Submitted:

04 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

0. Introduction

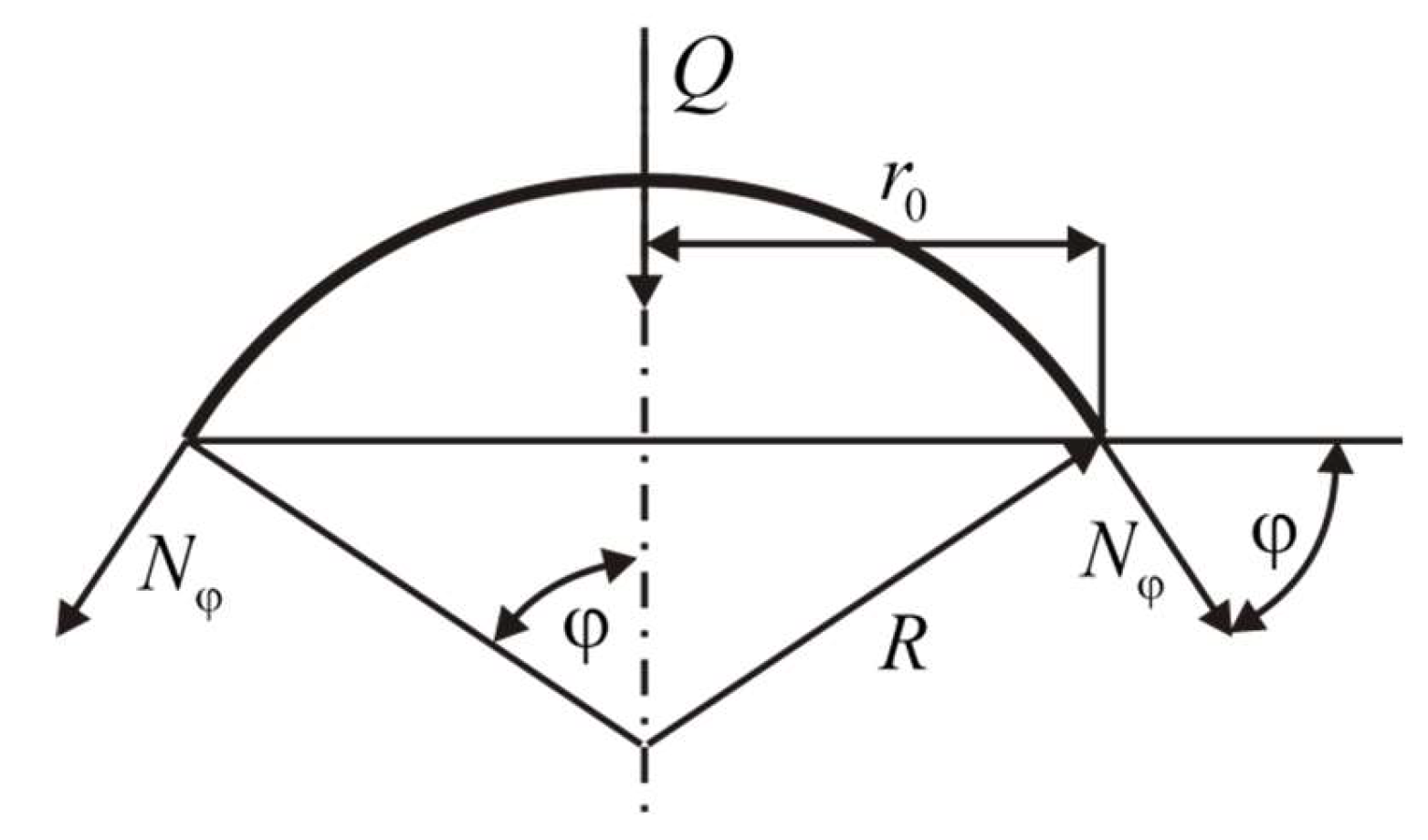

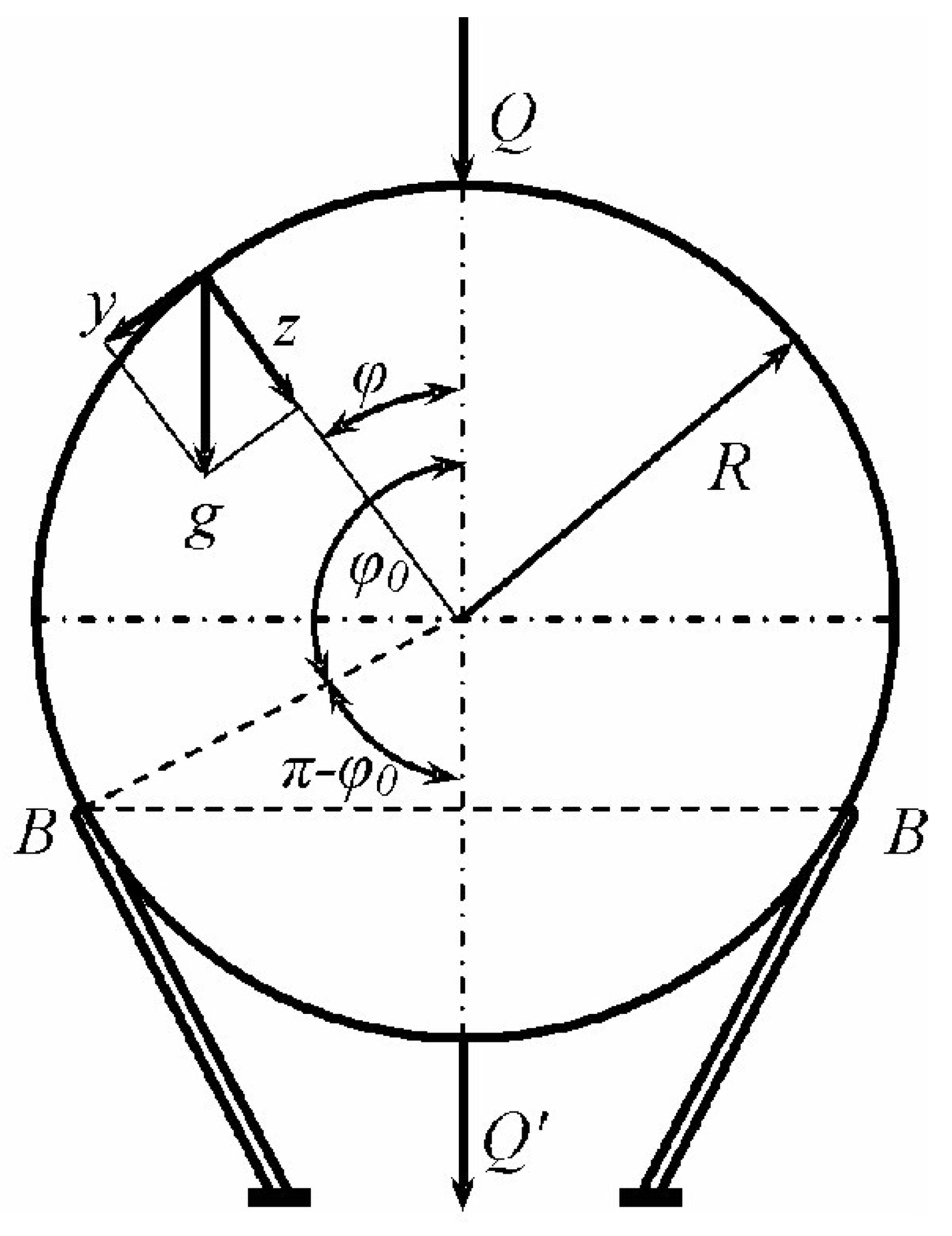

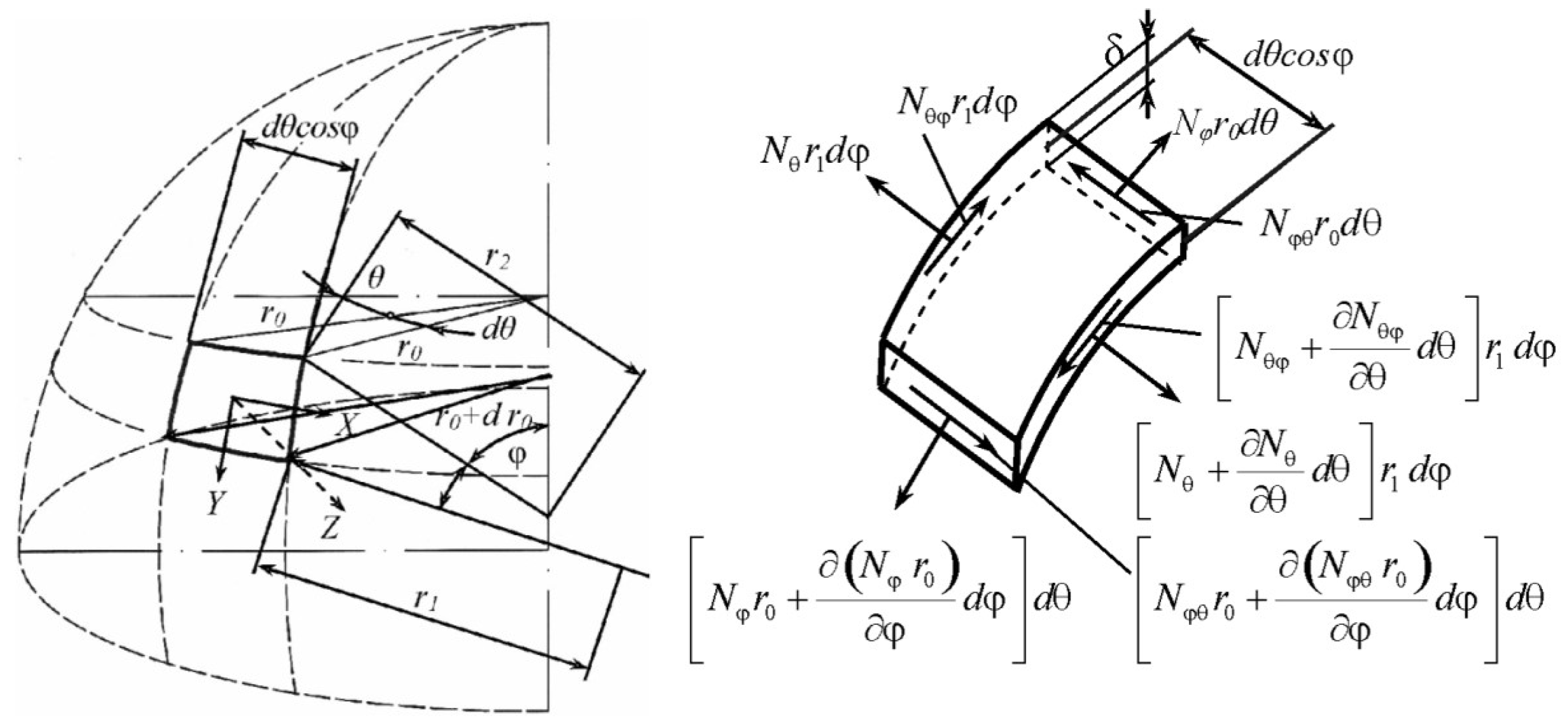

1. Mathematical Modeling

- - contribution of the change in the meridional membrane force to the equilibrium in the meridional direction

- - meridional membrane force per unit length in the spherical shell

- - is the meridional angle, measured from the pole of the sphere

- - represents the rate of change of the meridional membrane force with respect to the meridional angle

- - is likely the radius of curvature with respect to the meridional direction.

- - contribution of the in-plane shear membrane force to the equilibrium in the meridional direction .

- () - represents the in-plane shear membrane force per unit length in the spherical shell. This force acts in the plane of the shell, with one component along the meridional direction and the other along the circumferential direction.

- s the circumferential angle (or longitudinal angle)

- suggests a component of the shear force acting in the meridional direction due to curvature.

- - represents the rate of change of the circumferential component of the in-plane shear membrane force with respect to the circumferential angle. This term represents the contribution of the change in the in-plane shear membrane force to the equilibrium in the meridional direction.

- - presents the other radius of curvature which relates to the circumferential direction. For a sphere,=.

- - represents the external force per unit area acting on the spherical shell in the meridional direction.

- - shear force acting on a surface element of a spherical tank

- - rate of change of the resultant shear force with respect to the circumferential angle

- - radius of curvature of the spherical tank in the meridional direction

- - normal force acting in the circumferential direction on the surface element.

- = r \sin - radius of the parallel circle at a given meridional angle

- - normal force acting in the meridional direction on the surface element

- rate of change of the product of the meridional normal resultant (Nφ) and the radius of the parallel circle (Rsinφ) with respect to the meridional angle (φ)

- represents the external force per unit area acting on the surface of the spherical tank. The direction of this force is determined based on the overall equilibrium equation.

- - this product refers to a surface element on the surface of the spherical tank in spherical coordinates

- - resultant circumferential membrane force. It is a force per unit length acting in the tangential direction along the parallel circle of the sphere

- - radius of curvature in the circumferential direction. For a perfect sphere, () it is equal to the constant radius of the sphere, which is denoted as ( and therefore ( = = )

- circumference of the parallel circle on the sphere at a meridional angle φ

- - resultant meridional membrane force, which represents the force per unit length acting tangentially along the meridian,

- - acceleration due to gravity,

- - radius of the spherical tank,

- - meridional angle (φ), which is usually measured from the top or bottom pole of the sphere.

