Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Application of CTI in Network Security

2.2. Attack Reconstruction Approaches

2.3. Automated Attack Scenario Generation

2.4. Research Gap: Automated Threat Intelligence Platform

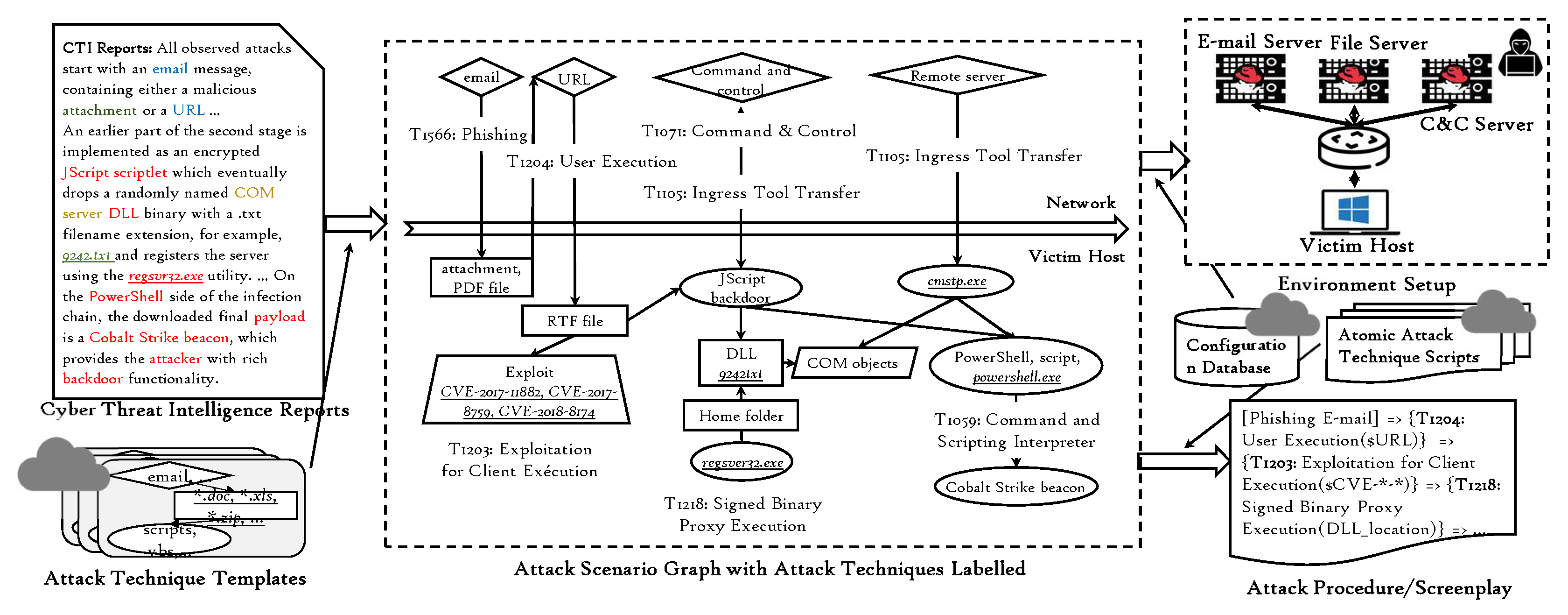

3. CTI-Based Automated Attack Reconstruction

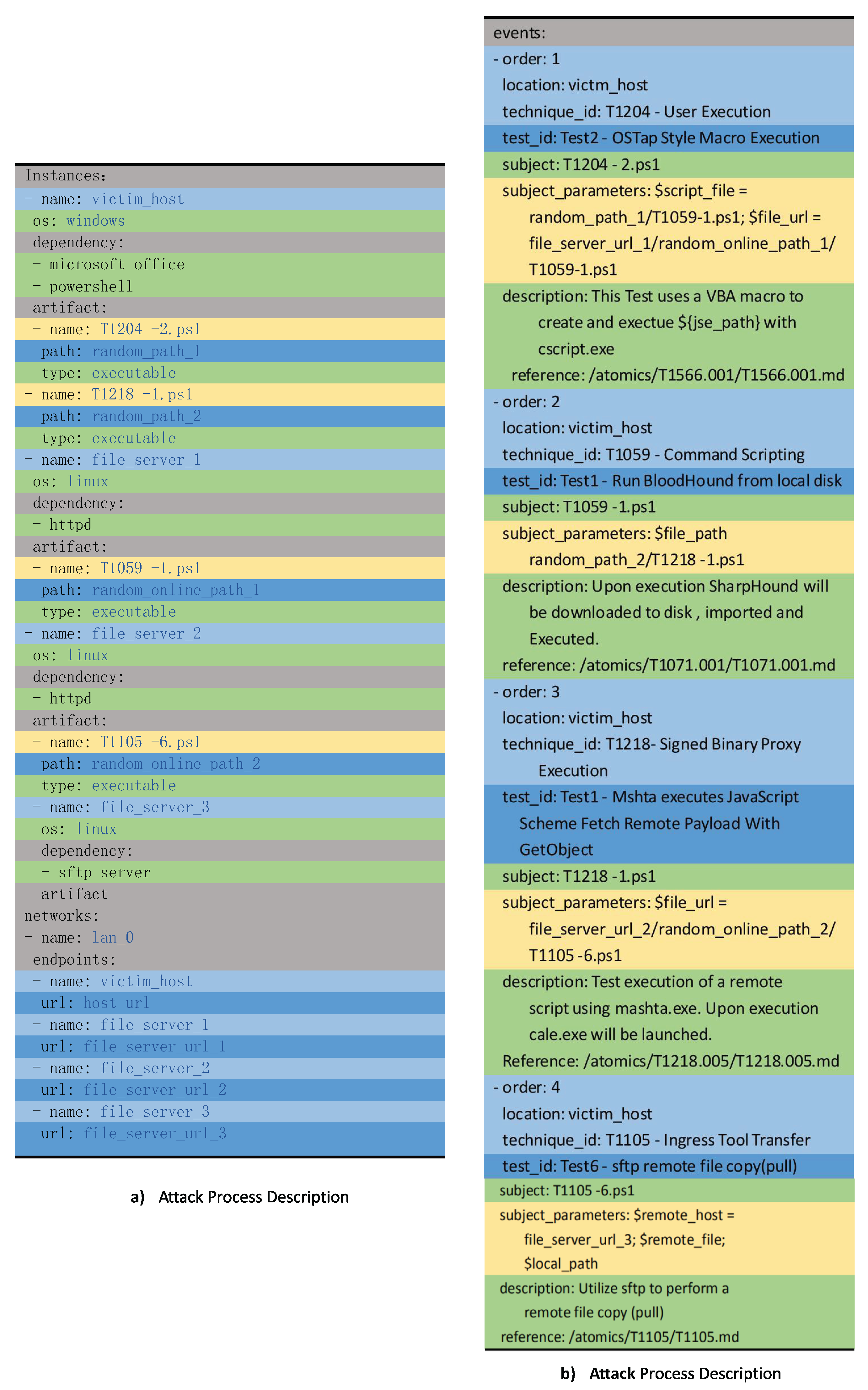

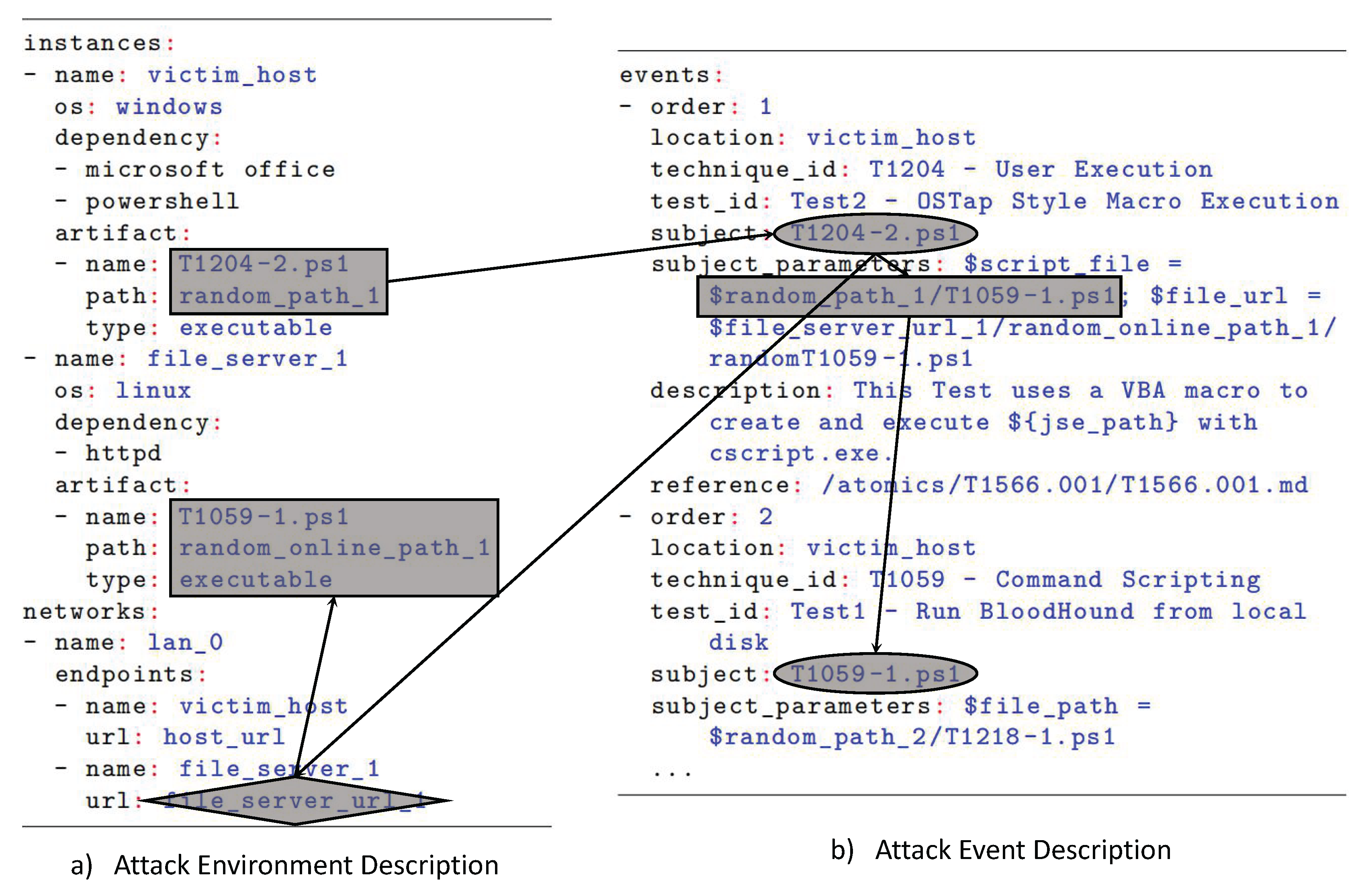

3.1. Standardized Attack Description

3.2. Attack Scenario Retrieval

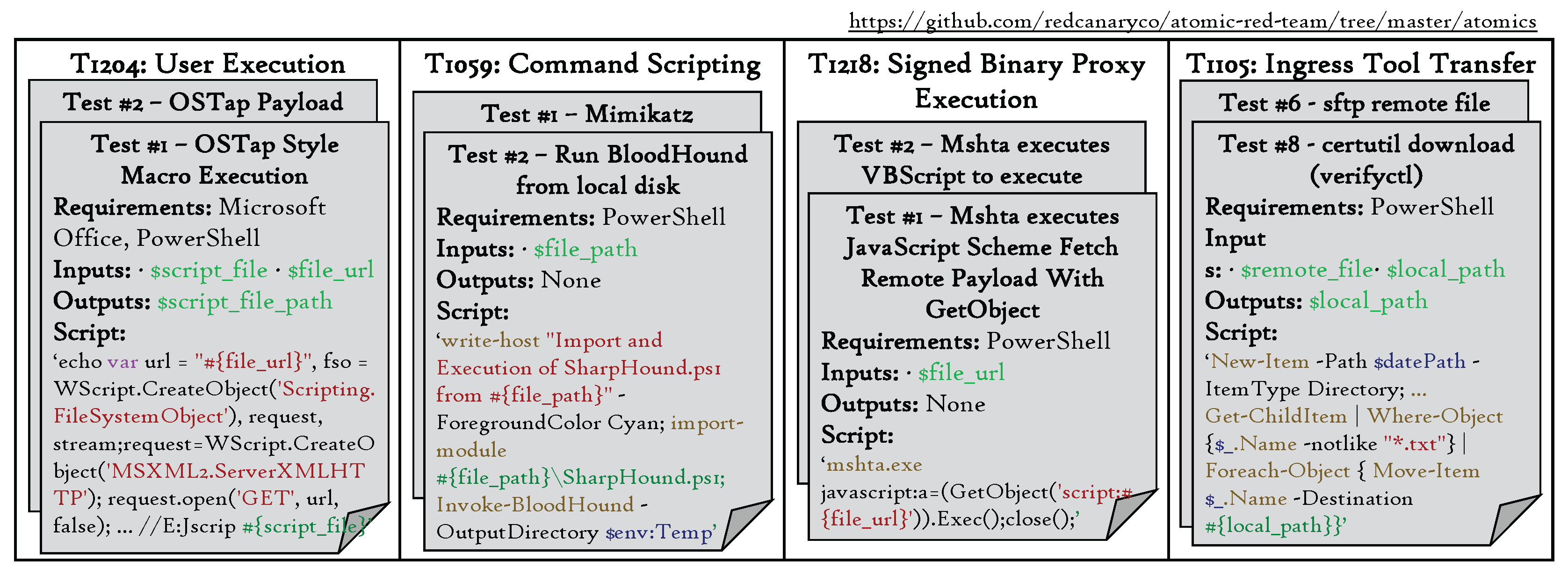

3.3. Attack Reconstruction with Atomic Attack Techniques

3.4. Execution Environment Building

4. Evaluation

4.1. Evaluation Setup

4.2. Evaluation Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Advantages

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Future Work

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Verizon Business. 2023 Data Breach Investigations Report. Verizon Business Security Publications 2023. URL:https://www.verizon.com/business/resources/reports/dbir/.

