A Preliminary Study on the Association Between ADHD Symptomatology and Pregnancy Distress: The Mediating Role of Self-Compassion and Self-Criticism

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental condition that is characterised by a persistent pattern of inattention (i.e., an inability to adequately regulate attention, resulting in either a lack of focus or hyperfocus), hyperactivity (e.g., difficulty sitting still for long periods), and impulsivity (e.g., interrupting people when talking) that interferes with an individual’s functioning and development [

1]. In addition to the inattentive, hyperactive and impulsivity symptoms, individuals with this condition can have emotion regulation difficulties including poor management of anger, irritability, and anxiety [

2,

3]. ADHD is a condition found in different regions and cultures and affects approximately 5% of children [

4] and 3% of adults [

5] worldwide. Once considered a childhood disorder, it is now widely recognised that significant symptoms persist into adulthood in most cases [

6,

7], with many people who have clinically significant levels of symptoms in the community remaining undiagnosed [

8], particularly amongst females [

9]. A number of factors have been identified that may contribute to the lower rates of diagnosis in females, including differences in symptom presentation (internalizing symptoms versus externalizing symptoms), the presence of co-morbid disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety) increasing the likelihood of misdiagnosis, and females, relative to males having better coping strategies, and are more able to mask and/or diminish the impacts of their ADHD symptoms. In addition, limited awareness amongst health practitioners regarding the ADHD symptom profile for women contributing to

missed diagnosis or misdiagnosis [

10]. Living with undiagnosed ADHD can have significant adverse impacts on women’s social-emotional wellbeing (e.g., low self-esteem and self-efficacy, maladaptive coping behaviours), their ability to form and maintain personal relationships, and their sense of control over their lives [

11].

The symptoms that characterise ADHD (i.e. inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity) are commonly associated with an impairment in psychosocial functioning across various contexts, including social, academic, and occupational settings. This neurodevelopmental condition also affects an individual’s perception of themselves and their overall well-being [

12,

13]. Individuals with ADHD have a lower tolerance for stress, higher emotional dysregulation, and higher perceived stress levels than those without this neurodevelopmental condition [

14]. Additionally, the condition itself may be considered as a type of stressor for the individual in that the symptoms may expose them to conflict, neglect, or physical and emotional abuse in social, academic and family settings [

15,

16]. Given these aforementioned difficulties and challenges, it is not surprising that ADHD is highly associated with anxiety and depression. Studies have consistently shown that individuals diagnosed with ADHD or who have elevated levels of ADHD symptomatology are at greater risk of experiencing depressive episodes, anxiety, and mood disorders [

17,

18,

19]. The prevalence of depression in individuals with ADHD has been estimated to range from 18.6% to 53.3% [

20,

21]. Similarly, there is high comorbidity between anxiety disorders and ADHD, where the prevalence of any anxiety disorder amongst individuals with this condition has been estimated to be 47.1% [

18]. For women with ADHD, there is increased vulnerability for generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) such that they have four times the odds of experiencing GAD [

22]. Given the increased risk for mood disorders and psychological distress within this population, it is important to examine whether levels of ADHD symptomatology are associated with anxiety and depression during significant life-events in women’s lives such as pregnancy which involve significant biopsychosocial changes that may contribute to women experiencing pregnancy as a stressful life event..

The Effect of ADHD Symptomatology on Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes

Research examining pregnancy and birth complications among women with ADHD is an emerging research area with few studies conducted examining this issue. Walsh et al. [

23] found that except for HPV infection, mothers with ADHD (relative to mothers without ADHD) had higher rates of every birth complication. Different symptom clusters (i.e., inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity) have been reported to affect prenatal health behaviours and influence major life domains. Although all three domains of ADHD symptoms showed significant associations with prenatal health behaviours, there were also behavioural variations in each domain [

24]. For example, inattention has been associated with poor eating, physical strain, and depression. In contrast, hyperactivity was associated with smoking, increased caffeine consumption, reduced vitamin intake, physical strain, and depression [

24]. In addition, ADHD symptoms have been reported to be associated with impairments in major life domains, such that inattentive symptoms significantly predict impairment in relationships, daily life, and professional life domains [

25]. Similarly, impulsivity has been reported to be associated with impairment in the professional and personal life domains [

25]. Based on the findings of their systematic review on the association of maternal ADHD with pregnancy and birth outcomes, Kittel-Schneider et al. [

26] proposed that inattention is the most critical predictor of impairment in the daily life of mothers with ADHD, which could potentially negatively affect pregnancy health-related behaviours (e.g., making decisions about health, impulsive spending, and poor financial management). Researchers have therefore recommended the need to prioritise the monitoring for high ADHD symptomatology in pregnant women [

23,

25,

26].

