1. Introduction

In order to address the challenges of climate change and accommodate rapidly growing demand of energy, solar energy, being a clean and safe renewable energy source, has been widely adopted for power generation in recent years [

1]. However, with the rapid expansion in solar power plants, flatten terrain resources are becoming increasingly scarce. As a result, flexible photovoltaic (PV) support systems have attracted significant interest due to their ability to adapt to complex environments such as deserts, mountains, fishponds, and sewage treatment plants. Despite these advantages, the inherent low stiffness and low damping ratios of cable-supported systems make them highly susceptible to wind-induced vibrations, which can further lead to PV modules being lifted, collisions, latent cracks, and even damage to the supporting structures. Therefore, wind-induced vibration must be taken into account during the design process. Current research methodologies for this issue primarily include wind tunnel aeroelastic tests as well as finite element (FE) simulations. However, the former lacks field-measured damping ratios for model calibration, while the latter suffers from insufficient validation against field-measured modal frequencies and mode shapes. Moreover, both methods seldom consider the changes in structural parameters of flexible PV supports during their service life. To address these limitations, field modal testing should be conducted to obtain accurate modal properties of flexible PV support structures. Meanwhile, FE model updating utilizing field-measured data is essential to develop a high-fidelity FE model that faithfully represents the actual structure.

Previous studies of flexible PV support structures based on wind tunnel aeroelastic tests have revealed that critical wind speeds are low and cables may suddenly collapse due to intensive vibration [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Furthermore, He et al. [

7] observed flexible PV support fluttering in the aeroelastic tunnel testing, which was mainly characterized by coupled torsional and vertical motions. These findings underscore the high susceptibility of flexible PV support structures to flutter instability. The damping of flexible PV support structure is crucial in determining whether its vibration will diverge and lead to flutter. However, there is a notable lack of field studies providing accurate identification. Bao et al. [

8] measured the first three order modal parameters of a solar tracker, but the modal properties of solar trackers notably differ from those of flexible PV supports. Lei et al. [

9] conducted field testing on large-span flexible PV supports, obtaining only the vertical bending modal damping ratio and frequency. Therefore, more comprehensive field modal testing of flexible PV support structures is necessary to obtain other high-order modal properties.

In field modal testing, it is difficult to obtain the full-frequency response information of a structure using single type sensor. In 1973, the U.S. Department of Defense [

10] first proposed data fusion from different types of sensors to obtain more accurate response estimates and improve system redundancy. Subsequently, this technology has been widely applied in the structural health monitoring of bridges, high-rise buildings, and transmission towers. In 2007, Smyth and Wu [

11] proposed a multi-rate Kalman filter for the data fusion to address the issue of different sensor sampling rates. Based on the fusion of high-frequency accelerometer signals and low-frequency GNSS signals, Yang et al. [

12] identified the modal frequencies of the Shanghai Tower; Moschas and Stiros [

13] identified the modal frequencies and dynamic responses of a 40 m pedestrian steel bridge; Luo et al. [

14] identified the high-order modes and more accurate modal parameters of a 660 m long suspension bridge. By fusing high-frequency accelerometer signals with low-frequency strain signals, Zhu et al. [

15] obtained displacement responses of the Canton Tower covering both ultra-low and high frequencies; Zhang et al. [

16] identified the modal frequencies and mode shapes of a 50 m high transmission tower. In recent years, with the development of optical sensors and computer vision technology, computer vision-based displacement measurement has been widely used due to its advantages of simple installation and low cost. However, image resolution, lighting conditions, and shooting distance can affect the accuracy of vision-based measurements [

17]. Accelerometers, on the other hand, can capture high-frequency, small-amplitude vibrations, supplementing the limitations of vision-based methods. Therefore, Park et al. [

18] proposed fusion of vision-based displacement with acceleration via a complementary filter and time synchronization algorithm to obtain displacement signals with reduced noise. Based on the fusion of high-frequency accelerometer signals and low-frequency vision-based displacement signals, Ma et al. [

19] acquired high-frequency displacement signals at a single measurement point of a steel box girder pedestrian bridge in Korea; Xiu et al. [

20] identified modal properties of a reinforced concrete frame structure. These studies indicate that current applications of multi-sensor data fusion mainly focus on bridges, high-rise buildings, and transmission towers, while there is a lack of research on new structural types such as PV supports. This gap highlights the need for further development of multi-sensor data fusion techniques tailored to the unique challenges of PV support structures.

While field modal testing provides the foundation for understanding the dynamic behavior of flexible PV supports, the absence of a unified FE modeling approach has led to significant discrepancies in wind vibration coefficients across existing studies. Xu et al. [

21] recommended a theoretical value of 1.73 for the wind vibration coefficient. Du et al. [

22] used ANSYS for FE analysis and reported wind vibration coefficients of 2.11 and 1.98 for the along-wind and vertical displacements of flexible PV support structures, respectively. Song et al. [

23] conducted wind pressure time-history simulations and FE analysis, suggesting that the wind vibration coefficient for single-layer flexible PV support structures should be in the range of 1.3 to 1.7. Wang et al. [

24,

25,

26] simulated fluctuating wind speeds using an autoregressive model and established multi-span FE models of flexible PV supports in SAP2000, comparing the dynamic response characteristics under different wind load. Among the above studies using FE analysis, Du et al. [

22] and Song et al. [

23] only established single-span models without considering support columns, treating the cable ends as fixed constraints. In contrast, Xu, Song and Wang et al [

21,

23,

24,

25,

26] considered support columns in their modeling and developed multi-span models. It can be seen that there is currently no unified approach to modeling flexible PV support structures, which further leads to significant differences in the wind vibration coefficients calculated among the aforementioned studies [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Therefore, it is significant to conduct the FE model updating based on field measurement of flexible PV support structures.

In FE model updating, the direct method [

27,

28] adjusts the model by modifying the system’s stiffness, mass, and damping matrices. This method requires no iterative computation and always yields a convergent solution; however, the updated system matrices often lose their physical meaning, and nodal continuity cannot be ensured [

29]. Moreover, the direct modification approach operates directly on the system matrices, it typically requires complete experimental modal data at multiple measurement points. To address these limitations, Mottershead and Friswell [

30] proposed a sensitivity-based updating method, which adjusts material properties, geometric parameters, and boundary conditions of the model in accordance with measured responses. However, traditional sensitivity-based model updating methods require repeated calls to FE software, which is computationally inefficient. Furthermore, ill-conditioned sensitivity matrices may result in convergence difficulties [

31]. To overcome these shortcomings, Guo and Zhang [

32] introduced the response surface model, which utilizes explicit surrogate functions to approximate the implicit relationships in FE models, thus avoiding repeated FE computations and enabling more efficient convergence. Based on ambient vibration data from a six-span continuous beam bridge, Ren et al. [

33] performed response surface-based FE model updating and compared the results with traditional sensitivity-based methods. The findings indicated that the response surface-based approach significantly improved updating efficiency and convergence speed. Fang [

34] applied the response surface method to FE model updating and damage identification for the I-40 bridge; the results demonstrated that second-order polynomial and first-order linear models are capable of characterizing the relationship between structural parameters and responses. Although FE model updating has been widely applied in bridges and high-rise buildings, studies on its application to flexible PV support structures remain limited.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides a detailed explanation of modal property identification based on multi-sensor data fusion, and the response surface-based FE model updating method for flexible PV support structures.

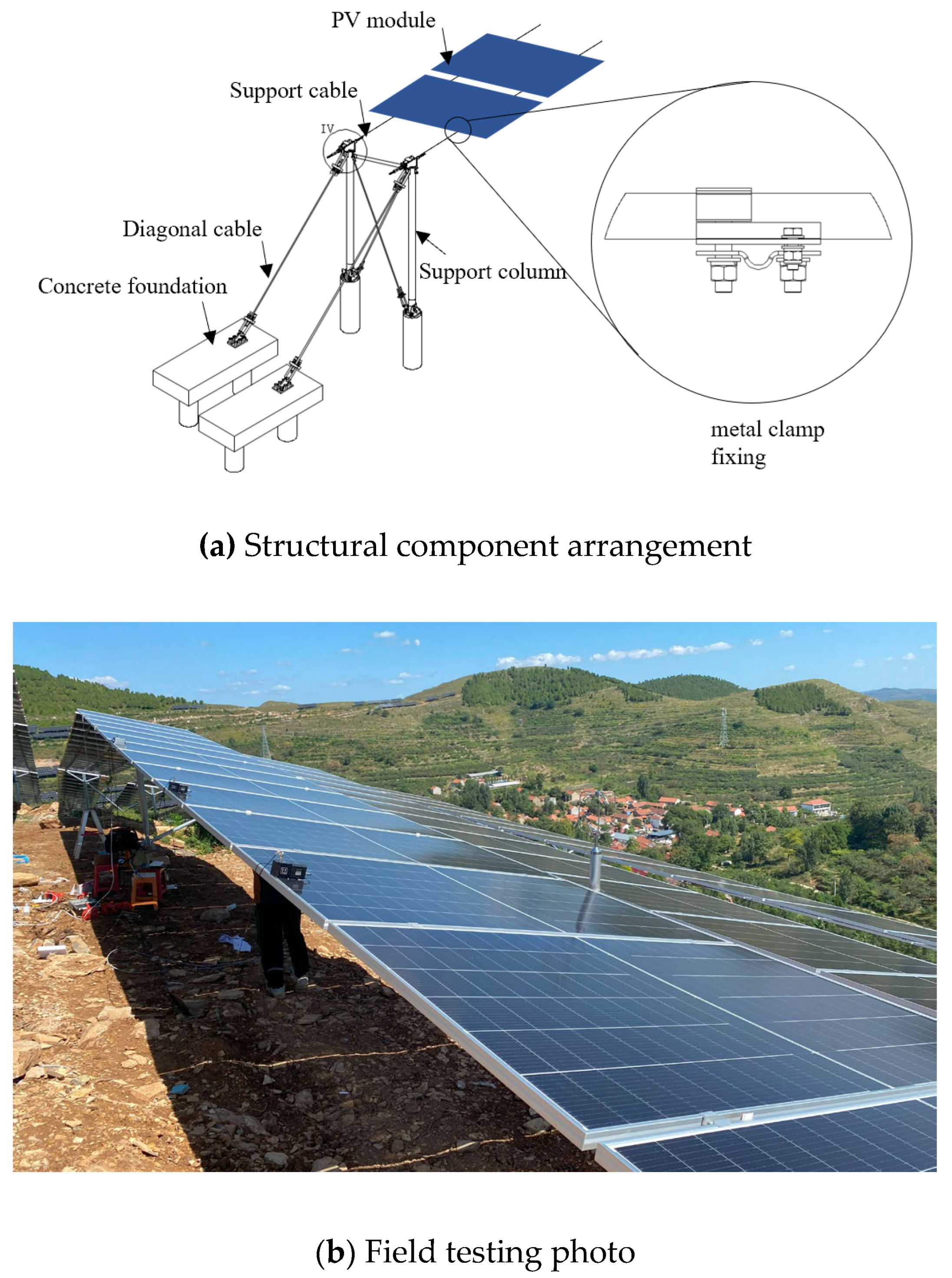

Section 3 introduces the flexible PV support’s structure composition and the field modal testing scheme.

