1. Introduction

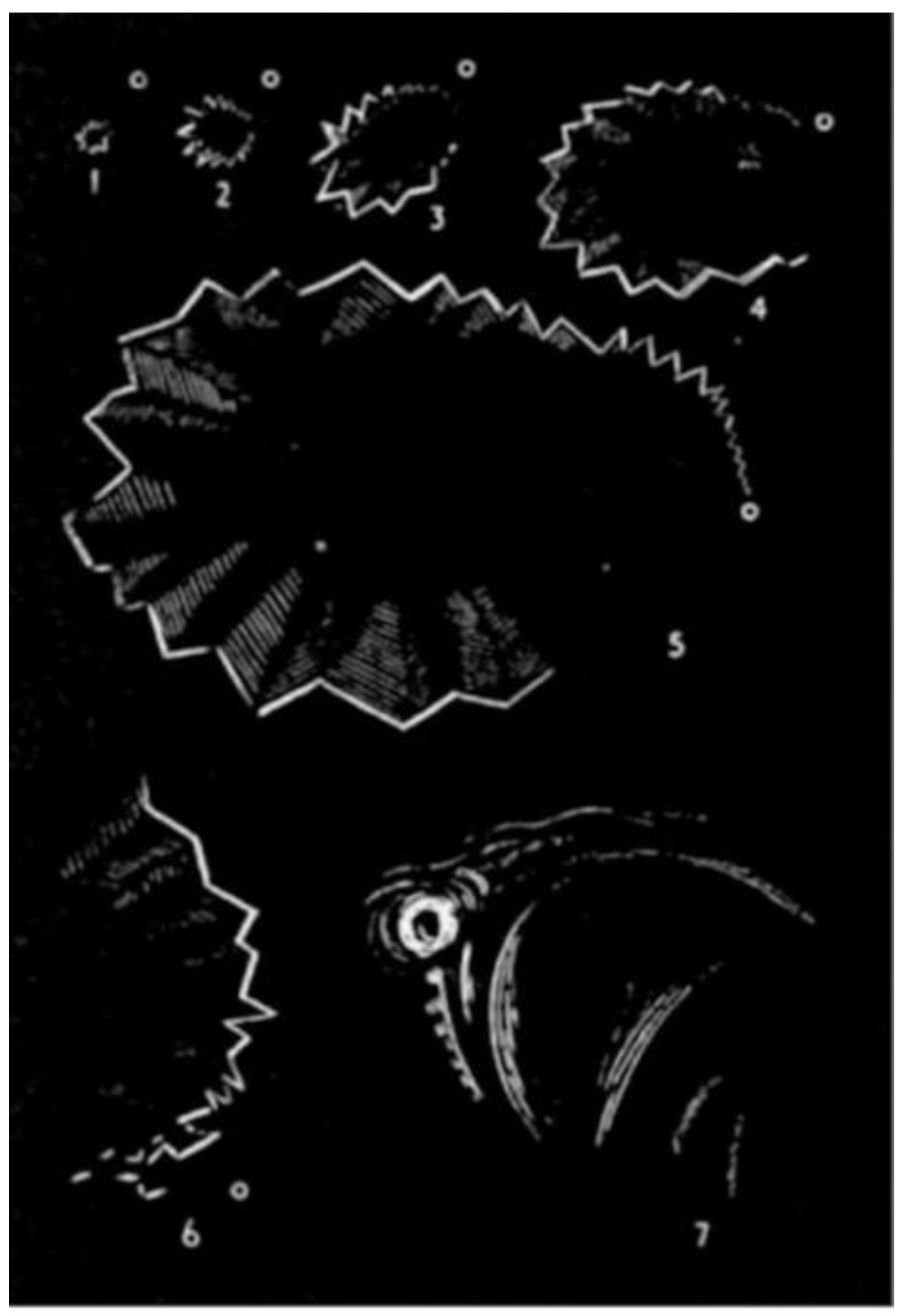

While migraine was originally thought of as a largely vasospastic disorder that leads to nociceptive chemicals being released from extracranial vessels (Wolff, 1963), the general consensus now is that it has a neurovascular aetiology. It supposes that the origin is within the brain and in the chain of events that couple a ‘neural storm’ to vascular events intracranially and extracranially leading to the headache (For review, Oleson, 2024). Migraine headaches are also very often accompanied by prodromal symptoms that are usually visual hallucinations, but also, more rarely, non-visual symptoms such as tactile hallucinations, or systemic ones such as nausea or language disturbances (Eriksen et al., 2004; Schott, 2007). The most common visual auras, as they are often referred to, are zigzag lines that are referred to as ‘fortifications’ (Airy, 1865; Plant, 1986), that usually start at or near the foveal centre and move out to the periphery as an expanding arc in about 30-40 minutes. As in

Figure 1, which is among the first recorded in a scientific journal (Airy, 1865), the fortifications are very characteristic of many migraines. The fortifications comprise pairs of lines that are almost orthogonal to each other, but they go around in an arc around the point where the aura started, which is usually in or near the centre of the fovea. The other visual auras are bright spots, or scintillating lines or dark areas, which also move across from the fovea to the periphery. While there have been many attempts at modelling the intriguing appearance of zigzag lines and their movement across the visual field (Reggia & Montgomery,1996; Dahlem et al., 2000; Dahlem & Chronicle, 2004; Zhaoping & Li, 2014), they have not led to predictions that can be subjected to feasible experimental tests (O’Hare et al., 2021). Most models have indeed attempted to base their computation on the functional architecture of the primary visual cortex (Hubel & Wiesel, 1962, 1968; Grinvald et al., 1986; Ohki et al., 2006), which shows an orderly progression of orientation columns. However, the models have not taken into account the mechanistic basis of orientation selectivity and orientation columns (Vidyasagar et al., 1996; Vidyasagar & Eysel, 2015; Kremkow & Alonso, 2018) and the way feature selectivities in the subcortical signals (Levick & Thibos, 