Submitted:

01 November 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

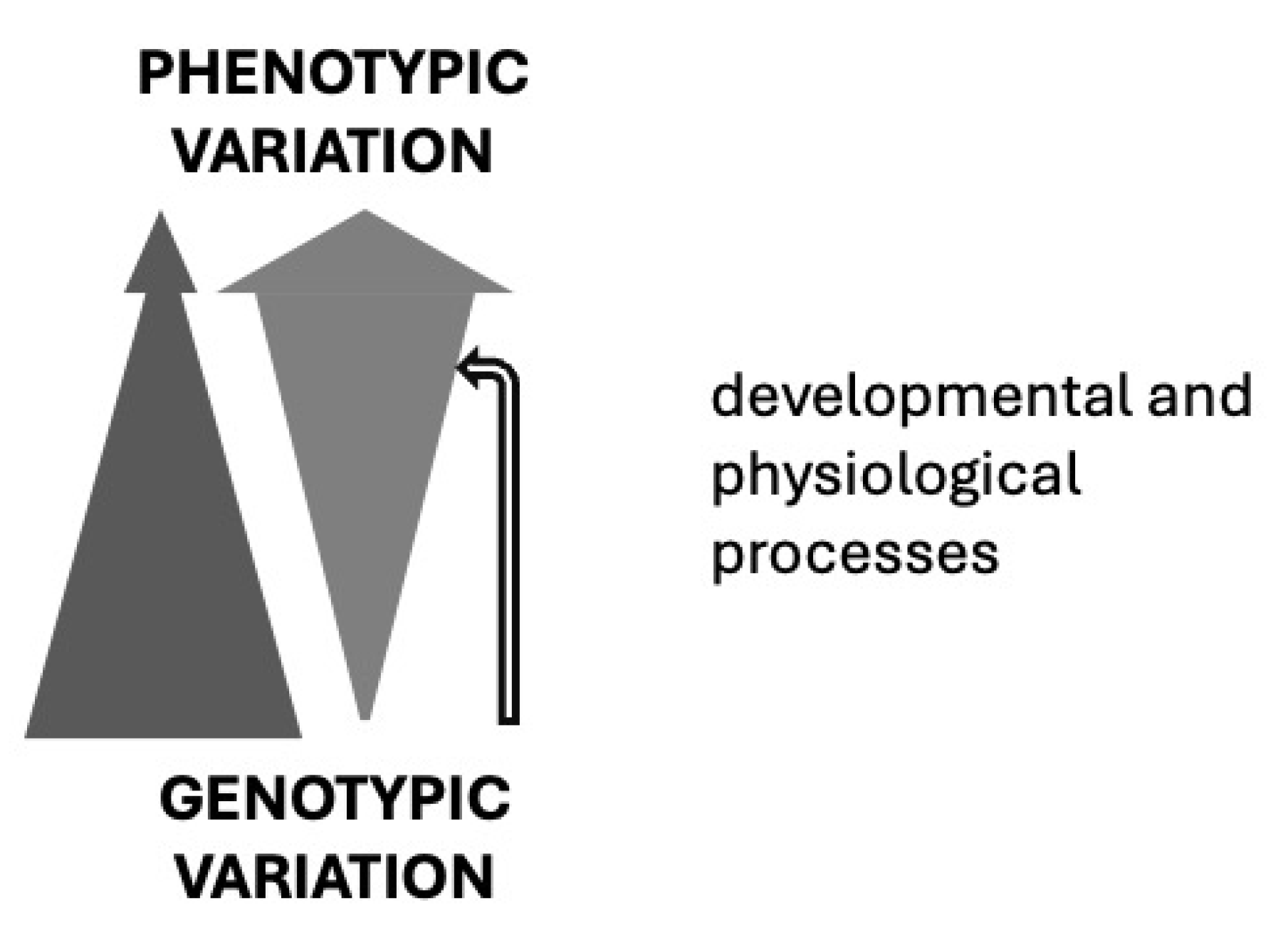

“Quantitative-genetic models may become more informative and predictive if variation in their parameters can be explained by developmental and other biological processes that have been shaped by the previous history of the population.” Bruce Riska, 1989, Evolution

