Submitted:

03 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Criticality Metrics

2.2. Analytical Hierarchy Process

3. Methodology

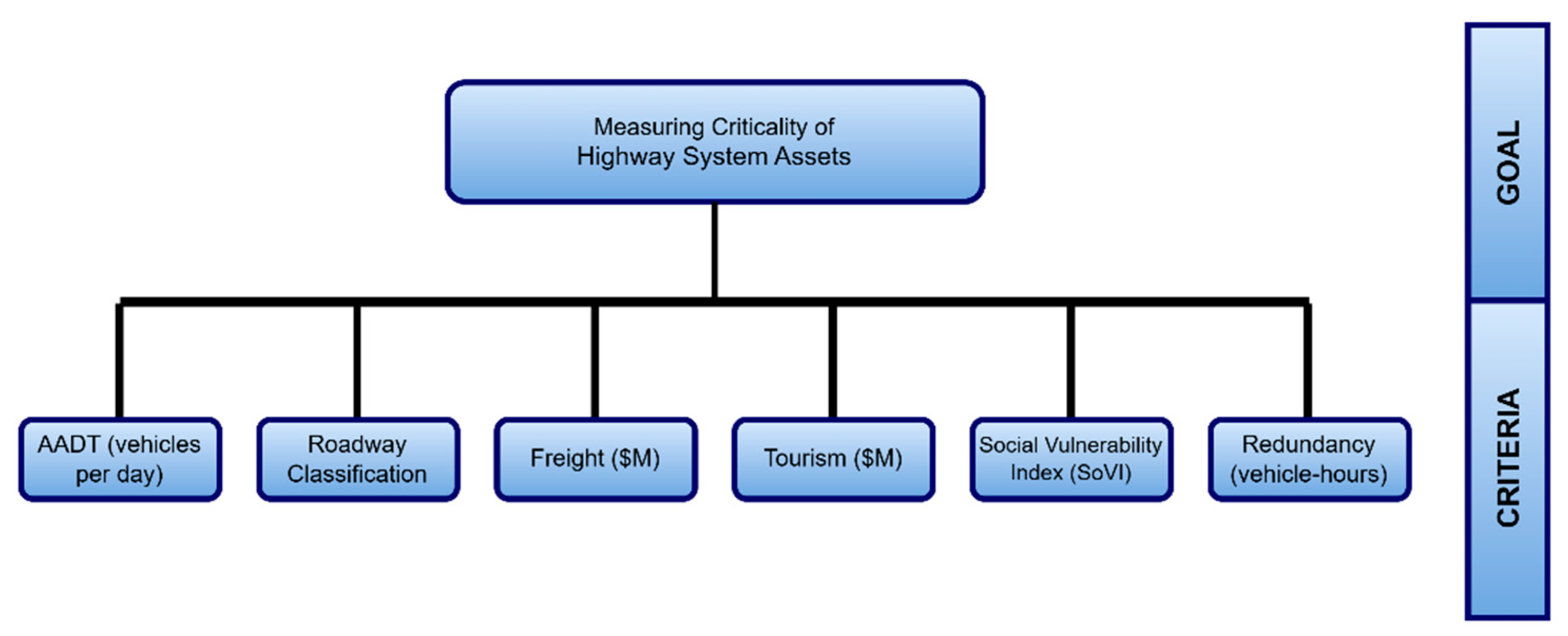

- Define the hierarchical structure consisting of the goal and criteria,

- Collect the input data by pairwise comparisons of criteria through survey,

- Calculate consistency ratios from the individuals’ set of judgments and individual priorities for each set of pairwise comparison, and

- Compute the overall criteria weights by aggregation of individual priorities (AIP).

