Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

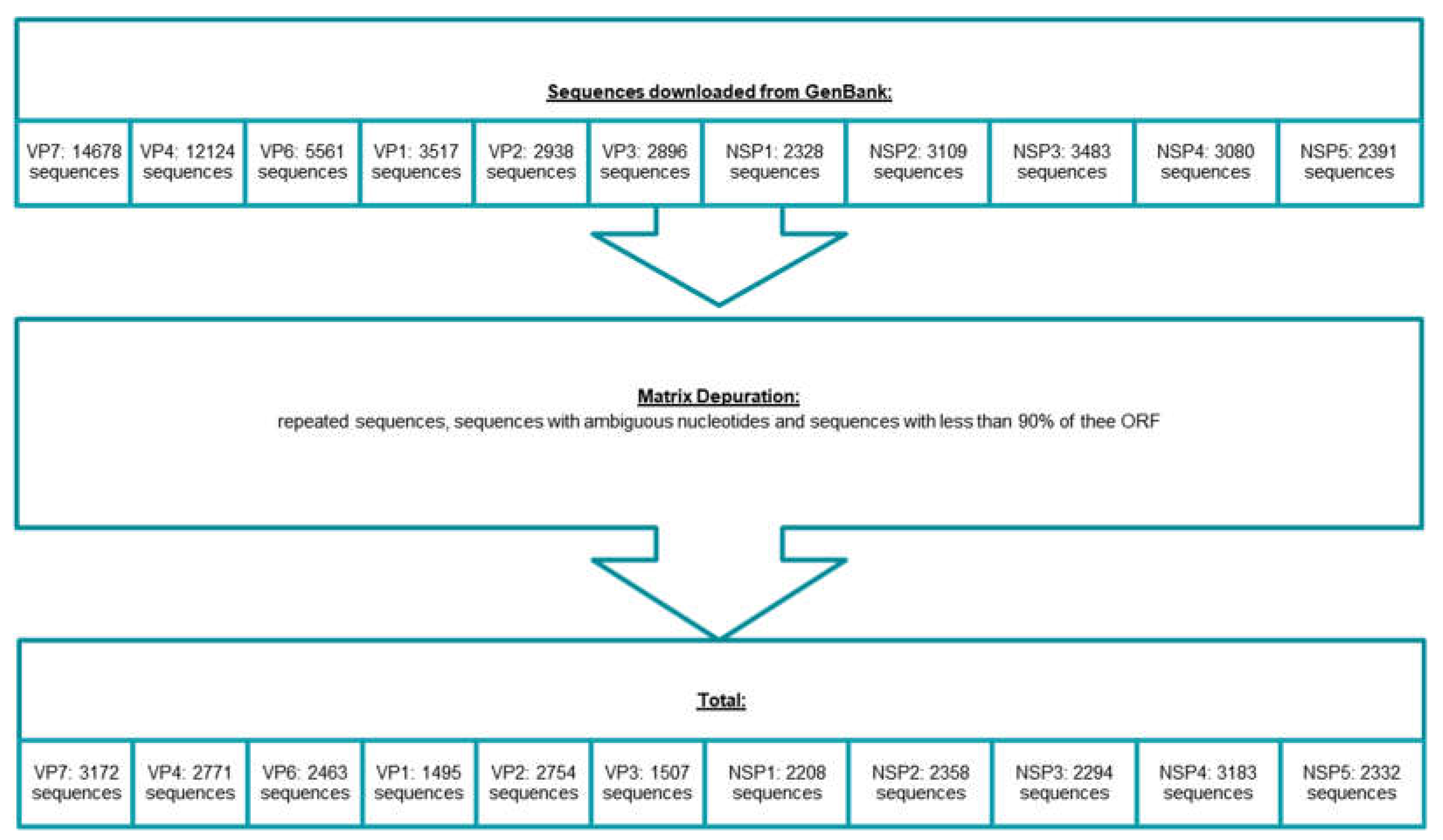

2.1. Matrix Construction and Alignment

2.2. Genetic Variation

2.2.1. Data Quality: Evolution Model, Nucleotide Frequency, Nucleotide Substitution and Phylogenetic Information Estimation