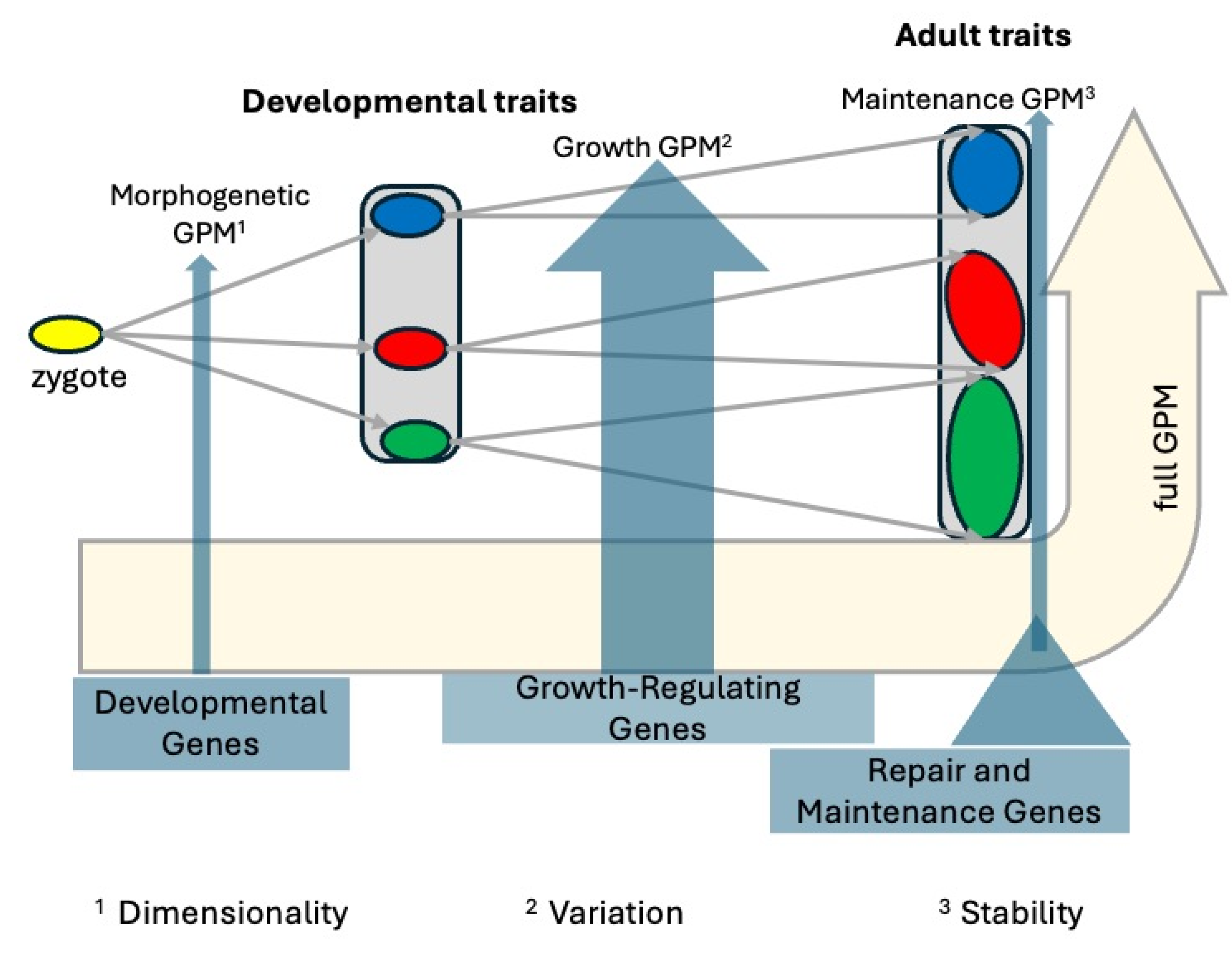

- Not a Unitary Map: Decomposing the GP Map by the Process Type

- a. GP Maps of Morphogenetic Patterning Processes

- b. GP Maps of Growth Processes

- c. GP Maps of Core Maintenance Metabolism

- d. Developmental Interdependence of the Processes

2. Tripartite GP Map and Microevolutionary Theory

3. Tripartite GP Map and Macroevolution

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Acknowledgments

References

- Al-Mosleh, S., G. P. T. Choi, A. Abzhanov and L. Mahadevan. 2021. Geometry and dynamics link form, function, and evolution of finch beaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118(46). [CrossRef]

- Alberch, P. 1986. Rules of Invariance in Evolutionary Morphology: The Organization of the Vertebrate Skull. Evolution 40(4): 881-882.