Self-Compassion as a Mediator in the Mental Health of People with ADHD Symptoms

Self-compassion, the ability to treat oneself with kindness, understanding, and acceptance during challenging times, consists of three interconnected dimensions of self-compassion (i.e., supportive and understanding toward oneself rather than self-critical), common humanity (i.e., recognition that everyone experiences suffering and imperfections, promoting a sense of connection), and mindfulness (i.e., non-judgmental awareness of thoughts and emotions [

38,

39]. While these components of self-compassion are distinct, they are interconnected and mutually reinforcing, fostering self-care, and reducing self-criticism. [

39,

40] The negative counterpart to self-compassion is self-criticism, which involves persistent critical self-evaluations and negative reactions to perceived failures, is comprised of self-judgement (i.e., a judgmental and hostile attitude toward one’s difficult experiences), isolation (i.e., views failures as unique to self), and over-identification (i.e., overidentifies to negative experiences and apply it globally) [

38,

41]. Examinaton of the factor structure of the Self-Compassion Scale (a commonly used measure for self-compassion) indicate that self-compassion and self-criticism are distinct dimensions that need to be considered separately [

39,

40].

The symptoms that characterise ADHD can lead to difficulties in developing effective planning, life management and coping skills [

42], predisposing the individual to experience a range of difficulties [

12,

13] and negative life experiences [

15,

16]. Over time, the succession of difficulties can undermine their self-concept and result in them becoming more negative and self-critical of themselves [

44] (i.e., lower levels of self-compassion and higher levels of self-criticism). The negative environment resulting from failure and stress can also contribute to mental health difficulties, making it harder for individuals with ADHD to manage their well-being [

43,

44].

It is, therefore, unsurprising that individuals with ADHD (relative to individuals without ADHD) have been demonstrated to exhibit lower self-compassion, higher self-criticism and poorer mental health outcomes [

12]. In a study conducted by Beaton and colleagues [

43] , they found that higher levels of ADHD symptomatology were significantly associated with higher levels of depression, anxiety and stress, and that this association was partially explained by lower levels of self-compassion [

43]. In this study, self-compassion was treated as a composite of both compassionate and uncompassionate self-responding. In contrast, Farmer and colleagues [

44] in their study of the association between ADHD symptomatology and mental health indicators examined self-compassion separately from self-criticism. They found that higher levels of ADHD symptomatology were associated with higher levels of self-criticism. However, self-compassion did not significantly vary according to ADHD symptomatology. This finding reinforces previous evidence indicating the distinctiveness of self-compassion from self-criticism and the importance of considering these dimensions separately [

39,

40]. Consistent with previous research, Farmer and colleagues found that higher ADHD symptomatology was associated with higher levels of psychological distress and lower wellbeing. Self-criticism was found to partially mediate the association between ADHD symptomatology and psychological distress and fully mediate the association between ADHD symptomatology and well-being.

Self-compassion has consistently been associated with reduced depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms [

45,

46] and is increasingly being proposed as a protective factor against life stressors and mental health concerns. For example, Neff and McGehee [

47] found that self-compassion was strongly associated with well-being and partially mediated the relationship between well-being and factors known to promote positive psychological health. Based on these findings, they proposed that self-compassion may provide a means to learn new ways of relating to oneself and others that are more balanced and supportive, as well as ways of coping with the difficulties and challenges that are encountered in one’s life. Consequently, the shared aim of self-compassion intervention approaches is to reduce uncompassionate self-responding (e.g., self-criticism and self-judgement) by cultivating compassionate self-responding [

48].

In light of the global relevance of ADHD, the higher likelihood of women with ADHD being underdiagnosed or undiagnosed and therefore not receiving treatment, as well as the scarcity of research examining the psychological wellbeing of pregnant women with ADHD symptomatology, there is a need for research aimed at understanding the relationship between ADHD symptomatology and psychological wellbeing during pregnancy, and the potential factors that can influence or contribute to psychological distress. Self-compassion may be the mechanism which protects expectant mothers with ADHD symptomatology from developing psychological distress while navigating through pregnancy. Self-compassion may protect well-being by reducing the impact of stressors (i.e., the difficulties associated with ADHD and pregnancy) on the individual. In contrast, self-criticism may increase negative feelings towards themselves and negative emotions. Expectant mothers with ADHD symptomatology are also more likely to have emotional regulation difficulties due to the ADHD condition, and their pregnancy (e.g., hormonal shifts and physical changes). Therefore, self-criticism may increase the risk for psychological distress in these women. Research examining the psychological wellbeing of pregnant women with ADHD symptomatology is needed to inform screening, treatment and educational campaigns for both health practitioners and the public.

