1. Introduction

Current anticancer treatments are, still today, insufficient because of the heterogeneity of the tumor or the drug resistance, leading to frequent relapses [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. To improve therapeutic efficacy and minimize side effects, current treatment options are encapsulation of anticancer drugs in therapeutic vectors that have been extensively studied [

8,

9,

10,

11]. An emerging solution lies in Pickering nanoemulsions, consisting in nano-emulsions stabilized by nanoparticles, used as a drug delivery system. Pickering nano-emulsions herein studied are composed of parenteral-grade lipid and biocompatible lipid nanoparticles, i.e. surfactant free, in order to maximize the physiological tolerance. The use of Pickering nano-emulsions has several advantages, including non-use of organic solvent, large scale production capacity, high bioavailability, protection against degradation of agents such as water and light, and better controlled release of the drug [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. These nano-emulsions stabilized by solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) can be considered as a particular type of nano-emulsion neither with the use of large amount of surfactants, nor with inorganic nanoparticles (since solid lipid used are also biocompatible). In general, many studies have shown the stabilization of nanoemulsions by colloidal particles giving Pickering nanoemulsion. Herein we propose a new generation of safe, non-toxic, biocompatible and surfactant-free nano-platform based on Pickering nano-emulsions [

14,

15,

16,

17], using several types of stabilizing particles [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

The main objective of this work is to study Pickering nanoemulsions stabilized by solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs), with the additional advantage of a temperature sensitivity triggering the nano-emulsion destabilization and drug release, due to the SLNs phase transition [

14]. SLNs are typically made up of physiological lipids that are biodegradable, non-toxic, and have a strong dispersibility in aqueous medium and offer simple and scalable preparation methods. In this study, nano-emulsions stabilized by SLNs were formulated, and an investigation was led regarding on the in vitro digestion in the gastric phase and the intestinal phase. In parallel, complementary nano-emulsion characterizations of the phase behavior were carried out by differential scanning calorimetry. A last part investigated, dealt with in vivo studies on a healthy and three different cancerous cell lines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Suppocire® C (mixture of mono-, di- and triglyceride esters of fatty acids, C10 to C18) purchased from Cooper (Melun, France) and Kolliphor® HS15 (mixture of free polyethylene glycol 660 and 12-hydroxystearate of polyethylene glycol 660) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Quentin Fallavier, France) were used. Labrafac® WL 1349 (MCT, Gattefossé S.A., Saint-Priest, France) was used as the oil phase for the formulation of Pickering emulsions. It is made up of medium chain triglycerides. It is a mixture of caprylic and capric acid triglycerides. Both for the formulation of the SLNs and for that of the nanoemulsion we used MilliQ water was obtained from a Millipore Super-Q unit C79625 All ingredients used were of analytical grade and as received.

2.2. Methods

The formulation of the SLNs by spontaneous emulsification, and Pickering nano-emulsion by ultrasonication was followed as described in previous reports [

14,

15,

16,

17], and briefly described below.

2.2.1. Formulation of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs)

Kolliphor® HS15 and Suppocire® Care are mixed and melted at a temperature of 90°C. The aqueous phase (MilliQ water) is also heated at same temperature. The two phases are mixed and the nanoemulsions form spontaneously. The nanoemulsion is cooled to room temperature for one hour to allow the solidification of the droplets. The washing of the SLNs is carried out by dialysis in milliQ water. We put the suspension of SLNs in the dialysis tubes in 8–12 kDa porous dialysis tubes and immersed in MilliQ water with constant stirring at 300 rpm for 48 hours, changing the water after 24 hours.

2.2.2. Formulations of Pickering Nano-Emulsions

After washing the suspension of SLNs, the dialysate obtained is used as aqueous phase and the particles of SLNs in suspension as sole stabilizer of the nanoemulsions. The volume fraction of dispersed phase is 20%. A first emulsion is made using an Ultraturax shaker (IKA T-25 Digital) operating at 22,400 rpm for 3 min, in ice bath. The resulting emulsion is homogenized by ultrasonication (power = 150 W, 20 kHz, cycles of 10 seconds “on” / 20 seconds “off”, total time = 3 min, in ice bath). The nanoemulsions (O/W) obtained are then stored at 4°C until analysis.

2.3. SLN and Pickering Nanoemulsion Characterization

2.3.1. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

Thanks to a NanoZS Malvern apparatus (Malvern, Orsay, France) we determined the size distribution and the polydispersity index by dynamic light scattering (DLS). The helium/neon laser, 4 mW, was operated at 633 nm, with the scatter angle fixed at 173°. DLS data were analyzed using a cumulant-based method. The temperature is maintained at 25 °C and the measurements were done in triplicate.

2.3.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

TEM observations are made at a voltage lower than that usually used in materials science to avoid any oil vaporization due to the electron beam in the TEM chamber. A Philips Morgagni 268D microscope operating at 70 KV was used for this purpose. The experiment is performed without any coloring agent. A drop of the suspension was placed on the carbon grid (carbon type-A, 300 mesh, copper, Inc. Redding, PA) and drying carried out at room temperature. Under such conditions lipids gave significant contrast.

2.3.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was conducted on TA DSC Q200. The samples were equilibrated at 20°C for 30 min. Indium standard was used to calibrate the DSC temperature and enthalpy scale. The powder samples were hermetically sealed in aluminum pans and heated at a constant rate of 10 °C/min, over a temperature range of 20–170 °C. Inert atmosphere was maintained by purging nitrogen at the flow rate of 15.8 mL/min, linear velocity 35 cm/sec and pressure 24.7 kPa.