3.1. Hierarchical Framework and Definitions

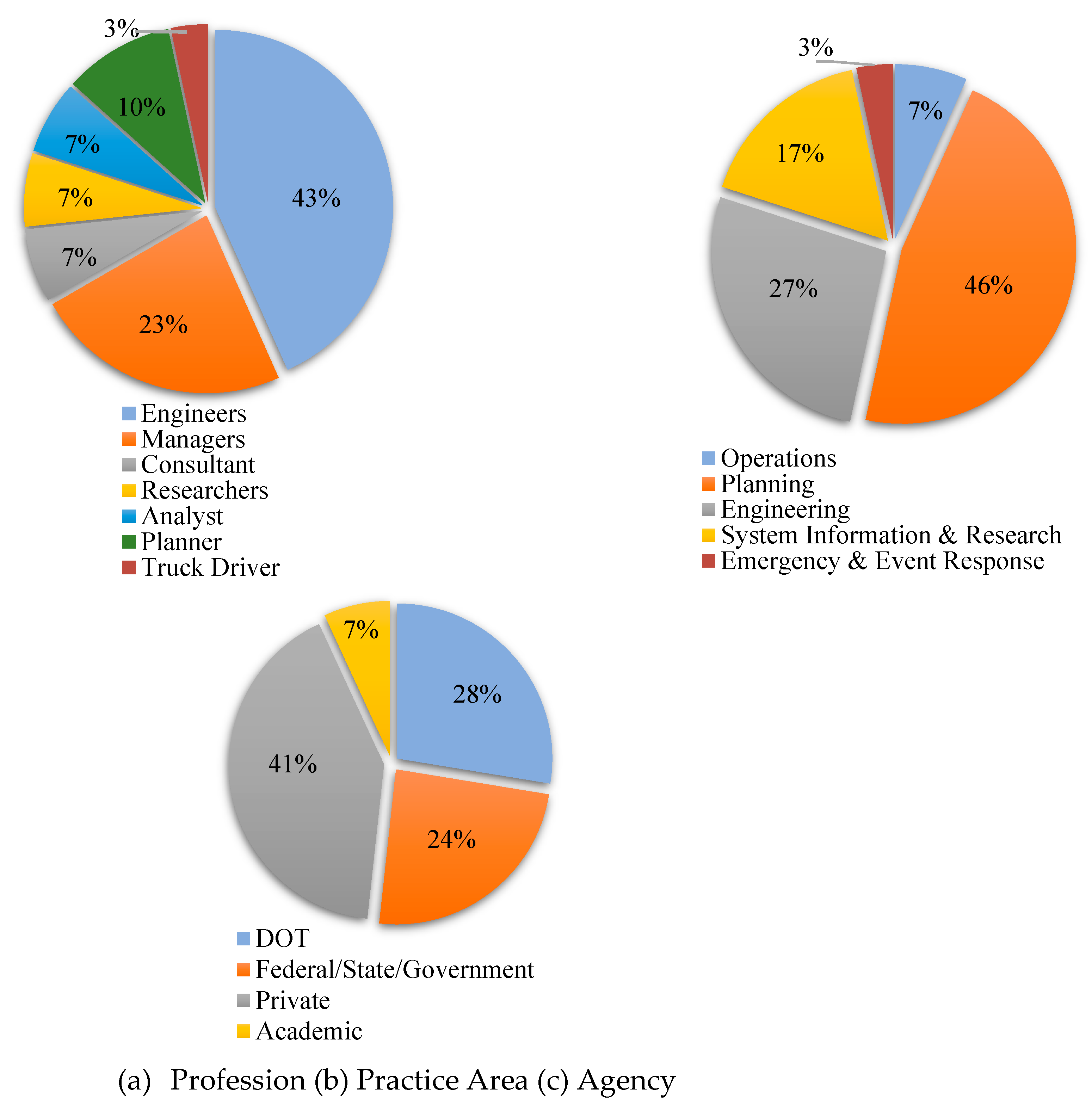

3.2. Input Data Collection via Online Survey

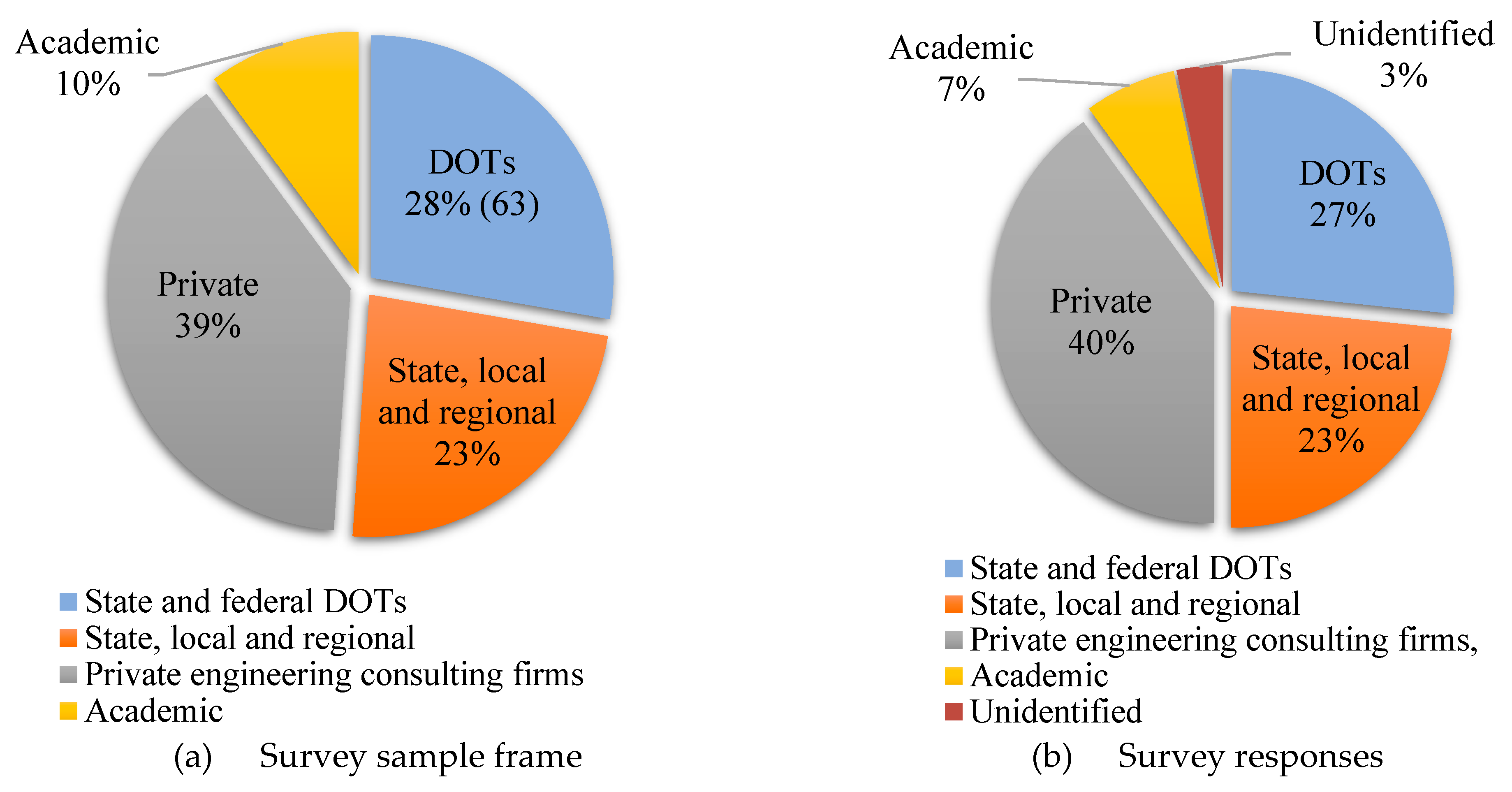

3.3. Survey Sample Size

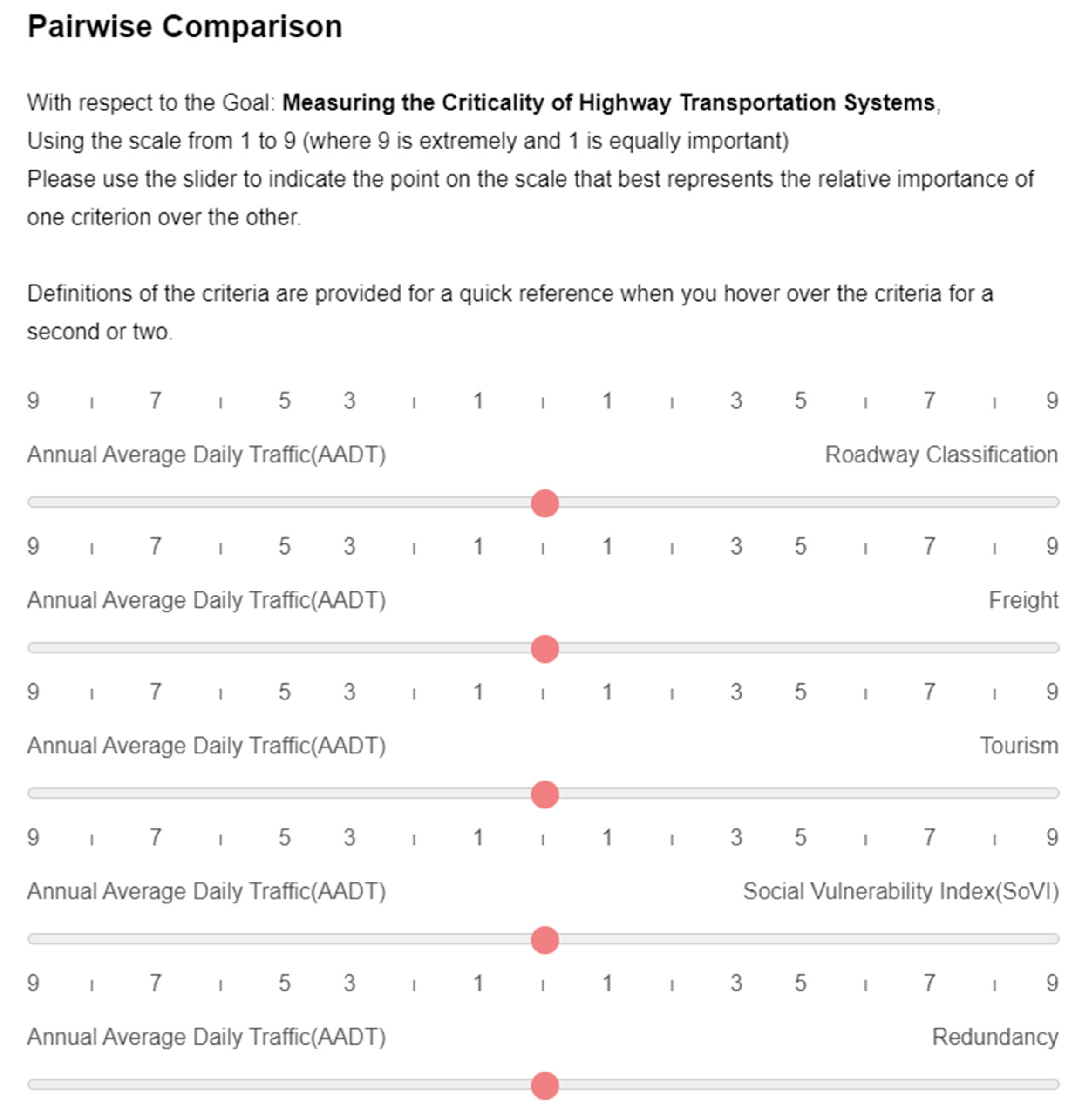

3.4. Survey Questionnaire

3.5. Consistency Ratio Calculations

- CI is the Consistency Index calculated as .

- is the largest principal eigenvalue of a positive reciprocal pairwise comparison matrix of size (number of criteria).

3.6. Criteria Weights

- is the arithmetic mean of the j-th criterion

- is the geometric mean of the j-th criterion

- is the normalized vector of individual priorities of the i-th expert and j-th

- criterion

- n is the number of expert individuals

- m is the number of criteria

- is a set of normalized eigenvector components.

- is a set of eigenvector components.

