Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Technological Progress in Battery Recycling

1.1.1. Background and Motivation

1.1.2. Composition and Structure of EV Batteries

1.1.3. Environmental and Economic Importance of Battery Recycling

1.1.4. Overview of Recycling Methods

- Direct Recycling, also known as physical or mechanical recycling, aims to preserve the integrity of battery components, such as the cathode, for reuse. Although still in the developmental stage, direct recycling has the potential to reduce energy consumption and maintain the functional value of recovered materials [24,25].

1.1.5. Challenges and Barriers to Effective Recycling

1.1.6. Policy and Regulatory Landscape

1.1.7. Objectives and Scope of the Review

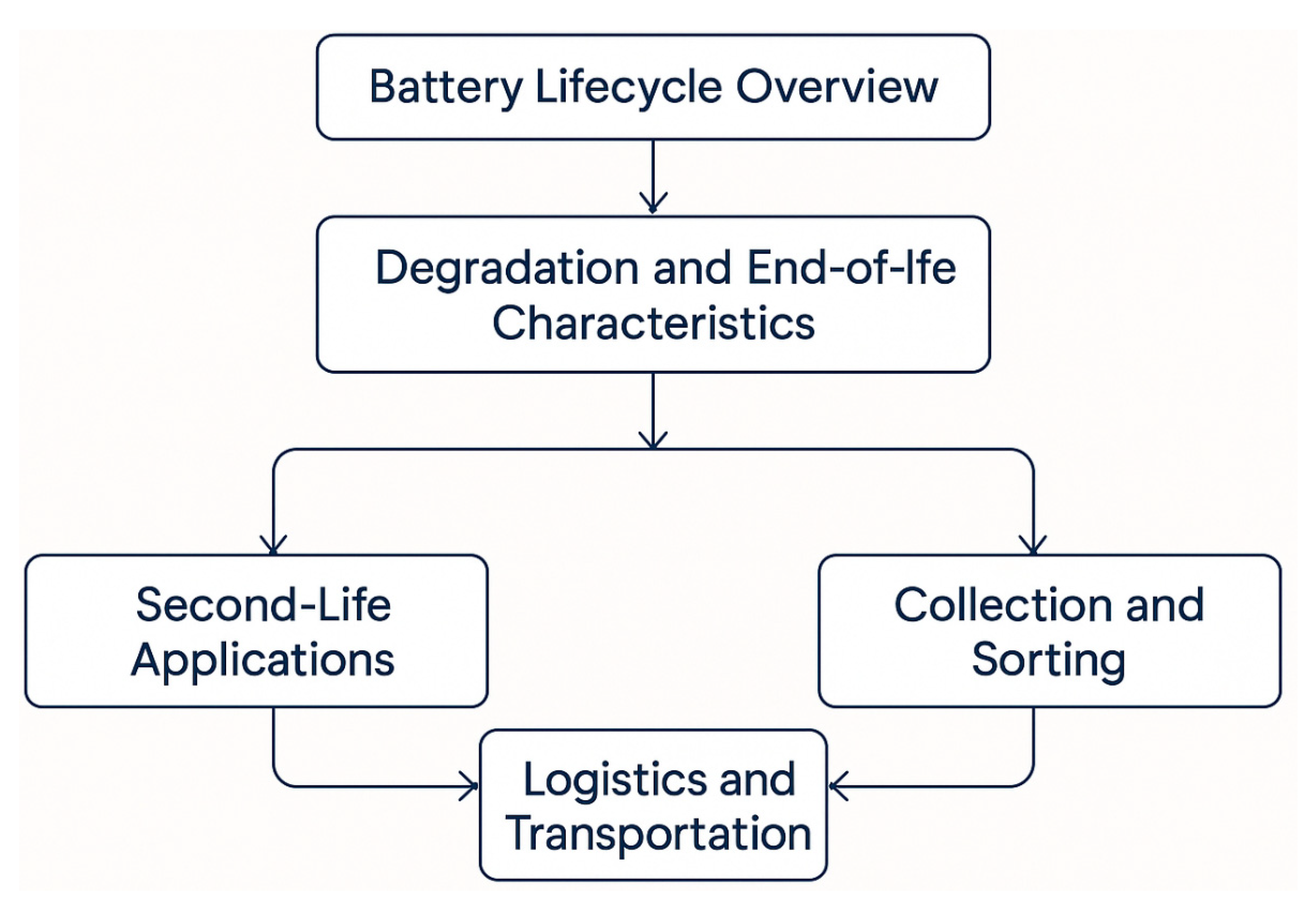

1.2. Battery Lifecycle and End-of-Life Scenarios

1.2.1. Overview of Battery Lifecycle

1.2.2. Degradation and End-of-Life Characteristics

1.2.3. Second-Life Applications

1.2.4. Collection and Sorting

1.2.5. Logistics and Transportation

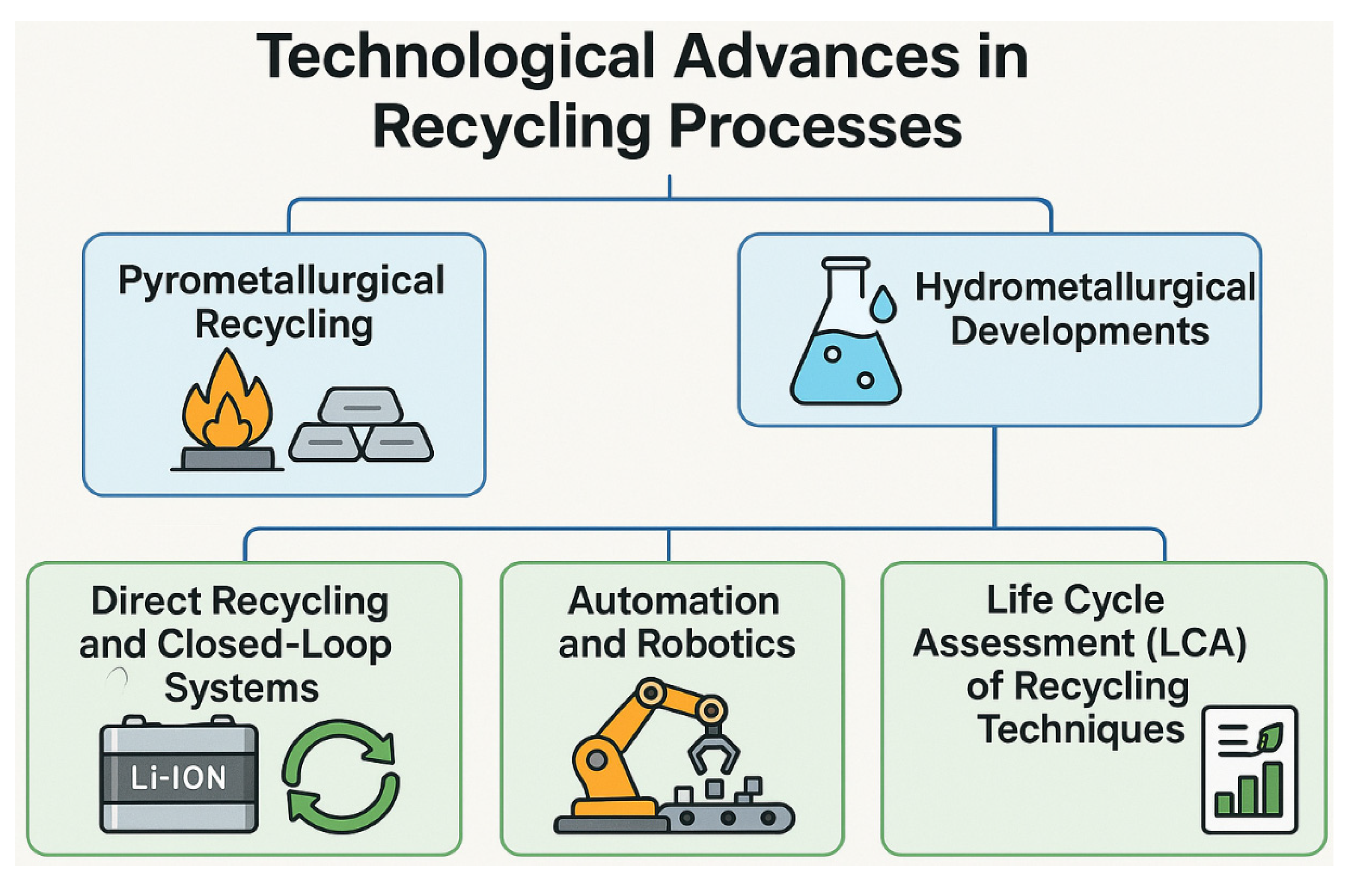

1.3. Technological Advances in Recycling Processes

1.3.1. Pyrometallurgical Recycling in Practice

1.3.2. Hydrometallurgical Developments

1.3.3. Direct Recycling and Closed-Loop Systems

1.3.4. Automation and Robotics

1.3.5. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Recycling Techniques

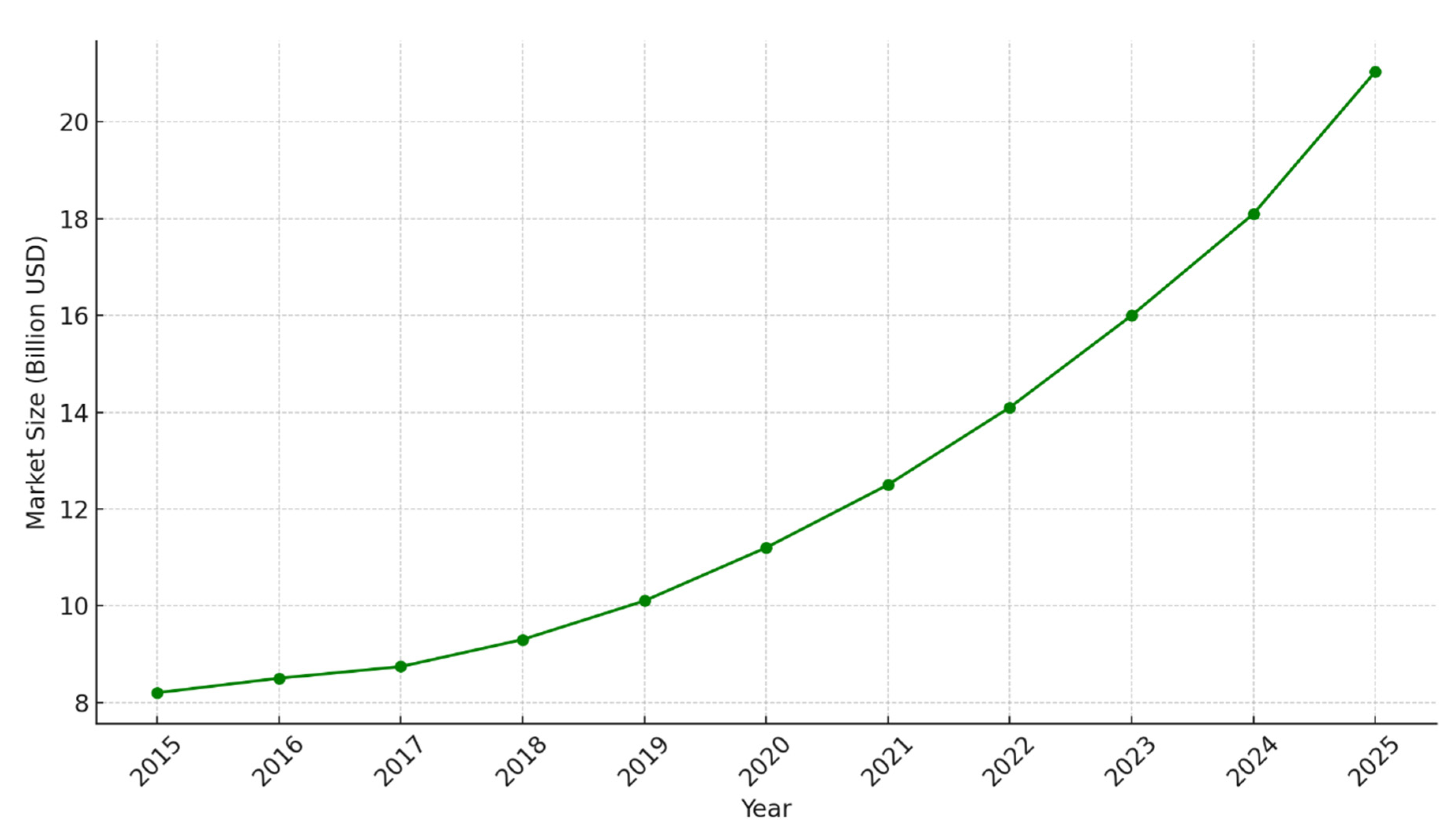

1.3.6. Global Battery Recycling Market Growth (2015–2025)

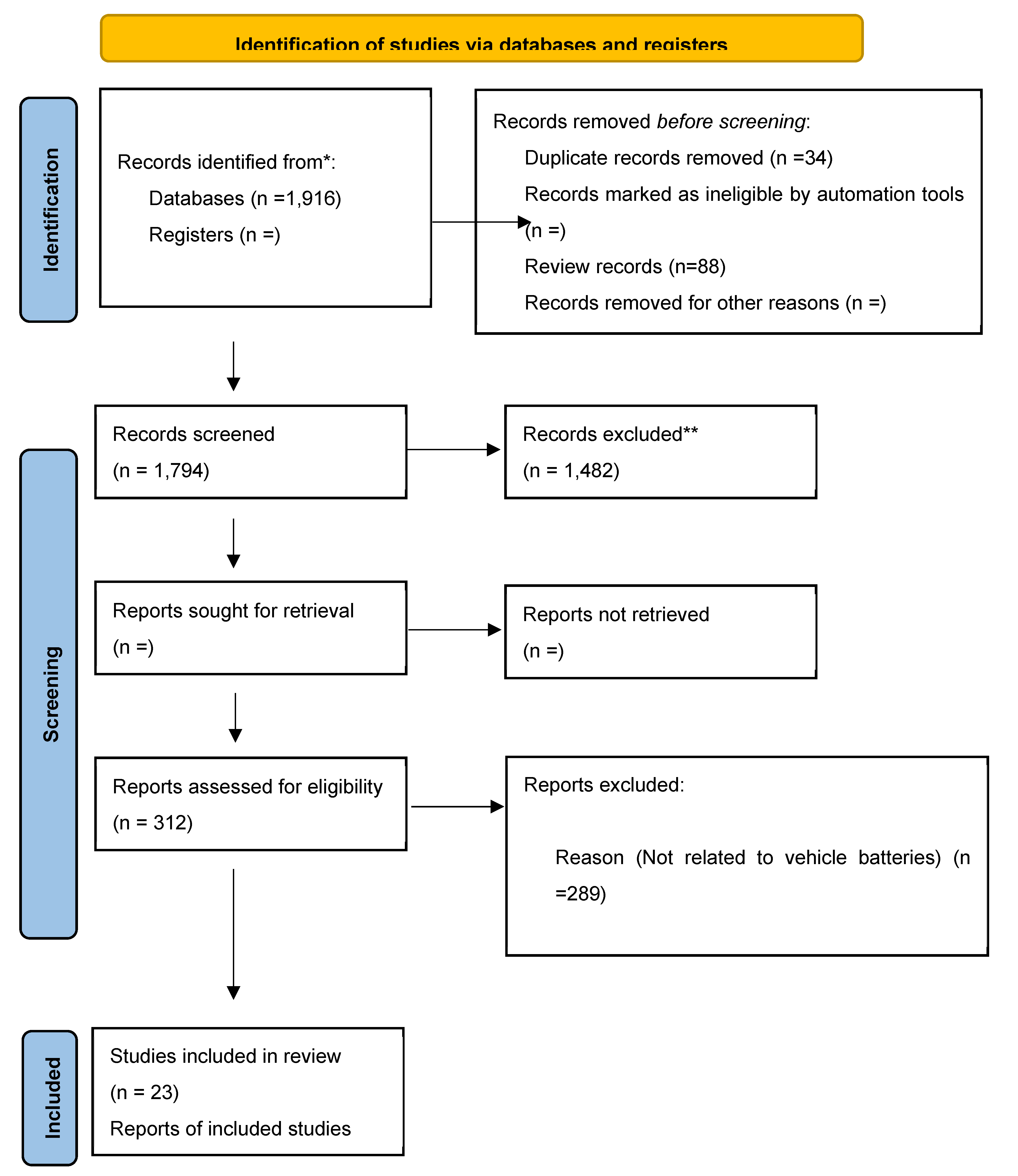

2. Methodology

3. Results

4. Discussions

4.1. Energy Density and Technical Performance

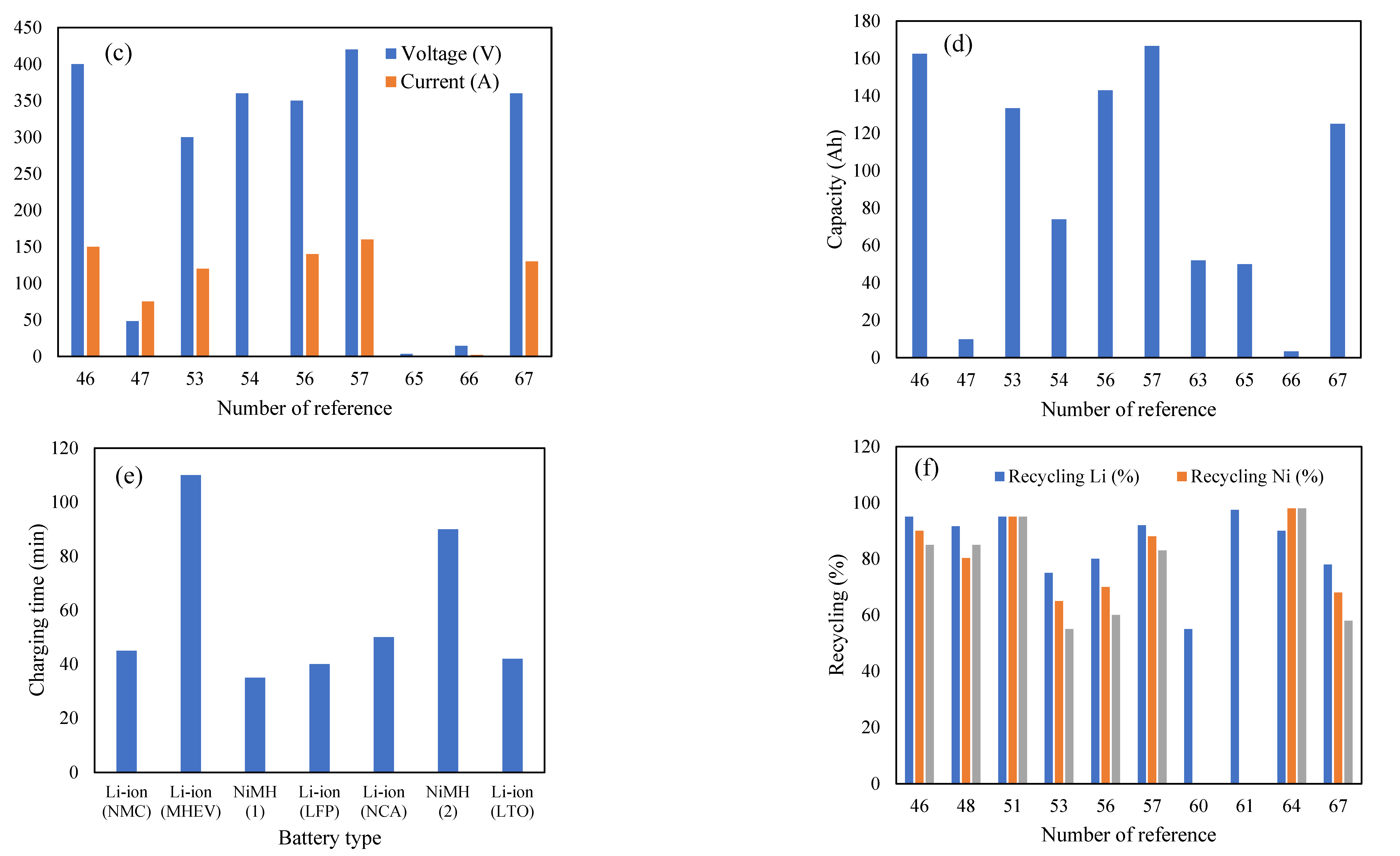

4.2. Recycling Efficiency and Metal Recovery

4.3. Environmental Impact and Process Conditions

4.4. Cost Considerations and Economic Viability

4.5. Safety Considerations: State of Charge (SOC) and Thermal Stability

4.6. Strategic Implications for Future Battery Design and Recycling

4.7. Policy and Market Dynamics

4.8. Processing

4.8.1. General Overview

4.8.2. Elemental Trends and Highlights

- Carbon (C):

- Aluminum (Al):

- Copper (Cu):

- Iron (Fe):

- Silver (Ag) and Gold (Au):

- Palladium (Pd):

- Lithium (Li):

- Nickel (Ni) and Cobalt (Co):

- Manganese (Mn):

4.8.3. Observations on Energy-Normalized Values

