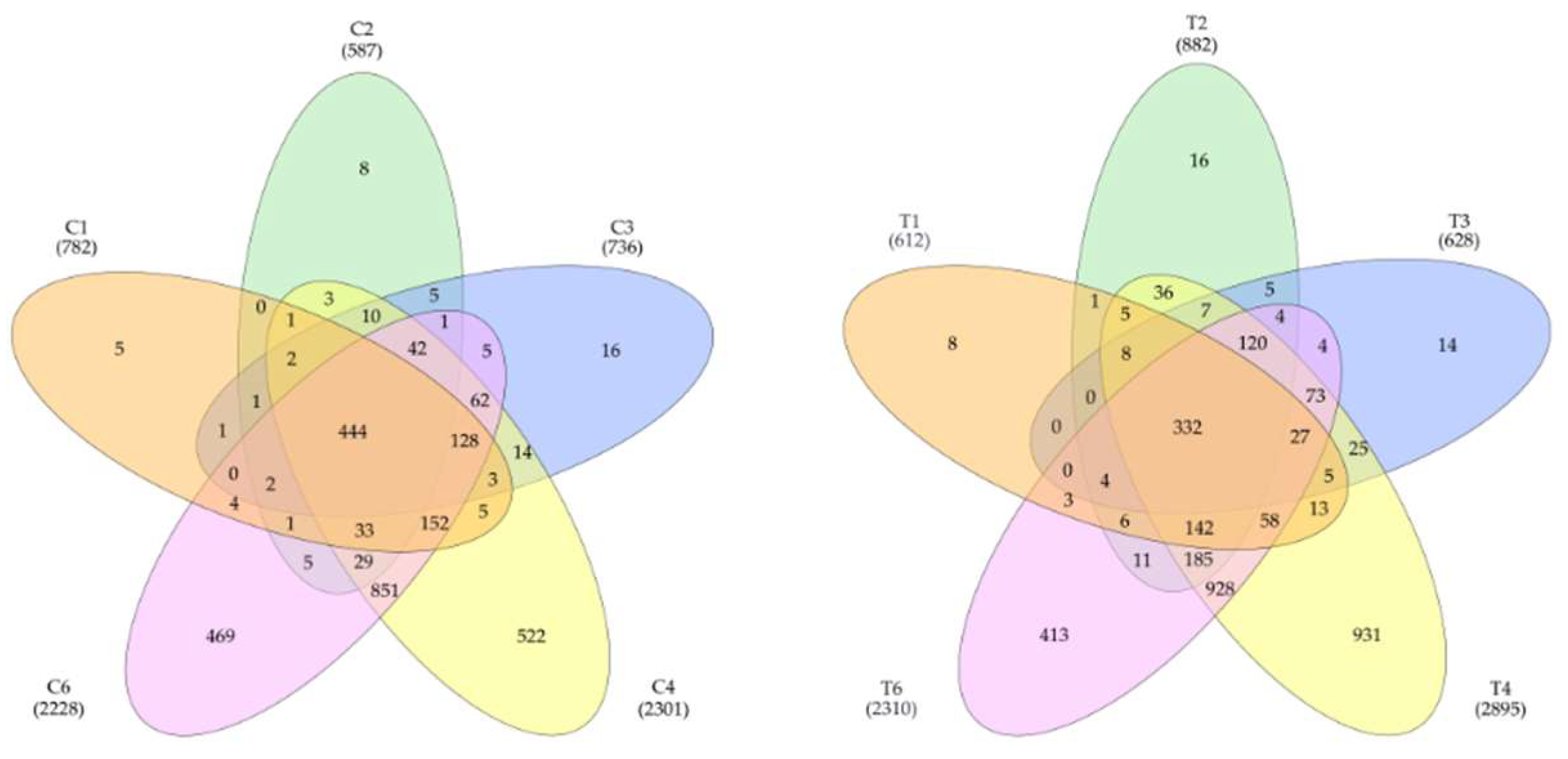

The data on the identified proteins in all 5 samples were processed. In tumors, it was detected 3198 proteins, in the control samples – 2824. Totally, 3677 proteins were detected (

Figure 1). Statistical processing allowed us to identify proteins whose levels significantly differed between the control and the tumor. It turned out that the level of 1627 proteins was higher in the tumor (FC cut off 1.5 times) or they were not detected in the control. In the control, there were 656 such proteins (

Supplementary Table S1).