- - this term in the denominator shows how the meridional force varies with the angle (φ)

- a)

- proportional to the weight per unit area of the tank material (implicitly through (g)) and the density of the material, which is assumed constant and built in. Heavier material will result in higher internal forces. It is proportional to the tank radius (R). Larger tanks will generally experience higher membrane forces due to the increased material weight. At the top of the tank (φ = 0), (cosφ = 1), so . The compressive force is finite at the top. It is inversely proportional to (1+cosφ). It is shown how the meridional force changes with the angle (φ). As the angle (φ) increases towards the supports (which would be at some angle (φ < π/2) if the tank were supported around a circular base), the value of (cosφ) decreases, and (1+cosφ) also decreases, leading to an increase in the magnitude of the meridional pressure force) (). If we were to theoretically consider the equator (φ = π/2), (cosφ = 0) and (= - gR). As (φ) approaches (π) (the lower pole), (cosφ) approaches -1, and the denominator (1+cosφ) approaches 0. This suggests a theoretical singularity in the lower hemisphere if the weight of the entire sphere is taken into account and if there are no supports to directly take the load. However, in a real supported tank, this region would not be part of the “above the supports” consideration in the same way.

- b)

- Formula (5) specifically gives the meridional component of the internal membrane forces that are necessary to maintain equilibrium with the weight of the portion of the spherical tank material located above the parallelogram defined by the angle (φ). As we move down the tank (increasing (φ) this portion becomes larger and heavier, requiring greater internal compressive forces along the meridian to support it. To get a complete picture of the internal forces, one should also determine the circumferential (rim) membrane force () under this loading condition. The analysis of a spherical shell under its own weight usually involves solving the membrane equilibrium equations in both the meridional and circumferential directions. This formula provides a distribution of the meridional membrane compression force in a spherical tank due to the weight of the material over a given latitude, characterized by the angle (φ). The force increases as we move towards the supports (increasing (φ) reflecting the need to support more weight.

- - is the resultant of the circumferential (or hoop) membrane force. It is the force per unit length acting tangentially along a parallel circle at an angle (φ).

- g - Acceleration due to gravity.

- R - Radius of the spherical reservoir.

- φ - Meridional angle, usually measured from the top pole.

- 1/(1+cosφ) - This term is related to the meridional force distribution we saw earlier.

- -gRcosφ - This part suggests the contribution related to the vertical component of the meridional forces and the geometry of the sphere.

- (cosφ) denotes how the angle affects this contribution. At the top (φ = 0), (cosφ = 1), which leads to a compressive contribution. As (φ) increases, (cosφ) decreases, reducing this compression effect and potentially leading to tension at larger angles.

- gR/(1+cosφ)) - This part is directly related to the meridional force (). Since (= -gR/(1+cosφ)), the term gR/(1+cosφ) can be written as (-). It represents the contribution of the meridional tension (or compression) acting around the parallel circle, which has a radial component that needs to be balanced by the hoop stress.

- - Resultant of the circumferential (rim) membrane force.

- - Acceleration due to gravity.

- - Radius of a spherical tank.

- - Meridional angle, usually measured from the upper pole (0 to π).

- - cosine of the meridional angle.

- () : This term will have a significant impact on the behavior of () with the variable (φ).

- ( ) - contributing to the pressure at the top (φ approximately 0)) and moving towards tension as (φ) increases.

- (+ ) - As (φ) approaches 0 (the top of the tank), (cosφ) approaches 1, and the denominator (1-cosφ) approaches 0. This means that the magnitude of this term will become very large and positive, indicating a large tensile bulk force near the top. This is in stark contrast to the previous formula where () was compressive at (φ = 0).

- p=-Z – shows that the total pressure (p) is equal to the negative value of the external load per unit area (Z). In the context of a pressure vessel, the negative sign usually means that (Z) represents the internal pressure acting externally on an element of the vessel’s surface. Therefore, (p) is the internal pressure.

- γR (1-cosφ) - represents the hydrostatic pressure in the fluid at a depth corresponding to the meridian angle (φ).

- γ - specific gravity of the liquid (density times gravity, (γ=ρgh_0).

- R - radius of the spherical tank.

- (1 - cosφ) - a factor that determines the depth of the liquid depending on the angle (φ), usually measured from the top of the tank. When (φ= 0) (top), (1 - cos 0 = 1 - 1 = 0), so the hydrostatic pressure is zero. As (φ) increases, (cos φ) decreases, so (1 - cos φ) increases, which means that the depth increases, and therefore the hydrostatic pressure. At the bottom of the tank (φ = π), (1 - cos π = 1 - (-1) = 2), so the hydrostatic pressure is maximum and is (2γR) (if the tank is full to the bottom).

- - This part represents the uniform pressure that is superimposed (added) to the hydrostatic pressure. “Uniform” means that this pressure that is constant over the entire surface of the tank and does not depend on the meridian angle (φ). This pressure may come from the gas above the liquid in the tank or from some other external uniform load.

- γ -represents the unit weight of the soil supporting the spherical tank.

- R -represents the radius of the spherical tank

- φ - the angle of internal friction of the soil under the tank foundation.

- - the internal gas pressure inside the spherical tank.

- - refers to the shear strength properties of the soil and how they contribute to the bearing capacity under the load imposed by the tank.

- - involves the internal gas pressure of the tank and its radius. The factor 2 directly multiplied by the radius suggests that this could be related to the increasing force or stress distribution caused by this internal pressure acting on the tank foundation or supports.

- - represents the hoop force or circumferential normal force in a structural element at a given angle φ. It is a measure of the tension or compression acting along the circumference.

- - denotes the specific gravity (weight per unit volume) of the fluid exerting hydrostatic pressure. If the structure is submerged in water, γ would be the specific gravity of the water.

- - represents the radius of curvature of the structural element (assuming it is curved, such as an arch or cylindrical shell).

- φ - is an angular coordinate that defines the location on a structural element where the internal force is calculated. It is usually measured from a reference point, often a crown or support.

- ⌊ ⌋ - The expression enclosed in the floor function symbols (although it may be just regular parentheses depending on the context) represents the distribution of the hoop force due to hydrostatic pressure as a function of the angle φ. The trigonometric functions (cosφ) show how the depth, and hence the hydrostatic pressure, varies with angle. The term (1+cosφ) in the denominator, which suggests the angle φ is measured from above or below where cosφ = − 1 may be a special case.

- - represents the internal gas pressure acting above the support. This pressure is uniform in the area it acts on.

