1. Introduction

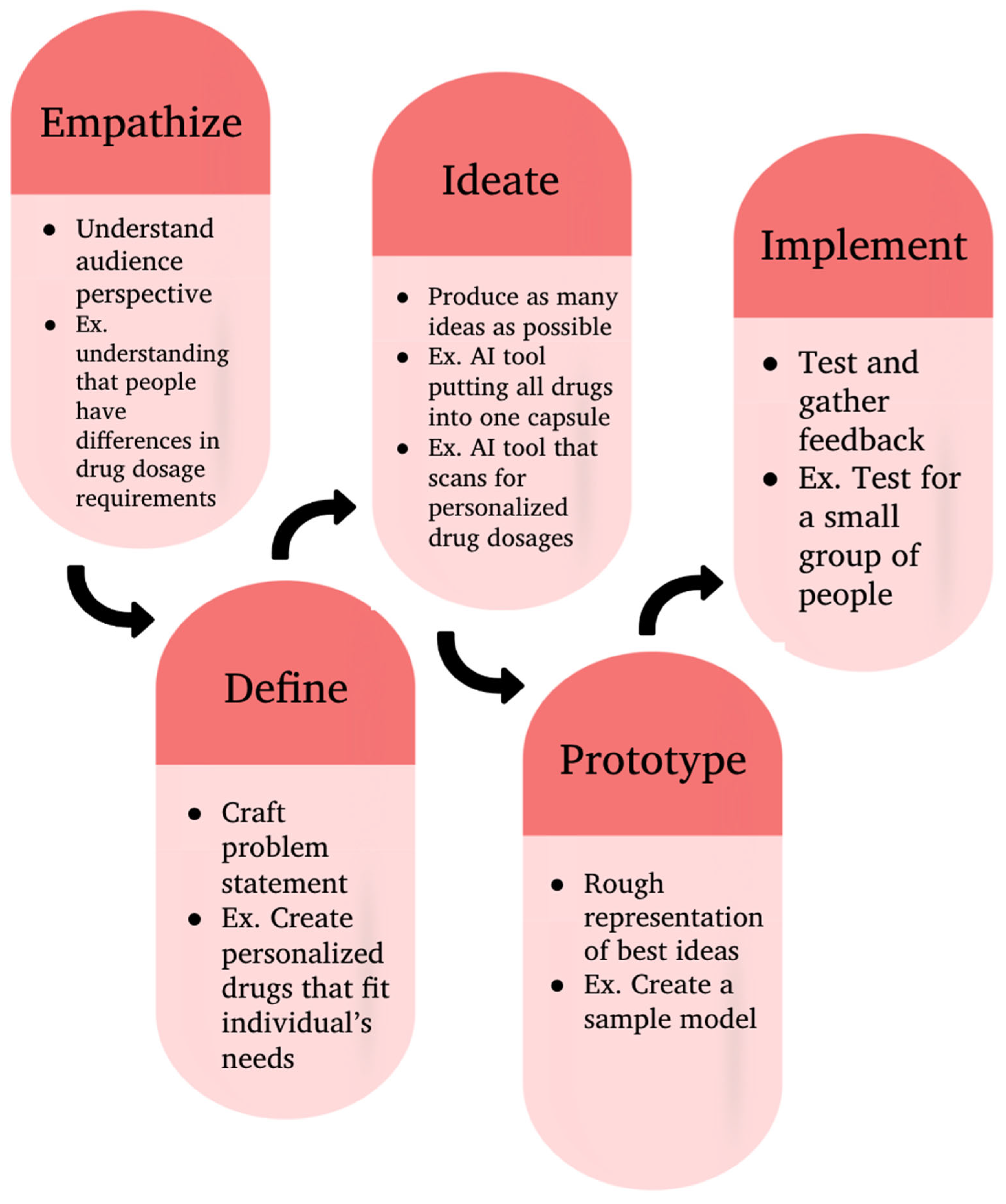

Design Thinking is a human-centered problem-solving approach that emphasizes empathy, creativity, and iterative learning to develop innovative solutions [

1,

2]. Rooted in the 1950s with early contributions from Herbert A. Simon, the methodology gained widespread recognition through Stanford’s D.School, which played a crucial role in formalizing and teaching Design Thinking as a structured process [

3]. The Design Thinking framework consists of five key stages: Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Implement. The process begins with the Empathize phase, where researchers engage with and observe users to understand their needs and challenges. In the Define stage, these insights are synthesized into a clear and actionable problem statement. During the Ideate phase, teams brainstorm a wide range of potential solutions. The Prototype stage involves creating preliminary versions of ideas for early testing. Finally, in the Test phase, feedback is gathered to refine and improve the solution [

4]. These five stages ultimately aim to understand user needs, generate creative ideas, and redefine solutions through rapid prototyping and feedback [

5]. This approach fosters collaboration, reduces risks by validating ideas early, and is effective in creating user-friendly products [

6]. The iterative nature of design thinking enables rapid testing and immediate feedback.

Figure 1.

Design thinking methodology.

Figure 1.

Design thinking methodology.

Design thinking has been applied in healthcare settings to improve patient care, redesign system processes, and streamline drug discovery [

7]. By offering human centered approaches to reframing issues in healthcare organization, design thinking allows researchers to focus on efficiency and patient care [

8]. For example, by using design thinking principles, an emergency department implemented patient advocates to open up communication between the providers and patients. This led to greater patient satisfaction and efficient wait times [

9]. Design thinking in high-stress areas like the ICU has led healthcare innovators to target operational inefficiencies, such as redesigning layouts of medical supplies and equipment for optimized patient care. Another example of design thinking is its application in radiology. By analyzing patient needs, innovators were able to redesign X-ray spaces to create a less intimidating atmosphere. By using design thinking to reframe healthcare issues, innovators are able to focus on patient needs and understand the overall perspective of the issue.

As technology advances, there is more potential for drug discovery to improve. Drug discovery is defined as “a complex and time-consuming process that involves identifying molecules that can interact with specific molecular targets in the body to treat diseases [

10]”. However, drug discovery is not centered around what a specific user needs. Many times drugs are tailored towards those who took part in the study, who, due to historical bias, tend to be white males [

11]. This means many drugs were not tested enough on minorities and women, which leads to 1 in 5 patients experiencing adverse drug reactions (ADR) to drugs that were not tailored enough [

12]. Without diversity in sample sizes, the study may not represent the entire population and can lead to serious side effects, such as ADR. The preferences of users are not addressed in the creation of drugs. In fact, 50% of patients do not take their medications [

13] because the schedules prescribed to them do not work. Many patients face polypharmacy, the use of over medications at the same time [

14]. With patients taking multiple medications, dangers like adverse drug effects, unexpected drug interactions, and prescribing cascades can occur. Drug candidates go through several stages including discovery and development, preclinical research, and clinical trials before a select few make it to FDA review. As of right now, the drug discovery pipeline is a slow and inefficient process, taking on average between 10 and 15 years to develop a drug. Costing

$2.6 billion to reach the marketing approval state with only 14% of drugs gaining FDA approval, the drug discovery process is an ineffective process [

15,

16]. Many drugs fail because of the technology utilized in the drug discovery process [

17]. Some examples of such technologies are organ-on-chips model, QSAR modeling, and De Novo Molecular Design. While these technologies are meant to improve the drug discovery processes, they are often inaccurate or lengthy.

Design thinking has helped shape drug discovery by streamlining the lengthy process, implementing AI for optimization, and focusing on patient satisfaction. By implementing design thinking, healthcare professionals can solve issues using human-centered strategies and focusing on user experience. This ensures that developed medicines and therapies focus on patients' needs, and make the system more efficient. Furthermore, integrating AI into areas such as the identification of novel compounds and lead identification has accelerated the drug discovery process. Models such as QSAR, De novo molecular design, and protein targets can be enhanced using design thinking trained AI. Additionally, AI’s repetitive iterative nature, similar to design thinking, allows models to efficiently identify drug compounds [

18]. This allows the model to run through compounds faster as they have a large database of previous knowledge.

Traditionally, the pharmaceutical industry has relied on small bioavailable molecules around "druggable" targets, guided by Lipinski's Rule of Five (Ro5). It predicts permeation if a molecule exceeds specific parameters when identifying molecular targets. However, the industry calls for exploration beyond traditional small molecules and Ro5. Advances like artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are transforming drug design by addressing challenges in peptide synthesis, structure-based and ligand-based virtual screening, toxicity prediction and pharmacophore modeling, quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) and drug repositioning and poly-pharmacology [

19].

The de novo method, a traditional approach to drug design, faces challenges such as complex synthesis pathways and difficulties in predicting biological effects in compounds. With AI, these challenges can be addressed by enabling efficient compound creation [

20]. AI models have efficient compound generation, cost reduction, and faster lead identification compared to the de novo method. Generative models like Reinforced Adversarial Neural Computer (RANC) and other generative frameworks can generate molecular structures based on specific chemical properties and offer innovative solutions by optimizing molecular diversity while maintaining structural feasibility [

21]. AI-driven frameworks like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks are used to generate libraries of potential drug compounds.

Pharmacovigilance is crucial in detecting and preventing adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and highlights the role of AI in addressing emerging challenges like polypharmacy and patient diversity. The pharmaceutical industry faces many challenges concerning drug safety. The high attrition rate of drugs due to unexpected toxicities, structural limitations in clinical trials, and post-marketing challenges like underreporting of ADRs contribute to these challenges [

22]. Traditional methods of QSAR modeling as a foundational approach in predicting drug toxicity and the use of animal studies and their constraints are outdated when compared to the emergence of advanced AI techniques that are less problematic in fields of cost, ethics, and time [

23]. AI's ability to process vast datasets from electronic health records (EHRs) and other medical databases limits the further potential of human error and increases clinical efficiency [

24]. In post-marketing surveillance, where drugs are monitored for ADRs, AI can address bias in spontaneous reporting systems and improve the detection of rare events and drug-drug interactions.

Compared to traditional methods, AI excels in rapidly generating responses due to its iterative nature and identifying limiting factors in current drug discovery. However, AI falls short in producing the creative responses necessary for innovation in the field of healthcare. This gap presents an opportunity to implement design thinking to further foster creativity in problem-solving and enhance innovation. Through integrating the precision of AI and empathetic problem-solving elements of design thinking, more efficient and cost-effective approaches to healthcare challenges in drug discovery can be developed and hold the potential to revolutionize the innovation process of the pharmaceutical industry. Considering the above information, in this research article we aimed to integrate Design Thinking in Drug Discovery. Furthermore, by generating broader solutions without original innovation, AI generates solutions that are detached from the user. This allows for iterative, empathetic, and varying solutions. In our study, we aim to address the gap through the implementation of design thinking using a Large Language Model (LLM), through which the models can reframe their perspective to be more patient-centered while prioritizing efficiency and empathy. Our research opens a new era of applying generative AI to address the Drug Discovery pipeline.

2. Background

Design thinking differs from traditional problem-solving by emphasizing empathy, iteration, and efficiency over linear, data-driven analysis [

25]. Unlike conventional methods that follow a structured, rigid process to identify a single solution, Design Thinking focuses on deeply understanding user needs through research, observation, and empathy, allowing for more creative and unconventional solutions. A key distinction is the use of rapid prototyping, a concept that addresses the critical gap in innovation that only about 10% of new products or services effectively meet user needs, while the remaining 90% result in wasted resources. By integrating rapid prototyping, Design Thinking allows teams to test multiple ideas early, minimizing risk and allowing for continuous ideation. This reduces the risk of failure by ensuring that solutions are continuously improved before large-scale implementation. By focusing on user needs, experimentation, and adaptability, Design Thinking is particularly effective for solving complex, innovation-driven challenges across fields [

26].

