1. Introduction

Sustainable development in Indonesia’s nickel mining regions remains a complex challenge, marked by ongoing environmental degradation, socio-economic disruption, and governance fragmentation. While the mining sector drives national economic gains, its long-term consequences—ranging from ecological damage and displacement to rural disempowerment—demand a more systemic and future-oriented sustainability framework. Addressing these challenges requires a dual focus: reconfiguring institutional arrangements and fostering behavioral shifts that support post-mining recovery and the development of resilient, community-based livelihoods.

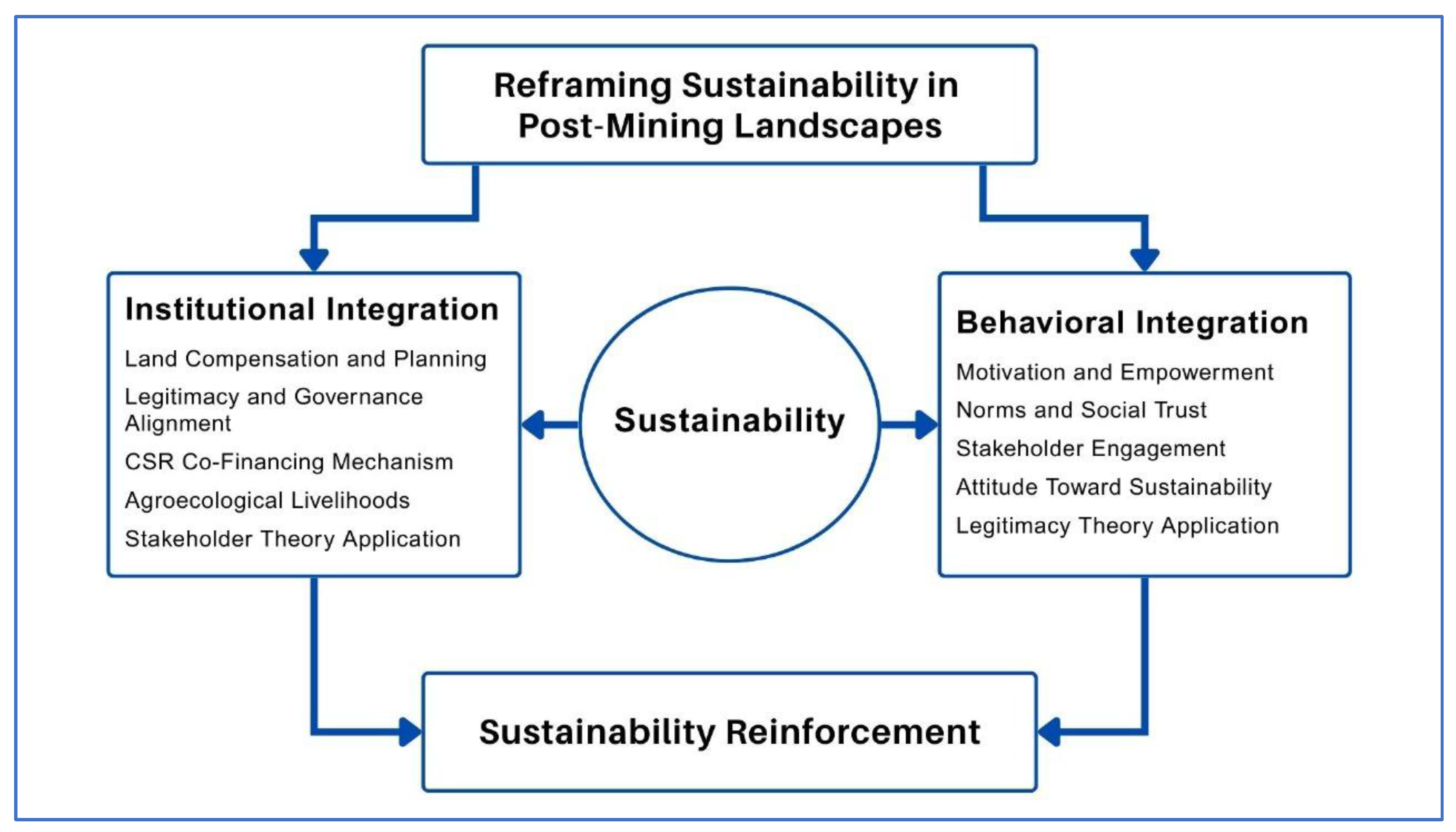

This article is intentionally designed to lay the conceptual groundwork for three subsequent sustainability models. It proposes a reframing of post-mining sustainability through the integrated lenses of institutional alignment and behavioral transformation. The resulting model—Reframing Sustainability in Post-Mining Landscapes: A Foundational Framework for Institutional and Behavioral Integration in Indonesia—establishes the theoretical base that informs and supports the development of: (1) A Community Development Model, grounded in cocoa-based agricultural transformation; (2) A Triple Bottom Line Performance Model, which evaluates CSR-driven metrics for sustainable outcomes; and (3) A Transformation-Readiness Model, which maps pathways for institutional adaptation and community mobilization.

These models are derived from a qualitative meta-synthesis of 1,339 coded remarks from academic and institutional literature, structured across ten parent themes and eighty sub-themes. Together, they form a unified research trajectory that advances sustainability theory and practice in Indonesia’s post-extractive landscapes.

This article aims to reorient the sustainability discourse in post-mining contexts by moving beyond fragmented, compliance-driven approaches toward a more integrated, participatory, and transformation-oriented strategy. Grounded in the combined insights of Stakeholder Theory [

1], Legitimacy Theory [

2], and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [

3], the proposed framework emphasizes the dual necessity of institutional alignment and behavioral readiness. These theoretical foundations collectively support the conceptual development and empirical validation of the four interlinked manuscripts. Together, they explain how sustainability in post-mining landscapes requires more than regulatory adherence or technical reclamation; it must engage deeply with the co-evolution of governance structures and community agency, enabling long-term institutional legitimacy, stakeholder engagement, and socially grounded transformation.

The theoretical framework developed here views sustainability as the product of intertwined institutional reform and behavioral transformation. Drawing upon the three core theories—Stakeholder, Legitimacy, and TPB—it contends that meaningful outcomes only arise when both top-down governance and bottom-up behavior align. This approach provides a strategic lens for analyzing how policies and community agency interact to generate resilience in rehabilitated mining areas.

The development of this framework is grounded in a comprehensive literature review spanning topics in sustainability science, governance, community empowerment, and agroecological transition. The review draws heavily from both global and Indonesian sources addressing issues such as environmental degradation [

4,

5], socio-economic instability [

6,

7], and fragmented CSR implementation [

8,

9]. These studies reveal a critical gap in models capable of integrating institutional and behavioral dimensions into a unified sustainability framework.

The institutional integration pathway focuses on the policy frameworks and structural conditions required for sustainable transitions. This includes aligning land compensation schemes with local needs [

10], building governance legitimacy through transparency and inclusive decision-making [

2,

11], and leveraging CSR funding to support community development [

12,

13]. Agroecological approaches—such as cocoa-based farming—are also emphasized for their dual role in land restoration and livelihood generation [

14,

15].

In parallel, the behavioral integration pathway addresses psychological and cultural drivers of sustainable practice. Informed by TPB, this includes fostering sustainable attitudes, strengthening social norms, building trust, encouraging stakeholder participation, and enhancing skills and motivation [

3,

16,

17]. The coded remarks consistently pointed to behavioral intention and community readiness as central to the uptake and long-term success of sustainability programs, reinforcing the framework’s focus on social inclusion and participatory governance.

The model derives its strength from the fusion of empirical insights with theoretical rigor, identifying key mechanisms for achieving sustainability in post-mining settings. In the institutional domain, themes like Land Compensation & Planning underscore the need for compensation schemes that align with community aspirations [

10,

18]. Governance legitimacy emerges as a central concern, with inconsistent or extractive systems weakening trust and accountability [

2,

7,

19]. CSR Co-Financing is reframed not as charity but as a mechanism for financing long-term public goods [

12,

13,

20]. Agroecological Livelihoods, particularly cocoa-based systems, are presented as transformative land-use models that restore soil and empower farmers [

14,

15,

16].

