1. Introduction

Die Sinking Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM) is widely acknowledged as an advanced and key manufacturing process, particularly for fabricating complex geometries with materials that are traditionally difficult to machine. This technique operates through a controlled sequence of electrical discharges, facilitated by a dielectric fluid, with the aim to achieve a very high surface finish [

1]. As presented in

Figure 1, the erosion process replicates the contour of the electrode, thereby achieving high fidelity in the reproduction of complex shapes, a feature that is critically important for high-precision sectors such as aerospace, automotive, and tooling, where conventional machining methods are often inadequate [

2,

3]. Products produced using such techniques are moulds and dies or fully machined impellers for the energy sector. Despite its significant advantages, die-sinking EDM faces challenges owing to its inherent energy-intensive nature and the complexities associated with its operational parameters. Key machining factors—namely, electrical current, applied voltage, and pulse duration—exhibit a multifaceted correlation that directly affects the material removal rate (MRR), overall machining time, and surface integrity of the workpiece [

4]. Consequently, achieving optimal process performance required a fine tuning of these parameters to enhance productivity while concurrently mitigating environmental and economic costs [

5].

In response to these challenges, considerable research efforts have been directed toward developing advanced solutions. Innovations have focused on designing and implementing high durability electrode materials and geometries that significantly enhance machining precision and efficiency [

6]. Simultaneously, the energy consumption of die-sink EDM machines has emerged as a critical metric influenced by multiple factors, including the nature of the discharge process, auxiliary systems, and machine design. Therefore, accurate measurement and control of energy consumption are essential not only for improving machining efficiency but also for reducing operational costs and minimising environmental impacts. This growing emphasis on environmental footprint of manufacturing processes has led to the development of energetic models that provide a robust framework for evaluating overall energy utilization in machining processes. These models systematically analyse the power absorbed by all the machine subsystems by employing both system sizing (e.g., subsystem nominal power) and direct measurement techniques to accurately determine total power consumption during machining operations [

6,

7,

8].

This quantitative approach facilitates a comprehensive understanding of energy distribution throughout the process, enabling precise assessments that are critical for optimising the performance. Moreover, by incorporating the energy demands of auxiliary systems—such as chillers that often impose a significant energy burden on micro-EDM machines—these models empower manufacturers to identify and target specific areas for energy consumption optimization [

9,

10]. Complementing these energetic models, discharge-based models offer a focused perspective on the dynamics of the electrical discharge process by correlating essential machining parameters—such as current, voltage, and pulse timing—with the material removal rate (MRR), thereby providing estimates of the energy required for effective material removal [

4,

6]. This targeted analysis enhances the ability to fine-tune machining operations by directly linking the process parameters with the energy efficiency outcomes. Further insights are gained by isolating the energy consumed during active discharges from that used by auxiliary systems, which yields valuable data to assess and improve the intrinsic performance of the process itself [

11].

Advancements in measurement techniques have led to the integration of real-time monitoring systems into modern machining environments. These systems combine advanced sensors with sophisticated data acquisition techniques to continuously track energy consumption across all machine subsystems, enabling prompt detection of inefficiencies and allowing operators to dynamically adjust process parameters to maintain optimal energy use [

8,

9]. In addition to these systems, acoustic emission (AE) monitoring techniques have emerged as non-invasive methods for assessing energy fluxes during machining operations. By analysing the vibroacoustic signals generated during material removal, AE monitoring provides a real-time evaluation of the energy expended, ensuring that the process maintains optimal performance without disrupting the operational workflow [

12].

An important concept to evaluate the energy efficiency is the of Specific Energy Consumption (SEC) metric, which is the energy consumed to remove a standard volume of material, crucial to assess the overall efficiency of an EDM process. Hence, the SEC provides a valuable comparative framework for evaluating the performance of different machining setups. This metric is particularly beneficial for contrasting the energy performance of conventional EDM technologies with that of more advanced systems, thereby driving further process improvements and optimization [

13,

14].

At the heart of these energy considerations lies the complex relationship between the material removal rate (MRR) and machining parameters in die-sinking EDM, a relationship characterised by nonlinear interactions and trade-offs. A thorough understanding of these correlations is critical for optimising the process to achieve high productivity and energy efficiency, while maintaining surface quality. In advanced machining processes, several key electrical parameters play a decisive role in influencing both the MRR and the overall process performance. One of the most influential of these parameters is the peak current (Iₚ); a peak in current intensity that amplifies the energy delivered during each electrical discharge, thereby accelerating the material removal process. However, this benefit is counterbalanced by elevated thermal loads, which can adversely affect the surface finish and accelerate electrode wear [

15,

16]. This relationship between current and MRR is particularly significant in applications such as mold-making and aerospace manufacturing, where the demand for rapid material removal often takes precedence over the need for a high-quality surface finish [

17].

Complementing the role of current, voltage (V

ₓ) is fundamental in regulating the energy transfer during each discharge. Maintaining an optimal voltage level is essential for ensuring stable sparking conditions that promote uniform material erosion; conversely, excessive voltage can lead to arcing and unstable discharge conditions, which detrimentally affect both the MRR and the quality of the machined surface [

17,

18]. Furthermore, the pulse timing parameters, specifically the pulse-on time (T

ₒₙ) and pulse-off time (T

ₒff), further refined the efficiency of material removal. Extended pulse-on times facilitate greater energy transfer per discharge, thereby enhancing the MRR, but the increased energy transfer also elevates the risk of thermal damage to both the workpiece and the electrode, potentially compromising surface integrity [

16]. In contrast, shorter pulse durations focus the energy delivery more precisely, reducing the heat-affected zones, although this approach may limit the overall material removal rate. Additionally, the pulse-off time is critical as it governs the recovery period for the dielectric fluid and ensures the effective removal of debris; insufficient off time may result in erratic discharges, diminishing process efficiency and intensifying electrode wear [

17].

Ultimately, the intricate correlation between these electrical parameters underscores the necessity for a holistic optimization strategy, where adjustments made to enhance one parameter often require compensatory modifications in others to sustain process stability and efficiency. For instance, increasing the current to boost the MRR may necessitate a reduction in pulse duration or voltage to mitigate the risks associated with thermal damage and excessive electrode wear [

19]. Through such a balanced and integrated approach, manufacturers can effectively tailor the die-sinking EDM processes to meet specific operational demands while achieving high levels of precision and energy efficiency.