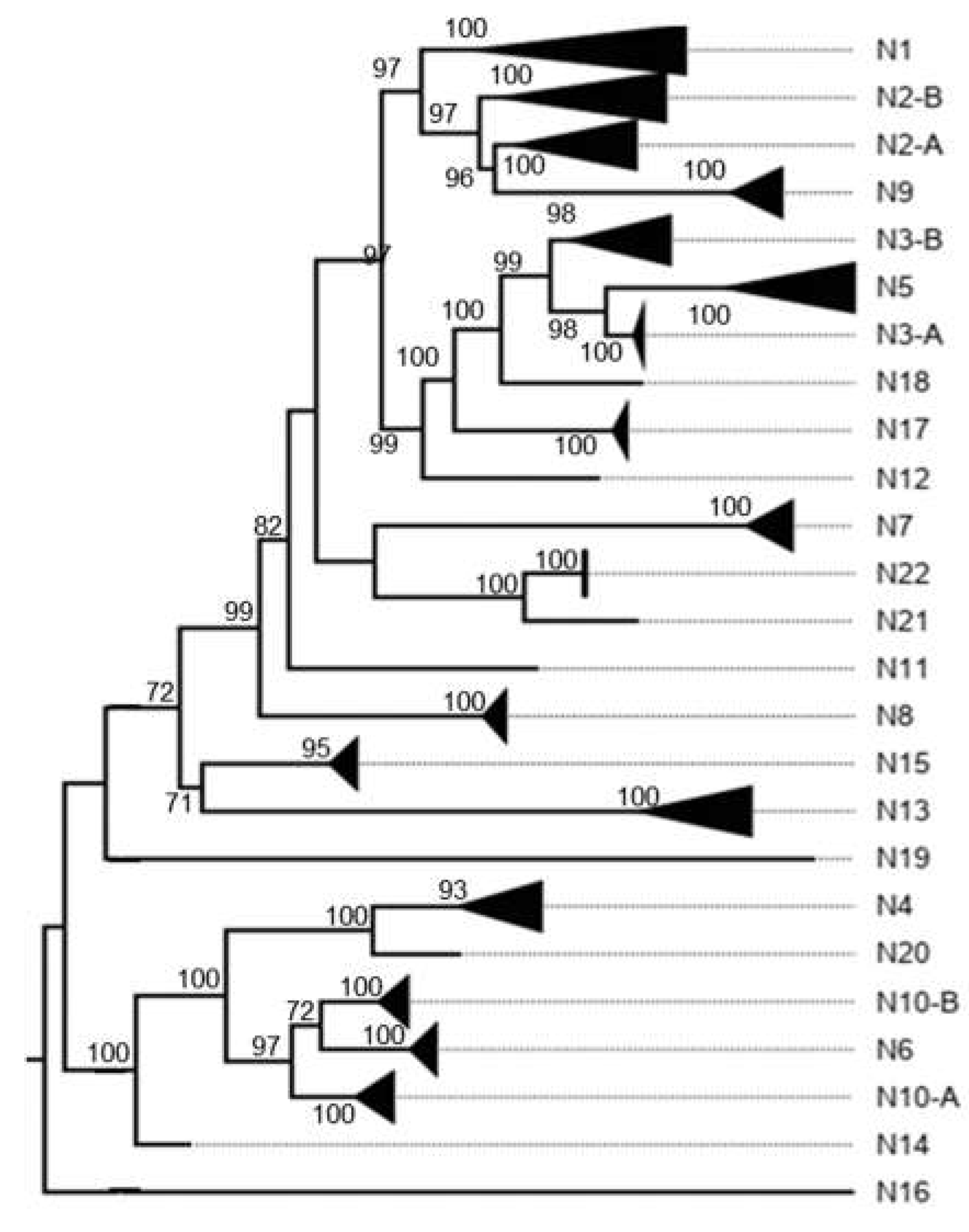

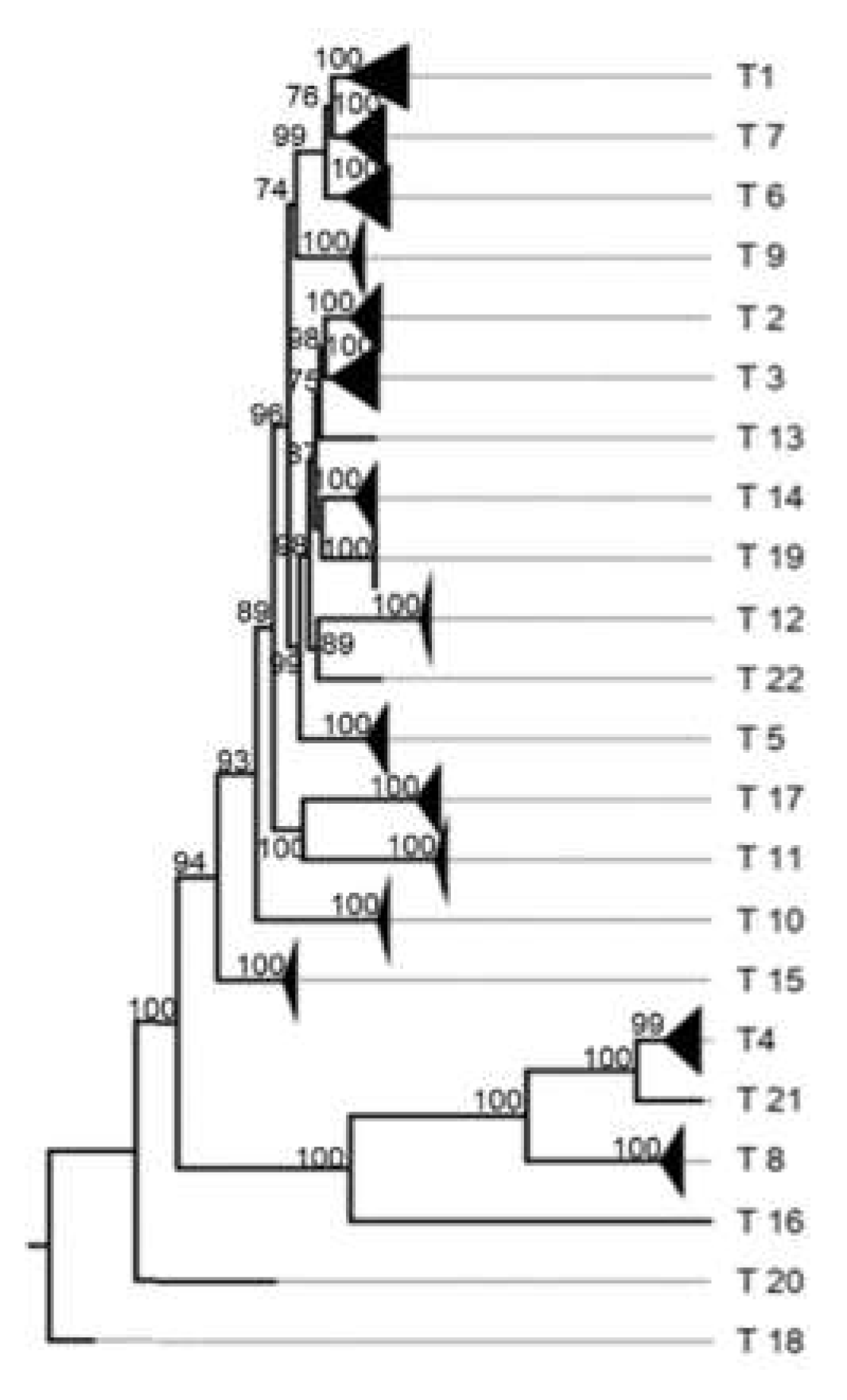

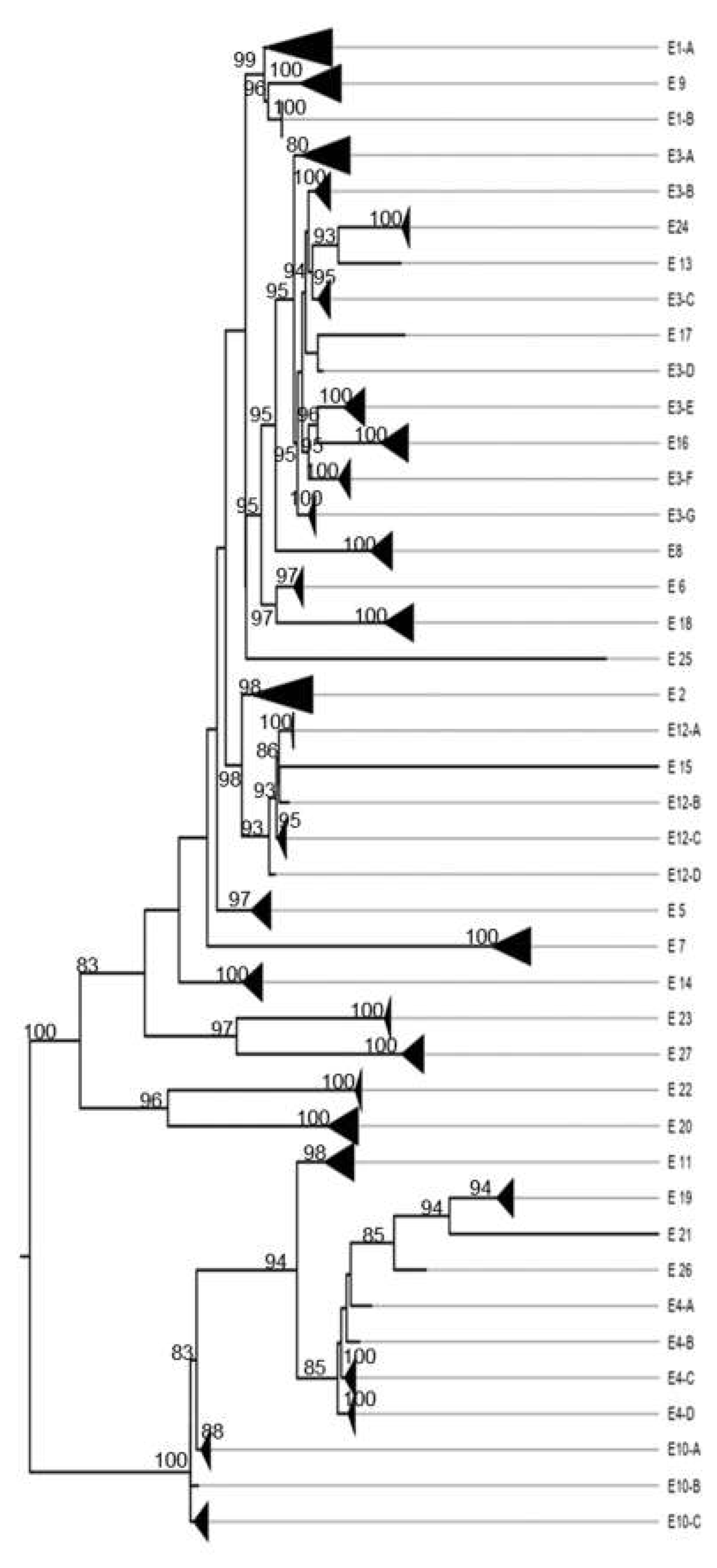

