My dear girl, you are so beautiful

with your raised breasts.

Kŗşņa (1987): The Source of Happiness

The verdict is still out on why

the permanent breast evolved in humans.

Deena Emera (2023): A Brief History of the Female Body

1. Introduction

For a population of a given species, according to Darwin, the value of its effective reproduction rate, r, is the criterion for the species’ survival (Fisher 1930; Volterra 1931; Eigen 1971; Wilson and Bossert 1973). “Evolution’s success is measured by the number of offspring produced to propagate the gene” (Strakosch 2016: p. 7). This criterion applies rigorously also to the many generations of hominins in the course of the past 7 million years (Myr) of evolution. Evidently, if this rate is negative, , the population will become extinct, if it is positive, , the population will grow exponentially. For an ecologically stable population, the value should rather fluctuate about zero.

The fundamental transition from arm-swinging (brachiating) apes to bipedal humans was accompanied by a series of changes in hominin reproductive behaviour which have eventually resulted in the various distinctive traits observed in contemporary humans (Muller 2017a). In this paper, among those traits, childhood is considered the key phenomenon that is fundamental to human ontogenesis but is not found in chimpanzees. Childhood, the developmental phase of helpless mammal infants beyond breastfeeding, emerged naturally from bipedal gait due to early weaning, but posed a significant lethal risk to the offspring if the mother got pregnant too early again. Effects of female genetic contraceptives in conjunction with related sexual activities of males became crucial for protecting the infants and to ensure survival by adequate net reproduction rates.

In hominin evolution, some of the emerging reproductive traits may had been caused by other, preceding changes. In a simple hominin model population, such putative causal chains are investigated here theoretically and hypothetically, starting from a last common ancestor (LCA) similar to recent chimpanzees. Assumingly living in stable populations, the latter ones had effective reproduction rates close to zero, so that severe alterations of their way of living may had produced small variations of the value of r, with possibly dramatic long-term consequences for the survival of the population, in either direction.

When the knuckle-walking LCA species was gradually adapting to upright gait, offspring could no longer ride on the back of their mothers and enjoy breastfeeding, as they did before during all their years of helpless infancy. The new bipedal way of life kicked off a series of grave consequences and essential, inevitable changes in the reproductive behaviour. Requisite for survival, the resulting alternating and mutually counter-acting methods, introduced successively by the two sexes in this model, will be described in detail in the following

Section 3,

Section 4,

Section 5,

Section 6,

Section 7,

Section 8,

Section 9 and

Section 10. In brief, those measures and their particular consequences are summarised here in advance:

- (i)

Upright gait prevents offspring from riding on their mothers’ back. Early weaning and the resulting untimely new pregnancy pose severe hazards to infants and reduce the reproduction rate to a subcritical level.

- (ii)

Females concealing their oestrus swelling and avoiding copulation during childhood may feed and protect their helpless infants during childhood. In the short run, this recovers sufficient reproduction, but in the long run, too few females will mate to get inseminated in order to ensure necessary birth rates.

- (iii)

Reproduction rates can be recovered by males who learn to copulate with unswollen females, whether or not their state of fertility is openly demonstrated. As a new sexual attractor, ovulation swelling is replaced by an objectified female body, and accordingly, previous occasional, tightly focussed copulation is replaced by enduring random mating attempts of sex-addicted males.

- (iv)

Because weaning restarts ovulation, possibly followed by menstruation, males can increase their mating success by inspecting the female vulva in advance, to avoid futile copulation with noticeably unfertile females. In the long run, however, this male method leads back to early pregnancy, hazardous for infants and lowering the reproduction rate again.

- (v)

Females respond to permanent male copulation attempts with sexual reluctance (frigidity) and active refusal of mating. This alternative contraception method helps to protect infants against early pregnancy, but, in the long run, again implies the risk of subcritical birth numbers.

- (vi)

Reproduction rates are recovered by males who coercively and frequently enforce mating. However, in the long run, this behaviour puts infants back to previous hazards.

- (vii)

As another new contraceptive, females develop demonstrative adipose breasts which after weaning pretend continued lactation and infertility in order to prophylactically distract males from coercive approaches. This short-time solution of the problem also includes again the long-term risk of returning to subcritical birth rates.

- (viii)

Reproduction rates are recovered by males who investigate breasts and nipples for milk excretion, to reveal the lactation fake and to copulate preferably with milk-free, fertile females. Females recognise frequent such investigations as an invitation to mating or as a menace of rape, and may in advance respond accordingly by actively deciding about accepting or refusing sex.

- (ix)

Females who after weaning are successful in avoiding pregnancy during offspring childhood, experience regular menstruation cycles with related enhanced depletion of the ovarian reserve. As a consequence, menopause occurs earlier and possibly already within the female’s lifespan. Despite their infertility, old females remain beautiful in the eyes of males, but may, regardless of frequent copulations, take care of helpless grand-infants as soon as their mothers become untimely pregnant. This division of labour with maternal grandmothers can successfully shorten interbirth intervals and this way lift the reproduction rate above critical values.

- (x)

Males, in addition, increase mating success by avoiding sex with old females, recognising that those may often be post-menopausal. To achieve this, the former male objectification of old females (their genetically specified “standard of beauty”) is replaced by a new mental sieve implementing the sexually attractive beauty of young mature females.

- (xi)

Short interbirth gaps of young mothers, supported by their menopausal grandmothers during offspring childhood, provide substantial selective advantage and support rapid population growth and dispersion. This extreme success in solving the former long-lasting sexual conflict, originally caused by bipedalism, is due to patriarchal coercive mating which overcomes possible female frigid reluctance or resistance.

- (xii)

Male investigations of vulva and breasts, although no longer pertinent, remain as introductory parts of the regular mating behaviour. In a ritualisation transition, this use-activity of checking female fertility is converted into a symbolic signal-activity of a courtship habit. Adipose breasts, while having lost their relevance as a contraceptive, may regionally persist after human global dispersal as an inherited symbol invoking male sexual attention and physical arousal in both sexes.

The conceptual model of this paper undertakes an attempt to arrange those putative events in hominin reproductive evolution in appropriate relative sequence, thereby allowing for the heuristic principles of plausibility and continuity (Lehninger 1972; Romanovsky et al. 1975). In the course of millions of years, various behavioural innovations in hominin reproductive traits should have implemented observable inherited traces in the sex life of modern humans (Muller 2017a; Muller and Pilbeam 2017). “In our intelligent species, any activity which seems to be universal across time and cultures would appear to have a genetic basis” (Strakosch 2016: p. 1). Insofar, it is very likely that the presumed sexual transformations have really occurred along the succession of our pedigree ancestors. Unfortunately, there is little archaeological evidence available for detecting when, where or in which hominin branches those changes may actually had happened.

On the other hand, there apparently exist logical, causal and therefore also temporal mutual relations between the different stages of evolution; their sequence may not be arranged merely randomly. For example, as a contraceptive after weaning, female adipose breasts (vii) would have been futile as long as males show occasional sexual interest exclusively in swollen females. Full dry breasts (vii) likely appeared only after females had concealed their oestrus (ii) and subsequently, after males had objectified the female body (iii) as a sexual target.

“So why are women’s breasts so fatty? Why are they shaped the way they are? Many people erroneously assume they evolved in this fashion because male Homo sapiens were more likely to mate with females who had fatty breasts. … Somewhere between our split from chimpanzees (anywhere between five and seven million years ago) and now, the hominin body plan added a bunch of adipose tissue to the female chest walls. We have no idea when, within that two-million-year time span, this happened. … The breast, like all soft tissue, doesn’t survive in the fossil record” (Bohannon 2023: p. 55, 56).

“The possession of permanent, adipose breasts in women is a uniquely human trait that … remains an unresolved conundrum” (Pawłowski and Żelaźniewicz 2021). Several common hypotheses are based on the assumption that male sexual and/or reproductive interest was the main driving force for the development of persistently protruding female breasts. The emergence of the previously unrivalled human female breast as a sex symbol has often been understood as a result of capricious male sexual interests “according to their standard of beauty” (Darwin 1911: Ch. IV) so that “the existence of permanent breasts in women is likely an aesthetic trait that has evolved by male choice” (Prum 2017: p. 256). By contrast to such approaches, however, the proposal made in this paper assumes that those breasts emerged for practical reasons first, and only subsequently the mere existence of those invited men to recognise female breasts as attractive sexual symbols.

Ritualisation is a behavioural transformation process of a use activity into a signal activity (Huxley 1914; Lorenz 1983; Tembrock 1977; Feistel 2023a). The ritualisation scenario suggested here assumes that the sexual function of the symbolic breast had naturally evolved from the individual female function of breastfeeding.

The broken sexual symmetry between males and females has resulted in different challenges for their maximum reproductive successes; while males are urged to inseminate as many female eggs as possible, mammal females after insemination need to raise their offspring safely to maturity. In the case of the LCA model, these unequal tasks take seconds for males but years for females. In the beginning, the transition to bipedal locomotion introduced no serious problem to males but severe implications to the inherited female reproduction behaviour. The resulting female response, in turn, rendered deficient the original sexual strategy of males and forced them to change it significantly. This ping-pong evolution went on until a sufficiently successful compromise - healthy childhood enabled by menopause - had emerged. However, the old inextricable sexual conflict stemming from bipedalism still lingers on in modern humans in various versions (Miller 2000; Greenblatt 2018; Eder 2018; Schipper 2020; van Schaik and Michel 2020; Stoverock 2021; Zimmermann 2023).