Generative artificial intelligence is a subset of deep learning models that can be trained using large amounts of data to perform certain tasks [

27]. Large Language Models (LLMs) are a type of generative artificial intelligence with the ability to respond to text [

28]. LLM is trained on large quantities of data through the processes of self-supervised, supervised, and reinforced learning [

29,

30]. These models can perform a variety of tasks including summarizing and answering questions.

Our study focuses on three main LLM models. A prominent one is ChatGPT, a chatbot trained to interact with humans and produce text using a large dataset [

31]. It was designed by OpenAI to generate human-like text responses, assist with writing, answer questions, and perform various tasks. Another AI model is Google DeepMind's Gemini, formerly known as Bard, which is designed to handle complex reasoning, multimodal inputs (text, images, and audio), and real-time information retrieval. Gemini integrates with Google’s ecosystem, enhancing applications like Search, Docs, and Assistant. Another emerging AI model, DeepSeek, developed by a Chinese AI research team, focuses on natural language understanding, coding, and multilingual capabilities, with an emphasis on high-performance AI for enterprise and research applications.

As a user-centered problem-solving approach, Design Thinking has applications in a variety of fields, from education to farming and much more.

Invented by David Kelley, a professor at Stanford University, the Design Thinking method is a way to come up with ideas [

32]. He states that to work with complex projects, the prototyping and implementing of inventions is a fundamental step. Through recent collaboration, the Hasso Institute of Design and the Stanford Institute for Human Centered Design have been working on combining the design thinking approach with the use of artificial intelligence. The projects aim to improve research on AI systems that are human-centered. They have projects on AI-assisted privacy, human-human interaction, fabrication tools, and social computing systems [

33].

Design Thinking implementation in media management education has been examined through a structured university course designed to train students, especially those with technical backgrounds, in user-centered innovation. Conducted by the EMMi Lab at Tampere University of Technology in Finland, the course blended the traditional Design Thinking phases with additional self-learning and business planning stages. It emphasized active, problem-based learning, requiring students to participate in interdisciplinary teamwork, understand consumer needs, and iteratively refine their solutions. The course was structured as a hands-on experience in an innovation lab setting, ensuring a creative, open environment that encouraged exploration. A major focus was to overcome common educational limitations by teaching students how to navigate “wicked problems”—problems that are complex and ill-defined—in media innovation, encouraging integrative thinking, experimentation, and collaboration. Students engaged in real-world challenges, developing practical prototypes and business plans, therefore bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. Ultimately, the course demonstrated how Design Thinking can be effectively adapted and applied to business management education, equipping students with the skills necessary to approach complex problems creatively and strategically [

34].

Design Thinking further has applications in improving healthcare delivery intensive care units (ICUs), specifically in aligning life-sustaining treatment with patient values. In a study by Kristyn A Krolikowski et al., Design Thinking principles were applied to develop more patient-centered approaches in critical care [

35]. While Design Thinking provided practical tools for engaging multiple perspectives, it also posed challenges, such as the risk of overgeneralization and the absence of standardized evaluation criteria. To address these limitations, qualitative research methods were used to create structured evaluation techniques. The study highlights the potential of Design Thinking in healthcare while emphasizing the need to complement it with established evaluation methodologies. Ultimately, Design Thinking can enhance healthcare delivery in the ICU by fostering meaningful collaboration between clinicians, patients, and families [

36].

This paper aims to further apply Design Thinking to the context of drug discovery by using the problem-solving process to address the following issues within the drug discovery process:

Induced pluripotent stem cells or iPSCs are differentiated into various cell types that model human diseases in vitro, providing a valuable alternative to traditional animal models in drug discovery. Somatic cells of patients can be reprogrammed to their pluripotent state form to be able to derive the disease genotype [

37]. In vitro cell-based models of neural lineage cells of diseases hold promise for monitoring disease progression and can improve drug testing on patient-derived cells, limiting unexpected side effects [

38]. The implementation of iPSCs holds a new strategy to model human cancer as they have characteristics similar to embryonic stem cells and can provide a valuable tool in understanding the pathogenesis of familial cancer early on to identify additional genetic alterations [

39]. However, the potential of iPSCs is unstable and limits their effectiveness for clinical and research applications. They have unpredictable changes in their DNA and gene regulation during or after reprogramming [

40]. These changes could lead to harmful effects like cancer or reduced functionality.

These computational methods of drug discovery have also improved in recent years, such as machine learning, molecular docking, and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling. The use of artificial intelligence in drug discovery enhances molecular design, drug repurposing, and toxicity prediction. These methods can model how a drug might interact with the target, but they often struggle with issues like overfitting and predicting accidental interactions with other proteins. They also have issues of high costs, time consumption, and low efficacy, and require much improvement before they can be used regularly for drug design [

41].

Animal testing, procedures performed on animals [

42], is one approach used to test drugs. However, animal testing has very high failure rates, with 9 out of 10 such as high failure rates, inaccurate representations of humans, and ethical concerns. One technology used in drug discovery is the organ-on-chips model, cultures of engineered miniature human tissue systems developing in microfluidic chips [

43]. The organ-on-chips system was formed to create an accurate model to test drugs on instead of using animals to test treatments. However, this model has a lot of room for improvement. The main issue with human organs-on-chips for disease modeling and drug development is the difficulty in fully replicating the complexity of human physiology, including inter-organ interactions, immune responses, and disease-specific factors, while also ensuring scalability, reproducibility, and regulatory acceptance.

De novo molecular design involves generating novel chemical structures that meet specific objectives, such as biological effectiveness, safety, and synthesis feasibility [

44]. A key challenge is balancing these factors, as highly effective molecules may be difficult to synthesize or pose safety risks, while simpler molecules may lack potency [

45]. While generative models and computational methods can explore chemical space more efficiently than traditional approaches, they still struggle to predict the real-world feasibility of molecules [

46]. As a result, de novo design often fails to generate compounds that optimize the trade-offs between these competing needs, limiting its effectiveness in drug discovery. The iterative nature of design thinking can improve de novo molecular design, allowing it to rapidly test different compounds.

QSAR (Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship) correlates the biological activity of compounds to chemical structures [

47]. It has a crucial role in drug discovery as it lets researchers evaluate drugs without a long and expensive process [

48]. QSAR looks at separate molecular features and correlates them with the actual biological effect, which allows researchers to predict the effects of a certain drug or compound. It has been used for years throughout the drug discovery pipeline and rapidly streamlined the screening of chemical libraries. AI can also be implemented in QSAR, improving its accuracy and solidifying its critical role in modern drug discovery [

49]. A design thinking trained Large Language Model can also be implemented in QSAR, improving its accuracy and solidifying its critical role in modern drug discovery.

Protein targets are considered druggable if they can bind to small drug-like molecules and produce a desired therapeutic effect. A protein is considered undruggable if it is difficult to target for drug development. Some contributing factors which may make a protein target undruggable are if it has flat functional interfaces without defined pockets for ligand interactions, is involved in several other protein-protein interactions, or is an intracellular protein rather than an extracellular protein. As of today, about 85% of proteins are considered undruggable, translating to about 60% of drug discovery projects failing due to undruggable targets. Implementing protein targets to increase the accuracy of drug development and streamline the pipeline can save time and money. Furthermore, machine learning can enhance the accuracy of druggable proteins.

Considering all the above applications of DT in medicine and healthcare, our study tries to understand how each LLM (ChatGPT, Gemini, & Deepseek) will further help to address these drug discovery challenges in a systematic approach like multiple iterations and testing to discover an optimized drug.

3. Methodology

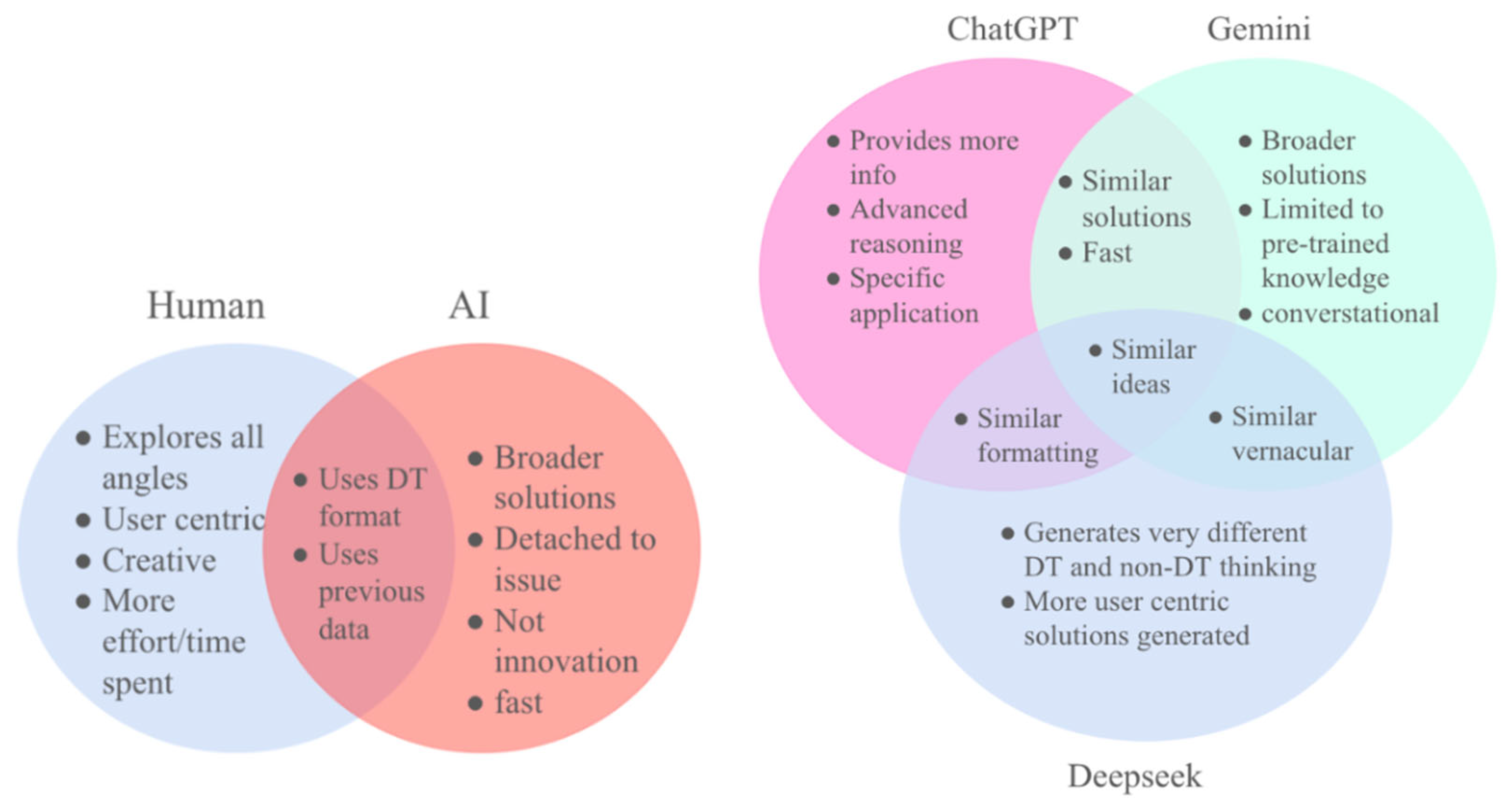

This study examines AI-driven design thinking in healthcare, particularly in the drug discovery pipeline. AI is being increasingly implemented in problem-solving, making it crucial to examine how AI models, such as Chat-GPT, Deepseek, and Gemini compare to human creativity when addressing healthcare challenges. By implementing design thinking principles of repeated iterations and user-centric solutions, this research compares the different design thinking trained AI models, and human ingenuity to discover the strengths and limitations of each approach.

