Submitted:

02 May 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biological Role of Tregs in the Local Immune System

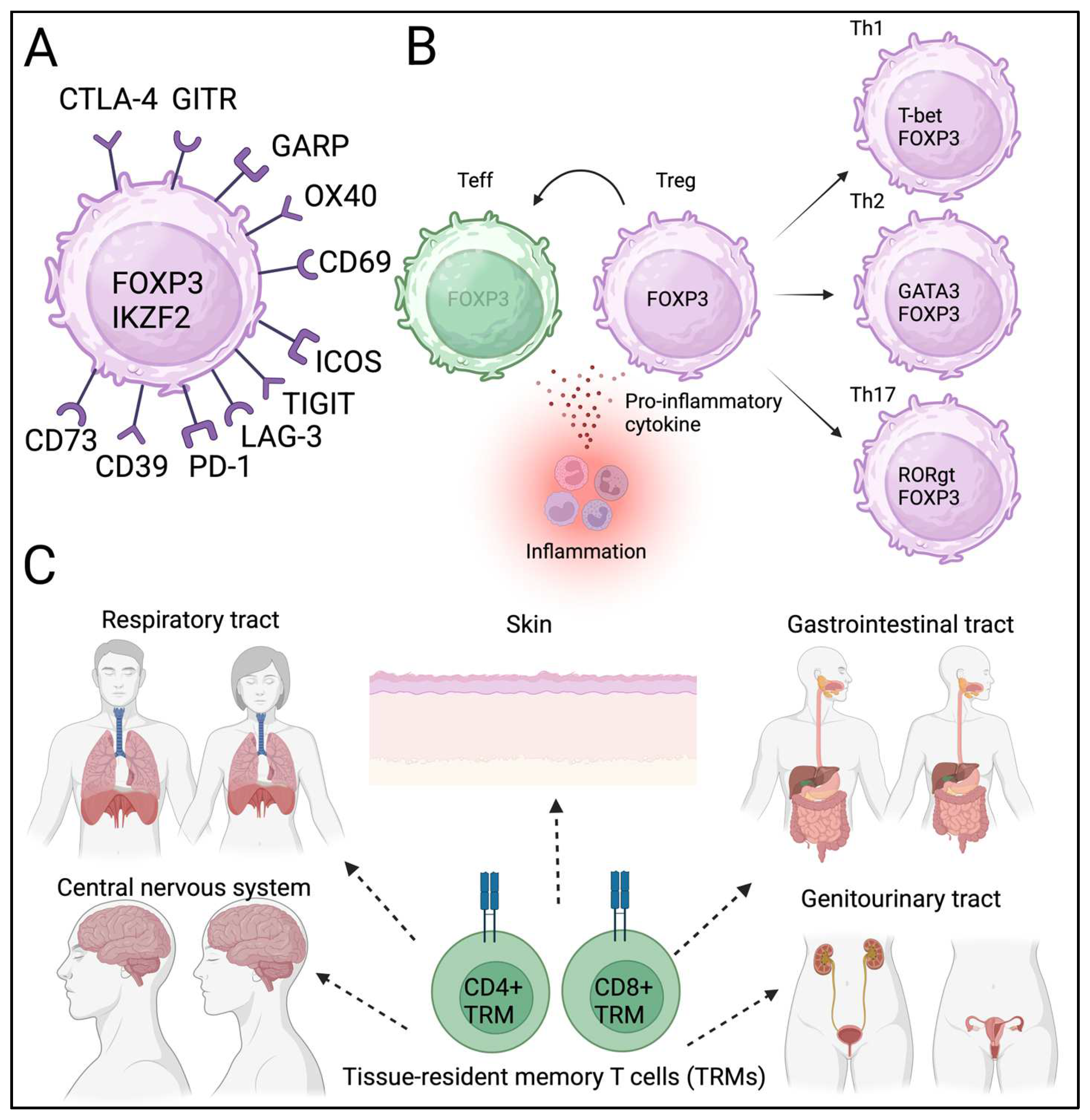

2.1. Phenotype and Function of Tregs

2.2. Plasticity and Heterogeniety of Tregs

2.3. Tissue-Resident Tregs

3. Phenotype and Function of Tregs Isolated from TME

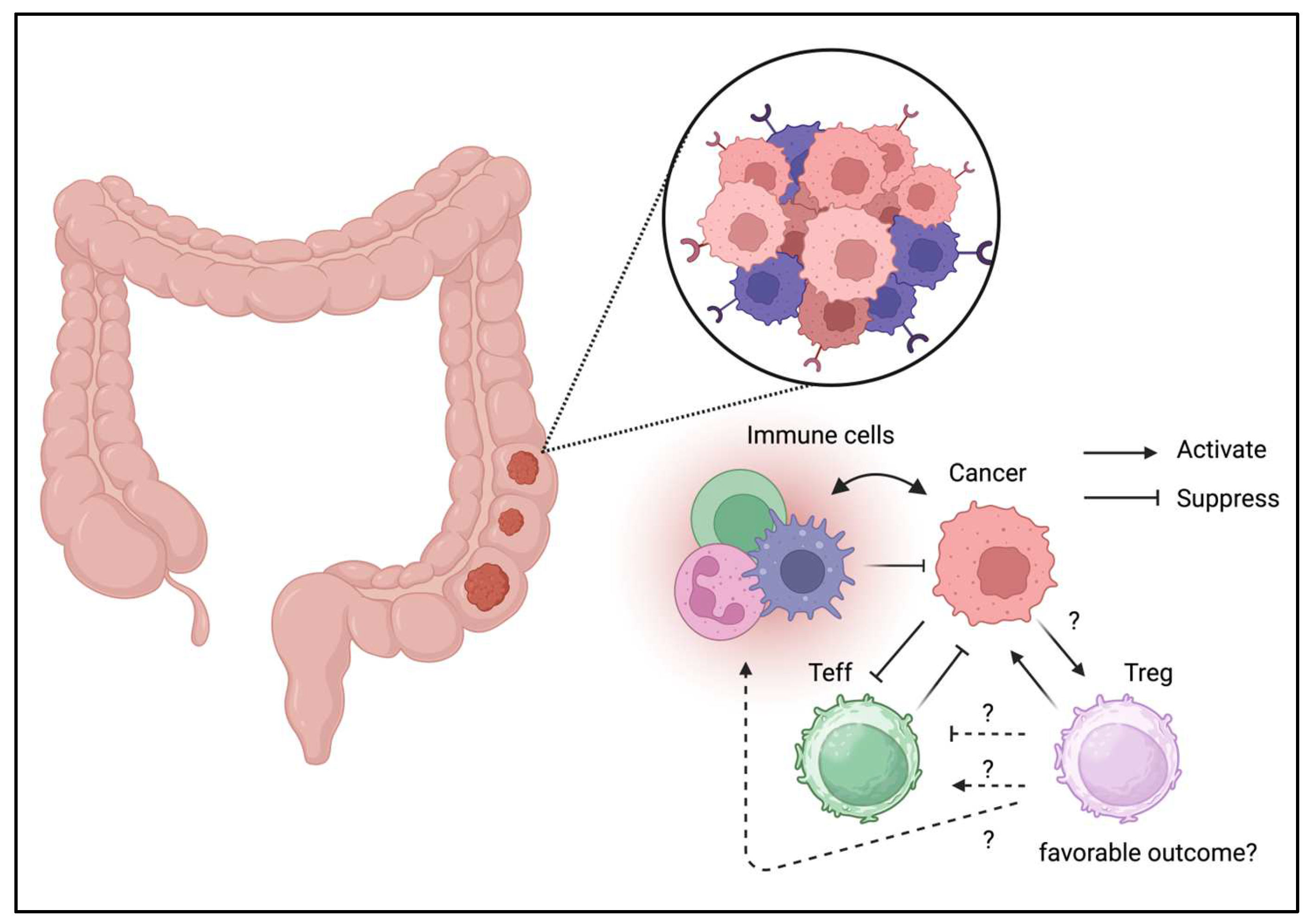

3.1. Colorectal Cancer

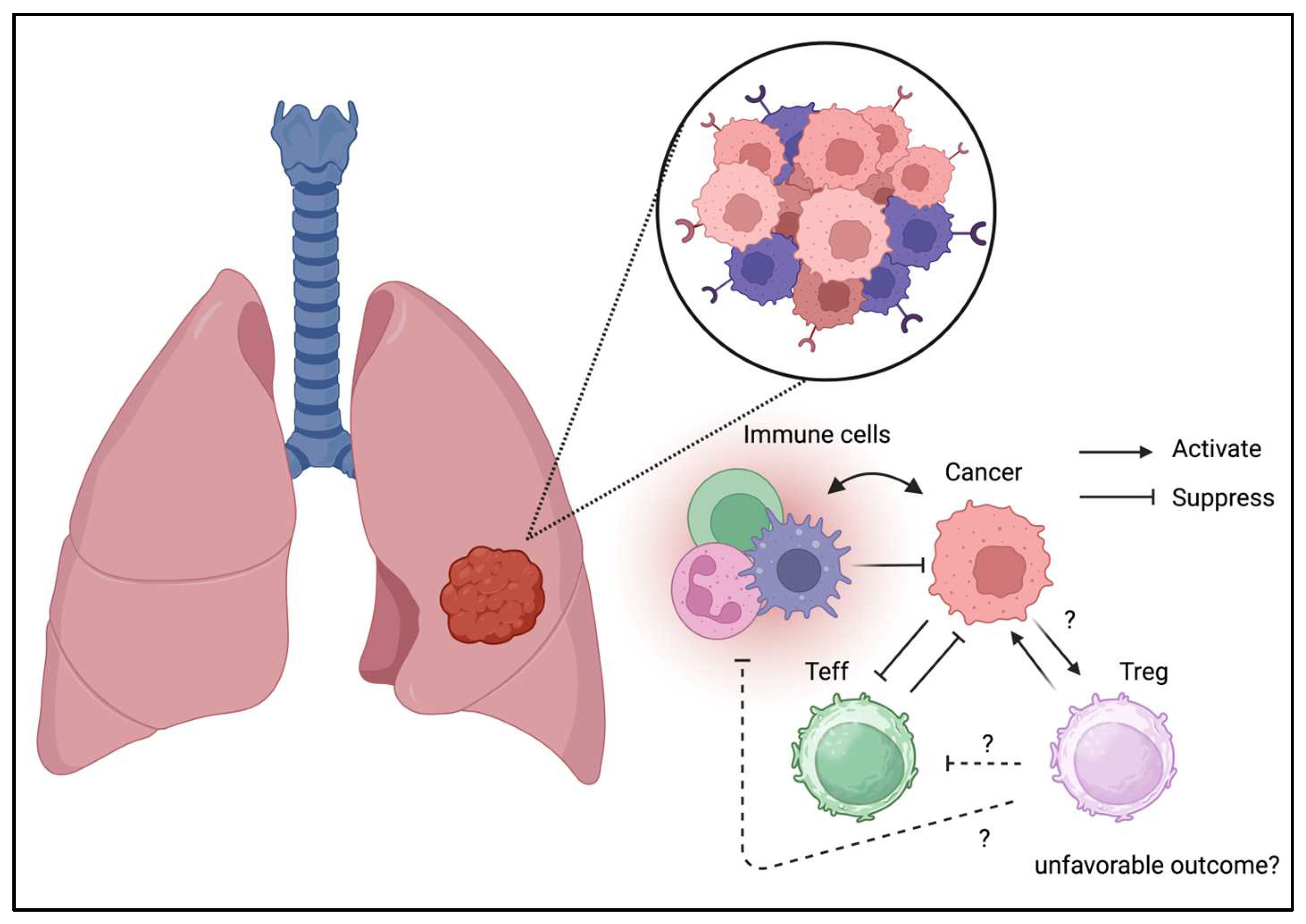

3.2. Lung Cancer

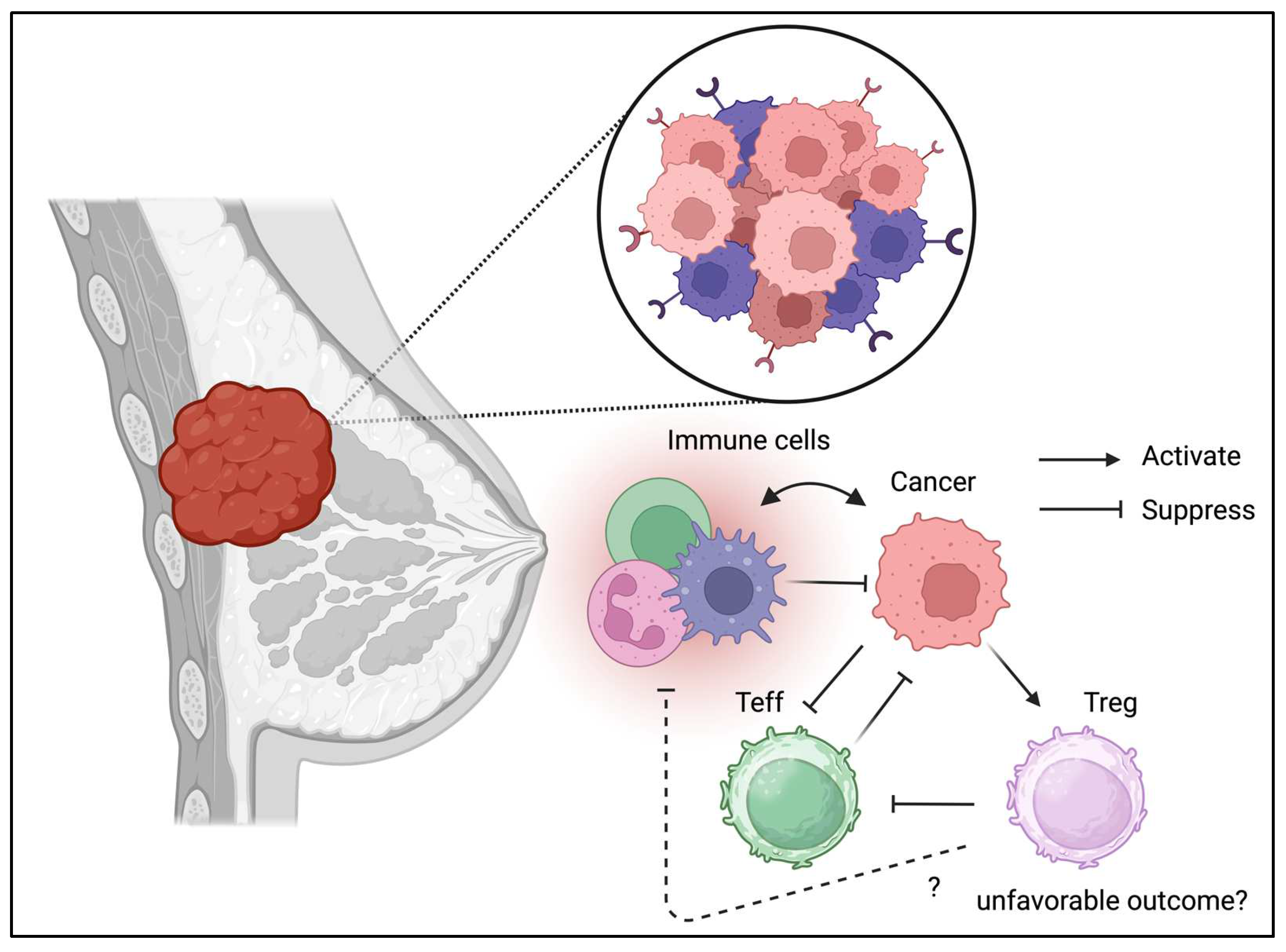

3.3. Breast Cancer

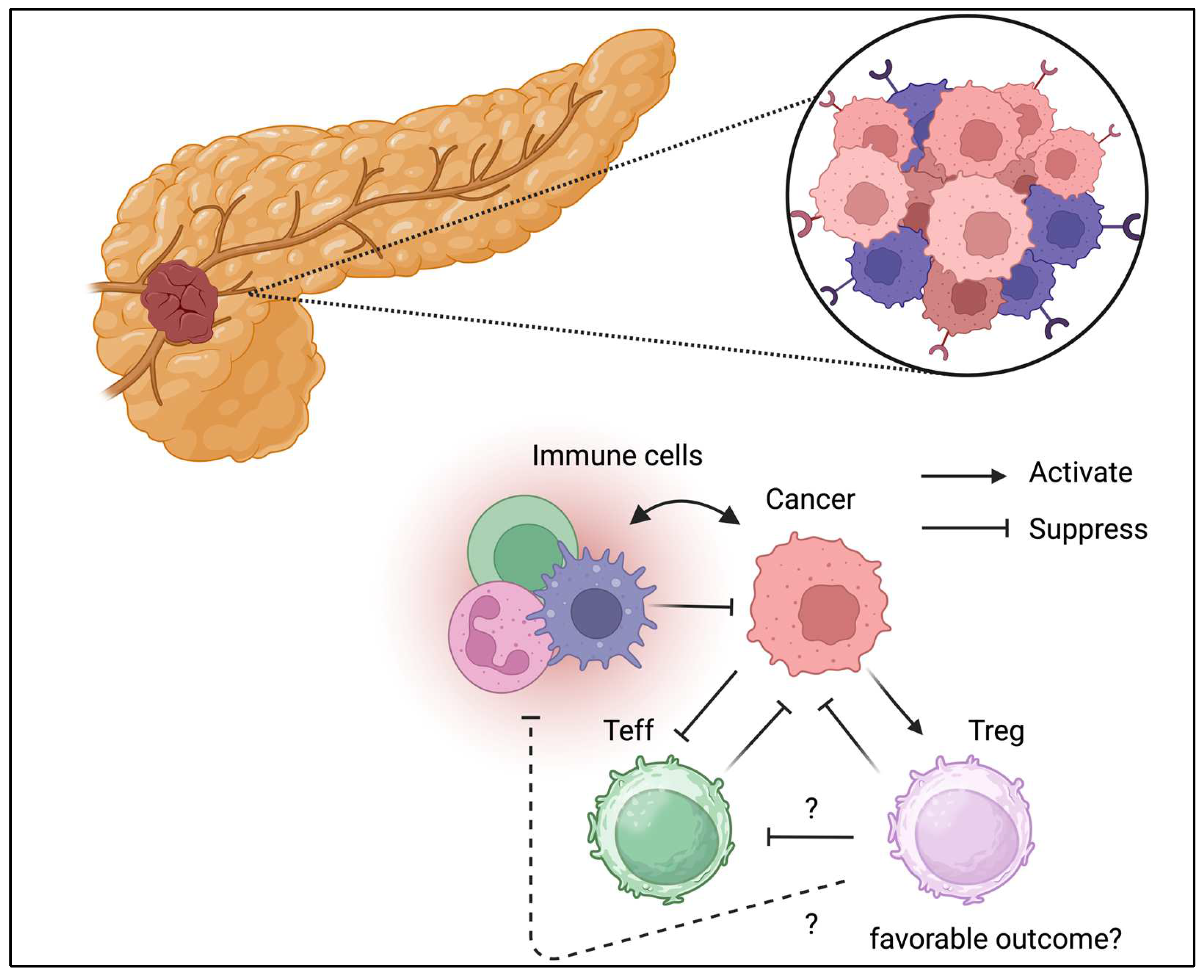

3.4. Pancreatic Cancer

3.5. Hepatocellular Carcinoma

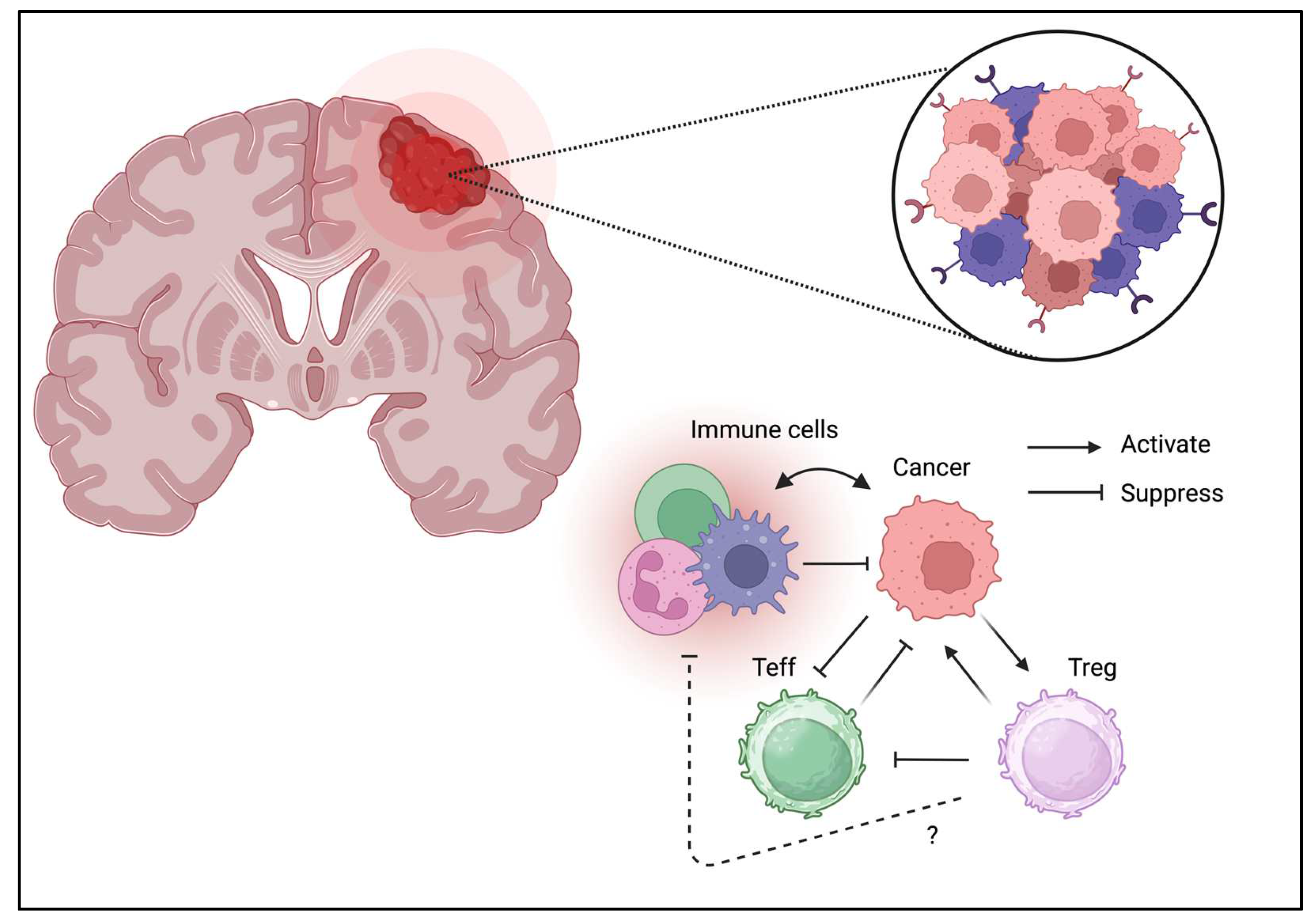

3.6. Brain Tumor

3.7. Melanoma

3.8. Kidney and Urinary Tract Cancer

3.9. Gynecological Cancer

3.10. Head and Neck Cancer

3.11. Soft Tissue Sarcoma

3.12. Leukemia/Lymphoma

4. Therapeutic Approach Targeting Treg in TME

4.1. Antibody Drug Conjugate

4.2. Immunotoxin

4.3. Peptide

5. Future Investigations for Targeting Treg in TME

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, N.M.; Simon, M.C. The tumor microenvironment. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R921–R925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldo, N.A.; Sanchez-Salas, R.; Peske, J.D.; Vano, Y.; Becht, E.; Petitprez, F.; Validire, P.; Ingels, A.; Cathelineau, X.; Fridman, W.H.; et al. The clinical role of the TME in solid cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 120, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, S.; Milo, T.; Isaacson, A.; Halperin, C.; Miyara, S.; Stein, Y.; Lior, C.; Pevsner-Fischer, M.; Tzahor, E.; Mayo, A.; et al. The tumor microenvironment shows a hierarchy of cell-cell interactions dominated by fibroblasts. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnaik, A.A.; Hwu, P.; Mule, J.J.; Pilon-Thomas, S. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes: A new hope. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 1315–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Cui, J.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. The prognostic and biology of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in the immunotherapy of cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 129, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bied, M.; Ho, W.W.; Ginhoux, F.; Bleriot, C. Roles of macrophages in tumor development: a spatiotemporal perspective. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.I.; Farber, D.L. Tissue-Resident Immune Cells in Humans. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 40, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, C.; Tanaka, A.; Sakaguchi, S. Tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells as targets of cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Leun, A.M.; Traets, J.J.H.; Vos, J.L.; Elbers, J.B.W.; Patiwael, S.; Qiao, X.; Machuca-Ostos, M.; Thommen, D.S.; Haanen, J.; Schumacher, T.N.M.; et al. Dual Immune Checkpoint Blockade Induces Analogous Alterations in the Dysfunctional CD8+ T-cell and Activated Treg Compartment. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 2212–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewski, T.F.; Schreiber, H.; Fu, Y.X. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neophytou, C.M.; Panagi, M.; Stylianopoulos, T.; Papageorgis, P. The Role of Tumor Microenvironment in Cancer Metastasis: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huppert, L.A.; Green, M.D.; Kim, L.; Chow, C.; Leyfman, Y.; Daud, A.I.; Lee, J.C. Tissue-specific Tregs in cancer metastasis: opportunities for precision immunotherapy. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejarano, L.; Jordao, M.J.C.; Joyce, J.A. Therapeutic Targeting of the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 933–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Q.; Wang, A.; Yuan, Y.; Zhu, B.; Long, H. Heterogeneity of the tumor immune microenvironment and its clinical relevance. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudensky, A.Y. Regulatory T cells and Foxp3. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 241, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hori, S.; Nomura, T.; Sakaguchi, S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science 2003, 299, 1057–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenot, J.D.; Gavin, M.A.; Rudensky, A.Y. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003, 4, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, S.F. FOXP3: of mice and men. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 24, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y. Forkhead Box Protein P3 in the Immune System. Allergies 2025, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, S.; Sakaguchi, N.; Asano, M.; Itoh, M.; Toda, M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 1995, 155, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Putnam, A.L.; Xu-Yu, Z.; Szot, G.L.; Lee, M.R.; Zhu, S.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Kapranov, P.; Gingeras, T.R.; Fazekas de St Groth, B.; et al. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 1701–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Perea, A.L.; Arcia, E.D.; Rueda, C.M.; Velilla, P.A. Phenotypical characterization of regulatory T cells in humans and rodents. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2016, 185, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benamar, M.; Chen, Q.; Wang, M.; Chan, T.M.F.; Chatila, T.A. CPHEN-016: Comprehensive phenotyping of human regulatory T cells. Cytom. A 2022, 101, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collison, L.W.; Vignali, D.A. In vitro Treg suppression assays. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 707, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurchy, A.N.; Levings, M.K. Suppression assays with human T regulatory cells: a technical guide. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012, 42, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeppli, R.E.; Wu, D.; Cook, L.; Levings, M.K. The environment of regulatory T cell biology: cytokines, metabolites, and the microbiome. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, F.; Colamatteo, A.; La Rocca, C.; Lepore, M.T.; Russo, C.; De Rosa, G.; Matarese, A.; Procaccini, C.; Matarese, G. Metabolic Plasticity of Regulatory T Cells in Health and Autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 2024, 212, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colamatteo, A.; Carbone, F.; Bruzzaniti, S.; Galgani, M.; Fusco, C.; Maniscalco, G.T.; Di Rella, F.; de Candia, P.; De Rosa, V. Molecular Mechanisms Controlling Foxp3 Expression in Health and Autoimmunity: From Epigenetic to Post-translational Regulation. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, R.; Zhou, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, L.; Liang, T.; Shi, L.; Long, J.; Yuan, D. Regulatory T Cell Plasticity and Stability and Autoimmune Diseases. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 58, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doganci, A.; Eigenbrod, T.; Krug, N.; De Sanctis, G.T.; Hausding, M.; Erpenbeck, V.J.; Haddad el, B.; Lehr, H.A.; Schmitt, E.; Bopp, T.; et al. The IL-6R alpha chain controls lung CD4+CD25+ Treg development and function during allergic airway inflammation in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 2005, 115, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zeebroeck, L.; Arroyo Hornero, R.; Corte-Real, B.F.; Hamad, I.; Meissner, T.B.; Kleinewietfeld, M. Fast and Efficient Genome Editing of Human FOXP3(+) Regulatory T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 655122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.K.; Mukasa, R.; Hatton, R.D.; Weaver, C.T. Developmental plasticity of Th17 and Treg cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2009, 21, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Wan, Y.Y. Intricacies of TGF-beta signaling in Treg and Th17 cell biology. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 1002–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinewietfeld, M.; Hafler, D.A. The plasticity of human Treg and Th17 cells and its role in autoimmunity. Semin. Immunol. 2013, 25, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemmour, D.; Zilionis, R.; Kiner, E.; Klein, A.M.; Mathis, D.; Benoist, C. Single-cell gene expression reveals a landscape of regulatory T cell phenotypes shaped by the TCR. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, B.; Niu, Q.; Su, X.; Bai, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, C.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis reveals disparate effector differentiation pathways in human T(reg) compartment. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, P.P.; Cho, I.; Ali, N. Tissue regulatory T cells. Immunology 2020, 161, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.V.; Ma, W.; Miron, M.; Granot, T.; Guyer, R.S.; Carpenter, D.J.; Senda, T.; Sun, X.; Ho, S.H.; Lerner, H.; et al. Human Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells Are Defined by Core Transcriptional and Functional Signatures in Lymphoid and Mucosal Sites. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 2921–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzolla, A.; Nguyen, T.H.O.; Smith, J.M.; Brooks, A.G.; Kedzieska, K.; Heath, W.R.; Reading, P.C.; Wakim, L.M. Resident memory CD8(+) T cells in the upper respiratory tract prevent pulmonary influenza virus infection. Sci. Immunol. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.Z.M.; Wakim, L.M. Tissue resident memory T cells in the respiratory tract. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delacher, M.; Simon, M.; Sanderink, L.; Hotz-Wagenblatt, A.; Wuttke, M.; Schambeck, K.; Schmidleithner, L.; Bittner, S.; Pant, A.; Ritter, U.; et al. Single-cell chromatin accessibility landscape identifies tissue repair program in human regulatory T cells. Immunity 2021, 54, 702–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewavisenti, R.V.; Ferguson, A.L.; Gasparini, G.; Ohashi, T.; Braun, A.; Watkins, T.S.; Miles, J.J.; Elliott, M.; Sierro, F.; Feng, C.G.; et al. Tissue-resident regulatory T cells accumulate at human barrier lymphoid organs. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2021, 99, 894–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, O.T.; Bricard, O.; Tareen, S.; Gergelits, V.; Andrews, S.; Biggins, L.; Roca, C.P.; Whyte, C.; Junius, S.; Brajic, A.; et al. The tissue-resident regulatory T cell pool is shaped by transient multi-tissue migration and a conserved residency program. Immunity 2024, 57, 1586–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olguin, J.E.; Medina-Andrade, I.; Rodriguez, T.; Rodriguez-Sosa, M.; Terrazas, L.I. Relevance of Regulatory T Cells during Colorectal Cancer Development. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeponik, L.; Ahlmanner, F.; Sundstrom, P.; Rodin, W.; Gustavsson, B.; Bexe Lindskog, E.; Wettergren, Y.; Quiding-Jarbrink, M. Intratumoral regulatory T cells from colon cancer patients comprise several activated effector populations. BMC Immunol. 2021, 22, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; He, J.; Shirota, H.; Trivett, A.L.; Yang, D.; Klinman, D.M.; Oppenheim, J.J.; Chen, X. Blockade of TNFR2 signaling enhances the immunotherapeutic effect of CpG ODN in a mouse model of colon cancer. Sci. Signal 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastille, E.; Bardini, K.; Fleissner, D.; Adamczyk, A.; Frede, A.; Wadwa, M.; von Smolinski, D.; Kasper, S.; Sparwasser, T.; Gruber, A.D.; et al. Transient ablation of regulatory T cells improves antitumor immunity in colitis-associated colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 4258–4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aristin Revilla, S.; Kranenburg, O.; Coffer, P.J. Colorectal Cancer-Infiltrating Regulatory T Cells: Functional Heterogeneity, Metabolic Adaptation, and Therapeutic Targeting. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 903564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Nishikawa, H.; Wada, H.; Nagano, Y.; Sugiyama, D.; Atarashi, K.; Maeda, Y.; Hamaguchi, M.; Ohkura, N.; Sato, E.; et al. Two FOXP3(+)CD4(+) T cell subpopulations distinctly control the prognosis of colorectal cancers. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, W.; Lin, H. Regulatory T cell and macrophage crosstalk in acute lung injury: future perspectives. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovisic, M.; Mambetsariev, N.; Singer, B.D.; Morales-Nebreda, L. Differential roles of regulatory T cells in acute respiratory infections. J. Clin. Invest. 