The TA DSC Q200 allowed us to carry out the differential scanning calorimetry studies. The indium standard was used to calibrate the DSC temperature and enthalpy scale. We seal the powder samples in aluminum trays and heating is performed at a constant rate of 10°C/min, over a temperature range of 20–170°C. Inert atmosphere was maintained by purging nitrogen at the flow rate of 15.8 mL/min, linear velocity 35 cm/sec and pressure 24.7 kPa.

2.4. In Vitro Digestion Test

Each nano-emulsion underwent a three-step in vitro digestion model simulating gastric and small intestine digestion. The particle size and charge of the samples were measured after incubation in each stage. Simulated gastric fluid (SGF) was prepared by dissolving NaCl (2 g) and HCl (7 mL) in water (total 1 L volume), then the pH was adjusted to 1.2 [

24], [

25]. The simulated intestinal fluid (SSIF) contained 2.5 mL pancreatic lipase solution (60 mg, PBS), 3.5 mL bile extract solution (187.5 mg, PBS, pH 7.0, 37 °C) and 1.5 mL salt solution (0.5 M CaCl2 and 5.6 M NaCl in water).

2.4.1. Gastric Phase

Simulated gastric fluid (SGF, 20 mL) was added to the sample (20 mL) from the mouth phase. The pH was adjusted to 1.2, and the mixture was then incubated for 2 h (37 °C, 100 rpm) under agitation.

2.4.2. Small Intestinal Phase

The sample (30 mL) obtained from the gastric phase was incubated in a water bath to maintain it at 37 °C. The pH was then adjusted to 7.0. Bile extract and salt solutions were added into the sample. The resulting mixture was re-adjusted to pH 7.0, and then pancreatic lipase solution was added.

2.5. Cells Culture

U-87 (ATCC HTB-14), MG63 (ATCC CRL1427), A-549 (ATCC CCL-185) and MSC-2 (respectively glioblastoma, osteosarcoma and lung tumour cell lines) were purchased from ATCC and used for the in vitro biological evaluation. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Growth Medium MSC-2 was purchased from PromoCell, Heidelberg, Allemagne. All the cell handling procedures were performed in sterile conditions under a laminar flow hood, and the cells were grown in a controlled atmosphere at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and humidity conditions. Cells were detached from culture flasks by trypsinization, centrifuged, and resuspended in an appropriate volume of cell culture media to perform a Trypan Blue Dye Exclusion test to assess cell viability and to count the cells.

1 ml vials containing 1x106 cells are defrosted. About 500,000 cells of each line were seeded in a T75 flask. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a water saturated atmosphere at 5% CO2. They are cultivated 3-4 days until they reach 80% confluence while changing the environment regularly. When the cells have reached confluence, they are harvested with trysine. The flasks are out of the incubator, and we add 6ml of culture medium to inactivate trypsin. The content is transferred to a 50ml Falcon tube. Finally, the tube is centrifuged and the cell pellet is recovered.

2.6. Cells Viability

Cell viability tests are performed using a healthy cell line MSC-2 and 3 MG-63 cancer cell lines; A549 and U87. The cells are treated with the suspension dilutions of NE-SLNs (1: 100, 1: 1000, 1: 10000), 24-72h before performing the alamard Blue cytotoxicity assay. 1/10 of the volume of reagent is directly added to the cells of the culture medium. The cells are then incubated for one to four hours at 37 °C in a cell culture incubator protected from direct light. The results are recorded using fluorescence. The fluorescence excitation wavelength is 540-570 nm and the emission wavelength is 580-610 nm.

