1. Introduction

Audio or automatic speech recognition (ASR) has been highly integrated into modern personal electronics. In particular, due to the rise of digital assistants, ASR has been hailed as the future of human-computer interfaces. However, these exciting advancements and aspirations have not been fully realized due to several key inherent limitations of ASR. Modern ASR models achieve near-human accuracy in quiet environments or synthetic clean speech, but their word-error rates (WER) often grow by an order of magnitude—routinely from < 5% to 25–60% — when evaluated in realistic noisy environments such as public places, moving vehicles, busy office environments [

1,

2,

3]. Audio-visual speech recognition (AVSR) greatly improves recognition accuracy in noisy conditions by leveraging visual information [

4,

5,

6], much like humans rely on visual cues when background noise masks the acoustic signal [

7]. These AVSR approaches effectively mitigate the impact of noise, often reducing the WER to below 10% [

4,

5,

8], with further potential for improvement toward matching the performance achieved with clean audio.

Despite substantial improvements in noisy conditions, AVSR is rarely integrated into personal electronic devices, likely due to the practical challenges posed by camera placement and head positioning requirements [

9,

10]. This challenge is mitigated in head-worn devices, such as earbuds and mixed reality (MR) headsets, due to the presence of fixed sensors [

11,

12,

13]. The deployment of AVSR in head-worn devices to enhance speech recognition performance represents a promising new application that, to our knowledge, has not yet been implemented in any commercially available device.

Studies have found that the largest inhibitors to individual adoption of ASR-enabled digital assistants are privacy concerns regarding audio data use and fears of private conversations being overheard [

14,

15,

16,

17]. The issue of being overheard is a common complaint of ASR not just for privacy’s sake but also for disrupting nearby individuals [

16,

17]. Cowan et al. found that "social embarrassment" is one of the primary reasons individuals avoid digital assistant [

16]. Visual speech recognition (VSR) or lip reading eliminates the need for vocalization by relying entirely on visual cues, offering the potential to significantly reduce concerns related to privacy and social embarrassment associated with current speech recognition technologies.

Despite its potential to address speech recognition challenges, VSR remains significantly less accurate than ASR and AVSR, exhibiting word error rates that are often orders of magnitude higher compared to ASR and AVSR. Differentiating speech based solely on lip movements is challenging as multiple phonemes can map to the same viseme, resulting in visually indistinguishable patterns. Additionally, due to the widespread adoption of ASR, ASR datasets are significantly more common than those for AVSR and VSR, resulting in limited availability of high-quality training data for AVSR and VSR methods.

Given the substantial potential to advance the adoption of speech recognition and digital assistant systems, this work primarily focuses on improving VSR accuracy and robustness. Additionally, our methods enhance noise robustness for both AVSR and ASR tasks, further demonstrating the broad applicability and value of our methods.

Our contributions are as follows:

1) We present a new supervised speech recognition framework for training across audio speech recognition (ASR), visual speech recognition (VSR), and audio-visual speech recognition (AVSR) tasks simultaneously, achieving a remarkable VSR result of 21.0% WER on the LRS3 dataset among models trained on under 3,000 hours of data.

2) We introduce a multi-task hybrid Connectionist Temporal Classification (CTC)/Attention loss that enables direct multi-task training across ASR, VSR, and AVSR tasks. This loss significantly enhances VSR performance while mitigating the high computational demands of multi-task self-supervised learning, demonstrating a

computational efficiency improvement compared to self-supervised multi-task approaches [

18].

3) We demonstrate that supervised multi-task speech recognition models exhibit strong generalization, achieving an impressive 44.7% WER on the WildVSR dataset [

19] among models trained on under 3,000 hours of data and by being less reliant on external language models.

4) We demonstrate that our multi-task training approach significantly reduces the reliance on external language models, a critical advancement for enabling faster and more efficient real-time VSR.

5) We show that our supervised multi-task framework improves the ASR and AVSR tasks when it comes to performance in noisy environments, achieving relative improvement of 16.8% and 30.8%, respectively, compared to the state-of-the-art single-task approaches that are trained on

more data [

4].

2. Related Work

2.1. Self-Supervised Methods

To overcome data scarcity, researchers increasingly adopt self-supervised methods allows for the use of large amounts of unlabeled corpora. In VSR, this capability enables the use of the audio modality of existing corpora [

6,

18,

20,

21,

22,

23] as well as large unlabeled audio-visual corpora [

24,

25].

