Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Concept of a Classification Tree

1.2. Phases in the Construction of a Classification Tree

1.3. Use of Classification Trees in Medicine

1.4. Types of Classification Trees

1.5. Advantages and Disadvantages of Classification Trees

- -

- Can handle all variable types (continuous, ordinal, categorical)

- -

- Easy to interpret, with clinically meaningful decision rules

- -

- No additional calculations required to determine individual patient risk

- -

- Perform variable selection and establish variable hierarchy

- -

- Identify optimal cut-off points for continuous variables

- -

- Detect relationships among variables without assuming independence

- -

- Less affected by outliers or missing values

- -

- Risk of overfitting and limited generalizability

- -

- High sensitivity to data, leading to model instability

- -

- Complex trees may lose interpretability

- -

- Require specific software and development methodology

- -

- Many CT types exist, and the most suitable one for a specific problem may not be obvious in advance

2. ENPIC Study and the Obesity Paradox

2.1. The ENPIC Study

2.2. The Obesity Paradox

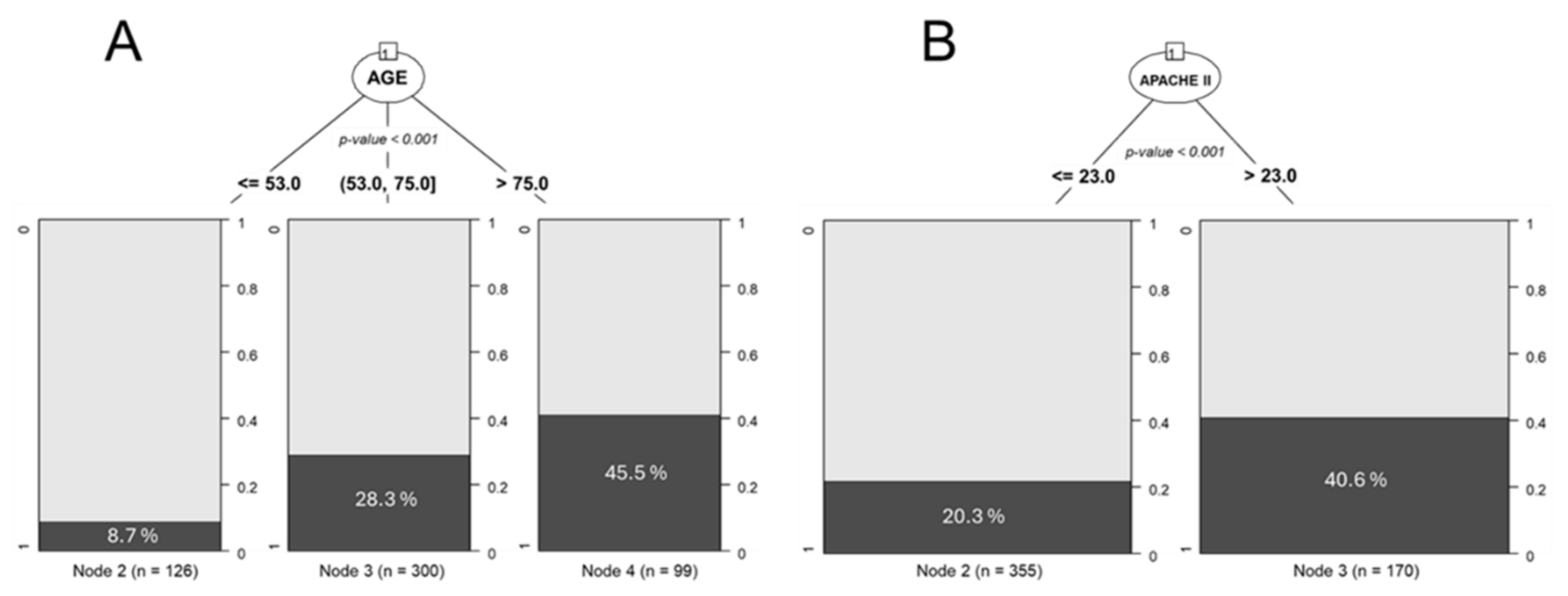

3. Use of Classification Trees to Determine Cut-off Points

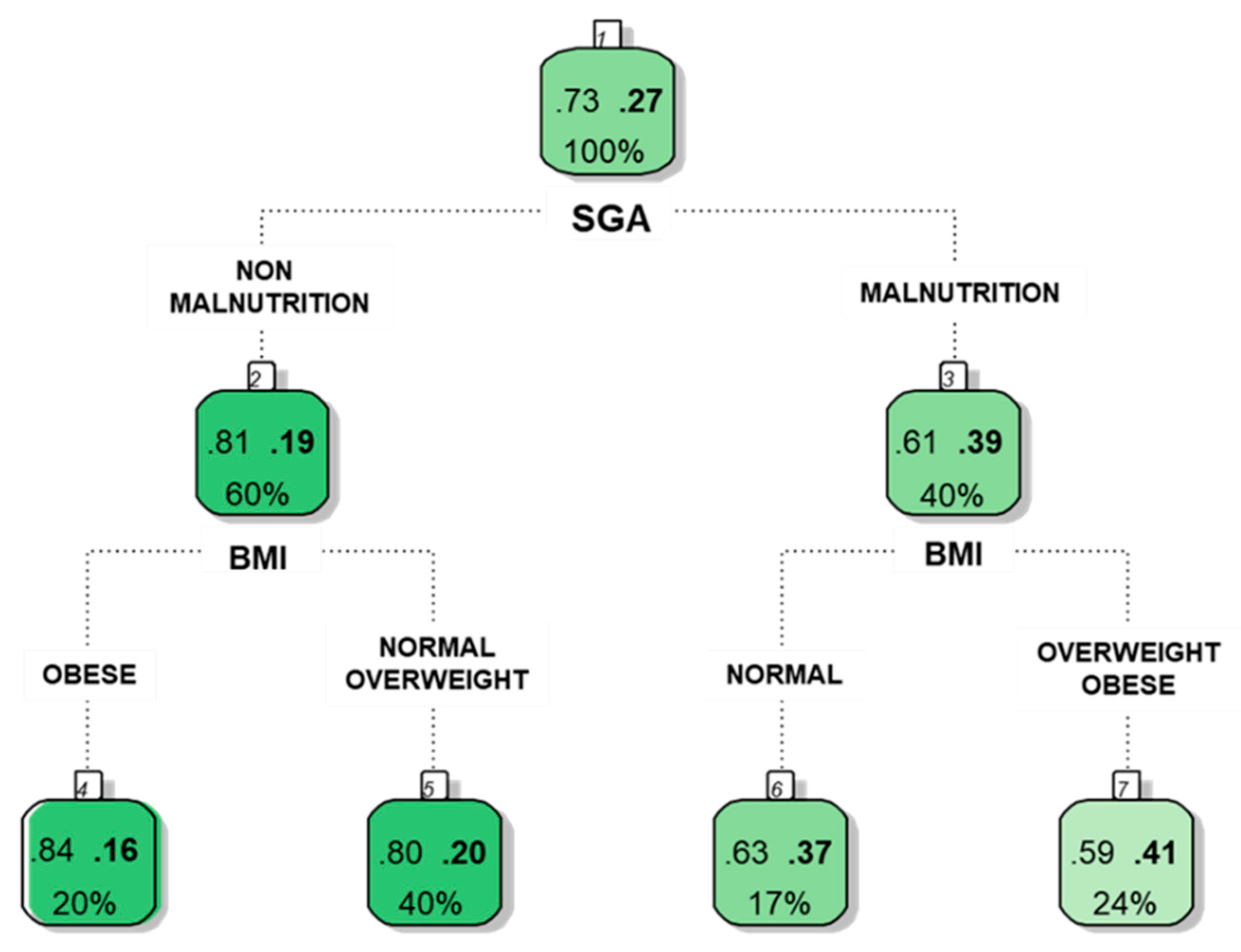

4. Use of Classification Trees to Identify Relationships Between Variables

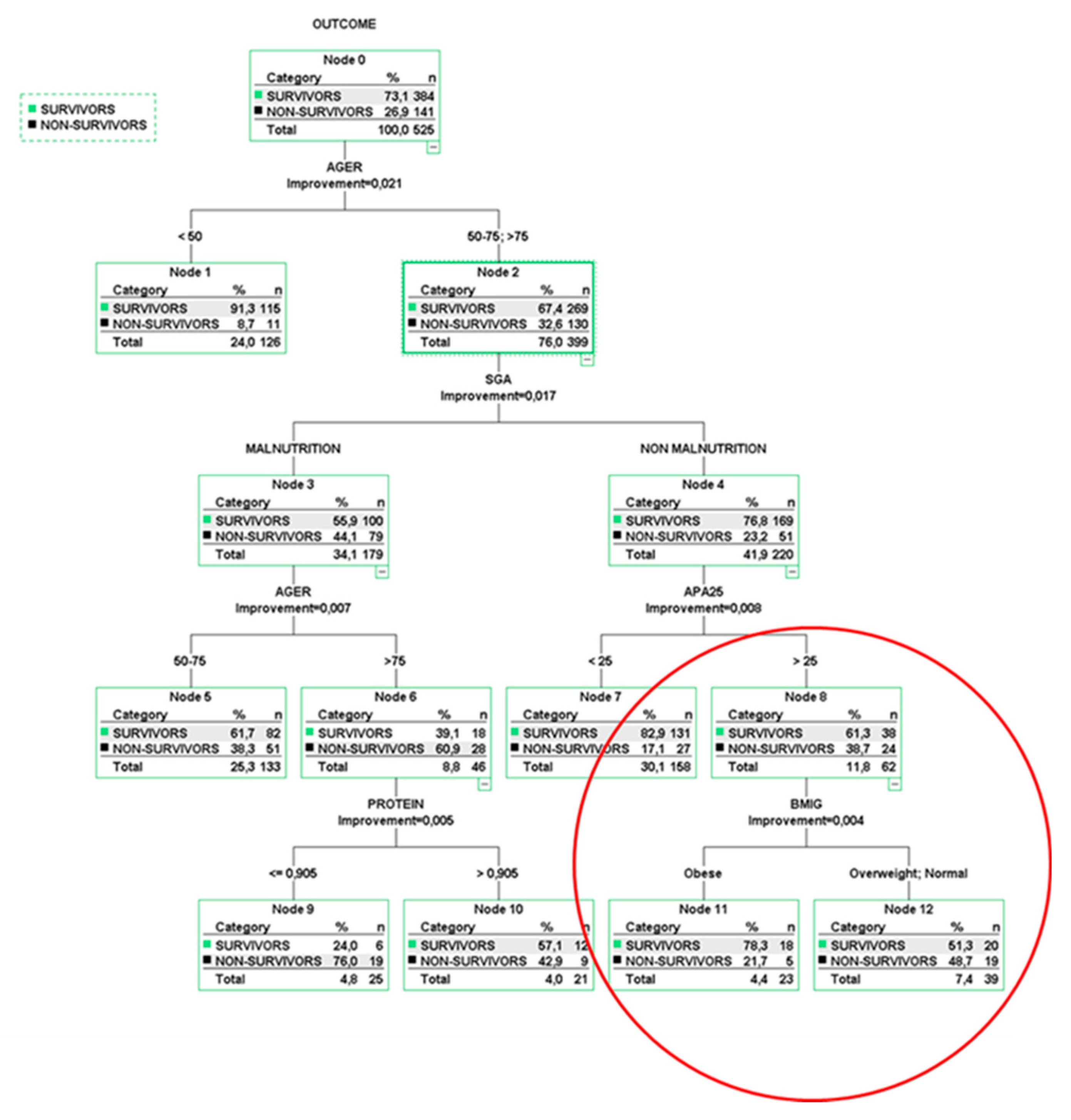

5. Multivariable Risk Models Using Classification Trees

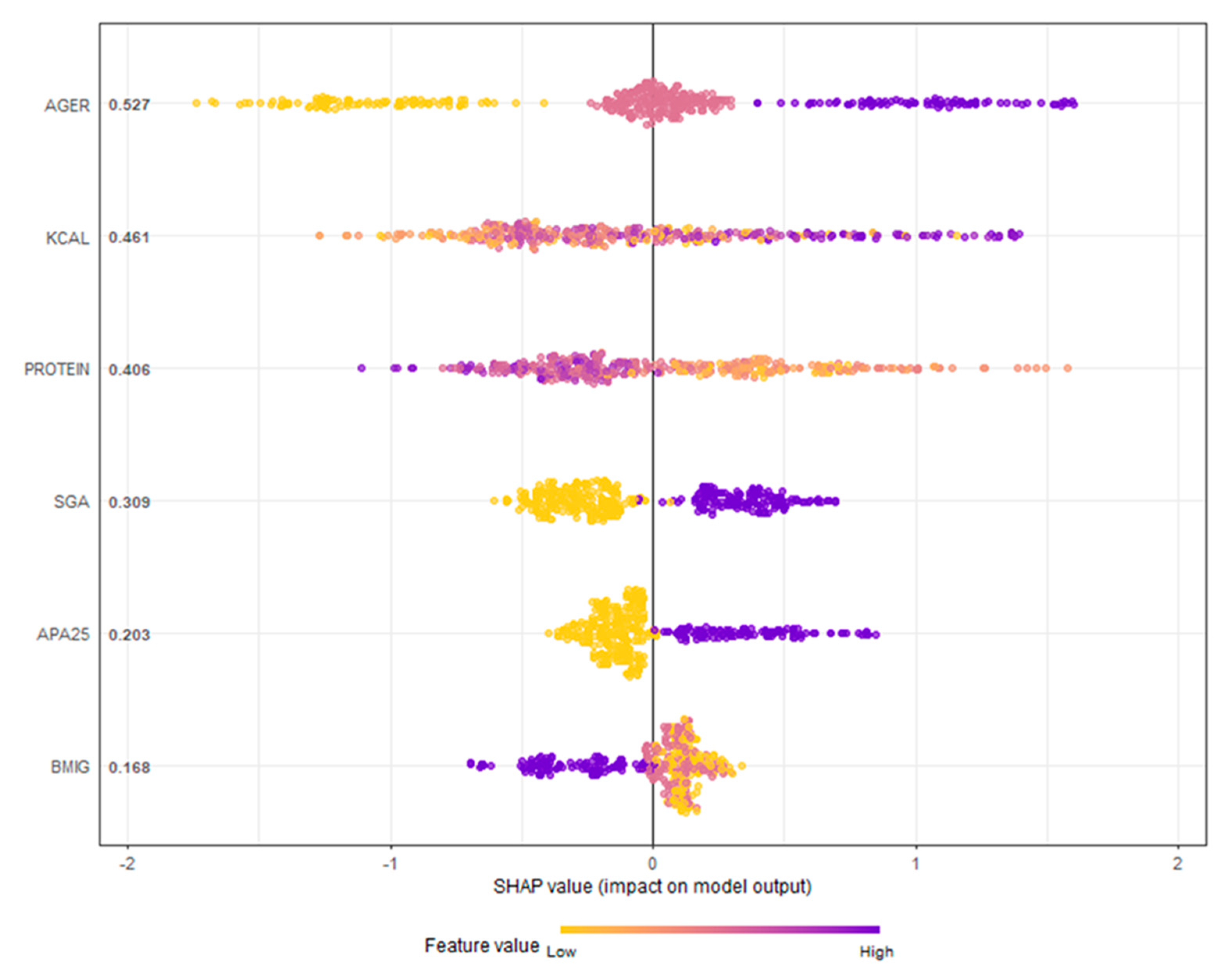

6. Ensemble Classification Tree Models

