2. DQFT, in a Nutshell ()

DQFT formulation emerges from a simple reconstruction of a quantum state or a quantum field operator through the discrete (a)symmetries (parity

and time reversal

) of the background spacetime. Here, we summarize the conceptual understanding of DQFT and direct the reader to [

5,

6,

7,

8] for more details. Construction of QFT in Minkowski spacetime requires the definition of positive energy state and the arrow of time [

9]. Here, we build quantum theory with two arrows of time using the direct-sum Schrödinger equation

where

is the time-independent Hamiltonian operator (which is Hermitian) that is

symmetric. The quantum state

is the direct-sum of two components

where

are the two components of the same state at parity conjugate points. The component

is a positive energy state that evolves forward in time as

where the parametric time arrow

while

can also be seen as a positive energy state that evolves back in time as

with the parametric time convention

. One can notice here the purely antiunitary character of time associated with the replacement

([

9]). The direct-sum Schrödinger equation does not have any arrow of time associated with it compared to the conventional Schrödinger equation. The direct-sum splitting of the quantum state as in Eq.

2 implies the Hilbert space (

) splitting into a direct-sum of the two (

) corresponding to parity conjugate points in position space:

. Here, the Hilbert spaces

are called the geometric superselection sectors ([

5,

7]). The position and momentum commutation relations now become double associated with parity conjugate position and momentum space operators denoted by subscripts

, and their relations are

This framework only makes the wavefunction of the quantum system explicitly

symmetric that resonates with the assumed

symmetry of the physical system, i.e.

and the results of standard quantum mechanics remain the same as shown with the example of harmonic oscillator worked out in [

8] (see also further discussions and Fig.1 in [

5]). The DQFT in Minkowski spacetime (

which is

symmetric) is just built on the direct-sum Schrödinger equation, following how the standard QFT is built on the definition of positive energy state and the causality condition (i.e., commutativity of operators for spacelike distances). See Appendix A for more details.

3. DQFT in de Sitter & Unitarity ()

The de Sitter (dS) spacetime is a perfect testing ground for exploring the theory of QFTCS because of its maximally symmetric aspect, and it is also relevant for unlocking the nature of inflationary quantum fluctuations. Furthermore, a dS spacetime has the closest resemblance with black holes, where the most important conundrums in quantum physics emerge such as the loss of unitarity and the information-loss paradox. We start with the dS metric in the flat Friedman-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) coordinates

where the scale factor

is the clock that determines the expansion of the Universe,

is the Hubble parameter and

is the conformal time. If one has to place quantum theory in dS spacetime Eq.

4 the first and foremost things to be understood are the parity and time reversal operations. The usual conception of understanding the expansion of the Universe is to restrict ourselves to

. But the metric carries a symmetry

Restricting to

before quantization of a classical field (as is usually followed in standard QFTCS) means throwing away the symmetry in Eq.

5 by hand. The expanding Universe can be realized in two ways:

This would explain why in the Wheeler-de Witt equation the cosmic time does not explicitly appear, rather the scale factor is the clock that runs with expanding Universe ([

10]). Note that

does not change any properties of the dS space at all. For example, curvature invariants such as the Ricci scalar

remain the same under a discrete sign flip of H. Eq.

6 illustrates two possible time realizations for an expanding universe. By convention, choosing

or

results in loss of information beyond the horizon. In his famous monograph of 1956, Schrodinger [

11] rejected the idea of two universes because it would lead to a conundrum of ignorance of information beyond the horizon, which in modern language means pure states evolving into mixed states which leads the violation of unitarity and information-loss ([

12,

13]).