This paper is organised as follows. After the LCA model has been specified in some detail in

Section 2, the fatal impact of upright gait on mothers, namely, early weaning and getting pregnant anew, is described in

Section 3 as a substantial risk to nurtured infants, compelling females to gradually reduce their oestrous swelling. In

Section 4, in absence of the former female mating signal, males need to persistently copulate unsightly for siring offspring, adopting the objectified female body as the new mating signal. In response,

Section 5, females tend to repel mating advances by frigid behaviour as a contraceptive. In turn, sexually addicted males increasingly rely on coercive mating and rape except if females are discernibly immature, pregnant, breastfeeding or menstruating. To prevent male aggression in advance,

Section 6, females pretend continued lactation by developing adipose dry breast as a new contraceptive. Subsequently, males reveal this deception by closely inspecting breasts and nipples for possible milk discharge,

Section 7. While successful contraception protects infant childhood, it activates periodic ovulation followed by menstruation. In turn, accelerated depletion of the ovary shifts the menopause age down into the life span,

Section 8. Unfertile grandmothers assist in raising their yet helpless grandchildren. However, old unfertile females beyond menopause lose their sexual attractiveness, and younger mature females appear as more beautiful in the male’s eyes,

Section 9. Contraceptive effects of adipose breasts are eventually deprecated but the related male inspection activity persists as a ritualised courtship habit described in

Section 10. Each of these Sections suggests a certain “model stage” of evolution, followed by a “supporting context” that reviews and quotes some published aspects of that topic. In the final Discussion, present-day sexual conflicts are briefly mentioned in relation to the hominin evolution model.

This article is focussed exclusively on basic reproduction traits as primary elements behind the evolution of human sexual behaviour. However, many other, certainly closely related substantial differences between traits of humans and apes are beyond this paper’s scope and are intentionally ignored, such as the roles of tools and garments, of language and eye contact, of penis shape and loss of baculum, of brain size and width of the female birth canal, of limb asymmetry and endurance running, of meat consumption and use of fire, of music and dance, of childhood and learning, of consciousness and mental models, of arts and ornaments, or of social structures of cooperation and competition (Darwin 1879; Leakey and Lewin 1977; Klix 1980; Graham 1981; Reichholf 1990; Dixson 1998; Gopnik et al. 1999; Facchini 2006; Pika 2008; Gomes and Boesch 2009; McPherron et al. 2010; Andre et al. 2010; Fitch 2010; Harary 2011; Roberts 2011; Feistel and Ebeling 2011; Berna et al. 2012; Domínguez-Rodrigo et al. 2012; Lee-Thorp et al. 2012; Dunbar 2014; Ahnert 2014; Tomasello 2014; Maslin et al. 2015; Sussmann and Hart 2015; Wade 2016; Muller et al. 2017; Suhr 2018; Damasio 2018; Böhme et al. 2019; Bednarik 2022, 2023; Bohannon 2023; Feistel 2023a; Clark et al. 2024).

2. Initial State: Simple LCA Model of Chimpanzees and Humans

An axiomatic-like hominin model proposed here assumes that the last common ancestor (LCA) of humans and apes has simplified properties similar to those of recent chimpanzees. Let the reproductive traits of this LCA model be formally specified by:

- (i)

An LCA group consists of 40 individuals, 20 females and 20 males.

- (ii)

Group members possess limbs for tree climbing and do knuckle-walking on the ground.

- (iii)

The first anogenital swelling of females occurs at 10 years of age, at puberty.

- (iv)

Oestrus swellings vary in size and shape between individuals and with age.

- (v)

The menstrual cycle takes 40 days during 2 years of adolescent infertility.

- (vi)

Postnatal ovary contains 300 000 follicles to develop into egg cells during ovulation.

- (vii)

Each ovulation, fertilised or not, depletes 1000 follicles from the ovary reserve.

- (viii)

The duration of the oestrous swelling is 2 weeks, including the ovulation.

- (ix)

Oestrus timing is random, neither seasonally triggered nor mutually synchronised.

- (x)

First conception happens at 12 years of age, at maturity.

- (xi)

Gestation lasts 230 days.

- (xii)

The interbirth interval extends over 5 years of breastfeeding the infant.

- (xiii)

Oestrus is suppressed during lactation and resumes after weaning.

- (xiv)

A lifespan of 40 years is permitting 5 offspring to be born, no twins.

- (xv)

Of the 5 infants born per female, only 4 are raised to puberty, 2 of those being females.

- (xvi)

Females do not go into menopause.

- (xvii)

Individual males and females may freely pick their mating partners.

- (xviii)

Males preferably mate with older females.

- (xix)

Male sexual interest is strictly limited to swollen females.

- (xx)

Swollen females mate occasionally with all male group members.

- (xxi)

The copulation act between female and male takes just 7 seconds.

- (xxii)

Female swelling of mammary glands occurs only while breastfeeding.

- (xxiii)

Babies are clinging to their mother’s fur until 6 months of age.

- (xxiv)

Infants between 0.5 and 5 years of age are riding on their mother’s back.

- (xxv)

Mothers terminate carrying and breastfeeding their infants when those get 5 years old.

Female age intervals of LCA ontogenetic development are denoted here as

- (i)

babyhood - nursed up to LCA age 0.5

- (ii)

infancy – helpless and nursed between LCA age 0.5 and 5

- (iii)

childhood - infants already weaned but still nurtured

- (iv)

youth – autonomous feeding between childhood and puberty, LCA age 5 to 10

- (v)

adolescence - between puberty and maturity, female menstrual cycles, LCA age 10 to 12

- (vi)

adulthood - after maturity, repeated pregnancy and infant nurture, LCA age 12 to 40.

By LCA definition, offspring has no relevant childhood phase. “Childhood is probably a crucial innovation in human evolution” (Falk 2025).

After its birth, a baby is hanging in its mother’s fur and has access to the swollen mammary glands,

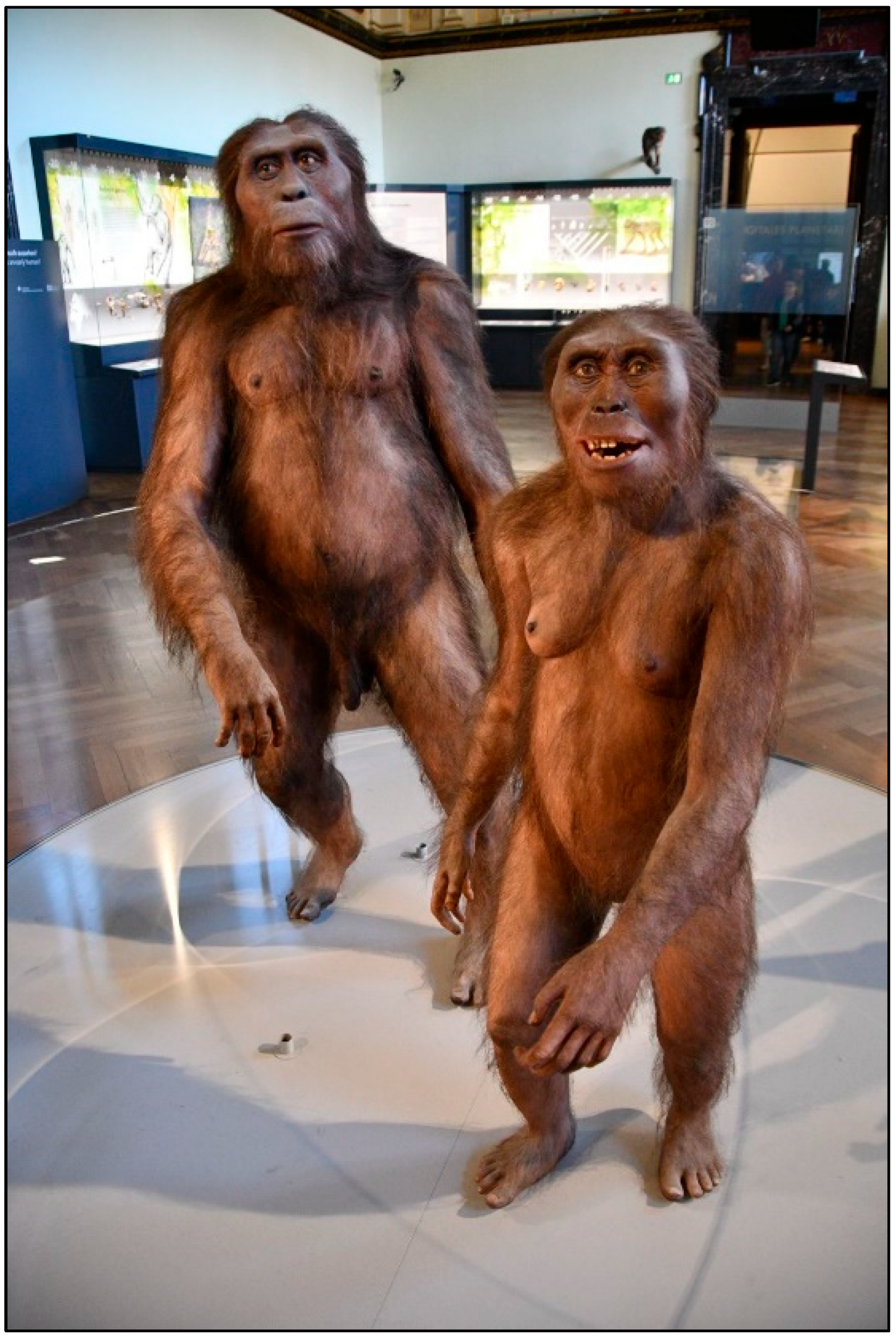

Figure 1. At an age of half a year, the mother is manually urging the child to ride on her back rather than clinging to her fur, but still permitting to drink her milk. Until its age of 5 years, the infant keeps close physical contact to its mother.

