Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

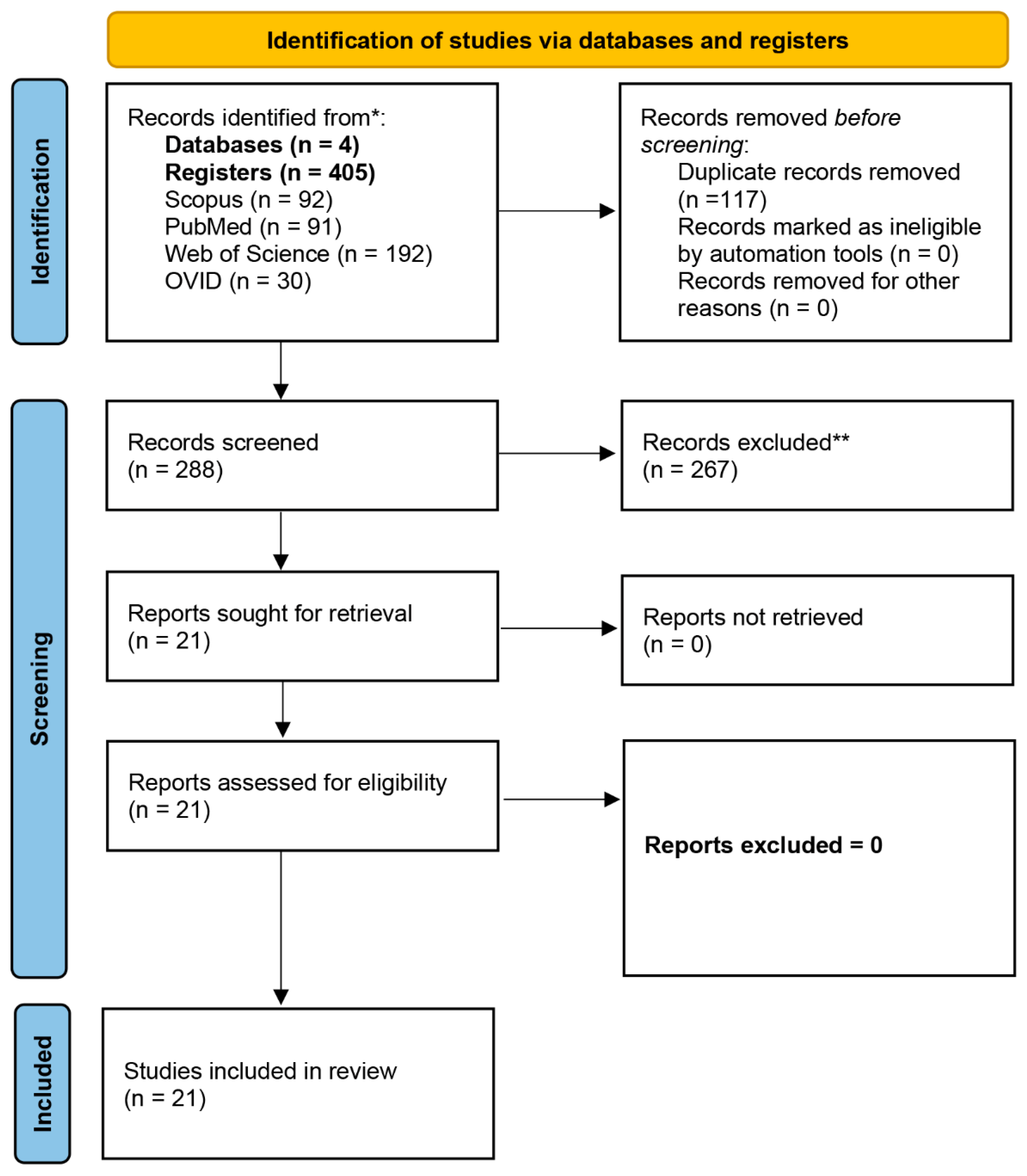

Literature Search and Selection

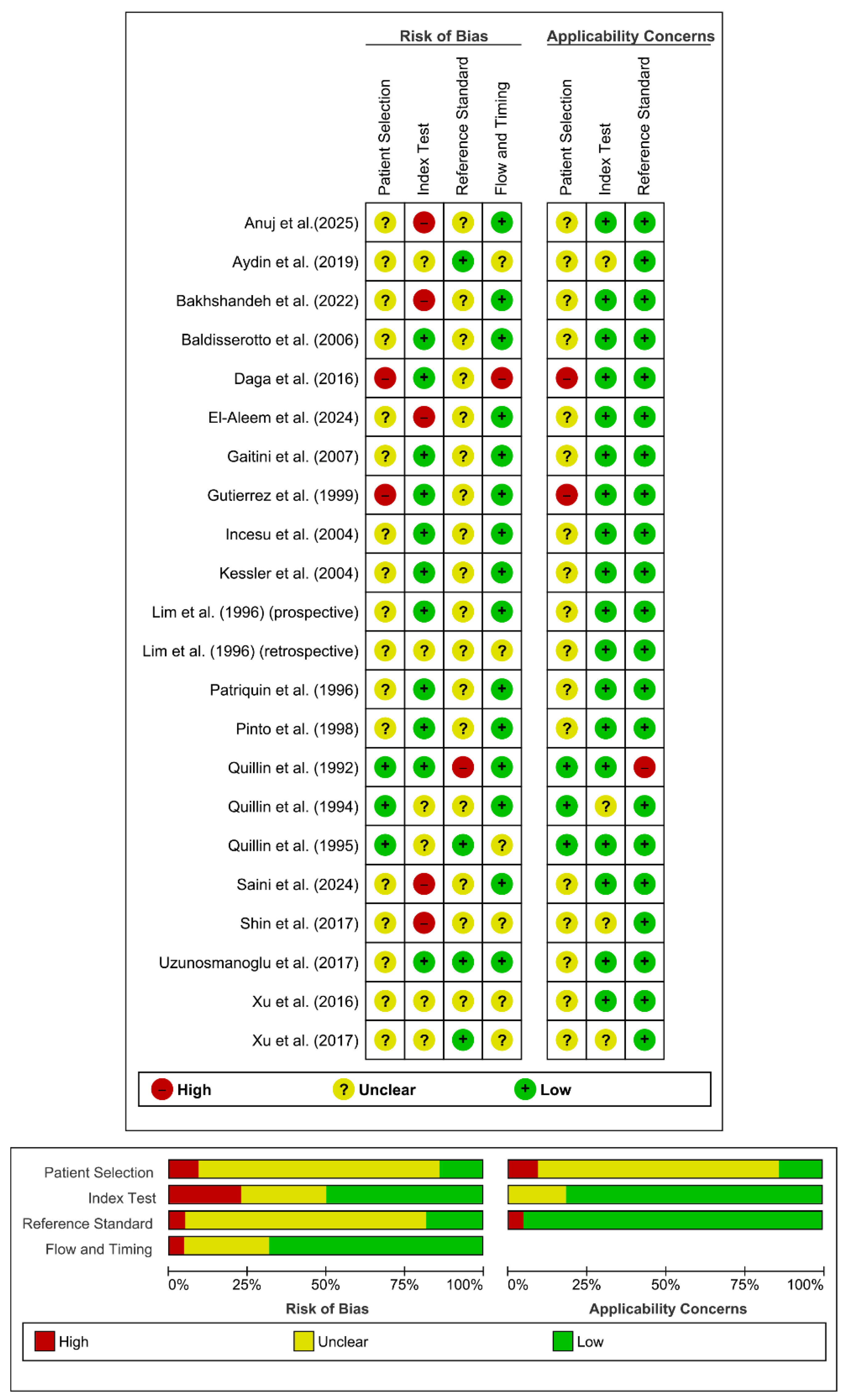

Quality Assessment

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Random-Effects Meta-Analysis