Section 4 presents the field-measured high-order modal frequencies, damping ratios and spatial mode shapes of the flexible PV support, and fits the response surface to obtain the updated FE model.

Section 5 concludes with a summary of the key findings.

2. Methodology

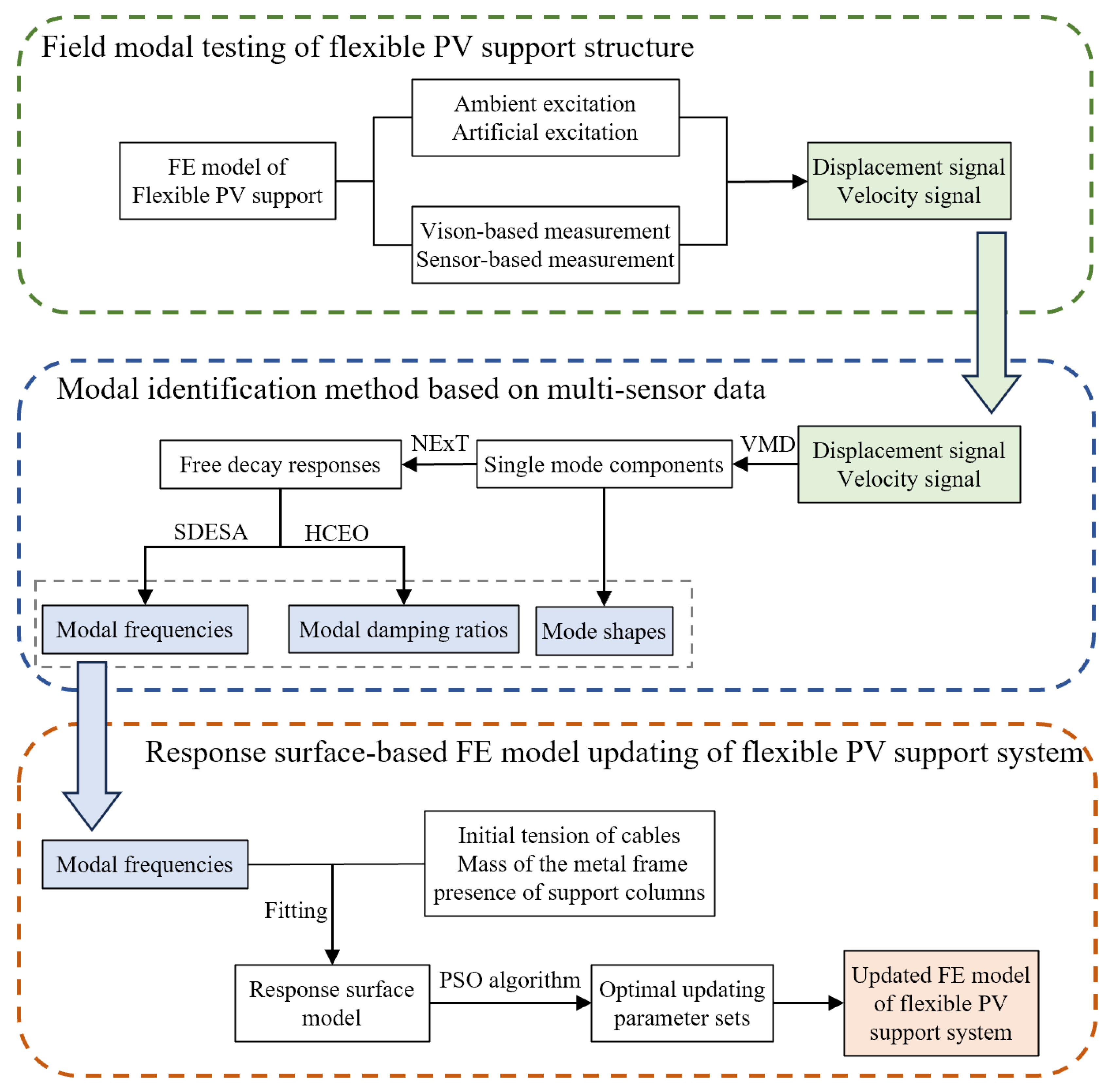

The flowchart of modal property identification and FE model updating for flexible PV support structures is shown in

Figure 1. First, field modal testing of the flexible PV support structure is carried out. Subsequently, the VMD-SH method proposed by Cai et.al. [

35] is employed to identify the modal frequencies and damping ratios. In the VMD-SH method, multi-sensor signals are first decomposed into a series of single-mode components using the variational mode decomposition (VMD) [

36] method. The natural excitation technique (NExT) [

37] is then used to convert these single-mode components into free decay signals. The smoothed discrete energy separation algorithm (SDESA) [

38] is applied to the free decay signals to identify time-varying modal frequencies, while the half-cycle energy operator (HCEO) [

39] is used to identify time-varying modal damping ratios. The modal shapes are identified from multi-sensor signals using a VMD-based approach. For FE model updating, response surface model for modal frequencies is first constructed. Then, the particle swarm optimization (PSO) [

40] algorithm is employed on the response surface to search for the combination of modeling parameters that minimizes the error between the FE modal frequencies and the field-measured modal frequencies, thereby obtaining the updated FE model.

2.1. Identification of Modal Frequencies and Damping Ratios

VMD [

36] is adopted as the primary signal decomposition technique owing to its capability to separate mixed signals into mutually independent components (MICs). In contrast to traditional approaches—which are often affected by problems such as mode mixing and end effects—VMD iteratively minimizes the bandwidth of each modal component while simultaneously determining its center frequency. The decomposition process is formulated as a constrained variational optimization problem, expressed as follows:

where

represents each mode,

is the center frequency,

is the Dirac distribution, and

is the input signal.

After decomposition, each single-mode component is processed using NExT [

37] to obtain the free decay response. Subsequently, the SDESA [

38] method is employed to identify the modal frequency as follows:

where

is the discrete signal,

is the sampling frequency and

devotes the actual frequency of

. This approach mitigates end effects, ensuring precise identification of natural frequencies.

To identify damping ratios, the HCEO [

39] is applied to the free decay signals of each mode. This approach calculates the energy dissipated per vibration cycle and derives the damping ratio

as follows:

where

is the energy of each half-cycle.

While the original VMD-SH [

35] was designed for frequency and damping ratio identification, this study proposes an extended approach to also identify mode shapes, as detailed in

Section 3.2.

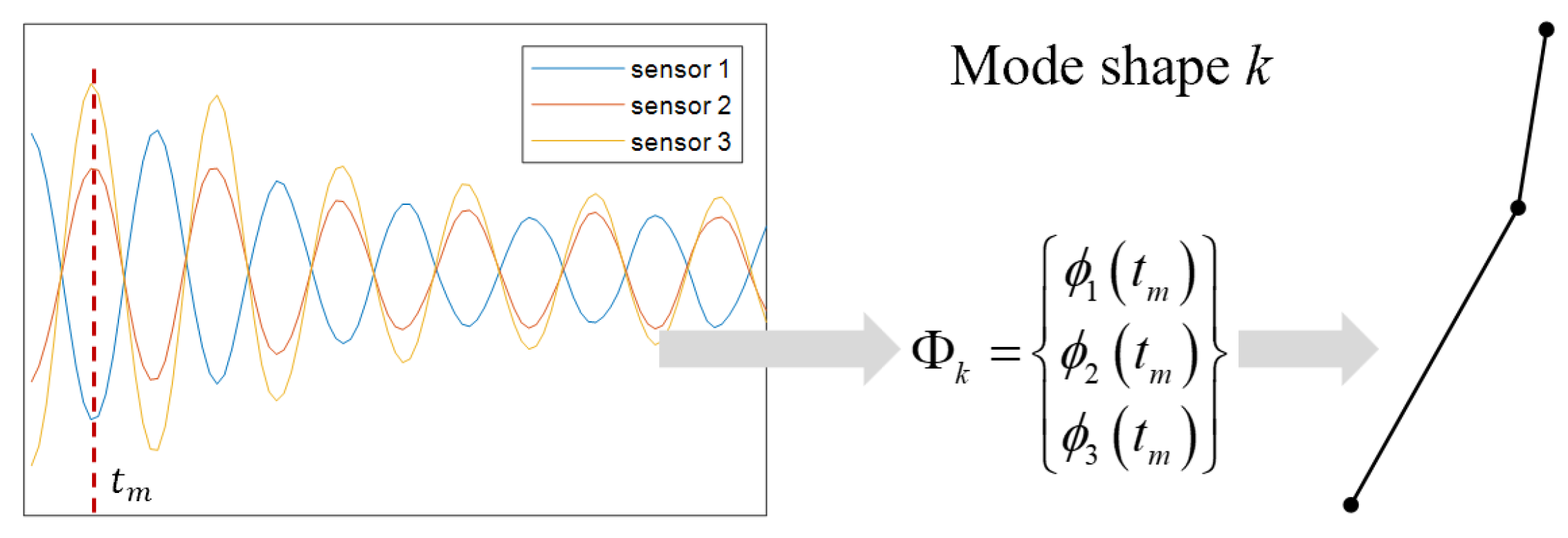

2.2. Identification of Mode Shapes

To obtain the mode shape of a specific mode, it is necessary to consider the single-mode responses of the structure at all sensor locations. The modal vector is constructed from the single-mode response values at all sensor positions at an identical time instant tm, which is typically selected at a local minimum or maximum. Accordingly, the modal vector of the

k-th mode for the structure can be expressed as [

41]:

where

represents the modal response of the

k-th mode at the

j-th senser location,

is the time instant when a local minimum or maximum of the modal response occurs, and

N is the total number of sensors.