- González-Granadillo, G.; González-Zarzosa, S.; Diaz, R. Security Information and Event Management (SIEM): Analysis, Trends, and Usage in Critical Infrastructures. Sensors 2021, 21(14), 4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, H.; Singh, G.; Sharma, S.; Alshamrani, S. S. Evolution of Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) in Cyber Security: A Comprehensive Review. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 556, 04001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, M. J.; Kent, A. D.; Hash, C. Unified Host and Network Data Set. In Data Science for Cyber-Security; World Scientific: Singapore, 2019; pp 1–22.

- SANS Institute. 2022 Cybersecurity Trends: Operationalizing Threat Intelligence. SANS White Paper Series 2022, WP-2022-045, 1–32. URL: https://www.sans.org/white-papers/38600/.

- Sheyner, O.; Haines, J.; Jha, S.; Lippmann, R.; Wing, J.M. A Graph-Based System for Network-Vulnerability Analysis. IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy 2002, 273–284.

- Phillips, C.; Swiler, L.P. A Requires/Provides Model for Computer Attacks. Proceedings of the 2000 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy 2000, 110–122.

- Barnum, S. Standardizing Cyber Threat Intelligence Information with the Structured Threat Information Expression (STIX). MITRE Corporation 2012, 1–22.

- Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M. Automated Adversary Emulation for Cyber-Physical Systems via Reinforcement Learning. Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security 2020, 837–850.

- Li, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y. Empowering Vulnerability Prioritization: A Heterogeneous Graph-Driven Framework for Exploitability Prediction. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 2023, 20(3), 1987–2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, R.; Zhao, Q.; Lin, M. A Causal Graph-Based Approach for APT Predictive Analytics. Computers & Security 2023, 45(2), 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, B.; Liu, F.; Zhang, R. Automated Discovery and Mapping ATT&CK Tactics and Techniques for Unstructured Cyber Threat Intelligence. Applied Sciences 2024, 14(2), 123–138.

- Burger, E. W.; Goodman, M. D.; Kampanakis, P.; Zhu, K. A. Taxonomy Model for Cyber Threat Intelligence Information Exchange Technologies. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM Workshop on Information Sharing & Collaborative Security; ACM: New York, 2014; pp 51–60.

- Wagner, C.; Dulaunoy, A.; Wagener, G.; Iklody, A. MISP: The Design and Implementation of a Collaborative Threat Intelligence Sharing Platform. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Workshop on Information Sharing and Collaborative Security; ACM: New York, 2016; pp 49–56.