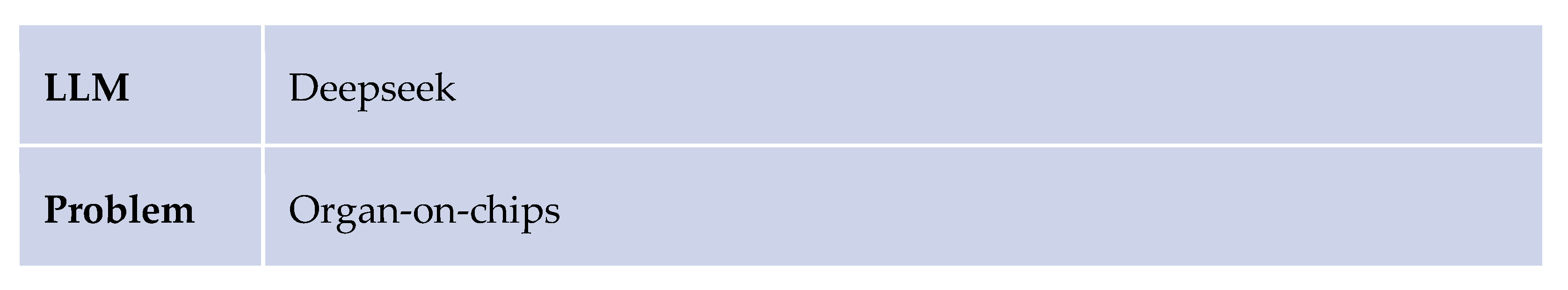

Figure 2.

A comparison of Human vs. AI and ChatGPT vs. Gemini in addressing problems using design thinking.

Figure 2.

A comparison of Human vs. AI and ChatGPT vs. Gemini in addressing problems using design thinking.

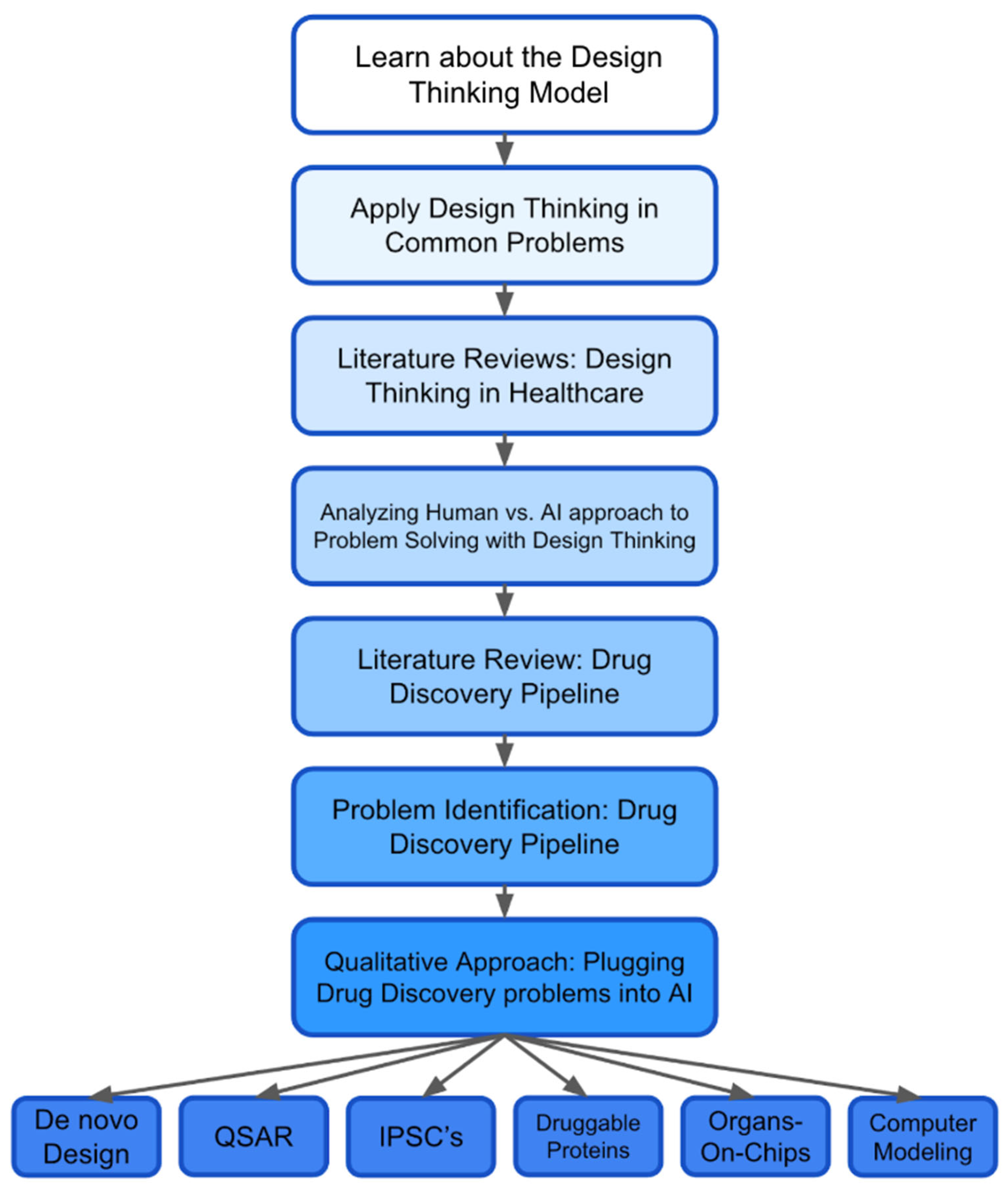

Thorough literature reviews were conducted on numerous topics, including design thinking in healthcare, AI-driven problem-solving in drug discovery and medicine, and pharmaceutical problems relating to drug discovery. Reviews were utilized to identify major challenges in the pharmaceutical industry and recognize the potential of the Stanford design thinking process in drug discovery as a more patient-centered framework. Six main problems were identified surrounding the risks of implementing iPSCs, challenges with computer modeling molecules, organs-on-chips, druggable proteins, de Novo molecular design, and QSAR.

A qualitative comparison was done to select a large Language model (AI generative models) that would be used to conduct the study. The research was conducted using the ChatGPT, Gemini, and Deepseek models to create applicable solutions for major problems found in the pharmaceutical industry. To be able to accurately distinguish the benefit of applying design thinking in the drug discovery and design process, a second set of trials were conducted asking both models to create solutions to the same set of problems with the Stanford design thinking process. A description of the process was provided to assist the accuracy of the model's response. The prompt required the model’s response to follow each core stage of the process including empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test.

