1. Introduction

In the last two decades, trauma training has been increasingly common for people in a range of ’first responder’ and risk-brokering occupations - from policing and ambulance services to law and journalism to help them cope better with ongoing exposure to death, violence, and human suffering and to minimize any subsequent mental health impacts. It has been a period when the news media, finally, had to come to terms with the psychological and physical costs of reporting on disaster, and which saw the establishment of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma research. Meanwhile, calls have mounted for media organizations and universities to offer reporters consistent, systematic, and reflective trauma education even as journalism has become a more dangerous, change-ridden, and precarious line of work [

1].

It’s crucial to remember that the safety of journalists in war zones is a complex issue, as they face many dangers every day. The safety of journalists has increasingly become an international issue within the framework of the United Nations Plan of Action. Based on UNESCO’s Journalists’ Safety Indicators (JSIS), the level of protection for journalists in each country is assessed. The indicators examine the extent of their safety and security, reveal statistics on safety and impunity, and discuss the level of protection by the state, political actors, civil society organizations, academia, the media, mediators, the UN system, and other foreign entities that assist journalists. International NGOs often support local efforts to promote safety, so their presence in Yemen is absent [

2].

Globally, journalism education has changed significantly over the past decade to keep abreast with the profession, which has been through a huge upheaval. The profession is transforming itself to keep relevant with the technological, audience, and business model changes. It also has to deal with declining public trust in journalists and increased threats to both journalists’ safety and media freedom. The challenge for educators and the profession is only just beginning, given the unrelenting pace of change [

3]. Therefore, this study seeks to uncover the levels of media students’ knowledge of occupational safety procedures.

Governments, too, must fulfill their responsibility by providing a safe working environment for journalists. Journalists’ safety and protection are a function of different players. Media houses have a responsibility to protect their staff. Journalists need to understand the hazards and threats that they may face. UNESCO proposed that schools of journalism have a significant role to play in informing such understanding. Universities and journalism education institutions should, therefore, include journalism safety in their curricula. A properly functioning curriculum should contain at least one module that is devoted to the subject [

4].

So, the importance of occupational safety protocols is of paramount significance for media practitioners, considering the numerous physical and psychological hazards they encounter while reporting on various events. Furthermore, media students need to acquire familiarity with these protocols, as they represent the forthcoming cohort of media professionals

1.1. The Problem

Journalists in Yemen face significant professional and psychological challenges. Their objectivity, political affiliations, religious beliefs, and geographical origins make them targets for all parties involved in the conflict. Threats against journalists and their families have resulted in self-censorship and hindered the free circulation of news and information [

5]. Therefore, it is necessary to prepare media students well. The media students must know about occupational safety procedures so that they can understand the risks that a journalist can fall into and how a journalist can avoid those risks. In some countries, a journalist can be thrown in prison for years for a single offending word or photo. Jailing or killing a journalist removes a vital witness to events and threatens the right of us all to be informed. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) fights for press freedom on a daily basis [

6]. Accordingly, this study mainly seeks to measure the extent of knowledge of media students at Yemeni University about occupational safety procedures.

1.2. Objectives of the study

The Objectives of this study are to:

Describe the Yemeni media students’ level of knowledge of occupational safety procedures.

Indicate the Yemeni media students’ knowledge source of occupational safety procedures.

Measure the level of interest of respondents in obtaining information and guidance on occupational safety procedures.

Determine the extent of Yemeni universities’ interest in qualifying respondents in the field of occupational safety.

To emphasize the necessity of incorporating ’the safety and security of journalists’ into the curriculum for both undergraduate and graduate media programs in Yemen.

1.3. Research Questions

This study relies on four main questions:

To what extent is the Yemeni media students’ knowledge of occupational safety procedures?

What are the sources of respondents’ knowledge of occupational safety procedures?

What is the level of the respondents’ interest in obtaining information and guidance on occupational safety procedures?

How are the Yemeni universities interested in qualifying respondents in the field of occupational safety?

1.4. Research Hypotheses

There is a significant difference between the respondents’ knowledge of occupational safety procedures levels according to the variables (gender, respondents’ practice of the media work, and respondents’ education).

There is a correlation between the respondents’ knowledge of occupational safety procedures and (the university’s interest in qualifying researchers in the field of occupational safety - respondents’ practice of the media work - the extent to which respondents follow international press organizations’ social media accounts).

There is a correlation between respondents’ evaluation of the level of risks faced by journalists and (the level of respondents’ regard for occupational safety procedures, respondents’ practice of media work, the extent to which respondents follow international press organizations’ social media accounts).

1.5. Literature Review

The study of [

2] aimed to identify the extent to which Yemeni journalists are aware of the risks of press coverage and how this awareness relates to their adoption of professional safety measures. The study employed the professional practice approach and the theory of diffusion of innovations. The study used the survey method to reach a sample of 307 journalists using the purposive sampling method from among Yemeni journalists practicing the profession. The study found that Yemeni journalists are highly aware of the risks of press coverage, primarily the risks of political and legal intimidation, exposure to danger in war or conflict zones, and confiscation of press tools. However, while they have information about professional safety measures and are moderately aware of the need to adhere to them, their interest in obtaining information about professional safety measures is high. More than half of them adopt professional safety measures that they have previously experienced. However, these measures do not protect journalists from murder, imprisonment, or torture as a primary concern. Identifying reliable contacts was the most important professional safety measure in terms of evaluation and experience. Nearly half of Yemeni journalists do not feel completely safe while practicing their profession. Psychological risks are at the forefront of the risks faced by journalists, although they are also exposed to physical risks to a lesser extent. Journalists described the work environment as both dangerous and hostile, indicating Yemen does not protect journalists or support freedom of the press. This necessitates adherence to professional safety measures at the very least.

The study of [

7] explores journalism students’ responses to hazards and hostility in the profession within a Safety of Journalists course. The research uses focus group interviews, field notes, study diaries, written tasks, and Teams’ chat logs of 11 students. Students’ reactions to the hazards highlight the importance of awareness for finding solutions and developing resilience. Proposed solutions include fostering self-assurance, enhancing interpersonal communication, setting boundaries to prevent burnout, and recognizing the significance of workers’ rights. However, finding some solutions was hindered by students’ experiences of media organizations neglecting worker well-being.