1982; Vidyasagar & Urbas, 1982; Vidyasagar & Heide, 1984; Shou & Leventhal, 1989; Pei et al., 1994; Passaglia et a., 2002; Mohan et al., 2019) to visual cortex are processed by intracortical circuitry (Vidyasagar & Eysel, 2015). We believe that this process holds the clue for the peculiar nature of fortifications, which usually present with only a pair of near orthogonal contours and in fact may give insight to the other prodromal symptoms as well.

We describe below a model that (i) explains the perception of the fortifications based on the processing of thalamic signals by the visual cortical circuitry (ii) leads to predictions of the which can be tested on an animal model such as the cat or the macaque (iii) provides a basis for the explanation of other types of prodromal symptoms, including non-visual ones (iv) explains why sensory aura and headache can also occur independently (v) places the prodromal symptoms in a causal relationship to headache and (vi) leads to an experimental paradigm that can be developed as a method of testing novel therapeutic measures.

2. Is Cortical Spreading Depression (CSD) a Neural Correlate of Visual Auras?

In a pioneering series of papers, Leão (Leão, 1944, 1947; Leão & Morison, 1945) demonstrated that mammalian cortex is susceptible to a wave of excitation followed by a longer lasting depression, which he called ‘cortical spreading depression’. CSD could be triggered by any of a number of factors such as focal electrical stimulation, potassium chloride (KCl), injury and hypoxia. It is the emerging view that the visual aura of migraine is caused by a cortical spreading depression that sweeps across the visual cortex (Charles & Baca, 2013). CSD can be recorded from the cortical surface and also visualised by optical imaging in animal experiments. CSD in animal models show the same temporal pattern as the aura experienced by humans. Genetic studies point to CSD as the mechanism underlying the aura of migraine (for reviews, Charles & Boca, 2013; Oleson, 2024). Drugs effective in treating migraine have also been shown to be effective in preventing CSD in animal models (Ayata etal., 2006). However, it has been impractical to demonstrate CSD from intracranial recordings in humans during a visual aura, but recently the feat was possible in a human patient implanted with 94 electrodes in the cortex for evaluating a seizure disorder (McLeod et al., 2025).

