Submitted:

18 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Data Pre-Processing

3.3. Selection of Learning Algorithm

3.3.1. AdaBoost Classifier

3.3.2. Gradient Boosting Classifier

3.3.3. Random Forest Classifier

3.3.4. Extra Trees Classifier

3.3.5. Bagging Classifier

3.3.6. Performance Metrics

3.3.7. Evaluation of Model Stability

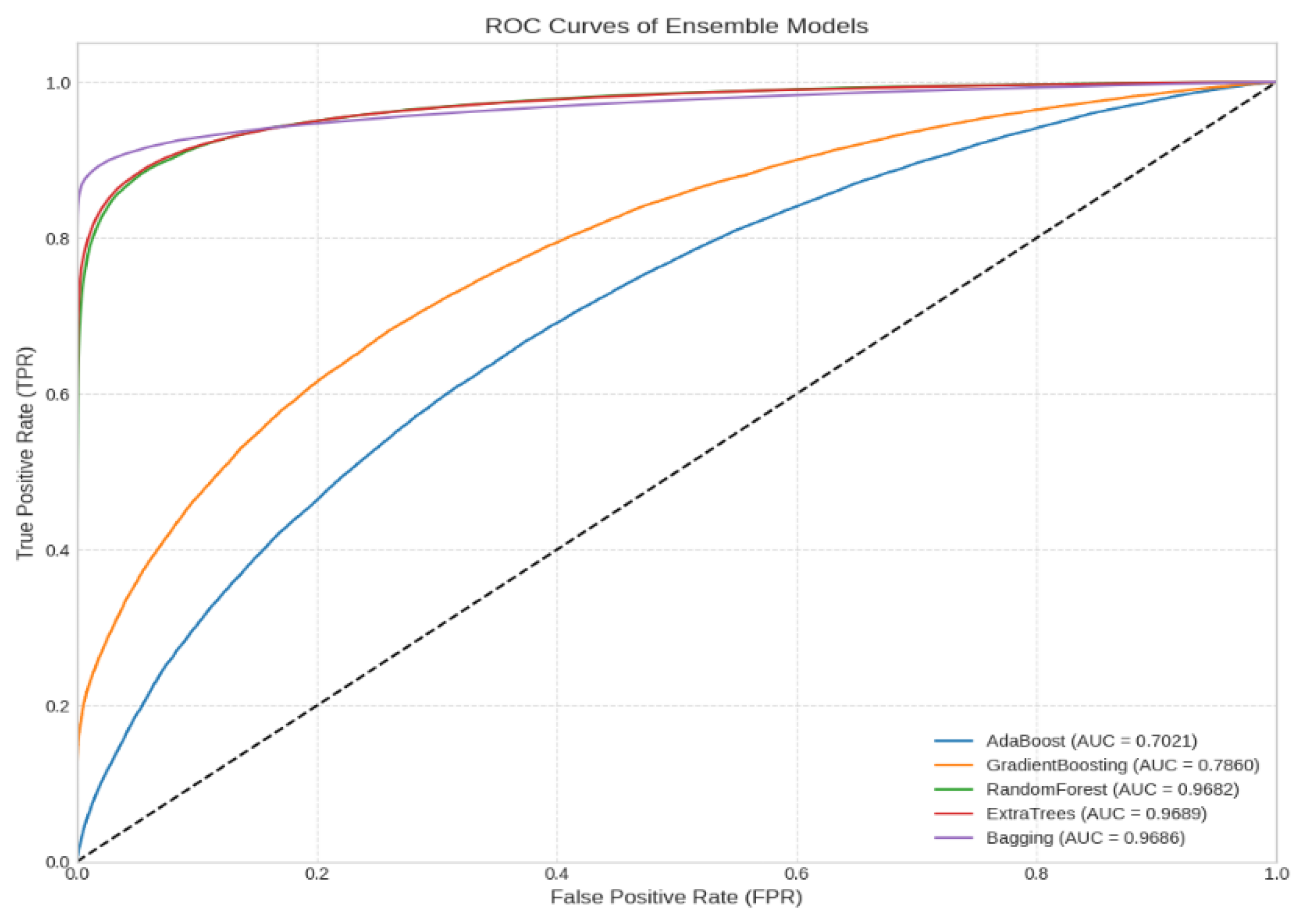

3.3.8. ROC Curve

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

NOTE

References

- Boudali, I.; Chebaane, S.; Zitouni, Y. A Predictive Approach for Myocardial Infarction Risk Assessment Using Machine Learning and Big Clinical Data. Healthcare Analytics 2024, 5, 100319. [CrossRef]

