Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Background

- Welfare Economics: The theoretical basis for cost-benefit analysis rests on the principles of welfare economics, particularly the Kaldor-Hicks compensation criterion, which states that a project is desirable if those who gain could potentially compensate those who lose, with a net positive outcome (Just et al., 2004). We extend this to include intergenerational equity considerations especially relevant to environmental projects.

- Environmental Valuation Theory: The economic valuation of environmental goods and services draws upon theories of total economic value (TEV), which encompasses use values (direct, indirect, and option values) and non-use values (existence and bequest values) (Pearce et al., 2006).

- Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA): When multiple, potentially conflicting objectives exist, MCDA provides theoretical frameworks for structuring complex problems, incorporating diverse stakeholder perspectives, and making trade-offs explicit (Belton & Stewart, 2002).

1.2. Research Gap and Contribution

- Integrate economic, environmental, and social dimensions in a coherent mathematical structure

- Address temporal dynamics across all dimensions

- Account for uncertainty and risk in a unified way

- Provide clear methodological guidance for non-market valuation within CBA

- This paper contributes to the literature by proposing a theoretical framework that addresses these gaps, thereby enhancing the applicability of CBA to complex environmental projects.

2. Methodology

-

Net Present Value (NPV) The NPV of a project is defined as the present value of net benefits:where:

- is the benefit at time ,

- is the cost at time ,

- is the discount rate, and

- is the time horizon.

-

Internal Rate of Return (IRR)The IRR is the discount rate that satisfies:

-

Benefit-Cost Ratio (BCR)The BCR is given by:

2.1. Environmental Dimension

2.2. Carbon Impact Function

- is the baseline emissions, and

- is the emissions with the project at time .

- 2.

-

Biodiversity Conservation FunctionBiodiversity value is expressed as:where:

- is the species richness index,

- is the habitat quality index,

- is the genetic diversity index, and

- are weighting parameters reflecting ecological significance.

- 3.

-

Environmental Quality FunctionA composite quality indicator is given by:where:

- is the quality index for environmental component at time ,

- is the weight for component , and

- is the number of environmental components.

2.3. Social Dimension

-

Social Welfare FunctionThe basic social welfare is:where:

- is social indicator at time ,

- is the weight for indicator , and

- is the number of social indicators.

-

Employment FunctionEmployment benefits are modeled as:where:

- is the number of direct jobs created at time ,

where:- is the number of direct jobs created at time ,

- is the number of indirect jobs, and

- reflects the relative economic weight of indirect jobs.

-

Health Impact FunctionHealth outcomes are expressed as:where:

- is health indicator at time ,

- is the corresponding weight, and

- is the number of health indicators.