The article of [

8] reflects the perspectives of journalism educators responsible for preparing journalists for careers in the Middle East and North Africa region, which has received little attention in trauma education research. A survey with quantitative and qualitative questions is used to reflect opinions of 101 journalism educators from Algeria, Sudan, and Palestine on journalism trauma-focused education and to elicit their attitudes toward incorporating trauma education into their institutions’ journalism curricula. The findings revealed that journalism educators are particularly cognizant of the role of trauma in journalism practice and the relevance of incorporating trauma education elements into journalism curricula. Journalism educators have identified several barriers to incorporating trauma into their institutions’ journalism curricula, as well as various perspectives on how to incorporate trauma-focused education into journalism curricula, which could call for changing how journalism is taught in their respective institutions. The study establishes a methodological foundation for other scholars to use when investigating triangulation (or the lack thereof) among educators, students, and practitioners in their communities.

The study of [

9] explores the state of education on the topics of abuse and safety toward journalists. As the data indicate that instructors rarely teach about hostility in the classroom, although most feel efficient to do so. Moreover, findings indicate an instructor is more likely to teach about hostility toward the press the more they see it as an issue and have encountered it personally as a journalist-particularly women faculty. Implications for these findings are discussed for journalism schools and their curriculum. And this study explained that Journalistic well-being is garnering increasing attention from scholars globally. Nevertheless, minimal research has explored how colleges and universities are teaching about such topics, especially as they pertain to hostility toward the press, which is on the rise. Utilizing a survey of journalism instructors at ACEJMC-accredited U.S.-based universities.

The study of [

10] explored the challenges faced by the media education and curricula development in Pakistan, and how the safety of journalists is addressed in the courses and curriculum of mass communication in different universities. The study uses a mixed-methods research design, including a quantitative approach through surveys from one hundred and fifty media students from different universities in Pakistan. It further uses a qualitative in-depth interview method in which fifteen media academics are interviewed. The research reveals that the safety of journalists has never been a priority in the curriculum, even if future journalists are hungry to be educated and trained to cover any hostile event, pandemics, and conflict-sensitive reporting, and to cope with post coverage traumas. Safety of journalists has been occasionally discussed in lectures on the request of students, but it can never get a space in the mass communication curriculum. This study lays the foundation of the ESCR Model of Journalism Education that deals with ethics and safety in crisis and risks. It further suggests the training of academics themselves, and collaboration of media professionals with academia to realistically develop a curriculum taking into account what the media industry and future journalists need to mug up.

The study of [

11] aims to measure and analyze the level of knowledge and awareness of students about Occupational Health and Safety (OHS). In this context, the sample of the research is in Turkey; Istanbul Gelisim University, which is a foundation university, and Gaziantep University, which is a state university, consist of the OHS program students. In this way, a comparison between two different types of universities (state and foundation) was provided. Data were collected through a questionnaire created within the scope of the study. The questionnaire consists of demographic questions and questions about the OHS Awareness Scale. As a result of the study, it has been seen that the presence of a laboratory where applied courses can take place at the university where the students receive OHS education and the fact that their parents are employers, positively predict OHS awareness. This situation created the opinion that intra-family dialogues can increase OHS awareness among other family members. This study is important in terms of evaluating the workplace safety culture perspectives that students have about OHS legal practices within the framework of ILO directives and revealing their perspectives on the effectiveness of OHS education.

The paper of [

12] examines the attitudes of journalism educators/trainers toward trauma literacy through a questionnaire survey of 119 journalism educators globally. The findings show that a high percentage of educators have a good understanding of the risks that arise from exposure to critical and potentially traumatizing events, but there are some barriers to teaching trauma, including a lack of knowledge/confidence, resources, time, and teaching materials.

The project of [

13] underscores a need for content to combat hostility within journalism courses. Using in-depth interviews with 28 early career journalists from across the United States, the findings also highlighted a tension between early career journalists’ beliefs about how journalists are supposed to act and how they coped with hostility in practice. This created hesitancy to speak up and have discussions about it. Hastility with editors, especially among women journalists. Therefore, I argue for a shift in how we talk about hostility toward journalists in our classrooms. surrounding the need to prepare journalism students for hostile encounters and harassment are emerging.

The issue of [

12] proposes a new pathway to an educational agenda due to growing evidence of extensive trauma associated with high exposure to traumatizing events, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and maladaptive coping strategies among practicing journalists, the drive to prepare journalism to cope with the emotional and psychological stress of reporting trauma and human suffering has grown significantly among scholars in recent years. In response to this persistent work-related problem in journalism practice.

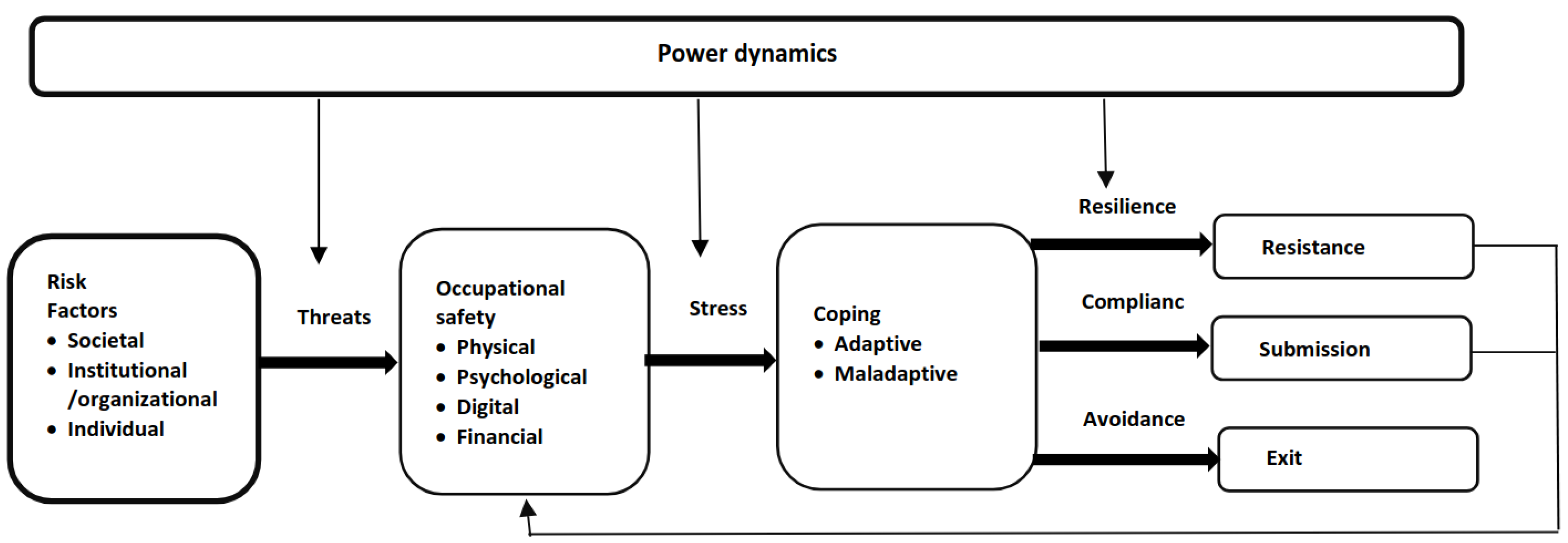

Figure 1.

