1. Introduction

AI, or artificial intelligence, can be explained as the creation of systems of computers which can perform activities that normally require intelligence matching those of the human levels.All of this requires a broad range of skills, including understanding natural language, identifying patterns, solving challenging issues, and learning from experience (machine learning) [

1]. There are two categories of AI systems: wide or strong AI, which possesses cognitive abilities similar to those of humans, and narrow or weak AI, which is designed for specialized jobs.AI applications are numerous, encompassing multiple areas such as healthcare, finance, manufacturing, and services. The objective is to develop systems capable of doing tasks independently, adapting to new different environments, and continually improving their performance. AI is a crucial engine of innovation in the twenty-first century, affecting different parts of our everyday lives and revolutionizing businesses via automation, data analysis, and advanced decision-making capabilities.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a ubiquitous and transformational force in many sectors in the twenty-first century. AI spurs innovation, changes industries, and impacts the development of society. Particularly evident are its effects on automation, data processing, and decision-making. Data analysis is one of AI's key functions. AI algorithms can sift through enormous databases, extracting crucial insights and supporting well-informed decision-making in the face of the exponential growth of data. In sectors like finance, marketing, and research, this is crucial. Another significant part of AI's participation is automation. Robotics driven by AI enhances production procedures, boosting accuracy and efficiency. Chatbots for customer service are an example of automation; they expedite communication and enhance user experiences.

AI is radically changing patient care, diagnosis, and research, among other sectors of the healthcare industry. AI-powered image analysis has a notable influence on diagnostic efficiency and accuracy. Clinical professionals may now detect small abnormalities with remarkable precision because of machine learning algorithms' quick interpretation of complicated medical images, including MRI's and X-rays [

2]. Moreover, AI makes customized medicine possible by utilizing extensive patient data, such as genetic and medical history, to customize treatment regimens [

3]. Healthcare can take proactive measures to interrupt and perhaps halt the spread of illnesses when diseases are detected early on, thanks to predictive analytics and machine learning. Additionally, it lessens medical mistakes and revises existing research [

4]. Chatbots and virtual health aides [

5], supported by artificial intelligence, improve patient involvement and assistance by offering data, responding to inquiries, and encouraging medication adherence and lifestyle management [

3]. AI is also transforming the process of finding and developing new drugs by identifying possible medication candidates much more quickly and estimating their effectiveness [

6].

With continued development, AI has the potential to improve patient outcomes, streamline healthcare delivery, and spur new ideas to solve persistent problems in themedical industry. There are several obstacles to integrating AI into healthcare systems, including the requirement for legal frameworks, significant implementation costs, and data privacy issues [

7]. Important challenges include ensuring the ethical application of AI [

5], eliminating algorithmic biases, and earning the confidence of medical practitioners. Further obstacles include the interpretability of AI judgments and the difficulty of smoothly incorporating AI into current healthcare operations. Succeeding in integrating AI in healthcare requires striking a balance between ethical issues and technological progress.

2. Literature Review

Relevant obstacles have been found after a search of the literature on the difficulties of using AI in healthcare systems.

Table 1 highlights the key challenges of AI in healthcare.

2.1. Insufficient Data-

Insufficient data is a significant problem in incorporating AI into healthcare since it compromises the quality and generalizability of AI models [

8]. Inaccuracies may occur owing to a lack of varied patient groups, leading in biased predictions and reduced diagnostic accuracy. The lack of extensive data sets [

6] covering unusual medical disorders or recent advances in therapy limits AI systems' capacity to adapt to changing healthcare environments. Data aggregation is hindered by privacy concerns and interoperability challenges, limiting AI's capacity to provide effective solutions [

9]. To overcome the challenge of limited data, it's important to prioritize data sharing, standardization, and ethical concerns while developing AI [

10].

2.2. Social Issues-

Social considerations provide a substantial hurdle to the integration of AI into healthcare. Concerns about equity, transparency [

5], and bias in AI algorithms may exacerbate current healthcare disparities, as these systems may inadvertently favour certain demographic groups over others. Patients and healthcare practitioners disagree on the reliability and ethical implications of AI-generated advice, raising trust and accountability problems. Concerns concerning a lack of emotional availability that aids in patient therapy are also raised [

11]. Furthermore, the potential employment displacement induced by automation in healthcare contexts poses ethical and financial concerns. To ensure that AI applications in healthcare address social challenges, it is necessary to carefully examine algorithmic biases, communicate openly about the technology's limits, and implement regulations that prioritize inclusion.

2.3. Clinical Implementations-

Clinical application is a significant hurdle for introducing AI into healthcare. Despite promising advances in AI technology, successfully integrating these technologies into established healthcare procedures involves overcoming a number of challenges [

4]. Clinicians may struggle to comprehend and trust AI-generated outputs, limiting its use in decision-making processes. Furthermore, integrating AI systems with electronic health records [

12]and other healthcare infrastructure may be difficult, frequently necessitating extensive customization and interoperability concerns. Keeping AI systems compliant with regulatory norms, protecting patient privacy [

4], and addressing ethical concerns all complicate the deployment process.

2.4. High Costs-

The high cost provides a significant barrier to adopting AI into healthcare. Creating, deploying, and sustaining AI systems in healthcare contexts sometimes necessitates significant financial expenditures [

4,

17]. The costs include purchasing modern gear, hiring specialised workers for development and maintenance, and assuring compliance with strict data security and privacy requirements. Training healthcare workers in AI technologies and integrating these systems into existing infrastructures might add to the total economic burden. This cost barrier [

3] may limit the availability of AI-powered healthcare solutions, aggravating existing discrepancies and preventing universal adoption. Addressing the issue of high prices necessitates smart investment planning, collaboration between the public and commercial sectors, and the creation of cost-effective models that assure the long-term integration of AI into healthcare procedures.