The Current Study

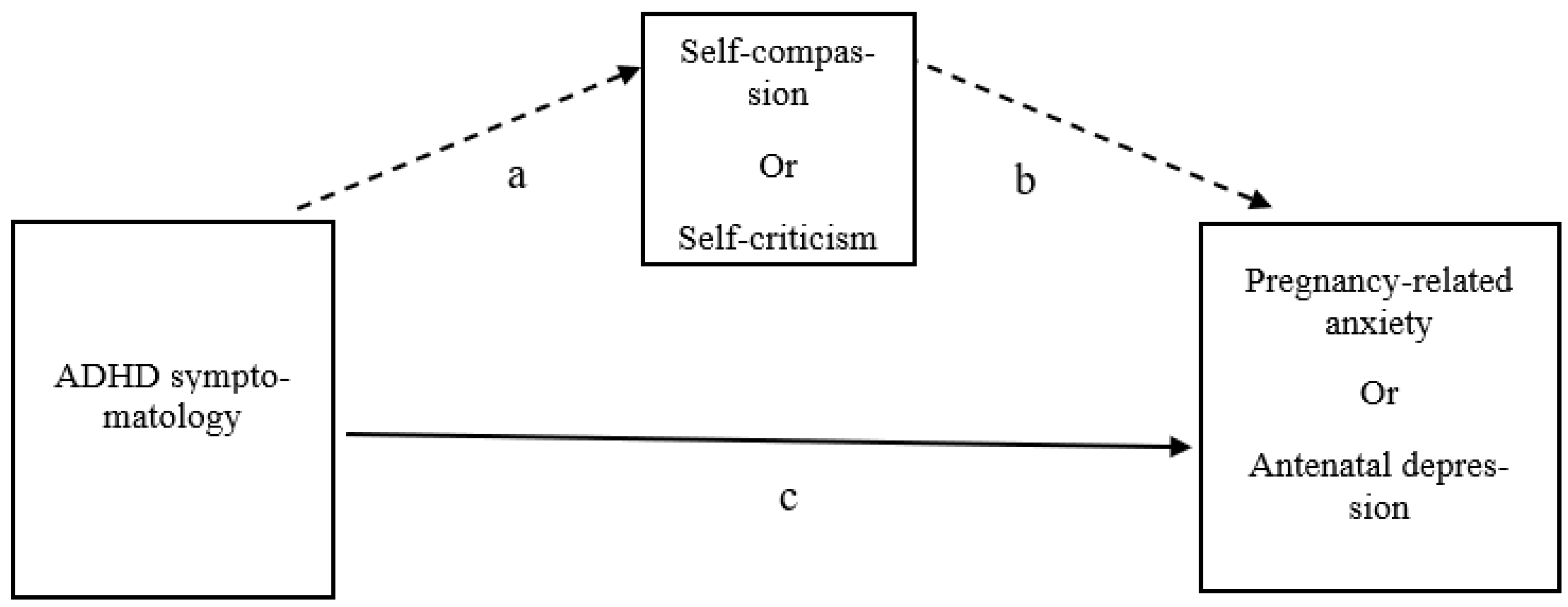

This cross-sectional study examined the relationship between ADHD symptoms and psychological distress (i.e., pregnancy-related anxiety and antenatal depression) in a community sample of pregnant women. Due to the rate of undiagnosed ADHD in adult women with clinically significant ADHD symptomatology [

49], this study examined ADHD symptomatology as falling on a continuum from very low levels to very high levels. Given the evidence indicating that self-compassion and self-criticism are distinct dimensions that need to be considered separately [

39,

40,

44,

50] this study examined self-compassion separately from self-criticism. This study examined whether higher levels of ADHD symptomatology was associated with higher levels of psychological distress (i.e., pregnancy-related anxiety and antenatal depression), and whether self-compassion (and self-criticism) mediated this relationship (see

Figure 1).

Method

Participants

Three hundred and sixty-five pregnant women aged 18 to 41 years responded to the online advertisements. As per human research ethics requirements, women who were identified as having a high-risk pregnancy, pregnant via In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF) or had previously experienced a miscarriage or stillbirth within the last two years were excluded from participating. Moreover, women were informed that they could withdraw their participation if they got distressed by the questions by closing their web browser at any time before completion of the online questionnaire. A large number of participants who logged into the online questionnaire (

N = 222) were excluded because they did not meet eligibility requirements (i.e., they indicated they were aged younger than 18 years, not pregnant, and/or had high-risk pregnancy, and/or pregnant by IVF, and/or experienced miscarriage/stillbirth within the previous two years), did not provide informed consent, or had failed to complete one or more of the measures suggesting that they were withdrawing their participation in the study. A final sample size of 143 participants (

Mage 30.91,

SDage = 4.83, range 19-41 years) was included in the data analyses. As shown in

Table 1, participants were predominantly born in Australia and the United Kingdom, married or cohabitating, had completed tertiary education, and did not have an official diagnosis of ADHD, or currently using medication for ADHD. Approximately half of the participants (52.1%) indicated that they had received a mental health diagnosis in the past. Approximately half of the women (51.8%) had given birth more than once (i.e., multiparous).

