1. Introduction

In swine production, the post-weaning period has been identified as one of the most challenging and stressful periods in the life of a piglet due to changes in its environment and feeding regimen. During this period, piglets might undergo infectious challenges with enterotoxigenic

Escherichia coli (ETEC) resulting in post-weaning diarrhea (PWD) [

1] and

Streptococcus suis (

S. suis) leading to polyserositis, including arthritis, peritonitis, pleuritis, pericarditis and meningitis [

2]. Therefore, metaphylactic and curative antimicrobial therapy is frequently applied, which leads to increased treatment incidence per 100 days at risk (TI

100) [

3].

Post-weaning diarrhea (PWD) in pigs remains an economically important disease [

1] and is characterized by reduced piglet performance (i.e. mortality, weight loss, retarded growth, batch-to-batch variation) and increased treatment costs (

i.e. higher antimicrobial use) [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The enterotoxigenic

E. coli (ETEC) pathotype - characterized by the presence of fimbrial adhesins which mediate attachment to porcine intestinal enterocytes, and enterotoxins which disrupt fluid homeostasis in the small intestine - is regarded as the most important cause of PWD. These interactions with the intestinal enterocytes result in mild to severe diarrhea within a few days post-weaning. This is associated with clinical signs of dehydration, loss of body condition (= disappearance of muscle volume) and mortality [

11]. The most commonly occurring virulence factors responsible for the PWD pathology due to ETEC in pigs are the adhesive fimbriae F4 (K88) and F18 [

11]. Other fimbriae such as F5 (K99), F6 (987P) and F41 rarely occur in

E. coli isolates from PWD [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. The other virulence factors are the enterotoxins associated with porcine ETEC namely heat-labile toxin (LT), heat-stable toxin a (STa) and heat-stable toxin b (STb). Some pathogenic strains might produce both enterotoxins and a Shiga toxin (Stx2e) [

11].

The disease is currently controlled using antimicrobials, although the emergence of antimicrobial resistance in

E. coli strains isolated from cases of PWD urges the need for alternative control measures [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Several alternative nutritional strategies such as supplementary dietary fibre, reduction of crude protein level, improved ingredient consistency, addition of pre- and probiotics and acid supplementation have been explored to increase intestinal health and decrease incidence of PWD due to

E. coli in post-weaned piglets [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

Other preventive strategies have recently been explored [

1,

30]. For an

E. coli vaccination against PWD due to F4- and F18-ETEC, it is important to activate the mucosal immunity against F4 and F18 through the local production of F4- and/or F18-specific secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) antibodies. These local antibodies can prevent pathogenic F4- and F18-ETEC from attaching to the intestinal F4- and F18-receptors and thus reduce clinical signs of PWD [

30]. Recently, vaccination with an oral live avirulent

E. coli F4 or

E. coli F4 and F18 vaccine has demonstrated efficacy against PWD due to F4-ETEC and F4- and F18-ETEC [

31,

32]. This immunization resulted in decreased severity and duration of PWD clinical signs and faecal shedding of F4- and F18-ETEC [

31,

32] and increased weight gain in piglets vaccinated with an

E. coli F4 vaccine [

31].

Here, we report the results of an antimicrobial coaching trajectory in a 1000-sow farm with high antimicrobial use during the post-weaning period. For a period of 21 weeks, we evaluated the effect of an oral live non-pathogenic E. coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec® F4F18; Elanco; Indianapolis, IN, USA) for active immunization of piglets against PWD caused by F4- and F18-ETEC on potential reduction of antimicrobial use during the post-weaning period.