- The highest normalized mass concentration across the samples is associated with lithium (Li) and manganese (Mn).

- For instance, sample 16 shows 410.5 g/kWh lithium content, suggesting a lithium-rich energy storage solution, likely associated with high-energy-density battery chemistries (e.g., LCO or NMC batteries).

- Nickel and cobalt display typical co-dependence, reflecting modern trends in battery technology where high-nickel cathodes (like NMC811) are increasingly preferred for their higher energy density despite their higher cost and environmental impact.

4.8.4. Trends Across Samples

- In earlier samples (N=7 to N=11), moderate values of Al, Cu, and Fe dominate, suggesting a mix of structural and conductive material focus.

- Samples 15–18 show more emphasis on active materials, particularly lithium, nickel, and cobalt, implying a shift from supporting structures to the active battery core materials.

- Sample 19 reveals relatively consistent normalized values for C, Cu, and Li, hinting at a stable design focused on performance consistency, possibly from a standardized battery cell production line.

4.8.5. Implications for Recycling and Sustainability

Conclusion

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Declaration of competing interest

Nomenclature

| BEV | Battery Electric Vehicle |

| BMS | Battery Management System |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System |

| Co | Cobalt |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| EOL | End of Life |

| LIB | Lithium-Ion Battery |

| Li | Lithium |

| LFP | Lithium Iron Phosphate |

| LCO | Lithium Cobalt Oxide |

| LMO | Lithium Manganese Oxide |

| Li-NMC | Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide |

| Li-NCA | Lithium Nickel Cobalt Aluminum Oxide |

| Ni | Nickel |

| NMC | Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxides |

| MHEV | Mild hybrid electric vehicle |

| Mn | Manganese |

| Pyrometallurgy | High-temperature process for metal recovery |

| Hydrometallurgy | Aqueous solution-based metal extraction |

| Direct Recycling | Recovery of battery components with minimal reprocessing |

| SOH | State of Health (battery degradation metric) |

| SOC | State of Charge |

| WEEE | Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Directive (EU legislation) |