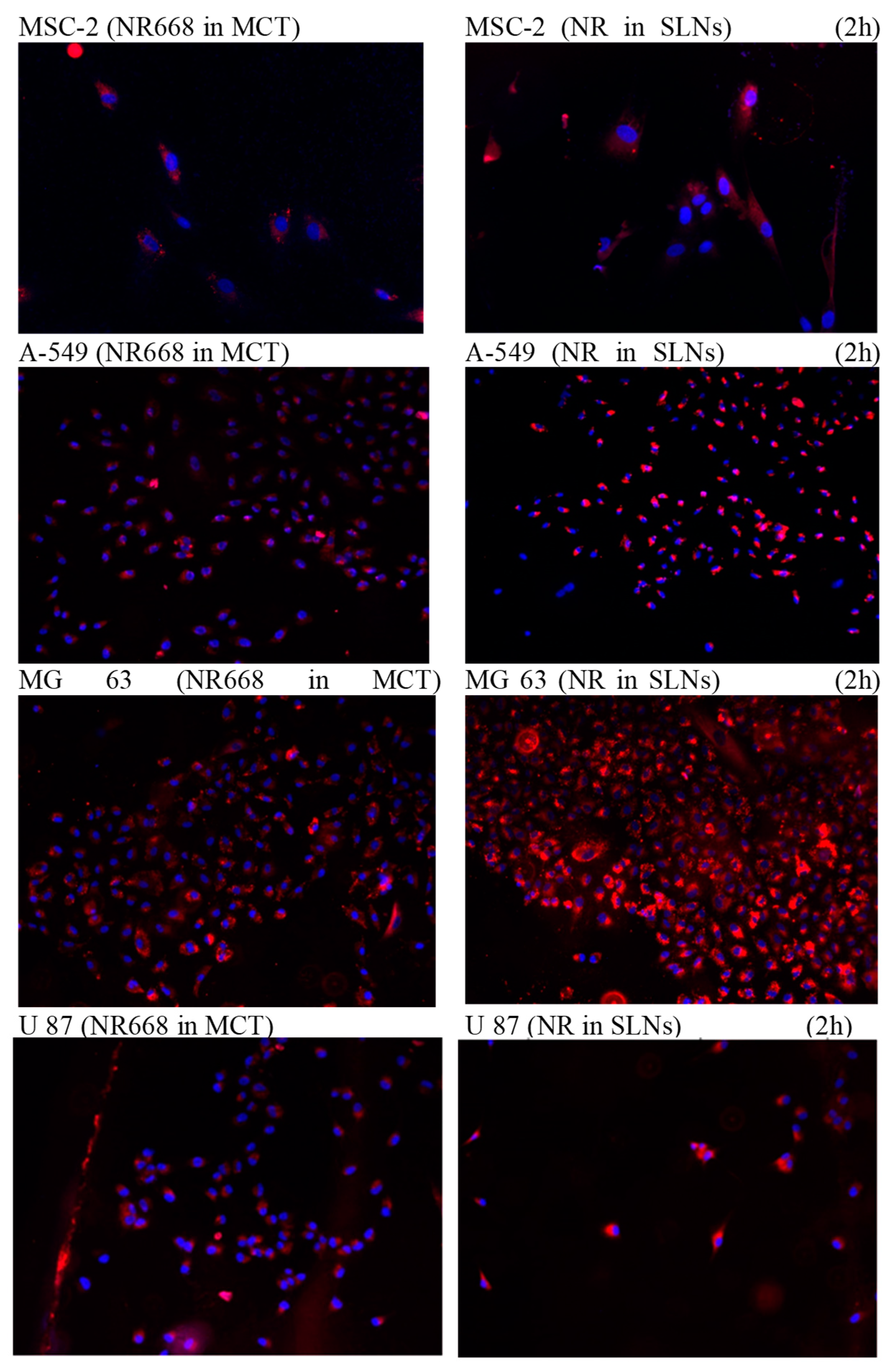

2.7. In Vitro Imaging

The trypsin is inactive by adding the culture medium and we transfer everything to a 50 ml Falcon tube. The tube is centrifuged. Then, the cell pellet is recovered and resuspended in 3 ml of culture medium. Sterilized slides are placed in the wells of 24 then plates and are intended to receive the cultured cells. Around 3.104 cells are put in each well. Then, 1ml of culture medium containing the suspension of NE-SLNs (at a dilution of 1/2000) is added to each well. After 1h, 24h and 48h the lamellae are removed and then 4% PFA is added for 20 minutes to fix the cells. After washing with PBS, DAPI is added to mark the nuclei of the cells in blue. Finally, the cells are washed with PBS and the slides are dried before visualization under a fluorescence microscope.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterizations of SLNs and Pickering Nano-Emulsions

3.1.1. SLNs Size and Polydispersity Index

SLNs size relies on the formulation parameters, notably values of SLRs that were varied by fixing the proportion of solid lipids (Suppocire

® C) and modifying those of nonionic surfactant (Kolliphor

® HS15). The representative value of SLR, of 65%, was selected (from previous report [

14]) to produce SLNs sizing to 40 nm for which the size distribution is reported below.