3. Discussion

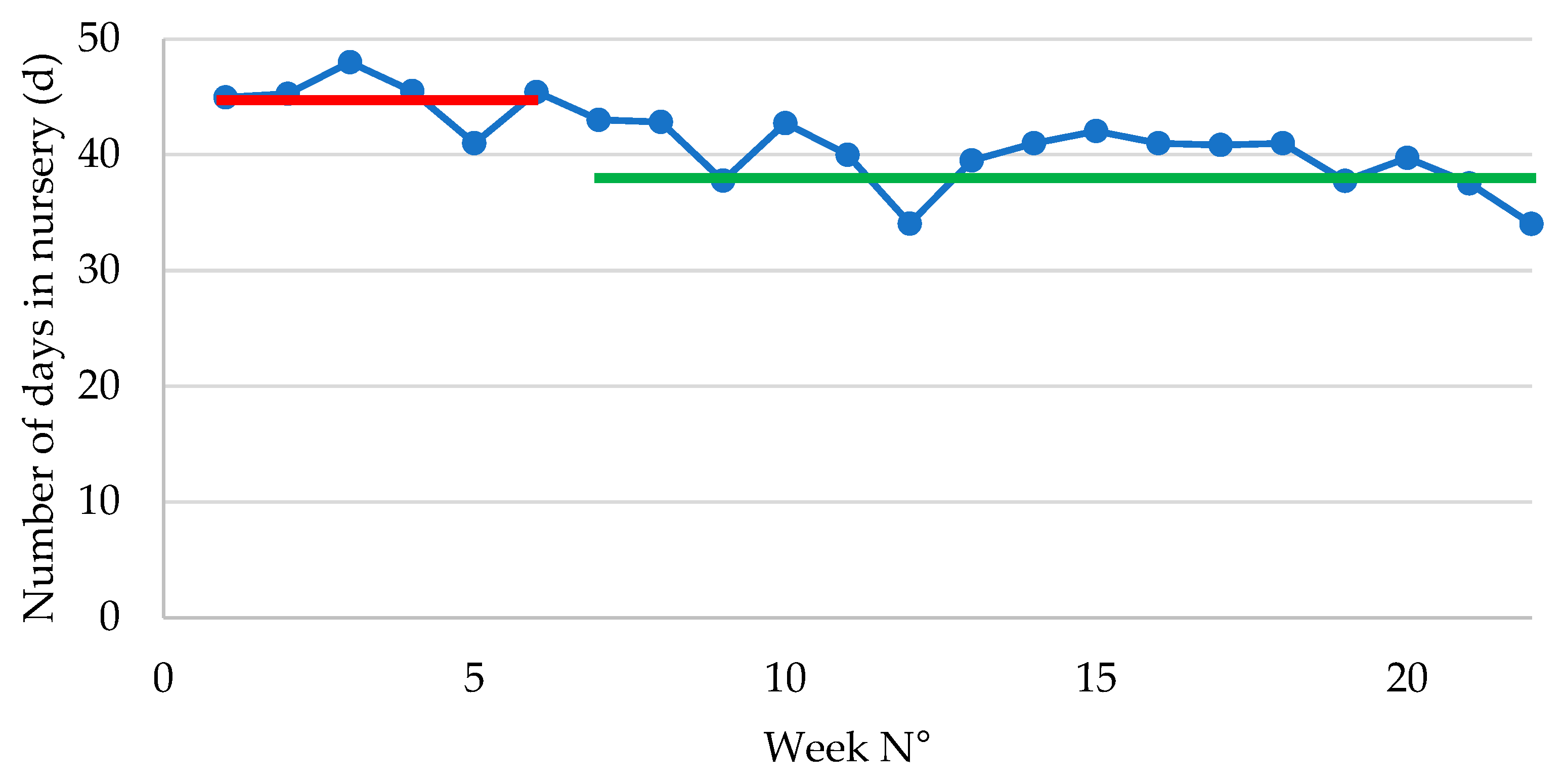

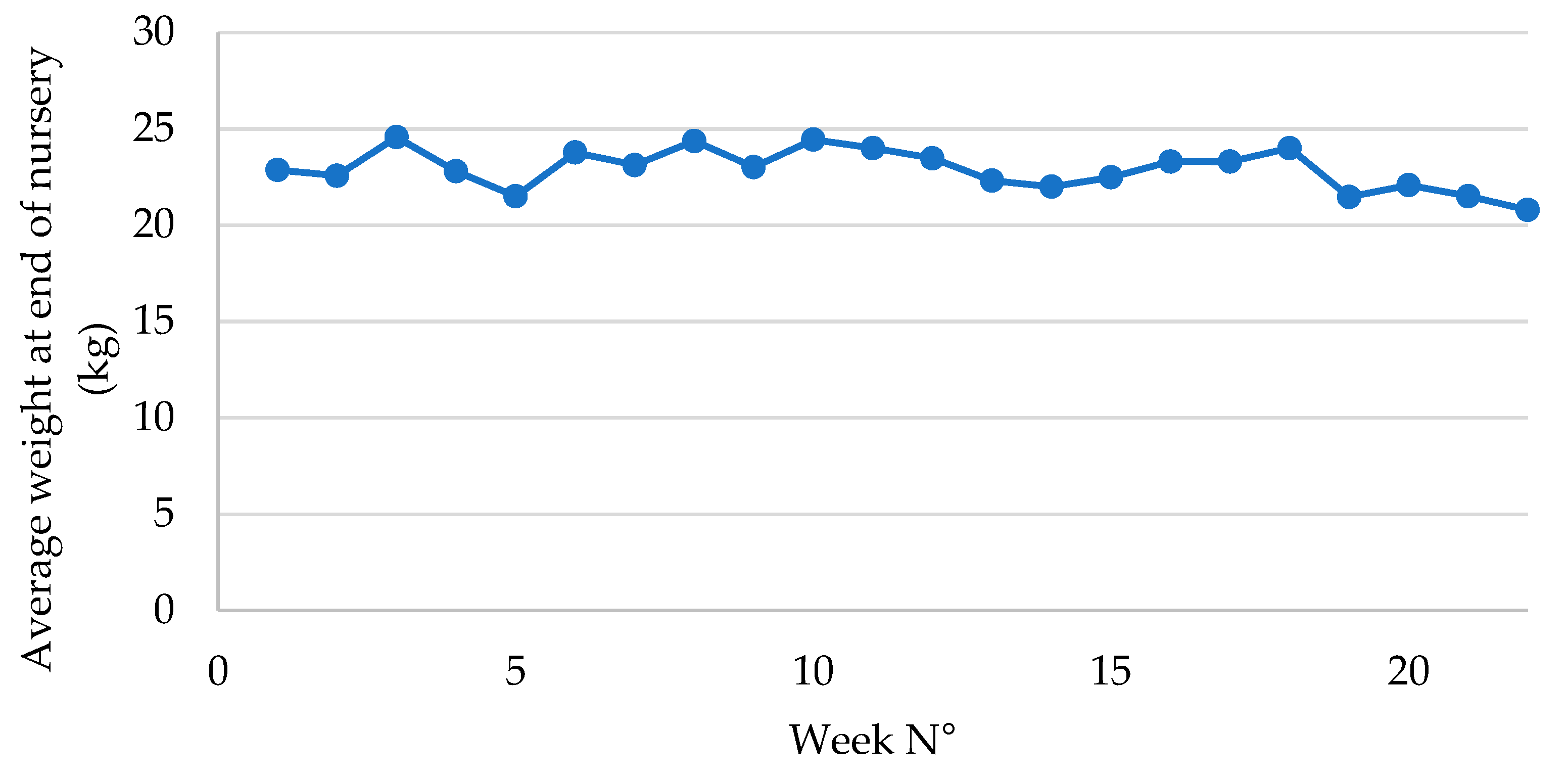

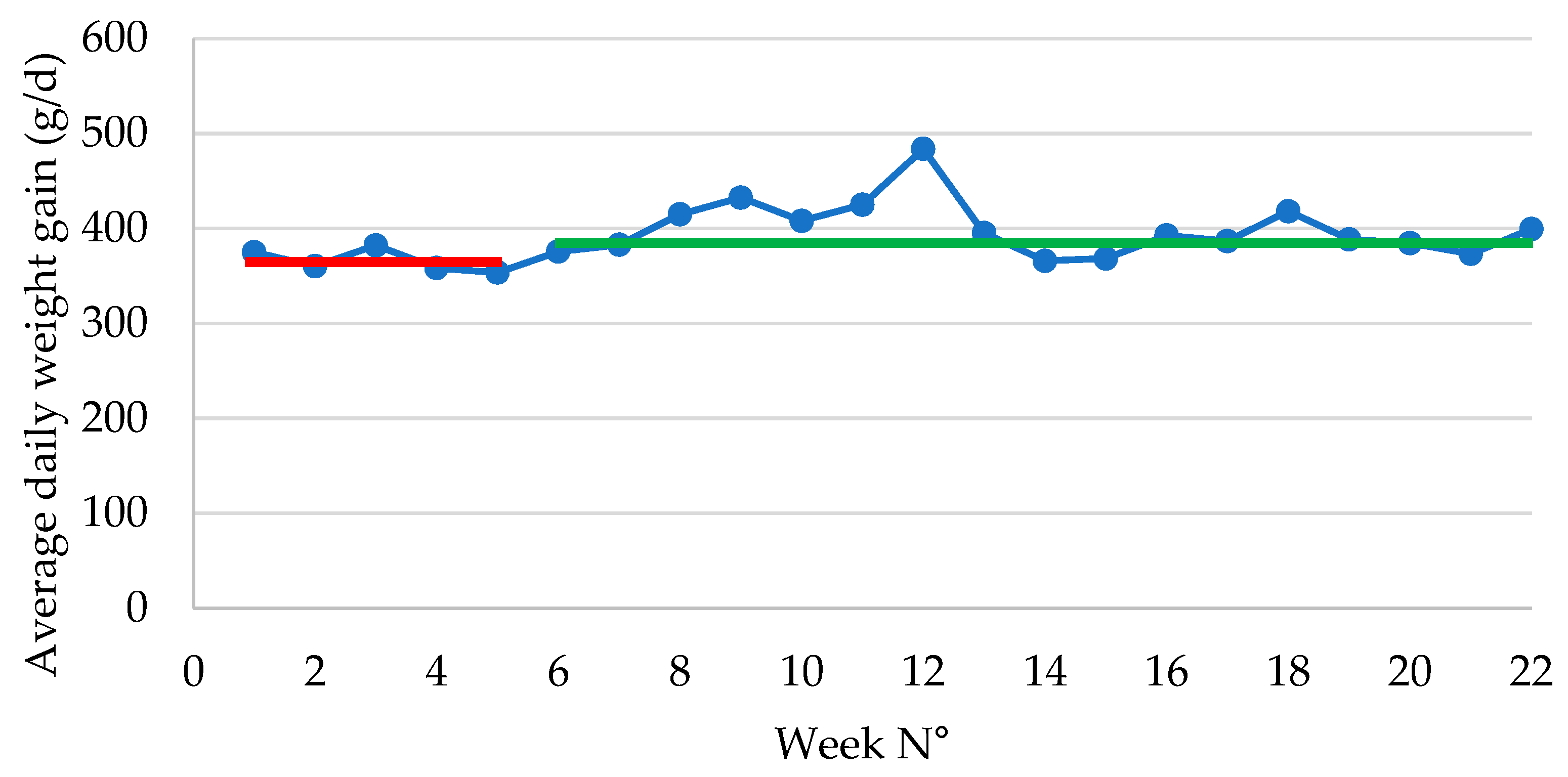

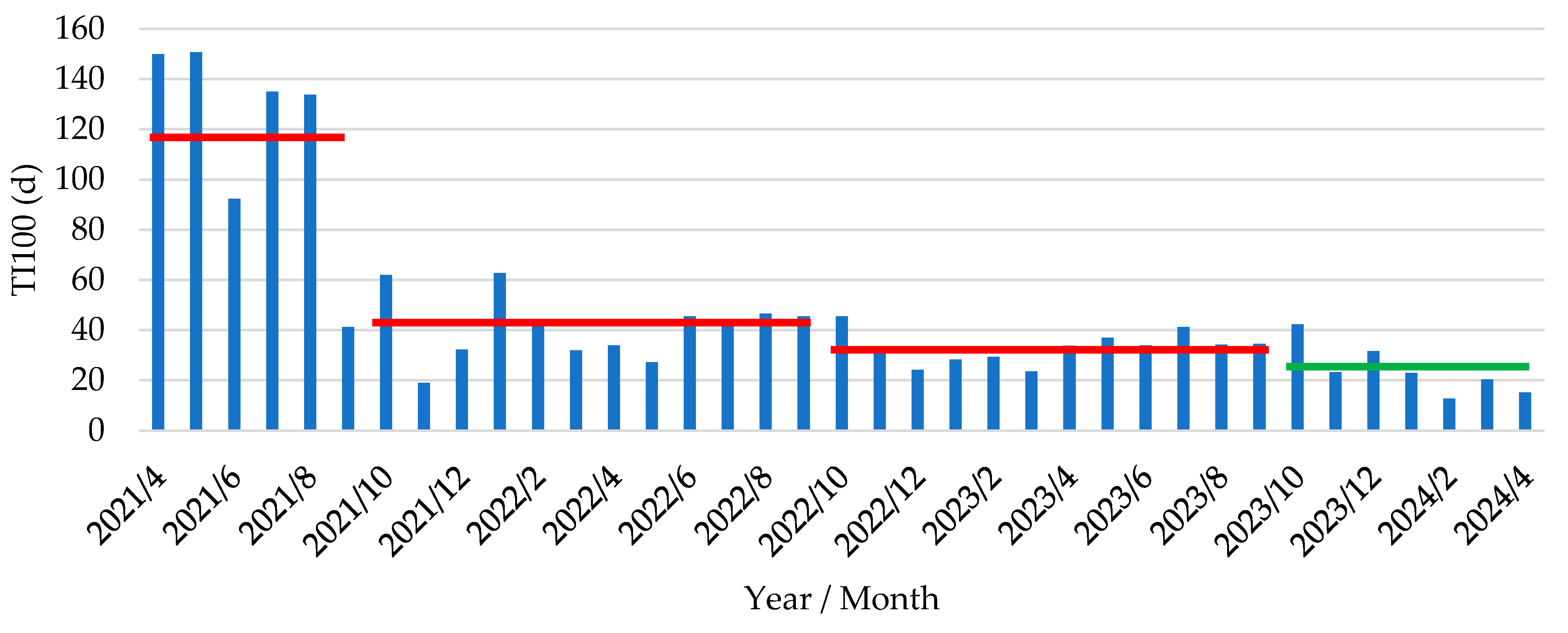

The current study on vaccination of piglets pre-weaning to protect against PWD due to F4-ETEC clearly demonstrates that overall technical performance was significantly improved following continued vaccination with an oral live avirulent E. coli vaccine for several months, combined with a marked reduction in antimicrobial use throughout the vaccination period. Several economically important and clinically relevant performance parameters, such as ADWG, number of days in nursery and TI100 were significantly improved between the first 6 weeks of vaccination (P1; 1-6 weeks) and the subsequent 16 weeks of vaccination (P2; 7-22 weeks).

Total weight gain in the nursery was approximately 890 g lower in P2 as compared to P1. Concurrently, the number of days in nursery reduced significantly from nearly 45 days in P1 to 38 days in P2, which implies that the piglets in P2 had a 7-day shorter stay within the post-weaning facilities. Therefore, the ADWG was significantly improved with 26 g/d from 266 g/d in P1 to 392 g/d in P2. If piglets remained the same number of days in nursery in both groups, the piglets in P2 would have an end of nursery weight of 24.67 kg, which would be much higher as compared to the end of nursery weight of 22.86 kg currently obtained in P1.

During P2, a lower number of piglets was weaned per week batch as compared to P1. Considering a similar number of productive sows in each consecutive week batch, this would indicate a lower number of piglets weaned per sow in P2 as compared to P1. This might explain the significantly higher weaning weight (+ 630 g per piglet) registered during P2 (7.03 kg) as compared to P1 (6.40 kg).