4. Results

4.1. Response Rates by Sector

4.2. Consistency Ratios of Responses

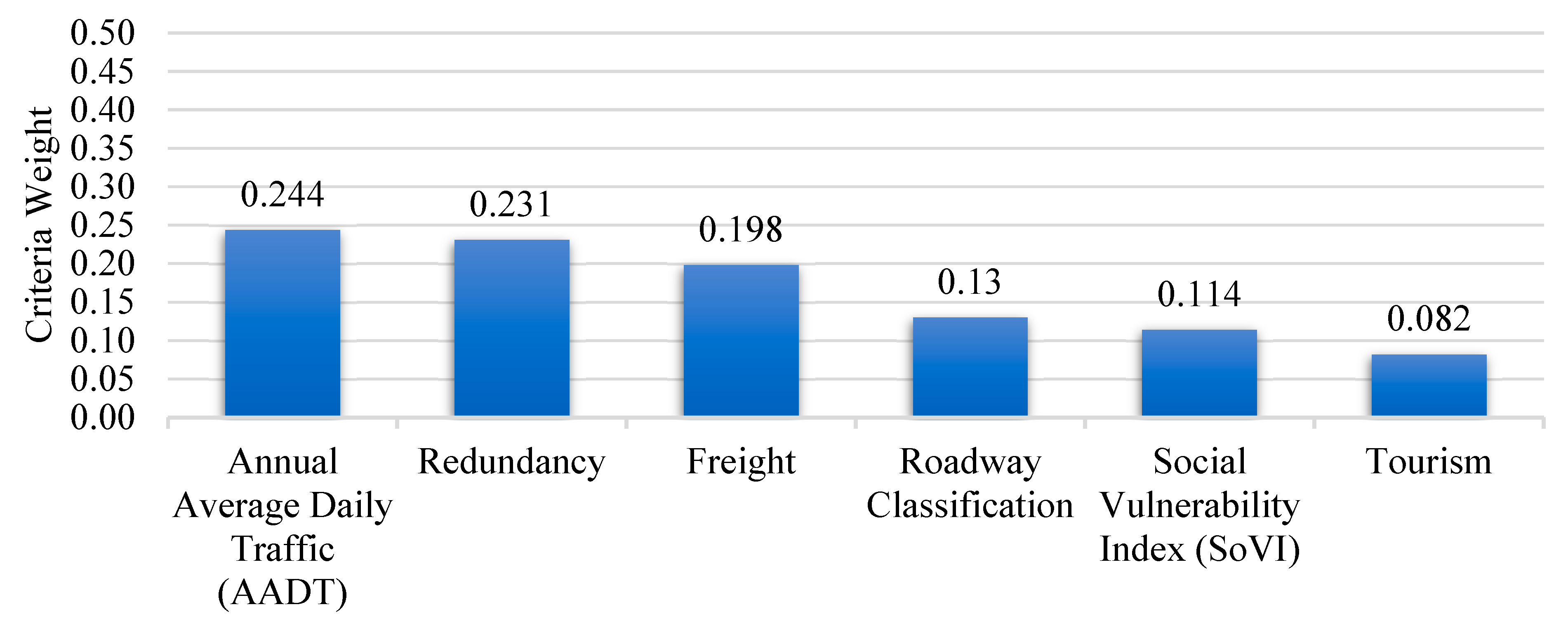

4.3. Overall Criteria Weights

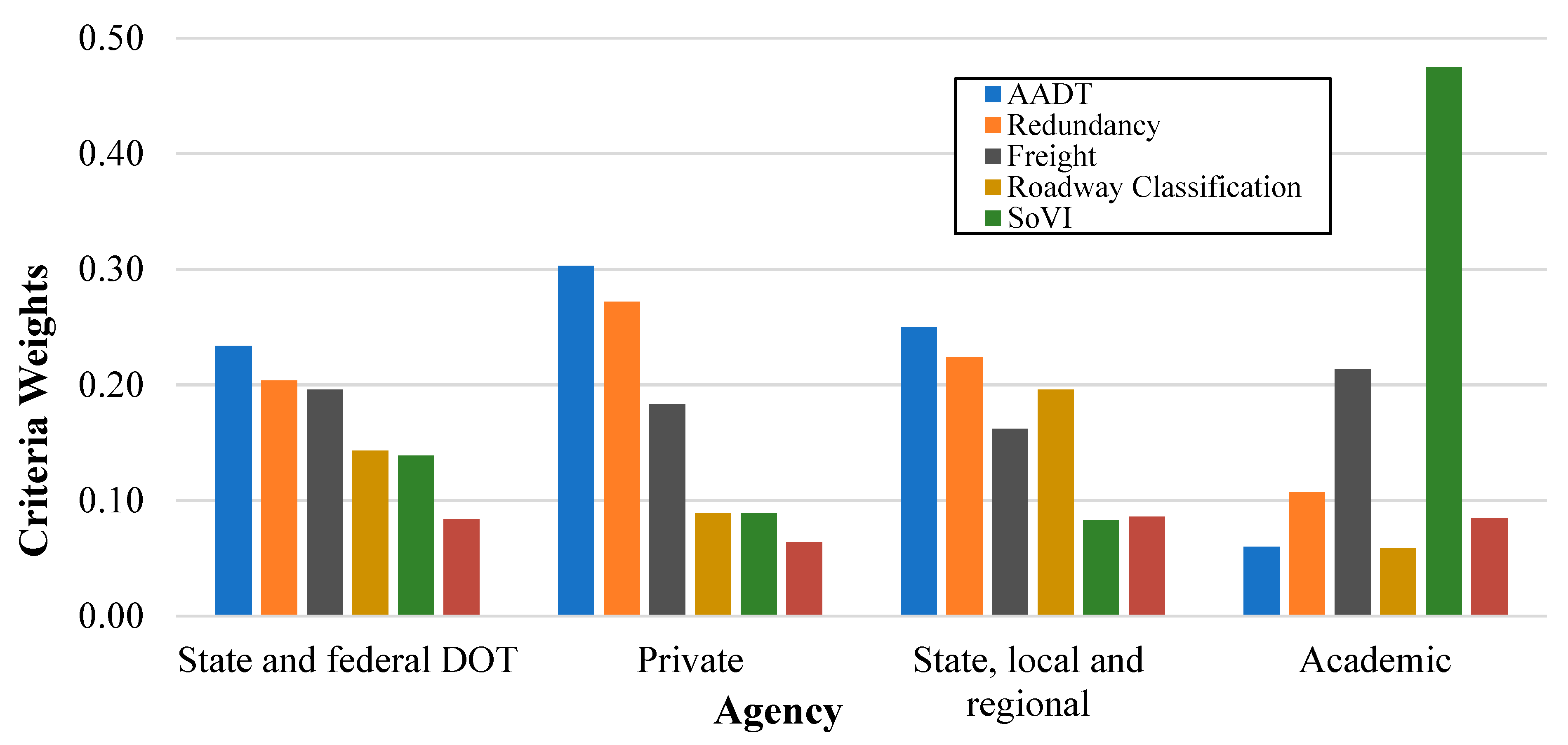

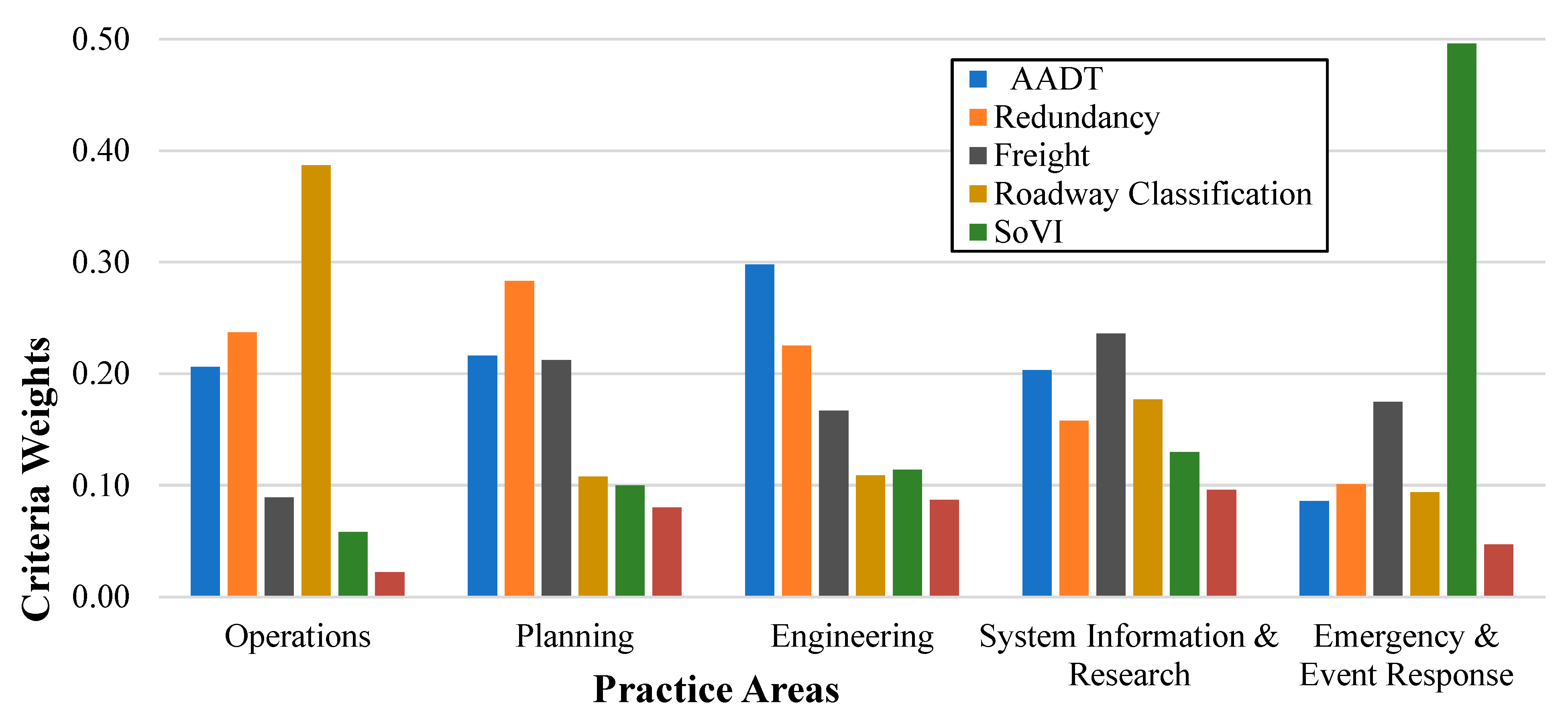

4.3. Criteria Weights by Stakeholder Group

- AADT ranked first by state and federal DOTs, private engineering consulting firms, and state, local and regional governmental transportation agencies groups while placing fifth in the academic group. AADT ranked first by the respondents from engineering, second by planning and system information and research (SIR) groups, third by operations, and fifth by emergency and event response (EER).