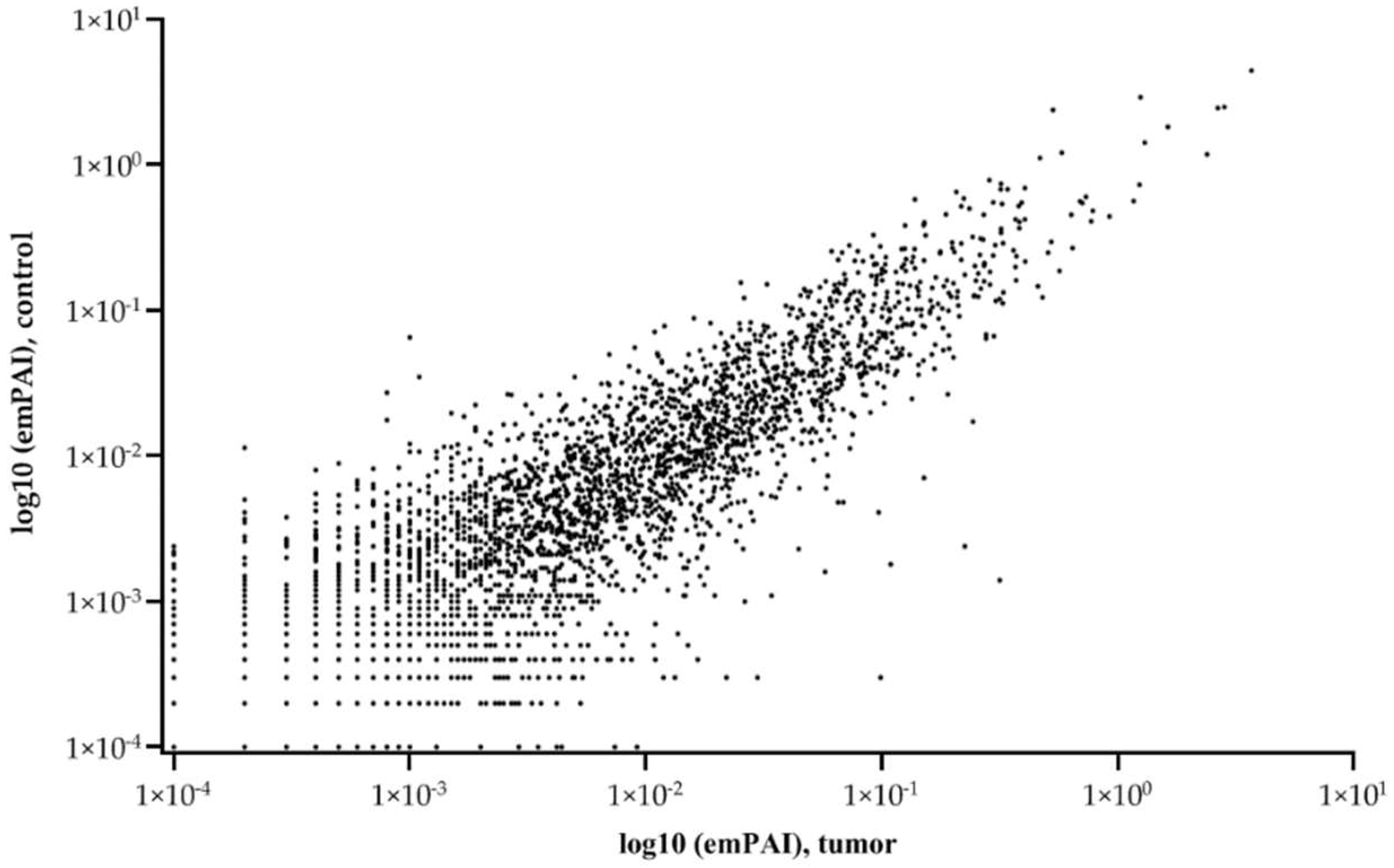

The graph of relationship between tumor and control liver tissue protein abundances (emPAI) shows that the balance of proteins with different copy numbers is maintained under different states (control or tumor) (

Figure 2).