From the perspective of antimicrobial use, there was a trend for reduction of the TI100 between P1 and P2. There are several reasons for this gradual but ongoing decrease in TI100 over time. Following a farm visit, several general and specific biosecurity measures were proposed with an impact on antimicrobial use during the post-weaning period. Water management resulted in a better water quality at source level and improved waterline hygiene throughout the entire farm. Critical evaluation of the general hygiene protocols resulted in an improved cleaning and disinfection (C&D) protocol, following quantitative evaluation of the C&D results by Rodac plates. This improved C&D approach resulted in a reduction of the infection pressure throughout the farm facilities and more specifically within the post-weaning facilities. Besides the C&D protocol, needle management was upgraded, which resulted in less potential iatrogenic spread of disease pathogens through contaminated needles during treatment and vaccination procedures. The PWD-specific approach probably had the largest impact on the TI100 reduction, since adaptations in antimicrobial group treatment protocols were implemented in parallel to the vaccination. Standard antimicrobial treatment post-weaning was almost totally abolished both through the waterline and through feed premixes. When the clinical need for treatment was present at pen level, the piglets in the specific pen were treated with a limited amount of antimicrobials using a water bowl instead of the previous protocol with an immediate intervention through an overall group treatment.

When analyzing the TI100 evolution over a longer period of 36 month prior to the start of the vaccination, an important reduction from 117.2 days (2021) to 33.2 days (2023) had already been obtained. However, under the current new AMCRA antimicrobial rules, the TI100 during the post-weaning period should not exceed 30 from January 1st, 2025 onwards. Therefore, we can conclude that with all efforts made during the previous period, the farm that was originally categorized as an ‘attention farm’ at the end of 2023 was able to reduce its antimicrobial use to an acceptable level according to AMCRA regulations.