Similar to the Minkowski space (see Appendix A), the quantum fields in the dS space are described through a direct-sum vacuum

corresponding to the direct-sum Fock space

. This implies that everywhere in dS space, a quantum field is tied by time forward and backward evolutions at the parity conjugate points, see Appendix B. At any moment of dS expansion, the parity-conjugate points on the comoving horizon

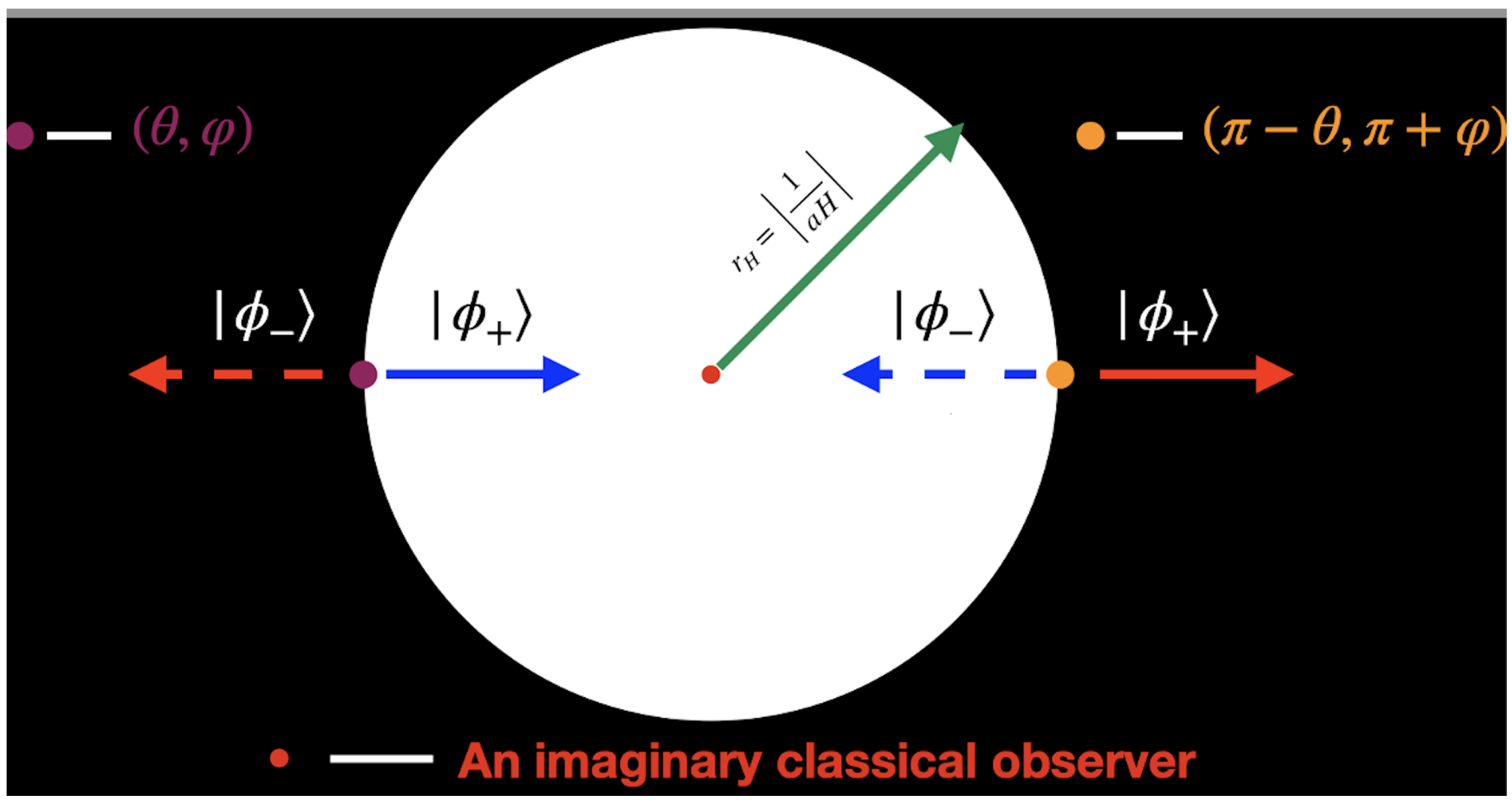

are space-like separated for an imaginary classical observer as shown in

Figure 1.

Note that by DQFT construction, the direct-sum quantum states

that follow from Eq.