2023, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Bi, G.; Shan, G.; Jin, X.; Bian, Y.; Wang, Q. Tumor-Associated Regulatory T Cells in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Current Advances and Future Perspectives. J. Immunol. Res. 2022, 2022, 4355386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykema, A.G.; Zhang, J.; Cheung, L.S.; Connor, S.; Zhang, B.; Zeng, Z.; Cherry, C.M.; Li, T.; Caushi, J.X.; Nishimoto, M.; et al. Lung tumor-infiltrating T(reg) have divergent transcriptional profiles and function linked to checkpoint blockade response. Sci. Immunol. 2023, 8, eadg1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Nakata, M.; Hirami, Y.; Yukawa, T.; Maeda, A.; Tanemoto, K. Tumor-infiltrating Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are correlated with cyclooxygenase-2 expression and are associated with recurrence in resected non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010, 5, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, H.; Tang, Z.; Shi, J.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, C.; Li, X.; Zhou, C. Selective depletion of CCR8+Treg cells enhances anti-tumor immunity of cytotoxic T cells in lung cancer via dendritic cells. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeNardo, D.G.; Coussens, L.M. Inflammation and breast cancer. Balancing immune response: crosstalk between adaptive and innate immune cells during breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res. 2007, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plitas, G.; Konopacki, C.; Wu, K.; Bos, P.D.; Morrow, M.; Putintseva, E.V.; Chudakov, D.M.; Rudensky, A.Y. Regulatory T Cells Exhibit Distinct Features in Human Breast Cancer. Immunity 2016, 45, 1122–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debien, V.; De Caluwe, A.; Wang, X.; Piccart-Gebhart, M.; Tuohy, V.K.; Romano, E.; Buisseret, L. Immunotherapy in breast cancer: an overview of current strategies and perspectives. NPJ Breast Cancer 2023, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kos, K.; de Visser, K.E. The Multifaceted Role of Regulatory T Cells in Breast Cancer. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol. 2021, 5, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Simons, D.L.; Lu, X.; Tu, T.Y.; Solomon, S.; Wang, R.; Rosario, A.; Avalos, C.; Schmolze, D.; Yim, J.; et al. Connecting blood and intratumoral T(reg) cell activity in predicting future relapse in breast cancer. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, P.D.; Plitas, G.; Rudra, D.; Lee, S.Y.; Rudensky, A.Y. Transient regulatory T cell ablation deters oncogene-driven breast cancer and enhances radiotherapy. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 2435–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.M.; Martinez, L.M.; Murdock, S.; deLigio, J.T.; Olex, A.L.; Effi, C.; Dozmorov, M.G.; Bos, P.D. Regulatory T Cells Support Breast Cancer Progression by Opposing IFN-gamma-Dependent Functional Reprogramming of Myeloid Cells. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Xue, J.; Jaffee, E.M.; Habtezion, A. Role of immune cells and immune-based therapies in pancreatitis and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 1230–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, A. Autoreactive T cells in type 1 diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 2017, 127, 2881–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, A.; Socci, C.; Stabilini, A.; Valle, A.; Monti, P.; Piemonti, L.; Nano, R.; Olek, S.; Maffi, P.; Scavini, M.; et al. Expansion of Th17 cells and functional defects in T regulatory cells are key features of the pancreatic lymph nodes in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2011, 60, 2903–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C.M.; Peakman, M.; Tree, T.I.M. Regulatory T cell dysfunction in type 1 diabetes: what’s broken and how can we fix it? Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1839–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonkin, D.R.; Haskins, K. Regulatory T cells enter the pancreas during suppression of type 1 diabetes and inhibit effector T cells and macrophages in a TGF-beta-dependent manner. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 39, 1313–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluestone, J.A.; Buckner, J.H.; Fitch, M.; Gitelman, S.E.; Gupta, S.; Hellerstein, M.K.; Herold, K.C.; Lares, A.; Lee, M.R.; Li, K.; et al. Type 1 diabetes immunotherapy using polyclonal regulatory T cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 315ra189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, N.A.; Burchard, P.R.; Dunne, R.F.; Linehan, D.C. Immunologic Strategies in Pancreatic Cancer: Making Cold Tumors Hot. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2789–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, L.H.; Pauklin, S. Pancreatic Cancer Microenvironment and Cellular Composition: Current Understandings and Therapeutic Approaches. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.J.; Jaffee, E.M.; Zheng, L. The tumour microenvironment in pancreatic cancer—clinical challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota Reyes, C.; Demir, E.; Cifcibasi, K.; Istvanffy, R.; Friess, H.; Demir, I.E. Regulatory T Cells in Pancreatic Cancer: Of Mice and Men. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lazarus, J.; Steele, N.G.; Yan, W.; Lee, H.J.; Nwosu, Z.C.; Halbrook, C.J.; Menjivar, R.E.; Kemp, S.B.; Sirihorachai, V.R.; et al. Regulatory T-cell Depletion Alters the Tumor Microenvironment and Accelerates Pancreatic Carcinogenesis. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhangnia, P.; Khorramdelazad, H.; Nickho, H.; Delbandi, A.A. Current and future immunotherapeutic approaches in pancreatic cancer treatment. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.W.; Harmon, C.; O’Farrelly, C. Liver immunology and its role in inflammation and homeostasis. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2016, 13, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; He, X.; Qu, M.; Xu, G.; Wang, H.; Huang, M.; Pan, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals the heterogeneity of liver-resident immune cells in human. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli, B.; Mieli-Vergani, G.; Vergani, D. Autoimmmune hepatitis. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, E.C.; Sung, P.S.; Park, S.H. Immune responses and immunopathology in acute and chronic viral hepatitis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.J.; Qian, Q.F.; Zhou, J.R.; Sun, D.L.; Duan, Y.F.; Zhu, X.; Sartorius, K.; Lu, Y.J. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) in liver fibrosis. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sas, Z.; Cendrowicz, E.; Weinhauser, I.; Rygiel, T.P. Tumor Microenvironment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Challenges and Opportunities for New Treatment Options. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Feng, W.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Nie, Y.; Fan, D.; Wu, K.; et al. Immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the progression, metastasis, and therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: from bench to bedside. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y. Impact of regulatory T cells on the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: A protocol for systematic review and meta analysis. Med. (Baltim. ) 2021, 100, e23957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.K.; Shin, E.C. Regulatory T Cells in Hepatitis B and C Virus Infections. Immune Netw. 2016, 16, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, G.; Croese, T.; Peralta Ramos, J.M.; Schwartz, M. Transforming the understanding of brain immunity. Science 2023, 380, eabo7649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, M.; Komai, K.; Mise-Omata, S.; Iizuka-Koga, M.; Noguchi, Y.; Kondo, T.; Sakai, R.; Matsuo, K.; Nakayama, T.; Yoshie, O.; et al. Brain regulatory T cells suppress astrogliosis and potentiate neurological recovery. Nature 2019, 565, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.F.; Idema, A.J.; Bol, K.F.; Grotenhuis, J.A.; de Vries, I.J.; Wesseling, P.; Adema, G.J. Prognostic significance and mechanism of Treg infiltration in human brain tumors. J. Neuroimmunol. 