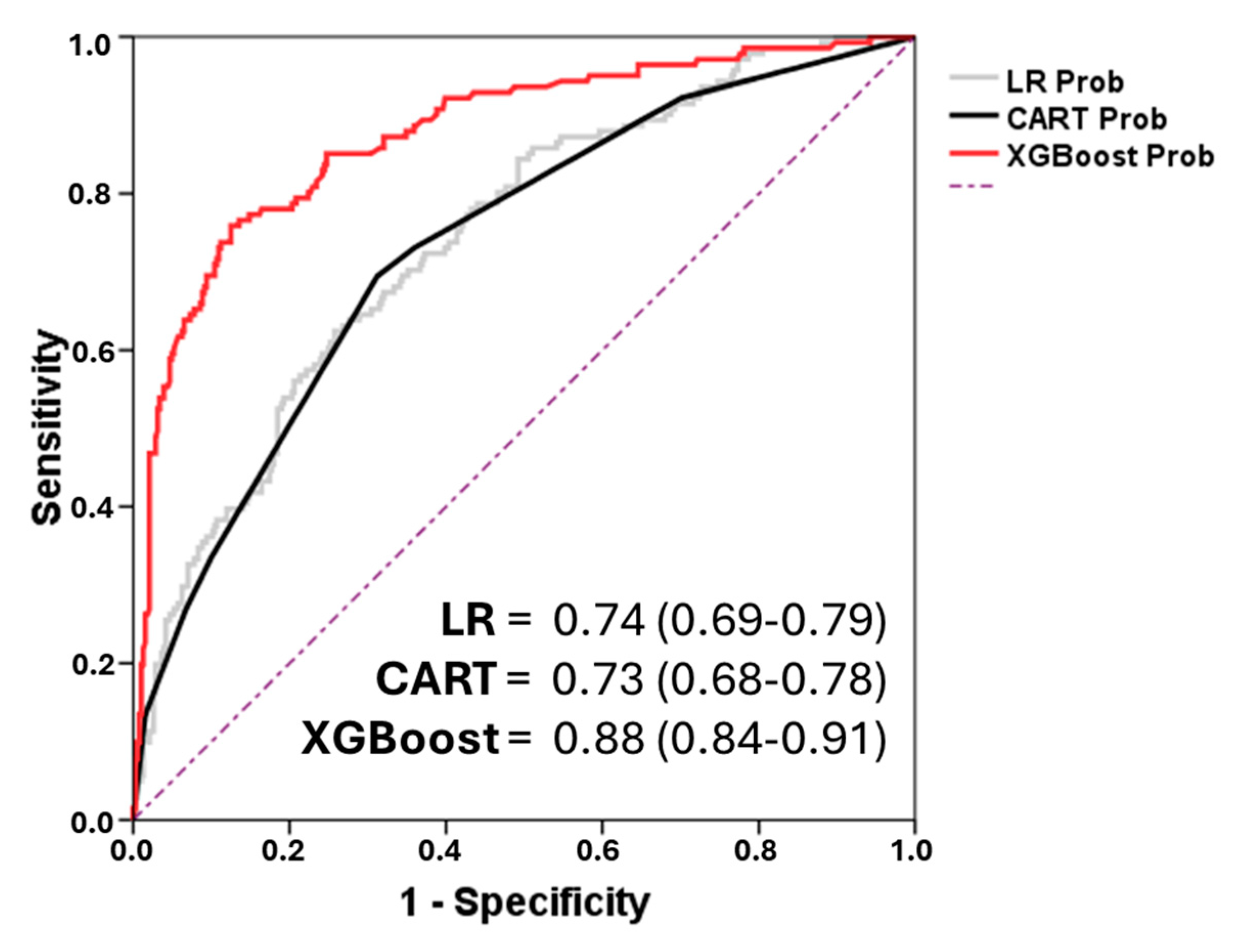

7. Model Evaluation

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

- -

- How CTs can be used to establish cut-off points for continuous variables.

- -

- How they can identify interactions between variables that might go unnoticed in traditional regression models.

- -

- How multivariable CT models generate decision rules and stratify patient risk based on the most influential predictors.

- -

- How ensemble methods such as Random Forest and XGBoost improve predictive accuracy.