- Alberch, P. and J. Alberch. 1981. Heterochronic mechanisms of morphological diversification and evolutionary change in the neotropical salamander, Bolitoglossa occidentalis (Amphibia: Plethodontidae). J Morphol 167(2): 249-264. [CrossRef]

- Alberch, P. and E. A. Gale. 1985. A Developmental Analysis of an Evolutionary Trend: Digital Reduction in Amphibians. Evolution 39(1): 8-23.

- Amundson, R. 2005. The changing role of the embryo in evolutionary thought : roots of evo-devo. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; New York.

- Arthur, W. 1997. The origin of animal body plans : a study in evolutionary developmental biology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K. ; New York, NY, USA. [CrossRef]

- Atchley, W. R. and B. K. Hall. 1991. A model for development and evolution of complex morphological structures. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 66:101-157. [CrossRef]

- Baatz, M. and G. P. Wagner. 1997. Adaptive inertia caused by hidden pleiotropic effects. Theoretical Population Biology 51(1): 49-66. [CrossRef]

- Bégin, M. and D. A. Roff. 2003. The constancy of the G matrix through species divergence and the effects of quantitative genetic constraints on phenotypic evolution: a case study in crickets. Evolution 57(5): 1107-1120.

- Bégin, M. and D. A. Roff. 2004. From micro- to macroevolution through quantitative genetic variation: positive evidence from field crickets. Evolution 58(10): 2287-2304.

- Bell, G. and A. Mooers. 1997. Size and complexity among multicellular organisms. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 345–363.

- Bonner, J. T. 1988. The evolution of complexity by means of natural selection. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

- Bonner, J. T. 2004. Perspective: the size-complexity rule. Evolution 58:1883-1890.

- Bourg, S., G. H. Bolstad, D. V. Griffin, C. Pélabon, and T. F. Hansen. 2024. Directional epistasis is common in morphological divergence. Evolution 78:934-950. [CrossRef]

- Carter, A. J., J. Hermisson, and T. F. Hansen. 2005. The role of epistatic gene interactions in the response to selection and the evolution of evolvability. Theor Popul Biol 68:179-196. [CrossRef]

- Cheverud, J. M. 1982a. Phenotypic, Genetic, and Environmental Morphological Integration in the Cranium. Evolution 36:499-516.

- Cheverud, J. M. 1982b. Relationships among ontogenetic, static, and evolutionary allometry. Am J Phys Anthropol 59:139-149. [CrossRef]

- Cheverud, J. M. 1984. Quantitative genetics and developmental constraints on evolution by selection. J Theor Biol 110(2): 155-171. [CrossRef]

- Cheverud, J. M., T. H. Ehrich, T. T. Vaughn, S. F. Koreishi, R. B. Linsey, and L. S. Pletscher. 2004. Pleiotropic effects on mandibular morphology II: differential epistasis and genetic variation in morphological integration. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol 302:424-435. [CrossRef]

- Cheverud, J. M. and E. J. Routman. 1995. Epistasis and its contribution to genetic variance components. Genetics 139:1455-1461. [CrossRef]

- Cheverud, J. M. and E. J. Routman. 1996. Epistasis as a Source of Increased Additive Genetic Variance at Population Bottlenecks. Evolution 50:1042-1051.

