Introduction

Hypoxia in tumor cells is a key feature in many solid and aggressive cancers which arises from inadequate oxygen consumption to oxygen delivery ratio in the tissue [

1,

2]. As the tumor cells divide, their metabolic demands increase, significantly outpacing the oxygen supply provided by existing vasculature. Although neovasculature aims to compensate for the oxygen and nutrient shortages, these new blood vessels are often dysfunctional and inefficient, leaving the oxygen delivery to remain inadequate [

3,

4]. This oxygen shortage creates a hypoxic tumor microenvironment (TME), which acts as a major cellular stress factor. To adjust to the hypoxic TME, cells activate a series of adaptive reactions that augment the cell survival and proliferation [

1,

2,

5]. As a result, hypoxic TME not only plays a critical role in tumor progression, but also profoundly influences cellular interactions with the surrounding stroma, vasculature, and immune cells [

2].

The adaptive reactions triggered by hypoxia are complex processes that involve several mediators, with hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), playing a pivotal role as the main molecular mediators of the hypoxic response. Among them, HIF-1 is particularly important, functioning as a heterodimeric transcription factor composed of two subunits: HIF1-α and HIF-1b. This complex activates the expression of hundreds of genes that enable tumors to adapt and thrive in low-oxygen conditions. These genes regulate key processes such as angiogenesis, glucose metabolism, cell survival, migration, invasion, and immune modulation [

1,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Through these metabolic and genetic adaptations, tumor cells can maintain their growth despite the challenging microenvironment [

6,

9,

11].

In addition, tumor hypoxia greatly affects the tumors’ biological behavior [

1,

5,

6,

9]. Hypoxic tumors have been shown to be more invasive, exhibit resistance to conventional therapies such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy, as well as successfully evade the immune system. Overall, hypoxic tumors are often associated with a poorer prognosis, demonstrated by their increased metastatic potential and higher likelihood of local and metastatic recurrence [

2]. Therefore, it is paramount to understand the molecular biology of hypoxia in order to establish efficient therapeutic targets for cancer treatment [

6,

8,

9].

Developing new therapeutic strategies by targeting hypoxia-driven pathways has emerged as a promising approach to cancer treatment in recent years. They aim to specifically target hypoxic tumor cells while minimizing damage to healthy tissues. The main strategies include the direct inhibition of HIF activity, addressing hypoxia-induced metabolic changes in the TME, and the development of hypoxia-activated prodrugs that selectively target tumor cells in hypoxic TME. These therapies seek to enhance treatment efficacy and overcome hypoxia-induced resistance to conventional therapies [

1,

2,

9,

12].

This review article provides a comprehensive analysis of how hypoxia influences cancer cell biology by examining hypoxia-related metabolic and genetic changes in the TME. It focuses on the extensively studied subunit of HIF transcriptional factor, HIF1-α, and its downstream effects. Additionally, it offers an overview of the intercellular junctions and how they are downregulated under low oxygen conditions. The article explores the molecular pathways that regulate angiogenesis, metabolic reprogramming, cell migration and invasion, and immune evasion—key factors that drive cancer cell behavior in the hypoxic TME.

Discovery of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF-1)

In a seminal study, Semenza and Wang first reported a specific nuclear factor, now known as HIF-1, that is induced by hypoxia in cultured cells and binds to the human erythropoietin gene enhancer [

13]. Subsequent work revealed that HIF-1 is a heterodimeric protein consisting of an oxygen-sensitive HIF-1α subunit and a constitutive HIF-1β subunit [

14]. Under normal oxygen conditions (normoxia), HIF-1α is rapidly degraded, while HIF-1β remains stable but inactive. However, when oxygen levels drop, HIF-1α accumulates in the cytoplasm, and translocates to the nucleus. There, it dimerizes with HIF-1β to form an active HIF-1 complex, which then binds to hypoxia-response elements (HREs). This complex activates the transcription of target genes that mediate hypoxia responses and drive shifts in energy metabolism to support cell survival in low oxygen environment [

10,

15].

By the late 1990s, additional studies clarified the mechanism of HIF-1α degradation, identifying the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor as a critical regulator that earmarks HIF-1α for oxygen-dependent proteolysis [

16]. Later research by Hu et al. on the differential roles of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in governing transcriptional programs revealed that these isoforms can activate overlapping but distinct gene sets, highlighting their slightly different contributions to hypoxic adaptation [

17]. These discoveries established a new framework for understanding how cells and tissues sense and respond to low oxygen levels, paving the way for a deeper exploration of hypoxia-induced metabolic reprogramming.

HIF-1α: Master Regulator of Hypoxic Response in Cancer

HIF1-α is the oxygen-sensitive subunit of the HIF-1 transcription factor that orchestrates cellular adaptation to hypoxia. It plays a critical role in cancer progression and therapy resistance by regulating gene expression changes that drive cancer progression, through processes such as angiogenesis, metabolism, cell survival, and metastasis [

2,

6]. By mediating hypoxia-adaptive pathways, HIF1-α enables cancer cells to successfully survive in low oxygen conditions, making it a major target for cancer therapeutics development.

The protein structure of HIF-1α includes a basic helix-loop-helix domain near the C-terminal, two distinct PAS (PER-ARNT-SIM) domains, a PAC (PAS-associated C-terminal) domain, a nuclear localization signal motif, two transactivating domains (CTAD and NTAD), and an intervening inhibitory domain. The PAS domains, which facilitate protein-protein interactions, enable HIF-1α to dimerize with HIF-1β (also known as ARNT) and form a heterodimeric complex, which then binds to hypoxia-response elements (HREs) in the promoter regions of target genes to regulate hypoxic adaptation [

7,

11,

18,

19].

The regulation of HIF-1α is tightly controlled at the post-translational level through several modifications, including hydroxylation, ubiquitination, and proteasomal degradation. Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α is rapidly degraded via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. In the presence of oxygen, prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) enzymes catalyze the hydroxylation of specific proline residues on HIF-1α. The hydroxylated HIF-1α is then recognized by the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor protein, which targets it for ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation [

18].

However, under hypoxic conditions, the activity of PHD enzymes is inhibited due to the lack of oxygen, enabling HIF-1α to evade hydroxylation, which leads to the stabilization and accumulation of HIF-1α levels. Once stabilized, HIF-1α translocates to the nucleus, where it dimerizes with HIF-1β and binds to hypoxia-response elements (HREs) in the promoter regions of target genes to activate their transcription [

11,

12,

18,

20,

21,

22]. After binding, the HIF-1 complex recruits transcriptional coactivators, such as CBP/p300, which help it sustain the gene expression and enhance transcriptional activity [

23,

24].

HIF-1α controls the expression of over 60 genes involved in key cellular processes, including the regulation of the genes that drive tumor growth. By upregulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other pro-angiogenic factors, it promotes the growth of neovasculature to supply tumors with the nutrients needed for their growth and metastasis [

8,

9]. To further improve oxygen delivery to hypoxic areas, HIF-1α also induces erythropoietin production, which stimulates the production of red blood cells, thereby ensuring a sustained oxygen supply to the tumor region

.

Beyond aiding oxygen delivery, HIF-1α drives cancer cell invasion and metastasis. It achieves that by promoting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and influencing the expression of genes that remodel extracellular matrix and support cell migration [

2,

6,

9,

25,

26]. Additionally, HIF-1α helps tumor cells adapt to low oxygen conditions by adjusting their metabolism and influencing iron homeostasis, securing a sustained and effective hemoglobin and enzyme production. In terms of metabolic adaptation, it activates genes involved in upregulation of glucose transporters (e.g. GLUT1 and GLUT3) and the enzymes of the glycolysis pathway, which promotes anaerobic energy production [

1,

25,

27,

28,

29]. This shift to glycolytic metabolism allows tumor cells to generate metabolic intermediates needed to support rapid cell growth and proliferation while efficiently producing ATP [

29,

30].

