Submitted:

03 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Searching Criteria

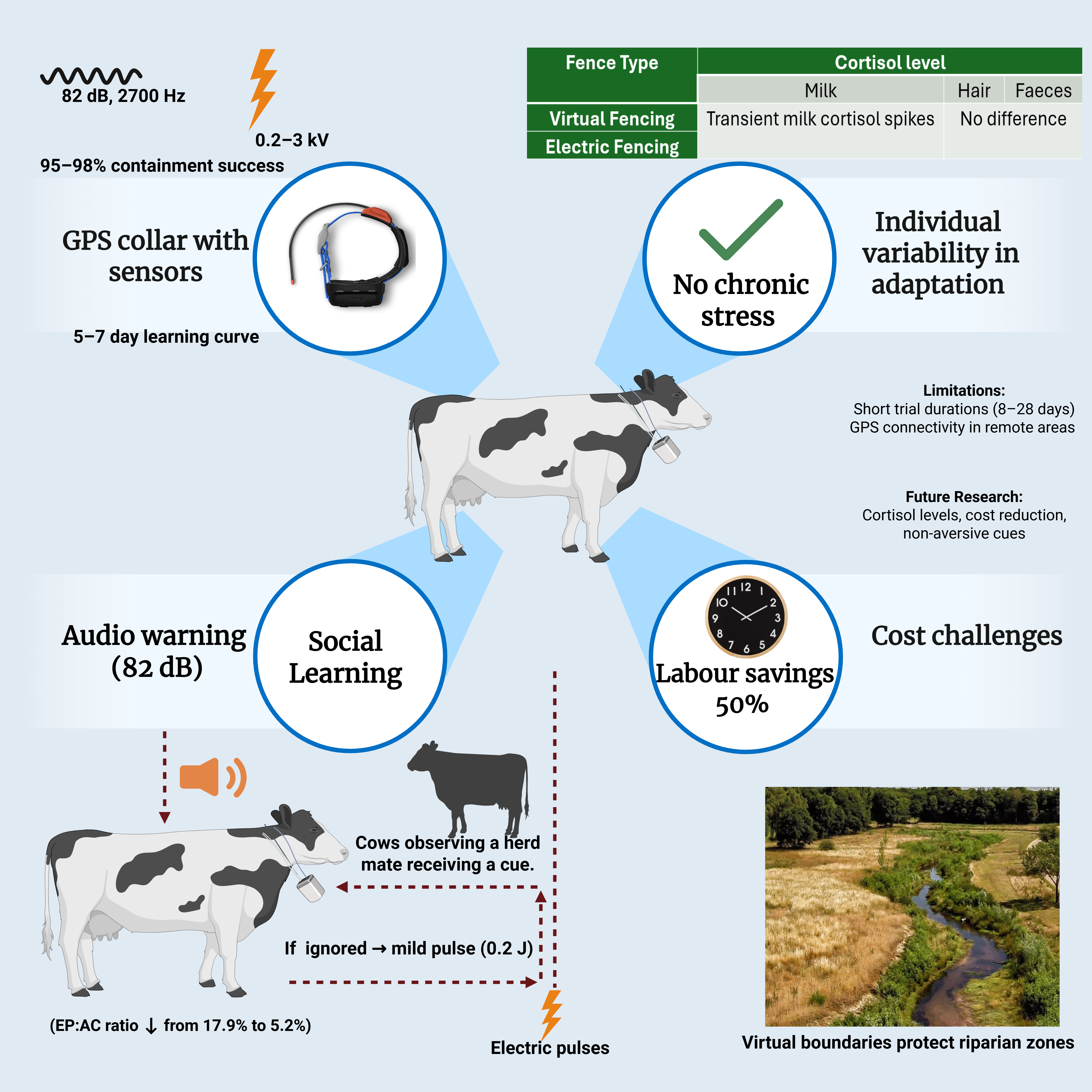

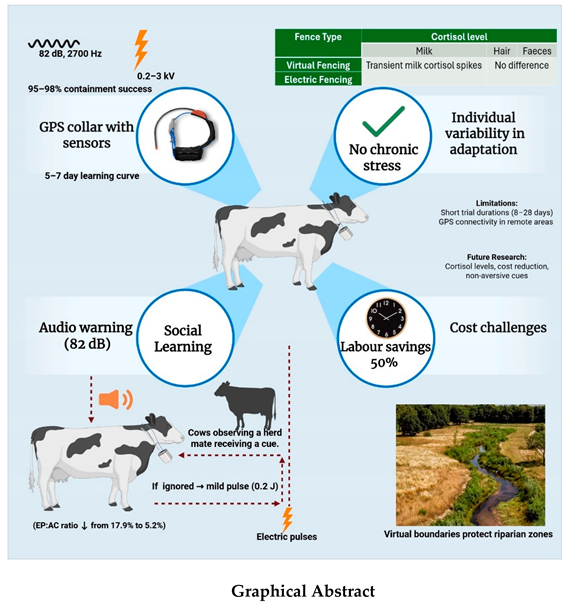

3. The Concept and Mechanism of Virtual Fencing for Cattle

3.1. Learning Behavior and Social Adaptation

3.2. Impact on Livestock Performance and Pasture Management

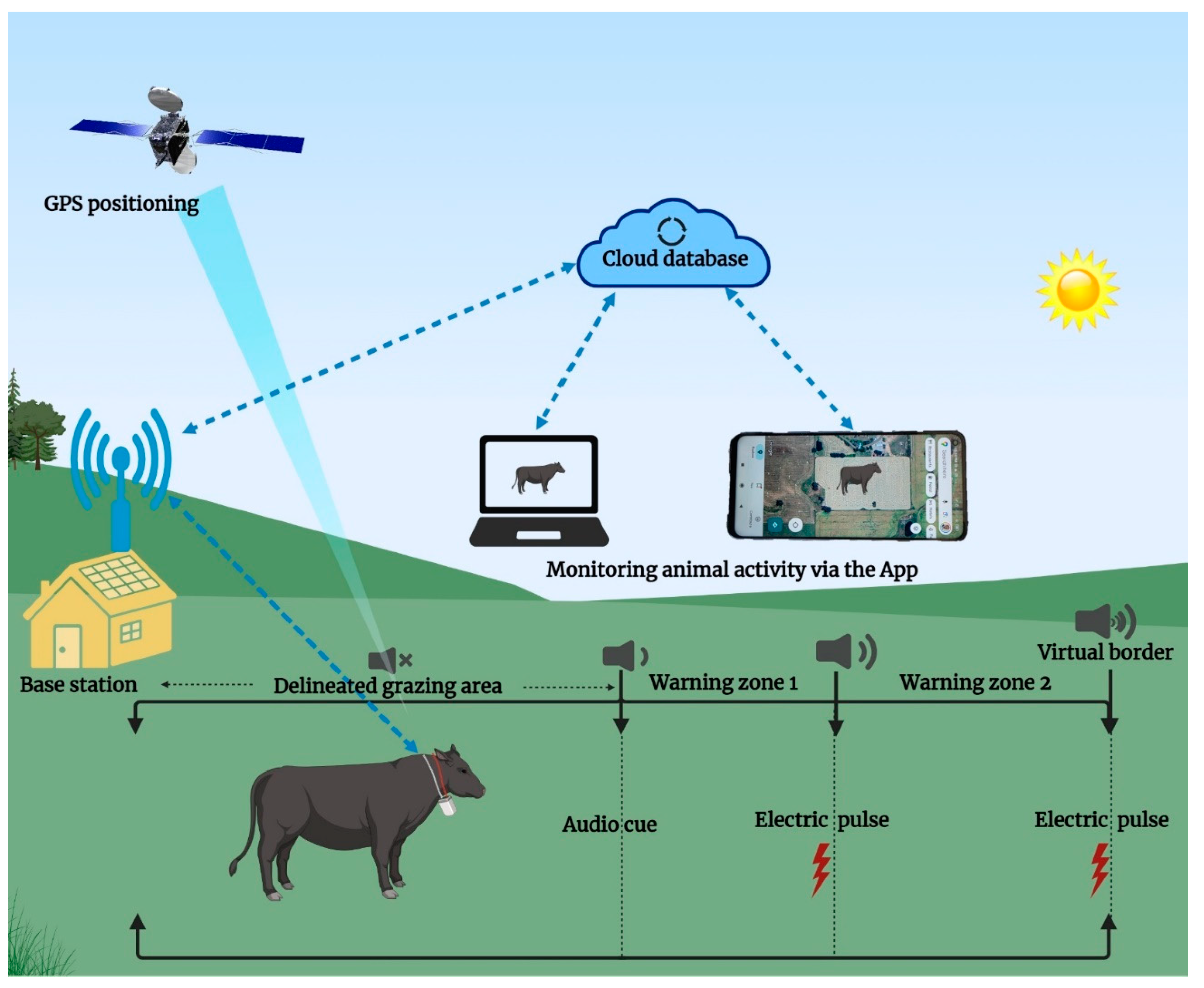

4. Commercial Cattle Monitoring Systems in Pasture-Based Systems

5. Impact of Virtual Fencing Devices on Animal Behaviour and Welfare

5.1. Impact of Device Weight and Electric Pulses on Animal Welfare

5.2. Role of Acoustic Signals in Animal Training

5.3. Cortisol Data and Stress Implications

5.4. Behavioural Adaptations and Welfare Outcomes

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roche, J. R.; Berry, D. P.; Bryant, A. M.; Burke, C. R.; Butler, S. T.; Dillon, P. G.; Macmillan, K. L. A 100-Year Review: A Century of Change in Temperate Grazing Dairy Systems. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 10189–10233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umstätter, C. The Evolution of Virtual Fences: A Review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2011, 75, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadzama, I. U.; Ray, S.; Méité, R.; Mugweru, I. M.; Gondo, T.; Rahman, M. A.; Redoy, M. R. A.; Rohani, M. F.; Kholif, A. E.; Salahuddin, M.; Brito, A. F. Chlorella vulgaris as a Livestock Supplement and Animal Feed: A Comprehensive Review. Animals 2025, 15, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goliński, P.; Sobolewska, P.; Stefańska, B.; Golińska, B. Virtual Fencing Technology for Cattle Management in the Pasture Feeding System—A Review. Agric. 2022, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadzama, I. U.; Ray, S. Precision Livestock Farming in Pasture-Based Dairy Systems: Monitoring Grazing Behavior; Wikifarmer, 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385053381.

- Gadzama, I. U. Virtual Fencing for Livestock Management: Effects on Cattle Behavior, Welfare, and Productivity; ResearchGate, 2025. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388036239.

- Lee, C.; Colditz, I. G.; Campbell, D. L. M. A Framework to Assess the Impact of New Animal Management Technologies on Welfare: A Case Study of Virtual Fencing. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadzama, I. U. How AI is Revolutionizing Animal Farming: Benefits, Applications, and Challenges; Wikifarmer, 2025. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387828770.

- Campbell, D. L. M.; Lea, J. M.; Keshavarzi, H.; Lee, C. Virtual Fencing Is Comparable to Electric Tape Fencing for Cattle Behavior and Welfare. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langworthy, A. D.; Verdon, M.; Freeman, M. J.; Corkrey, R.; Hills, J. L.; Rawnsley, R. P. Virtual Fencing Technology to Intensively Graze Lactating Dairy Cattle. I: Technology Efficacy and Pasture Utilization. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 7071–7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdon, M.; Horton, B.; Rawnsley, R. A Case Study on the Use of Virtual Fencing to Intensively Graze Angus Heifers Using Moving Front and Back-Fences. Front. Anim. Sci. 2021, 2, 663963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdon, M.; Langworthy, A.; Rawnsley, R. Virtual Fencing Technology to Intensively Graze Lactating Dairy Cattle. II: Effects on Cow Welfare and Behavior. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 7084–7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilms, L.; Komainda, M.; Hamidi, D.; Riesch, F.; Horn, J.; Isselstein, J. How Do Grazing Beef and Dairy Cattle Respond to Virtual Fences? A Review. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamuryekung'e, S.; Cox, A.; Perea, A.; Estell, R.; Cibils, A. F.; Holland, J. P.; Waterhouse, T.; Duff, G.; Funk, M.; McIntosh, M. M.; Spiegal, S.; Bestelmeyer, B.; Utsumi, S. Behavioral Adaptations of Nursing Brangus Cows to Virtual Fencing: Insights from a Training Deployment Phase. Animals 2023, 13, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grudzinski, B.; Fritz, K.; Dodds, W. Does Riparian Fencing Protect Stream Water Quality in Cattle-Grazed Lands? Environ. Manage. 