After weaning, lactation stops and the oestrus cycle restarts. During the swelling, to get pregnant again, the female attempts to mate with each male group member. This promiscuous behaviour reduces the risk that the newborn will be killed by a male group member who did not copulate with the mother. Menstruation does not occur if the insemination is successful. There may be male competition for mating during the female swelling phase, but not necessarily. Randomness of oestrus implies that there is less than 1 % chance that any two females have overlapping swellings within only two weeks of five years, so that there is no serious need for female competition with respect to male mating partners.

Statistically, if an LCA male is mating once with each swollen female group member, he may have sex 20 times in 5 years, or about once every 3 months, without sexual intentions in between. Having sex does not pose a dominating activity in this male’s life. In this model, sexual needs and inherited interests of males and females are mutually adapted and balanced in an optimum way to ensure reproduction, and they do not involve irresolvable general discrepancies between the sexes.

Chimpanzee fossils are rare (McBrearty and Jablonski 2005). While it appears unlikely that in the future the diverging evolution of chimpanzees and humans may become revealed in detail from fossil evidence, recent progress in genetics is a more promising but challenging information source (Bhowmick et al. 2007; Vegesna et al. 2020; Cechova et al. 2020; Makova et al. 2024; Yoo et al. 2025). “The great apes (orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos and humans) descended from a common ancestor around 13 million years ago, and since then their sex chromosomes have followed very different evolutionary paths. While great-ape X chromosomes are highly conserved, their Y chromosomes, reflecting the general lability and degeneration of this male-specific part of the genome since its early mammalian origin, have evolved rapidly both between and within species” (Hallast and Jobling 2017).

“Chimpanzees are important referential models for the study of life history in hominin evolution” (Walker et al. 2018: p.131). “A major goal is to see whether chimpanzee data can help us to reconstruct the evolution of unique human traits by constraining hypotheses for their evolution” (Muller 2017a: p. 179). The LCA of humans and chimpanzees likely lived about 7 million years ago (Pennisi 2012; Price 2017). “The earliest members of the hominid lineage probably had a mostly unpigmented or lightly pigmented integument covered with dark black hair, similar to that of the modern chimpanzee” (Jablonski and Chaplin 2000: p. 57). “The last common ancestor of chimpanzees and humans was a fruit-eating, suspensory, knuckle-walking ape” (Muller 2017a: p. 177). Lacking better fossil evidence (Arsuaga 2010), for convenience the unknown ancestor is usually assumed to be similar to recent chimpanzees. For the LCA model suggested here, simplified data on reproductive parameters of chimpanzees have been borrowed from Tutin (1979), Goodall (1991), Wallis (1997) and Nishida (1997).

“Bipedalism … appears one of the first human-like traits to evolve in the hominin lineage. The oldest of these species, Sahelanthropus tchadensis, dated between 6 and 7 million years (Ma) ago. … Species of the genus Australopithecus, dating from 1.9 to 4.1 Ma, retain several climbing adaptations. … However, the pelvis, hind limb, and foot are fully committed to terrestrial bipedalism. … The genus Homo, dating from 2.4 Ma to the present, is marked by the loss of climbing-related features in the forelimb” (Pontzer 2017: p. 272, 273). Australopithecus was bipedal, importantly feeding on grasses and sedges (Lee-Thorp et al. 2012), but an active climber (Green and Alemseged 2012), perhaps spending nights in the tree tops, similar to some recent terrestrial apes. However, Australopithecus also consumed ungulates using stone tools (McPherron et al. 2010; Domínguez-Rodrigo et al. 2012).

“Ever since molecular data firmly established that humans and chimpanzees are sister taxa, top-down approaches have generally concluded that their LCA was similar to the African great apes. … We conclude that a knuckle-walking ancestor remains the most likely reconstruction [for the LCA]” (Pilbeam and Lieberman 2017: p. 23, 111). „Common chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and the less-studied bonobos (Pan paniscus) provide the best referential models for early hominin behavior” (Falk 2004: p. 492). “Chimpanzees are known, with humans, for being the only primates able to make and use tools as well as to hunt for meat in groups” (Boesch 2009: p.1, 2).

“Chimpanzees are highly promiscuous. Females exhibit sexual swellings lasting 6–18 days during which time they attempt to mate with most or all the males of the community. Likewise, males generally attempt to mate with all swollen females, although they prefer older females” (Pusey and Schroepfer-Walker 2013). “Copulation rates increased with female age“ (Feldblum et al. 2014). “A female chimpanzee can mate with more than two dozen males in a day, at times averaging five copulations per hour. Consequently, over one ovarian cycle, a female can often expect to mate with all of the adult and adolescent males in her social group. … Female choice appears to be directed toward the goal of mating with as many males as possible, potentially to confuse paternity and reduce the risk of paternal infanticide” (Muller and Pilbeam 2017: p. 383).

„Even back then [1962?], [the chimpanzee] Flo looked age-old. She looked frail; she was gaunt and her hair, which was more brown than black, had thinned out. When she yawned, we saw that her teeth were worn down to the roof of her mouth. But … she was aggressive, tough as leather and clearly the dominating female of the whole area at that time. We … watched Flo go to the bushes and mate with one male after the other until all had their turn. … During the following week, Flo was constantly accompanied by a crowd of males. … And each time … there were unrest the group, … all the adult males mated with Flo one by one. We never saw any fighting over this extremely popular female” (Goodall 1991: p. 98, 102).

„When the first year of adolescence is over, the female’s oestral swelling gradually increases. … Even at this stage the mature males still show no interest in the young females” (Goodall 1991: p. 228). “We also unexpectedly discovered an idiopathic anovulation in some young and middle-aged chimpanzees” (Herndon et al. 2012: p. 1145). “Occasional anogenital swellings may also occur during lactation. These swellings are more erratic and less frequent than those occurring in pregnancy, but are still accompanied by sexual interest from males” (Wallis 1997). “Ovulation typically occurs on or around the last day of maximal tumescence” (Wallis 1997).

“A female generally gives birth to one offspring, and sometimes two, following a 230-day gestation period” (Ivory 2007). “The estimated median birth interval (when the offspring whose birth opens the interval does not die within the interval) is … 66.6 ± 1.3 months for chimpanzees” (Galdikas and Wood 1990: p. 185).

“The mating system of the Gombe chimpanzees is flexible and comprises three distinct mating patterns: (a) opportunistic, non-competitive mating, when an oestrous female may be mated by all the community males; (b) possessiveness, when a male forms a special short-term relationship with an oestrous female and may prevent lower-ranking males from copulating with her; and (c) consortships, when a male and a female leave the group and remain alone, actively avoiding other chimpanzees. … [In the course of 16 months,] 73% of the 1137 observed copulations occurred during opportunistic mating, 25% during possessiveness, and only 2% during consortships” (Tutin 1979).

Sexual violence or coercion is ignored in the simple LCA model suggested here. In real chimpanzee groups, however, there is sexual aggression of males against females, but this is usually related to competition between males for mating, or to female choice of preferred males (Feldblum et al. 2014). “Sexual coercion represents a specific, behavioral manifestation of sexual conflict, in which males use aggression to overcome female mating preferences” (Muller 2017b: p. 572). This kind of aggression against swollen females regards the decision on which particular male may sire an offspring, rather than the question of whether copulation may happen at all. Only the latter, however, will be in the focus here in later evolutionary stages after the LCA.

“A consequence of the sexual way of life … is the programmed death” (Margulis 1998: p. 121). “In fact, it is uncertain if female chimps ever go into menopause” (Adgate 2022).

3. Model Stage 1: Bipedalism and Concealed Oestrus

Unknown reasons had let the LCA hominins leave the treetops and begin a different life on the ground. Initially, they were knuckle-walking and feeding on grass and other plants. Gradually they developed more upright locomotion as adaption to the terrestrial living. This posture made it increasingly difficult to carry offspring on the mother’s back, in particular elder and heavier infants.

As a consequence of an earlier physical separation between mother and child, also weaning occurred earlier. Reduced inter-gestational intervals, however, are associated with increasing hazards for a child and higher offspring mortality. Earlier weaning resumes early ovulation, female swelling and pregnancy. After a new birth, the mother stops caretaking of the previous child. In the situation of early weaning those mothers gained selective advantage who exhibited less pronounced swellings and could mostly prevent premature pregnancy during the years between weaning and youth age of the child, namely, during an emerging childhood phase. If so, by natural selection, oestrus swellings became gradually more and more reduced and concealed throughout the entire population. As a consequence, the ongoing ovulation cycle without successful copulation resulted in non-fertilised eggs and a failed pregnancy which ended in abortion of the expected embryo, namely, in regular menstruation after weaning (Emera et al. 2011).

LCA reproduction rate is low, and at some point of increasingly upright gait, this falling rate may no longer ensure survival. Such a trend can be prevented by suitable changes in sexual behaviour such that the gap between weaning and next pregnancy will get wider. Because males are so far only interested in mating with swollen females, reduction of female swellings may successfully serve that purpose. If periodic ovulation continues in absence of copulation act, unfertilised ovum will be aborted by menstruation like a dead embryo. Gradually concealing the oestrus, at the cost of additional menstruations, is a method of maintaining a sufficient reproduction rate by requisite grooming of infants during their childhood, extended beyond the earlier weaning.

“The female oestrus swelling is a strong sexual signal of unclear origin; it is extremely debilitating for the females. Where is this swelling gone along the way to becoming humans? Upright gait?” (Goodall 1991: p. 240).

