Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

22 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Conceptual Framework Correlates and Interventions

- According to Baryakova et al. (2023) [34], patient-related variables include perceptions of obstacles such as cost, side effects, or absence of symptoms, as well as patient views, attitudes, knowledge, and comprehension of their disease and therapy.

- Treatment-related factors: according to Krousel-Wood et al. (2021) [35], they include the perceived side effects, the number of drugs, and the complexity of the

- treatment plan.

- Healthcare system factors: they include the patient’s experience with the healthcare system, the quality of communication between the patient and provider, and the availability of resources and support, according to Gast et al. (2019) [21].

- Social and environmental factors include factors like social support, access to resources, and cultural beliefs.

1.2. Examples of Conceptual Frameworks

1.1.2. Connection Between the Two Theories

1.2. Aim and Objectives

- Describe demographics of patients attending the clinic,

- Determine the prevalence of nonadherent to treatment,

- Identify demographic characteristics associated with nonadherence to treatment,

- Assess Healthcare System elements linked to treatment non-adherence.

- Establish Patient-related elements linked to treatment non-adherence

- Ascertain Socio-economic elements linked to treatment non-adherence

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Area, Period

2.1.1. Selection of the Research and Study Design

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Study Site

2.4. Study Population, Inclusion, and Exclusion Criteria

- Adult patients (18 years of age or older) who take medicine from the clinic for any disease and attend the public primary healthcare system were eligible to participate in the research.

- Both males and females

- Participants who are open to taking part in the research

- All races

- Individuals who declined to take part in the research

- Individuals who were too seriously unwell to answer the interview questions

- Those who did not have a caretaker were also eliminated from the research

2.5. Sample Size Determination and Sampling Technique

2.5.1. Sample Size and Calculation

- n = sample size, N = proportion of population size = 526, e = margin of error (<10%)

- n = N/(1 + Ne^2)

- n = 526 / (1 + 526(0.09^2)