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| Circular Economy | Economic system aimed at eliminating waste and continual resource use |

References

- IEA (2024). Available at: https://www.iea.org/reports/italy-2023/executive-summary . (accessed 30.04.2025).

- Moore, Jon. "BloombergNEF: Strategies for a Cleaner, More Competitive Future." In World Scientific Encyclopedia of Climate Change: Case Studies of Climate Risk, Action, and Opportunity Volume 3, pp. 247-275. 2021.

- Meegoda, Jay N., Sarvagna Malladi, and Isabel C. Zayas. "End-of-life management of electric vehicle lithium-ion batteries in the United States." Clean Technologies 4, no. 4 (2022): 1162-1174.

- Bell, Matthew. "The Cobalt Mines of the Democratic Republic of Congo." Global Encounters: New Visions Department of Geography and Planning, Queen’s University: 24.

- Wu, Wenqi, Ming Zhang, Danlin Jin, Pingping Ma, Wendi Wu, and Xueli Zhang. "Decision-making analysis of electric vehicle battery recycling under different recycling models and deposit-refund scheme." Computers & Industrial Engineering 191 (2024): 110109.

- Tripathy, Asit, Atanu Bhuyan, Ramakrushna Padhy, and Laura Corazza. "Technological, organizational, and environmental factors affecting the adoption of electric vehicle battery recycling." IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management (2022).

- Wesselkämper, Jannis, and Stephan Von Delft. "Current status and future research on circular business models for electric vehicle battery recycling." Resources, Conservation and Recycling (2024).

- Chan, Ka Ho, Monu Malik, and Gisele Azimi. "Direct recycling of degraded lithium-ion batteries of an electric vehicle using hydrothermal relithiation." Materials Today Energy 37 (2023): 101374.

- Toro, Luigi, Emanuela Moscardini, Ludovica Baldassari, Flavia Forte, Ilario Falcone, Jacopo Coletta, and Lorenzo Toro. "A systematic review of battery recycling technologies: advances, challenges, and future prospects." Energies 16, no. 18 (2023): 6571.

- Wang, Yitong, Ruguo Fan, Rongkai Chen, Xiao Xie, and Can Ke. "Exploring the coevolution dynamics of residents and recyclers in electric vehicle battery recycling decisions on the two-layer heterogeneous complex networks." Applied Energy 382 (2025): 125235.

