Submitted:

12 February 2024

Posted:

13 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Is applying erosion to the spectrograms has significant effect to speech recognition model?

- Which noisy reduction mechanism is better from spectral subtraction, subspace filtering and both in combined?

- Which deep learning algorithm (from LSTM, BILSTM, GRU and BiGRU) performs better to build an end-to-end speech recognition model for Amharic?

2. Methods and Materials

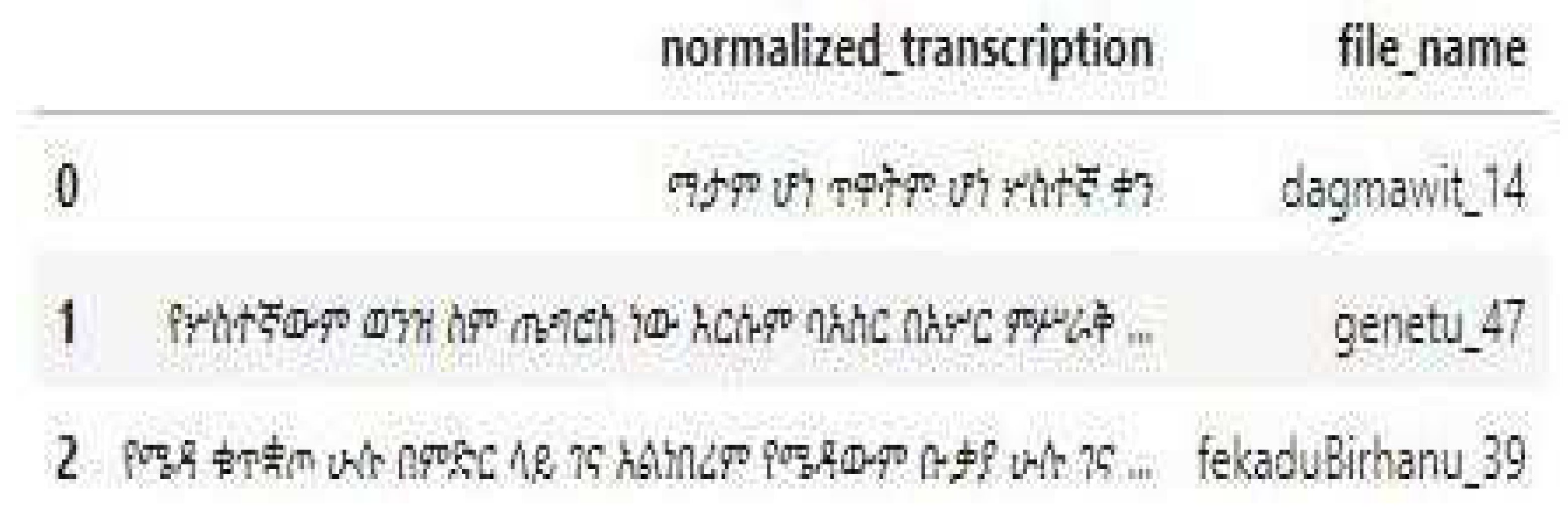

2.1. Data Collection and Processing

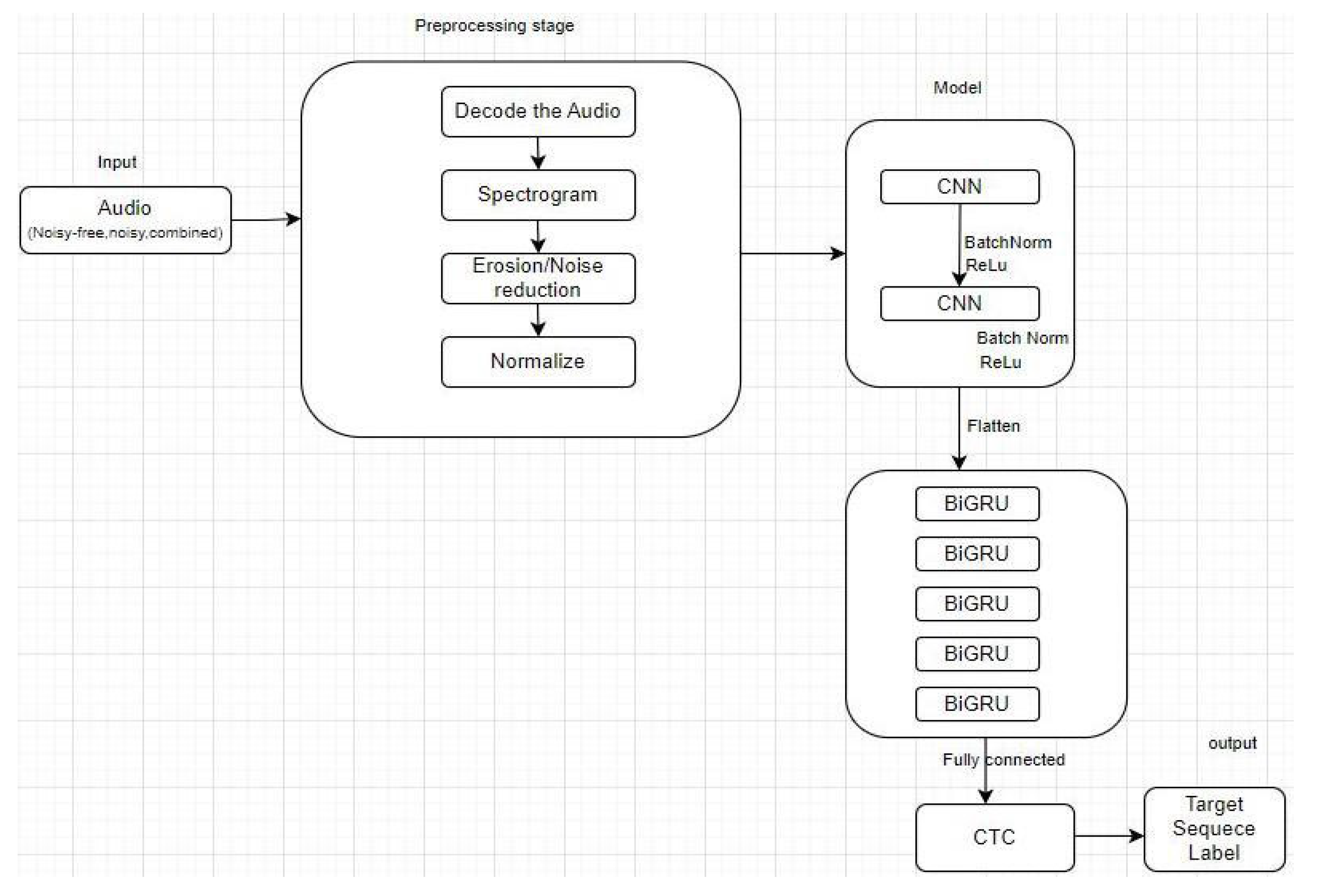

2.2. Model Architecture

2.3. Model Implementation

2.4. Model Compilation

