Submitted:

01 May 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Conceptual Framework

Aim and Objectives

- Describe demographics of TB patients on TB treatment

- Determine the prevalence of non-adherents of TB treatment

- Identify determinants contributing to non-adherents of TB treatments

- Associate demographic characteristics of non-adherents and determinants of non-adherence to ATT.

- Desribe patient program and drug-related factor that affect non-adherence to ATT.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Setting

Study Population

Inclusion criteria:

- The study focused on adults who were at least 18 years and older.

- Individuals who had been diagnosed with tuberculosis and initiated on TB treatment

- Participants who voluntarily agreed to participate in study

Exclusion Criteria:

- Participants with other active infections, such as MDR TB or XDR TB.

- Participants with severe cognitive impairments affecting their understanding.

Sample Size Calculation and Sampling Strategy

Sampling Strategy

Data Collection Process

Data Collection Tool

Variables

Data Management

Data Protection

Data Analysis

Variables of Interest

Ethical Considerations

Results

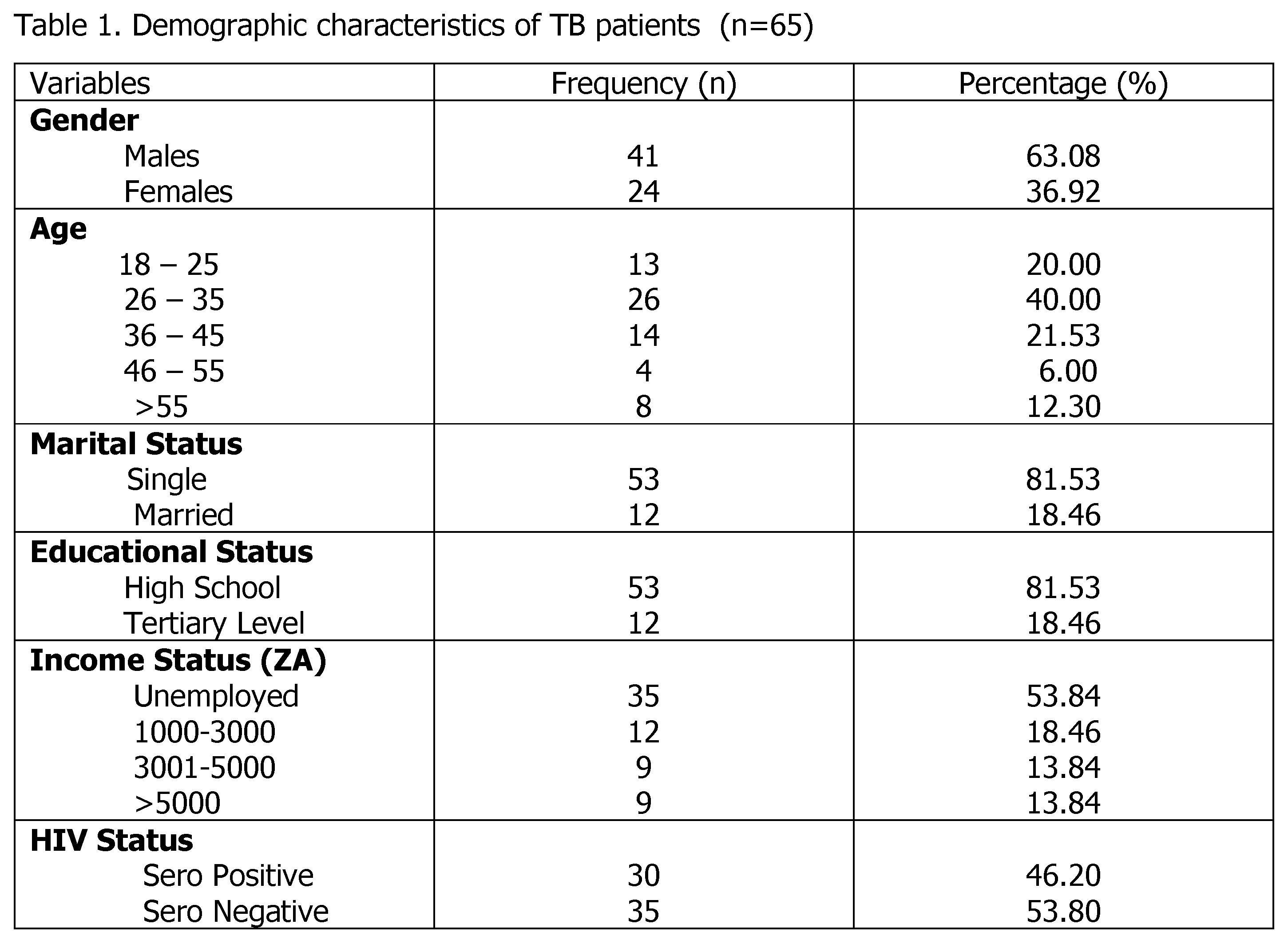

Demographic Characteristics

Demographics of Patients and Adherence Status

2.3.Sociodemographic Characteristics and Their Association with Treatment Adherents