- This expression represents the contribution of the internal gas pressure to the hoop force. It is the direct tensile force caused by the internal pressure acting on the curved surface. It directly gives the force per unit length (the hoop force ).

- represents the hoop force resulting from the hydrostatic pressure exerted by the fluid. The magnitude of this force depends on the specific gravity of the fluid (γ), the geometry of the structure (radius R), and the angular position (φ). A complex trigonometric function captures the uneven distribution of hydrostatic pressure with depth [26]t.

- - This term describes the distribution of the meridional force due to hydrostatic pressure as a function of the angle φ. The form of this expression reflects how hydrostatic pressure and geometry contribute to the forces in the meridional direction. 1-cosφ , in the denominator suggests that the forces could become very large near the bottom (if φ is measured from the top)

- - represents the contribution of internal gas pressure to the meridional force . Similar to the hoop force, it adds a tension component due to internal pressure.

- - represents the meridional normal force at a certain angle φ in the structural element.

- - this term is related to hydrostatic pressure.

- γ - this is typically the specific gravity of the fluid exerting the hydrostatic pressure (weight per unit volume).

- R- represents a characteristic linear dimension or radius associated with the structure. The fact that it is square suggests that it is associated with an area or distributed load.

- - this dimensionless term is a function of the angle φ describing the distribution of the meridional normal force due to hydrostatic pressure along the structure.

- φ -This is the angle defining the location on a curved structure, measured from a reference

- - this term is related to the internal gas pressure .

- R- the characteristic linear dimension of the structure.

- - represents the internal gas pressure acting on the structure.

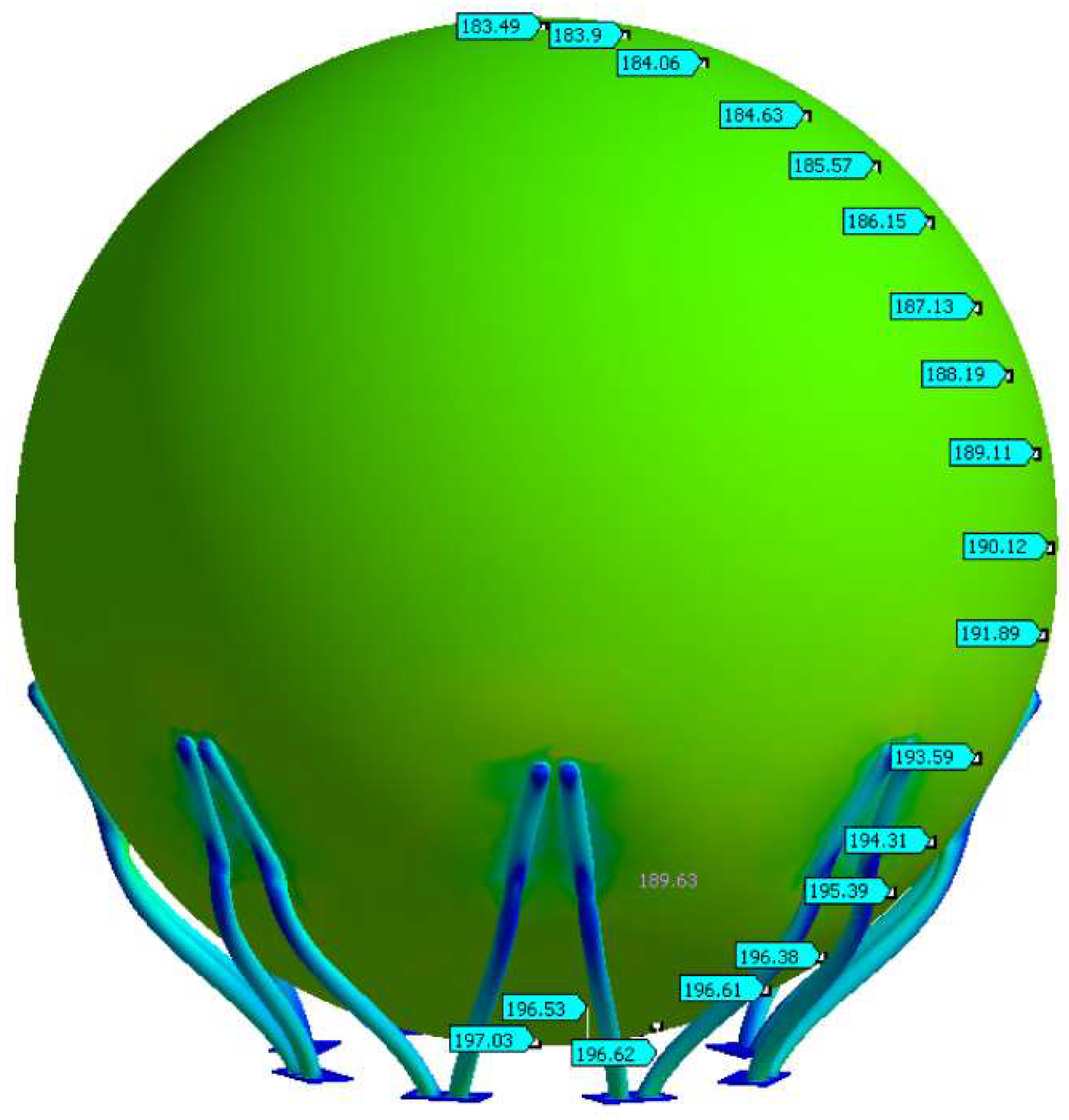

2. Finite Element Simulation and Experimental Verification

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Su, W.; Feng, X. Numerical Simulation of Failure Analysis of Storage Tank with Partition Plate and Structure Optimization. Mathematics 2021, 9, 3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiromani, R.; Shanthi, V.; Das, P. A higher order hybrid-numerical approximation for a class of singularly perturbed two-dimensional convection-diffusion elliptic problem with non-smooth convection and source terms. Computers & Mathematics with Applications. 2023, 142, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Mo, L.; Xiao, S.; Li, C.; Yang, M.; Reniers, G. Buckling failure analysis of storage tanks under the synergistic effects of fire and wind loads. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries. 2024, 87, 105208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabish, F. N. U.; Mamaghani, I. H. P. Buckling Analysis of Cylindrical Steel Fuel Storage Tanks under Static Forces. International Conference on Civil Structural and Transportation Engineering (ICCSTE’22), Canada, 2022.