2.5. Blackbox Scenario-

Black-box schema occurs when the operations and actions undertaken in a system are not visible or accessible to the user or other interested parties. Because many of the machine learning algorithms are opaque, the black-box situation makes applying AI in healthcare systems difficult [

13]. While these algorithms can successfully process massive quantities of data to generate predictions or aid in medical diagnosis and planning, the lack of openness [

14] about how these judgements are made raises questions about responsibility, trust, and possible biases. In medical care where decisions may have life-or-death effects, doctors must comprehend the logic behind AI suggestions before securely incorporating AI technologies into their practice. Furthermore, legal and ethical norms need openness [

12] and explainability in the process of decision-making, hindering the use of AI in healthcare. To address the black-box dilemma, construct interpretable AI models, rigorous validation procedures, and set explicit rules for transparency and accountability in Artificial intelligence-driven healthcare systems.

2.6. DataAcquisition-

Data collecting is a big difficulty for incorporating AI into the healthcare sector for a variety of reasons. First, healthcare data is frequently dispersed across several systems, in different forms, and with varied degrees of standardization, making it difficult to combine and harmonize for AI applications [

4] Second, concerns with inter-operability across various healthcare platforms impede the seamless sharing of information. Third, concerns about patient privacy and data security result in severe rules that limit the sharing and use of healthcare data for AI research. Furthermore, the data quality, it’s accuracy [

15]and completeness might vary, affecting the performance and generalizability of artificial intelligence models. To address these difficulties, efforts must be made to improve data inter-operability, implement strong privacy rules, and encourage collaboration across healthcare organizations to construct complete and representative.

2.7. IntroductionofInnovative and New Generation Tools-

The implementation of novel and next-generation technologies [

13] for integrating AI into the healthcare industry meets several hurdles. First, there is sometimes opposition to change inside existing healthcare systems, including personnel who are used to old techniques. The deployment of new instruments and technologies necessitates extensive training and a cultural shift in the way healthcare personnel approach their jobs and also on how well they are incorporated in the system [

16]. Second, the expense of implementing and integrating these cutting-edge technology might be prohibitively expensive, creating financial issues [

18]for healthcare organisations. Third, guaranteeing these technologies' compatibility with current systems and infrastructure is a challenging undertaking. Furthermore, regulatory frameworks may not always keep up with quickly emerging technologies, resulting in questions about compliance and standards.

2.8. Missing Compassion -

One of the obstacles in incorporating AI into the healthcare sector is that computer interactions may lack compassion when compared to human interactions. While AI systems excel at analyzing vast amounts of data and drawing unbiased findings, they might not be able to convey empathy or emotional understanding, which is crucial in the healthcare industry [

11]. Patients frequently expect healthcare practitioners to communicate compassionately and empathetically [

4] in addition to providing accurate diagnosis and treatment strategies. In healthcare, the human touch entails interpreting emotional cues, offering comfort, and tailoring communication to individual requirements. The difficulty is in striking a balance between the efficiency and objectivity of AI technologies and the compassionate, human-centered treatment that patients demand. Healthcare practitioners must develop methods to smoothly integrate AI while preserving the critical human factors that lead to a pleasant patient experience and therapeutic connections. This entails carefully planning the design and implementation of AI systems to supplement, rather than replace, the sympathetic components of healthcare delivery.

2.9. DataMisuse-

Data misuse is a big concern when incorporating AI into the healthcare industry. The large amount of sensitive patient information involved in healthcare makes it a tempting target for hostile activity if not handled with extreme caution. Unauthorized access, data breaches [

9], and incorrect sharing of health data are all examples of serious privacy infractions that can hurt individuals. AI integration necessitates the collecting, storage, and processing of huge datasets, hence strong security measures must be implemented. Furthermore, the possibility of biases and biased outcomes in AI systems might worsen current healthcare inequities [

4]. Ensuring ethical procedures, robust security standards, and respect to privacy legislation are vital in limiting the danger of data exploitation, creating confidence between patients and healthcare.

2.10. Data Privacy and Security-

Data privacy and security are important problems when incorporating AI into the medical sector [

9]. Healthcare systems handle extremely sensitive and private patient data, making them prime candidates for cyberattacks and unauthorized access. The sheer extent and complexity of healthcare data, which frequently includes electronic health records, diagnostic pictures, and genetic information, heightens the danger of data breaches. Inadequate security measures can have serious repercussions, such as identity theft, financial fraud, and breached patient confidentiality [

10]. Furthermore, AI integration may entail sharing and analyzing data across several platforms, which increases the potential attack surface [

7]. It is critical to strike a balance between making data more accessible for AI applications and providing strong privacy measures. Stringent adherence to data protection legislation, the use of encryption technology, and the establishment of standardize security standards are critical components in resolving these issues and establishing confidence among patients, medical professionals, and regulators.

2.11. Technology Development-

For a variety of reasons, technological advancement makes incorporating AI into the healthcare industry challenging. First, the rapid rate of technology progress necessitates that healthcare personnel constantly upgrade their abilities and adjust to new equipment and procedures. Training and instruction are required to guarantee that medical professionals can properly use AI technologies. Second, the creation and implementation of AI systems sometimes require large financial commitments, making it difficult for some healthcare organizations, particularly the smaller ones, to purchase and apply cutting-edge technology. In addition, guaranteeing the interoperability of artificial intelligence solutions with current health IT infrastructure is a difficult undertaking since disparate systems may not connect properly. Finally, the healthcare business is highly regulated and the development of AI systems must adhere to stringent ethical and legal norms, necessitating careful navigation of regulatory structures. Addressing these problems will need continuing education, monetary considerations, cooperation among technology developers and medical professionals, and compliance to regulatory rules to ensure the proper integration of AI in healthcare.

