Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

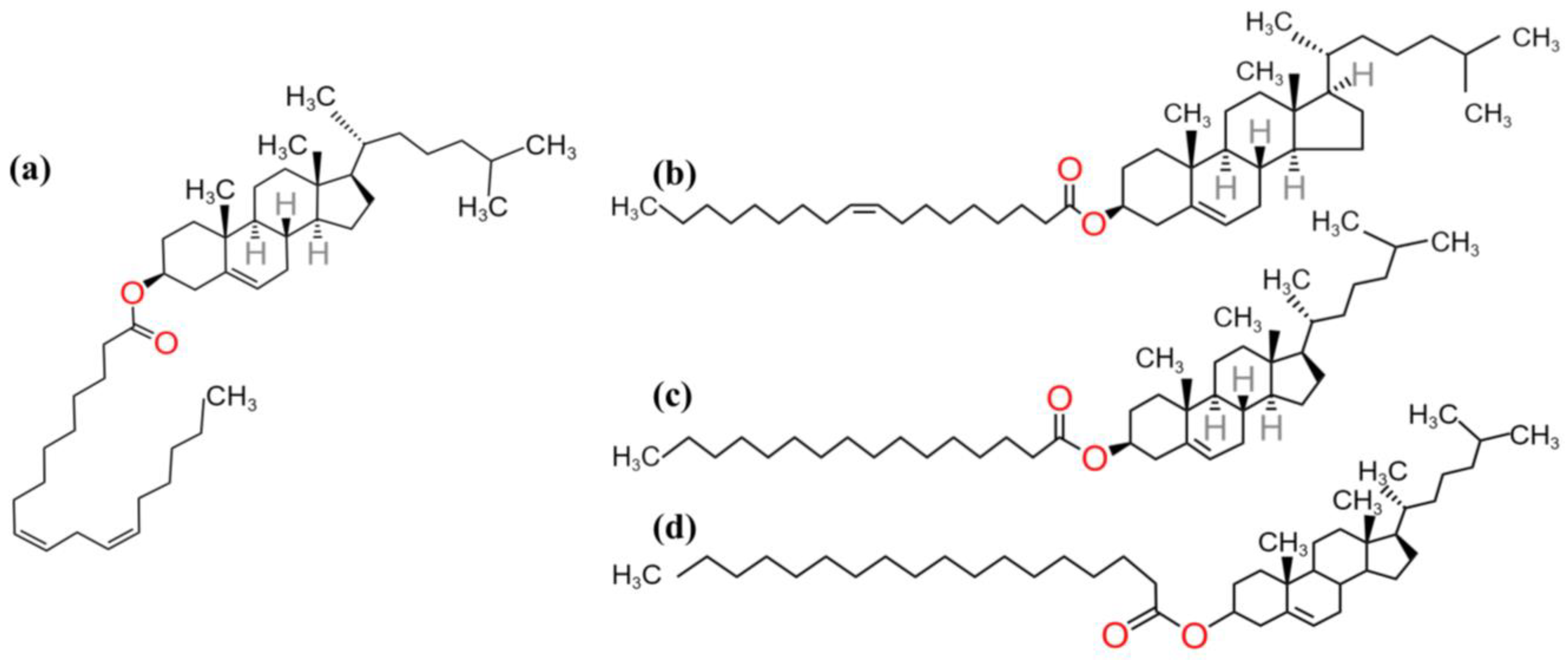

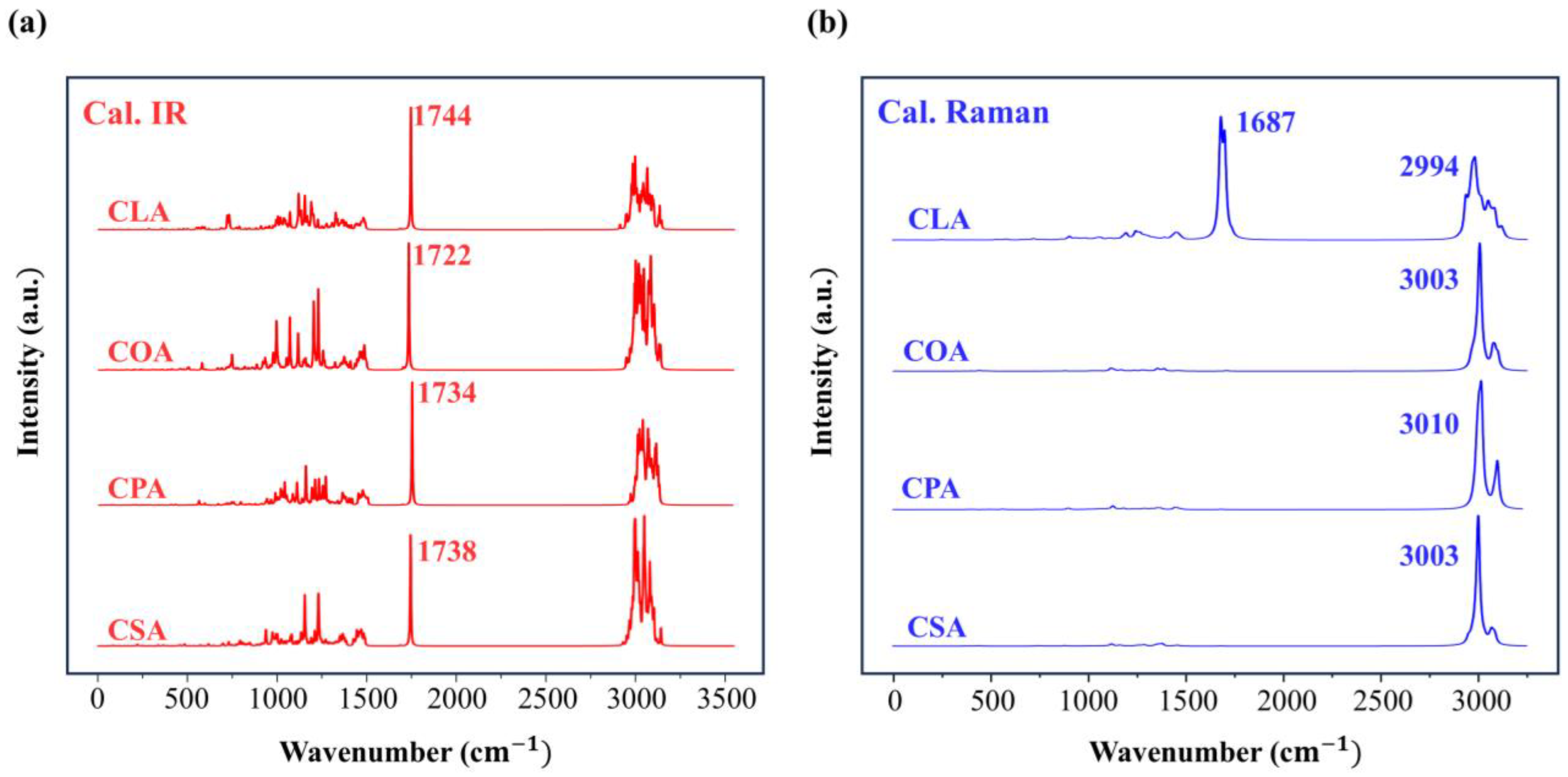

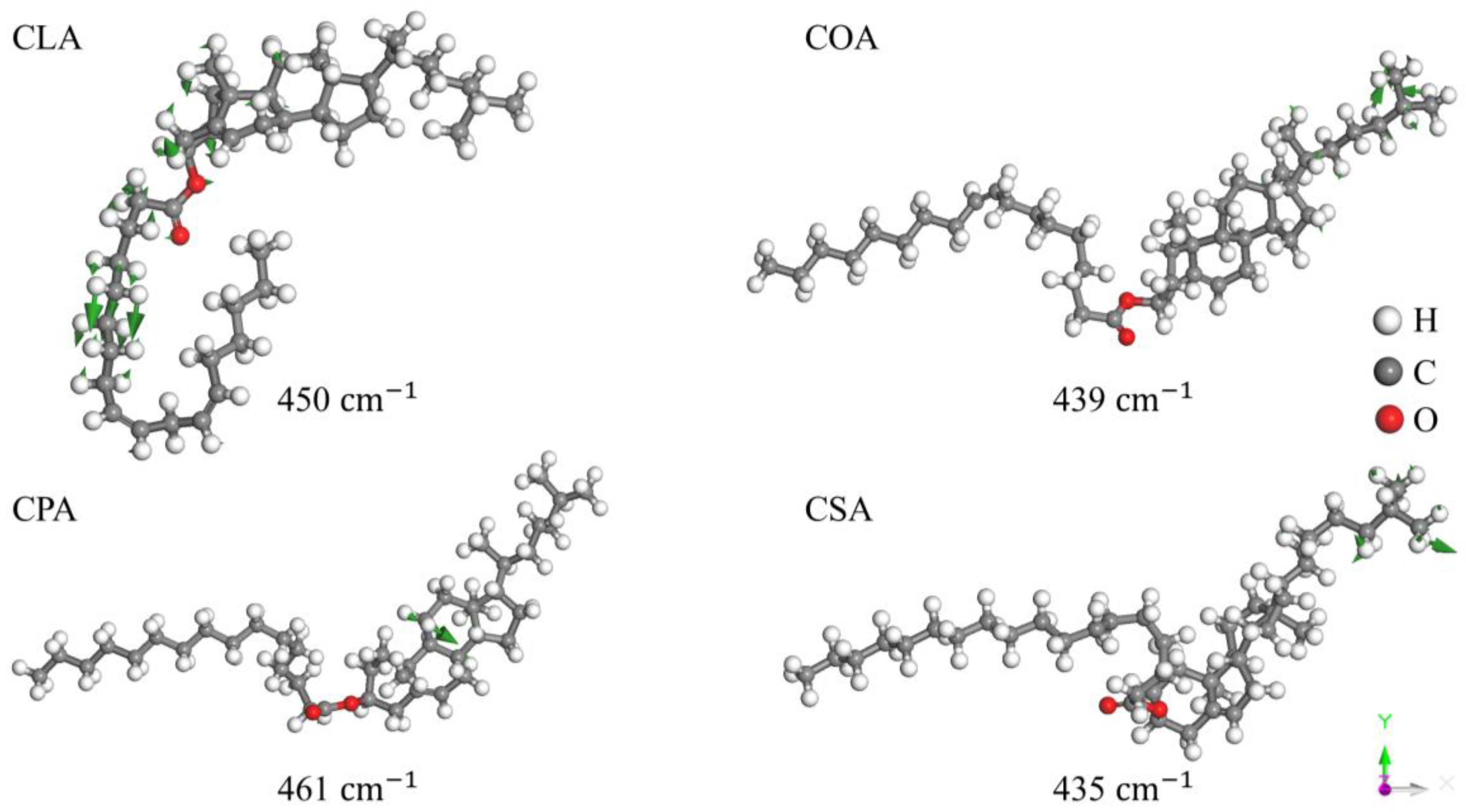

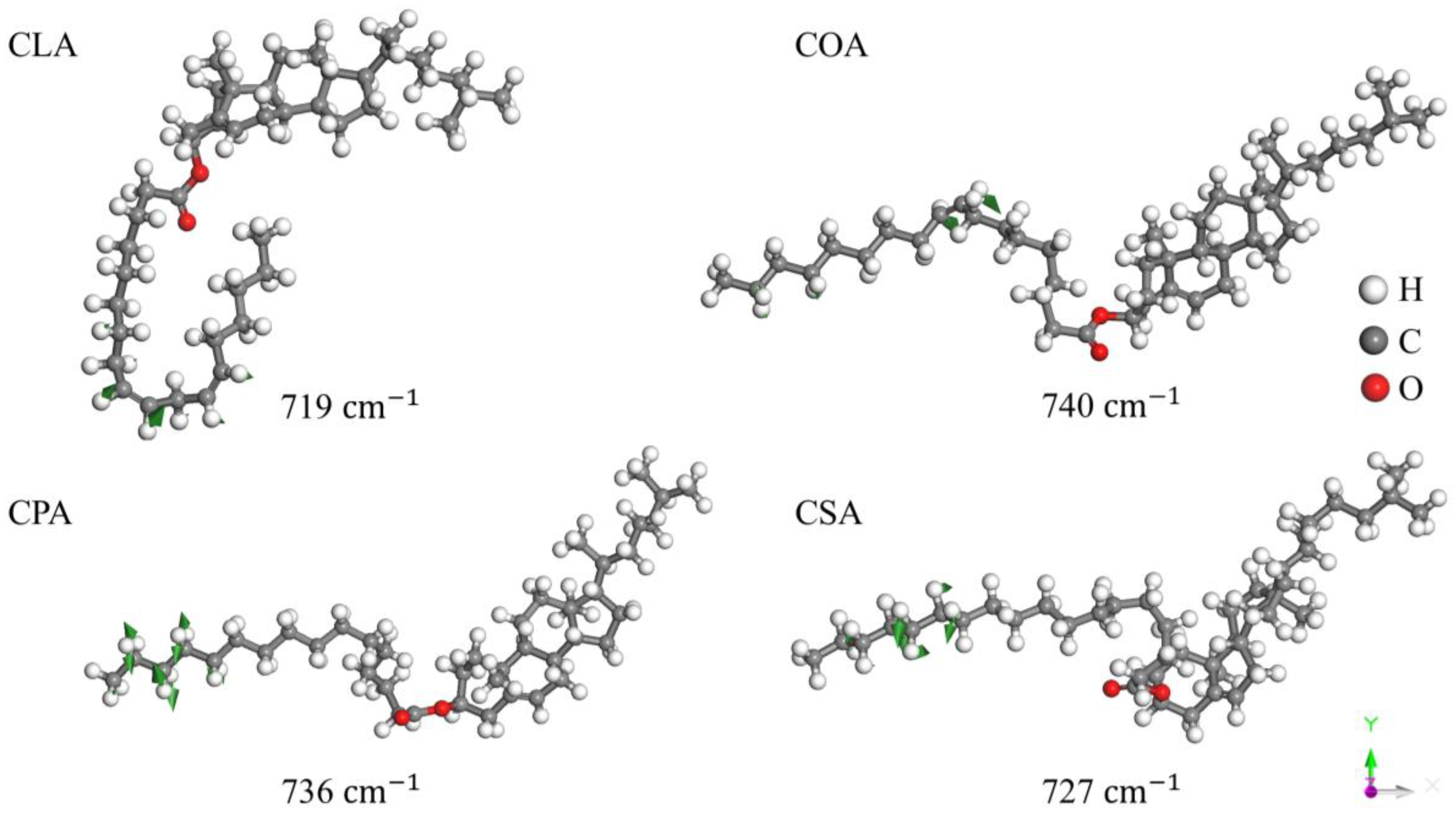

3. Results and Discussion

3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jebari-Benslaiman, S.; Galicia-García, U.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Olaetxea, J. R.; Alloza, I.; Vandenbroeck, K.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Martín, C. Pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hevonoja, T.; Pentikäinen, M. O.; Hyvönen, M. T.; Kovanen, P. T.; Ala-Korpela, M. Structure of low density lipoprotein (LDL) particles: Basis for understanding molecular changes in modified LDL. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2000, 1488, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, G. S.; Atkinson, D.; Small, D. M. Physical properties of cholesteryl esters. Progress in Lipid Research 1984, 23(3), 135–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chistiakov, D. A.; Melnichenko, A. A.; Myasoedova, V. A.; Grechko, A. V.; Orekhov, A. N. Mechanisms of foam cell formation in atherosclerosis. Journal