1. Introduction

Speech Sound Disorder (SSD) refers to difficulties producing and using speech sounds and speech segments, resulting in reduced accuracy and clarity of speech production. They are the most prevalent of all childhood communication difficulties [

1] affecting 3.4%-5.6% of pre-school aged children [

2] and comprising more than 70% of a Speech-Language Pathologist’s (S-LP) caseload [

3]. Children with SSD are more likely to experience adverse social, educational and psychological outcomes than children without SSD [

4,

5]. These difficulties may further limit employment opportunities throughout the lifespan [

6]. Minimizing the impact of SSD is contingent on providing accurate diagnosis to direct intervention approaches.

The causes of SSD can be organic or functional; organic SSDs arise from an underlying structural (e.g., cleft palate), motor/neurological or sensory/perceptual cause; while functional SSDs, which are more prevalent [

5], are idiopathic and include articulation and phonological disorders [

7]. Diagnosis of functional SSDs seeks to identify the underlying contribution of speech difficulties. For example, identifying whether the child is having difficulties learning the linguistic-phonological rules of the target language (i.e., a phonological impairment) or/and difficulties with the motor aspects of speech production. The diagnosis of SSD, however, is challenging due to the nature of SSDs and the limitations of current clinical practices [

8,

9,

10]. McCabe, Korkalainen & Thomas [

9] highlight that the “overlap between the symptoms of different disorders with the same speech features … from multiple different breakdowns…” complicates SSD, while Littlejohn and Maas [

8] note that diagnosis is impacted by a “poor understanding of, and limited focus on the underlying impairment(s)” (p. 2).

As part of the assessment process S-LPs are encouraged to conduct a comprehensive case history; assessment of oral structures and hearing function; an error analysis from a connected speech sample to identify a child’s phonetic inventory and phonological error patterns or processes; as well as obtain measures of phonological mean length of utterance and quantify intelligibility [

11]. In practice, however, time and ease of use are key factors influencing clinical decisions [

12], with S-LPs routinely using standardized single-word naming tasks to evaluate speech sound inventory and error patterns [

12,

13]. Measures of phoneme accuracy within the single-word naming tests, including percent consonant correct (PCC), percent vowels correct (PVC), and percent phonemes correct (PPC), are frequently used to determine the presence and severity of SSDs [

14].

The determination of speech sound error patterns typically relies on auditory-perceptual analysis using International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) transcription [

14,

15]. While this is a fundamental part of diagnosis, using auditory-perceptual assessment alone is limiting [

16,

17,

18], and there is no gold standard validation of perceptual measures that can discriminate SSD from TD speech. Auditory perceptual assessments do not allow clinicians to determine the contribution of speech motor control to the production difficulties of a child [

19]. Further, the reliance on single-word assessment tools, framed predominantly on linguistic models of speech production, is problematic for differential diagnosis of SSD because these tools tend to focus on investigating phonological deficits [

20], as opposed to the speech movement patterns associated with underlying constraints at the level of speech motor control.

McCauley and Strand’s [

21] 2008 review of standardized tests that evaluate speech motor performance of children concluded that “clinicians are in the position of having no tests that can be considered well developed for use with children with motor speech disorders” (p. 89). While new standardized assessment tools have been developed since this review, for example, the Dynamic Evaluation of Motor Speech Skill (DEMSS) [

22], a recent review of assessment and intervention approaches for SSD identified 37 published assessment tools for SSD with the majority focusing on specific skills and only four assessing combined articulatory, phonetic and motor based development [

4]. In their 2024 review of tools and approaches supporting diagnosis of childhood motor speech disorders, McCabe, Korkalainen and Thomas [

9] state, “there are not yet validated tools for comprehensively assessing all speech production processes” (p. 9).

A tool recently developed to measure speech motor control is the Motor Speech Hierarchy - Probe Words (MSH-PW)[

23]. The MSH [

26] comprises seven stages that reflect the hierarchical (i.e., increasing motor complexity) and interactive development of speech motor control: Stage I: Tone: Stage II: Phonatory Control; Stage III: Mandibular Control; Stage IV: Labial-Facial Control; Stage V: Lingual Control; Stage VI: Sequenced Movements and Stage VII: Prosody. The Probe Words (PWs) cover stages III to VI, with 10 words and one phrase, in each stage. The probe words are scored visually and auditorily by observing a child say the target word and judging whether the speech movements look and sound appropriate/inappropriate, based on specific criteria. Criteria for stage III, Mandibular Control are, for example: appropriate jaw range; appropriate jaw control stability; appropriate close-open phase; appropriate voicing transitions; and correct syllable structure. In 2021, Namasivayam and colleagues [

23] reported key measures of validity and reliability of the MSH-PW. Their data indicate high content, construct and criterion-rated validity, as well as high reliability on measures of internal consistency and intra-rater reliability, and moderate agreement on interrater reliability. This validation study, however, did not undertake a fine-grained analysis of individual scoring criteria (e.g., jaw range, jaw control), and the MSH-PW assessment tool was only validated on children aged 3 to 10 years with moderate-to-severe motor speech disorder. Therefore, construct validity in the form of distinguishing between the speech motor skills of TD children and SSD children, and scoring criteria involved in diagnosing impaired speech motor control, has yet to be established for the MSH-PW.

Furthermore, despite perceptual measures being used to judge articulatory control, the gold standard for evaluating speech motor control is based on instrumental analysis. Researchers have long advocated the need to combine perceptual analysis with instrumental analysis of kinematic (i.e., the study of motion: displacement, velocity and acceleration) and acoustic measures [

15,

18,

21]. The use of kinematic analysis of speech has progressed with the development of new video and motion-tracking technologies [

29], including the use of video-based tracking of jaw movements (e.g. [

24]). In recent years, the enormous potential of Machine Learning (ML) in the support of a diagnosis of SSD has been recognized [

25].

Computer vision-based approaches to measuring facial movements offer an objective and well-defined standard for detecting atypical speech patterns [

26,

27] and have demonstrated the potential for detecting facial movements associated with disorders [

27,

28,

29]. While promising, the features used by these systems are not well grounded in the existing clinical understanding of which facial movements are involved in which aspects of speech motor control. As such, the decisions made by these systems lack explicative transparency.

This study focused on the assessment of mandibular control in young 3-year-old children using the MSH-PW. First, we investigated whether MSH-PW mandibular control scores obtained from expert clinicians could distinguish TD children from children diagnosed with a SSD. The aim was to validate the perceptual scoring of MSH-PW as being sensitive to individual differences in speech motor skill at the level of mandibular control, and to identify MSH criteria that could be predictive of disordered mandibular control, relative to TD children. The mandibular stage was chosen based on existing literature that indicates jaw control and stability may be a useful marker for determining SSD subtypes [

30].

