Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Collection and RVA Detection

2.3. Genotyping of RVA Strains

2.4. Sequencing of RVA Strains

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

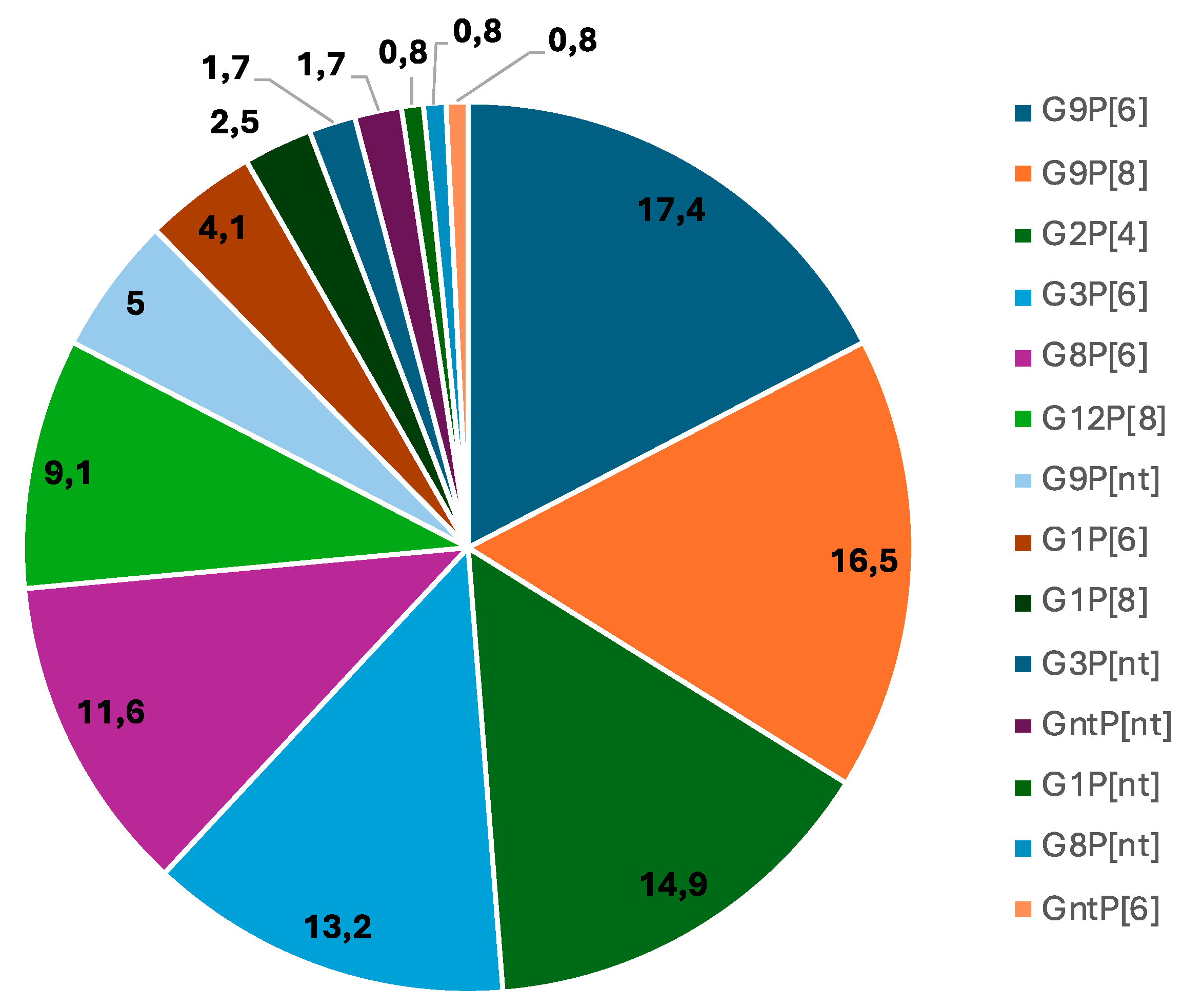

3.1. High Diversity of RVA Strains Detected in Children Hospitalized with AGE in Luanda Province Public Hospitals

3.2. Genotype Diversity, Age and Severity of Disease