It is unclear yet why, how, where and when exactly the hominin transition to bipedalism took place (Richmond et al. 2001; Falk 2025). Humans may owe their present existence to an exceptional succession of specific geological and climatic circumstances. Brief reviews of various hypotheses for the emergence of bipedal locomotion are given by Sutou (2012) and Pontzer (2017).

“Notable hominin extinction, speciation, and behavioral events appear to be associated with changes in African climate in the past 5 million years” (deMenocal 2011: p. 540). “There is evidence (e.g., in airborne dust records) of substantially cooler and drier intervals in eastern Africa between 5–7 Ma (deMenocal and Bloemendal, 1995). Such climatic intervals would involve expansion of open environments” (Richmond et al. 2001: p. 97). “Data point to the prevalence of open environments at the majority of hominin fossil sites in eastern Africa over the past 6 million years” (Cerling et al. 2011: p. 51).

“After Darwin’s (1871) early speculations about the evolution of bipedalism and environmental change, the classic savanna hypothesis of Henry Fairfield Osborn and Raymond Dart attempted to link the evolutionary divergence of hominins and other great apes, and the emergence of bipedalism, with the proposed forest-savanna transition in Mio-Pliocene time” (Trauth et al. 2010: p. 2981).

“The functional significance of characteristics of the shoulder and arm, elbow, wrist, and hand shared by African apes and humans, including their fossil relatives, most strongly supports the knuckle-walking hypothesis, which reconstructs the ancestor as being adapted to knuckle-walking and arboreal climbing” (Richmond et al. 2001). “Despite decades of debate, it remains unclear whether human bipedalism evolved from a terrestrial knuckle-walking ancestor or from a more generalized, arboreal ape ancestor” (Kivell and Schmitt 2009).

“In the early days of habituation at Gombe, one of Goodall's first subjects was Flo, a then ageing female who appeared to have great reproductive success. When she died at an estimated age of 40, she had given birth to at least five healthy offspring. Her last period of postpartum amenorrhoea lasted only 3 years and 10 months ([Van Lawick-] Goodall, 1968) and … the last child died in infancy and the juvenile son preceding it died soon after Flo herself”(Wallis 1997: p. 304).

“Chimpanzees had shorter gestations after short inter-gestational intervals, and short gestations were associated with higher offspring mortality” (Feldblum et al. 2022: p. 417).

“Breast feeding … is a very predictable sort of birth control. … [Mothers] didn’t have the energy to nurse more than one set of pups at a time; it would have been suicide not to space out pregnancies. For this reason, the genetic mutations that allowed birth spacing were favoured. Once primates evolved to have fewer offspring at a time, that evolutionary legacy had a strong hold. … Ovaries stay quiet while … breasts are at work” (Bohannon 2009: p. 63).

“Children pose a problem. The extended period of childhood dependency and short interbirth intervals … is too much of an energetic burden for mothers” (Sear and Mace 2008). “Although humans have a longer period of infant dependency than other hominoids, human infants, in natural fertility societies, are weaned far earlier than any of the great apes: chimps and orangutans wean, on average, at about 5 and 7.7 years, respectively, while humans wean, on average, at about 2.5 years. Assuming that living great apes demonstrate the ancestral weaning pattern, modern humans display a derived pattern that requires explanation, particularly since earlier weaning may result in significant hazards for a child. … Modern humans that live in traditional, natural fertility societies … generally wean between 2-3 years. … At some point in our evolutionary history, then, hominins began to deviate from the ancestral pattern, weaning their youngsters at increasingly younger ages, until the modern timing, between 2-3 years, was reached” (Kennedy 2005).

“A hairless mutation introduced into the chimpanzee ⁄human last common ancestor 6 million years ago (Mya) diverged hairless human and hairy chimpanzee lineages. All primates except humans can carry their babies without using their hands. A hairless mother would be forced to stand and walk upright. … [Ape] mothers can use their four limbs freely. In sharp contrast, a human baby has nothing to grasp; the mother must hold the baby with at least one hand or more safely with both hands” (Sutou 2012). Holding the baby already right on from its birth became necessary along with the loss of fur (Jablonski and Chaplin 2000; Rantala 2007; Held 2010; Sutou 2014).

“Most ape infants can cling onto their mothers’ bodies actively by a few months after their birth, whereas human babies are slower to mature and remain dependent on their parents or carers for much longer. Indeed, most apes do not have a childhood — a period during which individuals who are weaned continue to be nurtured, mainly by their elders. … Childhood is probably a crucial innovation in human evolution. … The apelike development of Taung and other australopithecines suggests that delayed growth and childhood emerged only after the descendants of australopithecines had begun to live fully on the ground and had lost numerous arboreal adaptations” (Falk 2025).

“All hominoids grow slowly and reach reproductive age relatively late in life, and parental investment in individual offspring is high, resulting in relatively few births per female” (Kennedy 2005). “Female chimpanzees exhibit exceptionally slow rates of reproduction and raise their offspring without direct paternal care” (Pusey and Schroepfer-Walker 2013). Their “maternal care for offspring survival … showed organized attachment patterns … [that] are adaptive and have a long evolutionary history” (Rolland et al. 2025). “Most female chimpanzees are still nursing an infant when they resume postpartum [swelling] cycles and weaning may not be complete until the mother is already pregnant again (Tutin and McGinnis, 1981)” (Wallis 1997: p. 298).

4. Model Stage 2: Objectification of the Female Body, Vulva Inspection

Concealing the oestrus by suppressing the anogenital swelling is an appropriate female method of contraception by avoiding sexual intercourse and so to extend the infant’s childhood phase between weaning and youth as necessary. However, because LCA males restrict their sexual interest to swollen females only, this method will ultimately prevent pregnancies overly strongly and will reduce the reproduction rate again due to insufficient birth rates. When the infant has grown beyond 5 years of age, females lack a definite internal metabolic signal to automatically restart their sexual activity, such as ceasing breastfeeding had previously been by dismantling lactation amenorrhea (postpartum infertility).

It such a situation those males gain selective advantage who do not wait for swellings but unsightedly copulate with females regardless of any idea about her oestrus. Male sexual arousal, once triggered only by the swelling, becomes universally induced simply by any encountered female. Taking the female body as a sexual object of male’s desire is a behaviour known as objectification. This altered attitude with respect to females commences strong competition among males for having sex, as often as possible, with as many females as possible. Males who developed novel hereditary addiction to sex may have become the most successful ones in passing their genes to the following generation.

In order to ensure a sufficient reproduction rate of bipedal hominins, sexual properties have now reversed in comparison to the original LCA. Males, once sexually inactive except short occasions of mating with swollen females, need to become sexually active all the time in order to match the concealed oestrus just by chance, and to sire an own offspring. Females, on the other hand, experience regular menstruations all the time after weaning, rather than only those rare ones of adolescent LCA females. The female body as such, previously sexually ignored, becomes a permanent target of male sexual interest and hassle. The former mutually balanced, symmetric sexual activity between males and females of the LCA has been replaced by asymmetric, antagonistic sexual interests of bipeds.

Males may improve the fertilisation efficiency of their unsighted sexual approaches by detecting and avoiding females that are definitely unfertile, such as very young ones, breastfeeding ones, menstruating ones or pregnant ones. This is possible, in principle, by suitable visual, manual, oral or olfactory inspection of the female body parts, in particular of the vulva, in advance of copulation. Instinctively recognised by males as sexually attractive, or beautiful, are all those who pass this mental sieve. The previous temporary swelling criterion is substituted by a new and different, objectified permanent beauty criterion.

With respect to reproduction behaviour, beauty (Darwin 1879, Reichholf 2011, Prum 2017; Kull 2022) is a visual symbol assessed by mental prediction models for male decision-making (Feistel 2023a,b) with respect to sexual activity. “Possibly, human aesthetics emerged from sexual selection as an independent part, while the aesthetic taste developed as a part of female choice” (Miller 2000).

