Submitted:

01 May 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Test Area

2.2. Datasets

2.2.1. Hyperspectral Data

2.2.2. Microwave Backscatter Data

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. A General Technical Framework for Estimating the Backscatter Coefficients of Endmembers within Mixed Pixels

2.3.2. Acquisition of Pure Endmember and Corresponding Spectral Features

2.3.3. Fully Constrained Least Squares (FCLS) Spectral Unmixing Model

2.3.4. Development of the MBCD Model

2.3.5. Sub-Pixel-Level Backscattering Contributions Estimation

2.3.6. Verification Scheme of Backscattering Contributions Estimation

3. Results

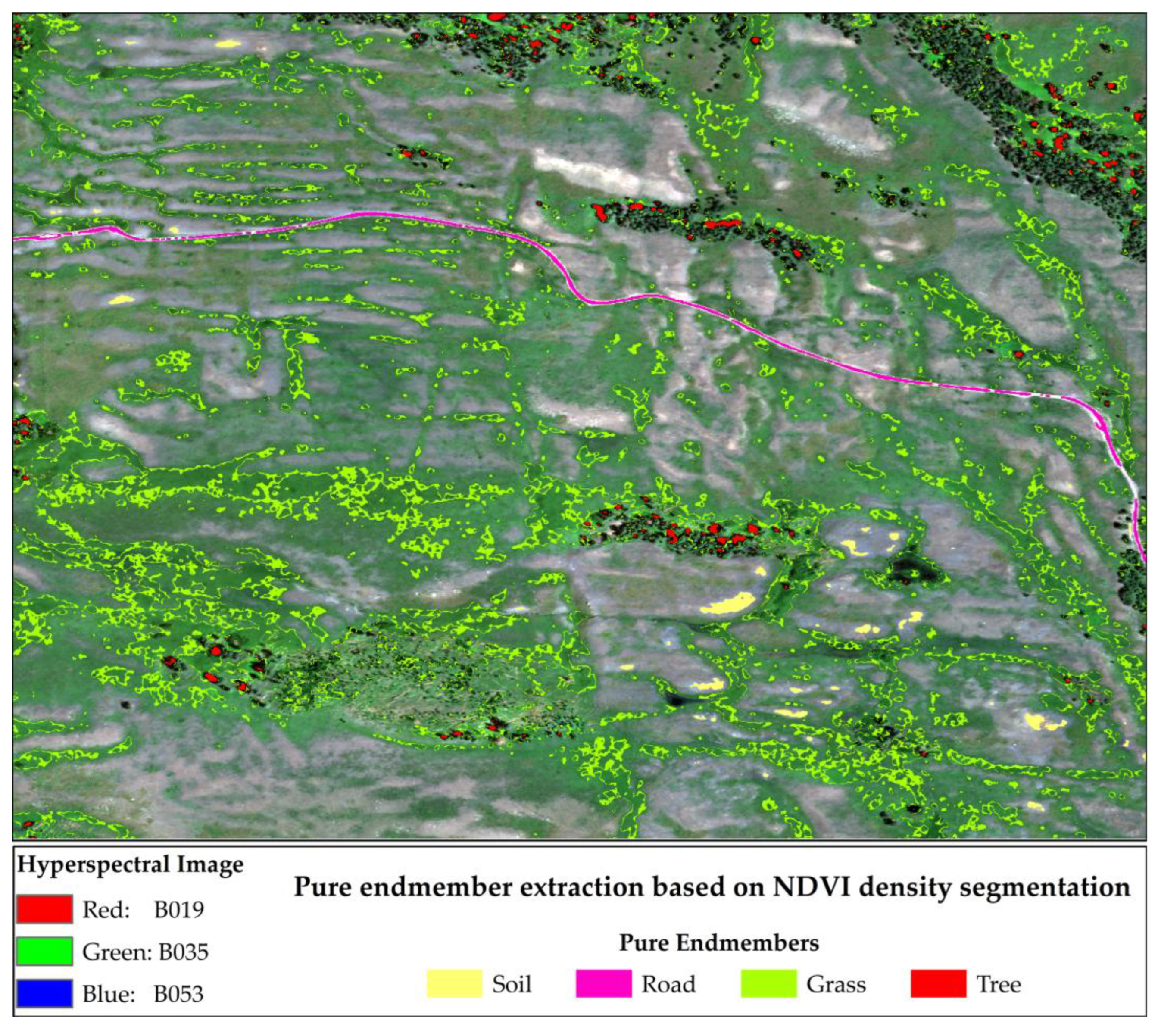

3.1. Pure Endmember Extraction

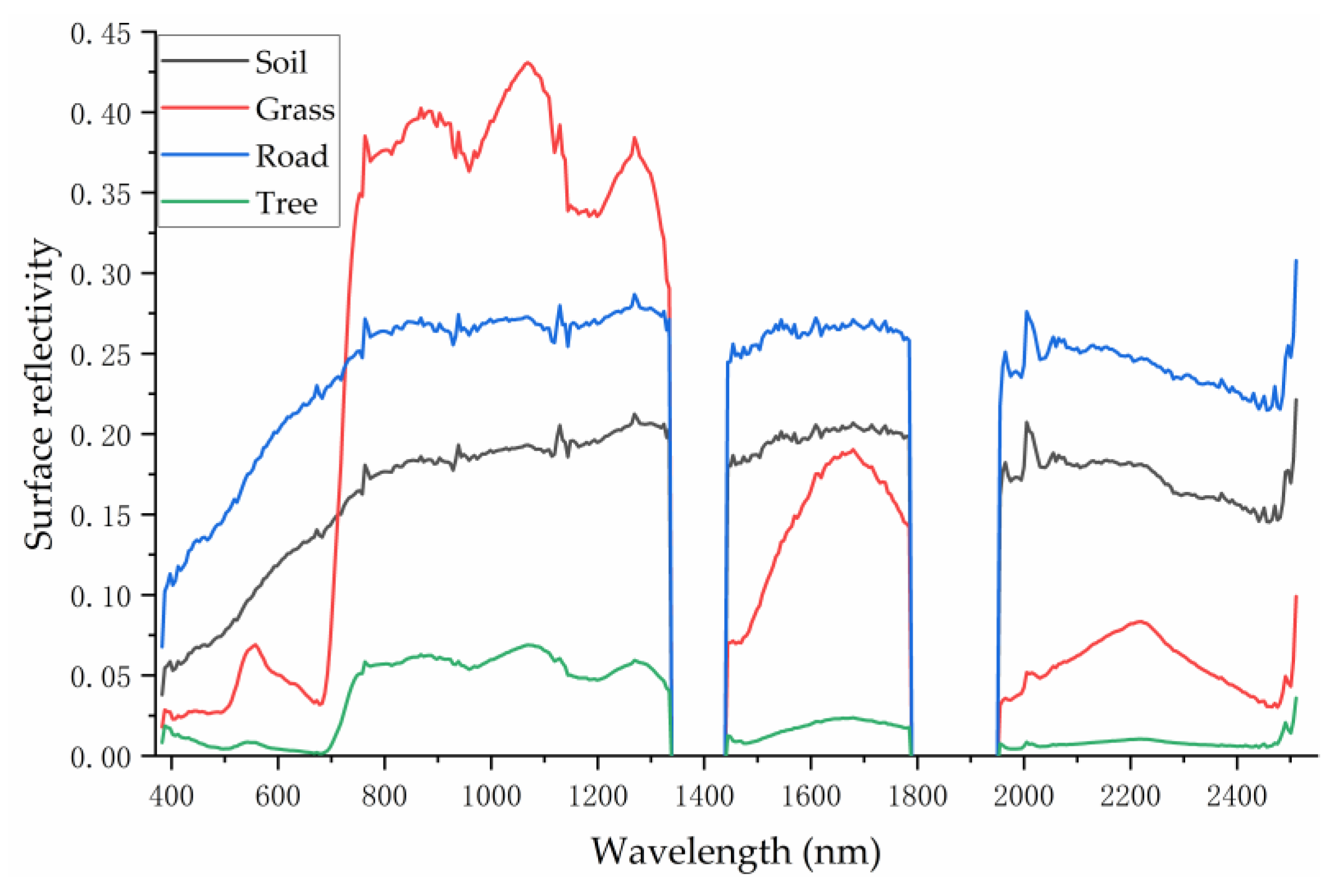

3.2. Pure Endmember Spectral Features