Journalist’ safety conceptual model [

14].

Figure 1.

Journalist’ safety conceptual model [

14].

The study of [

15] is adding to an established body of research on the interrelationship between journalism and trauma. Syndicate focused on how journalism schools should prepare students to deal with Traumatic news content and events that would undoubtedly form part of their future day-to-day activities. Journalists are not immune to the emotional impact of their work as they report on mass shootings, terror attacks, and natural disasters.

The study of [

16] presented a comprehensive overview of the actual digital dangers and challenges that Egyptian journalists face because of their journalistic work, seeking to clarify to which Egyptian journalists are aware of. About all kinds of digital dangers and their undesirable consequences on professional practices and safety. Based on in-depth interviews with 60 journalists from the different Egyptian newspapers and news sites (partisan, state-owned, and private), and focus group discussions with the journalists, Moreover, how do they combat these dangers in terms of? The study investigates the legal framework that regulates digital media and online communication in Egypt. This study shows that journalists not have enough awareness of the different kinds of digital threats. Journalists need to be more aware of all the digital. Threats besides the regulations to protect themselves and to combat the digital threats. Several journalists could not remove spyware, trojans, or malware. Some of the journalists suffer from blurring and obscurity in defining the digital threats and in dealing with such threats.

The article of [

17] is an overview of the growing concerns about escalating violence. Against journalists in India and a matching lack of interest in the Indian academy to understand the various implications of such violence-both pedagogically and sociologically. The fact that about six journalists were killed in a span of two to three months, September-November 2017, speaks volumes about the magnitude of the problem in India world’s largest democracy that has the largest volume of media presence. By far, the safety and security of journalists was never part of a serious debate among Indian media houses or Indian journalism education, except by way of expressing a symbolic condolence whenever a journalist was killed in action. Although the Indian academy has displayed abject ignorance of this important component of journalists’ training, despite UNESCO proposing a model curriculum for safety of journalists at the university level in 2007, the media industry which runs its media schools in India to train its recruits is never concerned about the safety and security of the journalists. Using the methodology adopted by the Freedom House in its report on Freedom of Press (2016) for determining the varied ways in which the pressure was laid on the objective flow of information, the present study throws light on several dimensions involved in evolving a pedagogy for the ’safety and security of journalists’ from sociological perspectives.

2. Theoretical Framework

UNESCO identifies several key indicators for the safety of journalists. A large array of stakeholders is likely to be interested in the assessment process and should be involved in it in one way or another. This includes: (UN, Other international intergovernmental or non-governmental agencies, promoting journalists’ safety issues; State and political actors, other elected officials, leaders of political parties, human rights commissions, ombudsmen, police forces, military, specialized institutions, public protectors, broadcast and telecom regulators, Civil Society Organizations and academics from journalism education institutions, media trainers; Media actors [

18].

Sound journalism education and training have been identified as a strong contributor to the professional and ethical practice of journalism. Journalism that is well-grounded in training is better suited to provide access to information, foster democracy, dialogue, and overall development in society. Professional news media have been found to better act as custodians of public interest. Most of these are built through journalism education and training and perfected through practice. While the journalism field has provided diverse ranges of skills to students and professionals, it is clear that safety issues have remained behind. There are only a handful of organizations that conduct safety trainings, while learning institutions show glaring gaps when it comes to safety-related courses [

4].