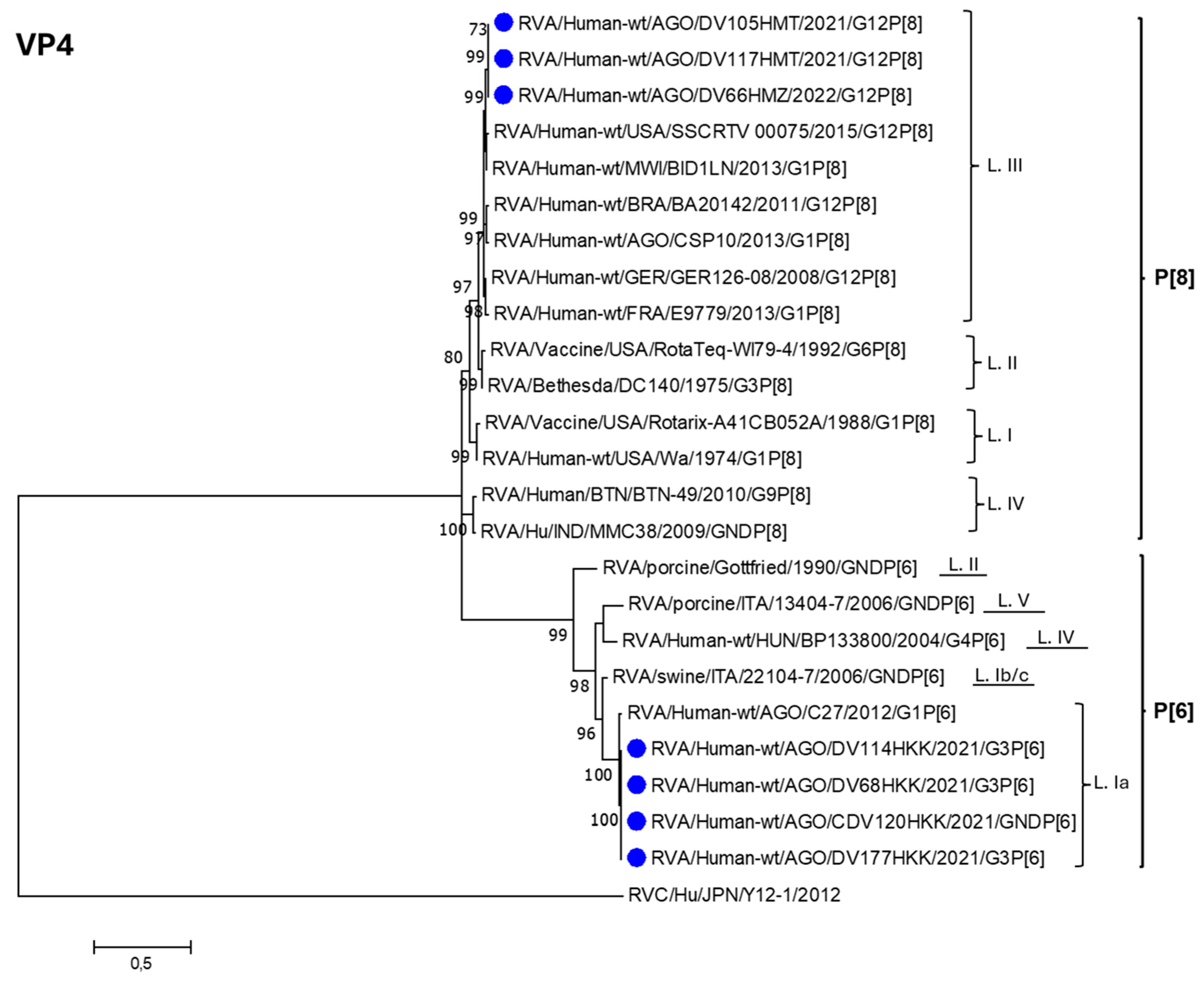

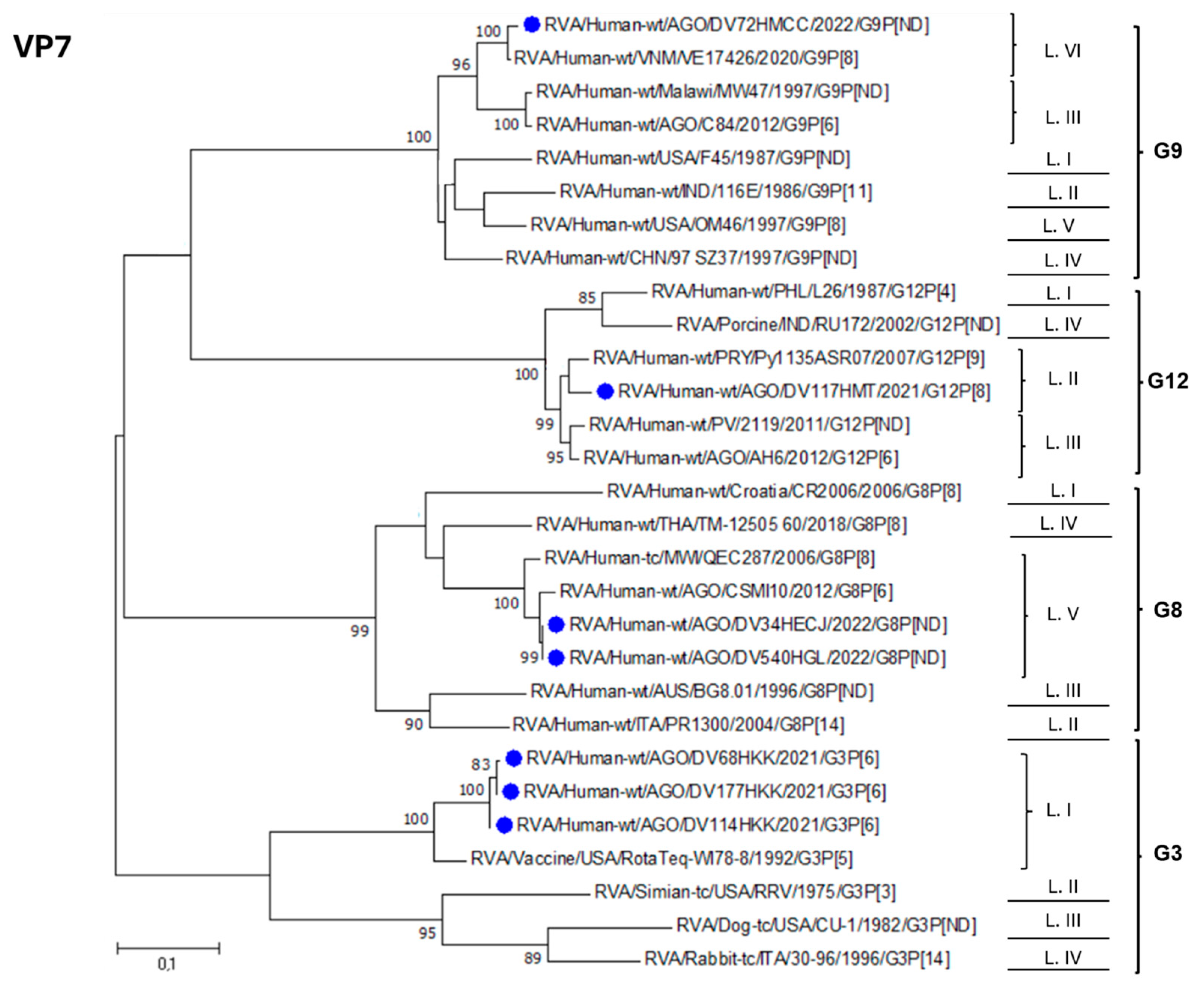

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis of RVA Strains Identified in Luanda Province Post Vaccine Introduction