- Cheverud, J. M., E. J. Routman, F. A. Duarte, B. van Swinderen, K. Cothran, and C. Perel. 1996. Quantitative trait loci for murine growth. Genetics 142:1305-1319. [CrossRef]

- Cheverud, J. M., J. J. Rutledge, and W. R. Atchley. 1983. Quantitative Genetics of Development: Genetic Correlations among Age-Specific Trait Values and the Evolution of Ontogeny. Evolution 37:895-905. [CrossRef]

- Chevin, L. M., C. Leung, A. Le Rouzic and T. Uller (2022). Using phenotypic plasticity to understand the structure and evolution of the genotype-phenotype map. Genetica 150(3-4): 209-221. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K. L., K. E. Sears, A. Uygur, J. Maier, K. S. Baczkowski, M. Brosnahan, D. Antczak, J. A. Skidmore, and C. J. Tabin. 2014. Patterning and post-patterning modes of evolutionary digit loss in mammals. Nature 511:41-45. [CrossRef]

- de Bakker, M. A., D. A. Fowler, K. den Oude, E. M. Dondorp, M. C. Navas, J. O. Horbanczuk, J. Y. Sire, D. Szczerbińska, and M. K. Richardson. 2013. Digit loss in archosaur evolution and the interplay between selection and constraints. Nature 500:445-448. [CrossRef]

- De Beer, G. 1940. Embryos and ancestors. The Clarendon Press, Oxford,.

- DiFrisco, J. and G. Wagner. 2023. Body plan identity: A mechanistic model. Evolutionary Biology 49:1-19. [CrossRef]

- Draghi, J. A., T. L. Parsons, G. P. Wagner, and J. B. Plotkin. 2010. Mutational robustness can facilitate adaptation. Nature 463:353-355. [CrossRef]

- Falconer, D. S. 1960. Introduction to quantitative genetics. New York,, Ronald Press Co.

- Galis, F., T. J. Van Dooren, J. D. Feuth, J. A. Metz, A. Witkam, S. Ruinard, M. J. Steigenga and L. C. Wijnaendts. 2006. Extreme selection in humans against homeotic transformations of cervical vertebrae. Evolution 60(12): 2643-2654. [CrossRef]

- Galis, F. 2023. Evolvability of Body Plans: On Phylotypic Stages, Developmental Modularity, and an Ancient Metazoan Constraint in T. Hansen, D. Houle, M. Pavlicev, and C. Pelabon, eds. Evolvability. A Unifying Concept in Evolutionary Biology? MIT Press.

- Gjuvsland, A. B., B. J. Hayes, S. W. Omholt, and O. Carlborg. 2007. Statistical epistasis is a generic feature of gene regulatory networks. Genetics 175:411-420. [CrossRef]

- Gjuvsland, A. B., J. O. Vik, D. A. Beard, P. J. Hunter, and S. W. Omholt. 2013. Bridging the genotype-phenotype gap: what does it take? J Physiol 591:2055-2066. [CrossRef]

- Gould, S. J. 1977. Ontogeny and phylogeny. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

- Green, R. M., J. L. Fish, N. M. Young, F. J. Smith, B. Roberts, K. Dolan, I. Choi, C. L. Leach, P. Gordon, J. M. Cheverud, C. C. Roseman, T. J. Williams, R. S. Marcucio and B. Hallgrimsson. 2017. Developmental nonlinearity drives phenotypic robustness. Nat Commun 8(1): 1970. [CrossRef]

- Grimbs, S., J. Selbig, S. Bulik, H. G. Holzhütter and R. Steuer. 2007. The stability and robustness of metabolic states: identifying stabilizing sites in metabolic networks. Mol Syst Biol 3: 146. [CrossRef]

- Haeckel, E. 1875. Die Gastrula und die Eifurchung der Thiere. Jena. Z. Naturwiss.:402–508.

- Hallgrímsson, B. and B. K. Hall. 2005. Variation. Elsevier Academic Press, Amsterdam.

- Hallgrímsson, B., H. Jamniczky, N. M. Young, C. Rolian, T. E. Parsons, J. C. Boughner, and R. S. Marcucio. 2009. Deciphering the Palimpsest: Studying the Relationship Between Morphological Integration and Phenotypic Covariation. Evol Biol 36:355-376. [CrossRef]

- Hammond, J. E., R. E. Baker, and B. Verd. 2025. Modularity of the segmentation clock and morphogenesis. Elife 14.

- Hansen, T. F. and G. P. Wagner. 2001. Modeling genetic architecture: a multilinear theory of gene interaction. Theor Popul Biol 59:61-86. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T. F. 2006. The evolution of genetic architecture. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 37: 123-157.