- Kaptoge, S.; Pennells, L.; De Bacquer, D.; Cooney, M.T.; Kavousi, M.; Stevens, G.; Riley, L.M.; Savin, S.; Khan, T.; Altay, S.; et al. World Health Organization Cardiovascular Disease Risk Charts: Revised Models to Estimate Risk in 21 Global Regions. The Lancet Global Health 2019, 7, e1332–e1345. [CrossRef]

- Mc Namara, K.; Alzubaidi, H.; Jackson, J.K. Cardiovascular Disease as a Leading Cause of Death: How Are Pharmacists Getting Involved? IPRP 2019, Volume 8, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.B.; Narula, J.; Fuster, V. Recognizing Global Burden of Cardiovascular Disease and Related Chronic Diseases. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine: A Journal of Translational and Personalized Medicine 2012, 79, 632–640. [CrossRef]

- Nansseu, J.R.; Tankeu, A.T.; Kamtchum-Tatuene, J.; Noubiap, J.J. Fixed-Dose Combination Therapy to Reduce the Growing Burden of Cardiovascular Disease in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Feasibility and Challenges. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension 2018, 20, 168–173. [CrossRef]

- Janez, A.; Muzurovic, E.; Bogdanski, P.; Czupryniak, L.; Fabryova, L.; Fras, Z.; Guja, C.; Haluzik, M.; Kempler, P.; Lalic, N.; et al. Modern Management of Cardiometabolic Continuum: From Overweight/Obesity to Prediabetes/Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Recommendations from the Eastern and Southern Europe Diabetes and Obesity Expert Group. Diabetes Ther 2024, 15, 1865–1892. [CrossRef]

- Jagannathan, R.; Patel, S.A.; Ali, M.K.; Narayan, K.M.V. Global Updates on Cardiovascular Disease Mortality Trends and Attribution of Traditional Risk Factors. Curr Diab Rep 2019, 19, 44. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, L.; Mesinovic, M.; Yang, K.-W.; Eid, M.A. Explainable Prediction of Acute Myocardial Infarction Using Machine Learning and Shapley Values. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 210410–210417. [CrossRef]

- Writing Committee:; Smith, S.C.; Collins, A.; Ferrari, R.; Holmes, D.R.; Logstrup, S.; McGhie, D.V.; Ralston, J.; Sacco, R.L.; Stam, H.; et al. Our Time: A Call to Save Preventable Death from Cardiovascular Disease (Heart Disease and Stroke). European Heart Journal 2012, 33, 2910–2916. [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, A.; Griffiths, U.; Murphy, A.; Legido-Quigley, H.; Lamptey, P.; Perel, P. The Economic Burden of Cardiovascular Disease and Hypertension in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 975. [CrossRef]

- Parry, M.; Bjørnnes, A.K.; Nickerson, N.; Lie, I. Family Caregivers and Cardiovascular Disease: An Intersectional Approach to Good Health and Wellbeing. In International Perspectives on Family Caregiving; Stanley, S., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited, 2025; pp. 135–157 ISBN 978-1-83549-612-1.

- Laslett, L.J.; Alagona, P.; Clark, B.A.; Drozda, J.P.; Saldivar, F.; Wilson, S.R.; Poe, C.; Hart, M. The Worldwide Environment of Cardiovascular Disease: Prevalence, Diagnosis, Therapy, and Policy Issues. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2012, 60, S1–S49. [CrossRef]

- Capotosto, L.; Massoni, F.; De Sio, S.; Ricci, S.; Vitarelli, A. Early Diagnosis of Cardiovascular Diseases in Workers: Role of Standard and Advanced Echocardiography. BioMed Research International 2018, 2018, 7354691. [CrossRef]

- Forman, D.; Bulwer, B.E. Cardiovascular Disease: Optimal Approaches to Risk Factor Modification of Diet and Lifestyle. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med 2006, 8, 47–57. [CrossRef]