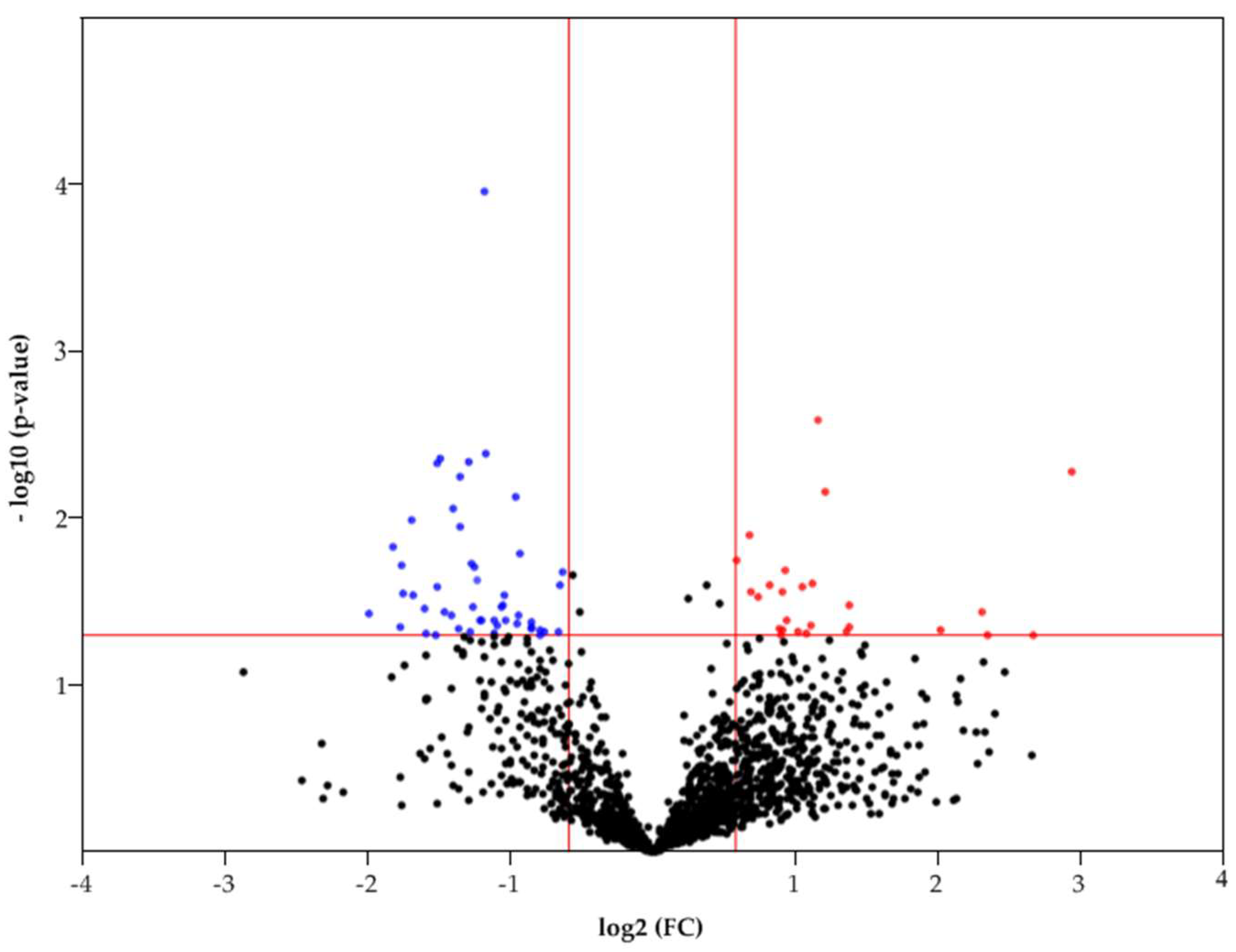

Statistically significant differences in FC (fold change) between samples (T/C) can be observed by constructing a Volcano plot (

Figure 3). Only, 1613 proteins that were detected in both normal and tumor samples were considered in this case. Thus, according to statistical significance (p < 0.05), there are 85 differently expressed proteins (FC 1.5 up/down), of which 28 proteins had an increased abundance and 57 proteins had a decreased abundance in HCC (

Figure 3). The most upregulated proteins (FC>4) are: FBLN3 (EGF-containing fibulin-like extracellular matrix protein 1), G6PD (Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase), BAP31 (B-cell receptor-associated protein 31), ITAM (Integrin alpha-M), HLAC (HLA class I histocompatibility antigen, C alpha chain). The most downregulated proteins (FC>3): DHB8 ((3R)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase), AL8A1 (2-aminomuconic semialdehyde dehydrogenase), TKFC (triokinase/FMN cyclase), MMSA (methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase), PAHX (phytanoyl-CoA dioxygenase, peroxisomal), ACOT2 (acyl-coenzyme A thioesterase 2, mitochondrial), GLYAT (glycine N-acyltransferase), DDAH1 (N(G), N(G)-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 1), F16P2 (Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase isozyme 2).

