1. Introduction

The concept of biofilms describes structured aggregates of microbial communities, coated in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substances comprised of extracellular DNA, polysaccharides, lipids, and proteins [

1]. Such aggregates may appear as flocs in liquids or as slimy films, easily formed on wetted, inert or living surfaces. They are assumed to be the predominant from of microbial life driving all major biogeochemical processes [

2]. It is also understood that many biofilms form and/or expand due to exposure to external environmental clues, such as nutrient deficiency or excess, osmotic pressure, pH, oxidative stress, and antimicrobial agents [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Biofilms may consist of single or multiple species, confer many advantages on their inhabitants and represent a much higher level of organization than single cells do.

Microbes have the capacity to attach to any given surface, especially if organic material had previously been deposited on it, such as carbohydrates, lipids, minerals and/or calcium soaps, as is the case in industrial systems using water-miscible metalworking fluids (MWFs) [

8]. MWFs are widely applied in metal removal and forming operations, dissipating heat and reducing friction. Three main categories of MWFs are utilized: emulsifiable oils, semisynthetics and synthetics; all are formulated and sold as concentrates, containing anything from 10 to 20 organic ingredients. They are mixed at the end-user’s site with water that subsequently accounts for 85 % to 95 % of the mixture [

9]. The main components of MWF-concentrates are mineral and ester oil, polyalphaolifins or glycols. Emulsifiers, corrosion inhibitors, foam control agents and lubricity enhancers are added as needed to enhance performance, stability and functionality. Moreover, biocidal and biostatic components are added to some MWF formulations as they are thought to keep microbiological agents under control [

10]. However, regulatory pressure leading to significant restrictions on permitted concentrations is increasing, a trend that is expected to continue [

11]. Basically, the range of potential components has narrowed down to isothiazolinones [

8]: 2-methyl-2H-isothiazol-3-one (MIT), 1,2-benzisothiazol-3(2H)-one (BIT), and 5-chloro-2-methyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one (CMIT). The latter is mainly used as a tank-side additive, whereas the MIT and BIT are also used for in-drum conservation. Still, the high ratio of water and the evenly mixed-in organic components, aerated by recirculation, provide an appropriate base of life for planktonic bacteria, fungi and archaea in all types of in-use, as well as spent MWFs [

8,

12,

13,

14]. Significant, however, are the additional habitats on (machine) surfaces, which are wetted by contact with the coolant through flow, splashing, evaporation and misting: Lines that supply and discharge the MWF from the site of action offer dozens of square meters of microbial settlement area. This is a considerable problem with single-filled machines, getting multiplied in centralized systems where the fluid is transported over long distances to and from many machining centers [

15]. As in any aqueous system, biofilms are of far greater importance than their planktonic relatives, being the main cause for biofouling and microbiologically influenced corrosion [

16,

17,

18].

Although biofilms in MWFs is a topic that receives a lot of attention in the industry [

19], it is poorly documented in the published literature. Trafny and colleagues reported that the tetrazolium salt assay (MTT assay) could be efficiently used to assess the biofilm-forming capacity [

20] and that biocides contained into the MWF formulation did not contribute to biofilm formation or control [

21]. Other researchers found that NH

4Cl and KH

2PO

4 negatively affect biofilm formation in MWFs when either present in excess or completely absent [

22]. Finally, it was published that biofilms in MWFs were measurably reduced by successfully interfering with quorum sensing [

23,

24].

In this study, we report that bactericidal or bacteriostatic elements, as well as a mineral oil based and synthetic MWF, respectively, blocked de novo biofilm formation but had largely negligible effects on established biofilms. Under some conditions, even biofilm growth was detected. However, depending on the type, MWFs had detectable impact on the composition of the biofilm population, a process that is not yet understood. Moreover, we could show that biofilm populations developed capabilities that their planktonic relatives did not display, namely the ability to downgrade an amine that was toxic to them.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Species

P. oleovorans, P. aeruginosa and M. morganii strains employed in all experiments were isolated from in-use MWF samples by standard heterotrophic plate count methods performed on Tryptone Soya Agar (TSA) prepared in-house (Oxoid CM0131, Thermo Fisher, Pratteln, Switzerland) at 40 g L-1. Incubation was done at 35°C for 2 to 3 days. Isolated bacterial species were subsequently identified by Maldi-TOF MS analysis of protein patterns at Mabritec AG (Riehen, Switzerland).

2.2. Biocides

For all experiments, technical standard biocides (bactericides to kill bacteria and fungicides to kill fungi) from industrial suppliers were used – the concentration indicated refers to a typical dose in a freshly prepared, 5% (w/w) in-use MWF: MIT (Acticide® M 50; Thor GmbH, Speyer, Germany; Active ingredient content: 50%) at a concentration of 100 ppm, BIT (PREVENTOL® BIT 20 N; Lanxess Deutschland GmbH, Leverkusen, Germany; Active ingredient content: 20%) at a concentration of 150 ppm, 2-n-octyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one (OIT; BIOBANTM O 45; Lanxess Deutschland GmbH, Leverkusen, Germany; Active ingredient content: 45%) at a concentration of 50 ppm.

2.3. Metalworking Fluids

The described Experiments were performed using two commercially available MWFs from Blaser Swisslube AG (Hasle-Rüegsau, Switzerland): The mineral oil based, amine-free Blasocut 2000 CF (MWF M; Art. No. 00875-12), and the synthetic, amine-containing Grindex 10 CO (MWF S; Art. No 01100-05). Both fluids were used in the formulation sold in 2023. Neither of the two concentrates contained listed bactericides [

25].

For alkanolamine-assays described in chapter 2.7, MWF M was supplemented with 5% (w/w) 1-aminopropan-2-ol (MIPA; DOW Europe GmbH, Horgen, Switzerland) and 5% (w/w) 2,2′,2′′-Nitrilotri(ethan-1-ol) (TEA; DOW Europe GmbH, Horgen, Switzerland). Accordingly, the mineral oil content was reduced by 10% (w/w).

To prepare a 5% (w/w) working fluid, 47.5 g of sterile tap water was added to a sterile 100 mL-beaker containing a sterile stirring bar before adding 2.5 g of concentrate. The mixture was stirred at 500 rpm for at least 30 min.

