Submitted:

03 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Main

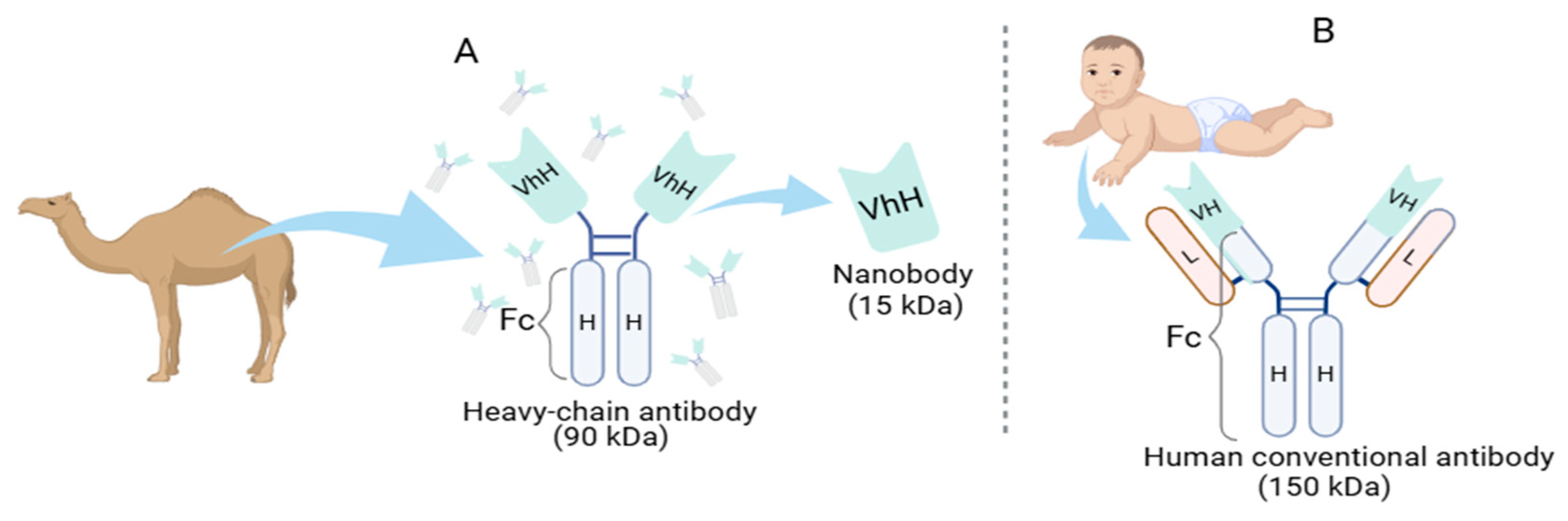

How Are Nanobodies Structured, and What Are Their Properties?