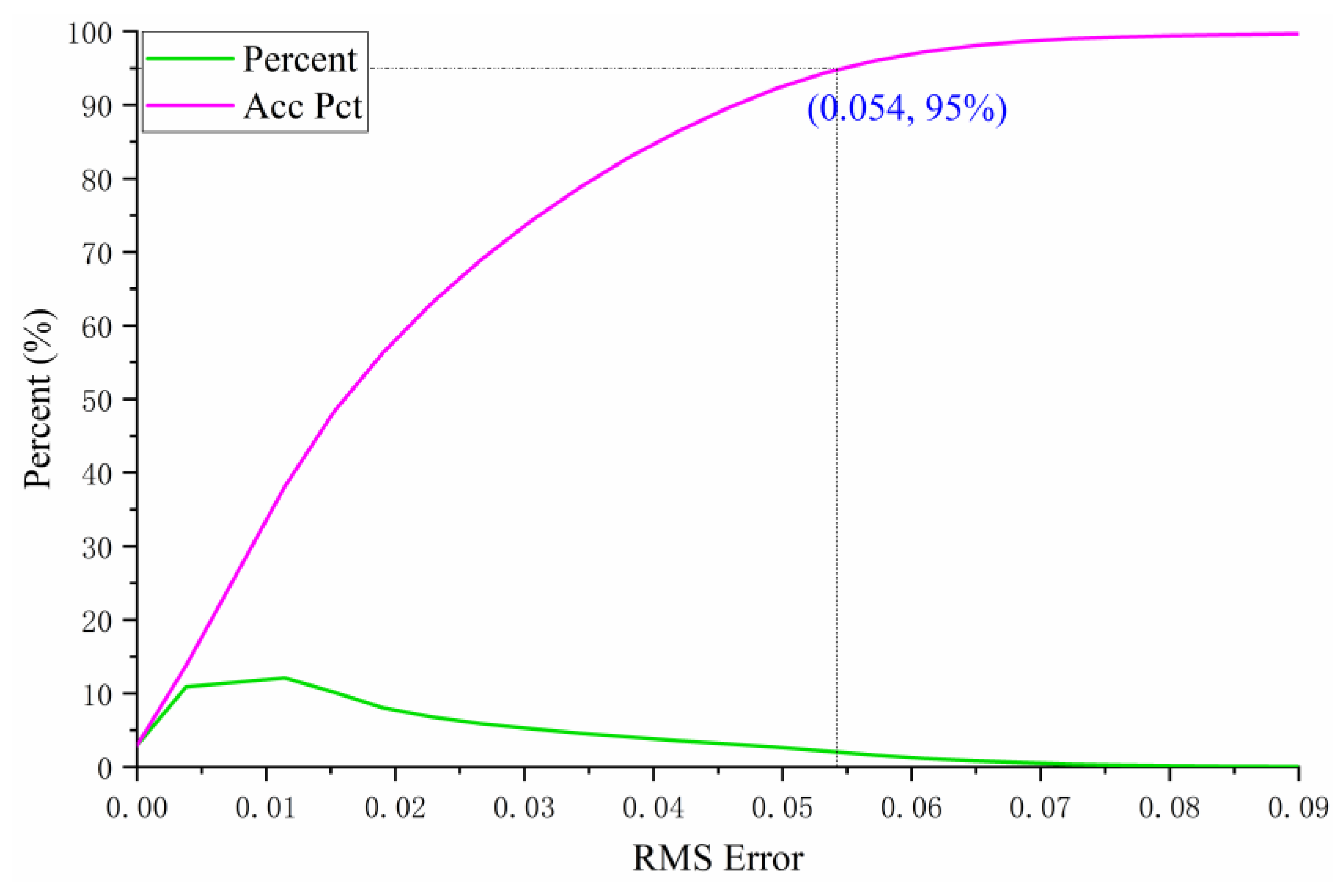

3.3. Abundance of Pure End Members

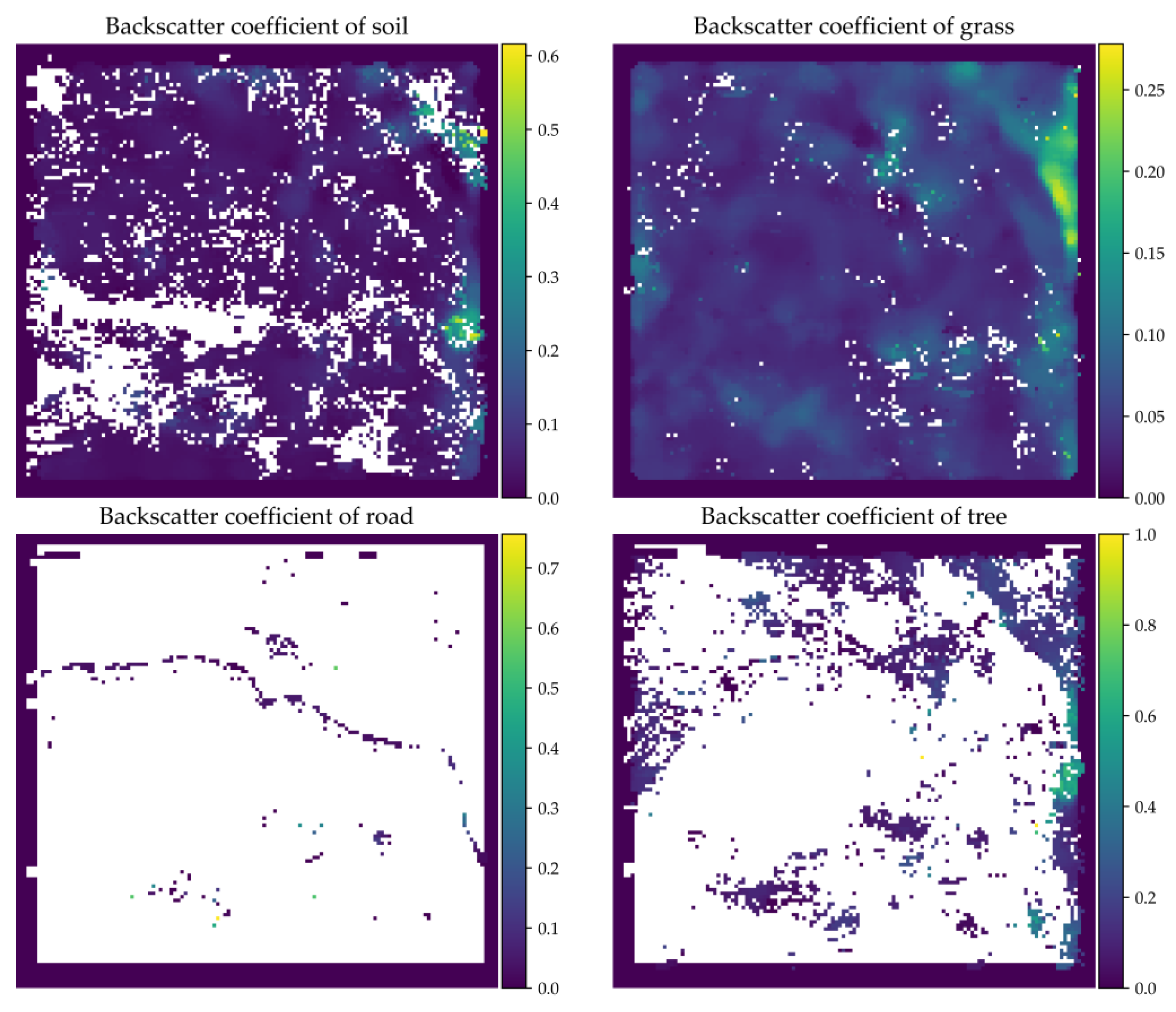

3.4. Endmember Backscattering Coefficient

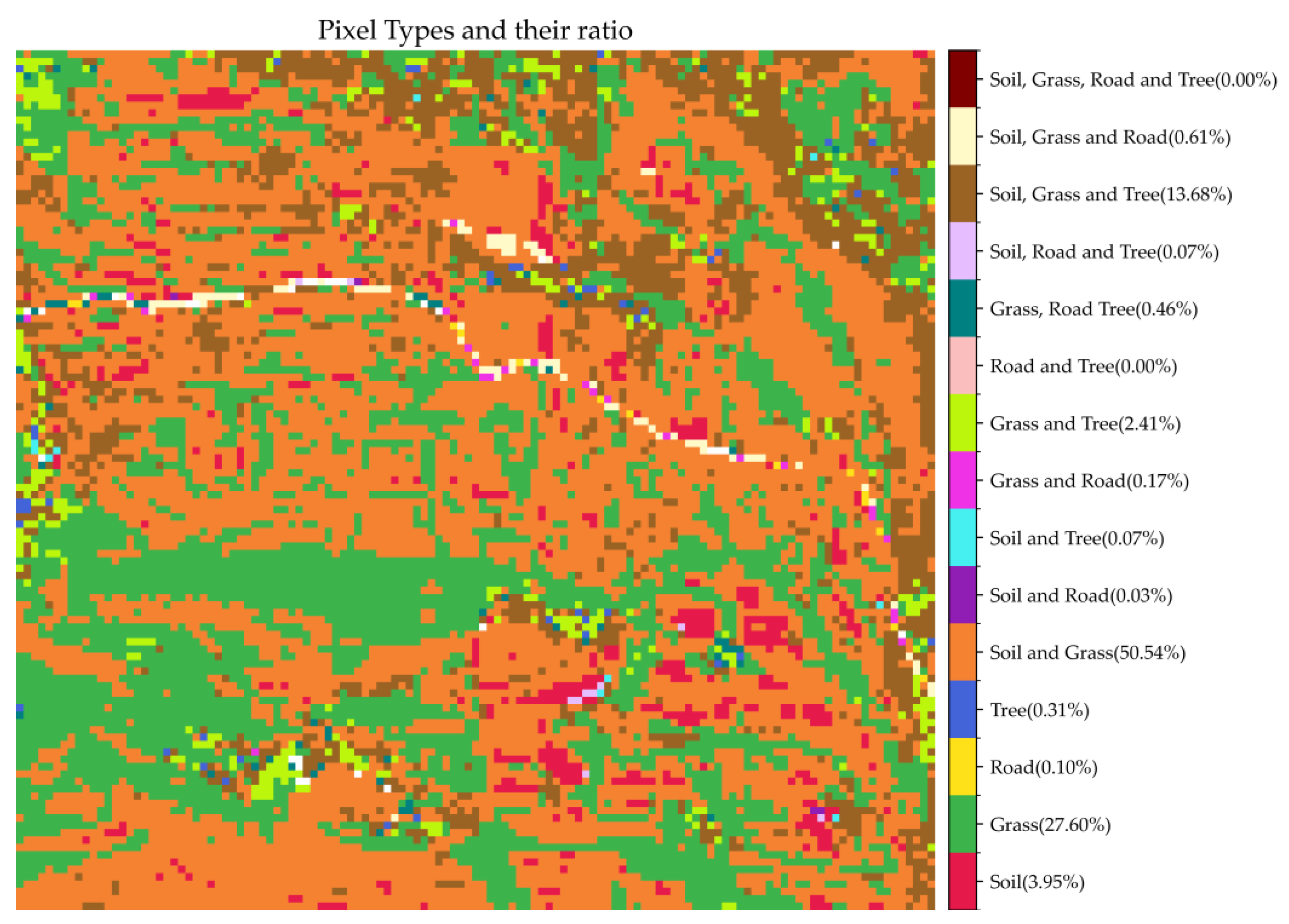

3.4. Endmember Types of the Test Area

3.5. Verification of the Estimated End-Member Backscattering Coefficients

4. Discussion

4.1. Accuracy of Endmember Abundance Estimation

4.2. Evaluation of Endmember Backscattering Coefficient Estimation

4.3. Application Prospects and Future Work of This Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

- The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SAR | synthetic aperture radar |

| DVP | Depolarized Volume Power |

| AVP | Anisotropic Volume Power |

| LAI | Leaf Area Index |

| PPI | Pixel Purity Index |

| NEON | National Ecological Observatory Network |

| AOP | Airborne Observation Platform |

| VSWIR | visible to shortwave infrared |

| QA | quality assurance |

| BRDF | Bidirectional Reflectance Distribution Function |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| GRD | Ground Range Detected |

| SRTM | Shuttle Radar Topography Mission |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| dB | decibel |