Ma et al. proposed LiRA, one of the first self-supervised VSR method for sentences. The model is initially trained to predict auditory features with visual features as input [

23]. This model is then fine-tuned in a supervised manner to predict text. They found this self-supervision to improve WER by 1.7% on the LRS2 dataset [

26] compared to a fully supervised baseline.

Building off of masked language model training such as BERT [

27], Shi et al. proposed an audio-visual hidden unit BERT (AV-HuBERT) network that learns to predict audio, audio-visual and visual features that are masked out of the input sequence. This network is then fine-tuned for the ASR and VSR tasks separately. AV-HuBERT improved VSR WER performance by 6.7% compared to a supervised model that was trained on thousands times more data [

28].

While these and other self-supervised methods bolster strong VSR performance by taking advantage of audio and unlabeled data there are some downsides. Djilali et al. found that self-supervised methods required

times more training compute (exaFLOPS) than supervised methods [

19]. While self-supervised methods have proven effective in addressing data scarcity by leveraging audio data to enhance VSR performance, their reliance on complex pretraining and fine-tuning pipelines often results in significant computational overhead, highlighting the need for our efficient multi-task supervised multi-task approach. They additionally highlighted that self-supervised struggle to generalize to the WildVSR dataset compared to fully supervised methods.

2.2. Supervised Methods

Serduyk et al.[

29] and Makino et al.[

28] perform supervised learning to get impressive results thanks to over 90 thousand hours of proprietary VSR data. Without these large proprietary datasets, recent works have used synthetic data generation [

30], architectural improvements [

31], and pseudo-labeling of publicly available data [

4] to improve performance.

To combat scarce public data availability, Ma et al. used a pretrained ASR model [

32] to pre-label audio-visual datasets that were previously only usable by self-supervised methods [

4], VoxCeleb2 [

24] and AVSpeech [

25]. This automatically labeled data increased the training dataset size by four times to 3.4 thousand hours and resulting in a 13.9% reduction in WER and largely outperforming self-supervised methods. Concurrent to this work, Ahn et al. added an audio reconstruction loss with the traditional CTC loss and attention loss [

31]. This comparatively reduced the WER by 2%.

These methods show that VSR performance can be improved using audio data in a supervised approach without requiring compute-expensive self-supervised training. Our method similarly takes advantage of audio data but in a multi-task framework enabling a single model to do all three SR tasks and yielding superior VSR accuracy and greater robustness across all three tasks in real-world scenarios.

2.3. Multi-task Methods

Hsu et al. proposed the first self-supervised multi-task model [

22]. They pretrained a single model on AVSR, ASR, and VSR data pseudo labeled produced by the ASR data. After fine-tuning solely on the ASR task, the model nevertheless achieves impressive zero-shot AVSR and VSR performance, even though no labeled visual data was provided during training.

Concurrent to our work, Haliassos et al. proposed a single model to perform audio, visual and audio-visual speech recognition in a semi-supervised manner [

18]. This multi-task framework uses unsupervised pretraining and fine-tune with semi-supervised learning. Adding to the complexity, in both pretraining and fine-tuning, a student-teacher model is used that increases computation cost greatly. This complex training achieves an impressive WER of 21.6% on the LRS3-TED dataset [

33] but requires

more training compute compared to our supervised multi-task method.

Although multi-task training itself is not new, we introduce the first supervised multi-task framework that surpasses all prior approaches on VSR while demanding substantially less computational budget. Furthermore, our method generalizes substantially better on the WildVSR benchmark [

19], a domain where supervised models typically excel.

3. Methods

To take advantage of feature-rich audio data, we propose a supervised multi-task framework. This framework adapts the state-of-the-art Auto-AVSR [