Figure 2 illustrates the process of identifying the

k-th mode shape using signals from three sensors.

The modal assurance criterion (MAC) [

42] serves as a quantitative measure of the consistency (or degree of linear correlation) between estimates of a modal vector. The MAC enables the comparison of modal vectors obtained from different sources, thereby allowing for an assessment of the consistency between FE analysis results and field-measured results. The MAC is defined as follows [

42]:

In this equation, is modal vector for reference c mode r, is modal vector for reference d mode r. MAC is between 0 and 1, with 0 representing no consistent correspondence and 1 representing consistent correspondence.

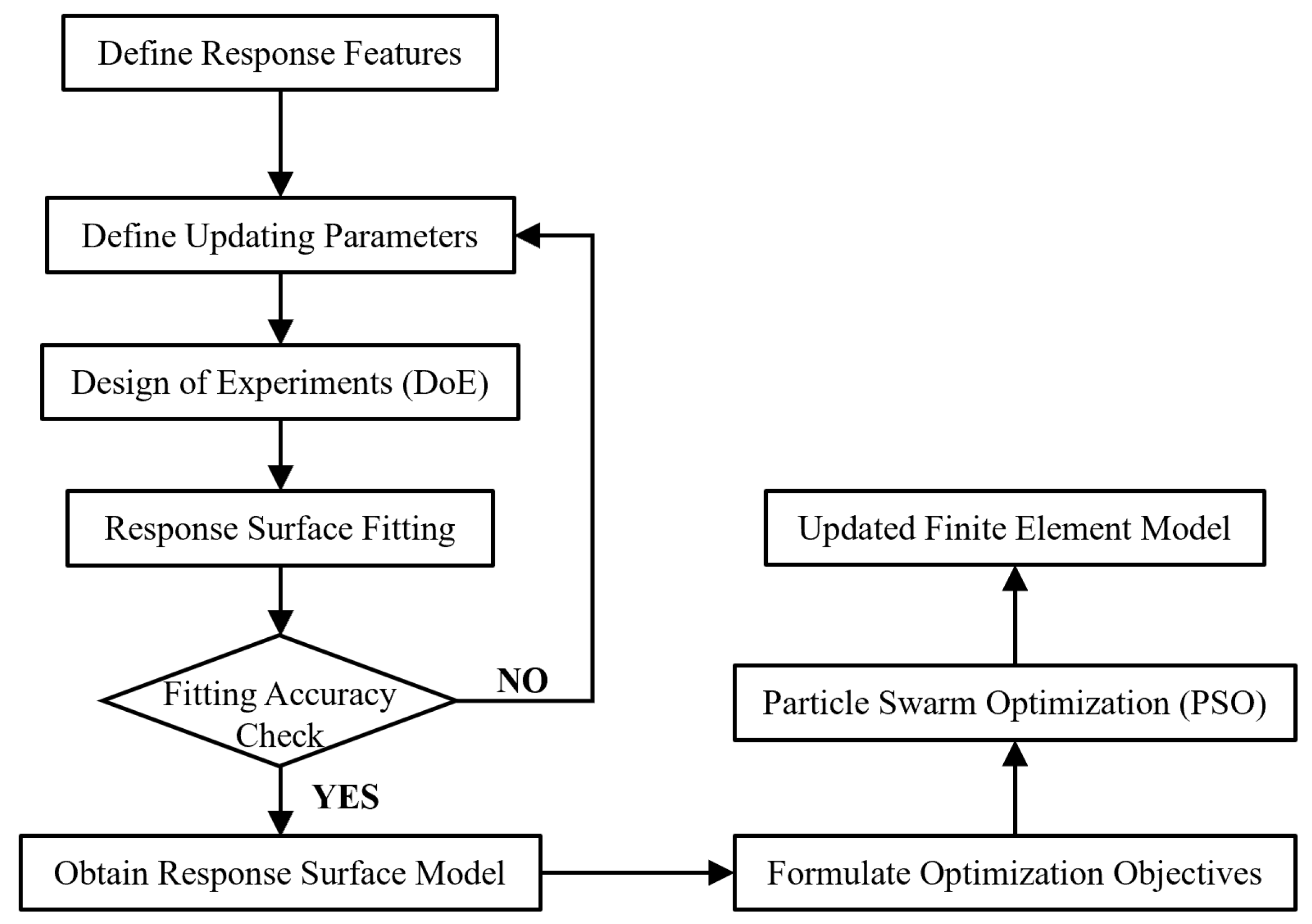

2.3. Response Surface-Based FE Model Updating Methodology

The overall procedure of response surface-based FE model updating is illustrated in

Figure 3.

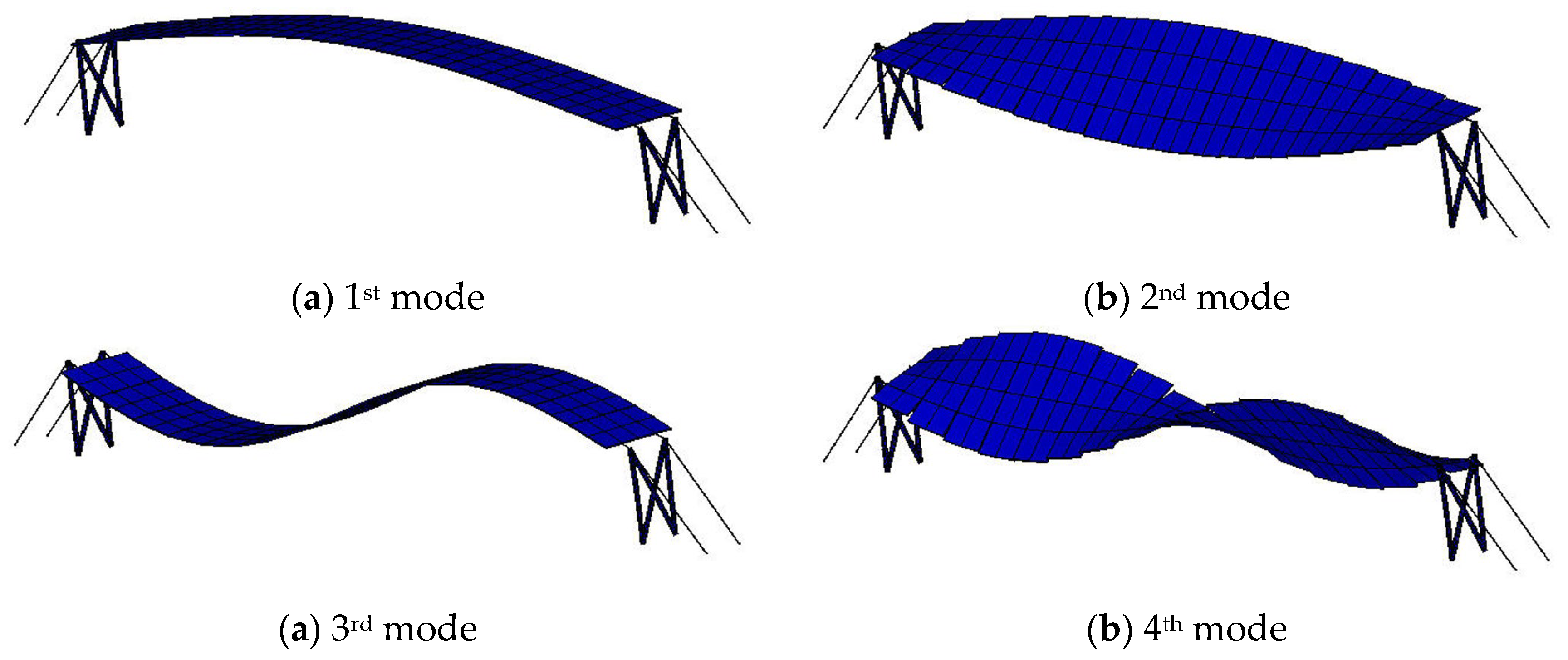

For flexible PV support structures, their large spans and low stiffness make them susceptible to wind-induced vibrations [

43]. To ensure that the updated model more accurately represents the actual dynamic characteristics of the structure, the first four modal frequencies are selected as the response features for model updating.

The selection of updating parameters for flexible PV support structure models differs significantly from that for buildings and bridges. The main reasons are as follows: the components of the support are mostly standardized, with minimal differences in size and material properties between them; as a steel structure, the mechanical properties of the support are more stable compared to concrete, but it is also more susceptible to corrosion; the flexible support is a prestressed cable-supported structure, and under wind loads, slippage at the cable anchor points can lead to a decrease in cable tension; PV modules consist of aluminum frames, laminates, and junction boxes, and previous modeling of PV modules often assumed them to be uniformly distributed panels, which overlooks the mass non-uniformity of the aluminum frames and laminate layers. Based on these considerations, the preliminary selection of updating parameters includes the mass of the metal frame M, cable initial tension T and support column modeling L.

When a complex or unknown relationship exists between the modal frequency y of a flexible PV support structure and its physical parameters, this relationship can be represented by an explicit hypersurface function, that is, a response surface model [

33]:

Where,

,

denotes the statistical error,

is an unknown implicit function. Since

is unknow, researchers aim to estimate

using an approximate but explicit function, which can be achieved by the response surface model

. The estimated response can be expressed as:

Where, represents the error of the response surface, which should be minimized as much as possible. Subsequently, the response surface can be used to substitute for the physical model in numerical analysis.