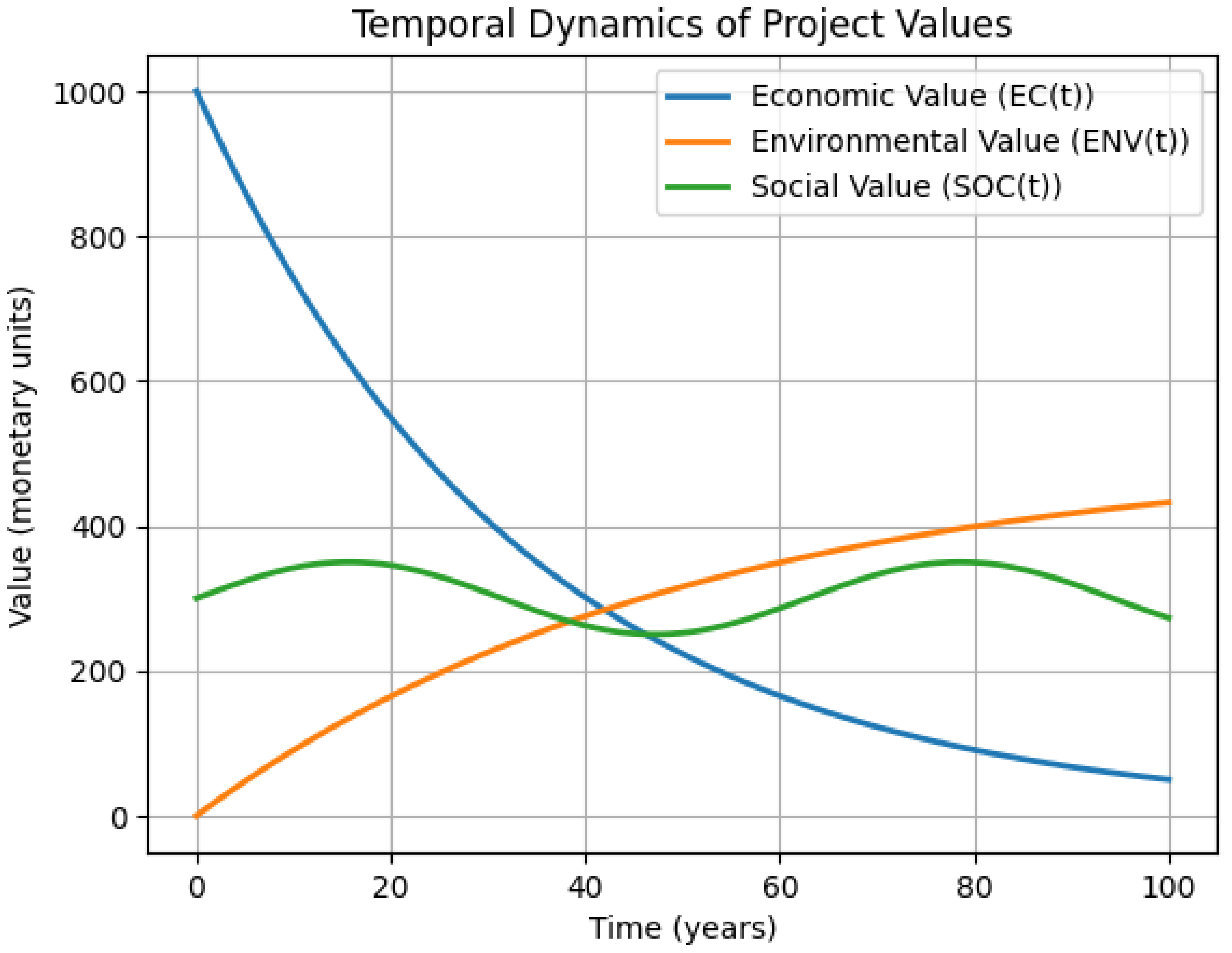

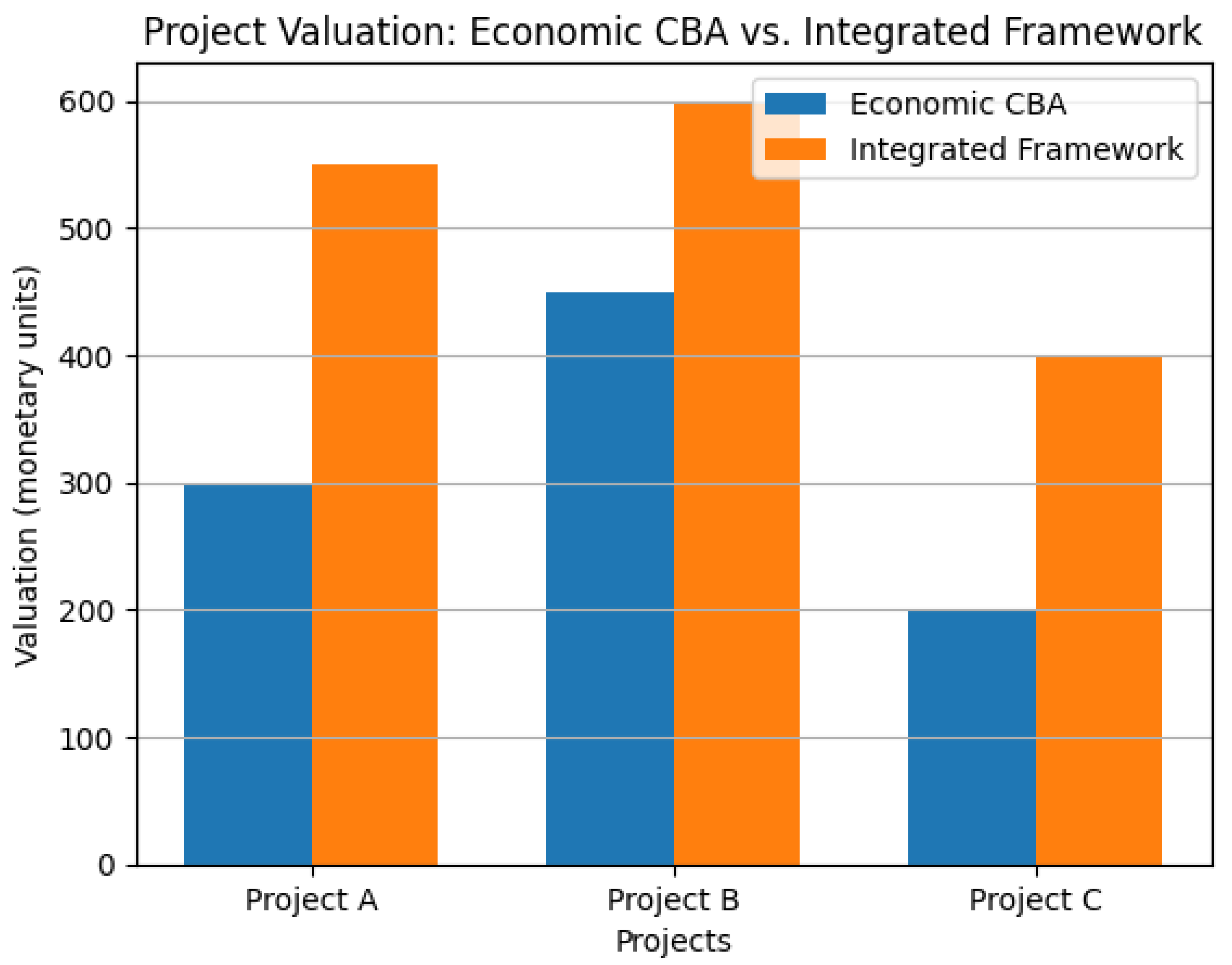

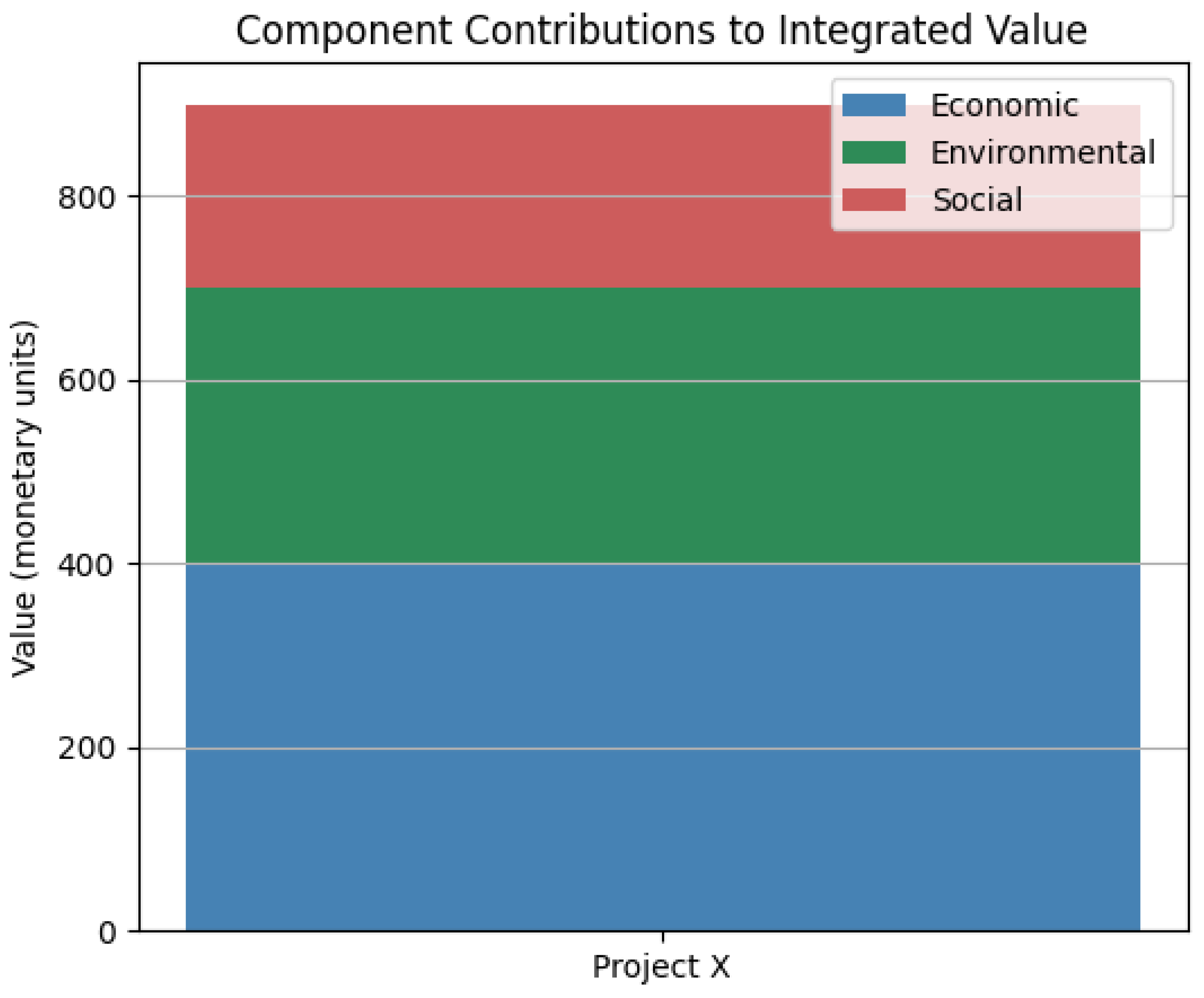

2.4. Integrated Value Function

- and are conversion factors for environmental and social values, respectively,

- is the discounting term using the social discount rate ,

- is the project’s time horizon.