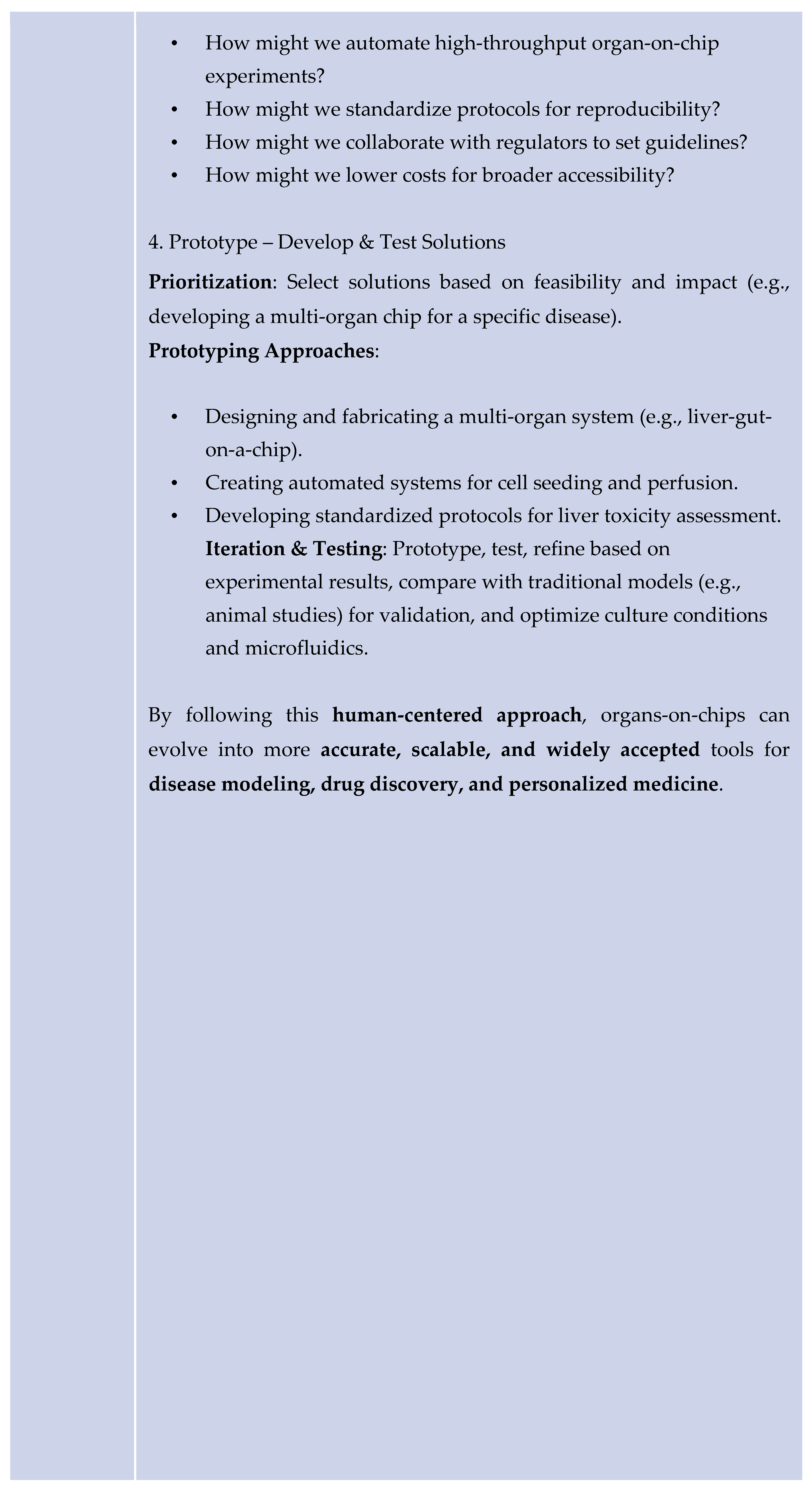

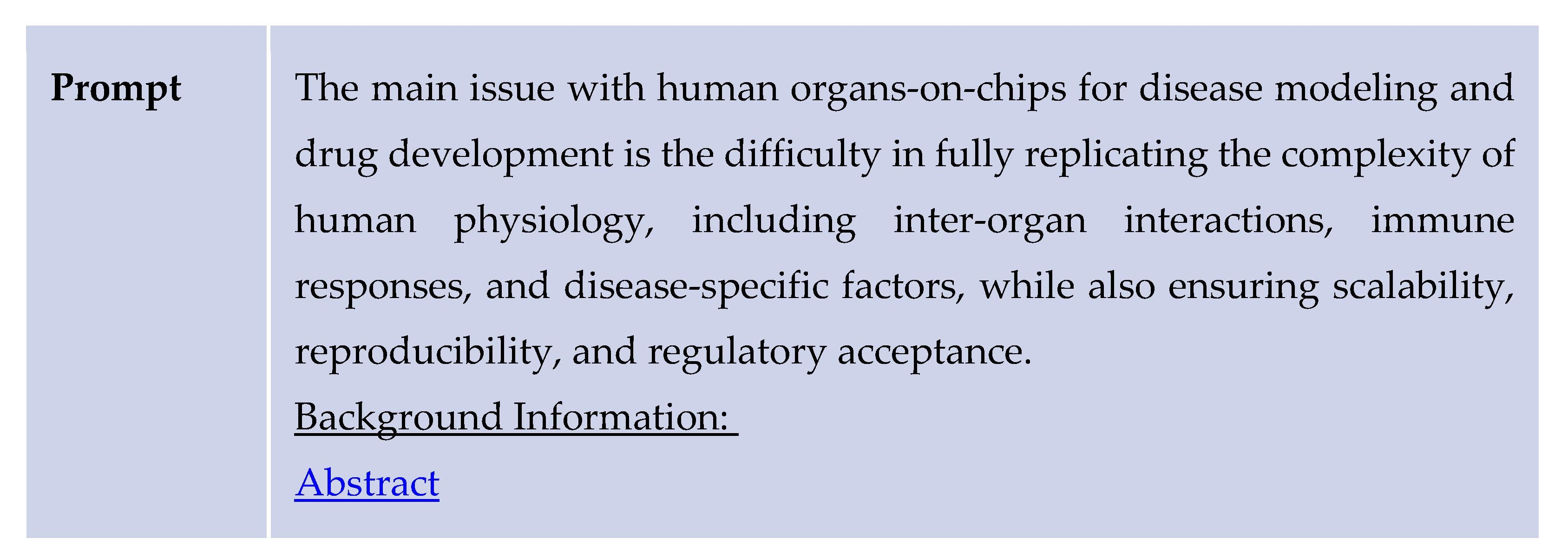

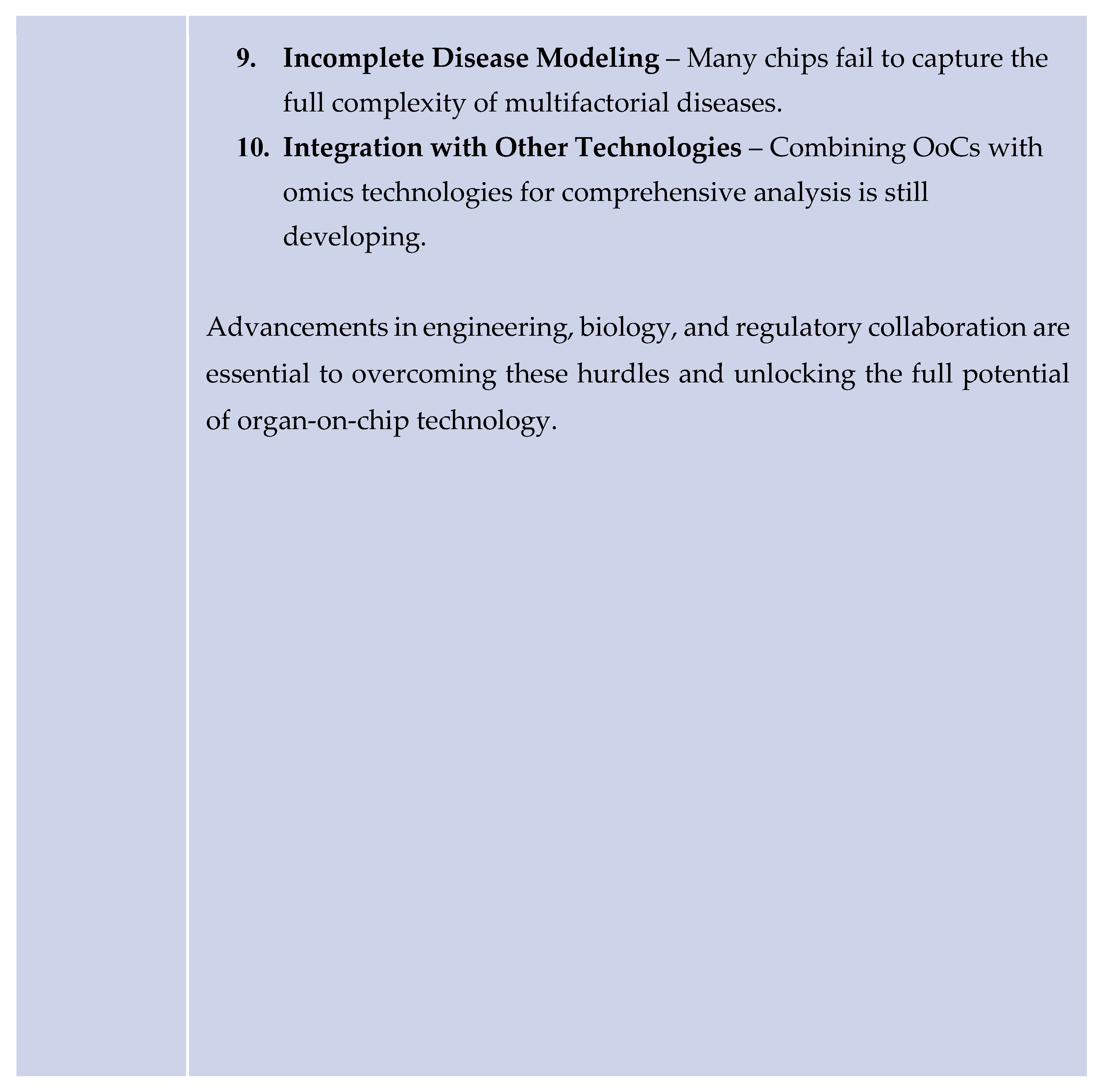

Figure 3.

Methodology pipeline.

Figure 3.

Methodology pipeline.

This pipeline refers to the methodology of the study and outlines the integration of design thinking into drug discovery. It begins with the applications of design thinking to common problems and also details on the qualitative approach taken to assess the incorporation of AI in our novel design.

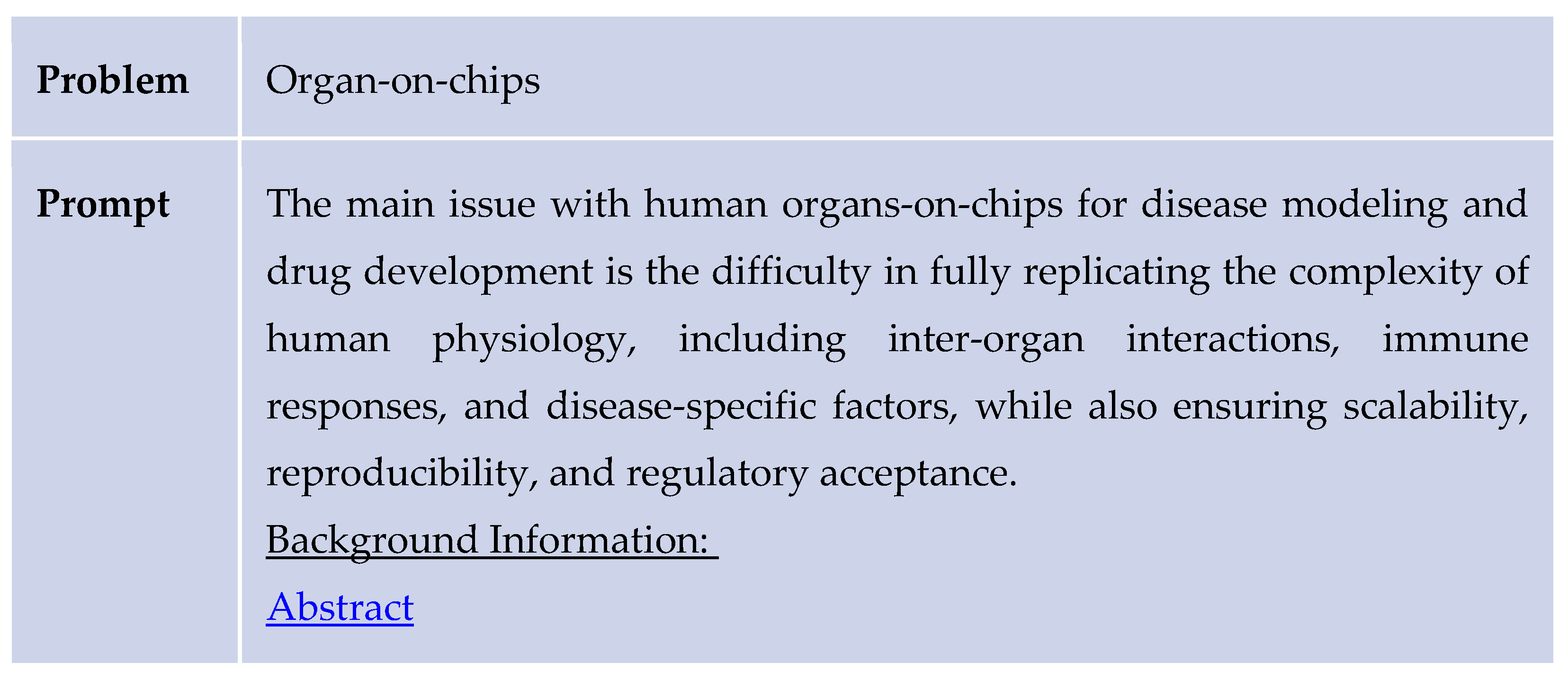

The study was conducted through a structured process that involved selecting a review article, defining a problem statement, and obtaining AI-generated responses both with and without the application of the design thinking methodology. Initially, the AI was provided with a reference abstract and prompted to identify a relevant problem related to the study’s focus. For example, it was asked: “What are some problems concerning organs-on-chips for drug development and personalized medicine? Here is an abstract for reference: [abstract].” The AI responded by identifying the primary challenge as the difficulty in fully replicating the complexity of human physiology—specifically inter-organ interactions, immune responses, and disease-specific factors—while also ensuring scalability, reproducibility, and regulatory acceptance.

Subsequently, the AI was asked to propose solutions to the identified problem while referencing the same abstract. To enhance its domain-specific knowledge, it was provided with a reference paper covering key topics such as 1)organ-on-chip models, induced 2) pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), computational modeling, 3) druggable proteins, 4) de novo molecular design, and 5) quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) analysis. A sample prompt included: “Use the following information to generate solutions for this problem concerning human organs-on-chips modeling: Question: [problem statement]. Information: [abstract].”

Following this, the same problem-solving process was repeated using the design thinking methodology. The AI was prompted to apply this framework by structuring its response through stages such as empathizing with users, defining the problem, ideating potential solutions, prototyping, and testing. An example prompt was: “Use the following information to generate solutions to this problem regarding human organs-on-chips modeling using the design thinking problem-solving methodology: Question: [problem statement]. Information: [abstract].”

The responses obtained through both approaches were systematically compared and analyzed to identify similarities and differences. This analysis aimed to assess the impact of explicitly training an AI model to use design thinking versus allowing it to solve the problem without a structured methodology.

Finally, both results were compared to find the similarities and differences when training an LLM to use design thinking as opposed to simply asking it to solve the problem. In the final phase, the characteristics of each model were analyzed and compared. By evaluating factors such as creativity, effective use of design thinking, and adaptability, a chart was created to compare the three models. These similarities and differences were transferred to a Venn diagram. This diagram plotted the strengths and weaknesses of each model which allows for classification of areas where AI does well and areas where human ideas may still be needed.