The selection of the response surface function type first requires that its mathematical expression can adequately describe the true relationship between the input parameters and the output response. Second, the expression should contain the minimum number of terms to reduce the required number of sampling points and enhance interpretability. For most engineering problems, a standard quadratic polynomial function can be used to represent the physical system [

33]:

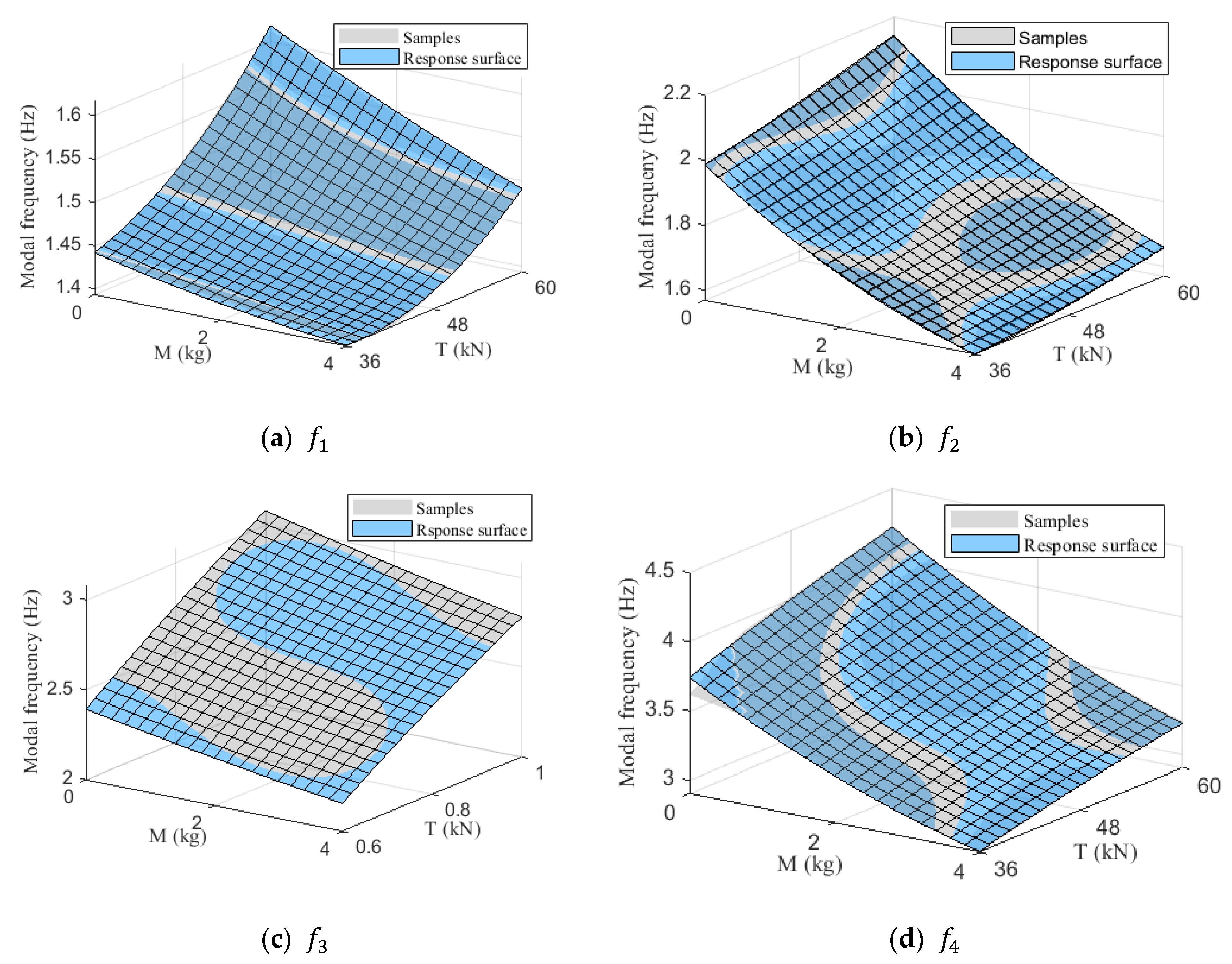

Where, denotes the response feature, specifically the first four modal frequencies of the flexible PV support structure, with each frequency corresponding to a separate response surface model. represents the range of values for the updating parameters, and , , , are the regression coefficients.

Equation (8) can be represented in matrix form as:

Where is the response vector, B is the matrix of regression coefficients, and e contains all errors.

The unbiased estimate

b of the regression coefficient matrix

B can be obtained by the least square method:

Finally, the response

estimated by the response surface can be expressed as:

To ensure its reliability for future applications, response surface model must be validated. This validation process involves two key aspects: assessing the model’s fitting performance on design points and evaluating its predictive capability with unseen data. Several indices are used for this validation:

represents the interpretability of the model, with a range of [0,1]. A value close to 1 indicates a high level of fit. A smaller RMSE indicates a smaller model error.

The optimization problem in FE model updating can be expressed as minimizing the error between the field-measured results and the FE analysis results:

Where, PFEM and PEXP represent the external excitations applied to the FE modal and the actual structure, respectively. and denote certain mappings of the FE model and the actual structure. represents the error function, and the feasible domain of the updating parameters X is [XL, XU]. FE model updating requires minimizing the error function.

In this study, the first four modal frequencies are chosen as the response features,

. Each response feature is fitted with an independent response surface function

. So, Equation (14) can be rewritten as:

Equation (15) represents a multi-objective optimization problem, which can be transformed into a single-objective optimization problem:

The single-objective optimization problem under the constraint of Equation (16) is subsequently solved using PSO [

40]. In PSO,

particles are randomly initialized in a D-dimensional parameter space. Each particle

has two attributes: a velocity

, representing the direction and magnitude of iteration, and a position

, representing a combination of updating parameters. The velocity and position are updated as follows:

Where, denotes the iteration number; is the local best position of particle in dimension , and is the global best position of the swarm in dimension ; and are random numbers in the interval [0,1]; is the inertia weight; and are the local and global learning coefficients, respectively. Therefore, the update direction of each particle incorporates the local best direction, the global best direction, and the inertial direction.

5. Conclusions

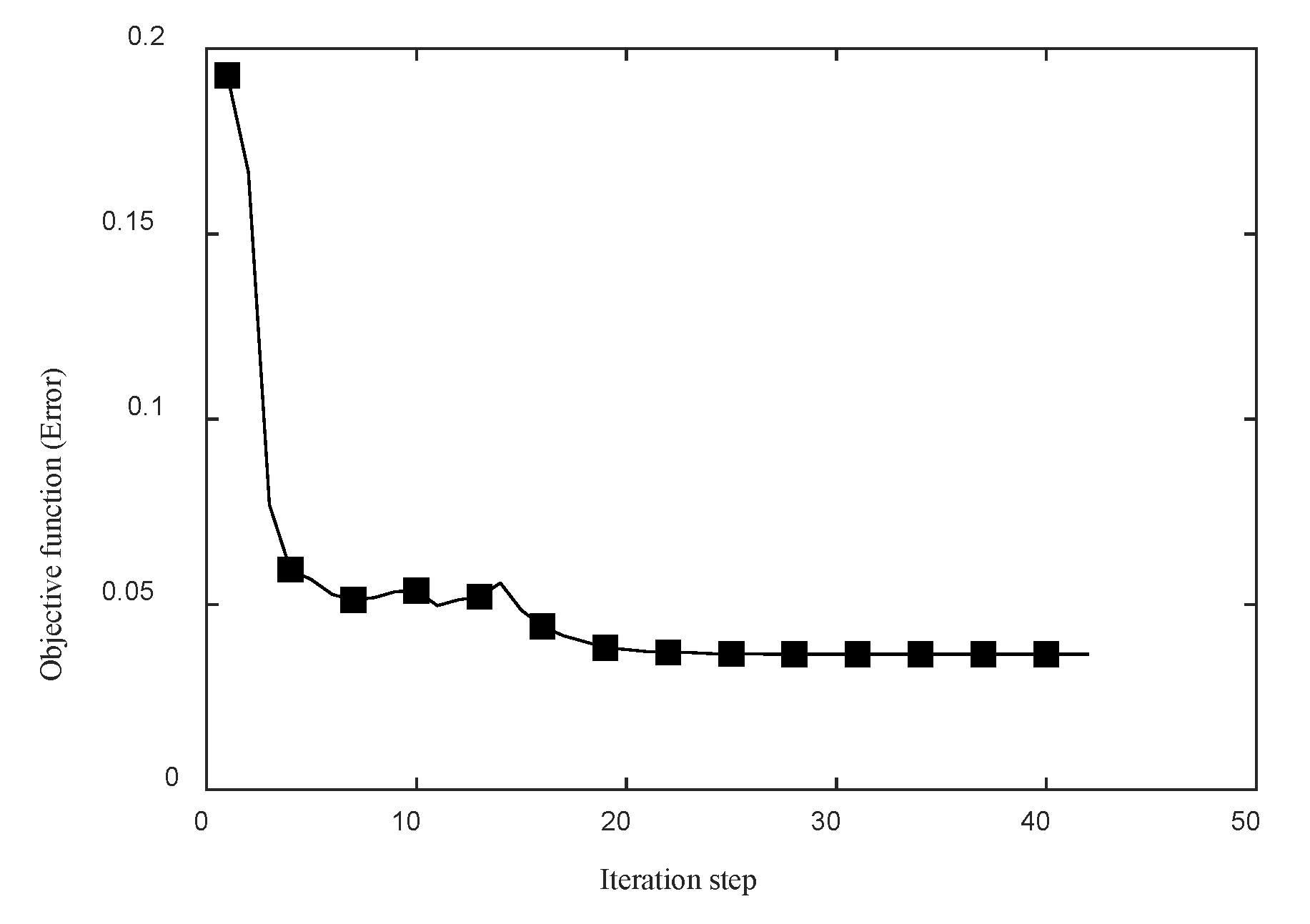

This paper focuses on flexible PV support structures, conducting field modal testing and proposing a modal property identification method based on multi-source data fusion. The high-order modal properties of the actual flexible PV structures were obtained through field measurements. Based on the measured modal properties, response surface-based FE model updating of the flexible PV support structure was accomplished. The following conclusions can be drawn from the study:

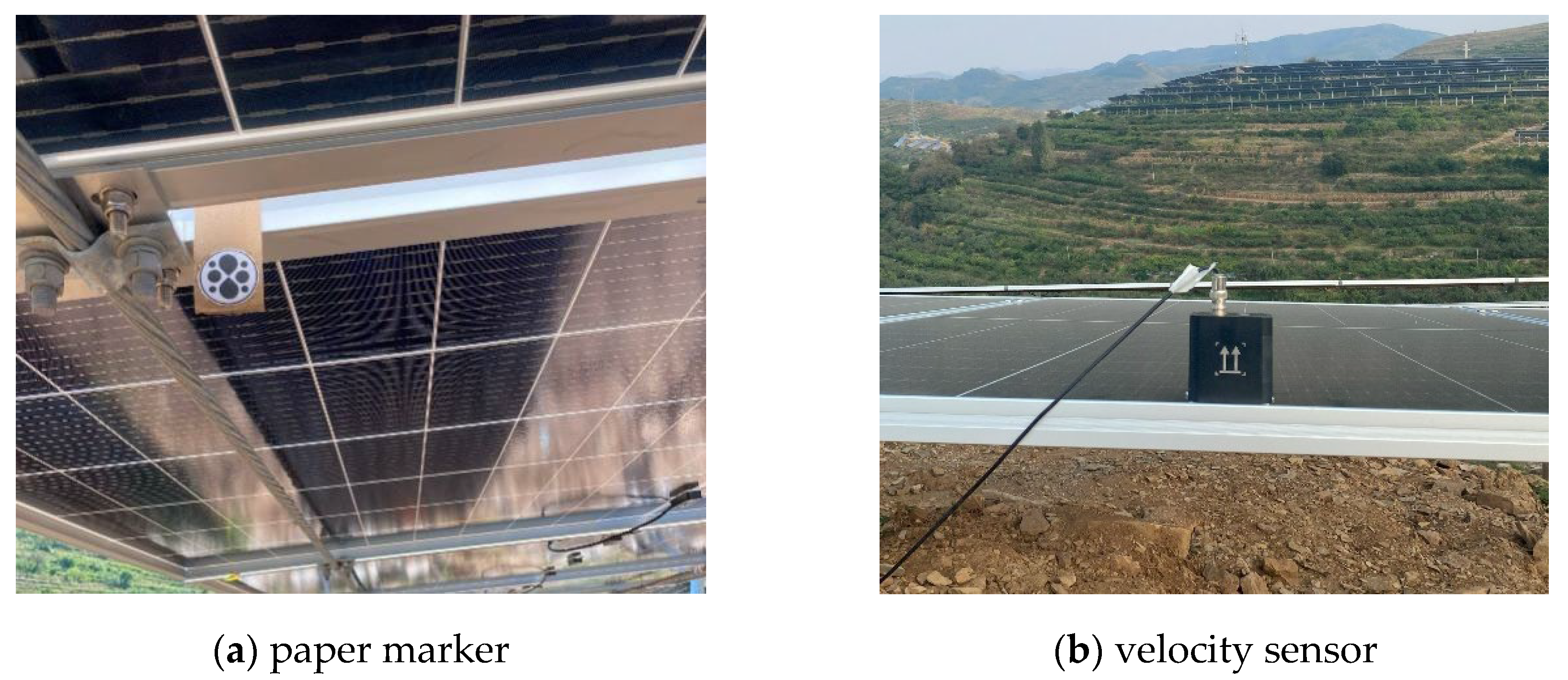

(1) The effectiveness of the field modal testing method was verified. The results indicate that the computer vision-based measurement enables high-precision identification of the lower-order vibration modes of the PV support structure. For high-order modes, due to weaker vibration energy, it is necessary to comprehensively analyze the data from both the computer vision system and velocity sensors.

(2) The first four modal properties of the flexible PV support structure were identified. It is noteworthy that the damping ratios of the first- and second-order torsional modes are only 0.7% and 0.4%, respectively, indicating that the low-damping characteristics of the flexible PV structure should be given particular attention in the design practice.

(3) A response surface-based finite element model updating method for flexible PV support structures was proposed. The high fitting accuracy of the response surface surrogate model demonstrates its feasibility as an alternative to full finite element analyses. The updated finite element model shows its dynamic characteristics closely match to the actual structure.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for modal property identification and FE model updating of flexible PV support structure.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for modal property identification and FE model updating of flexible PV support structure.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the mode shape identification from modal responses.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the mode shape identification from modal responses.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of response surface-based FE model updating.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of response surface-based FE model updating.

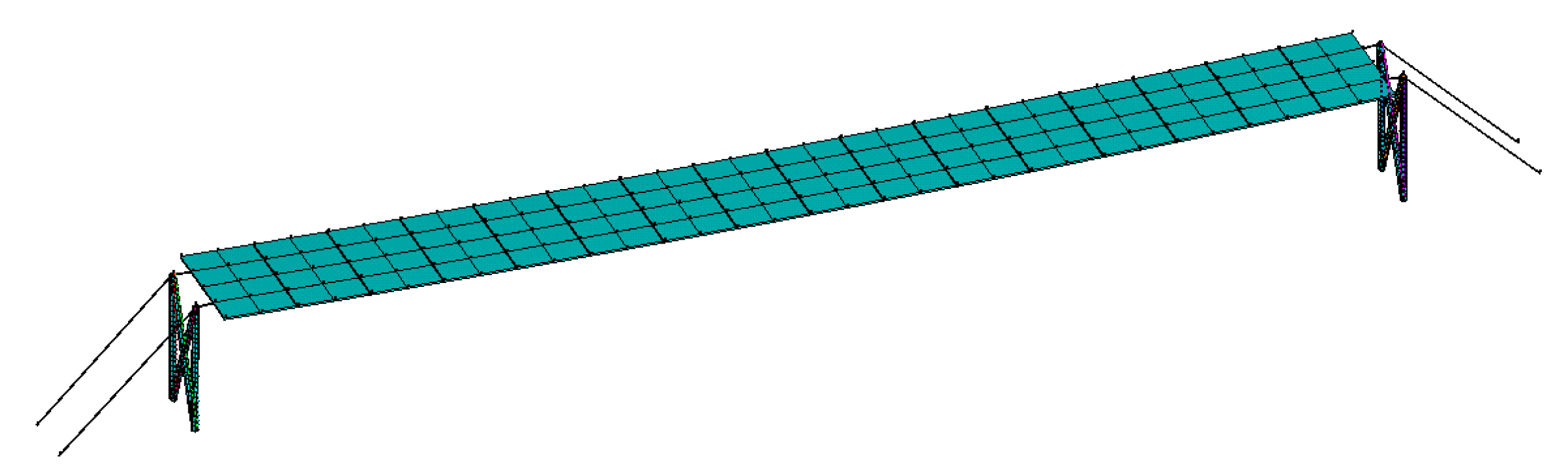

Figure 4.

Flexible PV support structure.

Figure 4.

Flexible PV support structure.

Figure 5.

FE model of the PV support structure.

Figure 5.

FE model of the PV support structure.

Figure 6.

The first four mode shapes of the PV support structure.

Figure 6.

The first four mode shapes of the PV support structure.

Figure 7.

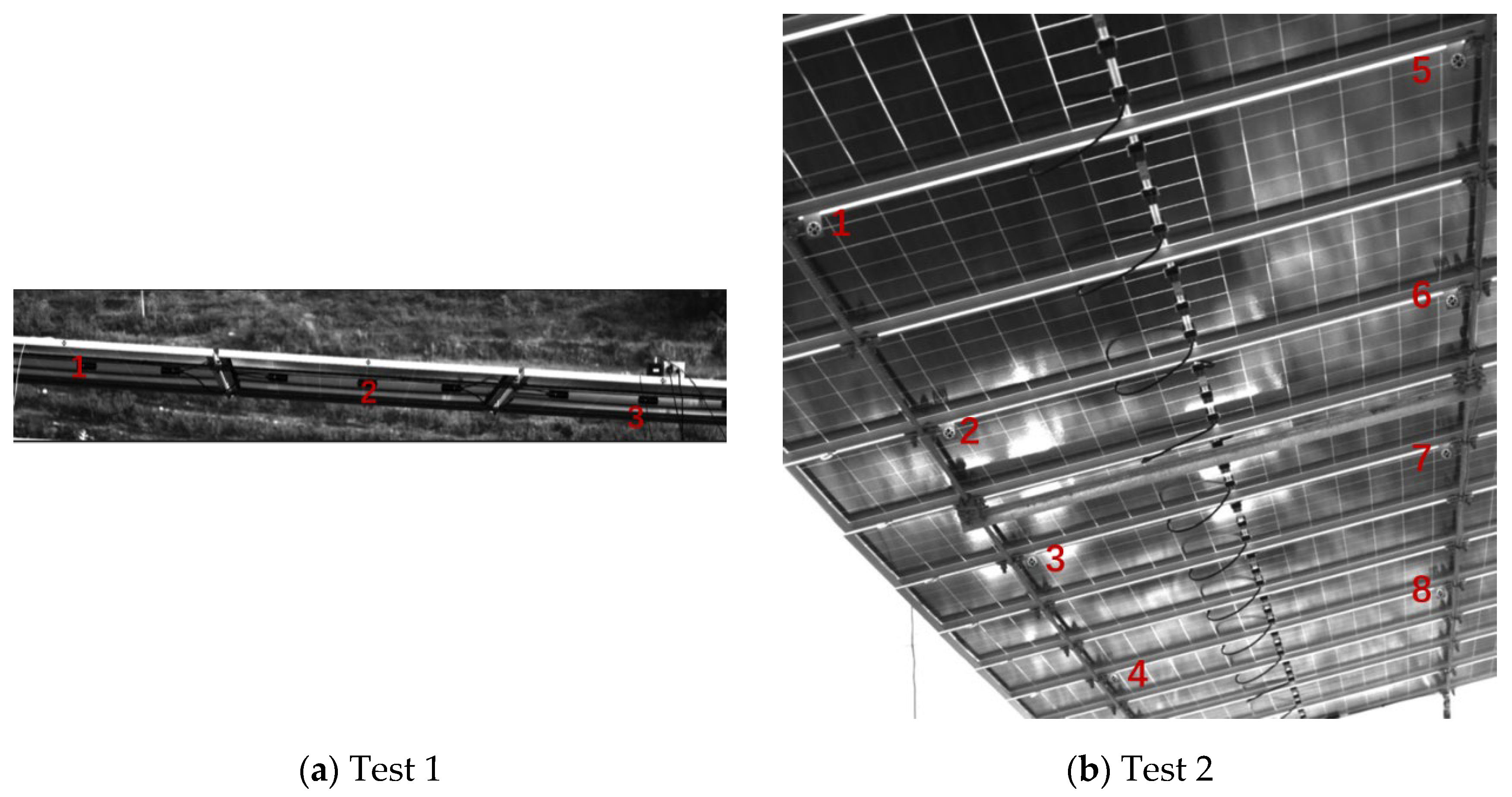

Attachment of the paper markers and velocity sensors to the PV support structure.

Figure 7.

Attachment of the paper markers and velocity sensors to the PV support structure.