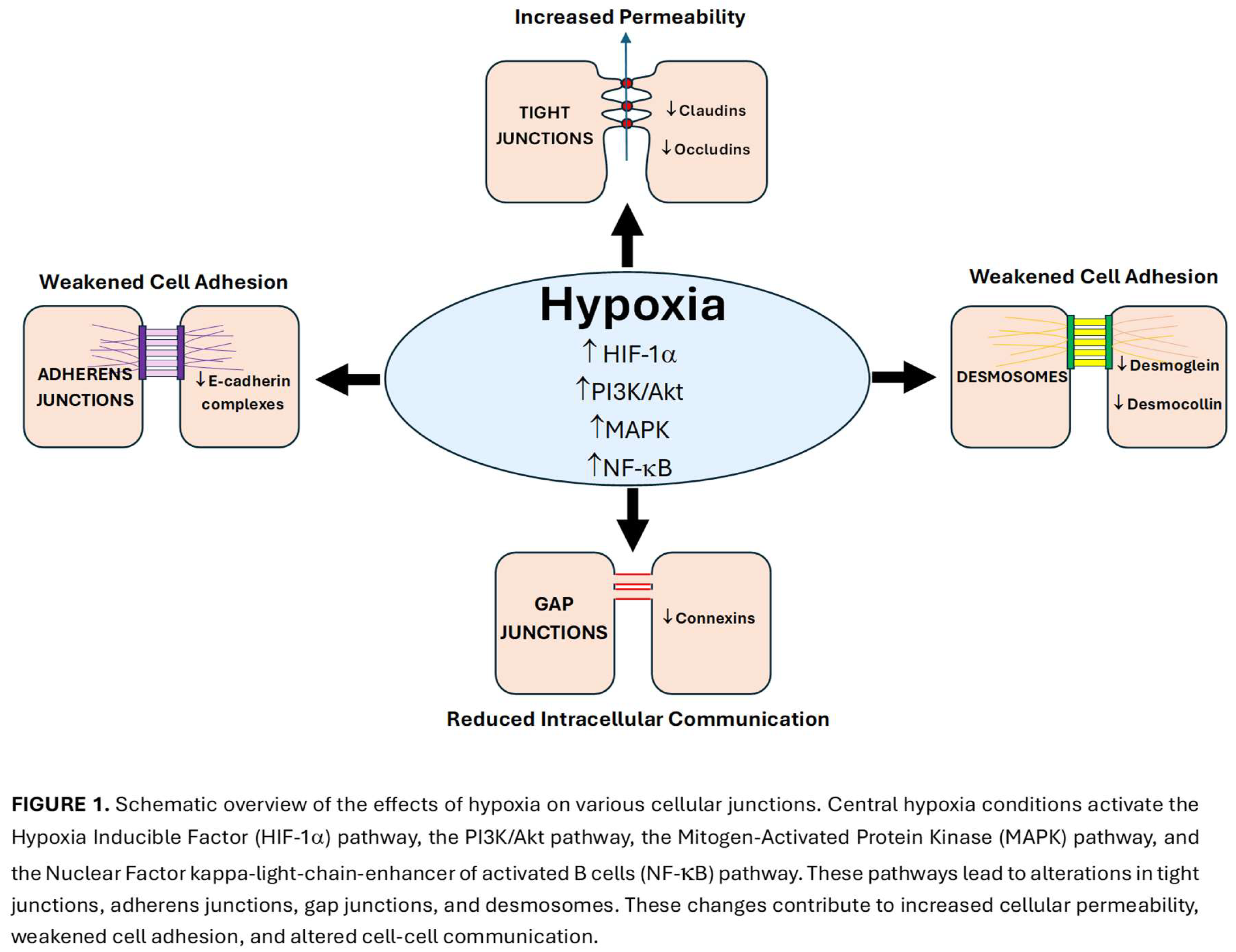

Hypoxia and gap junctions

In addition to its metabolic and genetic effects, hypoxia significantly influences cellular junctions, making it a crucial factor to address for a comprehensive understanding of cancer cell behavior in the TME [

31]. Cellular junctions, which include gap junctions, tight junctions, adherens junctions, and desmosomes, play a key role in maintaining intercellular communication, cell-cell adhesion, and tissue integrity. These intercellular channels can be compromised under hypoxic conditions, as HIFs activate genes that disrupt gap junctions as part of cellular adaptation response to hypoxia. By weakening these junctions through multiple mechanisms, HIFs promote invasion and facilitate tumor metastasis [

32,

33] (

Figure 1).

Hypoxia-induced alterations in cellular junctions highlight their potential as targets for novel therapeutic strategies aimed at reversing hypoxia-driven changes in the TME.

Gap junctions: Mechanism and Structure

Gap junctions function as communication channels between cells, playing crucial roles in all organisms to ensure coordinated function. They facilitate transfer of molecules up to 1 kDa, including amino acids and ions[

34]. Their primary function involves the exchange of ions for electrical signaling and the coordination of cell signals, often acting as secondary messengers [

35]. Gap junctions are particularly important in electrically excitable tissue, such as cardiac muscle, where they enable the sharing of electrical current between cells to ensure synchronous contraction. However, they also play a role in tissues that are not electrically active, in which case they allow nutrients and waste products to travel throughout the tissue [

34].

Gap junctions act as channels with permeability that vary based on their connexin composition [

34]. Connexins are the protein subunits that form connexons, with six connexins forming a connexon. Two connexons from adjacent cells dock together to form the gap junction [

36]. These hexameric assemblies form a 2-nanometer extracellular gap, ensuring high selectivity and allowing only small ions and molecules to pass through.

Connexins are composed of intracellular N- and C-termini, extracellular E1 and E2 loops, and four transmembrane domains [

31]. The E1 and E2 loops connect transmembrane domains (T1-T2 and T3-T4), while a cytoplasmic loop spans the intracellular space between T2 and T3. Connexins are classified by predicted mass into five subfamilies

—α, β, γ, δ, and ε in mice and GJA, GJB, GJC, GJD, and GJE in humans. Each subfamily has distinct biophysical properties and expression patterns, contributing to functional diversity [

36]

.

Physiological function of gap junctions

Gap junctions play essential roles in transport in both electrically excitable and non-electrically excitable cells. In excitable cells, such as neurons, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle, gap junctions function as electrical synapses, allowing ions to flow through cells to generate action potentials. That enables rapid, synchronized cell communication, ensuring coordinated electrical and mechanical signaling across the tissue [

34,

37]

.

Gap junctions are also crucial in non-excitable cells, where they facilitate the transport of nutrients and signaling molecules. In the liver, they enable glucose transport from glycogen stores during sympathetic stimulation. Sympathetic axons terminate at the edge of the liver lobules, with the remainder of the lobule being stimulated through the diffusion of secondary messengers via gap junctions [

34].

Moreover, gap junctions can act as suppressors of somatic cell mutations by allowing adjacent cells to compensate for defects or deficits in critical enzymes or ion channels. For example, in Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, a mutation in the HGPRTase enzyme leads to excessive urate production. By forming gap junctions with healthy cells, metabolic cooperation helps mitigate the effects of the mutation [

34,

38].

Adherens Junctions

The primary function of adherens junctions is to provide strong attachments between epithelial cells, ensuring proper tissue integrity. These junctions consist of protein complexes anchored to the actin cytoskeleton, and the key proteins that make up adherens junctions are cadherins and catenins (β, ɑ, and

γ) [

39].

Epithelial cadherin (E-cadherin) establishes intercellular contact through homophilic interactions with other E-cadherin proteins on neighboring cells. Additionally, E-cadherin interacts with catenins, which play essential roles in nucleocytoplasmic trafficking, transcriptional regulation, and ubiquitination. This interaction enables anchoring of the adherens junction to the actin cytoskeleton in the cytoplasm [

40,

41,

42].

Other important proteins in adherens junctions include vinculin, nectin, and afadin. Vinculin maintains the structure and stability of the adherens junction by binding to ɑ-catenin and β-catenin, acting as a mechanical stabilizer and linking cell adhesion complexes to the actin network. Nectin, in complex with afadin, also connects the adherens junction to the cytoskeleton through the facilitation of cell-cell adhesion. By trans-dimerizing with nectins on the neighboring cells as well as recruiting E-Cadherin to contact sites, nectin further strengthens cell adhesion [

39,

43].

