Submitted:

03 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

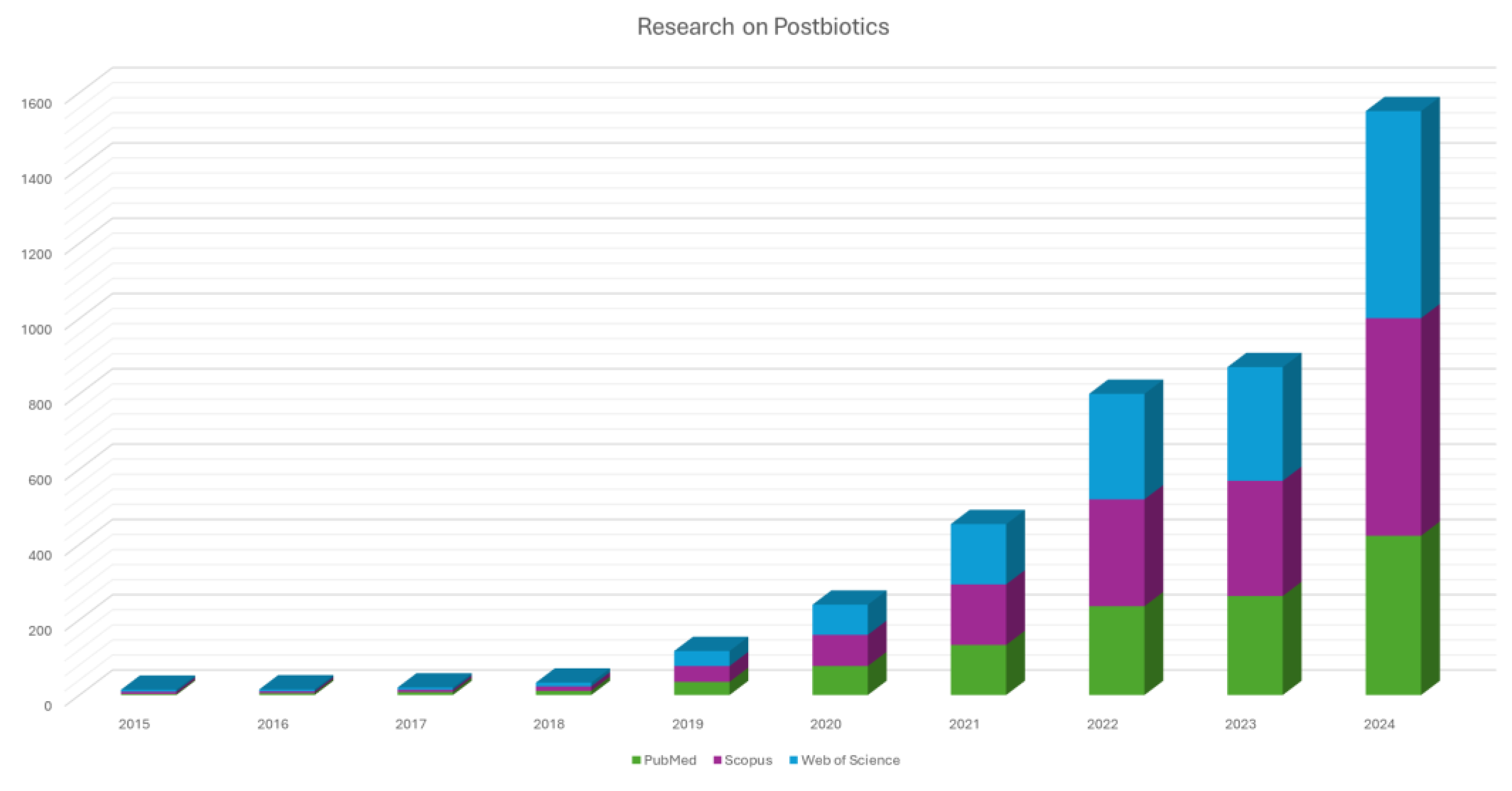

1. Introduction

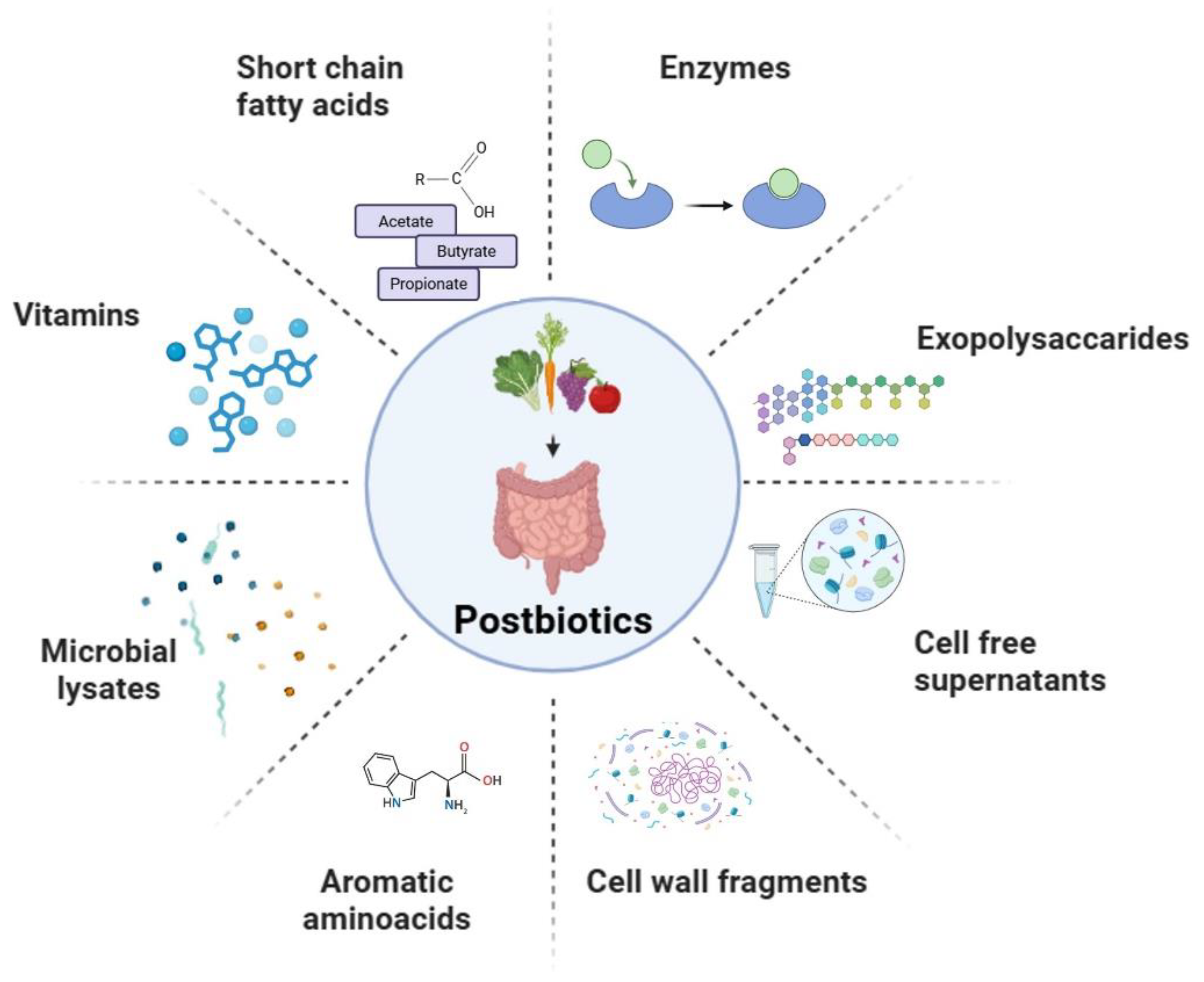

2. Sources of Postbiotics and Classification

2.1. Short Chain Fatty Acids

2. 2. Exopolysaccharides

2.3. Enzymes

2.4. Cell Wall Fragments

2.5. Cell Free Supernatants

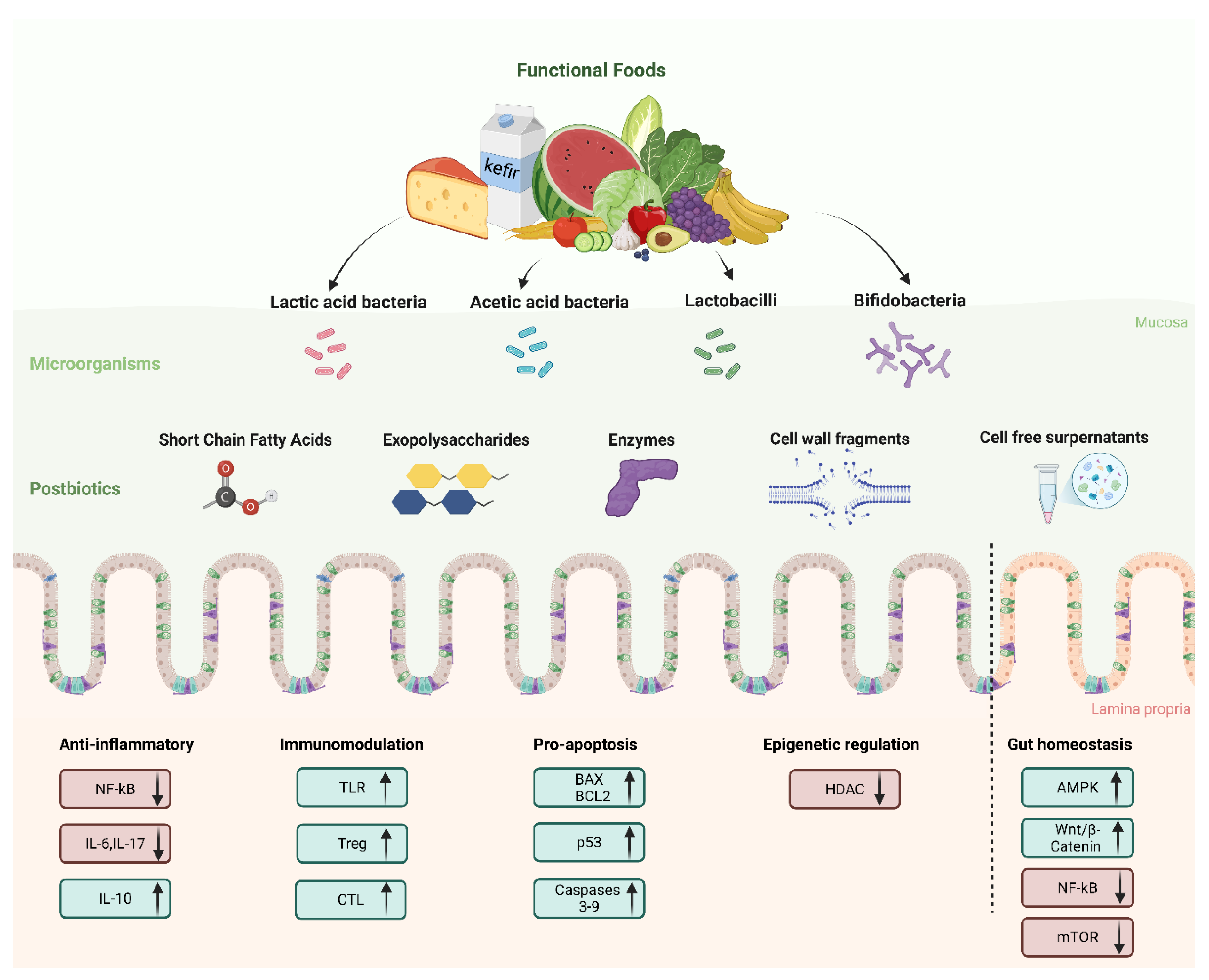

2.6. Postbiotic Functional Food Sources

2.6.1. Sauerkraut (Fermented Cabbage)

2.6.2. Kefir

2.6.3. Kimchi

3. Mechanisms of Action of Postbiotics in Colorectal Cancer

3.1. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Effects

3.2. Apoptosis Induction and Tumor Suppression

3.3. Other Effects

4. Therapeutic Potential and Application in Biomedical System: Current Evidence from Preclinical Studies

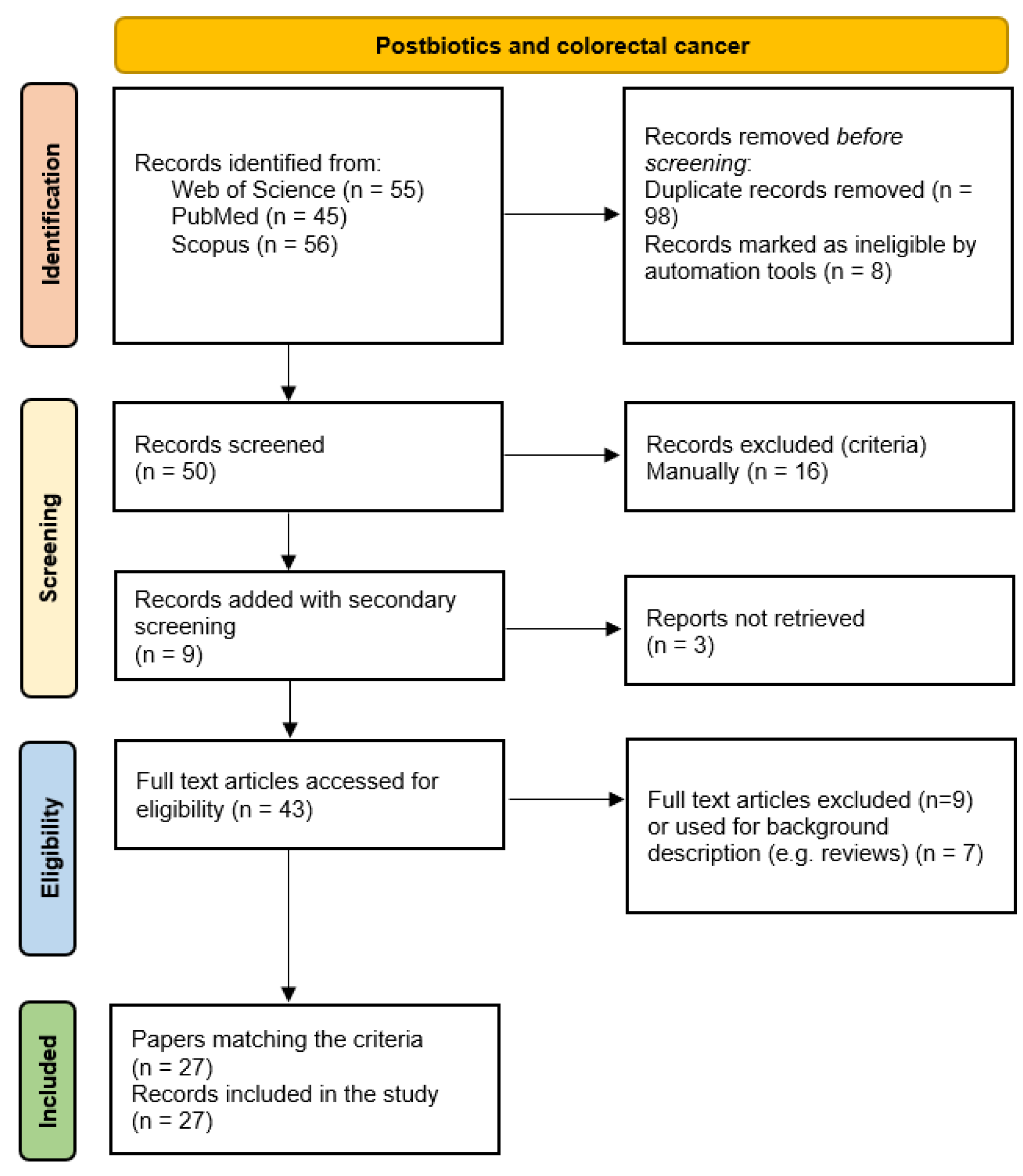

4.1. Methodologies and Software

4.2. Studies on Cell Lines

4.3. In Vivo Studies

4.4. Investigating Postbiotic Safety and Effects Using Advanced Preclinical Models

5. Clinal Evidences, Formulation and Delivery of Postbiotics

5.1. Clinical Evidences

5.2. Postbiotic Formulation and Delivery

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in Health and Diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.-Y.; Mei, J.-X.; Yu, G.; Lei, L.; Zhang, W.-H.; Liu, K.; Chen, X.-L.; Kołat, D.; Yang, K.; Hu, J.-K. Role of the Gut Microbiota in Anticancer Therapy: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, W.; Li, Q.; Yu, J. Gut Microbiota Modulation: A Novel Strategy for Prevention and Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Oncogene 2020, 39, 4925–4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivarelli, S.; Salemi, R.; Candido, S.; Falzone, L.; Santagati, M.; Stefani, S.; Torino, F.; Banna, G.L.; Tonini, G.; Libra, M. Gut Microbiota and Cancer: From Pathogenesis to Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgiano, M.; Bartocci, B.; Puca, P.; di Vincenzo, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Papa, A.; Cammarota, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Scaldaferri, F.; Lopetuso, L.R. Gut Microbiota Modulation in IBD: From the Old Paradigm to Revolutionary Tools. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, H.; Arumugam, M. Gut Microbiota: A Hidden Player in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Transl Med 2025, 23, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Liu, J.; Yu, P.; Qiu, T.; Jiang, S.; Yu, R. Unlocking the Power of Probiotics, Postbiotics: Targeting Apoptosis for the Treatment and Prevention of Digestive Diseases. Front Nutr 2025, 12, 1570268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Jain, S.; Agadzi, B.; Yadav, H. A Cascade of Microbiota-Leaky Gut-Inflammation- Is It a Key Player in Metabolic Disorders? Curr Obes Rep 2025, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, A.; Williams, C.; Yadav, H.; Masternak, M.M.; Labyak, C.; Holland, P.J.; Arikawa, A.Y.; Jain, S. The Selection of Participants for Interventional Microbiota Trials Involving Cognitively Impaired Older Adults. Geroscience 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Cintoni, M.; Raoul, P.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F.; Pulcini, G.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. Food Components and Dietary Habits: Keys for a Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Chierico, F.; Vernocchi, P.; Dallapiccola, B.; Putignani, L. Mediterranean Diet and Health: Food Effects on Gut Microbiota and Disease Control. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2014, 15, 11678–11699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Ju, Z.; Zuo, T. Time for Food: The Impact of Diet on Gut Microbiota and Human Health. Nutrition 2018, 51–52, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Green, K.M.; Rawat, M. A Comprehensive Overview of Postbiotics with a Special Focus on Discovery Techniques and Clinical Applications. Foods 2024, 13, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prajapati, N.; Patel, J.; Singh, S.; Yadav, V.K.; Joshi, C.; Patani, A.; Prajapati, D.; Sahoo, D.K.; Patel, A. Postbiotic Production: Harnessing the Power of Microbial Metabolites for Health Applications. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on the Definition and Scope of Postbiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinderola, G.; Sanders, M.E.; Salminen, S. The Concept of Postbiotics. Foods 2022, 11, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żółkiewicz, J.; Marzec, A.; Ruszczyński, M.; Feleszko, W. Postbiotics-A Step Beyond Pre- and Probiotics. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Xing, D. The Current and Future Perspectives of Postbiotics. Probiotics & Antimicro. Prot. 2023, 15, 1626–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, A.H.; Aghebati-Maleki, L.; Kafil, H.S.; Abbasi, A. Molecular Mechanisms of Postbiotics in Colorectal Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2021, 61, 1787–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizi, H.; Plotnikov,Andrey; Rezaee,Mohammad Ahangarzadeh; Ganbarov,Khudaverdi; Kamounah,Fadhil S. ; Nikitin,Sergei; Kadkhoda,Hiva; Gholizadeh,Pourya; Pagliano,Pasquale; and Kafil, H.S. Postbiotics versus Probiotics in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2024, 64, 3573–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Liu,Zhijia; Wang,Yanfei; Cai,Shengbao; Qiao,Zhu; Hu,Xiaosong; Wang,Tao; and Yi, J. Preventive Methods for Colorectal Cancer Through Dietary Interventions: A Focus on Gut Microbiota Modulation. Food Reviews International 2025, 41, 720–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Fang, L.; Jiang, Z. Probiotics and the Role of Dietary Substrates in Maintaining the Gut Health: Use of Live Microbes and Their Products for Anticancer Effects against Colorectal Cancer. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2024, 34, 1933–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.W.; Harpaz, N.; Itzkowitz, S.H.; Parsons, R.E. Molecular Mechanisms in Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer. Oncogenesis 2023, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, R.; Guo, F.; Heisser, T.; Hackl, M.; Ihle, P.; De Schutter, H.; Van Damme, N.; Valerianova, Z.; Atanasov, T.; Májek, O.; et al. Colorectal Cancer Incidence, Mortality, and Stage Distribution in European Countries in the Colorectal Cancer Screening Era: An International Population-Based Study. Lancet Oncol 2021, 22, 1002–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Wetering, M.; Francies, H.E.; Francis, J.M.; Bounova, G.; Iorio, F.; Pronk, A.; van Houdt, W.; van Gorp, J.; Taylor-Weiner, A.; Kester, L.; et al. Prospective Derivation of a Living Organoid Biobank of Colorectal Cancer Patients. Cell 2015, 161, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asefa, Z.; Belay, A.; Welelaw, E.; Haile, M. Postbiotics and Their Biotherapeutic Potential for Chronic Disease and Their Feature Perspective: A Review. Front. Microbiomes 2025, 4, 1489339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijová, E. Postbiotics as Metabolites and Their Biotherapeutic Potential. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, P.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, V.; Dhiman, A. Postbiotics: An Exposition on next Generation Functional Food Compounds- Opportunities and Challenges. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2025, 65, 1163–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Toalá, J.E.; Garcia-Varela, R.; Garcia, H.S.; Mata-Haro, V.; González-Córdova, A.F.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B.; Hernández-Mendoza, A. Postbiotics: An Evolving Term within the Functional Foods Field. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2018, 75, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saedi, S.; Derakhshan, S.; Hasani, A.; Khoshbaten, M.; Poortahmasebi, V.; Milani, P.G.; Sadeghi, J. Recent Advances in Gut Microbiome Modulation: Effect of Probiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics, and Postbiotics in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Prevention and Treatment. Curr Microbiol 2024, 82, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.; Martino, L.D.; Li, J. Natural Polysaccharides-Based Postbiotics and Their Potential Applications. Explor Med. 2024, 5, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Nguyen, T.T.M.; Yi, E.-J.; Zheng, Q.; Park, S.-J.; Yi, G.-S.; Yang, S.-J.; Kim, M.-J.; Yi, T.-H. Emerging Trends in Skin Anti-Photoaging by Lactic Acid Bacteria: A Focus on Postbiotics. Chemistry 2024, 6, 1495–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harat, S.G.; Pourjafar, H. Health Benefits and Safety of Postbiotics Derived from Different Probiotic Species. Curr Pharm Des 2025, 31, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Khalil, A.A.; Rahman, U.-U.-; Khalid, A.; Naz, S.; Shariati, M.A.; Rebezov, M.; Urtecho, E.Z.; de Albuquerque, R.D.D.G.; Anwar, S.; et al. Recent Advances in the Therapeutic Application of Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): An Updated Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 6034–6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos Meyers, G.; Samouda, H.; Bohn, T. Short Chain Fatty Acid Metabolism in Relation to Gut Microbiota and Genetic Variability. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Hee, B.; Wells, J.M. Microbial Regulation of Host Physiology by Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Trends Microbiol 2021, 29, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, J.; Xie, F.; He, H.; Johnston, L.J.; Dai, X.; Wu, C.; Ma, X. Dietary Fiber-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids: A Potential Therapeutic Target to Alleviate Obesity-Related Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Obes Rev 2021, 22, e13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourebaba, Y.; Marycz, K.; Mularczyk, M.; Bourebaba, L. Postbiotics as Potential New Therapeutic Agents for Metabolic Disorders Management. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 153, 113138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtman, T.A.; Eckermann, H.A.; Smidt, H.; de Weerth, C. Gut Microbiota and BMI throughout Childhood: The Role of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Short-Chain Fatty Acid Producers. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiovanni, T.; Yin, M.O.L.; Heaney, L.M. The Athlete and Gut Microbiome: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Potential Ergogenic Aids for Exercise and Training. Int J Sports Med 2021, 42, 1143–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivière, A.; Selak, M.; Lantin, D.; Leroy, F.; De Vuyst, L. Bifidobacteria and Butyrate-Producing Colon Bacteria: Importance and Strategies for Their Stimulation in the Human Gut. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynés, B.; Palou, M.; Rodríguez, A.M.; Palou, A. Regulation of Adaptive Thermogenesis and Browning by Prebiotics and Postbiotics. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashaolu, T.J.; Ashaolu, J.O.; Adeyeye, S. a. O. Fermentation of Prebiotics by Human Colonic Microbiota in Vitro and Short-Chain Fatty Acids Production: A Critical Review. J Appl Microbiol 2021, 130, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Rodrigues E-Lacerda, R.; Barra, N.G.; Kukje Zada, D.; Robin, N.; Mehra, A.; Schertzer, J.D. Postbiotic Impact on Host Metabolism and Immunity Provides Therapeutic Potential in Metabolic Disease. Endocr Rev 2025, 46, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Hu, H.; Lan, H.; Hong, W.; Yang, Z. Characterization of a Postbiotic Exopolysaccharide Produced by Lacticaseibacillus Paracasei ET-22 with Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Efficacy. Int J Biol Macromol 2025, 306, 141608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, J.X.H.; Tan, L.T.H.; Law, J.W.F.; Ser, H.L.; Khaw, K.Y.; Letchumanan, V.; Lee, L.H.; Goh, B.H. Harnessing the Potentialities of Probiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics, Paraprobiotics, and Postbiotics for Shrimp Farming. Reviews in Aquaculture 2022, 14, 1478–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kango, N.; Nath, S. Prebiotics, Probiotics and Postbiotics: The Changing Paradigm of Functional Foods. J Diet Suppl 2024, 21, 709–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaganapathi, A. ; K.a., A.; Shree Kumari, G.R.; Subathra Devi; Vaithilingam, M. Chapter 28 - Antiatherosclerotic Effects of Postbiotics. In Postbiotics; Dharumadurai, D., Halami, P.M., Eds.; Developments in Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology; Academic Press, 2025; pp. 513–528 ISBN 978-0-443-22188-0.

- Yang, Y.; Fan, G.; Lan, J.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Liu, R. Polysaccharide-Mediated Modulation of Gut Microbiota in the Treatment of Liver Diseases: Promising Approach with Significant Challenges. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 280, 135566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezginç, Y.; Karabekmez-erdem, T.; Tatar, H.D.; Ayman, S.; Ganiyusufoğlu, E.; Dayısoylu, K.S. Health Promoting Benefits of Postbiotics Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria: Exopolysaccharide. Biotech Studies 2022, 31, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Kousheh, S.A.; Almasi, H.; Alizadeh, A.; Guimarães, J.T.; Yılmaz, N.; Lotfi, A. Postbiotics Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria: The next Frontier in Food Safety. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2020, 19, 3390–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razzaq, A.; Shamsi, S.; Ali, A.; Ali, Q.; Sajjad, M.; Malik, A.; Ashraf, M. Microbial Proteases Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S.; Chae, H.S.; Jeong, S.G.; Ham, J.S.; Im, S.K.; Ahn, C.N.; Lee, J.M. In Vitro Antioxidative Properties of Lactobacilli. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 2005, 19, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moreno de LeBlanc, A.; LeBlanc, J.G.; Perdigón, G.; Miyoshi, A.; Langella, P.; Azevedo, V.; Sesma, F. Oral Administration of a Catalase-Producing Lactococcus Lactis Can Prevent a Chemically Induced Colon Cancer in Mice. J Med Microbiol 2008, 57, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, J.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, C.; Dong, Z.; Feng, D.; Ye, H.; Zuo, J. Dietary Catalase Supplementation Alleviates Deoxynivalenol-Induced Oxidative Stress and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Broiler Chickens. Toxins 2022, 14, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Tabashsum, Z.; Anderson, M.; Truong, A.; Houser, A.K.; Padilla, J.; Akmel, A.; Bhatti, J.; Rahaman, S.O.; Biswas, D. Effectiveness of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Prebiotic-like Components in Common Functional Foods. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2020, 19, 1908–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, F.; Yang, W.; Jiang, S.; Li, Y. Supplementation with Exogenous Catalase from Penicillium Notatum in the Diet Ameliorates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Intestinal Oxidative Damage through Affecting Intestinal Antioxidant Capacity and Microbiota in Weaned Pigs. Microbiol Spectr 9, e00654-21. [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Wang, B.; Bai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Suo, H.; Wang, C. Postbiotics Are a Candidate for New Functional Foods. Food Chem X 2024, 23, 101650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.-J.; Kim, H.; Chung, D.-K. Differential Immunostimulatory Effects of Lipoteichoic Acids Isolated from Four Strains of Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, A.G.; Corrêa, J.A.F.; Dos Santos, J.V.G.; Matté, E.H.C.; Milek, M.M.; Biauki, G.C.; Costa, L.B.; Luciano, F.B. Cell-Free Supernatants Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria Reduce Salmonella Population in Vitro. Microbiology (Reading) 2021, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermudez-Brito, M.; Muñoz-Quezada, S.; Gomez-Llorente, C.; Matencio, E.; Bernal, M.J.; Romero, F.; Gil, A. Cell-Free Culture Supernatant of Bifidobacterium Breve CNCM I-4035 Decreases Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Human Dendritic Cells Challenged with Salmonella Typhi through TLR Activation. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e59370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Marco, M.L. The Fermented Cabbage Metabolome and Its Protection against Cytokine-Induced Intestinal Barrier Disruption of Caco-2 Monolayers. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2025, 0, e02234–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cagno, R.; Coda, R.; De Angelis, M.; Gobbetti, M. Exploitation of Vegetables and Fruits through Lactic Acid Fermentation. Food Microbiology 2013, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plengvidhya, V.; Breidt, F.; Lu, Z.; Fleming, H.P. DNA Fingerprinting of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Sauerkraut Fermentations. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007, 73, 7697–7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamang, J.P.; Shin, D.-H.; Jung, S.-J.; Chae, S.-W. Functional Properties of Microorganisms in Fermented Foods. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabat, M.A.; Sano, W.H.; Wurster, J.I.; Cabral, D.J.; Belenky, P. Microbial Community Analysis of Sauerkraut Fermentation Reveals a Stable and Rapidly Established Community. Foods 2018, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermented Foods in Health and Disease Prevention; 2016; ISBN 978-0-12-802309-9.