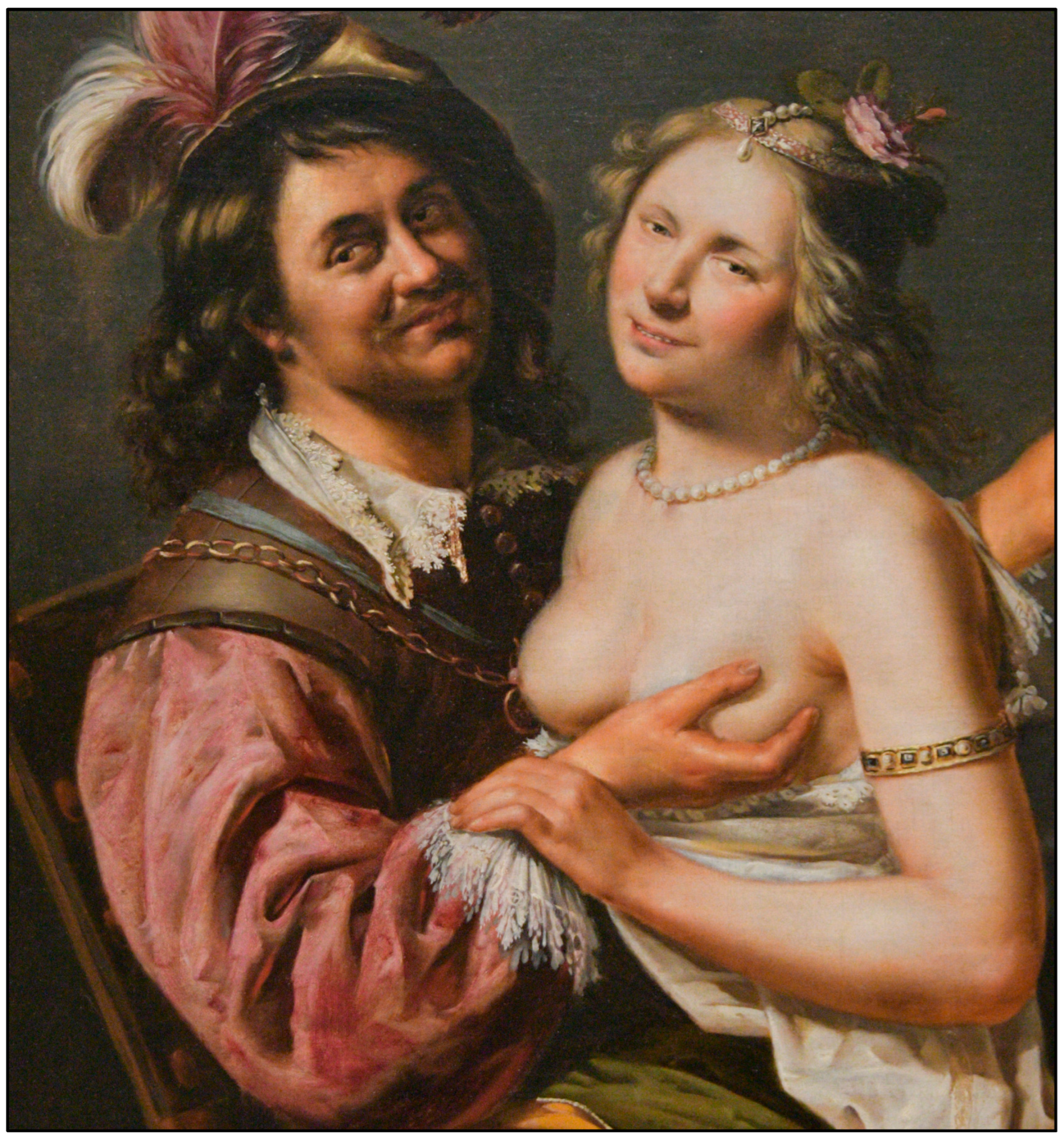

“Objectification theory [is] a framework for understanding the experiential consequences of being female in a culture that sexually objectifies the female body” (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). This theory of “seeing and treating of people as things” (Loughnan and Vaes 2017, Pecini et al. 2023) was originally meant as a feminist tool to blame sexual behaviour of men for its negative impact on women’s health. Here, however, this term is borrowed and applied to hominins without intending any ethical implication. The perhaps most explicit presentation of an objectified woman is Gustave Courbet’s disputed 1866 painting “L'Origine du monde” (Wiki 2025b), reducing a female individual to its reproductive body parts. In 2024 at Paris, this painting was attacked by radical feminists. “Too many men throughout history have spent way too much time obsessing over female genitalia but not seeing the women it’s appended to” (Sawa 2024). However, similar female objectification is already visible in ancient artwork such as the “Venus of Willendorf” from Austria, about 29 500 years old,

Figure 2.

Objectification along with persistent, compelling male desire for copulation resulted in new systematic social phenomena such as rape (forced copulation), prostitution (offering sex for food) or patriarchy (female sexual obligation upon male demand). Statistically, two thirds of German men are reported to have sex between 6 and 20 times per month (Statista 2008). As compared to the female ovulation and menstruation cycle of an entire month, for successful siring this male copulation rate is clearly oversampled, likely as a consequence of the concealed female oestrus.

5. Model Stage 3: Frigidity and Coercive Mating

The female body evolved in a way to welcome mating with males during the oestrus. After concealing the oestrus, males had to change to copulations at any time, outside or within the oestrus interval. Such a male behaviour is likely received as unwanted harassment because of lacking sexual interest and arousal of the female, commonly known as female “frigidity”. Assumingly, males will try to overcome this reluctance by coercion and aggression. This, however, may even enhance the female defence activity, perhaps by suitable clever pretext, deception or escape behaviour rather than by counter-violence.

Putative frigid behaviour during ovulation is a contraceptive method that may or may not be respected by sex-addicted males, but it likely increases the chances of infants to reach healthy maturity.

Practically no studies are available about chimpanzee frigidity, probably because this behaviour is irrelevant in those. Even in present humans, women’s “frigidity” is a somewhat tainted notion for its close relation to controversial political, legal and medical questions of the female role in the modern society and family. In modern terminology, “hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), hyposexuality, or inhibited sexual desire (ISD) is sometimes considered a sexual dysfunction, and is characterized as a lack or absence of sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity, as judged by a clinician. … In the early nineteenth century were women first described as ‘frigid’, and a vast literature exists on what was considered a serious problem if a woman did not desire sex with her husband. Many medical texts between 1800 and 1930 focused on women's frigidity, considering it a sexual pathology” (Wiki 2025c; Cryle and Moore 2011). “The notion of ‘frigidity’ … tended to encompass sterile women, women who did not desire sex of any kind with their husbands, women who experienced no orgasmic pleasure, women who had been sexually traumatized, women who desired no sex at all, women who desired no sex with men, and women who resisted or disliked penetration” (Moore and Cryle 2010: p. 244).

In the context of the hominin model, the term frigidity is not denoting any kind of disorder or disease but rather a regular, naturally evolved female reluctance against risky copulation during the infant’s childhood in favour of protecting the latter from fatal early pregnancy of the mother. In resistance against aggression and violence of physically superior males, some females may, perhaps unconsciously, have developed subtle forms of psychological harassment, a “tendency to clandestine influence by hocussing and intrigue” (Bachofen 1978: p. 122).

6. Model Stage 4: Adipose Breasts Pretending Continued Lactation

To briefly repeat what evolution steps of the hominin model had happened so far:

- (i)

Bipedalism impedes females to piggyback elder infants and shortens breastfeeding. Between weaning and a minimum age of 5 years for offspring maturity, a long childhood interval emerges during which females can avoid pregnancy by concealing their oestrus as a contraceptive measure.

- (ii)

Counteracting female’s concealed ovulation, males must frequently mate unsightly with unswollen, potentially fertile, objectified females. Fertility is actually detected by inspection of the female body to exclude unfertile female states such as youth, lactation, menstruation or pregnancy.

Counteracting male sexual approaches, in turn, to avoid early pregnancy during the childhood phase, females may exploit and misguide the fertility inspection regularly performed by males in advance of copulation. A fat matrix additionally embedded in the mammary glands (Yalom 1997; Pawłowski and Żelaźniewicz 2021; Emera 2023; Bohannon 2023) may pretend still ongoing breastfeeding and may taint the male intention to mate. In particular, such a dummy is optically cognisable already from a distance and may protect females even from male attempts of coercive mating. Adipose breasts could evolve as a simple but successful contraceptive, functioning through the entire female lifetime, as long as the lactation fake is taken for real by the males.

In order to resolve the pending systematic conflict between males and females, a suitable compromise between their opposite sexual interests would be required, for instance, a contraceptive tailored to act only during the childhood interval and becoming inactive otherwise. Rather than such a solution, unfortunately, the breast fake is only returning the ball into the field of males. To ensure survival, males need to overcome again the next female trick of avoiding copulation by, say, distinguishing between lactating and dry breasts as symbols for unfertile and fertile females, respectively. “The original driver of their evolution might not have been sexual selection” (Bohannon 2023: p. 58). As an aside, the word “breast” is derived from the old term “brustian”, meaning to swell or to bud (Duden 2014: p. 191).

Permanent breasts originally appeared in a stepwise adaptation process of natural selection as a necessary consequence of the initial female bipedalism and nakedness during motherhood. It remains unclear, however, as it is suggested by artwork as shown in

Figure 3, whether such adipose female breasts had already existed three million years ago in

Australopithecus, such as in the famous hominin “Lucy” (Bohannon 2023, Gibbons 2024). “Unlike later hominins, australopithecines spent much of their time in trees and, like other apes, probably slept there” (Falk 2025).

7. Model Stage 5: Inspection of Vulva and Breasts

Males and females may survive only if they establish an appropriately adjusted reproduction rate. Fake lactation may completely prevent this, and only those males may sire offspring who successfully distinguish lactating glands of infertile females from dry swollen breasts of fertile ones. This task may be performed by close, intimate inspection such as manually squeezing the breast or orally sucking the nipples, and visually checking erected nipples for milk excretion.

Checking the vulva has been beneficial for mating success already since Model Stage 2, in order to avoid copulation with menstruating females. Stimulating olfactory signals, copulins, secreted at the vulva during the ovulation event that once used to be visibly announced by the anogenital swelling, may also be detected by sniffing males.

Visual and olfactory signals of females are likely recognised by male chimpanzees and humans for detecting optimum opportunity to sire offspring. “Odors might be part of a multimodal fertility cue, supporting the idea that males monitor both visual and olfactory cues to gain comprehensive information on female fertility” (Jänig et al. 2022). “Recent studies have found that pheromones may play an important role in the behavioural and reproduction biology of humans” (Grammer et al. 2005).

“A mixture of five volatile fatty acids secreted vaginally, identified and named ‘copulins’, significantly increase in concentration during the follicular phase and decrease in concentration during the luteal phase in nonpill using women. Men exposed to copulins exhibit an increase in testosterone, are inhibited in discriminating the attractiveness of women’s faces, and behave less cooperatively. … Mammalian males, having low cost and high benefit from any copulatory interaction, may adaptively utilize any useful cues to identifying ovulating females and adjust their behavior accordingly in order to maximize their potential reproductive success” (Williams and Jacobson 2016).