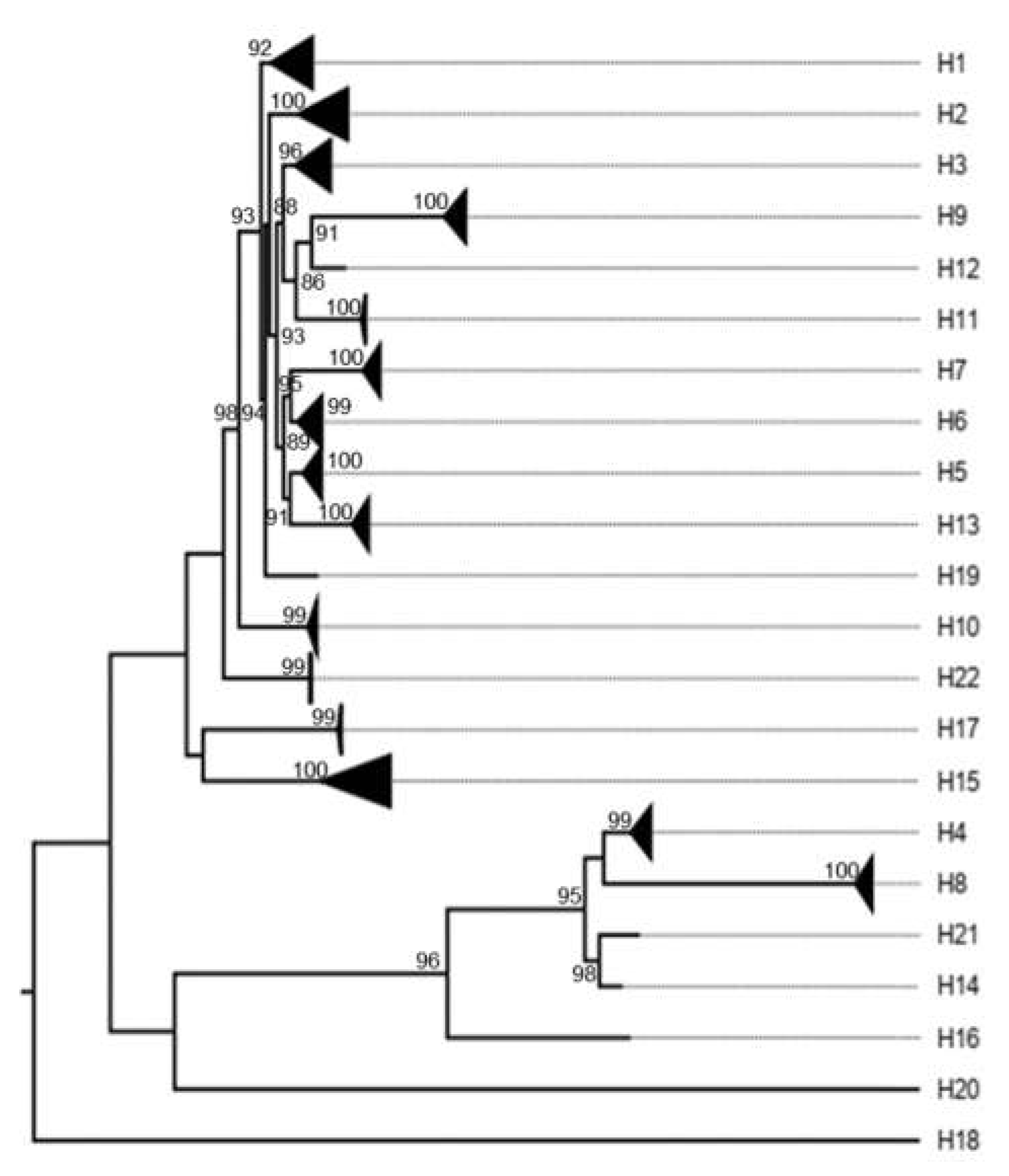

2.2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

