Submitted:

03 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

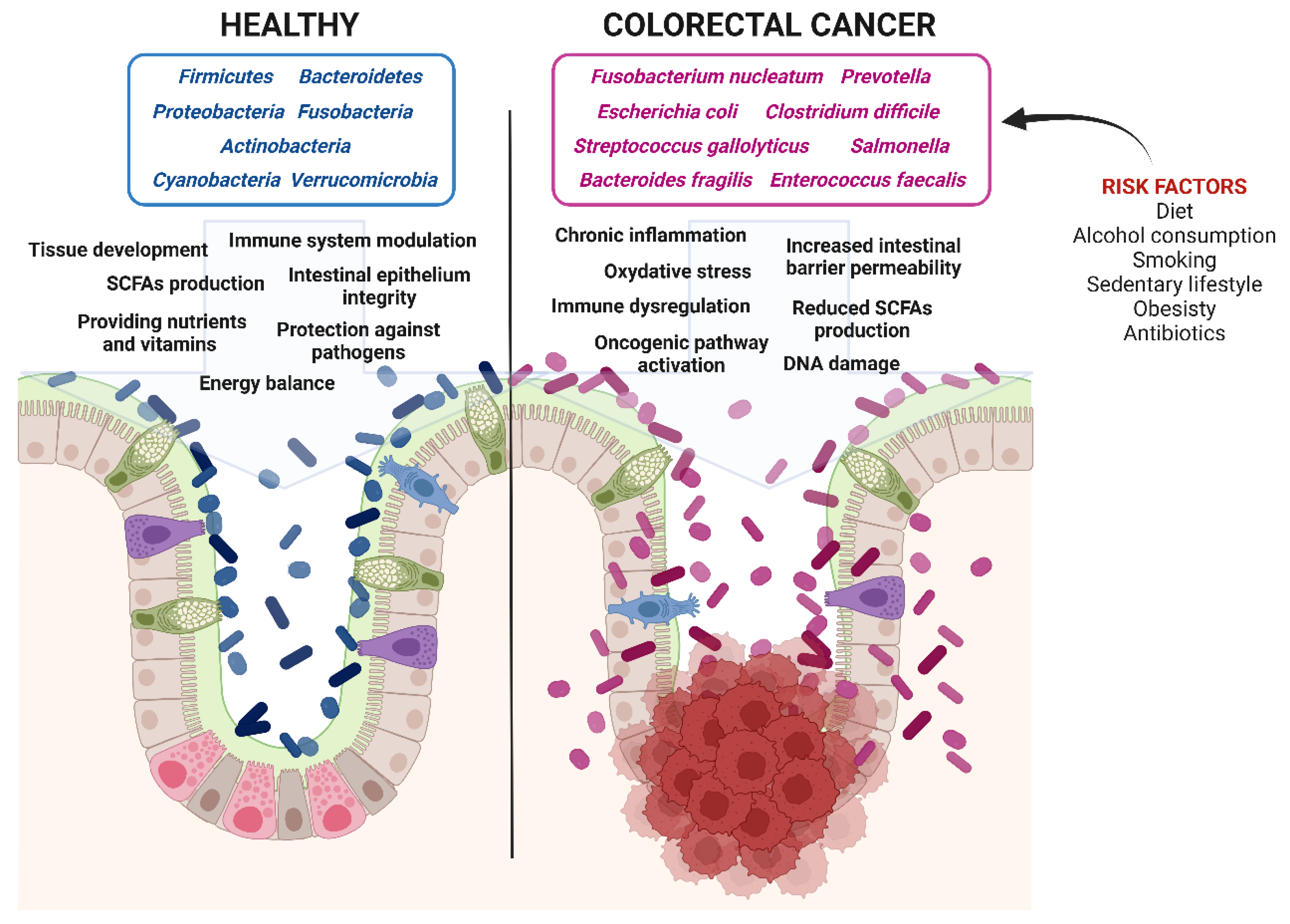

You are already at the latest version