- Sarker, I. H. AI-Driven Cybersecurity and Threat Intelligence: Cyber Automation, Intelligent Decision-Making and Explainability. Springer Nature: Cham, 2024.

- de Melo e Silva, A.; da Silva, M. M.; Rosa, R. L.; Zegarra Rodríguez, D. A Methodology to Evaluate Standards and Platforms Within Cyber Threat Intelligence. Future Internet 2020, 12 (6), 108. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, A. Research on Ontology-Based Cyber Threat Intelligence Analysis Technology. J. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2020, 56(11), 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Korban, C. A.; Baker, B.; Bodeau, D.; Graubart, R. APT3 Adversary Emulation Plan. MITRE: McLean, VA, USA, 2017.

- Hutchins, E. M.; Cloppert, M. J.; Amin, R. M. Intelligence-Driven Computer Network Defense Informed by Analysis of Adversary Campaigns and Intrusion Kill Chains. In Leading Issues in Information Warfare & Security Research; Academic Publishing International: Reading, UK, 2011; Vol. 1, pp 80–106.

- Vagrant—Development Environments Made Easy. https://www.vagrantup.com/ (accessed 2024-06-01).

- Morris, K. Infrastructure as Code: Managing Servers in the Cloud; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2016.

- Martínez, J.; Durán, J. M. Software Supply Chain Attacks, a Threat to Global Cybersecurity: SolarWinds’ Case Study. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Eng. 2021, 11(5), 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christl, K.; Tarrach, T. The Analysis Approach of ThreatGet. arXiv:2107.09986, 2021.

- Cohen, D.; Nissim, N.; Glezer, C. Human–AI Enhancement of Cyber Threat Intelligence. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2025, 24(2), 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, B.; Tall, A.; Olsen, D. National Cyber Range Overview. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Military Communications Conference; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, 2014; pp 123–128.

- MITRE ATT&CK Evaluations. https://attackevals.mitre-engenuity.org/ (accessed 2024-06-01).

- SimuLand. https://github.com/Azure/SimuLand (accessed 2024-06-01).

- Detection Lab. https://github.com/clong/DetectionLab (accessed 2024-06-01).

- Uetz, R.; Hemminghaus, C.; Hackländer, L.; Schlipper, P.; Henze, M. Reproducible and Adaptable Log Data Generation for Sound Cybersecurity Experiments. In Proceedings of the Annual Computer Security Applications Conference; ACM: New York, 2021.

- Landauer, M.; Skopik, F.; Wurzenberger, M.; Rauber, A. Have It Your Way: Generating Customized Log Datasets With a Model-Driven Simulation Testbed. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2021, 70(1), 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.; O’Gorman, J.; Kearns, D.; Aharoni, M. Metasploit: The Penetration Tester’s Guide; No Starch Press: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011.

- Atomic Red Team. https://github.com/redcanaryco/atomic-red-team (accessed 2024-06-01).

- Bui, T. Analysis of Docker Security. arXiv:1501.02967, 2015.

- Nieh, J.; Leonard, O. C. Examining VMware. Dr. Dobb’s J. 2000, 25(8), 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Barceloux, D. G.; Barceloux, D. Cobalt. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1999, 37(2), 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