The behavioral dimension complements this by focusing on attitudes, trust, norms, and internal motivation. Attitude toward Sustainability reflects the degree to which sustainability principles are internalized [

3,

6,

21]. Norms & Social Trust examines how peer expectations and social cohesion influence compliance and innovation [

22,

23]. Stakeholder Engagement calls for deeper, inclusive participation where farmers and Indigenous groups are active co-creators, not passive recipients [

8,

9,

17] Finally, Motivation Empowerment captures the psychological readiness to transition from mining-based to sustainable livelihoods, emphasizing belief in one’s capacity to enact change [

16,

24]

In summary, achieving sustainability in Indonesia’s post-mining regions requires coordinated efforts on two fronts: institutional redesign and behavioral transformation. The model developed in this study demonstrates how legal frameworks, CSR co-financing, and agroecological planning must be aligned with cultural values, trust, and community empowerment [

12,

14,

18,

20]. The interplay of these forces shows that structural reforms and behavioral shifts are not sequential, but mutually reinforcing. This integrated approach represents a shift from extractive legacies toward regenerative, community-driven futures in post-mining landscapes.

The novelty of this study lies in its methodological and conceptual integration across multiple knowledge domains, using a qualitative meta-synthesis of 1,339 literature-based remarks to construct a unified, empirically grounded sustainability framework. While previous studies have often treated post-mining governance, environmental recovery, and social impact in isolation, this research uniquely combines institutional and behavioral dimensions into a single foundational model. Unlike conventional performance evaluations or CSR audits, this framework embeds stakeholder intention, trust, and empowerment alongside structural mechanisms such as CSR funding, legitimacy alignment, and agroecological planning. This dual-lens model not only advances theory through the triangulation of TPB, Legitimacy Theory, and Stakeholder Theory, but also offers a practical roadmap for sustainable transition in Indonesia’s mining regions—making it a critical departure from fragmented approaches toward a holistic and participatory sustainability architecture.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employs a theory-informed qualitative meta-synthesis to reframe a sustainability framework in Post-mining landscape in Indonesia. Drawing on 1339 literature-derived remarks, the methodology integrates multiple conceptual frameworks—CSR, Stakeholder Theory, Legitimacy Theory, TPB, and the Triple Bottom Line (TBL)—to guide both coding and model construction. A structured analytical process using NVivo software enabled thematic consistency across 10 parent nodes and 80 child codes, while the conceptual framework provided a bridge between institutional inputs, behavioral drivers, and sustainability outcomes. Together, these methods establish a rigorous foundation for synthesizing qualitative data into a practical, theory-driven model.

2.1. Research Design

This study employs a qualitative meta-synthesis methodology to reframe Sustainability in Post-Mining Landscapes, focusing on cacao-based agroforestry. Combining systematic literature review, thematic coding using NVivo 12, and theory-based model refinement, the methodology integrates CSR, TBL, Stakeholder Theory, TPB, and Legitimacy Theory. This explorative and interpretive approach allows diverse knowledge forms to be synthesized into a coherent analytical framework.

Data Sources and Selection Criteria. The primary dataset consists of 1,339 synthesized remarks drawn from 1,352 academic and institutional sources published between 1956 and 2025. Sources include peer-reviewed journals, dissertations, books, and official reports, accessed through platforms such as Scopus, Google Scholar, SpringerLink, and national repositories. Each remark represents a synthesized finding or recommendation from a single source. Remarks were collected between December 2022 and March 2025 and stored in a structured MS Access database. The database was relationally organized across four tables (Journal, Circulation, Article, DetailedStudy) and verified through paragraph count to ensure 1,339 unique entries. These remarks were then imported into NVivo for coding. In this study, the remarks become respondents. A two-level node structure was developed in NVivo: 10 parent nodes with 8 child nodes each, totaling 80 codes. Child node keywords were used in NVivo’s synonym-enabled search function to perform initial auto-coding. Manual corrections ensured accuracy between search reports and actual reference counts. Alternative phrasings were used when keywords returned zero hits. This refined coding process allowed comprehensive thematic coverage.

Conceptual Research Framework.

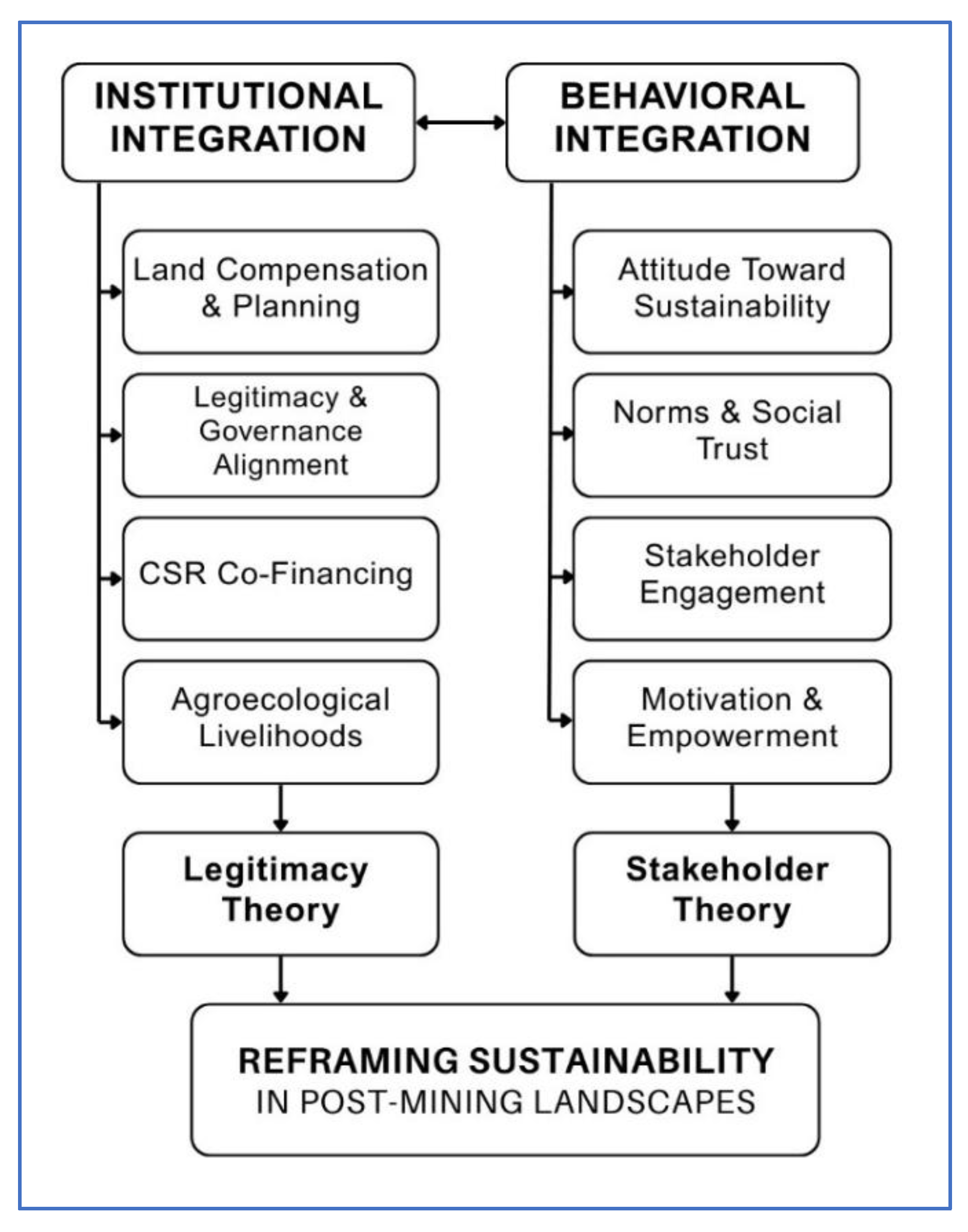

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of this study, which is built upon two primary integration pathways. On the left side, the Institutional Integration pathway comprises four elements: Land Compensation & Planning, Legitimacy & Governance Alignment, CSR Co-Financing and Agroecological Livelihoods, and Agroecological Livelihoods. This pathway is mediated by Legitimacy Theory, which emphasizes trust-building and accountability within post-mining governance structures.

On the right side, the Behavioral Integration pathway addresses psychosocial dimensions, including Attitude toward Sustainability, Norms & Social Trust, Stakeholder Engagement, and Motivation & Empowerment. This pathway is mediated by Stakeholder Theory, which underscores the importance of inclusive participation and the active agency of communities in shaping sustainable outcomes.

Both pathways converge in the central objective of Reframing Sustainability in Post-Mining Landscapes, the core transformation model proposed in this study. The diagram demonstrates that sustainability is not the product of a single approach but rather emerges from the synergistic interaction between institutional reform and social readiness.