Second, we employed a state-of-the-art facial mesh detection and tracking algorithm [

36] to extract measurements of facial movements identified as clinically salient in the assessment of speech motor control from recorded video of children speaking words from the mandibular stage of the MSH-PW. We evaluated how well these extracted facial movement measurements agree with perceptual scores for the jaw range and jaw control criteria of the MSH-PW. We selected these two criteria because clinicians rely predominantly on the child’s facial movements in order to score jaw range and control.

This preliminary study, therefore, sought to answer the following questions:

Q1. Do the MSH-PW criteria, using expert consensus scoring, discriminate TD children from those with SSD? We predicted TD children would score more highly than SSD children in relation to the MSH-PW mandibular control criteria and that mandibular control criteria could be predictive of whether a child was TD or had an SSD.

Q2. Can kinematic measurements derived from automated facial tracking accurately predict expert the consensus perceptual scores of the MSH-PW jaw range and jaw control criteria? We expected good agreement between objective measures obtained from facial tracking and expert clinician judgements of appropriate and inappropriate jaw range and jaw control as indicated by the predictive accuracy in logistic regression classification models with objective measures as predictors and clinician judgements as the outcome.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we report on a preliminary study aimed at exploring the potential of the MSH-PW to discriminate the speech of children with SSD from TD speech, through evaluation of the Stage III: Mandibular Control word set. We aimed to determine, firstly, whether the observations of speech pathologists on five features: appropriate mandibular range, mandibular control/stability, open-close or close-open movements, voicing transitions and syllable structure, could accurately classify children with TD speech from those with an SSD. Secondly, we evaluated the agreement between the subjective visual observations of the consensus scores completed by three S-LPs and those derived through kinematic measurements, extracted from a state-of-the-art facial mesh detection and tracking algorithm. These research questions were selected to inform the development of norms for the MSH-PW for the purpose of diagnosing impaired speech motor control in children and evaluate the feasibility of supporting S-LPs with objectively acquired measurements of motor speech control, framed within the MSH-PW scoring criteria. Each research aim will be discussed in turn.

4.1. Classification of Children Based on Perceptual Scoring

The results of this study found there were significant differences in MSH-PW jaw range, voicing transitions and mandibular total score between children with TD speech and those with SSD when scored perceptually by S-LPs. Discrimination analysis indicated a significant correlation between perceptually scored MSH-PW mandibular criteria and diagnostic class as determined by a battery of diagnostic tools used in current clinical practice. This suggests perceptual scoring of the MSH-PW mandibular subtest can discriminate between children with TD speech and those with SSD, with potential for the MSH-PW to be used by S-LPs in diagnosing impaired speech motor control.

The finding of no significant difference in jaw control contrasts with existing literature that has established the significance of jaw control and stability in speech sound production [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. Development of jaw control is a key feature of speech development. For example, jaw movement velocities are slower and more variable in young children [

54] with children with typical development refining multidimensional jaw movements by around 6-8 years of age [

55,

56]. Wilson and Nip [

55] highlighted the importance of jaw control and stability in supporting lip and tongue movements, noting its involvement in nearly all articulatory positions [

53]. Jaw control has also been identified as a feature of SSD. For example, Mogren and colleagues found children with SSD had larger lateral jaw movements than children with TD speech [

53]. Similarly, Terband et al. [

54] identified clear deviances in lateral jaw movement within their SSD group compared to their sample of TD participants. Reasons for the contrast in these findings with this current study were considered.

Firstly, previous studies examining motor control tend to feature participants with clearly identified motor speech disorders (e.g., [

55]) , including childhood apraxia of speech (e.g., [

56]) and/or may differentiate between various subtypes of SSD. For example, Terband et al. [

54] differentiated children with phonetic articulation disorder, phonological disorder and childhood apraxia of speech. Participants in the SSD group of this current study had not been identified as having SSD prior to their participation in the study (while some parents expressed uncertainty over whether their child’s speech was developing within age expectation, concerns had not been sufficient to seek S-LP assessment). As such, it is possible participants in the SSD group demonstrated more mild SSD features and/or that children within this group primarily had difficulties at the phonological level, rather than motor-based difficulties. This suggestion is supported by Terband et al.’s finding that a participant with a phonetic articulation disorder had “very normal values” on lateral jaw movement. As such, is it plausible that the results of this current study may be reflective of the characteristics of participants in the SSD group. Further analysis of children with diagnosed motor speech difficulties may yield classification differences across a wider range of MSH-PW criteria. Secondly, the mandibular word set items were intentionally selected to include only bilabial consonants and low vowels with targets achieved through open-close (e.g., Um), close-open (e.g., Ba), close-open-close (e.g., Map) and close-open-close-open (e.g., Papa) jaw movements. With the vowel target determining jaw height, differences in PVC and PPC between the TD and SSD groups indicate there are differences in speech production accuracy from an auditory perceptual perspective that may not be evident in perceptual movement analysis over the ten mandibular target items. Furthermore, difficulties in jaw control, specifically, may not be evident until motor complexity increases in the higher MSH-PW stages. Further investigations are required to determine the impact on jaw control as young children are required to integrate jaw stability with labial facial and lingual movements, and sequencing these movements in multisyllabic and phrase level speech.