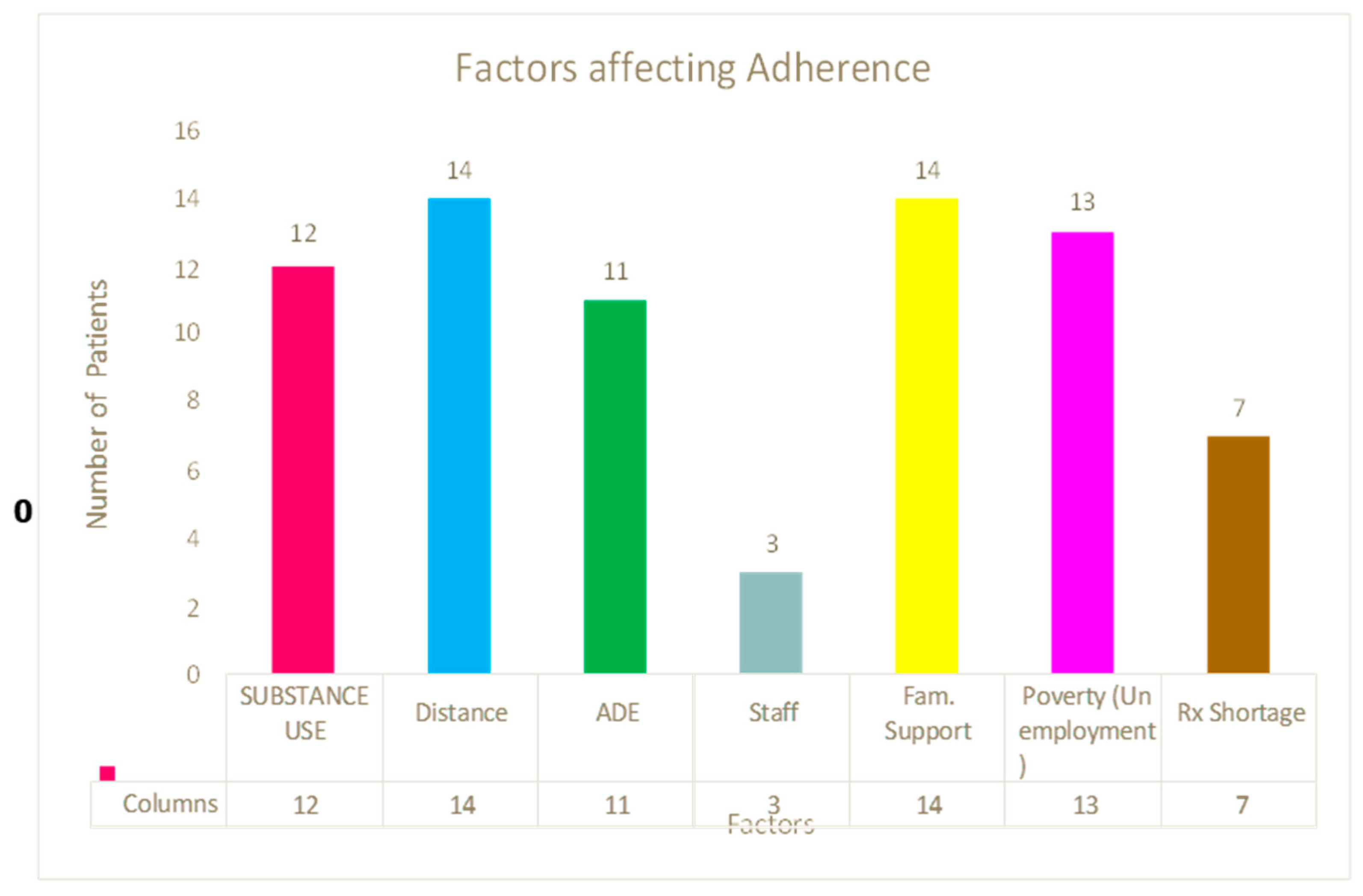

2.3. Factors influencing TB patients’ noncompliance with therapy.

Discussion

Key Findings

Discussion of Key Findings

Strengths and Limitations

Limitations of This Study

Implications and Recommendations

Implications

Recommendations

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Competing interest

Disclaimer

References

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis, Key facts. WHO 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis. Accessed on 6 Jan 2025.

- World Health organization. TB Overview. WHO 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis. Accessed on 1 Feb 2025.

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis. WHO 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis. Accessed on 7 June 2025.

- World Health organization. Global Tuberculosis Report, Tuberculosis. WHO 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/tuberculosis#tab=tab_1. Accessed on 2 Feb 2025.

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis resurges as top infectious disease killer. WHO 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-10-2024-tuberculosis-resurges-as-top-infectious-disease-killer. Accessed on 5 Feb 2025.

- Barter, D.M.; Agboola, S.O.; Murray, M.B.; Bärnighausen, T. Tuberculosis and poverty: the contribution of patient costs in sub-Saharan Africa – a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2012, 14, 12:980. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/980doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-980. Accessed on 11 Jan 2025.

- Boru, C.G.; Shimels, T.; Arebu, I.; Bilal, C. Factors contributing to non-adherence with treatment among TB patients in Sodo Woreda, Gura.ge Zone, Southern Ethiopia: A qualitative study. J. of Infect. Pub. Health 2017, 10, 527-533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2016.11.018. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876034117300333. Accessed on 5 Apr 2025.