- Tang, Yanyan, Qi Zhang, Boyu Liu, Yan Li, Ruiyan Ni, and Yi Wang. "What influences residents’ intention to participate in the electric vehicle battery recycling? Evidence from China." Energy 276 (2023): 127563.

- Dong, Boqi, and Jianping Ge. "What affects consumers' intention to recycle retired EV batteries in China?." Journal of Cleaner Production 359 (2022): 132065.

- Huang, X., Lin, Y., Liu, F., Lim, M.K. and Li, L., 2022. Battery recycling policies for boosting electric vehicle adoption: evidence from a choice experimental survey. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 24(8), pp.2607-2620.

- Hao, Hao, Wenxian Xu, Fangfang Wei, Chuanliang Wu, and Zhaoran Xu. "Reward–penalty vs. deposit–refund: Government incentive mechanisms for EV battery recycling." Energies 15, no. 19 (2022): 6885.

- Dikmen, İsmail Can, and Teoman Karadağ. "Electrical method for battery chemical composition determination." IEEE Access 10 (2022): 6496-6504.

- Lin, Jiao, Xiaodong Zhang, Ersha Fan, Renjie Chen, Feng Wu, and Li Li. "Carbon neutrality strategies for sustainable batteries: from structure, recycling, and properties to applications." Energy & Environmental Science 16, no. 3 (2023): 745-791.

- Latini, Dario, Marco Vaccari, Marco Lagnoni, Martina Orefice, Fabrice Mathieux, Jaco Huisman, Leonardo Tognotti, and Antonio Bertei. "A comprehensive review and classification of unit operations with assessment of outputs quality in lithium-ion battery recycling." Journal of Power Sources 546 (2022): 231979.

- Wasesa, Meditya, Taufiq Hidayat, Dinda Thalia Andariesta, Made Giri Natha, Alma Kenanga Attazahri, Mochammad Agus Afrianto, Mohammad Zaki Mubarok, Zulfiadi Zulhan, and Utomo Sarjono Putro. "Economic and environmental assessments of an integrated lithium-ion battery waste recycling supply chain: A hybrid simulation approach." Journal of Cleaner Production 379 (2022): 134625.

- Nguyen-Tien, Viet, Qiang Dai, Gavin DJ Harper, Paul A. Anderson, and Robert JR Elliott. "Optimising the geospatial configuration of a future lithium ion battery recycling industry in the transition to electric vehicles and a circular economy." Applied Energy 321 (2022): 119230.

- Van Hoof, Gert, Bénédicte Robertz, and Bart Verrecht. "Towards sustainable battery recycling: a carbon footprint comparison between pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical battery recycling flowsheets." Metals 13, no. 12 (2023): 1915.

- Liu, Aiwei, Guangwen Hu, Yufeng Wu, and Fu Guo. "Life cycle environmental impacts of pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical recovery processes for spent lithium-ion batteries: present and future perspectives." Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 26, no. 2 (2024): 381-400.

- Saleem, Usman, Bhaskar Joshi, and Sulalit Bandyopadhyay. "Hydrometallurgical routes to close the loop of electric vehicle (EV) lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) value chain: a review." Journal of Sustainable Metallurgy 9, no. 3 (2023): 950-971.

- Chen, Quanwei, Yukun Hou, Xin Lai, Kai Shen, Huanghui Gu, Yiyu Wang, Yi Guo, Languang Lu, Xuebing Han, and Yuejiu Zheng. "Evaluating environmental impacts of different hydrometallurgical recycling technologies of the retired nickel-manganese-cobalt batteries from electric vehicles in China." Separation and Purification Technology 311 (2023): 123277.

- Chen, Quanwei, Xin Lai, Yukun Hou, Huanghui Gu, Languang Lu, Xiang Liu, Dongsheng Ren, Yi Guo, and Yuejiu Zheng. "Investigating the environmental impacts of different direct material recycling and battery remanufacturing technologies on two types of retired lithium-ion batteries from electric vehicles in China." Separation and Purification Technology 308 (2023): 122966.

- Rosenberg, Sonja, Leonard Kurz, Sandra Huster, Steven Wehrstein, Steffen Kiemel, Frank Schultmann, Frederik Reichert, Ralf Wörner, and Simon Glöser-Chahoud. "Combining dynamic material flow analysis and life cycle assessment to evaluate environmental benefits of recycling–A case study for direct and hydrometallurgical closed-loop recycling of electric vehicle battery systems." Resources, Conservation and Recycling 198 (2023): 107145.

- Rizos, Vasileios, and Patricia Urban. "Barriers and policy challenges in developing circularity approaches in the EU battery sector: An assessment." Resources, Conservation and Recycling 209 (2024): 107800.

- Gautam, Deepak, and Nomesh Bolia. "Fostering second-life applications for electric vehicle batteries: A thorough exploration of barriers and solutions within the framework of sustainable energy and resource management." Journal of Cleaner Production 456 (2024): 142401.

- Lin, Yang, Zhongwei Yu, Yingming Wang, and Mark Goh. "Performance evaluation of regulatory schemes for retired electric vehicle battery recycling within dual-recycle channels." Journal of environmental management 332 (2023): 117354.

- Bird, Robert, Zachary J. Baum, Xiang Yu, and Jia Ma. "The regulatory environment for lithium-ion battery recycling." (2022): 736-740.

- Kallitsis, Evangelos, Anna Korre, and Geoff H. Kelsall. "Life cycle assessment of recycling options for automotive Li-ion battery packs." Journal of Cleaner Production 371 (2022): 133636.

- Koroma, Michael Samsu, Daniele Costa, Maeva Philippot, Giuseppe Cardellini, Md Sazzad Hosen, Thierry Coosemans, and Maarten Messagie. "Life cycle assessment of battery electric vehicles: Implications of future electricity mix and different battery end-of-life management." Science of The Total Environment 831 (2022): 154859.

- Safarian, Sahar. "Environmental and energy impacts of battery electric and conventional vehicles: A study in Sweden under recycling scenarios." Fuel Communications 14 (2023): 100083.

- Castro, Francine Duarte, Eric Mehner, Laura Cutaia, and Mentore Vaccari. "Life cycle assessment of an innovative lithium-ion battery recycling route: A feasibility study." Journal of Cleaner Production 368 (2022): 133130.

- Lai, Xin, Quanwei Chen, Xiaopeng Tang, Yuanqiang Zhou, Furong Gao, Yue Guo, Rohit Bhagat, and Yuejiu Zheng. "Critical review of life cycle assessment of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles: A lifespan perspective." Etransportation 12 (2022): 100169.

- Chigbu, Bianca Ifeoma. "Advancing sustainable development through circular economy and skill development in EV lithium-ion battery recycling: A comprehensive review." Frontiers in Sustainability 5 (2024): 1409498.

- Reinhart, Linda, Dzeneta Vrucak, Richard Woeste, Hugo Lucas, Elinor Rombach, Bernd Friedrich, and Peter Letmathe. "Pyrometallurgical recycling of different lithium-ion battery cell systems: Economic and technical analysis." Journal of Cleaner Production 416 (2023): 137834.

- Ferrarese, Andre, Elio Augusto Kumoto, Luciana Assis Gobo, Amilton Barbosa Botelho Junior, Jorge Alberto Soares Tenório, and Denise Espinosa. Flexible hydrometallurgy process for electric vehicle battery recycling. No. 2022-36-0072. SAE Technical Paper, 2023.

- Wang, Junxiong, Jun Ma, Zhaofeng Zhuang, Zheng Liang, Kai Jia, Guanjun Ji, Guangmin Zhou, and Hui-Ming Cheng. "Toward direct regeneration of spent lithium-ion batteries: a next-generation recycling method." Chemical Reviews 124, no. 5 (2024): 2839-2887.

- Xu, Panpan, Darren HS Tan, Binglei Jiao, Hongpeng Gao, Xiaolu Yu, and Zheng Chen. "A materials perspective on direct recycling of lithium-ion batteries: principles, challenges and opportunities." Advanced Functional Materials 33, no. 14 (2023): 2213168.

- Yang, Tingzhou, Dan Luo, Aiping Yu, and Zhongwei Chen. "Enabling future closed-loop recycling of spent lithium-ion batteries: direct cathode regeneration." Advanced materials 35, no. 36 (2023): 2203218.

- Kay, Ian, Siamak Farhad, Ajay Mahajan, Roja Esmaeeli, and Sayed Reza Hashemi. "Robotic disassembly of electric vehicles’ battery modules for recycling." Energies 15, no. 13 (2022): 4856.