In the current study, we compared piglets vaccinated with Coliprotec F4F18 during 2 consecutive periods, namely the first 6 weeks (P1) and the subsequent 16 weeks (P2), mainly due to the lack of reliable historical data on post-weaning performance in this farm. However, as we have experienced in the past, vaccination with Coliprotec F4F18 needs a few weeks (approx. 6 weeks) to reach a stable on-farm performance result. It was therefore logical to compare the results from these ‘artificially’ defined periods to observe the improvements in pig performance and antimicrobial use. If we might have got reliable historical data, the difference between non-vaccinated piglets and vaccinated piglets would probably have been more pronounced. Another option could have been to run a concurrent control and treatment/vaccination group. However, due to several practical constraints related to housing during the post-weaning period, it would have been quite difficult to run this kind of trial set-up under the current field conditions. Moreover, piglets should be vaccinated prior to weaning, due to the 7-day onset of immunity to the oral live avirulent E. coli vaccine, and piglets of different litters were commingled according to weight, quality and general condition at weaning. Changes in these day-to-day routine management practices would complicate the set-up and performance of this practical field experience and might lead to unvoluntary and non-detectable errors that might have blurred the results and conclusions. Using the current study design allowed us to only change one specific parameter – i.e. vaccination of piglets prior to weaning – and evaluate the effect of this implemented vaccination strategy over time in relation to the overall adaptations in management practices based on the antimicrobial reduction coaching trajectory.