- World Health Organization. WHO calls for urgent action to address worldwide disruptions in tuberculosis services putting millions of lives at risk. WHO, 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/20-03-2025. Accessed on 5 March 2025.

- Mkhavele, B.; Zondi, S.; Cele, L.; Mogale, M.; Mbelle, M. Factors associated with successful treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients in a district municipality of Vhembe, Limpopo. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2025, 67, a6030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Tuberculosis report of 2024. TB Incidence. WHO 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/. Accessed on 25 Jan 2025.

- Floyd, K.; Glaziou, P.; Houben, R.; M.; G.; J.; Sumner, T.; White, R.; Raviglion, M. Global tuberculosis targets and milestones set for 2016–2035: definition and rationale. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018, 1;22(7):723–730. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.17.0835. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.

- Houben, R.; M.; Dodd, P.; J. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: a re-estimation using mathematical modelling. Sustainable Development Goals [website]. New York: United Nations 2024. https://sdgs.un.org.

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages. New York: United Nations 2024. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health. Accessed on 8 June 2024.

- Kastien-Hilka, T.; Rosenkranz, B.; Schwenkglenks, M.; Bennett, B.M.; Sinanovic, E. Association between health-related quality of life and medication adherence in pulmonary tuberculosis in South Africa. Frontiers in pharmacology 2017, 8, p.919.

- WHO. What is DOTS? A guide to understanding the WHO recommended TB control strategy known as DOTS. WHO 1999. WHO/CDS/CPC/TB/99.270.

- Yin, J.; Yuan, J.; Hu, Y.; Wei, X. Association between Directly Observed Therapy and Treatment Outcomes in Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 3: e0150511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150511. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0150511. PMID: 26930287. Accessed on Dec. 2024.