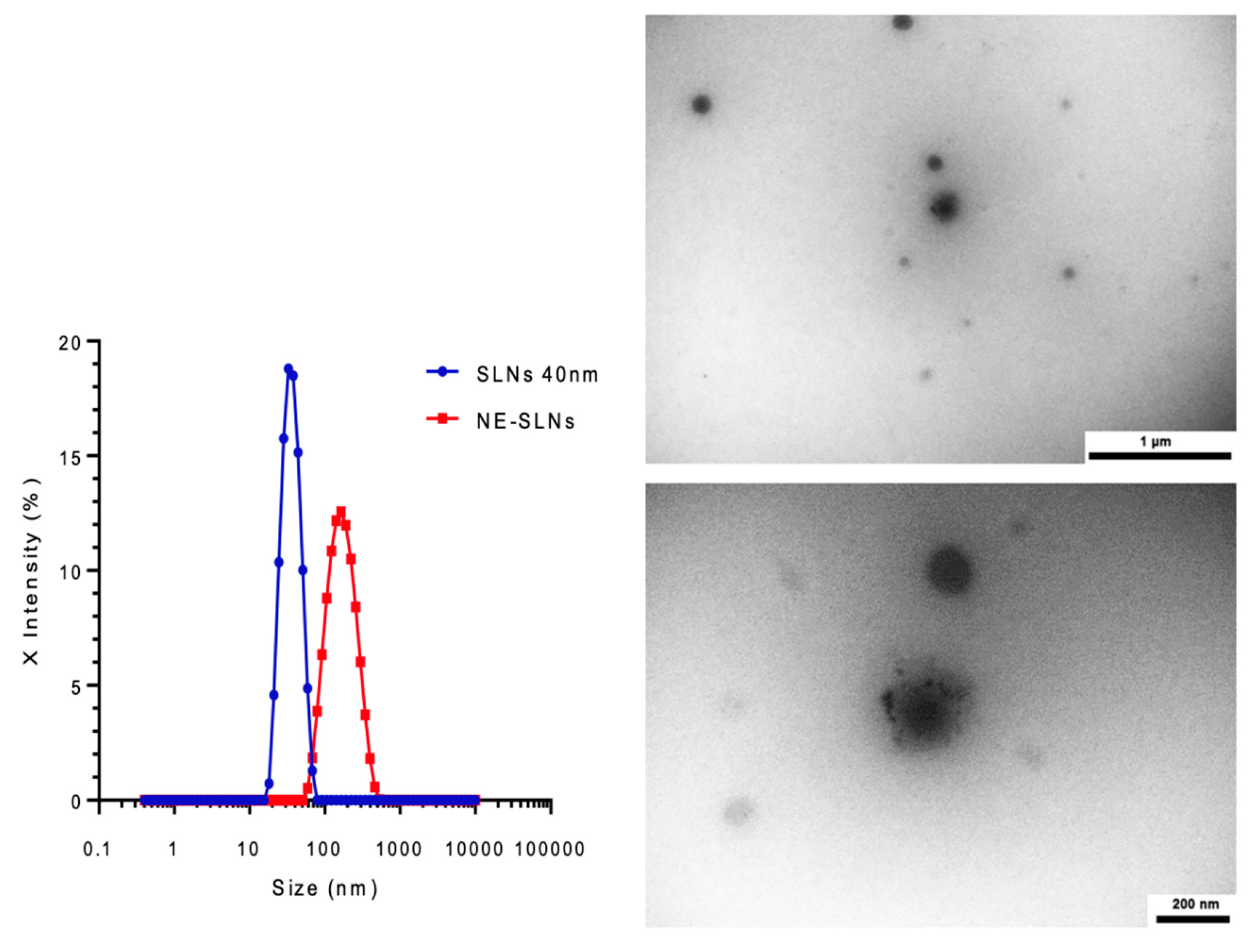

3.1.2. Pickering Nano-Emulsion Size and Polydispersity Index

The sizes of SLNs (40 nm) are used for the preparation of Pickering nano-emulsions. A volume fraction of dispersed phase between the aqueous suspension (containing SLNs) and, Labrafac

® WL 1349 was fixed (

ϕd = 20%). As a result of nano-emulsification by ultrasonication, nano-emulsions obtained were exhibiting a milky and translucent aspect. Results are reported in

Figure 1, showing narrow size distributions of SLNs suspension and Pickering nano-emulsions, with mean sizes of 40 nm and 200 nm, respectively (and values of PDI equal to 0,098 and 0,116 respectively). These results show the feasibility of the formulation of Pickering nano-emulsions, providing monodisperse dispersion of oil nano-droplets, stabilized by SLNs and surfactant-free.

3.1.3. Transmission Electron Microscopy of SLNs and Pickering Nanoemulsions (TEM)

The morphological characterizations of the nano-emulsions were carried out by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The nano-emulsions appeared as round spheres with a size consistent with the dynamic light scattering (DLS) results. TEM images of Pickering nano-emulsions have been reported in

Figure 1, showing spherical and contrasting and distinct features with a size of approximately 160 nm and appearing homogeneously dispersed. These results also seem in agreement with the DLS measurements, proving by direct observation, the feasibility of the formulation of the Pickering nano-emulsion by SLNs, and confirming our previous hypotheses. Moreover, they are also in line with the microscopic observations reported in the literature for Pickering emulsions stabilized by reference solid particles. Classical nano-emulsions (stabilized by surfactants) being particularly stable for steric reasons, this could be the case here also for similar reasons due to the aggregation of SLNs at the interface.

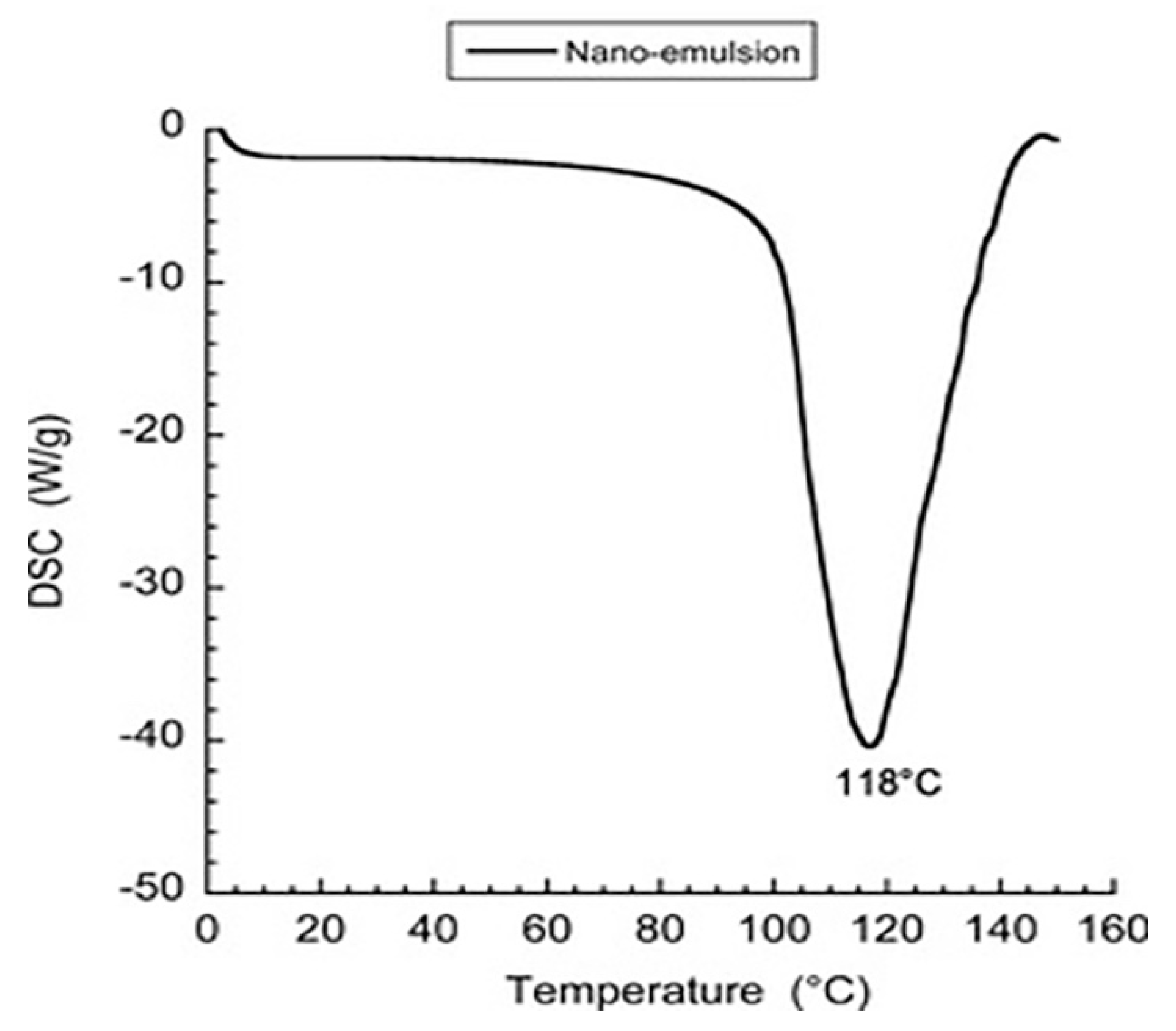

3.2. DSC

The DSC thermograms of the nano-emulsion suspension is reported in

Figure 2. Indeed, heating rate of 5°C/min shows no thermal event in the temperature range from 0°C to 70°C, and shows a significant melting from 80°C. The results were compared to Suppocire