A6 are the opposite time evolving positive energy states at the parity conjugate points and this holds for any imaginary classical observer. Furthermore, in DQFT the causality and locality are preserved too. A consequence of this is that any state that disappears beyond the horizon happens to be the complimentary direct-sum (component) state that reappears at the antipodal point. This is because all the imaginary classical observers, including those on the horizons of each other, should observe the same direct-sum quantum state

.

This means the horizon acts as a

mirror which maps every information outside the horizon to the states inside the horizon. To see this, consider a pure state:

where

are the eigenvectors, i.e. for any observable (an operator)

we have:

where

are the corresponding eigenvalues. Each

will be observed in

with a probability:

. Consider now the (deSitter) Hubble horizon

around an observer (as illustrated in

Figure 1). In the standard approach, information is lost (a pure state becomes a mix state) because communication can not happen for space-like distances (i.e. outside the horizon) as was shown by Gibbons and Hawking in 1977 [

12], in analogy to what happens in Hawking radiation and the black hole information loss paradox [

6,

14]. This also implies the lost of unitarity in QFT on spacetimes with horizons. In the DQFT approach we have:

where

are the eigenvectors corresponding to each

separated Hilbert space. So that the observable probabilities and operators become:

Information is not lost in this case because there is not entanglement across the horizon. To see this more clearly, consider the case where

is a pure entangled system

:

where ⊗ represents the tensor product of two Hilbert spaces

A and

B which are entangled (inseparable or correlated):

with:

and

. For example, a pair of particles (across the horizon). In the DQFT approach, we have:

where

and

are the eigenvectors corresponding to each

separated Hilbert spaces, which remain within the horizon because no information is exchanged across

separated spaces. All information about the entanglement pairs is mapped within the horizon; thus, the pure state will remain pure. In other words, DQFT forbids any entanglement beyond the gravitational horizons. DQFT constructs a direct-sum Hilbert space with the interior and exterior separated by a geometric superselection rule (which is similar to the concept of superselection sectors in QFT [

15,

16]). Thus, there would be an observer complementarity (see Fig.3 in [

5]). We can also understand the same from the point of view of dS space in static coordinates, which reads as

where

and

. The relation between the flat FLRW Eq.

4 and Eq.

12 is just a simple coordinate change ([

17,

18]). A very practiced view of flat dS spacetime in Eq.

4 is that it covers only half of the dS space. However, we must keep in mind the symmetry in Eq.

6, which implies that Eq.

4 can cover the entire dS space. Thus, the maximally symmetric nature of the dS spacetime sets no difference whether it is expressed in flat, closed, open FLRW coordinates or the static coordinates ([

19]). The use of mapping flat coordinates to static coordinates here is so that we can realize how unitarity can be achieved with DQFT, whereas it is lost in standard QFT, as was shown by Gibbons and Hawking in 1977 [