3. Cortical Circuitry Underlying the Pattern of Visual Auras

We propose here a model based on current experimental evidence that not only explains fortifications, which are the most common of the prodromal symptoms, but also other types of auras and the lack of them in some cases. The crucial circuit principle that forms the basis for the percept of fortification is the way orientation selectivities of visual cortical cells are created. The band-pass orientation tuning, with responses only to a narrow range of stimulus orientations, is a characteristic of many cells in area V1 (Hubel & Wiesel, 1962, 1968). Cells having the same preferred stimulus orientation are also clustered in orientation columns. Hubel and Wiesel had also proposed that the orientation tuning arises de novo in V1. However, mild degrees of orientation selectivity are seen at earlier levels of the visual pathway, viz., in the retina (Levick & Thibos, 1982: Passaglia et al., 2002) and in the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) of the thalamus (Vidyasagar & Urbas, 1982; Shou & Leventhal, 1989). This raises the possibility that cortical orientation selectivity arises from sharpening of the orientation bias in the thalamic signals arriving in the striate cortex, a thesis supported by many studies - theoretical, experimental and computational (Vidyasagar, 1987; Vidyasagar & Heide, 1984; Pei et al., 1994; Vidyasagar et al., 1996; Kuhlman & Vidyasagar, 2010; Vidyasagar et al., 2015; Vidyasagar & Eysel, 2015; Mohan et al., 2019; Davey et al., 2022). This leads to the conundrum that if a response property is coded already in the retina, to retain spatial resolution across the limited retinal surface, it has to be done by a limited number of broadly tuned (primary) channels, such as in Cartesian (orthogonal) coordinates (Vidyasagar, 1985, 1987). This is well-known in the case of primate trichromatic colour vision, where the brain builds sensitivity for a very wide range of hues from the relative excitation of just 3 types of retinal cones. This is precisely what is likely the case with coding orientation (Vidyasagar & Eysel, 2015): (i) In the retina (Levick & Thibos, 1982) and in LGN (Vidyasagar & Urbas, 1982; Shou & Leventhal, 1989), the orientation biases are mainly limited to two orientations, viz., in most cells to the ‘radial’ orientation (i.e., along a line pointing to the centre of the retina) and in others to its orthogonal. (ii) Cortical orientation selectivity depends upon the orientation biases in its thalamic input (Vidyasagar, 1992).