- Slotte, Patrycja, Elina Pohjalainen, Jyri Hanski, and Päivi Kivikytö-Reponen. "Effect of life extension strategies on demand and recycling of EV batteries–material flow analysis of Li and Ni in battery value chain for Finnish EV fleet by 2055." Resources, Conservation and Recycling 215 (2025): 108081.

- Statista. Forecast lithium-ion battery recycling market worldwide from 2023 to 2033. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1330758/lithium-ion-battery-recycling-market-value-worldwide/. (accessed 30.04.2025).

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer et al. "The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews." bmj 372 (2021).

- Bachér, J., J. Laatikainen-Luntama, L. Rintala, and M. Horttanainen. "The distribution of valuable metals in gasification of metal-containing residues from mechanical recycling of end-of-life vehicles and electronic waste." Journal of Environmental Management 373 (2025): 123526.

- Deloitte China, and CAS. Lithium-Ion Battery Recycling: Market & Innovation Trends for a Green Future. 2023. Available at: https://www.cas.org/resources/whitepapers/lithium-ion-battery-recycling. (accessed 30.04.2025).

- Niemi, Tero, Tero Kaarlela, Emilia Niittyviita, Ulla Lassi, and Juha Röning. "CAN Interface Insights for Electric Vehicle Battery Recycling." Batteries 10, no. 5 (2024): 158.

- de Castro, Roberta Hergessel, Denise Crocce Romano Espinosa, Luciana Assis Gobo, Elio Augusto Kumoto, Amilton Barbosa Botelho Junior, and Jorge Alberto Soares Tenorio. "Design of recycling processes for NCA-type Li-ion batteries from electric vehicles toward the circular economy." Energy & Fuels 38, no. 6 (2024): 5545-5557.

- Yang, Hanxue, Xiaocheng Hu, Guanhua Zhang, Binlin Dou, Guomin Cui, Qiguo Yang, and Xiaoyu Yan. "Life cycle assessment of secondary use and physical recycling of lithium-ion batteries retired from electric vehicles in China." Waste Management 178 (2024): 168-175.

- Kasy, Fransisca Indraningsih, Muhammad Hisjam, Wakhid Ahmad Jauhari, and Syed Ahmad Helmi Syed Hassan. "Optimizing the Supply Chain for Recycling Electric Vehicle NMC Batteries." Jurnal Optimasi Sistem Industri 23, no. 2 (2024): 207-226.

- Kamath, Dipti, Sharlissa Moore, Renata Arsenault, and Annick Anctil. "A system dynamics model for end-of-life management of electric vehicle batteries in the US: Comparing the cost, carbon, and material requirements of remanufacturing and recycling." Resources, Conservation and Recycling 196 (2023): 107061.

- Slattery, Margaret, Jessica Dunn, and Alissa Kendall. "Charting the electric vehicle battery reuse and recycling network in North America." Waste Management 174 (2024): 76-87.

- Mu, Nengye, Yuanshun Wang, Zhen-Song Chen, Peiyuan Xin, Muhammet Deveci, and Witold Pedrycz. "Multi-objective combinatorial optimization analysis of the recycling of retired new energy electric vehicle power batteries in a sustainable dynamic reverse logistics network." Environmental science and pollution Research 30, no. 16 (2023): 47580-47601.

- Lee, Hyunseok, Yu-Tack Kim, and Seung-Woo Lee. "Optimization of the electrochemical discharge of spent li-ion batteries from electric vehicles for direct recycling." Energies 16, no. 6 (2023): 2759.

- Kastanaki, Eleni, and Apostolos Giannis. "Dynamic estimation of end-of-life electric vehicle batteries in the EU-27 considering reuse, remanufacturing and recycling options." Journal of Cleaner Production 393 (2023): 136349.

- Tankou, Alexander, Georg Bieker, and Dale Hall. "Scaling up reuse and recycling of electric vehicle batteries: Assessing challenges and policy approaches." In Proc. ICCT, pp. 1-138. 2023.

- Dunn, Jessica, Alissa Kendall, and Margaret Slattery. "Electric vehicle lithium-ion battery recycled content standards for the US–targets, costs, and environmental impacts." Resources, Conservation and Recycling 185 (2022): 106488.

- Lima, Maria Cecília Costa, Luana Pereira Pontes, Andrea Sarmento Maia Vasconcelos, Washington de Araujo Silva Junior, and Kunlin Wu. "Economic aspects for recycling of used lithium-ion batteries from electric vehicles." Energies 15, no. 6 (2022): 2203.

- Yang, Hui, Xiaolong Song, Xihua Zhang, Bin Lu, Dong Yang, and Bo Li. "Uncovering the in-use metal stocks and implied recycling potential in electric vehicle batteries considering cascaded use: a case study of China." Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28, no. 33 (2021): 45867-45878.

- Qiao, Donghai, Gaoshang Wang, Tianming Gao, Bojie Wen, and Tao Dai. "Potential impact of the end-of-life batteries recycling of electric vehicles on lithium demand in China: 2010–2050." Science of the Total Environment 764 (2021): 142835.

- Fu, Yuanpeng, Jonas Schuster, Martina Petranikova, and Burçak Ebin. "Innovative recycling of organic binders from electric vehicle lithium-ion batteries by supercritical carbon dioxide extraction." Resources, conservation and recycling 172 (2021): 105666.

- Yao, Peifan, Xihua Zhang, Zhaolong Wang, Lifen Long, Yebin Han, Zhi Sun, and Jingwei Wang. "The role of nickel recycling from nickel-bearing batteries on alleviating demand-supply gap in China's industry of new energy vehicles." Resources, Conservation and Recycling 170 (2021): 105612.

- Abdelbaky, Mohammad, Jef R. Peeters, and Wim Dewulf. "On the influence of second use, future battery technologies, and battery lifetime on the maximum recycled content of future electric vehicle batteries in Europe." Waste Management 125 (2021): 1-9.

- Lander, Laura, Tom Cleaver, Mohammad Ali Rajaeifar, Viet Nguyen-Tien, Robert JR Elliott, Oliver Heidrich, Emma Kendrick, Jacqueline Sophie Edge, and Gregory Offer. "Financial viability of electric vehicle lithium-ion battery recycling." Iscience 24, no. 7 (2021).

- Sun, Bingxiang, Xiaojia Su, Dan Wang, Lei Zhang, Yingqi Liu, Yang Yang, Hui Liang, Minming Gong, Weige Zhang, and Jiuchun Jiang. "Economic analysis of lithium-ion batteries recycled from electric vehicles for secondary use in power load peak shaving in China." Journal of Cleaner Production 276 (2020): 123327.

- Bat-Orgil, Turmandakh, Bayasgalan Dugarjav, and Toshihisa Shimizu. "Cell equalizer for recycling batteries from hybrid electric vehicles." Journal of Power Electronics 20, no. 3 (2020): 811-822.

- Skeete, Jean-Paul, Peter Wells, Xue Dong, Oliver Heidrich, and Gavin Harper. "Beyond the EVent horizon: Battery waste, recycling, and sustainability in the United Kingdom electric vehicle transition." Energy Research & Social Science 69 (2020): 101581.

- Hoarau, Quentin, and Etienne Lorang. "An assessment of the European regulation on battery recycling for electric vehicles." Energy Policy 162 (2022): 112770.

- Li, Jizi, Fangbing Liu, Justin Z. Zhang, and Zeping Tong. "Optimal configuration of electric vehicle battery recycling system under across-network cooperation." Applied Energy 338 (2023): 120898.

- Sastre, Jose Paulino Peris, Usman Saleem, Erik Prasetyo, and Sulalit Bandyopadhyay. "Resynthesis of cathode active material from heterogenous leachate composition produced by electric vehicle (EV) battery recycling stream." Journal of Cleaner Production 429 (2023): 139343.

- Guzek, Marek, Jerzy Jackowski, Rafał S. Jurecki, Emilia M. Szumska, Piotr Zdanowicz, and Marcin Żmuda. "Electric vehicles—an overview of current issues—Part 1—environmental impact, source of energy, recycling, and second life of battery." Energies 17, no. 1 (2024): 249.

- Tao, Ren, Peng Xing, Huiquan Li, Zhigen Cun, Zhenhua Sun, and Yufeng Wu. "In situ reduction of cathode material by organics and anode graphite without additive to recycle spent electric vehicle LiMn2O4 batteries." Journal of Power Sources 520 (2022): 230827.