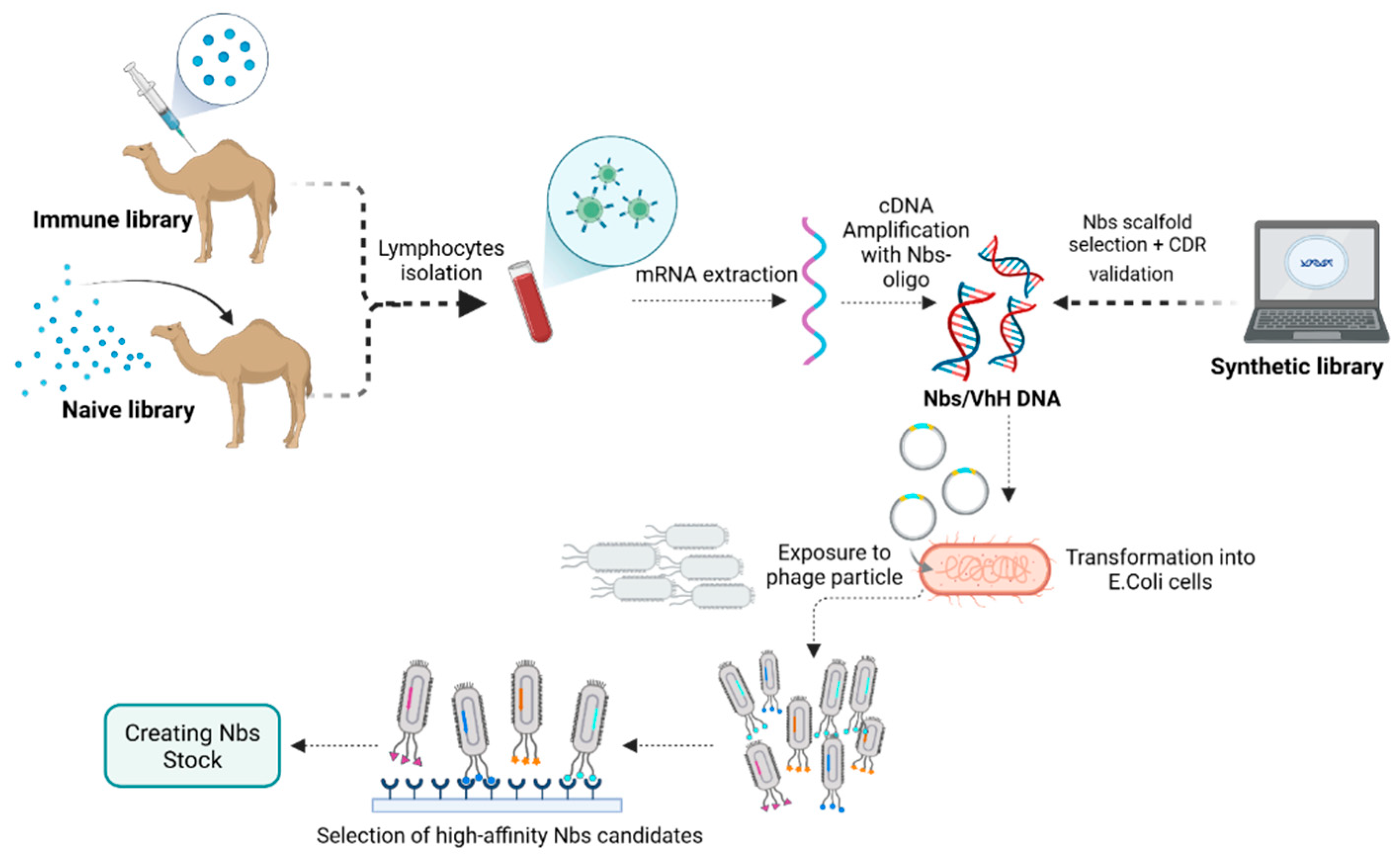

Overview of Nanobody Generation

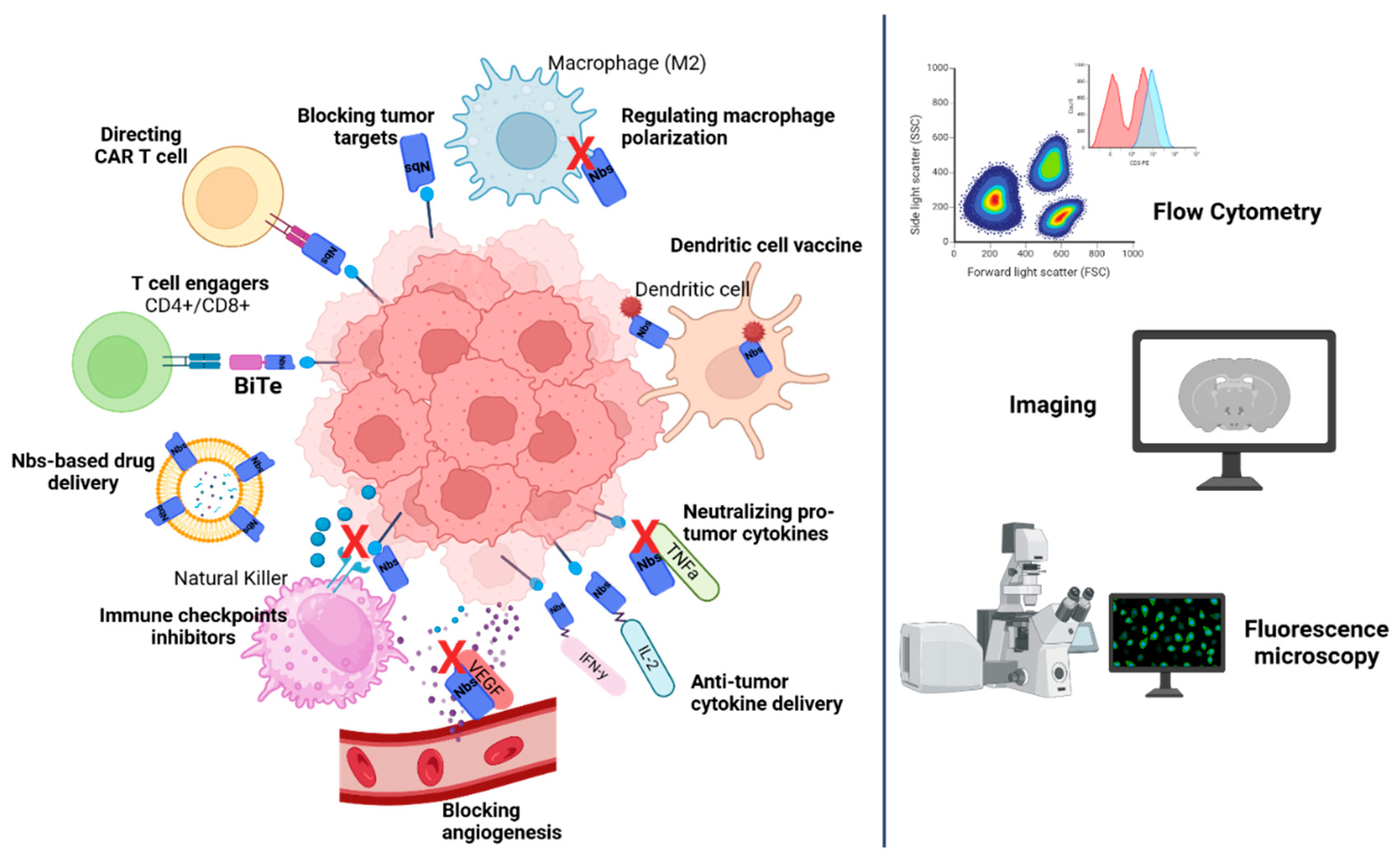

Applications: Nanobody-Based Strategies for Cancer

Why Nanobody-Based Cancer Therapies?