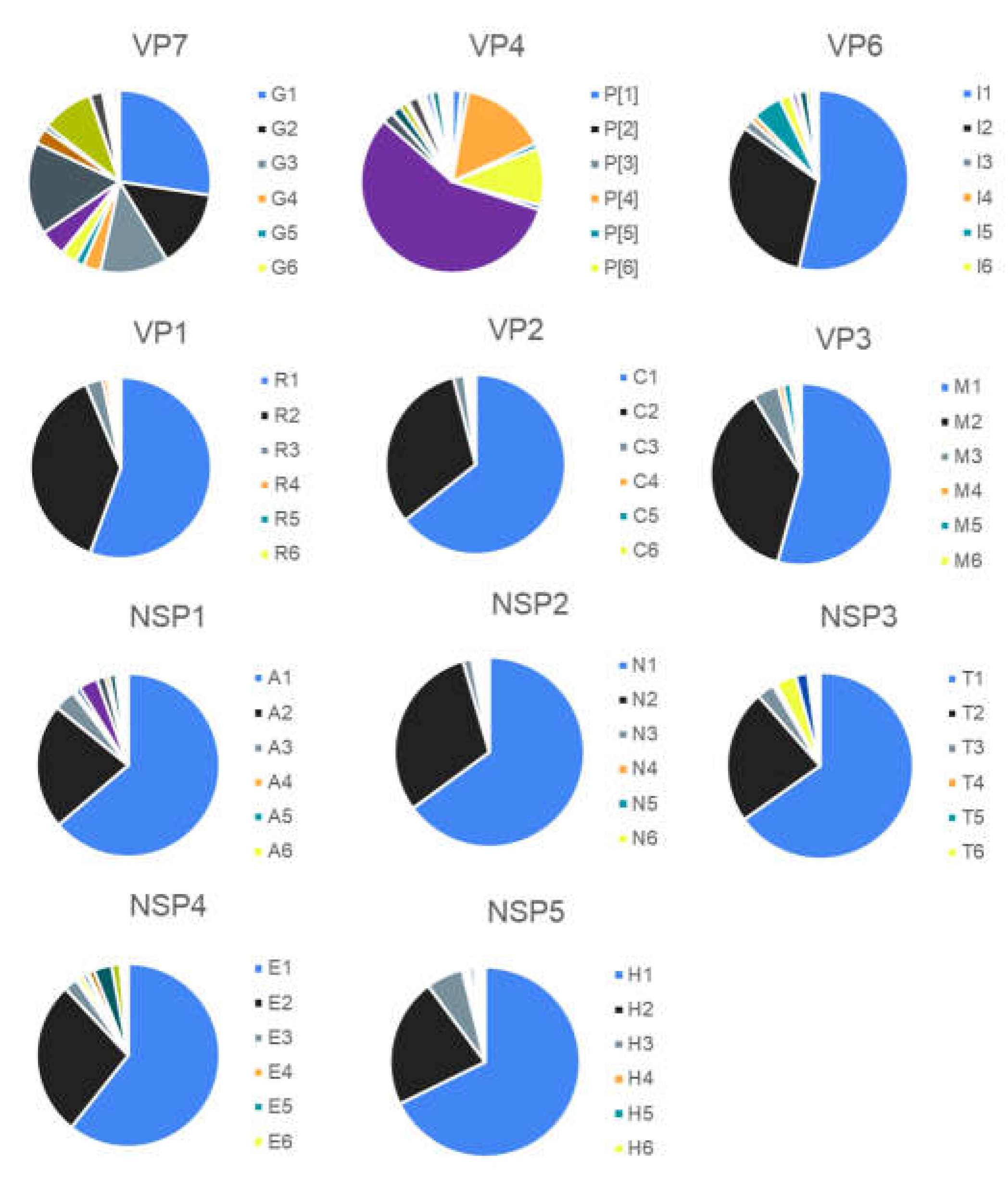

3.1. Classification System

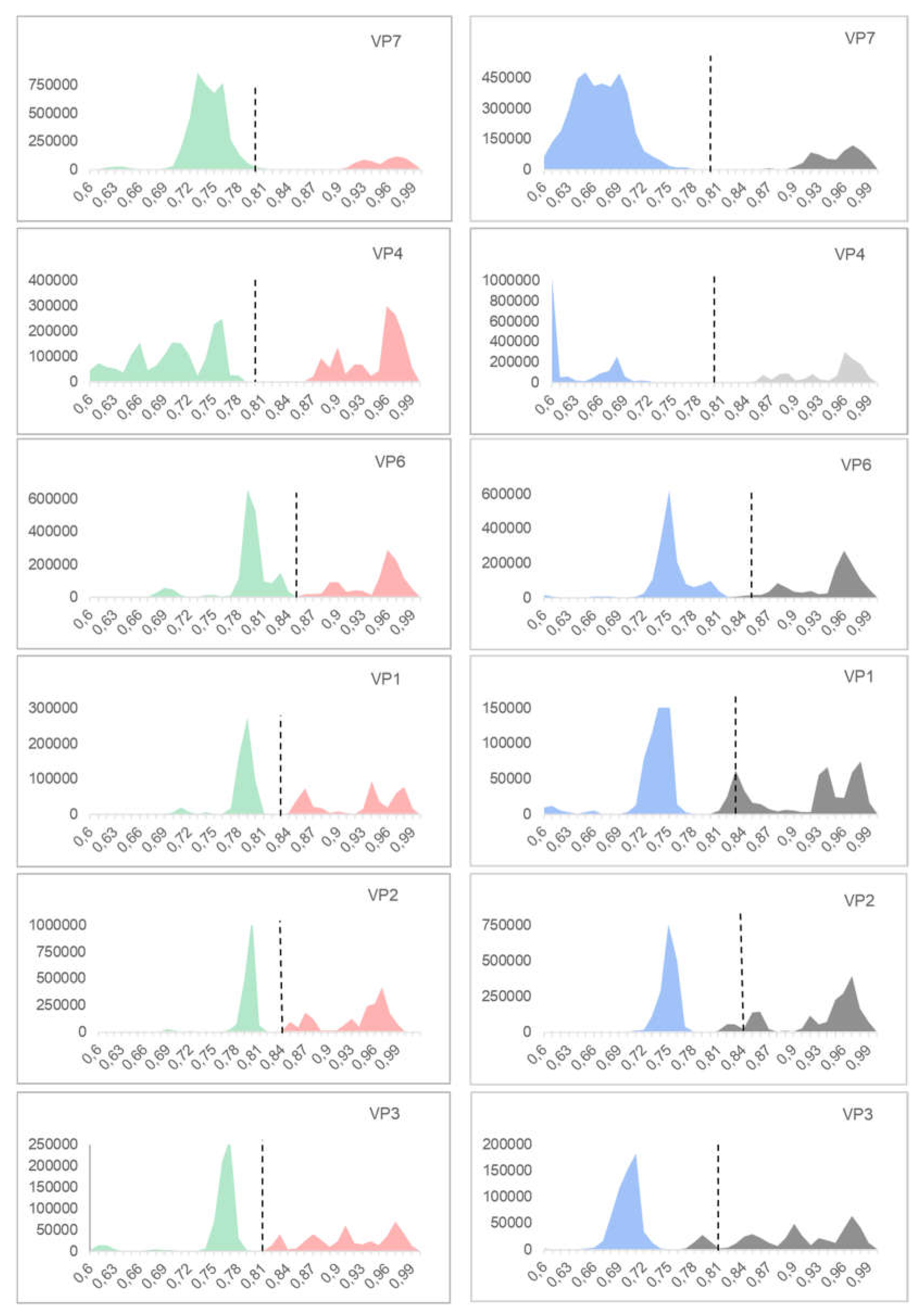