- Marco, M.L.; Pavan, S.; Kleerebezem, M. Towards Understanding Molecular Modes of Probiotic Action. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2006, 17, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraporda, C.; Errea, A.; Romanin, D.E.; Cayet, D.; Pereyra, E.; Pignataro, O.; Sirard, J.C.; Garrote, G.L.; Abraham, A.G.; Rumbo, M. Lactate and Short Chain Fatty Acids Produced by Microbial Fermentation Downregulate Proinflammatory Responses in Intestinal Epithelial Cells and Myeloid Cells. Immunobiology 2015, 220, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-S.; Kim, T.-Y.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, S.; Kang, S.W.; Yang, J.-Y.; Baek, I.-J.; Sung, Y.H.; Park, Y.-Y.; et al. Microbiota-Derived Lactate Accelerates Intestinal Stem-Cell-Mediated Epithelial Development. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 833–846.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M.G.B.; Søndergaard, E.; Nielsen, C.B.; Johannsen, M.; Gormsen, L.C.; Møller, N.; Jessen, N.; Rittig, N. Oral Lactate Slows Gastric Emptying and Suppresses Appetite in Young Males. Clinical Nutrition 2022, 41, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Xu,Ruijie; Li,Xiu; Yao,Zhijie; Zhang,Hao; Li,Haitao; and Chen, W. Unexpected Immunoregulation Effects of D-Lactate, Different from L-Lactate. Food and Agricultural Immunology 2022, 33, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, D.S.; So, D.; Gill, P.A.; Kellow, N.J. Effect of Dietary Acetic Acid Supplementation on Plasma Glucose, Lipid Profiles, and Body Mass Index in Human Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2021, 121, 895–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, H.O.; Moraes, W.M.A.M. de; Silva, G.A.R. da; Prestes, J.; Schoenfeld, B.J. Vinegar (Acetic Acid) Intake on Glucose Metabolism: A Narrative Review. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 2019, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunaefi, D.; Akumo, D.N.; Smetanska, I. Effect of Fermentation on Antioxidant Properties of Red Cabbages. Food Biotechnology 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaulmann, A.; Jonville, M.-C.; Schneider, Y.-J.; Hoffmann, L.; Bohn, T. Carotenoids, Polyphenols and Micronutrient Profiles of Brassica Oleraceae and Plum Varieties and Their Contribution to Measures of Total Antioxidant Capacity. Food Chemistry 2014, 155, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Villaluenga, C.; Peñas, E.; Sidro, B.; Ullate, M.; Frias, J.; Vidal-Valverde, C. White Cabbage Fermentation Improves Ascorbigen Content, Antioxidant and Nitric Oxide Production Inhibitory Activity in LPS-Induced Macrophages. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2012, 46, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajka-Kuźniak, V.; Szaefer, H.; Bartoszek, A.; Baer-Dubowska, W. Modulation of Rat Hepatic and Kidney Phase II Enzymes by Cabbage Juices: Comparison with the Effects of Indole-3-Carbinol and Phenethyl Isothiocyanate. British Journal of Nutrition 2011, 105, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddeeg, A.; Afzaal,Muhammad; Saeed,Farhan; Ali,Rehman; Shah,Yasir Abbas; Shehzadi,Umber; Ateeq,Huda; Waris,Numra; Hussain,Muzzamal; Raza,Muhammad Ahtisham; et al. Recent Updates and Perspectives of Fermented Healthy Super Food Sauerkraut: A Review. International Journal of Food Properties 2022, 25, 2320–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.; Krumbholz, P.; Jäger, E.; Heintz-Buschart, A.; Çakir, M.V.; Rothemund, S.; Gaudl, A.; Ceglarek, U.; Schöneberg, T.; Stäubert, C. Metabolites of Lactic Acid Bacteria Present in Fermented Foods Are Highly Potent Agonists of Human Hydroxycarboxylic Acid Receptor 3. PLOS Genetics 2019, 15, e1008145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperek, M.C.; Velasquez Galeas, A.; Caetano-Silva, M.E.; Xie, Z.; Ulanov, A.; La Frano, M.; Devkota, S.; Miller, M.J.; Allen, J.M. Microbial Aromatic Amino Acid Metabolism Is Modifiable in Fermented Food Matrices to Promote Bioactivity. Food Chemistry 2024, 454, 139798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, C.D.; Sing, E.; Mo, J.; Shealy, N.G.; Yoo, W.; Thomas, J.; Fitz, G.N.; Castro, P.R.; Hickman, T.T.; Torres, T.P.; et al. An Early-Life Microbiota Metabolite Protects against Obesity by Regulating Intestinal Lipid Metabolism. Cell Host & Microbe 2023, 31, 1604–1619.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrick, B.M.; Rodriguez, L.; Lakshmikanth, T.; Pou, C.; Henckel, E.; Arzoomand, A.; Olin, A.; Wang, J.; Mikes, J.; Tan, Z.; et al. Bifidobacteria-Mediated Immune System Imprinting Early in Life. Cell 2021, 184, 3884–3898.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Choi, K.-B.; Park, J.H.; Kim, K.H. Metabolite Profile Changes and Increased Antioxidative and Antiinflammatory Activities of Mixed Vegetables after Fermentation by Lactobacillus Plantarum. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0217180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garofalo, C.; Ferrocino, I.; Reale, A.; Sabbatini, R.; Milanović, V.; Alkić-Subašić, M.; Boscaino, F.; Aquilanti, L.; Pasquini, M.; Trombetta, M.F.; et al. Study of Kefir Drinks Produced by Backslopping Method Using Kefir Grains from Bosnia and Herzegovina: Microbial Dynamics and Volatilome Profile. Food Res Int 2020, 137, 109369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, N.F.; Kumar, M.R.; Yeap, S.K.; Abdullah, J.O.; Khalid, M.; Omar, A.R.; Osman, M.A.; Mortadza, S.A.S.; Alitheen, N.B. Kefir and Its Biological Activities. Foods 2021, 10, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, M.R.; Blandón, L.M.; Vandenberghe, L.P.S.; Rodrigues, C.; Castro, G.R.; Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Soccol, C.R. Milk Kefir: Composition, Microbial Cultures, Biological Activities, and Related Products. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, S.É. de L.; Rocha, C. dos S.; Moura, M.S.B. de; Barcelos, M.P.; Silva, C.H.T. de P. da; Hage-Melim, L.I. da S. Potential Beneficial Effects of Kefir and Its Postbiotic, Kefiran, on Child Food Allergy. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 3770–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, K.L.; Caputo, L.R.G.; Carvalho, J.C.T.; Evangelista, J.; Schneedorf, J.M. Antimicrobial and Healing Activity of Kefir and Kefiran Extract. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2005, 25, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.-H.; Gyu Lee, H.; Young Eor, J.; Jin Jeon, H.; Yokoyama, W.; Kim, H. Effects of Kefir Lactic Acid Bacteria-Derived Postbiotic Components on High Fat Diet-Induced Gut Microbiota and Obesity. Food Research International 2022, 157, 111445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, D.D.; Dias, M.M.S.; Grześkowiak, Ł.M.; Reis, S.A.; Conceição, L.L.; Peluzio, M. do C.G. Milk Kefir: Nutritional, Microbiological and Health Benefits. Nutr Res Rev 2017, 30, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingirikari, J.M.R.; Sharma, A.; Lee, H.-J. Kefir: A Fermented Plethora of Symbiotic Microbiome and Health. Journal of Ethnic Foods 2024, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, D.; Thinthasit, A.; Surya, E.; Hartati; Oh, J. -S.; Jang, J.-G.; Benchawattananon, R.; Surya, R. Immunoenhancing and Antioxidant Potentials of Kimchi, an Ethnic Food from Korea, as a Probiotic and Postbiotic Food. Journal of Ethnic Foods 2024, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sionek, B.; Szydłowska, A.; Küçükgöz, K.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Traditional and New Microorganisms in Lactic Acid Fermentation of Food. Fermentation 2023, 9, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Carbonero, F.; Zoetendal, E.G.; DeLany, J.P.; Wang, M.; Newton, K.; Gaskins, H.R.; O’Keefe, S.J.D. Diet, Microbiota, and Microbial Metabolites in Colon Cancer Risk in Rural Africans and African Americans. Am J Clin Nutr 2013, 98, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Pitmon, E.; Wang, K. Microbiome, Inflammation and Colorectal Cancer. Semin Immunol 2017, 32, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.K.; Macia, L.; Mackay, C.R. Dietary Fiber and SCFAs in the Regulation of Mucosal Immunity. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2023, 151, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangaraju, M.; Cresci, G.A.; Liu, K.; Ananth, S.; Gnanaprakasam, J.P.; Browning, D.D.; Mellinger, J.D.; Smith, S.B.; Digby, G.J.; Lambert, N.A.; et al. GPR109A Is a G-Protein-Coupled Receptor for the Bacterial Fermentation Product Butyrate and Functions as a Tumor Suppressor in Colon. Cancer Res 2009, 69, 2826–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazmanian, S.K.; Round, J.L.; Kasper, D.L. A Microbial Symbiosis Factor Prevents Intestinal Inflammatory Disease. Nature 2008, 453, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.M.; Howitt, M.R.; Panikov, N.; Michaud, M.; Gallini, C.A.; Bohlooly-Y, M.; Glickman, J.N.; Garrett, W.S. The Microbial Metabolites, Short-Chain Fatty Acids, Regulate Colonic Treg Cell Homeostasis. Science 2013, 341, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Kelly, C.J.; Battista, K.D.; Schaefer, R.; Lanis, J.M.; Alexeev, E.E.; Wang, R.X.; Onyiah, J.C.; Kominsky, D.J.; Colgan, S.P. Microbial-Derived Butyrate Promotes Epithelial Barrier Function through IL-10 Receptor–Dependent Repression of Claudin-2. The Journal of Immunology 2017, 199, 2976–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Li, Z.-R.; Green, R.S.; Holzman, I.R.; Lin, J. Butyrate Enhances the Intestinal Barrier by Facilitating Tight Junction Assembly via Activation of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase in Caco-2 Cell Monolayers. J Nutr 2009, 139, 1619–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanis, J.M.; Alexeev, E.E.; Curtis, V.F.; Kitzenberg, D.A.; Kao, D.J.; Battista, K.D.; Gerich, M.E.; Glover, L.E.; Kominsky, D.J.; Colgan, S.P. Tryptophan Metabolite Activation of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Regulates IL-10 Receptor Expression on Intestinal Epithelia. Mucosal Immunology 2017, 10, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Du, P.; Xie, Q.; Wang, N.; Li, H.; Smith, E.E.; Li, C.; Liu, F.; Huo, G.; Li, B. Protective Effects of Tryptophan-Catabolizing Lactobacillus Plantarum KLDS 1.0386 against Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis in Mice. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 10736–10747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes-Barragan, L.; Chai, J.N.; Tianero, M.D.; Di Luccia, B.; Ahern, P.P.; Merriman, J.; Cortez, V.S.; Caparon, M.G.; Donia, M.S.; Gilfillan, S.; et al. Lactobacillus Reuteri Induces Gut Intraepithelial CD4+CD8αα+ T Cells. Science 2017, 357, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabah, H.; Ménard, O.; Gaucher, F.; do Carmo, F.L.R.; Dupont, D.; Jan, G. Cheese Matrix Protects the Immunomodulatory Surface Protein SlpB of Propionibacterium Freudenreichii during in Vitro Digestion. Food Research International 2018, 106, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taverniti, V.; Stuknyte, M.; Minuzzo, M.; Arioli, S.; De Noni, I.; Scabiosi, C.; Cordova, Z.M.; Junttila, I.; Hämäläinen, S.; Turpeinen, H.; et al. S-Layer Protein Mediates the Stimulatory Effect of Lactobacillus Helveticus MIMLh5 on Innate Immunity. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2013, 79, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shen, T.; Zhang, P.; Ma, Y.; Qin, H. Lactobacillus Plantarum Surface Layer Adhesive Protein Protects Intestinal Epithelial Cells against Tight Junction Injury Induced by Enteropathogenic Escherichia Coli. Mol Biol Rep 2011, 38, 3471–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaji, R.; Kiyoshima-Shibata, J.; Nagaoka, M.; Nanno, M.; Shida, K. Bacterial Teichoic Acids Reverse Predominant IL-12 Production Induced by Certain Lactobacillus Strains into Predominant IL-10 Production via TLR2-Dependent ERK Activation in Macrophages. The Journal of Immunology 2010, 184, 3505–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkovich, S.; Jobin, C. Microbiota and Host Immune Responses: A Love–Hate Relationship. Immunology 2016, 147, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, M.; Khan, M.W.; Goh, Y.J.; Selle, K.; Owen, J.L.; Klaenhammer, T.; Mohamadzadeh, M. Induction of Intestinal Pro-Inflammatory Immune Responses by Lipoteichoic Acid. Journal of Inflammation 2012, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Li, T.; Lu, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Ma, H.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, J.; et al. Lactobacillus Plantarum-Derived Indole-3-Lactic Acid Ameliorates Colorectal Tumorigenesis via Epigenetic Regulation of CD8+ T Cell Immunity. Cell Metab 2023, 35, 943–960.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Cao, H.; Cover, T.L.; Whitehead, R.; Washington, M.K.; Polk, D.B. Soluble Proteins Produced by Probiotic Bacteria Regulate Intestinal Epithelial Cell Survival and Growth. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäuerl, C.; Coll-Marqués, J.M.; Tarazona-González, C.; Pérez-Martínez, G. Lactobacillus Casei Extracellular Vesicles Stimulate EGFR Pathway Likely Due to the Presence of Proteins P40 and P75 Bound to Their Surface. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 19237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Shang, M.; Zhang, Y.-G.; Jiao, Y.; Xia, Y.; Garrett, S.; Bakke, D.; Bäuerl, C.; Martinez, G.P.; Kim, C.-H.; et al. Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated From Korean Kimchi Activate the Vitamin D Receptor–Autophagy Signaling Pathways. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2020, 26, 1199–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, A.; Rad, A.H.; Maleki, L.A.; Kafil, H.S.; Baghbanzadeh, A. Antigenotoxicity and Cytotoxic Potentials of Cell-Free Supernatants Derived from Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Var. Boulardii on HT-29 Human Colon Cancer Cell Lines. Probiotics & Antimicro. Prot. 2023, 15, 1583–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi Ardestani, S.; Tafvizi, F.; Tajabadi Ebrahimi, M. Heat-Killed Probiotic Bacteria Induce Apoptosis of HT-29 Human Colon Adenocarcinoma Cell Line via the Regulation of Bax/Bcl2 and Caspases Pathway. Hum Exp Toxicol 2019, 38, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, H.; Fujiya, M.; Tanaka, H.; Ueno, N.; Moriichi, K.; Sasajima, J.; Ikuta, K.; Akutsu, H.; Tanabe, H.; Kohgo, Y. Probiotic-Derived Ferrichrome Inhibits Colon Cancer Progression via JNK-Mediated Apoptosis. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 12365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoe, D.R.; Holley, D.; Collins, L.B.; Montgomery, S.A.; Whitmore, A.C.; Hillhouse, A.; Curry, K.P.; Renner, S.W.; Greenwalt, A.; Ryan, E.P.; et al. A Gnotobiotic Mouse Model Demonstrates That Dietary Fiber Protects against Colorectal Tumorigenesis in a Microbiota- and Butyrate-Dependent Manner. Cancer Discovery 2014, 4, 1387–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Zhang, Z.; Han, S.; Lu, X. Butyrate Inhibits the Proliferation and Induces the Apoptosis of Colorectal Cancer HCT116 Cells via the Deactivation of MTOR/S6K1 Signaling Mediated Partly by SIRT1 Downregulation. Molecular Medicine Reports 2019, 19, 3941–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, T.Y.; Kim, K.; Son, M.-Y.; Min, J.-K.; Kim, J.; Han, T.-S.; Kim, D.-S.; Cho, H.-S. Downregulation of PRMT1, a Histone Arginine Methyltransferase, by Sodium Propionate Induces Cell Apoptosis in Colon Cancer. Oncology Reports 2019, 41, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasenko, N.; Nudelman, A.; Tarasenko, I.; Entin-Meer, M.; Hass-Kogan, D.; Inbal, A.; Rephaeli, A. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors: The Anticancer, Antimetastatic and Antiangiogenic Activities of AN-7 Are Superior to Those of the Clinically Tested AN-9 (Pivanex). Clin Exp Metastasis 2008, 25, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.R.; Humphreys, K.J.; Simpson, K.J.; McKinnon, R.A.; Meech, R.; Michael, M.Z. Functional High-Throughput Screen Identifies MicroRNAs That Promote Butyrate-Induced Death in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Molecular Therapy Nucleic Acids 2022, 30, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, A.; Fullaondo, A.; Odriozola, I.; Odriozola, A. Chapter Eight - Microbiota and Beneficial Metabolites in Colorectal Cancer. In Advances in Genetics; Martínez, A.O., Ed.; Advances in Host Genetics and Microbiome in Colorectal Cancer-Related Phenotypes; Academic Press, 2024; Vol. 112, pp. 367–409.