® C and bulk Kolliphor

® HS15 (from previous report [

14]), for an endothermic peaks is observed between 21°C and 33°C.

For nanoemulsions, thermal events were due to Suppocire® C and Kolliphor®HS15, as these were the only components that underwent a solid liquid transition in this temperature range. The melting and crystallization differences between Suppocire® and Kolliphor®HS15 in bulk compared to SLNs and nanoemulsions were due to compartmentalization in the nanometric size domain. These results mean that the SLNs may still be in a glassy state below 30°C and, between 30°C and 40°C, partially melt. This informs us of the fact that, in the temperature range where our experiments were conducted (i.e. T < 40°C), we can consider that the particles are either glassy or at least partially melted.

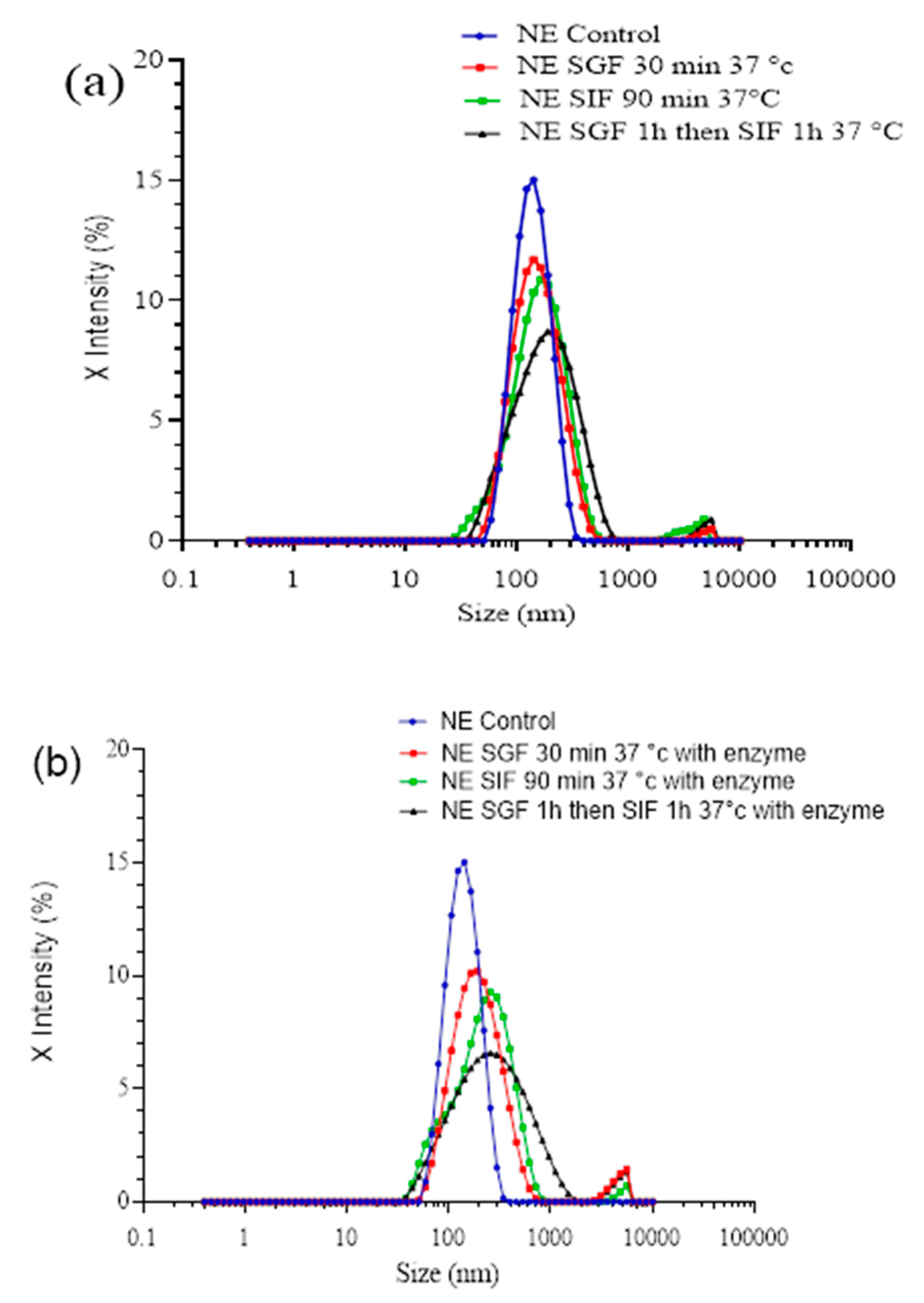

3.3. In Vitro Digestion

Pickering nanoemulsions stabilized by SLNs are complex nanoparticulate lipid systems. Oral lipids administered in different forms, such as bulk oils, lipids emulsions and nano-emulsions (and their subsequent digestion and adsorption of active encapsulated substances) play an essential role in the design of these drug delivery systems. We investigated the size variations occurring in the simulated gastric medium with and without pepsin (as major hydrolysis agent in digestion).