- Hansen, T. F. and D. Houle. 2008. Measuring and comparing evolvability and constraint in multivariate characters. J Evol Biol 21(5): 1201-1219. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T. F., C. Pelabon and D. Houle. 2011. Heritability is not evolvability. Evolutionary Biology 38: 258-277.

- Hansen, T. F., T. M. Solvin and M. Pavlicev. 2019. Predicting evolutionary potential: A numerical test of evolvability measures. Evolution 73(4): 689-703. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T. F., D. Houle, M. Pavlicev, and C. Pelabon, eds. Evolvability: A Unifying Concept in Evolutionary Biology? MIT Press.2023. Evolvability: a unifying concept in evolutionary biology? Cambridge, Massachusetts, The MIT Press.

- Hendrikse, J. L., T. E. Parsons, and B. Hallgrimsson. 2007. Evolvability as the proper focus of evolutionary developmental biology. Evol Dev 9:393-401. [CrossRef]

- Holstad, A., K. L. Voje, Ø. Opedal, G. H. Bolstad, S. Bourg, T. F. Hansen, and C. Pélabon. 2024. Evolvability predicts macroevolution under fluctuating selection. Science 384:688-693. [CrossRef]

- Holstad, A. 2025. Understanding evolvability and its implications for evolution. Doctoral Thesis at NTNU Trondheim, Institut for biologi. https://hdl.handle.net/11250/3177820.

- Houle, D., G. H. Bolstad, K. van der Linde, and T. F. Hansen. 2017. Mutation predicts 40 million years of fly wing evolution. Nature 548:447-450. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H., M. Uesaka, S. Guo, K. Shimai, T. M. Lu, F. Li, S. Fujimoto, M. Ishikawa, S. Liu, Y. Sasagawa, G. Zhang, S. Kuratani, J. K. Yu, T. G. Kusakabe, P. Khaitovich, N. Irie and E. Consortium. 2017. Constrained vertebrate evolution by pleiotropic genes. Nat Ecol Evol 1(11): 1722-1730. [CrossRef]

- Huxley, J. 1932. Problems of Relative Growth. Dial Press, New York.

- Irie, N. and A. Sehara-Fujisawa. 2007. The vertebrate phylotypic stage and an early bilaterian-related stage in mouse embryogenesis defined by genomic information. BMC Biol 5:1. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H., B. Tombor, R. Albert, Z. N. Oltvai and A. L. Barabási. 2000. The large-scale organization of metabolic networks. Nature 407(6804): 651-654. [CrossRef]

- Kacser, H. and J. A. Burns. 1981. The molecular basis of dominance. Genetics 97(3-4): 639-666.

- Lande, R. 1978. Evolutionary mechanisms of limb loss in tetrapods. Evolution 32:73-92.

- Lande, R. 1979. Quantitative Genetic Analysis of Multivariate Evolution, Applied to Brain:Body Size Allometry. Evolution 33:402-416. [CrossRef]

- Le Rouzic, A., M. Roumet, A. Widmer and J. Clo. 2024. Detecting directional epistasis and dominance from cross-line analyses in alpine populations of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Evol Biol 37(7): 839-847. [CrossRef]

- Loison, L. 2025. Beyond Lamarckism : plasticity in Darwinian evolution, 1890-1970. History and philosophy of biology. London ; New York, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Lynch, M. 2010. Evolution of the mutation rate. Trends Genet 26:345-352. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M. and B. Walsh. 1998. Genetics and analysis of quantitative traits. Sunderland, Mass., Sinauer.

- Mallard, F., B. Afonso, H. Teotónio. 2023. Selection and the direction of phenotypic evolution. eLife 12: e80993. [CrossRef]

- Marchini, M. and C. Rolian. 2018. Artificial selection sheds light on developmental mechanisms of limb elongation. Evolution 72:825-837. [CrossRef]

- Marroig, G. and J. Cheverud (2010). Size as a line of least resistance II: direct selection on size or correlated response due to constraints? Evolution 64(5): 1470-1488. [CrossRef]

- Marroig, G. and J. M. Cheverud (2005). Size as a line of least evolutionary resistance: diet and adaptive morphological radiation in New World monkeys. Evolution 59(5): 1128-1142.