- Collins, D.; Njuguna, C. The economic cost of non-adherence to TB medicines resulting from stock-outs and loss to follow-up in Kenya. In: Submitted to the US Agency for International Development by the Systems for Improved Access to pharmaceuticals and services (SIAPS) program. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health; 2016.

- SIAPS, U. Economic cost of Nonadherence to TB medicines resulting from stock-outs and loss to follow-up in the Philippines (Report) [Internet]. 2016. Available from: https://siapsprogram.org/publication/the-economic-cost-of-non-adherence-to-tb-medicines-resulting-from-stock-outs-and-loss-to-follow-upin-the-philippines/. Accessed on 10 Apr 2025.

- Grange, J.M.; Gandy, M.; Farmer, P.; Zumla, A. Historical declines in tuberculosis: nature, nurture and the biosocial model. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001, 5, 208–12. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11326817. Accessed on 7 Feb 2025.

- Styblo K, Meijer J, Sutherland I. [The transmission of tubercle bacilli: its trend in a human population]. Bull World Health Organ. 1969, 41, 137–78. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5309081. Accessed on 5 Jan 2025.

- Ndjeka, N. O.; Matji, R.; Ogunbanjo, G.A. An approach to the diagnosis, treatment and referral of tuberculosis patients: The family practitioner’s role. SA Fam Pract. 2008, 50, 44-50.

- World Health Organisation. Tuberculosis. TB and HIV. WHO, 2025. Available from:https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis. Accessed in Feb 2025.0.

- Obermeyer, Z.; Abbott-Klafter, J.; Murray, C.; J. Has the DOTS strategy improved case finding or treatment success? An empirical assessment. PLoS One 2008, 3, e1721. 000. 0001721 PMID: 18320042.

- World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. WHO 2003. [Internet] [cited Dec 26]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42682.

- Moodley, N.; Saimen, A.; Zakhura, N.; Motau, D.; Setswe, G.; Charalambous, S.; Chetty-Makkan, C.M. They are inconveniencing us’-exploring how gaps in patient education and patient centered approaches interfere with TB treatment adherence: perspectives from patients and clinicians in the Free State Province, South Africa. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goosby, E.; Jamison, D.; Swaminathan, S.; Reid, M.; Zuccala, E. The Lancet Commission on tuberculosis: building a tuberculosis-free world. The Lancet 2018, 391, 1132–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebremariam, R.B.; Wolde, M.; Beyene, A. Determinants of adherence to anti-TB treatment and associated factors among adult TB patients in Gondar city administration, Northwest, Ethiopia: based on health belief model perspective. J. Health, Population and Nutrition 2021, 40:49. [CrossRef]

- Anyaike, C.; Musa, O.I.; Babatunde, O.; Bolarinwa, O.; Durowade, K.A.; Ajayi, O.S. Adherence to tuberculosis therapy in Unilorin teaching hospital, Ilorin, north-central Nigeria. Int. J. Sci. Technol, 2013, 2, 2278–3687.

- Cramm, J.M.; Finkenflügel, H.J.; Møller, V.; and Nieboer, A.P. TB treatment initiation and adherence in a South African community influenced more by perceptions than by knowledge of tuberculosis. BMC public health 2010, 10, pp.1-8.

- Slovin, E. Slovin’s Formula for Sampling Technique. 1960. https://prudencexd.weebly.com/.

- Diedrich, C.R.; Flynn, J.L. HIV-1/mycobacterium tuberculosis coinfection immunology: how does HIV-1 exacerbate tuberculosis? Infection and immunity, 2011, 79, 1407-1417.

- Woimo, T.T.; Yimer, W.K.; Bati, T.; Gesesew, H.A. The prevalence and factors associated for anti-tuberculosis treatment non-adherence among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in public health care facilities in South Ethiopia: across-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 269. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-017-4188-9.

- Tesfahuneygn, G.; Medhin, G.; Legesse, M. Adherence to Anti-tuberculosis treatment and treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients in Alamata District, northeast Ethiopia. BMC. Res. Notes 2015, 8, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebede, A.; Wabe, N.; T. Medication adherence and its determinants among patients on concomitant tuberculosis and antiretroviral therapy in Southwest Ethiopia. N Am J Med Sci. 2012, 4, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sackett, L.D.; Haynes, R.B.; Gordon, H.G.; Tugwell, P. Clinical Epidemiology. A basic science for clinical medicine. Textbook of Clinical Epidemiology London. 2nd ed. London: Little, Brown and Company; 1991.