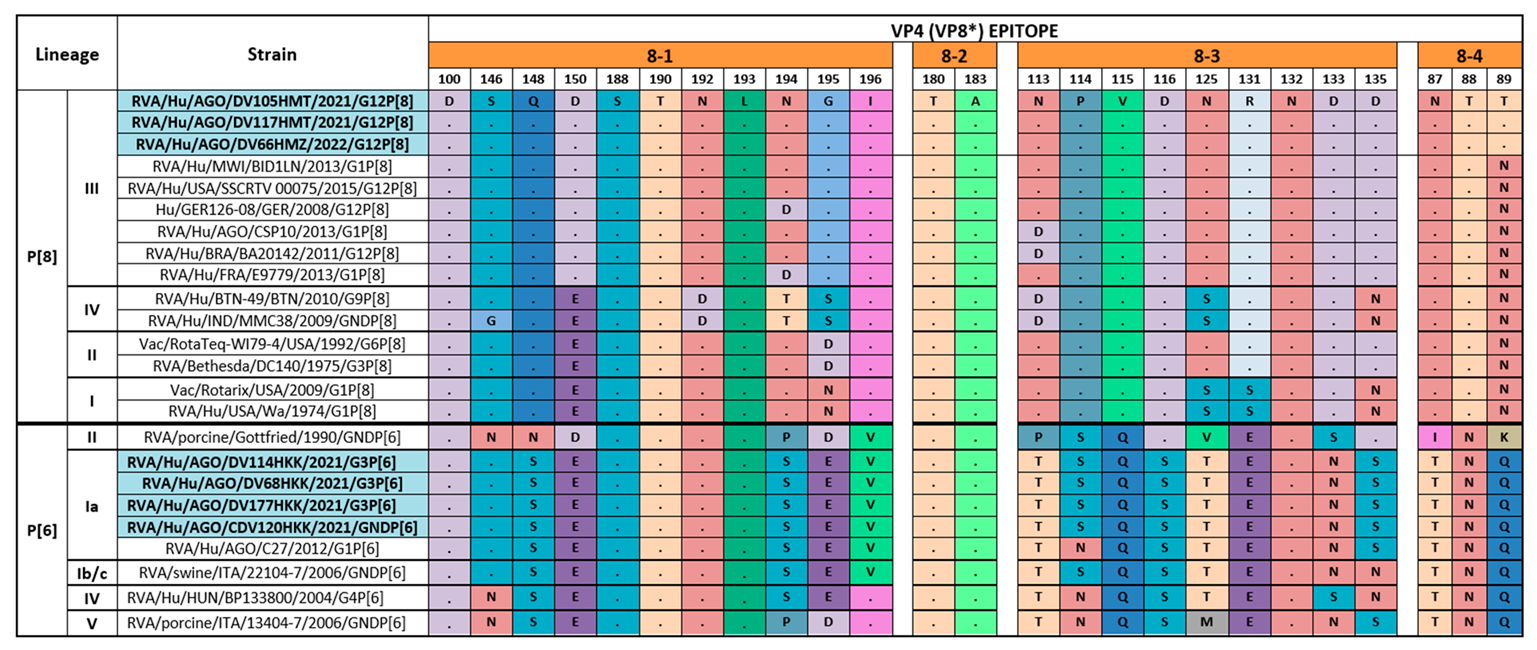

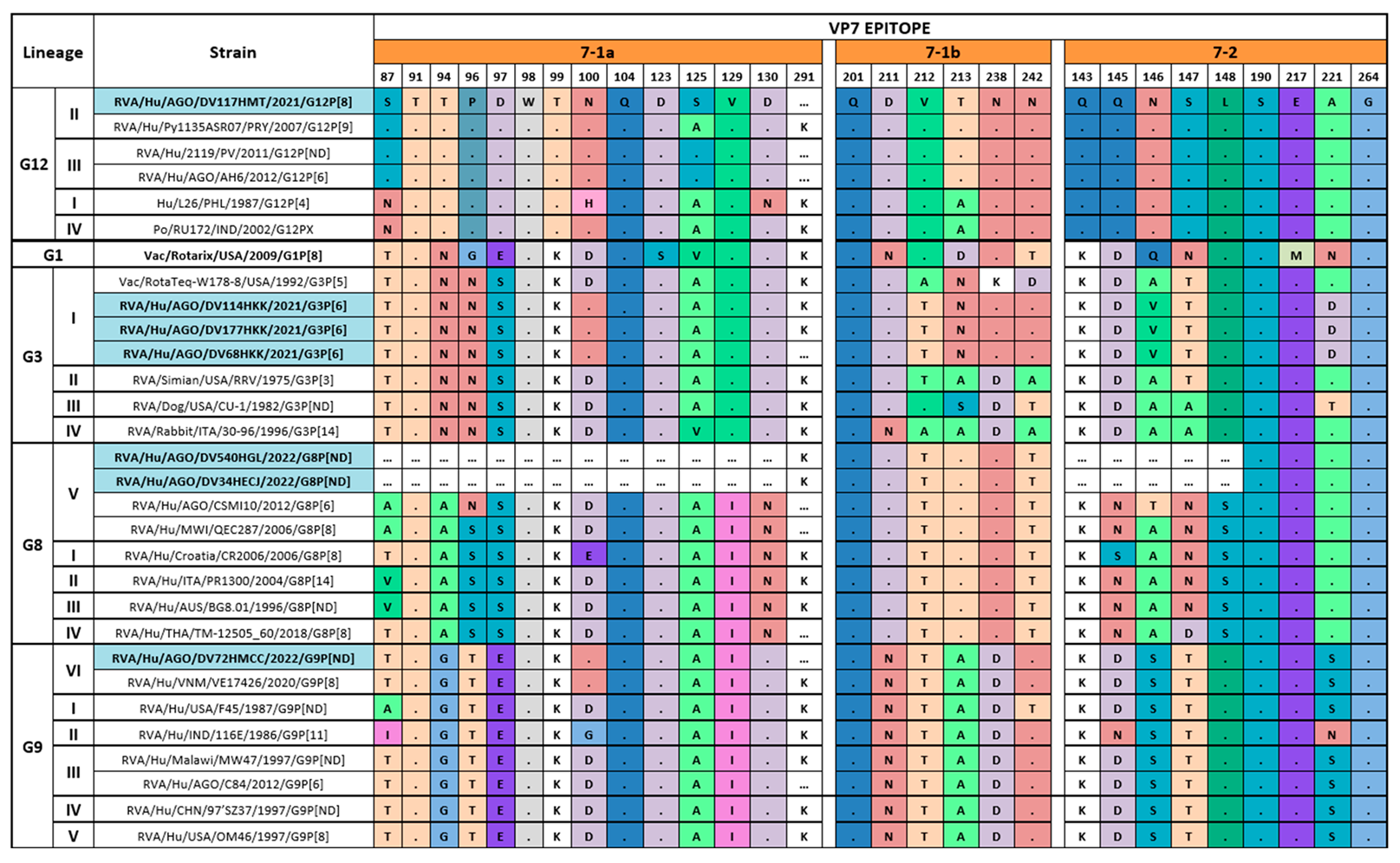

3.4. Comparison of the Deduced Antigenic Region of VP4 (VP8*) and VP7

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crawford, S. E.; Ramani, S.; Tate, J. E.; Parashar, U. D.; Svensson, L.; Hagbom, M.; Franco, M. A.; Greenberg, H. B.; O'Ryan, M.; Kang, G.; Desselberger, U.; Estes, M. K., Rotavirus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017, 3, 17083.

- Jampanil, N.; Kumthip, K.; Maneekarn, N.; Khamrin, P., Genetic Diversity of Rotaviruses Circulating in Pediatric Patients and Domestic Animals in Thailand. Trop Med Infect Dis 2023, 8, (7).

- Troeger, C.; Khalil, I. A.; Rao, P. C.; Cao, S.; Blacker, B. F.; Ahmed, T.; Armah, G.; Bines, J. E.; Brewer, T. G.; Colombara, D. V.; Kang, G.; Kirkpatrick, B. D.; Kirkwood, C. D.; Mwenda, J. M.; Parashar, U. D.; Petri, W. A., Jr.; Riddle, M. S.; Steele, A. D.; Thompson, R. L.; Walson, J. L.; Sanders, J. W.; Mokdad, A. H.; Murray, C. J. L.; Hay, S. I.; Reiner, R. C., Jr., Rotavirus Vaccination and the Global Burden of Rotavirus Diarrhea Among Children Younger Than 5 Years. JAMA Pediatr 2018, 172, (10), 958-965.