E-cadherin also undergoes trans-dimerization with neighboring cells, leading to the fusion of clusters and the formation of a mature adherens junction. Once established, the adherens junction binds to actin through ɑ-catenin, which crosslinks the actin filaments, stabilizing the junction within the cytoskeleton. Overall, this complex structure enables adherens junctions to maintain strong cell-cell connections. The importance of these proteins was demonstrated through afadin knockout experiments, which ultimately led to the disorganization of cell junctions. Additionally, inhibiting nectin dimerization has been shown to prevent cadherin-dependent adherens junction formation [

42,

43].

Adherens junctions and EMT

Adherens junctions play a vital role in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process in which epithelial cells lose their apical-basal polarity and weaken their cell-cell junctions. EMT drives tissue morphogenesis during embryonic development and facilitates wound healing by closing open wounds. However, when dysregulated, EMT can be exploited by cancer cells to promote metastasis. Several transcription factors promote EMT, including SNAI1 (Snail), TWIST1, and ZEB. Snail represses the expression of E-cadherin, thereby leading to the disassembly of adherens junctions. This is a critical step in EMT process, as it allows cells to detach from epithelium and migrate to other areas [

42,

44,

45,

46].

Adherens junctions regulate EMT through two main pathways: endocytosis and component recycling, which occur both via clathrin-mediated and non-clathrin-mediated mechanisms. Dysregulation of these pathways in cancer disrupts the balance between recycling and degradation, leading to rapid loss of E-cadherin and increased cell migration. An important oncogene involved in this process is Src, which phosphorylates tyrosine residues on E-cadherin, displacing p120-catenin and activating signaling pathways that inhibit E-cadherin expression, ultimately promoting tumor progression [

45,

46,

47].

Overall, adherens junctions play a crucial role in maintaining cell-to-cell adhesion by forming a strong scaffold that holds cells together and anchoring them to the cytoskeleton. The proteins that make up adherens junctions, such as E-cadherin, undergo modifications during EMT to facilitate essential processes like wound healing under normal conditions. However, when dysregulated, EMT can contribute to cancer progression [

42,

45]. Understanding the mechanisms of EMT and adherens junctions as well as their interplay can provide insights into potential cancer treatment strategies.

Tight Junctions

Like adherens junctions, tight junctions play key roles in cell-to-cell adhesion, polarity, and migration. Tight junctions are composed of various proteins such as claudins, which help maintain cell adhesion, regulate signal transduction, cell growth, and migration through EMT [

39]. Their regulation is influenced by multiple factors including angiogenesis, glycolysis, and hypoxic conditions. Among these, hypoxia is a primary contributor to defects in tight junction proteins.

Under low oxygen conditions, the upregulation of HIF-1 disrupts multiple signaling pathways involved in the regulation of tight junction proteins [

27,

39,

48]. Specifically, hypoxia can increase JAM3 expression, decrease Par3 levels, and alter the transcription of various claudin proteins [

27,

49]. These changes compromise tight junction integrity, ultimately promoting cancer metastasis.

Hypoxia-induced signaling disruptions can downregulate claudin proteins; in cancer, claudins – particularly claudins 3, 4, and 7 - tend to be dysregulated. Changes in their expression, both downregulation and upregulation, can weaken cell adhesion and alter the structure and function of tight junctions [

48,

50]. And, when tight junctions and their associated proteins lose proper function, cell motility increases—a process that cancer cells exploit during metastasis [

48,

51].

CLDN1 is a key claudin in tight junctions that regulates multiple signaling pathways involved in cell invasion and migration. Due to its broad regulatory function, CLDN1 is influenced by various pathways, including regulation by ADAM15 through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, which is associated with breast cancer signaling [

52,

53]. Additionally, upregulation of CLDN1 has also been observed to activate the ERK signaling pathway in the MCF7 breast cancer cell line, further emphasizing its role in cancer progression. These findings highlight the important role of claudins in cellular signaling pathways and demonstrate how disruptions in these pathways can contribute to tumor formation and metastasis [

53,

54].

Tight junctions also contain Par3 protein, which plays a crucial role in aligning the apical barrier of cells. Reduced levels of Par3 have been associated with increased metastasis in cancer cells [

39,

48]. Similarly, JAM3, another tight junction protein, contributes to the regulation of EMT. Overexpression of JAM3 has been observed in cancers characterized with excessive EMT activity, underlining the impact of tight junction components on tumor advancement [

49,

51].

Desmosomes

Desmosomes are another important structure that promotes cellular adhesion, linking cells through intermediate filaments. They function as adhesive junctions that couple cells through desmosomal cadherins, which include desmogleins (DSGs) and desmocollins. These cadherins mediate calcium-dependent cell-to-cell adhesion, which is essential for desmosomal function [

55,

56].

Among desmosomal genes, DSG2 is particularly affected by hypoxia and is dynamically regulated by the oxygen levels in the TME, playing a key role in promoting metastatic processes [

54,

57]. In hypoxic tumor regions, DSG2 is downregulated, which triggers EMT-related gene expression changes in primary tumors. EMT enables cancer cells to detach, undergo intravasation, and circulate throughout the body. As tumor cells exit hypoxic conditions and undergo reoxygenation, DSG2 expression is reinstated, enabling them to successfully colonize distant organs [

54,

58].

HIF1-α serves as a key regulator of DSG2 repression in hypoxia by recruiting EZH2 and SUZ12, components of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2). Their binding to the DSG2 promoter results in sustained DSG2 repression, a process correlated with poor prognosis and increased recurrence risk, particularly in breast cancer patients [

54,

58,

59]

Disruption of Cellular Junctions by Hypoxia

As normal cells acquire a tumor-like phenotype, they undergo multiple gene expression changes that lead to EMT. A key feature of EMT is the disruption of cell junctions, which weakens cell-cell communication. Under hypoxic conditions, gap junction communication among noncancerous cells is downregulated, primarily due to their disruption. Hypoxia interferes with gap junction function through multiple mechanisms, including transcriptional repression, post-translational modifications, and trafficking impairments of connexins [

60].

Mechanisms of Hypoxia-Induced Gap Junction Disruption

Hypoxia leads to a reduction in connexin expression, particularly connexin 43 (Cx43), through HIF-1α-mediated transcriptional repression. HIF-1α binds to hypoxia-responsive elements (HREs) in the promoter regions of target genes, altering their transcription. In the case of connexin genes, this results in decreased mRNA synthesis and lowered protein levels. Reduced connexin expression weakens the formation and functionality of gap junctions, impairing intercellular communication [

60,

61].

- 2.

Post-Translational Modifications

Under hypoxic conditions, increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) leads to oxidative stress, which directly affects connexin proteins. Key post-translational modifications that pertain to gap junction destruction during hypoxia include phosphorylation, which alters the gating properties of gap junction channels, reducing their ability to remain open. In addition, the processes of nitrosylation and oxidation destabilize the connexin structure, making it more susceptible to degradation. These modifications disrupt the assembly and functionality of gap junction channels, further impairing gap junction intercellular communication (GJIC) [

62].

- 3.

Gap Junction Channel Dysfunction

Connexins are highly sensitive to changes in calcium concentration as calcium is involved in the activation of protein kinases, which then phosphorylate connexins. Excessive calcium levels and subsequent phosphorylation lead to conformational changes that close the channels. Thus, hypoxia-induced elevation of intracellular calcium levels contributes to the closure of gap junction channels, which reduces the ability of cells to exchange critical signaling molecules [

63].

Notably, hypoxia also interferes with the intracellular trafficking of connexins to the plasma membrane, such that instead of being transported to their functional locations, connexins may accumulate in the Golgi apparatus or instead be targeted for lysosomal degradation. This reduction in functional gap junctions at the cell surface leads to diminished intercellular signaling and coordination, further compromising proper tissue functioning [

31,

64].