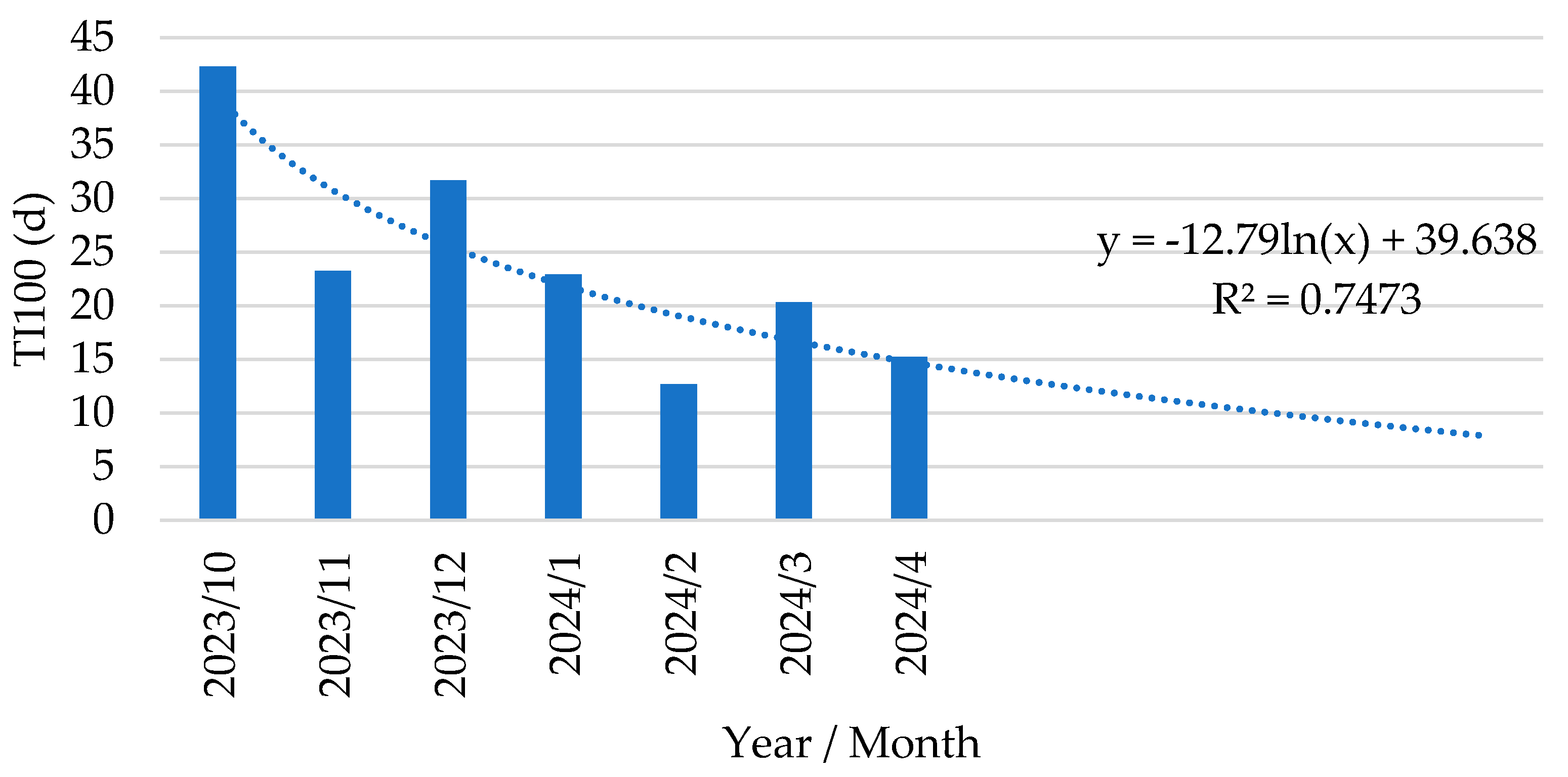

In Belgium, antimicrobial use at farm and animal category level (sows, piglets, fattening pigs) is collected in a central database (Ab register,

www.abregister.be) by the farm veterinarian on a quarterly basis. Based on these registrations and the individual delivery documents of the antimicrobial products, we could analyze the TI

100 and details of all administered products (oral products both through drinking water and feed premix, and injectables) for PWD at the farm. The current study demonstrated a drastic decrease in antimicrobial use following implementation of an oral live avirulent

E. coli vaccine in piglets to prevent the clinical signs of PWD due to F4-ETEC. Indeed, both the overall TI

100 and more detailed data per batch showed a marked decrease in antimicrobial use following vaccination. The average TI

100 in the 2 years prior to implementation of the

E. coli vaccine was 41.0 days (2022) and 33.2 days (2023) and further decreased to 24.1 days upon enrolment of

E. coli vaccination. Further detailed analysis during the period of

E. coli vaccination demonstrated a gradual decrease in TI

100 as illustrated in

Figure 6, where we calculated a trendline for the decrease in antimicrobial use:

y = -12.79 ln(x) + 39.64. The limited amount of antimicrobials that were occasionally used were directed towards

Streptococcus suis meningitis in the second part of the post-weaning period. In contrast to previous observations [

32], there was still an occasional episode of

S. suis-related meningitis in some weekly batches, although the clinical presence of diarrhea due to PWD was very limited to entirely absent depending on the batch.