- Tate, J. E.; Burton, A. H.; Boschi-Pinto, C.; Parashar, U. D., Global, Regional, and National Estimates of Rotavirus Mortality in Children <5 Years of Age, 2000–2013. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, (suppl 2), S96‐S105.

- Sadiq, A.; Khan, J., Rotavirus in developing countries: molecular diversity, epidemiological insights, and strategies for effective vaccination. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1297269.

- Burnett, E.; Parashar, U. D.; Tate, J. E., Real-world effectiveness of rotavirus vaccines, 2006-19: a literature review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2020, 8, (9), e1195-e1202.

- Desselberger, U., Differences of Rotavirus Vaccine Effectiveness by Country: Likely Causes and Contributing Factors. Pathogens 2017, 6, (4).

- Parker, E. P.; Ramani, S.; Lopman, B. A.; Church, J. A.; Iturriza-Gomara, M.; Prendergast, A. J.; Grassly, N. C., Causes of impaired oral vaccine efficacy in developing countries. Future Microbiol. 2018, 13, (1), 97-118.

- Desselberger, U., Rotaviruses. Virus Res. 2014, 190, 75-96.

- Matthijnssens, J.; Otto, P. H.; Ciarlet, M.; Desselberger, U.; Van Ranst, M.; Johne, R., VP6-sequence-based cutoff values as a criterion for rotavirus species demarcation. Arch. Virol. 2012, 157, (6), 1177-82.