Table 2.

Notations of the different challenges identified in the study.

Table 2.

Notations of the different challenges identified in the study.

| Serial No |

Notations |

Different Challenges |

| 1 |

ID |

INSUFFICIENT DATA |

| 2 |

SI |

SOCIAL ISSUES |

| 3 |

CI |

CLINICAL IMPLEMENTATION |

| 4 |

HC |

HIGH COST |

| 5 |

BS |

BLACKBOX SCENARIO |

| 6 |

DA |

DATA AQUISITION |

| 7 |

IIN |

INTRODUCTION OF INNOVATIVE AND NEW GENERATION TOOLS |

| 8 |

MC |

MISSING COMPASSION |

| 9 |

DM |

DATA MISUSE |

| 10 |

DPS |

DATA PRIVACY AND SECURITY |

| 11 |

TD |

TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT |

3. Methodology

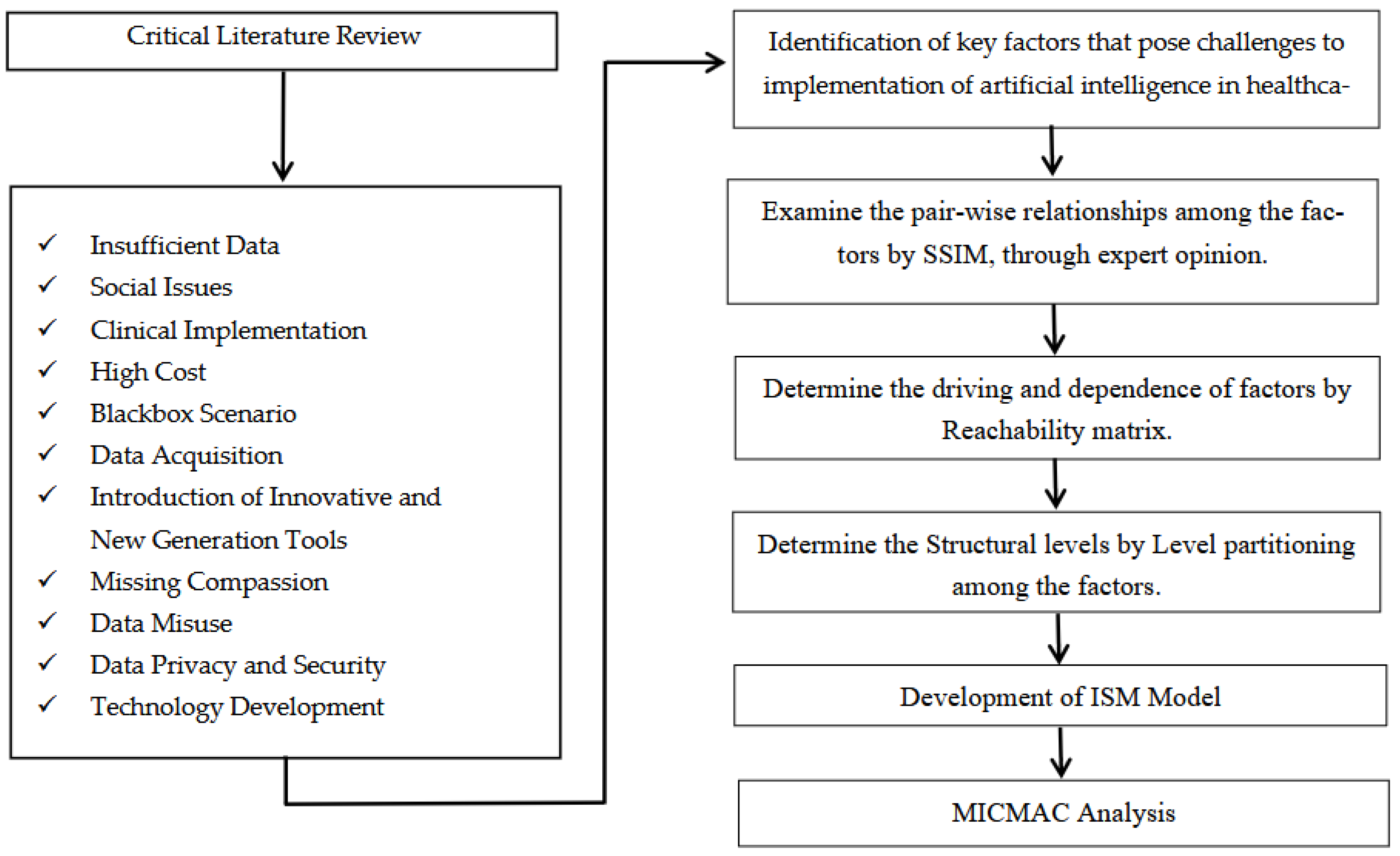

To achieve the aims outlined in this work, the writers took a series of actions. First, the essential components are determined using a thorough literature research and expert comments. After that, a model based on ISM is developed to examine the connections between the various parts. Finally, MICMAC analysis is employed to classify them. This is the study framework shown in

Figure 1.

3.1. Data Collection

Initially, the authors conducted extensive literature research to learn about Artificial Intelligence and identify where all AI could be implemented in the healthcare sector.