Mortality data were recorded in detail, keeping track of the number of dead piglets in each weekly production batch (

Table 1). During P1, an average of 52 piglets died per weekly batch, resulting in a 5.7% mortality. Following stabilization of the

E. coli PWD vaccination effect, the average number of dead piglets dropped to 16 per weekly batch, resulting in a 2.0% mortality. Moreover, the fluctuation in mortality percentage that occurred during the first few weeks stabilized over the next months (

Figure 3). The significant reduction in both the number of dead piglets (

P = 0.001) and the mortality percentage (

P = 0.004) between P1 and P2 represented an important economic value as will be apparent in the ROI calculation table (

Table 4). Since the weight of dead piglets was not available, we have no specific information on the period and reason of death of the piglets during the post-weaning period. In contrast to previous

E. coli vaccination studies, we could not conclude that in this case the problem of

S. suis meningitis in the second part of the post-weaning period disappeared. Although the treatment with amoxicillin could be reduced, there was no complete resolution of the

S. suis infection pressure as previously observed in other studies.

Based on the published economic ROI calculator by [

32], we calculated an ROI of + € 2.72 per vaccinated piglets, already considering the cost of

E. coli vaccination (

Table 4). For this calculation, we used the collected and calculated performance parameters during P1 – first 6 weeks following

E. coli vaccination – and P2 – following 16 weeks of

E. coli vaccination. For this specific 1000-sow farm, an extra income of € 89.746 could be generated based on improved mortality, increased ADWG, and reduced antimicrobial use.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Description of the Sow Farm

A 1000-sow farm with PIC sows operating in a 1-week BMS was rated as an ‘attention farm’ at the level of the post-weaning period according to the AntiMicrobial Consumption and Resistance in Animals (AMCRA; Brussels, Belgium) benchmark reporting tool. To analyze the specific approach towards antimicrobial use and the related post-weaning pathology, a farm visit including a biosecurity check was carried out together with all associated stakeholders.

Subsequently, an antimicrobial coaching trajectory was enrolled to follow-up on the improvement of the reduction of antimicrobial use after implementation of the various advice.

4.2. Antimicrobial Coaching Trajectory

The enrolment of the antimicrobial coaching trajectory contained both a thorough analysis of antimicrobial data sheets including an interview with all stakeholders at farm level (farm owner, farm veterinarian, and employees in different sections of the farm), and a farm visit through all section of the farm (gilt rearing, gestation, farrowing, post-weaning facilities) to get a broad idea on the general and specific farm management related to disease control and prevention and the use of antimicrobial products.

Based on the generated information, an action plan was designed with practical advice towards improvement of general biosecurity, water management, general hygiene measures, including C&D, and specific measures related to PWD. An overview of this advice is given in

Table 3.

4.3. Post-Weaning Diarrhea Diagnosis

The farm suffered for several years from PWD outbreaks due to ETEC in every consecutive weekly batch. This resulted in consistently high antimicrobial use during the post-weaning period related to PWD due to ETEC and subsequent meningitis due to Streptococcus suis. Therefore, untreated piglets (n = 5) with typical clinical signs of PWD, such as watery diarrhea, thin belly and signs of dehydration, were sampled using rectal swabs (Sterile Transport Swab Amies with Charcoal medium; Copan Italia S.p.A., Brescia, Italy). All sampled piglets were post-weaning for 3 to 5 days post-weaning. The diagnostic samples were sent to the laboratory (IZSLER, Brescia, Italy) under cooled conditions for further processing.

Specimen were processed using the standard procedures for isolation and characterization of intestinal

E. coli [

5,

14]. Briefly, samples were plated on selective media and on tryptose agar medium supplemented with 5% defibrinated ovine blood and incubated aerobically overnight at 37°C. Hemolytic activity was evaluated, and single coliform colonies were further characterized.

DNA samples were prepared from one up to five hemolytic and/or non-hemolytic

E. coli colonies and used to perform a multiplex PCR for the detection of fimbrial and toxin genes, including those encoding for F4 (K88), F5 (K99), F6 (987P), F18, F41, LT, STa, STb and Stx2e, but not discriminating between F4ab, F4ac and F4ad. The methodology used for the identification of these virulence genes has been described previously [

14]. All collected samples were positive for F4 in combination with STa, STb, and LT. No other virulence factors could be detected (

Table 4).

Table 4.

Diagnostic laboratory results on isolation, identification and antimicrobial resistance profile of the Escherichia coli strain involved in post-weaning diarrhea and the secondary clinical problem of acute mortality due to Streptococcus suis meningitis. Grey colored blocks indicate absence of relevant information.

Table 4.

Diagnostic laboratory results on isolation, identification and antimicrobial resistance profile of the Escherichia coli strain involved in post-weaning diarrhea and the secondary clinical problem of acute mortality due to Streptococcus suis meningitis. Grey colored blocks indicate absence of relevant information.

| Pathogen |

|

Escherichia coli |

| Culture morphology |

Hemolytic |

| Adhesins / fimbriae |

|

| |

F4 (K88) |

Positive |

| |

F18 |

Negative |

| Toxins |

|

| |

STa |

Positive |

| |

STb |

Positive |

| |

LT |

Positive |

| |

Stx2e |

Negative |

| Pathotype |

F4-ETEC |

| Virotype |

|

F4 STa STb LT |

4.4. Vaccination Protocol

Following identification and specific pathotyping of the strain involved in PWD, a practical vaccination protocol was designed to protect piglets from F4-ETEC during the period ‘at risk’ post-weaning. Therefore, an oral live avirulent E. coli F4/F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IA, USA) was diluted into cold water including 25 g of electrolytes and 0.5 g of stabilizer (AviBlue; Elanco Animal Health) per litre of water volume.

The volume of water was determined through a volume consumption essay prior to the vaccination day. The outcome of this essay was a volume of 1.75 L per litter. In this volume, a total of 12.5 doses of live avirulent E. coli vaccine was diluted. From a practical point of view, a vial of 50 doses was diluted into 7 L of water with electrolytes and stabilizer. The vaccine should be consumed by the piglets in the litter within 4 h after distribution.