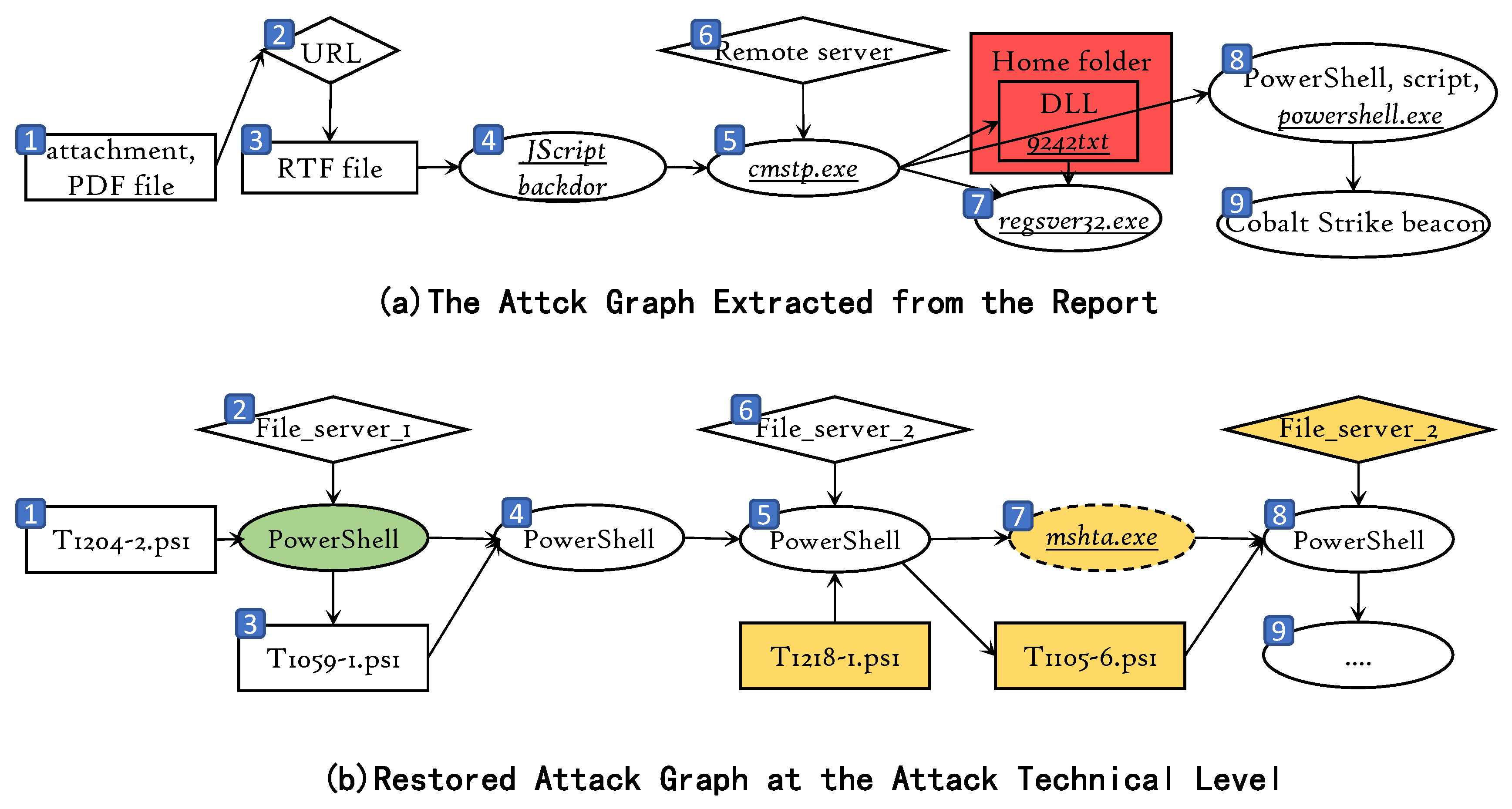

- Dahan, A. Operation Cobalt Kitty: A Large-Scale APT in Asia Carried Out by the OceanLotus Group. https://www.cybereason.com/blog/operation-cobalt-kitty-apt (accessed 2024-06-01).

- Shelley, M.; Bolton, G. Frankenstein. In Medicine and Literature, Volume Two; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp 35–52.

- Clark, D. D. The Design Philosophy of the DARPA Internet Protocols. ACM SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 1988, 18(4), 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Dumitras, T. Chainsmith: Automatically Learning the Semantics of Malicious Campaigns by Mining Threat Intelligence Reports. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), London, UK, 24–26 April 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp 355–371. [CrossRef]

- Stamm, M. C.; Zhao, X. Anti-Forensic Attacks Using Generative Adversarial Networks. In Multimedia Forensics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp 467–489.

- Li, Z.; Zeng, J.; Chen, Y.; Liang, Z. AttacKG: Constructing Technique Knowledge Graph from Cyber Threat Intelligence Reports. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.07093. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2111.07093v1.