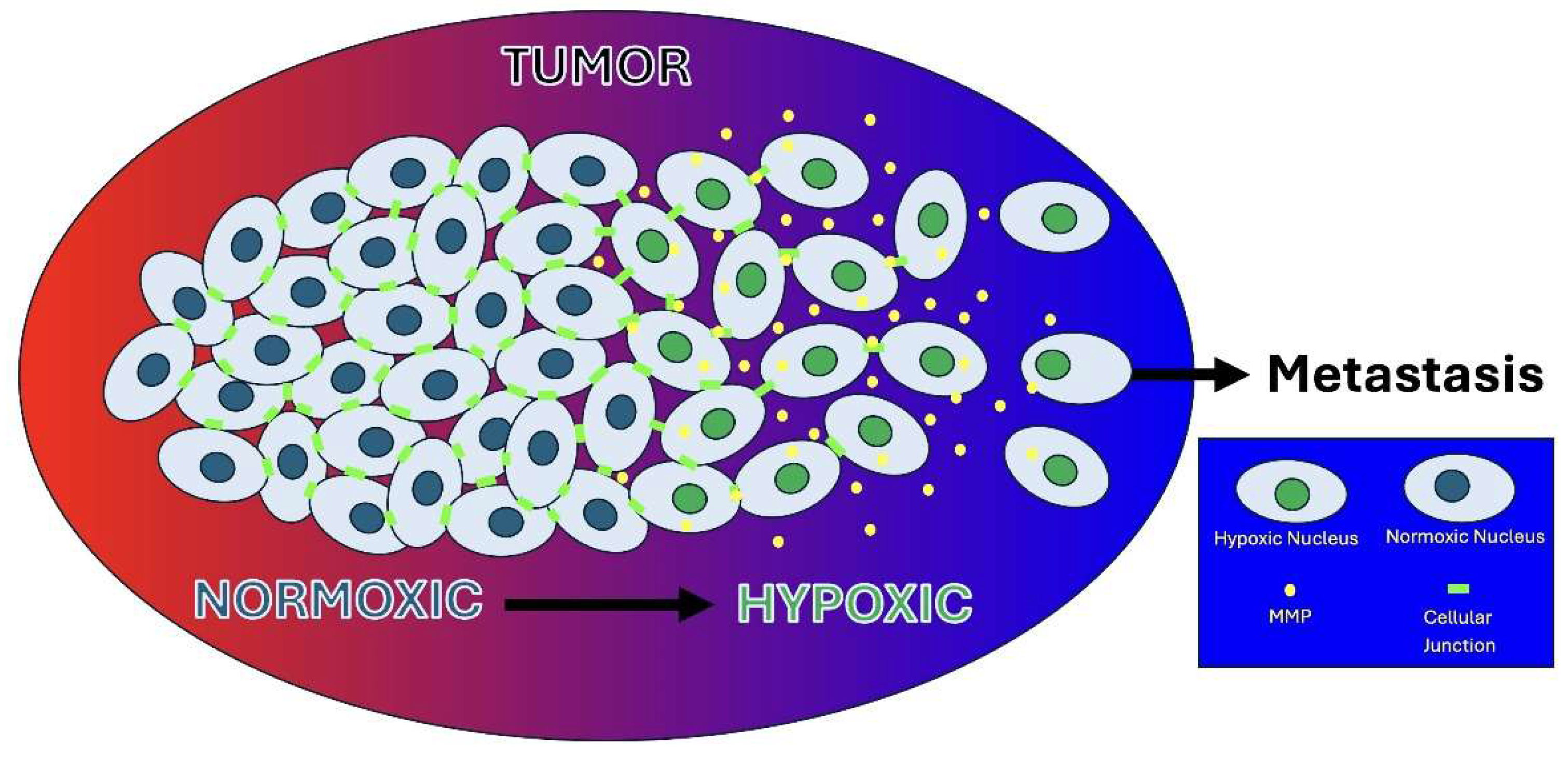

Hypoxia-Induced GJ Disruption, Heterogeneity, and Tumor Invasion

Hypoxia-induced reduction in GJIC hinders the coordinated behavior of cells, including synchronized contraction in cardiac tissue and apoptotic signaling in damaged cells. In cancer, the loss of GJIC isolates cells from their neighbors, disrupting intercellular communication and leading to uncontrolled cell growth and aberrant survival. This isolation allows subpopulations of cancer cells to adapt differently to the hypoxic TME, gaining survival advantages and contributing to cellular heterogeneity [

65].

The hypoxia-driven intratumoral heterogeneity, characterized by phenotypic diversity within a population of tumor cells, arises from the differences in oxygenation levels between cells in the same tissue. The oxygenation disparities lead to varying biological responses among tumor cell subpopulations as well as influences their interactions with signaling molecules such as growth factors. As a result, some subpopulations undergo proliferation, while others remain quiescent. This heterogeneity ultimately impairs treatment efficacy, making it more challenging to target the tumor cells due to distinct adaptive mechanisms of cell subpopulations to therapies [

66,

67,

68,

69,

70].

Importantly, this phenotypic diversity within the TME, arising from gap junction dysfunction, creates subpopulations with varying invasion potential. Hypoxia-induced intratumoral heterogeneity leads to heterogeneous EMT states, resulting in a spectrum of epithelial and mesenchymal phenotypes with high plasticity. This plasticity allows tumor cells to switch between epithelial and mesenchymal states, enhancing their adaptability in response to changing conditions [

71,

72]. With the compromised integrity of the TME, highly motile and invasive tumor cells can easily breach the basement membrane and invade surrounding tissues, as observed in glioblastomas and breast cancers [

60,

73].

During this invasion, tumor cells actively interact with and remodel the extracellular matrix (ECM). By secreting matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), invasive cells degrade ECM components, creating pathways for migration and metastasis. This ECM remodeling not only facilitates tumor invasion but also alters the structural and biochemical properties of the TME, further promoting tumor progression and therapeutic resistance [

74].

ECM remodeling

Hypoxia within the TME drives ECM remodeling through the activation of HIFs, significantly altering the structure and function of ECM components [

27]. The ECM, a dynamic and multifaceted support system, provides structural integrity and biochemical regulation to cells within their niche. Acting as a physical scaffold, it ensures proper tissue structure, and additionally supports key processes like migration, differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis by interacting with integrins and modulating the cell behavior [

5,

6].

Under normal physiological conditions, the ECM undergoes controlled remodeling as part of essential processes such as development and tissue repair, with proteolytic activity terminated once the necessary process is complete [

2,

8]. However, in pathological conditions such as hypoxia, this balance is disrupted due to activation of HIFs [

27]. These factors, particularly HIF-1α, not only directly enhance the transcription of MMPs, but also indirectly contribute to MMP upregulation by stimulating neighboring host cells to secrete cytokines and growth factors, resulting in further overproduction of MMPs [

24]. The overexpression of MMPs lead to excessive proteolysis in the ECM, where these enzymes degrade and reorganize ECM components, causing localized alterations in alignment of ECM fibers [

2,

21,

75]. These structural changes disturb tissue homeostasis, fostering a microenvironment favorable to tumor progression (

Figure 2).

Introduction to MMPs

MMPs are a group of endopeptidase enzymes that are largely responsible for the cleavage of the proteins in the ECM [

2]. This family of enzymes is heavily dependent on zinc and calcium for their enzymatic function [

1,

76]. MMPs can exist as either membrane-bound proteases or secreted enzymes and they are classified based on their structural features and substrate specificity. MMPs include collagenases, gelatinases, metalloelastases, stromelysins and matrilysins [

2,

28]. MMPs are initially produced in an inactive zymogen forms (pro-MMPs) and must be activated through the cleavage of their propeptide domain, a process often mediated by other proteases, including enzymes from their own family, such as MMP-14. The activation, that is carried out through the removal of their propeptide, exposes the active sites and enables the enzyme to carry out its catalytic function [

28].

Under normal physiological conditions, MMP activity is tightly regulated and localized to prevent unnecessary tissue damage. Their regulation occurs at multiple levels, including transcriptional control, post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation and glycosylation), pro-enzyme activation, inhibition by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), and through interaction with cell surface receptors [

25,

28].