- Li, X.; Chen, G.; Khan, F.; Lai, E.; Amyotte, P. Analysis of structural response of storage tanks subject to synergistic blast and fire loads. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries 2022, 80, 104891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M. A.; Soeiro, F. J. C. P.; Silva, J.G.S. Nonlinear buckling behavior and stress and strain analyses of atmospheric storage tank aided by laser scan dimensional inspection technique. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering 2022, 44, 10, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunesi, E.; Nascimbene, R.; Pagani, M.; Beilic, D. Seismic performance of storage steel tanks during the May 2012 Emilia, Italy, earthquakes. Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities. 2015, 29, 5, 04014137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Liang, S. Buckling analysis of open-topped steel tanks under external pressure. SN Applied Sciences. 2020, 2, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agboola, O.O.; Akinnuli, B. O.; Kareem, B.; Akintunde, M.A. Optimum detailed design of 13,000 m3 oil storage tanks using 0.8 height-diameter ratio. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 44, 2837–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, L.A. Buckling of vertical oil storage steel tanks: Review of static buckling studies. Thin-Walled Structures. 2016, 103, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Chen, G.; Yang, P.; Hu, K.; Zhou, L.; Men, L.; Zhao, J. Multi-hazard coupling vulnerability analysis for buckling failure of vertical storage tank: Floods and hurricanes. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 161, 528–541. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Zhao, D.; Yin, j.; Li, Y.; Chi, P.; Han, Y.; Ansari, U.; Cheng, U. Sediment Instability Caused by Gas Production from Hydrate-bearing Sediment in Northern South China Sea by Horizontal Wellbore: Evolution and Mechanism. Nat. Resour. Res. 2023, 32, 1595–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shervin, M.; Alireza, M. 3D wind buckling analysis of steel silos with stepped walls. Thin-Walled Struct. 2019, 142, 236–261, 33. Shi, L. A Study on Strength and Stability of Large Scale Crude Oil Storage Tanks. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Petroleum,Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grget, G.; Ravnjak, K.; Szavits, A. Analysis of results of molasses tanks settlement testing. Soils Found. 2018, 58, 1260–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sina, N.; Hossein, S. Experimental Investigation to local settlement of steel cylindrical tanks with constant and variable thickness. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 118, 104916. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, H.; Chen, Z.; Shen, J.; Cheng, J.; Chen, D.; Jiao, P. Buckling of steel tanks under measured settlement based on Poisson curve prediction model. Thin-Walled Struct. 2016, 106, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Fan, H.; Cheng, J.; Jiao, P.; Xu, F.; Zheng, C. Buckling of cylindrical shells with measured settlement under axial compression. Thin-Walled Struct. 2018, 123, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suranga, G.; Hoyoung, S.; William, D.L.; Priyantha, W.J. Analysis of edge-to-center settlement ratio for circular storage tank foundation on elastic soil. Comput. Geotech. 2018, 102, 136–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, N.; Hossein, S.; Tadeh, Z. Experimental investigation of geometrical and physical behaviors of thin-walled steel tanks subjected to local support settlement. Structures 2021, 34, 413–422. [Google Scholar]

- Yannis, K.C.; Panagiota, T.; Takis, G.; Amalia, G.; Jacob, C.; Stéphan, U. 3D Effective stress analyses of dynamic LNG tank performance on liquefiable soils improved with stone columns. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 174, 108170. [Google Scholar]

- Manik, M.; Sabarethinam, K. Fragility assessment of bottom plates in above ground storage tanks during flood events. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2023, 282, 104579. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, M.A.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, J.; Qian, L.; Yuan, X. Fluid dynamics analysis of sloshing pressure distribution in storage vessels of different shapes. Ocean Eng. 2019, 192, 106582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix-Gonzalez, I.; Sanchez-Mondragon, J.; Cruces-Giron, A. Sloshing study on prismatic LNG tank for the vertical location of the rotational center. Comput. Part. Mech. 2022, 9, 843–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, R.J.; Brunesi, E.; Nascimbene, R. Derivation of floor acceleration spectra for an industrial liquid tank supporting structure with braced frame systems. Eng. Struct. 2018, 171, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimbene, R.; Rassati, G.A. Seismic Design and Evaluation of Elevated Steel Tanks Supported by Concentric Braced Frames. CivilEng 2024, 5, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimbene, R.; Fagà, E.; Moratti, M. Seismic Strengthening of Elevated Reinforced Concrete Tanks: Analytical Framework and Validation Techniques. Buildings 2024, 14, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