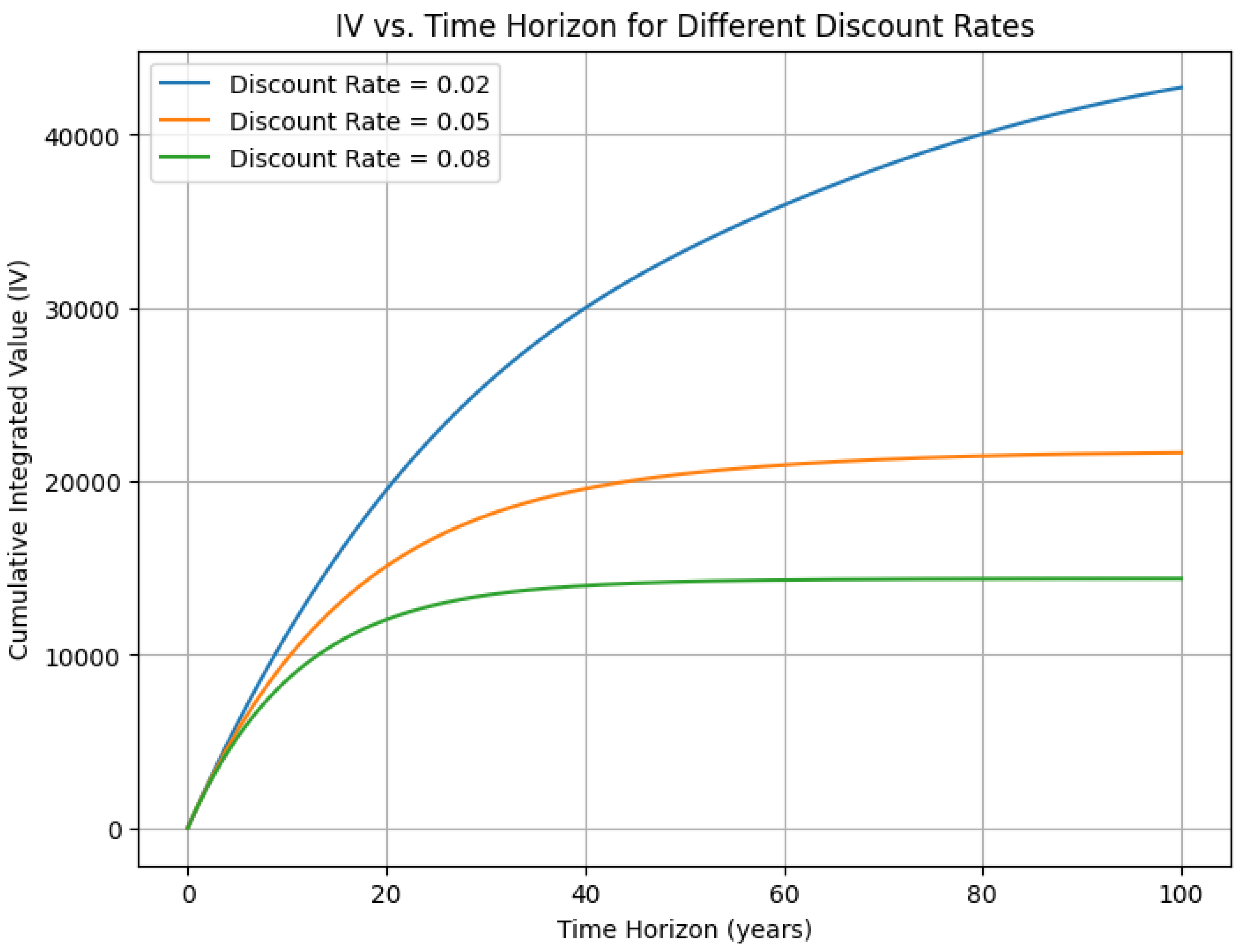

2.5. Addressing Temporal Dynamics

- is the initial discount rate,

- is a decline parameter that accounts for increased uncertainty over time.

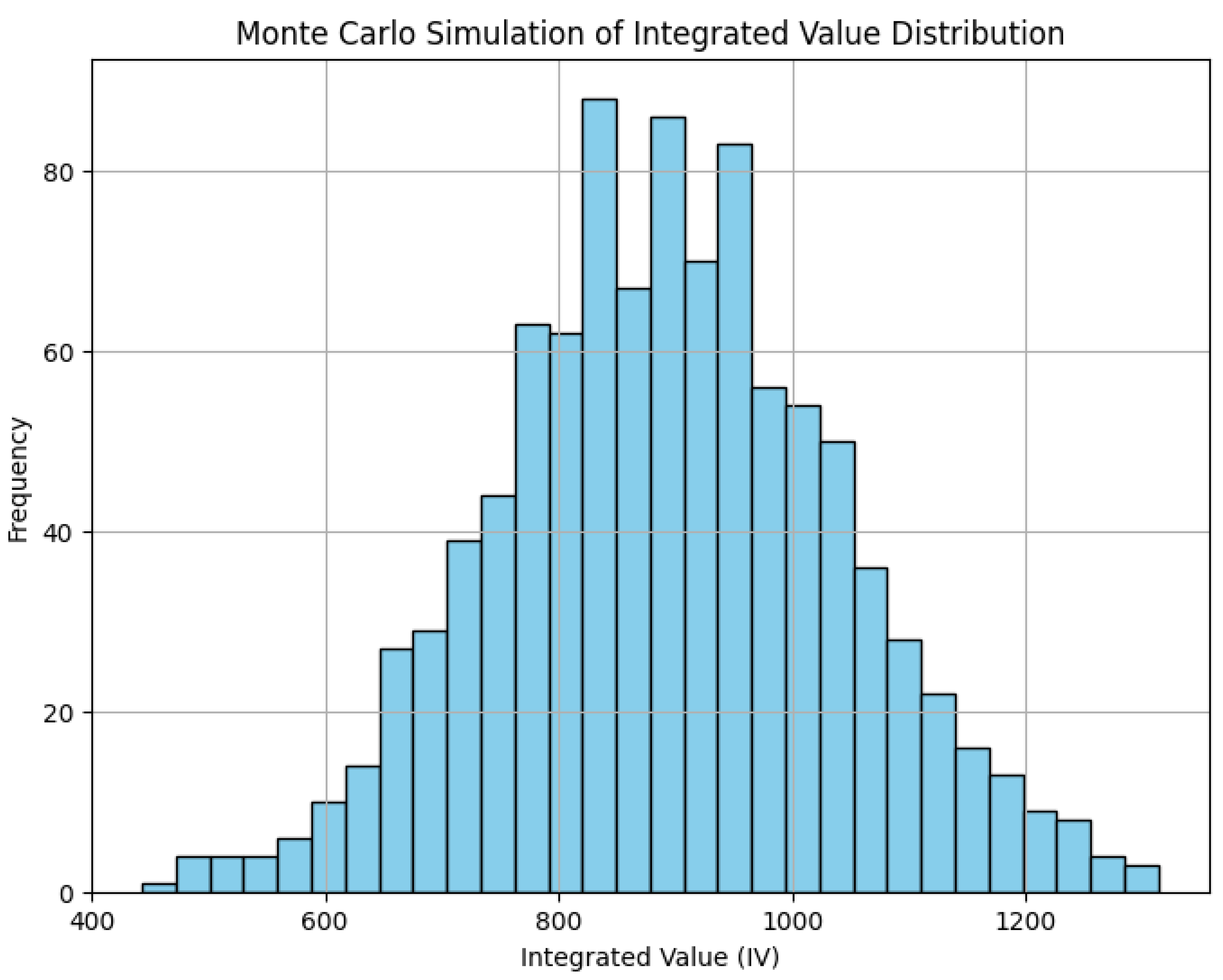

2.6. Incorporating Uncertainty and Risk

-

Expected Integrated ValueThe expected value over all states in the uncertainty set is:For computational purposes, this may be discretized as:

-

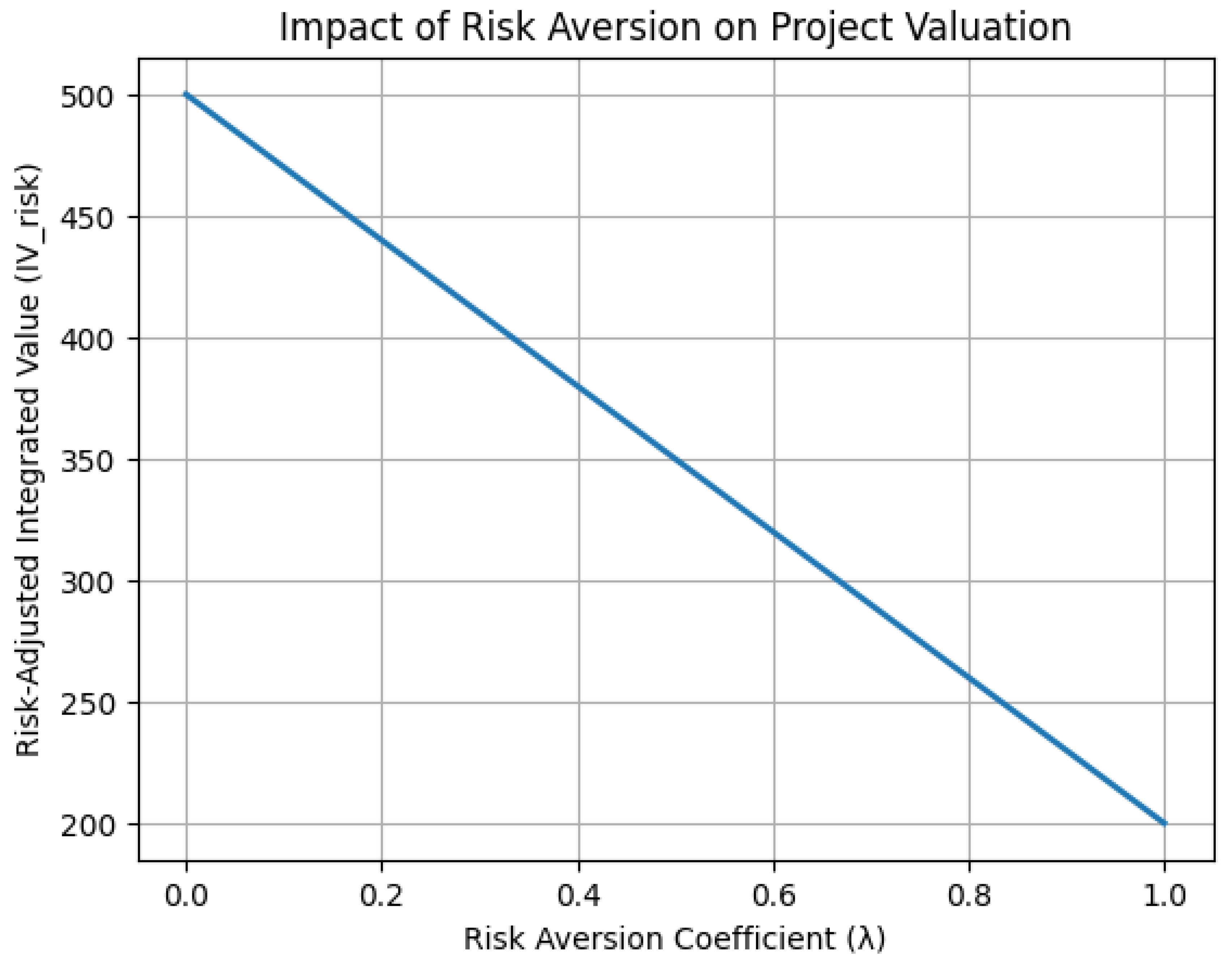

Risk AdjustmentTo incorporate risk aversion, a risk-adjusted integrated value is defined as:where the variance is:and is the risk aversion coefficient.

-

Robust Decision MakingFor cases of deep uncertainty (where probabilities are not well defined), the maximin criterion can be used:where represents the set of decision alternatives and a set of plausible future states.