The authors then examined research databases using key terms like Artificial Intelligence, healthcare sector, medicine, automation and ISM. Then, the abstracts from all retrieved papers were evaluated to identify appropriate research for the concerned research. Further, the specialists were tasked with evaluating a list of major factors that elucidate the advantages and challenges that AI poses in medical industry. We had the honor of interacting with 12 experts, all from various medical backgrounds from 4 government and 3 private institutions. They provided us with their valuable insights which served as the foundation of our study (for the key factors) for the ISM model.

Figure 1.

The different steps followed for the framework of the study.

Figure 1.

The different steps followed for the framework of the study.

Our twelve experts included seven doctors cum academicians from different departments like oncology, radiology, paediatrics, neurology, gynaecology, ophthalmology, and cardiology,and two having pharmaceutical background, two medical technicians and a head-nurse. The selected experts have vast experience in medicine from day-to-day handling and from their research knowledge too. They helped in pointing out where all automation could be enabled to facilitate daily processes. They also laid out the common challenges that would come up while establishing automation in healthcare. ISM does not impose any restrictions on the sample size of experts, hence the number of experts chosen for this investigation is adequate. Furthermore, other studies have considered a comparable sample size. Expert participation in this study is adequate, according to previous research [

19,

20].

3.2. Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM)-

ISM is a process for determining and summarizing the connections between various elements that comprise a problem or issue. An interactive method that takes expert advice into account is used to build the connections between the parts of a complex system [

21,

22]. Compared to other methods such as Delphi and structural equation modelling, ISM has the benefit of requiring fewer professionals and yielding a structured model from unstructured and ambiguous raw collection of data.

The ISM technique aims to constitute strong relationships between the many aspects of a problem. ISM transforms an ambiguous and unstructured model into one that is well-defined and structured [

23].It offers an open perspective on the problem and concentrates on the factors' direct and indirect relationships [

24]. Additionally, it highlights the aspects of a problem that are both short- and long-term oriented [

22]. To create a managerial vision quickly, ISM efficiently arranges the expert perspectives and in-depth knowledge [

25,

26].

Table 3.

Demonstrates how modern scholars have applied ISM to decision making in a variety of domains.

Table 3.

Demonstrates how modern scholars have applied ISM to decision making in a variety of domains.

| Resources |

Objectives |

| Iqbal et al., 2023 [27] |

Energy efficient supply chain in construction industry |

| Akpinar et al., 2023 [28] |

Resilience in maritime business |

| Agarwal et al., 2023 [29] |

Adoption of solar renewable energy products in India |

| Gadekar et al., 2024 [30] |

Study of the inhibitorsthat affect Industry 4.0 implementationin manufacturing industries of India |

| Asif et al., 2024 [31] |

Dairy supply chain |

| Feng et al., 2024 [32] |

Digital innovation in manufacturing enterprises |

This research establishes the important variables that pose as challenges in implementing artificial intelligence in healthcare sector, hence making ISM one of the most befitting methods for this study.The framework is an appropriate choice since this methodology gives a group a way to impose an order on the items' complexity. ISM has many benefits, including the ability to combine expert opinions and knowledge bases in a methodical manner while allowing for frequent judgement change. For targets (items) with ten to fifteen numbers, the computational effort required is quite low, and it can be a useful tool in practical applications. Additionally, the ISM model's outcomes could be impacted by the experts' biased assessments, which could be mitigated by the experts' breadth and depth of expertise in providing objective comments. As a strategy for implementation of automation in an ever-changing medical archetype,ISM is a dependable technique for our investigation in determining as well as creating a framework to illustrate the difficulties and solutions faced by industries in generating revenue.

This procedure is followed by the ISM method. Expert judgement from the factors that were found was first used to create a structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM). After that, a reachability matrix was created to ascertain the inter-dependencies and driving forces behind the factors that were found. Third, the factors were divided into levels using a reachability matrix; Fourth, an interpretive structural model (ISM) was created; and, Lastly, the factors were classified into four different groups on the basis of their driving forces and dependencies: autonomous, dependent, linkage, and driver using MICMAC analysis.

3.2.1. Structural Self Interaction Matrix (SSIM)

The writers were able to construct the contextual interaction among the components with the valuable input of fifteen professionals from business and academics. The SSIM was developed when the pair-wise comparison data amongst the different factors were received. The relationships’ nature between two factors (x and y) is represented by the four symbols as below: The following scenarios occur: (i) V happens when x affects y; (ii) A happens when y effects x; (iii) X happens when x and y interact; (iv) O happens when x and y are unrelated.

Table 4 presents the SSIM matrix for the primary factors hindering the adoption of artificial intelligence in the medical sector, which is on the basis of the opinions of experts using the four symbols mentioned above. This SSIM is necessary for the reachability matrix to function.

3.2.2. Reachability Matrix

The SS1M yields the reachability matrix, which is produced by substituting 1 and 0 for V, A, X, and O. The norms that control the replacement of 1s and 0s are as follows: Reachability matrix: (i) if the (x,y) position in the SSIM matrix is symbolized by V; (ii) if the (x,y) position is symbolized by A; (iii) if the (x,y) position is symbolized by X in the SSIM matrix and 1, correspondingly; (iv) In the reachability matrix, the (x,y) and (y,x) positions will be 0 and 0 respectively if the (x,y) location in the SSIM matrix is represented by 0. It respects transitivity as well. The first of the factor leads to the third factor if the first factor leads to the second factor and the second factor leads to the third factor, in accordance with the principle of transitivity. The resulting reachability matrix is shown in

Table 4. The relationships between and motivations for each component are also depicted in this reachability matrix.