The conceptual framework presented in the

Figure 1 delineates a dual-pathway integration model—institutional integration and behavioral integration—as a foundation for reframing sustainability in post-mining landscapes. On the institutional side, four key dimensions are highlighted: land compensation and planning, which addresses the need for equitable land redistribution and future land-use governance; legitimacy and governance alignment, which ensures regulatory compliance and social approval; CSR co-financing, which mobilizes corporate resources for public benefit; and agroecological livelihoods, which provide long-term economic alternatives for affected communities. On the behavioral side, sustainability is supported by factors such as attitude toward sustainability, norms and social trust, stakeholder engagement, and motivation and empowerment—all critical components that shape community readiness and participatory action.

These two integration pathways are theoretically grounded in Stakeholder Theory and Legitimacy Theory, both of which justify the need for inclusive governance and public accountability in resource-based industries. Together, they converge into a unified model titled “Reframing Sustainability in Post-Mining Landscapes: A Foundational Framework for Institutional and Behavioral Integration in Indonesia.” This framework positions sustainability not merely as an environmental goal but as an integrated socio-institutional transformation process essential to equitable post-mining development.

The determination of the ten parent nodes in this study is grounded in the systematic analysis of 1,339 coded remarks sourced from academic literature and institutional documents. These nodes were not arbitrarily selected but emerged through a qualitative meta-synthesis process using NVivo, guided by thematic convergence, theoretical relevance, and practical resonance in the context of post-mining sustainability. Four institutional integration themes—land compensation and planning, legitimacy and governance alignment, CSR co-financing mechanisms, and agroecological livelihoods—were distilled from patterns in the literature emphasizing the structural and policy-level interventions necessary for sustainable transitions [

4,

5,

25]). These dimensions reflect how institutional arrangements shape the long-term viability of land reclamation and community empowerment.

On the behavioral side, four nodes—attitude toward sustainability, norms and social trust, stakeholder engagement, and motivation and empowerment—align with theoretical constructs drawn from the Theory of Planned Behavior and reflect the behavioral readiness of local communities to participate in transformation processes [

3,

26,

27]. These nodes were substantiated by repeated references in the remarks dataset indicating the influence of trust, cultural attitudes, and social norms on sustainability outcomes.

To ensure analytical rigor and theoretical grounding, the final two parent nodes—Legitimacy Theory Application and Stakeholder Theory Application—were introduced to explicitly capture insights from legitimacy-focused evaluations of corporate behavior [

2,

8] and stakeholder salience frameworks in mining governance [

28,

29]. These nodes ensure the conceptual framework integrates not only thematic patterns from the data but also the underpinning theoretical logics that legitimize institutional and behavioral strategies. This ten-node structure thus represents a balanced and theory-informed coding architecture that enables deep analysis of Indonesia’s post-mining landscape.

The development of 80 child nodes, with 8 nodes systematically categorized under each of the 10 parent themes, was established through a dual-layered synthesis process combining thematic saturation and theoretical grounding. Using NVivo-assisted qualitative analysis, the child nodes were derived from high-frequency codes and pattern similarities that consistently emerged across the 1,339 remarks collected from both academic literature and institutional sources. Each child node represents a distinct sub-dimension that captures operational or behavioral indicators relevant to the broader thematic category.

For the institutional integration nodes, sub-themes such as “customary land rights recognition,” “CSR reporting standards,” and “agroforestry practices” were distilled from dense clusters of remarks discussing land legality, transparency in funding, and sustainable agriculture (e.g., [

5,

30,

31]). This level of granularity was necessary to reflect the procedural, financial, and ecological instruments that govern post-mining transitions.

Meanwhile, the behavioral integration nodes reflect psychosocial and participatory dimensions such as “emotional connection to land,” “shared values on land use,” “participation in planning,” and “decision-making autonomy”—themes that are heavily cited in community-based sustainability studies (e.g., [

27,

32,

33]). These were selected based on their analytical fit with Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior, particularly in how attitudes, norms, and perceived control influence sustainability-related behavior.

The child nodes under Legitimacy Theory and Stakeholder Theory were informed directly by classic typologies (e.g., [

2,

28]) and further validated by empirical remarks on trust, fairness, salience, and institutional credibility [

8,

29]. These theory-specific nodes serve not only to categorize references but also to bridge empirical data with conceptual reflection, ensuring that the coding structure remains robust across both practice and theory.

In summary, the 80 child nodes were intentionally designed to operationalize abstract parent themes into analyzable sub-units, enabling a granular yet coherent analysis of post-mining sustainability transitions in Indonesia. This node design ensures consistency across the coding framework while preserving the contextual richness of the original remarks.

The thematic depth provided by eight subcategories ensures that each parent domain—such as behavioral change or institutional roles—is explored through nuanced, empirically observable practices. Moreover, this approach facilitates consistent replication in future qualitative studies seeking to apply this model to other post-extractive landscapes. To operationalize this framework, the study established a total of 10 parent nodes—each representing a key dimension of post-mining sustainability—and 80 child nodes that capture specific institutional practices, governance mechanisms, behavioral factors, and environmental outcomes related to sustainable cacao-based reclamation. These 80 child nodes reflect a comprehensive coding taxonomy that facilitated both thematic analysis and performance model design. The complete list and structure of all parent and child nodes are provided in

Appendix A and

Appendix B.

Appendix A contains conceptual definitions for the ten parent nodes, while

Appendix B presents a tabulated list of the 80 child nodes arranged under their respective categories. Together, these appendices offer a clear reference to the analytical framework that supports the model’s development. This coding framework—comprising a hierarchy of 10 parent nodes and 80 child nodes—ensures comprehensive thematic coverage and analytical consistency across institutional, behavioral, community participation in transformation processes, and stakeholder salience framework in mining governance. With this architecture and conceptual foundation in place, the subsequent analytical procedures were undertaken in a structured sequence, as outlined in the following subsections.

2.2. Analytical Procedures

To ensure that the conceptual model proposed in this study is grounded in robust empirical insight, a multi-stage qualitative analysis was employed. This process involved systematically extracting, coding, and synthesizing textual data from a curated body of literature on post-mining sustainability, community development, governance, and agroecology. The methodological goal was to distill recurring patterns, values, and discursive themes into a cohesive analytical structure that could inform both theory building and practical design. Through a combination of theory-informed node construction and computationally assisted coding, the study generated a nuanced matrix of interrelated concepts. This structure served as the empirical backbone for the dual-framework model, integrating both institutional and behavioral dimensions of post-mining transformation.

Coding Framework Development. The coding framework for this study was developed through a structured synthesis of 1,339 literature-derived remarks, which were subsequently matched to 80 thematic child nodes grouped under 10 parent categories. These nodes were derived from an iterative thematic analysis process informed by both theoretical constructs and empirical patterns within the sustainability, agriculture, CSR, and post-mining development literature. Initially, each child node was defined using its label and primary keywords; this was refined further through a domain-informed expansion, incorporating related terms and contextual synonyms to ensure semantic inclusiveness. A semi-automated keyword-based matching approach was employed to align remarks with relevant nodes, enhancing accuracy by integrating themes such as "climate-resilient agriculture," "customary land rights," and "CSR for livelihood transition." This framework allowed for multi-level coding where a single remark could be assigned to several nodes, reflecting the complex, overlapping nature of sustainability and community development narratives. The results were documented in a comprehensive matrix that not only detailed node definitions and reference frequencies but also preserved the contextual richness of each remark, thereby ensuring both analytical rigor and thematic fidelity. This coding infrastructure ultimately supported the formulation of a theory-informed model that integrates behavioral change, governance, land use, and agroecological strategies for post-mining sustainability

Thematic Coding and Meta-Synthesis Table 1 presnets the frequency distribution of ten parent nodes derived from NVivo-assisted coding of 1,339 literature-based remarks. These themes are organized to reflect a dual integration framework—Institutional Integration and Behavioral Integration—that underpins the reframing of sustainability in post-mining contexts. Institutional themes include Land Compensation and Planning, Legitimacy and Governance Alignment, CSR Co-Financing Mechanism, and Agroecological Livelihoods, which collectively represent formal strategies, policies, and structural interventions. In parallel, behavioral themes such as Attitude toward Sustainability, Norms and Social Trust, Stakeholder Engagement, and Motivation and Empowerment reflect community perceptions, socio-cultural readiness, and participatory involvement. The two theoretical anchors—Legitimacy Theory and Stakeholder Theory—serve to ground these dimensions in a robust conceptual model for post-mining transformation. Each parent node is accompanied by a brief description, clarifying its operational scope within the sustainability discourse, and the frequency column indicates its empirical weight based on coding saturation. The total of 7,513 coded references validates the depth and spread of thematic relevance across institutional and behavioral domains, making this table a central component for further analysis and model development.