3.1.2. 2DE Sectional Proteomic Profiling

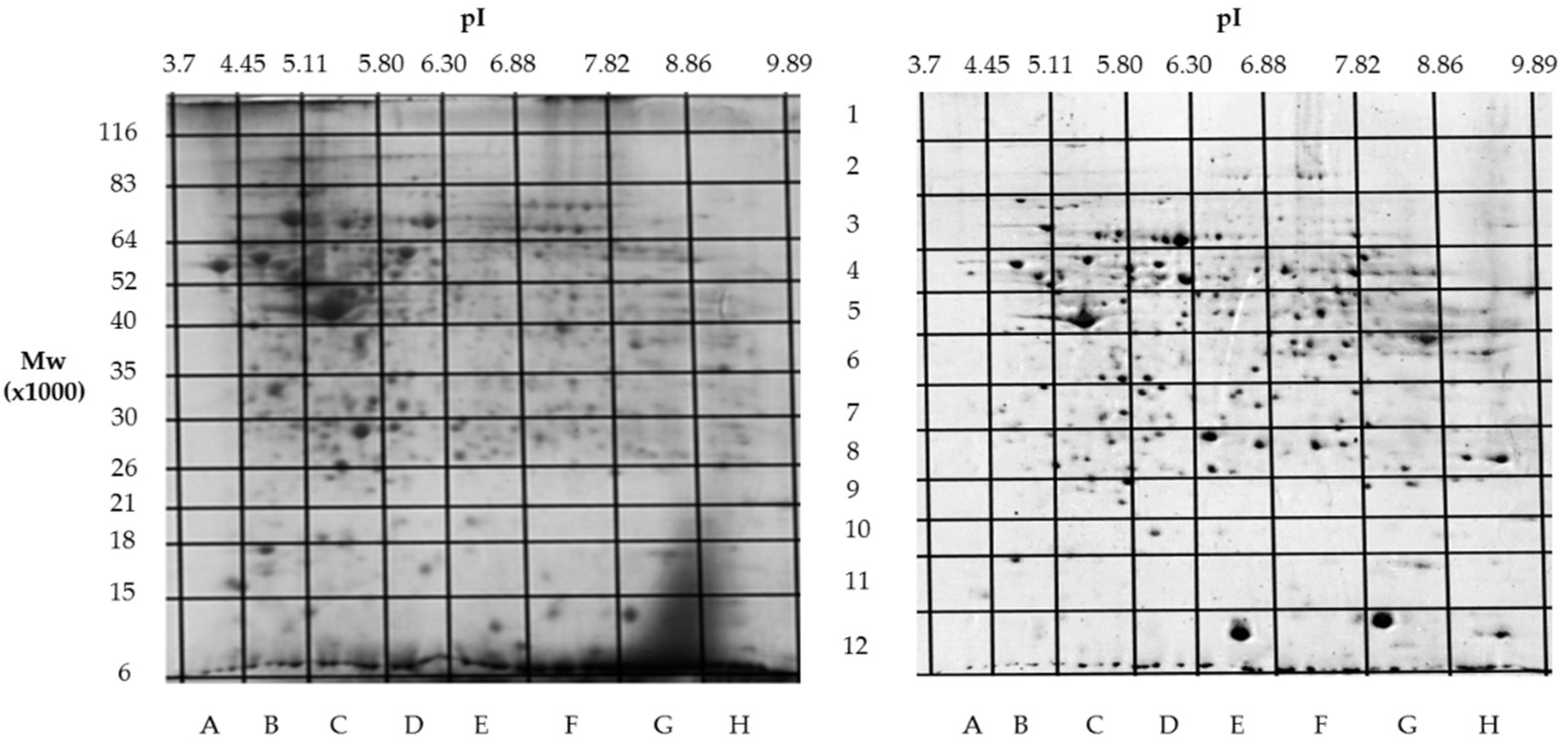

Building on our previous comparative proteomics analysis of normal liver tissue and HepG2 cell lines [

23], we applied a sectional 2DE approach to extend panoramic proteomic profiling to HCC patient-derived tumor and control liver tissues. As an example,

Figure 4 shows 2DE for tumor (T1) and control (C1) liver tissue from patient #1, further analysis of which allowed visualization of proteoform data as three-dimensional plots of proteoform patterns, which reflect the position of proteoforms in the gel and the relative protein content. As a result, a total of 13,000 proteoforms were detected for the T1 sample. Based on these data, three-dimensional graphs for proteoform patterns of each protein (isoform, more precisely) were constructed. Patterns of 2843 isoforms were constructed for the T1 sample, and of 2427 – for the control sample (C1). Altogether, it was constructed 4122 not redundant proteoform patterns for all tumor samples and 3510 – for all control samples.