Relevant MMPs

Collagenases, a subgroup of MMPs including MMP-1, -8, -13, and -18, are specifically involved in degrading fibrillar collagens such as types I, II, and III. These collagens are abundant in the stromal ECM (also known as interstitial ECM) and provide intercellular support and tensile strength in the tissues [

22]. Their degradation destabilizes the structure of the ECM, which can result in weakened tissue integrity, enhanced cancer cell invasiveness, and the release of bioactive molecules such as growth factors and cytokines, further promoting tumor progression and metastasis [

77].

The gelatinase subgroup, comprising MMP-2 (gelatinase A) and MMP-9 (gelatinase B), is among the most extensively studied MMPs in the context of ECM remodeling and cancer progression [

21]. These enzymes specialize in degrading gelatin and different collagens, including types I, IV, V, VII, IX, X, and XI [

22]. Their specificity for type IV collagen, a critical component of the ECM basement membrane, allows them to degrade this structural barrier, facilitating tumor invasion and migration. MMP-9 plays a distinct role in cancer progression by not only degrading ECM components but also releasing bioactive molecules, such as growth factors and cytokines, which further promote metastatic processes [

25].

Stromelysins, including MMP-3, MMP-10, and MMP-11, share the same domain organization as collagenases but lack the ability to cleave interstitial collagen. They target other ECM components such as proteoglycans, laminin, and fibronectin. MMP-3 and MMP-10 being closely related in structure and substrate specificity, both play a critical role in activating pro-MMPs by cleaving their propeptide domains, thereby amplifying the ECM remodeling [

28].

Matrilysins, comprising MMP-7 and MMP-26, are the smallest out of the MMPs due to their lack of the hemopexin domain. Despite their size, they have a wide substrate specificity, targeting an extensive range of ECM and non-ECM proteins [

28]. They directly contribute to ECM degradation by targeting non-fibrillar ECM components, such as laminin and fibronectin. Additionally, MMP-26 is able to activate MMP-9, which is a powerful mediator of tumor progression and metastasis [

22].

Membrane-type MMPs (also referred to as MT-MMPs), such as MMP-14 (or MT1-MMP), are bound to the cell surface and specialize in proteolysis near the cell membrane, also known as pericellular matrix. This region of the ECM provides a protective microenvironment for cells, shielding them from harmful physical factors while facilitating signal transmission between the ECM and cell surface receptors [

2]. Membrane-type MMPs degrade stromal collagens and activate zymogen MMPs, such as pro-MMP-2 and pro-MMP-13, thus indirectly amplifying proteolytic activity in the TME.

Biological Relevance of MMPs

MMPs play a crucial role in physiological processes such as tissue remodeling, repair, embryogenesis and angiogenesis [

14]. A key feature of MMPs is their combined ability to degrade nearly all components of the ECM, with each subgroup specializing in distinct substrates to collectively facilitate extensive ECM reorganization [

21]. Their ability to degrade ECM components for the purposes of remodeling is useful in physiological processes, yet can be detrimental, in the context of tumor development and progression. The overexpression of MMPs in the TME disrupts ECM homeostasis, leading to enhanced communication between neighboring tumor cells and promoting malignant processes such as cancer invasion, migration, and metastasis [

14].

The mechanism by which MMPs are overexpressed in tumors is linked to hypoxic conditions, where hypoxia regulates the expression and activity of MMPs through HIF-dependent and other signaling pathways. Hypoxia not only influences MMP activity directly by upregulating or downregulating their function but also modulates their activity indirectly by affecting the expression of TIMPs [

78]. A hypoxic environment has been associated with decreased levels of TIMPs in the TME, leading to an imbalance in the MMP-to-TIMP ratio. This disruption enhances MMP activity at the tumor site, making ECM degradation more likely and promoting metastatic activity within the tissue [

78,

79].

While the ability of MMPs to degrade ECM components is highly significant in relation to tumor metastasis, it does not solely account for the diverse effects these enzymes exert on the TME. MMPs have also been shown to act on non-matrix substrates, such as chemokines, growth factors and receptors, adhesion molecules, and apoptotic mediators [

78,

80]. These interactions elicit cellular responses that provide an environment optimal for tumor progression and, in combination with the ability of MMPs to degrade ECM proteins, contribute to the creation of a microenvironment that heavily supports cancer cell metastasis [

79].

Invasion & Migration

Invasion and migration of cancer cells, which are the key steps towards establishing metastasis, rely heavily on ECM remodeling, basement membrane degradation, as well as EMT [

25,

79]. EMT is facilitated within the TME due to the stabilization of HIF-1a levels by hypoxic conditions, which drives the expression of EMT-associated transcription factors, such as Snail, Twist, and ZEB [

79,

81]. These factors suppress epithelial markers like E-cadherin while upregulating mesenchymal markers like N-cadherin and vimentin, which leads to a significant reduction of cell-to-cell adhesion, giving the cells an ability to detach from the primary tumor site, invade surrounding tissue and initiate metastatic dissemination [

43,

80].

Consequently, once they invade, mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) enables the cancer cells to regain epithelial traits, anchor and proliferate at a new, secondary site. This intricate interplay between the two transitions allows tumor cells to successfully metastasize and establish secondary tumors, driving cancer progression and complicating treatment strategies. The ability of tumor cells to proliferate at secondary sites arises from the process of reoxygenation, which occurs when they leave the hypoxic environment of the primary tumor site. Reoxygenation disrupts the previously stable levels of HIF-1a, reversing EMT and enabling MET. By reacquiring an epithelial phenotype, these cells regain the ability to anchor and multiply, ultimately forming secondary tumors [

44,

78].

However, as these migrated tumor cells rapidly proliferate at a secondary site, they outgrow their local blood supply once again, leading to hypoxia. Furthermore, this hypoxic environment drives angiogenesis to meet the increased oxygen and nutrient demands of the growing secondary tumor.

Hypoxia and Cancer Angiogenesis

Hypoxia, a major trigger for angiogenetic response, drives the formation of new blood vessels by activating molecular pathways that stimulate angiogenesis, while simultaneously suppressing the immune response. A central player in this process is a pro-angiogenic factor, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), along with its receptors (VEGFRs), which are strong mediators of neovasculature formation and are upregulated in most cancers [

68,

82].

In addition to VEGF, hypoxia also induces the expression of inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS), leading to increased production of Nitric Oxide (NO). NO is a critical mediator of hypoxia-induced angiogenesis, working with VEGF to promote neovascularization. In addition, VEGF modulates the immune response [

83,

84].

HIF-1 tightly regulates VEGF, such that under low oxygen conditions, its subunit HIF-1α stabilizes and binds to the VEGF gene, triggering its expression [

85]. VEGF primarily interacts with VEGFR-2, a receptor on endothelial cells, to promote their development, migration and increased vascular permeability [

76]. Through VEGFR-2 activation, VEGF stimulates key signaling pathways such as PI3K-Akt and MAPK, which enhance cell survival and proliferation. By sustaining blood vessel formation, tumors ensure continuous supply of oxygen and nutrients, supporting the growth of cancer cells [

86].

The neovasculature in tumors is often abnormal and leaky, yet it still facilitates oxygen and essential nutrient delivery to the tumor site. As cancer cells rapidly divide, their metabolic demands increase, exacerbating hypoxia and further stimulating angiogenesis in an attempt to sustain oxygen and nutrient supply. This self-perpetuating cycle results in a tissue that remains highly hypoxic despite its extensive yet inefficient vascular network [

82,

86].

- 2.

The Role of iNOS and NO in Tumor Progression

In hypoxic conditions, iNOS expression is upregulated, leading to increased production of nitric oxide (NO), a molecule with a complex and dual role in cancer progression. The impact of NO depends on its concentration, its duration of exposure to cells, as well as TME conditions [

87]. At controlled levels, NO promotes angiogenesis by increasing vascular permeability and amplifying VEGF activity. However, excessive NO synthesis can be cytotoxic, highlighting the importance of tight regulation of iNOS activity [

87,

88].