of Molecular Medicine 2017, 95, 1153–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Watanabe, T. Atherosclerosis: Known and unknown. Pathology International 2022, 72, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmysłowski, A.; Szterk, A. Current knowledge on the mechanism of atherosclerosis and pro-atherosclerotic properties of oxysterols. Lipids in Health and Disease 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkegren, J. L. M.; Lusis, A. J. Atherosclerosis: Recent developments. Cell 2022, 185, 1630–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature 2021, 592, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, I.; Totary-Jain, H. Anti-atherosclerotic therapies: Milestones, challenges, and emerging innovations. Molecular Therapy 2022, 30, 3106–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, S. O.; Budoff, M. Effect of statins on atherosclerotic plaque. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine 2019, 29, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, S. E.; Robinson, A. J. B.; Zurke, Y.-X.; Monaco, C. Therapeutic strategies targeting inflammation and immunity in atherosclerosis: how to proceed? Nature Reviews Cardiology 2022, 19, 522–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, P. D.; Panza, G.; Zaleski, A.; Taylor, B. Statin-Associated side Effects. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2016, 67, 2395–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poznyak, A. V.; Bharadwaj, D.; Prasad, G.; Grechko, A. V.; Sazonova, M. A.; Orekhov, A. N. Anti-Inflammatory therapy for atherosclerosis: Focusing on cytokines. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, H.; Cai, L.; Huang, G.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Xia, L.; Ding, X.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Atherosclerosis treatment with nanoagent: potential targets, stimulus signals and drug delivery mechanisms. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Schilperoort, M.; Cao, Y.; Shi, J.; Tabas, I.; Tao, W. Macrophage-targeted nanomedicine for the diagnosis and treatment of atherosclerosis. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2021, 19, 228–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Huang, Q.; Liu, C.; Kwong, C. H. T.; Yue, L.; Wan, J.