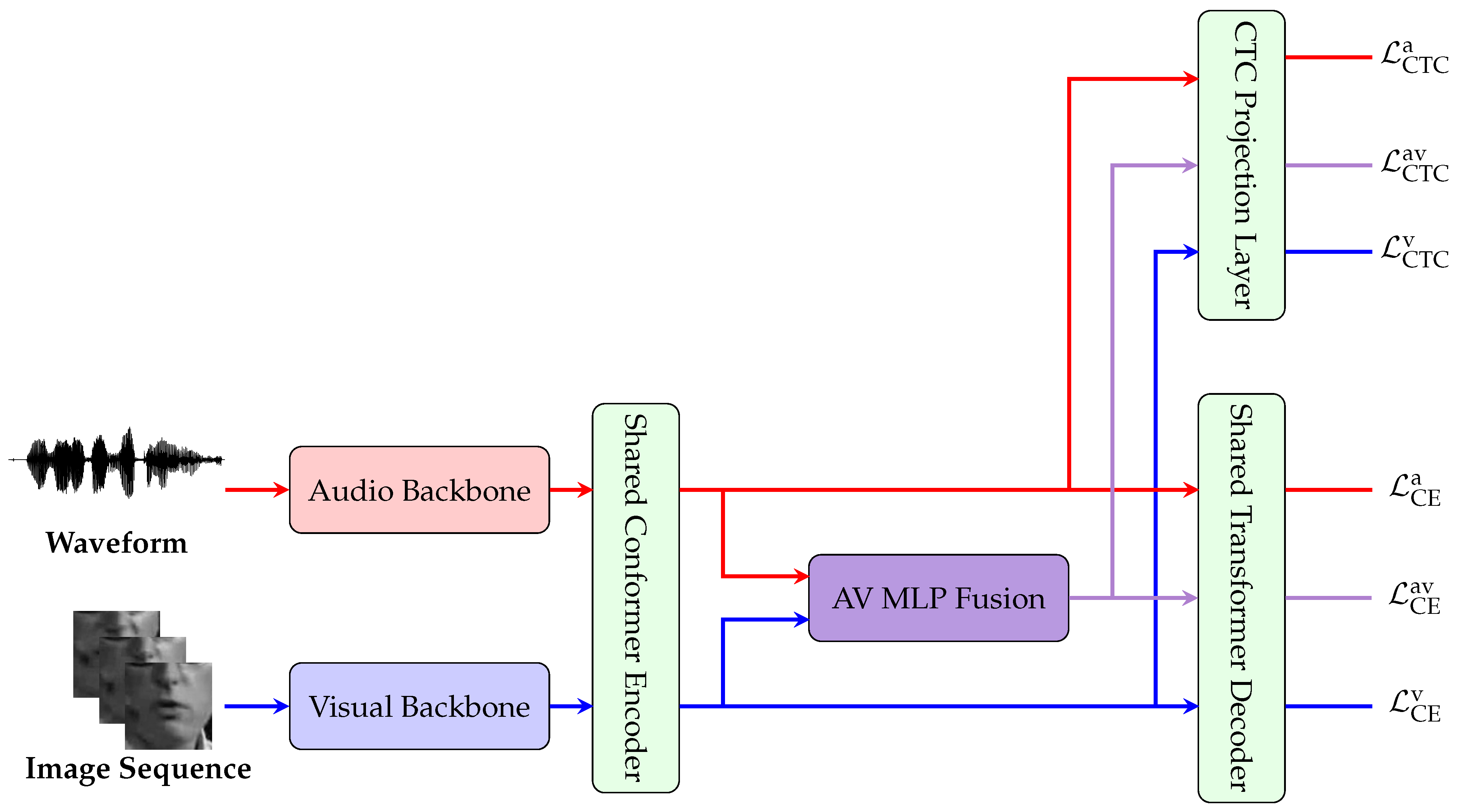

4] method to simultaneously support VSR, AVSR and ASR. As depicted in

Figure 1, our approach introduces shared multi-task conformer encoder, transformer decoder, and CTC projection layer. These shared components enable knowledge transfer from the audio and audiovisual tasks to the more challenging VSR task, while conversely allowing the VSR task to strengthen AVSR and ASR models by encouraging more robust use of audio features. This cross-modal transfer ultimately improves performance under noisy conditions. This unified framework not only streamlines the training process compared to self-supervised multi-task training [

18,

22] but also taps into the data-rich audio signals available, ultimately driving more robust and accurate VSR predictions without introducing unnecessary complexity.

3.1. Architecture

Many recent state-of-the-art AVSR supervised methods [

4,

30,

31] have adopted the off the shelf conformer sequence-to-sequence (CM-seq2seq) architecture [

34]. Due the success of this architecture and it’s subsequent adaptation, we adopt this basic structure. See

Figure 1 for an overview of our architecture. More concretely, the audio backbone consists of a 1D ResNet18, the visual backbone consists of a 3D CNN followed by a 2D Resnet18 model. The typical AVSR CM-seq2seq architecture employs two separate Conformer encoders [

35] to process visual and audio features independently. In contrast, our multi-task framework utilizes a shared Conformer encoder for both modalities, which substantially improves VSR performance while causing only minor reductions in ASR and AVSR performance (see

Table 1). For the decoding strategy, we adopt the transformer decoder and CTC projection layer used to perform the hybrid CTC/Attention loss. For all multi-task trainings, the encoder, decoder and CTC layers are shared across all SR tasks.