2.4. Mini ‘Microbial Evolution and Growth Arena’ (MEGA) Experiments

TSA plates were prepared as described above, but shortly before solidifying, different concentrations of MIT (0, 100 ppm, 500 ppm, 2500 ppm), BIT (0, 150 ppm, 300 ppm, 600 ppm), MIPA (0, 0.15%, 0.3%, 0.6%) or TEA (0, 0.15%, 0.3%, 0.6%) were added and evenly mixed in. Plates were left to cool completely before being cut into quarters and being reassembled. The plate was subsequently covered with a thin layer of agar-agar (#1.1614, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at 0.3 % [w/w] and allowed to cool for another hour. At the beginning of the experiment, M. morganii was suspended in 0.9 % NaCl at an OD600 of 0.2 and 10 µL carefully added into the thin agar above the lower end of the starting quarter containing no bactericides. The plates were cultivated in a humid chamber at RT to prevent the upper layer from drying out and evaluated after 1, 2 and 3 days.

2.5. Laboratory Biofilm Assays

Bacterial strains were allowed to grow in tryptone soy broth (TSB; #1.05459; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at 30 g L-1 for up to 3 days with shaking at 80 rpm at RT. The samples were subsequently diluted in fresh TSB to an OD600 of 0.2 and allowed to rest for another hour at RT with shaking (80 rpm). Next, these cultures were diluted 1:1,000 in the medium specific to the respective experiment and sown into the wells of a 96 well-plate biofilm inoculator (MBEC Assay® Biofilm Inoculator with 96 well base & uncoated pegs, Innovotech, Edmonton AB, Canada) (V = 180 µL). Controls contained the respective medium only. Species combinations were created directly in the wells by adjusting the volumes (90 µL + 90 µL and 60 µL + 60 µL + 60 µL, respectively). Plates were subsequently incubated for 2 days on a horizontal shaker at 60 rpm. Growth was determined by transferring the supernatant to a new 96-well tissue culture plate (#92697, TPP, Trasadingen, Switzerland) and measuring the OD600 of the supernatant on a GloMax Explorer microplate reader (Promega AG, Dübendorf, Switzerland). To test the effect of an ecology change, the peg plate was transferred to a new base plate that had previously been filled with the required test media (180 µL well-1) and incubation continued on a horizontal shaker (RT, 60 rpm) for the time indicated.

Biofilm biomass was determined by staining the peg plate in a new 96-well tissue culture plate filled with Crystal Violet (#1.09218, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), diluted 1:100 in sterile tap water at 180 µL well-1 for 2 min. The peg plate was subsequently transferred to a new 96-well tissue culture plate containing 70% EtOH (180 µL well-1) and incubated for 10 min. on a horizontal shaker (60 rpm, RT). The biofilm biomass was determined by measuring the intensity of the dissolved crystal violet at 600 nm.

2.6. Sediment Experiments

The sediment samples originated from a workshop that had used a mineral-oil based, bactericide- and amine-containing MWF. These sediments had remained in the tank after the emptying and disposal of the fluid. They were humidified with deionized water and stored closed, but not airtight at RT for six months before being used for the experiment.

80 g of sediment were densely packed to the bottom of uprightly posed culture flasks with re-closable lids (#90652, TPP, Trasadingen, Switzerland) and then covered with 40 mL MWF M and MWF S, respectively. Incubation was performed at RT on an orbital shaker (80 rpm) for 2 and 4 weeks, respectively. Following incubation, the sediment was partitioned as exactly as possible into the upper (UH) and the lower half (LH) of the sediment layer. These samples were carefully homogenized by vortexing and manual stirring with a spatula in 50 mL Cellstar® tubes (Greiner Bio-One VACUETTE, St. Gallen, Switzerland) before analysis. In parallel, samples of the overlaying MWF (liquid phase) were collected.

DNA was isolated from both sample types using the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (#47016, Qiagen AG, Hilden, Germany). Briefly, duplicates of 250 mg of sediment or 250 µL of liquid, respectively, were added to the PowerBead Pro tubes, supplemented with 800 µL Solution CD1 and homogenized using a MP Biomedicals FastPrep® 24 classic bead beating grinder (LucernaChem, Luzern, Switzerland) for 45 sec. at a speed of 6.5. The isolation continued according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the duplicates were pooled at isolations end. Aliquots of the retrieved DNA were used for qPCR of total bacterial load using the primer pair Aer8f (5’-GATCATGGCTCAGATTGAACGC-3’) and Aer101r (5’-CCAGGCATTACTCACCCGTCCG-3’) (developed by BioSmart GmbH, Bern, Switzerland; ordered from Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany) using the SsoAdvanced™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules CA, USA) on a CFX-96 deep well real-time system attached to a C1000 Touch™ Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France). The cycling parameters were 95°C hold for 180 s for initial denaturation and activation of the hot-start polymerase, followed by 40 cycles of annealing for 30 s at 62°C, amplification for 30 s at 72°C, denaturation for 30 s at 95°C. Fluorescence was read at the end of each amplification cycle. At the very end, a melting curve was conducted between 55°C and 95°C with a 0.5°C increment read (5 s). Aliquots from the same DNA isolations were sent to Microsynth AG (Balgach, Switzerland) for amplicon metagenomics analysis using Microsynth’s standard primer set including bioinformatics.

2.7. Alkanolamine Assays

Via our extensive customer service network, we had worldwide access to MWF from end users, both our own and external customers. We sourced MWF samples from a total of five workshops that had shown stability issues due to the loss of MIPA. These samples were pooled and the microbial population isolated by centrifugation at 12’000 x g for 15 min. at 15°C in 2 mL centrifuge tubes (#0030 123.344; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The retrieved pellets were washed in 0.9% NaCl and once more pelleted by centrifugation at 12’000 x g for 15 min at 15°C. The resulting pellets were resuspended in MWF M in the same volume as the initial volume of the pooled samples and used for biofilm assays: Aliquots (5 mL well-1) were sown into the wells of a 6-well tissue culture plate (#92006, TPP, Trasadingen, Switzerland) and the plate incubated under static conditions for 1 week at RT. Then, the supernatant was carefully removed and the biofilms overlaid with 5 mL of freshly prepared MWF M supplemented with MIPA and TEA as described in chapter 2.3. Incubation remained static and continued for another three weeks at RT.