In addition to lactational amenorrhea, note that lactose intolerance of adult hominins may be another reason for males to avoid lactating nipples. Impossible adult consumption of mother’s milk protects offspring against starvation at times of food shortage. For humans, this evolutionary imperative of mammals became relaxed only very lately (Early Neolithic) and regionally (Europe) where domestic animals permitted survival under harsh external conditions (Burger et al. 2007, 2020, Casanova et al. 2021).

8. Model Stage 6: Menopause

Female mammals experience menopause if they survive beyond exhaustion of their innate stock of egg cells. In humans and captive chimpanzees this typically happens at about 50 years of age.

In the model scenario presented here, the LCA life span of 40 years may occasionally have extended beyond menopause age for yet unknown reasons. Longevity may be caused by, say, temporal or regional beneficial living conditions, by suitable mutations, by invention of more effective tools for hunting or food preparation, such as habitual use of fire, or by advanced division of labour within the hominin group. However, a possible inherent cause for earlier menopause may be the success of previous female contraceptive measures, such as concealed oestrus and faked lactation, which imply frequent menstruation cycles after weaning and accelerated depletion of the ovary reserve.

In the sense of the nowadays widely supported “Grandmother Hypothesis” (Williams 1957; Suhr 2018) for the human menopause, the infertile old female may then assist in raising her grandchild during its childhood phase while its young mother may become pregnant again after early weaning and give birth to the next baby. This way, infertility of old females may result in short interbirth intervals and a high reproduction rate of younger females.

In this model scenario it is assumed that the occurrence of a menopause triggered a related feedback boost of the hominin population:

- -

Grandmothers can support long, protected childhood of 5-7 years despite short interbirth intervals of perhaps 2-3 years after males had overcome the female contraceptive measures.

- -

High birth frequency may double the number of offspring from 5 to 10 within a females fertile life.

- -

High reproduction rates correspond to selective advantage over adjacent, less reproductive populations and support rapid spatial distribution of the superior hominins.

- -

Safe childhood permits careful imitation, uptake and training of successful methods discovered and developed by previous adult generations.

- -

Grandmothers may spend leisure time to enhance the social division of labour by gathering or preparing food or tools.

- -

Once menopause had established similar to an advantageous mutation, its resulting benefits procure its further self-sustained existence.

Could menopause have occurred much earlier during hominin evolution? Unlikely, because concealed oestrus, objectification and lactation fake had been unnecessary inventions if grandmothers had already prevented any diminishing of the reproduction rate due to early weaning of infants by their mothers.

Could menopause have occurred much later during hominin evolution? Unlikely, because recent women of all regional cultures enjoy long postproductive lives; human menopause apparently emerged prior to the world-wide spreading of the hominin population starting at perhaps 2 Myr ago. “Stone tools recently discovered at the Shangchen site in China and dated to 2.12 million years ago are claimed to be the earliest known evidence of hominins outside Africa” (Wiki 2025a). Menopause probably caused increasing population density as well as emigration pressure by higher reproduction rates and longer life spans.

“Beginning at ages forty-five to fifty, mothers may benefit more from investing their energy and resources in existing children rather than from producing new ones. This idea became known … as the ‘Grandmother Hypothesis’” (Gurven and Gomes 2017: p. 201).

“It is sometimes assumed that the existence of menopause in humans requires no special explanation, because for most of our history’s women would rarely have lived past the age of fifty. Studies of extant foragers … falsify this assumption: grandmothers in these groups can enjoy long postreproductive lives” (Muller 2017a: p. 178). “A post-reproductive life span exists among wild chimpanzees in the Ngogo community of Kibale National Park, Uganda” (Wood et al. 2023).

“In vertebrates, the ovary develops from the gonadal primordium that eventually form a structure composed of follicles, the functional units of the ovary. … While vertebrate ovaries eventually share the same functions of producing oocytes and reproductive hormones, the ovarian morphogenesis varies from species to species … [such as in] fish, birds, and mammals” (Nicol et al. 2022: p. 2). “Ovarian … follicles grow sequentially and continue to grow until they die or ovulate. … This process is not interrupted from the time follicles are formed and continues throughout life, irrespective of reproductive status until death or until the primordial pool is depleted” (Monget et al. 2021: p. 2).

“Menopause occurs near 50 years of age in [captive] chimpanzees as it does in women. ... The chimpanzee’s life ends as reproductive function ends, while a woman may thrive for many more years” (Herndon et al. 2012: p. 1145, 1155). “[At 18-22 weeks post conception,] the human ovary contains a fixed number of [approximately 300,000] non-growing follicles established before birth that decline with increasing age culminating in the menopause at 50–51 years … when approximately 1,000 remain” (Wallace and Kelsey 2010). “Analysis suggests a universal relation between the initial follicle reserve, the depletion rates, and the threshold that triggers menopause. In addition, it is found that the distributions of menopause times are quite narrow” (Mondal et al. 2025).

“Church register entries [1720-1874] from the Krummhörn region (Ostfriesland, Germany) … [indicate that] maternal grandmothers tended to reduce infant mortality when the children were between six and twelve months of age. … The existence of paternal grandmothers approximately doubled the relative risk of infant mortality during the first month of life” (Voland and Beise 2002). “A 200-year dataset on pre-industrial Finns [shows a] … between-generation reproductive conflict among unrelated women. Simultaneous reproduction by successive generations of in-laws was associated with declines in offspring survivorship up to 66%. … Menopause evolved, in part, because of age-specific increases in opportunities for intergenerational cooperation and reproductive competition” (Lahdenperä et al. 2012).

9. Model Stage 7: Beauty of Young Mature Females

The introduction of a female menopause as a semi-active contraceptive adds another set of unfertile females to those who are too young, menstruating, pregnant or lactating. In order to avoid such females when unsightly copulating, males are more effective in reproducing own offspring if they add menopausing females to be blocked by the male mental “beauty sieve”. This way, male mating preference for older LCA females, who are now possibly beyond ovulation, turns into the opposite, namely, preference for young females between maturity and menopause.

On the female side, this altered male assessment of the female visual appearance implies that old-looking females possess only reduced chances yet to copulate with males. As a selective advantage, to become mother of the largest share among the group’s offspring, females need to compete for looking young and being the sexually most attractive ones, according to the updated male criteria of beauty.

Old LCA females are sexually most attractive to males, perhaps because conception is almost certain after copulation. By contrast, young swollen females frequently do not become pregnant after mating and are largely ignored by mature males. „Old [eligible female chimpanzee] Flo with her bulbous nose and ruffled ears is incredibly ugly by human standards” (Goodall 1991: p. 97). After the menopause has developed, the oldest females are infertile and mating with them is futile. Only females younger than menopause age may successfully be inseminated and become recognised then as the sexually most attractive ones in the male mental prediction model.

“The process that presents something to be perceived as beautiful is of the same kind as the semiotic process that builds something to become beautiful … Such a general semiotic model implies that beauty is species-specific; that it is not limited to the sphere of emotions; that the reduction of the evolution of aesthetic features to sexual selection is false” (Kull 2022).

10. Model Stage 8: Ritualisation of Vulva and Adipose Breasts

Male approaches to thoroughly inspect a female body are correctly interpreted by her as a symbol indicating his intention to copulate.

Eventually, adipose female breasts have taken over a similar function in reproductive behaviour as the anogenital swelling of chimpanzees, namely, to act as a symbolic courtship habit of presentation by females to attract the male attention and to invite them to mate.

“During their peak reproductive years, [human women] experience a high rate of conception failure. … Human ovarian cycles exhibit an unusual characteristic: most of them do not lead to conception” (Thompson and Ellison 2017: p. 217, 222). The chance for a successful pregnancy of women is only about 20 – 30% per cycle, significantly less than in all other mammals (Brosens und Gellersen, 2010; Farquharson und Stephenson, 2017).

The observational fact that all human females possess adipose breasts but in some cultures those “are not considered particularly erotic” (Gregersen 1983: p. 255), is suggesting that the human permanent breast had developed in hominin evolution long before global dispersion occurred and only later a regionally separate ritualisation to sex symbols took place. Darwin (1845) reported naked inhabitants at Terra del Fuego, Patagonia; young Afar women proudly present their bare breasts in the Ethiopian Rift Valley (Hancock et al. 1983), similar to the !Kung San of Botswana (Lee 1979), just to mention some examples of asexual topless normality in recent women. "There are still peoples where the fair sex wears its upper half of the body totally uncovered, without falling into indecorousness or immoral ideas” (Becker 1810: p. v).

In ethology, a ritualisation transition had occured “if a ritual ceremony was developing out of a useful action, … [as] the gradual change of a useful action into a symbol and then into a ritual: or, in other words, the change by which the same act which first subserved a definite purpose directly comes later to subserve it only indirectly (symbolically) and then not at all” (Huxley 1914: p. 504, 506). “An activity chain which originally served other objective or subjective purposes ends in itself as soon as it has become an autonomous ritual” (Lorenz 1983: p. 71). Indeed, the non-lactating full breast, acting as a sex symbol, does not support the original breastfeeding any longer. Originally, as a contraceptive, it symbolically pretended breastfeeding, but later the symbol’s meaning became increasingly distinct from its previous physical structure and function. Ritualisation can be understood as a general transition process from structural physical information to emergent symbolic information (Feistel 1990, 2017a,b; 2023a,b; Feistel and Ebeling 2011).