Tumor Targets

Nanobodies as Modulators of Checkpoint Inhibitors

Dendritic Cell Vaccine Based on Nanobody

Nanobodies Engineering for CAR-T Technology

Nanobody-Based Drug Delivery

Nanobody-Drug Conjugates

Nanobodies-Based Viral Vectors

T Cell Engagers

Limitations of Nanobody-Based Therapy

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

References

- Köhler, G.; Milstein, C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature 1975, 256, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Portilla, P.A.; et al. Nanoanticuerpos: Desarrollo biotecnológico y aplicaciones. TIP. Rev. Esp. Cienc. Quím.-Biol. 2021, 24, e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamers-Casterman, C.; et al. Naturally occurring antibodies devoid of light chains. Nature 1993, 363, 446–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, W.; et al. Nanobody conjugates for targeted cancer therapy and imaging. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 20, 15330338211010116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyldermans, S. Nanobodies: Natural single-domain antibodies. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013, 82, 775–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdés-Tresanco, M.S.; Molina-Zapata, A., Pose; Moreno, E. Structural insights into the design of synthetic nanobody libraries. Molecules 2022, 27, 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, E.; Leong, K.W. Discovery of nanobodies: A comprehensive review of their applications and potential over the past five years. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; et al. Recent advances in the selection and identification of antigen-specific nanobodies. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 96, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, S. Caplacizumab: First Global Approval. Drugs 2018, 78, 1639–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyaerts, M.; et al. Phase I study of 68Ga-HER2-Nanobody for PET/CT assessment of HER2 expression in breast carcinoma. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roovers, R.C.; et al. Efficient inhibition of EGFR signalling and of tumour growth by antagonistic anti-EGFR Nanobodies. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2007, 56, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossotti, M.A.; et al. Camelid single-domain antibodies raised by DNA immunization are potent inhibitors of EGFR signaling. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardiola, S.; et al. Blocking EGFR activation with anti-EGF nanobodies via two distinct molecular recognition mechanisms. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 13843–13847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; et al. Human domain antibodies to conserved epitopes on HER2 potently inhibit growth of HER2-overexpressing human breast cancer cells in vitro. Antibodies 2019, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araste, F.; et al. A novel VHH nanobody against the active site (the CA domain) of tumor-associated, carbonic anhydrase isoform IX and its usefulness for cancer diagnosis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2014, 36, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghnezhad, G.; et al. Identification of new DR5 agonistic nanobodies and generation of multivalent nanobody constructs for cancer treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godar, M.; et al. Dual anti-idiotypic purification of a novel, native-format biparatopic anti-MET antibody with improved in vitro and in vivo efficacy. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosjan, M.J.W.D.; et al. Nanobodies targeting the hepatocyte growth factor: Potential new drugs for molecular cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2012, 11, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martín, D.; et al. Proteasome activator complex PA28 identified as an accessible target in prostate cancer by in vivo selection of human antibodies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 13791–13796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonaert, L.; et al. Identification and characterization of nanobodies targeting the EphA4 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 11452–11465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.M.; et al. Single domain antibody against carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 6 (CEACAM6) inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion and angiogenesis of pancreatic cancer cells. Eur. J. Cancer 2014, 50, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samec, N.; et al. Glioblastoma-specific anti-TUFM nanobody for in-vitro immunoimaging and cancer stem cell targeting. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 17282–17299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; et al. Protein C receptor is a therapeutic stem cell target in a distinct group of breast cancers. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 832–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, R.; et al. Screening and antitumor effect of an anti-CTLA-4 nanobody. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 39, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozan, C.; et al. Single-domain antibody-based and linker-free bispecific antibodies targeting FcgRIII induce potent antitumor activity without recruiting regulatory T cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013, 12, 1481–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. A GPC3-targeting bispecific antibody, GPC3-S-Fab, with potent cytotoxicity. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 12, 57588. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; et al. Single domain based bispecific antibody, Muc1-Bi-1, and its humanized form, Muc1-Bi-2, induce potent cancer cell killing in Muc1 positive tumor cells. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homayouni, V.; et al. Preparation and characterization of a novel nanobody against T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-3 (TIM-3). Iran J. Basic Med. Sci. 2016, 19, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; et al. Preclinical development of a novel CD47 nanobody with less toxicity and enhanced anti-cancer therapeutic potential. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farajpour, Z.; et al. A nanobody directed to a functional epitope on VEGF, as a novel strategy for cancer treatment. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 446, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodabakhsh, F.; et al. Development of a novel nano-sized anti-VEGFA nanobody with enhanced physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 1402–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behdani, M.; et al. Generation and characterization of a functional nanobody against the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2; angiogenesis cell receptor. Mol. Immunol. 2012, 50, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharlou, R.; et al. An antibody fragment against human delta-like ligand-4 for inhibition of cell proliferation and neovascularization. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2018, 40, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatibi, A.S.; et al. Tumor-suppressing and anti-angiogenic activities of a recombinant anti-CD3ϵ nanobody in breast cancer mice model. Immunotherapy 2019, 11, 1555–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyvaerts, C.; et al. Targeting of human antigen-presenting cell subsets. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 11304–11308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyvaerts, C.; et al. Antigen-presenting cell-targeted lentiviral vectors do not support the development of productive T-cell effector responses: Implications for in vivo targeted vaccine delivery. Gene Ther. 2017, 24, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.J.; et al. Nanobody-based CAR T cells that target the tumor microenvironment inhibit the growth of solid tumors in immunocompetent mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 7624–7631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, N.; et al. Anti-multiple myeloma activity of nanobody-based anti-CD38 chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 4577–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajari Taheri, F.; et al. T cell engineered with a novel nanobody-based chimeric antigen receptor against VEGFR2 as a candidate for tumor immunotherapy. IUBMB Life 2019, 71, 1259–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, M.; et al. Construction of a chimeric antigen receptor bearing a nanobody against prostate-specific membrane antigen in prostate cancer. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 10787–10795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, M.; et al. Engineered Jurkat cells for targeting prostate-specific membrane antigen on prostate cancer cells by nanobody-based chimeric antigen receptor. Iran Biomed J. 2020, 24, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Munter, S.; et al. Nanobody-based dual-specific CARs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.J.; et al. Improved anti-tumor efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor T cells that secrete single-domain antibody fragments. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, canimm.0734.2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougan, M.; et al. Targeting cytokine therapy to the pancreatic tumor microenvironment using PD-L1–specific VHHs. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018, 6, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian-Rizi, T.; et al. Generation and characterization of a functional nanobody against inflammatory chemokine CXCL10, as a novel strategy for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2019, 18, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; et al. Remodeling of the tumor microenvironment by a chemokine/anti-PD-L1 nanobody fusion protein. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 2838–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhoff, A.M.; et al. Nanobody-enhanced targeting of AAV gene therapy vectors. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2019, 15, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahani, R.; et al. Sindbis virus-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors carrying VEGFR2-specific nanobody for potential transductional targeting of tumor vasculature. Mol. Biotechnol. 2016, 58, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoae-Hassani, A.; et al. Recombinant λ bacteriophage displaying nanobody towards third domain of HER-2 epitope inhibits proliferation of breast carcinoma SKBR-3 cell line. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2013, 61, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; et al. BiHC, a T-cell–engaging bispecific recombinant antibody, has potent cytotoxic activity against HER2 tumor cells. Transl. Oncol. 2017, 10, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; et al. A novel bispecific antibody, S-Fab, induces potent cancer cell killing. J. Immunother. 2015, 38, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harwood, S.L.; et al. ATTACK, a novel bispecific T cell-recruiting antibody with trivalent EGFR binding and monovalent CD3 binding for cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2018, 7, e1377874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Linden, R.H.J.; et al. Comparison of physical chemical properties of llama VHH antibody fragments and mouse monoclonal antibodies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1431, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Duong Van Hoa, F. Peptidisc-assisted hydrophobic clustering toward the production of multimeric and multispecific nanobody proteins. Biochemistry 2025, 64, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.; Leong, K.W. Discovery of nanobodies: A comprehensive review of their applications and potential over the past five years. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, K.P.; et al. Unexpected hepatotoxicity in a phase I study of TAS266, a novel tetravalent agonistic nanobody® targeting the DR5 receptor. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2015, 75, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, S.; et al. A novel nanobody-based target module for retargeting T lymphocytes to EGFR-expressing cancer cells via the modular UniCAR platform. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1287246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, R.C.G.; et al. A bispecific nanobody approach to leverage the potent and widely applicable tumor cytolytic capacity of Vγ9Vδ2-T cells. Oncoimmunology 2017, 7, e1375641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; et al. Anti-EGFR-iRGD recombinant protein conjugated silk fibroin nanoparticles for enhanced tumor targeting and antitumor efficiency. Onco Targets Ther. 2016, 9, 3153–3162. [Google Scholar]