For control experiments, microbial populations were retrieved as described above, but then directly resuspended in MWF M supplemented with MIPA and TEA (initial volume). 5 mL aliquots were incubated in 15 mL centrifuge tubes (#430791; Corning, Reynosa, Mexico) on a tube roller (Phoenix Instruments RS-TR05; Faust Laborbedarf AG, Schaffhausen, Switzerland) for three weeks at RT. Tubes were exchanged every two days to prevent biofilm formation.

For alkanolamine analytics, samples were diluted 1:10 (v/v) in 2-Propanol (Supelco LiChrosolv® #1.02781, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) before performing analysis by ESI-MS equipped with an Ion-Trap (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pratteln, Switzerland) using a Kintex HILIC column (100 mm x 2.1 mm, 1.7 µm) fabricated by Phenomenex (#00D-4474-AN; Aschaffenburg, Germany). The gradient elution conditions are shown in

Table 1.

4. Discussion

In the metalworking industry, biofilms are widely regarded as nuisance due to their detrimental effects known as biofouling or biodeterioration. Nevertheless, the focus routinely remains on the coolant itself and hardly on the countless square meters of surfaces hidden in the intricate structures of metalworking machines and plants [

17,

18,

19], analogous to the problem with fungal contamination [

14]. This is also reflected in the literature, which has only a few publications to offer in this regard.