It appears from these results that the droplets have retained their integrity until the end of the treatment. In both cases, a slight evolution of the size distribution is observed, increase in the size and distribution of the population, emphasized in presence of enzyme. This modification can be due to the droplet destabilization process enhancing Ostwald ripening, originated from temperature increase or interactions with components of the incubation medium. In that case of Pickering NEs stabilized with thermo-sensitive SLNs, we have shown [

14] that temperature plays a significant role in the destabilization of such NEs, however, the impacts of the presence of enzymes on the destabilization (

Figure 3 (b)), also testifies that the composition of the incubation medium has a non-negligible impact. To study the behavior of NE

SLNs during digestion, they were subjected to the simulated gastric medium (SGF) and then to simulated intestinal medium (SIF). The results shown in

Figure 3 (b) show a gradual size increase upon the simulated digestion process, suggesting that nano-emulsions have retained their integrities and enzymes effect induce their slight destabilization.

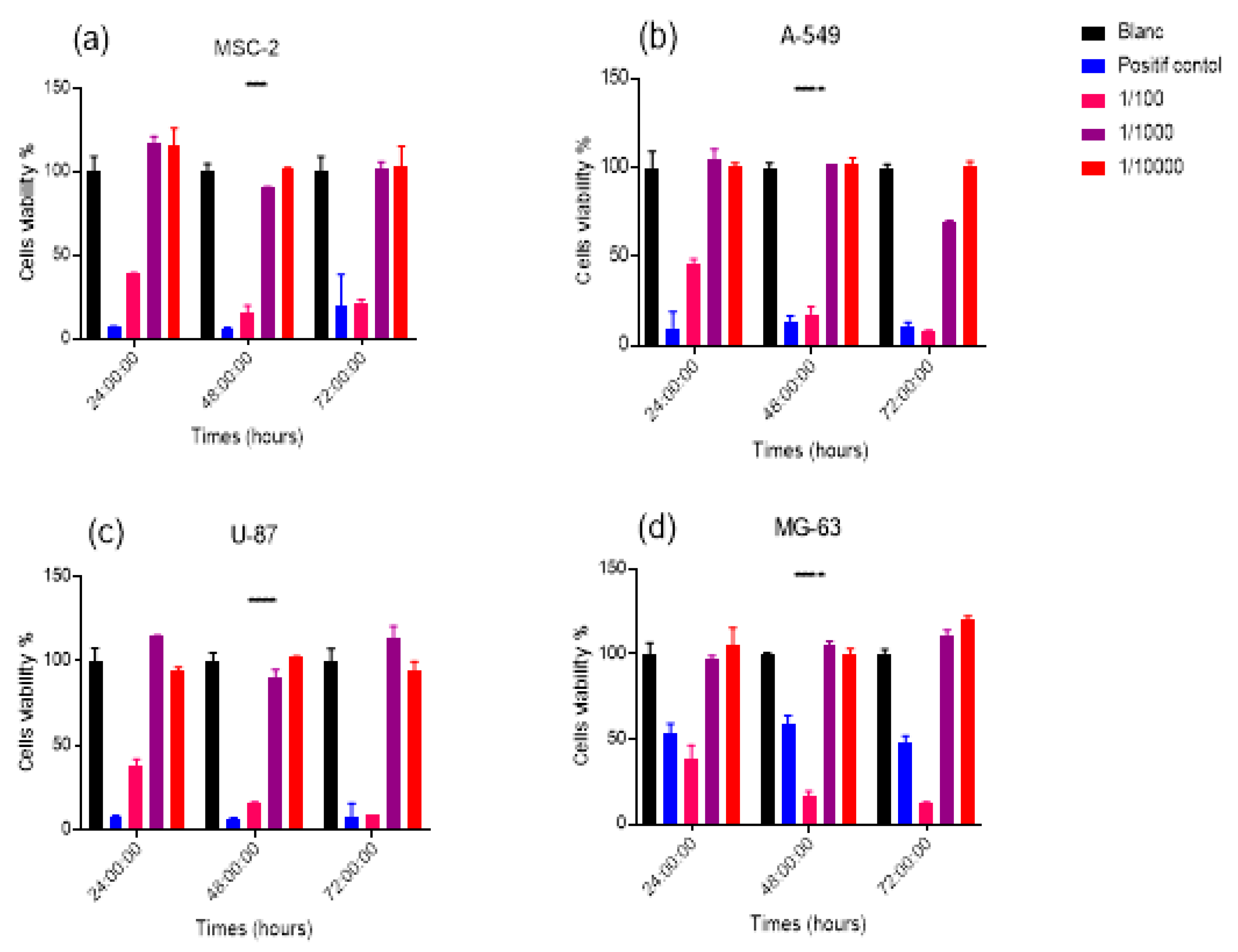

3.4. Cells Viability

The biocompatibility of nanoemulsions has been tested on four cell lines. The healthy mesenchymal cell line MSC-2 and three cancer cell lines MG-63, A549 and U87 were used. As a non-radioactive colorimetric test, the Alamar blue test was selected to assess cell viability and proliferation, as it indicates the metabolic capacity of the cell population used for the cytotoxicity test. Resazurin is directly incubated in the cell culture after the nano-emulsion exposure period. The living cells convert then after 1-4 hours this molecule into a fluorescent product (resorufin) whose quantity is proportional to the number of living cells. The concentration of resorufin was quantified by optical absorbance at 570 nm and 595 nm. The mean value and the standard deviation are the results of three measurements. The test was carried out in three independent experiments and in each experiment, the samples were tested in triplicate. The data were expressed as a percentage. As shown in

Figure 4. The NE

SLNs at a dilution of 1/1000 and 1/10000 showed no cytotoxicity at the different measurement times (24h, 48h and 72h), whereas for the 1/100 dilution and the positive control a decrease was observed cell viability. On the other hand, it should be noted that the concentrations 1/1000 and 1/10000 of the NE

SLNs increase cell metabolism rates probably due to an active absorption process.