2.5. Evaluation Metric

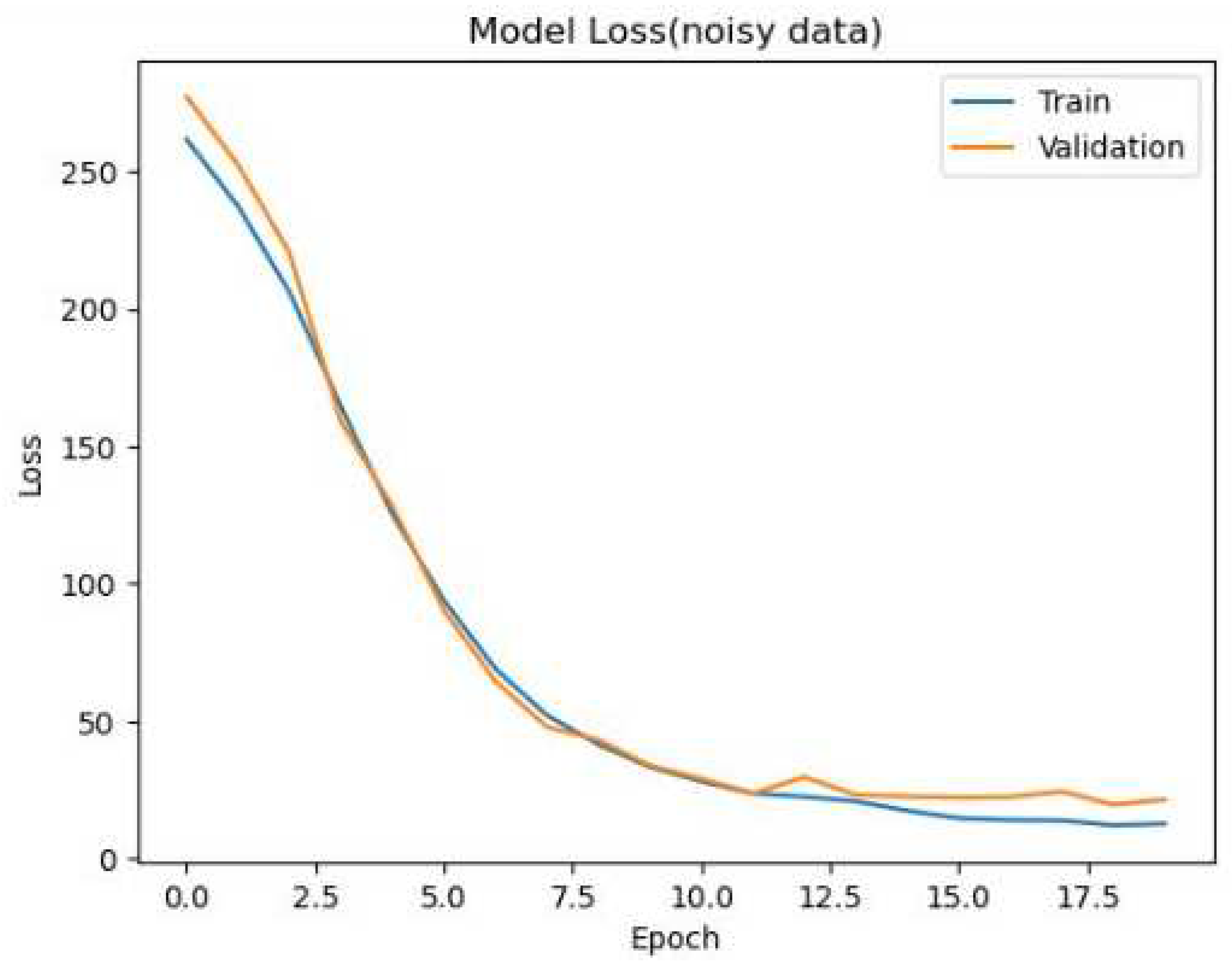

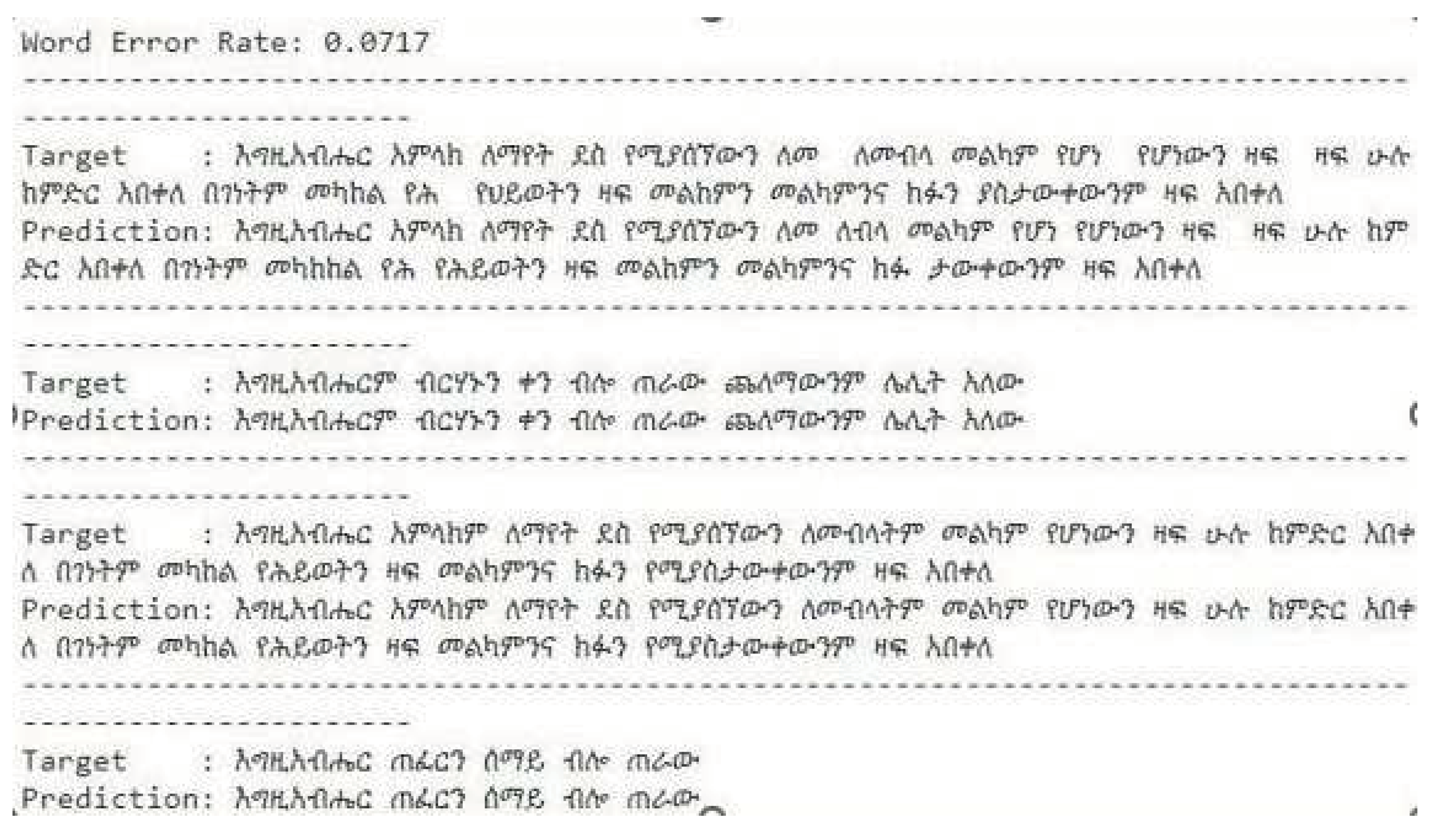

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Error Analysis

5. Conclusions

Data Availability

Conflict of Interest

Funding Statement

Institutional Review Board (IRB) Statement

Informed Consent Statement

References

- Abate, S. T. (2005). Automatic Speech Recognition for Ahmaric. PhD dissertation. Hamburg University, Germany.

- Abebe Tsegaye (2019). Designing automatic speech recognition for Ge’ez language. Master’s thesis. Bahir Dar, Ethiopia.

- Azmeraw Dessalegn (2019). Syllable-based speaker-independent continuous speech recognition for Afan Oromo. Master’s thesis. Bahir Dar, Ethiopia.

- Bahl, L., Brown, P., De Souza, P. V., and Mercer, R. (1986). Maximum mutual information estimation of hidden Markov model parameters for speech recognition. In Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, IEEE International Conference on ICASSP ’86 (pp. 49–52). [CrossRef]

- Bisani, M., & Ney, H. (2005). Open vocabulary speech recognition with flat hybrid models. In INTERSPEECH (pp. 725–728).

- Bourlard, H. A., & Morgan, N. (1993). Connectionist Speech Recognition: A Hybrid Approach. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Norwell, MA, USA. ISBN 0792393961.

- Davis, S., & Mermelstein, P. (1980). Comparison of parametric representations for monosyllabic word recognition in continuously spoken sentences. IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, 28(4), 357–366.

- Baye, A., Tachbelie, Y., & Besacier, L. (2021). End-to-end Amharic speech recognition using LAS architecture. In Proceedings of the 12th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (pp. 4058-4065). European Language Resources Association.

- Dumitru, C. O., & Gavat, I. (2006, June). A Comparative Study of Feature Extraction Methods Applied to Continuous Speech Recognition in Romanian Language. In Multimedia Signal Processing and Communications, 48th International Symposium ELMAR-2006 (pp. 115-118). IEEE.