Materials

Pregnancy-related anxiety: The Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Scale (PrAS) [

51] is a 32-item self-report measure used to assess participants' specific fears and worries about themselves and their unborn babies. It examines eight facets of pregnancy-related anxiety (Childbirth Concerns, Body Image Concerns, Attitudes towards Childbirth, Worry about Self, Baby Concerns, Acceptance of Pregnancy, Avoidance and Attitudes toward Medical Staff. Items (e.g.,

I fear I may be harmed during the birth) are rated on a four-point response scale (1 = ‘

Not at All’, 4 = ‘

Very Often’), with higher scores indicating higher levels of pregnancy-related anxiety. The PrAS has demonstrated good internal reliability (α

’s ranging from .80 to .93) and good validity [

51]. In the current study, the PrAS demonstrated excellent internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α = .94). Total scores were used in the data analyses.

Antenatal depression: The Edinburg Perinatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [

52] is a 10-item self-report questionnaire used to screen depression and anxiety in pregnant women to identify mothers at risk for prenatal and postnatal depression [

53]. Items (e.g.,

I have been so unhappy that I have had difficulty sleeping) are rated on a four-point Likert-type scale (0 = ‘

No, not at all’, 3 = ‘

Yes, all the time’). Higher scores indicate higher depressive symptoms. The EPDS has demonstrated good internal consistency (α

’s ranging from .80 to .90) and validity[

55]. In this study, the EPDS demonstrated good internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α = .91). Total scores were used in the data analyses.

Self-compassion and self-criticism: The Self-Compassion Scale- Short Form (SCS-SF) [

54] is a 12-item self-report measure used to measure both self-compassion (i.e., Self-Kindness, Common Humanity, and Mindfulness) and self-criticism (i.e., Self-judgement, Isolation, and Over-identification). Both Self-compassion (e.g.,

When I’m going through a very hard time, I give myself the caring and tenderness I need) and Self-criticism items (e.g.,

I’m disapproving and judgmental about my own flaws and inadequacies) are rated on a five-point response scale (1 = ‘

Almost Never’, 5 = ‘

Almost Always’), with higher scores on each dimension indicating greater self-compassion or self-criticism. The SCSC-SF has been demonstrated to have good internal consistency reliability (α = .85) [

55] . The current study demonstrated good internal consistency reliability with a full-scale (Cronbach’s α of .89) and for each subscale (Self-Compassion α = .88, Self-Criticism α= .86). Total scores were used in the data analyses.

ADHD symptomatology: The Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale-v1.1 Symptom Checklist (ASRS)[

56] is an 18-item checklist that corresponding to the 18 symptoms found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) [

57]. Items (e.g.,

How often do you have difficulty concentrating on what people say to you, even when they are speaking to you directly?) are rated on a five-point response scale (‘

Never’, ‘

Very Often’). Higher scores indicate higher ADHD symptoms and symptom burden [

58]. The ASRS has demonstrated high internal consistency reliability (α

’s ranging from .88 to .89) and validity [

58]. In the current study, the ASRS demonstrated excellent internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α = .94). Total scores were used in the data analyses.

Demographic information: Participants were asked to provide information pertaining to their age, parity, gestational weeks, employment status, level of education, marital status, geographical location, ADHD diagnosis, and whether they had previously been diagnosed with a mental health condition.

Procedure

Following institutional human research ethics approval, recruitment of participants proceeded through boosted Facebook/Meta postings of the study which included a link to the online study (hosted on the Qualtrics platform). The online questionnaire presented participants with the participant information sheet and consent form. Participants who provided confirmation of informed consent were directed to the online questionnaire which commenced with questions to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria for the study followed by demographic questions. Participants were then presented with the target measures in a randomised order to address any potential order effects. Following the completion of the online questionnaire, participants were provided with debriefing information which included details of support services. Participants residing in Australia had the option of opting in for a small incentive encouraged participation (i.e., option to enter a draw to win one of four AUD 40 gift cards). This incentive was not made available to participants residing outside of Australia due to restrictions in funding and purchasing comparable gift cards for international use.

Data Analysis Strategy

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 28). Cronbach’s α assessed internal consistency reliability of the measures. Hayes PROCESS Macro version 4.2 (Model 4) was used to conduct the mediation analyses as illustrated in

Figure 1. Four mediation models were conducted, one for each psychological distress indicator and SCS-SF sub-scale. ADHD symptomatology (ASRS) was the predictor for all of the mediation models, with pregnancy-related anxiety (PrAS) or postnatal depression (EPDS) as the out-come variables. Self-compassion or self-criticism was the mediator variables in these models.