- Matthijnssens, J.; Ciarlet, M.; McDonald, S. M.; Attoui, H.; Banyai, K.; Brister, J. R.; Buesa, J.; Esona, M. D.; Estes, M. K.; Gentsch, J. R.; Iturriza-Gomara, M.; Johne, R.; Kirkwood, C. D.; Martella, V.; Mertens, P. P.; Nakagomi, O.; Parreno, V.; Rahman, M.; Ruggeri, F. M.; Saif, L. J.; Santos, N.; Steyer, A.; Taniguchi, K.; Patton, J. T.; Desselberger, U.; Van Ranst, M., Uniformity of rotavirus strain nomenclature proposed by the Rotavirus Classification Working Group (RCWG). Arch. Virol. 2011, 156, (8), 1397-413.

- RCWG, https://rega.kuleuven.be/cev/viralmetagenomics/virus-classification/rcwg. 2023.

- Sadiq, A.; Bostan, N.; Jadoon, K.; Aziz, A., Effect of rotavirus genetic diversity on vaccine impact. Rev. Med. Virol. 2022, 32, (1), e2259.

- Doro, R.; Farkas, S. L.; Martella, V.; Banyai, K., Zoonotic transmission of rotavirus: surveillance and control. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2015, 13, (11), 1337-50.

- Bányai, K.; Pitzer, V. E., Chapter 2.10 - Molecular Epidemiology and Evolution of Rotaviruses. In Viral Gastroenteritis, Svensson, L.; Desselberger, U.; Greenberg, H. B.; Estes, M. K., Eds. Academic Press: Boston, 2016; pp 279-299.

- Bányai, K.; Gentsch, J., Special issue on ‘Genetic diversity and evolution of rotavirus strains: Possible impact of global immunization programs’. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014, 28, 375-376.

- Vita, D.; Lemos, M.; Neto, Z.; Evans, M.; Francisco, N. M.; Fortes, F.; Fernandes, E.; Cunha, C.; Istrate, C., High Detection Rate of Rotavirus Infection Among Children Admitted with Acute Gastroenteritis to Six Public Hospitals in Luanda Province After the Introduction of Rotarix((R)) Vaccine: A Cross-Sectional Study. Viruses 2024, 16, (12).

- Gentsch, J. R.; Glass, R. I.; Woods, P.; Gouvea, V.; Gorziglia, M.; Flores, J.; Das, B. K.; Bhan, M. K., Identification of group A rotavirus gene 4 types by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992, 30, (6), 1365-73.

- Iturriza-Gomara, M.; Kang, G.; Gray, J., Rotavirus genotyping: keeping up with an evolving population of human rotaviruses. J. Clin. Virol. 2004, 31, (4), 259-65.

- Hall, T. A., BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignement editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. 1999, 41, 95-98.

- Larkin, M. A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N. P.; Chenna, R.; McGettigan, P. A.; McWilliam, H.; Valentin, F.; Wallace, I. M.; Wilm, A.; Lopez, R.; Thompson, J. D.; Gibson, T. J.; Higgins, D. G., Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, (21), 2947-2948.

- Nicholas, K. B.; Nicholas, H. B.; Deerfield, D. W. In GeneDoc: Analysis and visualization of genetic variation, 1997; 1997.

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K., MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, (7), 1870-4.

- Felsenstein, J., Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum likelihood approach. J. Mol. Evol. 1981, 17, (6), 368-76.

- Aoki, S. T.; Settembre, E. C.; Trask, S. D.; Greenberg, H. B.; Harrison, S. C.; Dormitzer, P. R., Structure of Rotavirus Outer-Layer Protein VP7 Bound with a Neutralizing Fab. Science 2009, 324, (5933), 1444-1447.

- Dormitzer, P. R.; Nason, E. B.; Prasad, B. V.; Harrison, S. C., Structural rearrangements in the membrane penetration protein of a non-enveloped virus. Nature 2004, 430, (7003), 1053-8.

- Dormitzer, P. R.; Sun, Z. Y.; Wagner, G.; Harrison, S. C., The rhesus rotavirus VP4 sialic acid binding domain has a galectin fold with a novel carbohydrate binding site. EMBO J. 2002, 21, (5), 885-97.

- Zeller, M.; Patton, J. T.; Heylen, E.; Coster, S. D.; Ciarlet, M.; Ranst, M. V.; Matthijnssens, J., Genetic Analyses Reveal Differences in the VP7 and VP4 Antigenic Epitopes between Human Rotaviruses Circulating in Belgium and Rotaviruses in Rotarix and RotaTeq. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, (3), 966-976.

- Esteves, A.; Nordgren, J.; Pereira, J.; Fortes, F.; Dimbu, R.; Saraiva, N.; Mendes, C.; Istrate, C., Molecular epidemiology of rotavirus in four provinces of Angola before vaccine introduction. J. Med. Virol. 2016, 88, (9), 1511-1520.