- -

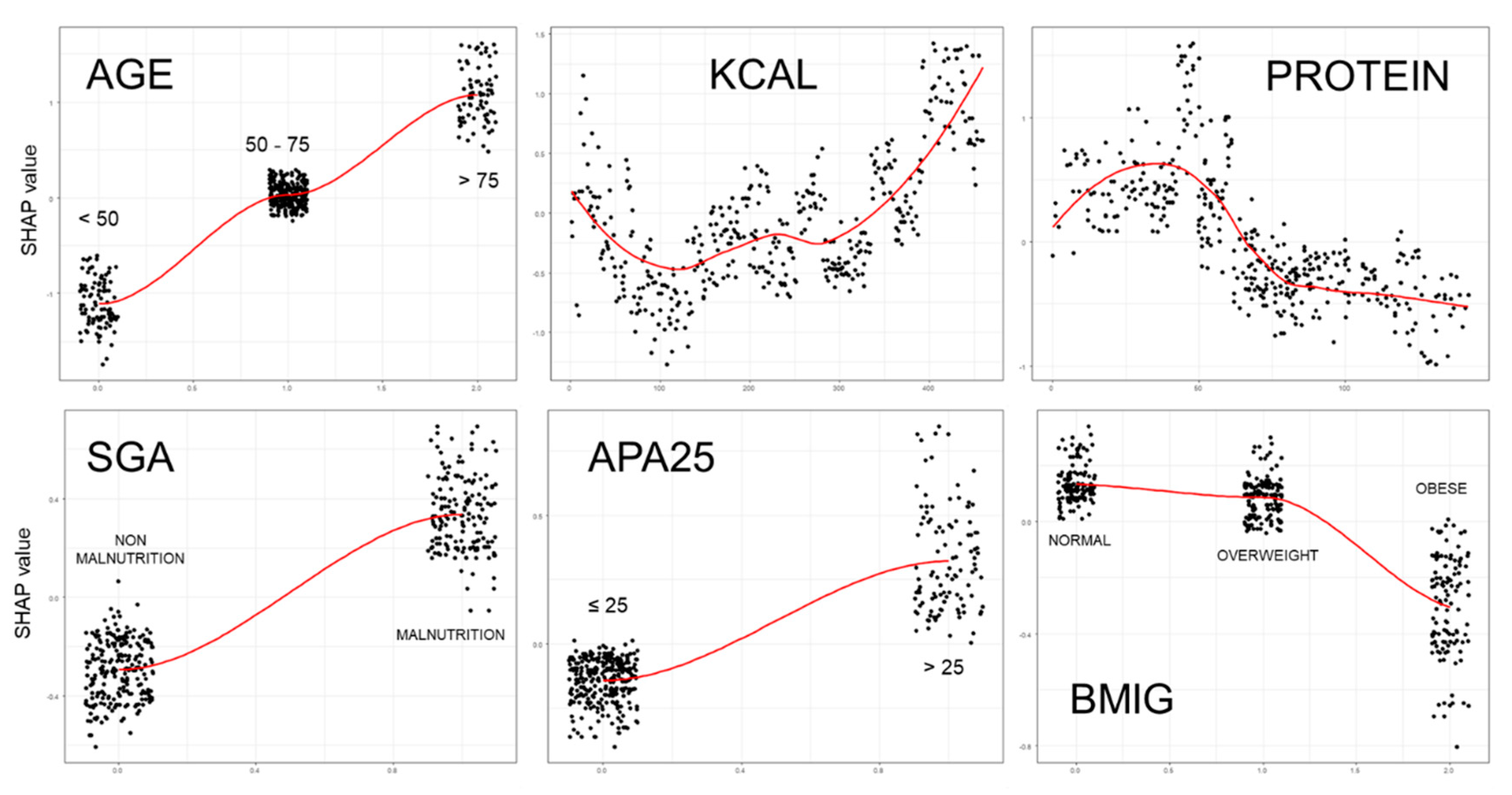

- And finally, how explanatory tools like SHAP values can provide insight into the structure and predictions of complex models.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations:

| AdaBoost | Adaptive Boosting |

| APACHE II | Acute Physiology and Chronic Health disease Classification System II |

| AUC ROC | The area under the ROC curve |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| C4.5 | Concept learning systems version 4.5 |

| CART | Classification and regression tree |

| CHAID | Chi-square automatic interaction detection tree |

| CRUISE | Classification Rule with Unbiased Interaction Selection and Estimation |

| CT | Classification Tree |

| ctree | Conditional inference trees |

| ENPIC | Evaluation of Practical Nutrition Practices in the Critical Care Patient |

| FACT | Fast and Accurate Classification Tree |

| GUIDE | Generalized Unbiased Interaction Detection and Estimation |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| Python | Python software |

| QUEST | Quick Unbiased and Efficient Statistical Tree |

| R | The R Project for Statistical Computing |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| TRIPOD | Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis |

| WEKA | Waikato Environment for Knowledge Analysis |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Podgorelec, V; Kokol, P; Stiglic, B; Rozman, I. Decision trees: an overview and their use in medicine. J. Med. Syst. 2002, 26(5), 445-63. [CrossRef]

- Wei-Yin, L. Fifty Years of Classification and Regression Trees. Int. Stat. Rev. 2014, 82,3, 329-348. [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, JR. Induction of decision trees. Mach. Learn. 1986, 1, 81-106.

- Trujillano, J; Sarria-Santamera, A; Esquerda, A; Badia, M; Palma, M; March, J. Approach to the methodology of classification and regression trees. Gac. Sanit. 2008, 22(1),65-72. https://doi.org/10.1157/13115113. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T. Decision tree learning. In Machine Learning; Mitchell, T, Ed McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997.