| SVD | singular value decomposition |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| FCLS | Fully Constrained Least Squares |

| RMSE | root mean square error |

References

- Zhang, Z.J.; Wang, M.; Qi, Y.J.; Su, X.Q.; Kong, D. Deep Learning-Based Methods for Lithology Classification and Identification in Remote Sensing Images. Ieee Access 2025, 13, 3038–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Pan, M.; Miralles, D.G.; Reichle, R.H.; Dorigo, W.A.; Hahn, S.; Sheffield, J.; Karthikeyan, L.; Balsamo, G.; Parinussa, R.M.; et al. Evaluation of 18 satellite- and model-based soil moisture products using in situ measurements from 826 sensors. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2021, 25, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, W.D.; Reis, L.G.D.; Ruiz-Armenteros, A.M.; Veleda, D.; Neto, A.R.; Fragoso, C.R., Jr.; Cabral, J.; Montenegro, S. Analysis of Environmental and Atmospheric Influences in the Use of SAR and Optical Imagery from Sentinel-1, Landsat-8, and Sentinel-2 in the Operational Monitoring of Reservoir Water Level. Remote Sensing 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.F.; Cai, X.M.; Xing, J.; Li, Z.H.; Zhu, W.; Yuan, Z.H.; Fang, Z.H. Towards transparent deep learning for surface water detection from SAR imagery. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2023, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.N.; Wang, B.Y.; Qian, X.J.; Gu, Y.H.; Jin, G.D.; Yang, R. Enhancing Water Extraction for Dual-Polarization SAR Images Based on Adaptive Feature Fusion and Hybrid MLP Network. Ieee Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2025, 18, 6953–6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian, J.; Sagan, V.; Maimaitijiang, M. Sentinel SAR-optical fusion for crop type mapping using deep learning and Google Earth Engine. Isprs Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2021, 175, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Zhang, R.; Lv, J.C.; Wu, R.Z.; Zhang, H.S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, B.; Ouyang, X.Y.; Liu, G.X. Vegetation descriptors from Sentinel-1 SAR data for crop growth monitoring. Isprs Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2023, 203, 86–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, F.; Ferreira, M.P.; Almeida, C.A.; Feitosa, R.Q. Fusing Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Images for Deforestation Detection in the Brazilian Amazon Under Diverse Cloud Conditions. Ieee Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Shu, H.; Li, Q.T.; Altan, O.; Khan, M.R.; Baqa, M.F.; Lu, L.L. Quantitative Analysis of Forest Fires in Southeastern Australia Using SAR Data. Remote Sensing 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, E.M.; Twele, A.; Martinis, S. The Effect of Vegetation Type and Density on X-Band SAR Backscatter after Forest Fires. Photogrammetrie Fernerkundung Geoinformation 2014, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoray, T.; Shoshany, M.; Curran, P.J.; Foody, G.M.; Perevolotsky, A. Relationship between green leaf biomass volumetric density and ERS-2 SAR backscatter of four vegetation formations in the semi-arid zone of Israel. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2001, 22, 1601–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.H.; Huang, J.; He, X.F.; Luo, Z.C.; Wang, H.H. Coastal Mean Dynamic Topography Recovery Based on Multivariate Objective Analysis by Combining Data from Synthetic Aperture Radar Altimeter. Remote Sensing 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solórzano, J.V.; Mas, J.F.; Gao, Y.; Gallardo-Cruz, J.A. Land Use Land Cover Classification with U-Net: Advantages of Combining Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Imagery. Remote Sensing 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chang, L.; Wang, M.S.; Stein, A. Measuring polycentric urban development with multi-temporal Sentinel-1 SAR imagery: A case study in Shanghai, China. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2023, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.J.; Li, X.M.; Busche, T.; Shi, L.J. X- and C-Band SAR Signatures of Sea Ice in the Bohai Sea. Ieee Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokr, M.; Dabboor, M. Polarimetric SAR Applications of Sea Ice: A Review. Ieee Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2023, 16, 6627–6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ye, Y.F.; Wang, S.Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, Z.Q.; Cheng, X. Evaluation of the AMSR2 Ice Extent at the Arctic Sea Ice Edge Using an SAR-Based Ice Extent Product. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.; Durden, S.L. A three-component scattering model for polarimetric SAR data. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 1998, 36, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Moriyama, T.; Ishido, M.; Yamada, H. Four-component scattering model for polarimetric SAR image decomposition. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2005, 43, 1699–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Rajendra, P.; Vivek, T.; and Srivastava, P.K. An improved volume power approach to estimate LAI from optimized dual-polarized SAR decomposition. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2023, 44, 5736–5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, T.L.; Wang, Y.T.; Lee, J.S. Model-Based Polarimetric SAR Decomposition: An <i>L</i><sub>1</sub> Regularization Approach. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloude, S.R.; Pottier, E.J.I.t.o.g.; sensing, r. A review of target decomposition theorems in radar polarimetry. 1996, 34, 498-518.