- Hymowitz, N. Behavioral Approaches to Preventing Heart Disease: Risk Factor Modification. International Journal of Mental Health 1980, 9, 27–69. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Hamayun, S.; Wahab, A.; Khan, S.U.; Rehman, M.U.; Haq, Z.U.; Rehman, K.U.; Ullah, A.; Mehreen, A.; Awan, U.A.; et al. Smart Technologies Used as Smart Tools in the Management of Cardiovascular Disease and Their Future Perspective. Current Problems in Cardiology 2023, 48, 101922. [CrossRef]

- Thupakula, S.; Nimmala, S.S.R.; Ravula, H.; Chekuri, S.; Padiya, R. Emerging Biomarkers for the Detection of Cardiovascular Diseases. Egypt Heart J 2022, 74, 77. [CrossRef]

- Fathil, M.F.M.; Md Arshad, M.K.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; Hashim, U.; Adzhri, R.; Ayub, R.M.; Ruslinda, A.R.; Nuzaihan M.N., M.; Azman, A.H.; Zaki, M.; et al. Diagnostics on Acute Myocardial Infarction: Cardiac Troponin Biomarkers. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2015, 70, 209–220. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.P.; Jain, A.; Khan, Z.; Kohli, V.; Bharmal, R.N.; Kartikeyan, S.; Bisen, P.S. Cardiac Troponins I and T: Molecular Markers for Early Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Accurate Triaging of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Mol Diagn Ther 2012, 16, 371–381. [CrossRef]

- Garg, P.; Morris, P.; Fazlanie, A.L.; Vijayan, S.; Dancso, B.; Dastidar, A.G.; Plein, S.; Mueller, C.; Haaf, P. Cardiac Biomarkers of Acute Coronary Syndrome: From History to High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin. Intern Emerg Med 2017, 12, 147–155. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, J. Advances in Electrochemical Detection of B-Type Natriuretic Peptide as a Heart Failure Biomarker. International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2024, 19, 100748. [CrossRef]

- Onitilo, A.A.; Engel, J.M.; Stankowski, R.V.; Liang, H.; Berg, R.L.; Doi, S.A.R. High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein (Hs-CRP) as a Biomarker for Trastuzumab-Induced Cardiotoxicity in HER2-Positive Early-Stage Breast Cancer: A Pilot Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012, 134, 291–298. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.K. Emerging Risk Biomarkers in Cardiovascular Diseases and Disorders. Journal of Lipids 2015, 2015, 971453. [CrossRef]

- Georgoulis, M.; Chrysohoou, C.; Georgousopoulou, E.; Damigou, E.; Skoumas, I.; Pitsavos, C.; Panagiotakos, D. Long-Term Prognostic Value of LDL-C, HDL-C, Lp(a) and TG Levels on Cardiovascular Disease Incidence, by Body Weight Status, Dietary Habits and Lipid-Lowering Treatment: The ATTICA Epidemiological Cohort Study (2002–2012). Lipids Health Dis 2022, 21, 141. [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, A.; Yilmaz, M.I.; Saglam, M.; Unal, H.U.; Gok, M.; Cetinkaya, H.; Karaman, M.; Haymana, C.; Eyileten, T.; Oguz, Y.; et al. The Role of Plasma Triglyceride/High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Ratio to Predict Cardiovascular Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease. Lipids Health Dis 2015, 14, 29. [CrossRef]

- Djaberi, R.; Beishuizen, E.D.; Pereira, A.M.; Rabelink, T.J.; Smit, J.W.; Tamsma, J.T.; Huisman, M.V.; Jukema, J.W. Non-Invasive Cardiac Imaging Techniques and Vascular Tools for the Assessment of Cardiovascular Disease in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 1581–1593. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.; Farzaneh, N.; Duda, M.; Horan, K.; Andersson, H.B.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Nallamothu, B.K.; Najarian, K. A Review of Automated Methods for Detection of Myocardial Ischemia and Infarction Using Electrocardiogram and Electronic Health Records. IEEE Reviews in Biomedical Engineering 2017, 10, 264–298. [CrossRef]