12]. In

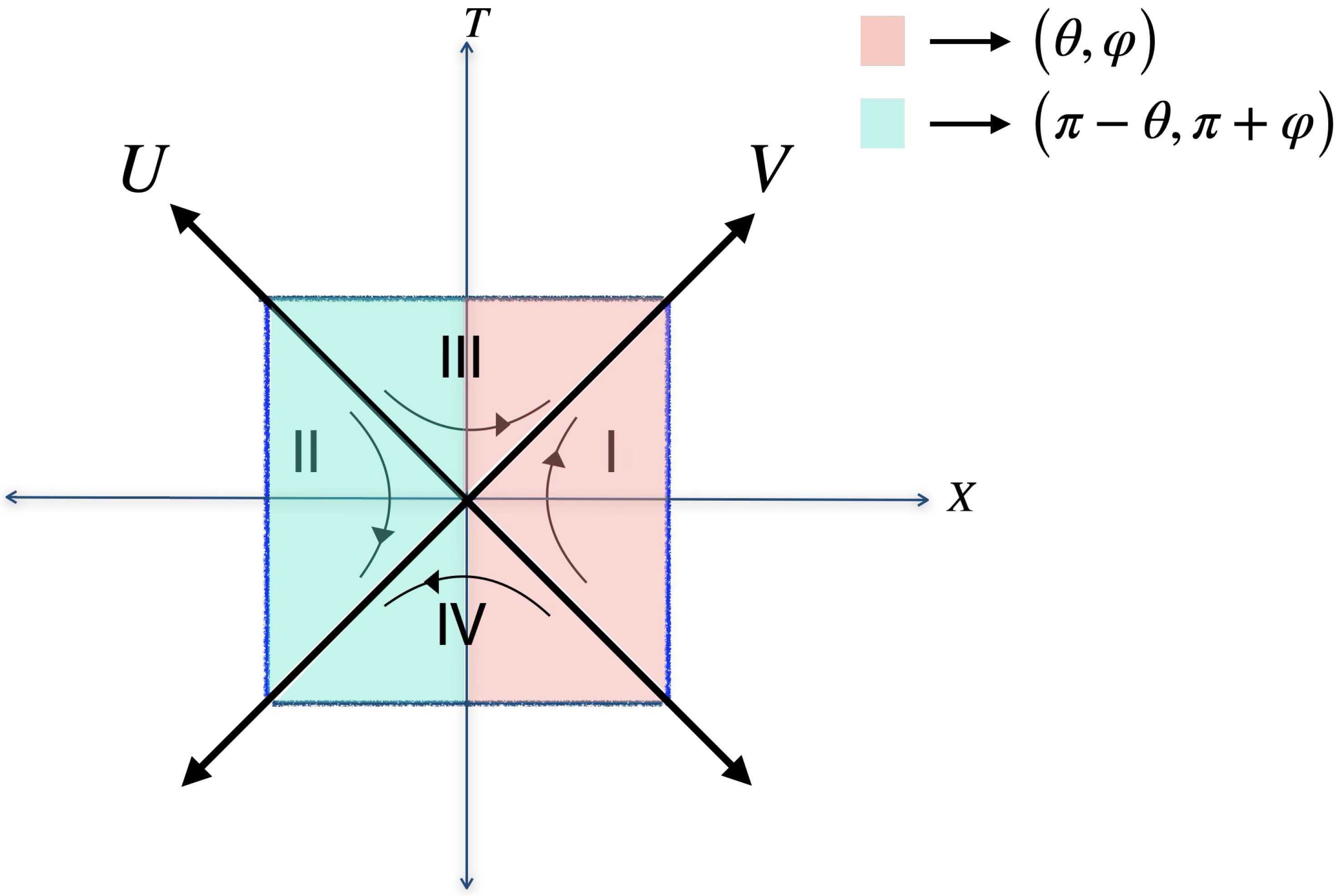

Figure 2, we show unitary quantum physics in the static dS space through the (quantum) conformal diagram, where we see the three-dimensional space divided by parity for the interior and exterior of the cosmological event horizon. We can picture here how none of the observers loses any information beyond the horizon. If any state leaves the horizon, it is only the (complimentary) direct-sum component of what is inside the horizon. This means that any observer can perfectly reconstruct the information about what is beyond the horizon. According to DQFT, every density matrix of a maximally entangled pure state is split into direct-sum of 4 components

Each density matrix

is defined by a pure state component in the corresponding (geometric) superselection sector Hilbert space

. Since Von Neumann entropy of each component of density matrix vanishes

, any observer in regions I, II, III, IV (see

Figure 2) would witness pure states evolving into pure states. Thus, with DQFT we can have both unitarity and observer complementarity in dS ([

5]).