- Adams, S.A.; Soumeraj, B.S.; Jonathan, L.; Doss-Degan, D. Evidence of self report bias in assessing adherence to guidelines. Intern. J. for. Qual. In. Health Care 1999, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairley, C.K.; Permana, A.; Read, T.R.H. Long term utility of measuring adherence by self-report compared with pharmacy record in a routine clinic setting. HIV Medicine 2005, 6:366369.

- World Health Organisation. Global TB report. TB incidence. WHO, 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on- tuberculosis-and-lung-health/. Accessed on 15 Dec 2024.

- Naidoo, P.; Peltzer, K.; Louw, J.; Matseke, G.; Mchunu, G.; Tutshana, B. Predictors of tuberculosis (TB) and antiretroviral (ARV) medication non-adherence in public primary care patients in South Africa: a cross-sectional study Pamela. BMC Public Health 2013, 13:396. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/396.

- Arentz, M.; Pavlinac, P.; Kimerling, M.E.; Horne, D.J.; Falzon, D.; Schünemann, H.; J. et al. Use of Anti-Retroviral Therapy in Tuberculosis Patients on Second-Line Anti-TB Regimens: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47370. ttps://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047370.

- World Health Organisation. Tuberculosis: Multidrug-resistant (MDR-TB) or rifampicin-resistant TB (RR-TB). WHO 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/tuberculosis-multidrug-resistant-tuberculosis. Accessed on Mar 2025.

- Rieder, H. L. Interventions for tuberculosis control and elimination: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Paris; International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2002.

- Wohlleben, J.; Makhmudova, M.; Saidova, F.; Azamova, S.; Mergenthaler, C.; Verver, S. Risk factors associated with loss to follow-up from tuberculosis treatment in Tajikistan: a case-control study. BMC infectious diseases 2017, 17, pp.1-8.

|

Sociodemographic variables |

Treatment Adherents | Pearson chi-Square Tests | ||

| Adherents n % | Non-Adherents n % | X2 | P Value | |

|

Gender n % Male 41 (63.08) Female 24 (36.92) |

30 (66.70) 15 (33.30) |

11 (55.00) 9 (45.00) |

65 | <.001 |

|

Age range 18-25 13(20.00) 26-35 26(40.00) 36-45 14(21.53) 46-55 4(6.15) >55 8(12.30) |

10 (22.20) 16 (35.60) 10 (22.20) 4 (8.90) 5(11.10) |

3 (15.00) 10 (50.00) 4 (20.00) 0 (0.00) 3 (15.00) |

3.394 | 0.494 |

|

Marital Status Single 53(81.54) Married 12(18.46) |

38 (84.40) 7 (15.60) |

15 (75.00) 5 (25.00) |

0.142 | 0.706 |

|

Educational Status High School 53(81.54) Tertiary Level 12(18.54) |

40 (75.47) 5 (45.10) |

13 (24.53) 7 (35.00) |

0.142 | 0.706 |

|

Income Status Unemployed 35(53.84) 1000-3000 12(18.46) 3001-5000 9(13.84) >5000 9(13.84) |

22 (48.90) 6 (13.30) 9 (20.00) 8 (17.80) |

13 (65.00) 6 (30.00) 0 (0.00) 1 (5.00) |

4.035 | 0.258 |

|

HIV Status Sero Positive 30(46.20) Sero Negative 35(53.80) |

19(42.20) 26(57.80) |

11 (55.00) 9 (45.00) |

0.002 | 0.968 |

| Factors affecting the patients | Prevalence (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Substance use | 11 | 55 |

| Distance to the clinic | 14 | 70 |

| Adverse effects of the treatment | 11 | 55 |

| Poor interaction with the staff at the clinic | 3 | 15 |

| Lack of family support | 14 | 70 |

| Unemployment/Poverty | 13 | 65 |

| Shortage of drugs at the clinic | 7 | 35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).