- Da, M.; Sun, J.; Ma, C.; Li, D.; Dong, L.; Wang, L.-S.; Chen, F. Postbiotics: Enhancing Human Health with a Novel Concept. eFood 2024, 5, e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.; El-Gazzar, N.; Almanaa, T.N.; El-Hadary, A.; Sitohy, M. Lipolytic Postbiotic from Lactobacillus Paracasei Manages Metabolic Syndrome in Albino Wistar Rats. Molecules 2021, 26, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Systematic Reviews 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedrine, M.L.; Hanlon, J.; Bevan, R.; Floyd, P.; Brown, T.; Matthies, F. Extensive Literature Search, Selection for Relevance and Data Extraction of Studies Related to the Toxicity of PCDD/Fs and DL-PCBs in Humans. EFSA Supporting Publications 2018, 15, 1136E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, T.; Chaari, M.; Falco, G.; De Gregorio, G.; Zaraî Jaouadi, N.; Ali, D.S.; Sarkar, T.; Smaoui, S. When Sustainability Meets Health and Innovation: The Case of Citrus by-Products for Cancer Chemoprevention and Applications in Functional Foods. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2024, 58, 103163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla, J.; Lane, M.A.; Maitin, V. Cell-Free Supernatants from Probiotic Lactobacillus Casei and Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG Decrease Colon Cancer Cell Invasion In Vitro. Nutrition and Cancer 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elham, N.; Naheed, M.; Elahe, M.; Hossein, M.M.; Majid, T. Selective Cytotoxic Effect of Probiotic, Paraprobiotic and Postbiotics of L.Casei Strains against Colorectal Cancer Cells: Invitro Studies. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 58, e19400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-Y.; Hsieh, Y.-M.; Huang, C.-C.; Tsai, C.-C. Inhibitory Effects of Probiotic Lactobacillus on the Growth of Human Colonic Carcinoma Cell Line HT-29. Molecules 2017, 22, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastrząb, R.; Tomecki, R.; Jurkiewicz, A.; Graczyk, D.; Szczepankowska, A.K.; Mytych, J.; Wolman, D.; Siedlecki, P. The Strain-Dependent Cytostatic Activity of Lactococcus Lactis on CRC Cell Lines Is Mediated through the Release of Arginine Deiminase. Microbial Cell Factories 2024, 23, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Li, Z.; Mao, L.; Chen, S.; Sun, S. Sodium Butyrate Induces Autophagy in Colorectal Cancer Cells through LKB1/AMPK Signaling. J Physiol Biochem 2019, 75, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuah, L.-O.; Foo, H.L.; Loh, T.C.; Mohammed Alitheen, N.B.; Yeap, S.K.; Abdul Mutalib, N.E.; Abdul Rahim, R.; Yusoff, K. Postbiotic Metabolites Produced by Lactobacillus Plantarum Strains Exert Selective Cytotoxicity Effects on Cancer Cells. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2019, 19, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macias-Diaz, A.; Lopez, J.J.; Bravo, M.; Jardín, I.; Garcia-Jimenez, W.L.; Blanco-Blanco, F.J.; Cerrato, R.; Rosado, J.A. Postbiotics of Lacticaseibacillus Paracasei CECT 9610 and Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum CECT 9608 Attenuates Store-Operated Calcium Entry and FAK Phosphorylation in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Molecular Oncology 2024, 18, 1123–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepak, V.; Ram Kumar Pandian,Sureshbabu; Sivasubramaniam,Shiva D. ; Nellaiah,Hariharan; and Sundar, K. Optimization of Anticancer Exopolysaccharide Production from Probiotic Lactobacillus Acidophilus by Response Surface Methodology. Preparative Biochemistry & Biotechnology 2016, 46, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousin, F.J.; Jouan-Lanhouet, S.; Théret, N.; Brenner, C.; Jouan, E.; Moigne-Muller, G.L.; Dimanche-Boitrel, M.-T.; Jan, G. The Probiotic Propionibacterium Freudenreichii as a New Adjuvant for TRAIL-Based Therapy in Colorectal Cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 7161–7178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.-H.; Park, J.H.; Jeon, W.-M.; Han, K.-S. Butyrate Modulates Bacterial Adherence on LS174T Human Colorectal Cells by Stimulating Mucin Secretion and MAPK Signaling Pathway. Nutrition Research and Practice 2015, 9, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wu, X.; Yang, L.; Xu, X. The Intervention of B. Longum Metabolites in Fnevs’ Carcinogenic Capacity: A Potential Double-Edged Sword. Experimental Cell Research 2025, 445, 114407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfanian, N.; Nasseri, S.; Miraki Feriz, A.; Safarpour, H.; Namaei, M.H. Characterization of Wnt Signaling Pathway under Treatment of Lactobacillus Acidophilus Postbiotic in Colorectal Cancer Using an Integrated in Silico and in Vitro Analysis. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 22988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfanian, N.; Safarpour, H.; Tavakoli, T.; Mahdiabadi, M.A.; Nasseri, S.; Namaei, M.H. Investigating the Therapeutic Potential of Bifidobacterium Breve and Lactobacillus Rhamnosus Postbiotics through Apoptosis Induction in Colorectal HT-29 Cancer Cells. Iran J Microbiol 2024, 16, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neffe-Skocińska, K.; Długosz, E.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L.; Zielińska, D. Novel Gluconobacter Oxydans Strains Selected from Kombucha with Potential Postbiotic Activity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2024, 108, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Liu, L.; Peek, R.M.; Acra, S.A.; Moore, D.J.; Wilson, K.T.; He, F.; Polk, D.B.; Yan, F. Supplementation of P40, a Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG-Derived Protein, in Early Life Promotes Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Dependent Intestinal Development and Long-Term Health Outcomes. Mucosal Immunology 2018, 11, 1316–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Shukla, G. Administration of Metabiotics Extracted From Probiotic Lactobacillus Rhamnosus MD 14 Inhibit Experimental Colorectal Carcinogenesis by Targeting Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, F.; Song, Y.; Sun, M.; Wang, A.; Jiang, S.; Mu, G.; Tuo, Y. Exopolysaccharide Produced by Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum-12 Alleviates Intestinal Inflammation and Colon Cancer Symptoms by Modulating the Gut Microbiome and Metabolites of C57BL/6 Mice Treated by Azoxymethane/Dextran Sulfate Sodium Salt. Foods 2021, 10, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, Q.; Yu, B.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Xie, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, S. Lysates of Lactobacillus Acidophilus Combined with CTLA-4-Blocking Antibodies Enhance Antitumor Immunity in a Mouse Colon Cancer Model. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 20128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.-J.; Hung,Chien-Min; Yang,Ai-Jen; Hou,Cheng-Yu; Chou,Hung-Wen; Chang,Yi-Chung; Chu,Wen-Cheng; Huang,Wen-Yen; Kuo,Wen-Chih; Yang,Chia-Chun; et al. MS-20 Enhances the Gut Microbiota-Associated Antitumor Effects of Anti-PD1 Antibody. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2380061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliero, M.; Cuisiniere, T.; Ajayi, A.S.; Gerkins, C.; Hajjar, R.; Fragoso, G.; Calvé, A.; Vennin Rendos, H.; Mathieu-Denoncourt, A.; Dagbert, F.; et al. Putrescine Supplementation Limits the Expansion of Pks+ Escherichia Coli and Tumor Development in the Colon. Cancer Research Communications 2024, 4, 1777–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, L.; Yang, G.; Gao, Y.; Li, F.; Li, S. Anticancer Effects of Weizmannia Coagulans MZY531 Postbiotics in CT26 Colorectal Tumor-Bearing Mice by Regulating Apoptosis and Autophagy. Life 2024, 14, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Duan, X.; Lei, X. 3D Cell Culture Model: From Ground Experiment to Microgravity Study. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevers, H. Modeling Development and Disease with Organoids. Cell 2016, 165, 1586–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Knoblich, J.A. Organogenesis in a Dish: Modeling Development and Disease Using Organoid Technologies. Science 2014, 345, 1247125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drost, J.; Clevers, H. Organoids in Cancer Research. Nat Rev Cancer 2018, 18, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuki, K.; Cheng, N.; Nakano, M.; Kuo, C.J. Organoid Models of Tumor Immunology. Trends in Immunology 2020, 41, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnalzger, T.E.; de Groot, M.H.; Zhang, C.; Mosa, M.H.; Michels, B.E.; Röder, J.; Darvishi, T.; Wels, W.S.; Farin, H.F. 3D Model for CAR-mediated Cytotoxicity Using Patient-derived Colorectal Cancer Organoids. The EMBO Journal 2019, 38, e100928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkstra, K.K.; Cattaneo, C.M.; Weeber, F.; Chalabi, M.; Haar, J. van de; Fanchi, L.F.; Slagter, M.; Velden, D.L. van der; Kaing, S.; Kelderman, S.; et al. Generation of Tumor-Reactive T Cells by Co-Culture of Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes and Tumor Organoids. Cell 2018, 174, 1586–1598.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, I.S.; Cardoso Galante, R.S.; Dua, K.; Malipeddi, V.R.; Awasthi, R.; Ghisleni, D.D.M.; de Jesus Andreoli Pinto, T. Hydrogel Based Drug Delivery Systems: A Review with Special Emphasis on Challenges Associated with Decontamination of Hydrogels and Biomaterials. Curr Drug Deliv 2017, 14, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Huh, K.M.; Kang, S.-W. Applications of Biomaterials in 3D Cell Culture and Contributions of 3D Cell Culture to Drug Development and Basic Biomedical Research. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Cheng, P.; Liu, M.; Prakash, S.; Han, J.; Ding, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z. Dynamic Crosslinked and Injectable Biohydrogels as Extracellular Matrix Mimics for the Delivery of Antibiotics and 3D Cell Culture. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 19587–19599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.N.; Ingber, D.E. Microfluidic Organs-on-Chips. Nat Biotechnol 2014, 32, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puschhof, J.; Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C.; Clevers, H. Organoids and Organs-on-Chips: Insights into Human Gut-Microbe Interactions. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Stange, D.E.; Ferrante, M.; Vries, R.G.J.; Van Es, J.H.; Van den Brink, S.; Van Houdt, W.J.; Pronk, A.; Van Gorp, J.; Siersema, P.D.; et al. Long-Term Expansion of Epithelial Organoids from Human Colon, Adenoma, Adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s Epithelium. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1762–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartfeld, S. Modeling Infectious Diseases and Host-Microbe Interactions in Gastrointestinal Organoids. Dev Biol 2016, 420, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, I.; Dutta, D.; Schaefer, D.A.; Iakobachvili, N.; Artegiani, B.; Sachs, N.; Boonekamp, K.E.; Bowden, G.; Hendrickx, A.P.A.; Willems, R.J.L.; et al. Modelling Cryptosporidium Infection in Human Small Intestinal and Lung Organoids. Nat Microbiol 2018, 3, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z. Comparative Analysis of Organoid, Air-Liquid Interface, and Direct Infection Models for Studying Pathogen-Host Interactions in Endometrial Tissue. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 8531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, M.J.; Gleeson, J.P.; Troisi, E.J.; Estrada, H.Q.; Kerns, S.J.; Hinojosa, C.D.; Hamilton, G.A.; Targan, S.R.; Svendsen, C.N.; Barrett, R.J. Enhanced Utilization of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Human Intestinal Organoids Using Microengineered Chips. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 5, 669–677.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimura, N.; Li, Q.; Chu, E.S.H.; Lau, H.C.H.; Fong, W.; Liu, W.; Liang, C.; Nakatsu, G.; Su, A.C.Y.; Coker, O.O.; et al. Lactobacillus Gallinarum Modulates the Gut Microbiota and Produces Anti-Cancer Metabolites to Protect against Colorectal Tumourigenesis. Gut 2022, 71, 2011–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Sung, M.-H.; Kang, H.-T.; Lee, J.H. Establishment of an Apical-Out Organoid Model for Directly Assessing the Function of Postbiotics. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2024, 34, 2184–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jung,Kwang Bo; Kwon,Ohman; Son,Ye Seul; Choi,Eunho; Yu,Won Dong; Son,Naeun; Jeon,Jun Hyoung; Jo,Hana; Yang,Haneol; et al. Limosilactobacillus Reuteri DS0384 Promotes Intestinal Epithelial Maturation via the Postbiotic Effect in Human Intestinal Organoids and Infant Mice. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2121580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furone, F.; Bellomo, C.; Carpinelli, M.; Nicoletti, M.; Hewa-Munasinghege, F.N.; Mordaa, M.; Mandile, R.; Barone, M.V.; Nanayakkara, M. The Protective Role of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG Postbiotic on the Alteration of Autophagy and Inflammation Pathways Induced by Gliadin in Intestinal Models. Front. Med. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, A.W.F.; van der Lugt, B.; Duivenvoorde, L.P.M.; Vos, A.P.; Bastiaan-Net, S.; Tomassen, M.M.M.; Verbokkem, J.A.C.; Blok-Heimerikx, E.; Hooiveld, G.J.E.J.; van Baarlen, P.; et al. Comparison of IPSC-Derived Human Intestinal Epithelial Cells with Caco-2 Cells and Human in Vivo Data after Exposure to Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum WCFS1. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 26464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharuddin, L.; Mokhtar, N.M.; Muhammad Nawawi, K.N.; Raja Ali, R.A. A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial of Probiotics in Post-Surgical Colorectal Cancer. BMC Gastroenterology 2019, 19, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajramagic, S.; Hodzic, E.; Mulabdic, A.; Holjan, S.; Smajlovic, S.V.; Rovcanin, A. Usage of Probiotics and Its Clinical Significance at Surgically Treated Patients Sufferig from Colorectal Carcinoma. Med Arch 2019, 73, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, F.; Adewiah, S.; Fatchiyah, F. The Level Short Chain Fatty Acids and HSP 70 in Colorectal Cancer and Non-Colorectal Cancer. Acta Inform Med 2018, 26, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Sadaghian Sadabad, M.; Gabarrini, G.; Lisotto, P.; von Martels, J.Z.H.; Wardill, H.R.; Dijkstra, G.; Steinert, R.E.; Harmsen, H.J.M. Riboflavin Supplementation Promotes Butyrate Production in the Absence of Gross Compositional Changes in the Gut Microbiota. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2023, 38, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Li, S.; Chen, W.; Han, Y.; Yao, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, Q.; Xiao, Q.; Wei, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. Postoperative Probiotics Administration Attenuates Gastrointestinal Complications and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis Caused by Chemotherapy in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Nutrients 2023, 15, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Argenio, G.; Mazzacca, G. Short-Chain Fatty Acid in the Human Colon. In Advances in Nutrition and Cancer 2; Zappia, V., Della Ragione, F., Barbarisi, A., Russo, G.L., Iacovo, R.D., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1999; pp. 149–158 ISBN 978-1-4757-3230-6.

