Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Article

- Incoming proteins must only bind to the fibril tip to accommodate its specific cross-sectional shape.

- Incoming proteins must have the same sequence as the protein in the fibril tip to enable parallel, in-register stacking.

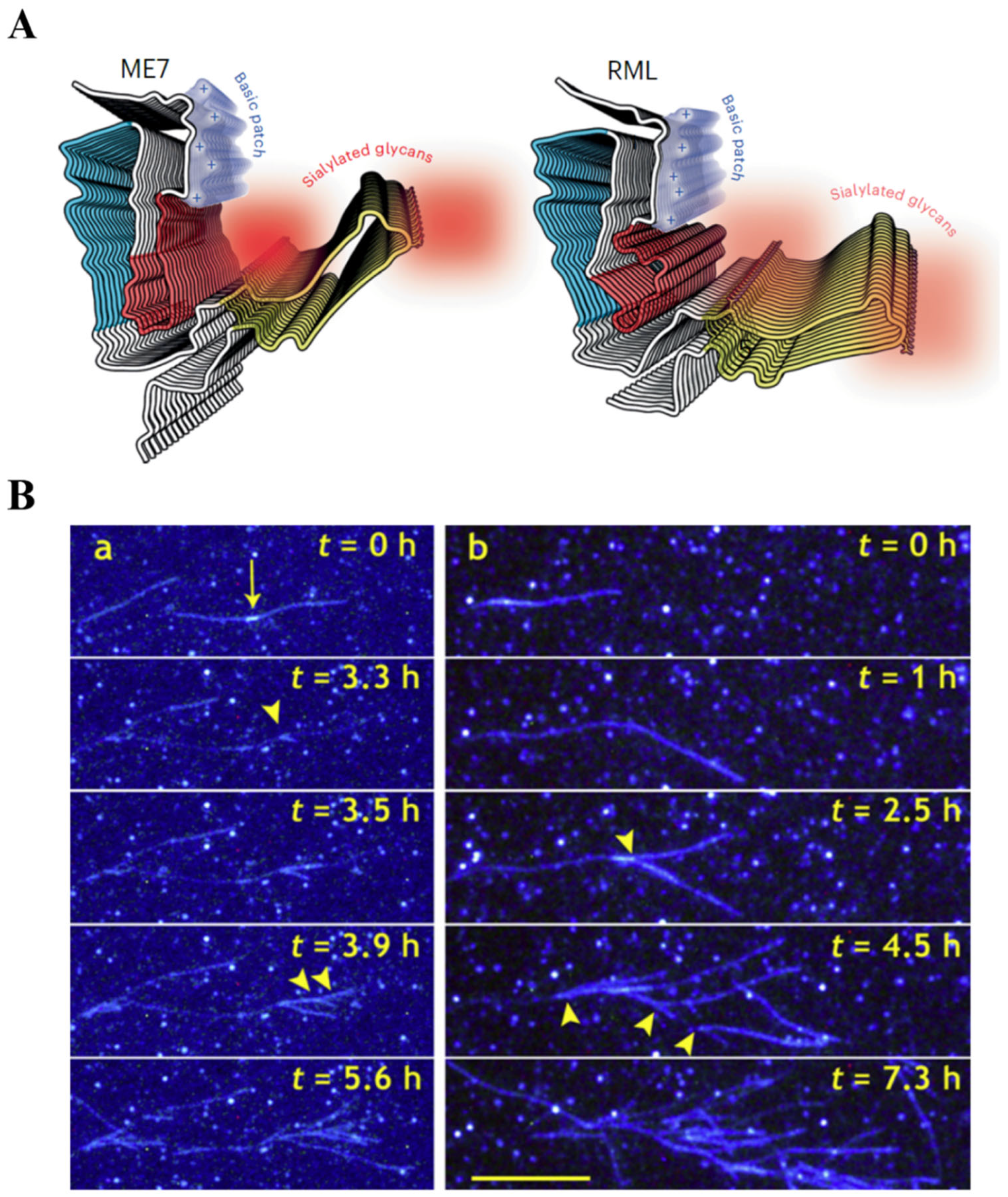

- Amyloid growth cannot maintain elongation even for one generation of fibrils because the process is immediately taken over by branching (Figure 1B), where new fibrils grow as branches on the lateral surface of the parent fibril, a process termed secondary nucleation [4,5]. The lateral surface of the fibril bears no resemblance to its cross-sectional shape (the conformational information) and cannot engage in a parallel, in-register protein binding.