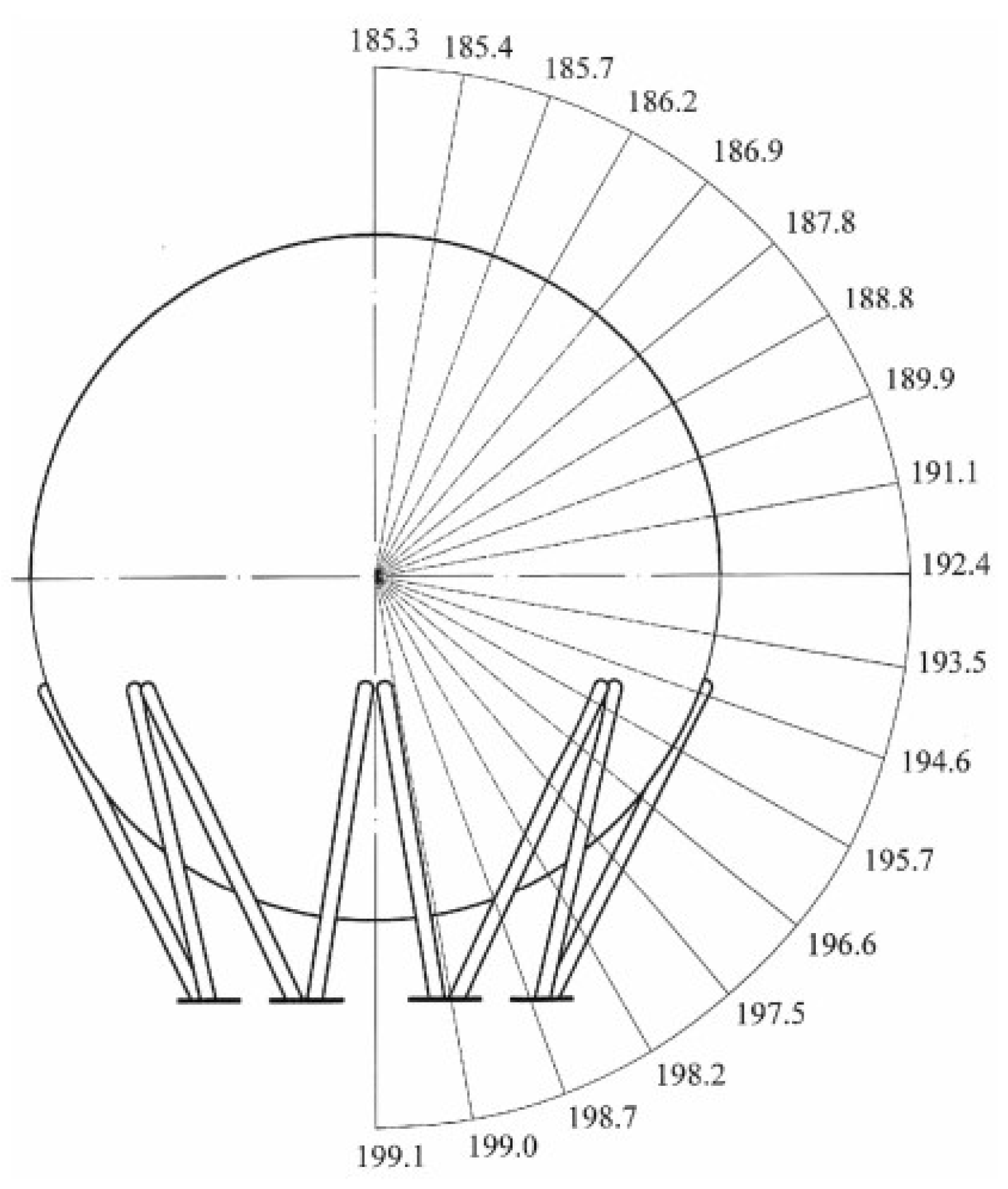

|

Angle φ (º) |

σφ (N/mm2) |

σθ (N/mm2) |

σe (N/mm2) |

| 0 | 185.3 | 185.3 | 185.3 |

| 10 | 185.4 | 185.5 | 185.4 |

| 20 | 185.5 | 185.9 | 185.7 |

| 30 | 185.8 | 186.7 | 186.2 |

| 40 | 186.1 | 187.8 | 186.9 |

| 50 | 186.5 | 189.1 | 187.8 |

| 60 | 186.8 | 190.7 | 188.8 |

| 70 | 187.2 | 192.5 | 189.9 |

| 80 | 187.5 | 194.5 | 191.1 |

| 90 | 187.6 | 196.8 | 192.4 |

| 100 | 196.9 | 189.9 | 193.5 |

| 110 | 197.2 | 191.9 | 194.6 |

| 120 | 197.6 | 193.7 | 195.7 |

| 130 | 198.0 | 195.3 | 196.6 |

| 140 | 198.3 | 196.6 | 197.5 |

| 150 | 198.6 | 197.7 | 198.2 |

| 160 | 198.9 | 198.5 | 198.7 |

| 170 | 199.0 | 198.9 | 199.0 |