Diagnostic Test Accuracy Meta-analysis

Fagan Nomogram

Publication Bias and Small-Study Effects Assessment

Results

Doppler Ultrasound in Acute Appendicitis

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Overall Doppler Ultrasound Diagnostic Performance in Acute Appendicitis

Exploratory Diagnostic Test Accuracy Meta-Analysis for Overall Doppler Modalities (AA versus CG, Non-Independent)

Spectral Doppler

Spectral Doppler Measurement Units

Diagnostic Performance of Peak Systolic Velocity and Resistive Index (AA Versus CG)

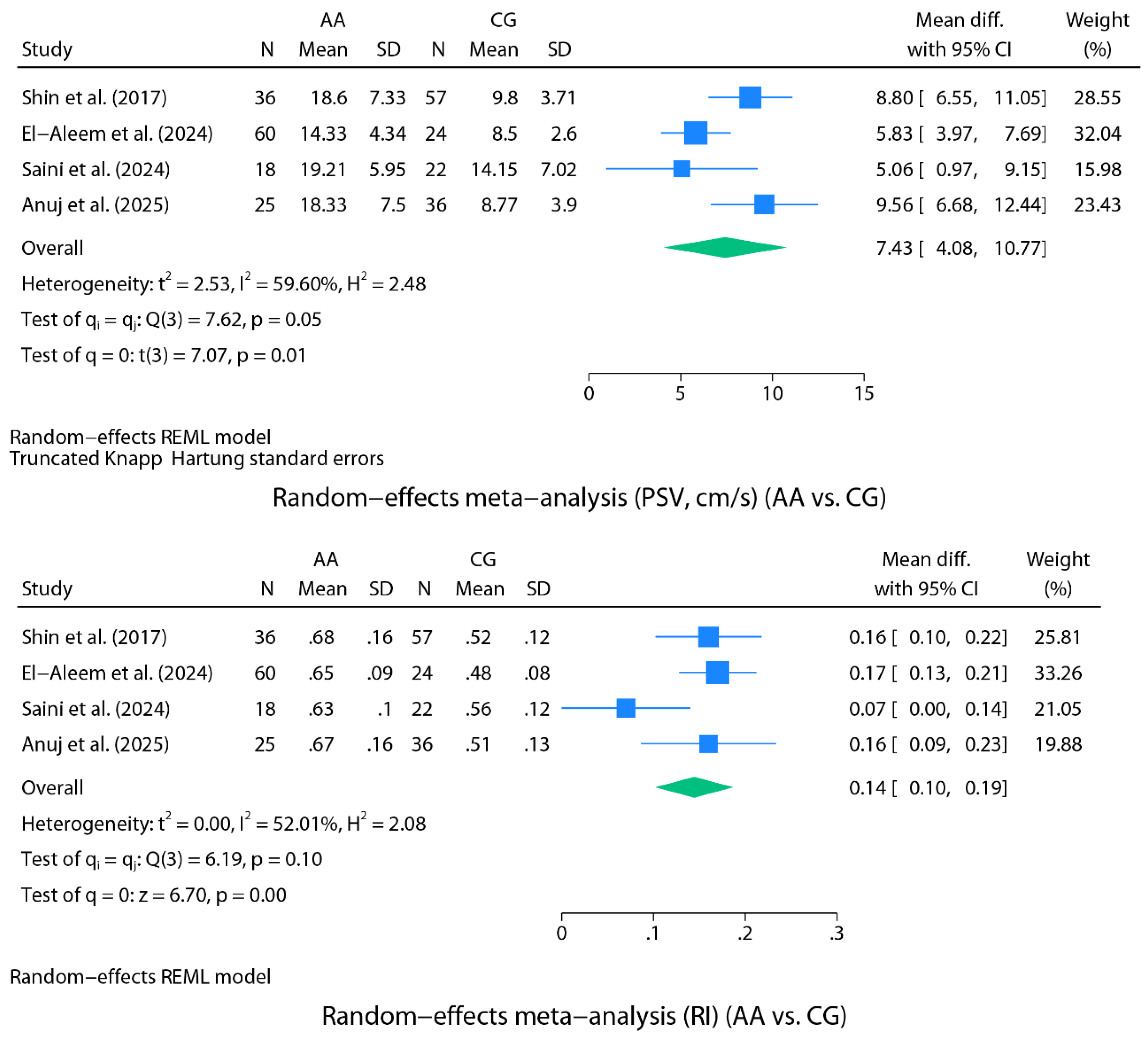

Random-Effects Meta-Analysis for Spectral Doppler (AA Versus CG)