4. Results

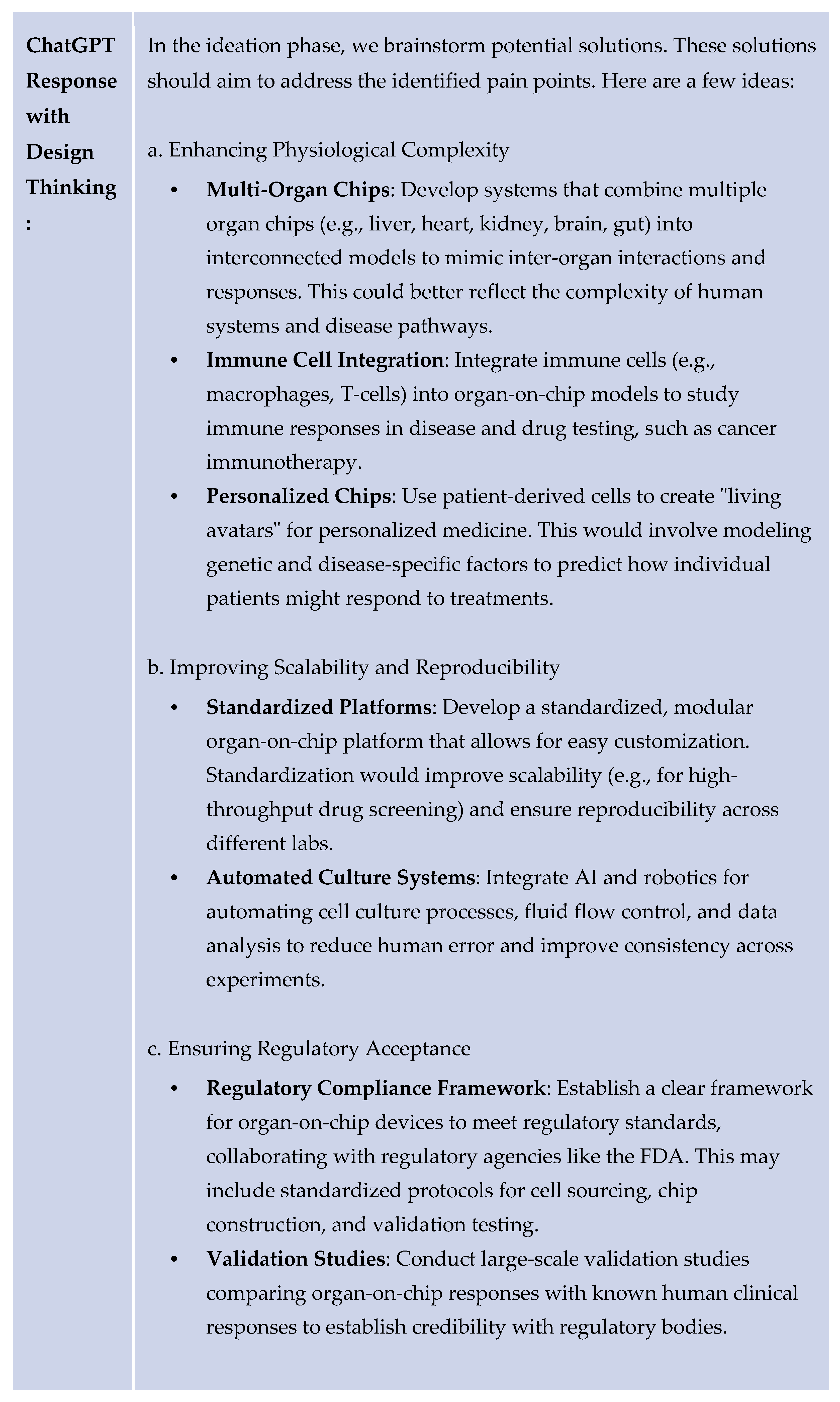

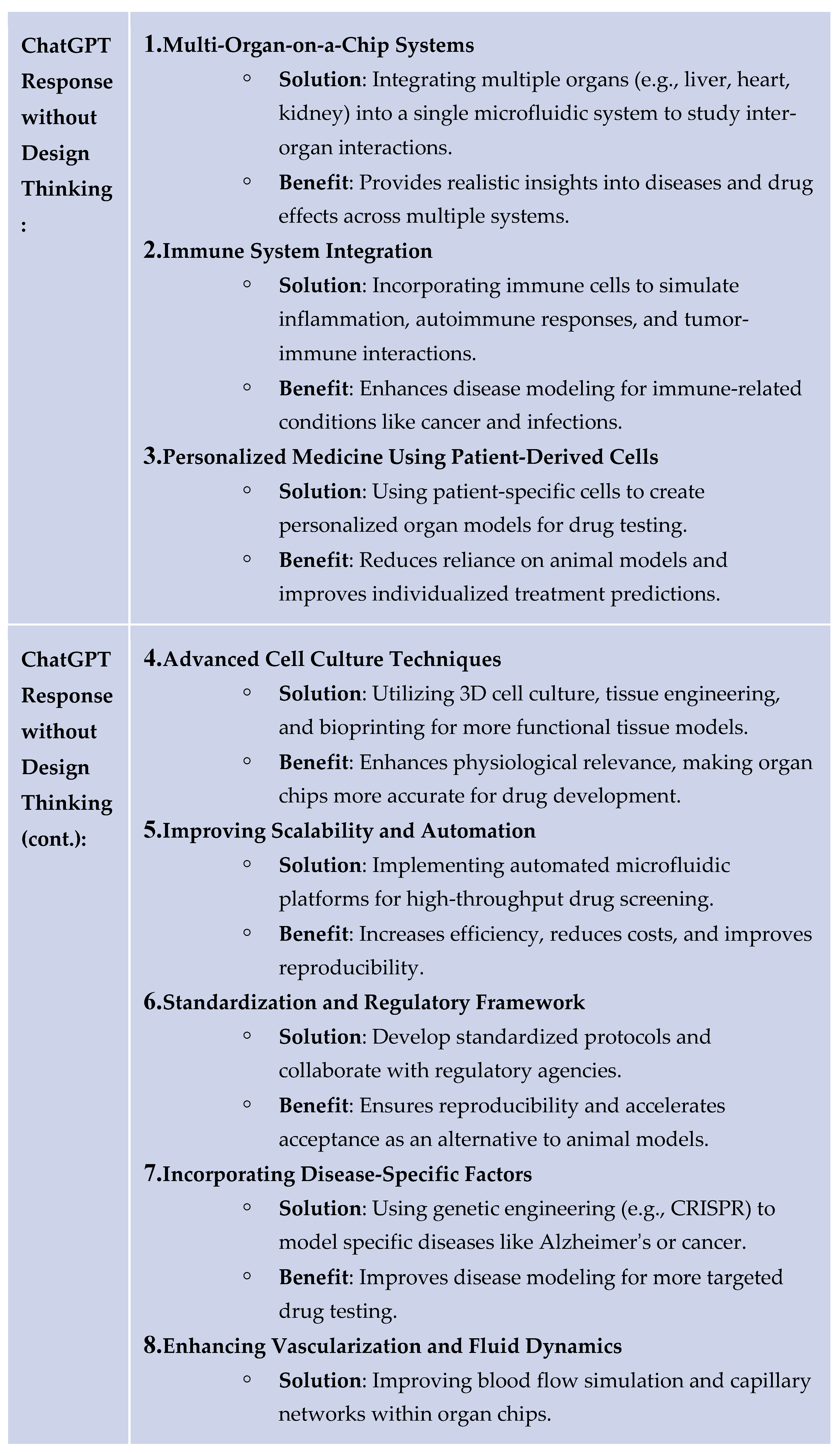

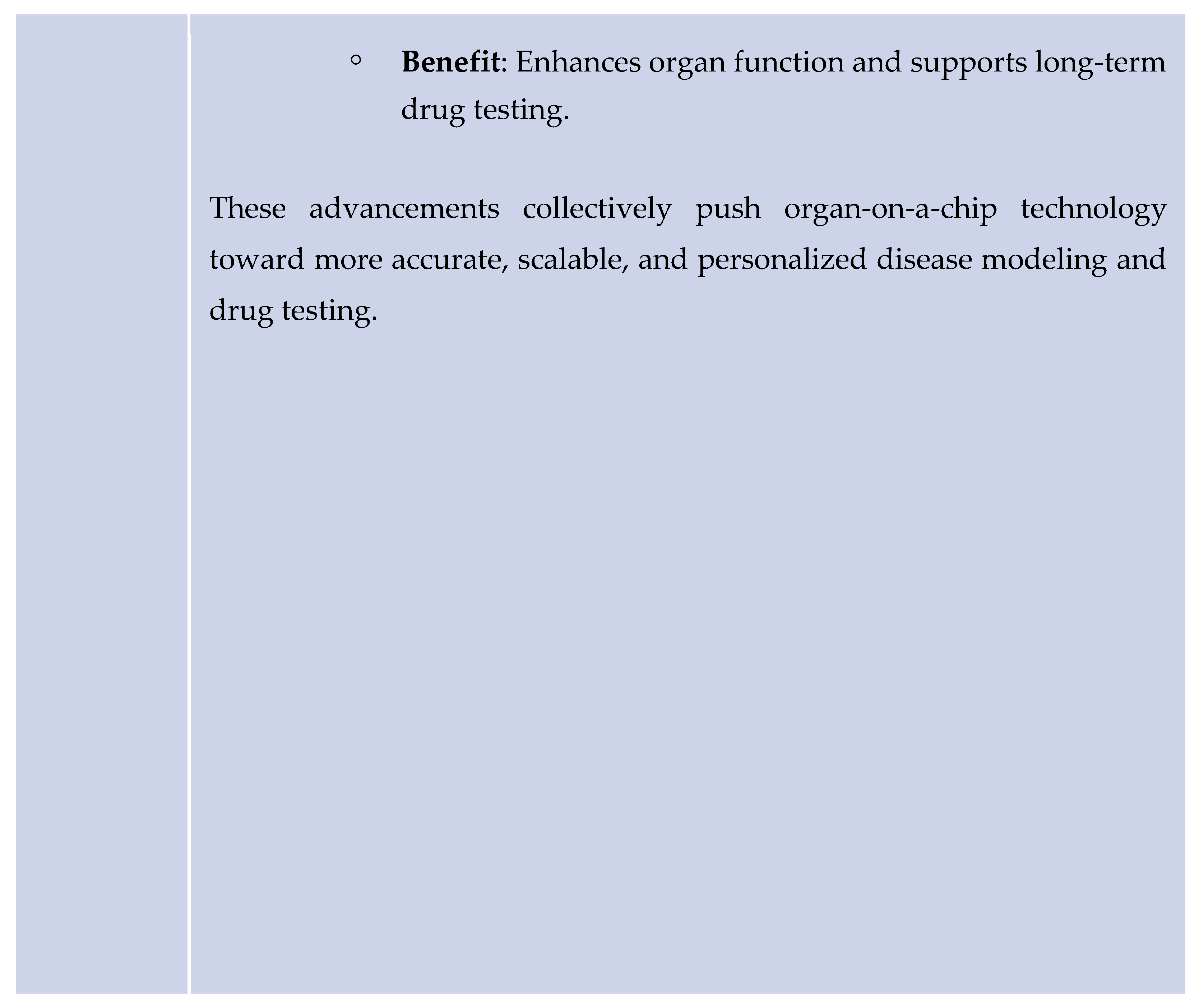

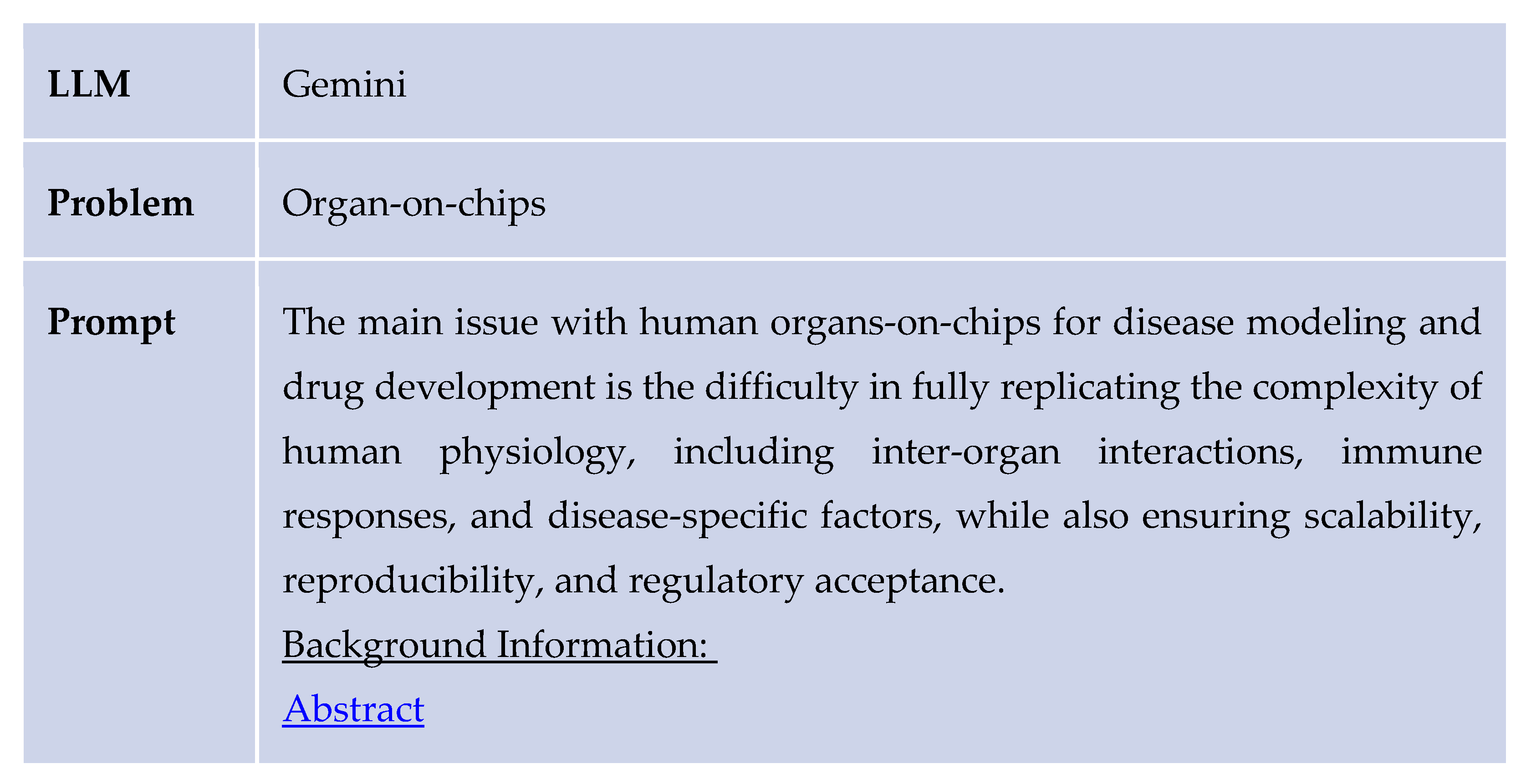

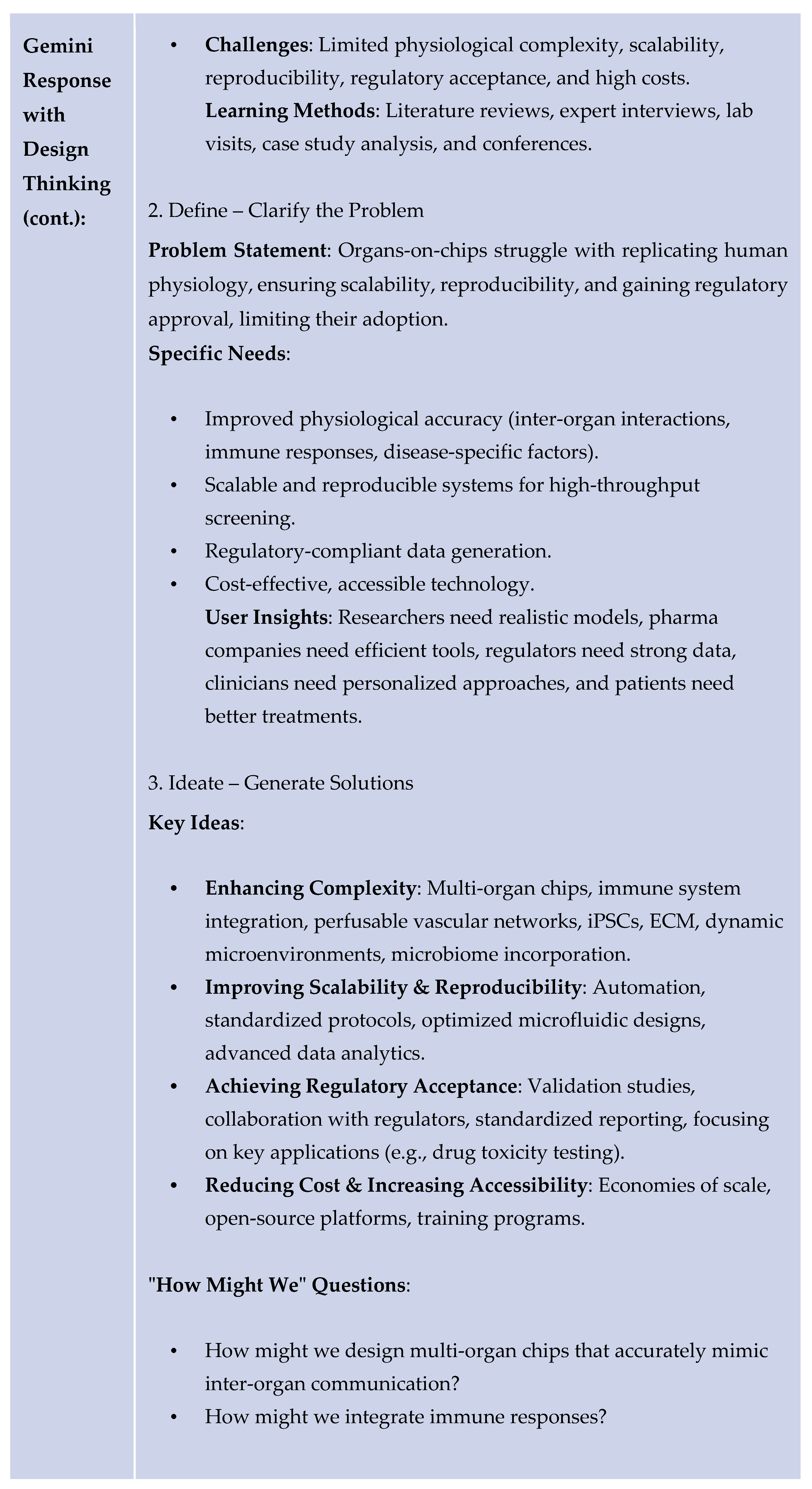

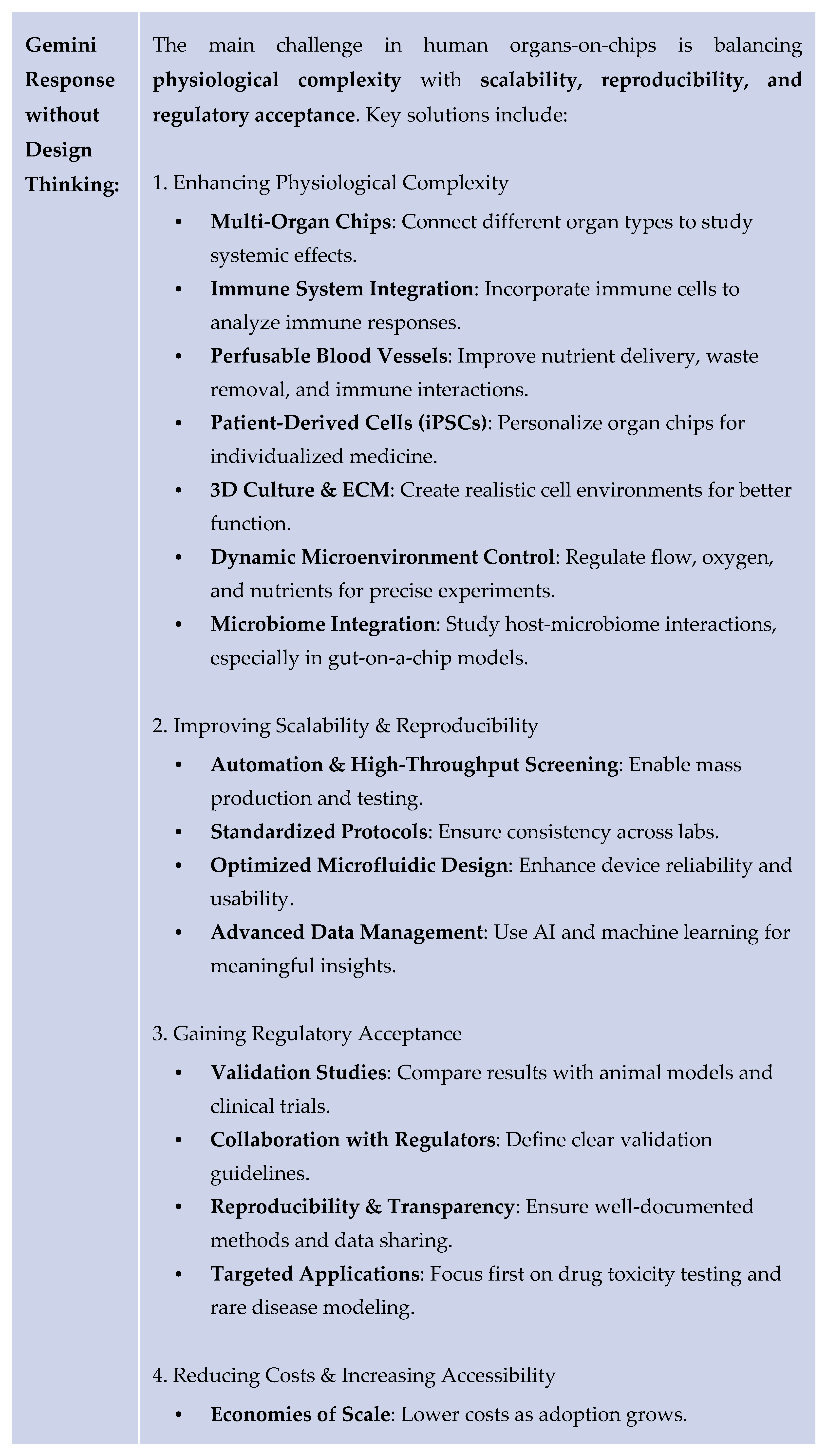

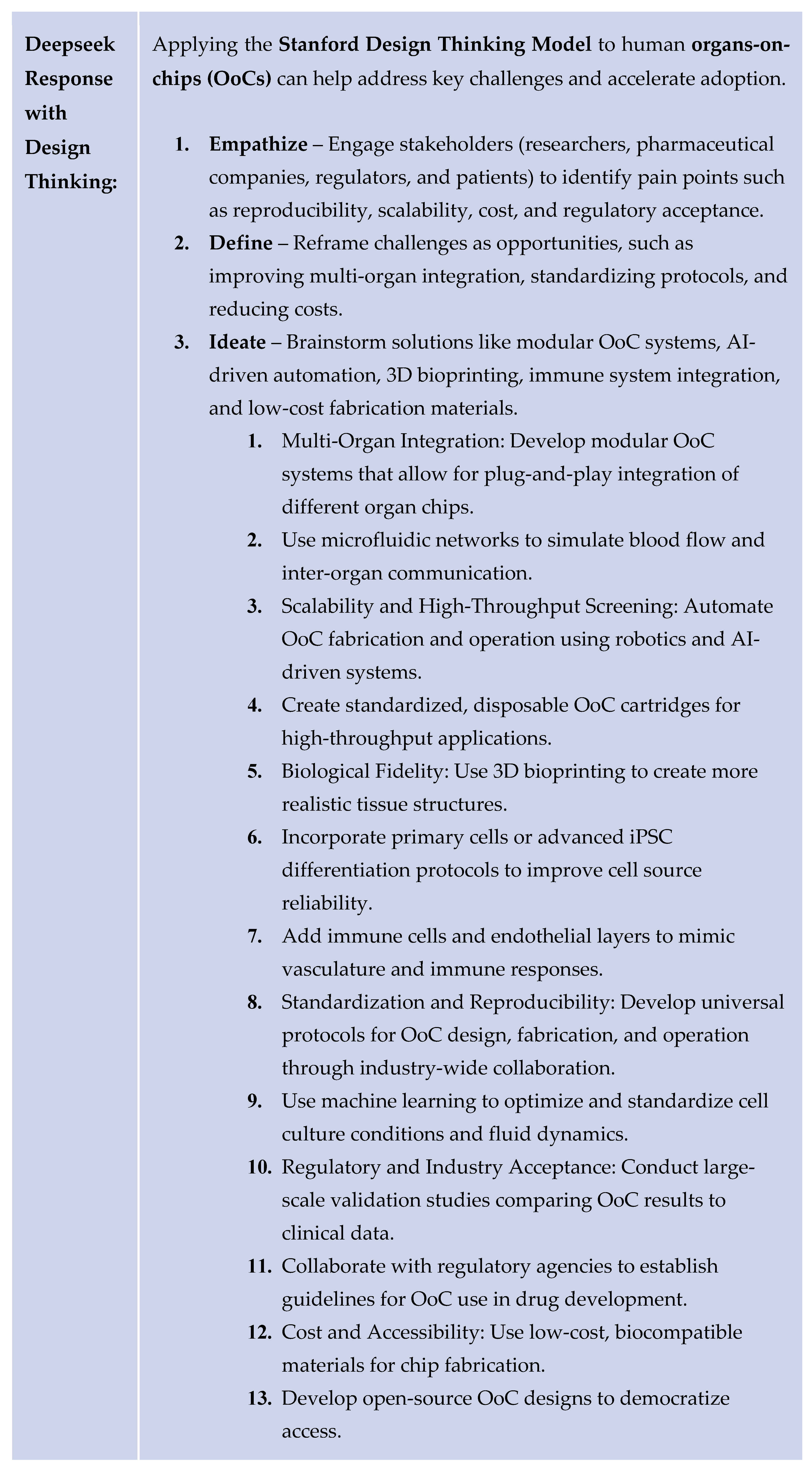

To assess AI’s ability to implement Design Thinking in the various aforementioned problems, we prompted each LLM with problem statements paired with a review article abstract about the specific topic to contextualize. Summarized example LLM responses with and without the Design Thinking methodology regarding the human organs-on-chips for disease modeling and drug development are provided below. A secondary document containing the full list of problems, prompts, and responses can be accessed for further demonstration.

As shown above, the Design Thinking response from ChatGPT provided a clear implementation plan and realistic solutions. Similar results were found for several other problems in the healthcare and drug discovery sector. The following table provides an example response generated by Gemini for the same problem regarding the organ-on-chips.

The following table provides an example response generated by Deepseek for the same problem regarding the organ-on-chips.

Some of the other main issues in drug discovery that the AI models aimed to solve are iPSCs, Druggable Proteins, De novo molecular design, and QSAR.

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) face major limitations due to genetic and epigenetic instability introduced during the reprogramming process, potentially leading to tumor formation or inconsistent results. When analyzed through a Design Thinking (DT) framework, all LLMs emphasized a more human-centered, iterative, and interdisciplinary approach. The ChatGPT-generated response offered a higher-level conceptual understanding of Design Thinking and traditional methods, emphasizing empathy, iterative refinement, and long-term scalability. It was more abstract and lighter on technical detail. Gemini's response, on the other hand, was more technically dense and specific, offering a wide array of concrete solutions across both DT and non-DT frameworks, including parthenogenesis, microRNA modulation, and machine learning. Gemini's DT response did not have clear applications of the Design Thinking framework. DeepSeek emphasized user needs and suggested genome editing tools such as CRISPR-Cas9 and AI-drive quality control in its DT section. Its non-DT section focused on technical solutions like epigenetic modulators. Gemini provided richer technical content and broader solution spaces, which would benefit a reader with a scientific background. Deep Seek provided a cohesive overview of scientific and human-centered strategies. However, ChatGPT better captured the process of Design Thinking, making it more suitable for implementation in drug development.

The main challenge with druggable proteins is that only a small amount of proteins have specific protein pockets that can bind to small drug-like molecules, which render them druggable. This means that around 85% of proteins in the human body are undruggable, making the drug discovery lengthy and risky, with a reduced potential for clinical applications. Future advances in protein technology are necessary to increase the number of proteins that can be targeted by drugs. The LLMs focusing on analysis through a Design Thinking framework brought forth creative solutions such as using special peptides, PROTACs, and AI in order to identify new binding spots and to design more effective molecules. The non-design thinking model was more analytical, direct, and technology-driven, and presented solutions without a structured iterative process. The LLMs using Design Thinking overall had more user centered and feasible ideas generated than the LLMs with non Design Thinking analysis.

The process of de novo molecular design involves creating new molecules; however, the method struggles with creating molecules that balance the needs of effectiveness, safety, and ease of synthesis. If the models created by this method don't have the expected impact, it can be dangerous in clinical applications and difficult to manufacture and distribute. These challenges limit the usefulness of de novo molecular design in drug discovery. The design thinking AI models broke the problem into challenges faced by each stakeholder. It prioritized collaboration, transparency, and interactive AI tools. The non-design thinking AI was technical and structured solutions around scientific and algorithmic improvements.