2010, 225, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.F.; Idema, A.J.; Bol, K.F.; Nierkens, S.; Grauer, O.M.; Wesseling, P.; Grotenhuis, J.A.; Hoogerbrugge, P.M.; de Vries, I.J.; Adema, G.J. Regulatory T cells and the PD-L1/PD-1 pathway mediate immune suppression in malignant human brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2009, 11, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, D.A.; Dey, M.; Chang, A.; Lesniak, M.S. Targeting Tregs in Malignant Brain Cancer: Overcoming IDO. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoozgar, Z.; Kloepper, J.; Ren, J.; Tay, R.E.; Kazer, S.W.; Kiner, E.; Krishnan, S.; Posada, J.M.; Ghosh, M.; Mamessier, E.; et al. Targeting Treg cells with GITR activation alleviates resistance to immunotherapy in murine glioblastomas. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Matte-Martone, C.; Gonzalez, D.G.; Lathrop, E.A.; May, D.P.; Pineda, C.M.; Moore, J.L.; Boucher, J.D.; Marsh, E.; Schmitter-Sanchez, A.; et al. Skin-resident immune cells actively coordinate their distribution with epidermal cells during homeostasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Rosenblum, M.D. Regulatory T cells in skin. Immunology 2017, 152, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Kim, S.H.; Che, L.; Park, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, T.G. Foxp3(+) Treg control allergic skin inflammation by restricting IFN-gamma-driven neutrophilic infiltration and NETosis. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2024, 115, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, I.; Conciatori, F.; Bazzichetto, C.; Ferretti, G.; Cognetti, F.; Ciuffreda, L.; Milella, M. Tumor Microenvironment: Implications in Melanoma Resistance to Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Guo, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Ou, L.; Xu, X. Targeting regulatory T cells for immunotherapy in melanoma. Mol. Biomed. 2021, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, A.C.; Zappasodi, R. A decade of checkpoint blockade immunotherapy in melanoma: understanding the molecular basis for immune sensitivity and resistance. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geels, S.N.; Moshensky, A.; Sousa, R.S.; Murat, C.; Bustos, M.A.; Walker, B.L.; Singh, R.; Harbour, S.N.; Gutierrez, G.; Hwang, M.; et al. Interruption of the intratumor CD8(+) T cell:Treg crosstalk improves the efficacy of PD-1 immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 1051–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, M.; Lacerda Mariano, L.; Canton, T.; Ingersoll, M.A. Tissue-resident memory T cells mediate mucosal immunity to recurrent urinary tract infection. Sci. Immunol. 2023, 8, eabn4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, I.; Pircher, A.; Pichler, R. Targeting the Tumor Microenvironment in Renal Cell Cancer Biology and Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatogai, K.; Sweis, R.F. The Tumor Microenvironment of Bladder Cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1296, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koll, F.J.; Banek, S.; Kluth, L.; Kollermann, J.; Bankov, K.; Chun, F.K.; Wild, P.J.; Weigert, A.; Reis, H. Tumor-associated macrophages and Tregs influence and represent immune cell infiltration of muscle-invasive bladder cancer and predict prognosis. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.S.; Weil, R.; Dovey, Z.; Davis, A.; Tewari, A.K. The Tumor Microenvironment and Immunotherapy in Prostate and Bladder Cancer. Urol. Clin. North. Am. 2020, 47, e17–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, S.; Murakami, K.; Inoue, A.; Yonezawa, T.; Matsuki, N. CCR4 Blockade Depletes Regulatory T Cells and Prolongs Survival in a Canine Model of Bladder Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019, 7, 1175–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santagata, S.; Rea, G.; Bello, A.M.; Capiluongo, A.; Napolitano, M.; Desicato, S.; Fragale, A.; D’Alterio, C.; Trotta, A.M.; Ierano, C.; et al. Targeting CXCR4 impaired T regulatory function through PTEN in renal cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 130, 2016–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzen, D.; Arck, P.C.; Thiele, K. Tissue-resident immunity in the female and male reproductive tract. Semin. Immunopathol. 