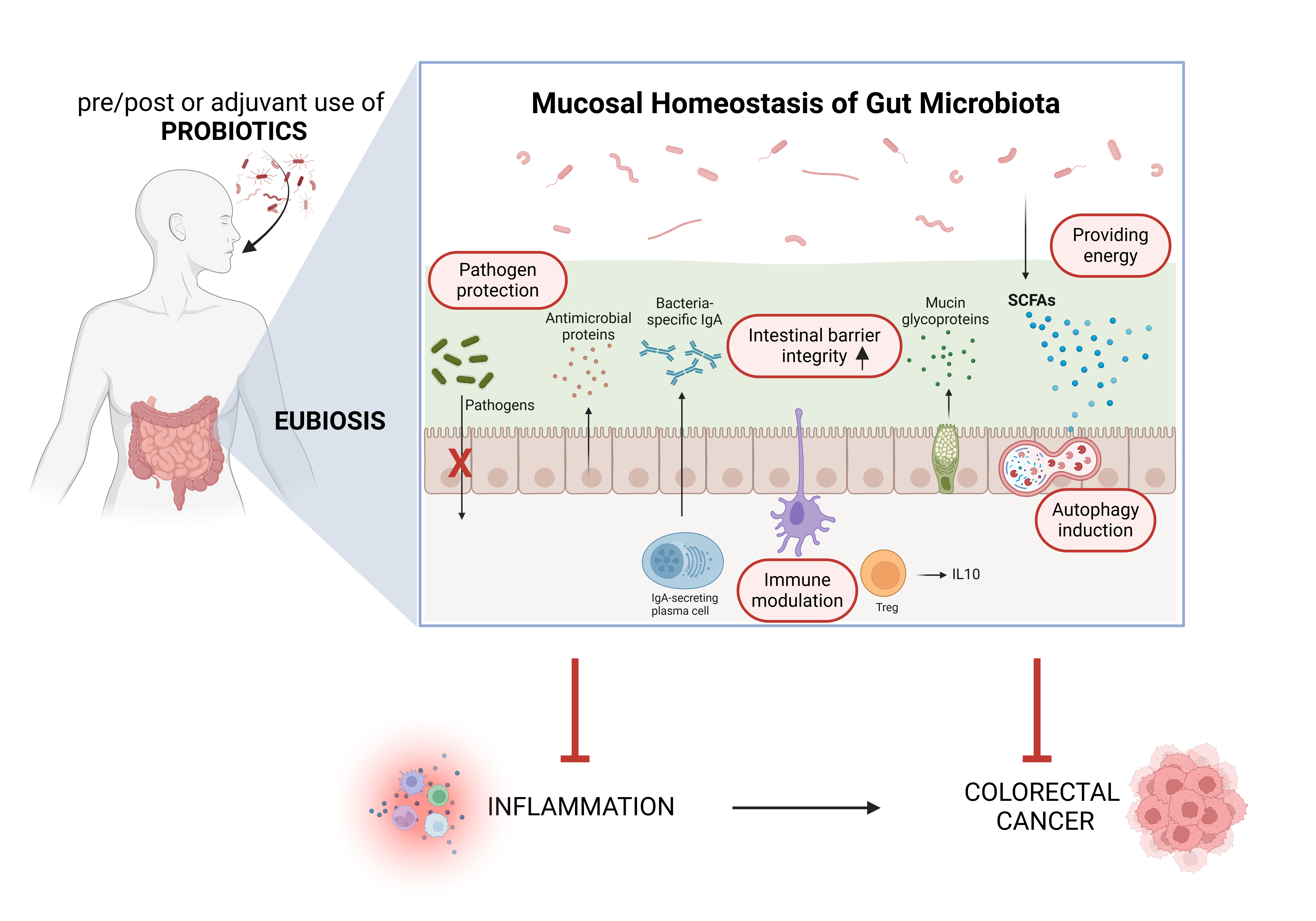

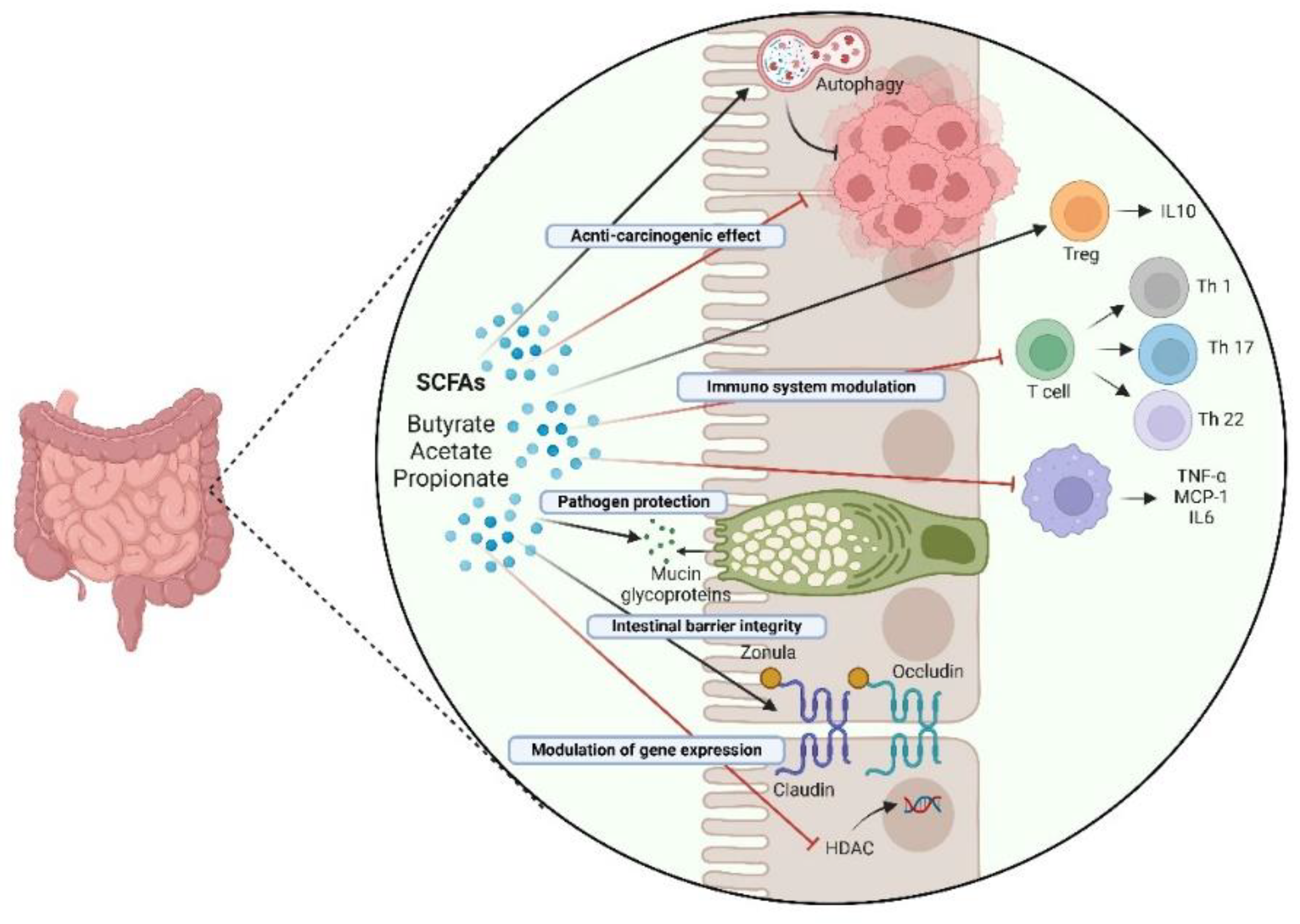

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Prevention and Therapy at a Glance