- Redundancy was ranked second by state and federal DOTs, private engineering consulting firms and state, local and regional governmental transportation agencies groups while placing third in the academic group. Redundancy ranked first by the planning with operations and engineering groups ranking it second. It was ranked third and fourth by EER and SIR respectively.

- Freight value had a varied ranking, ranking second by the academic group, third amongst state and federal DOTs and private engineering consulting firms while ranking fourth by state, local and regional governmental transportation agencies group. Experts in the SIR sector ranked freight first, second by EER, third by both planning and engineering, and fourth by the operations practice area.

- Roadway classification ranked third by state, local and regional government transportation agencies group while it ranked fourth by the other stakeholder groups. Roadway classification was the highest-ranked criterion by respondents working in the field of operations with a value of 0.387. It, however, ranked third by SIR, fourth by planning and EER, and finally fifth by engineering.

- SoVI ranked first by respondents from academia with a very high criteria weight of 0.475, placing fourth, fifth, and sixth by the state and federal DOTs, private engineering consulting firms and state, local and regional governmental transportation agencies respondents respectively. SoVI ranked first by the respondent from EER with a very high criteria weight of 0.496. It, however, fell to fourth place ranking by the engineering field and fifth across the remaining practice areas.

- Tourism ranked sixth across the state and federal DOTs and private engineering consulting firms groups but was ranked fourth and fifth by the experts from the academia and state, local and regional governmental transportation agencies respectively. Tourism was unanimously ranked sixth by all the practice area groups which is consistent with the overall criteria ranking.

4.4. Criteria Hierarchy Effects on Ranking

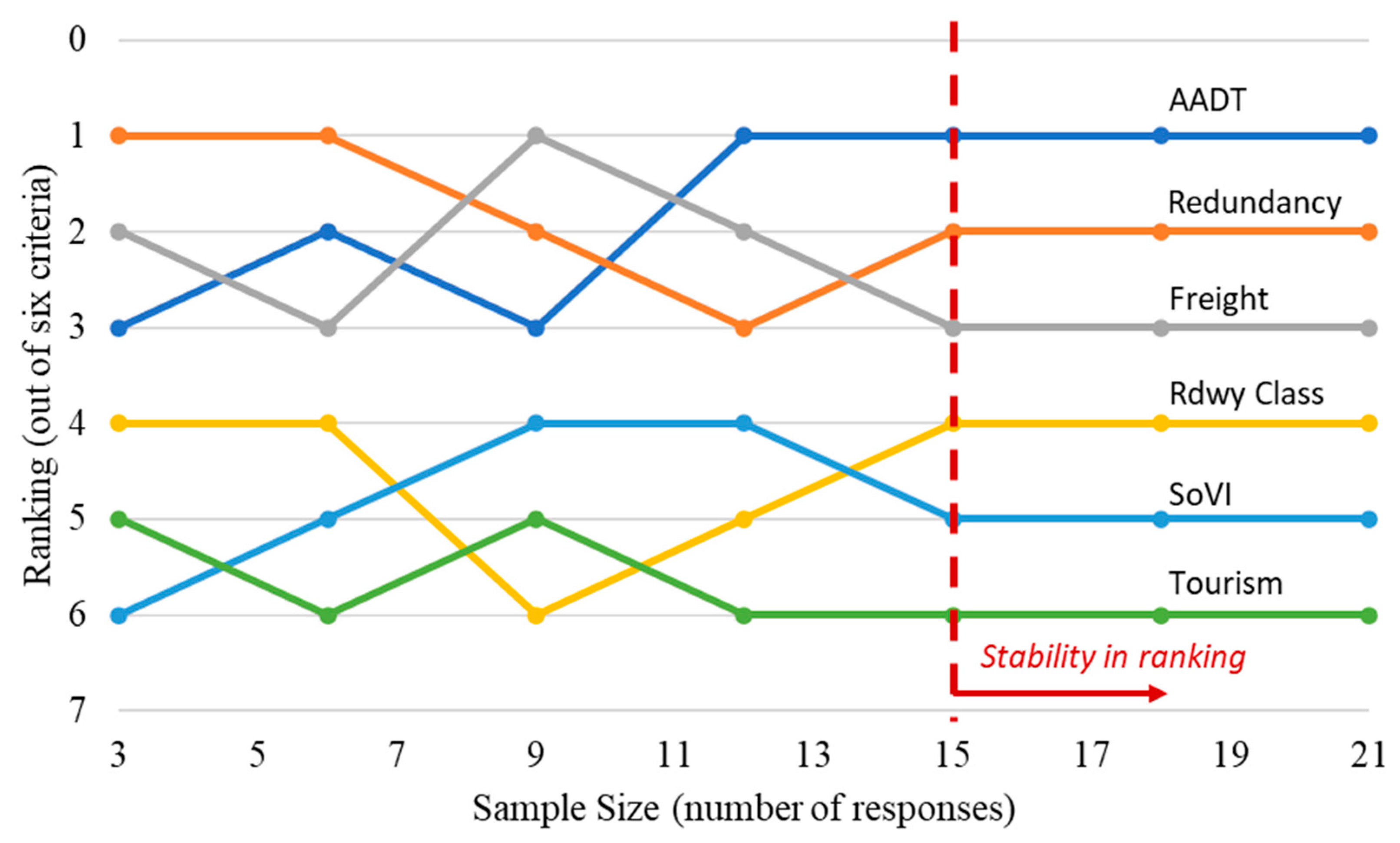

4.5. Sample Size Effects on Ranking

4.6. Application

- AADT is 500 vehicles per day and assigned Level 1.