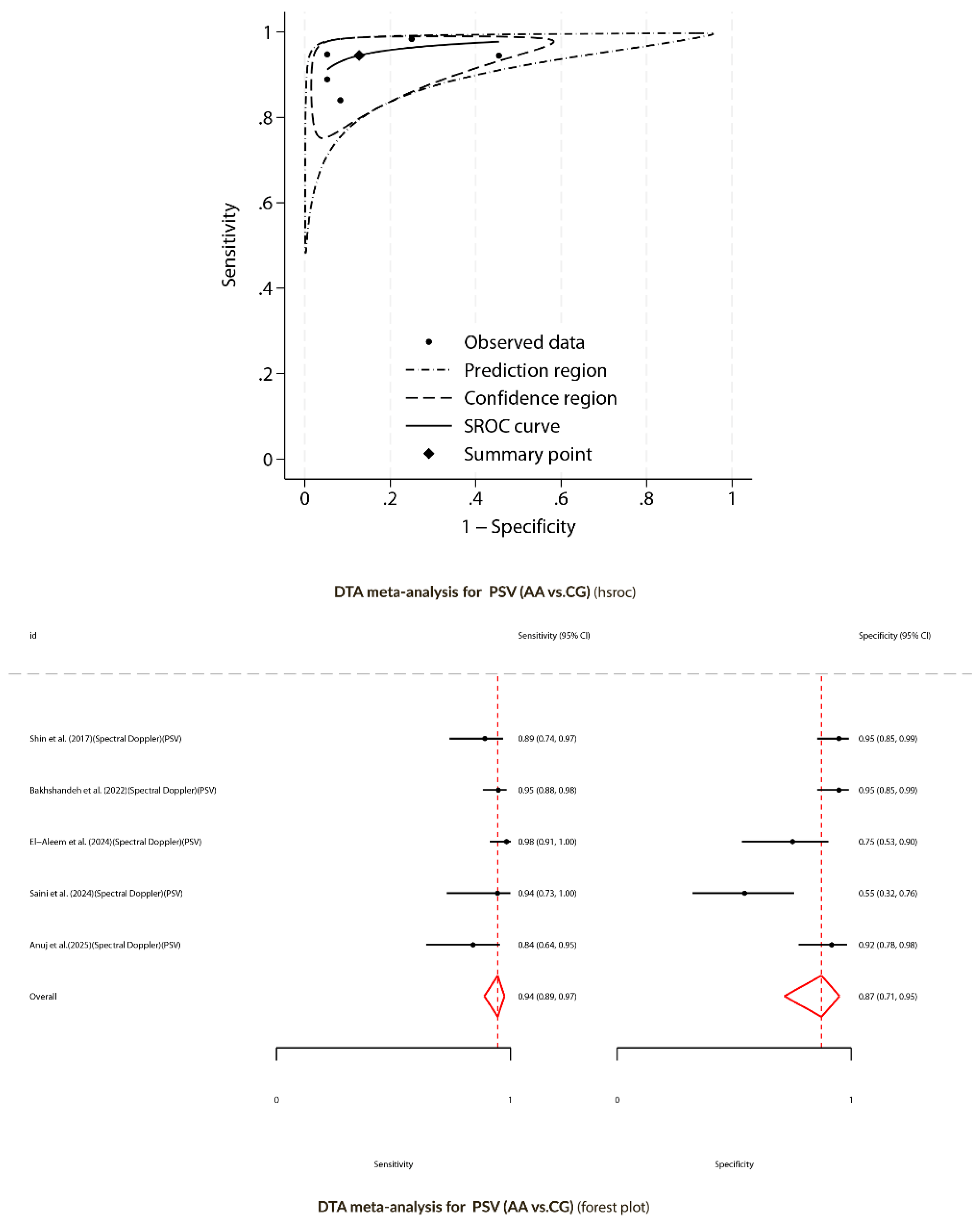

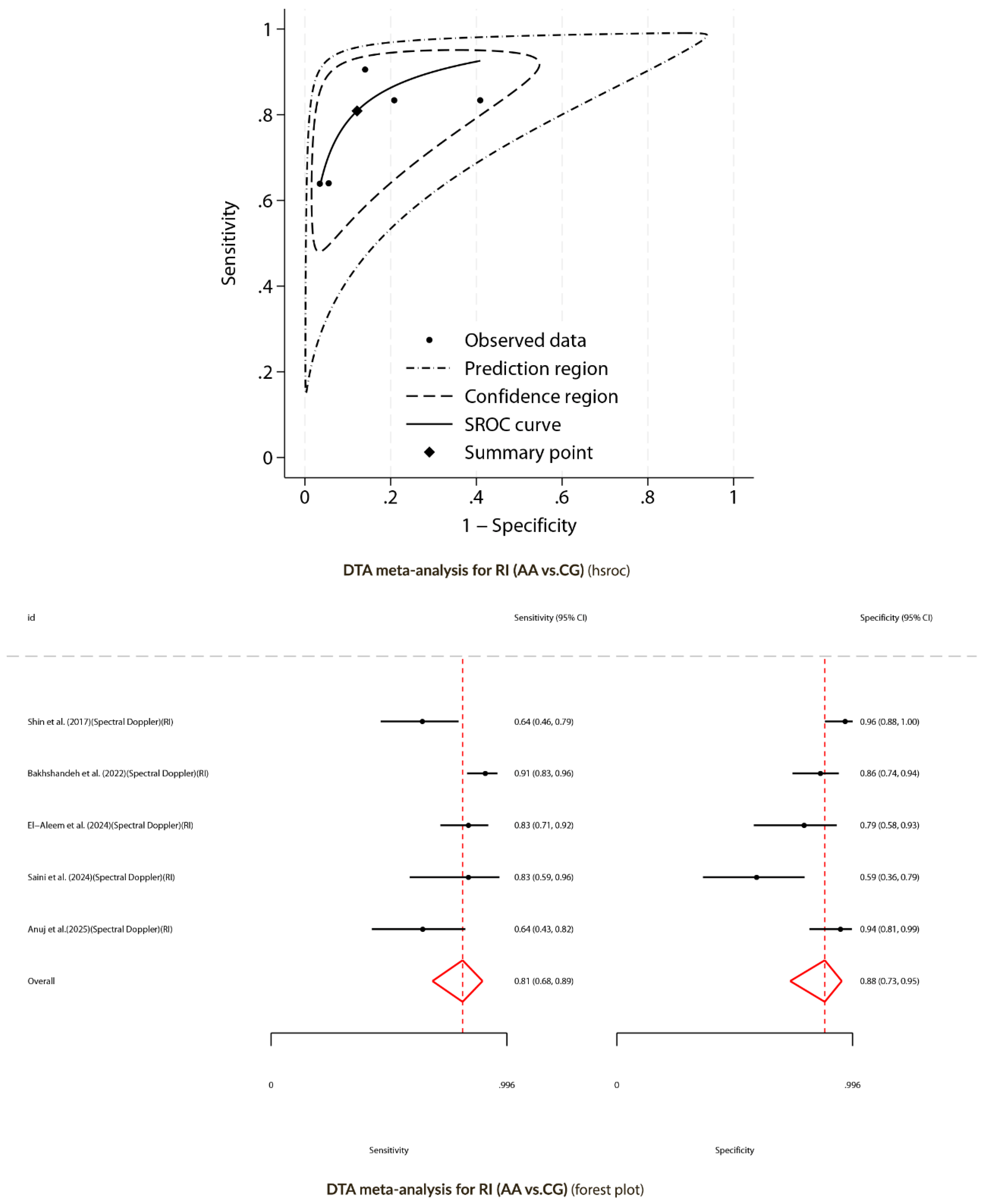

Diagnostic Test Accuracy Meta-Analysis for Spectral Doppler (AA versus CG)

Color Doppler

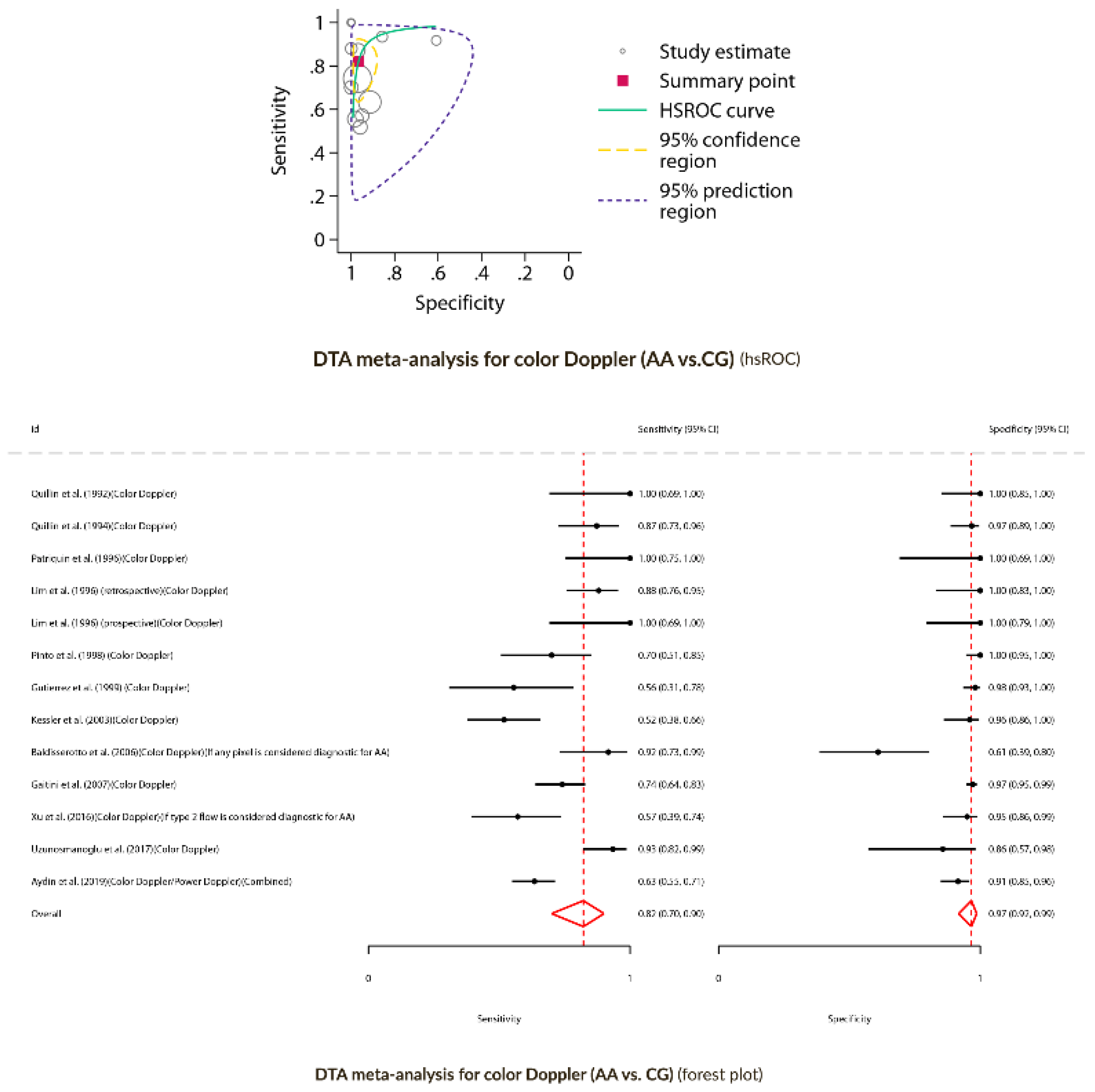

Diagnostic Test Accuracy Meta-Analysis for Color Doppler (AA versus CG)