4.2. Agreement between Perceptual Scoring and Kinematic Measures

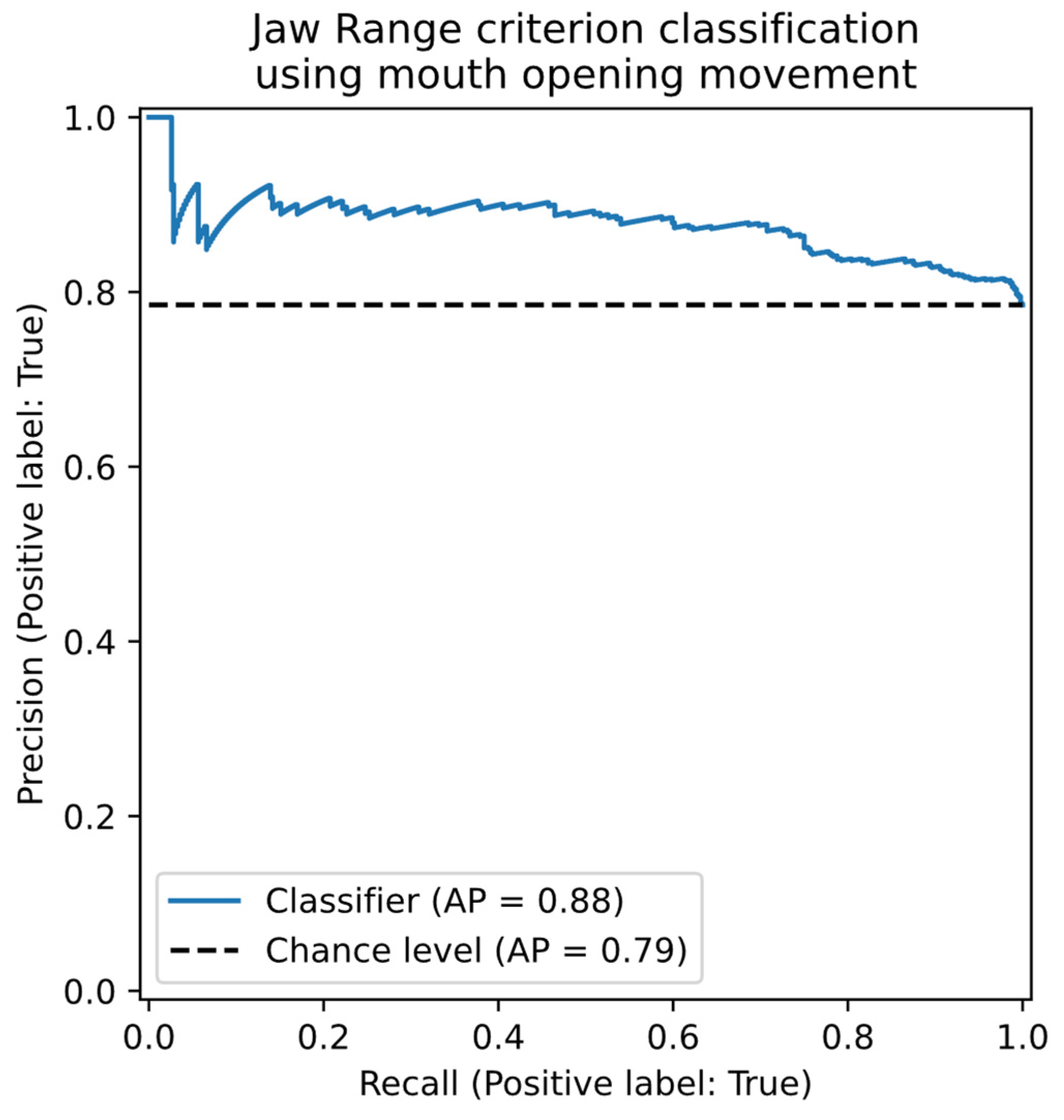

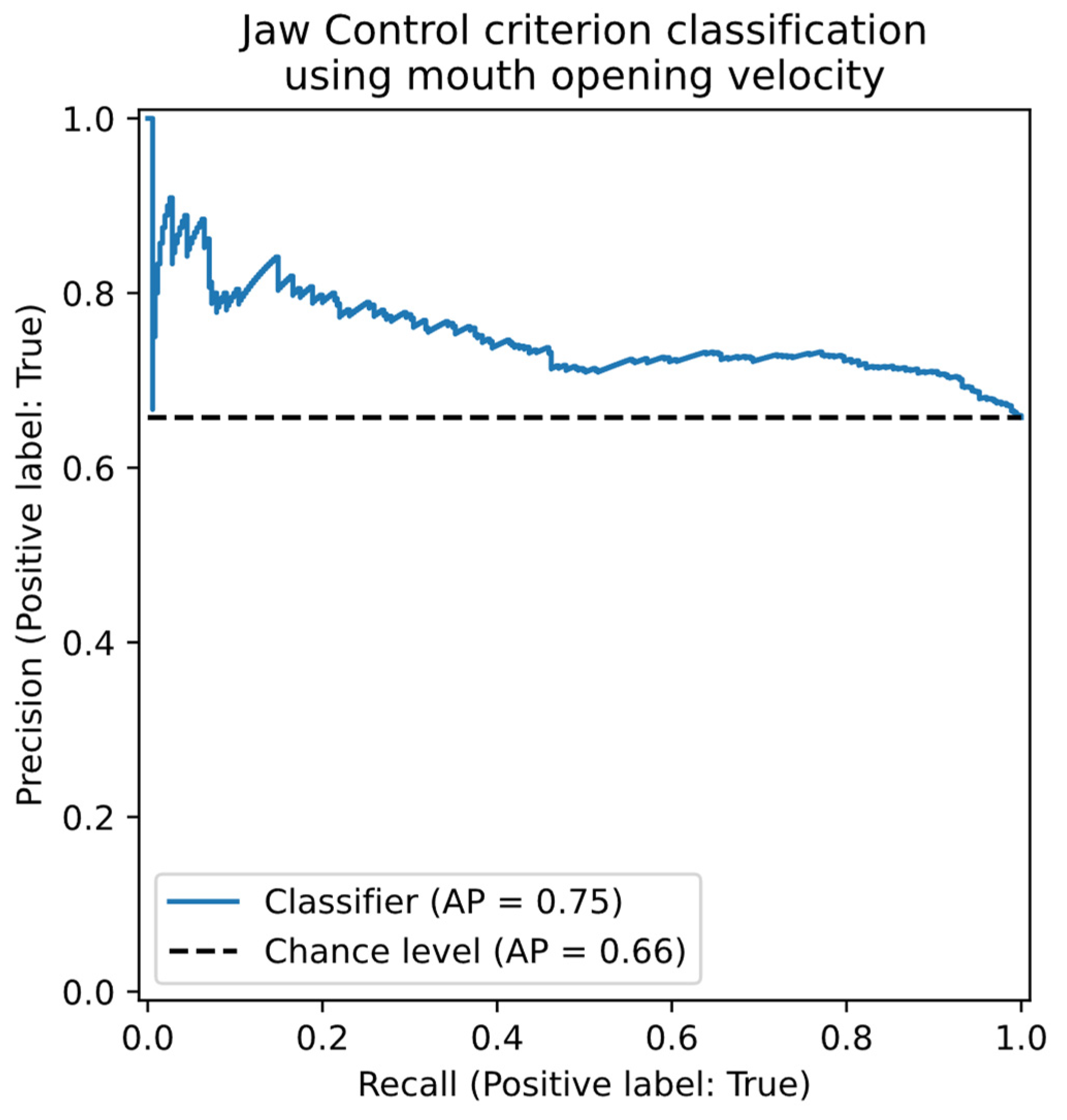

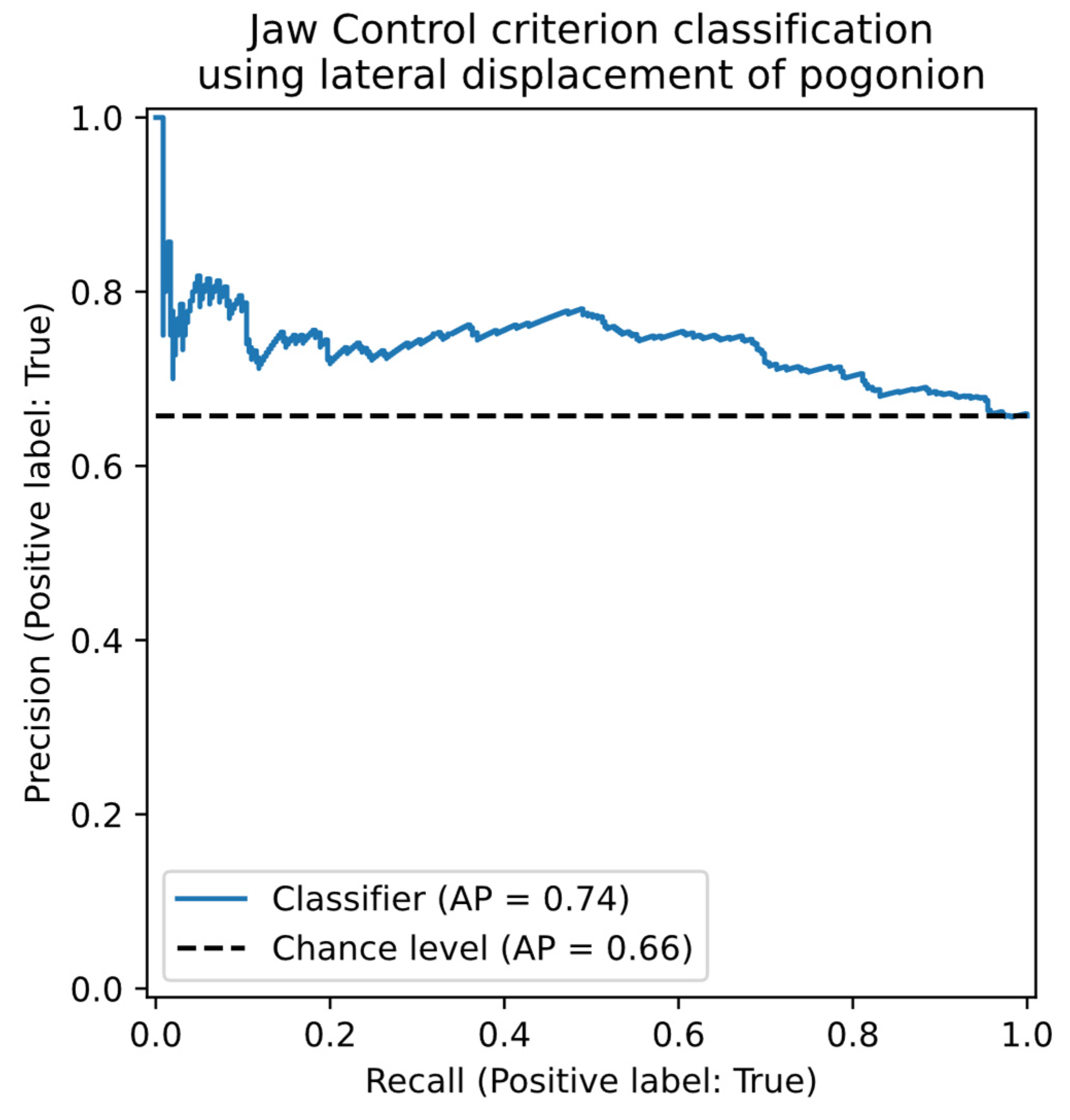

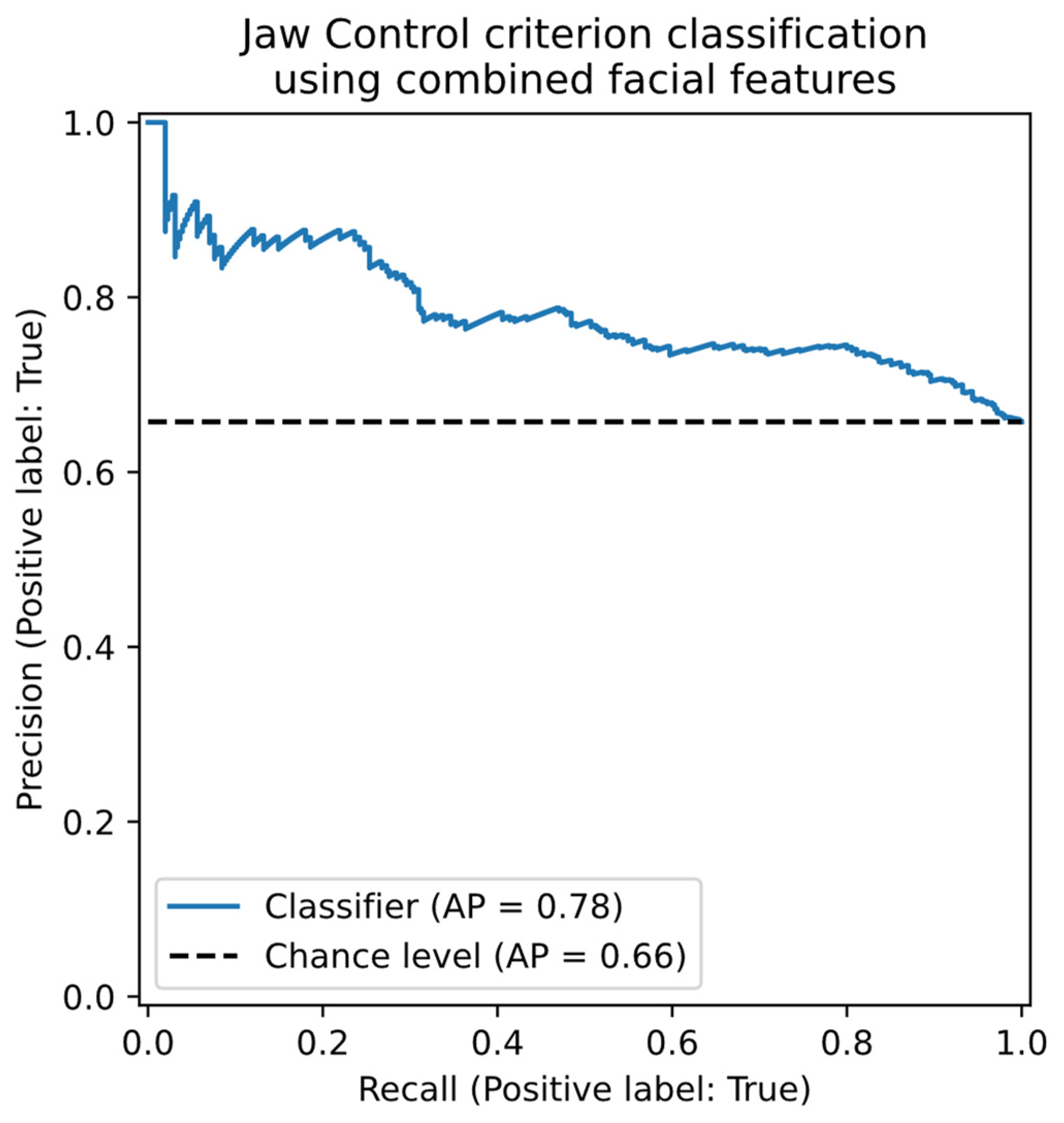

Our second research question sought to explore the agreement between the perceptual scores of jaw range with the kinematic measure labelled mouth opening; and jaw control with two kinematic measures labelled mouth opening velocity and lateral movement of the pogonion. We found good agreement for both jaw range and jaw control.