- Redundancy is estimated to be 1600 vehicle hours and assigned Level 3.

- Freight value is $1000M and assigned Level 2.

- Roadway class is a minor arterial and assigned Level 2.

- SoVI is estimated to be 1.55 and assigned Level 4.

- Tourism value is $2M and assigned Level 1.

- is the combined criticality score for each link i

- is the weight assigned to each criterion, n, e.g., AHP deduced weights

- is the score of the criterion, n, for each link i

- is the number of criteria, e.g., N=6.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sullivan, J.L.; Novak, D.C.; Aultman-Hall, L.; Scott, D.M. Identifying Critical Road Segments and Measuring System-Wide Robustness in Transportation Networks with Isolating Links: A Link-Based Capacity-Reduction Approach. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2010, 44, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Palomares, J.C.; Gutiérrez, J.; Martín, J.C.; Moya-Gómez, B. An Analysis of the Spanish High Capacity Road Network Criticality. Transportation 2018, 45, 1139–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, S.B. Transportation Network Resiliency: A Study of Self-Annealing. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jenelius, E.; Petersen, T.; Mattsson, L.-G. Importance and Exposure in Road Network Vulnerability Analysis. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2006, 40, 537–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, A. I-70 Corridor Risk & Resilience Pilot. 105.

- Board, T.R. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering; Medicine Investing in Transportation Resilience: A Framework for Informed Choices; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Almotahari, A.; Yazici, M.A. A Link Criticality Index Embedded in the Convex Combinations Solution of User Equilibrium Traffic Assignment. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2019, 126, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almotahari, A.; Yazici, A. Impact of Topology and Congestion on Link Criticality Rankings in Transportation Networks. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2020, 87, 102529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FHWA Climate Resilience Pilot Program: Connecticut Department of Transportation. 2016.

- Smith, J.T.; Tighe, S.L. Analytic Hierarchy Process as a Tool for Infrastructure Management. Transportation Research Record 1974, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almotahari, A.; Yazici, A. Practice Friendly Metric for Identification of Critical Links in Road Networks. Transportation Research Record 2020, 2674, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagurney, A.; Qiang, Q. A Transportation Network Efficiency Measure That Captures Flows, Behavior, and Costs With Applications to Network Component Importance Identification and Vulnerability. SSRN Journal 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, P.; Furno, A.; El Faouzi, N.-E. Road Network Resilience: How to Identify Critical Links Subject to Day-to-Day Disruptions. Transportation Research Record 2018, 2672, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenelius, E.; Petersen, T.; Mattsson, L.-G. Importance and Exposure in Road Network Vulnerability Analysis. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2006, 40, 537–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madar-Vani, G.; Maoh, H.; Anderson, W. Modeling the Criticality of a Regional Trucking Network at the Industry Level: Evidence from the Province of Ontario, Canada. Research in Transportation Business & Management 2022, 43, 100732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafino, B.A. An Equity-Based Transport Network Criticality Analysis. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2021, 144, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.L.; Novak, D.C.; Aultman-Hall, L.; Scott, D.M. Identifying Critical Road Segments and Measuring System-Wide Robustness in Transportation Networks with Isolating Links: A Link-Based Capacity-Reduction Approach. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2010, 44, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Z.W.; Liu, H.; Szeto, W.Y.; Chow, A.H.F. Identification of Critical Combination of Vulnerable Links in Transportation Networks – a Global Optimisation Approach. Transportmetrica A: Transport Science 2016, 12, 346–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jia, H.; Luo, Q.; Li, Y.; Yang, L. Identification of Critical Links in a Large-Scale Road Network Considering the Traffic Flow Betweenness Index. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICF International Criticality Guidance - Tools - Resilience - Sustainability - Environment - FHWA. Available online: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/sustainability/resilience/tools/criticality_guidance/index.cfm (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Kumar, A.; Haque, K.; Mishra, S.; Golias, M.M. Multi-Criteria Based Approach to Identify Critical Links in a Transportation Network. Case Studies on Transport Policy 2019, 7, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukkusuri, S.V.; Yushimito, W.F. A Methodology to Assess the Criticality of Highway Transportation Networks. J Transp Secur 2009, 2, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ozbay, K. Evaluation of Link Criticality for Day-to-Day Degradable Transportation Networks. Transportation Research Record 2012, 2284, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.M.; Novak, D.C.; Aultman-Hall, L.; Guo, F. Network Robustness Index: A New Method for Identifying Critical Links and Evaluating the Performance of Transportation Networks. Journal of Transport Geography 2006, 14, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freckleton, D.; Heaslip, K.; Louisell, W.; Collura, J. Evaluation of Resiliency of Transportation Networks after Disasters. Transportation Research Record 2012, 2284, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krimmer, M. I-70 Corridor Risk & Resilience Pilot. 105.