2020, 66, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schillings, J.; Holohan, C.; Lively, F.; Arnott, G.; Russell, T. The Potential of Virtual Fencing Technology to Facilitate Sustainable Livestock Grazing Management. Animal 2024, 18, 101231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonne, C.; Alstrup, A. K. O.; Pertoldi, C.; Frikke, J.; Linder, A. C.; Styrishave, B. Cortisol in Manure from Cattle Enclosed with Nofence Virtual Fencing. Animals 2022, 12, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D. M. Virtual Fencing—Past, Present and Future. Rangeland Journal 2007, 29, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jachowski, D. S.; Slotow, R.; Millspaugh, J. J. Good Virtual Fences Make Good Neighbors: Opportunities for Conservation. Anim. Conserv. 2014, 17, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Henshall, J. M.; Wark, T. J.; Crossman, C. C.; Reed, M. T.; Brewer, H. G.; O'Grady, J.; Fisher, A. D. Associative Learning by Cattle to Enable Effective and Ethical Virtual Fences. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 119, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D. M.; Estell, R. E.; Holechek, J. L.; Ivey, S.; Smith, G. B. Virtual Herding for Flexible Livestock Management–A Review. The Rangeland Journal 2014, 36, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D. L.; Lea, J. M.; Haynes, S. J.; Farrer, W. J.; Leigh-Lancaster, C. J.; Lee, C. Virtual Fencing of Cattle Using an Automated Collar in a Feed Attractant Trial. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 200, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdon, M.; Lee, C.; Marini, D.; Rawnsley, R. Pre-Exposure to an Electrical Stimulus Primes Associative Pairing of Audio and Electrical Stimuli for Dairy Heifers in a Virtual Fencing Feed Attractant Trial. Animals 2020, 10, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Campbell, D. L. M. A Multi-Disciplinary Approach to Assess the Welfare Impacts of a New Virtual Fencing Technology. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 637709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, C. S.; O'Connor, R.; Ranches, J.; Bohnert, D. W.; Bates, J. D.; Johnson, D. D.; Davies, K. W.; Parker, T.; Doherty, K. E. Virtual Fencing Effectively Excludes Cattle from Burned Sagebrush Steppe. Rangeland Ecology & Management 2022, 81, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Smith, D. V.; Little, B.; Ingham, A. B.; Greenwood, P. L.; Bishop-Hurley, G. J. Cattle Behavior Classification from the Collar, Halter, and Ear Tag Sensors. Inf. Process. Agric. 2018, 5, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, D.; O'Brien, B.; Coughlan, N. E.; Férard, A.; Ivanov, S.; Halton, P.; Umstätter, C. Virtual Fencing Without Visual Cues: Design, Difficulties of Implementation, and Associated Dairy Cow Behaviour. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 176, 105613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goliński, P.; Sobolewska, P.; Stefańska, B.; Golińska, B. Virtual Fencing Technology for Cattle Management in the Pasture Feeding System—A Review. Agric. 2022, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confessore, A.; Schneider, M. K.; Pauler, C. M.; Aquilani, C.; Fuchs, P.; Pugliese, C.; Dibari, C.; Argenti, G.; Accorsi, P. A.; Probo, M. A Matter of Age? How Age Affects the Adaptation of Lactating Dairy Cows to Virtual Fencing. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costly Fencing Renewal Replaced with Virtual Fencing; The Cows Wear a Collar on Which Hangs a Two-Sided Solar Panel Approximately the Same Size as a Swiss Cowbell. Ontario Farmer 2024, B.10. https://www.proquest.com/magazines/costly-fencing-renewal-replaced-with-virtual-cows/docview/3072070025/se-2?accountid=14723.