- Furui, S., Ichiba, T., Shinozaki, T., Whittaker, E. W., & Iwano, K. (2005). Cluster-based modeling for ubiquitous speech recognition. Interspeech 2005, 2865-2868.

- Galescu, L. (2003). Recognition of out-of-vocabulary words with sub-lexical language models. In INTERSPEECH.

- Gebremedhin, Y. B., Duckhorn, F., Hoffmann, R., & Kraljevski, I. (2013). A new approach to develop a syllable-based, continuous Amharic speech recognizer. July, 1684–1689.

- Graves, A. (2012). Supervised Sequence Labelling with Recurrent Neural Networks, volume 385 of Studies in Computational Intelligence. Springer.

- Hebash H.O. Nasereddin, A. A. (January 2018). Classification techniques for automatic speech recognition (ASR) algorithms used with real-time speech translation. 2017 Computing Conference. London, UK: IEEE.

- Hinton, G., Deng, L., Yu, D., Dahl, G., Mohamed, A. r., Jaitly, N., Senior, A., Vanhoucke, V., Nguyen, P., Sainath, T., & Kingsbury, B. (2012). Deep neural networks for acoustic modeling in speech recognition. Signal Processing Magazine.

- Jaitly, N., & Hinton, G. E. (2011). Learning a better representation of speech soundwaves using restricted Boltzmann machines. In ICASSP (pp. 5884–5887).

- Pokhariya, J. S., & D. S. (2014). Sanskrit Speech Recognition using Hidden Markov Model Toolkit. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology, 3(10).

- Kebebew, T. (2010). Speaker-dependent speech recognition for Afan Oromo using hybrid hidden Markov models and artificial neural network. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Addis Ababa University.

- Solomon Teferra Abate, W. M. (n.d.). Automatic Speech Recognition for an UnderResourced Language – Amharic. Department of Informatics, Natural Language Systems Group, University of Hamburg, Germany.

- Teferra, S., & Menzel, W. (2007). Syllable-based speech recognition for Amharic. June, 33–40.

- Tohye, T. G. (2015). Towards Improving the Performance of Spontaneous Amharic Speech Recognition. Master's thesis. Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Yifru, M. (2003). Application of Amharic Speech Recognition System to Command. Master's thesis. Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Graves, A., Fernández, S., Gomez, F., & Schmidhuber, J. (2006). Connectionist Temporal Classification: Labelling Unsegmented Sequence Data with Recurrent Neural Networks. In ICML, pages 369–376. ACM.

- Jurafsky, D., & Martin, J. H. (2009). Speech and Language Processing (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Huang, X., Acero, A., & Hon, H. W. (2001). Spoken Language Processing: A Guide to Theory, Algorithm, and System Development. Prentice Hall PTR.

- Graves, A., Mohamed, A.-r., & Hinton, G. (2013). Speech Recognition with Deep Recurrent Neural Networks. In IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (pp. 6645–6649).

- Hinton, G., Deng, L., Yu, D., Dahl, G. E., Mohamed, A.-r., Jaitly, N., Senior, A., Vanhoucke, V., Nguyen, P., Sainath, T. N., & Kingsbury, B. (2012). Deep Neural Networks for Acoustic Modeling in Speech Recognition: The Shared Views of Four Research Groups. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 29(6), 82–97.

- Graves, A., & Jaitly, N. (2014). Towards End-to-End Speech Recognition with Recurrent Neural Networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 1764–1772).

- Jelinek, F., & Mercer, R. L. (1980). Interpolated Estimation of Markov Source Parameters from Sparse Data. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Pattern Recognition in Practice (pp. 381–397).

- Deng, L., & Yu, D. (2014). Deep Learning: Methods and Applications. Foundations and Trends in Signal Processing.

- Young, S., Evermann, G., Gales, M., Hain, T., Kershaw, D., Liu, X., Moore, G., Odell, J., Ollason, D., Povey, D., Valtchev, V., & Woodland, P. (2006). The HTK Book (for HTK Version 3.4). Cambridge University Engineering Department.