- Hernandez, S.; Mitra, S. TRC2003 Data-Driven Methods to Assess Transportation System Resilience in Arkansas. 2020; p. 144. [Google Scholar]

- United States. Federal Highway Administration. Office of Highway Policy Information Traffic Data Computation Method: Pocket Guide. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L.; Boruff, B.J.; Shirley, W.L. Social Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards*. Social Science Quarterly 2003, 84, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, R.W. The Analytic Hierarchy Process—What It Is and How It Is Used. Mathematical Modelling 1987, 9, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, F. The Analytic Hierarchy Process—A Survey of the Method and Its Applications. Interfaces 1986, 16, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balubaid, M.; Alamoudi, R. Application of the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) to Multi-Criteria Analysis for Contractor Selection. AJIBM 2015, 05, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Using Decision Support Systems for Transportation Planning Efficiency; Ocalir-Akunal, E.V., Ed.; Advances in Civil and Industrial Engineering; IGI Global, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4666-8648-9. [Google Scholar]

- Abba, A.H.; Noor, Z.Z.; Yusuf, R.O.; Din, M.F.M.D.; Hassan, M.A.A. Assessing Environmental Impacts of Municipal Solid Waste of Johor by Analytical Hierarchy Process. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2013, 73, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, S.; Errore, A.; Lombardo, A. Prioritisation of Alternatives with Analytical Hierarchy Process plus Response Latency and Web Surveys. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/14783363.2014.904565?needAccess=true&role=button (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Saaty, T.L.; Özdemir, M.S. How Many Judges Should There Be in a Group ? Ann. Data. Sci. 2014, 1, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompf, K.; Traverso, M.; Hetterich, J. Using Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) to Introduce Weights to Social Life Cycle Assessment of Mobility Services. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecchia, L.; Bath, P.A.; Pendleton, N.; Bracale, M. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) for Examining Healthcare Professionals’ Assessments of Risk Factors: The Relative Importance of Risk Factors for Falls in Community-Dwelling Older People. Methods Inf Med 2011, 50, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.K.W.; Li, H. Application of the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) in Multi-Criteria Analysis of the Selection of Intelligent Building Systems. Building and Environment 2008, 43, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banai, R. Public Transportation Decision-Making: A Case Analysis of the Memphis Light Rail Corridor and Route Selection with Analytic Hierarchy Process. JPT 2006, 9, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedley, W.C. Consistency Prediction for Incomplete AHP Matrices. Mathematical and Computer Modelling 1993, 17, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donegan, H.A.; Dodd, F.J. A Note on Saaty’s Random Indexes. Mathematical and Computer Modelling 1991, 15, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, P. Ahpy: A Python Implementation of the Analytic Hierarchy Process.

- Forman, E. Aggregating Individual Judgments and Priorities with the Analytic Hierarchy Process. 1998, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, D.K.; de, S.; Marins, F.A.S.; Salomon, V.A.P.; Mello, C.H.P. On the Aggregation of Individual Priorities in Incomplete Hierarchies. 23 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T. The Analytic Hierarchy Process" Mcgraw-Hill. 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Aragón, T.J. Deriving Criteria Weights for Health Decision Making: A Brief Tutorial. 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Criteria | Definition | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Annual Average Daily Traffic (AADT) |

Daily traffic volume for each roadway link. | Link |

| Roadway Classification | Functional class of roadway link: Interstate, Freeways & Expressways, Principal Arterials, Minor Arterials, and Major Collectors. |

Link |

| Freight | Freight value in Millions of US dollars by county for the year. |

County |

| Tourism | Tourism value as expressed as Total County Expenditures in Millions of US dollars by county. |

County |

| Social Vulnerability Index (SoVI) | SoVI measures the social vulnerability of US counties to environmental hazards. It is an indicator comprised of 29 socioeconomic variables that contribute to a county’s ability to prepare for, respond to, and recover from hazards | County |

| Redundancy | The amount of additional travel time added to the network when a link is non-operational. | Link |

| Scale | Judgment of preference | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equally important | Two factors contribute equally to the objective |

| 3 | Moderately important | Experience and judgment slightly favor one over the other |

| 5 | Strongly important | Experience and judgment strongly favor one over the other |

| 7 | Very strongly important | Experience and judgment very strongly favor one over the other, as demonstrated in practice |

| 9 | Extremely important | The evidence favoring one over the other is of the highest possible validity |

| 2,4,6,8 | Intermediate preferences between adjacent scales |

When compromise is needed |

| Criticality Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | 1 Very Low Impact |

2 Low Impact |

3 Moderate Impact |

4 High Impact |

5 Very High Impact |

Weight |

| Annual Average Daily Traffic (AADT) |

<=720 | 721-1900 | 1901-4600 | 4601-15000 | >15000 | 0.240 |

| Redundancy | <=200 | 201-788 | 789-1870 | 1871-7500 | >12250 | 0.218 |

| Freight | <=800 | 801-2085 | 2086-3898 | 3899-12250 | >12250 | 0.186 |

| Roadway Classification | Major Collector |

Minor Arterial |

Principal Arterial |

Freeway Arterial |

Interstate | 0.144 |

| Social Vulnerability Index (SoVI) | -4.49-2.93 | -2.92-1.24 | -1.23-0.67 | -0.68-2.51 | 2.52-5.40 | 0.134 |

| Tourism | <=85 | 86-270 | 271-567 | 568-928 | >928 | 0.078 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).