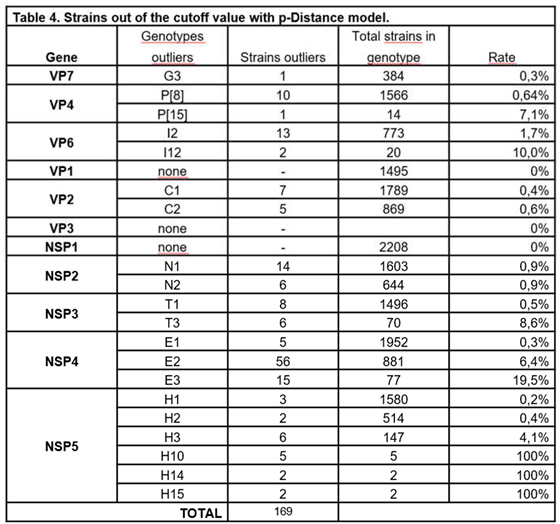

3.1. p-Distance Analysis

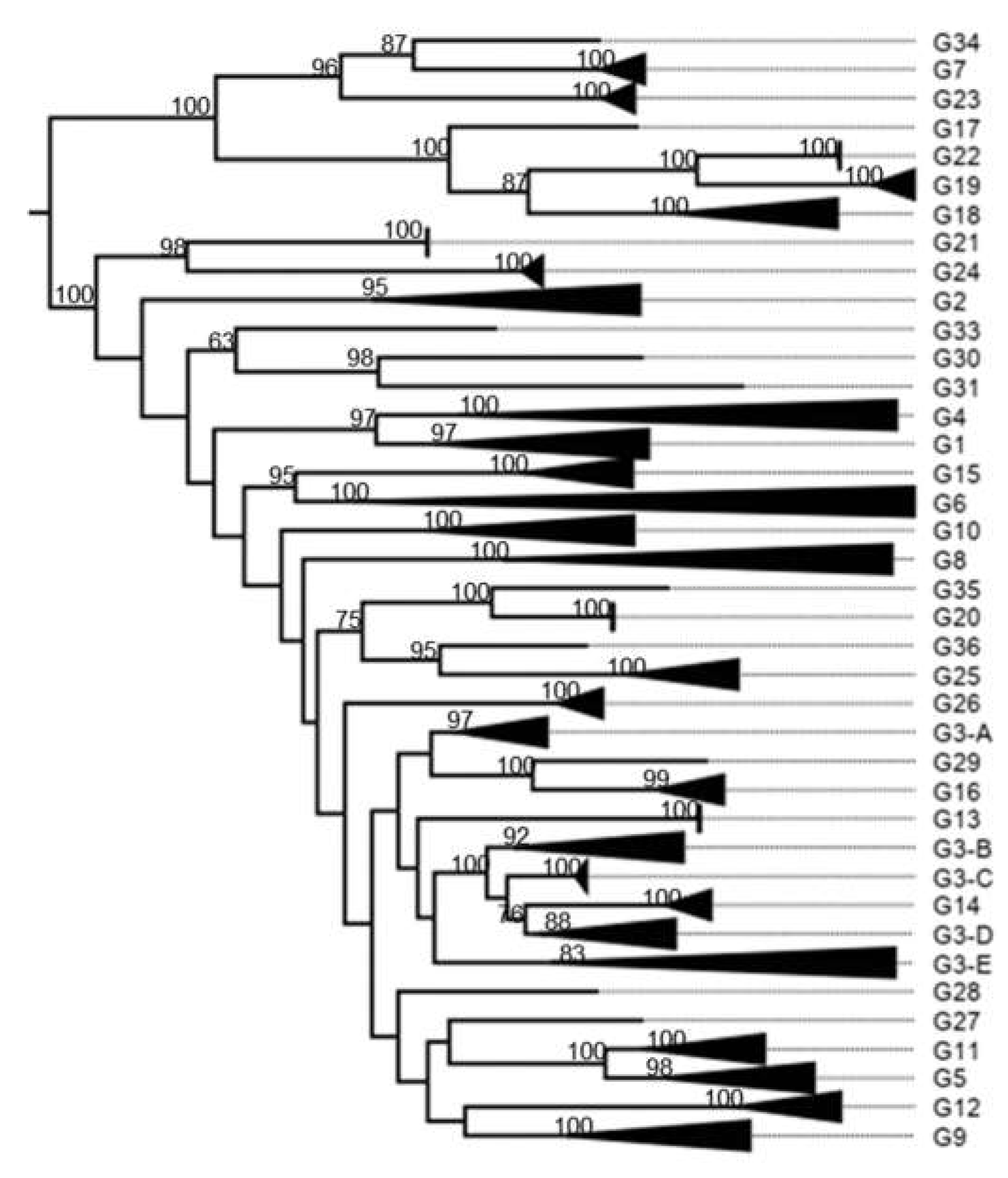

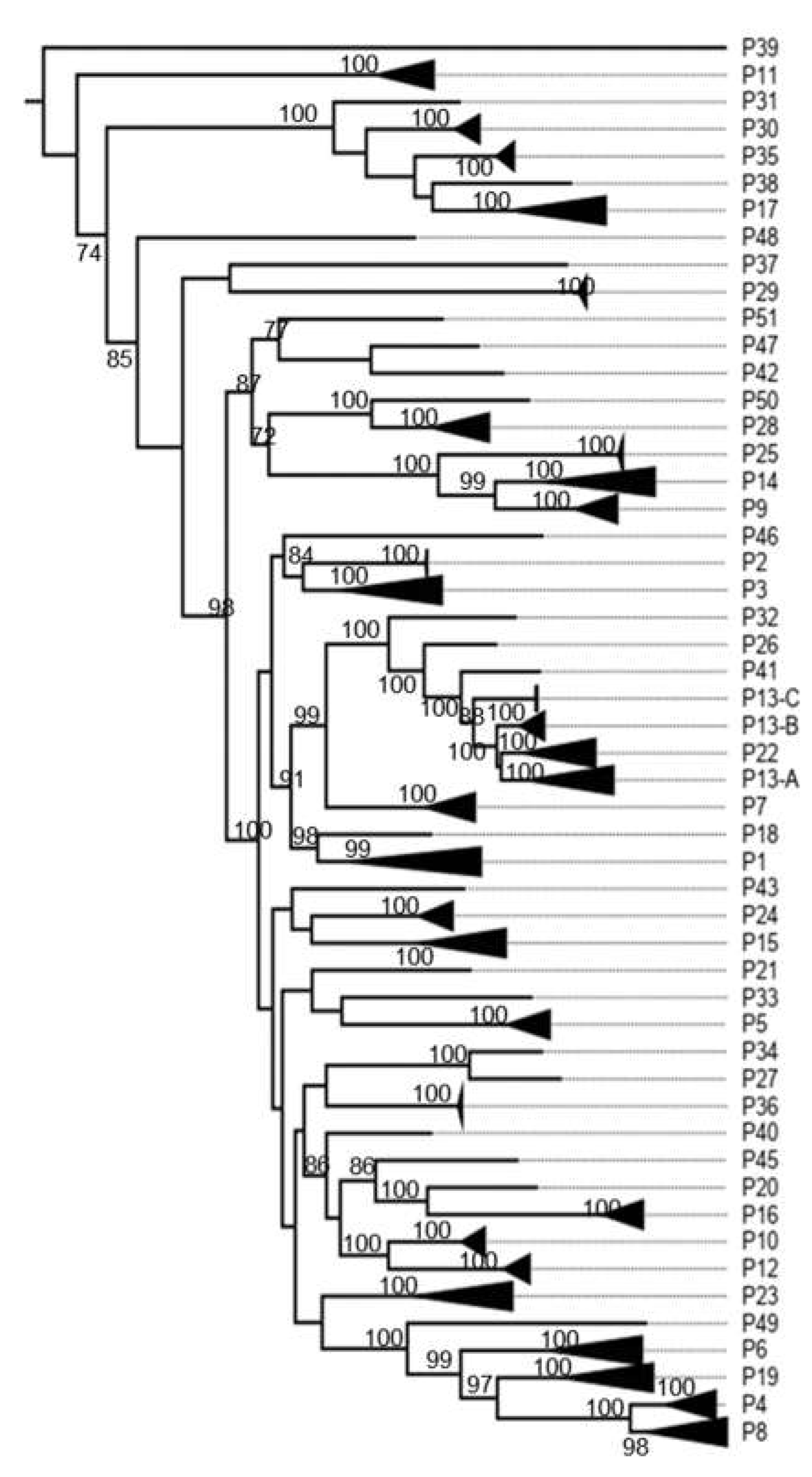