- Abdel-Hamid, O., & Jiang, H. (2013). Fast speaker adaptation of deep neural networks using model compression. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (pp. 7822-7826). IEEE.

- Chavan, S., & Sable, P. (2013). Speech recognition using hidden Markov model. International Journal of Engineering Research and Applications, 3(4), 2319-2324.

- Novoa, J., Lleida, E., & Hernando, J. (2018). A comparative study of HMM-based and DNN-based ASR systems for under-resourced languages. Computer Speech & Language, 47, 1-22.

- Palaz, D., Kılıç, R., & Yılmaz, E. (2019). A comparative study of deep neural network and hidden Markov model based acoustic models for Turkish speech recognition. Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences.

- Lee, K., & Kim, H. (2019). Dynamic Wrapping for Robust Speech Recognition in Adverse Environments. IEEE Access, 7, 129541-129550.

- Wang, Y., & Wang, D. (2019). A novel dynamic wrapping method for robust speech recognition under noisy environments. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, 10(5), 1825-1834.

- Chorowski, J. K., Bahdanau, D., Serdyuk, D., Cho, K., & Bengio, Y. (2015). Attention-based models for speech recognition. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 577-585).

- Kim, J., Park, S., Kang, K., & Lee, H. (2017). Joint CTC-attention based end-to-end speech recognition using multi-task learning.

- Zhang, Y., Deng, K., Cao, S., & Ma, L. (2021). Improving Hybrid CTC/Attention End-to-end Speech Recognition with Pretrained Acoustic and Language Model.

- Deng, K., Zhang, Y., Cao, S., & Ma, L. (2022). Improving CTC-based speech recognition via knowledge transferring from pre-trained language models.

- Chen, C. (2021). ASR Inference with CTC Decoder. PyTorch.

- Hannun, A., Case, C., Casper, J., Catanzaro, B., Diamos, G., Elsen, E., … & Prenger, R. (2014). Deep speech: Scaling up end-to-end speech recognition.

- Igor Macedo Quintanilha (2017). End-to-end speech recognition applied to Brazilian Portuguese using deep learning.

- Hanan Aldarmaki, Asad Ullah, and Nazar Zaki (2021). Unsupervised Automatic Speech Recognition: A Review. arXiv.org, 2021, arxiv.org/abs/2106.04897.

- Abdelrahma Ahmed, Yasser Hifny, Khaled Shaalan, and Sergio Tolan (2016). Lexicon Free Arabic Speech Recognition. link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-48308-5_15.

- Wren, Y., Titterington, J., & White, P. (2021). How many words make a sample? Determining the minimum number of word tokens needed in connected speech samples for child speech assessment. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 35(8), 761-778. [CrossRef]

- Malik, M., Malik, M. K., Mehmood, K., & Makhdoom, I. (2021). Automatic speech recognition: a survey. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 80(6), 9411-9457. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., & Wang, H. (2011). A syllable-based connected speech recognition system for Mandarin. In 2011 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) (pp. 4856-4859). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. I., & Zahid, S. (2012). A comparative study of speech recognition techniques for Urdu language. International Journal of Speech Technology, 15(4), 497-504. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H., & Chen, C.-W. (2010). A novel speech recognition system based on a self-organizing feature map and a fuzzy expert system. Microprocessors and Microsystems, 34(6), 242-251. [CrossRef]

- Ge, X., Wu, L., Xia, D., & Zhang, P. (2013). A multi-objective HSA of nonlinear system modeling for hot skip-passing. In 2013 Sixth International Conference on Advanced Computational Intelligence (ICACI) (pp. 1-6). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Villa, A. E. P., Masulli, P., & Pons Rivero, A. J. (Eds.). (2016). Artificial neural networks and machine learning – ICANN 2016: 25th International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Barcelona, Spain, September 6-9, 2016, Proceedings, Part I. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., & Hu, Y. (2012). Learning optimal warping window size of DTW for time series classification. In 2012 11th International Conference on Information Science, Signal Processing, and their Applications (ISSPA) (pp. 1-4). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, M., Loos, P., & Pastor, O. (Eds.). (2016). Business Process Management: 14th International Conference, BPM 2016, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, September 18-22, 2016. Proceedings. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V. N. (2016). A framework for business process improvement: A case study of a Norwegian manufacturing company (Master’s thesis). University of Stavanger. https://brage.bibsys.no/xmlui/bitstream/id/430871/16-00685-3%20Van%20Nhan%20Nguyen%20-%20Master’s%20Thesis.pdf%20266157_1_1.pdf.