The rating of jaw range required consensus raters make a binary judgement of appropriate or inappropriate for age, where a judgement of inappropriate was given for movements considered restricted or over extended, as defined for each vowel height position, for each word, in the MSH-PW scoring manual. Our preliminary results suggest the objective measure of mouth opening could be used to support speech pathologists in their assessment of jaw range.

It is proposed that the agreement between the consensus raters with the mouth opening measurement resulted from their already established internal representation of jaw height, and that this representation was aligned with the objective kinematic measures, resulting in good agreement. This proposal is based on the knowledge that the consensus scorers are familiar with the vowel quadrilateral that describe jaw and tongue positions, as well as an established body of literature that specifies jaw height adjustments contribute to the production of vowels [

57,

58]. It is, therefore, conceivable that the raters utilized this knowledge, along with their experience, to inform their decision making. That is, when a child produced a vowel error, the associated jaw height position could be evaluated as too high or too low, with respect to the intended target.

Similarly, there was good agreement between the consensus scores and kinematic measures for jaw control. The rating of jaw control required the consensus raters to make a binary judgement of appropriate or inappropriate for age, based on velocity and midline or anterior-posterior stability of the jaw. The finding that the combined measures showed greater agreement than the individual measure is likely reflective of the multidimensionality of the jaw control criterion and jaw control movements in general. Multidimensionality is an essential feature of jaw movement and the integration and balancing of vertical, lateral, and rotational movements with precise timing and velocity enable speakers to adapt to the acoustic and articulatory demands of different phonemes and provide a dynamic scaffold for tongue and lip movements [

52,

58,

59,

60,61]. As outlined, the rating for jaw control is based on several criteria reflective of controlled, smooth speech movements within the vertical plane. The velocity of mouth opening and lateral displacement of the pogonion are both key metrics of jaw control and the interplay of each movement contributes to the production of fluent, intelligible speech.

Agreement between consensus scorers and kinematic measurements derived from automated facial tracking was likely aided by the high level of experience the consensus scorers had in the assessment of speech motor control. Further research should explore the level of agreement in ratings of jaw range and jaw control with S-LPs who have less experience in the assessment of speech motor control; and determine whether kinematic measures can support the clinical judgements of S-LPs of differing levels of experience when scoring jaw range and jaw control criterion of the MSH-PW.

4.3. Clinical Application

Perceptual, single word speech assessments such as the GFTA-3 are a critical component in the assessment of children’s speech and the diagnosis of SSD [

12,

49], providing timely and convenient measures of speech development and accuracy. As highlighted, there are limitations with current perceptual assessments, including their focus on identifying phonological deficits, rather than also assessing for underlying speech motor control difficulties [

50]. The MSH-PW was designed to measure inappropriate speech motor control through the perceptual visual and auditory assessment of single word productions. The findings of this preliminary study of the Stage III: Mandibular Control level of the MSH-PW indicate the assessment tool can identify perceptual differences in the appropriateness of jaw range and voicing transitions between children with TD speech compared to those with SSD, and support further research into the additional levels of the MSH-PW; Stage IV: Labial-Facial Control, Stage V: Lingual Control and Stage VI: Sequenced movements. The generation of normative data for children’s performance at these levels of speech motor control, along with the MSH-PW total scores, would be beneficial.

5. Limitations

This research analyzed data from a small sample of children comprising 41 TD participants and 13 SSD participants. All children were within the age range of 3;0 to 3;5 years. This small, limited age sample limits generalization of the findings to a larger population and those younger, or older, than this target age. Children aged between 3;0 and 3;5 years frequently present with speech sound errors (e.g.,[

59]), and it is possible that participants in the TD sample scored within age expectations on standardized assessments at the time of their participation in the study but may be identified with SSD as they get older and error patterns that are currently developmentally appropriate, persist [

37]. Similarly, the SSD group comprised children who had not previously been identified as having SSD suggesting their SSD features may have been less severe and not a broad representation of the severity of SSD in children seeking speech pathology assessment and intervention. Additionally, the SSD group were not diagnosed according to subtype using a classification framework (e.g., phonological disorder, childhood apraxia of speech)[

60]. That the SSD children as a group were significantly lower than TD controls on the VMPAC, indicating poorer oromotor and sequencing skills, suggests some speech motor involvement within the SSD group. Future research with a larger sample size is needed to investigate the role of the MSH-PW word sets in differentially diagnosing subtypes of SSD.

A further limitation of this study is that the analysis is restricted to the MSH-PW mandibular word set. These 10 words contain a limited set of consonants (e.g., m, p, b) which may be insufficient to accurately perceive differences in jaw control, phase, and syllable structure. Work is in progress to analyze the remaining stages (thirty words and four phrases) of the MSH-PW.

This study also sought to discover if it was possible to associate facial measurements extracted from recorded video with the mandibular range and control criteria of the MSH-PW. Three different measurements were tested, with further investigation of other facial measurements warranted, especially given the likely multi-dimensional nature of the MSH-PW criteria. Finally, the accuracy of extracted facial measurements in distinguishing between disordered and typically developing mandibular control was not directly tested in the present study. Future research is, therefore, needed to investigate whether objective measures obtained through facial tracking can support the differential diagnosis of SSD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.L.P., R.W., P.H. and G.R.S.; Methodology, L.O., R.L.P., R.W., P.H., G.R.S., P.D. and N.W.H; Software, R.L.P., P.E., G.R.S., P.D., N.W.H.; Validation, : Formal Analysis, L.O., R.W., R.L.P. and N.W.H.; Investigation, L.O., R.L.P, and R.W.; Resources, : Data Curation, : R.W, G.R.S, P.D. and N.W.H.; Visualization, : Supervision, R.W., P.H. and N.W.H.; Project Administration, R.W. : Funding Acquisition, R.W.