According to DQFT, any state is spread across the horizon by distinct components in geometric superselection sectors. This implies that any information of the entangled state is shared by the sectorial Hilbert space, leading to pure states evolving into pure states. To be precise, the Hilbert spaces of the interior and exterior states cannot be connected by direct product (⊗) but rather should be related by direct-sum (⊕). This has to be like this because beyond-the-horizon time is not the same, so one cannot do the same quantum mechanics everywhere. In other words, the gravitational horizons are special, they separate different spacetimes by a boundary. Thus, they cannot be treated as a standard null surface, where quantum states can be entangled across. Furthermore, we stress that no entanglement across the horizon does not lead to firewalls, which happens in standard QFTCS but not in direct-sum QFTCS. For further analogous discussion on unitarity and no information loss in the context of the Schwarzschild black hole, see [

6]. In a nutshell, DQFT offers a new understanding of dS space where any observer’s physics of the universe is complete, and no information is lost outside any observer’s universe. This is exactly what Schrödinger envisioned in 1956 for a quantum theory to achieve [

11]. Furthermore, our achievement of DQFT echoes well with the recent classical understanding of dS through the Black Hole Universe (BHU) proposal [

20,

21,

22].

4. CMB Parity Asymmetry

Inflationary quantum fluctuations are the initial seeds for large-scale structure formation. It is important to understand their quantum nature to derive consistent CMB predictions. Inflation is by definition a quasi-dS expansion ([

23]) and this means that

in Eq.

6 is spontaneously broken by the presence of a non-perturbative scalar field in addition to the GR’s tensor degree of freedom. Our focus here is on single-field inflation. The metric and scalar field matter quantum fluctuations are generated during inflation. The quantity which is a gauge-invariant combination of them is called the curvature perturbation (

), and it is an effective (scalar) degree of freedom. It connects the quantum physics of inflation to CMB observations. The action for curvature perturbation at the linear order is

where

which is nearly constant during inflation characterized by the smallness of slow-roll parameters

for

number of e-foldings. The canonical variable which is a redefinition of curvature perturbation that we eventually quantize is

In the framework of Direct-sum Inflation (DSI), the canonical variable is promoted to field operator that is split into direct-sum of two components

which generate quantum fields in a direct-sum vacuum

in which they evolve forward and backward in time at the parity conjugate points in physical space. In analogy with Eq.

6, the time reversal operation (quantum mechanically) in an expanding quasi-dS Universe is

These sign differences in the slow-roll parameters, which break the time-reversal symmetry of de Sitter spacetime, lead to corrections in the evolution of quantum fluctuations in the parity-conjugate regions. This results in an asymmetry in the CMB temperature under spatial parity.

In spherical coordinates, the parity transformation maps a point at radial distance

r from angular position

to its antipode,

. This transformation cannot be realized by any rotation, and thus represents a discrete global symmetry distinct from statistical isotropy. It is important to emphasize that this global spatial parity asymmetry is unrelated to the observed birefringence in the CMB polarization, which arises from parity-violating interactions with well-defined transformation properties [

24].

The CMB provides temperature fluctuations

all over the sky

:

the Fourier coefficients

are characterized by the angular power spectrum

. Because

(and

is broken by the slow-roll parameters in Eq.

18, we expect the quantum field during inflation to evolve time asymmetrically at parity conjugate points in physical space. This leads to an angular power spectrum

of the CMB exhibiting an excess of power in the odd multipoles compared to the even ones, as described by Eq.

A7 in Appendix C.