- Compare, D.; Nardone, G. Contribution of Gut Microbiota to Colonic and Extracolonic Cancer Development. Digestive Diseases 2011, 29, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Zeng, W.; Li, L.; Huo, D.; Zeng, L.; Tan, J.; Zhou, J.; Sun, J.; Liu, G.; Li, Y.; et al. PLGA-PNIPAM Microspheres Loaded with the Gastrointestinal Nutrient NaB Ameliorate Cardiac Dysfunction by Activating Sirt3 in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Advanced Science 2016, 3, 1600254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino, A.D.; Morera, R.; Ciccocioppo, R.; Cazzola, P.; Gotti, S.; Tinozzi, F.P.; Tinozzi, S.; Corazza, G.R. Oral Butyrate for Mildly to Moderately Active Crohn’s Disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2005, 22, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S.-T.; Suydam, I.T.; Woodrow, K.A. Prodrug Approaches for the Development of a Long-Acting Drug Delivery Systems. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2023, 198, 114860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorin, M.J.; Yuan, Z.-M.; Sentz, D.L.; Plaisance, K.; Eiseman, J.L. Plasma Pharmacokinetics of Butyrate after Intravenous Administration of Sodium Butyrate or Oral Administration of Tributyrin or Sodium Butyrate to Mice and Rats. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1999, 43, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, A.; Rowinsky, E.K.; Villalona, M.A.; Hammond, L.A.; Britten, C.D.; Siu, L.L.; Goetz, A.; Felton, S.A.; Burton, S.; Valone, F.H.; et al. A Phase I Study of Pivaloyloxymethyl Butyrate, a Prodrug of the Differentiating Agent Butyric Acid, in Patients with Advanced Solid Malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 2002, 8, 2142–2148. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, R.; Santarcangelo, C.; Badolati, N.; Sommella, E.; De Filippis, A.; Dacrema, M.; Campiglia, P.; Stornaiuolo, M.; Daglia, M. In Vivo Bioavailability and in Vitro Toxicological Evaluation of the New Butyric Acid Releaser N-(1-Carbamoyl-2-Phenyl-Ethyl) Butyramide. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 137, 111385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annison, G.; Illman, R.J.; Topping, D.L. Acetylated, Propionylated or Butyrylated Starches Raise Large Bowel Short-Chain Fatty Acids Preferentially When Fed to Rats. The Journal of Nutrition 2003, 133, 3523–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, K.J.; Saad, S.; Tillett, B.J.; McGuire, H.M.; Bordbar, S.; Yap, Y.A.; Nguyen, L.T.; Wilkins, M.R.; Corley, S.; Brodie, S.; et al. Metabolite-Based Dietary Supplementation in Human Type 1 Diabetes Is Associated with Microbiota and Immune Modulation. Microbiome 2022, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toden, S.; Lockett,Trevor J; Topping,David L; Scherer,Benjamin L; Watson,Emma-Jane L; Southwood,Jessica G; and Clarke, J. M. Butyrylated Starch Affects Colorectal Cancer Markers Beneficially and Dose-Dependently in Genotoxin-Treated Rats. Cancer Biology & Therapy 2014, 15, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.M.; Young, G.P.; Topping, D.L.; Bird, A.R.; Cobiac, L.; Scherer, B.L.; Winkler, J.G.; Lockett, T.J. Butyrate Delivered by Butyrylated Starch Increases Distal Colonic Epithelial Apoptosis in Carcinogen-Treated Rats. Carcinogenesis 2012, 33, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianzani, C.; Foglietta, F.; Ferrara, B.; Rosa, A.C.; Muntoni, E.; Gasco, P.; Pepa, C.D.; Canaparo, R.; Serpe, L. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Delivering Anti-Inflammatory Drugs to Treat Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Effects in an in Vivo Model. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2017, 23, 4200–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Kinashi, Y.; Li, J.; Yoshikawa, T.; Kishimura, A.; Tanaka, M.; Matsui, T.; Mori, T.; Hase, K.; Katayama, Y. Polyvinyl Butyrate Nanoparticles as Butyrate Donors for Colitis Treatment. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 2335–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, R.; Kang, Z.; Cao, Z.; Liu, N.; Shen, J.; Wang, C.; Pan, F.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. Delivery of Short Chain Fatty Acid Butyrate to Overcome Fusobacterium Nucleatum-Induced Chemoresistance. Journal of Controlled Release 2023, 363, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cao, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, B.; Walker, W.A.; Acra, S.A.; Yan, F. Activation of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mediates Mucin Production Stimulated by P40, a Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG-Derived Protein *. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2014, 289, 20234–20244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; and Polk, D.B. Characterization of a Probiotic-Derived Soluble Protein Which Reveals a Mechanism of Preventive and Treatment Effects of Probiotics on Intestinal Inflammatory Diseases. Gut Microbes 2012, 3, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, Y.; Wan, Y.; Hu, T.; Liu, L.; Yang, S.; Gong, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Wei, Y.; Yang, W.; et al. A Novel Postbiotic From Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG With a Beneficial Effect on Intestinal Barrier Function. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criterion | Decision | |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