- Van De Water, J.A.J.M.; et al. Therapeutic stem cells expressing variants of EGFR-specific nanobodies have antitumor effects. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16642–16647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karges, J.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of an epidermal growth factor receptor-selective RuII polypyridyl–nanobody conjugate as a photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy. ChemBioChem 2019, 21, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; et al. DR30303, a SMART-VHHBody powered anti-CLDN18.2 VHH-Fc with enhanced ADCC activity for the treatment of gastric and pancreatic cancers. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; et al. Phase I study of the VEGF/Ang-2 inhibitor BI 836880 alone or combined with the anti-programmed cell death protein-1 antibody ezabenlimab in Japanese patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2023, 91, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, T.; et al. Phase I study of envafolimab (KN035), a novel subcutaneous single-domain anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody, in Japanese patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest. New Drugs 2022, 40, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; et al. Subcutaneous envafolimab monotherapy in patients with advanced defective mismatch repair/microsatellite instability-high solid tumors. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, K.P.; et al. First-in-human phase I study of envafolimab, a novel subcutaneous single-domain anti-PD-L1 antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Oncologist 2021, 26, e1514–e1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Huyvetter, M.; et al. Phase I trial of ¹³¹I-GMIB-Anti-HER2-VHH1, a new promising candidate for HER2-targeted radionuclide therapy in breast cancer patients. J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 62, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlau, R.; et al. P2.06-006 Phase I/II dose escalation study of L-DOS47 as a monotherapy in non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer patients. J. Thoracic Oncol. 2017, 12, S1071–S1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piha-Paul, S.; et al. A phase I, open-label, dose-escalation study of L-DOS47 in combination with pemetrexed plus carboplatin in patients with stage IV recurrent or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2022, 3, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kater, A.P.; et al. Lava-051, a novel bispecific gamma-delta T-cell engager (Gammabody), in relapsed/refractory MM and CLL: Pharmacodynamic and early clinical data. Blood 2022, 140, 4608–4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, N.; et al. Early dose escalation of LAVA-1207, a novel bispecific gamma-delta T-cell engager (Gammabody), in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). American Society of Clinical Oncology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.; et al. Updated results from CARTITUDE-1: Phase Ib/II study of ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy, in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood 2021, 138, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdeja, J.G.; et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): A phase Ib/II open-label study. Lancet 2021, 398, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.H.; et al. Four-year follow-up of LCAR-B38M in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: A phase I, single-arm, open-label, multicenter study in China (LEGEND-2). J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Donk, N.; et al. B07: Safety and efficacy of ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy directed against B-cell maturation antigen in patients with multiple myeloma and early relapse after initial therapy: CARTITUDE-2 results. HemaSphere 2022, 6, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einsele, H.; et al. P08: CARTITUDE-2 UPDATE: Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen–directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, in lenalidomide-refractory patients with progressive multiple myeloma after 1–3 prior lines of therapy. HemaSphere 2022, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.C.; et al. Efficacy and safety of ciltacabtagene autoleucel (ciltacel), a B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, in lenalidomide-refractory patients with progressive multiple myeloma after 1–3 prior lines of therapy: Updated results from CARTITUDE-2. Blood 2021, 138, 3866. [Google Scholar]