1. Colorectal Cancerogenesis: The Role of Genetics and Epigenetics

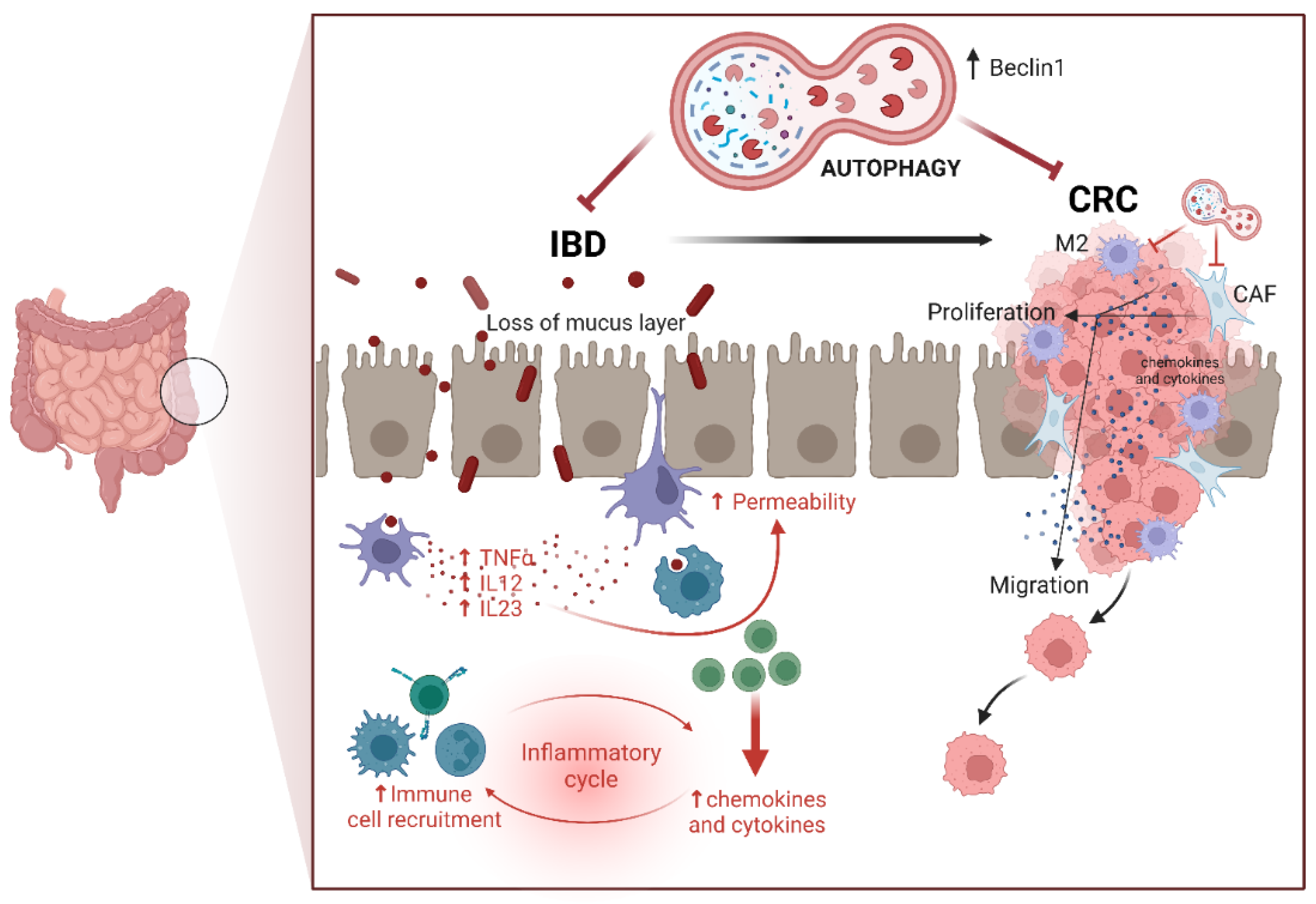

2. Colorectal Cancerogenesis: The Role of Autophagy

3. Colorectal Cancerogenesis: The Role of Inflammation

4. Dysbiosis and Colorectal Cancerogenesis: The Role of Diet and Microbiota

5. Probiotics and Their Metabolites for Prevention and as Adjuvant Therapeutics in Colorectal Cancer: Impact on Inflammation and Autophagy