- Anderson, D. M.; Hale, C. S. Animal Control System Using Global Positioning and Instrumental Animal Conditioning. U.S. Patent 6,232,880 B1, May 15, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Umstätter, C. The Evolution of Virtual Fences: A Review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2011, 75, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, P.; Stachowicz, J.; Schneider, M. K.; Probo, M.; Bruckmaier, R. M.; Umstätter, C. Stress Indicators in Dairy Cows Adapting to Virtual Fencing. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langworthy, A. D.; Verdon, M.; Freeman, M. J.; Corkrey, R.; Hills, J. L.; Rawnsley, R. P. Virtual Fencing Technology to Intensively Graze Lactating Dairy Cattle. I: Technology Efficacy and Pasture Utilization. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 7071–7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, T. Wearable Tech for Cows Helps Herds Communicate with Farmers. Design Week (Online) 2015, July 28. https://www.proquest.com/magazines/wearable-tech-cows-helps-herds-communicate-with/docview/1699347294/se-2?accountid=14723.

- Verdon, M.; Langworthy, A.; Rawnsley, R. Virtual Fencing Technology to Intensively Graze Lactating Dairy Cattle. II: Effects on Cow Welfare and Behavior. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 7084–7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, A. J.; Novais, F. J.; Fitzsimmons, C. J.; Church, J. S.; da Silva, G. M.; Londono-Mendez, M. C.; Bork, E. W. Evaluating Virtual Fencing as a Tool to Manage Beef Cattle for Rotational Grazing Across Multiple Years. J. Environ. Manage. 381, 125166. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamidi, D.; Grinnell, N. A.; Komainda, M.; Riesch, F.; Horn, J.; Ammer, S.; Traulsen, I.; Palme, R.; Hamidi, M.; Isselstein, J. Heifers Don't Care: No Evidence of Negative Impact on Animal Welfare of Growing Heifers When Using Virtual Fences Compared to Physical Fences for Grazing. Animal 2022, 16, 100614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonne, C.; Alstrup, A. K. O.; Pertoldi, C.; Frikke, J.; Linder, A. C.; Styrishave, B. Cortisol in Manure from Cattle Enclosed with Nofence Virtual Fencing. Animals 2022, 12, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilms, L.; Komainda, M.; Hamidi, D.; Riesch, F.; Horn, J.; Isselstein, J. How Do Grazing Beef and Dairy Cattle Respond to Virtual Fences? A Review. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaser, M. F.; Staahltoft, S. K.; Korsgaard, A. H.; Trige-Esbensen, A.; Alstrup, A. K. O.; Sonne, C.; Pertoldi, C.; Bruhn, D.; Frikke, J.; Linder, A. C. Is Virtual Fencing an Effective Way of Enclosing Cattle? Personality, Herd Behaviour and Welfare. Animals 2022, 12, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Colditz, I. G.; Campbell, D. L. M. A Framework to Assess the Impact of New Animal Management Technologies on Welfare: A Case Study of Virtual Fencing. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinnell, N. A.; Hamidi, D.; Komainda, M.; Riesch, F.; Horn, J.; Traulsen, I.; Palme, R.; Isselstein, J. Supporting Rotational Grazing Systems with Virtual Fencing: Paddock Transitions, Beef Heifer Performance, and Stress Response. Animal 2025, 19, 101416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musinska, J.; Skalickova, S.; Nevrkla, P.; Kopec, T.; Horky, P. Unlocking Potential, Facing Challenges: A Review Evaluating Virtual Fencing for Sustainable Cattle Management. Livest. Sci. 2025, 105693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versluijs, E.; Niccolai, L. J.; Spedener, M.; Zimmermann, B.; Hessle, A.; Tofastrud, M.; Devineau, O.; Evans, A. L. Classification of Behaviors of Free-Ranging Cattle Using Accelerometry Signatures Collected by Virtual Fence Collars. Front. Anim. Sci. 2023, 4, 1083272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamuryekung'e, S.; Cox, A.; Perea, A.; Estell, R.; Cibils, A. F.; Holland, J. P.; Waterhouse, T.; Duff, G.; Funk, M.; McIntosh, M. M.; Spiegal, S.; Bestelmeyer, B.; Utsumi, S. Behavioral Adaptations of Nursing Brangus Cows to Virtual Fencing: Insights from a Training Deployment Phase. Animals 2023, 13, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D. L. M.; Haynes, S. J.; Lea, J. M.; Farrer, W. J.; Leigh-Lancaster, C. J.; Lee, C. Temporary Exclusion of Cattle from a Riparian Zone Using Virtual Fencing Technology. Animals 9, 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, C. S.; O'Connor, R. C.; Ranches, J.; Bohnert, D. W.; Bates, J. D.; Johnson, D. D.; Davies, K. W.; Parker, T.; Doherty, K. E. Using Virtual Fencing to Create Fuel Breaks in the Sagebrush Steppe. Rangeland Ecology & Management 2023, 89, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, A. J.; Novais, F. J.; Durunna, O. N.; Fitzsimmons, C. J.; Church, J. S.; Bork, E. W. Evaluation of the Technical Performance of the Nofence Virtual Fencing System in Alberta, Canada. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 10, 100713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, D.; Grinnell, N. A.; Komainda, M.; Wilms, L.; Riesch, F.; Horn, J.; Hamidi, M.; Traulsen, I.; Isselstein, J. Training Cattle for Virtual Fencing: Different Approaches to Determine Learning Success. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2024, 273, 106220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, B. D.; Wagner, K. L.; Reuter, R.; Goodman, L. E. Use of Virtual Fencing to Implement Critical Conservation Practices. Rangelands 2024, 47, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, P.; Stachowicz, J.; Schneider, M.; Probo, M.; Bruckmaier, R. M.; Umstätter, C. PSVI-16 Conditioning Dairy Cows to a Virtual Fencing System Is Compatible with Animal Welfare. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, 334–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, D.; Hütt, Ch.; Komainda, M.; Grinnell, N. A.; Horn, J.; Riesch, F.; Hamidi, M.; Traulsen, I.; Isselstein, J. Grid Grazing: A Case Study on the Potential of Combining Virtual Fencing and Remote Sensing for Innovative Grazing Management on a Grid Base. Livest. Sci. 2023, 278, 105373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confessore, A.; Aquilani, C.; Nannucci, L.; Fabbri, M. C.; Accorsi, P. A.; Dibari, C.; Argenti, G.; Pugliese, C. Application of Virtual Fencing for the Management of Limousin Cows at Pasture. Livest. Sci. 2022, 263, 105037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colusso, P. I.; Clark, C. E. F.; Ingram, L. J.; Thomson, P. C.; Lomax, S. Dairy Cattle Response to a Virtual Fence When Pasture on Offer Is Restricted to the Post-Grazing Residual. Front. Anim. Sci. 2021, 2, 791228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomax, S.; Colusso, P.; Clark, C. E. F. Does Virtual Fencing Work for Grazing Dairy Cattle? Animals 2019, 9, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilani, C.; Confessore, A.; Bozzi, R.; Sirtori, F.; Pugliese, C. Review: Precision Livestock Farming Technologies in Pasture-Based Livestock Systems. Animal 2022, 16, 100429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, T. Virtual fencing systems: balancing production and welfare outcomes. Livestock 2023, 28, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Additional References (numbered 60-65).