Power Doppler

Doppler Ultrasound (Complicated Appendicitis versus Non-Complicated Appendicitis)

Diagnostic Performance of Doppler Ultrasound (NCAA versus CAA)

Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Ethical Approval:

Statement of Availability of the Data Used During the Systematic Review

CRediT authorship contribution statement:

Registration

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lotfollahzadeh S, Lopez RA, Deppen JG. Appendicitis. 2024 Feb 12. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. [PubMed]

- Tang G, Zhang L, Xia L, Zhang J, Chen R, Zhou R. Preoperative in-hospital delay increases postoperative morbidity and mortality in patients with acute appendicitis: a meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2025 Jan 1;111(1):1275-1284. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bolmers MDM, de Jonge J, Bom WJ, van Rossem CC, van Geloven AAW, Bemelman WA; Snapshot Appendicitis Collaborative Study group. In-hospital Delay of Appendectomy in Acute, Complicated Appendicitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2022 May;26(5):1063-1069. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Saverio S, Podda M, De Simone B, Ceresoli M, Augustin G, Gori A, Boermeester M, Sartelli M, Coccolini F, Tarasconi A, De’ Angelis N, Weber DG, Tolonen M, Birindelli A, Biffl W, Moore EE, Kelly M, Soreide K, Kashuk J, Ten Broek R, Gomes CA, Sugrue M, Davies RJ, Damaskos D, Leppäniemi A, Kirkpatrick A, Peitzman AB, Fraga GP, Maier RV, Coimbra R, Chiarugi M, Sganga G, Pisanu A, De’ Angelis GL, Tan E, Van Goor H, Pata F, Di Carlo I, Chiara O, Litvin A, Campanile FC, Sakakushev B, Tomadze G, Demetrashvili Z, Latifi R, Abu-Zidan F, Romeo O, Segovia-Lohse H, Baiocchi G, Costa D, Rizoli S, Balogh ZJ, Bendinelli C, Scalea T, Ivatury R, Velmahos G, Andersson R, Kluger Y, Ansaloni L, Catena F. Diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis: 2020 update of the WSES Jerusalem guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2020 Apr 15;15(1):27. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Andersson RE, Stark J. Diagnostic value of the appendicitis inflammatory response (AIR) score. A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Emerg Surg. 2025 Feb 8;20(1):12. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arredondo Montero J, Bardají Pascual C, Antona G, Ros Briones R, López-Andrés N, Martín-Calvo N. The BIDIAP index: a clinical, analytical and ultrasonographic score for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2023 Apr 10;39(1):175. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arruzza E, Milanese S, Li LSK, Dizon J. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography and ultrasound for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiography (Lond). 2022 Nov;28(4):1127-1141. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bom WJ, Bolmers MD, Gans SL, van Rossem CC, van Geloven AAW, Bossuyt PMM, Stoker J, Boermeester MA. Discriminating complicated from uncomplicated appendicitis by ultrasound imaging, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. BJS Open. 2021 Mar 5;5(2):zraa030. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chidiac C, Issa O, Garcia AV, Rhee DS, Slidell MB. Failure to Significantly Reduce Radiation Exposure in Children with Suspected Appendicitis in the United States. J Pediatr Surg. 2024 Aug 22:161701. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza N, Hicks G, Beable R, Higginson A, Rud B. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Dec 14;12(12):CD012028. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim D, Woodham BL, Chen K, Kuganathan V, Edye MB. Rapid MRI Abdomen for Assessment of Clinically Suspected Acute Appendicitis in the General Adult Population: a Systematic Review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2023 Jul;27(7):1473-1485. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Matthew Fields J, Davis J, Alsup C, Bates A, Au A, Adhikari S, Farrell I. Accuracy of Point-of-care Ultrasonography for Diagnosing Acute Appendicitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017 Sep;24(9):1124-1136. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho SU, Oh SK. Accuracy of ultrasound for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in the emergency department: A systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023 Mar 31;102(13):e33397. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harel S, Mallon M, Langston J, Blutstein R, Kassutto Z, Gaughan J. Factors Contributing to Nonvisualization of the Appendix on Ultrasound in Children With Suspected Appendicitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022 Feb 1;38(2):e678-e682. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puylaert JB. Acute appendicitis: US evaluation using graded compression. Radiology. 1986 Feb;158(2):355-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang ST, Jeffrey RB, Olcott EW (2014) Three-step sequential positioning algorithm during sonographic evaluation for appendicitis increases appendiceal visualization rate and reduces CT use. AJR Am J Roentgenol 203(5):1006–1012. [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer CM, Carrejo B, Lewis S, Hutchinson K, Gokli A, Kwon J. Structured coaching as a means to improve sonographic visualization of the appendix: a quality improvement initiative. Emerg Radiol. 2023 Apr;30(2):161-166. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quillin SP, Siegel MJ. Appendicitis in children: color Doppler sonography. Radiology. 1992 Sep;184(3):745-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quillin SP, Siegel MJ. Appendicitis: efficacy of color Doppler sonography. Radiology. 1994 May;191(2):557-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quillin SP, Siegel MJ. Diagnosis of appendiceal abscess in children with acute appendicitis: value of color Doppler sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995 May;164(5):1251-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patriquin HB, Garcier JM, Lafortune M, Yazbeck S, Russo P, Jequier S, Ouimet A, Filiatrault D. Appendicitis in children and young adults: Doppler sonographic-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996 Mar;166(3):629-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim HK, Lee WJ, Kim TH, Namgung S, Lee SJ, Lim JH. Appendicitis: usefulness of color Doppler US. Radiology. 1996 Oct;201(1):221-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, F., Lencioni, R., Falleni, A. et al. Assessment of hyperemia in acute appendicitis: Comparison between power Doppler and color Doppler sonography. Emergency Radiology 5, 92–96 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez CJ, Mariano MC, Faddis DM, Sullivan RR, Wong RS, Lourie DJ, Stain SC. Doppler ultrasound accurately screens patients with appendicitis. Am Surg. 1999 Nov;65(11):1015-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler N, Cyteval C, Gallix B, Lesnik A, Blayac PM, Pujol J, Bruel JM, Taourel P. Appendicitis: evaluation of sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of US, Doppler US, and laboratory findings. Radiology. 2004 Feb;230(2):472-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Incesu L, Yazicioglu AK, Selcuk MB, Ozen N. Contrast-enhanced power Doppler US in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Eur J Radiol. 2004 May;50(2):201-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldisserotto M, Peletti AB. Is colour Doppler sonography a good method to differentiate normal and abnormal appendices in children? Clin Radiol. 2007 Apr;62(4):365-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaitini D, Beck-Razi N, Mor-Yosef D, Fischer D, Ben Itzhak O, Krausz MM, Engel A. Diagnosing acute appendicitis in adults: accuracy of color Doppler sonography and MDCT compared with surgery and clinical follow-up. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008 May;190(5):1300-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu Y, Jeffrey RB, Shin LK, DiMaio MA, Olcott EW. Color Doppler Imaging of the Appendix: Criteria to Improve Specificity for Appendicitis in the Borderline-Size Appendix. J Ultrasound Med. 2016 Oct;35(10):2129-38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daga, Soniya; Kachewar, Sushil; Lakhkar, Dilip L; Jethlia, Kalyani; Itai, Abhijeet. Sonographic evaluation of acute appendicitis and its complications. West African Journal of Radiology 24(2):p 152-156, Jul–Dec 2017. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Jeffrey RB, Chang ST, DiMaio MA, Olcott EW. Sonographic Differentiation of Complicated From Uncomplicated Appendicitis: Implications for Antibiotics-First Therapy. J Ultrasound Med. 2017 Feb;36(2):269-277. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzunosmanoğlu H, Çevik Y, Çorbacıoğlu ŞK, Akıncı E, Buluş H, Ağladıoğlu K. Diagnostic value of appendicular Doppler ultrasonography in acute appendicitis. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2017 May;23(3):188-192. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin LK, Jeffrey RB, Berry GJ, Olcott EW. Spectral Doppler Waveforms for Diagnosis of Appendicitis: Potential Utility of Point Peak Systolic Velocity and Resistive Index Values. Radiology. 2017 Dec;285(3):990-998. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin S, Tek C, Ergun E, Kazci O, Kosar PN. Acute Appendicitis or Lymphoid Hyperplasia: How to Distinguish More Safely? Can Assoc Radiol J. 2019 Nov;70(4):354-360. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhshandeh T, Maleknejad A, Sargolzaie N, Mashhadi A, Zadehmir M. The utility of spectral Doppler evaluation of acute appendicitis. Emerg Radiol. 2022 Apr;29(2):371-375. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Aleem RA, Abd Allah AA, Shehata MR, Seifeldein GS, Hassanein SM. Diagnostic performance of spectral Doppler in acute appendicitis with an equivocal Alvarado score. Emerg Radiol. 2024 Apr;31(2):141-149. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini S, Mittal MK, Kanaujia R et al. (2024) Exploring the role of spectral Doppler in acute appendicitis. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 55:218. [CrossRef]