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, S.; Karuniawati, H.; Jairoun, A.A.; Urbi, Z.; Ooi, D.J.; John, A.; Lim, Y.C.; Kibria, K.M.K.; Mohiuddin, A.M.; Ming, L.C.; et al. Colorectal Cancer: A Review of Carcinogenesis, Global Epidemiology, Current Challenges, Risk Factors, Preventive and Treatment Strategies. Cancers 2022, 14, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Gini, A.; Lorenzoni, V.; Cabasag, C.J.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Murphy, N.; Bray, F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut 2023, 72, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshandel, G.; Ghasemi-Kebria, F.; Malekzadeh, R. Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention. Cancers 2024, 16, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruya, A.; Kuwahara, A.; Saito, Y.; Yamaguchi, H.; Tsubo, T.; Suga, S.; Inai, M.; Aoki, Y.; Takahashi, S.; Tsutsumi, E.; et al. Ecophysiological consequences of alcoholism on human gut microbiota: implications for ethanol-related pathogenesis of colon cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Schwartz, B. Interactions between Dietary Antioxidants, Dietary Fiber and the Gut Microbiome: Their Putative Role in Inflammation and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, V.A.; Gheorghe, G.; Georgescu, T.F.; Buica, V.; Catanescu, M.-S.; Cercel, I.-A.; Budeanu, B.; Budan, M.; Bacalbasa, N.; Diaconu, C. Exploring the Role of the Gut Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer Development. Gastrointest. Disord. 2024, 6, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, L.; Vilar, E.; Tavtigian, S.V.; Stoffel, E.M. Genetic predisposition to colorectal cancer: syndromes, genes, classification of genetic variants and implications for precision medicine. J. Pathol. 2018, 247, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantini, M.C.; Guadagni, I. From inflammation to colitis-associated colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: Pathogenesis and impact of current therapies. Dig. Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadlallah, H.; El Masri, J.; Fakhereddine, H.; Youssef, J.; Chemaly, C.; Doughan, S.; Abou-Kheir, W. Colorectal cancer: Recent advances in management and treatment. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 15, 1136–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Gautam, V.; Sandhu, A.; Rawat, K.; Sharma, A.; Saha, L. Current and emerging therapeutic approaches for colorectal cancer: A comprehensive review. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 15, 495–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.-H.; Chen, Y.-X.; Fang, J.-Y. Comprehensive review of targeted therapy for colorectal cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, M.M.; Carriço, M.; Capelas, M.L.; Pimenta, N.; Santos, T.; Ganhão-Arranhado, S.; Mäkitie, A.; Ravasco, P.; M, A. The impact of pre-, pro- and synbiotics supplementation in colorectal cancer treatment: a systematic review. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1395966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, E.R.; Vogelstein, B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell 1990, 61, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Goel, A.; Chung, D.C. Pathways of Colorectal Carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Tian, Y.; Deng, Z.; Yang, F.; Chen, E. Epigenetic Alteration in Colorectal Cancer: Potential Diagnostic and Prognostic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mármol, I.; Sánchez-De-Diego, C.; Pradilla Dieste, A.; Cerrada, E.; Rodriguez Yoldi, M. Colorectal Carcinoma: A General Overview and Future Perspectives in Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.; Menko, F.H.; Brosens, L.A.; Giardiello, F.M.; Offerhaus, G.J. Establishing a clinical and molecular diagnosis for hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes: Present tense, future perfect? Gastrointest. Endosc. 2014, 80, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimbath, J.D.; Giardiello, F.M. Genetic testing and counselling for hereditary colorectal cancer. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 16, 1843–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, D.L.; Axilbund, J.; Baxter, M.; Hylind, L.M.; Romans, K.; Griffin, C.A.; Cruz–Correa, M.; Giardiello, F.M. Rapid Development of Colorectal Neoplasia in Patients With Lynch Syndrome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 9, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonk, T.; Humeny, A.; Sutter, C.; Gebert, J.; Doeberitz, M.v.K.; Becker, C.-M. Molecular diagnosis of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): genotyping of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) alleles by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Clin. Biochem. 2002, 35, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiersbach, K.B.; Samowitz, W.S. Microsatellite Instability and Colorectal Cancer. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2011, 135, 1269–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magzoub, M.M.; Prunello, M.; Brennan, K.; Gevaert, O. The impact of DNA methylation on the cancer proteome. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1007245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colussi, D.; Brandi, G.; Bazzoli, F.; Ricciardiello, L. Molecular Pathways Involved in Colorectal Cancer: Implications for Disease Behavior and Prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 16365–16385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecarpentier, Y.; Schussler, O.; Hébert, J.-L.; Vallée, A. Multiple Targets of the Canonical WNT/β-Catenin Signaling in Cancers. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Gan, W.-J. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway in the Development and Progression of Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2023, ume 15, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmand, L.; Darvishi, B.; Majidzadeh-A, K.; Ansari, A.M. Naturally occurring compounds acting as potent anti-metastatic agents and their suppressing effects on Hedgehog and WNT/β-catenin signalling pathways. Cell Prolif. 2016, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, K.T.; Stringari, C.; Sprowl-Tanio, S.; Wang, K.; TeSlaa, T.; Hoverter, N.P.; McQuade, M.M.; Garner, C.; A Digman, M.; A Teitell, M.; et al. Wnt signaling directs a metabolic program of glycolysis and angiogenesis in colon cancer. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 1454–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprowl-Tanio, S.; Habowski, A.N.; Pate, K.T.; McQuade, M.M.; Wang, K.; Edwards, R.A.; Grun, F.; Lyou, Y.; Waterman, M.L. Lactate/pyruvate transporter MCT-1 is a direct Wnt target that confers sensitivity to 3-bromopyruvate in colon cancer. Cancer Metab. 2016, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaeger, R.; Chatila, W.K.; Lipsyc, M.D.; Hechtman, J.F.; Cercek, A.; Sanchez-Vega, F.; Jayakumaran, G.; Middha, S.; Zehir, A.; Donoghue, M.T.A.; et al. Clinical Sequencing Defines the Genomic Landscape of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 125–136.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Shay, J.W. Multiple Roles of APC and its Therapeutic Implications in Colorectal Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djw332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghabozorgi, A.S.; Bahreyni, A.; Soleimani, A.; Bahrami, A.; Khazaei, M.; Ferns, G.A.; Avan, A.; Hassanian, S.M. Role of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene mutations in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer; current status and perspectives. Biochimie 2019, 157, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, C.D.; Goss, K.H.; Cornelius, J.R.; Babcock, G.F.; Knudsen, E.S.; Kowalik, T.; Groden, J. The APC tumor suppressor controls entry into S-phase through its ability to regulate the cyclin D/RB pathway. Gastroenterology 2002, 123, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Pei, L.; Xia, H.; Tang, Q.; Bi, F. Role of oncogenic KRAS in the prognosis, diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Morikawa, T.; Lochhead, P.; Imamura, Y.; Kuchiba, A.; Yamauchi, M.; Nosho, K.; Qian, Z.R.; Nishihara, R.; Meyerhardt, J.A.; et al. Prognostic Role of PIK3CA Mutation in Colorectal Cancer: Cohort Study and Literature Review. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 2257–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosho, K.; Kawasaki, T.; Longtine, J.A.; Fuchs, C.S.; Ohnishi, M.; Suemoto, Y.; Kirkner, G.J.; Zepf, D.; Yan, L.; Ogino, S. PIK3CA Mutation in Colorectal Cancer: Relationship with Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations. Neoplasia 2008, 10, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.; Carey, F.A.; Beattie, J.; Wilkie, M.J.V.; Lightfoot, T.J.; Coxhead, J.; Garner, R.C.; Steele, R.J.; Wolf, C.R. Mutations in APC, Kirsten-ras, and p53--alternative genetic pathways to colorectal cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 9433–9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Bazan, V.; Iacopetta, B.; Kerr, D.; Soussi, T.; Gebbia, N. The TP53 Colorectal Cancer International Collaborative Study on the Prognostic and Predictive Significance of p53 Mutation: Influence of Tumor Site, Type of Mutation, and Adjuvant Treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 7518–7528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Klionsky, D.J. Life and Death Decisions—The Many Faces of Autophagy in Cell Survival and Cell Death. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Abdel-Aziz, A.K.; Abdelfatah, S.; Abdellatif, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abel, S.; Abeliovich, H.; Abildgaard, M.H.; Abudu, Y.P.; Acevedo-Arozena, A.; et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (4th edition). Autophagy 2021, 17, 1–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidoni, C.; Ferraresi, A.; Secomandi, E.; Vallino, L.; Dhanasekaran, D.N.; Isidoro, C. Epigenetic targeting of autophagy for cancer prevention and treatment by natural compounds. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 66, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidoni, C.; Vallino, L.; Ferraresi, A.; Secomandi, E.; Salwa, A.; Chinthakindi, M.; Galetto, A.; Dhanasekaran, D.N.; Isidoro, C. Epigenetic control of autophagy in women’s tumors: role of non-coding RNAs. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuwajit, C.; Ferraresi, A.; Titone, R.; Thuwajit, P.; Isidoro, C. The metabolic cross-talk between epithelial cancer cells and stromal fibroblasts in ovarian cancer progression: Autophagy plays a role. Med. Res. Rev. 2017, 38, 1235–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraresi, A.; Girone, C.; Esposito, A.; Vidoni, C.; Vallino, L.; Secomandi, E.; Dhanasekaran, D.N.; Isidoro, C. How Autophagy Shapes the Tumor Microenvironment in Ovarian Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraresi, A.; Girone, C.; Maheshwari, C.; Vallino, L.; Dhanasekaran, D.N.; Isidoro, C. Ovarian Cancer Cell-Conditioning Medium Induces Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Phenoconversion through Glucose-Dependent Inhibition of Autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.-N.; Zhu, B.-S.; Xing, C.-G.; Yang, X.-D.; Young, W.; Cao, J.-P. Effects of autophagy regulation of tumor-associated macrophages on radiosensitivity of colorectal cancer cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 2661–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Lv, L.; Lu, K.; Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Cui, T. Autophagy: Dual roles and perspective for clinical treatment of colorectal cancer. Biochimie 2022, 206, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, S.; Muhammad, J.S.; Maghazachi, A.A.; Hamid, Q. Autophagy: A Versatile Player in the Progression of Colorectal Cancer and Drug Resistance. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 924290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Han, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Tan, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Zou, Y.; Cai, Y.; Huang, S.; et al. Silencing of cadherin-17 enhances apoptosis and inhibits autophagy in colorectal cancer cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 108, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi-Baig, K.; Kuhn, D.; Viry, E.; Pozdeev, V.I.; Schmitz, M.; Rodriguez, F.; Ullmann, P.; Koncina, E.; Nurmik, M.; Frasquilho, S.; et al. Hypoxia-induced autophagy drives colorectal cancer initiation and progression by activating the PRKC/PKC-EZR (ezrin) pathway. Autophagy 2019, 16, 1436–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trincheri, N.F.; Follo, C.; Nicotra, G.; Peracchio, C.; Castino, R.; Isidoro, C. Resveratrol-induced apoptosis depends on the lipid kinase activity of Vps34 and on the formation of autophagolysosomes. Carcinog. 2007, 29, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, N.; Yang, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, M.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, C.; Cui, Y.; Xuan, Y. Suppression of LETM1 inhibits the proliferation and stemness of colorectal cancer cells through reactive oxygen species–induced autophagy. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 25, 2110–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Qian, L.; Wang, X.; Dong, X.; Huang, S.; Jin, M.; Ge, H.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Y. RNF216 contributes to proliferation and migration of colorectal cancer via suppressing BECN1-dependent autophagy. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 51174–51183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Cai, L.-D.; Liu, Y.-H.; Li, S.; Gan, W.-J.; Li, X.-M.; Wang, J.-R.; Guo, P.-D.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, X.-X.; et al. Ube2v1-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of Sirt1 promotes metastasis of colorectal cancer by epigenetically suppressing autophagy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.-X.; Li, C.-Y.; Peng, R.-Q.; Wu, X.-J.; Wang, H.-Y.; Wan, D.-S.; Zhu, X.-F.; Zhang, X.-S. The expression ofbeclin 1is associated with favorable prognosis in stage IIIB colon cancers. Autophagy 2009, 5, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavaglia, B.; Vallino, L.; Amoruso, A.; Pane, M.; Ferraresi, A.; Isidoro, C. The role of gut microbiota, immune system, and autophagy in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Asp. Mol. Med. 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, K.M.; Barlow, P.G.; Henderson, P.; Stevens, C. Interactions Between Autophagy and the Unfolded Protein Response: Implications for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 25, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iida, T.; Onodera, K.; Nakase, H. Role of autophagy in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 1944–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yin, L.; Shen, S.; Hou, Y. Inflammation and cancer: paradoxical roles in tumorigenesis and implications in immunotherapies. Genes Dis. 2023, 10, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowczak, J.; Szczerbowski, K.; Maniewski, M.; Kowalewski, A.; Janiczek-Polewska, M.; Szylberg, A.; Marszałek, A.; Szylberg, Ł. The Role of Inflammatory Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Colorectal Carcinoma—Recent Findings and Review. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthusami, S.; Ramachandran, I.K.; Babu, K.N.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Guruswamy, A.; Queimado, L.; Chaudhuri, G. Role of Inflammation in the Development of Colorectal Cancer. Endocrine, Metab. Immune Disord. - Drug Targets 2021, 21, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, L.; Liu, H.; Feng, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, B.; Li, T.; Liu, L.; Chang, H.; Sun, J.; et al. Altered gut metabolites and metabolic reprogramming involved in the pathogenesis of colitis-associated colorectal cancer and the transition of colon "inflammation to cancer". J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2024, 253, 116553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-Z.; Li, Y.-Y. Inflammatory bowel disease: Pathogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.C.; Itzkowitz, S.H. Colorectal Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Gastroenterology 2021, 162, 715–730.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Tsujinaka, S.; Miura, T.; Kitamura, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Shibata, C. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Etiology, Surveillance, and Management. Cancers 2023, 15, 4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanizza, J.; Bencardino, S.; Allocca, M.; Furfaro, F.; Zilli, A.; Parigi, T.L.; Fiorino, G.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S.; D’amico, F. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, G.; Lee, Y.; Im, E. Interplay between the Gut Microbiota and Inflammatory Mediators in the Development of Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turano, M.; Cammarota, F.; Duraturo, F.; Izzo, P.; De Rosa, M. A Potential Role of IL-6/IL-6R in the Development and Management of Colon Cancer. Membranes 2021, 11, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, N.R.; McCuaig, S.; Franchini, F.; Powrie, F. Emerging cytokine networks in colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaki, T.; Hara, M.; Nakanishi, H.; Takahashi, H.; Sato, M.; Takeyama, H. Interleukin-6 released by colon cancer-associated fibroblasts is critical for tumour angiogenesis: anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody suppressed angiogenesis and inhibited tumour–stroma interaction. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, T. IL-6 in inflammation, autoimmunity and cancer. Int. Immunol. 2020, 33, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Shang, Y.; Sun, F.; Dong, X.; Niu, J.; Li, F. Interleukin-6 Promotes Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Cell Invasion through Integrin β6 Upregulation in Colorectal Cancer. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Zou, X.; Xia, W.; Gao, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, N.; Xu, Z.; Gao, C.; He, Z.; Niu, W.; et al. Integrin αvβ6 plays a bi-directional regulation role between colon cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, L.; Lai, W.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, H.; Lan, Q.; Su, P.; Chu, Z. Interaction with tumor-associated macrophages promotes PRL-3-induced invasion of colorectal cancer cells via MAPK pathway-induced EMT and NF-κB signaling-induced angiogenesis. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 41, 2790–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Bi, J.; Liang, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Han, F.; Li, S.; Qiu, B.; Fan, X.; Chen, W.; et al. VCAM1 Promotes Tumor Cell Invasion and Metastasis by Inducing EMT and Transendothelial Migration in Colorectal Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knüpfer, H.; Preiss, R. Serum interleukin-6 levels in colorectal cancer patients—a summary of published results. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2009, 25, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orecchioni, M.; Ghosheh, Y.; Pramod, A.B.; Ley, K. Macrophage Polarization: Different Gene Signatures in M1(LPS+) vs. Classically and M2(LPS–) vs. Alternatively Activated Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, G.; Li, Y.; Pan, Y. Metabolic Reprogramming Induces Macrophage Polarization in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 840029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Deng, Q.; Hu, Y.; Dong, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, C. Macrophage Polarization, Metabolic Reprogramming, and Inflammatory Effects in Ischemic Heart Disease. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 934040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, D.S.; Windsor, A.; Cohen, R.; Chand, M. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: review of the evidence. Tech. Coloproctol. 2019, 23, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veettil, S.K.; Wong, T.Y.; Loo, Y.S.; Playdon, M.C.; Lai, N.M.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. Role of Diet in Colorectal Cancer Incidence. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2037341–e2037341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A.; Rudzki, G.; Lewandowski, T.; Stryjkowska-Góra, A.; Rudzki, S. Risk Factors for the Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Control. 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernia, F.; Longo, S.; Stefanelli, G.; Viscido, A.; Latella, G. Dietary Factors Modulating Colorectal Carcinogenesis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, K.; Hernández-Cruz, E.Y.; Rogel-Ayala, D.G.; Sarvari, P.; Isidoro, C.; Barreto, G.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Nutriepigenomics in Environmental-Associated Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, L. , Corn, M.D., Scazzocchio, B., Var, R., D’Archivio, M., et al. (2019). Dietary fatty acids and adipose tissue inflammation at the crossroad between obesity and colorectal cancer. Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment.