- Omatola, C. A.; Ogunsakin, R. E.; Olaniran, A. O., Prevalence, Pattern and Genetic Diversity of Rotaviruses among Children under 5 Years of Age with Acute Gastroenteritis in South Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Viruses 2021, 13, (10).

- Bawa, F. K.; Mutocheluh, M.; Dassah, S. D.; Ansah, P.; Oduro, A. R., Genetic diversity of rotavirus infection among young children with diarrhoea in the Kassena-Nankana Districts of Northern Ghana: a seasonal cross-sectional survey. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2023, 44, 148.

- Munlela, B.; Joao, E. D.; Strydom, A.; Bauhofer, A. F. L.; Chissaque, A.; Chilaule, J. J.; Mauricio, I. L.; Donato, C. M.; O'Neill, H. G.; de Deus, N., Whole-Genome Characterization of Rotavirus G9P[6] and G9P[4] Strains That Emerged after Rotavirus Vaccine Introduction in Mozambique. Viruses 2024, 16, (7).

- Gasparinho, C.; Piedade, J.; Mirante, M. C.; Mendes, C.; Mayer, C.; Vaz Nery, S.; Brito, M.; Istrate, C., Characterization of rotavirus infection in children with acute gastroenteritis in Bengo province, Northwestern Angola, prior to vaccine introduction. PLoS One 2017, 12, (4), e0176046.

- Bonura, F.; Mangiaracina, L.; Filizzolo, C.; Bonura, C.; Martella, V.; Ciarlet, M.; Giammanco, G. M.; De Grazia, S., Impact of Vaccination on Rotavirus Genotype Diversity: A Nearly Two-Decade-Long Epidemiological Study before and after Rotavirus Vaccine Introduction in Sicily, Italy. In Pathogens, 2022; Vol. 11.

- Joao, E. D.; Munlela, B.; Chissaque, A.; Chilaule, J.; Langa, J.; Augusto, O.; Boene, S. S.; Anapakala, E.; Sambo, J.; Guimaraes, E.; Bero, D.; Cassocera, M.; Cossa-Moiane, I.; Mwenda, J. M.; Mauricio, I.; O'Neill, H. G.; de Deus, N., Molecular Epidemiology of Rotavirus A Strains Pre- and Post-Vaccine (Rotarix((R))) Introduction in Mozambique, 2012-2019: Emergence of Genotypes G3P[4] and G3P[8]. Pathogens 2020, 9, (9).

- Mhango, C.; Banda, A.; Chinyama, E.; Mandolo, J. J.; Kumwenda, O.; Malamba-Banda, C.; Barnes, K. G.; Kumwenda, B.; Jambo, K. C.; Donato, C. M.; Esona, M. D.; Mwangi, P. N.; Steele, A. D.; Iturriza-Gomara, M.; Cunliffe, N. A.; Ndze, V. N.; Kamng'ona, A. W.; Dennis, F. E.; Nyaga, M. M.; Chaguza, C.; Jere, K. C., Comparative whole genome analysis reveals re-emergence of human Wa-like and DS-1-like G3 rotaviruses after Rotarix vaccine introduction in Malawi. Virus Evol 2023, 9, (1), vead030.

- Seheri, L. M.; Magagula, N. B.; Peenze, I.; Rakau, K.; Ndadza, A.; Mwenda, J. M.; Weldegebriel, G.; Steele, A. D.; Mphahlele, M. J., Rotavirus strain diversity in Eastern and Southern African countries before and after vaccine introduction. Vaccine 2018, 36, (47), 7222-7230.

- Ramachandran, M.; Das, B. K.; Vij, A.; Kumar, R.; Bhambal, S. S.; Kesari, N.; Rawat, H.; Bahl, L.; Thakur, S.; Woods, P. A.; Glass, R. I.; Bhan, M. K.; Gentsch, J. R., Unusual diversity of human rotavirus G and P genotypes in India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996, 34, (2), 436-9.

- Page, N. A.; Seheri, L. M.; Groome, M. J.; Moyes, J.; Walaza, S.; Mphahlele, J.; Kahn, K.; Kapongo, C. N.; Zar, H. J.; Tempia, S.; Cohen, C.; Madhi, S. A., Temporal association of rotavirus vaccination and genotype circulation in South Africa: Observations from 2002 to 2014. Vaccine 2018, 36, (47), 7231-7237.