- Chaianong, Aksornchan, Chanathip Pharino, Sabine Langkau, Pimpa Limthongkul, and Nattanai Kunanusont. "Pathways for enhancing sustainable mobility in emerging markets: Cost-benefit analysis and policy recommendations for recycling of electric-vehicle batteries in Thailand." Sustainable Production and Consumption 47 (2024): 1-16.

- Adaikkappan, Maheshwari, and Nageswari Sathiyamoorthy. "Modeling, state of charge estimation, and charging of lithium-ion battery in electric vehicle: a review." International Journal of Energy Research 46, no. 3 (2022): 2141-2165.

- Fallah, Narjes, and Colin Fitzpatrick. "Exploring the state of health of electric vehicle batteries at end of use; hierarchical waste flow analysis to determine the recycling and reuse potential." Journal of Remanufacturing 14, no. 1 (2024): 155-168.

- Gonzales-Calienes, Giovanna, Ben Yu, and Farid Bensebaa. "Development of a reverse logistics modeling for end-of-life lithium-ion batteries and its impact on recycling viability—A case study to support end-of-life electric vehicle battery strategy in Canada." Sustainability 14, no. 22 (2022): 15321.

- Safarzadeh, Hamid, and Francesco Di Maria. "How to Fit Energy Demand Under the Constraint of EU 2030 and FIT for 55 Goals: An Italian Case Study." Sustainability 17, no. 8 (2025): 3743.

- Nie, Shuai, Guotian Cai, Yuping Huang, and Jiaxin He. "Deciphering stakeholder strategies in electric vehicle battery recycling: Insights from a tripartite evolutionary game and system dynamics." Journal of Cleaner Production 452 (2024): 142174.

- Zhu, Jianhua, Taiwen Feng, Ying Lu, and Runze Xue. "Optimal government policies for carbon–neutral power battery recycling in electric vehicle industry." Computers & Industrial Engineering 189 (2024): 109952.

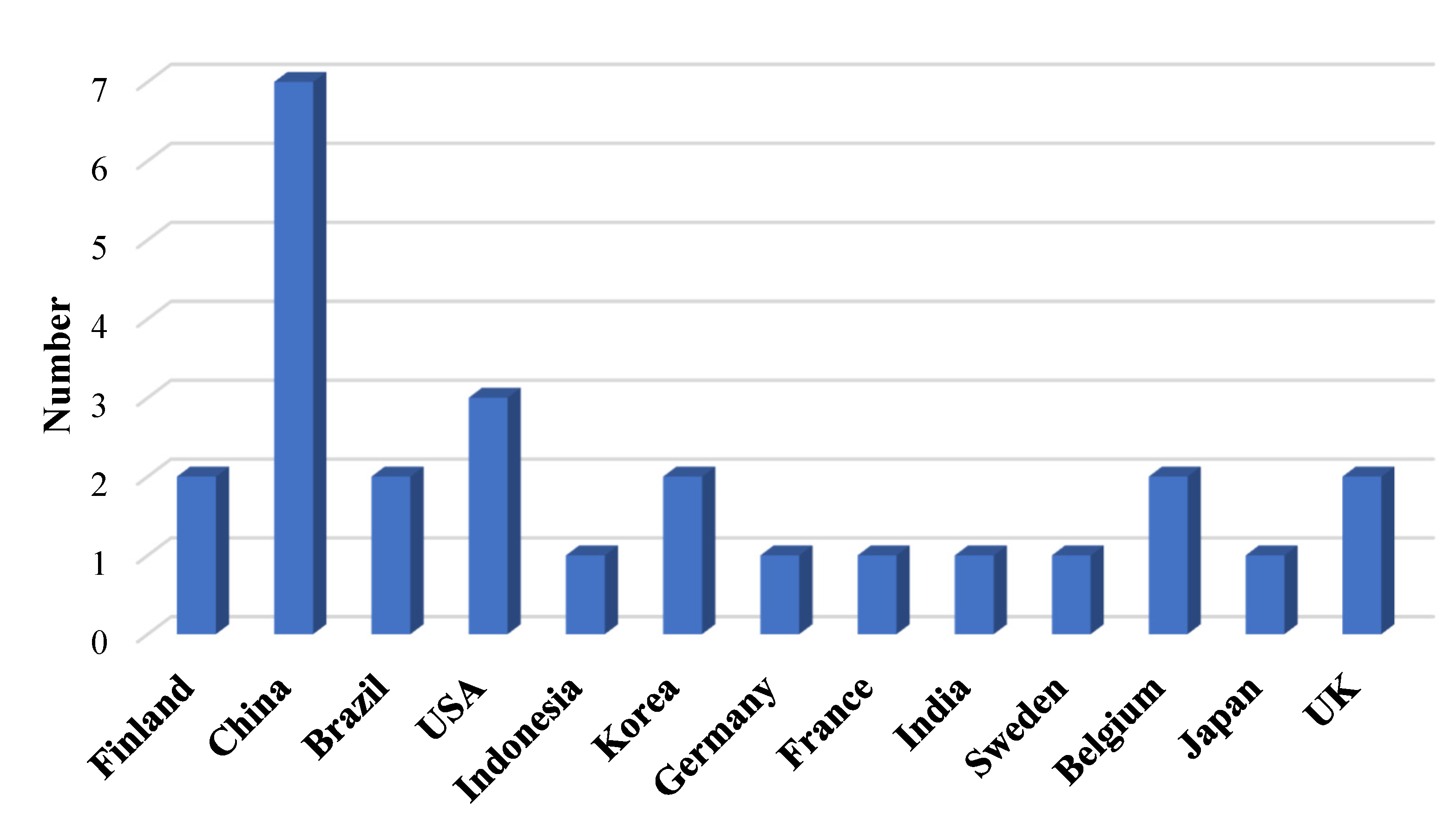

| Ref | Title | country | Methodology | Main Focus | Key funding | Year |

| [45] | The distribution of valuable metals in gasification of metal-containing residues from mechanical recycling of end-of-life vehicles and electronic waste | Finland | Experimental | Recycling of metal-containing wastes such as end-of-life vehicles (ELV) | The gasification abled to remove the organic matter efficiently and liberate metals. | 2025 |

| [46] | Deloitte China, and CAS. Lithium-Ion Battery Recycling: Market & Innovation Trends for A Green Future | China | Simulation | The future of recycling of Li-ion Batteries in China | - | 2025 |

| [47] | CAN Interface Insights for Electric Vehicle Battery Recycling | Finland | Simulation | Controller Area Network Interface Insights for Electric Vehicle Battery Recycling | - | 2024 |

| [48] | Design of Recycling Processes for NCA-Type Li-Ion Batteries from Electric Vehicles toward the Circular Economy | Brazil | Experimental | Hydrometallurgical recycling process of NCA cylindrical batteries | 92% of Li, 80% of Ni, and 85% of Co can be recovered in hydrometallurgical processing | 2024 |

| [49] | Life cycle assessment of secondary use and physical recycling of lithium-ion batteries retired from electric vehicles in China | China | Experimental | LCA of secondary use and physical recycling of lithium-ion batteries | Secondary use has the greatest impact on assessment results in dynamic situations. | 2024 |

| [50] | Optimizing the Supply Chain for Recycling Electric Vehicle NMC Batteries | Indonesia | Simulation | Optimizing the Supply Chain for Recycling EV Batteries | - | 2024 |

| [51] | A system dynamics model for end-of-life management of electric vehicle batteries in the US: Comparing the cost, carbon, and material requirements of remanufacturing and recycling | USA | Simulation | End-of-life management of electric vehicle batteries | Remanufacturing can reduce the carbon footprint of the EV battery life cycle. | 2024 |

| [52] | Charting the electric vehicle battery reuse and recycling network in North America | USA | Simulation | Electric vehicle battery reuse and recycling network in North America | EV and EV battery EoL is market-driven system, relying on profitability. | 2024 |

| [53] | Multi-objective combinatorial optimization analysis of the recycling of retired new energy electric vehicle power batteries in a sustainable dynamic reverse logistics network | China | Simulation | Explore the layout of the sustainable reverse logistics network for batteries recycling | The dynamic reverse logistics network is superior to its static counterpart | 2023 |

| [54] | Optimization of the Electrochemical Discharge of Spent Li-Ion Batteries from Electric Vehicles for Direct Recycling | Korea | Experimental | Optimization of the Electrochemical Discharge of Spent Li-Ion Batteries | The process will be suitable for the direct recycling of spent LIBs | 2023 |