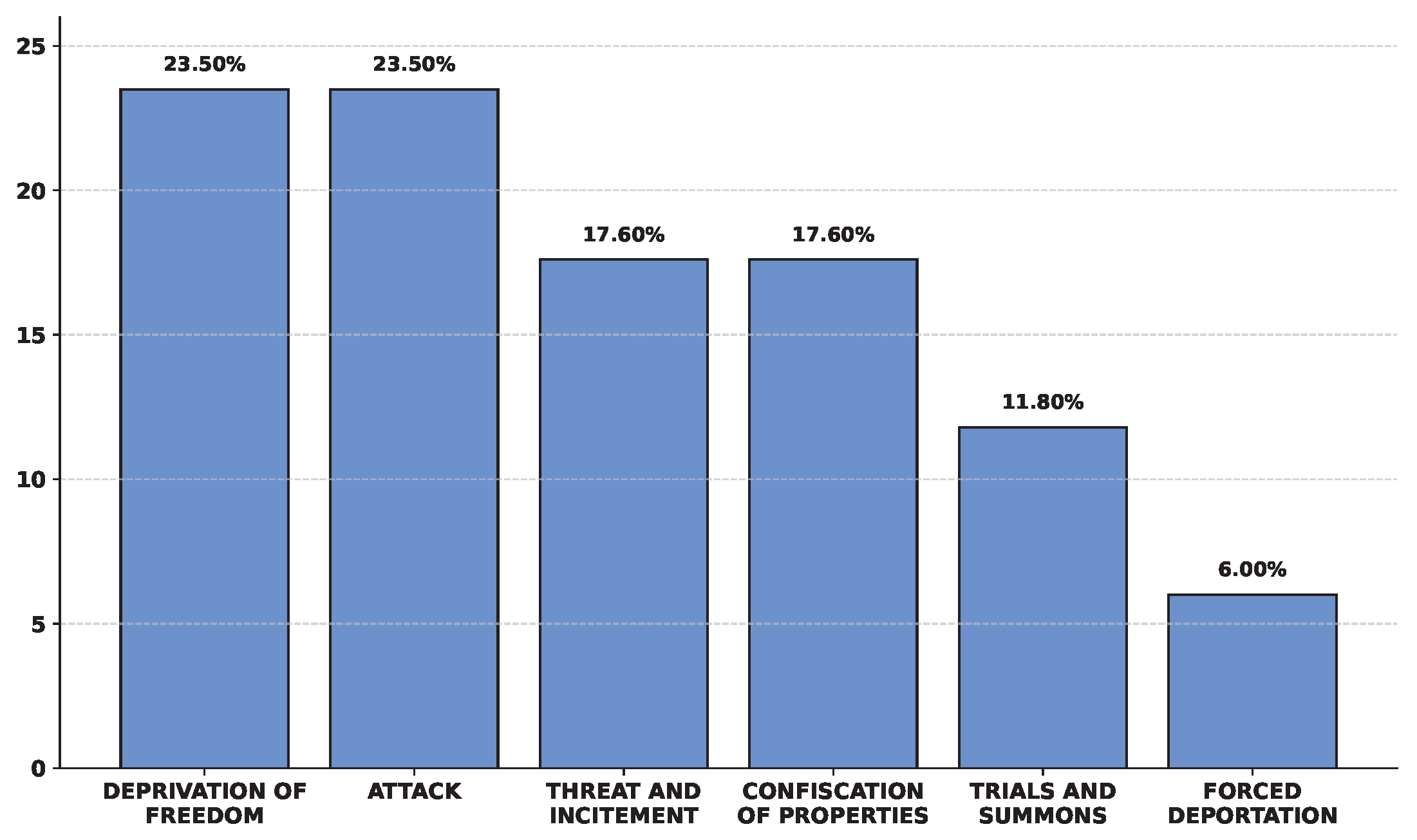

Figure 2.

Type of violation, (UNESCO) [

18].

Figure 2.

Type of violation, (UNESCO) [

18].

The risks to journalists’ safety and security have risen sharply in conflict and non-conflict areas alike in recent years. Organizations representing journalists and news media organizations have to focus more intensively on ensuring the necessary professional skills and defenses to minimize the risks. Many have also engaged in national, regional, and global efforts to achieve stronger protections in law and practice for journalists and their work. The development of highly sophisticated surveillance and tracking, and monitoring technologies poses a new kind of systemic risk to journalists. Journalists should maximize their protections against cyberattacks, cybercrime, surveillance, and interception of their communications. Faced with these risks, journalists, editors, managers, and owners of media houses are well advised to take all possible precautions to reduce the risks to the safety of media workers in conflict zones and other situations of difficulty or danger. That means the best possible preparation in terms of hostile environment and first aid training, personal protection and safety equipment, logistical backup, data and communications security, and insurance. Journalists and employers also need to be well informed, more than ever, about their rights under domestic and international laws, and how to defend and assert those rights in practice [

19].

UNESCO confirmed that those (13) states reported on trainings on the safety of journalists, including Azerbaijan, Colombia, Ghana, Greece, Kyrgyzstan, Mozambique, Myanmar, the State of Palestine, Paraguay, Peru, the Russian Federation, Thailand, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Colombia, for example, reported on a training in 2023 for public servants to improve their understanding of the security issues faced by journalists [

20].

OSCE [

21] identified that violence against journalists takes various forms, including:

Murder and physical assault.

Psychological pressure, including threats to their lives or their relatives.

Unfounded detention during demonstrations or other public events.

Arrests and convictions on trumped-up criminal charges.

Attacks on media property, including vandalism and arson.

Arbitrary police raids on editorial offices and journalists’ homes. (Osce, Safety of journalists: why it matters)

[

14] proposed a comprehensive definition of journalists’ safety built upon an understanding of the range of threats to safety, since safety is mostly considered from the perspective of its absence. They continue by carving out what they diagnose as causes of threats, which they see rooted in power dynamics that play out between journalists and the political elite or specific social groups making claims to power, but also in journalists’ responses and actions when they find themselves in unsafe situations and conditions. Power is the fundamental dynamic that undergirds journalists’ safety. Power manifests in factors that put journalists’ safety at risk, and these factors spawn threats, which in turn lead to stress, coping, self-preservation efforts, and actions. They propose a conceptual model of journalists’ safety as a methodological tool, fig.

Figure 1 in [

14].

2.1. Media Education and Safety Occupation in Yemen

About Yemen, the Yemeni Journalists Syndicate (YJS) released its first 2024 quarterly report on media freedoms in Yemen, documenting. Several violations against journalists and press institutions. The Syndicate documented 17 cases of violations against media personnel and institutions, an indicator that reveals the continuation of a dangerous environment in which Yemeni journalists work without protection [

22].

Following the organization of a training on the Model Course on Safety of Journalists by UNESCO and the IFJ in December 2023 in Cairo, both organizations were informed in September that the University of Saba Region, and the University of Al Mahra had integrated the Media Safety Curriculum into its journalism studies’ education programme at the start of the 2024-2025 academic year (UNESCO).

Table 1.

Weighted mean and its corresponding level.

Table 1.

Weighted mean and its corresponding level.

| Weighted Mean Range |

Level |

| From 1.00 to 1.74 |

None |

| From 1.75 to 2.49 |

Mild |

| From 2.50 to 3.24 |

Moderate |

| From 3.25 to 4.00 |

Severe |

Table 2.

Grading standards and their corresponding correlation degree.

Table 2.

Grading standards and their corresponding correlation degree.

| Grading Standards |

Correlation Degree |

|

No correlation |

|

Very weak |

|

Weak |

|

Moderate |

|

Strong |

|

Very strong |

|

Monotonic correlation |

2.2. Methodology

The current study employed a media survey approach to assess media students’ knowledge of Occupational Safety Procedures, via an online questionnaire that received 167 responses from several Yemeni colleges.

2.3. Statistical Analysis of Data

Analyses were carried out using the SPSS 25.0 statistical package program. Using the following:

Percentage frequency analysis.

Mean and Standard Deviation.

Tests of Normality, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, all measurements (sig. = 0.000), so the distribution of the data is non-normal.

Descriptive analysis techniques.

Test Statistics, a Kruskal-Wallis Test.

Mann-Whitney Test.

Spearman Correlation Coefficient.