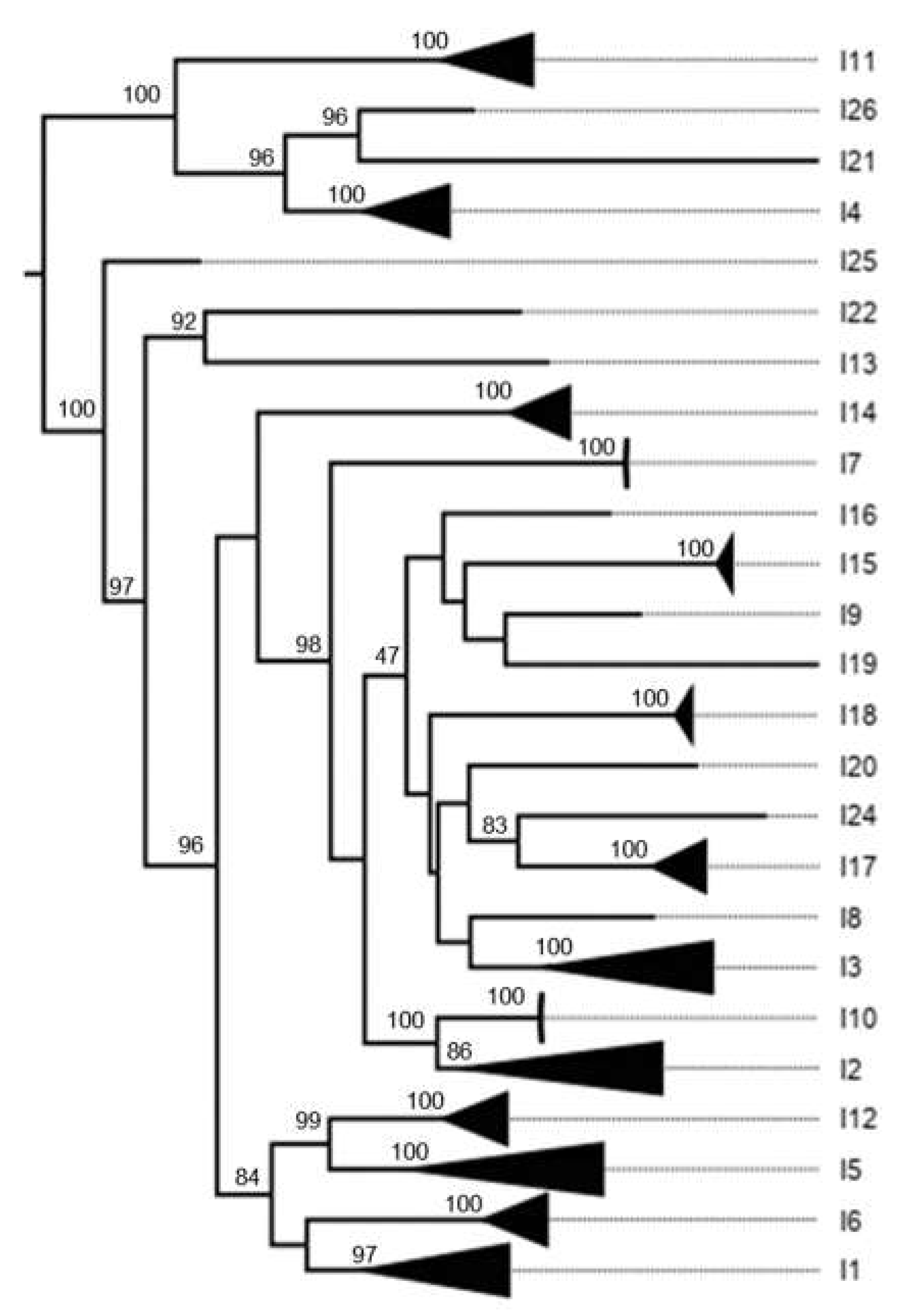

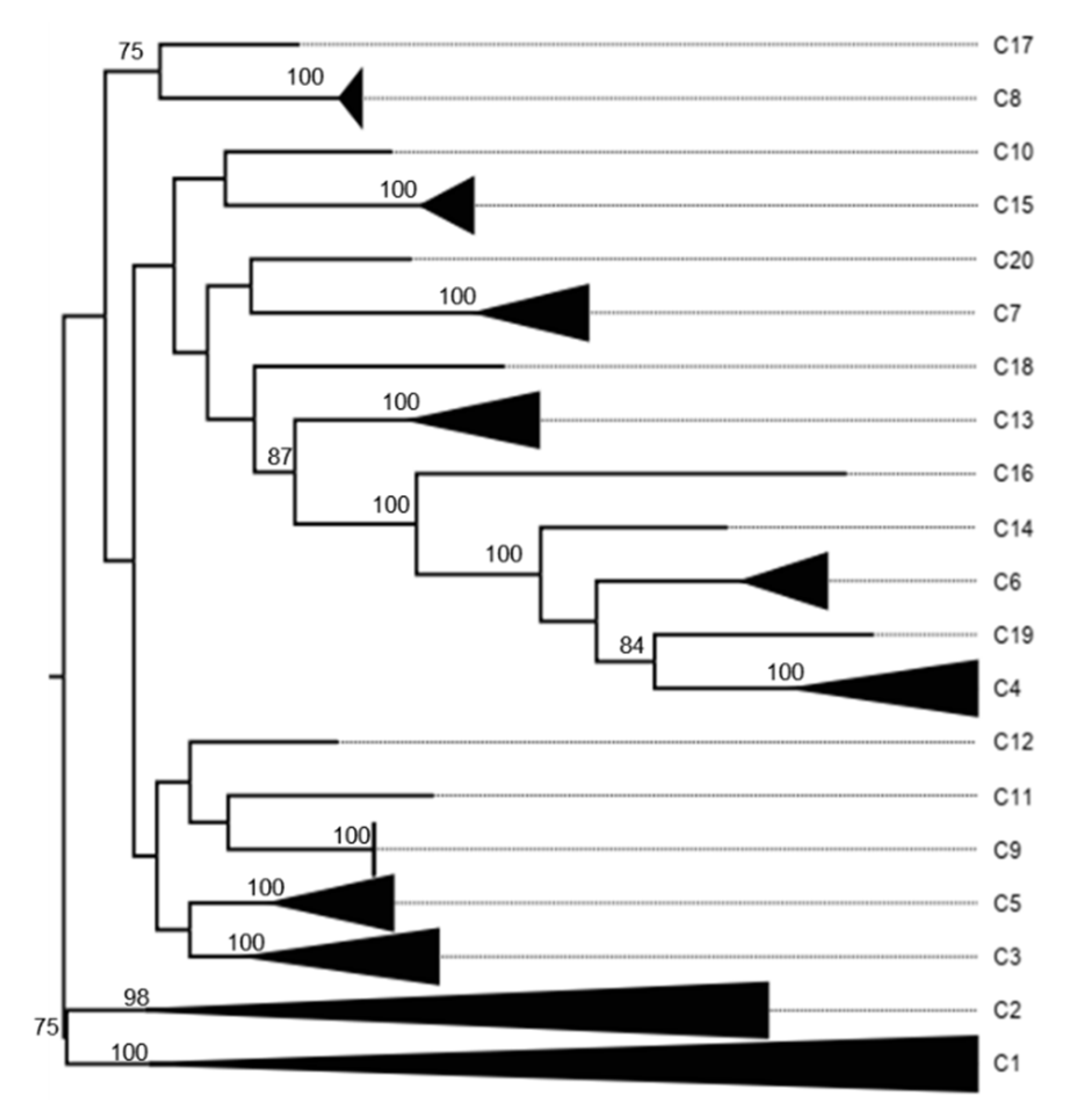