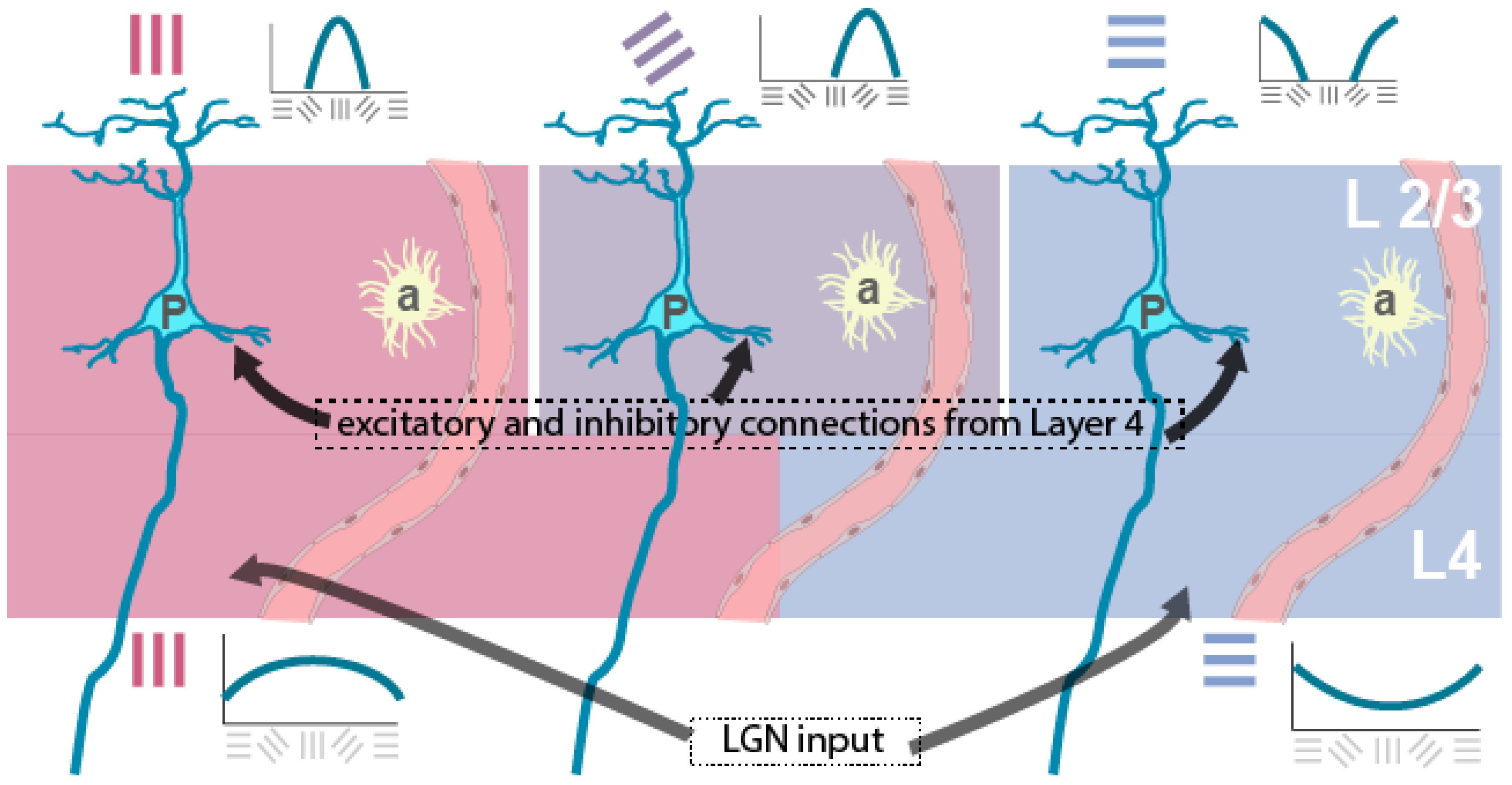

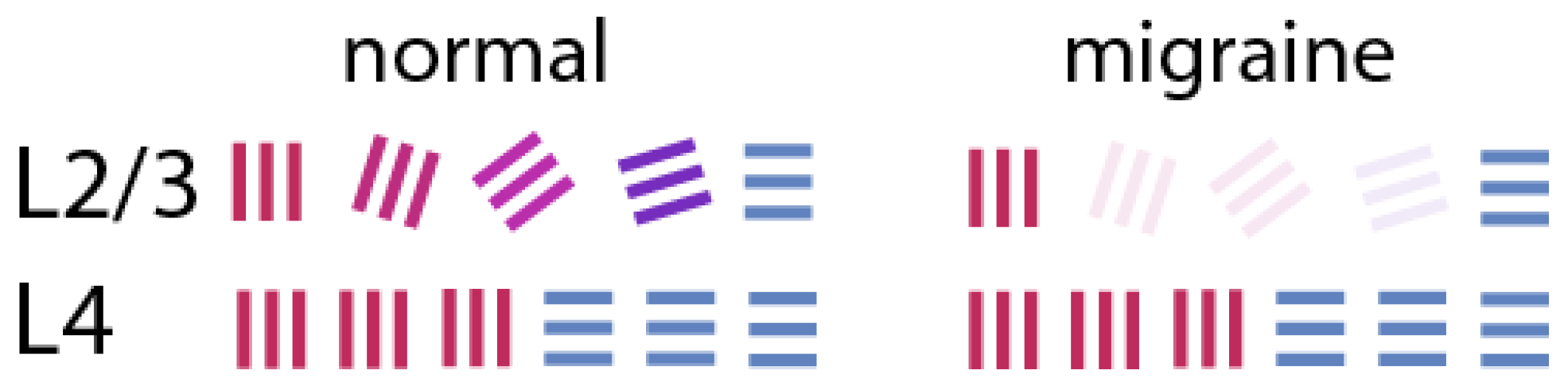

Such elaboration of the spectrum of preferred orientations from Cartesian coordinates requires the operation of intracortical excitation and inhibition on the thalamic signals (Volgushev et al., 1993; Pei et al., 1996; Somers et al., 1995; Vidyasagar & Eysel, 2015; Hage et al., 2022). This transformation happens partly in the visual cortical layer 4, to which geniculate signals project to in carnivores such as cats (Hubel & Wiesel, 1962), but in animals evolutionarily closer to humans such as non-human primates (Hubel & Wiesel, 1968; Bulllier & Henry, 1980) and tree shrews (Bosking et al. 1997; Mooser et al. 2004; Van Hooser et al. 2013; Mohan et al., 2021) such transformation happens only in layer 2/3 (