| 180 | 199.1 | 199.1 | 199.1 |

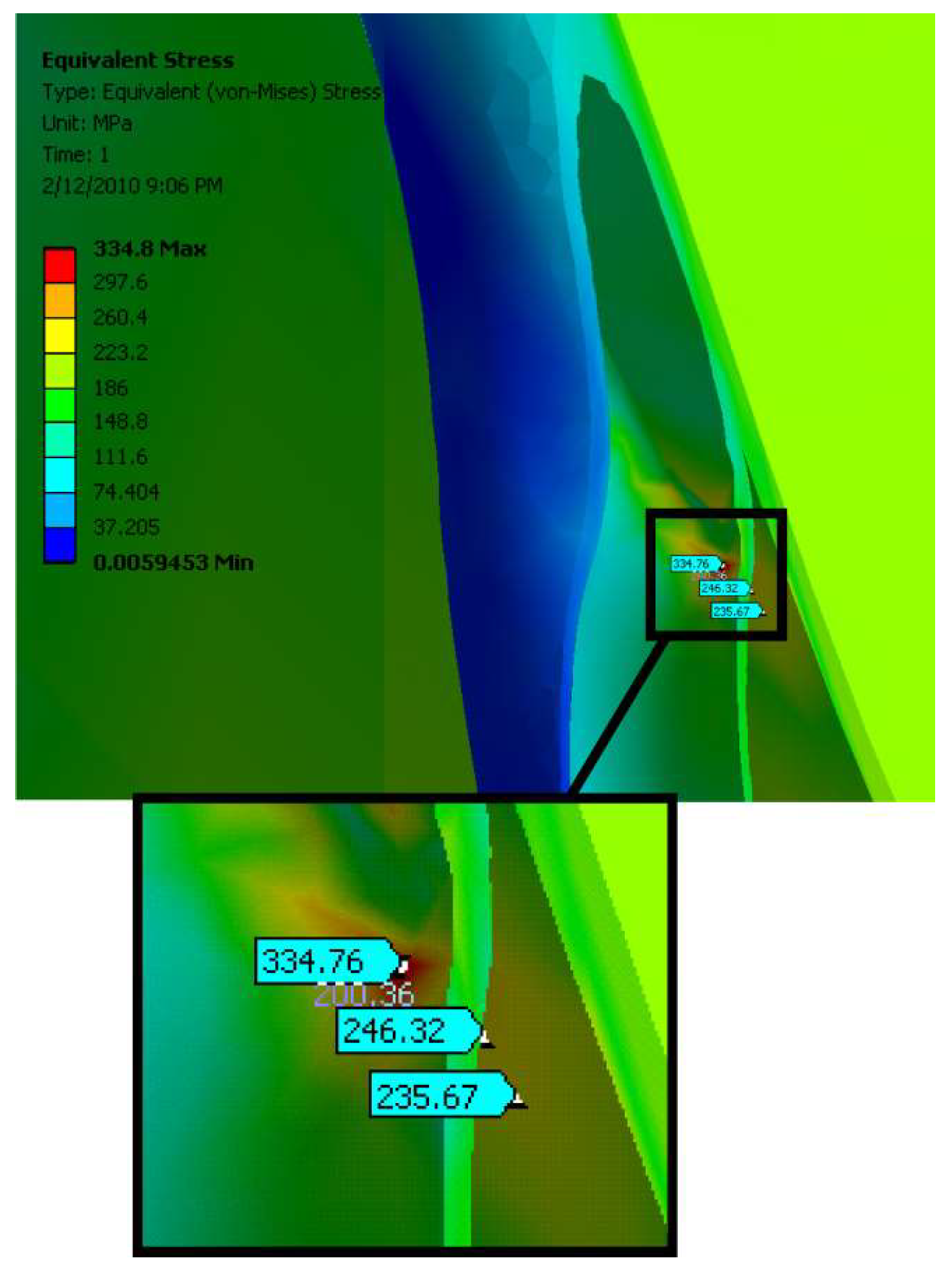

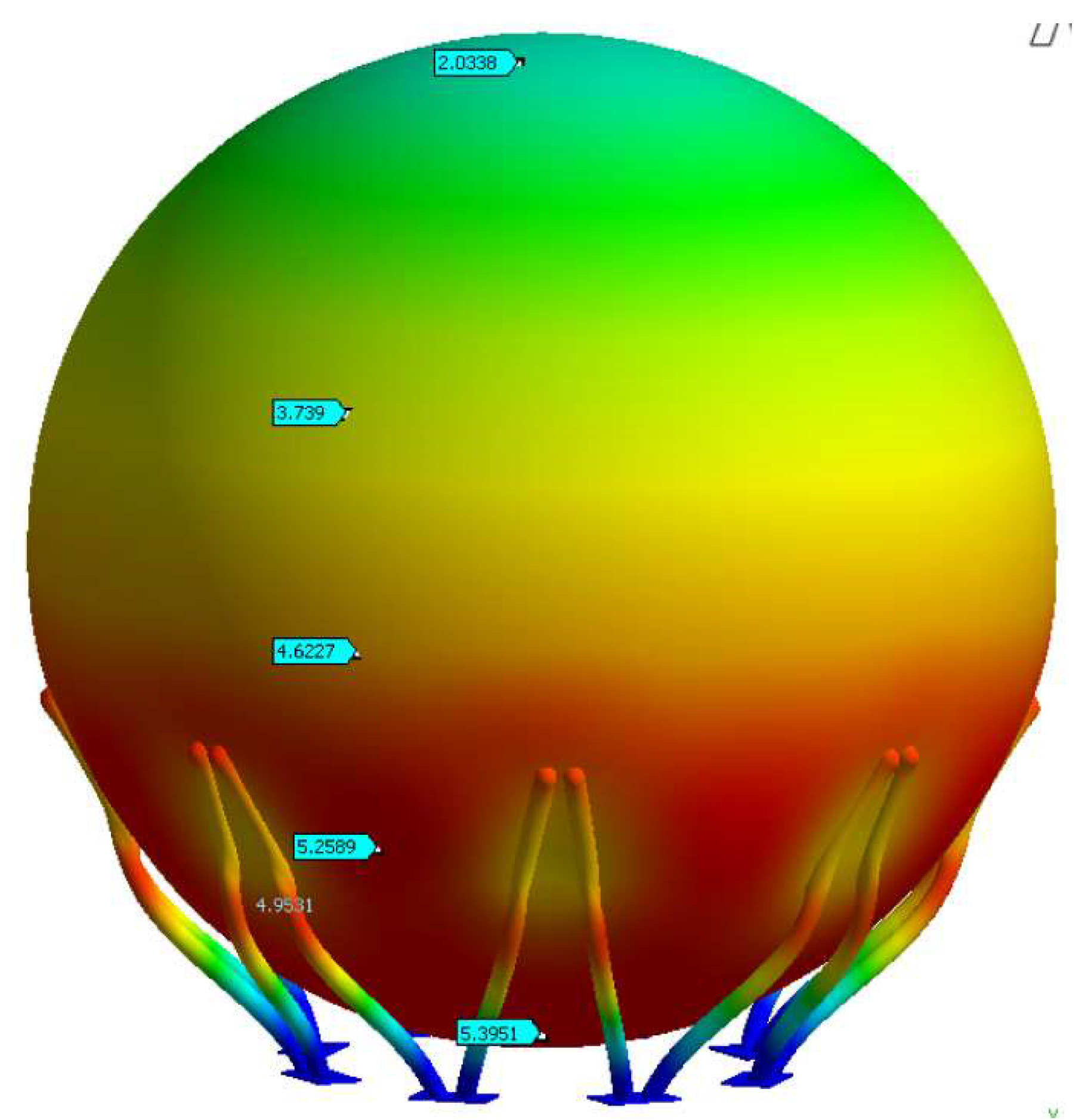

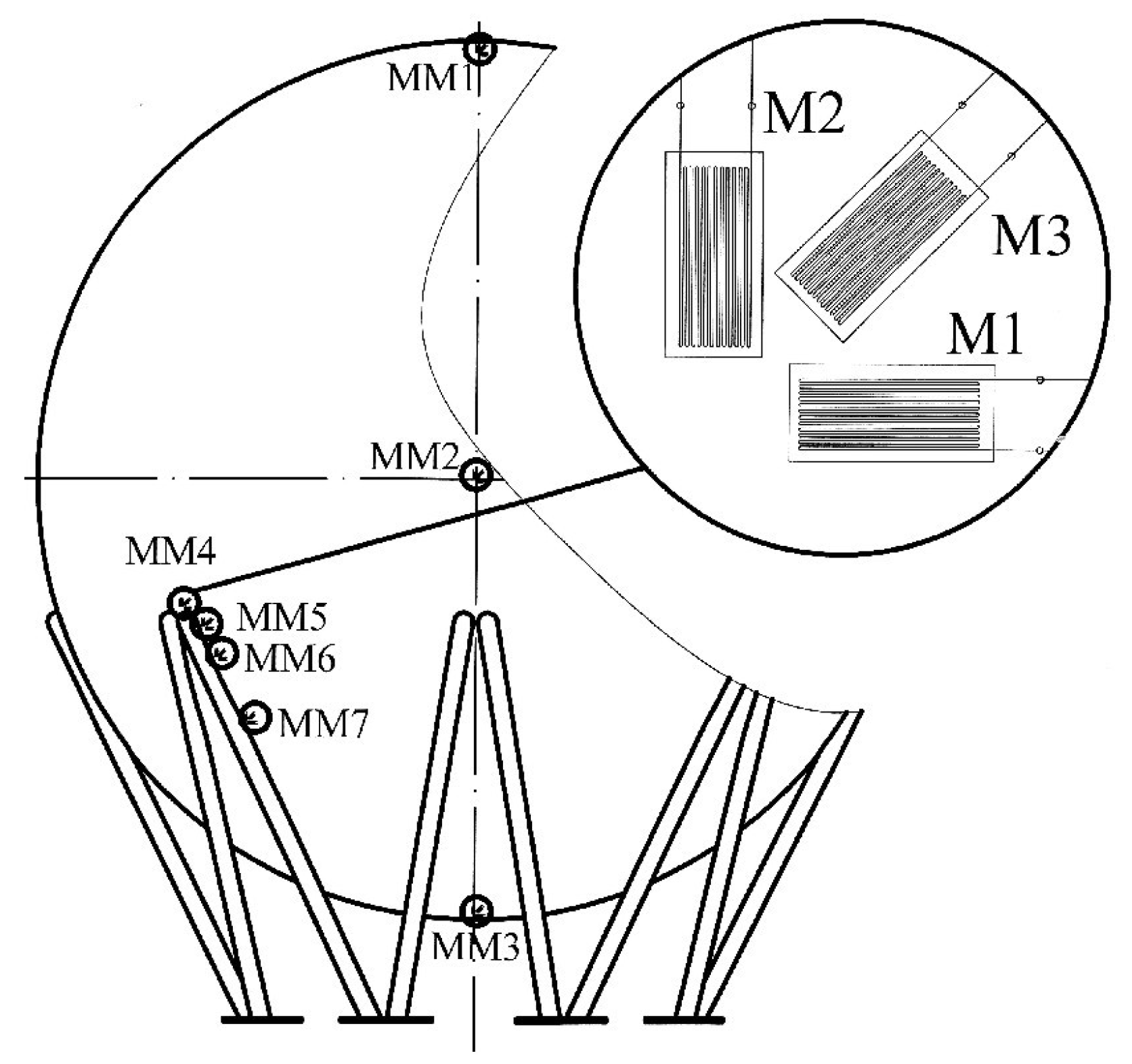

| Measuring site |

σe (N/mm2)Analytical |

σe (N/mm2) FEM |

σe (N/mm2) Experiment |

| MM1 | 185.3 | 183.5 | 169.6 |

| MM2 | 192.4 | 190.1 | 175.6 |

| MM3 | 199.1 | 197.0 | 182.3 |

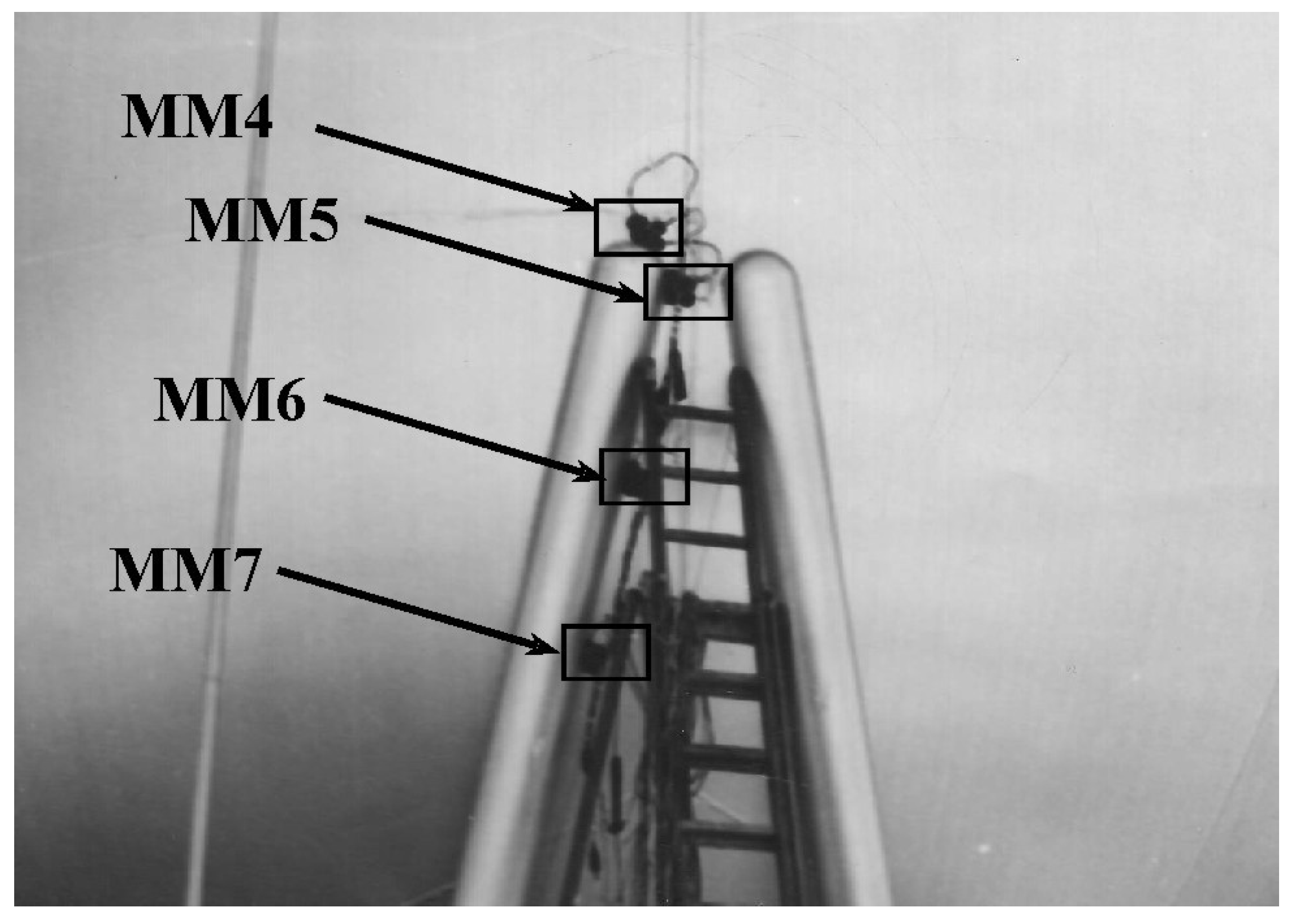

| MM4 | - | 334.8 | 343.1 |

| MM5 | 194.6 | 199.5 | 201.0 |

| MM6 | 195.7 | 194.3 | 180.1 |

| MM7 | 196.6 | 195.4 | 182.3 |

| Measuring site |

Deviation of results obtained analytically (%) |

Deviation of results obtained by FEM (%) |

| MM1 | 9.3 | 8.2 |

| MM2 | 9.6 | 8.3 |

| MM3 | 9.2 | 8.1 |

| MM4 | - | 2.4 |

| MM5 | 3.2 | 0.7 |

| MM6 | 8.7 | 7.9 |

| MM7 | 7.8 | 7.2 |

| Measuring site |

σe (N/mm2) Analytical |

σe (N/mm2) FEM |

σe (N/mm2) Experiment |

| MM1 | 277.4 | 274.1 | 256.9 |

| MM2 | 284.4 | 250.3 | 262.9 |

| MM3 | 291.2 | 288.5 | 272.9 |

| MM4 | - | 444.1 | 483.4 |

| MM5 | 287.8 | 265.5 | 282.3 |

| MM6 | 289.6 | 257.9 | 257.3 |

| MM7 | 290.8 | 259.6 | 261.6 |

| Measuring site |

Deviation of results obtained analytically (%) |

Deviation of results obtained by using FEM (%) |

| MM1 | 8.0 | 6.7 |

| MM2 | 8.2 | 4.8 |

| MM3 | 6.7 | 5.7 |

| MM4 | - | 8.1 |

| MM5 | 1.9 | 6.0 |

| MM6 | 12.6 | 0.2 |

| MM7 | 11.2 | 0.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).