-B.; Lee, S. M. Y.; Wang, R. Treatment of atherosclerosis by macrophage-biomimetic nanoparticles via targeted pharmacotherapy and sequestration of proinflammatory cytokines. Nature Communications 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, P.; Cui, Z.-Y.; Huang, X.-F.; Zhang, D.-D.; Guo, R.-J.; Han, M. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: signaling pathways and therapeutic intervention. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, R.; Chen, H.; Li, T.; Jiang, H.; Xu, X.; Tang, X.; Wan, M.; Mao, C.; Shi, D. Near-Infrared Light-Driven multifunctional tubular micromotors for treatment of atherosclerosis. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 30930–30940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Chen, L.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zeng, J.; Jiang, W.; Lv, W.; Wan, M.; Mao, C.; Zhou, M. Lipophilic NO-Driven nanomotors as drug balloon coating for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Small 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhou, M.; Tang, X.; Zeng, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Huang, J.; Chen, L.; Wan, M.; Mao, C. Carrier-Free Trehalose-Based nanomotors targeting macrophages in inflammatory plaque for treatment of atherosclerosis. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 3808–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, J. H.; Song, J. W.; Min, J. S.; Kim, H. J.; Kim, R. H.; Ahn, J. W.; Yoo, H.; Park, K.; Kim, J. W. Macrophage-mannose-receptor-targeted photoactivatable agent for in vivo imaging and treatment of atherosclerosis. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2024, 654, 123951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lin, H.; Wang, J.; Rui, J.; Wang, T.; Cai, Z.; Huang, S.; Gao, Y.; Ma, T.; Fan, R.; Dai, R.; Li, Z.; Jia, Y.; Chen, Q.; He, H.; Tan, J.; Zhu, S.; Gu, R.; Dong, Z.; Li, M.; Xie, E.; Fu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Jiang, C.; Sun, J.; Kong, W. Sensing ceramides by CYSLTR2 and P2RY6 to aggravate atherosclerosis. Nature 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Shang, C.; Rong, Y.; Sun, J.; Cheng, Y.; He, B.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Ma, J.; Fu, B.; Ji, X. Review on laser technology in intravascular imaging and Treatment. Aging and Disease 2022, 13, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machowiec, P.; Ręka, G.; Piecewicz-Szczęsna, H. Usage of excimer laser in coronary and peripheral artery