- Agha, M.E.; et al. S185: CARTITUDE-2 cohort B: Updated clinical data and biological correlative analyses of ciltacabtagene autoleucel in patients with multiple myeloma and early relapse after initial therapy. HemaSphere 2022, 6, 86–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussel, U.Z. Quantification of 68-GaNOTA-Anti-HER2 VHH1 Uptake in Metastasis of Breast Carcinoma Patients and Assessment of Repeatability (VUBAR)—Pilot Study. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03924466 (2024). 0392. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03924466?a=3.

- Alexion Pharmaceuticals, I. A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Parallel, Multicenter Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of ALXN1720 in Adults With Generalized Myasthenia Gravis. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05556096.

| Nanobodies vs. Conventional Antibody | ||

| Structural simplicity | Single-domain structure | Heterotetrameric structure |

| Size | ~15 kDa | ~150 kDa |

| CDR | 3 CDRs (Longer CDR1 and CD3) | 3 CDRs |

| Stability | High. Generally, they are functional at high temperatures and different pH levels | Less stable under extreme temperatures and pH conditions |

| Solubility | High. They are rich in hydrophilic regions, preventing aggregation | Solubility is more variable and lower in some cases due to hydrophobic regions. Such regions increase the risk of aggregation |

| Affinity | High | High |

| Immunogenicity | Low | Higher than nanobodies, can induce immune responses |

| Antigenic Diversity | Both non-planar and planar epitopes | Mainly planar epitopes |

| Efficient Tissue Penetration | High | Low, due to larger size |

| Cost of Production | Low | High |

| Examples | Reference | |

| Targeting Modules (UniCAR) | Nanobody-based targeting modules that effectively retarget UniCAR T cells to induce EGFR+ tumor lysis. | [59] |

| γδ T Cell Activator | Nanobody as part of BiTE, targeting the EGFR and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells receptor stimulated T-cell mediated cytotoxicity against EGFR+ tumor cells in vivo. | [60] |

| Tumor Penetrating Peptides | Nanobodies conjugated to penetrating peptides to improve specificity and penetration. Anti-EGFR nanobodies fused to these peptides have demonstrated antitumor activity in vivo | [61] |

| Nanobody-Secreting Stem Cells | Therapeutic stem cells that secrete either anti-EGFR nanobodies conjugated to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis | [62] |

| Nanobodies in Photodynamic Therapy | Nanobody-photosensitizer conjugates demonstrated targeted phototoxicity in vitro and in vivo. Anti-EGFR nanobodies conjugated to a novel RuII polypyridyl complex reported EGFR-specific targeting | [63] |