- Lemon, SC; Roy, J; Clark, MA; Friedmann, PD; Rakowski, W. Classification and regression tree analysis in public health: methodological review and comparison with logistic regression. Ann. Behav. Med. 2003, 26(3),172-81. [CrossRef]

- Shang, H; Ji, Y; Cao, W; Yi, J. A predictive model for depression in elderly people with arthritis based on the TRIPOD guidelines. Geriatr. Nurs. 2025, 29(63), 85-93. [CrossRef]

- Speiser, JL; Callahan, KE; Houston, DK; Fanning, J; Gill, TM; Guralnik, JM; Newman, AB; Pahor, M; Rejeski, WJ; Miller, ME. Machine Learning in Aging: An Example of Developing Prediction Models for Serious Fall Injury in Older Adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2021, 76(4), 647-654. [CrossRef]

- Trujillano, J; Badia, M; Serviá, L; March, J; Rodriguez-Pozo, A. Stratification of the severity of critically ill patients with classification trees. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2009, 9;9:83. [CrossRef]

- Yin, L; Lin, X; Liu, J; Li, N; He, X; Zhang, M; Guo, J; Yang, J; Deng, L; Wang, Y; et al. Investigation on Nutrition Status and Clinical Outcome of Common Cancers (INSCOC) Group. Classification Tree-Based Machine Learning to Visualize and Validate a Decision Tool for Identifying Malnutrition in Cancer Patients. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 2021, 45(8), 736-1748. [CrossRef]

- Tay, E; Barnett, D; Rowland, M; Kerse, N; Edlin, R; Waters, DL; Connolly, M; Pillai, A; Tupou, E; The, R. Sociodemographic and Health Indicators of Diet Quality in Pre-Frail Older Adults in New Zealand. Nutrients. 2023, 15(20),4416. [CrossRef]

- Marchitelli, S; Mazza, C; Ricci, E; Faia, V; Biondi, S; Colasanti, M; Cardinale, A; Roma, P; Tambelli, R. Identification of Psychological Treatment Dropout Predictors Using Machine Learning Models on Italian Patients Living with Overweight and Obesity Ineligible for Bariatric Surgery. Nutrients. 2024,16(16), 2605. [CrossRef]

- Khozeimeh, F; Sharifrazi, D; Izadi, NH; Joloudari, JH; Shoeibi, A; Alizadehsani, R; Tartibi, M; Hussain, S; Sani, ZA; Khodatars, M; et al. RF-CNN-F: random forest with convolutional neural network features for coronary artery disease diagnosis based on cardiac magnetic resonance. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12(1),11178. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L; Friedman, JH; Olshen, RA; Stone, CJ. Classification and Regression Trees. Belmont (CA), USA, Wadsworth Publishing Co. 1984.

- Kass, GV. An exploratory for investigating large quantities of categorical data. Ann. Appl. Stat. 1980, 29,119-127. [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, JR. C4.5: Programs for Machine learning. San Mateo (CA), USA, Morgan Kaufmann.1993.

- Hothorn, T; Hornik, K; Zeileis, A. Unbiased Recursive Partitioning: A Conditional Inference Framework. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2006, 15(3), 651–674. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forest. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45,5-32. [CrossRef]

- SPSS Inc. AnswerTree User’s Guide. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc.; 2001.

- Hall, M; Frank, E; Holmes, G; Pfahringer, B; Reutemann, P; Witten, IH. The WEKA data mining software. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newslett. 2009,11. [CrossRef]

- Van Rossum, G; Drake Jr, FL. Python reference manual. Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica (CWI). 1995.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2021. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/.2021.

- Lopez-Delgado, JC; Sanchez-Ales, L; Flordelis-Lasierra, JL; Mor-Marco, E; Bordeje-Laguna, ML; Portugal-Rodriguez, E; Lorencio-Cardenas, C; Vera-Artazcoz, P; Aldunate-Calvo, S; Llorente-Ruiz, et al. Nutrition Therapy in Critically Ill Patients with Obesity: An Observational Study. Nutrients. 2025,17(4), 732. [CrossRef]

- Yébenes, JC; Bordeje-Laguna, ML; Lopez-Delgado, JC; Lorencio-Cardenas, C; Martinez De Lagran Zurbano, I; Navas-Moya, E; Servia-Goixart, L. Smartfeeding: A Dynamic Strategy to Increase Nutritional Efficiency in Critically Ill Patients-Positioning Document of the Metabolism and Nutrition Working Group and the Early Mobilization Working Group of the Catalan Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine (SOCMiC). Nutrients. 2024, 16(8),1157. [CrossRef]

- Servia-Goixart, L; Lopez-Delgado, JC; Grau-Carmona, T; Trujillano-Cabello, J; Bordeje-Laguna, ML; Mor-Marco, E; Portugal-Rodriguez, E; Lorencio-Cardenas, C; Montejo-Gonzalez, JC; Vera-Artazcoz, P; et al. Evaluation of Nutritional Practices in the Critical Care patient (The ENPIC study): Does nutrition really affect ICU mortality? Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 2022, 47, 325-332. [CrossRef]

- Cahill, NE; Heyland, DK. Bridging the guideline-practice gap in critical care nutrition: a review of guideline implementation studies. J. Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2010, 34,653-9. [CrossRef]

- Gruberg, L; Weissman, NJ; Waksman, R; Fuchs, S; Deible, R; Pinnow, EE; Ahmed, LM; Kent, KM; Pichard, AD; Suddath, WO; et al. The impact of obesity on the short-term and long-term outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: the obesity paradox? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002, 39(4),578-84. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, MK; Mogensen, KM; Casey, JD; McKane, CK; Moromizato, T; Rawn, JD; Christopher, KB. The relationship among obesity, nutritional status, and mortality in the critically ill. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43(1),87-100. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D; Wang, C; Lin, Q; Li, T. The obesity paradox for survivors of critically ill patients. Crit. Care. 2022, 26(1),198. [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, RN. The obesity paradox in the ICU: real or not? Crit. Care. 2013, 17(3),154. [CrossRef]