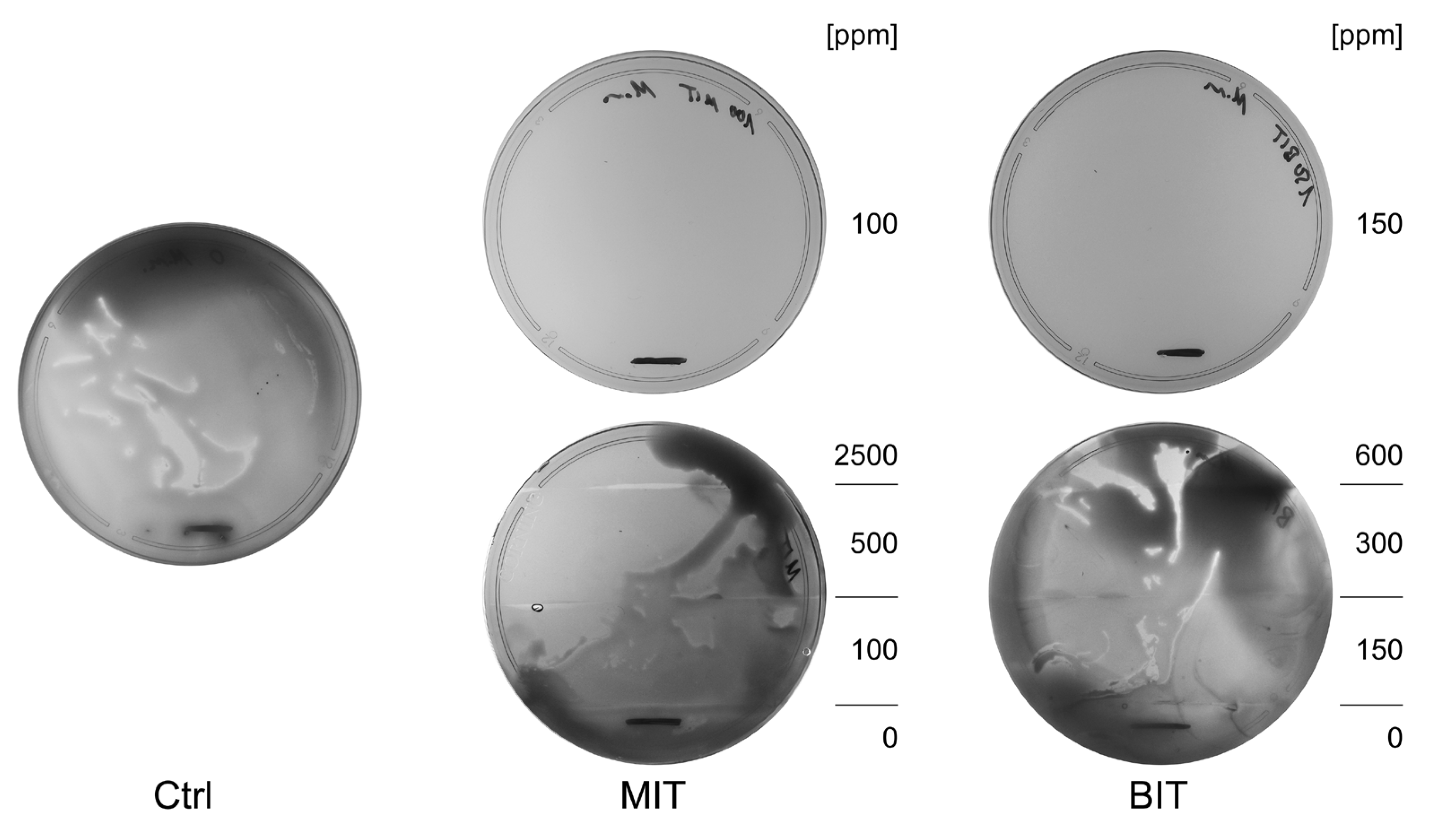

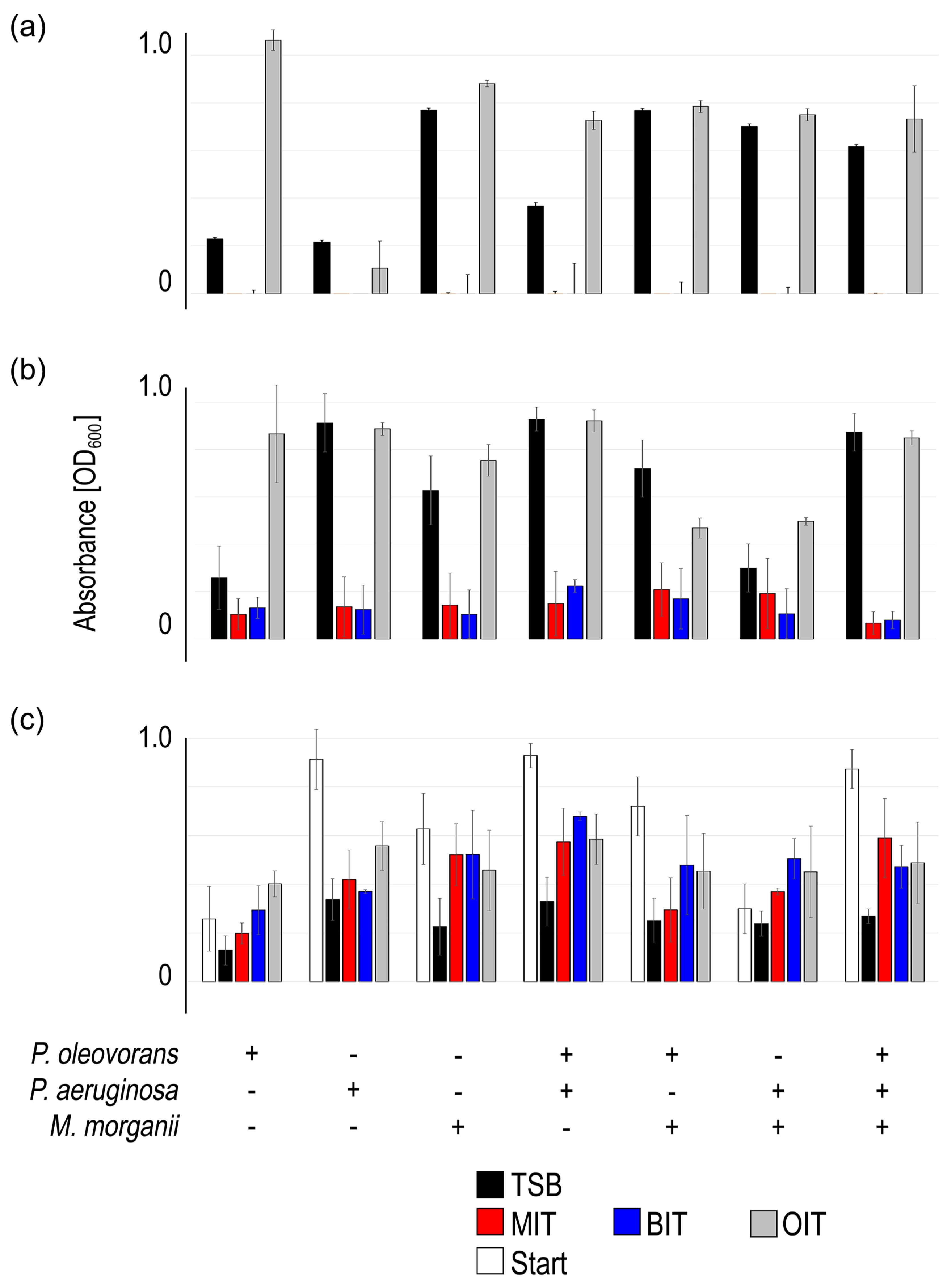

The industry’s answer to the biofilm issue has long been the addition of bactericides, either as in-drum or tank side additives. However, legal constraints to reduce the usage concentration on these chemicals are increasing [

11] and our experiments showed that their effect on established biofilms was variable at best anyway. Importantly, adaptation to rather high concentrations of MIT and BIT, respectively, was easily possible – at least for

M. morganii.

MWFs, on the other hand, are a complex mixture of a variety of organic compounds, and growth has been shown to be challenging for bacteria that enter the liquid unprepared [