3. Results and Discussions

Table 3 presents a comprehensive overview of the respondents’ demographic characteristics. In terms of gender distribution, female students constituted a slightly higher proportion (53.3%) compared to their male counterparts (46.7%). Regarding age, the majority of participants were between 22 and 25 years old (46.7%), followed by those over the age of 25 (35.3%), and the youngest group aged 17 to 21 (18.0%). The educational background of the respondents was predominantly at the bachelor’s level (86.8%), with smaller proportions holding a master’s degree (9.0%), a Ph.D. (3.6%), or a diploma (0.6%). When it comes to academic specialization, most respondents majored in radio and television (58.1%), followed by public relations (27.5%), journalism (12.0%), and a small percentage specialized in mass media (2.4%). As for the type of university attended, a slightly higher percentage of respondents were enrolled in public universities (51.5%) compared to private ones (48.5%). In terms of marital status, a significant majority were single (69.4%), while 24.0% were married with children, and 6.6% were married without children. Finally, concerning economic background, most respondents reported having an average income (79.6%), while 18.0% indicated a low income, and only 2.4% reported a high income.

The results of

Table 4 show that (43.1%) of the respondents learn sometimes online, while (29.9%) of them learn rarely online, and (26.9%) of them learn always online.

According to the data in

Table 5 that (49.1%) of the respondents indicated that the role of university education in preparing the student for the labor market is Intermediate, (38.3%) of them believe that the role of university education is weak, and (12.6%) of them indicated that the role of university education in preparing the student for the labor market is big.

Furthermore, the results of the

Table 6 indicate that (66.5%) of the respondents assessed the level of risks to which journalists in Yemen are exposed to high risk as a result of their work, while (29.3%) of them indicated that journalists are exposed to moderate risks, and a limited percentage of (4.2%) of the respondents believed that journalists are exposed to low risks.

Additionally, results in

Table 7 reveal that the respondents’ sources of knowledge regarding occupational safety procedures in the media field were diverse. A majority, 74.3%, reported that their knowledge stemmed from anticipation and a sense of security. Additionally, 71.3% indicated that the Internet was a primary source of information, while 67.1% cited university studies as another key source. Experience and expertise were identified by 64.1% of the respondents as significant sources of knowledge. Training courses contributed to 49.1% of respondents’ understanding, and lastly, 43.7% referred to journalists’ safety and security guidelines as a source of information.

On the other hand, the results of

Table 8 indicate the levels of knowledge of the respondents regarding occupational safety procedures in the media field vary, as (50.9%) of the respondents had a medium level of knowledge of occupational safety procedures in the media field, while (27.5%) of them had a weak level, (12.0%) of them confirmed that they had (no knowledge), while (9.6%) of them had a high level of knowledge of occupational safety procedures. Moreover,

Table 9 explores that (64.7%) of the respondents indicated that they practice the media work, while (35.3%) of them do not practice any media work.

According to the data in

Table 10, the media work practiced by some of the respondents varied, as (24.1%) of the respondents work as (photographers), (18.5%) of them work as writers, (11.1%) of the respondents work as editors, and (7.4%) of them work as (reporters), and (38.9%) of them work within other categories as (monterrey, graphic designer, director, TV producer, and content creator).

The results of

Table 11 confirm that (65.7%) of the respondents who practice the media work adhere medium extent to occupational safety procedures, while (27.8%) of them adhere to a large extent to those procedures, and (6.5%) of them do not adhere to any occupational safety procedures.

Moreover, results of

Table 12 show that the level of interest of (52.7%) of the respondents was highly interested in obtaining information and guidance on occupational safety procedures, while (40.7%) of them were moderately interested, and (6.6%) of them were lowly interested. Furthermore, the data in

Table 13 indicate that 81.4% of the respondents believe that adherence to occupational safety procedures is important, while 18.6% of them consider adherence to occupational safety procedures to be somewhat important.

The data in

Table 14 show that (41.9%) of the respondents believe that their universities do not care about their qualifying in the field of occupational safety, while (24.0%) of them indicated that their universities have low care, (23.4%) of them indicated that their universities care about their qualifying in that field medium, and (10.8%) of them explained that their universities care about their qualifying in that field (large).

According to the results presented in

Table 15 15, respondents identified multiple reasons for some universities’ lack of interest in training students in the field of occupational safety. Foremost among these is the lack of capabilities, cited by 73.1% of respondents. Additionally, 72.5% attributed this lack of interest to outdated educational curricula and a general lack of awareness regarding the importance of teaching occupational safety.

Table 16 presents the various forms of university interest in qualifying respondents in the field of occupational safety. A total of 42.5% of respondents reported that their universities offer “occupational safety” as a formal subject within the curriculum. Additionally, 35.9% stated that their universities dedicate lectures within certain courses to occupational safety topics. Meanwhile, 24.0% indicated that their universities publish journalists’ safety and security guidelines on the university website. Furthermore, 20.4% noted that their institutions either provide occupational safety accreditation courses or conduct relevant training programs. Lastly, 16.8% of respondents mentioned that their universities distribute occupational safety tools and equipment to students actively engaged in professional practice.

The results presented in

Table 17 indicate that respondents’ levels of knowledge regarding occupational safety procedures vary, with an overall moderate rating and an average score of 2.67. Specifically, the procedure of carrying identity documents and wearing a jacket marked “press” or “TV” received a moderate rating with an average of 2.95. Similarly, avoiding the carrying of weapons was rated at 2.92, and identifying trusted contacts averaged 2.73. Knowledge of procedures such as obtaining permission from the Ministry of Defense when covering events and securing accommodation during coverage both received an average of 2.72. Backing up personal documents via email followed closely with an average score of 2.69. Coordination and communication with Yemeni, Arab, or international syndicates, along with keeping emergency numbers stored in one’s phone, were both rated at 2.64. Knowledge of keeping first aid supplies averaged 2.62, while selecting appropriate support staff, such as a local broker or driver, received a score of 2.60. Wearing a helmet, jacket, and gas mask was rated slightly lower, at 2.55, and the use of incognito browsing and data protection averaged 2.53. Respondents rated knowledge of life and risk insurance provided by press foundations at 2.48, while activating the GPS was rated 2.46. The lowest-rated procedure was preparing survival essentials, such as water purification tablets, a survival blanket, dried food, and a door barrier, which received an average of 2.36.