Most existing EDM energy models either focus narrowly on theoretical discharge behavior or separately analyze machine-level energy consumption, often overlooking real-time integration and the influence of auxiliary systems. Additionally, they rarely account for the practical implications of electrode design on energy efficiency and tool wear. This study addresses these gaps by introducing a holistic, experimentally validated modeling approach that integrates real-time energy monitoring across all subsystems with actual machining outcomes. A key novelty is the use of a simplified, standardized graphite electrode across all trials, which ensures consistent volume removal and enables accurate comparisons of specific energy consumption under varying process settings. This allows for a deeper understanding of how parameter changes impact both energy use and electrode degradation—delivering actionable insights for optimizing EDM processes in both performance and sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study an Agie Charmilles FORM 3000 VHP presented in

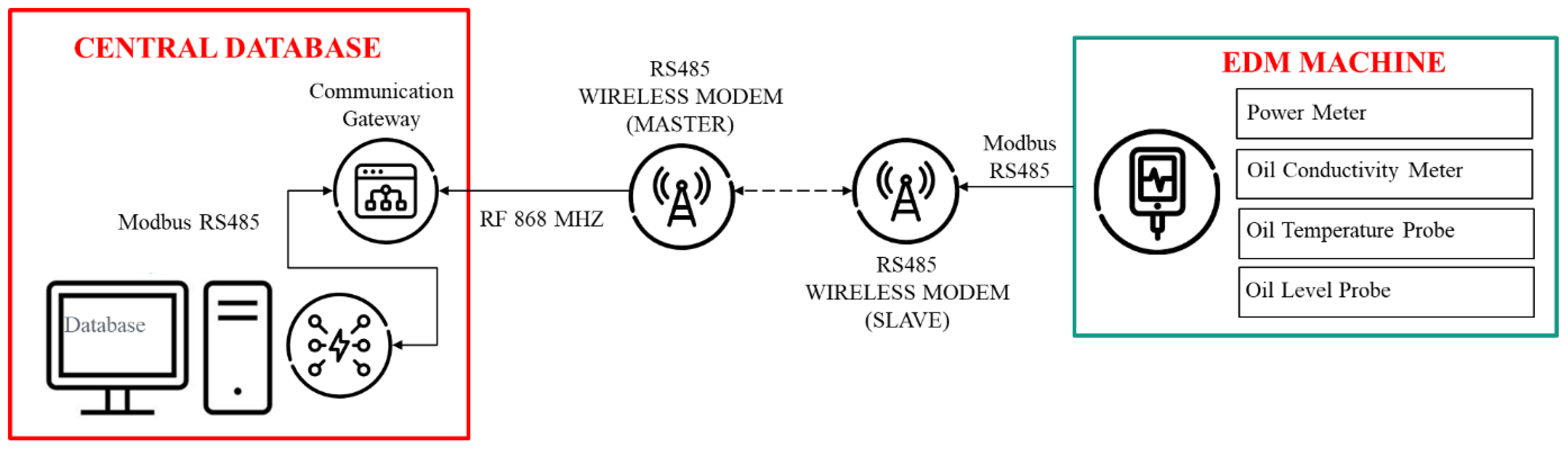

Figure 2, was used to conduct experiments and collect data in a plant owned by Baker Hughes, a company that operates worldwide in the energy sector. The machine has been equipped with Modbus capable energy meter, used for acquiring energy consumption data. The current was recorded using Class 1, 100A:5A open-core clamp-on current transformers. The open-core design enables easy installation by clamping around the power cables without the need for disconnection or interruption of the power supply. The schematics in the

Figure 3 shows the data collection process using RS485 Modbus protocol wirelessly over WiFi.

From the schematics it can be seen that the machine, as shown, is fitted with power meter, oil conductivity meter, oil temperature probe and oil level probe. However, for this study, we will only discuss the results from the power meter and PLC data. This information is first sent to a WiFi modem using the RS485 protocol which is then transmitted to another control or master WiFi modem which receives it and sends it to a Communication Gateway. The Communication Gateway is located in the central database cluster which consists of a locally hosted database which stores all information coming from the production machines, which is useful for controlling the overall performance of all the plants and comparing the relative efficiency of the installed machines. In this study, three sets of experiments were performed to determine the optimal setup for the process. Their setup, analysis, and results are presented in the following sections.

3. Experiment & Setup

3.1. Preliminary Experiment

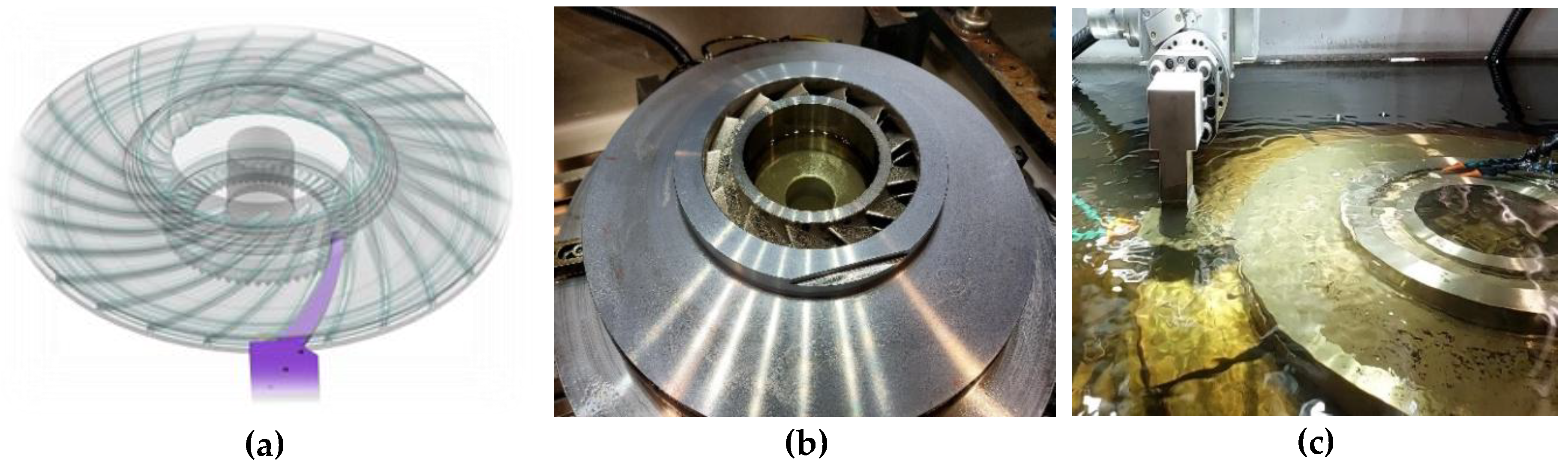

The first experiment was an in-depth exploration of the energy consumption profile of the target EDM machine through a series of cutting tests with production electrodes. This experiment examined the machining process during the roughing stage of the impeller vane creation, as shown in

Figure 4.