- n = 99.98 = 100

2.5.2. Data Sampling Strategy

Study Variables

2.6. Data Collection

2.6.1. Data Collection Tool and Data Collectors

2.6.2. Data Collection Techniques

2.7. Data Handling and Analysis

Data Reporting

2.8. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants

3.2. Patient Related Factors to Non-Adherence

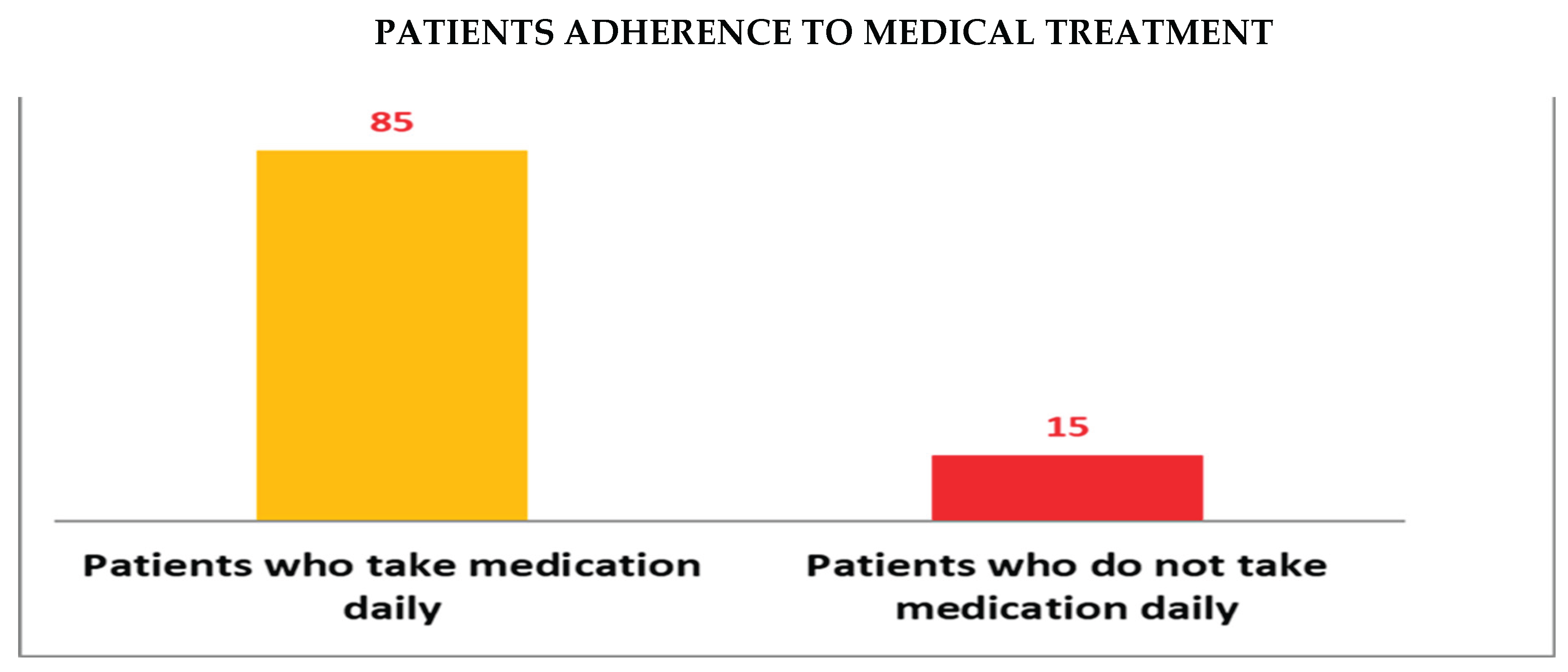