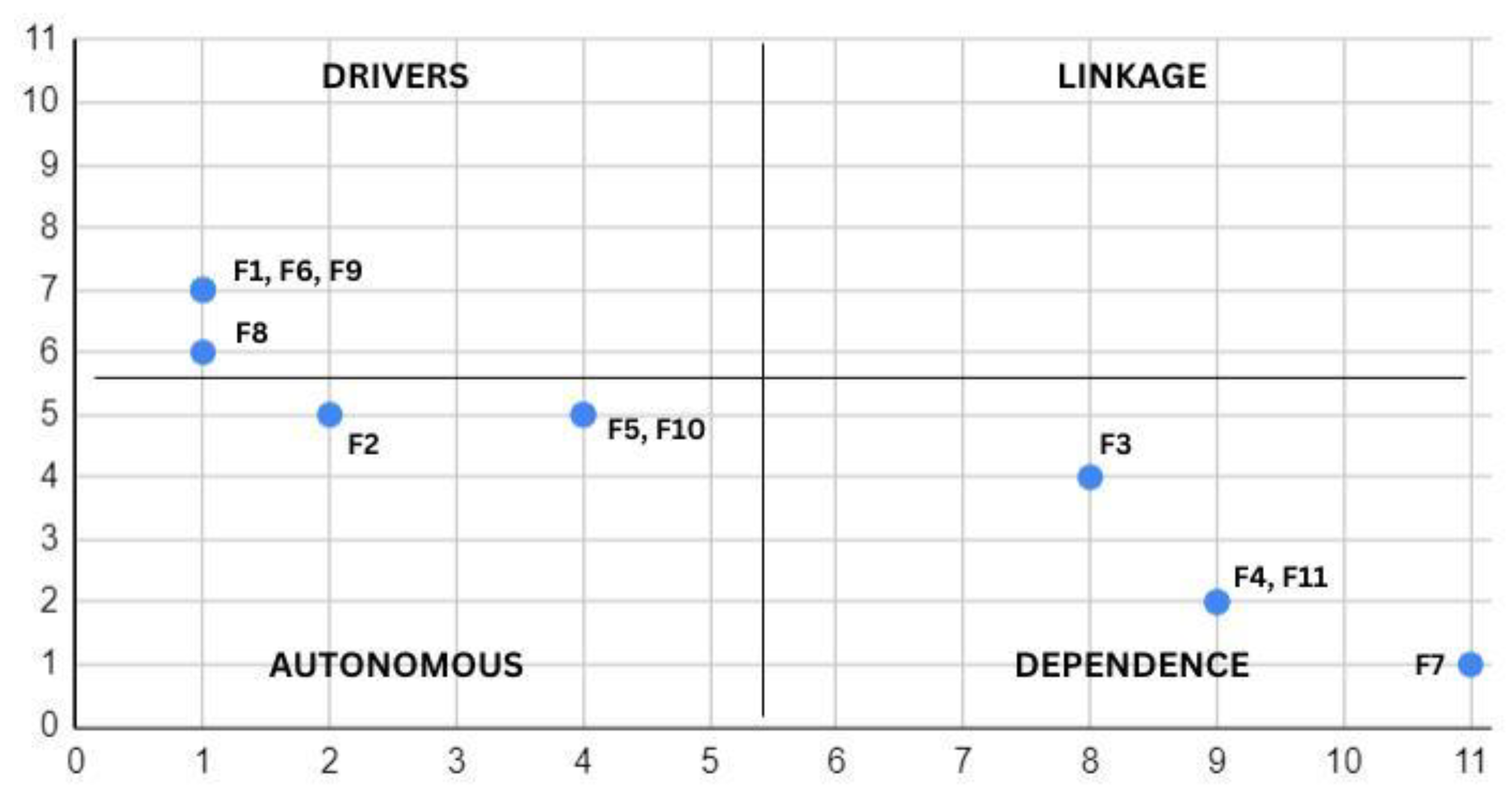

In this analysis, factors 7 and 1, 6, 9 show the highest levels of dependency and driving power, respectively. The driving force and dependency of each factor help with the MICMAC analysis, as represented in

Table 5.