3.5. In Vitro Imaging

The following sections on in vitro cell experiments and in vivo imaging focused on the study of the impact of this system (Pickering nano-emulsion) and on living systems. Previous studies [

26,

27] have shown that the interactions between droplets and cells in culture are limited and the cellular uptake relied to the nature of the oily body and surface composition. In the present study, Pickering nanoemulsions were incubated with the cells for 2h at 37°C. To allow the visualization of the droplets under the microscope, a lipophilic dye was introduced into the oily rings at 0.5% by weight in the oil. This fluorophore is a modified dye (NR668) which, once encapsulated in the nano-emulsions, has been shown to not leak into surrounding tissues or lipophilic receptors [

27,

28,

29]. Thus, this tool ensures an effective control of the location of the nano-emulsion droplets in fluorescence imaging. The results are reported in

Figure 5, in which the nuclei of the cells and the nano-emulsions droplets appear in blue and red, respectively. After incubation with the NE

SLNs suspension for 2h, 24h and 48h in the culture medium at 37°C, the A549, MG 63 and U87 cancer cells were fixed and the cell nuclei were stained with 4 ‘, 6-Diamidino -2 phenylindole (DAPI). The images of the cells were acquired by fluorescence microscopy with a wavelength of 650 nm for the dye (Nile Red lipophilic derivative NR668 we used in previous reports [

26,

27]), and a wavelength of 560 nm for the DAPI. Two formulations were made;

(i) one or theNR668 is incorporated into the oily heart of the NE

SLNs and

(ii) one or the NR668is incorporated in the SLNs.

Figure 5 shows intense red fluorescence has been observed in the cell cytoplasm. These results demonstrate that NE

SLNs are effective for contrast cell imaging using Nile Red. A homogeneous distribution of NE

SLNs loaded in NR668was observed. This does not conclude that the intracytosolic localization of NE

SLNs. To prove that the localization of NE

SLNs is intracytosolic, we encapsulated NR668 at high concentrations in the heart of the nanodroplets or in the stabilizing particles. This will not only confirm the internalization of the NE

SLNs. In

Figure 5 we show the intense red fluorescence that has been obtained confirming both intracytosolic localization and the integrity of NE

SLNs and whatever the type of cell tested. NE

SLNs are efficiently absorbed into cells. These results demonstrate Pickering NEs be used to effectively encapsulate and deliver active drug ingredients in cells. In general, when the heart of nanodroplets are composed of triglycerides and without modification of the formulation, NEs exhibits a stealth behavior towards cells, mainly due to the PEGylated surface. In the case of Pickering NEs, a specific interaction is observed. In addition, we observe co-localization of the signal when the fluorescent probe is in the NEs core or when it is in the SLNs, showing that, when the droplets integrate the cells, they are not destroyed. Therefore, it opens new doors for effective drug delivery applications when the drug needs a carrier to cross the cell membrane, for example, combines a retention and permeation enhancing effect that passively targets certain tumors, these nanoemulsions may be an alternative to active targeting technologies to cross the tumor cell membrane once they reach the tumor microenvironment.

4. Conclusions

This study proposes a new formulation of nano-emulsions only stabilized by SLNs. The idea behind this development is the possibility of reducing potential toxicity with lipid nanocarriers without surfactants and without polymers, as well as the possibility of controlling the stabilization of these nano-carriers by exploiting the partial melting of SLNs with temperature. The impact of the temperature revealed a considerable shift in the melting point of the Pickering nano-emulsions. Since the emulsion interfaces are dynamic, here we circumvent the limitation of cell internalization by using stabilizing particles, which gives rise to a modified surface of the nanoemulsions. In contact with the cells in culture, these nano-emulsions exhibit strong interactions and are internalized in the cells in their native form. In this work, we establish the concept of a new lipid Pickering nano-emulsions, and we also emphasize that it is potentially non-toxic and that it significantly impacts their behavior towards living systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.D., N.A, M.D and T.V.; methodology, S.M.D.; Y.I.G., T.Vsoftware, S.M.D.; validation, S.M.D., N.A, M.D and T.V.; formal analysis, S.M.D., N.A, and T.V.; investigation, S.M.D.; resources, M.D., NBJ.; NM and T.V.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.D., N.A, M.D and T.V.; writing—review and editing, S.M.D., N.A, P.M.S., M.J.AC., M.D and T.V.; visualization, S.M.D., N.A, M.D and T.V.; supervision, S.M.D., N.A, M.D and T.V; project administration, S.M.D., N.A, M.D and T.V; funding acquisition, S.M.D., N.A, M.D and T.V All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All generated and required physicochemical data are reported in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank the INSERM (French National Institute of Health and Medical Research), UMR 1260, Regenerative Nanomedicine (RNM), FMTS, Université de Strasbourg, for providing us the reagents, equipment, and laboratories used in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Y. H. Bae et K. Park, « Targeted drug delivery to tumors: Myths, reality and possibility », J. Controlled Release, vol. 153, no 3, p. 198-205, août 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Burrell et C. Swanton, « Tumour heterogeneity and the evolution of polyclonal drug resistance », Mol. Oncol., p. 1095-1111, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Housman et al., « Drug Resistance in Cancer: An Overview », Cancers, vol. 6, no 3, p. 1769-1792, sept. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Kesharwani, S. Kaur, H. Tummala, et A. T. Sangamwar, « Overcoming multiple drug resistance in cancer using polymeric micelles », Expert Opin. Drug Deliv., vol. 15, no 11, p. 1127-1142, nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Kitano, « Cancer as a robust system: implications for anticancer therapy », Nat. Rev. Cancer, vol. 4, no 3, p. 227-235, mars 2004. [CrossRef]