A single-electrode geometry featuring an impeller vane was employed, and four different combinations of parameters were tested. It is important to note that these combinations of parameters are provided by the machine manufacturer as presets with the possibility to change only few parameters like the pulse current. The preset and pulse current setting used in this experiment is given in the

Table 1 and

Table 2.

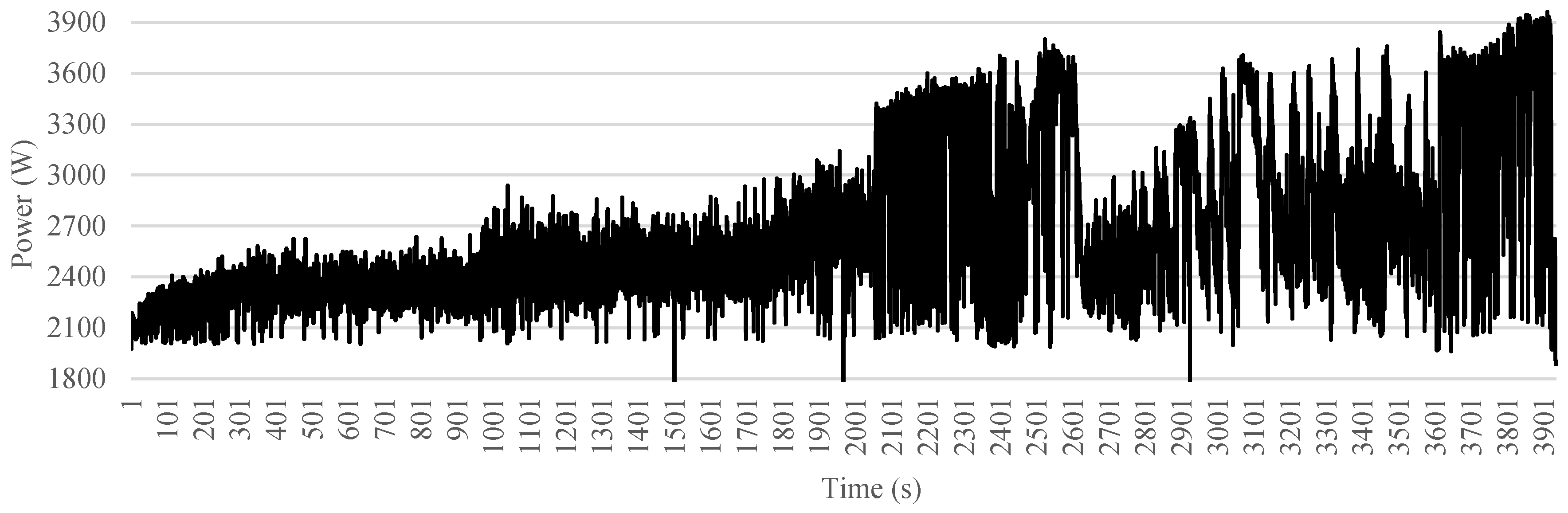

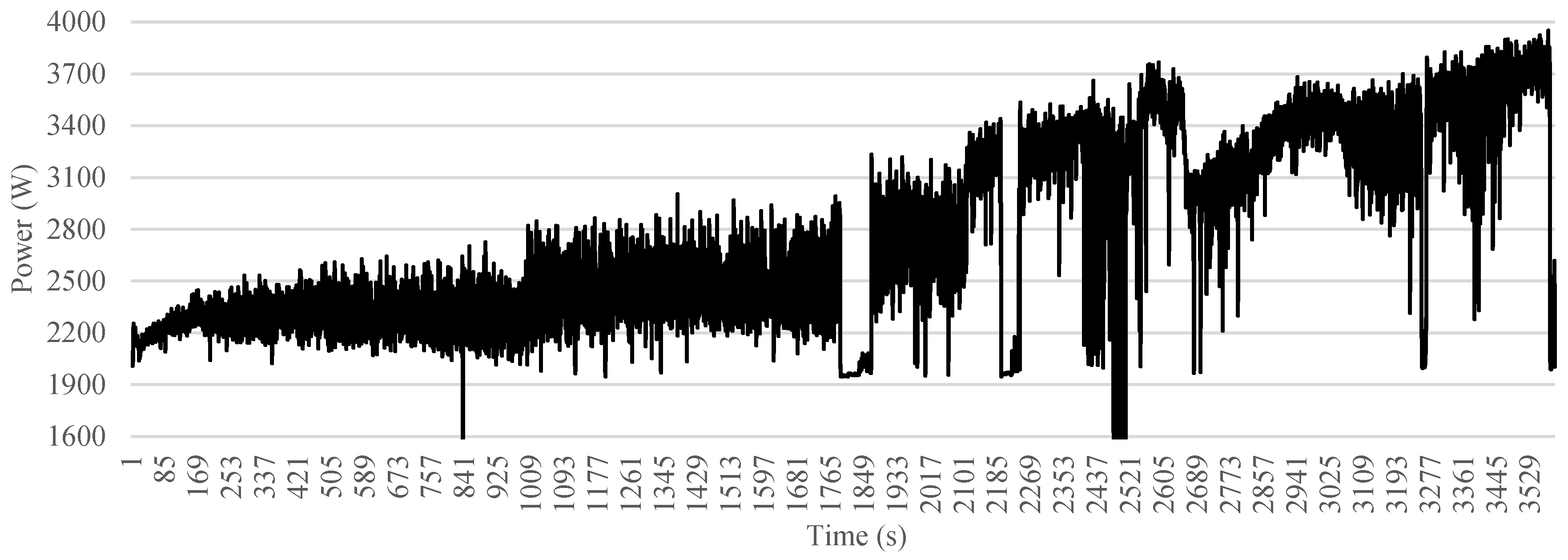

Before the 4 tests from

Table 1 were performed, base energy consumption of the EDM machine during idle condition was measured and after each test, the total time, mean machining power, total energy, energy consumed by refrigeration unit and fixed spark current was recorded. The plots of total system power vs time are shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 for all 4 test cases.