3.2.3. LevelPartition

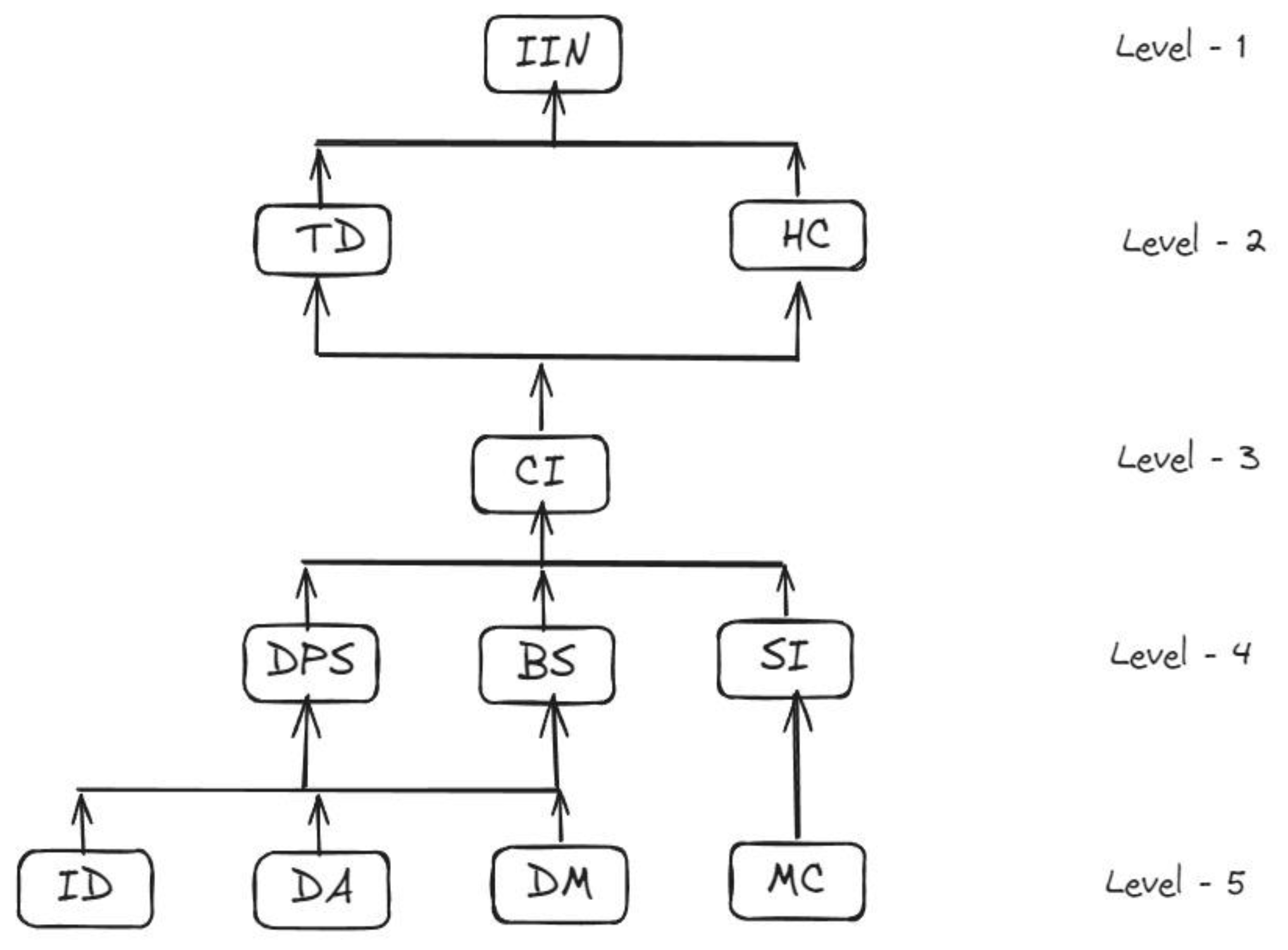

Using the reachability matrix, step three entails determining the reachability set and antecedent set for each factor. The same factor and other aspects that are impacted by it make up reachability sets, and the same factor and other elements that are influencing to accomplish that factor make up antecedent sets. The shared component or factors between the antecedent set and the reachability set are referred to as the "intersection set". Level one is established when the values of the intersection set and reachability set coincide. In this study, the intersection and reachability sets have the same value for factor 5. Factor IIN is therefore viewed as level one and is shown in

Figure 2.

After obtaining the level one, or top-level, factor, it will be segregated from other components. Similar outcomes will be reported for the remaining component levels. The final ISM model shall be created with the help of the specified level.

Table 6 displays the reachability set, antecedent set, intersection set, and level for each factor. This study identified five levels, with component F1 relating to level 1 and factor F5 belonging to level 5.

3.2.4. Formation of Interpretive Structural Model (ISM)

The ISM-based model, that is created by using a level partition table and digraph, is displayed in

Figure 3. The inter-connectedness of the factors is represented by the digraph's nodes and edges. The ISM model is generated by the lines of edges and vertices, or nodes, from the final reachability matrix [

33]. A relation between factors x and y is represented as an arrow pointing from x to y. Finally, the digraph is converted to the ISM model by taking the transitivities out. The ISM model presents the structural relationship between the important components [

34].

3.2.5. MICMAC Analysis

The driving powers and dependence diagram are also known as MICMAC (Cross-Impact Matrix Multiplication Applied to Classification) analysis. The determined driving powers and dependencies serve as the infix for the MICMAC analysis [

35]. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the identified critical elements that were previously defined are categorized into four quadrants:(i) The factors in the first quadrant are mentioned as autonomous factors because they have low driving powers and low dependency; (ii) The factors of the second quadrant are cited as dependent factors as they have low driving powers and high dependency; (iii)Third quadrant factors are named as linkage factors because they have high dependency and high driving powers; (iv) Fourth quadrant factors are mentioned as drivers because they have high dependency and low driving powers [

36].

Figure 3.

Micmac Analysis.

Figure 3.

Micmac Analysis.

4. Results

Eleven challenges were carefully studied and identified that were seen to obstruct in the successful integration of artificial intelligence in healthcare sector. In this, ISM modelling has been adopted to construct and analyse these limitations. Insufficient Data (IN), Data Acquisition (DA), Data Misuse (DM) and Missing Compassion (MC) are the independent driving factors, while Introduction of innovative and new generation tools (IIN) tops the chart by being the most dependent and driven factor among the ones under study.