- Ripoll, JG; Bittner, EA. Obesity and Critical Illness-Associated Mortality: Paradox, Persistence and Progress. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 51(4),551-554. [CrossRef]

- Knaus, WA; Zimmerman, JE; Wagner, DP; Draper, EA; Lawrence, DE. APACHE-acute physiology and chronic health evaluation: a physiologically based classification system. Crit. Care Med. 1981, 9(8), 591-7. [CrossRef]

- Porcel, JM; Trujillano, J; Porcel, L; Esquerda, A; Bielsa S. Development and validation of a diagnostic prediction model for heart failure-related pleural effusions: the BANCA score. ERJ Open Res. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Prieto, LE; Gómez-Martínez, S; Vicente-Castro, I; Heredia, C; González-Romero, EA; Martín-Ridaura, MDC; Ceinos, M; Picón, MJ; Marcos, A; Nova, E. Effects of Moringa oleifera Lam. Supplementation on Inflammatory and Cardiometabolic Markers in Subjects with Prediabetes. Nutrients. 2022, 14(9),1937. [CrossRef]

- Cawthon PM, Patel SM, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB, Santanasto A, Kiel DP, Travison TG, Lane N, Cummings SR, Orwoll ES, et al. What Cut-Point in Gait Speed Best Discriminates Community-Dwelling Older Adults With Mobility Complaints From Those Without? A Pooled Analysis From the Sarcopenia Definitions and Outcomes Consortium. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2021, 76(10), e321-e327. [CrossRef]

- Tamanna, T; Mahmud, S; Salma, N; Hossain, MM; Karim, MR. Identifying determinants of malnutrition in under-five children in Bangladesh: insights from the BDHS-2022 cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15(1), 14336. [CrossRef]

- Turjo, EA; Rahman, MH. Assessing risk factors for malnutrition among women in Bangladesh and forecasting malnutrition using machine learning approaches. BMC Nutr. 2024, 10(1),22. [CrossRef]

- Reusken, M; Coffey, C; Cruijssen, F; Melenberg, B; van Wanrooij, C. Identification of factors associated with acute malnutrition in children under 5 years and forecasting future prevalence: assessing the potential of statistical and machine learning methods. BMJ Public Health. 2025, 3(1),e001460. [CrossRef]

- Li, N; Peng, E; Liu, F. Prediction of lymph node metastasis in cervical cancer patients using AdaBoost machine learning model: analysis of risk factors. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2025, 5(3),1158-1173. [CrossRef]

- Wong, JE; Yamaguchi, M; Nishi, N; Araki, M; Wee, LH. Predicting Overweight and Obesity Status Among Malaysian Working Adults With Machine Learning or Logistic Regression: Retrospective Comparison Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6(12),e40404. [CrossRef]

- Lian, R; Tang, H; Chen, Z; Chen, X; Luo, S; Jiang, W; Jiang, J; Yang, M. Development and multi-center cross-setting validation of an explainable prediction model for sarcopenic obesity: a machine learning approach based on readily available clinical features. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2025, 37(1),63. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y; Su, S; Wang, X; Mao, J; Ni, X; Li, A; Liang, Y; Zeng, X. Comparative study of XGBoost and logistic regression for predicting sarcopenia in postsurgical gastric cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2025, 5(1),12808. [CrossRef]

- Collins, GS; Reitsma, JB; Altman, DG; Moons, KG. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 62(1),55–63. [CrossRef]

- Harper, PR. A review and comparison of classification algorithms for medical decision making. Health Policy. 2005, 71(3), 315-31. [CrossRef]

- El-Latif, EIA; El-Dosuky, M; Darwish, A; Hassanien, AE. A deep learning approach for ovarian cancer detection and classification based on fuzzy deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14(1),26463. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, SM; Nair, B; Vavilala, MS; Horibe, M; Eisses, MJ; Adams, T; Liston, DE; Low, DK; Newman, SF; Kim, J; Lee, SI. Explainable machine-learning predictions for the prevention of hypoxaemia during surgery. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2(10),749-760. [CrossRef]

| 1- SIMPLE CLASSIFICATION TREES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CART | CHAID | C4.5 | ctree | |

| Description | Classification and Regression Tree | Chi-Square Automatic Interaction Detection | Concept Learning Systems Version 4.5 |