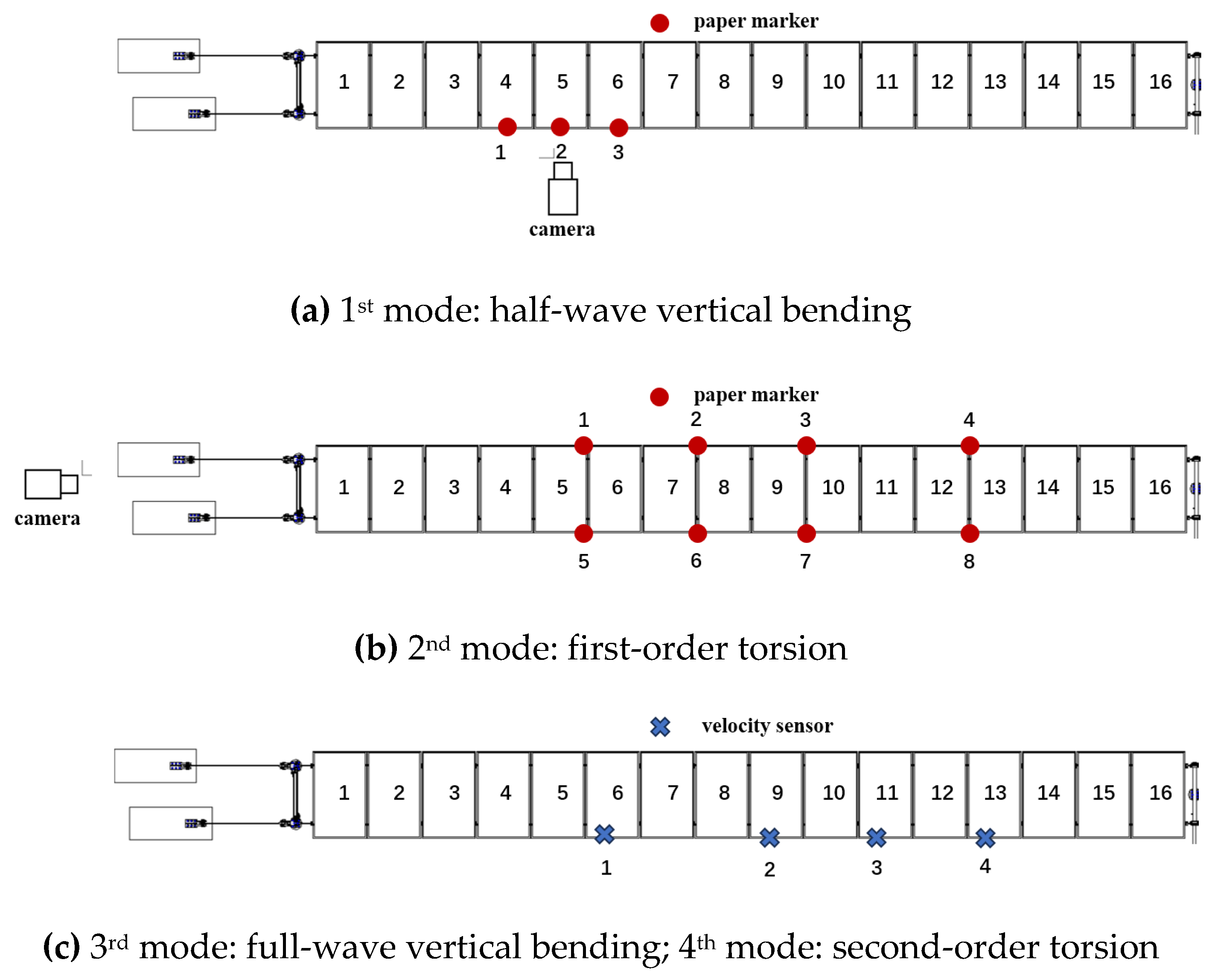

Figure 8.

Sensor placements.

Figure 8.

Sensor placements.

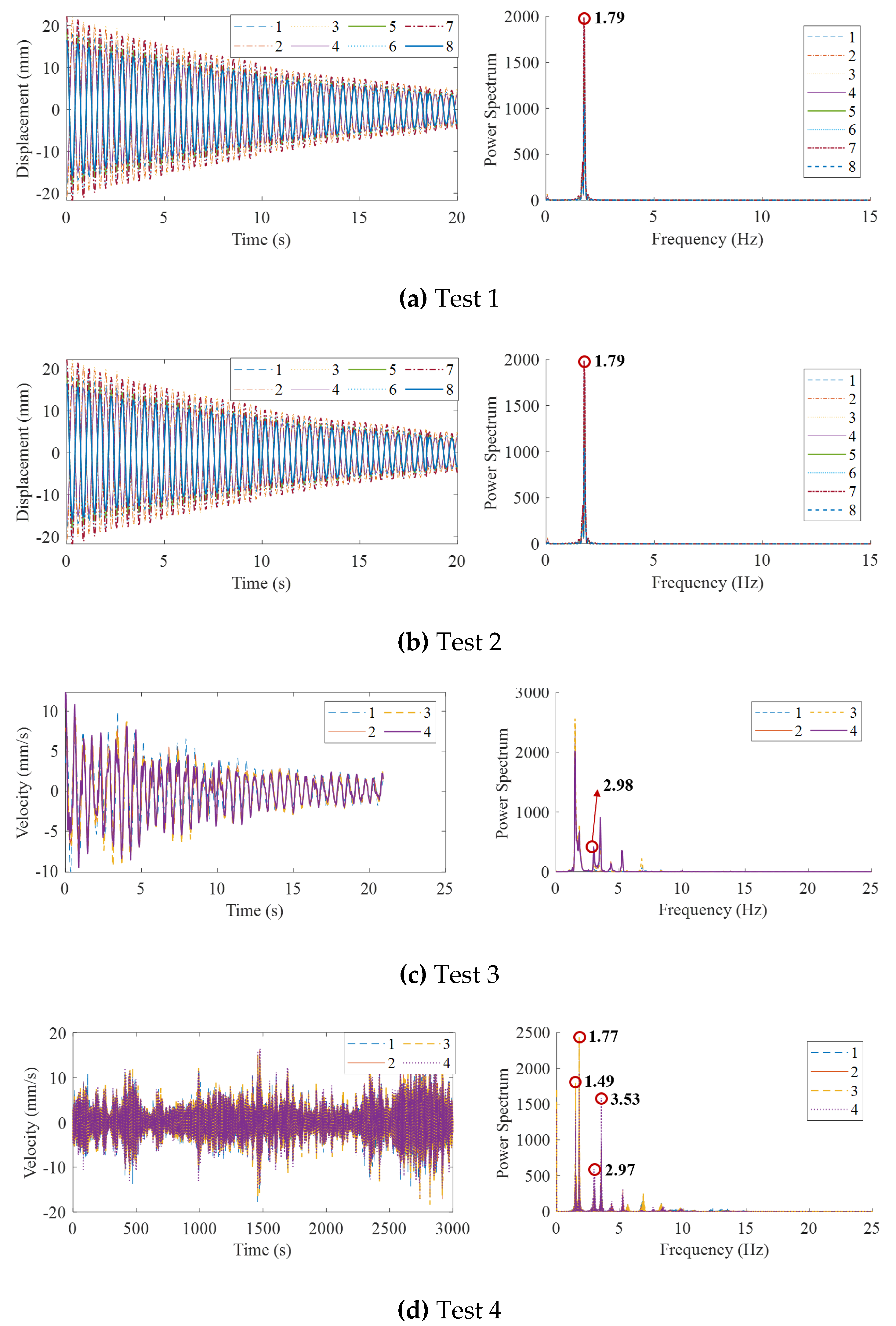

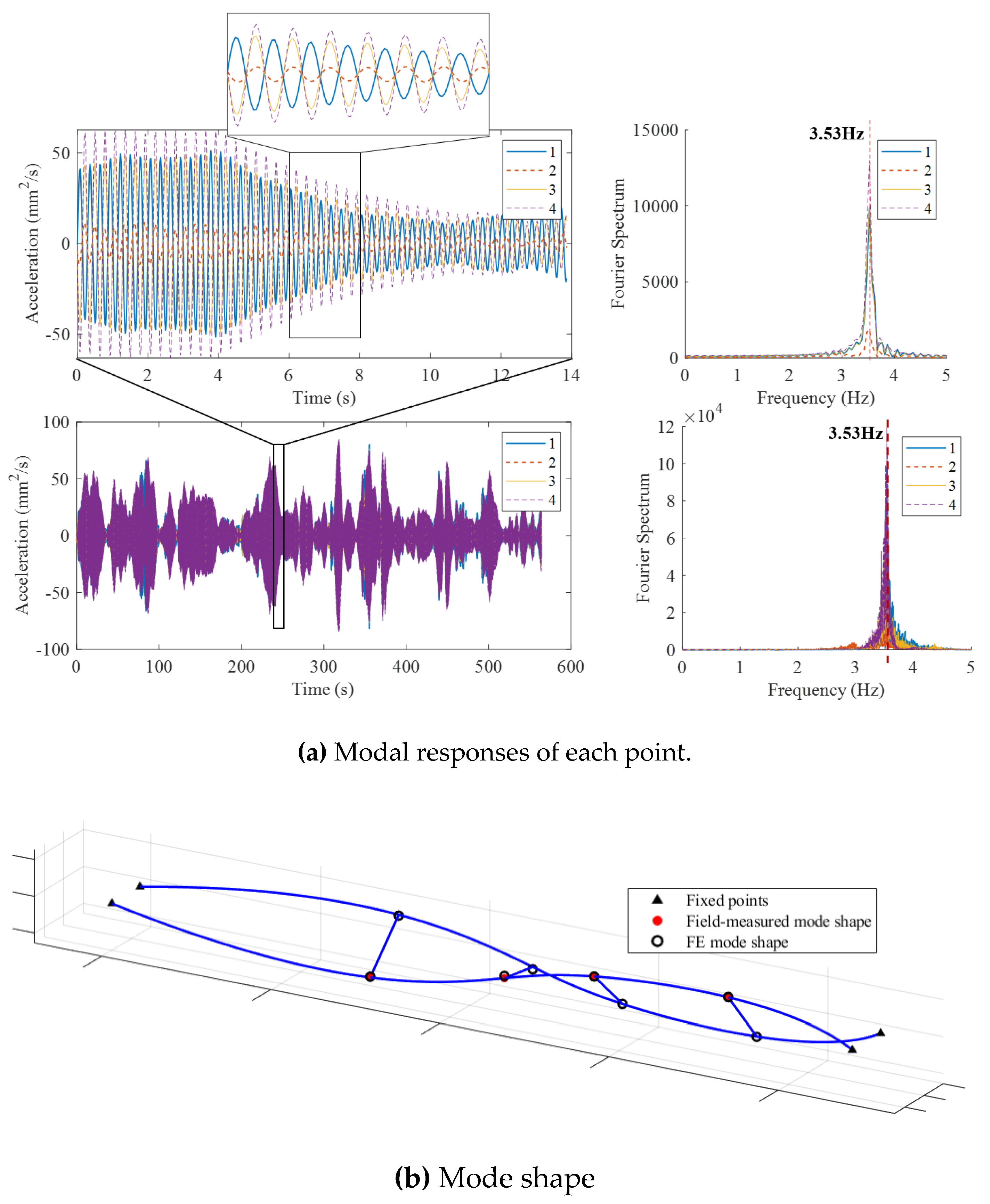

Figure 10.