3.2.1. Patient Adherence to Treatment

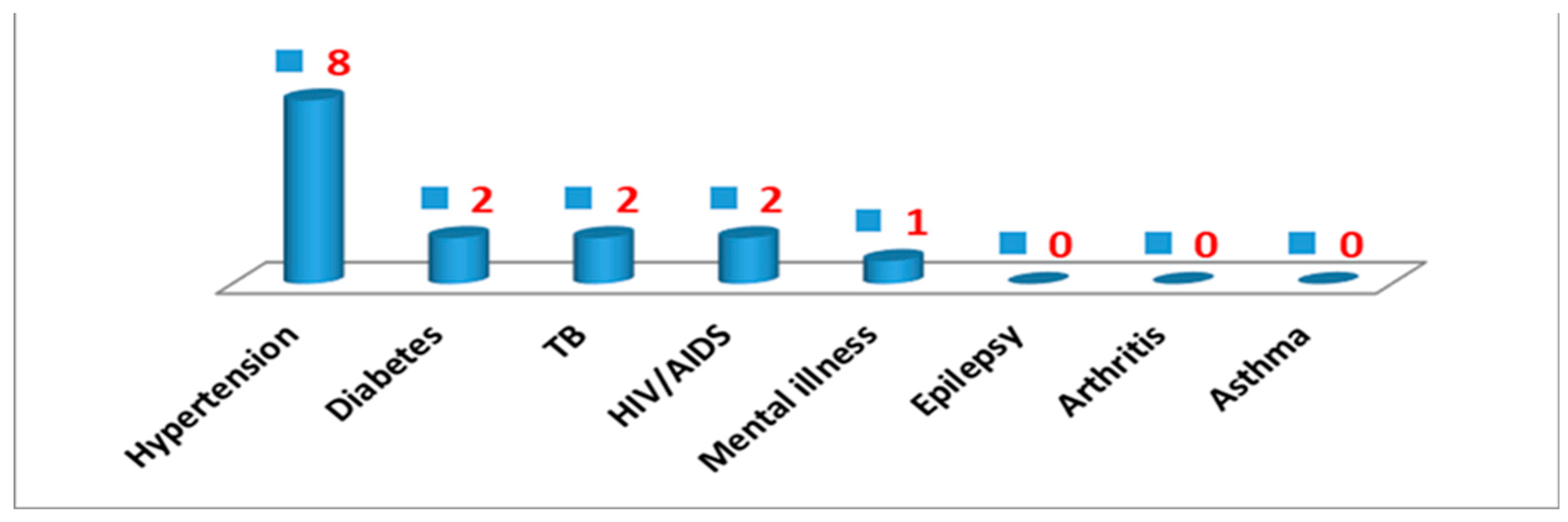

3.3. Patients’ Non-Adherence with Treatment per Illness

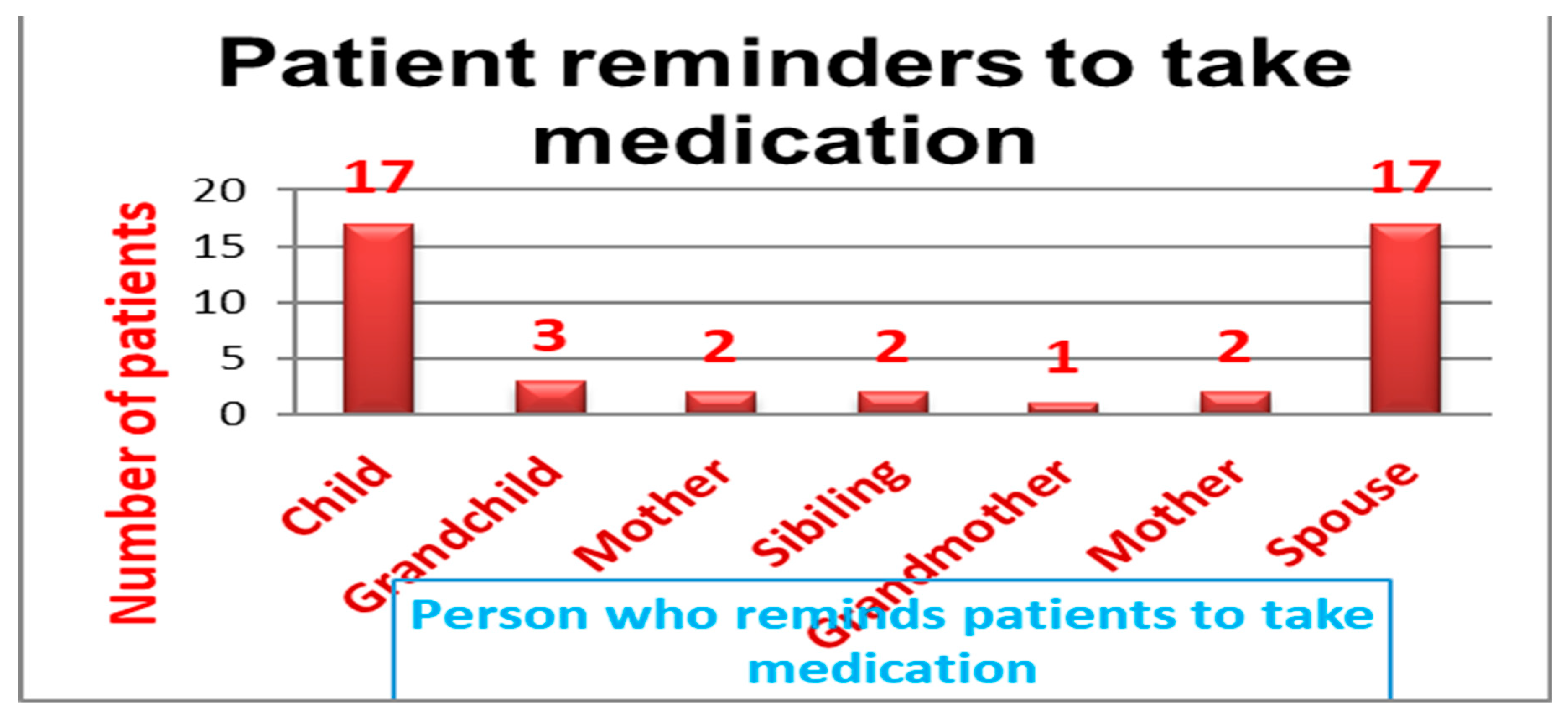

3.4. Person to Remind the Patients to Take Their Treatment.

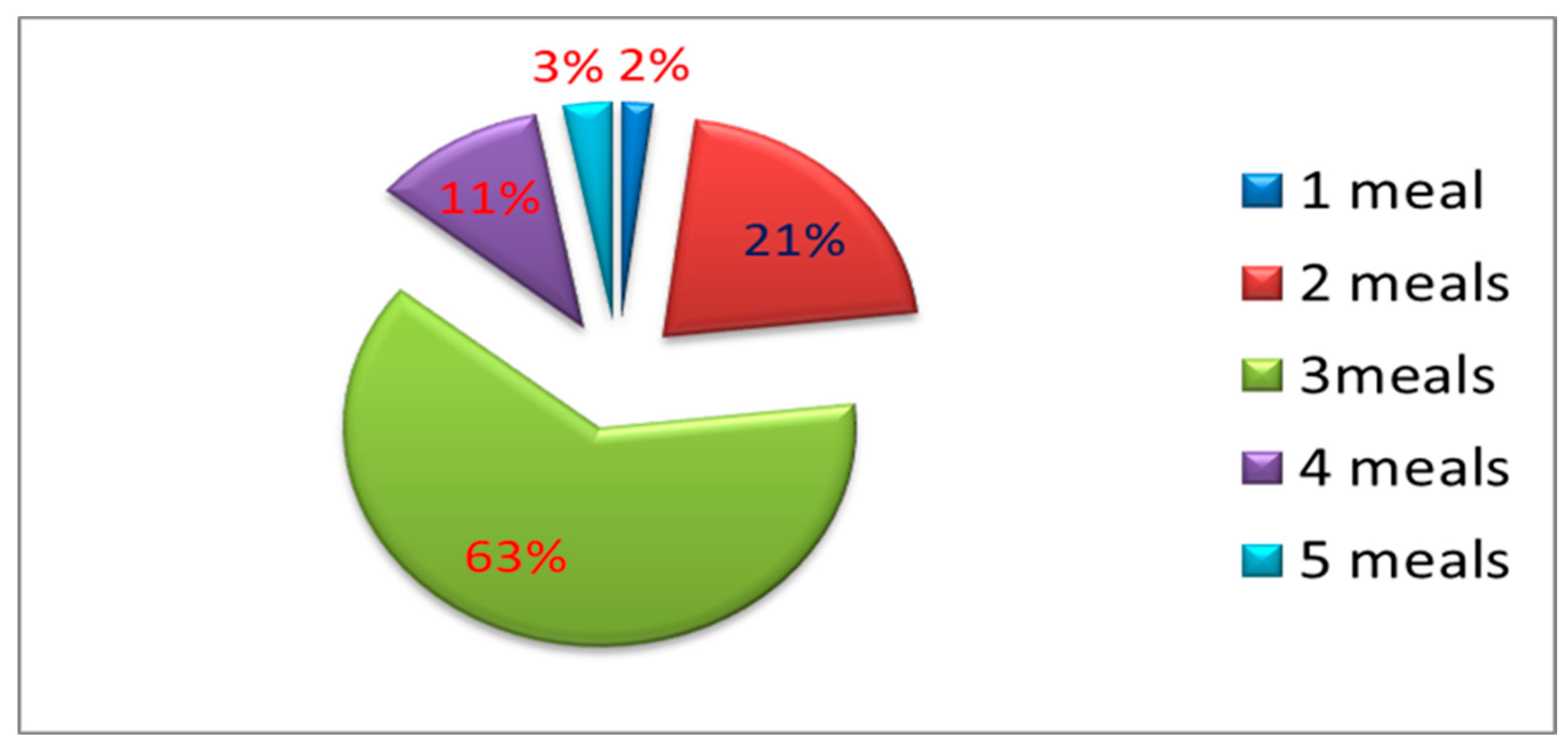

3.5. Number of Meals Taken per Day

3.6. Factors Linked to Treatment Non-Adherence.

3.6.1. Demographic Characteristics Associated with Nonadherence to Treatment

3.6.2. Factors Related to Treatment Non-Adherence in the Healthcare System

3.6.3. Patient-Related Factors Associated with Nonadherence to Treatment

|

Variable Categories |

Non-Compliance |

X2 |

p value |

| Yes No Total | |||

| Time it takes for patients to go to the clinic 0–15mins 16–30mins 31–45mins 46–60mins Total |