3.2. K2P Analysis: Outer Capsid Proteins (VP7, VP4 and VP6)

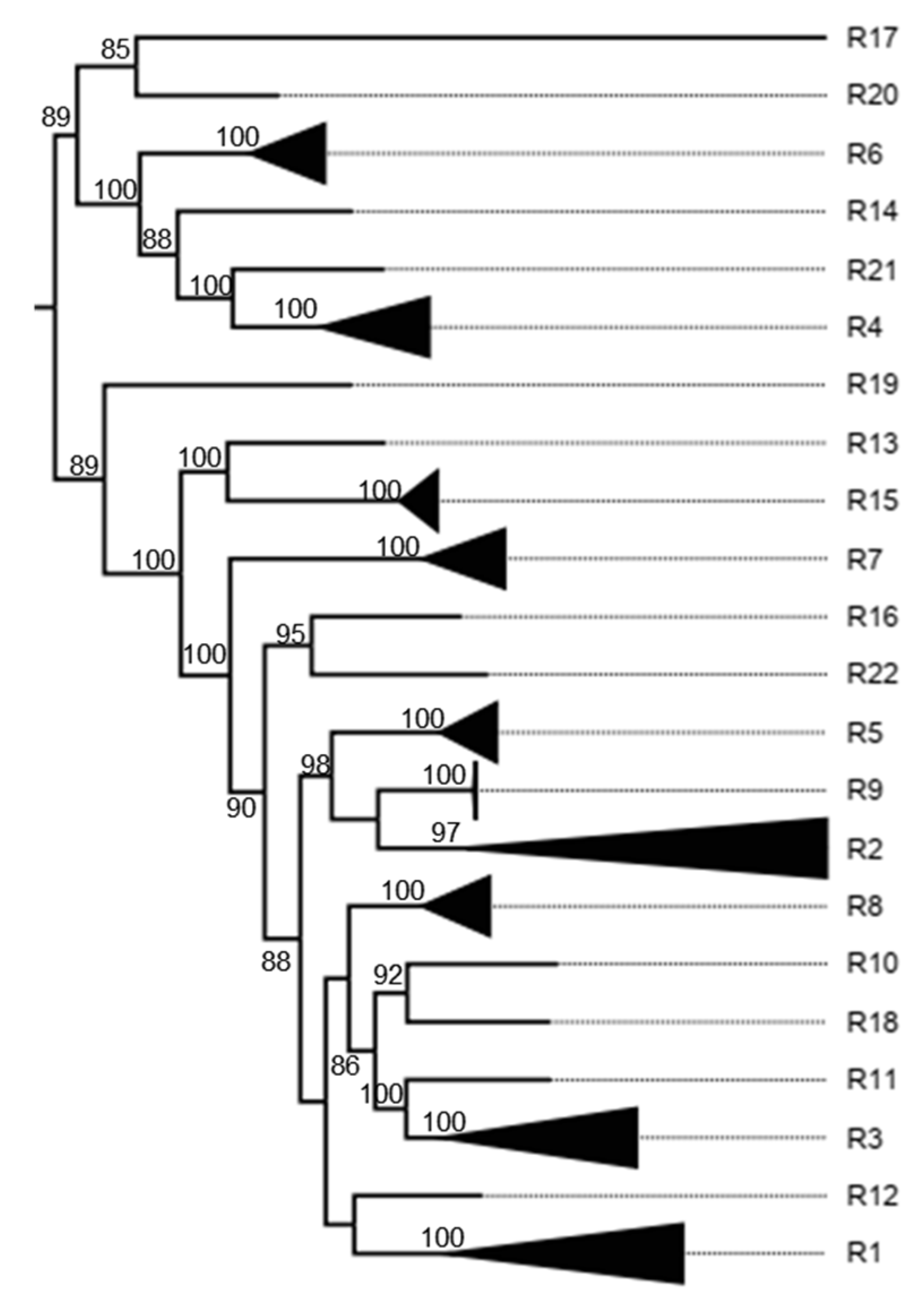

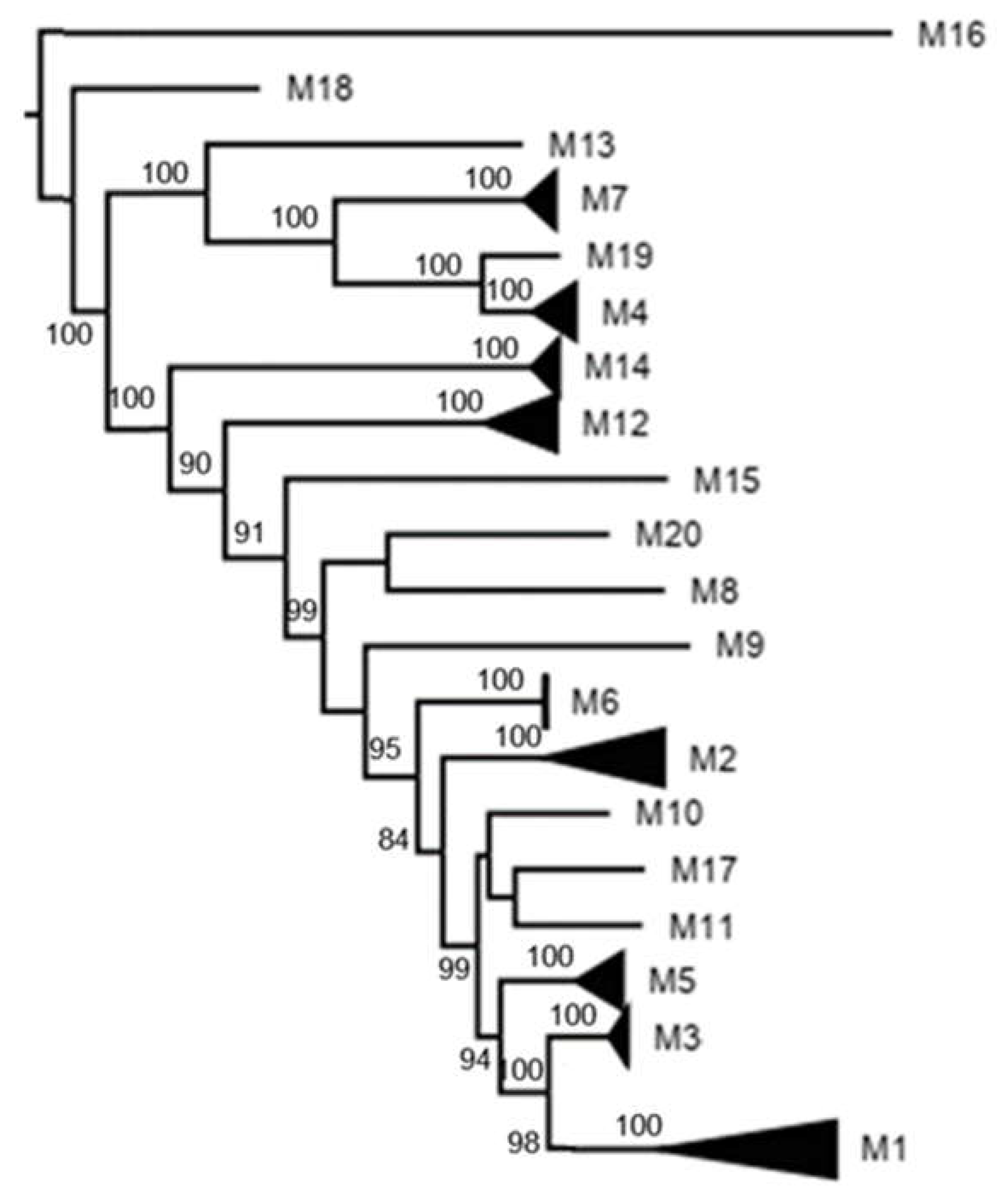