- Mayer, C. and T. F. Hansen. 2017. Evolvability and robustness: A paradox restored. J Theor Biol 430:78-85. [CrossRef]

- McNamara, K. I. 1988. Patterns of heterochrony in the fossil record. Trends Ecol Evol 3(7): 176-180. [CrossRef]

- Meiklejohn, C. D. and D. L. Hartl. 2002. A single mode of canalization. 17:468-473. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R. D., M. Mohammadi, and N. Rahimi. 2006. A single amino acid substitution in the activation loop defines the decoy characteristic of VEGFR-1/FLT-1. J Biol Chem 281:867-875. [CrossRef]

- Milocco, L. and I. Salazar-Ciudad. 2020. Is evolution predictable? Quantitative genetics under complex genotype-phenotype maps. Evolution 74(2): 230-244. [CrossRef]

- Mosleh, S., G. P. T. Choi, G. M. Musser, H. F. James, A. Abzhanov and L. Mahadevan. 2023. Beak morphometry and morphogenesis across avian radiations. Proc Biol Sci 290(2007): 20230420. [CrossRef]

- Mousseau, T. A. and D. A. Roff. 1987. Natural selection and the heritability of fitness components. Heredity (Edinb) 59 ( Pt 2): 181-197.

- Nijhout, H. F., M. C. Reed, P. Budu, and C. M. Ulrich. 2004. A mathematical model of the folate cycle: new insights into folate homeostasis. J Biol Chem 279:55008-55016.

- Orr, H. A. 2000. Adaptation and the cost of complexity. Evolution 54(1): 13-20.

- Pavlicev, M., S. Bourg, and A. Le Rouzic. 2023. The Genotype-Phenotype Map Structure and its Role in Evolvability in T. Hansen, D. Houle, M. Pavlicev, and C. Pelabon, eds. Evolvability: A Unifying Concept in Evolutionary Biology? MIT Press.

- Pavlicev, M. and T. F. Hansen. 2011. Genotype-phenotype map maximizing evolvability: Modularity revisited. Evolutionary Biology 38(4): 371-389. [CrossRef]

- Pavlicev, M. and J. Cheverud. 2015. Constraints Evolve: Context Dependency of Gene Effects Allows Evolution of Pleiotropy. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 46:413-434. [CrossRef]

- Pavlicev, M., J. M. Cheverud, and G. P. Wagner. 2011. Evolution of adaptive phenotypic variation patterns by direct selection for evolvability. Proc Biol Sci 278:1903-1912. [CrossRef]

- Pavlicev, M., J. DiFrisco, A. C. Love, and G. P. Wagner. 2024. Metabolic complementation between cells drives the evolution of tissues and organs. Biol Lett 20:20240490.

- Pavlicev, M., J. P. Kenney-Hunt, E. A. Norgard, C. C. Roseman, J. B. Wolf, and J. M. Cheverud. 2008. Genetic variation in pleiotropy: differential epistasis as a source of variation in the allometric relationship between long bone lengths and body weight. Evolution 62:199-213.

- Pavlicev, M., A. Le Rouzic, J. M. Cheverud, G. P. Wagner, and T. F. Hansen. 2010. Directionality of epistasis in a murine intercross population. Genetics 185:1489-1505. [CrossRef]

- Pavlicev, M., J. P. Kenney-Hunt, E. A. Norgard, C. C. Roseman, J. B. Wolf and J. M. Cheverud. 2008. Genetic variation in pleiotropy: differential epistasis as a source of variation in the allometric relationship between long bone lengths and body weight. Evolution 62(1): 199-213. [CrossRef]

- Piasecka, B., P. Lichocki, S. Moretti, S. Bergmann, and M. Robinson-Rechavi. 2013. The hourglass and the early conservation models--co-existing patterns of developmental constraints in vertebrates. PLoS Genet 9:e1003476. [CrossRef]

- Raff, R. A. 1996. The shape of life: genes, development, and the evolution of animal form. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Reed, M., J. Best, M. Golubitsky, I. Stewart, and H. F. Nijhout. 2017. Analysis of Homeostatic Mechanisms in Biochemical Networks. Bull Math Biol 79:2534-2557.