- Hamidi, D.; Grinnell, N. A.; Komainda, M.; Wilms, L.; Riesch, F.; Horn, J.; Hamidi, M.; Traulsen, I.; Isselstein, J. Training Cattle for Virtual Fencing: Different Approaches to Determine Learning Success. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2024, 273, 106220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confessore, A.; Aquilani, C.; Nannucci, L.; Fabbri, M. C.; Accorsi, P. A.; Dibari, C.; Argenti, G.; Pugliese, C. Application of Virtual Fencing for the Management of Limousin Cows at Pasture. Livest. Sci. 2022, 263, 105037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, A. J.; Novais, F. J.; Fitzsimmons, C. J.; Church, J. S.; da Silva, G. M.; Londono-Mendez, M. C.; Bork, E. W. Evaluating Virtual Fencing as a Tool to Manage Beef Cattle for Rotational Grazing Across Multiple Years. J. Environ. Manage. 381, 125166. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.; Cornish, A. Independent Scientific Literature Review on Animal Welfare Considerations for Virtual Fencing; Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry: 2022.

- Lund, S. M.; Jacobsen, J. H.; Nielsen, M. G.; Friis, M. R.; Nielsen, N. H.; Mortensen, N. Ø.; Skibsted, R. C.; Aaser, M. F.; Staahltoft, S. K.; Bruhn, D.; Sonne, C.; Alstrup, A. K. O.; Frikke, J.; Pertoldi, C. Spatial Distribution and Hierarchical Behaviour of Cattle Using a Virtual Fence System. Animals 2024, 14, 2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdon, M.; Hunt, I.; Rawnsley, R. The Effectiveness of a Virtual Fencing Technology to Allocate Pasture and Herd Cows to the Milking Shed. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 6161–6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, P.; Stachowicz, J.; Schneider, M. K.; Probo, M.; Bruckmaier, R. M.; Umstätter, C. Stress Indicators in Dairy Cows Adapting to Virtual Fencing. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umstätter, C.; Brocklehurst, S.; Ross, D. W.; Haskell, M. J. Can the Location of Cattle Be Managed Using Broadcast Audio Cues? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013, 147, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grumett, D.; Butterworth, A. Electric Shock Control of Farmed Animals: Welfare Review and Ethical Critique. Anim. Welf. J. 2022, 31, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heins, B. J.; Pereira, G. M.; Sharpe, K. T. Precision Technologies to Improve Dairy Grazing Systems. JDS Commun. 2023, 4, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wróbel, B.; Zielewicz, W.; Staniak, M. Challenges of Pasture Feeding Systems—Opportunities and Constraints. Agric. 2023, 13, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occhiuto, F.; Vázquez-Diosdado, J. A.; King, A. J.; Kaler, J. Using Precision Technology to Investigate Personality and Plasticity of Movement in Farmed Calves and Their Associations with Weight Gain. Anim. Sci. Proc. 2023, 14, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holohan, C.; Gordon, A.; Palme, R.; Buijs, S.; Lively, F. An Assessment of Young Cattle Behaviour and Welfare in a Virtual Fencing System. Proc. XXV Int. Grassl. Congr. 2023, KY, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Herlin, A.; Brunberg, E.; Hultgren, J.; Högberg, N.; Rydberg, A.; Skarin, A. Animal Welfare Implications of Digital Tools for Monitoring and Management of Cattle and Sheep on Pasture. Animals 2021, 11, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colusso, P. I.; Clark, C. E. F.; Lomax, S. Should Dairy Cattle Be Trained to a Virtual Fence System as Individuals or in Groups? Animals 2020, 10, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, K.; Ivanov, S.; Kulatunga, C.; Donnelly, W. Fog-Enabled WSN System for Animal Behavior Analysis in Precision Dairy. In 2017 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC); IEEE: 2017; pp 504-510.

- French, P.; O'Brien, B.; Shalloo, L. Development and Adoption of New Technologies to Increase the Efficiency and Sustainability of Pasture-Based Systems. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2015, 55, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

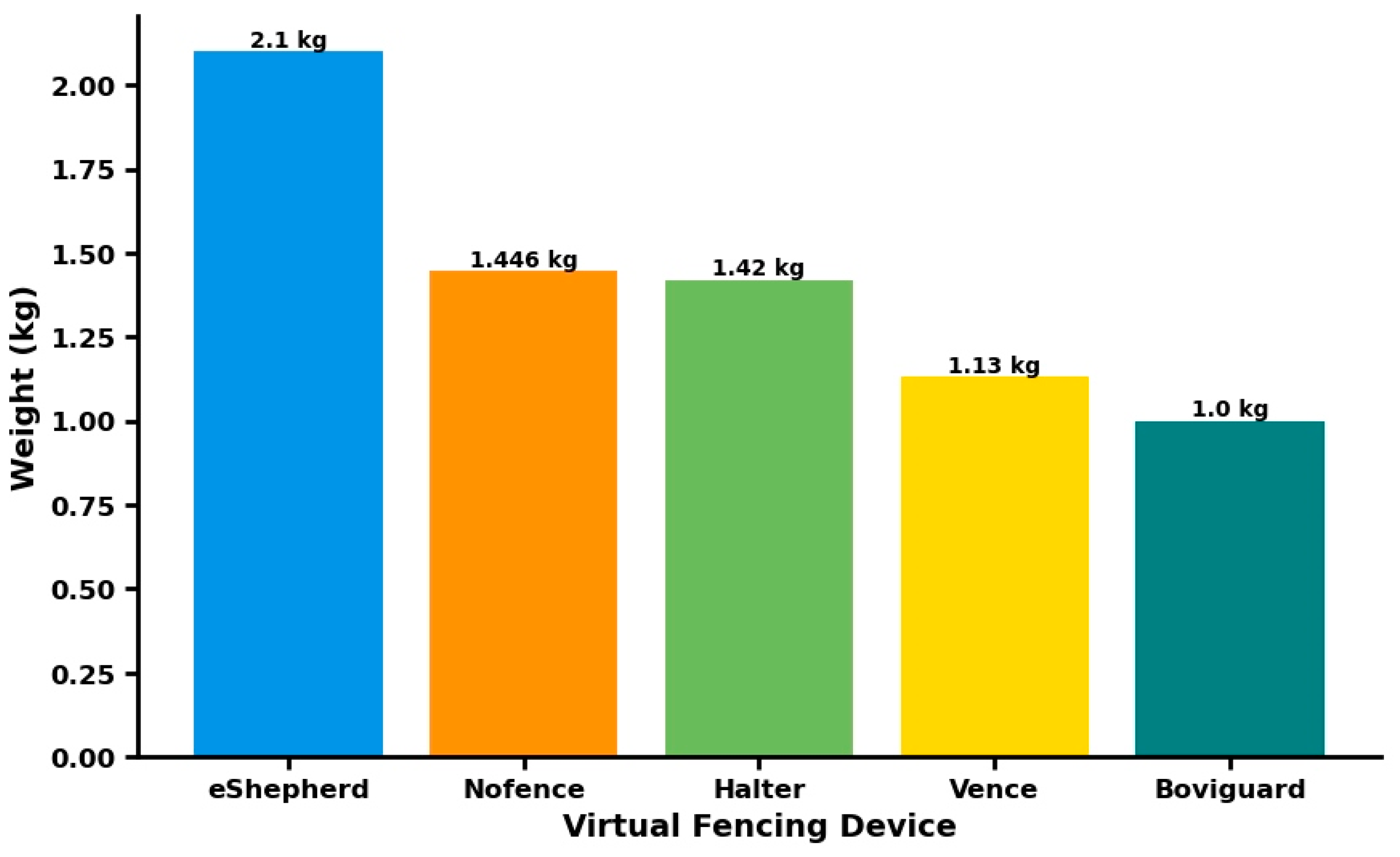

| Year | Animal Species/Breed | Virtual Fencing Device | Device Manufacturer | Location on Animal | Behavior/Parameters Measured | Reference |

| 2025 | Kinsella Composite (KC) crossbred beef cattle (heifers & cows) | Nofence® | Nofence AS, Batnfjordsøra (Norway) | Neck collar with adjustable strap | Electrical pulses (EPs) and audio cues (ACs) received EP-to-AC ratio (E:A) Inclusion zone frequency (IZF, % time within boundaries) Escape frequency/duration Step counts (via leg sensor) Lying/standing time |