3.2. Multi-Task Training

Our multi-task framework enables the simultaneous training of ASR, VSR, and AVSR, enhancing robustness across all three tasks. While multi-task speech recognition has been explored previously [

18,

22], our framework introduces a novel, simpler, and more computationally efficient approach that achieves superior VSR performance. These improvements are achieved by shared parameters with the ASR and AVSR tasks. Given that the primary objective is to enhance VSR performance, we investigate which combinations of training modalities yield the largest VSR improvement.

Table 1 shows that adding both the ASR and AVSR tasks to the training tasks leads to the largest improvement with a drop in WER from 42.0% to 31.1% . While this multi-task training improves VSR performance due to knowledge transfer, it slightly reduces ASR and AVSR performance. This trade-off is acceptable, as ASR and AVSR are inherently easier tasks with high baseline accuracy, and our multi-task framework ultimately improves their robustness to noise, as discussed in

Section 5.4.

3.3. Loss

The final component of the model architecture is the multi-task hybrid CTC/Attention loss. Instead of using a complex loss function to learn from audio data [

18,

20,

21,

22,

31,

36], we propose a simple and effective approach. We simply aggregate the commonly employed hybrid CTC/Attention loss [

34] across all tasks to incorporate multiple tasks in the same training.

Let

with length

T represents the input sequence, output from the shared Conformer encoder, for task

, representing VSR, ASR and AVSR respectively. The target sequence

is shared across all tasks, representing the ground-truth transcription of length

L. For each task, we define the probabilities used in the CTC and Cross-Entropy Attention (CE) losses as follows. The CTC loss

is computed based on the probability:

where

is the probability of the target label at time

t given the input sequence

. The CE loss

utilizes the probability:

where

represents all previous tokens before position

l. We compute the total CTC and CE losses by summing over all tasks:

Our final loss function is a weighted combination of these total losses:

where

is a hyperparameter that balances the contributions of the CTC and CE losses which is set to 0.1 for all experiments.

This adjustment to the hybrid CTC/Attention loss [

34] facilitates multi-task learning in a straightforward and effective manner, significantly improving VSR results. Preliminary experiments prove that our simpler multi-task hybrid CTC/Attention loss function obtains better VSR performance than more complex loss functions similar to those proposed in prior work [

18,

31,

36].

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Datasets

For training MultiAVSR we use the LRS3-TED [

33], LRS2 [

26] and VoxCeleb2 [

24] datasets. LRS3-TED was extracted from TED talks and contains 408, 30 and 0.9 hours of lip reading data in the pre-training, training-validation and test sets respectively. LRS2 is a AVSR dataset consisting of 223 hours from BBC television broadcast data. VoxCeleb2 is a dataset commonly used for audio speaker recognition. It thus does not contain ground true transcripts. To obtain transcripts for the VoxCeleb2 dataset, we follow the Auto-AVSR method [

4] using the large-v3 Whisper model [

32] for language detection and audio transcription yielding 1,307 hours of AVSR data. We conduct three experimental trainings, firstly, with only the LRS3-TED pretraining and training-validation sets (438 hours), secondly with LRS3-TED + LRS2 (661 hours) and finally LRS3-TED + LRS2 + VoxCeleb2 (1,968 hours). We conduct evaluation experiments on the test set of the LRS3-TED dataset [

33] and the newly released WildVSR dataset [

19]. The WildVSR test set is used to evaluate whether VSR networks generalize beyond the LRS3-TED test set. It contains 4.8 hour of individuals speaking in YouTube videos.

4.2. Pre-Processing and Augmentation

For data pre-processing and augmentation, we follow the methods of Ma et al. [

4]. For visual data, the face is localized using RetinaFace [

37] and cropped to the lower portion of the face with the lips in the center at a resolution of 96x96, the image is then grayscaled (see

Figure 1 for example images). During training the images are augmented with randomly cropping to a 88x88 section and adaptive time masking. During inference the images are cropped to the 88x88 center pixels. For auditory data, the raw waveform is used without pre-processing. During training adaptive time masking is applied and babble noise from the NOISEX dataset [

38] is added at one of the following SNR levels [-5 dB, 0 dB, 10 dB, 15 dB, 20 dB,

∞ dB].