Obstacles present in level five are Insufficient Data (IN), Data Acquisition (DA), and Data Misuse (DM) which imply that the foundational issues in creating an artificial intelligence integrated healthcare sector is the availability of data and its collection. It also includes Missing Compassion (MC) which indicates towards the reduction of human emotions and interaction when the AI is introduced. Next in the fourth tier, there are Data Privacy and Security (DPS), Black-box Scenario (BS) and Social Issues (SI). Data Privacy and Security (DPS) and Black-box Scenario (BS) pose a huge threat as it could lead to the disruption of the entire healthcare system by challenging its authenticity. Social Issues (SI) on the other hand, not only create hindrances in terms of emotional understanding but also disable the ability of understanding and comprehending the pains and troubles of an ailing patient. Next in tier three comes Clinical Implementation (CI).While integrating artificial intelligence in the medical sector, one big challenge occurs in installation of the entire automation system in reality. With all the infrastructural changes, software requirements and data necessities, shifting from our current modes of working and usage to the new automated is a daunting task. Moreover, for doctors and other healthcare sector workers, trusting the diagnosis and results of a system generated response in matters of life and death can also be very difficult. In tier two, the challenges recorded are Technological Development (TD) and High Cost (HC). While the development progress of technology is rapidly increasing and easing things, it creates hurdles because the users of the same, in this case the doctors, nurses, and medical technicians, have to be aware of how to use the same as per the advancements. High Cost (HC) on the other hand, determines the feasibility of the switch. While switching the existing system into the more advanced versions quite necessary, the possibility of turning it into reality depends on the affordability criterias. At last, Introduction of Innovative and New Generation Tools (IIN), in tier one, causes troubles in changing the system. Aside from the requirements to change the infrastructure, the financial requirements, and the technological advancements, one of the most important factors that is needed to make the integration of artificial intelligence into the existing healthcare system a success is the government policies and frameworks. The entire research model can be divided four different categories, i.e. Autonomous, Dependence, Drivers and Linkage. The autonomous factors include Social Issues (SI), Black-box Scenario (BS), and Data Privacy and Security (DPS). These variables exhibit poor drive and dependence power. They are detached from the system and have few strong connections.Factors- clinical Implementation (CI), High Cost (HC), Introduction of Innovative and New Generation Tools (IIN) and Technological development (TD) fall in the dependent category as they are weak drivers but have strong dependence power. Factors- Insufficient Data (ID), Data Acquisition (DA), Missing Compassion (MC) and Data Misuse (DM) lie in the Drivers’ category. These factors have strong driving power and weak dependence power. The last category includes linkage factors which include the factors that act as both strong drivers as well as ones with strong dependence characteristics. However, none of the factors discussed above belong to this category in our study.

5. Conclusions

Finally, the operation of AI in medical care holds both gravid potency and severe hurdles. While AI technologies have the potential to improve diagnosis, treatment planning, and patient care, data privacy concerns, cost, clinical implementation and ethical considerations constitute of the top priorities. The complexity of healthcare systems, along with the requirement for rigorous validation and interoperability of AI solutions, emphasizes the need of collaborative attempts between researchers, medical practitioners, policymakers, and technology developers. Addressing these issues necessitates a multifaceted strategy that prioritizes openness, accountability, and patient-centeredness. Despite the challenges, ongoing progress and appropriate use of AI have the potency to transform healthcare delivery and enhance patient outcomes on a worldwide scale.

This paper provides scope for further study and research on several other aspects. First, the policies and laws that the governments formulate for the usage, set-up, and implementation of artificial intelligence in healthcare industries. Especially, taking into consideration, the privacy concerns, and the rights protecting it. Second, the paper incorporates only some selected factors that pose as challenges while integrating artificial intelligence in medical sector. Third, it also allows further study scope in infrastructure and software needed to successful automate the medical sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A. and S.T.; methodology, A. and D.S.; validation, K.B., H.C.K. and S.S.; formal analysis, A. and S.S.; investigation, K.B., S.T and D.S; resources, K.B., H.C.K. and S.S.; data curation, A., K.B. and H.C.K; writing—original draft preparation, A.; writing—review and editing, S.T., D.S and S.S.; visualization, A. and D.S.; supervision, S.T., H.C.K, and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

All the participants gave their consent to participate in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Zahlan, A., Ranjan, R. P., & Hayes, D. (2023). Artificial intelligence innovation in healthcare: Literature review, exploratory analysis, and future research. Technology in Society, 102321. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J., Sprivulis, P., & Dwivedi, G. (2018). Artificial intelligence and machine learning in emergency medicine. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 30(6), 870-874. [CrossRef]

- Jimma, B. L. (2023). Artificial intelligence in healthcare: A bibliometric analysis. Telematics and Informatics Reports, 9, 100041. [CrossRef]

- Aung, Y. Y., Wong, D. C., & Ting, D. S. (2021). The promise of artificial intelligence: a review of the opportunities and challenges of artificial intelligence in healthcare. British medical bulletin, 139(1), 4-15. [CrossRef]

- Gille, F. Gille, F., Jobin, A., & Ienca, M. (2020). What we talk about when we talk about trust: theory of trust for AI in healthcare. Intelligence-Based Medicine, 1, 100001.

- Paul, D., Sanap, G., Shenoy, S., Kalyane, D., Kalia, K., &Tekade, R. K. (2021). Artificial intelligence in drug discovery and development. Drug discovery today 26(1), 80–93.

- Sun, T. Q., & Medaglia, R. (2019). Mapping the challenges of Artificial Intelligence in the public sector: Evidence from public healthcare. Government Information Quarterly, 36(2), 368-383. [CrossRef]

- Neyigapula, B. S. (2023). AI in Healthcare: Enhancing Diagnosis, Treatment, and Healthcare Systems for a Smarter Future in India. Adv Bioeng Biomed Sci Res, 6(10), 171-177.

- Bartoletti, I. (2019). AI in healthcare: Ethical and privacy challenges. In Artificial Intelligence in Medicine: 17th Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, AIME 2019, Poznan, Poland, June 26–29, 2019, Proceedings 17 (pp. 7-10). Springer International Publishing.