Organ on chip models entail creating cell cultures on plates. These models commonly face issues regarding ethics and high failure rates. Large language models such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Deepseek when asked to solve the organs on chips problem rarely take the user and their needs into consideration. When the three AI models mentioned above were trained to use the Design Thinking approach to solve the same problem, they provided more detailed solutions. These solutions were more creative and also had more empathy for the user. Some solutions the models gave when using design thinking were on reducing cost and increasing accessibility, with critical questions that validated the user’s interests. These solutions compared much better than solutions without the use of Design Thinking.

Computational models often face challenges such as overfitting, poor generability, high costs, and time consuming processes. AI models that are not trained on design thinking address these issues by using specific technical solutions such as expanding databases and integrating data. However, these solutions do not consider stakeholders in the healthcare system, such as patients, providers, and researchers. When trained on design thinking, the AI models gave more comprehensive solutions by being more user oriented and identifying root causes such as not enough patient data, broken validation systems, and lack of collaboration. The design thinking trained models proposed solutions like using pharmacogenomics data and validating the model’s predictions with real world data.

QSAR modeling faces challenges with overfitting. Since the model performs well on training data, it becomes accustomed to the training data and struggles with generalizing to new compounds. The QSAR model learns irrelevant patterns in the training data such as noise, which reduces its predictive accuracy for new datasets, which limits its application in drug discovery. The AI models trained to use design thinking identified the different needs of drug developers, patients, and researchers in off-target drug effects and came up with a range of solutions. Some examples include using AI in lab testing and implementing simulations. ChatGPT provided extensive solutions presented in the design thinking format, while Gemini’s answer when using design thinking was significantly shorter. The non-design thinking model for all the LLMs gave a longer list of quick and technical solutions.

The comparisons made in ChatGPT, Gemini, and Deepseek, which compare design thinking and non-design thinking approaches, explore the ways in which AI can use design thinking methodology to improve the drug discovery industry. ChatGPT’s responses with and without design thinking highlight the importance of using a design thinking model. The design thinking approach demonstrates well-thought-out solutions and a clear path to follow. The solutions provided empathize well with the people, encouraging the drug discovery industry to be more customer-centered.

Additionally, Gemini provides detailed responses using design thinking methodology, providing specific needs, follow-up questions, and detailed explanations. The combination of Gemini and the design thinking method can help to clear the process going into drug discovery.

When DeepSeek used the design thinking method, it provided a long list of ideas during the prototype stage. The vast quantity of solutions provided can help speed up the drug discovery process through the process of rapid iteration. The combination of Deepseek and the design thinking process creates the potential to improve the healthcare industry.

These findings create the foundation for the healthcare implications, which will be explored in the discussion section.

5. Discussion

AI and human cognition each offer distinct advantages in problem-solving. AI excels in processing vast amounts of data, recognizing patterns, and optimizing predictive models with unparalleled speed and efficiency. However, it lacks contextual understanding, ethical considerations, and the ability to incorporate patient-centered needs. Human researchers, on the other hand, contribute experiential knowledge, creativity, and ethical reasoning, which are essential for developing innovative and practical solutions.