Furthermore, the results in

Table 18 (52.1%) of the respondents confirmed that they first learned about occupational safety for journalists at the undergraduate level, while (35.9%) of them only learned about the occupational safety of journalists through this questionnaire, (34.1%) of them learned about the occupational safety of journalists before undergraduate studies, and (15.6%) of them indicated that they learned about it during graduate studies. Moreover, the data in

Table 19 show that 60.5% of the respondents did not read at least one guide on occupational safety in the media field, while 39.5% of them read at least one guide on occupational safety in the media field.

In addition, results in

Table 20 show that (30.5%) of the respondents follow (sometimes) the accounts of international press organizations on social media sites, while (28.1%) of them do not follow those accounts, while some respondents follow those accounts (rarely) and (always) at two rates of (23.4%) and (18.0%) for each of them, respectively.

According to the data in

Table 21, 83.8% of the respondents indicated that they did not subscribe to the service of receiving messages from international press organizations in their email, while (13.2%) of the respondents subscribed to that service. Furthermore, the data in

Table 22 explain that 83.8% of the respondents indicated that media students in Yemeni universities need to highly adopt a course on occupational safety, and 12.6% of the respondents believe that media students need to moderately adopt a course on occupational safety, while 2.4% of the respondents believe that media students need to lowly adopt a course on occupational safety, and a limited percentage of the respondents, amounting to (1.2%), believe that media students do not need any course on occupational safety. Moreover, the results of

Table 23 show no significant differences by gender (Mann-Whitney U (3298.000) = 0.01; p>0.05). Knowledge of occupational safety procedures levels between female and male students is similar.

According to the results of

Table 24 confirm that the differences are significant by respondents’ practice of the media work (Mann-Whitney U (2055.500) = 0.01; p<0.05). Knowledge of occupational safety procedures levels of the students who practice media work is significantly higher. Moreover, the results of

Table 25 show significant differences by respondents’ education (Kruskal-Wallis H (8.829) = 0.01; p<0.05). Knowledge of occupational safety procedures levels of the students who practice media work is significantly higher. To know the differences significantly by respondents’ education, we used the Mann-Whitney test in

Table 28.

The results of

Table 26 show a correlation between respondents’ knowledge of occupational safety procedures and the university’s interest in qualifying researchers in the field of occupational safety, the correlation coefficient = 0.162*. There is a correlation between respondents’ knowledge of occupational safety procedures and respondents’ practice of the media work, the correlation coefficient = 0.324*. And there is a correlation between respondents’ knowledge of occupational safety procedures and the extent to which respondents follow international press organizations’ social media accounts, the Correlation Coefficient = 0.412*.

On the other side, the results of

Table 27 show a correlation between respondents’ evaluation of the level of risks faced by journalists and the level of respondents’ knowledge regarding occupational safety procedures; the correlation coefficient = 0.190*. And there is a correlation between respondents’ evaluation of the level of risks faced by journalists and the extent to which respondents follow international press organizations’ social media accounts; the correlation coefficient = 0.169*.

Additionally, the results of

Table 28 show significant differences by respondents’ education between Bachelor and Master (= 0.01; p<0.05). Knowledge of occupational safety procedures levels of the students who are masters is significantly higher.

Table 28.

Pairwise Mann-Whitney test results for differences in knowledge of occupational safety procedures between education levels (n = 167). The results show significant differences between Bachelor and Master groups (p = 0.011, p < 0.05).

Table 28.

Pairwise Mann-Whitney test results for differences in knowledge of occupational safety procedures between education levels (n = 167). The results show significant differences between Bachelor and Master groups (p = 0.011, p < 0.05).

| |

Education Level |

| Education Level |

Bachelor |

Master |

Ph.D. |

| Diploma |

0.640 |

0.124 |

0.270 |

| Bachelor |

– |

0.011* |

0.117 |

| Master |

– |

– |

0.759 |

4. Recommendations

To better educate media students for the demands of today’s labor market, institutions should take a more proactive approach to incorporating occupational safety principles into their curricula. By incorporating practical modules that imitate real-world reporting circumstances, institutions can raise awareness of workplace dangers and provide students with the techniques they need to negotiate potentially harmful tasks. This curriculum update not only improves technical competency but it also instills a strong safety mindset that is consistent with industry standards.

It is also critical that media students obtain thorough information about the occupational risks that journalists face daily. Reporting in hazardous areas and documenting horrific events can pose dangers, including psychological stress. Universities and media training institutes should provide evidence-based risk evaluations, case studies, and expert analyses to help students comprehend the potential hazards. This knowledge base will support educated decision-making in the field.

To ensure continuous access to authoritative advise on workplace safety, media programs must give curated sources of knowledge about occupational safety protocols in the journalism industry. This can include annotated bibliographies of peer-reviewed literature, subscriptions to specialized safety publications, and dedicated websites managed by professional societies. By centralizing these resources, educational institutions can create a dynamic repository where students can stay up to date on developing best practices and regulatory changes.

Another important aspect of a good safety framework is the development of professional skills among media students. Beyond technical reporting skills, students should be trained in situational awareness, risk assessment approaches, and crisis communication techniques. Workshops provided by experienced journalists, safety officials, and legal experts can help students improve their pre-assignment planning and respond effectively to safety problems during fieldwork.

To supplement theoretical teaching, the provision of simple yet comprehensive guidelines to occupational safety measures is recommended. These instructions, whether pocket-sized manuals or digital quick-reference sheets, should define step-by-step processes for typical scenarios like angry crowd interactions, hazardous material contacts, and medical emergencies. When reporting under time limits, students can quickly examine critical procedures because they have easy access to such resources.

Furthermore, academic institutions should provide formal occupational safety qualification tracks that are specifically geared to media practitioners. By providing certificate courses or validated credentials, colleges confirm their graduates’ ability to apply safety concepts. Such qualifications increase media students’ employability and demonstrate to prospective employers that they have proven skills in risk management.

Encouraging media students to follow the social media accounts of international press organizations is an extra way to raise safety awareness. Reputable outlets use social media platforms like Twitter and LinkedIn to provide real-time safety updates, field reports, and multimedia briefings. By engaging with these platforms, students can learn about current risks and the preventative measures taken by leading media institutions.

Subscribing to official communications from worldwide press organizations, such as email newsletters, professional journals, or membership portals, enhances digital involvement and gives a comprehensive awareness of global safety standards. These subscriptions provide students access to white papers, investigative reports, and recommendations developed by specialists in press freedom and journalist protection, thereby expanding their contextual knowledge and preparation.