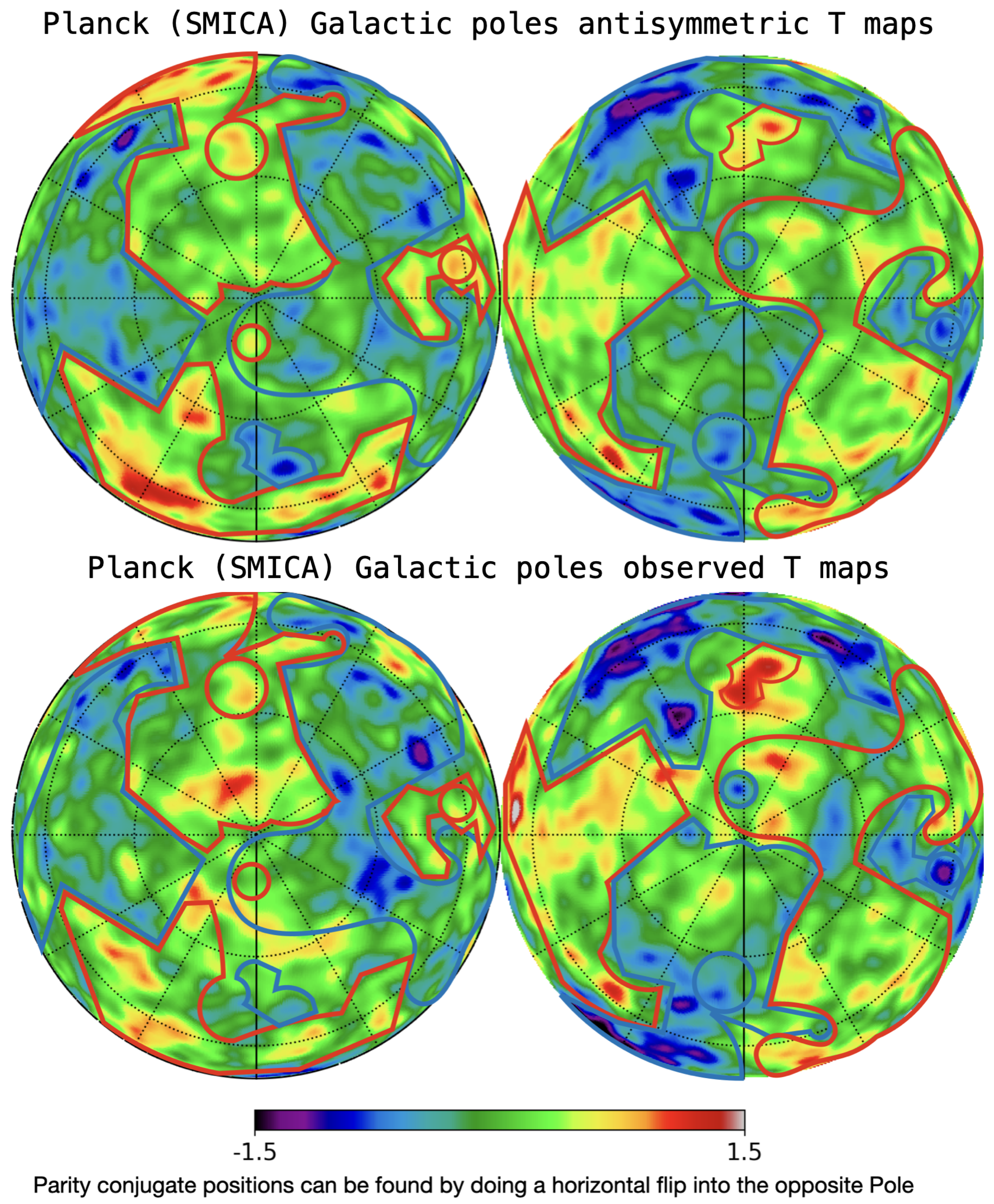

In

Figure 3, we can visually see the parity asymmetry by the close resemblance between odd-parity temperature maps and the original CMB maps from Planck data ([

25]). This reflects that the CMB temperature maps contain an additional pure odd-parity component. The DSI framework exactly generates this additional odd symmetry, as we can see in Eq.

A7. It is worth noticing here that if we take the average of even and odd power spectra, we recover the well-known near-scale invariant power spectrum of Standard Inflation (SI). The benefit of DSI is that there are no additional free parameters. The parity asymmetry only depends on the spectral index

on the pivot scale

(

) as measured by Planck data ([

26]).