4.3. Implementation Details

We generally use the same model setup as Auto-AVSR [

4]. Our 1D Resnet18 audio backbone, 3D CNN + 2D Resnet18 visual backbone, audio-visual fusion MLP, shared conformer encoder, shared transformer decoder, and shared CTC projection layer have 4M, 11M, 19M, 170M, 64M and 4M parameters respectively, summing to a total of 274M. The conformer encoder and transformer decoder have 12 and 6 layers, respectively, with 768 input dimensions, 3,072 feed-forward dimensions and 12 attention heads.

Typically, VSR networks have a pretraining phase where the model is trained on shorter video clips to prepare the model for longer more difficult sequences. This process is called curriculum learning and is widely used by VSR and AVSR methods [

4,

26,

34,

36,

39]. As such, we pre-train all our models with a learning rate of

on samples less than 4 seconds long in the LRS3-TED dataset [

33] for 75 epochs on 8 A100 GPUs. Following the curriculum learning, we fine-tune all models on full length videos in the given datasets for 75 epochs on 8 A100 GPUs with a learning rate of

. All trainings use the AdamW optimizer with a cosine learning rate schedule with a warm-up of 5 epochs.

4.4. Language Model

Many VSR methods employ a transformer-based language model (LM) trained on large corpora of text to improve outputs at evaluation time [

4,

18,

30,

31,

36]. For LM experiments, we use the pre-trained transformer based LM from [

36], consisting of 54 million parameters trained on 166 million characters of text. The weight of the language model is included in the prediction scoring as follows:

Where

is the predicted output tokens,

is the CTC weight which is set to the same value as during training (0.1) and

is the relative weight of the language model.

is set to 0.2 for our LM experiments.

5. Results

5.1. Comparison to the Latest Methods

Our VSR results compared to the latest methods on the LRS3 and WildVSR test sets are presented in

Table 2. When comparing the LRS3-TED results, MultiAVSR outperforms all other methods with less than 3,000 hours of training data on LRS3 with a WER of 21.0%, improving upon the concurrent work SyncVSR [

31] and USR [

18] which both achieve 21.5%. Using Auto-AVSR as the principal baseline, our model lowers the WER by 2.4 percentage points [

4]. In the 438 and 661 hour tests, MultiAVSR outperforms all other methods by a larger margin as can be seen in

Table 2.

Comparison to the semi-supervised multi-task USR method [

18] yields interesting analysis. Our supervised multi-task model achieves a 0.5% lower WER compared to USR, despite using approximately half the model size (274M vs 503M parameters) and requiring only 18% of training computation (47 vs 253 exaFLOPS), underscoring the efficiency and effectiveness of our simpler supervised framework.

Some methods have trained VSR networks on massive (often proprietary) amounts of data resulting in large improvements [

28,

29,

30,

35]. Access to these datasets is restricted, and while MultiAVSR does not perform better than these methods because of limited data, it outperforms all methods when trained on similar amounts of data. We postulate that if these larger datasets were accessible for use, our supervised multi-task training would enable even further improvements.

5.2. Language Model

Ma et al. found that an external language model (LM) is often not beneficial for AVSR and ASR as the accompanying models are fully capable without an LM [

4], however, as the VSR task is the most difficult, external LMs have frequently been proven beneficial in improving prediction accuracy. An interesting observation of the results in

Table 2 is that MultiAVSR improves less than other methods when an LM is used. As a quantitative analysis by adding an LM, USR has a relative improvement of 8% [

18], SyncVSR has on average a 7.3% relative improvement [

31], SynthVSR has a 7.1% relative improvement and MultiAVSR has on average a 3.2% relative improvement. This suggests that MultiAVSR captures richer, more robust speech representations through supervised multi-task learning, minimizing the benefit gained from external LM assistance.

Reducing the reliance on an external LM is a critical step towards real-time VSR, as the LM accounts for 18% of the total parameters during evaluation and 44% of the decoding parameters, which take more computation due to the auto-regressive nature of transformer decoders. On average, removing the external LM yields a 40% reduction in inference time, significantly enhancing the practicality of real-time VSR. This reduced LM reliance is further illustrated by the results on the WildVSR dataset.

5.3. Generalization

The WildVSR test set [

19] is designed to evaluate how well a VSR model performs on more varied, unconstrained real-world data and how effectively it generalizes beyond the LRS3-TED dataset. As seen in

Table 2, MultiAVSR outperforms all other methods with similar amounts of data, achieving a WER of 44.7% improving upon the next closest by 1.7% WER and upon the baseline model by 4.6% WER. Interestingly, our model evaluated with an additional LM performs 1.7% WER worse then without the LM on the WildVSR dataset. Our method is the first to see this disparity. These results underscore the effectiveness of our supervised multi-task learning framework in enabling robust, generalized VSR performance without reliance on external language models.