- LeCun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y., & Haffner, P. (1998). Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE, 86(11), 2278-2324. [CrossRef]

- Ientilucci, E. J. (2006). Statistical models for physically derived target sub-spaces. In S. S. Shen & P. E. Lewis (Eds.), Imaging Spectrometry XI (Vol. 6302, p. 63020A). SPIE. [CrossRef]

- Begel, A., & Bosch, J. (2013). The DevOps phenomenon. Communications of the ACM, 56(11), 44-49. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2113113.2113141.

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., & Courville, A. (2016). Deep Learning. MIT Press.

- Scherzer, O. (Ed.). (2015). Handbook of mathematical methods in imaging (2nd ed.). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Persagen Consulting. (n.d.). Machine learning. https://persagen.com/files/ml.html.

- Saha, S. K., & Tripathy, A. K. (2017). Automated IT system failure prediction: A deep learning approach. International Journal of Computer Applications, 159(9), 1–6. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313456329_Automated_IT_system_failure_prediction_A_deep_learning_approach.

- Kotera, J., Šroubek, F., & Milanfar, P. (2013). Blind deconvolution using alternating maximum a posteriori estimation with heavy-tailed priors. In A. Petrosino, L. Maddalena, & P. Soda (Eds.), Computer analysis of images and patterns (pp. 59–66). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Artificial intelligence. (2022, January 5). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_intelligence.

- Mwiti, D. (2019, September 4). A 2019 guide for automatic speech recognition. Heartbeat. https://heartbeat.fritz.ai/a-2019-guide-for-automatic-speech-recognition-f1e1129a141c.

- Persagen. (n.d.). Machine learning. Retrieved January 6, 2022, from https://persagen.com/files/ml.html.

- Klein, A., & Kienle, A. (2012). Supporting distributed software development by modes of collaboration. Multimedia Systems, 18(6), 509–520. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., & Cong, J. (2017). DAPlace: Data-aware three-dimensional placement for large-scale heterogeneous FPGAs. In 2017 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design (ICCAD) (pp. 236–243). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, H., Lin, H., & Zhang, Y. (2017). A new method for remote sensing image registration based on SURF and GMS. Remote Sensing, 9(3), 298. [CrossRef]

- Schmidhuber, J. (2000). How to count time: A simple and general neural mechanism. ftp://ftp.idsia.ch/pub/juergen/TimeCount-IJCNN2000.pdf.

- Goodfellow, I., Pouget-Abadie, J., Mirza, M., Xu, B., Warde-Farley, D., Ozair, S., Courville, A., & Bengio, Y. (2014). Generative adversarial nets. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1406.1078v3.pdf.

- Srivastava, A. (2018, November 14). Basic architecture of RNN and LSTM. PyDeepLearning. https://pydeeplearning.weebly.com/blog/basic-architecture-of-rnn-and-lstm.

- Graves, A., Mohamed, A.-R., & Hinton, G. (2013). Speech recognition with deep recurrent neural networks. 2013 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 6645–6649. https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~graves/asru_2013.pdf.

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., Zhang, J., & Li, H. (2020). A survey on deep learning for named entity recognition. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 32(9), 1635–1658.

- Papers with Code. (n.d.). BiLSTM. https://paperswithcode.com/method/bilstm.

- Olah, C. (2015, August 27). Understanding LSTM networks. http://colah.github.io/posts/2015-08-Understanding-LSTMs/.

| Experiment | Noisy Data |

|---|---|

| Spectral Subtraction | WER = 8.5% |

| Subspace Filtering | WER =7.4% |

| Combined (Spectral+Subspace) | WER = 7% |

| Without Noise- reduction technique | WER = 10.5% |

| Model | WER (%) | Number of Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| BIGRU | 5 | 26,850,905 |

| BILSTM | 7 | 36,435,678 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).