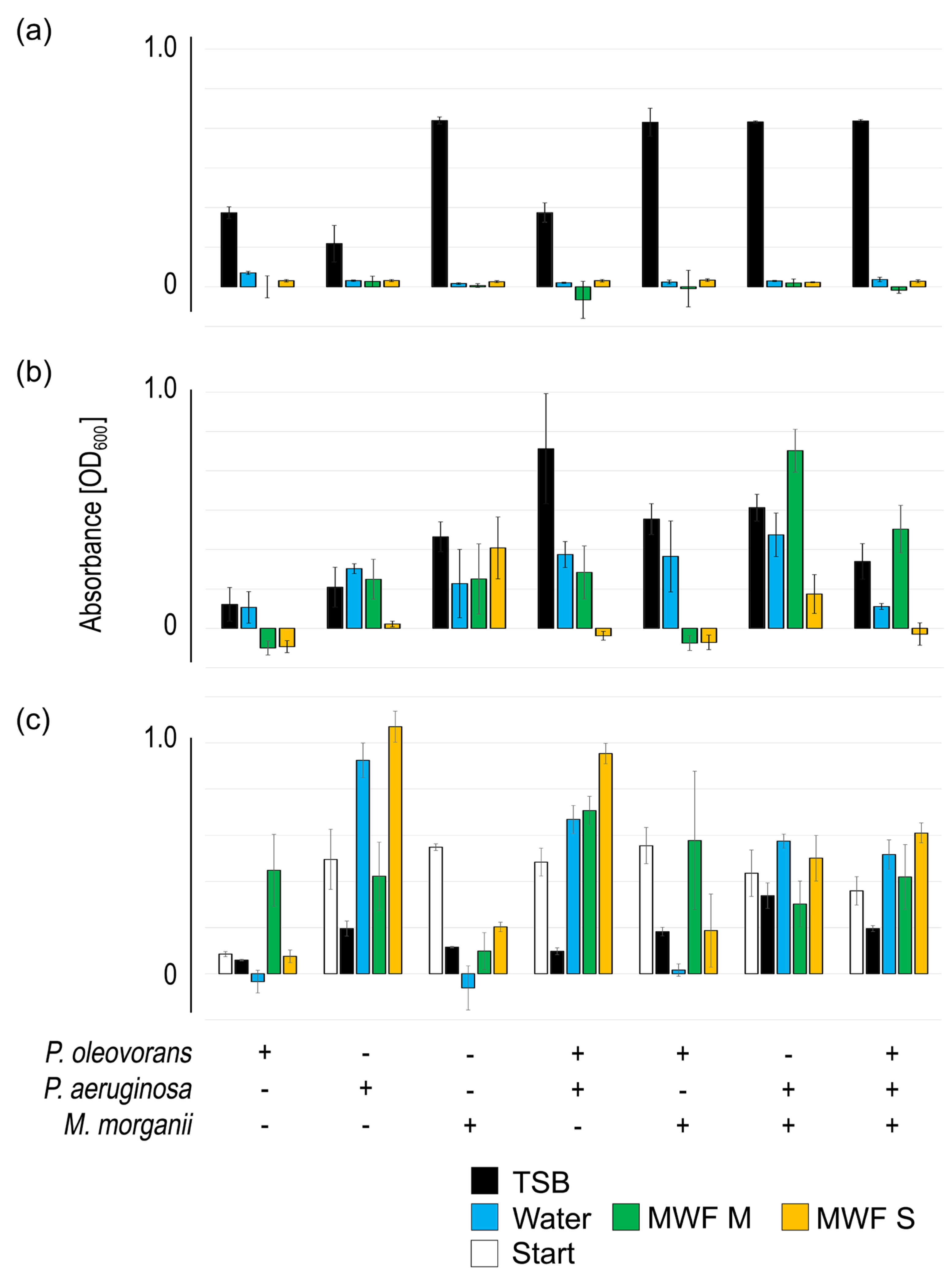

24,

31], possibly due to the abrupt change in environment, which we were able to confirm. Importantly however, biofilm formation still occurred and the influence of MWFs on established biofilms was small to non-existent. This confirmed results from antibiotic research, which showed that biofilms are much more resistant than the corresponding planktonic bacteria [

4].

Challenging to interpret were the results received with species combinations. Some, mainly those containing

P. aeruginosa, seemed to work better than others or the respective single species biofilms. However, there was no clear picture that certain combinations would always perform better in all the ecological environments tested. This leads us to conclude that the decision for or against cooperation depends on the actual environment, which may even change over time. This may indicate that results describing the social interactions of individual species in MWFs [

31] were only correct in the respective context, while in another environment they could lead to completely different results. This might also have unpredictable effects on consortia that were tested for the biodegradation of spent MWFs [

13].

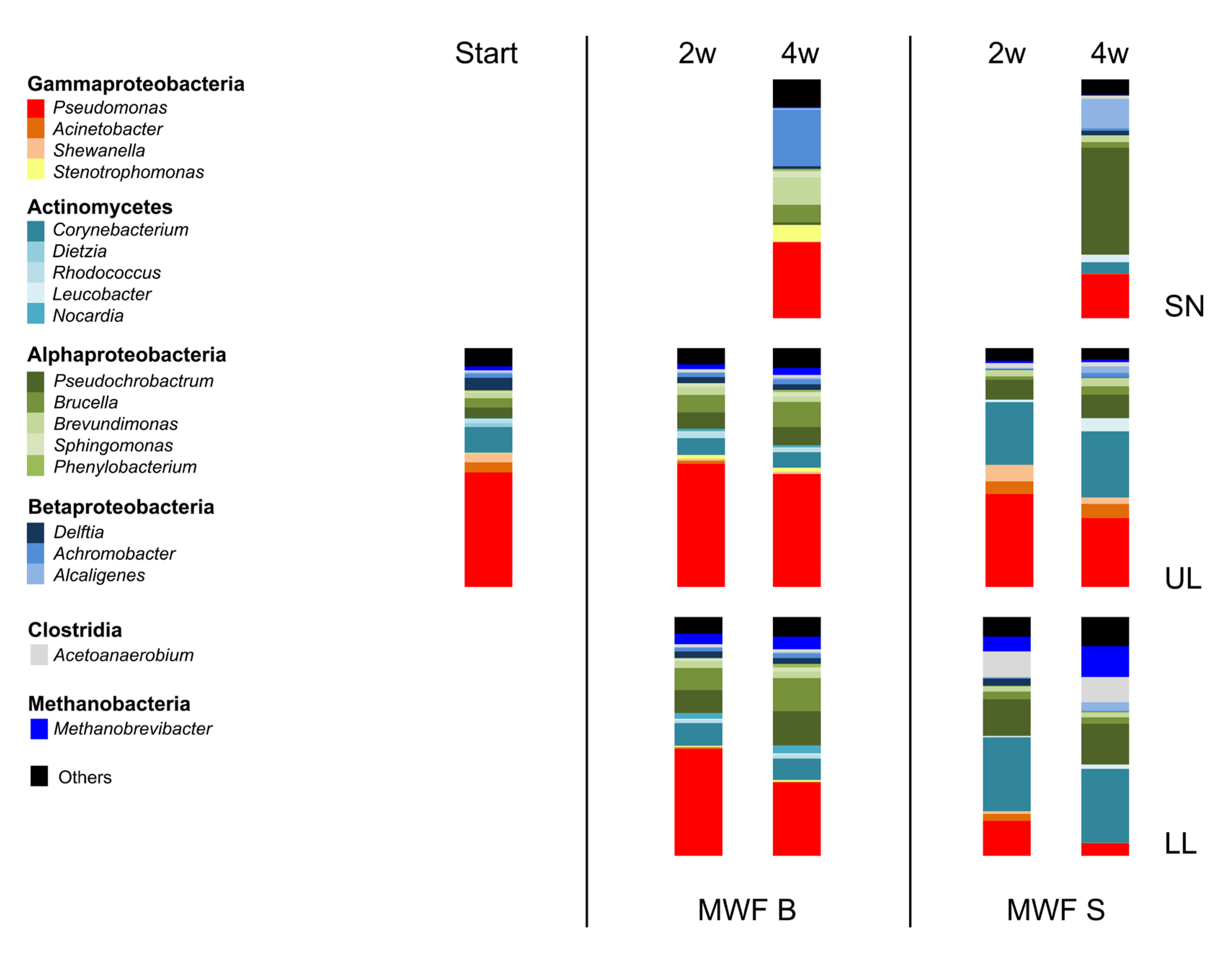

When tests were continued using sediment biofilms, comparable results were obtained: The biomass itself, based on qPCR tests, remained stable, whereas the population composition shifted remarkably, depending on the MWF applied. Basically, MWF M led to less changes in population dynamics than MWF S did. One of the reasons might be, that the sediment used in those experiments originated from a MWF system running a mineral oil based MWF. This might signify that distinct changes in MWF chemistry have a more pronounced influence on the population composition in biofilms than subtle variations, for good or ill. MWF S led to more pronounced increases of genera featuring more (facultative) anaerobes. This might have negative effects, as anaerobic species were described to be more important of microbiologically influenced corrosion [