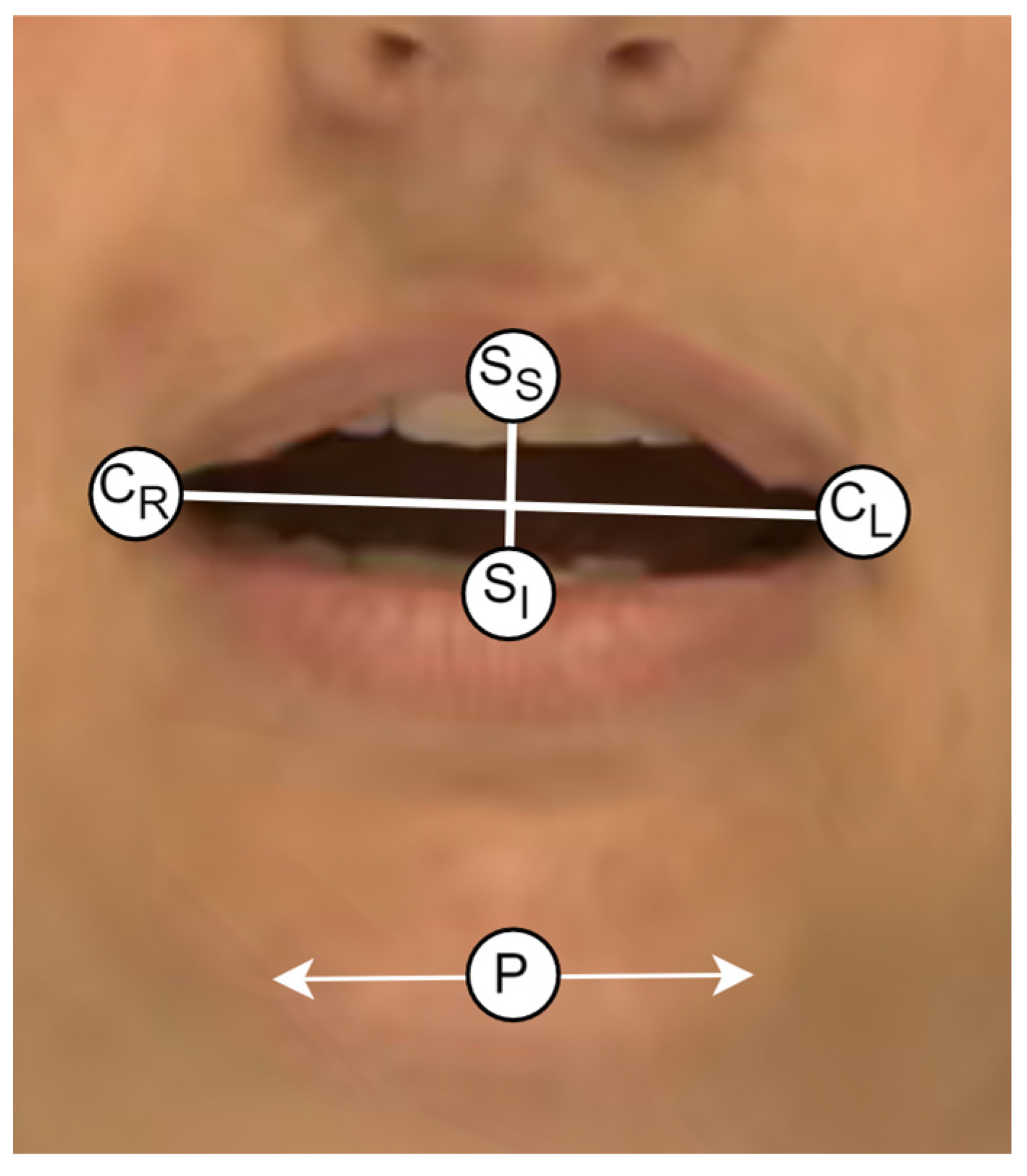

Figure 1.

The landmarks used in the extraction of the kinematic measurements.

Figure 1.

The landmarks used in the extraction of the kinematic measurements.