- Klaeboe, L.G.; Edvardsen, T. Echocardiographic Assessment of Left Ventricular Systolic Function. J Echocardiogr 2019, 17, 10–16. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Lin, A.; Yuvaraj, J.; Nicholls, S.J.; Wong, D.T.L. Cardiac Computed Tomography Radiomics for the Non-Invasive Assessment of Coronary Inflammation. Cells 2021, 10, 879. [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, S.; Conte, E.; Pontone, G.; Baggiano, A.; Annoni, A.; Formenti, A.; Mancini, M.E.; Guglielmo, M.; Muscogiuri, G.; Tanzilli, A.; et al. State-of-the-Art-Myocardial Perfusion Stress Testing: Static CT Perfusion. Journal of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography 2020, 14, 294–302. [CrossRef]

- Beller, G.A.; Heede, R.C. SPECT Imaging for Detecting Coronary Artery Disease and Determining Prognosis by Noninvasive Assessment of Myocardial Perfusion and Myocardial Viability. J. of Cardiovasc. Trans. Res. 2011, 4, 416–424. [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, N.A.; Farghaly Abdelaliem, S.M.; Malki, A.; Gad, I.; Ewis, A.; Atlam, E. Advanced Machine Learning Techniques for Cardiovascular Disease Early Detection and Diagnosis. J Big Data 2023, 10, 144. [CrossRef]

- Boudali, I.; Chebaane, S.; Zitouni, Y. A Predictive Approach for Myocardial Infarction Risk Assessment Using Machine Learning and Big Clinical Data. Healthcare Analytics 2024, 5, 100319. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, A.C.; Nikolaidou, M.; Caballero, F.F.; Engchuan, W.; Sanchez-Niubo, A.; Arndt, H.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Haro, J.M.; Chatterji, S.; Georgousopoulou, E.N.; et al. Machine Learning Methodologies versus Cardiovascular Risk Scores, in Predicting Disease Risk. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018, 18, 179. [CrossRef]

- Saikumar, K.; Rajesh, V. A Machine Intelligence Technique for Predicting Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Using Radiology Dataset. Int J Syst Assur Eng Manag 2024, 15, 135–151. [CrossRef]

- Hakim, Md.A.; Jahan, N.; Zerin, Z.A.; Farha, A.B. Performance Evaluation and Comparison of Ensemble Based Bagging and Boosting Machine Learning Methods for Automated Early Prediction of Myocardial Infarction. In Proceedings of the 2021 12th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT); July 2021; pp. 1–6.

- Rai, H.M.; Chatterjee, K. Hybrid CNN-LSTM Deep Learning Model and Ensemble Technique for Automatic Detection of Myocardial Infarction Using Big ECG Data. Appl Intell 2022, 52, 5366–5384. [CrossRef]

- Bian, K.; Priyadarshi, R. Machine Learning Optimization Techniques: A Survey, Classification, Challenges, and Future Research Issues. Arch Computat Methods Eng 2024, 31, 4209–4233. [CrossRef]

- Aliferis, C.; Simon, G. Overfitting, Underfitting and General Model Overconfidence and Under-Performance Pitfalls and Best Practices in Machine Learning and AI. In Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Health Care and Medical Sciences: Best Practices and Pitfalls; Simon, G.J., Aliferis, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2024; pp. 477–524 ISBN 978-3-031-39355-6.

- Cai, Y.-Q.; Gong, D.-X.; Tang, L.-Y.; Cai, Y.; Li, H.-J.; Jing, T.-C.; Gong, M.; Hu, W.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Zhang, X.; et al. Pitfalls in Developing Machine Learning Models for Predicting Cardiovascular Diseases: Challenge and Solutions. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2024, 26, e47645. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.H.D.M.; dos Santos Coelho, L. Ensemble Approach Based on Bagging, Boosting and Stacking for Short-Term Prediction in Agribusiness Time Series. Applied Soft Computing 2020, 86, 105837. [CrossRef]