Upon analysing the results seen in

Table 3, it became evident that Test 3, which used the preset “Low Tool Wear, 100A,” was the most energy-efficient and time-effective setting among all tests. This test achieved the shortest machining time of approximately 3716s and consumed the least amount of total energy, 10220.4 kJ. Furthermore, this preset recorded the highest spark current value of 28.91 A, indicating a more aggressive electrical discharge rate. Despite the higher current, the overall system efficiency was enhanced, as indicated by the lowest energy-per-second ratio among all tests. This suggests that a higher pulse current, when optimised correctly, can result in faster machining without significantly increasing the energy costs.

In contrast, Test 1, corresponding to the “Low Tool Wear, 80A” preset, was the least efficient of the four. It had the longest machining time of approximately 4303s and consumed the highest total energy of 11523.6 kJ. Although the spark current was considerably lower at 18.19 A, the longer operational time offset any potential energy savings, leading to an overall reduced efficiency. Notably, the refrigeration energy consumption in this case was also the highest, indicating longer support system usage owing to the extended machining duration.

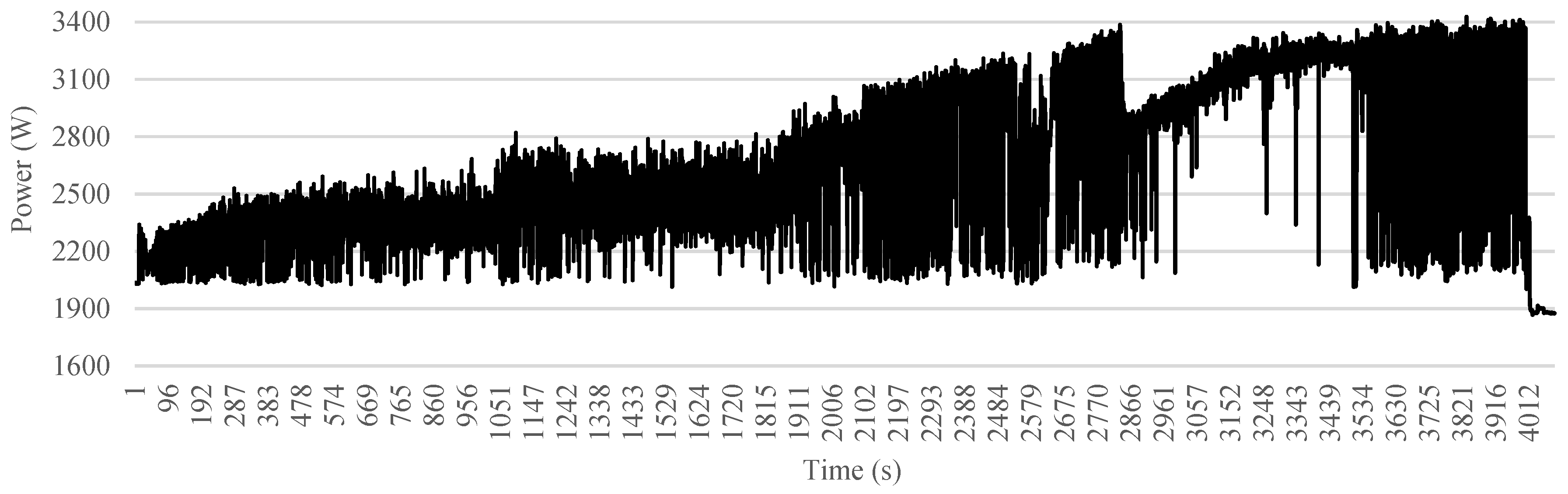

Tests 2 and 4, which used the “High MRR” presets at 100A and 80A respectively, showed similar performance. Their machining times and total energy consumption figures were slightly higher than those of Test 3 but lower than those of Test 1. Their energy efficiency (measured in joule per second of machining time) remained relatively constant at approximately 2676.24 – 2673.36 J/s, further highlighting that small differences in machining duration can significantly affect overall energy usage. This can also be seen in a detailed analysis of last 100 seconds of manufacturing cycle, when the power graph is normalised and overlapped with other types of presets, reported in

Figure 9. Power consumption of the 4 tests.

The energy consumed by the refrigeration unit in all tests was substantial, accounting for more than the energy used in actual machining. However, Test 3 again stood out, with the lowest refrigeration energy demand (11148.8 kJ), likely due to the reduced overall operation time. This reinforces the importance of minimising the machining duration, not only for power savings at the electrode but also for reducing the energy draw from auxiliary systems that could constitute a significant share of the energy consumed.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the preset of Test 3 (Low Tool Wear, 100A) offers the best compromise between machining speed and energy efficiency. It outperformed the other presets in every metric considered—shortest machining time, lowest total energy, and highest energy efficiency—making it the most optimal choice for applications in which tool wear is manageable. However, Test 1 (Low Tool Wear, 80A) is less favourable because of its longer machining time and higher total energy cost, despite its conservative current setting.