4 27 31 2 36 38 4 5 9 5 17 22 15 85 100 |

10.083 | 0.018 |

| Patients with Chronic Conditions Hypertension Diabetes Mellitis Arthritis Tuberculosis HIV/AIDS Epilepsy Asthma Mental Illness Total |

5 22 27 0 25 25 0 10 10 0 10 10 0 10 10 3 6 9 6 2 8 1 0 1 15 85 100 |

40.595 | <0.001 |

| Patients with reminders to take their treatment Yes No Total |

15 39 54 0 46 46 15 85 100 |

15.033 |

< 0.001 |

| Who reminds patients to take their treatment Child Grand Child Mother Sibling Grandmother Spouse Total |

2 15 17 3 0 3 1 3 4 2 0 2 0 1 1 5 12 17 13 31 44 |

14.964 | 0.011 |

3.6.4. Socio-Economic Factors Associated with Nonadherence to Treatment

4. Discussion of Results

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Discussion of Key Findings

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.3.1. Strengths

4.3.2. Limitations

4.4. Implications and Recommendations

4.4.1. Implications

4.4.2. Recommendations for This Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pourhabibi, N.; Mohebbi, B.; Sadeghi, R.; Shakibazadeh, E.; Sanjari, M.; Tol.; Yaseri, M. Determinants of Poor Treatment Adherence among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Limited Health Literacy: A Scoping Review. Diabetes Res. 2022, 4:2980250. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.F.; Moon, Z.; Horne R. Medication nonadherence: health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychology & health 2023, 38, 726–765. [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.R.; Williams, S.M.; Haskard, K.B.; DiMatteo, M.R. The challenge of patient adherence. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 2005, 1, 189–199. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18360559.

- Al-Worafi, Y.M. (2024). Quality of Healthcare Systems in Developing Countries: Status and Future Recommendations. In: Al-Worafi, Y.M. (eds) Handbook of Medical and Health Sciences in Developing Countries, 2024. Springer, Cham. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Burch, L.S.; Smith, C.J.; Anderson, J.; Sherr, L.; Rodger, A.J.; a, Rebecca O'Connell, R. et al. Socioeconomic status and treatment outcomes for individuals with HIV on antiretroviral treatment in the UK: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Lancet Public Health 2016, 1, e26–e36. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.A.; Cahir, C.; Tecklenborg, S.; Byrne, C.; Culbertson, M.A.; Bennett, K.E. The association between medication non-adherence and adverse health outcomes in ageing populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019, 85, 2464–78. [CrossRef]

- Iuga, A.O.; McGuire, M.J. Adherence and health care costs. Risk Manag Healthcare Policy 2014, 7, 35–44. [CrossRef]

- Cutler, R.L.; Fernandez-Llimos, F.; Frommer, M.; Benrimoj, C.; Garcia-Cardenas, V. economic impact of medication non-adherence by disease groups: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e016982. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.J.; José, H.M.G.; Teixiera da Costa, E.I.M. Medication adherence in adults with chronic diseases in primary healthcare: a quality improvement project. Nurs Rep. 2024,14, 1735–49. [CrossRef]

- Sabaté, E. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action World Health Organization, 2003. Available at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42682.

- Bronkhorst, E.; Schellack, N,; Gous, A.G.S.; Pretorius, J.P. The need for pharmaceutical care in an intensive care unit at a teaching hospital in South Africa. South. Afr. j. crit. care (Online 2014, 2. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Failure to take prescribed medicine for chronic diseases is a massive, world-wide problem. Patients fail to receive needed support. WHO, 2003. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-07-2003-failure-to-take-prescribed-medicine-for-chronic-diseases-is-a-massive-world-wide-problem.

- Simpson, S. H., eurich, D. T., Majumdar, S. R., Padwal, R. S., Tsuyuki, R. T., Varney, J., Johnson, J. A. (2006). A meta-analysis of the association between adherence to drug therapy and mortality. BMJ, 333, (7557), 15. [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Joining Forces to leave No One Behind. OECD Report 2018. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/development-co-operation-report-2018_ / https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/exploring-the-relationship-between-non-communicable-diseases-and-depression_02a1cfc5-en.html.