- Krittanawong, C.; Virk, H.U.H.; Bangalore, S.; Wang, Z.; Johnson, K.W.; Pinotti, R.; Zhang, H.; Kaplin, S.; Narasimhan, B.; Kitai, T.; et al. Machine Learning Prediction in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 16057. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, M.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, R.; Li, N.; Chen, Z.; Yan, H.; Shi, Q. An Artificial Intelligence-Based Risk Prediction Model of Myocardial Infarction. BMC Bioinformatics 2022, 23, 217. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, J.; Sun, L.; Cai, J.; Wang, S.; Zeng, L.; Sun, S. Application of Machine Learning to Predict the Occurrence of Arrhythmia after Acute Myocardial Infarction. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2021, 21, 301. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.D.; Sunkaria, R.K. Inferior Myocardial Infarction Detection Using Stationary Wavelet Transform and Machine Learning Approach. SIViP 2018, 12, 199–206. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Seringa, J.; Pinto, F.J.; Henriques, R.; Magalhães, T. Machine Learning Prediction of Mortality in Acute Myocardial Infarction. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2023, 23, 70. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shang, C.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhou, Q. Development and Comparison of Machine Learning-Based Models for Predicting Heart Failure after Acute Myocardial Infarction. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2023, 23, 165. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.M.; Austin, P.C.; Ross, H.J.; Abdel-Qadir, H.; Chicco, D.; Tomlinson, G.; Taheri, C.; Foroutan, F.; Lawler, P.R.; Billia, F.; et al. Machine Learning Compared With Conventional Statistical Models for Predicting Myocardial Infarction Readmission and Mortality: A Systematic Review. Canadian Journal of Cardiology 2021, 37, 1207–1214. [CrossRef]

- Barker, J.; Li, X.; Khavandi, S.; Koeckerling, D.; Mavilakandy, A.; Pepper, C.; Bountziouka, V.; Chen, L.; Kotb, A.; Antoun, I.; et al. Machine Learning in Sudden Cardiac Death Risk Prediction: A Systematic Review. EP Europace 2022, 24, 1777–1787. [CrossRef]

- Chellappan, D.; Rajaguru, H. Generalizability of Machine Learning Models for Diabetes Detection a Study with Nordic Islet Transplant and PIMA Datasets. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 4479. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Pang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y. Interpretable SHAP Model Combining Meta-Learning and Vision Transformer for Lithology Classification Using Limited and Unbalanced Drilling Data in Well Logging. Nat Resour Res 2024, 33, 2545–2565. [CrossRef]

- Rana, N.; Sharma, K.; Sharma, A. Diagnostic Strategies Using AI and ML in Cardiovascular Diseases: Challenges and Future Perspectives. In Deep Learning and Computer Vision: Models and Biomedical Applications: Volume 1; Dulhare, U.N., Houssein, E.H., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 135–165 ISBN 978-981-96-1285-7.

- Taherkhani, A.; Cosma, G.; McGinnity, T.M. AdaBoost-CNN: An Adaptive Boosting Algorithm for Convolutional Neural Networks to Classify Multi-Class Imbalanced Datasets Using Transfer Learning. Neurocomputing 2020, 404, 351–366. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Miao, Q.-G.; Liu, J.-C.; Gao, L. Advance and Prospects of AdaBoost Algorithm. Acta Automatica Sinica 2013, 39, 745–758. [CrossRef]

- Shahraki, A.; Abbasi, M.; Haugen, Ø. Boosting Algorithms for Network Intrusion Detection: A Comparative Evaluation of Real AdaBoost, Gentle AdaBoost and Modest AdaBoost. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2020, 94, 103770. [CrossRef]

- Bentéjac, C.; Csörgő, A.; Martínez-Muñoz, G. A Comparative Analysis of Gradient Boosting Algorithms. Artif Intell Rev 2021, 54, 1937–1967. [CrossRef]

- Bahad, P.; Saxena, P. Study of AdaBoost and Gradient Boosting Algorithms for Predictive Analytics. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Smart Communication 2019; Singh Tomar, G., Chaudhari, N.S., Barbosa, J.L.V., Aghwariya, M.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 235–244.

- Sun, R.; Wang, G.; Zhang, W.; Hsu, L.-T.; Ochieng, W.Y. A Gradient Boosting Decision Tree Based GPS Signal Reception Classification Algorithm. Applied Soft Computing 2020, 86, 105942. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.; Akhir, E.A.P.; Aziz, I.A.; Jaafar, J.; Hasan, M.H.; Abas, A.N.C. A Study on Gradient Boosting Algorithms for Development of AI Monitoring and Prediction Systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computational Intelligence (ICCI); October 2020; pp. 11–16.