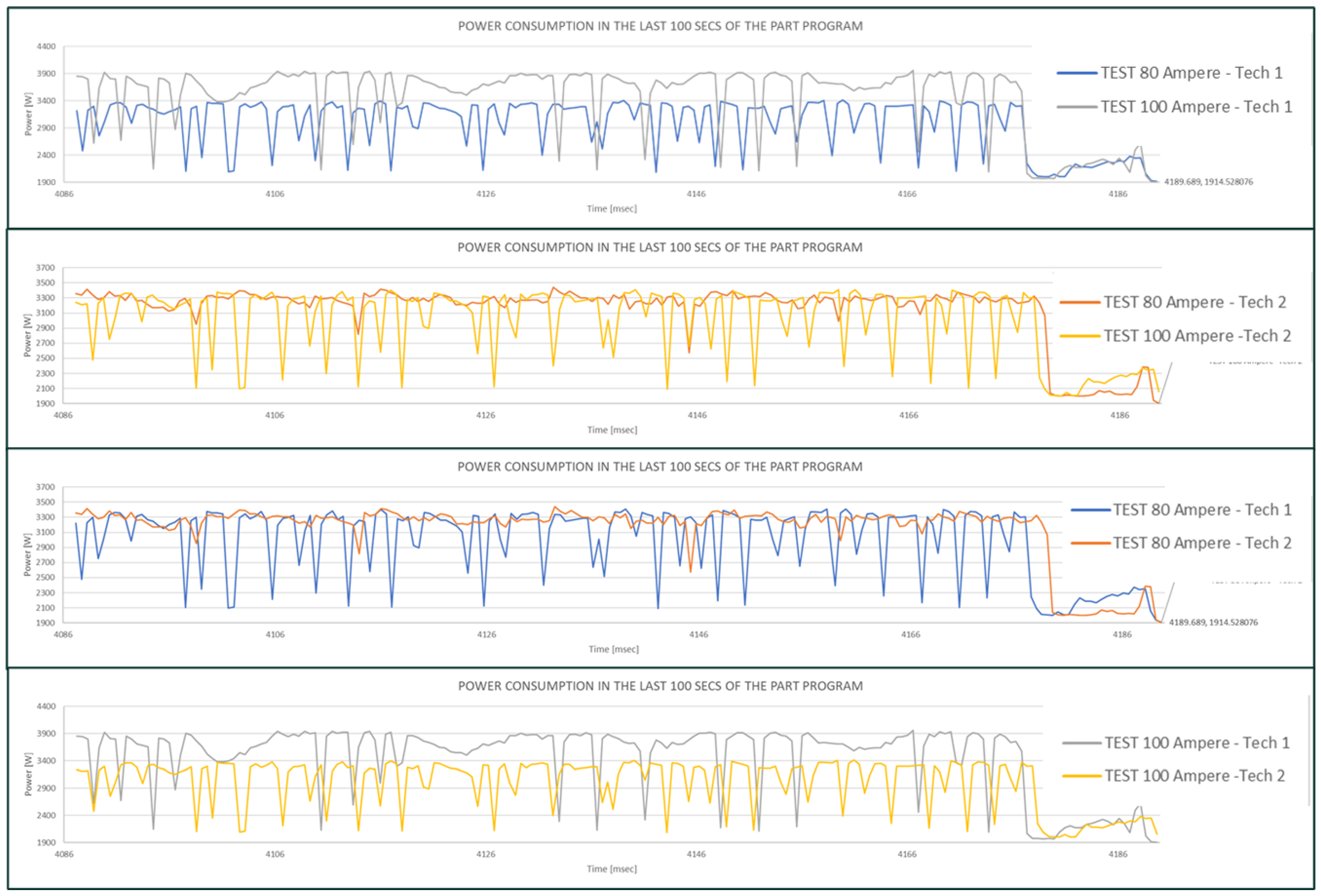

3.2. Standardised Electrode Shape Experiment

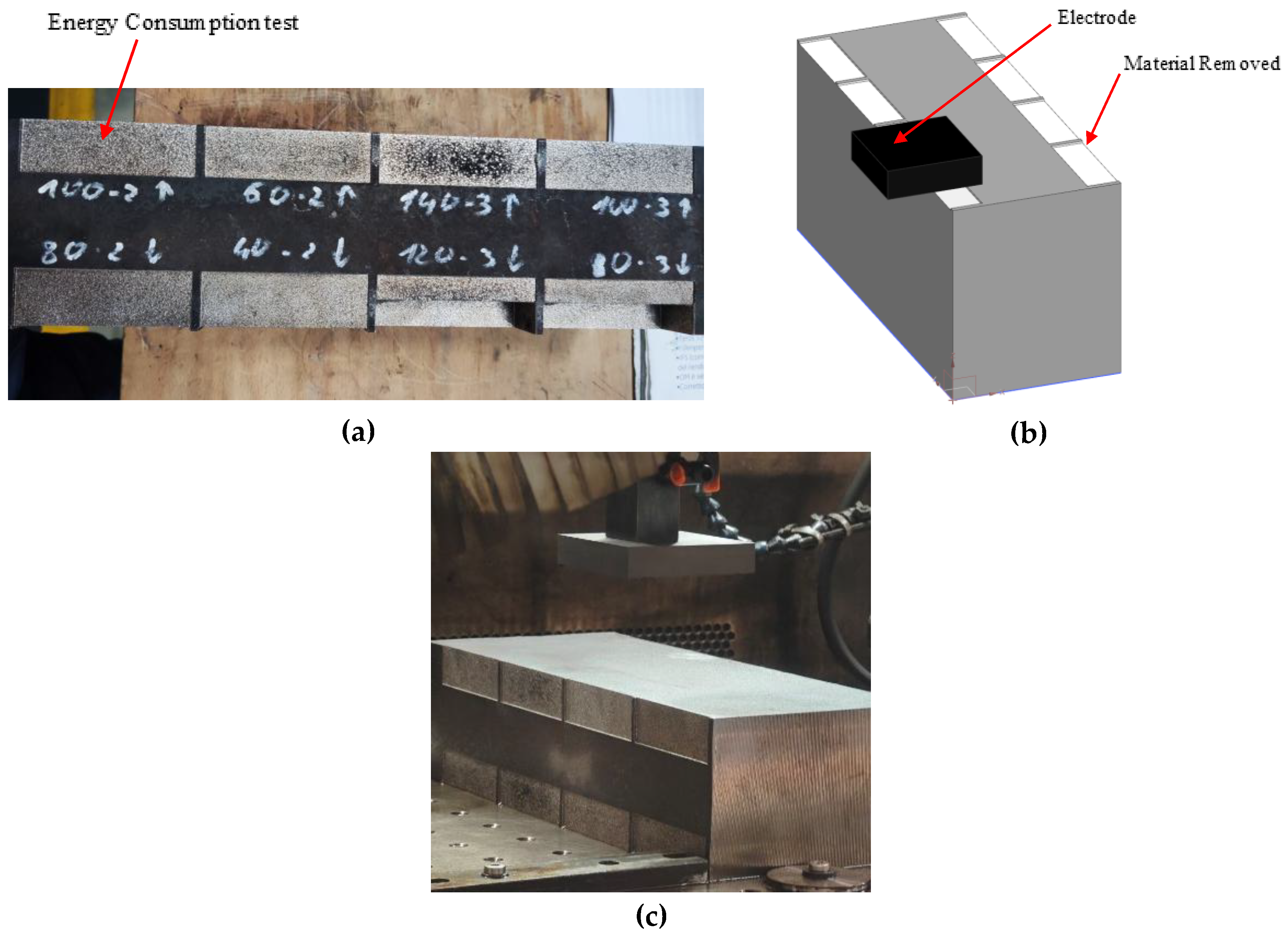

The results obtained from the initial experiment point out the optimal solution for the impeller case study; however, the complex geometry of the electrode introduced significant challenges concerning repeatability and reproducibility of this solution. The variability in electrode wear patterns, alterations in flushing fluid dynamics, and unpredictability of debris formation collectively influenced the total energy consumption and degradation characteristics of the electrode over the duration of machining. To address these uncertainties, a second experiment was conducted using a simplified electrode geometry. Specifically, a standardized graphite electrode was fabricated as a rectangular cuboid measuring 90 mm × 90 mm × 20 mm (length × breadth × height), as reported in

Figure 10.

A comprehensive set of 18 trials was performed, systematically varying the EDM parameters, including the discharge current, pulse duration, and other inherent machine “technology” settings or presets. Specifically, in this experiment, another preset was used in addition to presets 1 and 2 used in previous experiments. All 3 presets and their specifications are given in

Table 4 and

Table 5. Each experimental run involved the erosion of a consistent metal volume of 5,400 mm

3, defined by the intended contact area dimensions of 90 mm × 30 mm × 2 mm, as shown in

Figure 11.

During these tests, the power sensors recorded the electrical load of the EDM machine, enabling the calculation of total energy consumed for each 5,400 mm3 removal. From this, the SEC for material removal was computed as a key metric for sustainability. In parallel, the graphite tool was closely examined for evaluating electrode wear after each test by measuring the electrode before and after machining.

From the initial 18 trials, trends have been highlighted. The results are reported in

Table 6. Under Test ID column, the test cases are named by the current value and type of preset used. For example, for TEST 140-3 the current used was 140 amperes, and the preset used was Tech 3. The data showed that aggressive EDM parameters which increased the Material Removal Rate (MRR) dramatically shortened the machining time for a given volume, while more conservative settings (designed to minimize tool wear) led to much longer erosion times. The faster the removal, the lower the total energy consumed in completing the cut, even if the instantaneous power draw was higher. In fact, it was found that “higher machining time” and hence a slower cutting, led to higher overall energy consumption, whereas a higher MRR resulted in a lower specific energy consumption. This outcome was consistent across the trials and was a crucial insight, indicating that any strategy to reduce machining time (within practical limits) would directly save energy per part. A likely reason is that an EDM machine has certain fixed overhead power usages (cooling systems, flushing pumps, etc.), so a prolonged process wastes a lot of energy on those overheads.