- Anuj, G., S., R.R., Ashok, Y. et al. Diagnostic Utility of Spectral Doppler Ultrasound in Acute Appendicitis: a Prospective Study. Indian J Surg (2025). [CrossRef]

- McInnes MDF, Moher D, Thombs BD, McGrath TA, Bossuyt PM, and the PRISMA-DTA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies: The PRISMA-DTA Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(4):388–396. [CrossRef]

- Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, Leeflang MM, Sterne JA, Bossuyt PM; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Oct 18;155(8):529-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014 Dec 19;14:135. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hozo, D., Djulbegovic, B., & Hozo, I. (2005). Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 5(1), 13. [CrossRef]

- Šimundić AM. Measures of Diagnostic Accuracy: Basic Definitions. EJIFCC. 2009 Jan 20;19(4):203-11. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nyaga, V.N., Arbyn, M. Metadta: a Stata command for meta-analysis and meta-regression of diagnostic test accuracy data – a tutorial. Arch Public Health 80, 95 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Roger M. Harbord & Penny Whiting, 2009. “metandi: Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy using hierarchical logistic regression,” Stata Journal, StataCorp LP, vol. 9(2), pages 211-229, June. [CrossRef]

- Dwamena BA. MIDAS: Stata module for meta-analytical integration of diagnostic test accuracy studies. Statistical Software Components S456880, Boston College Department of Economics, revised 13 Dec 2009.

- Doebler P, Holling H, Rojas-Garcia A, Hillebrand T (2023). mada: Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy. R package version 0.5.12. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mada.

- Shi L, Lin L. The trim-and-fill method for publication bias: practical guidelines and recommendations based on a large database of meta-analyses. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Jun;98(23):e15987. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deeks JJ, Macaskill P, Irwig L. The performance of tests of publication bias and other sample size effects in systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy was assessed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005 Sep;58(9):882-93. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glas AS, Lijmer JG, Prins MH, Bonsel GJ, Bossuyt PM. The diagnostic odds ratio: a single indicator of test performance. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003 Nov;56(11):1129-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeifer CM, Xie L, Atem FD, Mathew MS, Schiess DM, Messiah SE. Body mass index as a predictor of sonographic visualization of the pediatric appendix. Pediatr Radiol. 2022 Jan;52(1):42-49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller C, Wang NE, Imler DL, Vasanawala SS, Bruzoni M, Quinn JV. Predictors of Nondiagnostic Ultrasound for Appendicitis. J Emerg Med. 2017 Mar;52(3):318-323. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuh S, Man C, Cheng A, Murphy A, Mohanta A, Moineddin R, Tomlinson G, Langer JC, Doria AS. Predictors of non-diagnostic ultrasound scanning in children with suspected appendicitis. J Pediatr. 2011 Jan;158(1):112-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Country | Study design | Population | Age | Sex M/F | Total N | Group definitions | N in AA | N in CG | US Doppler settings | US doppler Diagnostic performance |

Sensitivity (%) Specificity (%) |

Commentaries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quillin et al. (1992) [18] | USA | Prospective (consecutive recruitment) | Pediatric | 11(2-18)y2 | 14/19 | 33 |

IC: Patients with suspected AA AA: AA surgical findings. No histopathological confirmation. CG: NSAP (mesenteric adenitis, hemorrhagic ovarian cyst, viral syndrome, infectious enteritis) + hemorrhagic mesenteric cyst (surgical). Clinical follow-up to exclude AA |

10 CAA:1 NCAA:9 |

23 NSAP:22 Hemorrhagic mesenteric cyst (surgical):1 |

Examiner: PR DUM: CD USP: 5 MHz (linear) Parameters: Bandpass filter: 100 Hz, flow settings: lowest |

TP:10 TN:23 FP:0 FN:0 |

Se:100% Sp:100% |

- |

| Quillin et al. (1994) [19] | USA | Prospective (consecutive recruitment) | Pediatric | 11(1-19)y2 (AA group) |

16/23 (AA group) |

100 |

IC: Patients with suspected AA AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NSAP (gastrointestinal disease, gynecologic disease, renal disease, no abnormalities) with clinical follow-up to exclude AA. NA |

39 NPAA:26 PAA:13 |

61 |

Examiner: PS under PR supervision DUM: CD USP: 5-7.5 MHz (linear) Parameters: Max. power: 500W/Cm2, Gate: 2, Wall filter: 1, scale: 23 cm/sec |

TP:34 TN:59 FP:2 FN:5 |

Se:87% Sp:97% |

The authors present a contingency table comparing the diagnostic performance of gray-scale ultrasound, color Doppler ultrasound, and their combined use. |

| Quillin et al. (1995) [20] | USA | Prospective (consecutive recruitment) | Pediatric | 11(1-19)y2 (AA group) |

19/28 | 47 |

IC: Patients with suspected AA AA: Histopathological confirmation. |

47 NPAA: 27 PAA: 20 |

NS |

Examiner: 2 Blinded experienced radiologists (image review) DUM: CD. USP: 5 or 7.5 MHz (linear). Parameters: Max. power: 500W/Cm2, Gate: 2, Wall filter: 1, scale: 23 cm/sec |

NCAA vs. CAA: Appendiceal hyperemia (favoring NCAA): TP:21b TN:12b FP:8b FN:6b |

NCAA vs. CAA: Appendiceal hyperemia (favoring NCAA): Se:77.8%b Sp:60%b |

Since US is a dynamic examination, retrospective evaluation through static images may constitute a bias. Appendiceal hyperemia was more frequent in NPAA than in PAA, suggesting absence of perforation. |

| Patriquin et al. (1996) [21] | Canada | Prospective | Mixed | HC: 4-25y1 AA: 10(3-25)y2 |

NS | 55 |

AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: HC (2-8 hours of fasting, ultrasound performed for other reasons, i.e., urological) |

30 NCAA: 13 CAA: 11 AA over CA: 3 CrD: 2 Misdiagnosed pregnancy: 1 |

25 (10 with US-appendiceal identification) |

Examiner: Radiologist DUM: CD + SD. USP: 3-5/5/ or 7.5 MHz (linear) Parameters: Low-flow settings: lowest available pulse repetition frequency, highest color doppler gain possible, wall filter: 50 KHz, restricted color window (probably 50 KHz was a mistake from the authors, since the normal range varies between 50 and 800 Hz for CD studies). CD Scale: Number of color doppler signals within the appendiceal wall: absent (0), sparse (1-2), moderate (3-4), or abundant (>4) |