4.5. Piglet Performance Data Capture

The following data were captured from the weaned piglets: weaning weight, number of weaned piglets per batch, duration in the post-weaning facility, weight at the end of the post-weaning phase, mortality and antimicrobial use during the post-weaning period. Based on these data, the mortality percentage and treatment incidence over 100 days in nursery (TI100) were calculated.

For analytical purposes, the results in the first 6 weeks post-vaccination (period 1, P1; vaccine stabilization period) were compared to the results in the following 16 weeks (period 2, P2; stable vaccine period).

4.6. Economic Return-on-Investment Calculation

An economic return-on-investment calculation was performed based on [

32] Vangroenweghe (2021). Therefore, the average data from the first 6 weeks of vaccination (P1; week 1-6) were compared to the following 16 weeks of vaccination (P2; week 7-22) considering performance data, treatment and vaccination cost, opportunity cost related to mortality and number of sows on the farm.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Calculations, exploratory data analysis and quality review, and subsequent statistical analysis were all performed in JMP 16.0. All data were presented as means with their respective standard error of the mean (SEM). All means were tested for significant differences (P < 0.05) using a T-test.

Figure 1.

Number of days in the post-weaning phase in piglets following vaccination with an oral live avirulent Escherichia coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 6 days pre-weaning. Red line indicates the average number of days in nursery (44.95 d) during P1 (1-6 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination. The green line indicates the average number of days in nursery (38.01 d) during P2 (7-22 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination.

Figure 1.

Number of days in the post-weaning phase in piglets following vaccination with an oral live avirulent Escherichia coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 6 days pre-weaning. Red line indicates the average number of days in nursery (44.95 d) during P1 (1-6 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination. The green line indicates the average number of days in nursery (38.01 d) during P2 (7-22 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination.

Figure 2.

Average weight at end of post-weaning phase in piglets following vaccination with an oral live avirulent Escherichia coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 6 days pre-weaning. Red line indicates the average weight at the end of nursery (22.86 kg) during P1 (1-6 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination. The green line indicates the average weight at the end of nursery (21.97 kg) during P2 (7-22 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination.

Figure 2.

Average weight at end of post-weaning phase in piglets following vaccination with an oral live avirulent Escherichia coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 6 days pre-weaning. Red line indicates the average weight at the end of nursery (22.86 kg) during P1 (1-6 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination. The green line indicates the average weight at the end of nursery (21.97 kg) during P2 (7-22 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination.

Figure 3.

Average daily weight gain (expressed as g/d) in piglets during the post-weaning period following vaccination with an oral live avirulent Escherichia coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 6 days pre-weaning. Red line indicates the average daily weight gain (362 g/d) during P1 (1-6 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination. The green line indicates the average daily weight gain (392 g/d) during P2 (7-22 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination.

Figure 3.

Average daily weight gain (expressed as g/d) in piglets during the post-weaning period following vaccination with an oral live avirulent Escherichia coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 6 days pre-weaning. Red line indicates the average daily weight gain (362 g/d) during P1 (1-6 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination. The green line indicates the average daily weight gain (392 g/d) during P2 (7-22 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination.

Figure 4.

Percentage post-weaning mortality (expressed as %) in piglets during the post-weaning period following vaccination with an oral live avirulent Escherichia coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 6 days pre-weaning. Red line indicates the average mortality percentage (5.7%) during P1 (1-6 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination. The green line indicates the average mortality percentage (2.0%) during P2 (7-22 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination.

Figure 4.

Percentage post-weaning mortality (expressed as %) in piglets during the post-weaning period following vaccination with an oral live avirulent Escherichia coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 6 days pre-weaning. Red line indicates the average mortality percentage (5.7%) during P1 (1-6 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination. The green line indicates the average mortality percentage (2.0%) during P2 (7-22 weeks) of the E. coli vaccination.

Figure 5.

Treatment incidence over 100 days in post-weaning phase (TI100, expressed as d) in piglets following vaccination with an oral live avirulent Escherichia coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 6 days pre-weaning. Vaccinated piglets were housed in the post-weaning facilities from October 2023 onwards. Red lines indicate the average TI100 over the last 30 months prior to the start of the E. coli vaccination (2021/4 – 2021/9, 117.2 ± 17.5 d; 2021/10 – 2022/9, 41.0 ± 3.8 d; 2022/10 – 2023/9, 33.2 ± 1.8 d). The green line indicates the average TI100 (24.1 ± 3.8 d) from the time point of E. coli vaccination onwards.

Figure 5.

Treatment incidence over 100 days in post-weaning phase (TI100, expressed as d) in piglets following vaccination with an oral live avirulent Escherichia coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 6 days pre-weaning. Vaccinated piglets were housed in the post-weaning facilities from October 2023 onwards. Red lines indicate the average TI100 over the last 30 months prior to the start of the E. coli vaccination (2021/4 – 2021/9, 117.2 ± 17.5 d; 2021/10 – 2022/9, 41.0 ± 3.8 d; 2022/10 – 2023/9, 33.2 ± 1.8 d). The green line indicates the average TI100 (24.1 ± 3.8 d) from the time point of E. coli vaccination onwards.

Figure 6.

Trendline analysis of treatment incidence over 100 days in post-weaning phase (TI100, expressed as d) in piglets following vaccination with an oral live avirulent Escherichia coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 6 days pre-weaning.

Figure 6.

Trendline analysis of treatment incidence over 100 days in post-weaning phase (TI100, expressed as d) in piglets following vaccination with an oral live avirulent Escherichia coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 6 days pre-weaning.

Table 1.

Comparative table of performance results from period 1 (1-6 weeks) and period 2 (7-23 weeks) of vaccination with a live avirulent E. coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco AH).