The integration of Design Thinking with AI combines AI's analytical capabilities with a structured, iterative approach that prioritizes user needs and interdisciplinary collaboration. Traditional problem-solving in pharmaceutical research often follows a rigid, linear model, potentially overlooking critical patient-centric factors. Design Thinking introduces flexibility through continuous feedback, rapid prototyping, and iterative refinement, ensuring that technological advancements are both scientifically robust and practically relevant. By leveraging AI within a Design Thinking framework, pharmaceutical research can achieve both efficiency and adaptability, leading to more effective and patient-focused outcomes.

Design Thinking offers substantial benefits across various aspects of pharmaceutical research and development. By incorporating stakeholder engagement from the early stage spanning researchers, clinicians, and regulatory agencies, Design Thinking facilitates the development of more biologically relevant models, improving drug testing reliability and reducing dependence on animal models. Another significant application is in personalized medicine. Conventional clinical trials often fail to adequately represent diverse populations, leading to variations in drug efficacy and safety. Design Thinking ensures that patient demographics and genetic variability are integral to the development process.

AI can analyze large datasets to identify patterns in genetic markers and disease mechanisms, while human experts refine these findings to enhance clinical applicability. Furthermore, AI-driven drug discovery benefits from Design Thinking by enhancing the interpretability and relevance of computational models. While AI can rapidly generate and test molecular structures, the iterative nature of Design Thinking ensures that these models are continuously refined based on experimental validation and real-world clinical insights. This approach enhances the success rate of drug candidates progressing through the development pipeline.

6. Conclusions

The traditional drug discovery pipeline is extremely inefficient, with average development for a single drug taking over 10 years and $2 billion, and less than 15% of drugs gaining FDA approval. Additionally, a lack of diversity in drug development studies leads to increased ADRs (adverse drug reactions) in minorities and women, as the majority of the participants in trials are white males. As patients grow older, they encounter more health problems, and this can lead to the prescription of several non-tailored drugs at once - polypharmacy - and can increase the risk of ADRs.

Using the design thinking framework for drug discovery allows for continued innovation in the field, and emphasizes a patient-centered approach. The use of AI cultivates new ways to advance pharmaceutical development. This method can foster further advancements to improve efficiency, equity, and safety in the field of drug discovery.

Since many new drugs are not tested on minorities and women, 1 in 5 patients experience adverse drug reactions (ADR) to drugs that were not tailored enough46. The integration of AI and design thinking has efficiently improved pharmaceutical system efficiency and fixed operational challenges. The repetitive nature of AI combined with the design thinking process for streamlining development ensures that developed medicines and therapies are human-centered. By focusing deeply on understanding user needs, design thinking allows for more systematic and unconventional solutions. Design thinking also minimizes risk by testing multiple ideas early on in the process, an attribute valuable in patient care.

As our study suggests, incorporating design thinking principles into the prompt engineering with three AI models: ChatGPT, Gemini, and DeepSeek, significantly improved their ability to provide a user-centric and innovative solution to critical issues in the pharmaceutical industry. The responses demonstrated a deeper understanding of the user's needs through the "Empathize" step and incorporated more adaptable solutions. The static and insipid responses that were outputted without design thinking often lacked practicality and feasibility. By leveraging the "ideation" step, responses become more dynamic and diverse. Integrating the design thinking process with LLMs fostered an actionable and creative AI system.

As pharmaceutical research continues to evolve, the integration of AI and Design Thinking will be instrumental in shaping the future of drug development and innovation. This approach ensures that medical advancements remain scientifically robust, ethically sound, and focused on improving patient outcomes, ultimately driving meaningful progress in healthcare.