- Khan, R., Socha-Dietrich, K. Investing in medication adherence improves health outcomes and health system efficiency: Adherence to medicines for diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. OECD Health Working Papers No. 105. 2025. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. World Health Organization. Published 2003. Accessed October 8, 2023. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42682.

- Konstantinou, P.; Kassianos A.P.; Georgiou G, et al. Barriers, facilitators, and interventions for medication adherence across chronic conditions with the highest non-adherence rates: A scoping review with recommendations for intervention development. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10(6):1390-1398. [CrossRef]

- Kvarnström, K.; Airaksinen, M.; Liira. H. Barriers and facilitators to medication adherence: A qualitative study with general practitioners. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e015332. [CrossRef]

- Simon, S.T.; Kini, V.; Levy, A.E.; Ho PM. Medication adherence in cardiovascular medicine. BMJ, 2021, 374, 1493. [CrossRef]

- Gast, A.; Mathes, T. Medication adherence influencing factors - An (updated) overview of systematic reviews. Syst Rev, 2019, 1, 112. [CrossRef]

- Kvarnström, K.; Westerholm, A.; Airaksinen, M.; Liira, H. Factors contributing to medication adherence in patients with a chronic condition: A scoping review of qualitative research. Pharmaceutics. 2021, 7,1100. [CrossRef]

- Peh, K.Q.E.; Kwan, Y.H.;m Goh, H. et al. An Adaptable Framework for Factors Contributing to Medication Adherence: Results from a Systematic Review of 102 Conceptual Frameworks. J Gen Intern Med, 2021, 9, 2784-2795. [CrossRef]

- Kardas, P.; Lewek, P.; Matyjaszczyk, M. Determinants of patient adherence: A review of systematic reviews. Front Pharmacol. 2013, 4,91. [CrossRef]

- Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(11):CD000011. [CrossRef]

- Harsha N, Papp M, Kőrösi L, Czifra Á, Ádány R, Sándor J. Enhancing primary adherence to prescribed medications through an organized health status assessment-based extension of primary healthcare services. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(20):3797. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Thompson J, Dong H, et al. Digital adherence technologies to improve tuberculosis treatment outcomes in China: a cluster-randomised superiority trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11(5):e693-e703. [CrossRef]

- Price D, Robertson A, Bullen K, Rand C, Horne R, Staudinger H. Improved adherence with once-daily versus twice-daily dosing of mometasone furoate administered via a dry powder inhaler: A randomized open-label study. BMC Pulm Med. 2010;10:1. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton JE, Blanco E, Selek S, et al. Patient and Provider Perspectives on Medication Non-adherence Among Patients with Depression and/or Diabetes in Diverse Community Settings – A Qualitative Analysis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:1581-1594. [CrossRef]

- Bell S, Kelly H, Hennessy E, Bermingham M, O’Flynn JR, Sahm LJ. Healthcare professional perspectives on medication challenges in the post-stroke patient. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1266277. [CrossRef]

- Clyne W, Mshelia C, McLachlan S, et al. A multinational cross-sectional survey of the management of patient medication adherence by European healthcare professionals. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e009610. [CrossRef]

- Jimmy, B., Jose, J. Patient Medication Adherence: Measures in Daily Practice. Oman Med J. 2011 May;26(3):155–159. [CrossRef]

- Chia, Y.C. Understanding Patient Management: The Need for Medication Adherence and Persistence. Malays Fam Physician. 2008 Apr 30;3(1):2–6. http://www.ejournal.afpm.org.my/.

- Baryakova, T.H.; Brett H Pogostin, B.H.; Langer, R.; Kevin J McHugh, K.J. Overcoming barriers to patient adherence: the case for developing innovative drug delivery systems Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023, 27, 5, 387–409. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.F.; Zoe Moon, Z.; Horne, R. Medication nonadherence: health impact,.

- prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychology & health 2023, Vol. 38, No. 6, 726–765. [CrossRef]

- Krousel-Wood, M.; Craig, L.S.; Peacock, E.; Zlotnick, E.; O’Connell, S.; Bradford, D.; Shi, L.; Petty, R. Medication Adherence: Expanding the Conceptual Framework Am J hypertens, 2021, 9, 895–909. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8457429/#. [CrossRef]

- Moomba, K.; Van Wyk, B. Social and economic barriers to adherence among patients at Livingstone General Hospital in Zambia. Afr J Prm Health Care Fam Med. 2019, 1, a1740. Available from: https://phcfm.org/index.php/phcfm/article/view/1740/3034#. [CrossRef]

- Bolsewicz K, Debattista J, Vallely A, Whittaker A, Fitzgerald L. Factors associated with antiretroviral treatment uptake and adherence: A review. Perspectives from Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom. AIDS Care 2015, 27, 21, 1429–1438. [CrossRef]

- Ankomah A, Ganle JK, Lartey MY, et al. ART access-related barriers faced by HIV-positive persons linked to care in southern Ghana: A mixed method study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016, 16, 738. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-2075-0.

- Holmes, E.A.F.; DA Hughes, D.A.; Morrison, V.L. Predicting Adherence to Medications Using Health Psychology Theories: A Systematic Review of 20 Years of Empirical Research. Value in Health 2024, 8, 863-876. Available From: https://www.valueinhealthjournal.com/article/S1098-3015(14)04621-X/pdf#.

- Bauer, M.S., Damschroder, L., Hagedorn, H. et al. An introduction to implementation science for non-specialists. BMC Psychol 3, 32 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Bonolo, P.F.; Ceccato, M.G.; Rocha, G.M.; Acurcio, F.A.; Campo, L.N.; Guimaraes, M.D. Gender differences in non-adherence among Brazilian patients initiating antiretroviral therapy. Clinics 2013, 5, 612-620. [CrossRef]

- Ghidei, L.; Simone, M.; Salow, M.; Zimmerman, K.; Paquin, A.M.; 3,4, Skarf, L.M. Aging, Antiretrovirals, and Adherence: A Meta Analysis of Adherence among Older HIV-Infected Individuals. Drugs Aging 2013, 10, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Uchmanowicz, B.; Chudiak, A.; Uchmanowicz, I.; Rosińczuk, J.; Froelicher, E.S. Factors influencing adherence to treatment in older adults with hypertension. Clin Interv Aging 2018, 33, 2425. [CrossRef]

- Sweileh, W.; Aker, O.; Hamooz, S. Rate of compliance among patients with diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Natural Sci, 2004, 1, 1–11.

- Walsh, C.A.; Cahir, C.; Tecklenborg, S.; Byrne, C.; Culbertson, M.A.; Bennett, K.E. The association between medication non-adherence and adverse health outcomes in ageing populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2019, 6, 11, 2464–2478. [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.D.; Tsang, P.M.; Winson, T.L.; Harry, H.X. Wang, Kirin, Q.L. Liu, Sian M. Griffiths, Martin, C.S. Wong Kang, C.D. et al. Determinants of medication adherence and blood pressure control among hypertensive patients in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. Int J Cardiol. 2015, 182, 250–7. [CrossRef]

- Alinaitwe, B., Shariff, N.J. & Madhavi Boddupalli, B. Treatment adherence and its association with family support among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Jinja, Eastern Uganda. Sci Rep, 2025, 15, 11150. [CrossRef]

- Nhlongolwane, N.; Shonisani, T. Predictors and Barrier associated with Non-Adherence to ART by People Living with HIV and AIDS in a Selected Local Municipality of Limpopo Province, South Africa. The Open AIDS Journal, 2023, Volume 17. 2023, 17, e187461362306220. [CrossRef]

- Velloza, J.; Kemp, C.G.; Aunon, F.M.; Ramaiya, M.K.; Creegan, E.; Jane, M. Alcohol Use and Antiretroviral Therapy Non-Adherence Among Adults Living with HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AIDS Behav, 2020, 6, 727–1742. [CrossRef]