- Shah, R., & Chircu, A. (2018). IoT and AI in healthcare: A systematic literature review. Issues in Information Systems, 19, 3.

- Khaled, N., Turki, A., & Aidalina, M. (2019). Implications of artificial intelligence in healthcare delivery in the hospital settings. International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 6(5), 22–38. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S., Fox, J., & Purohit, M. P. (2019). Artificial intelligence-enabled healthcare delivery. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 112(1), 22-28. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. C., Chen, T. C. T., & Chiu, M. C. (2023). An improved explainable artificial intelligence tool in healthcare for hospital recommendation. Healthcare Analytics 3, 100147. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasu, P. N. Srinivasu, P. N., Sandhya, N., Jhaveri, R. H., & Raut, R. (2022). From blackbox to explainable AI in healthcare: existing tools and case studies. Mobile Information Systems, 2022, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, B., Kinoshita, T., Peebles, A., Graber, M. A., & Lee, S. (2022). Artificial intelligence and machine learning in emergency medicine: a narrative review. Acute medicine & surgery, 9(1), e740. [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, A. D., Verboom, D. E., dos Santos, N. R., & de Graaf, J. W. (2023). The impact of artificial intelligence on the tasks of mental healthcare workers: A scoping review. Computers in Human Behaviour: Artificial Humans, 100008.

- Bertsimas, D., Bjarnadóttir, M. V., Kane, M. A., Kryder, J. C., Pandey, R., Vempala, S., & Wang, G. (2008). Algorithmic prediction of health-care costs. Operations Research, 56(6), 1382-1392. [CrossRef]

- Van Mens, K., Kwakernaak, S., Janssen, R., Cahn, W., Lokkerbol, J., & Tiemens, B. (2022). Predicting future service use in Dutch mental healthcare: a machine learning approach. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 49(1), 116-124. [CrossRef]

- Mangla, S. K., Luthra, S., Mishra, N., Singh, A., Rana, N. P., Dora, M., & Dwivedi, Y. (2018). Barriers to effective circular supply chain management in a developing country context. Production Planning & Control, 29(6), 551-569. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A., Dutta, P., & Kakoti, S. (2020). Exploring key success factors of Indian pharmaceutical supply chain using interpretive structural modelling. In multi-criteria decision analysis in management (pp. 46-61). IGI Global.

- Diabat, A., & Govindan, K. (2011). An analysis of the drivers affecting the implementation of green supply chain management. Resources, conservation and recycling 55(6), 659–667. [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, S., Sahu, S., & Ray, P. K. (2013). Interpretive structural modelling for critical success factors of R&D performance in Indian manufacturing firms. Journal of Modelling in Management, 8(2), 212-240. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, K., Mondal, S., & Mukherjee, K. (2019). Critical analysis of enablers and barriers in extension of useful life of automotive products through remanufacturing. Journal of Cleaner Production 227, 1117–1135. [CrossRef]

- Sushil. (2012). Interpreting the interpretive structural model. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management 13, 87–106. [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, J., Deshmukh, S. G., Gupta, A. D., & Shankar, R. (2005). Selection of third-party logistics (3PL): A hybrid approach using interpretive structural modeling (ISM) and analytic network process (ANP). Supply Chain Forum: International Journal, 6(1), 32–46. [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, J., Deshmukh, S. G., Gupta, A. D., & Shankar, R. (2007). Development of balanced scorecard: An integrated approach of interpretive structural modelling (ISM) and analytic network process (ANP). International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 56(1), 25–59.

- Iqbal, M., Ma, J., Ahmad, N., Ullah, Z., & Hassan, A. (2023). Energy-Efficient supply chains in construction industry: An analysis of critical success factors using ISM-MICMAC approach. International Journal of Green Energy, 20(3), 265-283. [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, H., & Ozer Caylan, D. (2023). Modeling organizational resilience in maritime business: an ISM and MICMAC approach. Business Process Management Journal, 29(3), 597-629. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R., Bhadauria, A., Kaushik, H., Swami, S., &Rajwanshi, R. (2023). ISM-MICMAC-based study on key enablers in the adoption of solar renewable energy products in India. Technology in Society, 75, 102375.

- Gadekar, R., Sarkar, B., & Gadekar, A. (2024). Model development for assessing inhibitors impacting Industry 4.0 implementation in Indian manufacturing industries: an integrated ISM-Fuzzy MICMAC approach. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 15(2), 646-671. [CrossRef]

- Asif, M., Sarim, M., Khan, W., & Khan, S. (2024). ISM-and MICMAC-based modelling of dairy supply chain: a study of enablers in Indian economy perspective. British Food Journal, 126(2), 578-594. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X., Li, E., & Li, J. (2024). Critical factors identification of digital innovation in manufacturing enterprises: three stage hybrid DEMATEL–ISM–MICMAC approach. Soft Computing, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K., Palaniappan, M., Zhu, Q., & Kannan, D. (2012). Analysis of third partyreverse logistics provider using interpretive structural modeling. International Journal of Production Economics 140, 204–211.

- Attri, R., Dev, N., & Sharma, V. (2013). Interpretive structural modelling (ISM) approach: an overview. Research journal of management sciences, 2319(2), 1171.

- Sivaprakasam, R., Selladurai, V., & Sasikumar, P. (2015 Oct 1). Implementation of interpretive structural modelling methodology as a strategic decision-making tool in a Green Supply Chain Context. Annals of Operations Research, 233(1), 423–448. [CrossRef]

- Raj, T., Shankar, R., & Suhaib, M. (2008). An ISM approach for modelling the enablersof flexible manufacturing system: The case for India. International Journal of Production Research, 46(24), 6883–6912.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).