[49] |

| 2025 | Kinsella Composite (KC) crossbred beef cattle (heifers & cows) | IceQube+ activity sensor | Peacock Technologies (Stirling, UK) | Lower left rear leg | Activity patterns (step counts) Lying vs. standing time |

[49] |

| 2025 | Fleckvieh heifers | Nofence® | Nofence AS, Batnfjordsøra (Norway) | Neck | Success ratio (auditory:electrical), escape alerts, GNSS, faecal cortisol, body weight gain | [50] |

| 2024 | Fleckvieh heifers | Nofence® | Nofence AS, Batnfjordsøra (Norway) | Neck collar | Behavior metrics, herbage intake, stress indicators (faecal cortisol) | [51] |

| 2024 | Angus cows | Vence® VF system | Vence (vence.io; Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ) | GPS-enabled VF collar | Percentage of cow locations in different management zones (riparian exclusion, ridge exclusion, grazing area, large-area exclusions), noncompliance | [52] |

| 2024 | Lactating Holstein-Friesian | Nofence® | Nofence AS, Batnfjordsøra (Norway) | Neck collar | Acoustic warnings, electrical pulses, step count, milk yield, hair cortisol | [29] |

| 2024 | Pasture-raised Angus beef, Jersey dry cows | eShepherd®) | Gallagher, Hamilton (New Zealand) | Collar | Proximity to boundary (beep/pulse response) | [30] |

| 2023 | Dairy cows | Nofence® | Nofence AS, Batnfjordsøra (Norway) | Neck collar | Cow positions, audio tones (AT), electric pulses (EP), activity | [53] |

| 2023 | Free-ranging cattle | Nofence® | Nofence AS, Batnfjordsøra (Norway) | Below the neck | Accelerometry-inferred behaviors (feeding, resting, scratching) | [45] |

| 2023 | Fleckvieh heifers | Nofence® (Model: C2.1) |

Nofence, AS, Batnfjordsøra (Norway) | Attached to the neck | GPS data (walking distance, lying time, spatial pattern of movement), lying time (validated with observational data), active time, spatial distribution (Camargo’s Index of Evenness) | [54] |

| 2023 | Cattle | Nofence® | Nofence AS, Batnfjordsøra (Norway) | Neck collar | Distance to boundary, acoustic warnings, aversive stimuli | [28] |

| 2022 | Cattle | Vence® | Vence Corporation, San Diego (USA) | GPS collar | Location, welfare, animal distribution | [48] |

| 2022 | Pregnant Limousin cows | Nofence® | Nofence AS, Batnfjordsøra (Norway) | Neck collar | Hair cortisol, signal responses | [55] |

| 2022 | 12 pregnant Angus cows | Nofence® | Nofence AS, Batnfjordsøra (Norway) | Neck collar | Activity levels | [41] |

| 2021 | Dairy cattle (Holstein-Friesian) | Pre-commercial prototype (eShepherd®) | Agersens, Melbourne (Australia) | Neckband | Location, stimuli count, time per zone, speed | [56] |

| 2021 | Lactating Dairy Cows (Friesian/Jersey) | eShepherd pre-commercial prototype | Agersens, Melbourne (Australia) | Neckband | Time in exclusion zone, stimuli ratio | [34] |

| 2020 | Non-lactating Holstein Friesian | GPS/DGPS collar with stimuli unit | MediaTek (Hsinchu, Taiwan), Trimble (Sunnyvale, USA) | Neck collar | Boundary challenges, behavior (grazing/walking/drinking) | [27] |

| 2019 | Holstein-Friesian dairy cows | eShepherd™ collar (automated prototype) | Agersens, Melbourne (Australia) | Top of the neck | Grazing time, GPS position, audio/electric pulses | [57] |

| 2018 | Cattle | Halter® | Halter (New Zealand) | Neck-collar + head-halter | Health (body temperature), response to audio/tactile/visual/electrical stimuli | [26] |

| 2015 | Dairy cattle | Cowbell collar (audible alarm + shock) | Cambridge Industrial Design (Cambridge, UK), Teagasc (Ireland) | Around the neck | Grazing, socializing, lying, milk yields | [35] |

| 2001 | Cattle | Directional Virtual Fence (DVFTM) | Anderson & Hale (Patent) | GPS collar | Location relative to boundary | [31] |

| Device | Sensors | Outputs / Functionalities | Country |

| Datamuster | Walk-over-weigh (weighing crate) | Maternal parentage, reproductive efficiency, growth rates, calving, property mapping | Australia |

| smaXtec (GmbH) | Accelerometer, thermometer | pH, body temperature, calving, heat detection, health, rumination | Austria, Germany |

| Ceres Tag | GPS, Accelerometer | Activity, geofencing, health monitoring | Australia |

| Allflex SenseHub | Accelerometer | Health, rumination, feed intake, heat detection, calving, activity, heat stress | Israel |

| Moomonitor+ | Accelerometer | Activity, resting, feeding, rumination, heat detection | Ireland |

| IceTag / IceQube | Accelerometer | Lameness, activity, resting, heat detection | UK |

| Moocall | Accelerometer | Calving, heat detection | Ireland |

| CalveSense | Accelerometer | Calving monitoring | Israel |

| eShepherd® | GPS, Accelerometer | Virtual fencing, activity monitoring, pasture management | Australia |

| Halter® | GPS, Accelerometer | Virtual fencing, activity monitoring, pasture management | New Zealand |

| Vence® | GPS, Accelerometer | Virtual fencing, activity monitoring, pasture management | USA |

| Nofence® | GPS, Accelerometer | Virtual fencing, activity monitoring | Norway |

| digitanimal | GPS, Accelerometer, thermometer | Activity, geofencing, body temperature | Spain |

| Study Reference | Animal Type (n) | Device (Weight) | Electric Pulse | Acoustic Signal | Cortisol Data | Key Behavioral & Welfare Findings |

| [43] | Beef heifers (n=32) | Nofence® (1.45 kg) | 0.2 J at 3 kV (max 3) | 82 dB (increasing pitch) | No significant FCM differences | Comparable to EF, adaptation over time, initial slower transitions |

| [49] | Yearling beef heifers, bulls, cows + calves |

Nofence® (1.45 kg) |

Mild electrical pulse (1.5-3 kv) |

Audio cues (frequency not specified) | Not measured | Cattle learned to avoid virtual boundaries with minimal welfare concerns. The system provided effective containment, despite some collar losses, without major welfare issues. Animals adapted well, showing no significant behavioral stress. It was also effective in winter conditions, with no adverse welfare effects. |

| [37] | Yearling heifers (n=49) | Nofence® (1.45 kg) |

1.5–3 kV | 82 dB (5–20 s) | Not measured | Heifers adapted to VF boundaries in 5–7 days; E:A ratio decreased from 17.9% (training) to 5.2% (grazing). High individual variability in response. |

| [37] | First-calf cows (n=39, same animals as heifers in Year 1) | Nofence® (1.45 kg) |