Figure 2). The orderly arrangement of the gamut of orientation domains in supragranular layer 2/3 has also been repeatedly observed in studies using optical imaging of intrinsic signals (OI) (Grinwald et al., 1986; Ohki et al. 2006; Mohan et al. 2019). Autoradiographic studies that radioactively label active regions in the cortex have also been used to demonstrate orientation columns in layer 2/3, where when gratings of one specific orientation was shown after injection of radioactively labelled 2-deoxyglucose, dense periodic labelling was seen in the autoradiograph (Hubel et al., 1978). On the other hand, layer 4, where cells have only an orientation bias reflecting the well-known retinal and geniculate biases, was uniformly labelled.

The neural representation of a spectrum of orientation selectivities can be extracted from an input where the information is coded in just two Cartesian co-ordinates as described earlier, but then the tuning has to be necessarily broad before an intracortical circuitry involving local excitatory and inhibitory neurons can process the signals (Vidyasagar, 1987; Kuhlmann & Vidyasagar, 2011; Vidyasagar & Eysel, 2015).

Figure 2 represents such a scheme. The model that Vidyasagar & Eysel (2015) described constructs the cortical functional architecture from nodes that each code for a combination of three inherent properties of geniculate afferents – eye of origin (right or left), preferred stimulus orientation (one of two orthogonal orientations) and ON- or OFF- centre receptive field (see their

Figure 2).

The above scheme lays the foundation for our understanding of the fortifications. The cortical spreading depression, till now the strongest contender to be the basis of the aura, is usually a travelling wave on the cortex, characterised by a brief wave of excitation followed by a long period of depression. We propose that the initial sweep of depolarisation and the associated depolarisation block in cell classes that are more active can lead to a situation that can cause the perception of fortifications: Of the many possible events suggested as triggers for CSD, the one most favoured is an increase in extracellular potassium ion (K

+) concentration (Busija et al., 2008; Charles & Baca, 2013). The shift in membrane potential that leads to a wave of depolarisation presumably leads to high neuronal firing rates, especially in a cortex prone to hyperexcitability, as the migraineur’s (Coppola et al., 2007: Nguyen et al., 2018). Inhibitory interneurons, being faster spiking cells than others, are known to be metabolically more demanding and are more susceptible for hypoxic conditions or higher extracellular potassium (K

+) concentrations. They and many excitatory interneurons would potentially go into a depolarisation block from the high spike rates and the increase in extracellular K

+ concentration (Fröhlich et al., 2008). In our above scheme for elaboration of the whole set of orientation domains from a set of Cartesian co-ordinates, normal functioning of the interneurons is critical. Their full or partial suppression from the depolarisation block would cause layer 4 signals to be transmitted largely unchanged in their preferred stimulus orientations to the layer 2/3 P cells, which are the pyramidal cells that are the main output neurons of V1 to higher brain centres leading to conscious perception (

à la Figure 2). This means that activation in the output neurons of V1 would be largely restricted to those coding for the radial orientation and its near orthogonal (

Figure 3) – an outcome similar to those usually seen in published image

s of the fortifications as in Figure 1.