RI (CG): 0.85-11 RI (NCAA): 0.54(0.4-0.77)2 RI (CAA): 0.54(0.33-0.9)2 CD (AA vs. CG): (13 NCAA patients vs. 10 controls with US-appendiceal identification): TP:13b NCAA: Abundant Doppler signal (4) in 13/13 TN:10b CG: No doppler signal (0) in 6/10; sparse doppler signal (1-2) in 4/10. FP:0b FN:0b |

CD: Se:100%b Sp:100%b |

The appendix identification rate in the healthy control (HC) group was very low (10/25), possibly leading to selection bias (spectrum bias). In the AA group, some patients were difficult to classify within the study’s two groups (AA and CG), such as those with CrD or the misdiagnosed pregnancy. This may also represent a potential source of bias. The authors describe for the first time the absence of a Doppler signal at the appendiceal tip in CAA (8 out of 11 cases) |

| Lim et al. (1996)c [22] | South Korea | Retrospective | Mixed | AA: 28(7-72)y2 CG:22(4-62)y2 |

AA: 32/18 CG: 14/6 |

70 |

AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: IBS suspicion patients who underwent barium enema |

50 | 20 |

Examiner: Experienced radiologist DUM: CD + DD + SD USP: 5-10 MHz (linear) Parameters: Wall filter: 100 Hz, low-velocity scale (pulse repetition frequency, 1500 Hz), constant color sensitivity (78%) |

CD: TP:44b TN:20b FP:0b FN:6b |

CD: Se:88%b Sp:100%b |

The six patients classified as FN correspond to six cases of advanced AA (severely necrotic appendix) in which no appendiceal Doppler flow was identified. Patients with non-visualized or partially visualized appendix at barium enema were excluded, which may constitute a selection bias |

| Lim et al. (1996)c [22] | South Korea | Prospective | Mixed | 27(6-56)y2 | 17/9 | 128 (26 with US-appendiceal identification and borderline appendix) |

IC: Patients with suspected AA and borderline US criteria AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NSAP with clinical follow-up/barium enema for excluding AA |

10 | 16 |

Examiner: Experienced radiologist DUM: CD + DD + SD (no RI/PI calculation) USP: 5-10 MHz (linear) Parameters: Wall filter: 100 Hz, low-velocity scale (pulse repetition frequency, 1500 Hz), constant color sensitivity (78%) |

CD: TP:10b TN:16b FP:0b FN:0b |

CD: Se:100%b Sp:100%b |

Of the 126 patients, the cecal appendix was identified by ultrasound in 102. Among these, 26 had borderline criteria (5–7 mm). Since the color Doppler diagnostic performance assessment was limited to this subgroup of patients, a selection bias (spectrum bias) may have been introduced |

| Pinto et al. (1998) [23] | Italy | Prospective (consecutive recruitment) | Mixed | 24.7(7-61)y2 | 46/54 | 100 |

IC: Patients with suspected AA AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NA, NSAP |

34 (30 with US-appendiceal identification) NCAA: 24 CAA (GA+PAA):10 |

NSAP: 62 NA: 4 (CrD: N=1) (Salpingitis: N=2) (Cecal diverticulitis: N=1) |

Examiner: Certified radiologist DUM: CD + PD USP: 3.75 (convex) /7.5 MHz (linear) Parameters: Bandpass filter: 50 Hz, pulse repetition frequency (PRF) 500-750 Hz, Doppler encoded area restriction, color gain adjustment |

CD: TP:21b TN:66b FP:0b FN:9b PD: TP:28b TN:66b FP:0b FN:2b |

CD: Se:70%b Sp:100%b PD: Se:93.3%b Sp:100%b |

The reported diagnostic performance includes only the subgroup of patients with AA in whom the cecal appendix was identified (30/34). Although authors state that there were no FP in either DUM modality (Color and Power), they do not specify how many in CG patients the appendix was identified. A selection bias (spectrum bias) may have been introduced |

| Gutierrez et al. (1999) [24] | USA | Prospective (consecutive recruitment) | Mixed | 32(3-77)y2 | 20/105 | 125 |

IC: Patients with suspected AA (atypical presentation) AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NSAP, Non-appendiceal surgical pathology (foreign body perforation, hemoperitoneum secondary to omental arteritis) + NA |

20 NCAA: 16 PAA: 4 |

105 NSAP: 93 NA: 10 (inferential) Non-appendiceal surgical pathology: 2 |

Examiner: NS DUM: CD USP: 5 MHz Parameters: NS |

TP:10b, o TN:105b, o FP:2b, o FN:8b, o |

Se:55.6%b, o Sp:98.1%b, o |

Patients with atypical presentations of acute appendicitis (AA) were specifically selected, which may have introduced a selection bias (spectrum bias). The cecal appendix was only visualized in 23 out of 125 patients, a particularly low rate, representing a significant limitation of the study. However, the final sample for analysis included the ultrasounds of all 125 patients, and the data on TP, FN, TN, and FP are based on the total cohort. The two false positives were the patients with non-appendiceal surgical pathology. |

| Kessler et al. (2003) [25] | France | Prospective (consecutive recruitment) | Adult | 29.5(15-83)y2 | 58/67 | 125 (104 with US-appendiceal identification)d |

IC: Patients with suspected AA AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NSAP (including non-specific abdominal, mesenteric adenitis, pain, ileitis, gynecologic disease, gastroenteritis, colic pain, psoas hematoma, cystitis, mesenteric ischemia, prostatitis, sigmoid diverticulitis, and gastric ulcer) |

57 (55 with US-appendiceal identification) NPAA: 42 PAA: 15 |

68 (49 with US-appendiceal identification) Non-specific abdominal pain: 26 Mesenteric adenitis: 13 Ileitis or colitis: 9 Gynecologic diseases: 8 Gastroenteritis: 5 Others: 7 |

Examiner: Radiologist with experience in gastrointestinal US examination DUM: CD USP: 4-7 MHz (convex) /5-10 MHz (linear). Parameters: low velocity scale (pulse repetition frequency 1500 Hz, wall filter: 100 Hz) |

TP:28 TN:47 FP:2 FN:26 |

Se:52% Sp:96% |

The reported diagnostic performance is limited to patients in whom the cecal appendix was identified: 55 out of 57 in the AA group and 49 out of 68 in the CG group. A selection bias (spectrum bias) may have been introduced |

| Incesu et al. (2004) [26] | Turkey | Prospective (consecutive recruitment) | Mixed | 4-591 | 36/14 | 50 |

IC: Patients with suspected AA AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NSAP (non-specific abdominal pain, urinary tract infection, inguinal hernia, typhlitis, CrD, mesenteric adenitis) + NA |

35 ASA: 16 PLA: 3 GA: 7 PAA: 9 |

15 (12 with US-appendiceal identification) NSAP: 14 NA: 1 |

Examiner: Radiologist DUM: PD, CEPD USP: 5-10 MHz (multifrequency linear) Parameters: B-mode, parameter optimization (NS) |

RI: ASA: 0.663 PLA: 0.713 GA: 0.923 PAA: 0.793 PD: TP:26 TN:14 FP:1 FN:9 CEPD: TP:35 TN:14 FP:1 FN:0 |

PD: Se:74.3% Sp:93.3% CEPD: Se:100% Sp:93.3% |

All RI comparisons between groups were reported as statistically significant. |

| Baldisserotto et al. (2006) [27] | Brazil | Prospective (consecutive recruitment) | Pediatric | 7.6(2-12)y2 | 31/19 | 50 (47 with US-appendiceal identification) |