- Seeds of one protein can induce amyloid aggregation of another protein without the sequence homology needed for parallel-in register elongation, a process termed cross-seeding [6]. In this case, heterologous seeds act mainly as catalytic surfaces that do not relay any conformational information [7].

- 3.

- There is no thermodynamic incentive for a protein molecule to exit its stable native conformation to mold itself on a fibril’s tip.

- 4.

- There is no mechanism by which seeds can go around in solution “fishing” for similar protein molecules to mold it into their shape.

- 5.

- No machinery has ever been found that could restrict amyloid growth to tip elongation and prevent branching to preserve the cross-sectional template information.

- 6.

- While parallel in-register is the most common β-sheet stacking architecture of amyloids, amyloids with anti-parallel and out-of-register architecture have been experimentally found [8].

- 7.

- 8.

- In a process termed homogenous nucleation, amyloids form spontaneously at high protein concentrations without any template [11].

- 9.

- Amyloid formation is strictly dependent on protein concentration and does not take place under dilute conditions no matter how many seeds or other catalysts are present.

- 10.

Disclosures relevant to this manuscript

Disclosures

References

- Condello C, Westaway D, Prusiner SB. Expanding the Prion Paradigm to Include Alzheimer and Parkinson Diseases. JAMA Neurol. 2024;81(10):1023-1024. [CrossRef]

- Manka SW, Wenborn A, Betts J, et al. A structural basis for prion strain diversity. Nat Chem Biol. 2022;(June). [CrossRef]

- Wickner RB, Shewmaker F, Kryndushkin D, Edskes HK. Protein inheritance (prions) based on parallel in-register β-sheet amyloid structures. BioEssays. 2008;30(10):955-964. [CrossRef]

- Törnquist M, Michaels TCTT, Sanagavarapu K, et al. Secondary nucleation in amyloid formation. Chemical Communications. 2018;54(63):8667-8684. [CrossRef]

- Andersen CB, Yagi H, Manno M, et al. Branching in amyloid fibril growth. Biophys J. 2009;96(4):1529-1536. [CrossRef]

- Subedi S, Sasidharan S, Nag N, Saudagar P, Tripathi T. Amyloid Cross-Seeding: Mechanism, Implication, and Inhibition. Published online 2022.

- Koloteva-Levine N, Aubrey LD, Marchante R, et al. Amyloid particles facilitate surface-catalyzed cross-seeding by acting as promiscuous nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(36):1-12. [CrossRef]

- Tycko R, Wickner RB. Molecular structures of amyloid and prion fibrils: Consensus versus controversy. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46(7):1487-1496. [CrossRef]

- Jean L, Lee CF, Vaux DJ. Enrichment of amyloidogenesis at an air-water interface. Biophys J. 2012;102(5):1154-1162. [CrossRef]

- Ezzat K, Sturchio A, Espay AJ. Proteins Do Not Replicate, They Precipitate: Phase Transition and Loss of Function Toxicity in Amyloid Pathologies. Biology (Basel). 2022;11(4):535. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava AK, Pittman JM, Zerweck J, et al. β-Amyloid Aggregation and Heterogeneous Nucleation. Protein Science. Published online 2019:pro.3674. [CrossRef]

- Peduzzo A, Linse S, Buell A. The Properties of α-Synuclein Secondary Nuclei are Dominated by the Solution Conditions Rather than the Seed Fibril Strain. 2019;(2):1-22. [CrossRef]

- Lövestam S, Schweighauser M, Matsubara T, et al. Seeded assembly in vitro does not replicate the structures of α-synuclein filaments from multiple system atrophy. FEBS Open Bio. 2021;11(4):999-1013. [CrossRef]

- Frey L, Ghosh D, Qureshi BM, et al. On the pH-dependence of α-synuclein amyloid polymorphism and the role of secondary nucleation in seed-based amyloid propagation. Elife. 2024;12. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).