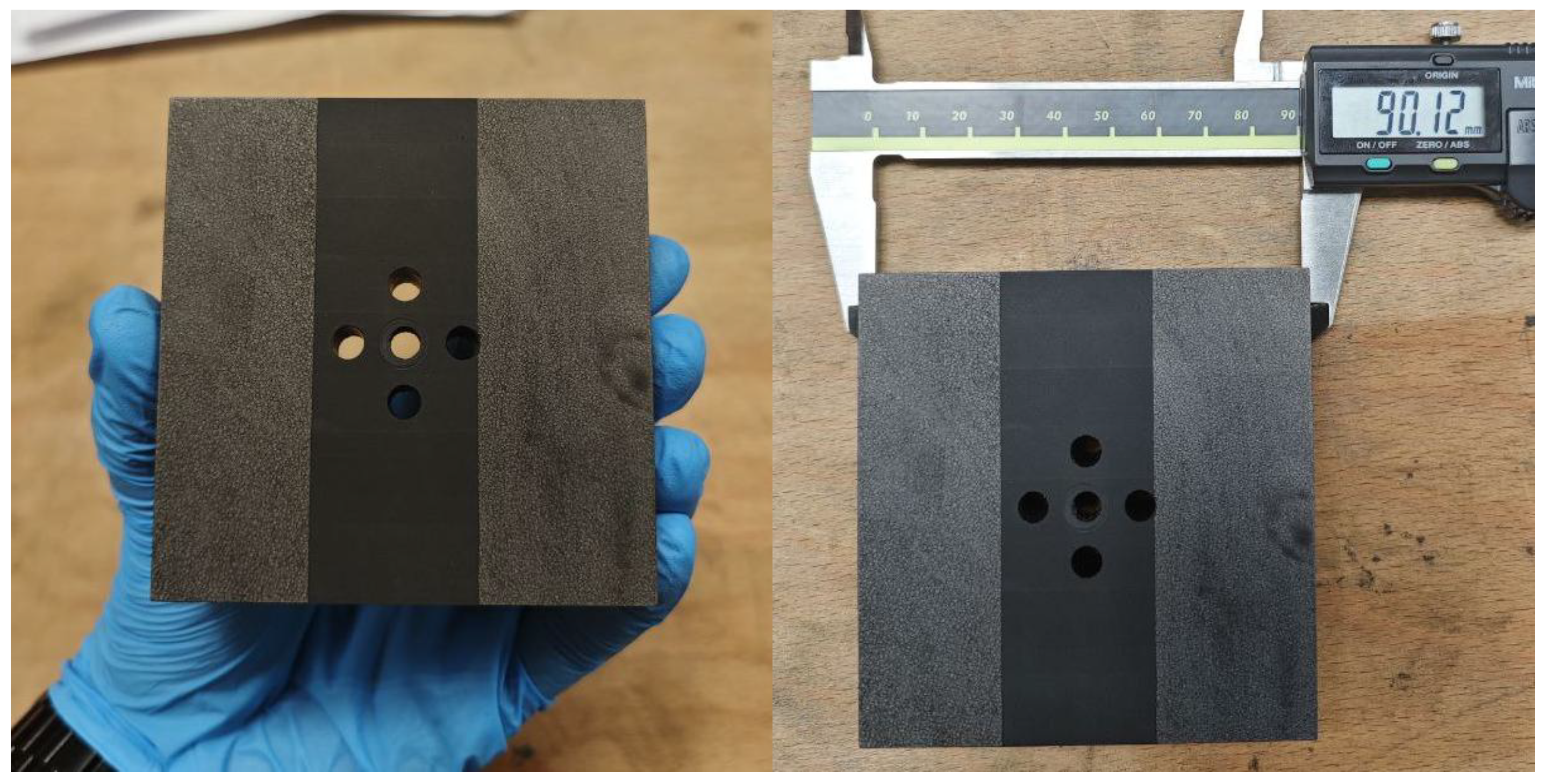

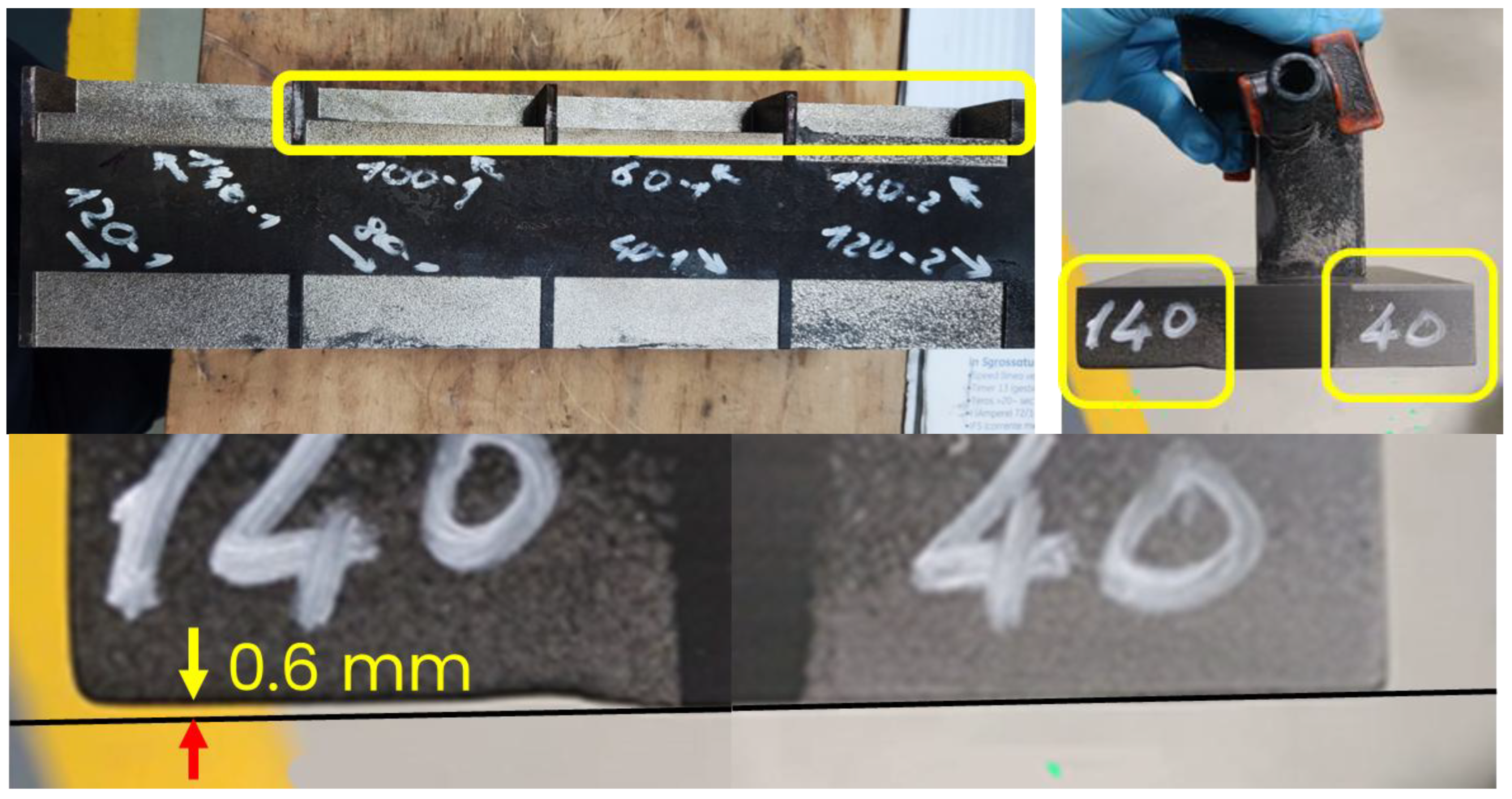

An electrode wear analysis was also performed using the two extreme test cases from experiment 2 in

Table 6 (Tech 3 was ignored as in most cases the results were not optimum). Comparing Test 1 at a higher current of 140 Amperes (Technology 1) and Test 2 at a much lower current of 40 Amperes (Technology 2), it is possible to highlight that both tests were aimed at removing an identical volume, approximately 129,600 mm

3, from the workpiece, as reported in

Figure 12. However, notable differences emerged between the two tests in terms of erosion time, achieved volume removal, and electrode tool wear.

Test 1 (140 A) was conducted aggressively, prioritising high material removal rates, and the machining was completed in approximately 210 min. However, the actual volume removed was marginally below the intended target, specifically 127,980 mm

3, reflecting a shortfall of approximately -1.25%. Close-up images provided clearly show measurable electrode wear—approximately 0.6 mm of material loss on the graphite electrode seen in

Figure 12. Owing to this wear, the electrode’s ability to achieve the full intended machining depth was slightly compromised. Therefore, a time adjustment was calculated to account for the shortfall, adding an additional 2.6 min (1.25%) of machining time for a corrected total duration of 212.6 min, had the full volume been achieved.