- Gurgel, R. Q.; Cuevas, L. E.; Vieira, S. C.; Barros, V. C.; Fontes, P. B.; Salustino, E. F.; Nakagomi, O.; Nakagomi, T.; Dove, W.; Cunliffe, N.; Hart, C. A., Predominance of rotavirus P[4]G2 in a vaccinated population, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, (10), 1571-3.

| G -type | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| G1 | 9 | 7.4 |

| G2 | 18 | 14.9 |

| G3 | 18 | 14.9 |

| G8 | 15 | 12.4 |

| G9 | 46 | 38.8 |

| G12 | 11 | 9.1 |

| Gnta | 3 | 2.5 |

| Total | 121 | 100 |

| P -type | N | % |

| P4 | 18 | 14.8 |

| P6 | 57 | 47.1 |

| P8 | 34 | 28.0 |

| Pnt b | 12 | 9.9 |

| Total | 121 | 100 |

| Genotype combination |

Cacuaco n (%) |

Luanda n (%) |

Zango n (%) |

Cajueiros n (%) | Talatona n (%) | K. Kiaxi n (%) |

Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1P[6] | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.9) | 3 (9.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (00.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (4.1) |

| G1P[8] | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (17.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.5) |

| G1Pnt* | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) |

| G2P[4] | 5 (31.2) | 3 (10.3) | 9 (29.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (14.9) |

| G3P[6] | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.9) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (10) | 2 (11.8) | 10 (55.6) | 16 (13.2) |

| G3Pnt* | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.6) | 2 (1.6) |

| G8P[6] | 1 (6.2) | 3 (10.3) | 3 (9.7) | 4 (40.0) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (5.6) | 14 (11.5) |

| G8Pnt* | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) |

| G9P[6] | 3 (18.8) | 10(34.5) | 5 (16.1) | 1 (10) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.6) | 21 (17.3) |

| G9P[8] | 6 (37.5) | 3(10.3) | 7 (22.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (22.0) | 20 (16.5) |

| G9Pnt* | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (30.0) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.6) | 6 (4.9) |

| G12P[8] | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (41.1) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (9.1) |

| *GntP[6] | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) |

| *GntPnt | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) |

| Total | 16 (100) | 29 (100) | 31 (100) | 10 (100) | 17 (100) | 18 (100) | 121 (100) |

| Age group (months) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | 0 – 6 n (%) |

7 - 12 n (%) |

13 – 24 n (%) |

> 24 n (%) |

Total |

| G1P[6] | 3 (3.4) | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (4.1) |

| G1P[8] | 3 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.5) |

| G1PN | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0,0) | 1 (0.8) |

| G2P[4] | 14 (16.1) | 4 (13.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (14.9) |

| G3P[6] | 12 (13.8) | 3 (10.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) | 16 (13.2) |

| G3PN | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) |

| G8P[6] | 11 (12.6) | 3 (10.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (11.5) |

| G8PN | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) |

| G9P[6] | 9 (10.3) | 8 (27.5) | 2 (100) | 2 (66.7) | 21 (17.3) |

| G9P[8] | 14 (16.1) | 6 (20.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (16.5) |

| G9PN | 4 (4.6) | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.9) |

| G12P[8] | 10 (11.5) | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (9.1) |

| *GntP[6] | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) |

| *GntPN | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) |

| Total | 87 (100) | 29 (100) | 2 (100) | 3 (100) | 121 (100) |

| Severity of diarrhea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype |

Mild (<7) n (%) |

Moderate (7-10) n (%) |

Severe (=> 11) n (%) |

Total n (%) |

| G1P[6] | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (4.5) | 5 (4.1) |

| G1P[8] | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (1.8) | 3 (2.5) |

| G1Pnt | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) |

| G2P[4] | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (16.5) | 18 (14.9) |

| G3P[6] | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | 15 (15.6) | 16 (13.2) |

| G3PN | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.8) | 2 (1.6) |

| G8P[6] | 0 (0.0) | 2 (20.0) | 12 (11.0) | 14 (11.5) |

| G8Pnt | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.7) |

| G9P[6] | 2 (100) | 1 (10.0) | 18 (16.5) | 21 (17.3) |

| G9P[8] | 0 (0.0) | 2 (20.0) | 18 (16.5) | 20 (16.5) |

| G9PN | 0 (0.0) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (3.6) | 6 (4.9) |

| G12P[8] | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | 10 (9.2) | 11 (9.1) |

| *GntP[6] | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) |

| *GntPN | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.8) | 2 (1.7) |

| Total | 2 (100) | 10 (100) | 109 (100) | 121 (100) |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).