“95 percent of men are stimulating the breasts of their sex partners by kissing and suckling, 98 percent additionally by hand. Whether this happens because of their own desire, or because they believe that this is mandatory to be done – stimulating the breast is apparently a firm part of the amorous play. Does this, actually, emerge from the desire of the male, or from that of the woman?” (Olbricht 1989, p. 100). “Manipulation of the nipples/breasts causes or enhances sexual arousal in approximately 82% of young women and 52% of young men with only 7–8% reporting that it decreased their arousal” (Levin and Meston 2006). „Did men want to suck and kiss our breasts before or after it became inappropriate for women to expose their breasts?” (Dimitriadis 2015).

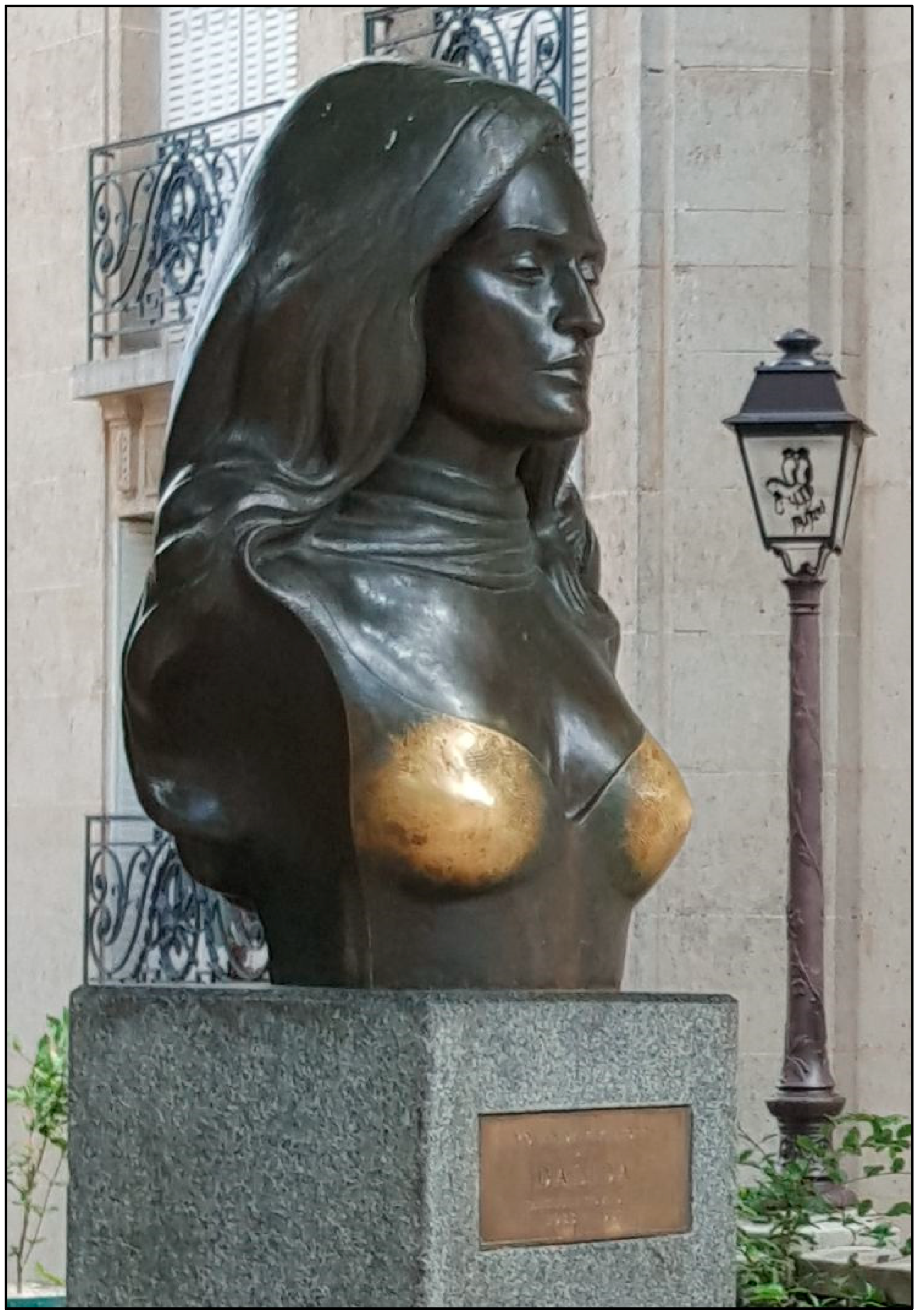

In humans, the female “breast morphology is an important physical trait in mate choice, as men find women’s breasts sexually attractive” (Garza and Pazhoohi 2024: p. 164). The well-shaped breasts of women possess some magic, sexually attractive power to many men (Becker 1810; Yalom 1997; Schipper 2020), see

Figure 4, even though this may not apply to all human cultures (Gregersen 1983). In the 2012 French film "Renoir", the famous painter admires his model by confessing that "her gorgeous tits bring you to your knees. … I would never have taken up painting if women did not have breasts." “Ponte delle Tette is a small bridge … [in Venice, Italy, that] takes its name (‘Bridge of the Tits’) from the use of the bridge by prostitutes [in the 14

th century], who were encouraged to stand topless on the bridge … to attract business. At night they were permitted to use lanterns to illuminate their breasts” (Wiki 2025g). In 2024, visitors that were frequently touching female sculptures and thereby polishing their breasts, were blamed for “sexual harassment of statues” by the feminist organisation “Terre de Femmes” (Schmid 2024).

Men’s recent desire for touching and squeezing breasts (

Figure 5) or licking and sucking their nipples is a symbolic courtship habit that emerged in this model by ritualisation from the original inherited lactation-check behaviour of males, performed to exclude already in advance any later mating with an unfertile female. Previously, with adipose breast dummies, apparent lactation had been pretended by females as a contraceptive deceit. A similar ritualisation transformation to a symbolic courtship habit regards the inherited former male check of the vulva, done to exclude infertility because of menstruation. Internet websites presenting “upskirt” or “nippledress” photos indicate persistent widespread male sexual interest in such inspection behaviour. As briefly as infamously, this male habit has prominently been formulated as “Grab ‘em by the pussy” (Wiki 2025d).

11. Discussion

Interbirth gaps and reproduction rates vary widely among recent women. Nefertiti (died about 1338 BCE), the famous wife of the Egyptian pharaoh Echnaton, gave birth to six daughters within nine years. Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1776-1810), Queen of Prussia,

Figure 5, managed 10 births in 16 years between 1794 and 1809, among those the later German Emperor William I (Wiki 2025e). Between 1963 and 1973, African !Kung women are reported (Lee 1979) to give subsequent live births after about 40 months (3.3 years) in between, resulting in 5 offspring per women on average. By contrast, in 2023 in Germany the birth rate was 1.4 per women as compared to a critical value of 2.1 for maintaining the population size. A century ago, as church records show, a number of 10 children per family was no exception in Germany, born within their mother’s fertility interval of about 20 years. “North American Hutterites … had a mean birth interval of 2 years and gave birth to more than ten children” (Bohannon 2023: p. 62). Statistically, the global average number of children per women was almost 6 in 1800, lowered down to 5 in 1948 (when this author was born), and arrived at only 2.5 yet in 2017 (Rosling 2018). Evidently, no society may escape from the hard biological consequences of Darwin’s Law: populations with subcritical reproduction rate will perish, populations with supercritical reproduction rates will grow.

Historically, high birth rates have long-lastingly and successfully been maintained despite the mother’s mortality risks, low education, poverty and poor health support, by patriarchal rigorous declaration of a “marital duty” of women (Suhr and Valentiner 2014), by Catholic proscription of contraception, divorce and abortion, and by prosecution of unfertile homosexuality. Additionally, the number of children usually served as the only available old-age provisions for the parents. The great world religions may have grown that “great” just because of their strictly enforced reproduction policy. Recently, such conditions have changed dramatically in several “wealthy” countries with increasing political, social and religious liberty of women, and with public pension insurance, where females may rather freely choose the number of births they want to give.

Figure 6.

Memorial of Queen Louise of Prussia at Hohenzieritz Palace, her place of death in 1810. Within 16 years, Louise had given birth to 10 children. Photo taken in June 2024.

Figure 6.

Memorial of Queen Louise of Prussia at Hohenzieritz Palace, her place of death in 1810. Within 16 years, Louise had given birth to 10 children. Photo taken in June 2024.

Apparently in any cultures, on average, male sexual demand seems to significantly exceed the female desire for having sex. This is evident from the existence of female prostitution, from widespread male sexual harassment (Aycock et al. 2019), violence and rape, and from high divorce rates and many single mothers in liberal societies. Effective political and legal future solutions for those grave social problems are aspired to, which, however, should address the related causes rather than just lamenting, blaming or concealing the symptoms. Obviously, revealing the most likely causes of those problems is a requisite precondition for any successful treatment. Unfortunately, causality relations cannot reliably be derived from observation but must be concluded from suitably constructed mental models (Feistel 2023a). For this reason, among others, a dedicated model of hominin sexual evolution is required.

Human sexual behaviour, as well as any other biological and social behaviour, is a collective result of individual decisions and activities. Those are controlled by separate internal prediction models implemented in each organism which exploit symbolically memorised individual experience (Feistel 2023a,b). Such experience consists of three categories: (i) ontogenetic experience that results from personal sensation during the past life, (ii) cultural experience which results from symbolic information transfer from parents, friends, teachers, books, newspapers, internet media etc., and (iii) phylogenetic experience that is inherited genetically from a long sequence of successful ancestors (Rutherford 2016; Porubsky et al. 2025; Bundell and Fox 2025). Each of those categories has its own characteristic time scale, ontogenetic experience up to a century, cultural experience covers historical millennia, and phylogenetic experience extends even back to the beginning of life, including the genetic code and the Krebs cycle (Lane 2022; Feistel 2024). Individuals are not simply passive receivers of some fixed given input of structural and symbolic information, rather, there are flexible feedback loops on all those time scales by which each individual, due to its activity, affects the experience of other humans as well as the own one, and in turn all external humans affect the individual experience in various ways.