- Reed, M. C., R. L. Thomas, J. Pavisic, S. J. James, C. M. Ulrich, and H. F. Nijhout. 2008. A mathematical model of glutathione metabolism. Theor Biol Med Model 5:8. [CrossRef]

- Rhoda, D. P., A. Haber and K. D. Angielczyk. 2023. Diversification of the ruminant skull along an evolutionary line of least resistance. Sci Adv 9(9): eade8929.

- Riedl, R. 1978. Order in living organisms : a systems analysis of evolution. Wiley, Chichester; New York.

- Riska, B. 1986. Some models for development, growth, and morphometric correlation. Evolution 40:1303-1311.

- Riska, B. 1989. Composite traits, selection response, and evolution. Evolution 43:1172-1191.

- Riska, B. and W. R. Atchley. 1985. Genetics of growth predict patterns of brain-size evolution. Science 229:668-671.

- Riska, B., W. R. Atchley, and J. J. Rutledge. 1984. A genetic analysis of targeted growth in mice. Genetics 107:79-101.

- Roff, D. A. 1997. Evolutionary Quantitative Genetics. Chapman & Hall, New York.

- Roff, D. A. and T. A. Mousseau. 1987. Quantitative genetics and fitness: lessons from Drosophila. Heredity (Edinb) 58 ( Pt 1): 103-118.

- Roff, D.1981. On Being the Right Size. Am. Nat. 118 (3).

- Rohner, P. T. and D. Berger. 2023. Developmental bias predicts 60 million years of wing shape evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 120:e2211210120. [CrossRef]

- Rohner, P. T. and D. Berger. 2025. Macroevolution along developmental lines of least resistance in fly wings. Nat Ecol Evol 9:639-651. [CrossRef]

- Saito, K., M. Tsuboi, and Y. Takahashi. 2024. Developmental noise and phenotypic plasticity are correlated in. Evol Lett 8:397-405. [CrossRef]

- Sander, K. 1983. The evolution of patterning mechanisms: Gleanings from insect embryogenesis and spermatogenesis. Pp. 137-154 in B. Goodwin, N. Holder, and C. Wylie, eds. Development and Evolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Sanger, T. J., E. A. Norgard, L. S. Pletscher, M. Bevilacqua, V. R. Brooks, L. J. Sandell, and J. M. Cheverud. 2011. Developmental and genetic origins of murine long bone length variation. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol 316B:146-161.

- Schluter, D. 1996. Adaptive radiation along genetic lines of least resistance. Evolution 50(5): 1766-1774.

- Schuster, P., W. Fontana, P. F. Stadler and I. L. Hofacker. 1994. From sequences to shapes and back: a case study in RNA secondary structures. Proc Biol Sci 255(1344): 279-284.

- Schut, P. C., T. E. Cohen-Overbeek, F. Galis, C. M. Ten Broek, E. A. Steegers, and A. J. Eggink. 2016. Adverse Fetal and Neonatal Outcome and an Abnormal Vertebral Pattern: A Systematic Review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 71:741-750.

- Schut, P. C., A. J. Eggink, T. E. Cohen-Overbeek, T. J. M. Van Dooren, G. J. de Borst, and F. Galis. 2020. Miscarriage is associated with cervical ribs in thoracic outlet syndrome patients. Early Hum Dev 144:105027.

- Schwenk, K. and P. G. Wagner. 2001. Function and the Evolution of Phenotypic Stability: Connecting Pattern to Process. American Zoologist 41:552-563.

- Shinar G., M. Feinberg. 2010. Structural Sources of Robustness in Biochemical Reaction Networks.Science 327:1389-1391.

- Simpson, G. G. 1944. Tempo and mode in evolution. New York, Columbia University Press.

- Sodini, S. M., K. E. Kemper, N. R. Wray and M. Trzaskowski. 2018. Comparison of Genotypic and Phenotypic Correlations: Cheverud’s Conjecture in Humans. Genetics 209(3): 941-948. [CrossRef]

- Stearns, S.C. 1994. The evolutionary links between fixed and variable traits. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 38, 3/4, 215-232.