- Husari, G.; Al-Shaer, E.; Chu, B.; Rahman, R. F. Learning APT Chains from Cyber Threat Intelligence. In Proceedings of the 6th Annual Symposium on Hot Topics in the Science of Security, Nashville, TN, USA, 1–3 April 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3314058.3317728. [CrossRef]

Completely satisfied,

Completely satisfied, Partially satisfied,

Partially satisfied, Dissatisfied).

Dissatisfied).

Completely satisfied,

Completely satisfied, Partially satisfied,

Partially satisfied, Dissatisfied).

Dissatisfied).| Attack Examples | Attack Reconstruction | |||||

|

Real

Examples |

Full-Cycle

Attack Chain Reconstruction |

Randomization |

Batch

Automation |

Repeatable with Explicit Procedures |

Open

Source Tools |

|

| National Cyber Range |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| ATTCK Evaluations |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| SimuLand |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Detection Lab |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| SOCBED |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Landauer et al. |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Our work |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Attack Cases |

Attack Flow | Environment Configuration |

|||

| Order | Involving Technology |

Number of Implementations |

Used Implementation |

||

| Cobalt Campaign |

1 | T1566-Phishing | 0 | _ | -Victim host: |

| 2 | T1204-User Execution | 9 | Test#2-OSTap Payload Download | os:Windows | |

| 3 | T1203-Exploitation for Execution | 0 | _ | dependencies: | |

| 4 | T1071-Command Control | 7 | Test#1-Malicious User Agents-Powershell | PowerShell,Word | |

| 5 | T1105-Ingress Tool Transfer | 20 | Test#15-File Download via PowerShell | -File server: | |

| 6 | T1218-Signed Binary Proxy Execution | 70 | Test#3-Rundll32 advpack.dll Execution | os:Linux | |

| 7 | T1105-Ingress Tool Transfer | 20 | Test#4-scp remote file copy | -Http server: | |

| 8 | T1059-Command and Scripting | 36 | Test#2-Run BloodHound from local disk | os:Linux | |

| 9 | T1027-Obfuscation | 8 | Test#1-Decode base64 Data into Script | dependencies:httpd | |

| OceanLotus Campaign |

1 | T1105-Ingress Tool Transfer | 20 | Test#5-sftp remote file copy | -Victim host: |

| 2 | T1218-Signed Binary Proxy Execution | 70 | Test#5-Invoke CHM Simulate Double Click | os:Windows | |

| 3 | T1027-Obfuscation | 8 | Test#4-Execution from Compressed File | dependencies: | |

| 4 | T1574-Hijack Execution Flow | 6 | Test#1-DLL Search Order Hijacking-amsi.dll | PowerShell | |

| 5 | T1005-Data from Local System | 0 | _ | -File server: | |

| Frankenstein Campaign |

1 | T1566-Phishing | 0 | _ | os:Linux |

| 2 | T1204-User Execution | 9 | Test#1-OSTap Style Macro Execution | -Victim host: | |

| 3 | T1203-Exploitation for Execution | 0 | _ | os:Windows | |

| 4 | T1547-Boot Autostart(Registry Run Keys) | 9 | Test#1-Reg Key Run | dependencies: | |

| 5 | T1218-Signed Binary Proxy Execution | 70 | Test#10-Mshta used to Execute PowerShell | PowerShell | |

| 6 | T1059-Command and Scripting | 36 | Test#1-Create and Execute Batch Script | -File server: | |

| 7 | T1027-Obfuscation | 8 | Test#7-Obfuscated Command in PowerShell | os:Linux | |

| 8 | T1105-Ingress Tool Transfer | 20 | Test#7-certutil download | ||

| TC Nginx Drakon APT |

1 | T1566-Phishing | 0 | _ | |

| 2 | T1071-Command Control | 7 | Test#3-Malicious User Agents -Nix | -Victim host: | |

| 3 | T1003-OS Credential Dumping | 37 | Test#1-Cached Credential Dump via Cmdkey | os:Windows | |

| 4 | T1082-System Information Discovery | 11 | Test#1-System Information Discovery | dependencies: | |

| 5 | T1105-Ingress Tool Transfer | 20 | Test#9-Windows-BITSAdmin BITS Download | PowerShell | |

| 6 | T1059 - Command & Scripting | 36 | Test#19-PowerShell Command Execution | -File server: | |

| 7 | T1068 - Privilege | 0 | _ | os:Linux | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).