19]. On the other hand, strong environmental changes could also lead to a dispersion of biofilms [

38], which could have a positive effect if the dissolved biofilm pieces were subsequently removed by filtration systems, which are often attached to machines or centralized systems [

15,

39]. Sorely, this was a scenario impossible to test within the experimental setup. In addition, our experiments revealed that the population composition in the liquid phase does not allow any conclusions to be drawn about the taxa in the biofilm phase: The population composition, although largely dependent on the biofilm input, was distinct. Likewise, it is impossible to draw conclusions about biofilm quantities [

16].

The need to switch to biofilm analysis is underlined by the finding that these consortia are gaining function. In our case, this was the ability to degrade MIPA, which proved to be toxic to them. As this requires a large amount of biofilm to be present, it took a long time for noticeable symptoms to appear, such as a significant drop in pH, the appearance of odor and the loss of technical properties. At least for the customers concerned, this all came out of nowhere. Interestingly, the bacteria in the MWF only became detectable by heterotrophic plate counts after the symptoms described had occurred. Even the addition of system cleaners and/or biocides and the removal of the fluid with subsequent refilling were rather ineffective, as the biofilms remained largely intact and quickly reformed again. Thus the “vicious circle” [

17] started all over, often accelerating and resulting in a considerably shortened service life.

Overall, this condemns the microbiological analysis of coolant samples, as is common in industry today, to the status of occupational therapy. A switch to a methodology that focuses on the detection and characterization of biofilms is urgently needed and must be implemented in the coming years.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.vK. and P.K.; methodology, G.vK., B.M. and P.K.; validation, G.vK, P.K..; formal analysis, P.K.; investigation, G.vK., L.Y.S., B.M., R.L. and P.K.; data curation, G.vK and P.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.K.; writing—review and editing, L.Y.S and R.L.; visualization, P.K.; supervision, P.K.; project administration, P.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Resistance formation in real-time was tested over 3 days using assembled mini-MEGA assays: TSA plates contained increasing doses of MIT (0, 100 ppm, 500 ppm, 2,500 ppm) or BIT (0, 150 ppm, 300 ppm, 600 ppm), whereas control experiments either contained no bactericides or the lowest dose of MIT and BIT, respectively. A typical example of three independent experiments after an incubation of 3 days is shown. The visible lines in the lower part of the plates indicate the zone where bacteria were added.

Figure 1.

Resistance formation in real-time was tested over 3 days using assembled mini-MEGA assays: TSA plates contained increasing doses of MIT (0, 100 ppm, 500 ppm, 2,500 ppm) or BIT (0, 150 ppm, 300 ppm, 600 ppm), whereas control experiments either contained no bactericides or the lowest dose of MIT and BIT, respectively. A typical example of three independent experiments after an incubation of 3 days is shown. The visible lines in the lower part of the plates indicate the zone where bacteria were added.

Figure 2.

The impact of the biocides MIT, BIT and OIT on consortia made up of P. oleovorans, P. aeruginosa, M. morganii and equal parts mixtures regarding planktonic growth (a), biofilm formation (b) and biofilm persistence (c). The mean value and standard deviation of three independent experiments are shown (obtained value minus control value without bacteria). Plus sign (+) indicates inclusion, minus sign (-) indicates exclusion of the respective species.

Figure 2.

The impact of the biocides MIT, BIT and OIT on consortia made up of P. oleovorans, P. aeruginosa, M. morganii and equal parts mixtures regarding planktonic growth (a), biofilm formation (b) and biofilm persistence (c). The mean value and standard deviation of three independent experiments are shown (obtained value minus control value without bacteria). Plus sign (+) indicates inclusion, minus sign (-) indicates exclusion of the respective species.

Figure 3.

The impact of MWF M, MWF S and tap water on consortia made up of P. oleovorans, P. aeruginosa, M. morganii and equal parts mixtures regarding planktonic growth (a), biofilm formation (b) and biofilm persistence (c). The mean value and standard deviation of three independent experiments are shown (obtained value minus control value without bacteria). Plus sign (+) indicates inclusion, minus sign (-) indicates exclusion of the respective species.

Figure 3.

The impact of MWF M, MWF S and tap water on consortia made up of P. oleovorans, P. aeruginosa, M. morganii and equal parts mixtures regarding planktonic growth (a), biofilm formation (b) and biofilm persistence (c). The mean value and standard deviation of three independent experiments are shown (obtained value minus control value without bacteria). Plus sign (+) indicates inclusion, minus sign (-) indicates exclusion of the respective species.

Figure 4.

Bacterial populations at start and after up to 4 weeks of co-incubation with MWF M or MWF S in UH, LH as well as the MWF itself (SN). Observed changes in MWF M were clearly less pronounced than in MWF S. The normalized mean value of two independent experiments is shown.

Figure 4.

Bacterial populations at start and after up to 4 weeks of co-incubation with MWF M or MWF S in UH, LH as well as the MWF itself (SN). Observed changes in MWF M were clearly less pronounced than in MWF S. The normalized mean value of two independent experiments is shown.