IC: Patients with suspected AA AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NSAP + NA |

24 (24 with US-appendiceal identification) NCAA: 18 CAA (GA, PAA): 6 |

26 (23 with US-appendiceal identification) NSAP: 25 NA: 1 |

Examiner: Experienced pediatric radiologists DUM: CD USP: 4-7 MHz (curved) / 5-12 MHz (linear). Parameters: adjusted to optimize detection of low velocity flows. CD Scale: Number of color doppler pixels within the appendiceal wall: absent (0), low (1-2), moderate (3-4), or abundant (>4) |

If 3-4 pixels and >4 pixels are considered diagnostic: TP:15b TN:19b FP:4b FN:9b If any pixel present is considered diagnostic: TP:22b TN:14b FP:9b FN:2b |

If 3-4 pixels and >4 pixels are considered diagnostic: Se: 62.5%b Sp: 82.6%b If any pixel present is considered diagnostic: Se: 91.7%b Sp: 60.9%b |

The reported diagnostic performance includes only the subgroup of patients in whom the cecal appendix was identified (47/50), which may have introduced selection bias. Since these authors use a multicategorical scale to classify Doppler flow, diagnostic performance varies depending on the categories considered. Two possible scenarios were created: 1) considering 3–4 pixels and >4 pixels as pathological, or 2) considering any number of pixels as pathological. When any pixel is considered pathological, sensitivity is high (91.7%), whereas restricting the diagnosis to 3–4 and >4 pixels yields better specificity (82.6%). Overall, the Youden index (J) was higher when the presence of any pixel was considered pathological (J = 0.526), compared to using only 3–4 pixels or >4 pixels as diagnostic criteria (J = 0.451) |

| Gaitini et al. (2007) [28] | Israel | Retrospective (consecutive inclusion) | Adult | 28.4(18-73)y2 | 149/271 | 420 (401 with US-appendiceal identification) |

IC: Patients with suspected AA AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NSAP + Other surgical etiologies + NA |

95 PLA: 84 GA (necrotic): 7 PAA: 4 |

323 NSAP, other medical diagnoses: 316 Other surgical etiologies: 5 NA: 2 |

Examiner: Sonography technician vs radiology resident + confirmation from a senior radiologist DUM: CD USP: 3-5 MHz (convex) / 5-12 vs. 4-8 MHz (linear) Parameters: adjusted to optimize detection of low velocity flows CD Scale: Number of color doppler signals within the appendiceal wall: absent (0), sparse (1-2), moderate (3-4), or abundant (>4) |

CD: TP:66b TN:303b FP:9b FN:23b |

CD: Se: 74.2% Sp: 97.1% |

The reported diagnostic performance study includes only the subgroup of patients in whom the cecal appendix was clearly identified through US (401/420). Seventeen indeterminate cases and two patients with lost reports were excluded from the final analyses. A selection bias (spectrum bias) may have been introduced |

| Xu et al. (2016) [29] | USA | Retrospective | Mixed | 16(2-62)y2 (Data concerning the 94 patients included in the analyses) |

46/48 (Data concerning the 94 patients included in the analyses) |

103 (94 with US-appendiceal identification)e |

IC: Patients with suspected AA whose US showed non-compressible appendices with 6-8 outer diameters. AA: Histopathological confirmation. CG: NSAP (6 weeks follow-up period) + NA |

35 | 59 NSAP: 54 NA: 5 |

Examiner: Experienced sonographers (US performance) + 2 blinded abdominal radiologists (image review) DUM: CD +/- SD (no RI/PI calculation) +/- PD USP: 9-15 MHz Parameters: adjusted to optimize detection of low volume flows. CD Scale: Color Doppler Flow pattern: absent signal (1), type 1 flow (punctate and dispersed signal foci (2), type 2 flow (continuous linear or curvilinear signal extending at least 3 mm in long or short axis view) (3) |

If type 2 flow is considered diagnostic for AA: TP:20 TN:56 FP:3 FN:15 If absent flow is considered diagnostic for not having AA: TP:28 TN:25 FP:10 FN:31 |

If type 2 flow is considered diagnostic for AA: Se: 57.1% Sp: 94.9% If absent flow is considered diagnostic for not having AA: Se: 47.5% Sp: 71.4% |

The reported diagnostic performance study includes only the subgroup of patients in whom the cecal appendix was clearly identified (94/103). A selection bias (spectrum bias) may have been introduced Since US is a dynamic examination, retrospective evaluation through static images may constitute a bias. Discrepancies in CD scale categories were resolved by consensus. The authors limited their sample to patients with an appendix identified on ultrasound and showing borderline characteristics (6–8 mm, non-compressible), which may constitute a selection bias (spectrum bias). The authors report an interobserver agreement kappa value of 0.59 (moderate). This may have been influenced by the study’s methodology (retrospective review of static Doppler images). The Youden index was higher when type 2 flow was considered diagnostic for AA (J = 0.52), compared to absent flow used to rule out AA (J = 0.18), indicating better overall diagnostic performance in the former approach |

| Daga et al. (2017) [30] | India | NS | Mixed | 8-62y1 | NS | 100 (91 with US-appendiceal identification)f |

IC: Patients with a strong suspicion of AA and US criteria for diagnosing AA AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NSAP (6 weeks follow-up period) + NA |

AA: 85 |

15 NSAP: 5 NA: 4 Interval appendectomy (appendicular mass): 4 (inferentially classified in CG group) Drainage of abscess: 2 (inferentially classified in CG group) |

Examiner: NS DUM: CD USP: 3.5-5 MHz (curvilinear) / 7.5-10 MHz (linear) Parameters: NS |

If increased CD flow (hyperemia) is considered diagnostic for AA: TP:64b,f TN:0b,f FP:0b,f FN:21b,f If any CD flow is considered diagnostic for AA: TP:79b,f TN:0b,f FP:0b,f FN:6b,f |

If increased CD flow (hyperemia) is considered diagnostic for AA: Se:NCf Sp:NCf If any CD flow is considered diagnostic for AA: Se:NC%f Sp: NC%f |

Of the 100 patients, the cecal appendix was identified by ultrasound in 90. Among these, 85 had a US AA diagnosis. Since the CD diagnostic performance assessment was limited to this last subgroup of patients, only TP and FP could be calculated. A selection bias (spectrum bias) may have been introduced. The Youden index, Se, and Sp were NC due to insufficient data. |

| Xu et al. (2017) [31] | USA | Retrospective | Mixed | 16.5(3-57)y2 | 64/55 Adults:17/22 Children: 47/33 |

119 |

IC: Patients operated on for AA with histopathologically-proven AA |

119 NCAA: 87 CAA: 32 (GA:11, PAA:21) |

- |

Examiner: Experienced sonographer (retrospective revision by abdominal radiologist) DUM: CD USP: 8-15 MHz (linear) Parameters: NS CD scale: Mural hyperemia was defined as at least 3 mm of contiguous color Doppler flow identified (long or short axis). |

NCAA vs. CAA (Mural hyperemia: 3 mm of contiguous color Doppler flow identified): TP:8 TN:63 FP:24 FN:24 |

NCAA vs. CAA (Mural hyperemia: 3 mm of contiguous color Doppler flow identified): Se: 25%b Sp: 72.4%b |

Since US is a dynamic examination, retrospective evaluation through static images may constitute a bias. The poor diagnostic performance is likely due to the use of mural hyperemia as the diagnostic criterion for complicated acute appendicitis (CAA). Based on biological plausibility and previous literature, this marker should have been applied to non-complicated acute appendicitis (NCAA). The absence of Doppler flow in the appendiceal wall would have been a more appropriate indicator for CAA. |

| Uzunosmanoğlu et al. (2017) [32] | Turkey | Prospective (non-consecutive)g | Adult | 30.3(19-61)y2 | 33/27 | 60h |

IC: Patients operated on for AA AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NA |