| Clinical Trial ID/Phase | Title | Results | Reference |

| NCT05639153/ Phase I | A Trial to Evaluate Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics and Preliminary Efficacy of DR30303 in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors | Completion date-30/04/2024 | [64] |

| NCT03972150/ Phase I | A Study to Find the Best Dose of BI 836880 Alone and in Combination with BI 754091 in Japanese Patients with Different Types of Advanced Cancer | The maximum tolerated dose was not reached. BI 836880 alone and in combination with ezabenlimab had a manageable safety profile with preliminary clinical activity in Japanese patients with advanced solid tumors | [65] |

| NCT03248843/ Phase I | A Study of PD-L1 Antibody KN035 in Japanese Subjects with Locally Advanced or Metastatic Solid Tumors | Well-tolerated with efficacy. Pharmacokinetics data and preliminary anti-tumor response support dose regimens | [66] |

| NCT03667170/ Phase I | KN035 in Subjects with Advanced Solid Tumors | Completion date-15/12/2025 | [67] |

| NCT02827968/ Phase I | Phase 1 Study of Anti-PD-L1 Monoclonal Antibody KN035 to Treat Locally Advanced or Metastatic Solid Tumors | Favorable safety and pharmacokinetic profile, with promising preliminary antitumor activity in patients with advanced solid tumors | [68] |

| NCT02683083/ Phase I | [131I]-SGMIB Anti-HER2 VHH1 in Patients with HER2+ Breast Cancer | No drug-related adverse events with 131I-GMIB-anti-HER2-VHH1, primarily eliminated through the kidneys, stability in circulation, exhibited specific uptake in metastatic lesions in advanced breast cancer patients | [69] |

| NCT02340208/ Phase I/II | A Phase I/II Open-Label, Non-Randomized Dose Escalation Study of Immunoconjugate L-DOS47 | One dose-limiting toxicity (spinal pain) observed, no complete or partial responses were seen, 32 patients achieved stable disease after two treatment cycles, one patient in cohort 9 remained on treatment for 10 cycles without disease progression | [70] |

| NCT02309892/ Phase I | A Phase I, Open Label, Dose Escalation Study of Immunoconjugate L-DOS47 in Combination with Pemetrexed/Carboplatin in Patients with Stage IV (TNM M1a and M1b) Recurrent or Metastatic NSCLC Lung Cancer | L-DOS47 combined with standard pemetrexed, and carboplatin chemotherapy is well tolerated in patients with recurrent or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC | [71] |

| NCT04887259/ Phase I/IIa | Trial of LAVA-051 in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory CLL, MM, or AML | Completion – 30/12/2024 | [72] |

| NCT05369000/ Phase I/IIa | Trial of LAVA-1207 in Patients with Therapy Refractory Metastatic Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer | Completion—30/03/2024 | [73] |

| NCT03548207/ Phase Ib/2 | A Phase 1b-2, Open-Label Study of JNJ-68284528, A Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell (CAR-T) Therapy Directed Against BCMA in Subjects with Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma | With a median follow-up of 18 months, results show significant, long-lasting responses in heavily treated multiple myeloma patients, the treatment maintained a manageable safety profile without any new safety concerns | [74,75] |

| NCT03090659/ Phase 1/2 | A Clinical Study of Legend Biotech BCMA-chimeric Antigen Receptor Technology in Treating Relapsed/Refractory (R/R) Multiple Myeloma Patients | Completion—31/12/2023 | [76] |

| NCT04133636/ Phase 2 | A Phase 2, Multicohort Open-Label Study of JNJ-68284528, A Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell (CAR-T) Therapy Directed Against BCMA in Subjects with Multiple Myeloma | Completion—13/11/2028. Interim results—responses with manageable safety, responses in pts with ineffective or insufficient response to autologous stem cell transplantation | [77,78] |

| NCT03924466/ Phase II | Quantification of 68-GaNOTA-Anti-HER2 VHH1 Uptake in Metastasis of Breast Carcinoma Patients and Assessment of Repeatability (VUBAR) – Pilot Study | Completion-31/12/2024 | [79] |

| NCT05556096/ Phase III | A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Parallel, Multicenter Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of ALXN1720 in Adults with Generalized Myasthenia Gravis | Completion-07/07/2027 | [80] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).