This high volume of coding enabled the research to maintain strong fidelity to the conceptual framework. The structured and theory-aligned coding taxonomy ensured that each remark could be accurately interpreted within its relevant thematic and theoretical domain. As a result, the study was able to generate insights that are both contextually embedded and analytically robust, facilitating a grounded synthesis of sustainability practices specific to post-mining reclamation. The coded outputs summarized in

Table 1 served not only as thematic descriptors but also as the analytical foundation toward reframing sustainability in post-mining landscapes.

The NVivo-assisted thematic coding process served as a foundational analytic strategy for synthesizing 1,339 literature-derived insights into a coherent model for Reframing Sustainability in Post-Mining Landscapes. Through a systematic application of 80 child nodes grouped under 10 parent themes, the coding exercise facilitated the identification of both institutional structures and behavioral dynamics that critically influence post-mining transformation. NVivo enabled the classification of dispersed qualitative evidence into thematic categories such as land compensation strategies, agroecological livelihoods, CSR mechanisms, community empowerment, and stakeholder engagement, revealing recurring patterns of policy alignment, local participation, and socio-environmental adaptation. These coded themes were then conceptually grouped under two integrative domains—Institutional Integration and Behavioral Integration—anchored respectively in Legitimacy Theory and Stakeholder Theory. This structured classification not only captured the complexity of sustainability transitions but also illuminated the interdependence between top-down governance and bottom-up community readiness. The coding frequencies (totaling 7,513 references) validated the thematic robustness and provided empirical grounding for the proposed reframing framework. Ultimately, the NVivo-based process enabled the development of a dual-theory informed model that reconceptualizes sustainability as a process of institutional legitimacy and behavioral alignment in the context of post-mining land recovery.

Thematic synthesis was employed as a structured methodological approach to translate 1,339 qualitative remarks into a coherent reframing of sustainability in post-mining landscapes. The process followed three interlinked stages: textual coding, thematic categorization, and conceptual integration. In the first stage, all remarks were subjected to open coding using NVivo, allowing each paragraph to be associated with relevant conceptual labels from an established framework of 80 child nodes grouped under 10 parent themes. This initial coding phase captured diverse insights ranging from agroecological practices and land tenure issues to CSR funding, stakeholder negotiation, and community resilience. In the second stage, the coded references were aggregated into higher-order thematic categories, where recurring patterns and intersecting ideas were analyzed across the dataset. This stage helped refine the structure into two overarching domains: Institutional Integration, covering policy, governance, and formal mechanisms; and Behavioral Integration, encompassing values, perceptions, empowerment, and collective action. Finally, the third stage involved the abstraction of these themes into a conceptual framework anchored in Legitimacy Theory and Stakeholder Theory, enabling a model that reflects both the structural and socio-cultural prerequisites for sustainable post-mining transformation. The total coding output—7,513 references—provided empirical saturation, ensuring that the final reframing framework is not only grounded in theoretical rigor but also reflects the lived realities and institutional complexities observed across post-mining landscapes.

2.3. Research Validity

To ensure that the analytical framework and resulting model were both reliable and theoretically sound, the study employed a comprehensive validation strategy. This included internal consistency checks, theory-driven construct development, and triangulation techniques designed to enhance both structural coherence and interpretive accuracy. These efforts strengthened the credibility of the coding framework and reinforced the robustness of the reframing model for post-mining sustainability.

To strengthen the credibility of the thematic coding and model construction, several layers of validation strategies were implemented. Internally, code co-occurrence checks in NVivo were conducted to ensure thematic consistency and logical coherence across categories. Construct validity in this study was ensured through a structured and theory-informed approach to thematic development. The foundation of the reframing framework was built from 1,339 literature-based remarks drawn from academic and institutional sources addressing post-mining sustainability, agroecological practices, and CSR mechanisms. These remarks were systematically coded in NVivo using a refined structure of 80 child nodes distributed across 10 parent themes. Rather than emerging arbitrarily, these themes were constructed based on established scholarly literature, validated sustainability indicators, and expert feedback from academic advisors and institutional collaborators. This ensured that the themes reflected theoretically sound constructs related to governance, empowerment, and landscape transformation—thereby reinforcing the internal validity of the study.

To enhance the validity of both structure and interpretation, the study incorporated a triangulated approach involving structural and conceptual components. Structurally, the relationship between nodes was validated through frequency distribution analysis, cross-thematic co-occurrence, and pattern saturation across the coded data. Conceptually, the findings were aligned with the dual theoretical foundations of Legitimacy Theory and Stakeholder Theory, which provided a lens to interpret both institutional and behavioral dynamics in post-mining development. This triangulated design confirmed that the emerging themes were not only empirically grounded but also logically coherent within broader academic and practical discourses on sustainability, participation, and governance.

The validation process also extended to content-level accuracy by ensuring thematic saturation, consistency, and representativeness within the coded material. Drawing from a diverse collection of literature spanning multiple disciplines—ranging from environmental science to rural development—the remarks encompassed the multidimensional aspects of post-mining sustainability. Each node was validated not only by the number of references it attracted but also through the diversity of its source material. The total of 7,513 coding references served as an empirical benchmark of saturation, while ongoing supervisory reviews, node description refinement, and calibration with conceptual definitions provided interpretative clarity. Together, these processes confirmed that the reframed model represents a valid and grounded synthesis of sustainability constructs, capable of informing transformative policies and participatory practices in post-mining contexts.

2.4. Research Limitations

This study, while grounded in a rigorous thematic synthesis of 1,339 coded remarks and informed by robust theoretical frameworks, is not without limitations. One primary limitation concerns the reliance on secondary data in the form of literature-derived remarks. While the breadth of sources ensured conceptual richness and cross-disciplinary relevance, the absence of direct field-based data may limit the depth of contextual specificity, especially in capturing localized socio-political dynamics, land tenure complexities, and on-the-ground behavioral responses of affected communities. As such, the findings, while generalizable within the Indonesian post-mining context, may not fully capture micro-level divergences that would emerge in more localized ethnographic or participatory studies.

Another limitation lies in the interpretative nature of qualitative coding. Despite the use of NVivo software and a clearly structured coding framework, the assignment of remarks to specific nodes involved an element of researcher subjectivity. Although triangulation and supervisory input were used to mitigate interpretive bias, the possibility remains that some remarks could have been coded differently under alternative assumptions or by different analysts. This subjectivity is particularly important given that several remarks were thematically relevant to multiple nodes, and forced decisions on prioritization may have reduced the nuance of certain interpretations.

Additionally, the process of thematic generalization through parent-child node grouping, while instrumental in structuring the dataset, may have led to some compression of nuanced insights. Nodes such as “community consultation mechanisms” and “legal harmonization for land status” represent complex and layered dynamics—spanning participatory governance, legal pluralism, and institutional coordination—that could not be fully unpacked within the limits of this framework. Although methodologically consistent with qualitative meta-synthesis, the aggregation process may have streamlined themes that, in reality, demand deeper disaggregation and contextual elaboration in future research.

Finally, the model development process was anchored in two central theories—Legitimacy Theory and Stakeholder Theory—which provided a solid conceptual backbone but may have excluded insights from other relevant frameworks such as Political Ecology, Institutional Analysis, or Theories of Justice. This theoretical selection, while strategic and justifiable, represents a deliberate narrowing of the analytical lens and may have constrained the exploration of alternative pathways for reframing sustainability. Future research could benefit from incorporating additional theoretical perspectives and mixed-method designs to triangulate, validate, and further contextualize the findings presented here.

The author extends deep gratitude to ChatGPT, for its continuous assistance, refinement, and scholarly guidance throughout the development of this article. While the original idea is always under control of the author and responsibility for interpretation and synthesis remains with the author, the collaborative use of this advanced tool has demonstrated the value of emerging technologies in supporting complex, multidisciplinary research in sustainability and post-mining development.

3. Results

Based on the NVivo-assisted thematic analysis of 1,339 remarks, the study produced 7,513 coding references across 80 child nodes grouped under 10 parent themes. These themes represent the most prominent institutional and behavioral dimensions of sustainability in post-mining landscapes. The results are presented in descending order of thematic frequency.