- Chowdhury, A.R.; Chatterjee, T.; Banerjee, S. A Random Forest Classifier-Based Approach in the Detection of Abnormalities in the Retina. Med Biol Eng Comput 2019, 57, 193–203. [CrossRef]

- Dhananjay, B.; Venkatesh, N.P.; Bhardwaj, A.; Sivaraman, J. Cardiac Signals Classification Based on Extra Trees Model. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN); August 2021; pp. 402–406.

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C.; Gnasso, A. A Comparison among Interpretative Proposals for Random Forests. Machine Learning with Applications 2021, 6, 100094. [CrossRef]

- Fumera, G.; Roli, F.; Serrau, A. A Theoretical Analysis of Bagging as a Linear Combination of Classifiers. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2008, 30, 1293–1299. [CrossRef]

- Plaia, A.; Buscemi, S.; Fürnkranz, J.; Mencía, E.L. Comparing Boosting and Bagging for Decision Trees of Rankings. J Classif 2022, 39, 78–99. [CrossRef]

- Heydarian, M.; Doyle, T.E.; Samavi, R. MLCM: Multi-Label Confusion Matrix. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 19083–19095. [CrossRef]

- Markoulidakis, I.; Markoulidakis, G. Probabilistic Confusion Matrix: A Novel Method for Machine Learning Algorithm Generalized Performance Analysis. Technologies 2024, 12, 113. [CrossRef]

- Kolesnyk, A.S.; Khairova, N.F. Justification for the Use of Cohen’s Kappa Statistic in Experimental Studies of NLP and Text Mining. Cybern Syst Anal 2022, 58, 280–288. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Xia, B. A Simplified Cohen’s Kappa for Use in Binary Classification Data Annotation Tasks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 164386–164397. [CrossRef]

- Mokeddem, S.A. A Fuzzy Classification Model for Myocardial Infarction Risk Assessment. Appl Intell 2018, 48, 1233–1250. [CrossRef]

- Yates, L.A.; Aandahl, Z.; Richards, S.A.; Brook, B.W. Cross Validation for Model Selection: A Review with Examples from Ecology. Ecological Monographs 2023, 93, e1557. [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; and Yu, B. Estimation Stability With Cross-Validation (ESCV). Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics 2016, 25, 464–492. [CrossRef]

- Raschka, S. Model Evaluation, Model Selection, and Algorithm Selection in Machine Learning 2020.

- Mohd Faizal, A.S.; Hon, W.Y.; Thevarajah, T.M.; Khor, S.M.; Chang, S.-W. A Biomarker Discovery of Acute Myocardial Infarction Using Feature Selection and Machine Learning. Med Biol Eng Comput 2023, 61, 2527–2541. [CrossRef]

- Obuchowski, N.A.; Bullen, J.A. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curves: Review of Methods with Applications in Diagnostic Medicine. Phys. Med. Biol. 2018, 63, 07TR01. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, J.C.; Lyons, P.G.; Chhikara, K.; Chaudhari, V.; Bhavani, S.V.; Nour, M.; Buell, K.G.; Smith, K.D.; Gao, C.A.; Amagai, S.; et al. A Common Longitudinal Intensive Care Unit Data Format (CLIF) for Critical Illness Research. Intensive Care Med 2025, 51, 556–569. [CrossRef]

- Elreedy, D.; Atiya, A.F. A Comprehensive Analysis of Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) for Handling Class Imbalance. Information Sciences 2019, 505, 32–64. [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, A.; Polat, K.; Alhudhaif, A. Classification of Imbalanced Hyperspectral Images Using SMOTE-Based Deep Learning Methods. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 178, 114986. [CrossRef]

- Carreira-Perpiñán, M.Á.; Zharmagambetov, A. Ensembles of Bagged TAO Trees Consistently Improve over Random Forests, AdaBoost and Gradient Boosting. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 ACM-IMS on Foundations of Data Science Conference; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, October 18 2020; pp. 35–46.