| [55] | Dynamic estimation of end-of-life electric vehicle batteries in the EU-27 considering reuse, remanufacturing and recycling options | Germany - France | Simulation | Dynamic estimation of end-of-life electric vehicle batteries | The recycled metals could meet 5.2–11.3% of the demand for EU Battery Directive | 2023 |

| [56] | Scaling up reuse and recycling of electric vehicle batteries: Assessing challenges and policy approaches | India | Experimental | Challenges and policy approaches | - | 2023 |

| [57] | Electric vehicle lithium-ion battery recycled content standards for the US – targets, costs, and environmental impacts | USA | Simulation | Electric vehicle lithium-ion battery recycled content standards for the US | Recycling US EV retirements domestically is more expensive than recycling in China | 2022 |

| [58] | Economic Aspects for Recycling of Used Lithium-Ion Batteries from Electric Vehicles | Brazil | Simulation | Factors that influence the economic feasibility of disposing of batteries | A business model is created for recycling LIBs in Brazil | 2022 |

| [59] | Uncovering the in-use metal stocks and implied recycling potential in electric vehicle batteries considering cascaded use: a case study of China | China | - | Recycling potential in electric vehicle batteries | Increasing recycling potential by 2030 | 2021 |

| [60] | Potential impact of the end-of-life batteries recycling of electric vehicles on lithium demand in China: 2010–2050 | China | Simulation | Potential impact of batteries recycling on lithium demand in China | The recovered lithium could meet 60% of the lithium demand for LIBs produced by 2050. | 2021 |

| [61] | Innovative recycling of organic binders from electric vehicle lithium-ion batteries by supercritical carbon dioxide extraction | Sweden | Experimental | Innovative recycling of organic binders | Recovered PVDF remained the same surficial chemical properties as the raw sample. | 2021 |

| [62] | The role of nickel recycling from nickel-bearing batteries on alleviating demand-supply gap in China's industry of new energy vehicles | China | Simulation | Nickel recycling from nickel-bearing batteries | Recovered nickel is likely to play vital role for closing nickel loop in the industry of NEVs in China. | 2021 |

| [63] | On the influence of second use, future battery technologies, and battery lifetime on the maximum recycled content of future electric vehicle batteries in Europe | Belgium | Simulation | A novel forecasting model is developed to include second-use of vehicle batteries. | Cobalt content of recycled EV batteries may fulfil 91% of Europe’s 2040 EV demand. | 2021 |

| [64] | Financial viability of electric vehicle lithium-ion battery recycling | UK- Belgium- USA- South Korea- China | Simulation | Comprehensive techno-economic cost model for electric vehicle battery recycling | Economies of scale and battery materials are decisive for recycling profits | 2021 |

| [65] | Economic analysis of lithium-ion batteries recycled from electric vehicles for secondary use in power load peak shaving in China | China | - | A novel cost-benefit modelfor battery energy storage system of recycled Li-ion batteries | - | 2020 |

| [66] | Cell equalizer for recycling batteries from hybrid electric vehicles | Japan | Experimental | Cell equalizer for recycling | - | 2020 |

| [67] | Beyond the EVent horizon: Battery waste, recycling, and sustainability in the United Kingdom electric vehicle transition | UK | Simulation | Recycling, and sustainability in the United Kingdom electric vehicle | Sustainable recycling solutions will require sustainable business models. | 2020 |

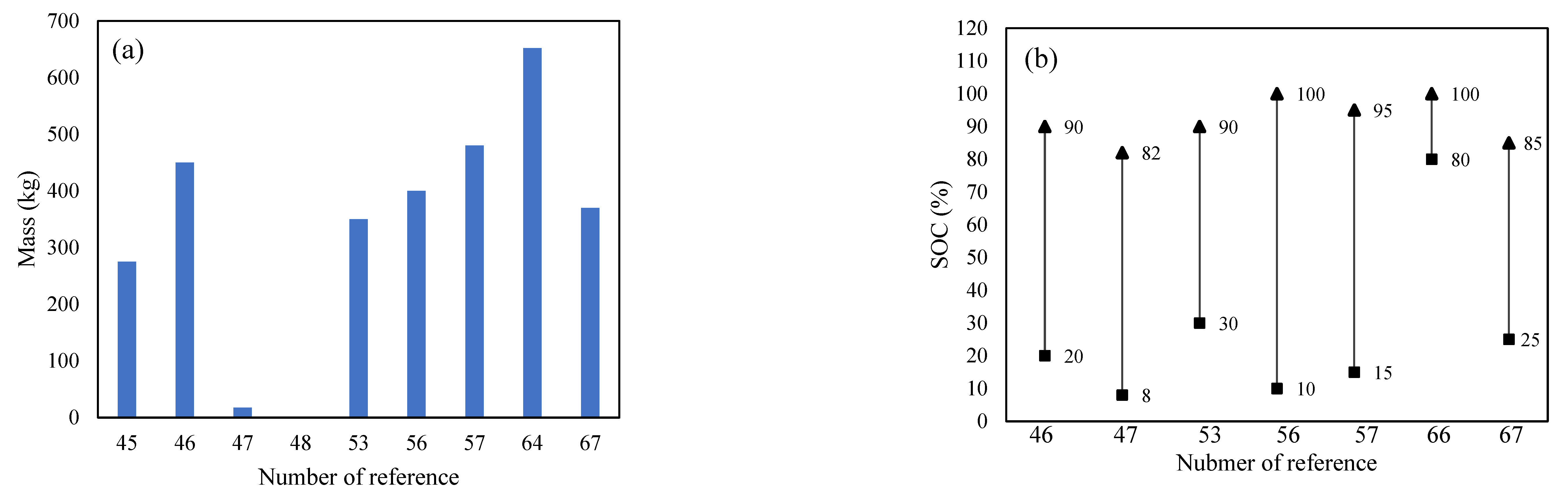

| Ref | Battery type | EV/HEV | Energy | Voltage (V) | Current (A) | Peak current (A) | Capacity (Ah) | Mass (kg) | Number of Cells | Min SOC (%) | Max SOC (%) | Process. time (min) | Charge time (min) | Temp. (C) | pH | Rec. Li (%) |

Rec. Ni (%) |

Rec. Co (%) |

Rec. cost |

| [45] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 150 - 400 | - | - | - | - | - | 415 - 885 | - | - | - | - | - |

| [46] | Li-ion (NMC) | EV | 65 | 400 | 150 | 300 | 162.5 | 450 | 96 | 20 | 90 | 120 | 45 | 25 | 7 | 95 | 90 | 85 | 1,000 /ton |

| [47] | Li-ion | HEV | 430 Wh | 48 | 75 | 250 | 9.8 | 17.5 | 16 | 8 | 82 | - | 110 | 23 - 65 | - | - | - | - | - |

| [48] | Li-ion | EV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 30 - 180 | - | 25 - 90 | 1-3.5 | 91.6 | 80.3 | 85 | - |

| [49] | Li-ion | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [50] | NMC | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 128,000 IDR/kg |

| [51] | LiCoO2 (LCO) | EV | 0.175 kWh/kg | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 95 | 95 | 95 | - |

| LiMn2O4 (LMO) | EV | 0.125 kWh/kg | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| LiF2PO4 (LFP) | EV | 0.105 kWh/kg | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| NMC 111 |

EV | 0.185 kWh/kg | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| NMC 622 |

EV | 0.185 kWh/kg | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| NMC 811 |

EV | 0.185 kWh/kg | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| LiNiCoAlO2 (NCA) | EV | 0.3 kWh/kg | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| [53] | NiMH | HEV | 40 | 300 | 120 | 240 | 133.3 | 350 | 80 | 30 | 90 | 90 | 35 | 25 | 6.8 | 75 | 65 | 55 | 800 /ton |

| [54] | SM3 ZEs | EV | 35.9 kWh | 360 | - | - | 74 | - | 192 | - | - | 24 (h) | - | 40 | - | - | - | - | - |

| [55] | NCA | EV / HEV |

8.6 - 72 kWh | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| LMO | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| LFP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| NMC 811 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| NMC 622 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| NMC 111 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| NMC 955 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| NMC 532 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| [56] | Li-ion (LFP) | EV | 50 | 350 | 140 | 280 | 142.9 | 400 | 90 | 10 | 100 | 100 | 40 | 30 | 6.5 | 80 | 70 | 60 | 900 /ton |

| [57] | Li-ion (NCA) | EV | 70 | 420 | 160 | 320 | 166.7 | 480 | 100 | 15 | 95 | 130 | 50 | 35 | 7.2 | 92 | 88 | 83 | 1,100 /ton |

| [58] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 33.79 /kWh |

| [59] | NMC | EV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| LFP | EV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| LMO | EV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [60] | LFP-G | EV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 49-60 | - | - | - |

| NMC-G | EV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| NCA-G | EV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Li-S | EV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Li-Air | EV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| [61] | ALB | EV | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 - 17 | - | - | - | 97.5 | - | - | - |

| [62] | NCA | EV / HEV |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| NCM 111 |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| NCM 523 |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| NCM 622 |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| NCM 811 |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| [63] | Li-Iron Phosphate | EV / HEV |