5.4. Noise Experiments

While the primary objective of this work is to enhance VSR performance, our noise robustness experiments reveal that the multi-task training framework also improves ASR and AVSR performance under noisy conditions. For these experiments, we use white and pink noise taken from the Speech Commands dataset [

41]. We compare our best model (1,968 hours) to the Auto-AVSR method which are SOTA single-task models for AVSR and ASR tasks which are trained on 3,448 hours (

more hours than MultiAVSR). Although the base WER for ASR and AVSR increases slightly with our multi-task training and shared encoders (see

Table 1), our noise experiments show that both tasks become significantly more robust under noisy conditions. Quantitatively, our multi-task framework exhibits a relative average improvement of 16.8% and 30.8% for the ASR and AVSR tasks respectively as seen in

Table 3. Notably, at an SNR of -7.5 dB—where noise exceeds signal—the AVSR model still outperforms the VSR model, achieving a WER of 14.7% under white noise conditions compared to 21.6% VSR performance. This robustness does not extend to the single-task Auto-AVSR model, where at -7.5 dB, AVSR performance degrades to a WER of 24.2%—worse than the corresponding VSR model, which achieves 19.1%. These findings underscore the effectiveness of our supervised multi-task framework in enhancing noise robustness across modalities, particularly demonstrating its superiority over single-task approaches in severely degraded acoustic environments.

6. Future Works

Our supervised multi-task framework has shown impressive improvements to VSR results and opens many future directions. Liu et al. improved VSR results by using a talking head generation model to synthesize more lip reading data from audio only datasets [

30]. Thanks to our task independent multi-task hybrid CTC/Attention loss, future work can take advantage of audio only data without needing to synthesize the visual information. This will remove the need to train a talking head generation model and to synthesize the visual data but would still use large amounts of ASR data available to improve the performance. We postulate that the additional ASR data would enable our multi-task framework to outperform other single-task methods on the ASR and AVSR tasks. Thus enabling a robust multi-task framework with no compromises on ASR or AVSR performance.

Similarly, our results indicate that shared parameters with the ASR task greatly improves VSR results. This points to another future direction of fine-tuning a large high accuracy ASR model using our multi-task framework. While fine-tuning an ASR for VSR has been done in the past [

42] it hasn’t been done in a multi-task manner which we show in this work improves robustness and generalization. We anticipate that this strategy could significantly strengthen VSR accuracy and further enhance both generalization and robustness, given that large-scale ASR models are trained on highly diverse speech corpora.

While MultiAVSR exhibits reduced reliance on external language models and thus improves inference efficiency, this work does not focus on real-time speech recognition. Recent works have found increasing network sparsity, through methods such as network pruning [

40] and mixture-of-experts [

43], improve inference time for speech recognition tasks. Merging these sparsity techniques with our supervised multi-task framework could narrow the accuracy gap with large dense models while preserving their robustness to real-world variability and delivering inference speeds suitable for real-time use.

7. Discussion

In this work, we propose MultiAVSR, a supervised multi-task training framework for robust speech recognition. Our simple multi-task hybrid CTC/Attention loss enables large improvements to the visual speech recognition (VSR) task, while requiring only 18% of train compute of other multi-task SR approaches. This framework greatly improves the VSR results with 21.0% lower WER on LRS3-TED [

33]. MultiAVSR exhibits strong generalization ability on the WildVSR dataset [

19] with an improved WER of 44.7%. Despite slightly lower base ASR and AVSR performance, MultiAVSR shows a relative improvement of 17% and 31% for the ASR and AVSR tasks respectively under diverse noise conditions. While other approaches see

relative improvement by adding an external language model, MultiAVSR has greater linguistic generalization with only a 3.2% improvement. This decreased reliance on external language models is a key step towards real-time VSR as external language models account for up to 40% of the computation required during inference. We also find that MultiAVSR is the first framework to perform better on the WildVSR dataset without an LM, further validating the claim that it has greater linguistic generalization. While some approaches with more data available perform better than MultiAVSR, our results show that supervised multi-task training exhibits strong generalization and robustness for all three speech recognition tasks and could potentially perform as well if not better if those larger proprietary datasets could be made available.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T. and D.J.L.; Methodology, S.T.; Validation, S.T.; Formal analysis, S.T., and K.W.; Investigation, S.T.; Resources, D.J.L.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.T.; Writing—review and editing, K.W. and D.J.L. ; Visualization, S.T.; Supervision, D.J.L.; Project Administration, D.J.L.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SR |

Speech recognition |

| VSR |

Visual speech recognition |

| ASR |

Audio (or automatic) speech recognition |

| AVSR |

Audio-visual speech recognition |

| WER |

Word error rate |

| LM |

Language Model |

References

- Dua, M.; Akanksha.; Dua, S. Noise robust automatic speech recognition: review and analysis. International Journal of Speech Technology 2023, 26, 475–519. [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Iseli, M.; Zhu, Q.; Alwan, A. Evaluation of noise robust features on the Aurora databases. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH, 2002, pp. 481–484.