Results

Preliminary Data Analysis

The assumptions of univariate normality were examined by reviewing descriptive statistics, specifically seeking skewness values <|2| and kurtosis values <|7| [

59]. Significant negative skew was observed for SCF-SF Self-Criticism subscale. Univariate outliers were identified through visual inspection of histograms, box plots, normality probability plots, and by computing standard z-scores, with the criterion for identifying outliers as values exceeding ±3.29 [

60]. To assess multivariate normality, a visual examination was conducted by inspecting a Q_Q plot of Mahalanobis distances in relation to a chi-square distribution with five degrees of freedom, employing a significance level of p<.001. Three data points were identified as potential outliers on the self-criticism subscale. However, the outliers did not significantly change the model relationships nor the assumptions to a significant level. Therefore, these outliers were not removed from the main data analyses. Spearman’s Rho correlations (see

Table 2) confirmed that multicollinearity was not a concern [

61]. To examine the possibility that the incentives provided to Australian residents only may have influenced participation, we examined whether there were any differences in age, gestational weeks, and parity between Australian participants and participants from other countries. No significant differences were observed.

Correlational Analysis

Due to significant skew in the data (i.e., SCF-SF Self-Criticism subscale), Spearman’s Rho correlation was used to examine the degree of association between the variables and to identify potential variables that needed to be included as covariates in the mediation analyses. Note that the categorical variables of marital status, education and employment status were not included in the correlation analyses. As shown in

Table 2, participant age had a positive correlation with SCS-SF Self-Compassion score and was negatively correlated with the PrAS (pregnancy-related anxiety) and the EPDS (antenatal depression) scores. Self-reported previous mental health diagnosis (Yes = 1, No = 0) was positively correlated with the ASRS (ADHD symptomatology), SCS-SF Self-Criticism and the PrAS. Not surprisingly, self-reported pre-existing diagnosis of ADHD (Yes = 1, No = 0) had a positive correlation with ASRS but was not significantly correlated with the other target measures. Given these findings, only age and previous mental health diagnosis were entered as covariates in the mediation analyses.

SCS-SF Self-compassion was negatively correlated with SCS-SF Self-criticism, PrAS and EPDS. Conversely, SCS-SF Self-criticism had positive correlations with PrAS and EPDS. ASRS was positively correlated with both the PrAS and EPDS scores. Finally, PrAS and EPDS were positively correlated.

Discussion

This study examined whether ADHD symptomatology was associated with indicators of psychological distress (i.e., pregnancy-related anxiety and antenatal depression) in pregnant women. We also examined whether self-compassion or self-criticism mediated this relationship. This study found that ADHD symptomatology was associated with both pregnancy-related anxiety and antenatal depression, which confirm the findings reported in previous research that higher levels of ADHD symptomatology is associated with have higher levels of anxiety and depression symptoms [

36]. Moreover, this study found that higher levels of ADHD symptomatology were associated with lower levels of self-compassion and higher levels of self-criticism. This finding is consistent with those reported by Beaton et al., [

12,

42] who found that ADHD diagnosis, was significantly associated with lower levels of self-compassion, and lower levels of psychological, emotional and social psychological wellbeing.

Similar to Beaton et al., [

43] who reported that self-compassion partially mediated the relationship between ADHD diagnosis and increased ill-health (i.e., depression, anxiety and stress), the current study found that amongst expectant mothers, self-compassion partially mediated the relationship between ADHD symptomatology and pregnancy-related anxiety and antenatal depression. This finding provides further evidence to indicate that low self-compassion contributes to poorer mental health amongst individuals with ADHD, and suggests that nurturing self-compassion may serve as a valuable strategy to mitigate the risk of psychological distress in pregnant women with ADHD symptoms. It is worth noting that a recent systematic review [

63] found evidence to indicate that self-compassion practices can aid pregnant women in their transition to motherhood by mitigating psychological challenges. Self-compassion focused therapeutic approaches may be particularly beneficial for women with ADHD symptomatology who are struggling through their pregnancy.

The current study extends the findings of Beaton et al.’s study [

43] by examining the construct of self-criticism separately to that of self-compassion. This approach is consistent with the one adopted in Farmer et al.’s study [

44]. However, in contrast to Farmer et al.’s study who used a composite measure of psychological distress, this study examined anxiety separately from depression. This study found that self-criticism partially mediated the relationship between ADHD symptomatology and pregnancy-related anxiety but fully mediated the relationship between ADHD symptomatology and antenatal depression. In other words, it is only via self-criticism that pregnant women’s ADHD symptomatology is associated with antenatal depression, which is consistent with accumulating evidence that self-criticism is a transdiagnostic vulnerability risk factor for a range of adverse mental health outcomes [

64]. Beaton et al., [

43] have argued that individuals with ADHD (relative to individuals without this condition) receive more criticism and negative judgement from others, as a consequence of the ADHD symptoms. Given that individuals with ADHD see the condition as an integral part of themselves and their personality, they are more likely to internalise the negativity from others, which in turn contributes to them feeling less compassionate and more critical towards themselves. Further research is needed to understand whether this mediational indirect effect of self-criticism can be moderated by self-compassion in pregnant women with ADHD symptomatology. That is, in the indirect pathway between ADHD symptomatology and antenatal depression (via self-criticism), whether self-compassion focused intervention can influence the strength of association between self-criticism and antenatal depression. This is particularly important given that women with pre-existing depression symptoms are more likely to develop a self-critical way of thinking [

65]. For pregnant women with ADHD symptomatology who, due to their early life experiences may be prone to self-critical ways of thinking, they may be caught in a vicious cycle where their antenatal depression may further contribute to their critical self-evaluation and self-judgement. Moreover, given that self-compassion and self-efficacy have consistently been demonstrated to be positively associated [

66], future studies are needed to understand how low self-compassion and high self-criticism impacts on maternal self-efficacy which is a predictor of sensitive and responsive caregiving.