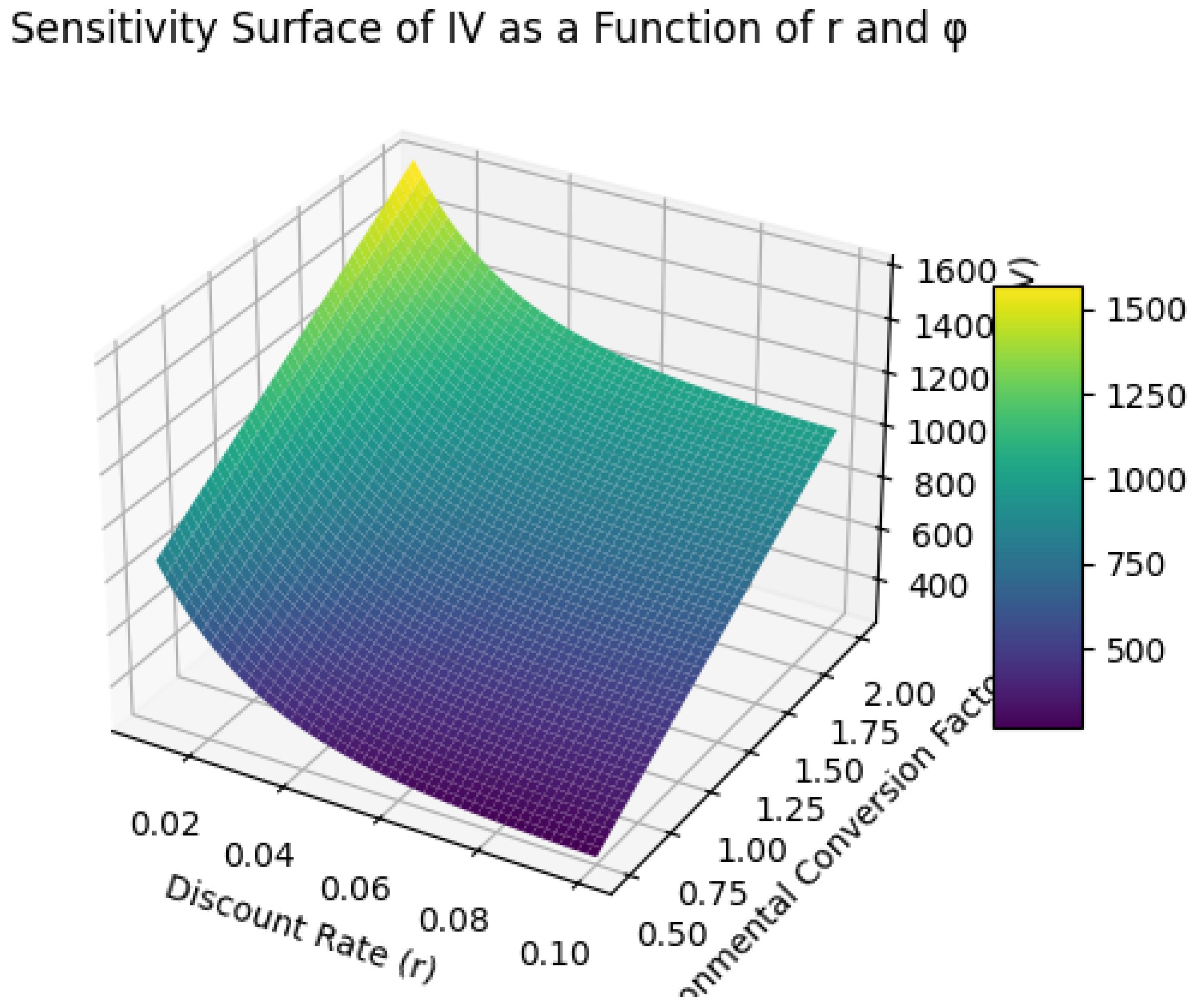

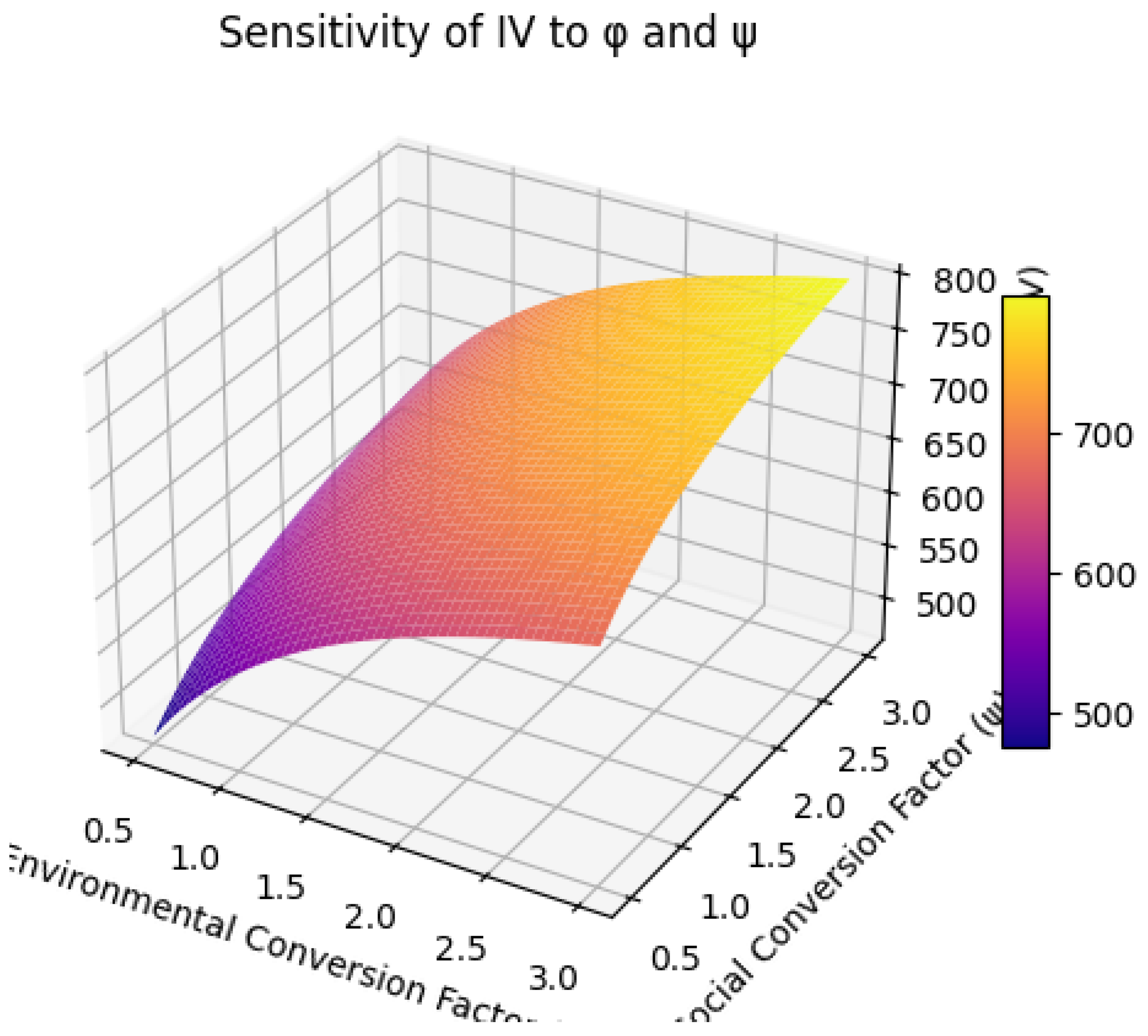

2.7. Sensitivity Analysis

- Sensitivity with respect to :