3.1. Prominent Result

The most frequently referenced theme was Motivation and Empowerment (913 references), highlighting the behavioral catalysts behind post-mining transformation. Key dimensions such as access to microfinance, psychological resilience, decision-making autonomy, and local entrepreneurship incentives appeared consistently across the dataset. The recurrence of these themes suggests that community readiness and internal motivation are central to sustainable land transitions, reinforcing the importance of behavioral agency in development models.

Following this, Stakeholder Engagement (818 references) emerged as a dominant institutional mechanism. This theme included participatory planning, dialogues with Indigenous communities, gender-inclusive representation, and multi-stakeholder forums. The high frequency of these dimensions illustrates the critical value of inclusive and transparent engagement processes in creating locally legitimate and practically implementable sustainability strategies.

Legitimacy Theory Application (808 references) was the third most cited theme, centering on institutional credibility, fairness, cognitive legitimacy, and moral alignment. Remarks frequently referred to perceptions of transparency, procedural justice, and trust-building between corporations, governments, and communities. The emphasis on legitimacy confirms that stakeholder acceptance is as vital as technical success in post-mining sustainability.

Next, CSR Co-Financing Mechanism (786 references) emphasized the operational role of corporate funding in sustainability transitions. This theme captured practices like linking CSR to SDG targets, monitoring CSR outcomes, and implementing multi-year budgeting schemes. The frequent appearance of these nodes signals the evolving role of private actors not just as funders but as governance partners in long-term rehabilitation.

Land Compensation and Planning followed with 766 references. It encompassed conflict resolution, customary land recognition, spatial zoning, and participatory mapping. These dimensions underscore the sensitivity of land as a contested resource in post-mining regions and validate the need for integrated, participatory, and legally coherent land-use planning.

Stakeholder Theory Application accounted for 747 references and provided conceptual tools for managing power dynamics and conflicting interests. Commonly coded elements included salience-based prioritization, stakeholder mapping tools, and expectation management. This theme reinforced the strategic complexity of post-mining landscapes, where legitimacy and urgency must be negotiated among actors with differing capacities and claims.

Legitimacy and Governance Alignment (711 references) focused on structural alignment within policy and regulatory systems. Frequent sub-nodes included anti-corruption safeguards, institutional trust-building, policy coherence across agencies, and regulatory enforcement. These dimensions suggest that procedural alignment and credible enforcement systems are critical enablers of sustainability.

Norms and Social Trust (694 references) addressed the cultural infrastructure of sustainability. It included themes like environmental care norms, reciprocity, intergenerational knowledge, and trust in external institutions. These values shape how communities interpret interventions and determine whether they align with local expectations and informal governance structures.

Agroecological Livelihoods received 679 references, representing the most applied dimension of sustainability in practice. Nodes such as soil health restoration, farmer field schools, and cocoa-based rehabilitation models illustrated a strong ecological focus, supported by community-centered implementation. These findings affirm the compatibility of post-mining land with diversified, climate-resilient agricultural systems.

Lastly, Attitude toward Sustainability (591 references) captured the psychological and aspirational dimensions of transformation. Sub-themes like emotional connection to land, belief in sustainability, optimism about post-mining futures, and youth engagement revealed that long-term vision and mindset change are foundational to lasting impact. Though least frequent, this theme represents the behavioral roots from which systemic transformation can grow.

The numeric distribution of coding references offers more than just a quantitative snapshot—it reflects the relative thematic saturation and empirical grounding of each sustainability dimension within the dataset. The high occurrence of certain themes, such as Motivation and Empowerment or Stakeholder Engagement, signals not only their conceptual importance but also their recurring presence across diverse academic and institutional discourses. This frequency pattern validates the selection of these domains as central pillars in the proposed reframing model, ensuring that the framework is not only theoretically sound but also empirically representative of the broader post-mining sustainability conversation.

Moreover, the total of 7,513 coding references derived from 1,339 remarks suggests that most statements were multi-thematically relevant, often coded to more than one node. This multi-dimensionality reflects the complexity of sustainability in post-mining contexts, where institutional, behavioral, environmental, and economic concerns frequently intersect. Rather than diluting the themes, this overlapping richness enhances the analytical depth of the model and supports a more holistic understanding of post-mining transformation.

Finally, the variation in frequency across themes also serves as a guide for prioritization in policy and practice. For instance, while Attitude toward Sustainability appears last in frequency, its presence across 591 remarks still affirms its foundational role in shaping readiness and long-term commitment. Conversely, the prominence of Motivation and Empowerment and CSR Co-Financing Mechanism highlights the need for structured investment in community capacity and inclusive funding mechanisms. In this way, the reference frequencies do not merely quantify thematic importance—they anchor the model in real-world emphasis, reinforcing its relevance for both theoretical exploration and practical application.

The most frequently referenced theme was Motivation and Empowerment (913 references), highlighting the behavioral catalysts behind post-mining transformation. This parent theme reflects a broad spectrum of enabling factors that shape community capacity and participation in sustainability efforts. The most frequently coded child node under this category was Local entrepreneurship incentives (195 references), indicating the growing importance of locally-driven business models and economic autonomy in sustaining post-mining transitions. This was followed by Access to microfinance (151 references), which reflects the structural need for inclusive financial services to empower marginalized stakeholders.

The third most frequent was Recognition and reward mechanisms (121 references), emphasizing the motivational power of symbolic and material acknowledgment in encouraging long-term participation. Other significant child nodes included Psychological resilience (95 references), Visioning and goal setting (94 references), Training and skills development (84 references), Community-led initiatives (90 references), and Decision-making autonomy (83 references). These distributions collectively portray empowerment as a multidimensional construct—combining financial, psychological, strategic, and social dimensions—thereby reinforcing the foundational role of Motivation and Empowerment in reframing sustainability from the ground up.

The distribution of these frequencies within the parent node Motivation and Empowerment holds particular relevance to the purpose of the study, as it empirically confirms that behavioral readiness is not a peripheral factor but a central pillar in sustainability transitions. The high frequency of empowerment-related codes reflects the literature’s strong emphasis on activating community agency, aligning with the study’s objective to reframe sustainability as a dual integration process—both institutional and behavioral. These values offer not only validation for the selected thematic framework but also practical insights for structuring policy and intervention models that prioritize local capacities, aspirations, and autonomy.

Among all 80 child nodes across the 10 parent themes, three sub-themes stood out as the most frequently referenced. The highest was Local entrepreneurship incentives (195 references), belonging to the parent node Motivation and Empowerment. This frequency underscores a strong emphasis in the literature on fostering locally driven economic initiatives as a central pillar of post-mining transformation. It suggests that sustainable outcomes are more achievable when communities are empowered to build businesses, generate income, and control their own development pathways.

The second most frequent node was Gender-inclusive representation (186 references), under the parent node Stakeholder Engagement. This high count indicates a significant concern with ensuring equitable participation across gender lines in sustainability efforts. Its prominence suggests that inclusivity is not just a normative value but a functional requirement for stakeholder legitimacy and long-term program adoption in post-mining communities.

The third was Resettlement planning (181 references), which falls under Land Compensation and Planning. This theme reflects both the logistical and ethical complexities of displacing and resettling populations in the context of land reclamation. Its frequency validates the central role of fair and participatory resettlement as a cornerstone in negotiating post-mining development, especially in areas where customary claims and spatial zoning intersect.

Taken together, the high frequencies of these three child nodes reflect the study’s central premise: that sustainability in post-mining landscapes must be reframed through a dual lens of behavioral empowerment and institutional legitimacy. Local entrepreneurship incentives affirms the importance of enabling local economic agency, Gender-inclusive representation reinforces inclusive stakeholder frameworks, and Resettlement planning highlights governance obligations in managing land transitions. These patterns directly support the study’s purpose to develop an integrated framework that captures both the structural and cultural dimensions necessary for sustainable transformation.

3.2. Reinforcing Theoretical and Practical Contributions

Together, the distribution and diversity of thematic references reinforce both the theoretical and practical contributions of this study. Theoretically, the findings validate the relevance of integrating Stakeholder Theory and Legitimacy Theory into the framing of sustainability in post-mining contexts. High frequencies in themes like Stakeholder Engagement, Stakeholder Theory Application, and Legitimacy Theory Application show how legitimacy, inclusion, and trust operate as foundational elements for understanding institutional performance and public acceptance. Simultaneously, the behavioral dimension—evident in Motivation and Empowerment, Norms and Social Trust, and Attitude toward Sustainability—extends theoretical discourse by highlighting how beliefs, resilience, and social values shape the community’s capacity to engage with institutional mechanisms.