- Kalichman, S.C.; Pellowski, J.; Kalichman, M.O.; Cherry, C.; Detorio, M.; Caliendo, A.M.; Schinazi, R.F. Food Insufficiency and Medication Adherence Among People Living with HIV/AIDS in Urban and Peri-Urban Settings. Prev Sci, 2011, 3, 324–332. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (% ) |

|---|---|---|

|

Gender Male Female Total |

35 65 100 |

35.0 65.0 100.0 |

|

Age Range 18–39 40–59 60–80 >80 Total |

15 37 45 3 100 |

15.0 37.0 45.0 3.0 100.0 |

|

Distribution per Age Category Youth Middle Age Elderly Old Age Total |

14 43 38 3 100 |

21.5 66.2 58.5 4.6 100.0 |

|

Age distribution per Male Youth Middle Age Elderly Old Age Total |

8 11 14 2 35 |

22.9 31.4 40.0 5.7 100.0 |

|

Age distribution Female Youth Middle age Elderly Old Age Total |

7 26 31 1 65 |

10.8 40.0 47.7 1.5 100.0 |

|

Educational Level Illiterate Primary High School Tertiary Total |

28 30 40 2 100 |

28.0 30.0 40.0 2.0 100.0 |

| Distribution of educational level per gender | ||

|

Female Educational Level Illiterate Primary High School Tertiary Total |

17 21 26 1 65 |

10.8 40.0 47.7 1.5 100.0 |

|

Male Educational Level Illiterate Primary High School Tertiary Total |

11 9 12 3 35 |

31.4 25.7 34.3 8.6 100.0 |

|

Variable Categories |

Non-adherence | X2 p Value |

| Yes No Total | ||

|

Gender Female Male Total |

6 59 65 9 26 35 15 85 100 |

|

| 4.848 0.028 | ||

|

Age 16–39 40–59 60–80 >80 Total |

4 11 15 4 33 37 5 40 45 2 1 3 15 85 100 |

8.925 0.030 |

|

Educational level Illiterate Primary High School Tertiary Total |

6 22 28 5 25 30 4 36 40 0 2 2 15 85 100 |

2.110 0.550 |

|

Female Educational Level Illiterate Primary High School Tertiary Total |

15 2 17 0 21 21 0 26 26 0 2 2 15 51 66 |

55.952 <0.001 |

|

Male Educational Level Illiterate Primary High School Tertiary Total |

11 0 11 0 8 8 4 9 13 0 0 0 15 17 32 |

20.880 < 0.001 |

|

Variable Categories |

Non-adherence |

X2 |

p Value |

| Yes No Total | |||

| Waiting time to get treatment 0–30mins 31–60mins 91–120mins 121–180mins 181–210mins 200–240mins 241–300mins Total |

2 23 25 3 5 8 0 1 1 0 10 10 0 8 8 0 13 23 10 25 35 15 85 100 |

14.840 | 0.022 |

| Treatment by Healthcare Providers Acceptable Good Bad Total |

15 13 28 0 69 69 0 3 3 15 85 100 |

45.378 | <0.001 |

| Mode of Transport Taxi Walking Own Car Horse Total |

9 64 73 2 19 21 3 2 5 0 0 0 14 85 100 |

9.227 | 0.010 |

| Distance from home to the clinic >5 km <5Km Walking distance Total |

5 53 58 7 22 29 3 10 13 15 95 100 |

4.416 | 0.110 |

| Medicine Availability Not always available Always available Total |

7 32 39 8 53 61 15 85 100 |

0.436 | 0.509 |

|

Variable Categorical Values |

Non-compliance |

X 2 |

p value |

OR |

95% CI Lower Higher bounds |

| Yes No Total | |||||

| Alcohol consumption Yes No Total |

11 0 11 4 85 89 15 85 100 |

70.037 | <0.001 | 22.25 | 8.539 - 57.977 |

| Smoking Yes No Total |

0 5 5 15 80 95 15 85 100 |

0.929 | 0.333 | 1.188 | 1.088 - 1.296 |

| Recreational Drugs Yes No Total |

4 0 4 11 85 96 15 85 100 |

23.611 | <0.001 | 8.727 | 5.005 - 15.219 |

| Traditional Medicine Yes No Total |

1 22 23 14 63 77 15 85 100 |

2.658 | 0.103 | 0.205 | 0.025 - 1.647 |

| Meals taken per day One meal Two meals Three meals Four Meals Five meals Total |

2 0 2 3 18 21 6 57 63 4 7 11 0 3 3 15 85 100 |

17.291 | 0.002 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).