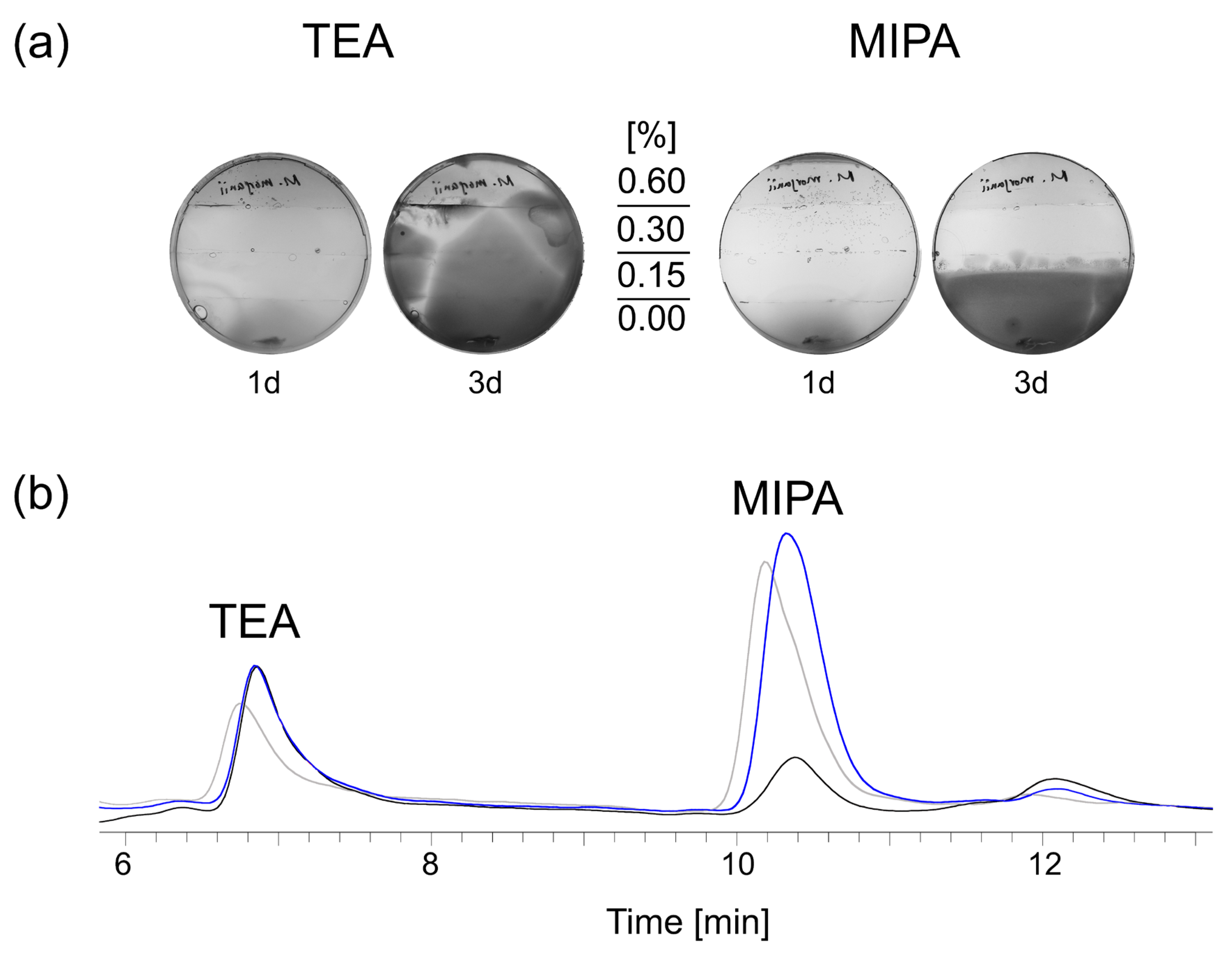

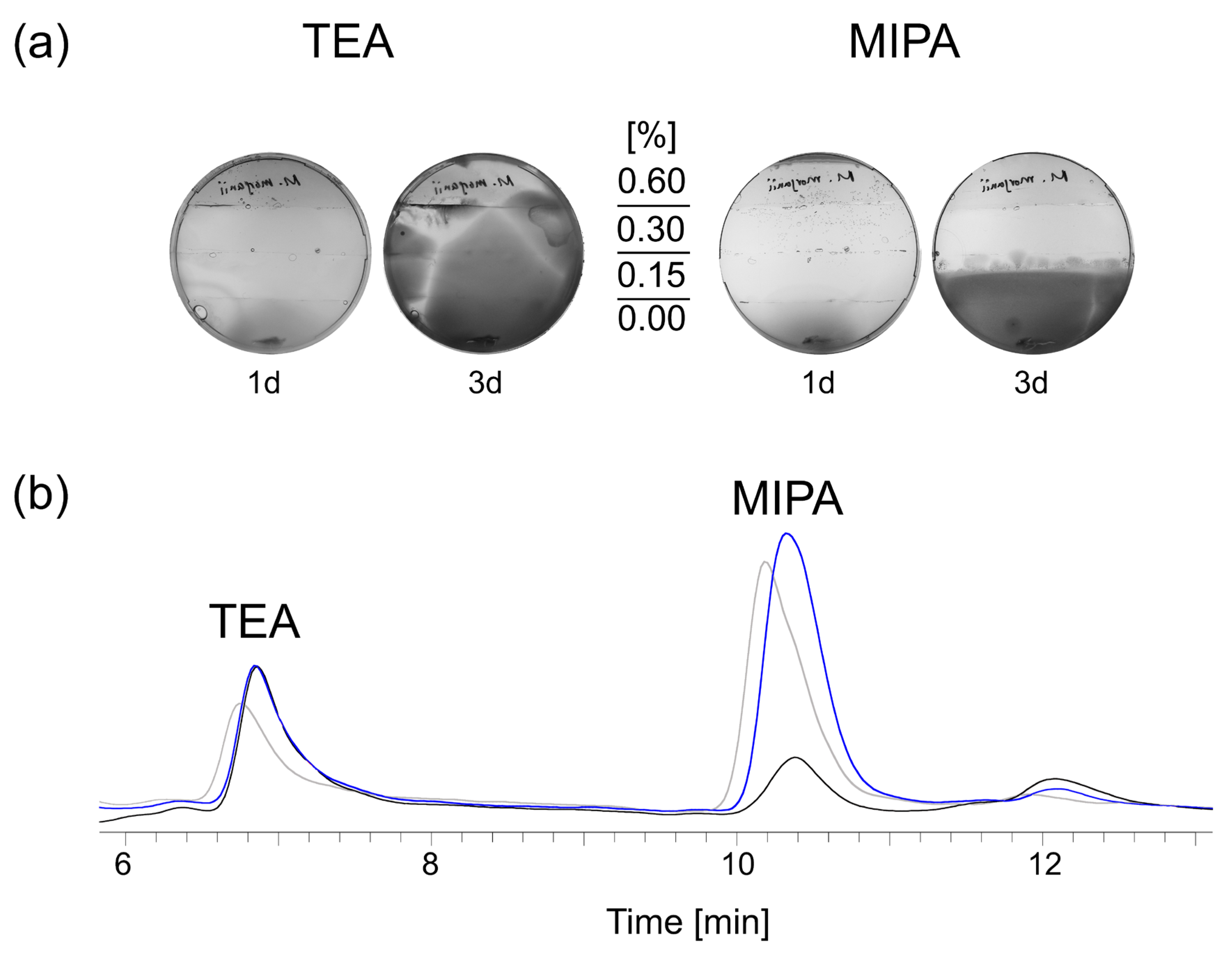

Figure 5.