- Haapakangas, A.; Hongisto, V.; Hyönä, J.; Kokko, J.; Keränen, J. Effects of unattended speech on performance and subjective distraction: The role of acoustic design in open-plan offices. Applied Acoustics 2014, 86, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Haliassos, A.; Fernandez-Lopez, A.; Chen, H.; Petridis, S.; Pantic, M. Auto-avsr: Audio-visual speech recognition with automatic labels. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–5.

- Rouditchenko, A.; Thomas, S.; Kuehne, H.; Feris, R.; Glass, J. mWhisper-Flamingo for Multilingual Audio-Visual Noise-Robust Speech Recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.01547 2025.

- Shi, B.; Mohamed, A.; Hsu, W.N. Learning lip-based audio-visual speaker embeddings with av-hubert. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.07180 2022.

- Sumby, W.H.; Pollack, I. Visual contribution to speech intelligibility in noise. The journal of the acoustical society of america 1954, 26, 212–215. [CrossRef]

- Cappellazzo, U.; Kim, M.; Chen, H.; Ma, P.; Petridis, S.; Falavigna, D.; Brutti, A.; Pantic, M. Large language models are strong audio-visual speech recognition learners. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025-2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2025, pp. 1–5.

- Ryumin, D.; Ivanko, D.; Ryumina, E. Audio-visual speech and gesture recognition by sensors of mobile devices. Sensors 2023, 23, 2284. [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Yu, C.; Shi, W.; Liu, L.; Shi, Y. Lip-interact: Improving mobile device interaction with silent speech commands. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, 2018, pp. 581–593.

- Srivastava, T.; Winters, R.M.; Gable, T.; Wang, Y.T.; LaScala, T.; Tashev, I.J. Whispering Wearables: Multimodal Approach to Silent Speech Recognition with Head-Worn Devices. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, 2024, pp. 214–223.

- Jin, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, X.; Choi, S.; Li, J.; Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Jin, Z. EarCommand: " Hearing" Your Silent Speech Commands In Ear. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies 2022, 6, 1–28.

- Cha, H.S.; Chang, W.D.; Im, C.H. Deep-learning-based real-time silent speech recognition using facial electromyogram recorded around eyes for hands-free interfacing in a virtual reality environment. Virtual Reality 2022, 26, 1047–1057. [CrossRef]

- Acosta, L.H.; Reinhardt, D. A survey on privacy issues and solutions for Voice-controlled Digital Assistants. Pervasive and Mobile Computing 2022, 80, 101523. [CrossRef]

- Abdolrahmani, A.; Kuber, R.; Branham, S.M. " Siri Talks at You" An Empirical Investigation of Voice-Activated Personal Assistant (VAPA) Usage by Individuals Who Are Blind. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 20th international ACM SIGACCESS conference on computers and accessibility, 2018, pp. 249–258.

- Cowan, B.R.; Pantidi, N.; Coyle, D.; Morrissey, K.; Clarke, P.; Al-Shehri, S.; Earley, D.; Bandeira, N. " What can i help you with?" infrequent users’ experiences of intelligent personal assistants. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 19th international conference on human-computer interaction with mobile devices and services, 2017, pp. 1–12.

- Pandey, L.; Hasan, K.; Arif, A.S. Acceptability of speech and silent speech input methods in private and public. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 2021, pp. 1–13.

- Haliassos, A.; Mira, R.; Chen, H.; Landgraf, Z.; Petridis, S.; Pantic, M. Unified Speech Recognition: A Single Model for Auditory, Visual, and Audiovisual Inputs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.02256 2024.

- Djilali, Y.A.D.; Narayan, S.; LeBihan, E.; Boussaid, H.; Almazrouei, E.; Debbah, M. Do VSR Models Generalize Beyond LRS3? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2024, pp. 6635–6644.