- Stelling, J., U. Sauer, Z. Szallasi, F. J. Doyle and J. Doyle. 2004. Robustness of cellular functions. Cell 118(6): 675-685.

- Thompson, D. A. W. 1942. On Growth and Form. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Tickle, C. 2002a. Molecular basis of vertebrate limb patterning. Am J Med Genet 112:250-255.

- Tickle, C. 2002b. Vertebrate limb development and possible clues to diversity in limb form. J Morphol 252:29-37.

- Tickle, C. and M. Towers. 2017. Sonic Hedgehog Signaling in Limb Development. Front Cell Dev Biol 5:14.

- Tsuboi, M., J. Sztepanacz, S. De Lisle, K. L. Voje, M. Grabowski, M. J. Hopkins, A. Porto, M. Balk, M. Pontarp, D. Rossoni, L. S. Hildesheim, Q. J. Horta-Lacueva, N. Hohmann, A. Holstad, M. Lürig, L. Milocco, S. Nilén, A. Passarotto, E. I. Svensson, Christina Villegas, Erica Winslott, Lee Hsiang Liow, Gene Hunt, Alan Love and D. Houle. 2024. The paradox of predictability provides a bridge between micro- and macroevolution. J Evol Biol 37:1413-1432.

- Ulrich, C. M., M. Neuhouser, A. Y. Liu, A. Boynton, J. F. Gregory, B. Shane, S. J. James, M. C. Reed, and H. F. Nijhout. 2008a. Mathematical modeling of folate metabolism: predicted effects of genetic polymorphisms on mechanisms and biomarkers relevant to carcinogenesis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17:1822-1831. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, C. M., M. C. Reed, and H. F. Nijhout. 2008b. Modeling folate, one-carbon metabolism, and DNA methylation. Nutr Rev 66 Suppl 1:S27-30. [CrossRef]

- Uyeda, J. C., T. F. Hansen, S. J. Arnold and J. Pienaar (2011). The million-year wait for macroevolutionary bursts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(38): 15908-15913. [CrossRef]

- von Dassow, G., E. Meir, E. M. Munro, and G. M. Odell. 2000. The segment polarity network is a robust developmental module. Nature 406:188-192.

- Von Dassow, G. and G. M. Odell. 2002. Design and constraints of the Drosophila segment polarity module: robust spatial patterning emerges from intertwined cell state switches. J Exp Zool 294:179-215.

- Waddington, C.H. 1942. Canalization of development and the inheritance of acquired characters. Nature 3811:563.

- Wagner, G. P. 1989. Multivariate mutation-selection balance with constrained pleiotropic effects. Genetics 122(1): 223-234. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A. 2008. Robustness and evolvability: a paradox resolved. Proc Biol Sci 275:91-100. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, G. P. 2023. Models of Contingent Evolvability Suggest Dynamical Instabilities in Body Shape Evolution. In T. Hansen, D. Houle, M. Pavlicev, and C. Pelabon, eds. Evolvability: A Unifying Concept in Evolutionary Biology? MIT Press.

- Wagner, G. P. and L. Altenberg. 1996. Perspective: Complex Adaptations and the Evolution of Evolvability. Evolution 50:967-976.

- Wagner, G. P., G. Booth, and H. Bagheri-Chaichian. 1997. A Population Genetic Theory of Canalization. Evolution 51:329-347.

- Wagner, G. P. and K. Schwenk. 2000. Evolutionarily Stable Configurations: Functional Integration and the Evolution of Phenotypic Stability. Evolutionary Biology 31:155-217.

- Watson, R. A., G. P. Wagner, M. Pavlicev, D. M. Weinreich and R. Mills. 2014. The evolution of phenotypic correlations and developmental memory. Evolution 68(4): 1124-1138. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J. B., L. J. Leamy, E. J. Routman, and J. M. Cheverud. 2005. Epistatic pleiotropy and the genetic architecture of covariation within early and late-developing skull trait complexes in mice. Genetics 171:683-694.

- Wolf, J. B., D. Pomp, E. J. Eisen, J. M. Cheverud, and L. J. Leamy. 2006. The contribution of epistatic pleiotropy to the genetic architecture of covariation among polygenic traits in mice. Evol Dev 8:468-476. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).