1.5–3 kV | 82 dB (5–20 s) | Not measured | Cows retained prior learning (E:A ratio: 1.6% during re-training, 2.2% during grazing). Presence of uncollared calves did not significantly reduce containment (>99% compliance). |

| [37] | Bulls (n=2 in Year 1; n=3 in Year 2) | Nofence® (1.45 kg) |

1.5–3 kV | 82 dB (5–20 s) | Not measured | Excluded from analysis due to small sample size. |

| [51] | Fleckvieh heifers | 1.45 kg | 0.2 J at 3 kV | 82 dB at 1 m (rising pitch) | No effect on faecal cortisol compared to a physical fence | Minor and inconsistent differences in activity budget |

| [67] | Dairy cows (n=80) |

Halter® (1.4 kg) |

Up to 0.18 J (20 µs) | 2700 Hz crescendo | Not reported | 90% containment (<1.7 min beyond fence), autonomous herding by day 4, decreasing pulse ratio |

| [66] | Angus cattle (n=17) | Nofence® | 0.2 J (1 s) | 82 dB rising tone (5-20 s) | Not measured | The cattle effectively responded to audio alerts and remained securely contained within the enclosure. No spatial issues or welfare concerns were observed. |

| [52] | Angus cows (n=12) | Vence® | 800V (0.5 s) | 0.5-s auditory cue | Not reported | Reduced exclusion use, grazing distribution changes, some noncompliance |

| [33] | Dairy cows (n=20) | Nofence® | 25x weaker than EF; 0.1 ± 0.7/day | Audio tone (1.9 ± 3.3/day) |

Milk cortisol: no difference vs. EF | Successful herd conditioningNo welfare differences vs. EFMore vocalizations/displacements (VF) |

| [14] | Nursing Brangus cows (n = 28) | Nofence® (1.45 kg) |

Mild electric pulse | - | Not reported | Cows learned to avoid restricted zones and spent more time in containment areas. They needed fewer audio-electric cues, relied more on auditory signals, traveled less daily, explored smaller areas, and showed reduced overall activity. Training minimized negative impacts on their comfort, well-being, and welfare. |

| [17] | Angus cows (n=5) | Nofence® |

0.2 J at 3 kV for one second | 82 dB tones increasing in pitch for 5–20 s | Manure cortisol concentrations ranged from 12 to 42 ng/g w/w, with a mean of 20.6 ± 5.23 ng/g w/w. No significant differences among individuals. Levels remained stable throughout the study | No negative effects on cattle behavior and welfare VF was comparable to traditional electric fencing. There was no evidence of stress from VF, as indicated by manure cortisol levels. The study suggests using manure cortisol analysis as a noninvasive stress measure for large grazers during VF. |

| [55] | Limousin cows (n=20) | Nofence® | Low electric pulse | Rise tone scale of sounds lasting from 5 s to 20 s | Hair cortisol concentration (HCC) in pg/mg. Mean Ti (beginning): 1.14 pg/mg; Mean Tf (end): 0.82 pg/mg. No significant differences were observed in HCC before and after the VF treatment | Cows learned with fewer stimuli over time and a lower ratio of sounds to pulses. They stayed in designated zones more consistently, with minimal escapes. Stress levels remained stable, and shorter audio tones showed better responsiveness. |

| [12] | Lactating dairy cows (mixed breed) (n=30) | eShepherd® prototype (~1.4 kg) |

Short, sharp (kV range; confidential) Short, sharp |

Non-aversive audio tone | Increased milk cortisol levels: higher at d5 (VF) vs. d8 (EF) | Lower activity/grazing (d4–6)No aversion behaviorsJaw abrasions, influenced grazing behavior (study halted) Cows were successfully contained behind the virtual fence for 10 days. |

| [56] | Non-lactating dry cows (Holstein-Friesian) (n=34) | eShepherd® prototype ~1.4 kg (~725 g unit) |

Short, sharp (kV range; confidential) Short |

Distinctive audio tone | Not measured | Cows learned to remain within the VF over time, even with restricted feed. Restricted cows received more stimuliLearned retention (≤17% AT→EP)Feed motivation influenced behavior |

| [10] | Dairy cattle | eShepherd® (0.73 kg) |

Short, sharp electrical pulse sequence in the kilovolt range | Distinctive but nonaversive audio cue within the animal’s hearing range | Not reported | Cows learned to respond to audio cues to avoid electrical stimuli, with a daily ratio of 0.18 ± 0.27. Stayed within the inclusion zone ≥99% of the time. Pasture depletion slightly reduced efficacy, and more audio cues were needed when entering new paddocks. VF effectively contained the herd without affecting production metrics, but did not fully prevent entry into the exclusion zone. Some cows developed jaw abrasions from the neckband, and social learning may have occurred. |

| [9] | Beef steers (n=64) |

eShepherd® (∼1.4 kg) | Low voltage 800 V (<1 s) |

785 Hz | Fecal cortisol metabolite (FCM) concentrations (ng/g of dry feces). No differences between fence types overall. Concentrations decreased across time for all cattle. Cohort 1 had significantly higher overall concentrations than cohort 2 | VF successfully contained animals over 4 weeks with minimal welfare impacts. Animals spent slightly less time lying (<20 min/day). They all learned to respond to audio cues, showing no avoidance behaviors or significant stress differences (measured via FCM). Individual learning rates varied. Further research is needed for pastured dairy and beef cattle. |

| [57] | Dairy cows (n=12) | eShepherd® (~1.4 kg) |

Short, sharp pulse in the kilovolt range | Distinctive audio tone (within the animal’s hearing range) | Not measured | Cows were successfully contained 99% of the time, but there was significant variation in stimuli received and paddock usage among individuals. Some cows experienced potential welfare costs due to repeated electrical pulses and possible aversion to the fence line. Further research is needed on the long-term welfare impacts. |

| Reference | Summary of Main Findings | Limitations of the Study | Future Directions/Recommendations |

| [43] | VF success ratio improved (94.6% to 97.9%); no welfare/weight gain differences vs EF; proposed 90% success threshold benchmark. | Short duration (8 weeks); double-fence setup; infrequent cortisol sampling; high forage availability; human intervention. | Longer-term studies; open-range testing; frequent stress sampling; varied forage conditions; minimal human intervention. |

| [49] | Naïve cattle learned to associate audio cues (ACs) with electrical pulses (EPs) within 5–7 days, reducing EP-to-AC ratio from 17.9% (training) to 5.2% (grazing). Heifers retained learning over a 300-day hiatus; first-calf cows with prior VF experience had even lower EP rates (1.6% re-training, 2.2% grazing). Cattle stayed within VF boundaries >99% of the time, though cows with uncollared calves had slightly more escapes. Individual variability observed (high-, moderate-, low-stimuli cohorts), but all achieved similar containment rates. Stocking density influenced cow behavior (higher density = more ACs/EPs). |

No non-VF control group for direct comparisons. Confounding factors (uncollared calves, prior VF experience) complicated behavioral interpretations. Small sample sizes for high-stimuli cohorts (n=5–7). Limited to temperate grasslands; may not generalize to arid/tropical systems. Ethical concerns about EPs, though no adverse welfare impacts noted. |

Further research on long-term welfare effects. Investigate scalability for commercial herds. Optimize training durations. Explore alternatives to EPs for welfare-sensitive applications. Test VF in diverse climates and production systems. |

| [37] | Network connectivity was generally good, with mean connection intervals within the optimal 15-minute window. Poor connections occurred <1% of the time. Collars primarily used 4G-LTE, but rural areas in Canada may have limited network availability. Most collar failures were due to connectivity issues, with older (v2.1) collars showing increased failures in the second year. Physical collar loss occurred, especially with bulls. Battery charge remained high (>96%) in all trials, including winter, though solar charging was lower in winter. Habitat and animal behavior influenced charging. Collar battery capacity was sufficient for cattle in both summer and winter. |

Limited generalizability due to study being conducted in only two Alberta locations; broader rural Canada has poor cellular access. Study duration may have been insufficient to assess long-term collar performance. Unmeasured factors (cloud cover, precipitation, animal behavior, wildfires) could affect solar charging. Focused on technical performance; impacts on animal behavior, welfare, and grazing management need further study. |