- Baena, R.; Salinas, P. Diet and colorectal cancer. Maturitas 2015, 80, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Keefe, S.J.D. Diet, microorganisms and their metabolites, and colon cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.H.; Yu, J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer: mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 690–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckhed, F.; Ley, R.E.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; Peterson, D.A.; Gordon, J.I. Host-Bacterial Mutualism in the Human Intestine. Science 2005, 307, 1915–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J.; Arumugam, M.; Burgdorf, K.S.; Manichanh, C.; Nielsen, T.; Pons, N.; Levenez, F.; Yamada, T.; et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 2010, 464, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bander, Z.; Nitert, M.D.; Mousa, A.; Naderpoor, N. The Gut Microbiota and Inflammation: An Overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natividad, J.M.M.; Verdu, E.F. Modulation of intestinal barrier by intestinal microbiota: Pathological and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol. Res. 2013, 69, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thursby, E.; Juge, N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Meng, L.; Xin, Y.; Jiang, X. The role of short-chain fatty acids in intestinal barrier function, inflammation, oxidative stress, and colonic carcinogenesis. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 165, 105420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaprakasam, S.; Bhutia, Y.D.; Yang, S.; Ganapathy, V. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Transporters: Role in Colonic Homeostasis. In Comprehensive Physiology; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 8, pp. 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Kriete, A.; Rosen, G.L. Selecting age-related functional characteristics in the human gut microbiome. Microbiome 2013, 1, 2–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, I.; Tap, J.; Roudot-Thoraval, F.; Roperch, J.P.; Letulle, S.; Langella, P.; Corthier, G.; Van Nhieu, J.T.; Furet, J.P. Microbial Dysbiosis in Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Patients. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e16393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellarin, M.; Warren, R.L.; Freeman, J.D.; Dreolini, L.; Krzywinski, M.; Strauss, J.; Barnes, R.; Watson, P.; Allen-Vercoe, E.; Moore, R.A.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardini, Y.; Wang, X.; Témoin, S.; Nithianantham, S.; Lee, D.; Shoham, M.; Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatumadhesin FadA binds vascular endothelial cadherin and alters endothelial integrity. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 82, 1468–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, M.R.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Hao, Y.; Cai, G.; Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Colorectal Carcinogenesis by Modulating E-Cadherin/β-Catenin Signaling via its FadA Adhesin. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur, C.; Ibrahim, Y.; Isaacson, B.; Yamin, R.; Abed, J.; Gamliel, M.; Enk, J.; Bar-On, Y.; Stanietsky-Kaynan, N.; Coppenhagen-Glazer, S.; et al. Binding of the Fap2 Protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum to Human Inhibitory Receptor TIGIT Protects Tumors from Immune Cell Attack. Immunity 2015, 42, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.; Wang, R.; Bhattacharya, R.; Boulbes, D.R.; Fan, F.; Xia, L.; Adoni, H.; Ajami, N.J.; Wong, M.C.; Smith, D.P.; et al. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Subspecies Animalis Influences Proinflammatory Cytokine Expression and Monocyte Activation in Human Colorectal Tumors. Cancer Prev. Res. 2017, 10, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Lim, K.-C.; Huang, J.; Saidi, R.F.; Sears, C.L. Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin cleaves the zonula adherens protein, E-cadherin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998, 95, 14979–14984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Morin, P.J.; Maouyo, D.; Sears, C.L. Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin induces c-Myc expression and cellular proliferation. Gastroenterology 2003, 124, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, L.; Orberg, E.T.; Geis, A.L.; Chan, J.L.; Fu, K.; Shields, C.E.D.; Dejea, C.M.; Fathi, P.; Chen, J.; Finard, B.B.; et al. Bacteroides fragilis Toxin Coordinates a Pro-carcinogenic Inflammatory Cascade via Targeting of Colonic Epithelial Cells. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 203–214.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.-G.; Xia, Y.; Liu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, H.; Schaefer, K.L.; Zhou, Z.; Bissonnette, M.; et al. Enteric bacterial protein AvrA promotes colonic tumorigenesis and activates colonic beta-catenin signaling pathway. Oncogenesis 2014, 3, e105–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewes, J.L.; Chen, J.; Markham, N.O.; Knippel, R.J.; Domingue, J.C.; Tam, A.J.; Chan, J.L.; Kim, L.; McMann, M.; Stevens, C.; et al. Human Colon Cancer–Derived Clostridioides difficile Strains Drive Colonic Tumorigenesis in Mice. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 1873–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, R.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.-G.; Xia, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Kato, I.; Dong, H.; Bissonnette, M.; Sun, J. Salmonella Protein AvrA Activates the STAT3 Signaling Pathway in Colon Cancer. Neoplasia 2016, 18, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowrouzian, F.L.; Oswald, E. Escherichia coli strains with the capacity for long-term persistence in the bowel microbiota carry the potentially genotoxic pks island. Microb. Pathog. 2012, 53, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziubańska-Kusibab, P.J.; Berger, H.; Battistini, F.; Bouwman, B.A.M.; Iftekhar, A.; Katainen, R.; Cajuso, T.; Crosetto, N.; Orozco, M.; Aaltonen, L.A.; et al. Colibactin DNA-damage signature indicates mutational impact in colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Allen, T.D.; May, R.J.; Lightfoot, S.; Houchen, C.W.; Huycke, M.M. Enterococcus faecalis Induces Aneuploidy and Tetraploidy in Colonic Epithelial Cells through a Bystander Effect. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 9909–9917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonanantanasarn, K.; Gill, A.L.; Yap, Y.; Jayaprakash, V.; Sullivan, M.A.; Gill, S.R. Enterococcus faecalis Enhances Cell Proliferation through Hydrogen Peroxide-Mediated Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Activation. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 3545–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulamir, A.S.; Hafidh, R.R.; Bakar, F. Molecular detection, quantification, and isolation of Streptococcus gallolyticus bacteria colonizing colorectal tumors: inflammation-driven potential of carcinogenesis via IL-1, COX-2, and IL-8. Mol. Cancer 2010, 9, 249–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Herold, J.L.; Schady, D.; Davis, J.; Kopetz, S.; Martinez-Moczygemba, M.; Murray, B.E.; Han, F.; Li, Y.; Callaway, E.; et al. Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus promotes colorectal tumor development. PLOS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, R.; Rajendiran, E.; George, S.; Samuel, G.V.; Ramakrishna, B.S. Real-time polymerase chain reaction quantification of specific butyrate-producing bacteria, Desulfovibrio and Enterococcus faecalis in the feces of patients with colorectal cancer. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 23, 1298–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, M.; Omrani, G.R.; Ebrahimi, B.; Montazeri-Najafabady, N. The Beneficial Effects of Probiotics via Autophagy: A Systematic Review. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Diaz, J.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Gil-Campos, M.; Gil, A. Mechanisms of Action of Probiotics. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2019, 10, S49–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Dong, S.; Wu, X.; Jin, R.; Chen, H. Probiotics in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahouli, I.; Tomaro-Duchesneau, C.; Prakash, S. Probiotics in colorectal cancer (CRC) with emphasis on mechanisms of action and current perspectives. J. Med Microbiol. 2013, 62, 1107–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molska, M.; Reguła, J. Potential Mechanisms of Probiotics Action in the Prevention and Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofori, F.; Dargenio, V.N.; Dargenio, C.; Miniello, V.L.; Barone, M.; Francavilla, R. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Effects of Probiotics in Gut Inflammation: A Door to the Body. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 578386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiptiri-Kourpeti, A.; Spyridopoulou, K.; Santarmaki, V.; Aindelis, G.; Tompoulidou, E.; Lamprianidou, E.E.; Saxami, G.; Ypsilantis, P.; Lampri, E.S.; Simopoulos, C.; et al. Lactobacillus casei Exerts Anti-Proliferative Effects Accompanied by Apoptotic Cell Death and Up-Regulation of TRAIL in Colon Carcinoma Cells. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0147960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertkova, I.; Hijova, E.; Chmelarova, A.; Mojzisova, G.; Petrasova, D.; Strojny, L.; Bomba, A.; Zitnan, R. The effect of probiotic microorganisms and bioactive compounds on chemically induced carcinogenesis in rats. Neoplasma 2010, 57, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, N.K.; Sinha, P.R. Inhibition of 1,2-dimethylhydrazine induced colon genotoxicity in rats by the administration of probiotic curd. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2009, 37, 1373–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-H.; Shim, Y.Y.; Cha, S.-K.; Reaney, M.J.T.; Chee, K.M. Effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus KFRI342 on the development of chemically induced precancerous growths in the rat colon. J. Med Microbiol. 2012, 61, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleyard, C.B.; Cruz, M.L.; Isidro, A.A.; Arthur, J.C.; Jobin, C.; De Simone, C. Pretreatment with the probiotic VSL#3 delays transition from inflammation to dysplasia in a rat model of colitis-associated cancer. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2011, 301, G1004–G1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, E.; Hwang, S.W.; Kim, S.; Ryu, Y.; Cho, E.A.; Chung, E.; Park, S.; Lee, H.J.; Byeon, J.; Ye, B.D.; et al. Suppression of colitis-associated carcinogenesis through modulation of IL-6/STAT3 pathway by balsalazide and VSL#3. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 31, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Shukla, G. ProbioticsLactobacillus rhamnosus GG,Lactobacillus acidophilusSuppresses DMH-Induced Procarcinogenic Fecal Enzymes and Preneoplastic Aberrant Crypt Foci in Early Colon Carcinogenesis in Sprague Dawley Rats. Nutr. Cancer 2013, 65, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin∗, C.; Millette∗, M.; Oth, D.; Ruiz, M.T.; Luquet, F.-M.; Lacroix, M. ProbioticLactobacillus AcidophilusandL. CaseiMix Sensitize Colorectal Tumoral Cells to 5-Fluorouracil-Induced Apoptosis. Nutr. Cancer 2010, 62, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla, J.; Lane, M.A.; Maitin, V. Cell-Free Supernatants from ProbioticLactobacillus caseiandLactobacillus rhamnosusGG Decrease Colon Cancer Cell Invasion In Vitro. Nutr. Cancer 2012, 64, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österlund, P.; Ruotsalainen, T.; Korpela, R.; Saxelin, M.; Ollus, A.; Valta, P.; Kouri, M.; Elomaa, I.; Joensuu, H. Lactobacillus supplementation for diarrhoea related to chemotherapy of colorectal cancer: a randomised study. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 97, 1028–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, H.; Akedo, I.; Otani, T.; Suzuki, T.; Nakamura, T.; Takeyama, I.; Ishiguro, S.; Miyaoka, E.; Sobue, T.; Kakizoe, T. Randomized trial of dietary fiber andLactobacillus casei administration for prevention of colorectal tumors. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 116, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Qin, H.; Yang, Z.; Xia, Y.; Liu, W.; Yang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Q. Randomised clinical trial: the effects of perioperative probiotic treatment on barrier function and post-operative infectious complications in colorectal cancer surgery-A double-blind study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, M.; Nagata, S.; Saito, M.; Shimizu, T.; Yamashiro, Y.; Matsuki, T.; Asahara, T.; Nomoto, K. Effects of the enteral administration of Bifidobacterium breve on patients undergoing chemotherapy for pediatric malignancies. Support. Care Cancer 2009, 18, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotzampassi, K.; Stavrou, G.; Damoraki, G.; Georgitsi, M.; Basdanis, G.; Tsaousi, G.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J. A Four-Probiotics Regimen Reduces Postoperative Complications After Colorectal Surgery: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. World J. Surg. 2015, 39, 2776–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbancsek, H.; Kazar, T.; Mezes, I.; Neumann, K. Results of a double-blind, randomized study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Antibiophilus® in patients with radiation-induced diarrhoea. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2001, 13, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitapanarux, I.; Chitapanarux, T.; Traisathit, P.; Kudumpee, S.; Tharavichitkul, E.; Lorvidhaya, V. Randomized controlled trial of live lactobacillus acidophilus plus bifidobacterium bifidum in prophylaxis of diarrhea during radiotherapy in cervical cancer patients. Radiat. Oncol. 2010, 5, 31–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golkhalkhali, B.; Rajandram, R.; Paliany, A.S.; Ho, G.F.; Ishak, W.Z.W.; Johari, C.S.; Chin, K.F. Strain-specific probiotic (microbial cell preparation) and omega-3 fatty acid in modulating quality of life and inflammatory markers in colorectal cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Asia-Pacific J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Guo, B.; Gao, R.; Zhu, Q.; Wu, W.; Qin, H. Probiotics modify human intestinal mucosa-associated microbiota in patients with colorectal cancer. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 6119–6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, S.A.; da Conceição, L.L.; Siqueira, N.P.; Rosa, D.D.; da Silva, L.L.; Peluzio, M.D.C.G. Review of the mechanisms of probiotic actions in the prevention of colorectal cancer. Nutr. Res. 2017, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallino, L.; Garavaglia, B.; Visciglia, A.; Amoruso, A.; Pane, M.; Ferraresi, A.; Isidoro, C. Cell-free Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 supernatant suppresses IL-6-induced proliferation and invasion of human colorectal cancer cells: Effect on β-Catenin degradation and induction of autophagy. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2023, 13, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garavaglia, B.; Vallino, L.; Ferraresi, A.; Amoruso, A.; Pane, M.; Isidoro, C. Probiotic-Derived Metabolites from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 Reprogram Tumor-Associated Macrophages to an Inflammatory Anti-Tumoral Phenotype: Impact on Colorectal Cancer Cell Proliferation and Migration. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambalam, P.; Dave, J.; Nair, B.M.; Vyas, B. In vitro Mutagen binding and antimutagenic activity of human Lactobacillus rhamnosus 231. Anaerobe 2011, 17, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pithva, S.P.; Ambalam, P.S.; Ramoliya, J.M.; Dave, J.M.; Vyas, B.R.M. Antigenotoxic and Antimutagenic Activities of ProbioticLactobacillus rhamnosusVc against N-Methyl-N′-Nitro-N-Nitrosoguanidine. Nutr. Cancer 2015, 67, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compare, D.; Rocco, A.; Coccoli, P.; Angrisani, D.; Sgamato, C.; Iovine, B.; Salvatore, U.; Nardone, G. Lactobacillus casei DG and its postbiotic reduce the inflammatory mucosal response: an ex-vivo organ culture model of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Chen, D.