The findings of this study indicate that health practitioners may need to consider incorporating strategies aimed at fostering self-compassion and reducing self-criticism in their support for expectant mothers with ADHD symptoms. Furthermore, there is a need to increase awareness amongst health practitioners and general public of the potential psychological challenges faced by pregnant women with ADHD symptomatology. By acknowledging the unique stressors that women with ADHD symptomatology may encounter, healthcare providers can tailor their care to meet the specific needs of these expectant mothers. Creating educational campaigns targeted at the general population to raise awareness of ADHD in adult women may help increase awareness of their condition and encourage them to seek additional support when facing challenges during pregnancy, rather than waiting until they reach a point of overwhelming distress. Health practitioners need to be cognizant of screening for ADHD symptomatology in pregnant women given the higher likelihood of women with ADHD being misdiagnosed or not diagnosed with this condition, particularly if there is co-morbid depression and anxiety [

9,

10].

Limitations

The findings of the current study should be considered in light of several methodological limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of the study means that the directionality between the variables need to be replicated in future prospective and/or longitudinal studies. Another limitation was the reliance on self-report measures (i.e., possibility of response bias). To minimize this risk, the measures were presented in a randomized order. The social media recruitment strategy may also have introduced a self-selection bias, in that it may have attracted women with a specific interest in this topic, potentially making the sample less representative of the broader population of pregnant women with ADHD symptomatology. The small sample size also limited our ability to examine the influence of other socio-demographic variables (e.g., education and employment status) and restricts the generalizability of the findings to the wider population of women with ADHD symptomatology. Moreover, it is also worth noting that while statistically significant, the effect sizes reported were small, and therefore the findings of this study should be regarded as preliminary that need to be confirmed in future studies. One of the difficulties in conducting research in this area is the recruitment of large numbers amongst this population. Women with ADHD symptomatology are likely to be experiencing difficulties managing and navigating their pregnancies and may therefore feel less able to participate in research, regardless of whether there are incentives for participation. The nature of the sample (i.e., women from English speaking countries with a tertiary education) would have further impacted on the generalizability of the findings to non-English speaking women and women with lower levels of education. Despite these limitations, this study addressed a gap in the literature in regard to the association between ADHD symptomatology and psychological distress during pregnancy.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this research provides valuable insights into the associations between ADHD symptomatology, self-compassion, and pregnancy-related distress. It highlights the potential of self-compassion as a protective factor against developing pregnancy-related anxiety and antenatal depression in pregnant women with ADHD symptomatology. Simultaneously, it highlights the potential contributing role of self-criticism in developing pregnancy-related anxiety and antenatal depression. These findings carry implications for antenatal health support for pregnant women with ADHD symptomatology, suggesting the possible need for additional screening for ADHD during antenatal care delivery and avenues for intervention to enhance their mental health well-being during pregnancy.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, Rachel Dryer; Investigation, Tinette Mella; Writing – original draft, Tinette Mella; Writing – review & editing, Rachel Dryer; Supervision, Rachel Dryer. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, project was supported by an Australian Catholic University Honours/Masters project support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author, as per Australian Catholic University Human Research Ethics Committee requirements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association issuing body. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5-TR, 5th edition, text revision; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Michelini, G.; Kitsune, V.; Vainieri, I.; Hosang, G.M.; Brandeis, D.; Asherson, P.; et al. Shared and disorder-specific event-related brain oscillatory markers of attentional dysfunction in ADHD and bipolar disorder. Brain Topography. 2018, 31, 672–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, C.A.; Rommelse, N.; van der Klugt, C.L.; Wanders, R.B.K.; Timmerman, M.E. Stress exposure and the course of ADHD from childhood to young adulthood: Comorbid severe emotion dysregulation or mood and anxiety problems. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019, 8, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayal, K.; Prasad, V.; Daley, D.; Ford, T.; Coghill, D. ADHD in children and young people: prevalence, care pathways, and service provision. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2018, 5, 175–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Winterstein, A.G. Prevalence of ADHD in publicly insured adults. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2018, 22, 182–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederman, J.; Petty, C.R.; Evans, M.; Small, J.; Faraone, S.V. How persistent is ADHD? A controlled 10-year follow-up study of boys with ADHD. Psychiatry Research. 2010, 177, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, V.; Czobor, P.; Bálint, S.; Mészáros, Á.; Bitter, I. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009, 194, 204–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, Y.; Quintero, J.; Anand, E.; Casillas, M.; Upadhyaya, H.P. Underdiagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adult patients: a review of the literature. Primary care companion for CNS disorders 2014, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klefsjö, U.; Kantzer, A.K.; Gillberg, C.; Billstedt, E. The road to diagnosis and treatment in girls and boys with ADHD - gender differences in the diagnostic process. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2021, 75, 301–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, P.O.; Madhoo, M. A review of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in women and girls: uncovering this hidden diagnosis. Primary care companion for CNS disorders 2014, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attoe, D. E.; Climie, E. A. Miss. Diagnosis: A systematic review of ADHD in adult women. Journal of Attention Disorders 2023, 27, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.M.; Sirois, F.; Milne, E. Self-compassion and perceived criticism in adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Mindfulness. 2020, 11, 2506–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraone, S.V.; Bellgrove, M.A.; Brikell, I.; Cortese, S.; Hartman, C.A.; Hollis, C.; et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Primer). Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2024, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combs, M.A.; Canu, W.H.; Broman-Fulks, J.J.; Rocheleau, C.A.; Nieman, D.C. Perceived stress and ADHD symptoms in adults. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2015, 19, 425–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, A.; Agnew-Blais, J.; Danese, A.; Fisher, H.L.; Jaffee, S.R.; Matthews, T.; et al. Associations between abuse/neglect and ADHD from childhood to young adulthood: A prospective nationally-representative twin study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2018, 81, 274–85. [Google Scholar]