Test 2, which employed a more conservative approach at 40 A (Technology 2), demonstrated a drastically different scenario. This low-current method significantly minimised electrode wear, so effectively that the removed volume matched precisely the expected 129,600 mm3 without any measurable deviation. However, this advantage came with an exceedingly prolonged erosion time of 2010 min (over 33 h), highlighting the practical trade-off between electrode longevity and productivity.

4. Conclusions

This research rigorously investigated the correlation between energy consumption and electrode wear in Die Sinking Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM), addressing a notable gap in current literature concerning comprehensive empirical evaluations of real-time energy usage integrated with precise electrode wear assessments. While EDM has long been recognized as a crucial process for machining intricate geometries in challenging materials, prior studies have typically focused either solely on theoretical energy modelling or isolated analyses of individual machining parameters, neglecting a holistic examination of the combined influences of process settings, auxiliary system loads, and electrode deterioration.

The novelty of the present study lies in its methodical integration of empirical data collection techniques and robust analytical methodologies, facilitating a holistic appraisal of EDM operational dynamics. Hence, by explicitly considering auxiliary energy demands, particularly from refrigeration systems, this study provided a comprehensive portrayal of the energy profile during EDM operations, distinctly advancing beyond the conventional fragmented analytical approaches prevalent in the existing literature.

The experimental outcomes yielded significant insights, particularly highlighting that optimised high-current EDM parameters substantially improved both machining productivity and energy efficiency, countering the prevalent notion that aggressive discharge settings invariably lead to undesirable electrode wear. Specifically, comparative analyses between high-current (140 A) aggressive machining and conservative low-current (40 A) settings highlighted a critical trade-off. The conservative parameters successfully minimised electrode wear to negligible extents but at the cost of drastically increased machining times and correspondingly higher cumulative energy consumptions. In contrast, the strategically optimised high-current setting notably reduced the overall machining time by up to an order of magnitude while maintaining acceptable electrode wear levels. Quantitative metrics reinforced this finding, demonstrating a lower Specific Energy Consumption (SEC), a pivotal sustainability indicator, under high-current, optimised conditions.

These results have substantial implications for advanced manufacturing sectors, particularly the aerospace, automotive, and precision tooling industries, where operational efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and sustainability are paramount. By empirically substantiating the viability and benefits of employing aggressive EDM settings, this study provides practical guidelines for process engineers to significantly enhance productivity and energy efficiency without incurring prohibitive electrode wear or environmental penalties.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable publicly due to data privacy and NDA clause of Baker Hughes SRL company data privacy policy. Data can be provided to research paper reviewers upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Baker Hughes SLR, Florence, Italy, for providing access to the EDM machinery, graphite electrodes, and technical resources required for conducting the experiments. The valuable contribution of man-hours and in-kind support from the engineering team at Baker Hughes played a critical role in the successful execution of this research. Their collaboration and technical assistance are sincerely appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Peças, P.; Henriques, E. Intrinsic innovations of die sinking electrical discharge machining technology: Estimation of its impact. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2009, 44, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N. Die-sinking EDM performance under the effect of tool designs and tool materials. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM) 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrocco, V.; Modica, F.; Fassi, I.; Bianchi, G. Energetic consumption modeling of micro-EDM process. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2017, 93, 1843–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanjilul, M.; Kumar, A.S. Die-sinking of super dielectric based electrical discharge machining using 3D printed electrodes. Procedia CIRP 2020, 95, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujiyulianto, E.; Suyitno. Effect of pulse current in manufacturing of cardiovascular stent using EDM die-sinking. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2021, 112, 3031–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, D.; Wu, B.; Zhang, Y. Energy Consumption Modeling for EDM Based on Material Removal Rate. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 173267–173275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrocco, V.; Modica, F.; Fassi, I.; Bianchi, G. Energetic consumption modeling of micro-EDM process. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2017, 93, 1843–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tristo, G.; Bissacco, G.; Lebar, A.; Valentinčič, J. Real time power consumption monitoring for energy efficiency analysis in micro EDM milling. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2015, 78, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.N.; et al. A new method to efficiently control energy use in Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM). In Technologies for Optical Countermeasures XVIII and High-Power Lasers: Technology and Systems, Platforms, Effects V; Titterton, D.H., Grasso, R.J., Richardson, M.A., Bohn, W.L., Ackermann, H., Eds.; SPIE, 2021; p. 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N. Machining and wear rates in EDM of D2 steel: A comparative study of electrode designs and materials. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 30, 1978–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; et al. Regulating cutting fluid parameters for optimal energy and economic performance: Methods for efficient and Low-Energy electrical machining. Energy Convers Manag 2024, 314, 118707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maradia, U.; Knaak, R.; Busco, W.D.; Boccadoro, M.; Wegener, K. A strategy for low electrode wear in meso–micro-EDM. Precis Eng 2015, 42, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.T.; et al. Optimization design for die-sinking EDM process parameters employing effective intelligent method. Cogent Eng 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, W.; et al. Optimization of process parameters and performance for machining Inconel 718 in renewable dielectrics. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2023, 79, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujiyulianto, E.; Suyitno. Effect of pulse current in manufacturing of cardiovascular stent using EDM die-sinking. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2021, 112, 3031–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezoudj, M.; Belloufi, A.; Abdelkrim, M. Experimental investigation on the effect of machining parameters in electric discharge machining using aisi 1095- treated steel. International Journal of Modern Manufacturing Technologies 2019, XI, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chidambaram, V.; Ramasamy, M.; Saravanan, N.K.; Devan, V. Investigations of process parameters on surface finish of aluminium component produced by die sink electric discharge machining process. Indian Journal of Engineering and Materials Sciences 2024, 31, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Khan, M.A.R.; Kadirgama, K.; Noor, M.M.; Bakar, R.A. Modeling of material removal on machining of Ti-6Al-4V through EDM using copper tungsten electrode and positive polarity. World Acad Sci Eng Technol 2010, 71, 576–581. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.K.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, J. Desirability approach to control machining parameters during die-sinking edm of inconel-686. Academic Journal of Manufacturing Engineering 2022, 20, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).