In this paper the hypothesis is favoured that sexual conflicts in modern societies may in part have deep inherited roots in the hominin evolution, in the phylogenetic experience that was assembled by successful survival of numerous ancestor generations after the transition to bipedalism. Problems that are genetically encoded cannot be removed on short time scales like an individual life span. Only ontogenetic and cultural experience may immediately be influenced by legal or political measures, such as prosecuting sexual violence, prohibiting enforced prostitution or permitting abortion. There remain individual conflicts due to inherited phylogenetic experience, such as an instinctive addiction of men to have frequent sex but of women to avoid just that. “Not tonight, honey” (Mark et al. 2020; Boyer 2023; Harris et al. 2023).

If two opposed attitudes with respect to the sexual way of life, such as the ones assumed here of human males and females, need to coexist and cooperate in order to jointly survive, there are three possible regimes. (i) Males impose their rules on the females. This regime has traditionally been established in the patriarchy since the beginning of documented history (Lalueza-Fox et al. 2010, Copeland et al. 2011; Orlando 2023). “Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands … for the husband is the head of the wife” (King James Bible, Ephesians 5:22,23). (ii) Females impose their rules on the males. This regime may have existed in fictitious ancient matriarchies (Bachofen 1978; Engels 1884) such as the mythological Amazons (Tralow 1970; Wiki 2025f). However, matriarch social systems may have naturally faded away because their reproduction rate was probably inferior to that of patriarchies. (iii) In the future, females and males may consciously organise a fair compromise, respecting, tolerating and supporting their inherited, mutually contrary sexual interests. If possible, theoretically, this could be a preferred but perhaps challenging way of human sexual life. On longer time scales, however, by virtue of reproduction rates, evolution will inevitably take its own route of amending the human genetic pool that is steering the way men and women live together.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

I declare no conflict of interests.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

- Adgate, K. Chimpanzee Menstrual Cycles. March 22, 2022/Project Chimps. 2022. Available online: https://projectchimps.org/chimpanzee-menstrual-cycles/ (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Ahnert, L. Theorien in der Entwicklungspsychologie; Springer: Berlin, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, C.A.; Skinner, A.R.; Schwarcz, H.P.; Brain, C.K.; Thackeray, F. Further Exploration of the First Use of Fire. PaleoAnthropology 2010, 2010, A1–A40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, A. Borneo-Orang-Utan. Zoologischer Garten Rostock. 2025. Available online: https://www.zoo-rostock.de/tierpark/tierwelten/orang-utan.html (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Arsuaga, J.L. Terrestrial apes and phylogenetic trees. PNAS 2010, 107, 8910–8917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aycock, L.M.; Hazari, Z.; Brewe, E.; Clancy, K.B.H.; Hodapp, T.; Goertzen, R.M. Sexual harassment reported by undergraduate female physicists. Phys. Rev. Phys. Educ. Res. 2019, 15, 010121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachofen, J.J. Das Mutterrecht; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.H. Der weibliche Busen, dessen Schönheit und Erhaltung in seinen vier Epochen als Kind, Jungfrau, Gattin und Mutter, physisch und moralisch dargestellt; Gottfried Vollmer: Hamburg und Altona, 1810. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarik, R.G. About the Origins of the Human Ability to Create Constructs of Reality. Axiomathes 2022, 32, 1505–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarik, R.G. The Domestication of Humans. Encyclopedia 2023, 3, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berna, F.; Goldberg, P.; Kolska Horwitz, L.; Brink, J.; Holt, S.; Bamford, M.; Chazan, M. Microstratigraphic evidence of in situ fire in the Acheulean strata of Wonderwerk Cave, Northern Cape province, South Africa. PNAS 2012, 109, E1215–E1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhowmick, B.K.; Satta, Y.; Takahata, N. The origin and evolution of human ampliconic gene families and ampliconic structure. Genome Res 2007, 17, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, M.; Braun, R.; Breier, F. Wie wir Menschen wurden; Wilhelm Heyne Verlag: München, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Boesch, C. The Real Chimpanzee; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon, C. How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution; Hutchinson-Heinemann: London, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, C. Not Tonight, Honey: Why women actually don't want sex and what we can do about it; Courtney Boyer Coaching, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Brosens, J.J.; Gellersen, B. Something new about early pregnancy: decidual biosensoring and natural embryo selection. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 36, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundell, S.; Fox, D. How quickly do humans mutate? Four generations help answer the question. Nature 08 May 2025. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.; Kirchner, M.; Bramanti, B.; Thomas, M.G. Absence of the lactase-persistence-associated allele in early Neolithic Europeans. PNAS 2007, 104, 3736–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.; Link, V.; Blöcher, J.; Schulz, A.; Sell, C.; Pochon, Z.; Diekmann, Y.; Zegarac, A.; Hofmanova, Z.; Winkelbach, L.; Reyna-Blanco, C.S.; Bieker, V.; Orschiedt, J.; Brinker, U.; Scheu, A.; Leuenberger, C.; Bertino, T.S.; Bollongino, R.; Lidke, G.; Stefanovic, S.; Jantzen, D.; Kaiser, E.; Terberger, T.; Thomas, M.G.; Veeramah, K.R.; Wegmann, D. Low Prevalence of Lactase Persistence in Bronze Age Europe Indicates Ongoing Strong Selection over the Last 3,000 Years. Current Biology 2020, 30, 4307–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova, E.; Knowles, T.D.J.; Bayliss, A.; Roffet-Salque, M.; Heyd, V.; Pyzele, J.; Claßen, E.; Domboroczki, L.; Ilett, M.; Lefranc, P.; Jeunesse, C.; Marciniak, A.; van Wijk, I.; Eversheda, R.P. Dating the emergence of dairying by the first farmers of Central Europe using 14C analysis of fatty acids preserved in pottery vessels. PNAS 2021, 119, e2109325118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cechova, M.; Vegesna, R.; Tomaszkiewicz, M.; Harris, R.S.; Chen, D.; Rangavittal, S.; Medvedev, P.; Makova, K.D. Dynamic evolution of great ape Y chromosomes. PNAS 2020, 117, 26273–26280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerling, T.; Wynn, J.; Andanje, S.; et al. Woody cover and hominin environments in the past 6 million years. Nature 2011, 476, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.; Saniotis, A.; Bednarik, R.; Lindahl, M.; Henneberg, M. Hominin musical sound production: palaeoecological contexts and self domestication. Anthropological Review 2024, 87, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, S.; Sponheimer, M.; de Ruiter, D.; et al. Strontium isotope evidence for landscape use by early hominins. Nature 2011, 474, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryle, P.; Moore, A. Frigidity: An Intellectual History; Palgrave Macmillan: London, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A. The Strange Order of Things. Life, Feeling and the Making of Cultures; Pantheon Books: New York, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, C. Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited During the Voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle, round the World: Under the Command of Capt. Fitz Roy; Murray: London, 1845. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, C. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex; John Murray: London, 1879. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, C. The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection; Hurst & Co.: New York, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- deMenocal, P.B. Climate and Human Evolution. Science 2011, 331, 540–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deMenocal, P.B.; Bloemendal, J. Plio-Pleistocene variability in subtropical Africa and the paleoenvironment of hominid evolution: a combined data-model approach. In Paleoclimate and evolution, with emphasis on human origins; Vrba, E., Denton, G., Partridge, T., Burckle, L., Eds.; Yale University Press: New Haven, 1995; pp. 262–288. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriadis, K. Why can’t women take their tops off in public? Daily Telegraph Australia, 19 November 2015. 2015. Available online: https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/rendezview/why-cant-women-take-their-tops-off-in-public/news-story/c8a709372c771d577da3d4364f79a59c (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Dixson, A.F. Primate Sexuality. Comparative Studies of the Prosimians, Monkeys, Apes, and Humans; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Rodrigo, M.; Pickering, T.R.; Diez-Martín, F.; Mabulla, A.; Musiba, C.; et al. Earliest Porotic Hyperostosis on a 1.5-Million-Year-Old Hominin, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duden. Das Herkunftswörterbuch. Etymologie der deutschen Sprache; Bibliographisches Institut: Berlin, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, R.I.M. How conversations around campfires came to be. PNAS 2014, 111, 14013–14014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, F.X. Eros, Wollust, Sünde. Sexualität in Europa von der Antike bis in die frühe Neuzeit; Campus-Verlag: Frankfurt/New York, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eigen, M. The Selforganisation of Matter and the Evolution of Biological Macromolecules. Die Naturwissenschaften 1971, 58, 465–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emera, D. A Brief History of the Female Body; Sourcebooks: Naperville, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Emera, D.; Romero, R.; Wagner, G. The evolution of menstruation: A new model for genetic assimilation. Bioessays 2011, 34, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, F. Der Ursprung der Familie, des Privateigenthums und des Staats; Verlag der Schweizerischen Volksbuchhandlung: Hottingen-Zürich, 1884. [Google Scholar]

- Facchini, F. Die Ursprünge der Menschheit; Konrad Theiss: Stuttgart, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, D. Prelinguistic evolution in early hominins: Whence motherese? Behavioral and Brain Science 2004, 27, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, D. ‘Taung Child’ fossil offers clues about the evolution of childhood. Nature 2025, 638, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]