- Sari Gokten, E.; Saday Duman, N.; Soylu, N.; Uzun, M.E. Effects of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2016, 62, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Asherson, P.; Buitelaar, J.; Faraone, S.V.; Rohde, L.A. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: key conceptual issues. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016, 3, 568–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrichs, B.; Igl, W.; Larsson, H.; Larsson, J.O. Coexisting psychiatric problems and stressful life events in adults with symptoms of ADHD—A large Swedish population-based study of twins. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2012, 16, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahmurova, A.; Arikan, S.; Gursesli, M.C.; Duradoni, M. ADHD symptoms as a stressor leading to depressive symptoms among university students: The mediating role of perceived stress between ADHD and depression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022, 19, 11091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Adler, L.; Barkley, R.; Biederman, J.; Conners, C.K.; Demler, O.; et al. The Prevalence and Correlates of Adult ADHD in the United States: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006, 163, 716–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgersen, T.; Gjervan, B.; Rasmussen, K. ADHD in adults: A study of clinical characteristics, impairment and comorbidity. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2006, 60, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller-Thomson, E.; Carrique, L.; MacNeil, A. Generalized anxiety disorder among adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2022, 299, 707–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, C.J.; Rosenberg, S.L.; Hale, E.W. Obstetric complications in mothers with ADHD. Frontiers in Reproductive Health. 2022, 4, 1040824–1040824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, H.A.; Eddy, L.D.; Rabinovitch, A.E.; Snipes, D.J.; Wilson, S.A.; Parks, A.M.; et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom clusters differentially predict prenatal health behaviors in pregnant women. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2018, 74, 665–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddy, L.D.; Jones, H.A.; Snipes, D.; Karjane, N.; Svikis, D. Associations between ADHD symptoms and occupational, interpersonal, and daily life impairments among pregnant women. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2019, 23, 976–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittel-Schneider, S.; Quednow, B.B.; Leutritz, A.L.; McNeill, R.V.; Reif, A. Parental ADHD in pregnancy and the postpartum period – a systematic review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2021, 124, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, B.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Broadbent, J.; Skouteris, H. The meaning of body image experiences during the perinatal period: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. Body Image. 2015, 14, 102–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryer, R.; Brunton, R. Pregnancy-related anxiety : Theory, research, and practice. Abingdon, Oxon; Routledge; 2022.