Practically, the results offer a grounded reference for policymakers, corporate actors, and civil society in designing post-mining programs that align technical interventions with community-based values. The prominence of child nodes such as Local entrepreneurship incentives, Gender-inclusive representation, and Resettlement planning emphasizes the operational importance of enabling local agency, social equity, and fair land transitions. Moreover, the visibility of CSR reporting standards, policy coherence, and anti-corruption safeguards underlines the practical necessity for transparent governance and accountable funding schemes. Collectively, the results bridge theory and practice by showing how institutional frameworks and community dynamics must coalesce to support sustainable post-mining landscapes.

Furthermore, the coded themes serve as the empirical foundation for constructing the model of Reframing Sustainability in Post-Mining Landscapes. Each theme, along with its corresponding child nodes, represents an operationalized component of either institutional integration or behavioral transformation. Institutional nodes such as Land Compensation and Planning, CSR Co-Financing Mechanism, and Legitimacy and Governance Alignment provide the structural and regulatory scaffolding required for sustainability efforts to take root. Simultaneously, behavioral domains like Motivation and Empowerment, Attitude toward Sustainability, and Norms and Social Trust demonstrate how individual and collective agency, values, and perceptions interact with institutional systems.

This integration reflects the study’s conceptual stance that sustainability is not solely an outcome of formal policy or ecological recovery but a co-produced process shaped by both systems and people. The alignment between coded themes and the dual-framework model illustrates how empirical patterns drawn from literature can inform the design of transformative pathways. In doing so, the synthesis of these themes into a structured framework bridges the gap between thematic observation and actionable models for post-mining development.

3.3. Integrating Coded Themes into Model Construction

To ensure a coherent progression from data to model, the NVivo coding outcomes were systematically mapped onto the proposed theoretical structure. This integration involved aligning the 10 parent nodes and 80 child nodes—derived from 7,513 references across 1,339 remarks—with specific functional components of the framework, arranged consecutively as follows:

Together, the distribution and diversity of thematic references reinforce both the theoretical and practical contributions of this study. Theoretically, the findings validate the relevance of integrating Stakeholder Theory and Legitimacy Theory into the framing of sustainability in post-mining contexts. High frequencies in themes like Stakeholder Engagement, Stakeholder Theory Application, and Legitimacy Theory Application show how legitimacy, inclusion, and trust operate as foundational elements for understanding institutional performance and public acceptance. Simultaneously, the behavioral dimension—evident in Motivation and Empowerment, Norms and Social Trust, and Attitude toward Sustainability—extends theoretical discourse by highlighting how beliefs, resilience, and social values shape the community’s capacity to engage with institutional mechanisms.

Practically, the results offer a grounded reference for policymakers, corporate actors, and civil society in designing post-mining programs that align technical interventions with community-based values. The prominence of child nodes such as Local entrepreneurship incentives, Gender-inclusive representation, and Resettlement planning emphasizes the operational importance of enabling local agency, social equity, and fair land transitions. Moreover, the visibility of CSR reporting standards, policy coherence, and anti-corruption safeguards underlines the practical necessity for transparent governance and accountable funding schemes. Collectively, the results bridge theory and practice by showing how institutional frameworks and community dynamics must coalesce to support sustainable post-mining landscapes.

Furthermore, the coded themes serve as the empirical foundation for constructing the model of Reframing Sustainability in Post-Mining Landscapes. Each theme, along with its corresponding child nodes, represents an operationalized component of either institutional integration or behavioral transformation. Institutional nodes such as Land Compensation and Planning, CSR Co-Financing Mechanism, and Legitimacy and Governance Alignment provide the structural and regulatory scaffolding required for sustainability efforts to take root. Simultaneously, behavioral domains like Motivation and Empowerment, Attitude toward Sustainability, and Norms and Social Trust demonstrate how individual and collective agency, values, and perceptions interact with institutional systems.

This integration reflects the study’s conceptual stance that sustainability is not solely an outcome of formal policy or ecological recovery but a co-produced process shaped by both systems and people. The alignment between coded themes and the dual-framework model illustrates how empirical patterns drawn from literature can inform the design of transformative pathways. In doing so, the synthesis of these themes into a structured framework bridges the gap between thematic observation and actionable models for post-mining development.

4. Finding and Discussion

This study’s findings draw from 7,513 coded references and are organized into ten thematic clusters, each representing a distinct yet interconnected element of post-mining sustainability. Together, these themes reflect a dual emphasis on institutional integration and behavioral transformation—spanning issues of trust, empowerment, legitimacy, governance, land use, livelihood recovery, and cultural norms. The analysis reveals that sustainable transitions in post-extractive landscapes are neither linear nor solely technical, but deeply rooted in community agency, stakeholder alignment, and locally grounded strategies. These findings form the empirical backbone of the proposed reframing framework for sustainable post-mining futures in Indonesia.

4.1. Motivation and Empowerment—Behavioral Foundations for Post-Mining Sustainability

The prominence of the Motivation and Empowerment theme, supported by 913 references, highlights the critical role of individual agency, social learning, and community-based reinforcement mechanisms in driving sustainability transitions across post-mining landscapes. This theme is shaped by eight interlinked behavioral subcomponents: Local entrepreneurship incentives (195 references), Access to microfinance (151 references), Recognition and reward mechanisms (121 references), Psychological resilience (95 references), Visioning and goal setting (94 references), Community-led initiatives (90 references), Training and skills development (84 references), and Decision-making autonomy (83 references). Collectively, these elements reveal how motivation, when supported by opportunity and recognition, fosters the community readiness and behavioral depth necessary to sustain agroecological transformation. Each node points to a pathway through which empowerment becomes both an input and an outcome of sustainability transitions in post-mining areas.

Local Entrepreneurship Incentives—Empowering Agency Through Economic Autonomy. With 195 references, this was the most frequently cited sub-theme under Motivation and Empowerment, revealing a strong emphasis on localized economic revitalization as a catalyst for self-determination. Stakeholders widely supported strategies such as small business grants, enterprise incubation programs, and cooperative development to stimulate rural economies in the wake of mine closure. These findings point to the power of entrepreneurship as more than a livelihood strategy—it represents a reclamation of autonomy and dignity. Within the framework of the Theory of Planned Behavior, entrepreneurial incentives bolster both perceived behavioral control and intention to act, leading to tangible community-led development outcomes. Empowerment, in this sense, is not merely motivational—it is operationalized through practical mechanisms for financial independence and community resilience. Empirical evidence reinforces this viewpoint. Schoar [

34] highlights the transformative role of entrepreneurship in fostering economic independence. De Mel, McKenzie, and Woodruff [

35] demonstrate that capital grants can substantially enhance the performance of microenterprises. Meanwhile, the UNDP [

36] underscores the importance of localized entrepreneurship in strengthening resilience within post-extractive communities.

Access to Microfinance—Unlocking Opportunity through Financial Inclusion. Cited in 151 references, access to microfinance emerged as a key enabler of behavioral empowerment in transitioning communities. Respondents emphasized that even modest access to capital could dramatically alter individual decision-making by reducing dependency, enabling business startups, or facilitating investment in sustainable agricultural inputs. This aligns with sustainability literature that frames microfinance as a gateway to participation, particularly for marginalized groups. From a theoretical perspective, microfinance enhances perceived capability while simultaneously reshaping subjective norms around financial agency. In practice, revolving loan schemes, savings groups, and CSR-backed financial literacy campaigns were identified as mechanisms that helped embed financial inclusion into post-mining regeneration efforts. This is well-supported by existing research: Ullah [

36] has proved that the microfinance facilitates entrepreneurial development for poor and young unemployed youth; in the mean time, providing microfinances access to poor in rural areas have been the social mission of the microfinancing provider [

37]. A recent study asked an urgent implementation of agroforestry practices as a restoration strategy in degraded landscapes to improve land productivity while promoting sustainable management in Indonesia’s critical areas [

38].