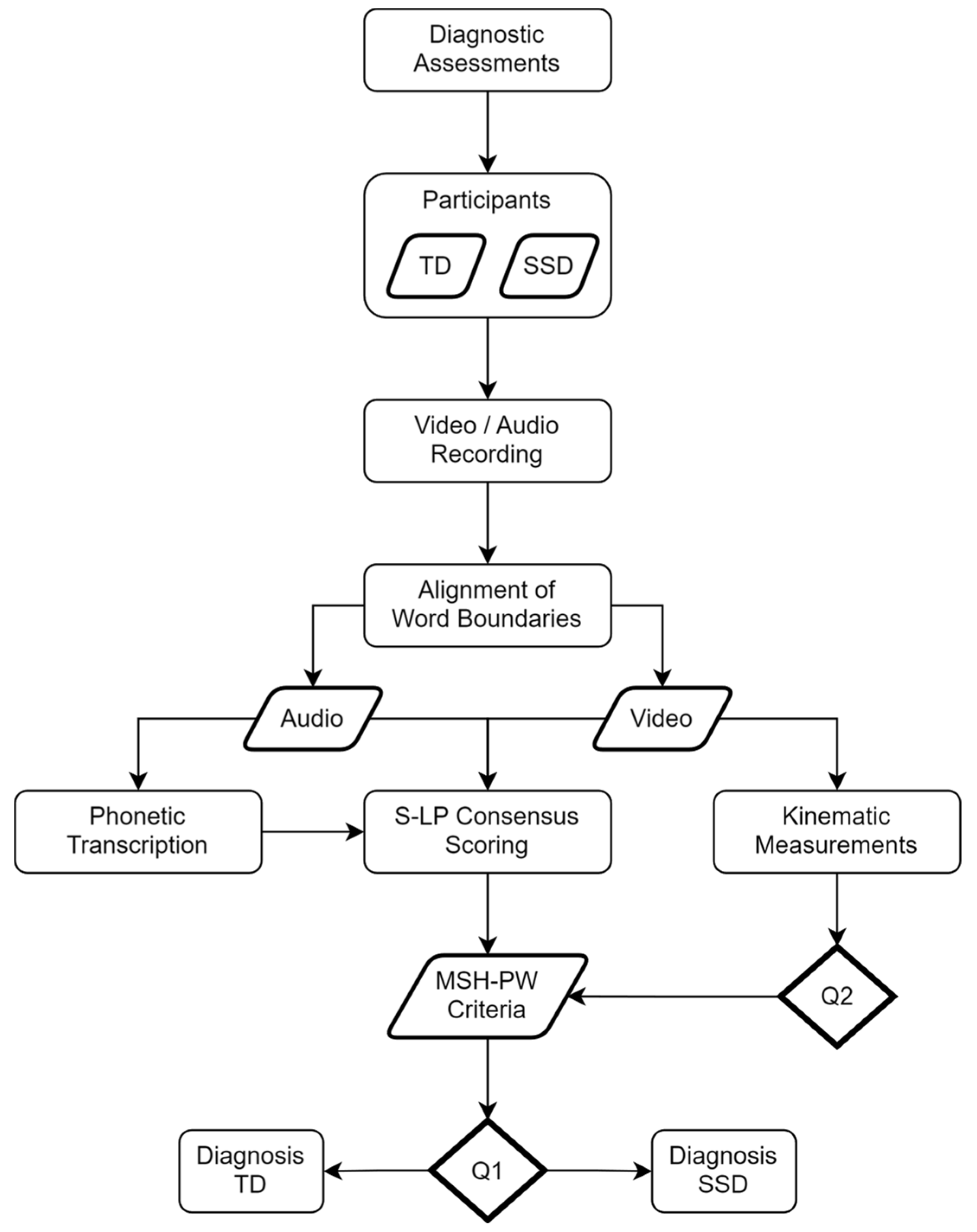

Figure 2.

Flowchart showing data collection and processing procedures.

Figure 2.

Flowchart showing data collection and processing procedures.

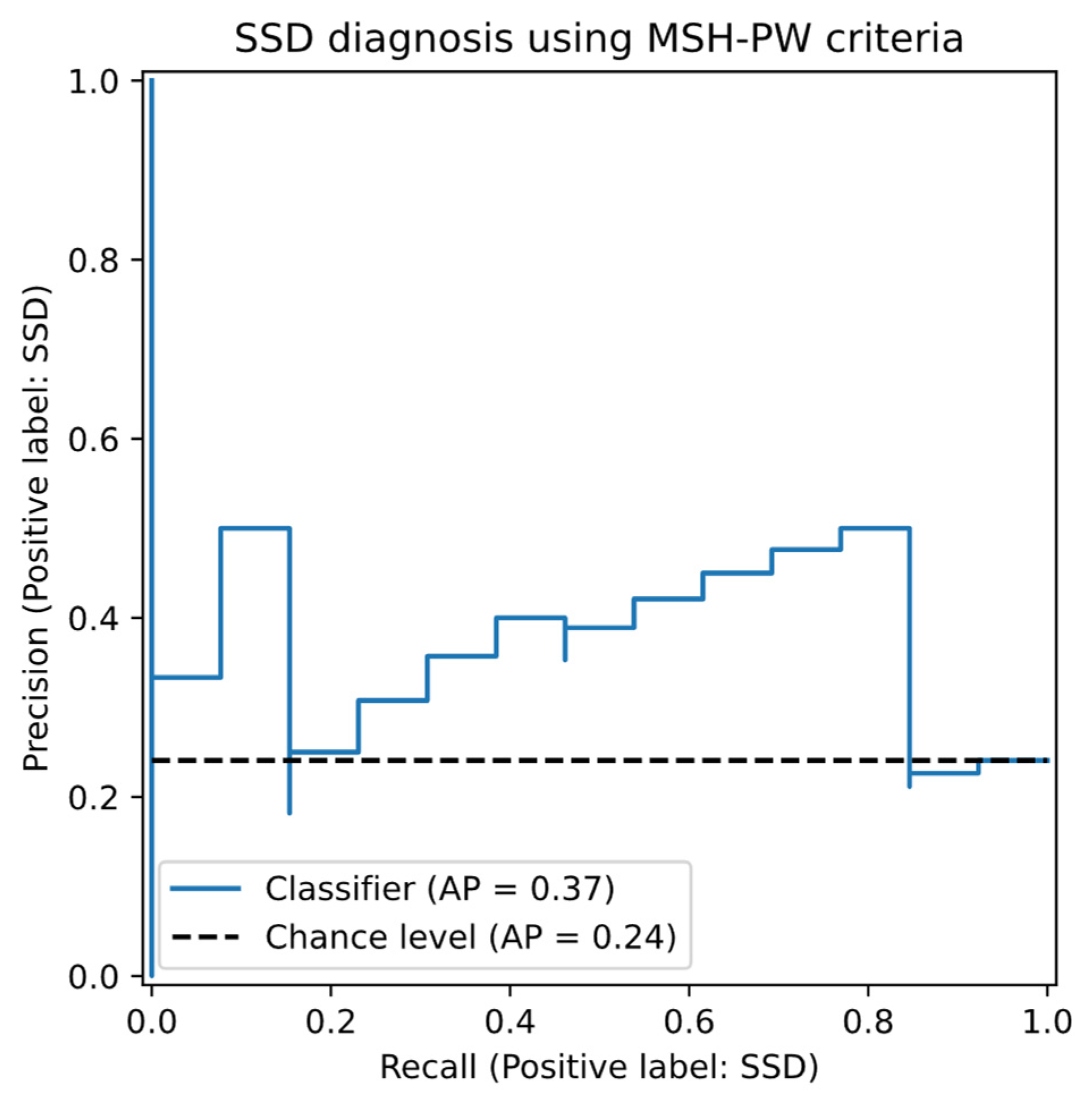

Figure 3.

Precision-Recall curve for SSD Classification using the MSH-PW Criteria.

Figure 3.

Precision-Recall curve for SSD Classification using the MSH-PW Criteria.

Figure 4.

Precision-Recall plot for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate Jaw Range using the objective mouth opening facial feature.

Figure 4.

Precision-Recall plot for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate Jaw Range using the objective mouth opening facial feature.

Figure 5.

Precision-Recall plot for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate Jaw Control using the objective “Mouth Opening velocity” facial feature.

Figure 5.

Precision-Recall plot for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate Jaw Control using the objective “Mouth Opening velocity” facial feature.

Figure 6.

Precision-Recall plot for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate Jaw Control using the objective “Mouth Opening velocity” facial feature.

Figure 6.

Precision-Recall plot for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate Jaw Control using the objective “Mouth Opening velocity” facial feature.

Figure 7.

Precision-Recall plot for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate Jaw Control using the combined objective facial features.

Figure 7.

Precision-Recall plot for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate Jaw Control using the combined objective facial features.

Table 1.

Mean (SD) Participant Characteristics for 3-Year-Old Typically Developing and Speech Sound Disordered Children.

Table 1.