4. Visual Auras Other Than Fortifications

In some cases, the auras are simply a dark area or a bright area of scotoma or scintillating lines. Rarely, there are also auras that have complex shapes and objects. We believe that these all neatly fit into our scheme. Variations in the degree of change in the K+ concentration that causes the initial wave of depolarisation can potentially explain many of these phenomena. With high K+ levels, the depolarisation block that can result may extend to all cells in layer 2/3, causing a dark (negative) scotoma instead of fortifications. On the other hand, if the spike in K+ concentration is mild, it may not lead to depolarisation block in any of the cells but cause adequate depolarisation in all visual cells and such activation of cells belonging to all orientation domains would not allow any structured perception, but only either a bright scotoma or just scintillating lines. More complex, but rarer, visual auras and hallucinations have also been reported (Sacks, 1992), but they are more likely due to either a CSD in a higher visual cortical area or propagation of the striate cortical CSD to higher visual areas. The higher frequency of simple visual auras such as fortifications may simply be due to the larger relative expanse of V1 and the higher excitability and oxygen demands of this area. The strong connections that many of the over 30 different visual areas have to a range of brain regions (Fellman & Van Essen, 1991; Glasser et al., 2016), including the limbic system and insula, mean that headaches can also be preceded by complex non-visual prodromal symptoms.

5. Neurovascular Link Between Visual Auras and Local Vascular Supply

Much research has pointed to the role of astrocytes in regulating local vascular supply depending upon the level of neuronal activity (Zonta et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2024). Schummers et al. (2008) showed in the ferret V1 that astrocytes function together with a small cluster of local neurons to regulate the local vascular supply. In response to visual stimuli, the calcium influx in astrocytes triggered by glutamate release from the nearby neurons show the same response properties such as orientation selectivity of those neurons. In turn, the astrocytes enhance blood supply to the same localised region by causing arteriolar vasodilation in nearby vascular bed. This effectively helps in the shunting of blood to the more active regions. A recent study by O’Herron et al. (2016) comparing the orientation tuning of spiking activity and vascular responses is consistent with our scheme outlined above. Their study found that in cats which have well-structured orientation columns, the spiking activity of layer 2/3 matched local vascular responses in layer 2/3 but the vascular response that reflected deeper (presumably layer 4) layer spiking activity had poor orientation selectivity. Furthermore, in rats that lack orientation maps and with cells having different preferred stimulus orientations not being segregated, the vascular responses show no orientation selectivity.

6. Sequence of Events from CSD/Aura to Intracranial Vasodilation and Headache

There has been a general consensus that vasodilations of intracranial and extracranial vessels are linked to the pain of migraine headaches. There is also evidence for the release of nociceptive chemicals from vasodilation and for convergence of nociceptive signals from intracranial and extracranial afferents in the trigeminocervical complex (Oleson et al. 2009; Noseda et al. 2013; Levy et al., 2018). Besides pain being referred to the scalp due to the above convergence, activation of the complex from nociceptive signals from intracranial vessels can also lead to vasodilation of the extracranial vessels in the scalp and release of nociceptive chemicals (Hoffmann et al., 2017). Thus, the primary cause for the headache may arise from CSD and the auras are a manifestation of the CSD. This view also opens up the possibility of developing animal models to visualise an aura by optical imaging of the march of CSD across the orientation domains. Such a model may be used also to develop therapeutic approaches, either in developing novel drugs or behavioural techniques such as exposure to specific visual stimuli, to abort the CSD or its effects.

Acknowledgments

We thank Luis Alcaron-Martinez and Mark Cook for discussions and Ekaterina Levichkina for making the figures.

References

- Airy H (1865) On a transient form of hemianopsia. Phils Trans R Soc London 160:247-270.

- Ayata C, Jin H, Kudo C, Dalkara T, Moskowitz MA (2006) Suppression of cortical spreading depression in migraine prophylaxis. Ann Neurol. 59:652-61. [CrossRef]

- Bosking W, Zhang Y, Schofield B, Fitzpatrick D (1997) Orientation selectivity and the arrangement of horizontal connections in tree shrew striate cortex. J Neurosci 17:2112–2127. [CrossRef]

- Bullier J, Henry GH. 1980. Ordinal position and afferent input of neurons in monkey striate cortex. J Comp Neurol. 193: 913-935. [CrossRef]

- Busija DW, Bari F, Domoki F, Horiguchi T & Shimizu K. (2008) Mechanisms involved in the cerebrovascular dilator effects of cortical spreading depression. Prog. Neurobiol. 86, 417–433. [CrossRef]

- Charles AC & Baca SM (2013) Cortical spreading depression and migraine. Nat Rev Neurol 9:637-644. [CrossRef]