Resistance formation in real-time was tested over 3 days using assembled mini MEGA assays: TSA plates contained increasing doses of TEA (0, 0.15%, 0.3%, 0.6%) or MIPA (0, 0.15%, 0.3%, 0.6%). A typical example of three independent experiments is shown after 1 and 3 days. The visible line in the lower part of the plate indicates the zone where the bacteria were added (a). Biofilm (black), but not planktonic bacteria (blue) depleted MIPA after incubation for 3 weeks in supplemented MWF M, as shown by alkanolamine analytics. The untreated control is shown in grey. A typical example of three independent experiments is shown (b) or complete loss of MIPA was detectable (

Figure 5b), whereas TEA was neither affected by planktonic nor biofilm populations. This signified that the degradation of MIPA was only possible from the protection of the biofilm layer. At that time, sorely, we only determined the composition of the population by heterotrophic plate counts, which could not capture its diversity.

Figure 5.

Resistance formation in real-time was tested over 3 days using assembled mini MEGA assays: TSA plates contained increasing doses of TEA (0, 0.15%, 0.3%, 0.6%) or MIPA (0, 0.15%, 0.3%, 0.6%). A typical example of three independent experiments is shown after 1 and 3 days. The visible line in the lower part of the plate indicates the zone where the bacteria were added (a). Biofilm (black), but not planktonic bacteria (blue) depleted MIPA after incubation for 3 weeks in supplemented MWF M, as shown by alkanolamine analytics. The untreated control is shown in grey. A typical example of three independent experiments is shown (b) or complete loss of MIPA was detectable (

Figure 5b), whereas TEA was neither affected by planktonic nor biofilm populations. This signified that the degradation of MIPA was only possible from the protection of the biofilm layer. At that time, sorely, we only determined the composition of the population by heterotrophic plate counts, which could not capture its diversity.

Table 1.

Gradient elution conditions. Phase A: 100 % Acetonitrile (#RC-ACNMS-2.5, Reuss-Chemie, Tägerig, Switzerland); Phase B: 98.9% deionized water, 0.1% Ammonium Acetate (Supelco LiChropur™ #5.33004; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 1.0% Acetonitrile. The flow was 250 µL min-1.

Table 1.

Gradient elution conditions. Phase A: 100 % Acetonitrile (#RC-ACNMS-2.5, Reuss-Chemie, Tägerig, Switzerland); Phase B: 98.9% deionized water, 0.1% Ammonium Acetate (Supelco LiChropur™ #5.33004; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 1.0% Acetonitrile. The flow was 250 µL min-1.

| Time [min] |

Phase A [%] |

Phase B [%] |

| 0.00 |

95 |

5 |

| 5.00 |

70 |

30 |

| 10.00 |

70 |

30 |

| 20.00 |

50 |

50 |

| 22.00 |

95 |

5 |

| 25.00 |

95 |

5 |

Table 2.

Abundance of taxonomic units at start of the experiment and upon co-incubation with MWF M and MWF S, respectively, for up to 4 weeks. The normalized mean value of three independent experiments is shown. The Jaccard index [

36] was used to calculate the similarity between the treated samples to the sediment at start.

Table 2.

Abundance of taxonomic units at start of the experiment and upon co-incubation with MWF M and MWF S, respectively, for up to 4 weeks. The normalized mean value of three independent experiments is shown. The Jaccard index [

36] was used to calculate the similarity between the treated samples to the sediment at start.

| MWF M |

Start

|

UH

2w

|

UH

4w

|

LH

2w

|

LH

4w

|

SN

4w

|

| Jaccard Index |

n.a. |

97.3 |

95.5 |

95.1 |

74.5 |

59.9 |

| Total Genera |

62 |

61 |

61 |

61 |

61 |

33 |

| Gammaproteobacteria [%] |

57.4 |

55.3 |

49.7 |

46.1 |

31.6 |

39.9 |

| Actinomycetes [%] |

14.5 |

11.0 |

9.6 |

13.7 |

14.6 |

0.7 |

| Alphaproteobacteria [%] |

11.6 |

19.2 |

23.0 |

23.0 |

34.3 |

24.6 |

| Betaproteobacteria [%] |

7.6 |

4.5 |

5.1 |

4.5 |

4.8 |

26.2 |

| Clostridia [%] |

0.7 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

| Methanobrevibacter [%] |

1.7 |

2.1 |

2.9 |

4.4 |

5.3 |

0.4 |

| |

| MWF S |

Start

|

UH

2w

|

UH

4w

|

LH

2w

|

LH

4w

|

SN

4w

|

| Jaccard Index |

n.a. |

84.9 |

69.8 |

39.1 |

20.6 |

29.8 |

| Total Genera |

62 |

40 |

41 |

41 |

30 |

39 |

| Gammaproteobacteria [%] |

57.4 |

51.2 |

37.5 |

18.6 |

5.5 |

18.9 |

| Actinomycetes [%] |

14.5 |

27.3 |

33.1 |

31.8 |

32.8 |

9.0 |

| Alphaproteobacteria [%] |

11.6 |

12.5 |

17.0 |

20.9 |

22.1 |

50.0 |

| Betaproteobacteria [%] |

7.6 |

0.8 |

4.7 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

15.2 |

| Clostridia [%] |

0.7 |

2.1 |

1.9 |

10.7 |

10.6 |

1.4 |

| Methanobrevibacter [%] |

1.7 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

6.2 |

12.9 |

0.3 |