stenosis – analysis of its safety aspect. Journal of Pre-Clinical and Clinical Research 2020, 14, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamatsu, H.; Torii, S.; Aihara, K.; Nakazawa, K.; Nakamura, N.; Noda, S.; Sekino, S.; Yoshimachi, F.; Nakazawa, G.; Ikari, Y. Histological evaluation of vascular changes after excimer laser angioplasty for neointimal formation after bare-metal stent implantation in rabbit iliac arteries. Cardiovascular Intervention and Therapeutics 2023, 38, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delley, B. An All-Electron Numerical Method for Solving the Local Density Functional for Polyatomic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 92, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J. P.; Burke, K.; Wang, Y. Generalized Gradient Approximation for the Exchange-Correlation Hole of a Many-Electron System. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 1996, 54, 16533–16539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

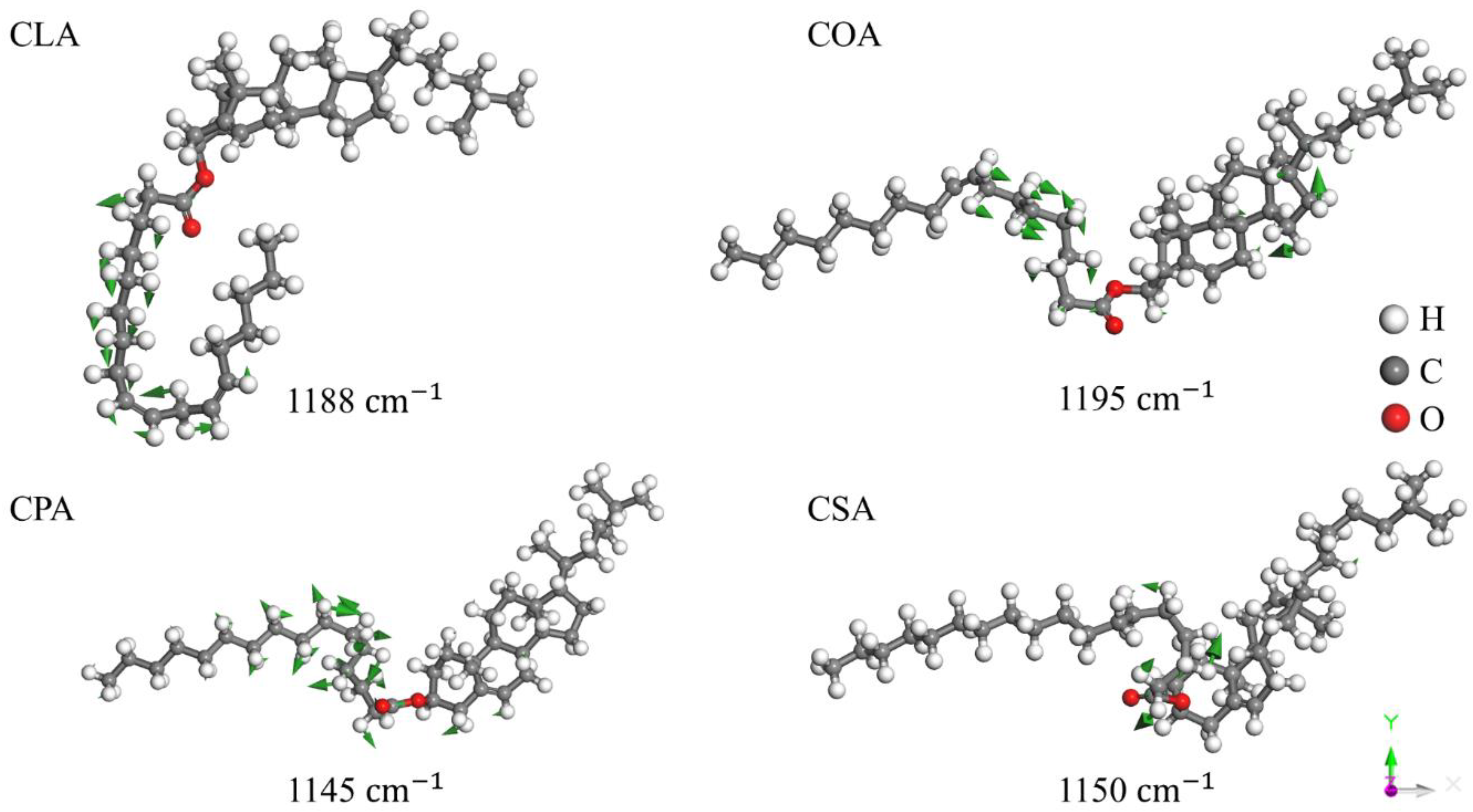

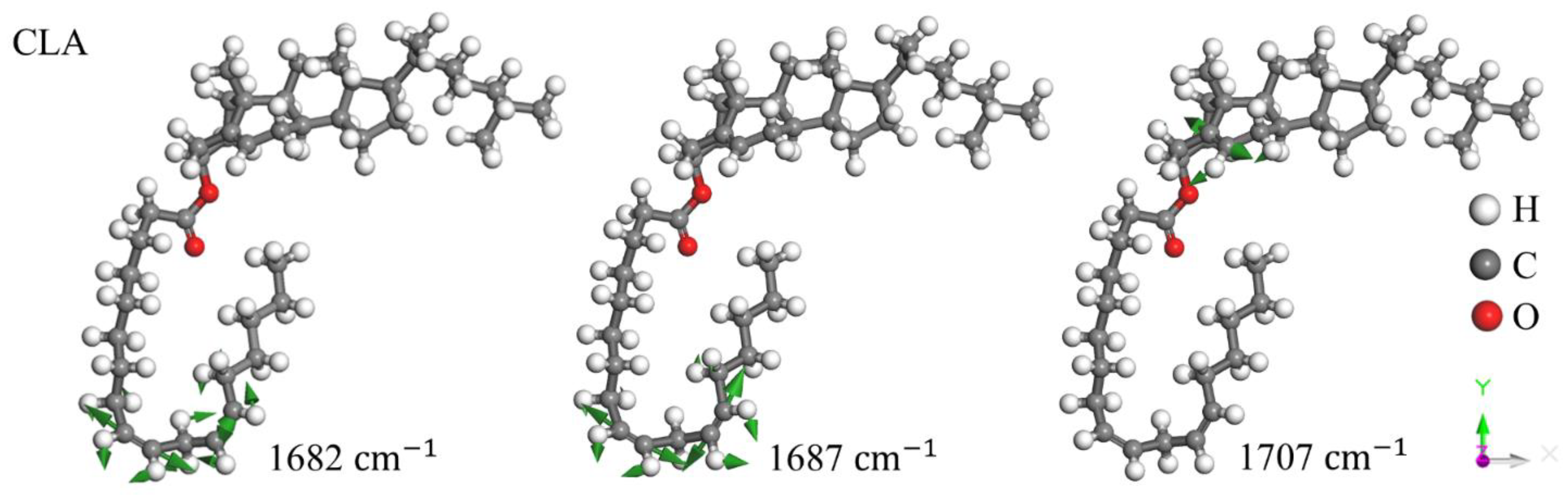

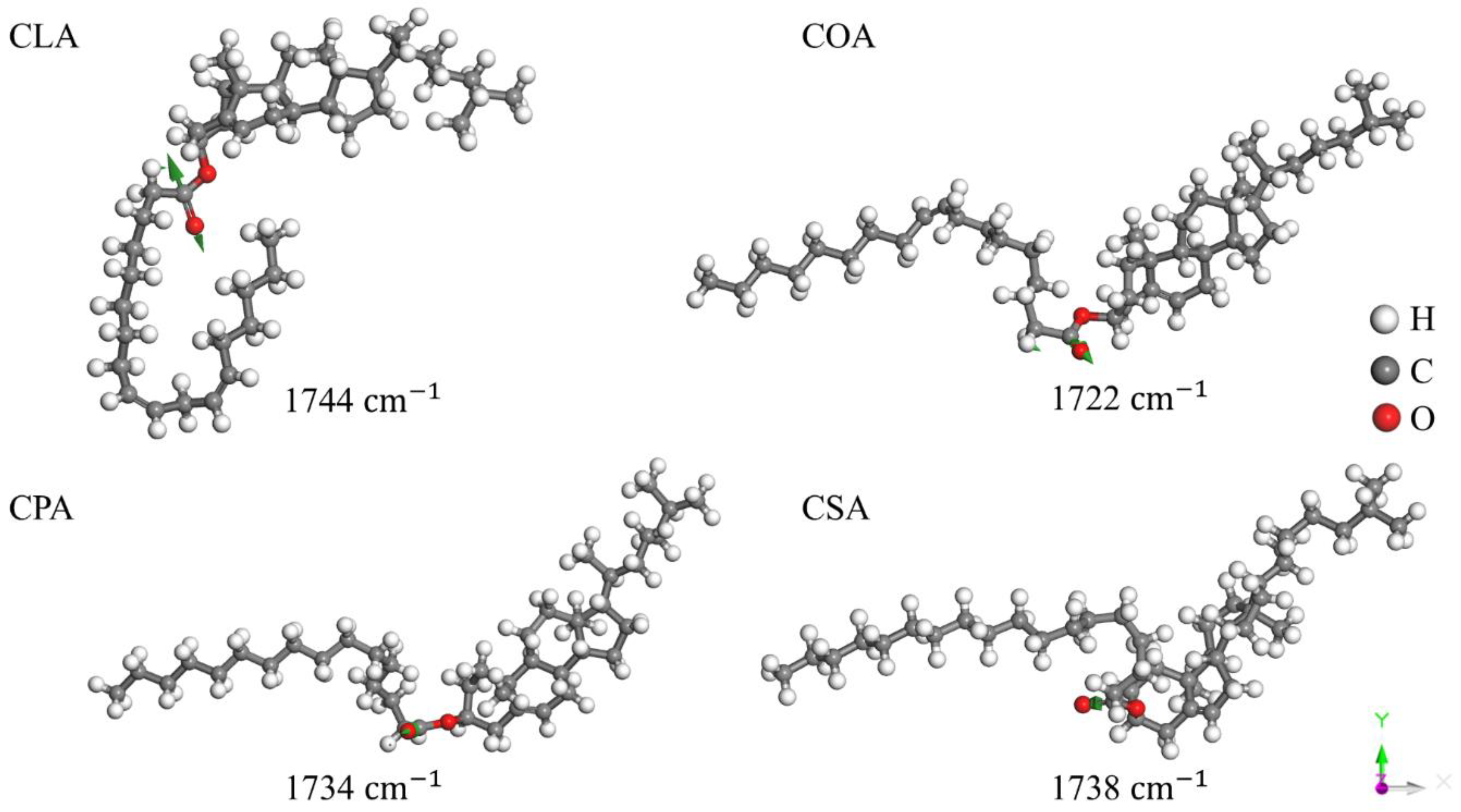

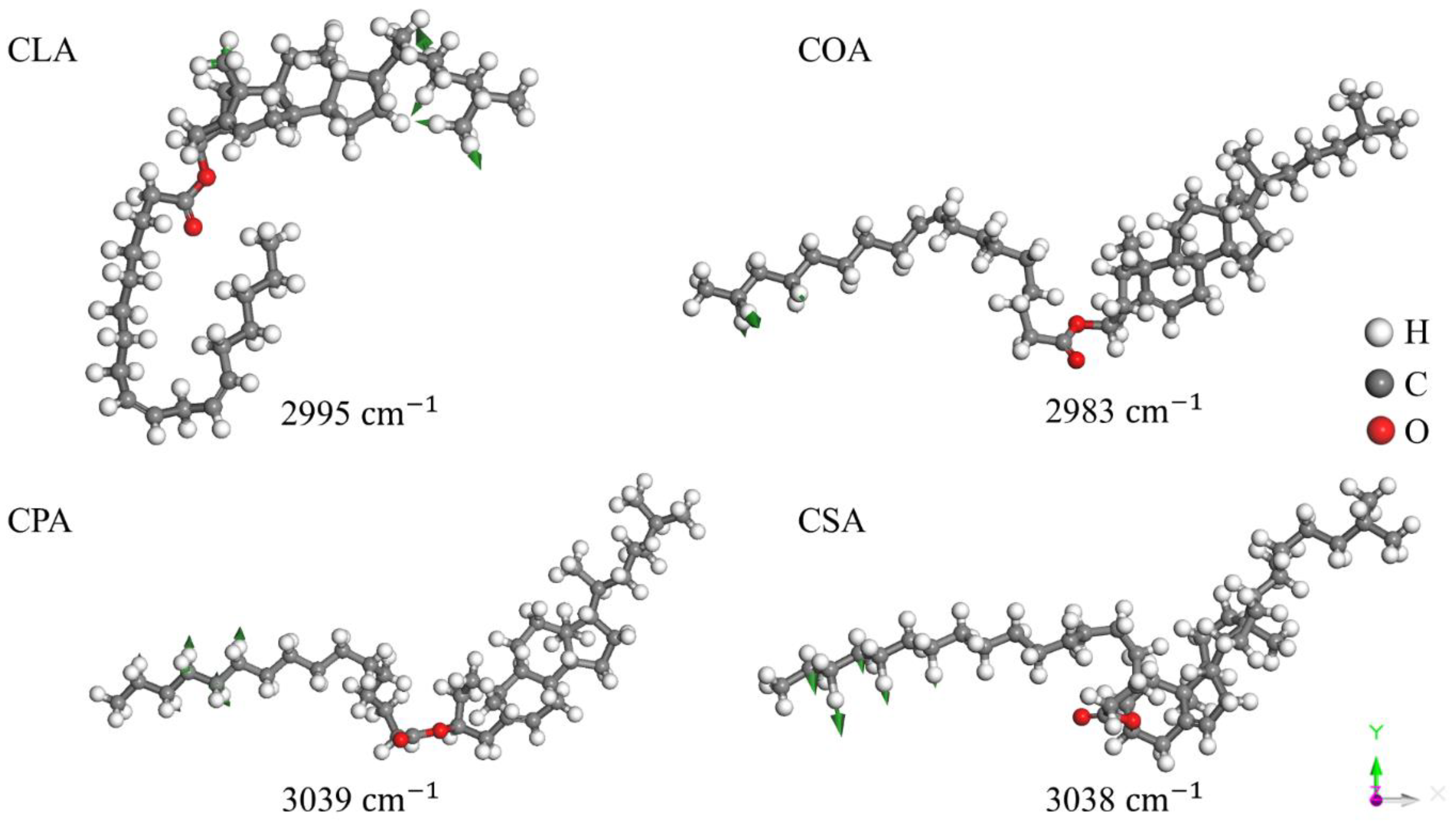