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, W.; Liu, T.; Wang, S.; Dai, X.; Wang, B.; Zhong, W.; Cao, H. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and colorectal cancer: Ready for clinical translation? Cancer Lett. 2022, 526, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; McKenzie, C.; Potamitis, M.; Thorburn, A.N.; Mackay, C.R.; Macia, L. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Health and Disease. Adv. Immunol. 2014, 121, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-B.; Wang, P.-Y.; Wang, X.; Wan, Y.-L.; Liu, Y.-C. Butyrate Enhances Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Function via Up-Regulation of Tight Junction Protein Claudin-1 Transcription. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012, 57, 3126–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger-van Paassen, N.; Vincent, A.; Puiman, P.J.; Van Der Sluis, M.; Bouma, J.; Boehm, G.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Van Seuningen, I.; Renes, I.B. The regulation of intestinal mucin MUC2 expression by short-chain fatty acids: implications for epithelial protection. Biochem. J. 2009, 420, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Sun, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Yu, Y.; Hu, T.; Yao, Y.; Zhou, C. Bacteroides fragilis restricts colitis-associated cancer via negative regulation of the NLRP3 axis. Cancer Lett. 2021, 523, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohira, H.; Fujioka, Y.; Katagiri, C.; Mamoto, R.; Aoyama-Ishikawa, M.; Amako, K.; Izumi, Y.; Nishiumi, S.; Yoshida, M.; Usami, M.; et al. Butyrate Attenuates Inflammation and Lipolysis Generated by the Interaction of Adipocytes and Macrophages. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2013, 20, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibbie, J.J.; Dillon, S.M.; Thompson, T.A.; Purba, C.M.; McCarter, M.D.; Wilson, C.C. Butyrate directly decreases human gut lamina propria CD4 T cell function through histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition and GPR43 signaling. Immunobiology 2021, 226, 152126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.-M.; Yu, Y.-N.; Wang, J.-L.; Lin, Y.-W.; Kong, X.; Yang, C.-Q.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z.-J.; Yuan, Y.-Z.; Liu, F.; et al. Decreased dietary fiber intake and structural alteration of gut microbiota in patients with advanced colorectal adenoma. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, T.L.; Manter, D.K.; Sheflin, A.M.; Barnett, B.A.; Heuberger, A.L.; Ryan, E.P. Stool Microbiome and Metabolome Differences between Colorectal Cancer Patients and Healthy Adults. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; Umar, S.; Rust, B.; Lazarova, D.; Bordonaro, M. Secondary Bile Acids and Short Chain Fatty Acids in the Colon: A Focus on Colonic Microbiome, Cell Proliferation, Inflammation, and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Li, Z.; Mao, L.; Chen, S.; Sun, S. Sodium butyrate induces autophagy in colorectal cancer cells through LKB1/AMPK signaling. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 75, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, C.; Zhao, W.; He, C.; Ding, J.; Dai, R.; Xu, K.; Xiao, L.; Luo, L.; Liu, S.; et al. Impaired Autophagy in Intestinal Epithelial Cells Alters Gut Microbiota and Host Immune Responses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hu, J.; Wang, M.; Yuan, H.; Xing, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ding, M.; Chen, W.; Qu, B.; Zhu, L. CISD2 Promotes Proliferation of Colorectal Cancer Cells by Inhibiting Autophagy in a Wnt/β-Catenin-Signaling-Dependent Pathway. Biochem. Genet. 2022, 61, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavaglia, B.; Vallino, L.; Ferraresi, A.; Esposito, A.; Salwa, A.; Vidoni, C.; Gentilli, S.; Isidoro, C. Butyrate Inhibits Colorectal Cancer Cell Proliferation through Autophagy Degradation of β-Catenin Regardless of APC and β-Catenin Mutational Status. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Brumell, J.H.; Chu, C.T.; Codogno, P.; Cuervo, A.M.; Debnath, J.; Deretic, V.; Elazar, Z.; Eskelinen, E.-L.; et al. A comprehensive glossary of autophagy-related molecules and processes (2ndedition). Autophagy 2011, 7, 1273–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy and disease: unanswered questions. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 858–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foerster, E.G.; Mukherjee, T.; Cabral-Fernandes, L.; Rocha, J.D.; Girardin, S.E.; Philpott, D.J. How autophagy controls the intestinal epithelial barrier. Autophagy 2021, 18, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooks, M.G.; Garrett, W.S. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglio, A.E.V.; Grillo, T.G.; De Oliveira, E.C.S.; Di Stasi, L.C.; Sassaki, L.Y. Gut microbiota, inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 4053–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, H.K. Potential Role of the Gut Microbiome In Colorectal Cancer Progression. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 807648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Jeong, S. Mutation Hotspots in the β-Catenin Gene: Lessons from the Human Cancer Genome Databases. Mol Cells. 2019, 42, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clevers, H. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Development and Disease. Cell 2006, 127, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Ming, T.; Tang, S.; Ren, S.; Yang, H.; Liu, M.; Tao, Q.; Xu, H. Wnt signaling in colorectal cancer: pathogenic role and therapeutic target. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, S.D.; Bertagnolli, M.M. Molecular origins of cancer: Molecular Basis of Colorectal Cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 2449–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, V.A.; Gheorghe, G.; Bacalbasa, N.; Chiotoroiu, A.L.; Diaconu, C. Colorectal Cancer: From Risk Factors to Oncogenesis. Medicina 2023, 59, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, C.A.; Stombaugh, J.I.; Gordon, J.I.; Jansson, J.K.; Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 2012, 489, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Marano, L.; Merola, E.; Roviello, F.; Połom, K. Sodium butyrate in both prevention and supportive treatment of colorectal cancer. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1023806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Lee, G.; Son, H.; Koh, H.; Kim, E.S.; Unno, T.; Shin, J.-H. Butyrate producers, “The Sentinel of Gut”: Their intestinal significance with and beyond butyrate, and prospective use as microbial therapeutics. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1103836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization and of the United Nations/World Health Organization. (2002). Guidelines for the evaluation of probiotics in foods, Available at: https://www.who.int>fs management>probiotic guidelines.

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, R.; Shafi, S.; Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; Liu, S.-B. Research progress of intestinal microbiota in targeted therapy and immunotherapy of colorectal cancer. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.A.K.; Sarker, M.; Li, T.; Yin, J. Probiotic Species in the Modulation of Gut Microbiota: An Overview. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 9478630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Weiskirchen, S.; Weiskirchen, R. Effects of Probiotics on Gut Microbiota: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-W.; Du, P.; Yang, B.-R.; Gao, J.; Fang, W.-J.; Ying, C.-M. Preoperative Probiotics Decrease Postoperative Infectious Complications of Colorectal Cancer. Am. J. Med Sci. 2012, 343, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanno M, Kato I, Kobayashi T, Shida K. Biological effects of probiotics: what impact does Lactobacillus casei shirota have on us? Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011 Jan-Mar;24(1 Suppl):45S-50S. [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).