-

Sensitivity with respect toThe ratio of these sensitivities,

2.8. Derivation of the Integrated Value Function

- from (4)),

- from (8a), and

- from (12a).

2.9. Optimal Decision Rule

2.10. Time-Declining Discount Rate Derivation

2.11. Risk-Adjusted Integrated Value

- is the risk aversion coefficient,

- is the standard deviation of outcomes at time .

2.12. Sensitivity Analysis of Conversion Factors

- Summary

3. Results

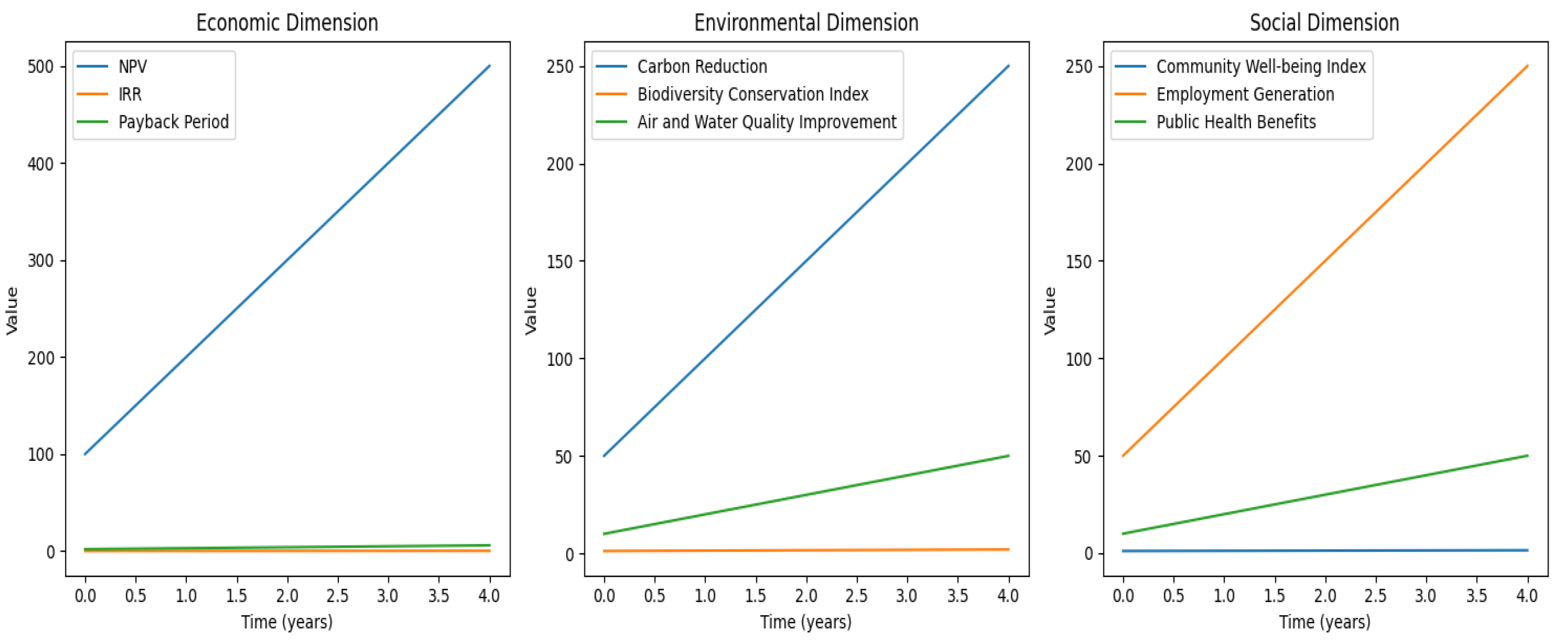

- Economic Dimension Graph: This graph shows how the financial aspects of the project change over time. The Net Present Value (NPV) represents the difference between the project’s benefits and costs, adjusted for the time value of money. A positive NPV indicates that the project is profitable. The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is the discount rate at which the NPV is zero, providing a measure of the project’s profitability. The Payback Period is the time it takes to recover the initial investment. A shorter payback period is generally preferred.

- Environmental Dimension Graph: This graph illustrates the project’s environmental impacts over time. Carbon Reduction shows the decrease in greenhouse gas emissions due to the project. The Biodiversity Conservation Index measures the project’s contribution to preserving local ecosystems and species (Montgomery, 2024a). The Air and Water Quality Improvement index reflects enhancements in air and water quality resulting from the project.

- Social Dimension Graph: This graph demonstrates the project’s social impacts over time. The Community Well-being Index measures improvements in the quality of life for local residents. Employment Generation shows the number of jobs created or supported by the project. Public Health Benefits reflect health improvements resulting from the project, such as reduced respiratory diseases.