Time history and spectra of test 1 to test 4.

Figure 10.

Time history and spectra of test 1 to test 4.

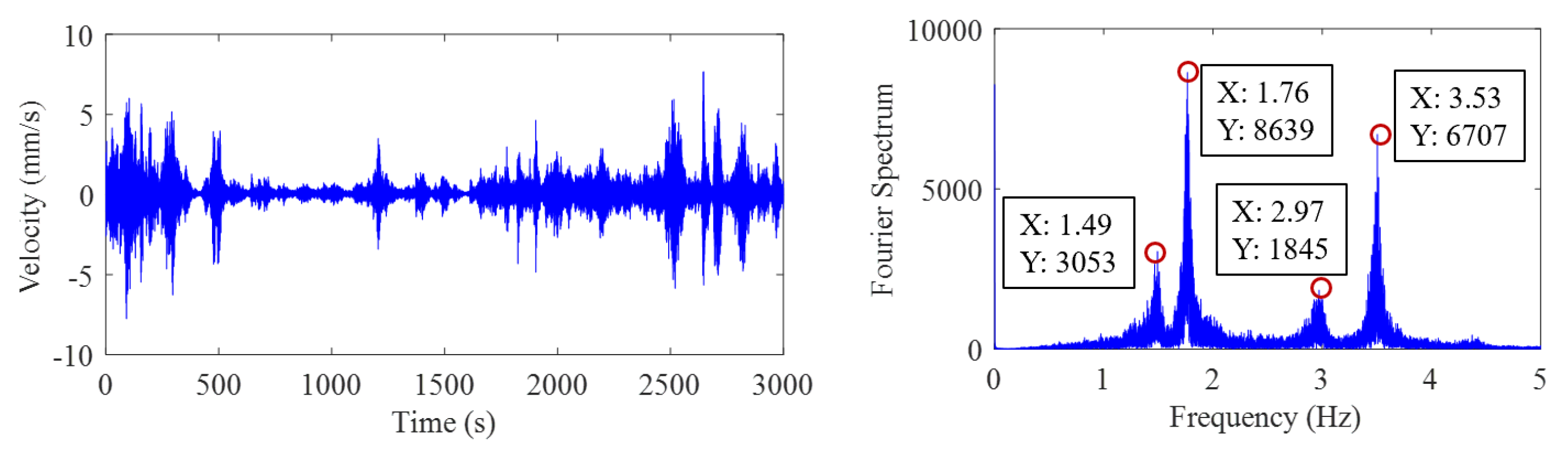

Figure 11.

Time history and spectrum of test 4.

Figure 11.

Time history and spectrum of test 4.

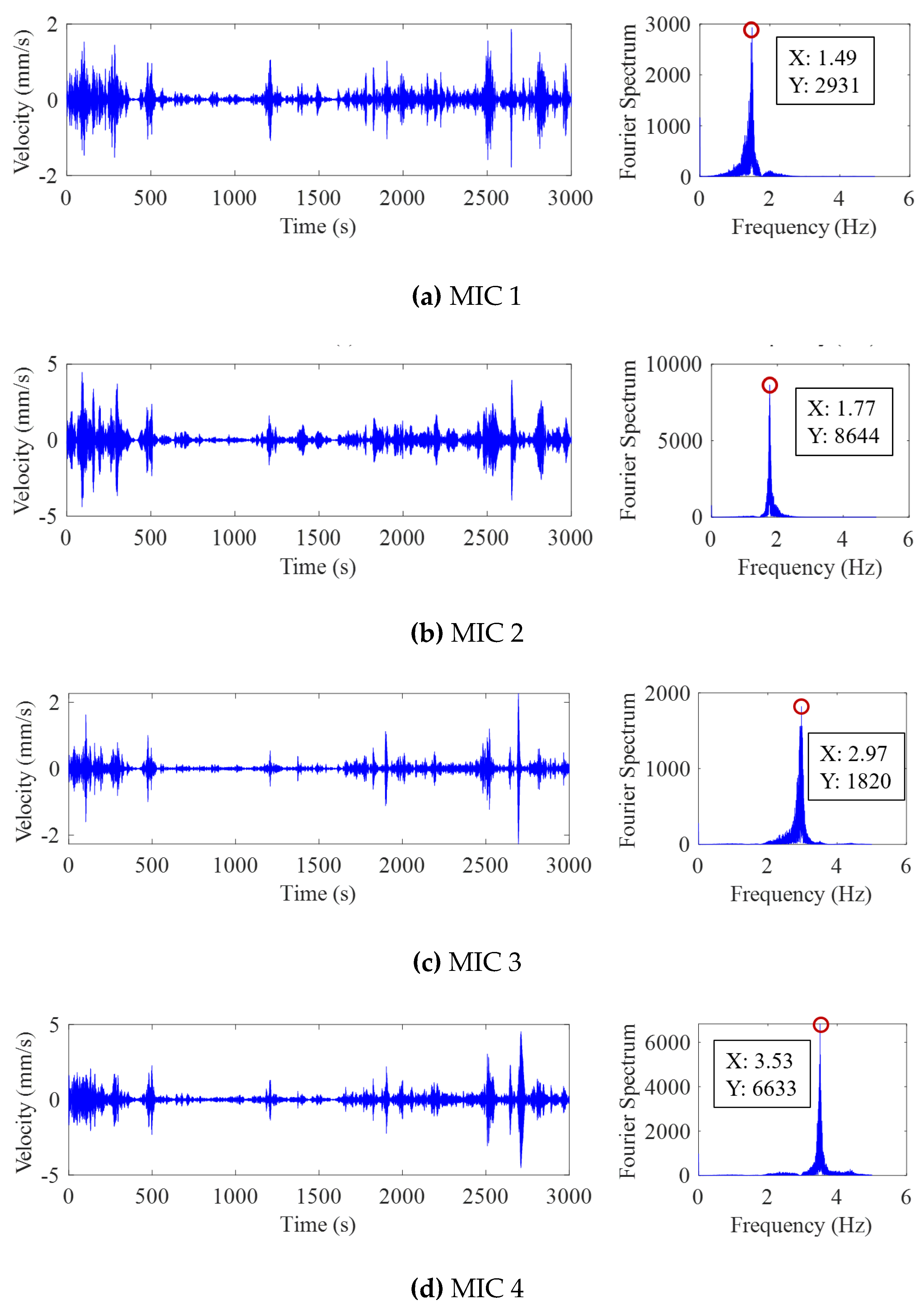

Figure 12.

Time history and spectrum of derived components by the VMD for test 4.

Figure 12.

Time history and spectrum of derived components by the VMD for test 4.

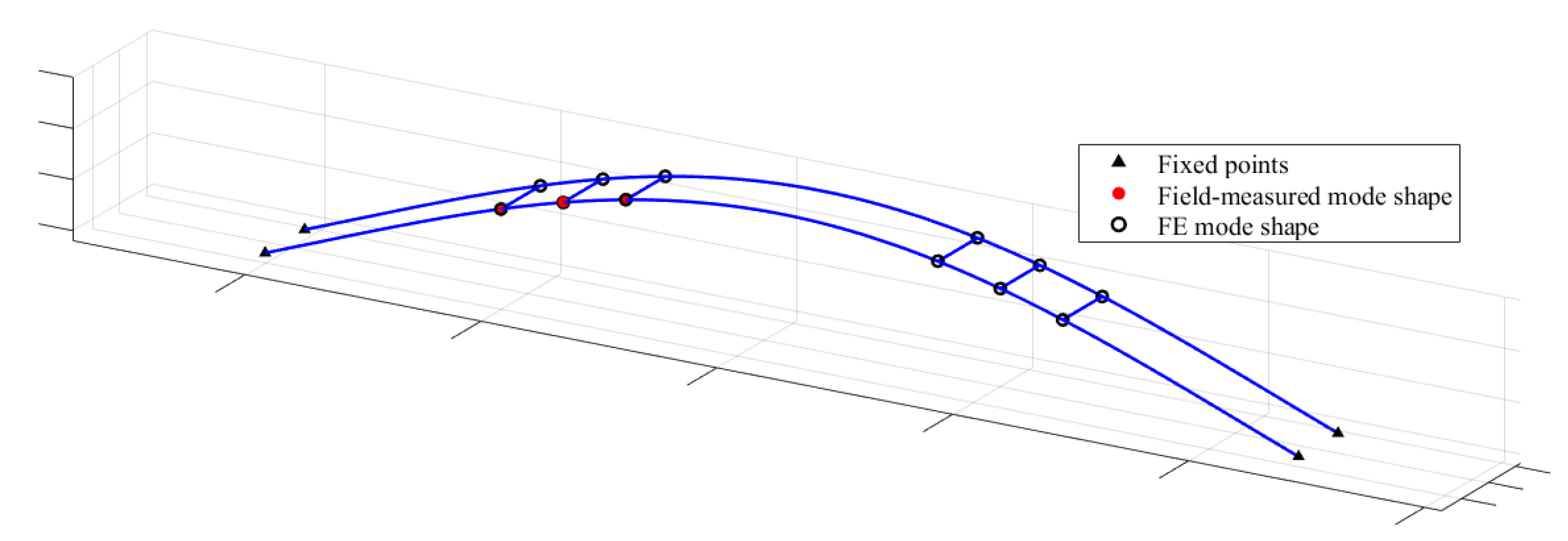

Figure 13.