Supplementary Materials

The supplementary material is included in a separate file.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Sahar Jahanikia; methodology, Sahar Jahanikia.; validation, Sahar Jahanikia.; formal analysis, Sahar Jahanikia; investigation, Sahar Jahanikia; resources, Ava George, Dia Dongara, Divya Raghuraman, Jennifer Li, Maya Bhatia, Neha Nagpal, Sahar Jahanikia; data curation, Ava George, Dia Dongara, Divya Raghuraman, Jennifer Li, Maya Bhatia, Neha Nagpal, Sahar Jahanikia; writing—Ava George, Dia Dongara, Divya Raghuraman, Jennifer Li, Maya Bhatia, Neha Nagpal; writing—review and editing, Sahar Jahanikia; visualization, Ava George, Dia Dongara, Divya Raghuraman, Jennifer Li, Maya Bhatia, Neha Nagpal; supervision, Sahar Jahanikia; project administration, Sahar Jahanikia; funding acquisition, There is no funding for our study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/

supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used ChatGPT, Gemini, and Deepseek for the purposes of data collection. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. The authors would like to acknowledge the Olive Children Foundation and the Aspiring Scholars Directed Research Program Department of Computer Science and Engineering.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| QSAR |

Quantitative structure-activity relationship |

| iPSCs |

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells |

References

- McLaughlin, J. E., Wolcott, M. D., Hubbard, D., Umstead, K., & Rider, T. R. (2019). A qualitative review of the design thinking framework in health professions education. BMC Medical Education, 19(1). [CrossRef]

-

Health care providers can use design thinking to improve patient experiences. (2017, August 31). https://hbr.org/2017/08/health-care-providers-can-use-design-thinking-to-improve-patient-experiences.

- Fortune, J., Burke, J., Dillon, C., Dillon, S., O’Toole, S., Enright, A., Flynn, A., Manikandan, M., Kroll, T., Lavelle, G., & Ryan, J. M. (2022). Co-designing resources to support the transition from child to adult health services for young people with cerebral palsy: A design thinking approach. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, 3. [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, L., Lee, J. H., & Worden, E. A. (2021). Design Thinking for Healthcare: Transliterating the Creative Problem-Solving Method into Architectural practice. HERD Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 14(2), 16–29. [CrossRef]

- Altman, M., Huang, T. T., & Breland, J. Y. (2018). Design thinking in health care. Preventing Chronic Disease, 15. [CrossRef]

- Göttgens, I., & Oertelt-Prigione, S. (2021). The Application of Human-Centered Design Approaches in Health Research and Innovation: A Narrative review of current practices. JMIR Mhealth and Uhealth, 9(12), e28102. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. P., Fisher, T. R., Trowbridge, M. J., & Bent, C. (2016). A design thinking framework for healthcare management and innovation. Healthcare, 4(1), 11–14. [CrossRef]

- Abookire, S., Plover, C., Frasso, R., & Ku, B. (2020). Health Design Thinking: an innovative approach in public health to defining problems and finding solutions. Frontiers in Public Health, 8. [CrossRef]

- Feuerwerker, S., Rankin, N., Wohler, B., Gemino, H., & Risler, Z. (2019). Improving patient satisfaction by using design thinking: Patient advocate role in the emergency department. Cureus. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., & He, Q. (2023). Artificial intelligence and Bioinformatics Applications in precision medicine and future implications. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 9–24). [CrossRef]

- Santa Clara University. (n.d.). Pharmacogenomics, Ethics, and Public Policy. Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. https://www.scu.edu/ethics/focus-areas/bioethics/resources/pharmacogenomics-ethics-and-public-policy/.

- Feldman, K., Suppes, S. L., & Goldman, J. L. (2024). Clarification of adverse drug reactions by a pharmacovigilance team results in increased antibiotic re-prescribing at a freestanding United States children’s hospital. PLoS ONE, 19(1), e0295410. [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. T., & Bussell, J. K. (2011). Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 86(4), 304–314. [CrossRef]

- Varghese, D., Ishida, C., Patel, P., & Koya, H. H. (2024, February 12). Polypharmacy. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532953/.

- Sullivan, T. (2019, March 21). A Tough Road: Cost To Develop One New Drug Is $2.6 Billion; Approval Rate for Drugs Entering Clinical Development is Less Than 12%. Policy & Medicine. https://www.policymed.com/2014/12/a-tough-road-cost-to-develop-one-new-drug-is-26-billion-approval-rate-for-drugs-entering-clinical-de.html.

- Team, C. S. (2023, December 15). Dealing with the challenges of drug discovery. CAS. https://www.cas.org/resources/cas-insights/dealing-challenges-drug-discovery.

- Singh, N., Vayer, P., Tanwar, S., Poyet, J., Tsaioun, K., & Villoutreix, B. O. (2023). Drug discovery and development: introduction to the general public and patient groups. Frontiers in Drug Discovery, 3. [CrossRef]

- Artificial intelligence and machine learning technology driven modern drug discovery and development. (2023). In International Journal of Molecular Sciences (Vol. 24, p. 2026). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9916967/pdf/ijms-24-02026.pdf.

- Sallam, M. (2023). ChatGPT Utility in Healthcare Education, Research, and Practice: Systematic Review on the promising perspectives and valid concerns. Healthcare, 11(6), 887. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J., Yang, Z., Ojima, I., Samaras, D., & Wang, F. (2021). Artificial intelligence in drug discovery: applications and techniques. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 23(1). [CrossRef]

- Zhavoronkov, A., Vanhaelen, Q., & Oprea, T. I. (2020). Will artificial intelligence for drug discovery impact clinical pharmacology? Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 107(4), 780–785. [CrossRef]

- Basile, A. O., Yahi, A., Tatonetti, N. P., & Columbia University Medical Center. (2019). Artificial intelligence for drug toxicity and safety. In Trends Pharmacol Sci (Vols. 40–9, pp. 624–635). [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P., Walters, W. P., Plowright, A. T., Sieroka, N., Listgarten, J., Goodnow, R. A., Fisher, J., Jansen, J. M., Duca, J. S., Rush, T. S., Zentgraf, M., Hill, J. E., Krutoholow, E., Kohler, M., Blaney, J., Funatsu, K., Luebkemann, C., & Schneider, G. (2019). Rethinking drug design in the artificial intelligence era. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 19(5), 353–364. [CrossRef]

- Moingeon, P., Kuenemann, M., & Guedj, M. (2021). Artificial intelligence-enhanced drug design and development: Toward a computational precision medicine. Drug Discovery Today, 27(1), 215–222. [CrossRef]

- MacFadyen, J. S. (2013). Design thinking. Holistic Nursing Practice, 28(1), 3–5. [CrossRef]

- Huang, T. T. K., Aitken, J., Ferris, E., & Cohen, N. (2018). Design thinking to improve implementation of public health interventions: an exploratory case study on enhancing park use. Design for Health, 2(2), 236–252. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., & Esmaeilzadeh, P. (2024). Generative AI in Medical Practice: In-Depth Exploration of privacy and Security challenges. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 26, e53008. [CrossRef]

-

Generative AI vs. Large Language Models (LLMs): What’s the Difference? (n.d.). https://appian.com/blog/acp/process-automation/generative-ai-vs-large-language-models.

-

What is LLM? - Large Language Models Explained - AWS. (n.d.). Amazon Web Services, Inc. https://aws.amazon.com/what-is/large-language-model/.

- Bach, S., & Bach, S. (2025, February 6). Large language model training: how three training phases shape LLMs. Snorkel AI. https://snorkel.ai/blog/large-language-model-training-three-phases-shape-llm-training/.

- https://medium.com/@kamalakshi.deshmukh/white-paper-on-chatgpt-a-comprehensive-overview-ee235c026cea.

- Emote. (2021, July 29). David Kelley: From design to design thinking at Stanford and IDEO - Echos. Echos. https://schoolofdesignthinking.echos.cc/blog/2017/06/david-kelley-from-design-to-design-thinking-at-stanford-and-ideo/.

-

A new collaboration between the Hasso Plattner Institut and HAI brings the human factor of AI to the forefront | Stanford HAI. (n.d.). https://hai.stanford.edu/news/new-collaboration-between-hasso-plattner-institut-and-hai-brings-human-factor-ai-forefront.

- Lugmayr, A., Stockleben, B., Zou, Y. et al. Applying “Design Thinking” in the context of media management education. Multimed Tools Appl 71, 119–157 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Krolikowski, K. A., Bi, M., Baggott, C. M., Khorzad, R., Holl, J. L., & Kruser, J. M. (2022). Design thinking to improve healthcare delivery in the intensive care unit: Promise, pitfalls, and lessons learned. Journal of Critical Care, 69, 153999. [CrossRef]

- Gifford, A., Butcher, B., Chima, R. S., Moore, L., Brady, P. W., Zackoff, M. W., & Dewan, M. (2023). Use of design thinking and human factors approach to improve situation awareness in the pediatric intensive care unit. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 18(11), 978–985. [CrossRef]

- Aboul-Soud, M. a. M., Alzahrani, A. J., & Mahmoud, A. (2021). Induced Pluripotent stem cells (IPSCs)—Roles in regenerative therapies, disease modelling and drug screening. Cells, 10(9), 2319. [CrossRef]

-

Induced pluripotent stem cells and neurological disease models. (2014, February 25). PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24553870/.

- Bindhya, S., Sidhanth, C., Shabna, A., Krishnapriya, S., Garg, M., & Ganesan, T. (2018). Induced pluripotent stem cells: A new strategy to model human cancer. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 107, 62–68. [CrossRef]

- Medvedev, S., Shevchenko, A., & Zakian, S. (2010, July 1). Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: Problems and Advantages when Applying them in Regenerative Medicine. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3347549/.

- Gupta, R., Srivastava, D., Sahu, M., Tiwari, S., Ambasta, R. K., & Kumar, P. (2021). Artificial intelligence to deep learning: machine intelligence approach for drug discovery. Molecular Diversity, 25(3), 1315–1360. [CrossRef]

-

Animals in research. (n.d.). Humane World for Animals. https://www.humaneworld.org/en/issue/animals-in-research.

- Leung, C. M., De Haan, P., Ronaldson-Bouchard, K., Kim, G., Ko, J., Rho, H. S., Chen, Z., Habibovic, P., Jeon, N. L., Takayama, S., Shuler, M. L., Vunjak-Novakovic, G., Frey, O., Verpoorte, E., & Toh, Y. (2022). A guide to the organ-on-a-chip. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Meyers, J., Fabian, B., & Brown, N. (2021). De novo molecular design and generative models. Drug Discovery Today, 26(11), 2707–2715. [CrossRef]

- Kortemme, T. (2024). De novo protein design—From new structures to programmable functions. Cell, 187(3), 526–544. [CrossRef]

- Torres, S. V., Leung, P. J. Y., Venkatesh, P., Lutz, I. D., Hink, F., Huynh, H., Becker, J., Yeh, A. H., Juergens, D., Bennett, N. R., Hoofnagle, A. N., Huang, E., MacCoss, M. J., Expòsit, M., Lee, G. R., Bera, A. K., Kang, A., De La Cruz, J., Levine, P. M., . . . Baker, D. (2023). De novo design of high-affinity binders of bioactive helical peptides. Nature, 626(7998), 435–442. [CrossRef]

- Cherkasov, A., Muratov, E. N., Fourches, D., Varnek, A., Baskin, I. I., Cronin, M., Dearden, J., Gramatica, P., Martin, Y. C., Todeschini, R., Consonni, V., Kuz’min, V. E., Cramer, R., Benigni, R., Yang, C., Rathman, J., Terfloth, L., Gasteiger, J., Richard, A., & Tropsha, A. (2013). QSAR modeling: Where have you been? Where are you going to? Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 57(12), 4977–5010. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, G. (2010). Virtual screening: an endless staircase? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 9(4), 273–276. [CrossRef]

- James, T., & Hristozov, D. (2021). Deep learning and computational chemistry. Methods in Molecular Biology, 125–151. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).