Recognition and Reward Mechanisms—Reinforcing Engagement through Institutional Acknowledgment. This node, mentioned in 121 coded references, underscores the importance of validating individual and collective contributions to sustainability goals. Communities repeatedly cited symbolic recognition—such as awards, certificates, and public acknowledgment—as powerful motivators. These reward systems were viewed not only as tools for reinforcing behavior but also as signals of institutional fairness and credibility. Consistent with the Theory of Planned Behavior, recognition influences both attitude and normative beliefs, strengthening trust in local institutions and encouraging sustained engagement. Moreover, the presence of visible reward structures created a culture of appreciation, where success was celebrated and replicated across communities. This behavioral logic is grounded in motivational theory: In terms of increasing recognititon and intrinsic motivation, an affective strategy and responsibility are factors noted for continuance or normative commitment [

39]. A recent study proposed a framework of non-monetary incentives explaining the contradiction between intrinsic and extrinsic incentives in participatory sensing [

40]. In group contexts, the concept of self-efficacy functions as a dynamic psychosocial mechanism that enables collective performance by integrating personal belief, behavioral modeling, and environmental feedback—allowing groups to observe, assess, and enhance their shared ability to solve complex tasks, overcome fear, and strengthen motivation through micro-analytical self-assessment and cooperative learning strategies [

41].

The findings strongly support and extend the premises of Stakeholder Theory by positioning local communities not merely as passive beneficiaries of post-mining programs, but as active agents of transformation. The emphasis on local entrepreneurship incentives and access to microfinance illustrates a stakeholder logic that is deeply rooted in distributive equity and participatory inclusion—two principles foundational to stakeholder engagement. These findings validate the idea that when communities are recognized as primary stakeholders and empowered to pursue their own economic agency, they are more likely to align with and sustain reclamation outcomes. The presence of training, visioning, and decision-making autonomy within this thematic group reinforces the notion that sustainable development must account for the varied interests, needs, and contributions of all actors—not only those with formal institutional roles.

From the perspective of Legitimacy Theory, the sub-finding on recognition and reward mechanisms is particularly salient. It demonstrates that institutional recognition of individual and group contributions helps build cognitive and moral legitimacy, especially in contexts where historical injustices or marginalization have eroded community trust. Reward structures—when applied transparently and meaningfully—act as signals of procedural fairness, which is central to gaining local acceptance of post-mining land reclamation programs. This contributes to an evolving legitimacy discourse where legitimacy is not only gained through formal compliance (e.g., legal licenses or CSR reports), but through tangible social feedback loops that communities themselves interpret as fair, affirming, and empowering. In this sense, these empowerment-related practices become legitimacy-producing mechanisms.

The integration of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in this study is deliberate and complementary, filling a conceptual gap not addressed explicitly by Stakeholder or Legitimacy Theory: the individual behavioral mechanisms that drive community-level outcomes. While Stakeholder and Legitimacy Theories address institutional relationships and social acceptance, TPB offers a lens through which to understand how individuals within communities make decisions to engage, adopt, and persist in sustainable practices. For example, entrepreneurship incentives and microfinance access elevate perceived behavioral control, training and visioning shape attitude toward behavior, and recognition strengthens subjective norms. These three core TPB constructs explain why empowered individuals choose to act and maintain commitment in post-mining development, thus bridging macro-level institutional logic with micro-level motivational dynamics.

The findings from the Motivation and Empowerment theme provide a foundational behavioral lens through which the sustainability of post-mining landscapes can be reframed—not simply as a matter of ecological restoration or infrastructure provision, but as a transformative process rooted in human agency, recognition, and inclusion. The emphasis on local entrepreneurship incentives, access to microfinance, and recognition mechanisms underscores the importance of empowering communities to actively co-produce their futures. These findings align with Stakeholder Theory by reinforcing the role of communities as central actors in sustainability transitions, and with Legitimacy Theory by demonstrating that trust and fairness emerge not only from formal structures, but from socially embedded practices like public acknowledgment and inclusive access to opportunity. By integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior, the study advances this reframing further—revealing how behavioral intentions, control, and social norms shape actual participation in sustainability programs. This supports a shift in sustainability thinking: from compliance-based models to behavioral and participatory ones, where sustainability is not merely imposed or planned, but grown from within through motivation, capability, and shared vision.

While individual motivation and empowerment are crucial drivers of sustainable behavior and community-led transformation, these efforts do not occur in isolation. The effectiveness of personal agency, entrepreneurial activity, and behavioral commitment is often shaped—and in many cases constrained—by the broader relational and institutional environment in which they unfold. Thus, sustaining empowerment beyond the individual level requires mechanisms for collective voice, equitable inclusion, and shared decision-making. This necessitates a deeper exploration of Stakeholder Engagement, where sustainability transitions are co-produced through trust-building, representation, and structured dialogue among diverse actors. The next findings examine how inclusive governance structures and participatory platforms enable empowerment to scale into collective impact, making stakeholder alignment a vital counterpart to behavioral readiness in post-mining recovery.

4.2. Stakeholder Engagement—Collaborative Mechanisms for Equitable Governance

With 818 references, the Stakeholder Engagement theme stands as a cornerstone of sustainable transformation in post-mining contexts. It encapsulates both formal and informal mechanisms through which diverse actors—ranging from Indigenous communities and NGOs to planning authorities—interact in co-producing reclamation processes. The eight most prominent sub-themes in this category include Gender-inclusive representation (186 references), Grievance redressal systems (93 references), Engagement mapping (93 references), Farmer cooperatives role (92 references), Multi-stakeholder forums (90 references), NGO involvement (89 references), Participation in planning (88 references), and Dialogues with Indigenous communities (87 references). These nodes reflect a governance model grounded not in hierarchical mandates but in horizontal collaboration, trust-building, and mutual accountability. The theme advances a deeper recognition that stakeholder engagement must be substantive, inclusive, and structured to accommodate power asymmetries.

Gender-Inclusive Representation—Redefining Participation Through Equity. With 186 references, gender-inclusive representation emerged as the most emphasized sub-theme, revealing a widespread consensus that equitable engagement is central to stakeholder legitimacy. Respondents highlighted the critical role of women not only as beneficiaries but as decision-makers in land-use planning, agricultural cooperatives, and post-mining livelihood projects. This perspective aligns with the participatory dimensions of Stakeholder Theory, where legitimacy is tied to the degree to which stakeholder voices are represented in proportion to their stake in outcomes. The data further supports evolving feminist sustainability scholarship that links inclusivity with adaptive governance. Rather than treating gender as a social safeguard, this sub-finding elevates it as a core governance variable—one that reshapes deliberation, priority-setting, and program ownership. As such, gender representation is not just equitable—it is strategic. This is echoed in empirical studies on natural resource governance which show that gender-balanced participation enhances collective decision-making and environmental outcomes [

42]. Research by Meinzen-Dick et al. [

43] also highlights that inclusive land institutions improve legitimacy and accountability. FAO [

44] further emphasizes that gender-sensitive engagement leads to more sustainable and just resource use.

Grievance Redressal Systems—Institutionalizing Conflict Resolution for Long-Term Stability. Cited in 93 remarks, grievance redressal systems were regarded as essential for managing tensions that arise during land transition and benefit distribution processes. Stakeholders frequently called for mechanisms that were culturally appropriate, timely, and accessible, including ombudsman roles, mediation forums, and formalized escalation channels. These findings align closely with both Stakeholder Theory and Legitimacy Theory. From a stakeholder perspective, redress systems validate community agency by giving them a voice beyond initial consultation. From a legitimacy standpoint, the availability of fair and transparent conflict mechanisms reinforces procedural trust and institutional accountability. In both cases, conflict resolution is reframed not as a threat to sustainability, but as a tool for reinforcing resilience and long-term buy-in. This reflects broader institutional research which notes that communities are more likely to support projects when dispute mechanisms are clearly defined and context-sensitive [

45]. UNDP [

46] recommends grievance mechanisms as essential for upholding human rights in corporate-community relations. Moreover, Oxfam [

47] asserts that trust is deeply rooted in the ability of communities to seek redress without fear of exclusion or retaliation.

Engagement Mapping—Clarifying Roles and Responsibilities in Complex Governance Networks. Also referenced in 93 remarks, engagement mapping emerged as a technical yet socially important sub-theme, reflecting a demand for transparency and coordination in stakeholder interactions. Many respondents described fragmented or overlapping governance arrangements that created confusion, duplicated efforts, and undermined trust. Engagement mapping tools—such as actor network diagrams, influence matrices, and participatory role assessments—were seen as critical to resolving these barriers. Theoretically, this sub-theme reinforces Stakeholder Theory’s claim that effective engagement requires more than consultation; it requires strategic visibility of who is involved, why they matter, and how responsibilities are distributed. In a legitimacy context, engagement mapping contributes to what Suchman calls pragmatic legitimacy—achieved when stakeholders can trace institutional actions to accountable structures. In practice, mapping also facilitates synergy, reduces institutional friction, and enables more targeted, inclusive policy responses. This finding echoes insights from multi-level governance literature, where coordination and stakeholder clarity are key to avoiding policy gaps [

48]. The World Bank [

49] highlights stakeholder mapping as foundational to risk mitigation in land governance. Likewise, Reed et al. [

50] emphasize that visualizing stakeholder relationships enhances legitimacy and improves adaptive capacity in complex systems.