Second-order torsional spatial mode shape.

Figure 13.

Second-order torsional spatial mode shape.

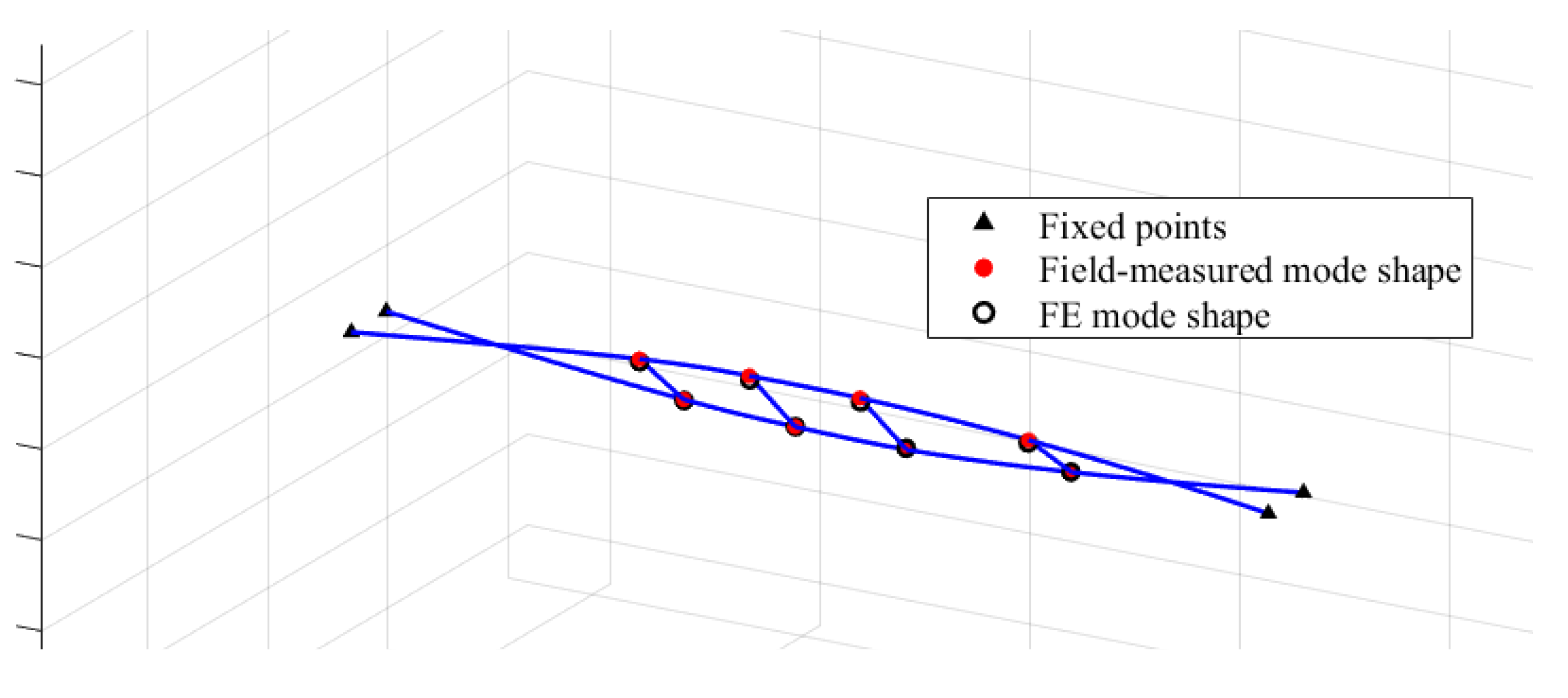

Figure 14.

Half-wave vertical bending mode shape.

Figure 14.

Half-wave vertical bending mode shape.

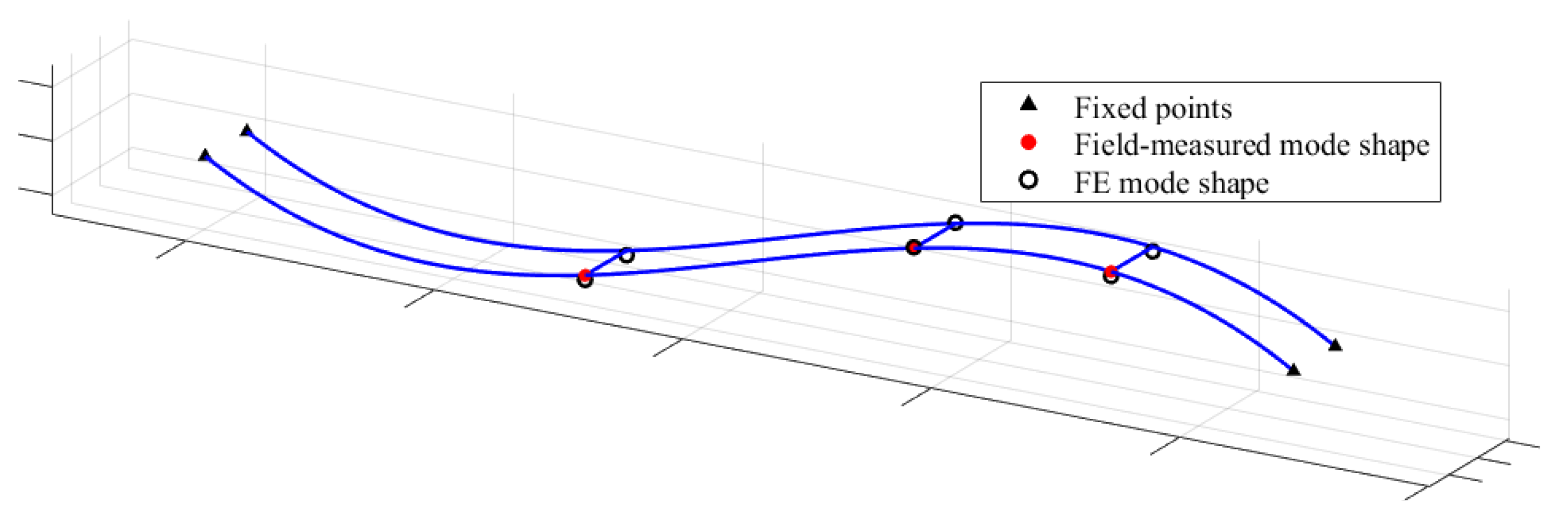

Figure 15.

First-order torsional spatial mode shape.

Figure 15.

First-order torsional spatial mode shape.

Figure 16.

Full-wave vertical bending mode shape.

Figure 16.

Full-wave vertical bending mode shape.

Figure 17.

Response surface fitting results.

Figure 17.

Response surface fitting results.

Figure 18.

Convergence curve of the objective function.

Figure 18.

Convergence curve of the objective function.

Table 1.

Summary of the test cases.

Table 1.

Summary of the test cases.

| Test cases |

Target mode |

Excitation method |

Sensor type |

Placement method |

Test duration |

| 1 |

half-wave vertical bending |

1/2 span, vertical harmonic loads |

Vison-based measurement |

Fig. 5(a) |

5 min |

| 2 |

first-order torsion |

1/2 span, vertical synchronized opposite-direction harmonic loads |

Vison-based measurement |

Fig. 5(b) |

5 min |

| 3 |

full-wave vertical bending |

1/4 and 3/4 span, vertical synchronized opposite-direction harmonic loads |

Velocity sensor |

Fig. 5(c) |

5 min |

| 4 |

second-order torsion |

Wind excitation |

Velocity sensor |

Fig. 5(c) |

120 min |

Table 2.

Identified frequencies and damping ratios.

Table 2.

Identified frequencies and damping ratios.

| mode |

|

by SH |

by HT |

| 1 |

1.488 |

0.0172 |

0.0155 |

| 2 |

1.775 |

0.0065 |

0.0071 |

| 3 |

2.980 |

0.0098 |

0.013 |

| 4 |

3.526 |

0.0035 |

0.0043 |

Table 3.

Comparison of mode shapes from field identification and FE model.

Table 3.

Comparison of mode shapes from field identification and FE model.

| Mode |

Method |

Mode shape vector |

1-MAC |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

| 1 |

Field-

measured |

0.73 |

0.88 |

1 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

3.33×10-6

|

| FEM |

0.72 |

0.88 |

1 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| 2 |

Field-

measured |

0.88 |

1 |

0.99 |

0.74 |

-0.88 |

-1 |

-0.99 |

-0.74 |

8.38×10-5

|

| FEM |

0.86 |

1 |

1 |

0.73 |

-0.86 |

-0.1 |

-0.99 |

-0.73 |

| 3 |

Field-

measured |

0.69 |

/ |

-0.75 |

1 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

5.18×10-2

|

| FEM |

0.82 |

/ |

-0.82 |

1 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| 4 |

Field-

measured |

0.83 |

0.15 |

-0.79 |

1 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

3.41×10-2

|

| FEM |

0.79 |

0.18 |

-0.79 |

1 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

Table 4.

Comparison of field-measured and FE analysis modal frequencies.

Table 4.

Comparison of field-measured and FE analysis modal frequencies.

| Response features |

Modal frequencies (Hz) |

Relative error (%) |

| FE |

Field-measured |

| f1 |

1.693 |

1.488 |

13.78 |

| f2 |

2.205 |

1.775 |

24.22 |

| f3 |

3.081 |

2.980 |

3.38 |

| f4 |

4.242 |

3.526 |

20.31 |

Table 5.

Range of updating parameter values.

Table 5.

Range of updating parameter values.

| Updating parameters |

Initial value |

Lower bound |

Upper bound |

|

(kN) |

60 |

36 |

60 |

|

(kg) |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

Table 6.

Fitting validation.

Table 6.

Fitting validation.

| Index |

f1 |

f2 |

f3 |

f4 |

| R2

|

0.998 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

0.998 |

| RMSE |

2.10×10-3

|

2.00×10-3

|

5.79×10-4

|

1.230×10-2

|

Table 7.

Optimization results of updating parameters.

Table 7.

Optimization results of updating parameters.

| Updating parameter |

Initial |

Optimization |

|

(kg) |

0 |

2.00 |

|

(kN) |

60 |

51.96 |