- Coppola G, Pierelli F, Schoenen J. (2007) Is the cerebral cortex hyperexcitable or hyperresponsive in migraine? Cephalalgia. 27:1427-39. [CrossRef]

- Dahlem M, Chronicle E (2004) A computational perspective on migraine aura. Prog. Neurobiol. 74, 351–361. [CrossRef]

- Dahlem M, Engelmann R, Löwel S, Müller S. (2000) Does the migraine aura reflect cortical organization? Eur. J. Neurosci. 12, 767–770. [CrossRef]

- Davey CE, Lloyd EKJ, Kuhlmann L, Burkitt AN & Vidyasagar TR. (2022) A neural framework for spontaneous development of orientation selectivity in the primary visual cortex. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen M, Thomsen L, Andersen I, Nazim F, Olesen J (2004) Clinical characteristics of 362 patients with familial migraine with aura. Cephalalgia 24:564–575. [CrossRef]

- Fellman DJ & Van Essen DC (1991) Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex 1:1-47. [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich F, Bazhenov M, Iragui-Madoz V & Sejnowski TJ (2008). Potassium Dynamics in the epileptic cortex: New insights on an old topic. The Neuroscientist, 14(5), 422–433. [CrossRef]

- Glasser MF et al. (2016) A muti-modal parcellation of human cerebral cortex. Nature 536:171-178. [CrossRef]

- Gowers WR. (1904) Subjective sensations of sight and sound: Abiotrophy and other lectures. Trans Ophthal Soc UK. 15:1–39.

- Grinvald A, Lieke E, Frostig RD, Gilbert CD & Wiesel TN (1986) Functional architecture of cortex revealed by optical imaging of intrinsic signals. Nature 324:361–364. [CrossRef]

- Hage TA et al. (2022) Synaptic connectivity to L2/3 of primary visual cortex measured by two-photon optogenetic stimulation. eLife 11:e71103. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann J, Baca SM, Akerman S (2019) Neurovascular mechanisms of migraine and cluster headache. J Cer Blood Flow Metab. 39:573-94. [CrossRef]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN (1962) Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat’s visual cortex. The Journal of physiology, 160:106-154. [CrossRef]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN (1968) Receptive fields and functional architecture of monkey striate cortex. The Journal of physiology, 195:215-243. [CrossRef]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN, Stryker MP (1978) Anatomical demonstration of orientation columns in macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 177:361-380. [CrossRef]

- Kremkow J, Alonso JM (2018) Thalamocortical circuits and functional architecture. Annu Rev Vis Sci. 4:1–23. [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann L, Vidyasagar TR (2011) A computational study of how orientation bias in the lateral geniculate nucleus can give rise to orientation selectivity in primary visual cortex. Front Syst Neurosci. 5:81. [CrossRef]

- Leão AA (1944) Spreading depression of activity in the cerebral cortex. (1944) J. Neurophysiol. 7, 359–390. [CrossRef]

- Leão AA (1947) Further observations on the spreading depression of activity in the cerebral cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 10, 409–414. [CrossRef]

- Leão AA & Morison RS Propagation of spreading cortical depression. (1945) J. Neurophysiol. 8, 33–45. [CrossRef]

- Levick WR, Thibos LN. 1982. Analysis of orientation bias in cat retina. J Physiol. 329:243–261. [CrossRef]

- Levy D, Labastida-Ramirez A & DenBrinck A. (2019) Current understanding of meningeal and cerebral vascular function underlying migraine headache. Cephlalgia 39:1606-22. [CrossRef]

- McLeod GA, Josephson CB, Engbers JDT, Cooke LJ (2025) Mapping the migraine: Intracranial recording of cortical spreading depression in migraine with aura. Headache 65:658-665. [CrossRef]

- Mohan Y, Jayakumar J, Lloyd EKJ, Levichkina E & Vidyasagar TR (2019) Diversity of feature selectivity in macaque visual cortex arising from a limited number of broadly tuned inputs. Cerebral Cortex 29:5255-5268. [CrossRef]

- Mooser F, Bosking WH, Fitzpatrick D (2004) A morphological basis for orientation tuning in primary visual cortex. Nat Neurosci 7:872–880. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen BN, McKendrick AM & Vingrys AJ (2016) Abnormal inhibition-excitation imbalance in migraine. Cephalalgia 36:5-14.