Longer-term studies to assess collar durability and performance over multiple years. Research in areas with poorer network coverage to evaluate VF feasibility. Further investigation into environmental and behavioral factors affecting solar charging. Studies on animal welfare, behavior, and grazing efficiency under VF systems. Improved collar design (e.g., better fit, reduced loss risk, enhanced connectivity in remote areas). |

| [30] | Solar-powered eShepherd collars reduced fencing costs and enabled dynamic grazing. | Cellular dependency, small sample (n=60), and no cost-benefit comparisons. | Off-grid collar solutions, larger trials, and diversified trade strategies. |

| [29] | No age-related differences in VF learning; younger cows received more ATs later, older cows responded faster. No long-term stress (milk yield, hair cortisol stable). | Short (31-day) trial; small sample (n=20); only Holstein-Friesians; heat waves may have confounded results. | Longer studies; multi-breed trials; forage availability effects. |

| [67] | Dairy cows using the Halter VF system showed rapid learning, with electrical pulse (EP) rates dropping from 60% (Day 1) to 2.6% post-training. 90% of cows spent ≤1.7 min/day beyond boundaries, and 50% received no paddock pulses by the final week. Superior to earlier VF systems due to bidirectional sound, vibration, and machine learning. | Short 28-day period; no long-term welfare metrics; sample limited to mid-lactation cows in one region; operational mismanagement caused pulse spikes. | Longer-term studies; welfare assessments (e.g., cortisol); economic feasibility analysis; testing in diverse environments. |

| [13] | No welfare differences between VF and PF in weight gain/lying behavior; lower FCM in VF cattle (P=0.0165). Learning evidenced by reduced electric:acoustic signal ratio (P=0.0014). | Small sample (n=13 studies); beef cattle focus; short trial durations; variable protocols; FCM may miss acute stress. | Long-term dairy cow studies; standardized protocols; assess individual learning differences; multimodal stress indicators. |

| [66] | No consistent leadership hierarchy found in Angus cows using Nofence© (W=0.15, p<0.001). Daily rank variability suggests dynamic social interactions rather than stable leadership. | GPS inaccuracies (3.5-10 m); short observation period (45 days); focused on spatial metrics rather than direct social interactions. | Longer observation periods; integrate direct interaction data; improve GPS precision; assess age/experience effects. |

| [50] | Heifers successfully learned virtual fencing (VF) over 12 days, showing: Fewer strong reactions (scores 2 & 3) & more mild reactions (score 1). Increased acoustic signals & decreased electric pulses (higher success ratio). Collar data showed a 91.3% success ratio by trial end. Improved confidence ratio (phases 2 → 3). Faster mode switching (teach → operate) in Round 2 vs. Round 1. Cattle learn to associate audio cues with shocks, adjusting behavior to avoid pulses. |

Only 37% of collar cues were observed (group dynamics hindered tracking). Bias risk: Observers focused on the first reacting heifer. Technical issues: Inconsistent acoustic signals before mode activation across collars. Training variables: Unclear if 12 days is optimal; physical fence (PF) proximity may influence learning. Single escape incident after PF removal. Small pasture size (3000 m²) and visual support from physical fences may limit real-world applicability |

Refine observation methods for group settings. Improve collar algorithms for consistency. Study longer training periods & PF-VF distance effects. Test VF reliability in PF-free environments. Explore individual vs. herd learning differences. Single escape incident suggests further research is needed on fence distance effects. Confidence ratio requires refinement. |

| [45] | Tri-axial accelerometer data from collars effectively classified cattle behaviors (accuracy: 0.998). Orientation correction didn't improve performance. 20-second smoothing window optimized results. Rare behaviors were classified but with lower accuracy. | Short-duration behaviors excluded; individual variability not assessed; smoothing may obscure rapid transitions; rare behaviors underrepresented. | Include short-duration behaviors; account for individual differences; optimize smoothing parameters; collect more rare behavior data. |

| [52] | Cows adapted to VF within 3 days; EP/AT ratio declined. No lasting welfare impacts (milk yield, cortisol stable). More vocalizations/displacements initially. | Small sample (n=20); short duration; group-based training; controlled conditions. | Individual training protocols; on-farm trials; larger/longer welfare assessments. |

| [4] | Virtual fencing (eShepherd, Nofence, etc.) reduces labor/costs and benefits ecologically sensitive areas. Auditory cues minimize welfare concerns, but individual learning varies. | High costs; variable efficacy in large/diverse herds; GPS reliability issues; underdeveloped regulations. | Cost reduction; improve GPS reliability; welfare optimization; stakeholder engagement for regulatory frameworks. |

| [53] | VF collars showed 92% precision for lying time detection Strong correlation between UAV RGBVI and herbage changes Behavior changes: ↓ lying time, ↑ walking distance over days Improved spatial distribution (Camargo's Index) Random forest model showed moderate correlation (R²=0.43) between UAV data and animal activity Demonstrated potential for "grid grazing" precision management |

Small-scale case study: Only 2 pastures/treatment for 15 days Limited imagery: RGB-only (no NIR/NDVI data) Environmental variables not fully controlled Potential animal acclimatization bias |

Larger-scale trials needed for validation Incorporate NIR/NDVI sensors for better pasture assessment Study forage scarcity scenarios Develop decision support systems for practical farming use Explore long-term effects of grid grazing |

| [14] | 98% containment; 76% fewer electric cues; rapid learning; reduced movement/exploration. | Individual variability; artificial pen setting; no calf data; short duration (12 days); audio design questions. | Pasture testing; include calves; longer trials; optimize auditory signals; assess social learning. |

| [72] | Pasture systems provide ecosystem services (carbon sequestration, biodiversity) and nutritionally enhanced milk (higher CLA/omega-3). Rotational grazing and virtual fencing improve sustainability, but continuous grazing risks degradation. Multi-species/silvopastoral systems enhance resilience. | Focused on temperate regions; limited long-term data on innovations; economic feasibility of technologies understudied; climate change impacts not addressed. | Context-specific research; long-term studies of grazing innovations; cost-benefit analyses; tropical/arid system adaptations. |

| [71] | Wearables (e.g., SCR Heatime Pro+) showed moderate-high accuracy for rumination/eating. Satellite NDVI correlated well with forage biomass (r=0.74–0.94). Virtual fencing (e.g., Nofence) contained cattle without welfare harm. | Wearables less accurate in grazing vs. confinement. Satellite limitations: weather dependency, multi-species pastures. Virtual fencing lacked long-term welfare/economic data. High costs hinder small-scale adoption. | Pasture-specific algorithm refinements, cost reduction, and longitudinal studies on scalability. Autonomous tools (e.g., CowBot) need further validation. |

| [73] | Personality matters: Consistent activity differences (walking distance) between calves Active calves grow faster: Positive correlation between movement and weight gain Predictable plasticity: Personality type influences environmental adaptation |

Controlled environment: May not reflect all farm conditions Limited behaviors: Focused mainly on locomotion Small sample: 64 calves total |

Expand to production traits Develop personality-based management Include more behavior metrics |

| [48] | 42% reduction in fine fuel biomass within VF boundaries 50% forage utilization inside vs 5% outside fuel breaks High containment: Dry cows (100%) vs cow/calf pairs (75%) Low shock rates: 2.3/day (dry cows), 10.1/day (cow/calf pairs) Effective learning: Cattle associated audio cues (0.5s tone) with boundaries Water access improved containment |

Case study design limits generalizability Mixed groups may have influenced behavior No cortisol measurements for welfare assessment Short 30-day trial may not show long-term effects No visual cues with virtual boundaries |

Longer-term studies on habituation Welfare assessments (e.g., cortisol levels) Separate trials for dry cows vs cow/calf pairs Visual cue integration to aid learning Testing in diverse landscapes |

| [74] | No welfare difference: Similar stress (faecal cortisol) and behavior between VF and EF Equal growth rates: No difference in daily weight gain Learning curve: Shock frequency decreased after initial period Individual variation: Different learning speeds among calves |