The data obtained by the 2DE sectional profiling were collected and normalized according to the

Section 2.4. As in the case of proteomic profiling, a summary table was generated containing data on all identified proteins and their normalized emPAI values. Proteins that met the selection criteria (FC≥1.5 or presence only in tumor tissue) were selected. A total of 4,526 non-redundant proteins were identified in all samples of tumor and control liver tissue. Comparing the identified proteins in the tumor and the control liver tissue, 3,106 proteins were found to be common. When comparing proteoform patterns obtained by 2DE sectional proteomic profiling of liver tumor tissue and HepG2 cell line, it turned out that in the overwhelming majority of cases the patterns are very similar, and the dominant peak corresponds to the theoretical parameters of the protein (so it is unmodified) (

Supplementary Table S2). Some examples are presented in

Figure 5. There are also proteins with different patterns that are presented in

Supplementary Table S3.

3.1.3. Combining the Results of Panoramic and 2DE Sectional Proteomic Profiling

Using 2DE sectional proteomic profiling, we were able to identify significantly more proteins than with panoramic profiling in tumor tissue and control liver tissue (

Figure 6).

For further analysis, the results presented as summary tables for panoramic and 2DE sectional profiling were combined into one table (

Supplementary Table S4). The table shows the calculated data on the absolute quantitative protein content in molar percentage concentration for a certain gene in tumor and control liver tissue obtained by two approaches. From the identified proteins, proteins with a cutoff criterion of FC≥1.5 were selected for the more detailed analysis. Having analyzed the obtained data, not only on differently presented proteins, but also on their proteoform patterns, we selected 38 proteins for which the changes in patterns compared to the control were most pronounced (

Table 1,

Figure 7,

Supplementary Table S3).

There are three proteins in this list that are also among statistically significantly up-regulated proteins detected by panoramic profiling (

Supplementary Table S1): EGF-containing fibulin-like extracellular matrix protein 1 (FBLN3), Integrin alpha-M (ITAM), Very-long-chain enoyl-CoA reductase (TECR).

3.2. Functional Annotation of Potential HCC Biomarkers

Gene ontology analysis by Panther GO (

https://www.pantherdb.org/) allowed us to compare proteins prevalent in the tumor or control by function, process, and class (

Figure 8). Among the most characteristic differences, it is necessary to note the activation of immune processes (immune system process (GO:0002376)) and the process of interspecies interaction (biological process involved in interspecies interaction between organisms (GO:0044419)) in tumors. As for molecular functions, translation regulator activity (GO:0045182) and translational proteins (PC00263) prevail in HCC. The molecular function regulator activity (GO:0098772) is also more diverse in tumors. More proteins of the extracellular matrix (PC00102), DNA metabolism (PC00009), and cytoskeleton (PC00085) were detected as well. However, small molecule metabolism enzymes (metabolite interconversion enzymes, PC00262) are better represented in the control. But it is interesting that among 38 selected proteins (

Table 1), this class of enzymes is most prominent (7 gene entries – ACLY, PKM, AKR1B15, ACSL4, TECR, GALNT2, ALPL).

In addition, we compared our data with the information from the Human Protein Atlas database (

https://www.proteinatlas.org/, accessed on 22 March 2025) on prognostic markers of HCC, which in this database are mainly represented by transcription data. It turned out that 500 upregulated in HCC proteins appear as prognostic unfavorable markers in the Human Protein Atlas database. Interestingly, 70 proteins are classified as prognostic favorable markers.

Table 2 shows some of these proteins. A slightly different picture is observed for proteins whose level prevails in the control (193 proteins). Here, there are approximately the same number of both favorable and unfavorable tumor markers. This indicates some ambiguity in determining the favorability of a protein based on determining the level of its RNA expression.