- van Zyl, J. Application of Cloude's target decomposition theorem to polarimetric imaging radar data; SPIE: 1993; Volume 1748.

- Song, Y.; Zheng, H.; Chen, X.; Bao, A.; Lei, J.; Xu, W.; Luo, G.; Guan, Q. Desertification Extraction Based on a Microwave Backscattering Contribution Decomposition Model at the Dry Bottom of the Aral Sea. 2021, 13, 4850.

- Dennison, P.E.; Roberts, D.A. Endmember selection for multiple endmember spectral mixture analysis using endmember average RMSE. Remote Sensing of Environment 2003, 87, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehalli, Z.; Zigh, E.; Loukil, A.; Pacha, A.A. A new iterative endmember extraction and spectral matching approach to improve the accuracy of mineral identification and mapping. Signal Image and Video Processing 2025, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, P.; Polonen, I.; Salmi, P. Blind and endmember guided autoencoder model for unmixing the absorbance spectra of phytoplankton pigments. Scientific reports 2025, 15, 13157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Yang, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Akoudad, Y.; Chen, J. SSAF-Net: A Spatial-Spectral Adaptive Fusion Network for Hyperspectral Unmixing With Endmember Variability. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2025, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Li, X.R.; Chen, S.H. An Endmember-Oriented Transformer Network for Bundle-Based Hyperspectral Unmixing. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2025, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.; Trivedi, Y.; Bhattacharya, B.; Thakkar, P.; Srivastava, P. Hyperspectral endmember extraction using convexity based purity index. Advances in Space Research 2025, 75, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Bi, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, J.F. Endmember extraction and abundance estimation algorithm based on double-compressed sampling. Scientific Reports 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.Q.; Liu, D.S. Estimating fractional vegetation cover from multispectral unmixing modeled with local endmember variability and spatial contextual information. Isprs Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2024, 209, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.Z.; Liu, Y.T.; Xie, F.; Li, P. An Adaptive Surrogate-Assisted Endmember Extraction Framework Based on Intelligent Optimization Algorithms for Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sensing 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, M.E. N-FINDR: an algorithm for fast autonomous spectral end-member determination in hyperspectral data. In Proceedings of the Conference on Imaging Spectrometry V, Denver, Co, Jul 19-21, 1999; pp. 266-275.

- Boardman, J.W.; Kruse, F.A.; Environm Res Inst, M. AUTOMATED SPECTRAL ANALYSIS - A GEOLOGICAL EXAMPLE USING AVIRIS DATA, NORTH GRAPEVINE MOUNTAINS, NEVADA. In Proceedings of the 10th Thematic Conference on Geologic Remote Sensing - Exploration, Environment, and Engineering, San Antonio, Tx, May 09-12, 1994; pp. I407-I418.

- Alshahrani, A.A.; Bchir, O.; Ben Ismail, M.M. Autoencoder-Based Hyperspectral Unmixing with Simultaneous Number-of-Endmembers Estimation. 2025, 25, 2592.

- Ozkan, S.; Kaya, B.; Akar, G.B. EndNet: Sparse AutoEncoder Network for Endmember Extraction and Hyperspectral Unmixing. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2019, 57, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsoi, R.A.; Imbiriba, T.; Bermudez, J.C.M.J.I.T.o.C.I. Deep generative endmember modeling: An application to unsupervised spectral unmixing. 2019, 6, 374-384.