In most cancers, iNOS upregulation has been associated with pro-tumorigenic effects, where it promotes metastasis through TME remodeling [

87,

88,

89,

90]. However, under certain conditions, such as excessive NO concentrations that induce oxidative stress or immune activation, iNOS overexpression has been linked with better clinical outcomes[

90]. Despite these context-dependent anti-tumorigenic effects, iNOS overexpression is more commonly associated with pro-tumorigenic effects, including angiogenesis, immune suppression, and metastasis [

88].

- 3.

COX-2 as a Driver of Angiogenesis and Inflammation

COX-2, an inflammatory enzyme, is frequently overexpressed in tumors. In hypoxic conditions, it promotes angiogenesis by enhancing the effects of VEGF [

91]. Furthermore, by inhibiting anti-cancer immune responses and enhancing the activity of regulatory T cells, COX-2 aids further tumor development by helping it evade the immune system. Its overexpression has been associated with more aggressive tumors and poorer prognoses, particularly in colorectal cancer. Selective COX-2 inhibitors, such as celecoxib, have shown promise in reducing tumor growth and angiogenesis, especially when combined with VEGF-targeting therapies [

91].

- 4.

Interactions Between VEGF, iNOS, and COX-2

COX-2, iNOS, and VEGF operate in a feedback loop to sustain angiogenesis and drive tumor progression. VEGF induces the synthesis of iNOS, which then raises NO levels and subsequently promotes angiogenesis and modulates the immune microenvironment to support cancer progression [

92].

Simultaneously, iNOS interacts with COX-2 to create a pro-inflammatory, tumor-promoting environment. COX-2 not only amplifies VEGF signaling, but also increases the production of pro-angiogenic prostaglandins, further reinforcing continuous angiogenesis [

92,

93]. These intricate interactions between various pathways underscore the necessity of combination therapies that target multiple pathways to effectively disrupt this cycle [

94].

Immunological Impact of Hypoxia in the Tumor Microenvironment

TME hypoxia significantly influences immune responses by suppressing anti-tumor immunity and altering immune cell function, thereby promoting tumor growth and fostering treatment resistance [

95,

96]. HIFs regulate the production of various immune-related molecules and induce metabolic reprogramming in tumor cells, generating acidic byproducts that inhibit immune cell activity and reduce the capacity for immune surveillance [

57].

Noman and coauthors reported that HIF-1α directly drives the expression of programmed cell death ligand (PD-L1), thus helping tumor cells evade immune surveillance. They further showed that blocking PD-L1 under hypoxic conditions can re-energize T-cell activity [

3]. HIFs further decrease anti-tumor immune responses by recruiting and activating immunosuppressive cells, such as regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells [

27,

57,

97].

The impact of hypoxia extends beyond tumor cells, directly compromising the activity of immune effectors. Low oxygen levels impair the function of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and natural killer (NK) cells, reducing their cytolytic activity, survival, and proliferation [

97]. Additionally, hypoxia disrupts dendritic cell maturation and antigen presentation, hindering the activation of adaptive immune responses [

98].

These adaptations protect tumor cells from immune-induced cell death and create an immunosuppressive TME that not only supports tumor growth and metastasis but also greatly complicates the efficacy of immunotherapies. Thus, targeting hypoxia-induced pathways presents as a promising strategy to improve therapeutic outcomes. Preclinical and early clinical studies have demonstrated the potential of combining hypoxia-modulating therapies with immune checkpoint inhibitors to overcome hypoxia-induced immunosuppression. Such synergistic approaches may help restore immune cell function and improve patient outcomes [

99]. Understanding the mechanisms by which hypoxia and HIFs drive immune evasion is essential for the development of innovative strategies to counteract these pathways and enhance the efficacy of immunotherapies.

Mobilizing Discoveries for Therapeutic Effect

In the last decade, the study of hypoxia’s impact on metabolism has greatly expanded, revealing nuanced regulatory mechanisms and their implications for diverse biological processes. Chan et al. demonstrated that targeting GLUT1, a glucose transporter often upregulated by HIF-1, could exploit the “Warburg effect” in renal cell carcinoma, suggesting a novel strategy for killing hypoxia-adapted tumor cells [

109]. Around the same time, Anwar et al. showed that inhibiting pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK), another key HIF target, reversed the glycolytic phenotype and curbed tumor progression [

110].

Kashfi et al. investigated how tumor-associated macrophages adapt their metabolism under hypoxia, adopting a glycolytic and often immunosuppressive profile that hinders effective antitumor immunity [

87]. These findings underscore that hypoxia not only refines the metabolic wiring of tumor cells but also reprograms the surrounding immune cells, complicating therapeutic intervention.

Resistance to Chemotherapy

Hypoxia facilitates tumor resistance and diminishes the efficacy of chemotherapy through several mechanisms. Hypoxic tumors often possess disorganized and leaky vasculature that limits the delivery of chemotherapeutic agents to the tumor core. This uneven drug distribution enables hypoxic cells to evade cytotoxic effects, which then often results in treatment failure [

1,

6,

7]. Hypoxia also upregulates the expression of drug efflux pumps, such as P-glycoprotein, via pathways mediated by HIF-1α, which actively transport drugs out of cells and reduce intracellular drug concentrations, thereby diminishing treatment efficacy [

86,

115].

Moreover, hypoxic tumor cells undergo metabolic reprogramming by shifting to anaerobic glycolysis and producing lactate as a byproduct. This metabolic adaptation reduces reliance on mitochondrial respiration, which renders therapies targeting oxidative metabolism less effective. This adaptation also supports the survival of cancer stem-like cells, which are inherently resistant to chemotherapy [

86,

116].

Thus, by altering the TME, hypoxia creates an immunosuppressive stroma, which shields tumor cells from immune-mediated cytotoxicity. This alteration reduces the efficacy of immunomodulatory chemotherapy and further complicates treatment strategies [

4,

86].

Resistance to Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy relies on the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) to induce DNA damage in cancer cells, however, hypoxia, reducing oxygen tension, directly impairs this process. ROS formation is diminished under hypoxic conditions and results in reduced efficacy of radiation therapy. In fact, tumor cells in hypoxic regions have been shown to be up to three times more resistant to radiation compared to normoxic cells [

94,

115,

117].

Beyond limiting ROS generation, hypoxia also induces signaling pathways that enhance the expression of DNA repair proteins and enable tumor cells to efficiently repair radiation-induced DNA damage. HIF-1α mediates this process by activating genes involved in homologous recombination and non-homologous end-joining pathways [

115,

116,

117]. Additionally, hypoxia induces cell cycle arrest by halting cells in the G1 phase, which is less susceptible to radiation-induced cytotoxicity, through the upregulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, such as p21 and p27 [

4,

86,

117].

And, since tumor hypoxia fluctuates spatially as well as temporally, it creates pockets of radioresistant cells. This heterogeneity complicates treatment planning while significantly reducing the efficacy of standard radiation therapy [

4,

118].

Examples of Tumor Types affected by Hypoxia

A key factor in the development and spread of breast cancer is hypoxic TME. By modifying gene expression, HIFs promote angiogenesis, attract stromal cells, and remodel the ECM, all of which aid in the motility of cancer cells. These pathways are especially important in aggressive breast cancer subtypes, such as triple-negative breast cancer [

105].

Circular RNA circWSB1, transcriptionally triggered by HIF1α in hypoxic settings, has also been recently established as an important regulator in breast cancer. By interfering with USP10-p53 interaction, it promotes p53 degradation, leading to accelerated tumor growth. Given its role in tumor progression, circWSB1 emerges as a promising therapeutic target and prognostic marker [

71,

73]. Targeting hypoxia-associated factors such as ECM-modifying enzymes and circWSB1 holds significant potential to prevent metastases and enhance outcomes in high-risk patients [

73].

- 2.