- Yin, X.; Sun, N.; Jiang, N.; Xu, X.; Gan, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. Prevalence and associated factors of antenatal depression: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review. 2021, 83, 101932–101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.L.; Falah-Hassani, K.; Shiri, R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2017, 210, 315–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrampour, H.; Ali, E.; McNeil, D.A.; Benzies, K.; MacQueen, G.; Tough, S. Pregnancy-related anxiety: A concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2016, 55, 115–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryer, R.; Brunton, R.; Krägeloh, C.; Medvedev, O. Screening for pregnancy-related anxiety: Evaluation of the Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Scale–Screener using Rasch methodology. Assessment. 2023, 30, 1407–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poikkeus, P.; Saisto, T.; Unkila-Kallio, L.; Punamaki, R. L. , Repokari, L., Vilska, S..; et al. Fear of childbirth and pregnancy-related anxiety in women conceiving with assisted reproduction. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006, 108, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, E.; Grace, S.; Wallington, T.; Stewart, D.E. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2004, 26, 289–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelkowitz, P.; Papageorgiou, A. Easing maternal anxiety: An update. Women’s Health. 2012, 8, 205–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninowski, J.E.; Mash, E.J.; Benzies, K.M. Symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in first-time expectant women: Relations with parenting cognitions and behaviors. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2007, 28, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.; Johnston, C. Parenting in mothers with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006, 115, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. Self-Compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity. 2003, 2, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, R.E.; Heath, P.J.; Vogel, D.L.; Credé, M. Two is more valid than one: Examining the factor structure of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2017, 64, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleare, S.; Gumley, A.; Cleare, C.J.; O’Connor, R.C. An investigation of the factor structure of the Self-Compassion Scale. Mindfulness. 2018, 9, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löw, C.A.; Schauenburg, H.; Dinger, U. Self-criticism and psychotherapy outcome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2020, 75, 101808–101808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langberg, J.M.; Epstein, J.N.; Graham, A.J. Organisational-skills interventions in the treatment of ADHD. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2008, 8, 1549–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.M.; Sirois, F.; Milne, E. The role of self-compassion in the mental health of adults with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2022, 78, 2497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, G.M.; Ohan, J.L.; Finlay-Jones, A.L.; Bayliss, D.M. Well-being and distress in university students with ADHD traits: The mediating roles of self-compassion and emotion regulation difficulties. Mindfulnness. 2022, 14, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Feng, Y.; Xu, S.; Wilson, A.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; et al. Appearance anxiety and social anxiety: A mediated model of self-compassion. Frontiers In Public Health. 2023, 11, 1105428–1105428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, M.; Loi, N.M. The mediating role of self-compassion in student psychological health. Australian Psychologist. 2016, 51, 431–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D.; McGehee, P. Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self and identity. 2010, 9, 225–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. Self-compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annual Review of Psychology. 2023, 74, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinshaw, S.P.; Nguyen, P.T.; O’Grady, S.M.; Rosenthal, E.A. Annual Research Review: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in girls and women: underrepresentation, longitudinal processes, and key directions. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry. 2022, 63, 484–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muris, P.; Petrocchi, N. Protection or vulnerability? A meta-analysis of the relations between the positive and negative components of self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2017, 24(2), 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, R.J.; Dryer, R.; Krägeloh, C.; Saliba, A.; Kohlhoff, J.; Medvedev, O. The pregnancy-related anxiety scale: A validity examination using Rasch analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018, 236, 127–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Holden, J.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987, 150, 782–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, H.M.; Draisma, S.; Honig, A. Construct Validity and Responsiveness of Instruments Measuring Depression and Anxiety in Pregnancy: A Comparison of EPDS, HADS-A and CES-D. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022, 19, 7563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raes, F.; Pommier, E.; Neff, K.D.; Van Gucht, D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2011, 18, 250–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, J.A.; Lockard, A.J.; Janis, R.A.; Locke, B.D. Construct validity of the Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form among psychotherapy clients. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2016, 29, 405–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Adler, L.; Ames, M.; Demler, O.; Faraone, S.; Hiripi, E.; et al. The World Health Organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychological Medicine. 2005, 35, 245–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association, issuing body. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSMIV-TR (4th edition, text revision.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2000.

- Adler, L.A.; Faraone, S.V.; Sarocco, P.; Atkins, N.; Khachatryan, A. Establishing US norms for the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1) and characterising symptom burden among adults with self-reported ADHD. International Journal of Clinical Practice (Esher). 2019, 73, e13260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmider, E.; Ziegler, M.; Danay, E.; Beyer, L.; Bühner, M. Is it really robust? Reinvestigating the robustness of ANOVA against violations of the normal distribution assumption. Methodology. 2010, 6, 147–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using multivariate statistics, Seventh edition; Pearson, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A.P. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics, 6th ed.; Sage, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis : a regression-based approach; Guilford Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, S.; Dickson, C. Women’s experiences of transition to motherhood and self-compassion. Journal of Family and Child Health. 2024, 1, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, A.M.; Tibubos, A.N.; Rohrmann, S.; Reiss, N. The clinical trait self-criticism and its relation to psychopathology: A systematic review – Update. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2019, 246, 530–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beato, A.F.; Albuquerque, S.; Kömürcü Akik, B.; Costa, L.P.D.; Salvador, Á. Do maternal self-criticism and symptoms of postpartum depression and anxiety mediate the effect of history of depression and anxiety symptoms on mother-infant bonding? Parallel-serial mediation models. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022, 13, 858356–858356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filisetti, A.C.; Ferreira, I.M.F.; Neufeld, C.M. The relationship between self-efficacy and self- compassion: An integrative systematic review of the literature. Revista Brasileira de Terapias Cognitivas. 2023, 19, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).