- Filippi, A.M.; Archibald, R.; Bhaduri, B.L.; Bright, E.A.J.O.E. Hyperspectral agricultural mapping using support vector machine-based endmember extraction (SVM-BEE). 2009, 17, 23823-23842.

- Alfaro-Mejía, E.; Manian, V.; Ortiz, J.D.; Tokars, R.P.J.F.i.E.S. A blind convolutional deep autoencoder for spectral unmixing of hyperspectral images over waterbodies. 2023, 11, 1229704.

- Bioucas-Dias, J.M.; Plaza, A.; Dobigeon, N.; Parente, M.; Du, Q.; Gader, P.; Chanussot, J.J.I.j.o.s.t.i.a.e.o.; sensing, r. Hyperspectral unmixing overview: Geometrical, statistical, and sparse regression-based approaches. 2012, 5, 354-379.

- Feng, X.-R.; Li, H.-C.; Wang, R.; Du, Q.; Jia, X.; Plaza, A.J.I.J.o.S.T.i.A.E.O.; Sensing, R. Hyperspectral unmixing based on nonnegative matrix factorization: A comprehensive review. 2022, 15, 4414-4436.

- Parente, M.; Iordache, M.-D. Sparse unmixing of hyperspectral data: The legacy of SUnSAL. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS, 2021; pp. 21-24.

- Jiang, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Sheng, W. Adaptive collaborative fusion for multi-view semi-supervised classification. Information Fusion 2023, 96, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, D.C.; Chang, C.I. Fully constrained least squares linear spectral mixture analysis method for material quantification in hyperspectral imagery. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2001, 39, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, J.M.; Dias, J.M.J.I.t.o.G.; Sensing, R. Vertex component analysis: A fast algorithm to unmix hyperspectral data. 2005, 43, 898-910.

- Halimi, A.; Altmann, Y.; Dobigeon, N.; Tourneret, J.Y. Nonlinear Unmixing of Hyperspectral Images Using a Generalized Bilinear Model. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2011, 49, 4153–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Q.; Nasrabadi, N.M.; Tran, T.D. Abundance Estimation for Bilinear Mixture Models via Joint Sparse and Low-Rank Representation. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2014, 52, 4404–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Ecological Observatory, N. Site management and event reporting (DP1.10111.001). 2025.

- Palsson, B.; Ulfarsson, M.O.; Sveinsson, J.R. Convolutional Autoencoder for Spectral Spatial Hyperspectral Unmixing. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 59, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.F.; Gao, L.R.; Yao, J.; Yokoya, N.; Chanussot, J.; Heiden, U.; Zhang, B. Endmember-Guided Unmixing Network (EGU-Net): A General Deep Learning Framework for Self-Supervised Hyperspectral Unmixing. Ieee Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2022, 33, 6518–6531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsoi, R.; Imbiriba, T.; Bermudez, J.C.; Richard, C.; Chanussot, J.; Drumetz, L.; Tourneret, J.Y.; Zare, A.; Jutten, C. Spectral Variability in Hyperspectral Data Unmixing. Ieee Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2021, 9, 223–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Q.; Zhang, G.R.; Li, F.; Deng, C.Z.; Wang, S.Q.; Plaza, A.; Li, J. Spectral-Spatial Hyperspectral Unmixing Using Nonnegative Matrix Factorization. Ieee Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Endmembers numbers in pixel | Pixel types | Endmember Coding | Pixels Number | Ratio(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Soil | 0 | 577 | 3.95 |

| Grass | 1 | 4037 | 27.60 | |

| Road | 2 | 14 | 0.10 | |

| Tree | 3 | 46 | 0.31 | |

| 2 | Soil and Grass | 4 | 7392 | 50.54 |

| Soil and Road | 5 | 4 | 0.03 | |

| Soil and Tree | 6 | 10 | 0.07 | |

| Grass and Road | 7 | 25 | 0.17 | |

| Grass and Tree | 8 | 353 | 2.41 | |

| Road and Tree | 9 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| 3 | Grass, Road Tree | 10 | 68 | 0.46 |

| Soil, Road and Tree | 11 | 10 | 0.07 | |

| Soil, Grass and Tree | 12 | 2000 | 13.68 | |

| Soil, Grass and Road | 13 | 89 | 0.61 | |

| 4 | Soil, Grass, Road and Tree | 14 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).