- | - | - | - | 44 - 60 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| LMO | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| LMO blend | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| NMC 111 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| NMC 532 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| NMC 622 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| NMC 811 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Li-Ni-Co-AlO3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Advanced and beyond li-ion | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| [64] | NCA | EV / HEV |

24 - 93 kWh | - | - | - | - | 295 - 1,009 | 192 - 10,368 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 90 | 98 | 98 | 10.55 - 21.9 /kWh |

| NMC 622 |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3.51-14.86 /kWh |

||||||||

| NMC 811 |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.43-12.77 /kWh |

||||||||

| LFP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0-10.77 /kWh |

||||||||

| LMO | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0-9.15 /kWh |

||||||||

| [65] | Li-ion | EV | - | 3.2 | 0.5 | - | 50 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.45 CNY/Wh |

| [66] | NiMH | HEV | - | 14.37 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 3.3 | - | - | 80 | 100 | 110 | 90 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [67] | Li-ion (LTO) | HEV | 45 | 360 | 130 | 260 | 125 | 370 | 85 | 25 | 85 | 110 | 42 | 28 | 6.9 | 78 | 68 | 58 | 950 /ton |

| Ref | C | H | N | O | Al | Cu | Fe | Sn | Zn | Ag | Au | Pd | Dy | Nd | Li | Ni | Co | Mn |

| [45] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||

| [47] | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||||

| [48] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| [49] | * | * | * | |||||||||||||||

| [50] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| [51] | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||||

| [53] | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||||||

| [54] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| [55] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| [58] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| [59] | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||||

| [60] | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||||

| [61] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| [62] | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||||||

| [63] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Ref | C (%) | Al (%) | Cu (%) | Fe (%) | Ag (%) | Au (%) | Pd (%) | Li (%) | Ni (%) | Co (%) | Mn (%) |

| [45] | - | 3 | 4.4 | 18.2 | 0.001 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | 1.5 | 21.6 | 6.1 | 0.06 | 0.0151 | 24.3 | - | - | - | - | |

| - | 1.1 | 6 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.393 | 71.9 | - | - | - | - | |

| [48] | 1.6 | 36.6 | - | - | - | - | - | 4.2 | 30.3 | 5.2 | - |

| [49] | 22.44 | 8.76 | 9.83 | - | - | - | - | - | 5.74 | 2.3 | 3.22 |

| [50] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 22 | 22 | 20 |

| [51] | - | 0.304 (kg/kWh) | 0.426 (kg/kWh) |

0.963 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | 0.119 (kg/kWh) |

0.071 (kg/kWh) |

0.01 (kg/kWh) |

- |

| - | 0.075 (kg/kWh) |

0.075 (kg/kWh) |

1.105 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | 0.104 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | 1.37 (kg/kWh) |

|

| - | 0.457 (kg/kWh) |

0.571 (kg/kWh) |

2.53 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | 0.084 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | |

| - | 0.263 (kg/kWh) |

0.390 (kg/kWh) |

0.866 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | 0.139 (kg/kWh) |

0.367 (kg/kWh) |

0.394 (kg/kWh) |

0.392 (kg/kWh) |

|

| - | 0.263 (kg/kWh) |

0.390 (kg/kWh) |

0.866 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | 0.126 (kg/kWh) |

0.2 (kg/kWh) |

0.214 (kg/kWh) |

0.641 (kg/kWh) |

|

| - | 0.263 (kg/kWh) |

0.390 (kg/kWh) |

0.866 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | 0.111 (kg/kWh) |

0.088 (kg/kWh) |

0.094 (kg/kWh) |

0.75 (kg/kWh) |

|

| - | 0.379 (kg/kWh) |

0.758 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.112 (kg/kWh) |

0.759 (kg/kWh) |

0.143 (kg/kWh) |

- | |

| [55] | - | - | 0.76 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.1 (kg/kWh) |

0.67 (kg/kWh) |

0.13 (kg/kWh) |

- |

| - | - | 0.96 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.11 (kg/kWh) |

0.07 (kg/kWh) |

0.07 (kg/kWh) |

- | |

| - | - | 0.9 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.1 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | |

| - | - | 0.77 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.11 (kg/kWh) |

0.75 (kg/kWh) |

0.09 (kg/kWh) |

- | |

| - | - | 0.76 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.13 (kg/kWh) |

0.61 (kg/kWh) |

0.19 (kg/kWh) |

- | |

| - | - | 0.82 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.15 (kg/kWh) |

0.4 (kg/kWh) |

0.4 (kg/kWh) |

- | |

| - | - | 0.76 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.1 (kg/kWh) |

0.7 (kg/kWh) |

0.04 (kg/kWh) |

- | |

| - | - | 0.8 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.14 (kg/kWh) |

0.59 (kg/kWh) |

0.23 (kg/kWh) |

- | |

| [59] | - | 5.26 | 7.8 | - | - | - | - | 1.14 | 9.46 | 9.67 | 9.03 |

| - | 6.25 | 8.15 | 9.71 | - | - | - | 1.21 | - | - | - | |

| - | 1.12 | 1.12 | - | - | - | - | 1.54 | - | - | 20.38 | |

| [60] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 176.3 (g/kWh) |

- | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 113.15 (g/kWh) |

- | - | - | |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 239.0 (g/kWh) |

- | - | - | |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 410.5 (g/kWh) |

- | - | - | |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 138.0 (g/kWh) |

- | - | - | |

| [61] | - | 0.06 | - | - | - | - | - | 5.91 | 11.5 | 11.7 | 26.02 |

| [62] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.112 (kg/kWh) |

0.759 (kg/kWh) |

0.143 (kg/kWh) |

0 |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.139 (kg/kWh) |

0.392 (kg/kWh) |

0.394 (kg/kWh) |

0.367 (kg/kWh) |

|

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.134 (kg/kWh) |

0.564 (kg/kWh) |

0.263 (kg/kWh) |

0.316 (kg/kWh) |

|

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.126 (kg/kWh) |

0.641 (kg/kWh) |

0.214 (kg/kWh) |

0.2 (kg/kWh) |

|

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.111 (kg/kWh) |

0.75 (kg/kWh) |

0.094 (kg/kWh) |

0.088 (kg/kWh) |

|

| [63] | 1.19 (kg/kWh) |

- | 0.9 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.1 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | |

| 1.04 (kg/kWh) |

- | 0.96 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.1 | - | - | ||

| 1.04 (kg/kWh) |

- | 0.96 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.11 (kg/kWh) |

0.07 (kg/kWh) |

0.07 (kg/kWh) |

||

| 1.1 (kg/kWh) |

- | 0.82 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.15 (kg/kWh) |

0.4 (kg/kWh) |

0.4 (kg/kWh) |

||

| 1.09 (kg/kWh) |

- | 0.8 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.14 (kg/kWh) |

0.59 (kg/kWh) |

0.23 (kg/kWh) |

||

| 1.06 (kg/kWh) |

- | 0.76 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.13 (kg/kWh) |

0.61 (kg/kWh) |

0.19 (kg/kWh) |

||

| 1.06 (kg/kWh) |

- | 0.77 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.11 (kg/kWh) |

0.75 (kg/kWh) |

0.09 (kg/kWh) |

||

| 1.08 (kg/kWh) |

- | 0.76 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.1 (kg/kWh) |

0.67 (kg/kWh) |

0.13 (kg/kWh) |

||

| - | - | 0.6 (kg/kWh) |

- | - | - | - | 0.22 (kg/kWh) |

- | - |

| Ref | Al | Cu | Fe | Li | Ni | Co | Mn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [49] | - | - | - | - | 208,000 (IDR/kg) | 832,000 (IDR/kg) | 48,000 (IDR/kg) |

| [50] | 2.6 ( /kg) |

9.1 ( /kg) |

0.435 ( /kg) |

70.29 ( /kg) |

13 ( /kg) |

49 ( /kg) |

0.0052( /kg) |

| [58] | 2,658 ( /Ton) |

9,688 ( /Ton) |

90.5 ( /Ton) |

30,930 ( /Ton) |

20,171( /Ton) |

61,550( /Ton) |

5.4 ( /Ton) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).