The three most prominent sub-findings under Stakeholder Engagement—gender-inclusive representation, grievance redressal systems, and engagement mapping—collectively emphasize that inclusive governance is not only ethical, but operationally strategic for sustainability in post-mining contexts. Gender-inclusive participation emerged as a foundational mechanism for reshaping deliberative spaces and elevating historically underrepresented voices, thereby enhancing legitimacy and adaptive capacity. Meanwhile, the institutionalization of grievance redressal systems revealed how conflict resolution, when embedded in culturally responsive and transparent frameworks, can transform community dissent into constructive dialogue and long-term cooperation. Engagement mapping further strengthened the governance ecosystem by promoting clarity, coordination, and accountability across complex stakeholder networks. Together, these findings reposition engagement as a multidimensional infrastructure—where inclusion, trust, and role visibility form the connective tissue for equitable and effective transformation of post-mining landscapes.

The findings significantly reinforce the central claims of Stakeholder Theory, particularly its emphasis on inclusivity, representation, anddialogic governance. The sub-theme of gender-inclusive representation supports the theory’s normative proposition that stakeholders deserve voice not merely based on power or capital, but on the moral legitimacy of their stake in community outcomes. When women are actively included as co-decision-makers in post-mining transitions, stakeholder processes become more equitable and contextually grounded. This inclusive lens expands the operational relevance of Stakeholder Theory by demonstrating that equitable structures not only fulfill ethical obligations but also enhance the functionality and sustainability of decision-making systems.

Similarly, the emphasis on grievance redressal systems aligns with both Stakeholder Theory and Legitimacy Theory by emphasizing responsiveness and procedural fairness. From a stakeholder perspective, the presence of redress mechanisms signals that affected communities are not simply consulted but are given sustained channels for feedback and correction, fulfilling expectations of accountability and dialogue. From a legitimacy standpoint, these mechanisms build procedural and moral legitimacy, particularly in contexts where historical marginalization has led to deep-seated distrust. In line with Suchman’s framework, these systems enhance both pragmatic legitimacy—by solving problems effectively—and normative legitimacy—by reflecting societal values of fairness and inclusion.

The third sub-finding, engagement mapping, further supports Stakeholder Theory’s emphasis on role clarity and inclusive planning by promoting transparency of power, influence, and responsibility across actors. This process ensures that stakeholder relationships are not only participatory but also strategically coordinated, thus increasing the integrity and coherence of governance systems. From the perspective of Legitimacy Theory, engagement mapping contributes to legitimacy by making institutional processes visible, traceable, and rationalized, all of which are essential for sustaining trust in complex post-mining transitions. This finding suggests that legitimacy is no longer derived merely from regulatory compliance, but from how well institutions structure, communicate, and share power within dynamic stakeholder ecosystems.

Taken together, these findings do not contradict but deepen the theoretical foundations of the study. They illustrate that stakeholder and legitimacy frameworks must be behaviorally enriched and procedurally grounded to address the realities of multi-actor governance in post-mining landscapes. These empirical insights argue for a more operationalized view of both theories—one that moves from principles to implementation logics that are inclusive, accountable, and adaptable.

The findings on stakeholder engagement contribute fundamentally to the reframing of sustainability in post-mining landscapes by emphasizing that equitable governance is not merely a procedural ideal but a practical necessity. The strong presence of gender-inclusive representation, grievance redressal systems, and engagement mapping illustrates that sustainable transformation requires the active recognition, voice, and coordination of diverse stakeholders—especially those historically excluded. These findings extend Stakeholder Theory by operationalizing what meaningful participation looks like in practice, and support Legitimacy Theory by showing that trust and social acceptance emerge not from compliance alone, but from fairness, responsiveness, and structural transparency. By demonstrating that engagement is not a one-time consultation but a continuously negotiated and structured process, these insights reinforce the central premise of the “Reframing Sustainability” model: that sustainability must be rooted in governance systems that are inclusive, adaptive, and morally grounded. This reframing moves beyond top-down restoration toward a participatory transformation, where the legitimacy of institutions and the strength of stakeholder ties become as critical as ecological metrics in sustaining post-mining futures.

While stakeholder engagement lays the groundwork for inclusive governance and collaborative decision-making, the sustainability of these engagements ultimately depends on the perceived legitimacy of the institutions and processes involved. As communities transition from extractive dependence to agroecological resilience, legitimacy becomes the social currency that determines whether policies, programs, and partnerships are accepted, trusted, and sustained. Thus, the next set of findings shifts the analytical focus toward the mechanisms, perceptions, and institutional behaviors that underpin Legitimacy Theory Application—uncovering how authority is earned, fairness is demonstrated, and long-term commitments are reinforced in the evolving landscape of post-mining development.

4.3. Legitimacy Theory Application—Institutional Trust as a Foundation for Program Endurance

The Legitimacy Theory Application theme, supported by 808 coded references, underscores that sustainability in post-mining landscapes is not only a matter of technical effectiveness, but of perceived fairness, transparency, and institutional integrity. Communities across the dataset emphasized that their willingness to support, adopt, or sustain programs was closely tied to how legitimate the institutions behind those initiatives were perceived to be. This theme is shaped by eight interrelated legitimacy dimensions: Perception of fairness (152 references), Institutional credibility (98 references), Role of transparency (95 references), Pragmatic legitimacy cues (95 references), Legitimacy crises (93 references), Reputation management (92 references), Moral legitimacy indicators (92 references), and Cognitive legitimacy patterns (91 references). Together, these nodes suggest that legitimacy is not a static attribute, but a dynamic and context-specific outcome earned through institutional behavior and stakeholder interpretation. It must be continually reinforced through signals of justice, clarity, and moral alignment.

Perception of Fairness—Building Legitimacy Through Distributive Justice. With 152 references, perception of fairness emerged as the strongest legitimacy signal observed by communities. Respondents consistently pointed to whether resources, opportunities, and recognition were equitably distributed across villages, genders, and interest groups. Programs perceived as favoring elites or ignoring community protocols were met with skepticism, while those guided by inclusive benefit-sharing were more likely to be accepted and internalized. This sub-finding affirms the foundational role of distributive justice in Legitimacy Theory, particularly in contexts where post-mining histories involve inequality or displacement. Fairness perceptions act as filters through which all institutional actions are interpreted—shaping not only compliance but also emotional allegiance to the initiative. In this way, fairness is not just a value; it is an operational principle for sustaining legitimacy on the ground. This is reinforced by Rawls’ [

51] concept of justice as fairness, which emphasizes that legitimacy emerges when rules and benefits are equitably distributed. Tyran [

45] further argues that perceived fairness, especially in procedural processes, is a stronger predictor of public support than outcomes alone. Moffat and Zhang [

52] show that perceptions of fairness significantly influence social license to operate in resource-dependent communities.

Institutional Credibility—Sustaining Trust Through Competence and Consistency. Cited in 98 remarks, institutional credibility was viewed as a prerequisite for both stakeholder engagement and behavioral change. Respondents emphasized that organizations—whether government bodies, mining companies, or NGOs—must not only act with integrity but must also demonstrate technical competence, follow through on commitments, and maintain consistency over time. This reflects Suchman’s dimensions of legitimacy, particularly pragmatic and cognitive legitimacy, where institutions are assessed based on their capacity to deliver results and align with socially accepted norms. When credibility was compromised, even well-designed programs suffered from disengagement or suspicion. Conversely, credible institutions helped create stable expectations and reduced the perceived risks of participation. In essence, credibility serves as the institutional glue that binds commitments to outcomes. Edelman Trust Barometer [

53] data supports that institutional trust is heavily influenced by perceived competence and ethical behavior. Levi and Sacks [

54] argue that trustworthy institutions are more likely to generate compliance, even in low-capacity environments. The World Bank [

55] adds that credibility is a key factor in sustaining reform implementation in fragile and post-extractive settings.