Submitted:

27 April 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

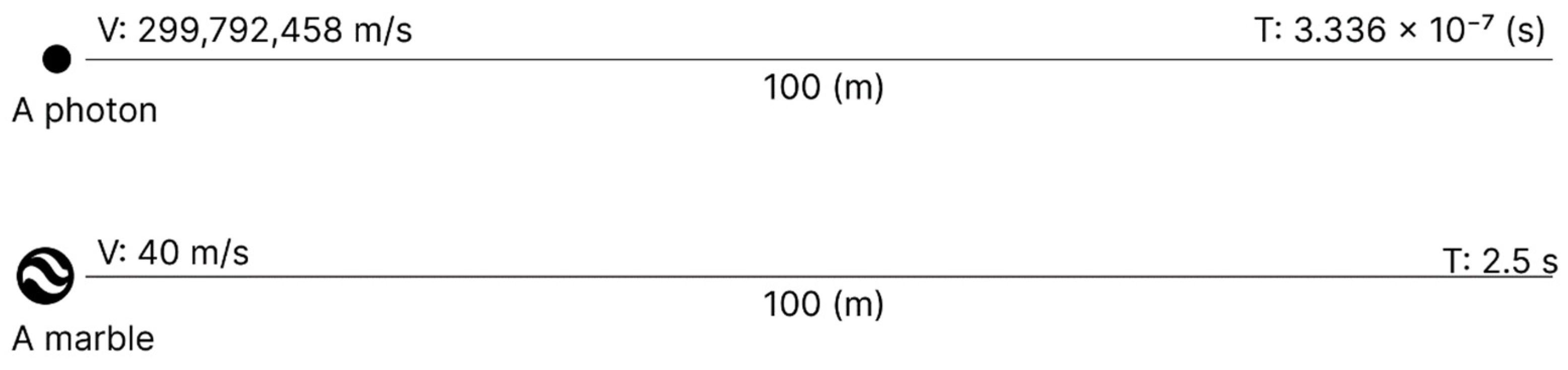

2. Thought Experiment: Photon vs. Marble

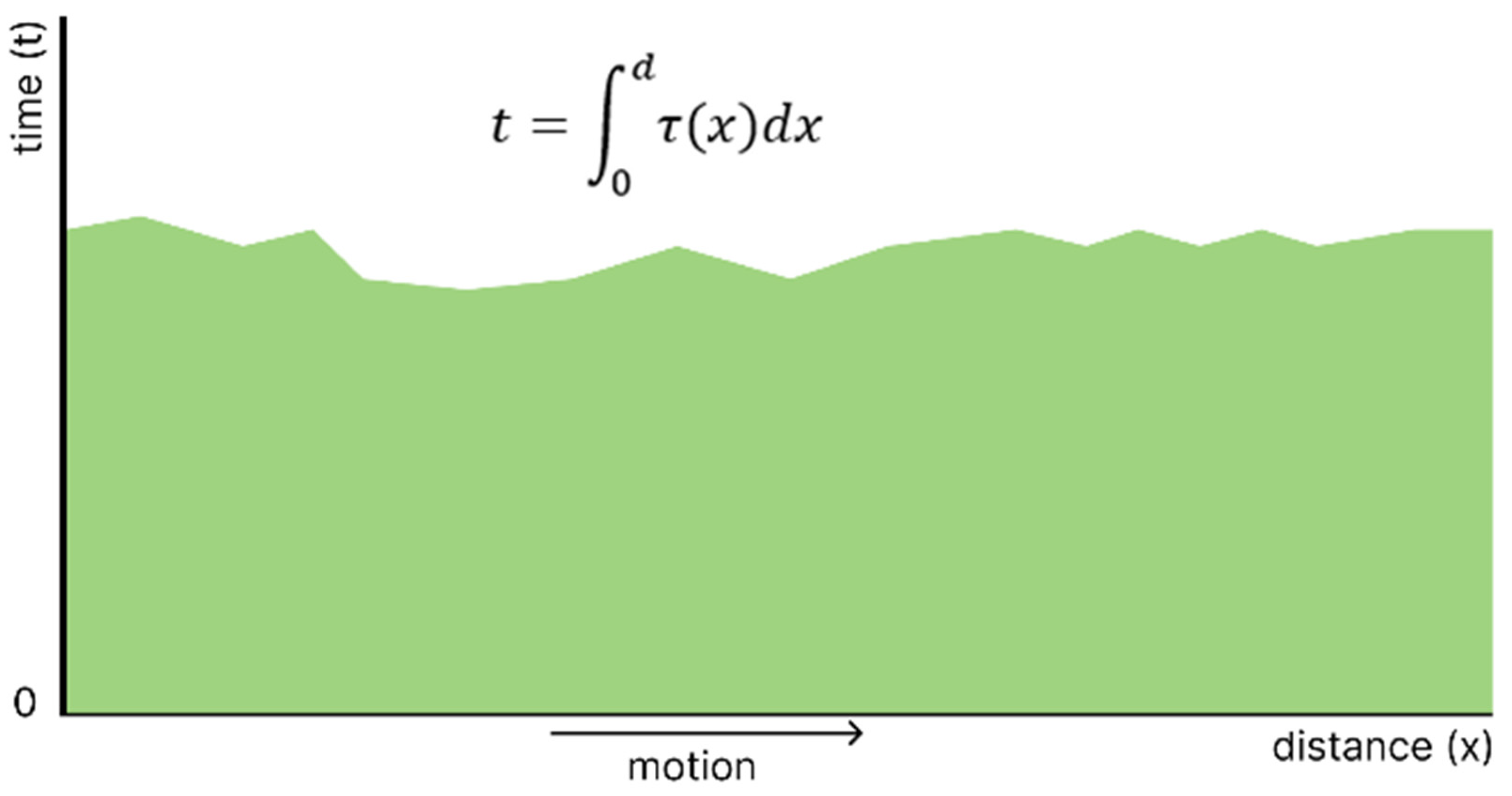

3. Conceptual Framework

4. Connection to Established Physics

5. Reinterpretation of Quantum Phenomena

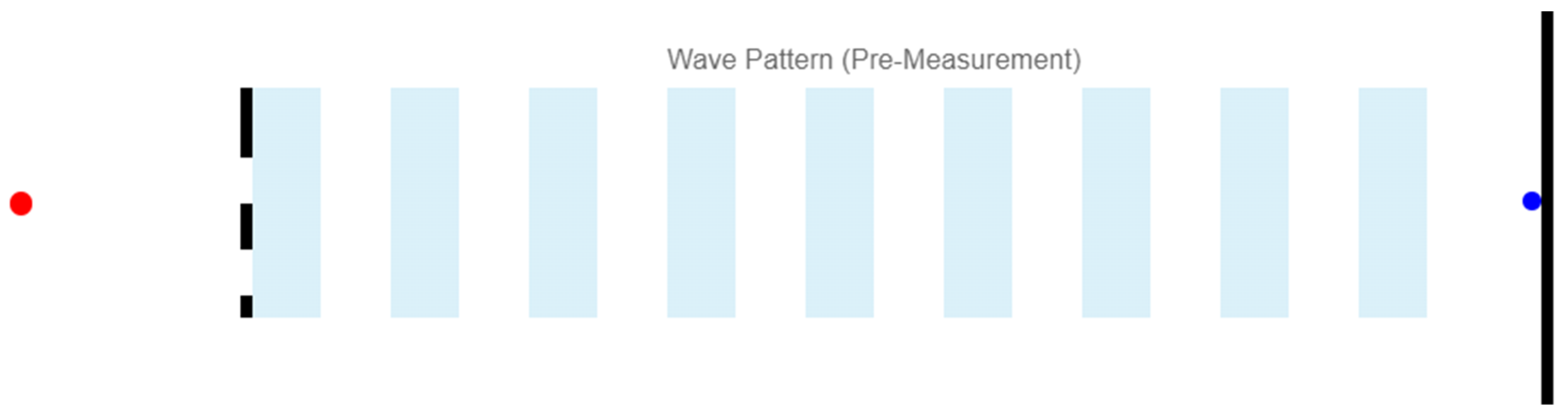

5.1. Wave-Particle Duality

5.2. Superposition

5.3. Entanglement

5.4. Conceptual Note

6. Implications and Challenges

6.1. Implications

- Velocity as a Reflection of Stop Distribution: The hypothesis redefines velocity not as a measure of continuous motion but as an emergent property determined by the distribution and duration of stops along a path. For instance, in the thought experiment from Section 2, the marble’s slower effective speed () compared to the photon’s () arises from a greater accumulation of stop durations, as modeled by , rather than a difference in intrinsic motion capability. Acceleration, in turn, becomes a mechanism that reduces the stop duration per unit distance, thereby increasing an object’s effective speed.