Short duration: 21-day grazing period Limited population: Dairy-origin calves only Missing specs: No VF pulse details provided Single stress measure: Only cortisol metabolites analyzed |

Longer-term studies Breed/age comparisons Standardized VF parameters Multi-measure welfare assessment |

| [17] | No cortisol changes (20.6±5.23ng/g) over 18 days; stable individual levels (12-42ng/g); supports noninvasive monitoring. | Small sample (n=5); short duration; no control group; methodological cortisol variability; pregnant cows only. | Larger samples; longer studies; include controls; standardize cortisol methods; diverse physiological states. |

| [70] | Electric shocks in farm management (fencing, trainers, prods) inherently cause pain, raising ethical concerns unless justified by welfare benefits. Virtual fencing allows controlled shocks but may disproportionately affect slow learners. Technologies like prods/poultry wires were deemed ethically indefensible due to stress. | Reliance on manufacturer data may underreport risks. Long-term behavioral impacts (especially in sheep) were insufficiently explored. Gaps in validated non-aversive alternatives (e.g., tactile collars). Societal desensitization to animal pain was theorized but not tested. | Longitudinal welfare studies, interdisciplinary research (ethics/tech/economics), and development of non-aversive alternatives. |

| [57] | PLF tools (RFID, GPS, accelerometers) enable monitoring of health, behavior, and pasture use. Virtual fencing reduces infrastructure but has welfare/response variability. Remote sensing (UAVs/satellites) aids biomass assessment, though integration with sensors is limited. | Battery life/transmission range constraints, high costs, variable animal responses to virtual fencing, remote sensing accuracy affected by vegetation/weather. | Improve battery/connectivity solutions; cost reduction; standardize virtual fencing protocols; integrate sensor/remote sensing data. |

| [61] | Rapid learning: 89% reduction in electric pulses over 4 trials Effective containment: 92% success rate in final trial No chronic stress: HCC levels remained stable (Δ=0.07μg/g). No hair cortisol changes; breed-specific learning. Behavior adaptation: Audio response time improved by 65% |

Limited to adult Limousins Short duration (21 days) Single-breed study; group training effects; No pasture utilization data Small cortisol sample (n=16); 2G dependency. |

Long-term welfare studies (6+ months) Multi-breed trials (Angus, Hereford) Individual training Calf-specific protocols Grazing efficiency metrics Standardize virtual fencing protocols; integrate sensor/remote sensing data. |

| [41] | Significant learning; herd behavior influenced responses; no activity changes post-stimulus. | Small sample (n=12); no control; short-term focus; sheep-calibrated accelerometers; single breed. | Larger, diverse samples; controls; long-term welfare; cattle-specific sensors; multiple breeds/demographics. |

| [10] | eShepherd VF contained cows ≥99% in inclusion zones but not fully in exclusion zones. EP/audio tone (AT) ratio dropped to 0.18 ± 0.27. Pasture depletion had minimal impact (≤28 sec/hr in exclusion zones). Uniform grazing near VF, unlike dry cows (Lomax et al., 2019). Comparable welfare/energy intake to electric fencing. | Short duration (10 days/treatment); no herd replication; neckband abrasions in dairy cows; excluded grazing-function audio cues. | Longer studies with herd replication; device design improvements; testing in varied terrains. |

| [12] | VF initially matched electric fencing in welfare metrics, but days 4–6 showed reduced activity/grazing and higher cortisol. Early termination due to neckband abrasions. | Small sample (n=30); early termination; cortisol variability; no visual cue testing. | Improved collar design; long-term welfare studies; visual cue integration. |

| [55] | Dairy cattle contained successfully (89% time in inclusion zone). No difference in stimuli between fresh/residual pasture days. Diurnal activity patterns observed near boundaries. | Non-lactating cows used; short restriction period; GPS inaccuracies (8.4m buffer); small sample (n=10); social dynamics not measured. | Include lactating cows; longer restriction periods; improve GPS accuracy; larger samples; assess social interactions. |

| [75] | Digital tools (GPS collars, drones, virtual fences) improved health/behavior monitoring. Virtual fences had mixed welfare outcomes due to individual learning variability. Drones risked stress if flown too close. | Sensor accuracy lacked standardization. GPS errors in dense vegetation. Small/long-term virtual fencing trials. Drone stress data was limited. Connectivity/battery issues in remote areas. | Standardized validation protocols, ethical frameworks for shock use, and adaptive tech for remote pastures. |

| [27] | Cows learned VF boundaries but relied on visual cues (e.g., white tape). Removal of visual cues increased boundary challenges. Reduced grazing/rumination during training suggested stress. | Small sample (n=9); short training; directional ambiguity of audio cues; no social learning analysis; unquantified stress. | Larger/longer studies; improved audio cue directionality; integration of social learning; physiological stress measures. |

| [76] | Group-trained cows relied more on social cues; reduced paired stimuli (45%→14%). | Technical failures; short tests (10min); artificial setting; feed motivation declined. | Improve collar reliability; longer tests; pasture applications; sustained motivation methods. |

| [56] | Virtual fencing (VF) collars effectively contained dairy cows (99% success rate), with reduced stimuli over time (EP:AT ratio dropped from 20% to 12%), indicating learning. However, individual variability was high, and some cows avoided fence zones, suggesting welfare concerns. | Short duration (6 days), no physiological stress measures (e.g., cortisol), non-lactating cows, pasture quality not measured, and proprietary collar algorithms limited transparency. | Longer trials with larger herds, physiological welfare assessments with lactating cows, quantify pasture, and transparent collar specs for reproducibility. |

| [9] | Virtual fencing contained cattle as effectively as electric tape over 4 weeks, with 71.51% of interactions using only audio cues. No difference in fecal cortisol metabolites (stress indicator) between groups. Slightly reduced lying time (<20 min/day) in virtual fence groups (P=0.02) but within normal range. Weight gain differences between cohorts suggest environmental factors influence results. | Short duration (4 weeks); technical malfunctions in neckbands; pasture quality not quantified; small sample size (n=8/group); individual temperament not assessed. | Longer-term studies; improved device reliability; quantify pasture quality; larger sample sizes; assess individual temperament effects. |

| [77] | Fog-enabled WSN with edge mining (IEM) achieved 83–95% activity classification accuracy, reducing cloud dependency. Energy-efficient but performance depended on parameter tuning (γ, ε). Jerky motions reduced accuracy. | Used human (not cattle) acceleration data. Parameter sensitivity required cloud optimization. Limited to binary activity states (e.g., standing/walking). Scalability in large herds untested. | Species-specific algorithm training, on-farm parameter optimization, and broader behavioral classification (e.g., grazing/lameness). |

| [78] | Precision tools (e.g., Grasshopper rising plate meter, PastureBase Ireland) improved pasture management accuracy (r² = 0.99). Virtual fencing enabled dynamic grazing but required GPS reliability. | Limited validation in commercial pastures, GPS dependency, and lack of long-term welfare data. | Wider validation in diverse climates, improved GPS robustness, and cost-effective scaling for small farms. |

| [35] | CID’s cowbell-shaped tracking collar provided real-time grazing and milk yield data, integrating GPS and virtual fencing. | Small trial (n=50), durability claims unverified, reliance on mobile networks. | Larger-scale trials, peer-reviewed durability testing, and alternative data transmission (e.g., LoRaWAN). |

| [69] | Broadcast audio cues (8kHz tones, dog barks) reduced cattle presence near speakers but habituation risks and inconsistent sound levels limited efficacy. Mobile sound delivery may improve consistency. | Stationary speakers caused variable exposure. Small sample (n=24), artificial paddock setup. Uncontrolled variables: age, breed, hearing sensitivity. No long-term habituation data. | Mobile sound systems, field testing in diverse terrains, and integration with wearable devices. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).