- Shao, G.; Tang, L.; Liao, J. Overselling Overall Map Accuracy Misinforms about Research Reliability. Landscape Ecol 2019, 34, 2487–2492. [CrossRef]

- Kolesnyk, A.S.; Khairova, N.F. Justification for the Use of Cohen’s Kappa Statistic in Experimental Studies of NLP and Text Mining. Cybern Syst Anal 2022, 58, 280–288. [CrossRef]

- Demirhan, H.; Yilmaz, A.E. Detection of Grey Zones in Inter-Rater Agreement Studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 2023, 23, 3. [CrossRef]

- Brzezinski, D.; Stefanowski, J. Prequential AUC: Properties of the Area under the ROC Curve for Data Streams with Concept Drift. Knowl Inf Syst 2017, 52, 531–562. [CrossRef]

- Newaz, A.; Mohosheu, M.S.; Al Noman, Md.A. Predicting Complications of Myocardial Infarction within Several Hours of Hospitalization Using Data Mining Techniques. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 2023, 42, 101361. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.; Ojo, S.; Krichen, M.; Alamro, M.A.; Mihoub, A.; Vilcekova, L. A Novel Deep Learning Approach for Myocardial Infarction Detection and Multi-Label Classification. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 76003–76021. [CrossRef]

- Alsirhani, A.; Tariq, N.; Humayun, M.; Naif Alwakid, G.; Sanaullah, H. Intrusion Detection in Smart Grids Using Artificial Intelligence-Based Ensemble Modelling. Cluster Comput 2025, 28, 238. [CrossRef]

- Van den Bruel, A.; Cleemput, I.; Aertgeerts, B.; Ramaekers, D.; Buntinx, F. The Evaluation of Diagnostic Tests: Evidence on Technical and Diagnostic Accuracy, Impact on Patient Outcome and Cost-Effectiveness Is Needed. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2007, 60, 1116–1122. [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Zhu, W. Precision–Recall Curve (PRC) Classification Trees. Evol. Intel. 2022, 15, 1545–1569. [CrossRef]

- Markoulidakis, I.; Markoulidakis, G. Probabilistic Confusion Matrix: A Novel Method for Machine Learning Algorithm Generalized Performance Analysis. Technologies 2024, 12, 113. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.H.; Bradic, J. Boosting in the Presence of Outliers: Adaptive Classification With Nonconvex Loss Functions. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2018, 113, 660–674. [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) Is More Informative Than Cohen’s Kappa and Brier Score in Binary Classification Assessment. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 78368–78381. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.L.; Mentch, L.; Wheeler, B.J.; Tapia, A.L.; Richards, M.; Zhou, S.; Yi, L.; Redline, S.; Buysse, D.J. Use and Misuse of Random Forest Variable Importance Metrics in Medicine: Demonstrations through Incident Stroke Prediction. BMC Med Res Methodol 2023, 23, 144. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lewandrowski, K. Establishing Optimal Cutoff Values for High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin Algorithms in Risk Stratification of Acute Myocardial Infarction. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences 2024, 61, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Sherazi, S.W.A.; Lee, J.Y. A Stacking Ensemble Prediction Model for the Occurrences of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome on Imbalanced Data. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 113692–113704. [CrossRef]

- Kasim, S.; Amir Rudin, P.N.F.; Malek, S.; Ibrahim, K.S.; Wan Ahmad, W.A.; Fong, A.Y.Y.; Lin, W.Y.; Aziz, F.; Ibrahim, N. Ensemble Machine Learning for Predicting In-Hospital Mortality in Asian Women with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI). Sci Rep 2024, 14, 12378. [CrossRef]

| Model | Accuracy | F1 Score | Precision | Recall | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaboost | 0.646122 | 0.645918 | 0.646548 | 0.646179 | 0.702120 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.708342 | 0.708330 | 0.708406 | 0.708360 | 0.786005 |

| RandomForest | 0.912938 | 0.912910 | 0.913365 | 0.912903 | 0.968798 |

| ExtraTrees | 0.916395 | 0.916330 | 0.917540 | 0.916337 | 0.968897 |

| Bagging | 0.936273 | 0.936083 | 0.941200 | 0.936156 | 0.968604 |

| Model | Accuracy± SD | Average rank | Statistical group | Cohen's Kappa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bagging | 93.36 ± 0.22 | 1.0 | A | 0.87 |

| ExtraTrees | 90.76 ± 0.18 | 2.0 | A | 0.83 |

| RandomForest | 90.41 ± 0.18 | 3.0 | B | 0.83 |

| GradientBoosting | 70.72 ± 0.30 | 4.0 | B | 0.42 |

| AdaBoost | 65.15± 0.29 | 5.0 | C | 0.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).