4. Discussion

Previously, we have published the paper where the search of HCC biomarkers was based on comparative proteomics analysis of HepG2 cells and liver tissue [

14]. Obviously, it was interesting to compare all available data (HepG2 cells, tumor tissue, and liver tissue). If we consider only the proteins for which an increase in their abundance (FC≥1.5) in tumors and in HepG2 cells was detected, it was 747 common proteins from 2094 (

Supplementary Table S5). This information itself points out that HepG2 cells can be used for searching for HCC biomarkers. Also, 10 proteins from

Table 1 (ACLY, ACSL4, ANXA2, ANXA3, COPD, EPIPL, TRFL, P3H1, KPYM, SRSF5) were detected previously in the HepG2 cell line as having similar to HCC proteoform patterns (

http://2de-pattern.pnpi.nrcki.ru/index.html) [

23]. It means that despite the considerable difference in growing conditions between HCC tissue and HepG2 cells that affect the cellular metabolism [

33,

34], still some proteomics peculiarities remain the same in both types of cells [

35]. However, it is clear that the proteome of HepG2 cells in many aspects is different from the proteomes of the primary normal and tumor cells [

36,

37,

38].

It should be mentioned that based on just their elevated abundance in HCC, there are many candidates for HCC biomarkers. The evident changes in proteoform patterns are quite rare cases, and the difference between the analyzed objects is mainly associated with changes in protein abundances. As the better (so-called ideal) HCC biomarkers are the main aim of our study, they should be searched inside these altered patterns. An “ideal biomarker” should also have a high potential for secretion into the blood to be detected and quantified by non-invasive methods. According to UniProt, eleven proteins from

Table 1 (ANXA1, ANXA2, FBLN3, FCN1, GALT2, TRFL, P3H1, PIGR, PROS, TSP1, VWA1) are secreted and can be considered as better biomarker candidates for HCC. From this point of view, the proteins ANXA2, TRFL, P3H1 look most interesting as their proteoform patterns are changed in HCC and HepG2 cells. The next step is to decipher the peaks (proteoforms) that are present in the tumor cells, not in the normal liver. This is the task for top-down mass spectrometry.

It should also be mentioned that there is a resolution challenge in our experiments. A single PTM, like acetylation or phosphorylation, can produce a shift of pI ~ 0.05 [

39,

40]. However, in our sectional 2DE analysis, the pI range of the sections is much bigger (0.7–0.8). It means that we are missing a separation of many proteoforms as they can be located in the same sections. Accordingly, at higher resolution, more proteoforms and proteoform pattern differences between HCC and control should be revealed. Actually, the resolution can be improved by running bigger gels and analyzing smaller gel sections, but it will dramatically increase the time and expenses of the experiment.

5. Conclusions

A combination of panoramic proteomic profiling with 2DE sectional proteomic profiling (integrative top-down proteomics) allows more reliable and convenient representations of information including diverse proteoforms coded by the same genes (proteoform patterns). These patterns for majority of proteins are very similar in all types of the analyzed samples (HepG2, human liver, HCC tissue, HCC control tissue), where dominant peak corresponds to the theoretical parameters of the protein (so it is unmodified). But for some proteins there are differences that could be used for generation of specific HCC biomarkers.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: All proteins detected in HCC and control samples by panoramic profiling (FASP); Table S2: The similar proteoform patterns obtained for all types of the analyzed samples (liver, HepG2, HCC, non-tumor control); Table S3: The proteins with different proteoform patterns in HCC and control; Table S4: A complete list of proteins identified by two methods – 2DE sectional and panoramic proteomic profiling (FASP); Table S5: The fold-change of the protein abundance in the pairs HepG2/liver and HCC/control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N; validation, N.R., E.Z., N.K., V.Z.; formal Analysis, N.R., E.Z., N.K., F.K., O.L., V.Z; investigation, N.R., E.Z., N.K., V.Z.; data curation, N.R., E.Z., N.K., O.L., V.Z.; methodology, S.N., E.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.N; writing—review and editing, S.N.; visualization, N.R., E.Z.; supervision, S.N.; project administration, S.N.; funding acquisition, S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (RSF) grant No. 24-24-00432.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Russian Scientific Center of Surgery named after B.V. Petrovsky (protocol № 14 from 16.12.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Mass-spectrometry measurements were performed using the equipment of “Human Proteome” Core Facilities of the Institute of Biomedical Chemistry (Moscow, Russia).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