2022, 44, 785–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, G.; Cardenas, I. The immune system in pregnancy: a unique complexity. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2010, 63, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, V. Sex Hormones Determine Immune Response. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhao, X.; Wei, X. Tumor Microenvironment in Ovarian Cancer: Function and Therapeutic Strategy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, P.; Ramisetty, S.K.; Raghu Subbalakshmi, A.; Krishna, B.M.; Pareek, S.; Mohanty, A.; Kulkarni, P.; Horne, D.; Salgia, R.; Singhal, S.S. Gynecological cancer tumor Microenvironment: Unveiling cellular complexity and therapeutic potential. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 229, 116498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Ke, X.; Zeng, S.; Wu, M.; Lou, J.; Wu, L.; Huang, P.; Huang, L.; Wang, F.; Pan, S. Analysis of CD8+ Treg cells in patients with ovarian cancer: a possible mechanism for immune impairment. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2015, 12, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynam, S.; Lugade, A.A.; Odunsi, K. Immunotherapy for Gynecologic Cancer: Current Applications and Future Directions. Clin. Obs. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 63, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, R.; Senbabaoglu, Y.; Desrichard, A.; Havel, J.J.; Dalin, M.G.; Riaz, N.; Lee, K.W.; Ganly, I.; Hakimi, A.A.; Chan, T.A.; et al. The head and neck cancer immune landscape and its immunotherapeutic implications. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e89829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, M.; Corte, C.M.D.; Liello, R.D.; Viscardi, G.; Sparano, F.; Iacovino, M.L.; Paragliola, F.; Piccolo, A.; Napolitano, S.; Martini, G.; et al. Immunotherapy for head and neck cancer: Present and future. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2022, 174, 103679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seminerio, I.; Descamps, G.; Dupont, S.; de Marrez, L.; Laigle, J.A.; Lechien, J.R.; Kindt, N.; Journe, F.; Saussez, S. Infiltration of FoxP3+ Regulatory T Cells is a Strong and Independent Prognostic Factor in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihara, F.; Sakurai, D.; Horinaka, A.; Makita, Y.; Fujikawa, A.; Sakurai, T.; Yamasaki, K.; Kunii, N.; Motohashi, S.; Nakayama, T.; et al. CD45RA(-)Foxp3(high) regulatory T cells have a negative impact on the clinical outcome of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2017, 66, 1275–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolle, M.A.; Herbsthofer, L.; Granegger, B.; Goda, M.; Brcic, I.; Bergovec, M.; Scheipl, S.; Prietl, B.; Pichler, M.; Gerger, A.; et al. T-regulatory cells predict clinical outcome in soft tissue sarcoma patients: a clinico-pathological study. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazel, M.; Dufresne, A.; Vanacker, H.; Waissi, W.; Blay, J.Y.; Brahmi, M. Immunotherapy for Soft Tissue Sarcomas: Anti-PD1/PDL1 and Beyond. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.S.; Sousa, L.M.; Couceiro, P.; Andrade, T.F.; Alves, V.; Martinho, A.; Rodrigues, J.; Fonseca, R.; Freitas-Tavares, P.; Santos-Rosa, M.; et al. Peripheral immune profiling of soft tissue sarcoma: perspectives for disease monitoring. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1391840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Dominguez, D.J.; Hontecillas-Prieto, L.; Palazon-Carrion, N.; Jimenez-Cortegana, C.; Sanchez-Margalet, V.; de la Cruz-Merino, L. Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Lymphoma: Focus on Epigenetics. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.W.; Gascoyne, R.D. The tumour microenvironment in B cell lymphomas. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustun, C.; Miller, J.S.; Munn, D.H.; Weisdorf, D.J.; Blazar, B.R. Regulatory T cells in acute myelogenous leukemia: is it time for immunomodulation? Blood 2011, 118, 5084–5095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Mou, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Rao, Q.; Xing, H.; Tian, Z.; Tang, K.; Wang, M.; Wang, J. Regulatory T cells promote the stemness of leukemia stem cells through IL10 cytokine-related signaling pathway. Leukemia 2022, 36, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutis, T.; van Rijn, R.S.; Simonetti, E.R.; Aarts-Riemens, T.; Emmelot, M.E.; van Bloois, L.; Martens, A.; Verdonck, L.F.; Ebeling, S.B. Human regulatory T cells control xenogeneic graft-versus-host disease induced by autologous T cells in RAG2-/-gammac-/- immunodeficient mice. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 5520–5525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinado, A.C.; Calvo, I.A.; Cenzano, I.; Olaverri, D.; Cocera, M.; San Martin-Uriz, P.; Romero, J.P.; Vilas-Zornoza, A.; Vera, L.; Gomez-Cebrian, N.; et al. The bone marrow niche regulates redox and energy balance in MLL::AF9 leukemia stem cells. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1969–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, K.; Zhang, H. Targeting Leukemia-Initiating Cells and Leukemic Niches: The Next Therapy Station for T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia? Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Liu, C.; Yang, K.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yu, K.; Wang, L.; Ran, L.; Chen, M.; et al. Aged hematopoietic stem cells entrap regulatory T cells to create a prosurvival microenvironment. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 1216–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riether, C. Regulation of hematopoietic and leukemia stem cells by regulatory T cells. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1049301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, F.; Somasundaram, A.; Bruno, T.C.; Workman, C.J.; Vignali, D.A.A. Therapeutic targeting of regulatory T cells in cancer. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 944–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Koyama, S. Mechanisms of regulatory T cell infiltration in tumors: implications for innovative immune precision therapies. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Bae, H. Drug conjugates for targeting regulatory T cells in the tumor microenvironment: guided missiles for cancer treatment. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1996–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Y. Antibody drug conjugate: the “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneziani, A.C.; Sneha, S.; Oza, A.M. Antibody-Drug Conjugates: Advancing from Magic Bullet to Biological Missile. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 1434–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zammarchi, F.; Havenith, K.; Bertelli, F.; Vijayakrishnan, B.; Chivers, S.; van Berkel, P.H. CD25-targeted antibody-drug conjugate depletes regulatory T cells and eliminates established syngeneic tumors via antitumor immunity. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litzinger, M.T.; Fernando, R.; Curiel, T.J.; Grosenbach, D.W.; Schlom, J.; Palena, C. IL-2 immunotoxin denileukin diftitox reduces regulatory T cells and enhances vaccine-mediated T-cell immunity. Blood 2007, 110, 3192–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onda, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Pastan, I. Depletion of regulatory T cells in tumors with an anti-CD25 immunotoxin induces CD8 T cell-mediated systemic antitumor immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2019, 116, 4575–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, T.; Soldevilla, M.M.; Casares, N.; Villanueva, H.; Bendandi, M.; Lasarte, J.J.; Pastor, F. Targeting inhibition of Foxp3 by a CD28 2′-Fluro oligonucleotide aptamer conjugated to P60-peptide enhances active cancer immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2016, 91, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, A.; Casares, N.; Troconiz, I.F.; Lozano, T.; Lasarte, J.J.; Zalba, S.; Garrido, M.J. Foxp3 inhibitory peptide encapsulated in a novel CD25-targeted nanoliposome promotes efficient tumor regression in mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2025, 46, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).