| Default keywords and search terms exist as a whole or at least in the title, keywords, or abstract of the article | × | |

| The article is published in a peer-review scientific journal | × | |

| The article is written in English | × | |

| Studies where terms were referred to prebiotics, however supernatant/heat-killed cultures were used for testing/assessing | × | |

| Studies on diseases considered high risk factors for colorectal cancer and a relevant study model was developed/used | × | |

| Duplicate records | × | |

| The full text is not available | × | |

| Articles published before 2010 | × | |

| Only testing live microorganisms | × | |

| Studies on gut microbiota transplantation | × | |

| ID | Model | Study type | Microorganism Strain/Species |

Molecules of interest | Events | Pathway/Gene involved | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HCT-116 | in vitro | Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | cell free supernatant | decreasing matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and increasing the tight junction protein zona occludens-1 (ZO-1) levels | cell invasion | [131] | |

| 2 | HT-29 | in vitro | 7 strains of Lactobacillus | cell free supernatant | lactate dehydrogenase regulation | apoptosis | [133] | |

| 3 | HCT-116 HT-29 |

in vitro | synthetic | sodium butyrate | autophagy | LKB1–AMPK pathway | [135] | |

| 4 | HT-29 | in vitro |

Lactobacillus plantarum |

bacteriocins | antiproliferative effect | apoptosis | study on several cancer cell lines | [136] |

| 5 | Caco-2 | in vitro |

Lactobacillus acidophilus |

exopolysaccharide | upregulation of the expression of PPAR-γ | [138] | ||

| 6 | HT-29 HCT-116 |

in vitro | Propionibacterium freudenreichii | culture supernatant, metabolites (propionate/acetate) | increased pro-apoptotic gene expression (TRAIL-R2/DR5) and decreased anti-apoptotic gene expression (FLIP, XIAP); death receptors (TRAIL-R1/DR4, TRAIL-R2/DR5) and caspases (caspase-8, -9 and -3) activation; Bcl-2 expression inhibition | extrinsic apoptotic pathway | in combination with TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand (TRAIL) | [139] |

| 7 | LS174T | in vitro | Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium longum | butyrate | dose-dependent increase in mucin protein contents; increased transcriptional levels of MUC3, MUC4, and MUC12 | MAPK signaling pathway | doses: 6 or 9 mM | [140] |

| 8 | scRNA-seq analysis and DEGs analysis HT-29 human dermal fibroblasts |

in silico and in vitro | Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC4356 | cell free supernatant | cell cycle arrest at G1 phase, anti-proliferative and anti-migration effects, anti-proliferative activity on control fibroblasts. | Wnt signaling (SFRP1, SFRP2, SFRP4, MMP7) | [142] | |

| 9 | HT-29 human dermal fibroblast |

in vitro | Bifidobacterium breve and Lactobacillus rhamnosus | cell free supernatant | anti-proliferation, anti-migration, and apoptosis-related effects | apoptosis: Bax/Bcl2/caspase-3; Wnt signaling: RSPO2, NGF, MMP7 | [143] | |

| 10 | Caco-2 | in vitro | Lactobacillus casei | cell free supernatant | tumor cells cytotoxic effect | apoptosis | comparison of probiotic (live), paraprobiotic (heat-killed) and postbiotics (CFS) | [132] |

| 11 | HT-29 | in vitro | Gluconobacter oxydans strains isolated from Kombucha (KNS30, KNS31, KNS32, K1, and K2) | gluconic acid, glucuronic acid, acetic acid, pyruvic acid, fumaric acid, and lactic acid |

tumor cells cytotoxic effect | apoptotic/necrotic: annexin V and PI positive | study also on gastric cell line: AGS; HUVEC cell lines used as control | [144] |

| 12 | HT-29 HCT-116 |

in vitro | Lactobacillus lactis | cell free supernatant | depletion of arginine, decreased levels of c-Myc, reduced phosphorylation of p70-S6 kinase | cell cycle arrest | [134] | |

| 13 | NCM460 Caco-2 HT-29 |

in vitro | Lacticaseibacillus paracasei and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | heat-inactivated cultures | downregulation of Orai1 and STIM1 | FAK pathway (Store-operated calcium entry) | [137] | |

| 14 | HT-29 | in vitro | Saccharomyces boulardii | cell free supernatant | increased expression of Caspase3 and PTEN genes; decreased expression of RelA and Bcl-XL genes | apoptosis | [117] | |

| 15 | HT-29 Fnevs infection model | in vitro | Bifidobacterium longum | cell free supernatant | inhibition of proliferation, migration and invasion | inhibitory effects on the expression of specific oncogenes (e.g., Myc, IL16, KCNN2, ACSBG1, Pum1, MET, NR5A2) | controversial results | [141] |

| 16 | mouse colon carcinoma CT26.WT tumor cells were injected subcutaneously - BALB/c mice | in vivo | Weizmannia coagulans MZY531 | powder of W. coagulans MZY531; oligosaccharidesuspension | inhibiting tumor growth by modulating apoptosis and autophagy in tumor cells | apoptosis: Bax/Bcl2/caspase-3 & JAK2/STAT3 Autophagy: PI3K/AKT/mTOR & TGF-β/SMAD4 | [151] | |

| 17 | Sprague–Dawley rats | in vivo | Lactobacillus rhamnosus MD 14 | metabiotic extract (acetate, butyrate, propionate, acetamide, thiocyanic acid, and oxalic acid) | downregulation of oncogenes (K-ras, β-catenin, Cox-2, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)] and upregulation tumor suppressor p53 gene leading to almost normal colon histology | Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway | active components in the metabiotic extract were characterized byLC-MS | [146] |

| 18 | xenograft mousemodel CT-26 cells subcutaneously injected into BALB/c mice |

in vivo ex vivo |

multiple strains of probiotics and yeast | MS-20 “Symbiota®” in combination with anti-programmed cell death 1 (PD1) antibody | inhibited colon and lung cancer growth | CD8+ T cells and PD1 expression | fecal samples from six patients were used for ex vivo evaluation | [149] |

| 19 | C57BL/6 mouse model where cancer was induced via AOM/DSS administration | in vivo | Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 | putrescine | inhibit the growth of thepathogenic strain pks+ E. coli NC101; reduced the number and size of colonic tumors, regulation of inflammatory cytokines; shift in the composition of gut microbiota | cell proliferation; fecal Lcn-2 marker of inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases, TNFα, IL6 and IL10; 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing | [150] | |

| 20 | xenograft models obtained by injecting SW620 cells into male BALB/c nude mice Caco-2/bbe SKCO-1 SW620 |

in vivo in vitro |

Lactobacillus casei ATCC334 | ferrichrome | activation of the JNK-DDIT3-mediated apoptotic pathway | JNK-DDIT3-mediated apoptotic pathway | effect of ferrichrome was compared with 5-FU and cisplatin | [119] |

| 21 | C57BL/6 mouse model where cancer was induced via AOM/DSS administration | in vivo | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum-12 | exopolysaccharide | activation of caspase cascade and NF-κB signaling (IκB-α, p65, p-p65, p38, and p-p38) | inflammatory signaling and apoptosis | additional untargeted fecal metabolomic analysis | [147] |

| 22 | BALB/c mice CRC models induced via AOM/DSS administration | in vivo | Lactobacillus acidophilus | lysates | increased CD8 + T cell and effector memory T cells, decreased Treg and M2 macrophages | TLR signaling pathway | combination with CTLA-4-blocking antibodies | [148] |

| 23 | C57B/6 mice model CRC cell lines organoids from CRC patients |

in vitro in vivo organoids |

Lactobacillus gallinarum | cell free supernatant (indole-3-lactictate most enriched metabolite) | antitumorigenic role: proliferation, apoptosis, cell cycle distribution, gut microbiota modulation |

cell proliferation apoptosis |

[169] | |

| 24 | Organoids derived from C57BL/6 male mice small intestines and colon |

in vitro in vivo organoids |

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum KM2 & Bacillusvelezensis KMU01 | cell free supernatant | inflammatory response LPS-induced and mitochondrial homeostasis through mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis | COX-2 decreased; expression of tight-junctionmarkers ZO-1, claudin, and occludin increased, and expression of mitochondrial homeostasisfactors PINK1, parkin, and PGC1a also increased. | [170] | |

| 25 | hPSC-derived intestinal organoids C57BL Mice Caco-2 |

in vitro in vivo organoids |

Limosilactobacillus reuteri DS0384 | N-carbamyl glutamic acid (NCG) | intestinal epithelial maturation; inflammatory response and intestinal epithelial barrier integrity | mature specific marker: (CDX2), (OLFM4), (DEFA5 and LYZ), (KRT20, CREB3L3, DPP4, LCT, SLC5A1, and MUC13); Inflammatory pathway: (IFNγ)/TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα; localization of zonula occludens-1 | [171] | |

| 26 | Caco-2 organoids derived from celiac disease patientbiopsies |

in vitro organoids |

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | cell free supernatant | alteration of autophagy and inflammation pathways induced by gliadin in Celiac disease (CD) |

mTOR pathway: phosphorylation of p70S6K, p4EBP-1; inflammatory marker: NF- kb; autophagy: LC3II and p62 protein, SQSTM1 autophagosome membrane marker |

[172] | |

| 27 | Caco-2 hiPSC derived IEC monolayers |

in vitro advanced patient-derived in vitro |

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | heat-killed | inflammatory response | IL-8, REG3α and HBD2 | [173] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).