To institutionalize these safety concepts, academic schools should offer occupational safety courses in journalism. Courses could address issues such as digital security, equipment safety, and ethical considerations in high-risk reporting, with practical examinations to imitate real-life events. Including these courses as mandatory prerequisites emphasizes the importance of safety in the media curriculum.

Finally, media institutions must provide students who engage in professional practice with the necessary occupational safety equipment. This includes providing safety equipment such as helmets, body armor, first-aid kits, and secure communication devices. Institutions demonstrate a concrete commitment to protecting young journalists as they transition from academic training to professional situations by providing them with the practical resources they need for safe fieldwork.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the respondents (n = 167).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the respondents (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Gender |

|

| Male |

78 (46.7%) |

| Female |

89 (53.3%) |

| Age |

|

| 17–21 |

30 (18.0%) |

| 22–25 |

78 (46.7%) |

| +25 |

59 (35.3%) |

| Education |

|

| Diploma |

1 (0.6%) |

| Bachelor |

145 (86.8%) |

| Master |

15 (9.0%) |

| Ph.D. |

6 (3.6%) |

| University Major |

|

| Journalism |

20 (12.0%) |

| Radio & Television |

97 (58.1%) |

| Public Relationship |

46 (27.5%) |

| Mass Media |

4 (2.4%) |

| Type of University |

|

| State |

86 (51.5%) |

| Private |

81 (48.5%) |

| Marital Status |

|

| Single |

116 (69.4%) |

| Married |

11 (6.6%) |

| Divorced |

40 (24.0%) |

| Standard of Living |

|

| Low income |

30 (18.0%) |

| Average income |

133 (79.6%) |

| High income |

4 (2.4%) |

Table 4.

Online learning frequency of the respondents (n = 167).

Table 4.

Online learning frequency of the respondents (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Online Learning |

|

| Always |

42 (26.9%) |

| Sometimes |

72 (43.1%) |

| Rarely |

50 (29.9%) |

Table 5.

Respondents’ evaluation of the role of university education in preparing students for the labor market (n = 167).

Table 5.

Respondents’ evaluation of the role of university education in preparing students for the labor market (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Role of University Education |

|

| Weak Role |

64 (38.3%) |

| Intermediate Role |

82 (49.1%) |

| Big Role |

21 (12.6%) |

Table 6.

Respondents’ evaluation of the level of risks faced by journalists in Yemen as a result of their work (n = 167).

Table 6.

Respondents’ evaluation of the level of risks faced by journalists in Yemen as a result of their work (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Level of Risk |

|

| High Risk |

111 (66.5%) |

| Medium Risk |

49 (29.3%) |

| Low Risk |

7 (4.2%) |

Table 7.

Sources of respondents’ knowledge regarding occupational safety procedures in the media field (n = 167).

Table 7.

Sources of respondents’ knowledge regarding occupational safety procedures in the media field (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Sources of Knowledge |

|

| Work Experience |

107 (64.1%) |

| University Study |

112 (67.1%) |

| Online |

119 (71.3%) |

| Training Courses |

82 (49.1%) |

| Journalists’ Safety and Security Guidelines |

73 (43.7%) |

| Anticipation and Sense of Security |

124 (74.3%) |

Table 8.

Level of respondents’ knowledge regarding occupational safety procedures in the media field (n = 167).

Table 8.

Level of respondents’ knowledge regarding occupational safety procedures in the media field (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Level of Knowledge |

|

| High Knowledge |

16 (9.6%) |

| Medium Knowledge |

85 (50.9%) |

| Low Knowledge |

46 (27.5%) |

| I Have No Knowledge |

20 (12.0%) |

Table 9.

Respondents’ practice of media work (n = 167).

Table 9.

Respondents’ practice of media work (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Practice of Media Work |

|

| Yes |

108 (64.7%) |

| No |

59 (35.3%) |

Table 10.

Media work practiced by the respondents (n = 108).

Table 10.

Media work practiced by the respondents (n = 108).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Media Work Practiced |

|

| Editor |

12 (11.1%) |

| Correspondent |

8 (7.4%) |

| Photographer |

26 (24.1%) |

| Writer |

20 (18.5%) |

| Others |

42 (38.9%) |

Table 11.

Level of respondents’ commitment to occupational safety procedures (n = 108).

Table 11.

Level of respondents’ commitment to occupational safety procedures (n = 108).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Commitment to Occupational Safety |

|

| Large Extent |

30 (27.8%) |

| Medium Extent |

71 (65.7%) |

| No Commitment |

7 (6.5%) |

Table 12.

The level of interest of respondents in obtaining information and guidance on occupational safety procedures (n = 167).

Table 12.

The level of interest of respondents in obtaining information and guidance on occupational safety procedures (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Interest in Occupational Safety Information |

|

| Low |

11 (6.6%) |

| Medium |

68 (40.7%) |

| High |

88 (52.7%) |

Table 13.

Respondents’ evaluation of the importance of adherence to occupational safety procedures (n = 167).

Table 13.

Respondents’ evaluation of the importance of adherence to occupational safety procedures (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Importance of Adherence to Safety Procedures |

|

| Important |

136 (81.4%) |

| To Some Extent |

31 (18.6%) |

| Unimportant |

0 (0.0%) |

Table 14.

The extent of the university’s interest in qualifying the researchers in the field of occupational safety (n = 167).

Table 14.

The extent of the university’s interest in qualifying the researchers in the field of occupational safety (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| University’s Interest in Qualification |

|

| Large |

18 (10.8%) |

| Medium |

39 (23.4%) |

| Low |

40 (24.0%) |

| No Interest |

70 (41.9%) |

Table 15.

Reasons for the university’s lack of interest in qualifying respondents in the field of occupational safety (n = 167).

Table 15.

Reasons for the university’s lack of interest in qualifying respondents in the field of occupational safety (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Reasons for Lack of Interest |

|

| Old Educational Curricula |

121 (72.5%) |

| Lack of Capabilities |

122 (73.1%) |

| Lack of Awareness of the Importance of Teaching Occupational Safety |

121 (72.5%) |

Table 16.

The university’s interest in qualifying researchers in the field of occupational safety (n = 167).

Table 16.