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths of the Model

4.2. Limitations of the Model

4.3. Potential Applications

4.4. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusion

6. Attachments

References

- Arrow, K. J., Cropper, M. L., Gollier, C., Groom, B., Heal, G. M., Newell, R. G., Nordhaus, W. D., Pindyck, R. S., Pizer, W. A., Portney, P. R., Sterner, T., Tol, R. S. J., & Weitzman, M. L. (2013). Determining benefits and costs for future generations. Science, 341(6144), 349-350. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, G., & Mourato, S. (2008). Environmental cost-benefit analysis. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 33, 317-344.

- Barbier, E. B. (2011). Capitalizing on Nature: Ecosystems as Natural Assets. Cambridge University Press.

- Bateman, I. J., Mace, G. M., Fezzi, C., Atkinson, G., & Turner, K. (2011). Economic analysis for ecosystem service assessments. Environmental and Resource Economics, 48(2), 177-218. [CrossRef]

- Belton, V., & Stewart, T. J. (2002). Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: An Integrated Approach. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Boardman, A., Greenberg, D., Vining, A., & Weimer, D. (2017). Cost-Benefit Analysis: Concepts and Practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Carson, R. T. (2012). Contingent valuation: A practical alternative when prices aren’t available. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(4), 27-42. [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R., de Groot, R., Sutton, P., van der Ploeg, S., Anderson, S. J., Kubiszewski, I., Farber, S., & Turner, R. K. (2014). Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change, 26, 152-158. [CrossRef]

- Daly, H. E. (2007). Ecological Economics and Sustainable Development: Selected Essays of Herman Daly. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Dasgupta, P. (2008). Discounting climate change. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 37(2-3), 141-169.

- de Groot, R. S., Alkemade, R., Braat, L., Hein, L., & Willemen, L. (2010). Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecological Complexity, 7(3), 260-272. [CrossRef]

- Farrow, S. (2004). Using risk assessment, benefit-cost analysis, and real options to implement a precautionary principle. Risk Analysis, 24(3), 727-735. [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, T. (2003). Critical Political Ecology: The Politics of Environmental Science. Routledge.

- Gollier, C. (2002). Discounting an uncertain future. Journal of Public Economics, 85(2), 149-166.

- Gollier, C., & Weitzman, M. L. (2010). How should the distant future be discounted when discount rates are uncertain? Economics Letters, 107(3), 350-353.

- Goulder, L. H., & Williams, R. C. (2012). The choice of discount rate for climate change policy evaluation. Climate Change Economics, 3(04), 1250024. [CrossRef]

- Gowdy, J., Howarth, R. B., & Tisdell, C. (2010). Discounting, ethics, and options for maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem integrity. In P. Kumar (Ed.), The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Ecological and Economic Foundations (pp. 257-283). Earthscan.

- Hanley, N., & Barbier, E. B. (2009). Pricing Nature: Cost-Benefit Analysis and Environmental Policy. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Heal, G., & Millner, A. (2014). Reflections: Uncertainty and decision making in climate change economics. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 8(1), 120-137.

- Hicks, J. R. (1939). The foundations of welfare economics. The Economic Journal, 49(196), 696-712.

- Howarth, R. B., & Norgaard, R. B. (2013). Intergenerational transfers and the social discount rate. Environmental and Resource Economics, 3(4), 337-358. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. (2022). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Cambridge University Press.

- Just, R. E., Hueth, D. L., & Schmitz, A. (2004). The Welfare Economics of Public Policy: A Practical Approach to Project and Policy Evaluation. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Kaldor, N. (1939). Welfare propositions of economics and interpersonal comparisons of utility. The Economic Journal, 49(195), 549-552. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery R. M. (2025). Investigating Coexistence and Extinction in a Four-Species Trophic System Using Random Matrix Theory. Journal of Medicine and Healthcare. SRC/JMHC-375. [CrossRef]

- Mongomery, R. M. (2024). Topological Dynamics in Ecological Biomes and Toroidal Structures: Mathematical Models.

- Montgomery, R. M. (2024)a. Techniques for Outlier Detection: A Comprehensive View. Journal of Biomedical and Engineering Research.2 (2), 1-10.

- of Stability, Bifurcation, and Structural Failure. J Gene Engg Bio Res, 6(2), 01-09.

- Nordhaus, W. D. (2007). A review of the Stern Review on the economics of climate change. Journal of Economic Literature, 45(3), 686-702. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J., Holland, A., & Light, A. (2008). Environmental Values. Routledge.

- Pearce, D., Atkinson, G., & Mourato, S. (2006). Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Environment: Recent Developments. OECD Publishing.

- Polasky, S., Carpenter, S. R., Folke, C., & Keeler, B. (2011). Decision-making under great uncertainty: Environmental management in an era of global change. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 26(8), 398-404.

- Spash, C. L. (2008). How much is that ecosystem in the window? The one with the bio-diverse trail. Environmental Values, 17(2), 259-284. [CrossRef]

- Stern, N. (2007). The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. Cambridge University Press.

- Sunstein, C. R. (2018). The Cost-Benefit Revolution. MIT Press.

- Turner, R. K., Pearce, D., & Bateman, I. (1994). Environmental Economics: An Elementary Introduction. Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Vatn, A. (2009). An institutional analysis of methods for environmental appraisal. Ecological Economics, 68(8-9), 2207-2215. [CrossRef]

- Weitzman, M. L. (2001). Gamma discounting. American Economic Review, 91(1), 260-271.

- Weyant, J. (2017). Some contributions of integrated assessment models of global climate change. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 11(1), 115-137. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M. A., & Howarth, R. B. (2002). Discourse-based valuation of ecosystem services: Establishing fair outcomes through group deliberation. Ecological Economics, 41(3), 431-443. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).