Metabolic Reprogramming in Hypoxia-Induced Colorectal Cancer:

The progression of colorectal cancer is influenced by the reprogramming of cysteine metabolism under hypoxia. ATF4, a crucial transcription factor, is activated by ROS in response to hypoxia, leading to the overexpression of cysteine and cystine transporters. This metabolic shift in increased cysteine availability fuels glutathione synthesis—a key antioxidant agent that neutralizes ROS and prevents ROS-induced cell death [

119]. Cancer cells heavily depend on this mechanism to survive in a challenging microenvironment.

However, this upregulation not only strengthens the tumor's antioxidant defenses, enabling cancer cells to neutralize ROS, but also enhances their ability to resist treatment-induced damage [

120]. Targeting this metabolic adaptation—through strategies such as inhibiting transporters, depleting cysteine, or disrupting glutathione synthesis—has emerged as a promising strategy for colorectal cancer treatment [

121].

- 3.

Hypoxia and Brain Metastases in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), hypoxia stimulates the NDR2 kinase pathway, which, in turn, promotes brain metastases. NDR2 activation that resulted from hypoxic environments' downregulation of Hippo signaling pathway components, increases tumor cells' capacity to spread and encourages amoeboid migration. NDR2 targeting has become a viable therapeutic approach to reduce brain metastases in NSCLC, providing a new way to intervene in hypoxia-driven metastatic processes [

2].

Therapeutic targeting

HIF-1α is an attractive therapeutic target since this subunit stands as a master regulator of cellular hypoxic response, orchestrating a complex adaptive mechanism in cancer biology. Several approaches can be explored, which include, but are not limited to, direct HIF-1α inhibitors, which are small molecules may target HIF-1α stability and/or transcriptional activity; upstream pathway inhibitors, which are compounds that modulate PHDs or other regulatory proteins; downstream effector targeting, in which case molecules inhibit HIF-1α target genes and their products; or combination approaches, where HIF-1α-targeted therapies are integrated, leading to improved efficacy of conventional treatments to overcome hypoxia-induced resistance [

14,

24,

27,

77,

121].

- 2.

Therapy aimed at gap junction restoration

Efforts to mitigate the effects of hypoxia on gap junctions include the use of connexin mimetic peptides, which are synthetic peptides that mimic the function of connexins and are able to restore GJC under hypoxic conditions. Another approach involves targeting HIF pathways to prevent the transcriptional downregulation of connexins [

61]. Additionally, antioxidants also help preserve gap junction function by preventing connexin degradation, protecting cells from hypoxia-induced loss of GJC. Emerging research further highlights the role of non-coding RNAs, such as microRNAs, in regulating connexin expression under hypoxia, presenting new promising therapeutic targets.

Conclusions and Future Directions

An understanding of the molecular basis of hypoxia-induced malignancies enables the development of effective and possibly tailored therapeutics. Under hypoxic conditions, HIFs drive the upregulation of key factors such as MMPs and VEGF, as well as many other signaling pathways which lead to ECM degradation, angiogenesis and overall disruption of the normal functioning of TME. Targeting these hypoxia-driven mechanisms not only holds the potential to inhibit tumor progression but also to overcome hypoxia-induced therapeutic resistance.

Future research should focus on clarifying the intricate relationships between these pathways and investigating combination therapies in order to improve patient outcomes. In particular, targeting HIF-1a signaling could help prevent gap junction disruption, inhibit EMT and reduce subsequent migration. Alternatively, inhibiting MMPs to disrupt ECM degradation may effectively block invasion and metastasis. Identifying synergistic approaches that complement each other holds promise to enhance treatment efficacy. Additionally, advances in biomarker-based therapeutic strategies, particularly those reflecting hypoxia-driven processes, may further enable more individualized and effective cancer treatments.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EMT |

Epithelial to mesenchymal transition |

| HIF1 a |

Hypoxia inducible factor 1 a |

| TME |

Tumor microenvironment |

| EMT |

Epithelial to mesenchymal transition |

| VEFG |

Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| iNOS |

Nitric oxide synthase |

| COX-2 |

Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| ECM |

Extracellular matrix |

| TME |

Tumor microenvironment |

| NO |

Nitric oxide |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| CTL |

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes |

| NK |

Natural Killer cells |

References

- Brahimi-Horn, M.C., J. Chiche, and J. Pouyssegur, Hypoxia and cancer. J Mol Med (Berl) 2007, 85, 1301–1307.

- Chen, Z. , et al. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.H. , et al. , Recent Research on Methods to Improve Tumor Hypoxia Environment. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020, 2020, 5721258. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, B.S. and M. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brahimi-Horn, M.C. and J. Pouyssegur, Hypoxia in cancer cell metabolism and pH regulation. Essays Biochem 2007, 43: 165-78.

- Chan, D.A. and A. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2007, 26, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, A. , et al. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001, 93, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, E.E. and G.L. Semenza, Hypoxia-inducible factors: cancer progression and clinical translation. J Clin Invest 2022, 132(11).

- Brahimi-Horn, C., E. Berra, and J. Pouyssegur, Hypoxia: the tumor's gateway to progression along the angiogenic pathway. Trends Cell Biol 2001, 11, S32-6.

- Span, P.N. and J. Semin Nucl Med 2015, 45, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, W.C. , et al. Nature 2002, 417, 975–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. , et al. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. and G. Mol Cell Biol 1992, 12, 5447–5454. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, B.P. , et al., Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1: A Novel Therapeutic Target for the Management of Cancer, Drug Resistance, and Cancer-Related Pain. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14(24).

- Zeng, W. , et al., Hypoxia and hypoxia inducible factors in tumor metabolism. Cancer Lett 2015, 356(2 Pt A): 263-7.

- Maxwell, P.H. , et al. Nature 1999, 399, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.J. , et al. Mol Cell Biol 2003, 23, 9361–9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaakkola, P. , et al. Science 2001, 292, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvietikova, I. , et al. Kidney Int 1997, 51, 564–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivan, M. , et al. Science 2001, 292, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W. , et al. Exp Mol Med 2004, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, N. , et al. EMBO J 2001, 20, 5197–5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yfantis, A. , et al., Transcriptional Response to Hypoxia: The Role of HIF-1-Associated Co-Regulators. Cells 2023, 12(5).

- Masoud, G.N. and W. Acta Pharm Sin B 2015, 5, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Y.M. and L. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimmino, F. , et al. BMC Med Genet 2019, 20, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Balamurugan, K. , HIF-1 at the crossroads of hypoxia, inflammation, and cancer. Int J Cancer 2016, 138, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infantino, V. , et al., Cancer Cell Metabolism in Hypoxia: Role of HIF-1 as Key Regulator and Therapeutic Target. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22(11).

- Eales, K.L., K. E. Hollinshead, and D.A. Tennant, Hypoxia and metabolic adaptation of cancer cells. Oncogenesis 2016, 5, e190.

- Paredes, F., H. C. Williams, and A. San Martin, Metabolic adaptation in hypoxia and cancer. Cancer Lett 2021, 502, 133-142.

- Kutova, O.M., A. D. Pospelov, and I.V. Balalaeva, The Multifaceted Role of Connexins in Tumor Microenvironment Initiation and Maintenance. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12(2).

- Hapke, R.Y. and S. Cancer Lett 2020, 487, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.G. , et al. Int J Oncol 2020, 56, 642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goodenough, D.A. and D. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2009, 1, a002576. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H. , et al. Mol Med Rep 2017, 15, 1823–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotini, M. and R. Dev Biol 2015, 401, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., F. M. Acosta, and J.X. Jiang, Gap Junctions or Hemichannel-Dependent and Independent Roles of Connexins in Fibrosis, Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transitions, and Wound Healing. Biomolecules 2023, 13(12).

- Nielsen, M.S. , et al. Compr Physiol 2012, 2, 1981–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, H.K., J. L. Maiers, and K.A. DeMali, Interplay between tight junctions & adherens junctions. Exp Cell Res 2017, 358, 39-44.