The university’s interest in qualifying researchers in the field of occupational safety (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Forms of University Interest |

|

| Occupational safety accreditation course |

34 (20.4%) |

| Teaching occupational safety as a subject within a curriculum |

71 (42.5%) |

| Conducting training courses in occupational safety |

34 (20.4%) |

| Publishing journalists’ safety and security guides on the university website |

40 (24.0%) |

| Allocating lectures in some courses on occupational safety |

60 (35.9%) |

| Distribution of occupational safety tools and equipment to students |

28 (16.8%) |

Table 17.

Level of respondents’ knowledge of occupational safety procedures (n = 167).

Table 17.

Level of respondents’ knowledge of occupational safety procedures (n = 167).

| Item |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Level |

| Wear a helmet, vest and gas mask |

2.55 |

1.175 |

Moderate |

| Life and risk insurance by the press foundation |

2.48 |

1.171 |

Mild |

| Obtaining permission from the Ministry of Defense when covering wars |

2.72 |

1.245 |

Moderate |

| Carry identity documents and wear a jacket with a sign “press” or “TV” |

2.95 |

1.211 |

Moderate |

| Don’t carry a weapon |

2.92 |

1.207 |

Moderate |

| Coordination and communication with the Yemeni, Arab, or international syndicate |

2.64 |

1.188 |

Moderate |

| Securing accommodation during coverage |

2.72 |

1.170 |

Moderate |

| Selecting the support staff (local broker, driver …) |

2.60 |

1.188 |

Moderate |

| Identify trusted contacts |

2.73 |

1.159 |

Moderate |

| Activate GPS system |

2.46 |

1.226 |

Mild |

| Use incognito browsing and data protection |

2.53 |

1.221 |

Moderate |

| Bring water purification tablets, survival blanket, dried food, a barrier to prevent the door from being pushed in, … |

2.36 |

1.248 |

Mild |

| Keep first aid supplies |

2.62 |

1.205 |

Moderate |

| Keep emergency numbers on your phone |

2.64 |

1.193 |

Moderate |

| Back up personal documents to email |

2.69 |

1.177 |

Moderate |

Table 18.

Educational level at which respondents first learned about occupational safety for journalists (n = 167).

Table 18.

Educational level at which respondents first learned about occupational safety for journalists (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Educational Level of First Exposure |

|

| to Safety Knowledge |

|

| Before Undergraduate Studies |

57 (34.1%) |

| Undergraduate Level |

87 (52.1%) |

| Postgraduate Studies |

26 (15.6%) |

| First Time Learning About It |

60 (35.9%) |

Table 19.

Respondents’ reading at least one guide on occupational safety in the media field (n = 167).

Table 19.

Respondents’ reading at least one guide on occupational safety in the media field (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Reading Occupational Safety Guides |

|

| Yes |

66 (39.5%) |

| No |

101 (60.5%) |

Table 20.

The extent to which respondents follow international press organizations’ social media accounts (n = 167).

Table 20.

The extent to which respondents follow international press organizations’ social media accounts (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Following International Press |

|

| Organizations on Social Media |

|

| Always |

30 (18.0%) |

| Sometimes |

51 (30.5%) |

| Rarely |

39 (23.4%) |

| Never |

47 (28.1%) |

Table 21.

The extent to which respondents subscribe to the service of receiving messages from international press organizations via email (n = 167).

Table 21.

The extent to which respondents subscribe to the service of receiving messages from international press organizations via email (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Subscription to Email Messages from |

|

| International Press Organizations |

| Yes |

22 (13.2%) |

| No |

140 (83.8%) |

Table 22.

The extent to which media students in Yemeni universities need to adopt a course on occupational safety (n = 167).

Table 22.

The extent to which media students in Yemeni universities need to adopt a course on occupational safety (n = 167).

| Item |

Percentage |

| Need for Occupational Safety Course |

|

| High |

140 (83.8%) |

| Medium |

21 (12.6%) |

| Low |

4 (2.4%) |

| No |

2 (1.2%) |

Table 23.

Mann-Whitney test results to determine the differences between the respondents of their knowledge of occupational safety procedures levels according to gender (n = 167).

Table 23.

Mann-Whitney test results to determine the differences between the respondents of their knowledge of occupational safety procedures levels according to gender (n = 167).

| Gender |

Mann-Whitney U |

P |

Mean Rank |

N |

| Male |

3298.000 |

0.546 |

86.22 |

78 |

| Female |

82.06 |

89 |

Table 24.

Mann-Whitney test results for differences in knowledge of occupational safety procedures according to media work practice (n = 167).

Table 24.

Mann-Whitney test results for differences in knowledge of occupational safety procedures according to media work practice (n = 167).

| Practice of |

Mann- |

|

Mean |

|

| Media Work |

Whitney U |

P |

Rank |

N |

| Don’t work |

2055.500 |

0.000 |

64.84 |

59 |

| Work |

94.47 |

108 |

Table 25.

Kruskal-Wallis test results for differences in knowledge of occupational safety procedures according to education level (n = 167).

Table 25.

Kruskal-Wallis test results for differences in knowledge of occupational safety procedures according to education level (n = 167).

| Education Level |

Kruskal-Wallis H |

p |

Mean Rank |

N |

| Diploma |

8.829 |

0.032 |

56.50 |

1 |

| Bachelor |

80.16 |

145 |

| Master |

112.00 |

15 |

| Ph.D. |

111.33 |

6 |

Table 26.

Spearman’s correlation results between knowledge of occupational safety procedures and related variables (n = 167). * indicates statistically significant correlation (p < 0.05).

Table 26.

Spearman’s correlation results between knowledge of occupational safety procedures and related variables (n = 167). * indicates statistically significant correlation (p < 0.05).

| Variable |

Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient |

| The university’s interest in qualifying researchers in the field of occupational safety |

0.162* |

| Respondents’ practice of the media work |

0.324* |

| The extent to which respondents follow international press organizations’ social media accounts |

0.412* |

Table 27.

Spearman’s correlation results between evaluation of risks faced by journalists and related variables (n = 167). * indicates statistically significant correlation (p < 0.05).

Table 27.

Spearman’s correlation results between evaluation of risks faced by journalists and related variables (n = 167). * indicates statistically significant correlation (p < 0.05).

| Variable |

Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient |

| Level of respondents’ knowledge regarding occupational safety procedures |

0.190* |

| Respondents’ practice of the media work |

0.101 |

| The extent to which respondents follow international press organizations’ social media accounts |

0.169* |