- Haliassos, A.; Zinonos, A.; Mira, R.; Petridis, S.; Pantic, M. BRAVEn: Improving Self-supervised pre-training for Visual and Auditory Speech Recognition. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024-2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2024, pp. 11431–11435.

- Haliassos, A.; Ma, P.; Mira, R.; Petridis, S.; Pantic, M. Jointly learning visual and auditory speech representations from raw data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.06246 2022.

- Hsu, W.N.; Shi, B. u-hubert: Unified mixed-modal speech pretraining and zero-shot transfer to unlabeled modality. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 21157–21170.

- Ma, P.; Mira, R.; Petridis, S.; Schuller, B.W.; Pantic, M. Lira: Learning visual speech representations from audio through self-supervision. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.09171 2021.

- Chung, J.; Nagrani, A.; Zisserman, A. VoxCeleb2: Deep speaker recognition. Interspeech 2018 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ephrat, A.; Mosseri, I.; Lang, O.; Dekel, T.; Wilson, K.; Hassidim, A.; Freeman, W.T.; Rubinstein, M. Looking to listen at the cocktail party: a speaker-independent audio-visual model for speech separation. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 2018, 37, 1–11.

- Afouras, T.; Chung, J.S.; Senior, A.; Vinyals, O.; Zisserman, A. Deep audio-visual speech recognition. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2018, 44, 8717–8727.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 conference of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics: human language technologies, volume 1 (long and short papers), 2019, pp. 4171–4186.

- Makino, T.; Liao, H.; Assael, Y.; Shillingford, B.; Garcia, B.; Braga, O.; Siohan, O. Recurrent neural network transducer for audio-visual speech recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE automatic speech recognition and understanding workshop (ASRU). IEEE, 2019, pp. 905–912.

- Serdyuk, D.; Braga, O.; Siohan, O. Transformer-Based Video Front-Ends for Audio-Visual Speech Recognition for Single and Multi-Person Video 2022.

- Liu, X.; Lakomkin, E.; Vougioukas, K.; Ma, P.; Chen, H.; Xie, R.; Doulaty, M.; Moritz, N.; Kolar, J.; Petridis, S.; et al. Synthvsr: Scaling up visual speech recognition with synthetic supervision. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 18806–18815.

- Ahn, Y.J.; Park, J.; Park, S.; Choi, J.; Kim, K.E. SyncVSR: Data-Efficient Visual Speech Recognition with End-to-End Crossmodal Audio Token Synchronization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.12233 2024.

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Xu, T.; Brockman, G.; McLeavey, C.; Sutskever, I. Robust speech recognition via large-scale weak supervision. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2023, pp. 28492–28518.

- Afouras, T.; Chung, J.S.; Zisserman, A. LRS3-TED: a large-scale dataset for visual speech recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.00496 2018.

- Ma, P.; Petridis, S.; Pantic, M. End-to-end audio-visual speech recognition with conformers. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021-2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2021, pp. 7613–7617.

- Chang, O.; Liao, H.; Serdyuk, D.; Shahy, A.; Siohan, O. Conformer is All You Need for Visual Speech Recognition. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024-2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2024, pp. 10136–10140.

- Ma, P.; Petridis, S.; Pantic, M. Visual speech recognition for multiple languages in the wild. Nature Machine Intelligence 2022, 4, 930–939. [CrossRef]

- Bulat, A.; Tzimiropoulos, G. How far are we from solving the 2d & 3d face alignment problem?(and a dataset of 230,000 3d facial landmarks). In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 1021–1030.

- Varga, A.; Steeneken, H.J. Assessment for automatic speech recognition: II. NOISEX-92: A database and an experiment to study the effect of additive noise on speech recognition systems. Speech communication 1993, 12, 247–251. [CrossRef]

- Son Chung, J.; Senior, A.; Vinyals, O.; Zisserman, A. Lip reading sentences in the wild. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 6447–6456.

- Fernandez-Lopez, A.; Chen, H.; Ma, P.; Haliassos, A.; Petridis, S.; Pantic, M. SparseVSR: Lightweight and noise robust visual speech recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.04552 2023.

- Warden, P. Speech commands: A dataset for limited-vocabulary speech recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.03209 2018.

- Afouras, T.; Chung, J.S.; Zisserman, A. Asr is all you need: Cross-modal distillation for lip reading. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2020, pp. 2143–2147.

- Kim, S.; Jang, K.; Bae, S.; Cho, S.; Yun, S.Y. MoHAVE: Mixture of Hierarchical Audio-Visual Experts for Robust Speech Recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.10447 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).