Conditional inference trees |

| Developer | Breiman (1984) | Kass (1980) | Quinlan (1993) | Hothorm (2006) |

| Primary Use | Many disciplines with little data | Applied statisticians | Data miners | Applied statisticians |

| Splitting Method | Entropy Gini index |

Chi-square tests F test |

Gain Ratio | Asymptotic approximations |

| Branch Limitations | Best binary split | Number of values of the input | Best binary split | Bonferroni-adjusted p-values |

| Pruning | Cross-validation | Best binary split p-value |

Misclassification rates | No pruning |

| Software * | Answer-Tree WEKA R - Python |

Answer-Tree R- Python |

WEKA R-Python |

R - Python |

| 2- ENSEMBLED CLASSIFICATION TREES | ||||

| Random Forest | AdaBoost | XG-Boost | ||

| Description | Uncorrelated forest | Adaptive Boosting | Extreme gradient boosting | |

| Developer | Breiman and Cutler (2001) | Freund and Schapire (1995) | Chen y Guestrin (2016) | |

| Ensembled Method | Bagging Parallel |

Adaptive Boosting |

Boosting Gradient Descent |

|

| Software * | R- Python-Java | R – Python - Java | R-Python - Java | |

| 3- HYBRID MODELS | ||||

| Fuzzy Random Forest | Random Forest Neural Network | |||

| Other method | Fuzzy logic | Neural Network | ||

| Developer | Olaru (2003) | Khozeimeh (2022) | ||

| Software * | C language | Python | ||

| All patients n = 525 |

Normal n = 165 |

Overweight n = 210 |

Obese n = 150 |

p-Value | ||

| Baseline characteristics & comorbidities | ||||||

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 61.5 ± 15 | 58.8 ± 16.5 | 62.8 ± 14.7 | 62.7 ± 13.5 | 0.05 | |

| Sex, male patients, n (%) | 67.2% (353) | 64.8% (107) | 74.8% (157) | 59.3% (89) | 0.003B | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 43.6% (229) | 33.9% (56) | 41.9% (88) | 56.7% (85) | 0.01A, B | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 25% (131) | 21.2% (35) | 20% (42) | 36% (54) | 0.001A, B | |

| AMI, n (%) | 14.1% (74) | 8.5% (14) | 16.7% (35) | 16.7% (25) | 0.04 B | |

| Neoplasia, n (%) | 20.6% (108) | 24.2% (40) | 19.5% (41) | 18% (27) | 0.11 | |

| Type of patient | Medical, n (%) | 63.8% (335) | 65.5% (108) | 62.9% (132) | 63.3% (95) | 0.81 |

| Trauma, n (%) | 12.6% (66) | 10.9% (18) | 15.2% (32) | 10.7% (16) | 0.75 | |

| Surgery, n (%) | 23.6% (124) | 23.6% (39) | 21.9% (46) | 26% (39) | 0.67 | |

| Prognosis ICU scores & nutrition status on ICU admission | ||||||

| APACHE II, mean ± SD | 20.3 ± 7.9 | 19.7 ± 7.6 | 20.1 ± 7.5 | 21.2 ± 8.5 | 0.18 | |

| Malnutrition (based on SGA), n (%) | 41% (215) | 52.7% (87) | 37.1% (78) | 33.3% (50) | 0.01 B | |

| Characteristics of Medical Nutrition Therapy | ||||||

| Early nutrition, < 48 h, n (%) | 74.9% (393) | 77.6% (128) | 75.2% (158) | 71.3% (107) | 0.43 | |

| Kcal/kg/day, mean ± SD | 19 ± 5.6 | 23.1 ± 6 | 18.6 ± 3.7 | 15.27 ± 4.24 | 0.001 A | |

| Protein, g/kg/day, mean ± SD | 1 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.01 A, B | |

| EN | 63.2% (332) | 59.4% (98) | 64.3% (135) | 66% (99) | 0.34 | |

| PN | 15.4% (81) | 13.3% (22) | 16.2% (34) | 16.7% (25) | 0.85 | |

| EN-PN | 7.8% (41) | 8.5% (14) | 7.6% (16) | 7.3% (11) | 0.92 | |

| PN-EN | 13.5% (71) | 18.8% (31) | 11.9% (25) | 10% (15) | 0.27 | |

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 92.8% (487) | 89.1% (147) | 93.8% (197) | 95.3% (143) | 0.08 | |

| Vasoactive drug support, n (%) | 77% (404) | 73.9% (122) | 79.5% (167) | 76.7% (115) | 0.44 | |

| Renal replacement therapy, n (%) | 16.6% (87) | 16.4% (27) | 12.9% (27) | 22% (33) | 0.07 | |

| ICU stay, days, mean ± SD | 20.3 ± 18 | 18.2 ± 13.8 | 21.1 ± 17.1 | 21.6 ± 22.5 | 0.08 | |

| 28-day mortality, n (%) | 26.7% (140) | 29.1% (48) | 27.1% (57) | 23.3% (35) | 0.51 | |

| Variable | OR (95%CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| < 50 | 1 | |

| 50-75 | 3.3 (1.7-6.5) | 0.001 |

| > 75 | 7.0 (3.3-14.9) | < 0.001 |

| SEX (MALE) | 1.0 (0.6-1.6) | 0.998 |

| APACHE II score | ||

| ≤ 25 | 1 | |

| > 25 | 2.2 (1.4-3.5) | < 0.001 |

| BMI groups | ||

| Normal | 1 | |

| Overweight | 0.9 (0.5-1.5) | 0.623 |

| Obese | 0.7 (0.4-1.4) | 0.651 |

| SGA | ||

| Non malnutrition | 1 | |

| Malnutrition | 2.6 (1.74.0) | < 0.001 |

| Median Kcal/Kg/day | 1.1 (0.9-1.1) | 0.315 |

| Median g protein/Kg/day | 0.3 (0.1-0.9) | 0.022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).