Table 1.

Comparative table of performance results from period 1 (1-6 weeks) and period 2 (7-23 weeks) of vaccination with a live avirulent E. coli F4F18 vaccine (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco AH).

| |

Period 1 |

Period 2 |

P-value |

| Weeks of vaccination |

1-6 |

7-23 |

- |

| Average weaning weight (kg) |

6.40 ± 0.17 |

7.03 ± 0.07 |

0.001 |

| Aantal gespeende biggen per batch |

851 ± 79 |

752 ± 29 |

0.069 |

| Sterfte (#) |

52 ± 11 |

16 ± 3 |

0.0001 |

| Sterfte (%) |

5.7 ± 0.01 |

2.0 ± 0.00 |

0.0004 |

| Average weight at end of nursery (kg) |

22.86 ± 0.49 |

21.97 ± 0.26 |

0.467 |

| Average days in nursery (d) |

44.95 ± 1.13 |

38.01 ± 0.74 |

0.002 |

| Average daily weight gain |

366 ± 5 |

392 ± 7 |

0.011 |

| BD100 (d) |

32.8 ± 9.6 |

20.6 ± 3 |

0.082 |

| ROI per piglet |

|

+ 2.72 |

- |

Table 2.

Return-on-investment calculation based on the production results prior to the start of the E. coli vaccination (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN, USA) in a 1,000 sow farms with a profile of high antimicrobial use provoked by post-weaning diarrhea due Escherichia coli F4 and subsequent meningitis due to Streptococcus suis.

Table 2.

Return-on-investment calculation based on the production results prior to the start of the E. coli vaccination (Coliprotec F4F18; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN, USA) in a 1,000 sow farms with a profile of high antimicrobial use provoked by post-weaning diarrhea due Escherichia coli F4 and subsequent meningitis due to Streptococcus suis.

| Coliprotec F4F18 – ROI calculator |

|

|

| |

|

|

| Input variables |

Control |

Coliprotec F4F18 |

| Weaning weight (kg) |

6.20 |

7.03 |

| Piglet price (25 kg) (€/big) |

56.00 € |

56.00 € |

| Duration of post-weaning phase (days) |

46.10 |

38.01 |

| Average daily weight gain (gram/day) |

355.00 |

392.70 |

| Feed conversion rate (kg feed/kg growth) |

1.73 |

1.73 |

| Feed cost post-weaning phase (€/tonne) |

324.00 € |

324.00 € |

| Percentage piglet mortality (%) |

5.70 |

2.00 |

| Treatment cost (€/day/piglet) |

0.05 € |

0.05 € |

| Treatment incidence (# days/100 days in production) |

53.10 |

24.10 |

| Coliprotec F4F18 vaccine cost (€/dose) |

1.00 € |

1.00 € |

| Number of sows at the farm |

1000.00 |

1000.00 |

| Piglets weaned per sow per year |

33.00 |

33.00 |

| Return-on-investment calculation |

Control |

Coliprotec F4F18 |

| Weight at end of post-weaning phase (kg) |

22.57 |

21.96 |

| Total feed intake (kg) |

28.31 |

25.82 |

| Total feed cost (€/piglet) |

9.17 € |

8.37 € |

| Treatment cost antimicrobials (€/piglet) |

2.66 € |

1.21 € |

| Supplement extra weight piglet (+25 kg) (€/piglet) |

-2.43 € |

-3.04 € |

| Opportunity cost of mortality (€/piglet) |

3.19 € |

1.12 € |

| Vaccination cost (€/piglet) |

0.00 € |

1.00 € |

| Gain per piglets (€/piglet) |

43.55 € |

46.26 € |

| Extra gain per piglet with Coliprotec F4F18 (€/piglet) |

|

2.72 € |

| Return-on-investment |

|

2.72 |

| Impact Coliprotec F4F18 at farm level per year |

|

|

| Total number of weaned piglets |

|

33,000 |

| Cost of vaccination with Coliprotec F4F18 (€) |

|

€ 33,000.00 |

| Extra farm income per year (€) |

|

€ 89,746.80 |

| Extra income per piglet weaned (€) |

|

€ 2.72 |

Table 3.

Overview of general and specific biosecurity measures proposed within the scope of the antimicrobial coaching trajectory to reduce the use of antimicrobials on a farm with a problematic user profile according to the AMCRA evaluation tool.

Table 3.

Overview of general and specific biosecurity measures proposed within the scope of the antimicrobial coaching trajectory to reduce the use of antimicrobials on a farm with a problematic user profile according to the AMCRA evaluation tool.

| Type of measure |

Measure description |

| General biosecurity |

Regular cleaning and disinfection of carcass rendering location |

| |

Cleaning and disinfection of carcass recipient after use and prior to new re-use for the next batch. Use a disinfectant with a strong virucidal spectrum. |

| |

Footwear management around carcass rendering location@@@@Separate boots@@@@Alternatively: use plastic overshoes@@@@ |

| |

|

| Water management |

Permanently disinfect surface water source with a dosing pump on the waterline |

| |

Prevent Clostridia growth through continuous aeration of the open-air water source combined with a peroxide disinfection in the waterline |

| |

|

| General hygiene measures |

Objective quantitative evaluation of cleaning and disinfection procedure through Rodac plates |

| |

Needle management upon injectable treatment: regular needle renewal@@@@Piglets: renewal after every litter@@@@Weaned piglets: renewal at start of new product vial@@@@Gilts: renewal at start of new vaccine product vial |

| |

|

| Specific PWD-approach |

Postpone start of group treatment until 2 d after weaning |

| |

Stop standard use of tilmicosin premix p.o. through feed |

| |

Stop systematic treatment with antimicrobial premix p.o. for extended periods |

| |

In case of clinical problems: start treatment p.o. through drinking water for a short period |