- J. Long et al., « Overcoming drug resistance in pancreatic cancer », Expert Opin. Ther. Targets, vol. 15, no 7, p. 817-828, juill. 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Markman, A. Rekechenetskiy, E. Holler, et J. Y. Ljubimova, « Nanomedicine therapeutic approaches to overcome cancer drug resistance », Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., vol. 65, no 13, p. 1866-1879, nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Q. Liu, M. Das, Y. Liu, et L. Huang, « Targeted drug delivery to melanoma », Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., vol. 127, p. 208-221, mars 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. M. N. Neubi, Y. Opoku-Damoah, X. Gu, Y. Han, J. Zhou, et Y. Ding, « Bio-inspired drug delivery systems: an emerging platform for targeted cancer therapy », Biomater. Sci., vol. 6, no 5, p. 958-973, mai 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Oberoi, K. E. Parrish, T. T. Sio, R. K. Mittapalli, W. F. Elmquist, et J. N. Sarkaria, « Strategies to improve delivery of anticancer drugs across the blood–brain barrier to treat glioblastoma », Neuro-Oncol., vol. 18, no 1, p. 27-36, janv. 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. T. D. Tran et P. H. L. Tran, « Nanoconjugation and Encapsulation Strategies for Improving Drug Delivery and Therapeutic Efficacy of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs », Pharmaceutics, vol. 11, no 7, p. 325, juill. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Buruga et J. T. Kalathi, « Synthesis of poly(styrene-co-methyl methacrylate) nanospheres by ultrasound-mediated Pickering nanoemulsion polymerization », J. Polym. Res., vol. 26, no 9, p. 210, août 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Cheong, K. W. Tan, C. P. Tan, et K. L. Nyam, « Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) seed oil-in-water Pickering nanoemulsions stabilised by mixture of sodium caseinate, Tween 20 and β-cyclodextrin », Food Hydrocoll., vol. 52, p. 934-941, janv. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Dieng et al., « Pickering nano-emulsions stabilized by solid lipid nanoparticles as a temperature sensitive drug delivery system », Soft Matter, oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Sy et al., « Pickering nano-emulsion as a nanocarrier for pH-triggered drug release », Int. J. Pharm., vol. 549, no 1-2, p. 299-305, oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. L. Thompson, N. Cinotti, E. R. Jones, C. J. Mable, P. W. Fowler, et S. P. Armes, « Bespoke Diblock Copolymer Nanoparticles Enable the Production of Relatively Stable Oil-in-Water Pickering Nanoemulsions », Langmuir, vol. 33, no 44, p. 12616-12623, nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Jiménez Saelices et I. Capron, « Design of Pickering Micro- and Nanoemulsions Based on the Structural Characteristics of Nanocelluloses », Biomacromolecules, vol. 19, no 2, p. 460-469, févr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Faridi Esfanjani et S. M. Jafari, « Biopolymer nano-particles and natural nano-carriers for nano-encapsulation of phenolic compounds », Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces, vol. 146, p. 532-543, oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Feng et Y. Lee, « Surface modification of zein colloidal particles with sodium caseinate to stabilize oil-in-water pickering emulsion », Food Hydrocoll., vol. 56, p. 292-302, mai 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. V. Jermain, C. Brough, et R. O. Williams, « Amorphous solid dispersions and nanocrystal technologies for poorly water-soluble drug delivery – An update », Int. J. Pharm., vol. 535, no 1, p. 379-392, janv. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Malamatari, S. Somavarapu, K. M. G. Taylor, et G. Buckton, « Solidification of nanosuspensions for the production of solid oral dosage forms and inhalable dry powders », Expert Opin. Drug Deliv., vol. 13, no 3, p. 435-450, mars 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Nallamilli, B. P. Binks, E. Mani, et M. G. Basavaraj, « Stabilization of Pickering Emulsions with Oppositely Charged Latex Particles: Influence of Various Parameters and Particle Arrangement around Droplets », Langmuir, vol. 31, no 41, p. 11200-11208, oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Tavernier, W. Wijaya, P. Van der Meeren, K. Dewettinck, et A. R. Patel, « Food-grade particles for emulsion stabilization », Trends Food Sci. Technol., vol. 50, p. 159-174, avr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Sarkar, K. K. T. Goh, R. P. Singh, et H. Singh, « Behaviour of an oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by β-lactoglobulin in an in vitro gastric model », Food Hydrocoll., vol. 23, no 6, p. 1563-1569, août 2009. [CrossRef]

- H. Singh, A. Ye, et D. Horne, « Structuring food emulsions in the gastrointestinal tract to modify lipid digestion », Prog. Lipid Res., vol. 48, no 2, p. 92-100, mars 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Attia & Dieng et al., « Functionalizing Nanoemulsions with Carboxylates: Impact on the Biodistribution and Pharmacokinetics in Mice », Macromol. Biosci., vol. 17, no 7, p. 1600471, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Klymchenko et al., « Highly lipophilic fluorescent dyes in nano-emulsions: towards bright non-leaking nano-droplets », RSC Adv., vol. 2, no 31, p. 11876-11886, nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Bouchaala et al., « Integrity of lipid nanocarriers in bloodstream and tumor quantified by near-infrared ratiometric FRET imaging in living mice », J. Controlled Release, vol. 236, p. 57-67, août 2016. [CrossRef]

- V. N. Kilin et al., « Counterion-enhanced cyanine dye loading into lipid nano-droplets for single-particle tracking in zebrafish », Biomaterials, vol. 35, no 18, p. 4950-4957, juin 2014. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).