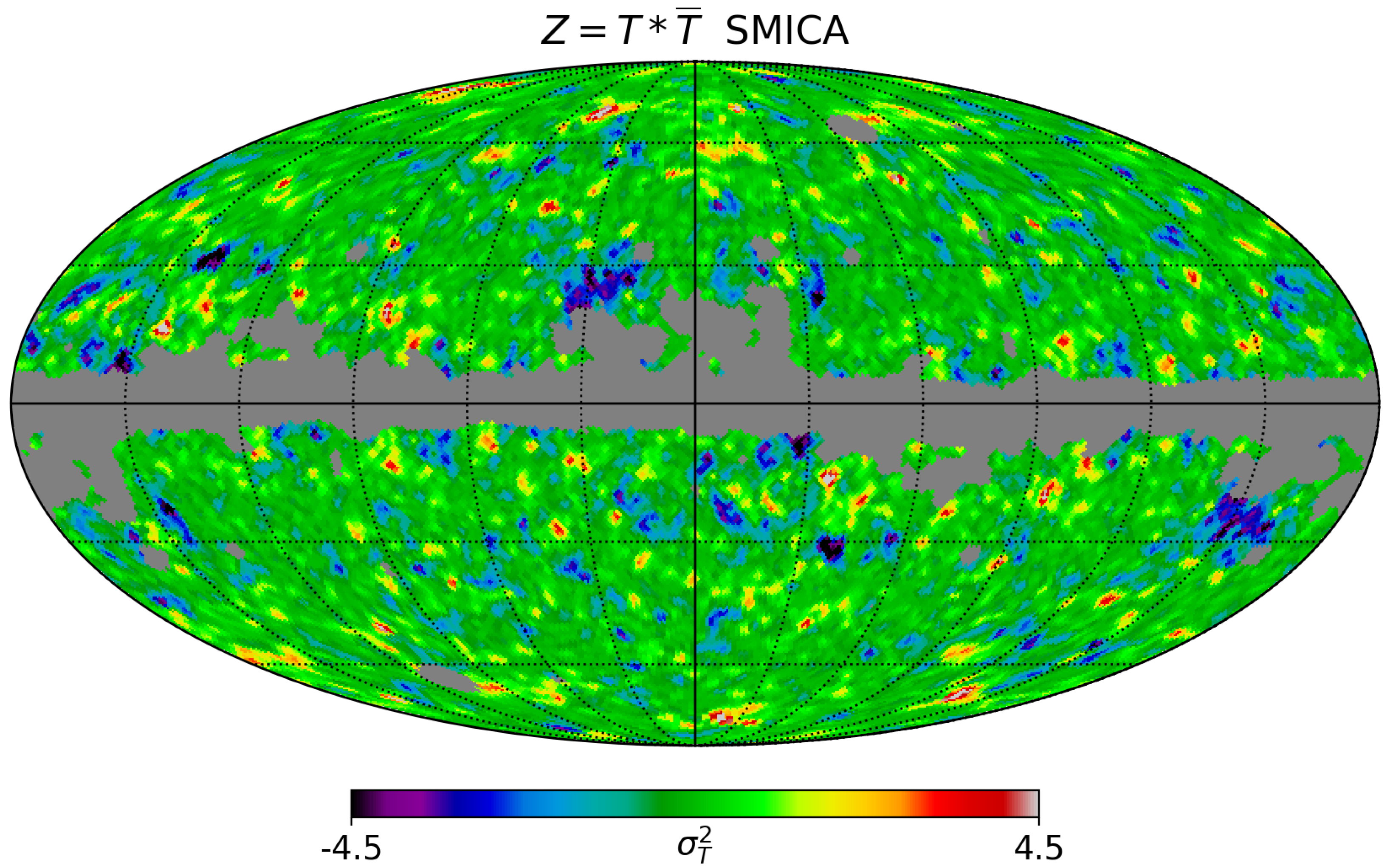

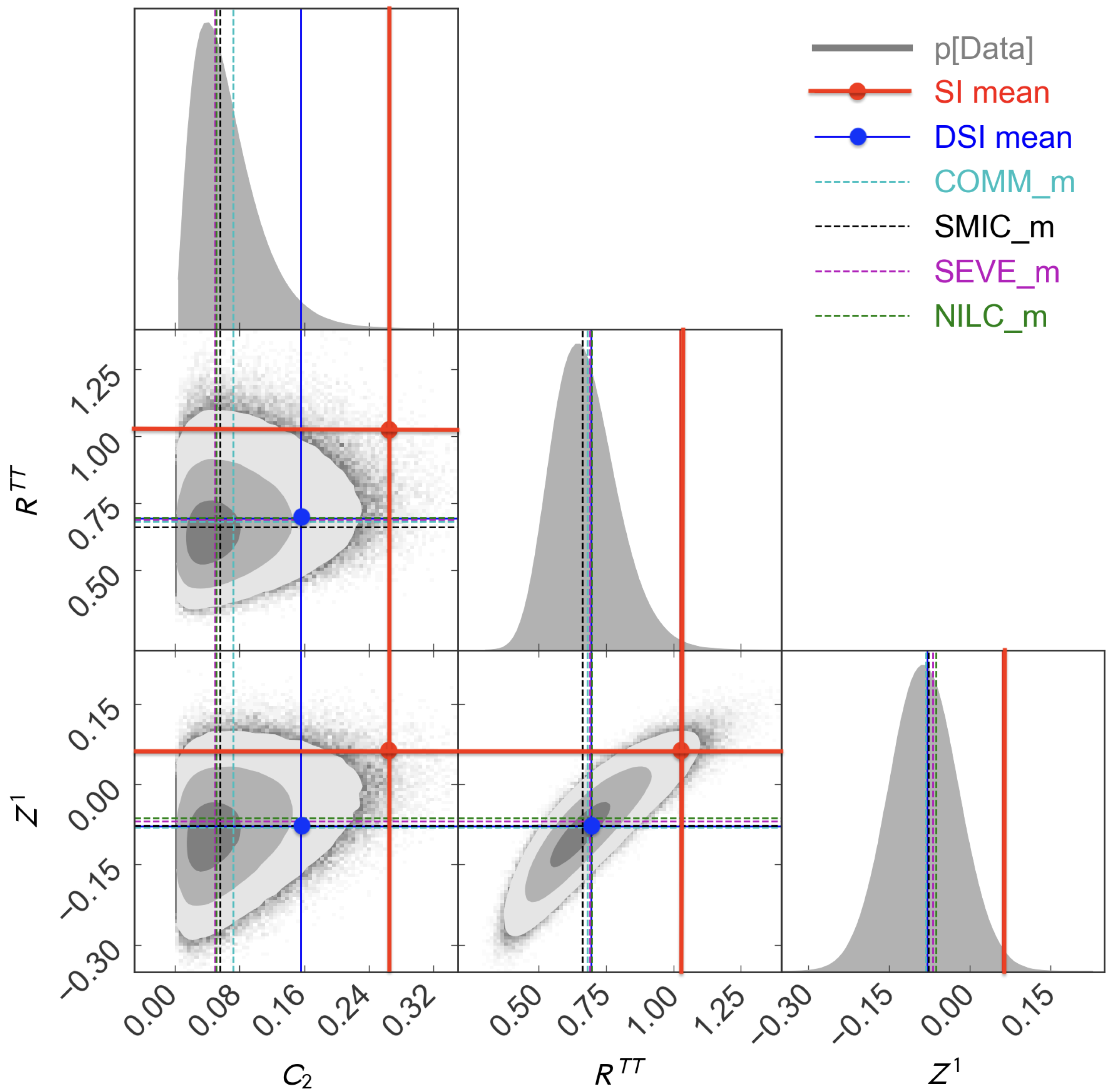

In

Figure 5 we present how the observational data significantly prefer DSI over SI. Observed quantities include the observed low quadrupolar amplitude

, the even-to-odd multipole ratio of angular power spectra:

and the mean

of the parity map

displayed in

Figure 4, where

represents the parity conjugate or antipode of the sky position

. The likelihood probability associated with DSI in these plots is up to 650 times larger than that of SI. DSI favors odd parity, leading to a lower

. This, in turn, diminishes the significance of other CMB anomalies ([

27]), such as the Hemispherical Power Asymmetry, the axis of Evil, and the anomalous 2-point correlation function (see [

8] for further details).