ACN

DTT

FC

GO

HCC

IAM |

acetonitrile

dithiothreitol

fold change

gene ontology

hepatocellular carcinoma

iodoacetamide |

| 2DE |

two-dimensional electrophoresis |

| ESI LC-MS/MS |

liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry |

PTM

emPAI

PCG

TFA |

post-translation modification

exponentially modified form of protein abundance index

protein-coding gene

trifluoroacetic acid |

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R. L.; Torre, L. A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarao, K.; Nozaki, A.; Ikeda, T.; Sato, A.; Komatsu, H.; Komatsu, T.; Taguri, M.; Tanaka, K. Real impact of liver cirrhosis on the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in various liver diseases-meta-analytic assessment. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 1054–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, M. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, risk factors, and screening. Semin. Liver Dis. 2005, 25, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Cuevas, J.; Lucano-Landeros, S.; López-Cifuentes, D.; Santos, A.; Armendariz-Borunda, J. Epidemiologic, Genetic, Pathogenic, Metabolic, Epigenetic Aspects Involved in NASH-HCC: Current Therapeutic Strategies. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganne-Carrié, N.; Nahon, P. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the setting of alcohol-related liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daher Darine Dahan Karim Seif El, S. A. G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma. JLC 2023, 23, 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Forner, A.; Reig, M.; Bruix, J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet (London, England) 2018, 391, 1301–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TATARINOV, I. S. [DETECTION OF EMBRYO-SPECIFIC ALPHA-GLOBULIN IN THE BLOOD SERUM OF A PATIENT WITH PRIMARY LIVER CANCER]. Vopr. Med. Khim. 1964, 10, 90–91. [Google Scholar]

- Terentiev, A. A.; Moldogazieva, N. T. Alpha-fetoprotein: a renaissance. Tumour Biol. J. Int. Soc. Oncodevelopmental Biol. Med. 2013, 34, 2075–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABELEV, G. I.; PEROVA, S. D.; KHRAMKOVA, N. I.; POSTNIKOVA, Z. A.; IRLIN, I. S. Production of embryonal alpha-globulin by transplantable mouse hepatomas. Transplantation 1963, 1, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, C.; Kushnir, M. M.; Yang, Y. K. Glycosylation Profiling of the Neoplastic Biomarker Alpha Fetoprotein through Intact Mass Protein Analysis. J. Proteome Res. 2023, 22, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebman, H. A.; Furie, B. C.; Tong, M. J.; Blanchard, R. A.; Lo, K. J.; Lee, S. D.; Coleman, M. S.; Furie, B. Des-gamma-carboxy (abnormal) prothrombin as a serum marker of primary hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984, 310, 1427–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N. P.; Chen, L.; Lin, M. C.; Tsang, F. H.; Yeung, C.; Poon, R. T.; Peng, J.; Leng, X.; Beretta, L.; Sun, S.; Day, P. J.; Luk, J. M. Proteomic expression signature distinguishes cancerous and nonmalignant tissues in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Proteome Res. 2009, 8, 1293–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, L. R. Biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Adv. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 14, 223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Lisitsa, A.; Moshkovskii, S.; Chernobrovkin, A.; Ponomarenko, E.; Archakov, A. Profiling proteoforms: promising follow-up of proteomics for biomarker discovery. Expert Rev. Proteomics 2014, 11, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonara, K.; Andonovski, M.; Coorssen, J. R. Proteomes Are of Proteoforms: Embracing the Complexity. Proteomes 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgrave, L. M.; Wang, M.; Yang, D.; DeMarco, M. L. Proteoforms and their expanding role in laboratory medicine. Pract. Lab. Med. 2022, 28, e00260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, J.; Gevaert, K. Mass spectrometry-based clinical proteomics – a revival. Expert Rev. Proteomics 2021, 18, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naryzhny, S. Inventory of proteoforms as a current challenge of proteomics: Some technical aspects. J. Proteomics 2019, 191, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungblut, P. R. Back to the future-The value of single protein species investigations. Proteomics 2013, 13, 3103–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, K.; Lelong, C.; Rabilloud, T. What room for two-dimensional gel-based proteomics in a shotgun proteomics world? Proteomes 2020, 8, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, M.; Zheng, X. Application of the Human Proteome in Disease, Diagnosis, and Translation into Precision Medicine: Current Status and Future Prospects. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naryzhny, S.; Zgoda, V.; Kopylov, A.; Petrenko, E.; Kleist, O.; Archakov, А. Variety and Dynamics of Proteoforms in the Human Proteome: Aspects of Markers for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Proteomes 2017, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naryzhny, S. N.; Lisitsa, A. V.; Zgoda, V. G.; Ponomarenko, E. A.; Archakov, A. I. 2DE-based approach for estimation of number of protein species in a cell. Electrophoresis 2014, 35, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski J., R.; Zougman, A. . N. N. & M. M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat. Methods 2009, 6, 359–362. [Google Scholar]