Mean (SD) Participant Characteristics for 3-Year-Old Typically Developing and Speech Sound Disordered Children.

| Participant Characteristics |

TD (n = 41) |

SSD (n = 13) |

| Age (Months) |

37.90 (1.61) |

37.31 (1.65) |

ASQ-3

Communicationa

|

56.39 (5.02) |

52.78(6.18) |

| Personal Sociala

|

54.03 (5.58) |

52.22 (4.41) |

| Problem Solvinga

|

56.67 (5.61) |

56.67 (4.33) |

| Fine Motora

|

49.17 (10.79) |

53.33 (6.12) |

| Gross Motora

|

55.83(5.79) |

55.00 (4.33) |

| CELF-P2 |

|

|

| Core Language SSb

|

106.97 (9.32) |

101.45 (10.40) |

| Core Language PRb

|

65.15 (20.59) |

58.00 (28.77) |

GFTA-3

Sounds in Words SS

Sounds in Words PR

PCC

PVC

PPC |

103.48 (8.96)

57.83 (20.61)

80.81 (9.85)

99.20 (1.52)

87.10 (6.12) |

83.92 (7.24)

16.54 (12.69)

53.58 (9.05)

94.25 (6.24)

69.03 (4.55) |

VMPAC

Focal Oral Motorc

|

61.53 (14.46) |

40.29 (13.28) |

| Sequencingc

|

52.36 (14.68) |

32.00 (15.00) |

| ICS (Total Score) |

23.37 (2.38) |

21.83 (1.03) |

Table 3.

Measurement Sub-Period Intervals for MSH-PW Criteria Classification.

Table 3.

Measurement Sub-Period Intervals for MSH-PW Criteria Classification.

| Probe Word |

MSH-PW Criteria |

Sub-Period Interval (%) |

| Ba |

Jaw Range |

[20, 60] |

| |

Jaw Control |

[10, 40] |

| Eye |

Jaw Range |

[20, 60] |

| |

Jaw Control |

[10, 40] |

| Map |

Jaw Range |

[10, 50] |

| |

Jaw Control |

[5, 70] |

| Um |

Jaw Range |

[0, 70] |

| |

Jaw Control |

[0, 70] |

| Ham |

Jaw Range |

[10, 60] |

| |

Jaw Control |

[10, 60] |

| Papa |

Jaw Range |

[10, 40], [45, 80] |

| |

Jaw Control |

[10, 40], [45, 80] |

| Bob |

Jaw Range |

[10, 50] |

| |

Jaw Control |

[10, 50] |

| Pam |

Jaw Range |

[10, 60] |

| |

Jaw Control |

[10, 60] |

| Pup |

Jaw Range |

[10, 50] |

| |

Jaw Control |

[10, 50] |

| Pie |

Jaw Range |

[15, 50] |

| |

Jaw Control |

[15, 50] |

Table 4.

Means, Standard Deviations and Cohen’s d for MSH-PW Mandibular Scores for Typically Developing and Speech Sound Disordered Children.

Table 4.

Means, Standard Deviations and Cohen’s d for MSH-PW Mandibular Scores for Typically Developing and Speech Sound Disordered Children.

| |

TD |

SSD |

d (95% CI) |

|

Jaw Range

|

8.29 (1.79) |

6.46 (2.22) |

0.96 (0.31-1.61) |

|

Jaw Control

|

6.95 (2.96) |

5.38 (2.84) |

0.53 (-0.10-1.16) |

|

Phase

|

6.54(3.29) |

5.23 (2.74) |

0.41 (-0.22 - 1.04) |

|

Voicing Transitions

|

9.07 (1.17) |

7.92 (1.38) |

0.94 (0.28 - 1.59) |

|

Syllable Structure

|

9.76 (0.54) |

9.54 (0.52) |

0.41 (-0.22 - 1.03) |

|

Mandibular Percent Total

|

81.22 (15.33) |

69.08 (14.37) |

0.80 (0.16 - 1.44) |

|

PVC

|

91.23 (8.30) |

79.50 (16.17) |

1.10 (0.44 - 1.75) |

|

PCC

|

89.93(10.22) |

80.18 (13.84) |

0.83 (0.18 - 1.47) |

|

PPC

|

89.93 (7.31) |

79.75 (9.93) |

1.27 (0.60- 1.94) |

Table 5.

Confusion matrix and statistics for the classification of TD or SSD participants given expert consensus perceptual scoring of the MSH-PW.

Table 5.

Confusion matrix and statistics for the classification of TD or SSD participants given expert consensus perceptual scoring of the MSH-PW.

| |

|

Predicted |

|

|

| |

|

TD |

SSD |

Recall |

Precision |

| True |

TD |

30 |

11 |

0.73 |

0.94 |

| SSD |

2 |

11 |

0.85 |

0.50 |

| |

|

Bal. Acc. / Prec. |

0.79 |

0.72 |

Table 6.

Confusion matrix and statistics for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate Jaw Range using the objectively measured “Mouth Opening” facial feature.

Table 6.

Confusion matrix and statistics for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate Jaw Range using the objectively measured “Mouth Opening” facial feature.

| |

|

Predicted |

|

|

| |

|

Inapp. |

App. |

Recall |

Precision |

| True |

Inapp. |

71 |

45 |

0.61 |

0.38 |

| App. |

117 |

307 |

0.72 |

0.87 |

| |

|

Bal. Acc. / Prec. |

0.67 |

0.62 |

Table 7.

Confusion matrix and statistics for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate Jaw Control using the objectively measured “Mouth Opening velocity” facial feature.

Table 7.

Confusion matrix and statistics for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate Jaw Control using the objectively measured “Mouth Opening velocity” facial feature.

| |

|

Predicted |

|

|

| |

|

Inapp. |

App. |

Recall |

Precision |

| True |

Inapp. |

85 |

100 |

0.46 |

0.50 |

| App. |

84 |

271 |

0.76 |

0.73 |

| |

|

Bal. Acc. / Prec. |

0.61 |

0.62 |

Table 8.

Confusion matrix and statistics for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate Jaw Control using the objective measurement of lateral displacement of pogonion.

Table 8.

Confusion matrix and statistics for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate Jaw Control using the objective measurement of lateral displacement of pogonion.

| |

|

Predicted |

|

|

| |

|

Inapp. |

App. |

Recall |

Precision |

| True |

Inapp. |

109 |

76 |

0.59 |

0.46 |

| App. |

127 |

228 |

0.64 |

0.75 |

| |

|

Bal. Acc. / Prec. |

0.62 |

0.61 |

Table 9.

Confusion matrix and statistics for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate jaw control using the combined objective facial features.

Table 9.

Confusion matrix and statistics for the classification of appropriate / inappropriate jaw control using the combined objective facial features.

| |

|

Predicted |

|

|

| |

|

Inapp. |

App. |

Recall |

Precision |

| True |

Inapp. |

88 |

97 |

0.48 |

0.55 |

| App. |

71 |

284 |

0.80 |

0.75 |

| |

|

Bal. Acc. / Prec. |

0.64 |

0.65 |