- Noseda R & Burstein R (2013) Migraine pathophysiology: Anatomy of the trigeminovascular pathway and associated neurological symptoms, cortical spreading depression, sensitization, and modulation of pain. Pain 154: S44–S53.

- O’Hare L, Asher JM & Hibbard PB (2021) Migraine visual aura and cortical spreading depression – linking mathematical models to empirical evidence. Vision 5:30. [CrossRef]

- O’Herron, et al. Kara P (2016) Neural correlates of single-vessel haemodynamic responses in vivo. Nature 534:378-382.

- Ohki, K. et al. (2006) Highly ordered arrangement of single neurons in orientation pinwheels. Nature 442:925–928. [CrossRef]

- Oleson J (2024) Cerebral blood flow and arterial responses in migraine: history and future perspectives. J Headache & Pain 25:222.

- Passaglia CL, Troy JB, Ruttiger L, Lee BB. 2002. Orientation sensitivity of ganglion cells in primate retina. Vision Res. 42:683–394.

- Pei X, Vidyasagar TR, Volgushev M, Crutzfeldt OD (1994) Receptive field analysis and orientation selectivity of postsynaptic potentials of simple cells in cat visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 14, 7130–7140.

- Plant GT (1986) The fortification spectra of migraine. Brit Med J. 293:1613-1617. [CrossRef]

- Reggia JA, Montgomery D (1996) A computational model of visual hallucinations in migraine. Comput. Biol. Med. 26:133–141.

- Schummers J, Yu H & Sur M (2008) Tuned responses of astrocytes and their influence on hemodynamic signals in the visual cortex. Science 320:1638-1643.

- Shou TD, Leventhal AG. (1989) Organized arrangement of orientation-sensitive relay cells in the cat’s dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurosci. 9:4287-4302.

- Somers DC et al. (1995) An emergent model of orientation selectivity in cat visual cortical simple cells. J. Neurosci. 15:5448–5465.

- Van Hooser SD, Roy A, Rhodes HJ, Culp JH, Fitzpatrick D (2013) Transformation of receptive field properties from lateral geniculate nucleus to superficial V1 in the tree shrew. J Neurosci 33:11494–11505.

- Vidyasagar TR (1987). A Model of striate response properties based on geniculate anisotropies. Biol. Cybern. 57:11-23.

- Vidyasagar, T.R. (1992) Contribution of subcortical mechanisms to orientation sensitivity of cat striate cortical cells. Neuroreport 3:185–188.

- Vidyasagar TR, & Eysel UT (2015) Origins of feature selectivities and maps in the mammalian primary visual cortex. Trends Neurosci. 38:475–485.

- Vidyasagar TR & Heide W (1984) Geniculate orientation biases seen with moving sine wave gratings: implications for a model of simple cell afferent connectivity. Exp Brain Res 57:196-200. [CrossRef]

- Vidyasagar TR, Jayakumar J, Lloyd E & Levichkina EV (2015) Sub- cortical orientation biases explain orientation selectivity of visual cortical cells. Physiol Rep. 3:e12374.

- Vidyasagar TR, Pei X & Volgushev M (1996) Multiple mechanisms underlying the orientation selectivity of visual cortical neurones. Trends Neurosci. 19:272–277.

- Vidyasagar TR, Urbas JV. 1982. Orientation sensitivity of cat LGN neurones with and without inputs from visual cortical areas 17 and 18. Exp Brain Res. 46:157–169. [CrossRef]

- Wolff HG (1963) Headache and other head pain, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press.

- Yang M-f, et al. (2024) The Role of astrocytes in migraine with cortical spreading depression: protagonists or bystanders? A Narrative review. Pain Ther 13:679-690.

- Zhaoping L, Li Z (2014) Understanding Vision: Theory, Models, and Data; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA.

- Zonta M., et al. (2003). Neuron-to-astrocyte signalling is central to the dynamic control of brain microcirculation. Nature Neuroscience, 6, 43-50.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).