- Naryzhny, S.; Ronzhina, N.; Zorina, E.; Kabachenko, F.; Klopov, N.; Zgoda, V. Construction of 2DE Patterns of Plasma Proteins: Aspect of Potential Tumor Markers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naryzhny, S. N.; Zgoda, V. G.; Maynskova, M. A.; Novikova, S. E.; Ronzhina, N. L.; Vakhrushev, I. V.; Khryapova, E. V.; Lisitsa, A. V.; Tikhonova, O. V.; Ponomarenko, E. A.; Archakov, A. I. Combination of virtual and experimental 2DE together with ESI LC-MS/MS gives a clearer view about proteomes of human cells and plasma. Electrophoresis 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naryzhny, S. Towards the full realization of 2DE power. Proteomes 2016, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naryzhny SN, Maynskova MA, Zgoda VG, Ronzhina NL, Novikova SE, Belyakova NV, Kleyst OA,. Legina OK, Pantina RA, F. M. Proteomic profiling of high-grade glioblastoma using virtual-experimental 2DE. J Proteomics Bioinform 2016, 9, 158–165.

- Vaudel, M.; Barsnes, H.; Berven, F. S.; Sickmann, A.; Martens, L. SearchGUI: An open-source graphical user interface for simultaneous OMSSA and X!Tandem searches. Proteomics 2011, 11, 996–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihama, Y.; Oda, Y.; Tabata, T.; Sato, T.; Nagasu, T.; Rappsilber, J.; Mann, M. Exponentially Modified Protein Abundance Index (emPAI) for Estimation of Absolute Protein Amount in Proteomics by the Number of Sequenced Peptides per Protein. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2005, 4, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P. D.; Ebert, D.; Muruganujan, A.; Mushayahama, T.; Albou, L.-P.; Mi, H. PANTHER: Making genome-scale phylogenetics accessible to all. Protein Sci. 2022, 31, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liguori, M. J.; Blomme, E. A. G.; Waring, J. F. Trovafloxacin-induced gene expression changes in liver-derived in vitro systems: comparison of primary human hepatocytes to HepG2 cells. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schicht, G.; Seidemann, L.; Haensel, R.; Seehofer, D.; Damm, G. Critical Investigation of the Usability of Hepatoma Cell Lines HepG2 and Huh7 as Models for the Metabolic Representation of Resectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slany, A.; Haudek, V. J.; Zwickl, H.; Gundacker, N. C.; Grusch, M.; Weiss, T. S.; Seir, K.; Rodgarkia-Dara, C.; Hellerbrand, C.; Gerner, C. Cell characterization by proteome profiling applied to primary hepatocytes and hepatocyte cell lines Hep-G2 and Hep-3B. J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiśniewski, J. R.; Vildhede, A.; Norén, A.; Artursson, P. In-depth quantitative analysis and comparison of the human hepatocyte and hepatoma cell line HepG2 proteomes. J. Proteomics 2016, 136, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Geyer, P. E.; Gupta, R.; Santos, A.; Meier, F.; Doll, S.; Wewer Albrechtsen, N. J.; Klein, S.; Ortiz, C.; Uschner, F. E.; Schierwagen, R.; Trebicka, J.; Mann, M. Dynamic human liver proteome atlas reveals functional insights into disease pathways. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2022, 18, e10947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sison-Young, R. L. C.; Mitsa, D.; Jenkins, R. E.; Mottram, D.; Alexandre, E.; Richert, L.; Aerts, H.; Weaver, R. J.; Jones, R. P.; Johann, E.; Hewitt, P. G.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Goldring, C. E. P.; Kitteringham, N. R.; Park, B. K. Comparative Proteomic Characterization of 4 Human Liver-Derived Single Cell Culture Models Reveals Significant Variation in the Capacity for Drug Disposition, Bioactivation, and Detoxication. Toxicol. Sci. 2015, 147, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halligan, B. D.; Ruotti, V.; Jin, W.; Laffoon, S.; Twigger, S. N.; Dratz, E. A. ProMoST (Protein Modification Screening Tool): A web-based tool for mapping protein modifications on two-dimensional gels. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naryzhny, S.; Zgoda, V.; Kopylov, A.; Petrenko, E.; Archakov, А. A semi-virtual two dimensional gel electrophoresis: IF–ESI LC-MS/MS. MethodsX 2017, 4, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).