- Troyanovsky, S.M. , Adherens junction: the ensemble of specialized cadherin clusters. Trends Cell Biol 2023, 33, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, T. , et al. Am J Pathol 2003, 163, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M. , et al. Exp Cell Res 2018, 368, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indra, I. , et al. J Invest Dermatol 2013, 133, 2546–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amack, J.D. , Cellular dynamics of EMT: lessons from live in vivo imaging of embryonic development. Cell Commun Signal 2021, 19, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyuno, D. , et al. , Role of tight junctions in the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2021, 2021, 1863, 183503. [Google Scholar]

- Corallino, S. , et al. Front Oncol 2015, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heerboth, S. , et al. Clin Transl Med 2015, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. , et al. Cancer Cell Int 2023, 23, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J., Y. Chen, and A. BMC Womens Health 2024, 24, 293. [Google Scholar]

- Tabaries, S. and P. Oncogene 2017, 36, 1176–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Osanai, M. , et al. Pflugers Arch 2017, 469, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.W. , et al. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 1051497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattern, J. , et al. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 12540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.H. , et al., Interplay between desmoglein2 and hypoxia controls metastasis in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118(3).

- Perl, A.L., J. L. Pokorny, and K.J. Green, Desmosomes at a glance. J Cell Sci 2024, 137(12).

- Najor, N.A. , Desmosomes in Human Disease. Annu Rev Pathol 2018, 13, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustin, R.C., G. M. Delgoffe, and Y.G. Najjar, Characteristics of the Tumor Microenvironment That Influence Immune Cell Functions: Hypoxia, Oxidative Stress, Metabolic Alterations. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12(12).

- Huang, Z. , et al., Hypoxia makes EZH2 inhibitor not easy-advances of crosstalk between HIF and EZH2. Life Metab 2024, 3(4).

- Wang, J. , et al. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024, 11, e2303904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.J. , et al. J Cell Mol Med 2021, 25, 10663–10673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.K. , et al. Int J Mol Sci 2014, 16, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M. , et al. Cell Commun Signal 2023, 21, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peracchia, C. , Calcium Role in Gap Junction Channel Gating: Direct Electrostatic or Calmodulin-Mediated? Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25(18).

- Rodriguez-Candela Mateos, M. , et al. , Insights into the role of connexins and specialized intercellular communication pathways in breast cancer: Mechanisms and applications. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2024, 2024, 1879, 189173. [Google Scholar]

- Arabzadeh, A. , et al. Cancer Cell Int 2021, 21, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hompland, T., C. S. Fjeldbo, and H. Lyng, Tumor Hypoxia as a Barrier in Cancer Therapy: Why Levels Matter. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13(3).

- Gillies, R.J. , et al. Neoplasia 1999, 1, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melincovici, C.S. , et al. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2018, 59, 455–467. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K. and J.A. Cancelas, Gap Junctions in the Bone Marrow Lympho-Hematopoietic Stem Cell Niche, Leukemia Progression, and Chemoresistance. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(3).

- Zefferino, R. , et al., Gap Junction Intercellular Communication in the Carcinogenesis Hallmarks: Is This a Phenomenon or Epiphenomenon? Cells 2019, 8(8).

- Li, D. , et al. Cell Prolif 2023, 56, e13423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, M.K. and T. Celia-Terrassa, Dynamics of Phenotypic Heterogeneity Associated with EMT and Stemness during Cancer Progression. J Clin Med 2019, 8(10).

- Yang, R. , et al. Mol Cancer 2022, 21, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, K.M. , et al. Int J Exp Pathol 2019, 100, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.G. , et al. Int J Oncol 2019, 55, 845–859. [Google Scholar]

- Apte, R.S., D. S. Chen, and N. Ferrara, VEGF in Signaling and Disease: Beyond Discovery and Development. Cell 2019, 176, 1248-1264.

- Giaccia, A., B. G. Siim, and R.S. Johnson, HIF-1 as a target for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2003, 2, 803–811.

- Amar, S., L. Smith, and G.B. Fields, Matrix metalloproteinase collagenolysis in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2017, 1864, 1940-1951.

- Jablonska-Trypuc, A., M. Matejczyk, and S. Rosochacki, Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), the main extracellular matrix (ECM) enzymes in collagen degradation, as a target for anticancer drugs. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2016, 31, 177-183.

- Huang, H. , Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) as a Cancer Biomarker and MMP-9 Biosensors: Recent Advances. Sensors (Basel) 2018, 18(10).

- Merchant, N. , et al. Carcinogenesis 2017, 38, 766–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elebiyo, T.C. , et al. Cancer Treat Res Commun 2022, 32, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkov, M.I., C. T. Lee, and C.T. Taylor, Regulation of the Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF) by Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines. Cells 2021, 10(9).

- Islam, S.M.T. , et al. Immunology 2021, 164, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, J.A. , et al. Mol Cell Biol 1996, 16, 4604–4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muz, B. , et al. Hypoxia (Auckl) 2015, 3, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashfi, K., J. Kannikal, and N. Nath, Macrophage Reprogramming and Cancer Therapeutics: Role of iNOS-Derived NO. Cells 2021, 10(11).

- Belgorosky, D. , et al. J Mol Med (Berl) 2020, 98, 1615–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, V. , et al. Antioxid Redox Signal 2019, 30, 1124–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannini, F., K. Kashfi, and N. Nath, The dual role of iNOS in cancer. Redox Biol 2015, 6, 334-343.

- Wang, D. and R. Oncogene 2010, 29, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Batalla, I. , et al. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 6341–6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paz Linares, G.A. , et al., Prostaglandin E2 Receptor 4 (EP4) as a Therapeutic Target to Impede Breast Cancer-Associated Angiogenesis and Lymphangiogenesis. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13(5).

- Wang, H. , et al., Hypoxic Radioresistance: Can ROS Be the Key to Overcome It? Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11(1).

- Fu, Z. , et al., Tumour Hypoxia-Mediated Immunosuppression: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches to Improve Cancer Immunotherapy. Cells 2021, 10(5).

- Westendorf, A.M. , et al. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017, 41, 1271–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazon, A. , et al. Immunity 2014, 41, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, M.Z. , et al. J Exp Med 2014, 211, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuillefroy de Silly, R., P. Y. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1232236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O. , On the origin of cancer cells. Science 1956, 123, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O. , On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science 1956, 124, 269–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, Y.G. , et al. Exp Hematol 2002, 30, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W. , et al. Cell Metab 2006, 3, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papandreou, I. , et al. Cell Metab 2006, 3, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A. , et al. Int J Biol Sci 2022, 18, 3019–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaelin, W.G., Jr. and P. Mol Cell 2008, 30, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denko, N.C. , Hypoxia, HIF1 and glucose metabolism in the solid tumour. Nat Rev Cancer 2008, 8, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majmundar, A.J., W. J. Wong, and M.C. Simon, Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell 2010, 40, 294-309.

- Chan, D.A. , et al. Sci Transl Med 2011, 3, 94ra70. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, S. , et al. , Targeting pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase signaling in the development of effective cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2021, 2021, 1876, 188568. [Google Scholar]

- McNair, A.J. , et al. Pulm Circ 2020, 10, 2045894020937134. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar, A. and A. Cell Biochem Funct 2012, 30, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Tillo, E. , et al. Cell Death Differ 2014, 21, 247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Monga, S.P. , beta-Catenin Signaling and Roles in Liver Homeostasis, Injury, and Tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 1294–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouleftour, W. , et al. Med Sci Monit 2021, 27, e934116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kabakov, A.E. and A.O. Yakimova, Hypoxia-Induced Cancer Cell Responses Driving Radioresistance of Hypoxic Tumors: Approaches to Targeting and Radiosensitizing. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13(5).

- Menegakis, A. , et al., Resistance of Hypoxic Cells to Ionizing Radiation Is Mediated in Part via Hypoxia-Induced Quiescence. Cells 2021, 10(3).

- Zdrowowicz, M. , et al., Influence of Hypoxia on Radiosensitization of Cancer Cells by 5-Bromo-2'-deoxyuridine. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23(3).

- Hong, S.E. , et al. Anticancer Res 2020, 40, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, B. , et al. Biomaterials 2021, 277, 121110. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R. , et al., Action Sites and Clinical Application of HIF-1alpha Inhibitors. Molecules 2022, 27(11).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).