- Czamara, K.; Majzner, K.; Pacia, M. Z.; Kochan, K.; Kaczor, A.; Baranska, M. Raman spectroscopy of lipids: a review. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 2014, 46, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, C.; Neudert, L.; Simat, T.; Salzer, R. Near infrared Raman spectra of human brain lipids. Spectrochimica Acta Part a Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2004, 61, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S. R.; Prasad, J. S.; Venkataraman, S. Vibrational spectra of sterol and non-sterol cholesterogens. Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals 1987, 146, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, T. P.; Mateuszuk, L.; Chlopicki, S.; Malek, K.; Baranska, M. Imaging of lipids in atherosclerotic lesion in aorta from ApoE/LDLR−/− mice by FT-IR spectroscopy and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis. The Analyst 2011, 136, 5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B. C. The C=O Bond, Part VI: Esters and the Rule of Three. Spectroscopy Online. /: https, 20 December.

- Bresson, S.; Marssi, M. E.; Khelifa, B. First investigations of two important components of low density lipoproteins by Raman spectroscopy: the cholesteryl linoleate and arachidonate. Vibrational Spectroscopy 2004, 34, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nara, M.; Okazaki, M.; Kagi, H. Infrared study of human serum very-low-density and low-density lipoproteins. Implication of esterified lipid C=O stretching bands for characterizing lipoproteins. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 2002, 117, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambharose, S.; Kalhapure, R. S.; Jadhav, M.; Govender, T. Exploring unsaturated fatty acid cholesteryl esters as transdermal permeation enhancers. Drug Delivery and Translational Research 2017, 7, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labarrere, J. A.; Chipault, J. R.; Lundberg, W. O. Cholesteryl esters of Long-Chain fatty acids. infrared spectra and separation by paper chromatography. Analytical Chemistry 1958, 30, 1466–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wen, Z.; Zhang, P. Theoretical investigation of a new physical method for fat removal by melting: A case study of caprate triglyceride. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 11354–11358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).