- Energy and Stop Mitigation: Energy, particularly relativistic energy, may play a critical role in mitigating stops, akin to overcoming inertia in classical mechanics. The updated model suggests that higher energy reduces , decreasing total travel time. In the quantum realm, as explored in Section 5, this could manifest as particles tunneling through potential barriers, effectively bypassing stops that would otherwise anchor their states, suggesting a reinterpretation of energy as a modulator of temporal interruptions.

- Quantum Measurement as Stops: Building on Section 5’s exploration of quantum phenomena, the hypothesis posits that measurement events act as stops, collapsing quantum superpositions or resolving entangled states. This provides a speculative lens on the measurement problem, framing stops as the points where timeless quantum behavior interfaces with observable temporality, entering the time domain we perceive.

6.2. Challenges

- Mathematical Rigor: A primary obstacle is developing a mathematical framework to quantify across diverse systems. For macroscopic objects, this might involve parameters like mass, velocity, or external interactions, while in quantum systems, stops could correlate with quantum states or decoherence effects. The current model relies on a provisional coupling constant , which varies by example (e.g., for the marble, for a cold atom), necessitating a predictive formulation—potentially informed by quantum field theory [6].

- Relativity Compatibility: The hypothesis should align with special relativity, particularly the finite speed of light and the zero proper time of photons. It suggests photons experience minimal stops (), yielding , while massive objects incur greater delays due to mass-dependent terms. This should ensure observed coordinate times remain consistent with relativistic predictions, and reconciling the continuous stop model with spacetime geometry poses a formidable challenge.

- Testability and Distinction from Standard Physics: Experimental validation requires detecting stop-like behaviors, such as anomalies in high-precision timing of particle motion or quantum state transitions. Distinguishing these from established phenomena—like quantum fluctuations or relativistic time dilation—is a significant hurdle. The hypothesis must propose unique, observable signatures, potentially tied to variations in , to differentiate itself from current theories.

6.3. Future Research Directions

- Ultra-Precise Particle Timing: High-frequency atomic clocks or optical lattice clocks can measure travel times of photons and massive particles over fixed distances. Deviations from expected times correlated with mass or energy could support the hypothesis.

- Interferometry for Quantum Stopping Events: Using Mach-Zehnder interferometry, unexpected phase shifts or coherence losses in quantum particles may indicate discrete stopping events.

- High-Energy Particle Accelerators: Analyzing time-of-flight data for particles at varying energy levels may reveal that increased energy reduces stop durations, altering effective velocity beyond relativistic predictions.

7. Conclusions

References

- Newton, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Royal Society, London, 1687).

- Einstein, "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies," Annalen der Physik 17, 891 (1905).

- J. B. Hartle, Gravity: An Introduction to Einstein’s General Relativity (Addison-Wesley, 2003).

- Rovelli, "Quantum Gravity," Living Reviews in Relativity 1, 1 (1998).

- P. W. Higgs, "Broken Symmetries and the Masses of Gauge Bosons," Physical Review Letters 13, 508 (1964). [CrossRef]

- P. A. M. Dirac, The Principles of Quantum Mechanics (Oxford University Press, 1958).

- J. Barbour, "The Nature of Time," arXiv:0903.3489 (2009).

- E. Schrödinger, "Die gegenwärtige Situation in der Quantenmechanik," Naturwissenschaften 23, 807 (1935).

- J. A. Wheeler, "The ‘Past’ and the ‘Delayed-Choice’ Double-Slit Experiment," in Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Theory (Academic Press, 1978).

- H. Everett, "Relative State Formulation of Quantum Mechanics," Reviews of Modern Physics 29, 454 (1957). [CrossRef]

- J. S. Bell, "On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox," Physics 1, 195 (1964).

- Y. Aharonov et al., "Quantum Mechanics of Time," arXiv:1410.4308 (2014).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).