AA: 46 NCAA: 25 CAA (PAA): 21 |

NA: 14 |

Examiner: Radiologist DUM: CD + SD USP: 5 MHz (Color and pulse) / 3-9 MHz (electronic phased array) Parameters: NS |

RI (NCAA): 0.783 RI (CAA): 0.813 PI (NCAA): 1.23 PI (CAA): 13 Doppler US: TP:43b TN:12b FP:2b FN:3b |

Doppler US: Se: 93% Sp: 85% |

Since US is a dynamic examination, retrospective evaluation through static images may constitute a bias. The authors state that although they had 21 cases of PAA, they had no cases of GA or necrotic AA |

| Shin et al. (2017) [33] | USA | Retrospective (consecutive) | Mixed | 14.5(1-56)y2 | 53/40 | 337 (93 with US-appendiceal identification and CD on appendiceal wall) |

IC: Patients with suspected AA AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NSAP |

36 | 57 |

Examiner: Experienced radiologist DUM: CD + SD USP: 8-15 MHz (linear) Parameters: adjusted to optimize detection of low volume flows (lowest wall filter value, lowest pulse repetition frequency) |

PSV (cm/s): AA: 19.7(2-33)2 18.6(7.33)5 CG:7.1(4-21)2 9.8(3.71)5 RI AA: 0.69(0.33-1)2 0.68(0.16)5 CG: 0.5(0.24-0.82)2 0.52(0.12)5 PSV TP:32b TN:54b FP:3b FN:4b RI: TP:23b TN:55b FP:2b FN:13b |

PSV ≥ 10 (cm/s) Se:88.9% Sp:94.7% RI ≥ 0.65 Se:63.9% Sp:96.5% |

The authors limited their sample to patients with an appendix identified on ultrasound and a CD signal within the appendiceal wall (93/337), which may constitute a selection bias (spectrum bias). PSV and RI comparisons between groups were statistically significant (p<0.001) |

| Aydin et al. (2019) [34] | Turkey | Retrospective | Mixed | 26(4-78)y2 | 131/128 | 280 (259 with sufficient sonographic information) |

IC: patients who have undergone an appendectomy AA: histopathological confirmation CG: NA (lymphoid hyperplasia) |

142 | NA (lymphoid hyperplasia): 117 |

Examiner: Radiologist DUM: CD + PD USP: 7 MHz (linear) Parameters: NS |

AA (Mural hyperemia: any flow within the appendiceal wall): TP:90b, n TN:107b, n FP:10b, n FN:52b, n |

AA (Mural hyperemia: any flow within the appendiceal wall): Se:63.4% Sp:91.5% |

The retrospective analysis of static images in a dynamic test such as US may introduce bias. The authors limited their sample to patients with adequate sonographic data (259/280), which may lead to spectrum bias. Mural hyperemia was defined as the presence of wall flow on CD or PD. The use of a CG with lymphoid hyperplasia rather than NSAP may also limit the interpretability of the results—particularly given that the reported Se and Sp for grayscale US (appendix >7 mm) were low (63.4% and 77.8%) compared to previous literature. |

| Bakhshandeh et al. (2022) [35] | Iran | Cross sectional | Mixed | 24(12.6)y4 | 82/70 | 152k |

IC: Patients with suspected AA and borderline US AA criteria AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NSAP + NA |

95k | 57k NSAP:?k NA: 57k |

Examiner: Radiologist DUM: CD + SD USP: 7 MHz (linear) Parameters: pulse repetition frequency 1- 1.3 kHz, reduced wall filter |

PSVm: TP:90 TN:54 FP:3 FN:5 RIm: TP:86 TN:49 FP:8 FN:9 |

PSV ≥ 9.6 (cm/s) Se:94.7% Sp:94.7% RI ≥ 0.495 Se:90.5% Sp:86% |

The authors limited their sample to patients with an appendix identified on ultrasound and showing borderline characteristics (6–8 mm), which may constitute a selection bias (spectrum bias). Patients with definite AA on US were also excluded from the study, which may also constitute a selection bias. The numerical values for PSV and RI reported in the manuscript correspond to the entire cohort and are not specific to any subgroups |

| El-Aleem et al. (2024) [36] | Egypt | Prospective | Mixed |

AA: 22.95 (6-43)y2 CG: 17.92 (4-62)y2 |

AA: 36/24 CG: 14/10 |

100 (84 with US-appendiceal identification and with appendiceal CD flow present)i |

IC: Patients with suspected AA and with a visible appendix in grayscale US AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NSAP (6 weeks follow-up period) + NA |

60 | 24 |

Examiner: Senior resident (4y experience) and Abdominal radiology consultant (12y experience) DUM: CD + SD USP: 5 MHz (Curvilinear) / 6-12 MHz (multifrequency linear) Parameters: Lowest wall filter value and pulse repetition frequency |

PSV (cm/s) AA: 14.33(4.34)4 CG: 8.5(2.6)4 RI AA: 0.65(0.09)4 CG:0.48(0.08)4 PSV TP:59b TN:18b FP:6b FN:1b RI: TP:50b TN:19b FP:5b FN:10b |

PSV ≥ 8.6 (cm/s) Se:98.3% Sp:75% RI ≥ 0.58 Se:83.3% Sp:79.2% |

The exclusive inclusion of patients with AA whose appendix was visible on grayscale US and who had CD flow on appendiceal US (84/100) may constitute selection bias (spectrum bias). PSV and RI comparisons between groups were statistically significant (p<0.001) |

| Saini et al. (2024) [37] | India | Prospective | Mixed | 2-50y1 | NS | 40 |

IC: Patients with suspected AA AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NSAP + NA |

18 |

22 NA:3 |

Examiner: Postgraduate radiology resident + Senior radiologist supervision DUM: CD + SD USP: 12 MHz (Linear) Parameters: NS |

PSV (cm/s) AA: 19.21(5.95)4 CG: 14.15(7.02)4 RI AA: 0.63(0.1)4 CG: 0.56 (0.12)4 PSV TP:17b TN:12b FP:10b FN:1b RI: TP:15b TN:13b FP:9b FN:3b |

PSV ≥ 11.8 (cm/s) Se:93.8% Sp:54.2% RI ≥ 0.56 Se: 81.2% 83.3%b Sp: 58.3% 59.1%b |

Patients with complicated AA (PAA, abscess) were excluded from the study, which may represent a selection bias. PSV comparison between groups was statistically significant (p=0.009) RI comparison between groups reached marginal significance (p=0.056) A small difference was found between the sensitivity and specificity reported by the authors and those calculated inferentially based on TP, FP, TN, and FN |

| Anuj et al.(2025) [38] | India | Prospective (consecutive recruitment) | Mixed |

AA: 35(10-60)y2 CG: 34(12-58)y2 |

AA: 15/10 CG: 20/16 |

180 (64 with US-appendiceal identification and with appendiceal doppler data. Finally, the authors included 61 patients)l |

IC: Patients with suspected AA AA: Histopathological confirmation CG: NSAP |

25 | 36 |

Examiner: Experienced radiologists DUM: SD USP: NS Parameters: NS |

PSV (cm/s) AA: 18.9(3-32.5)2 18.33(7.5)5 CG: 6.8(2.5-19)2 8.77(3.9)5 RI AA: 0.68(0.35-0.98)2 0.67(0.16)5 CG: 0.51 (0.22-0.79)2 0.51(0.13)5 PSV TP:21 TN:33 FP:3 FN:4 RI: TP:16 TN:34 FP:2 FN:9 |

PSV ≥ 10 (cm/s) Se:85.3% Sp:92.5% RI ≥ 0.65 Se:64% Sp:95% |

The exclusive inclusion of patients with AA whose appendix was visible on grayscale US and who had CD flow and spectral Doppler waveforms on appendiceal US (61/180) may constitute selection bias (spectrum bias)l PSV and RI comparisons between groups were statistically significant (p<0.001) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).