3.3. K2P Analysis: Inner Capsid Proteins (VP1, VP2 and VP3)

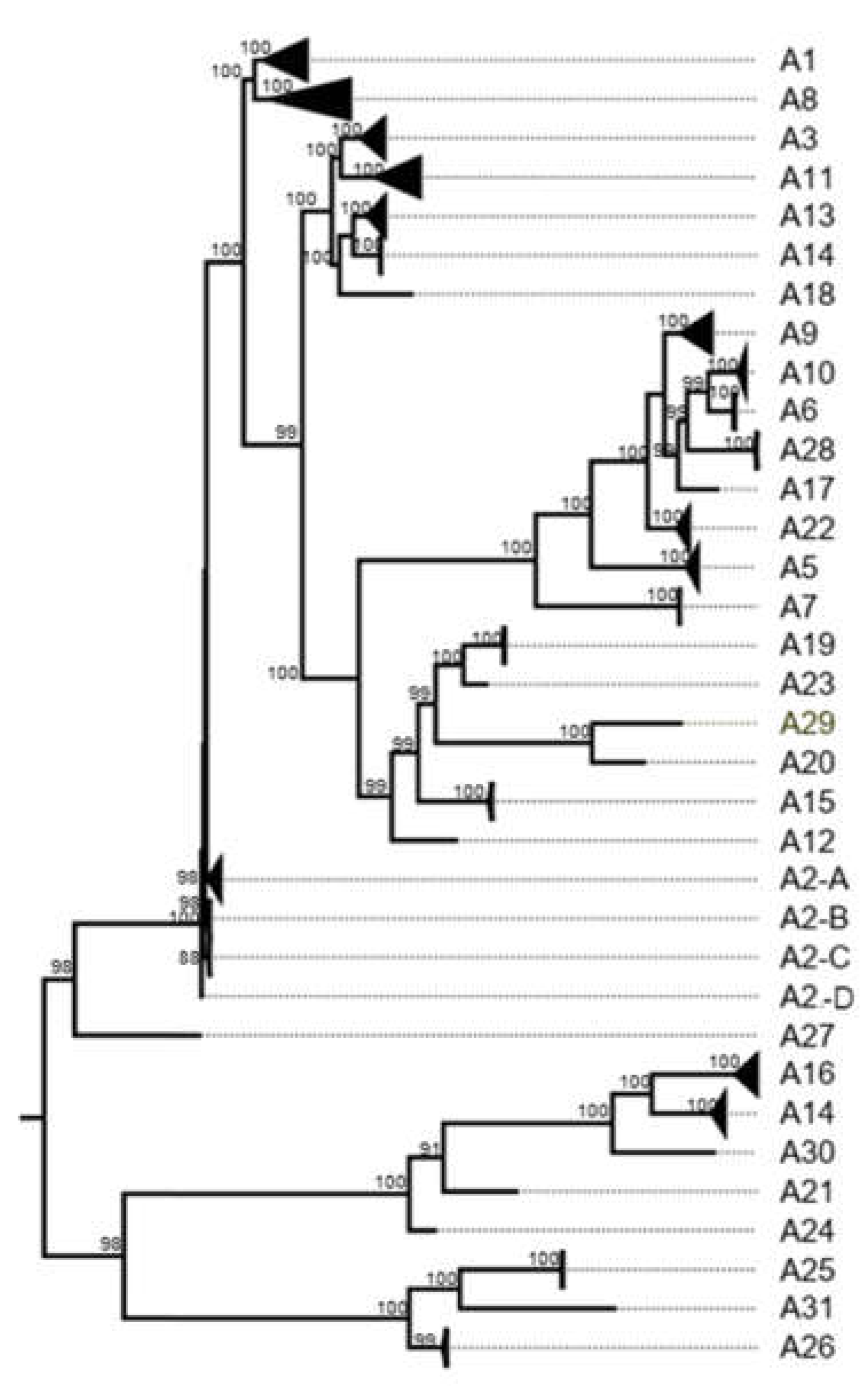

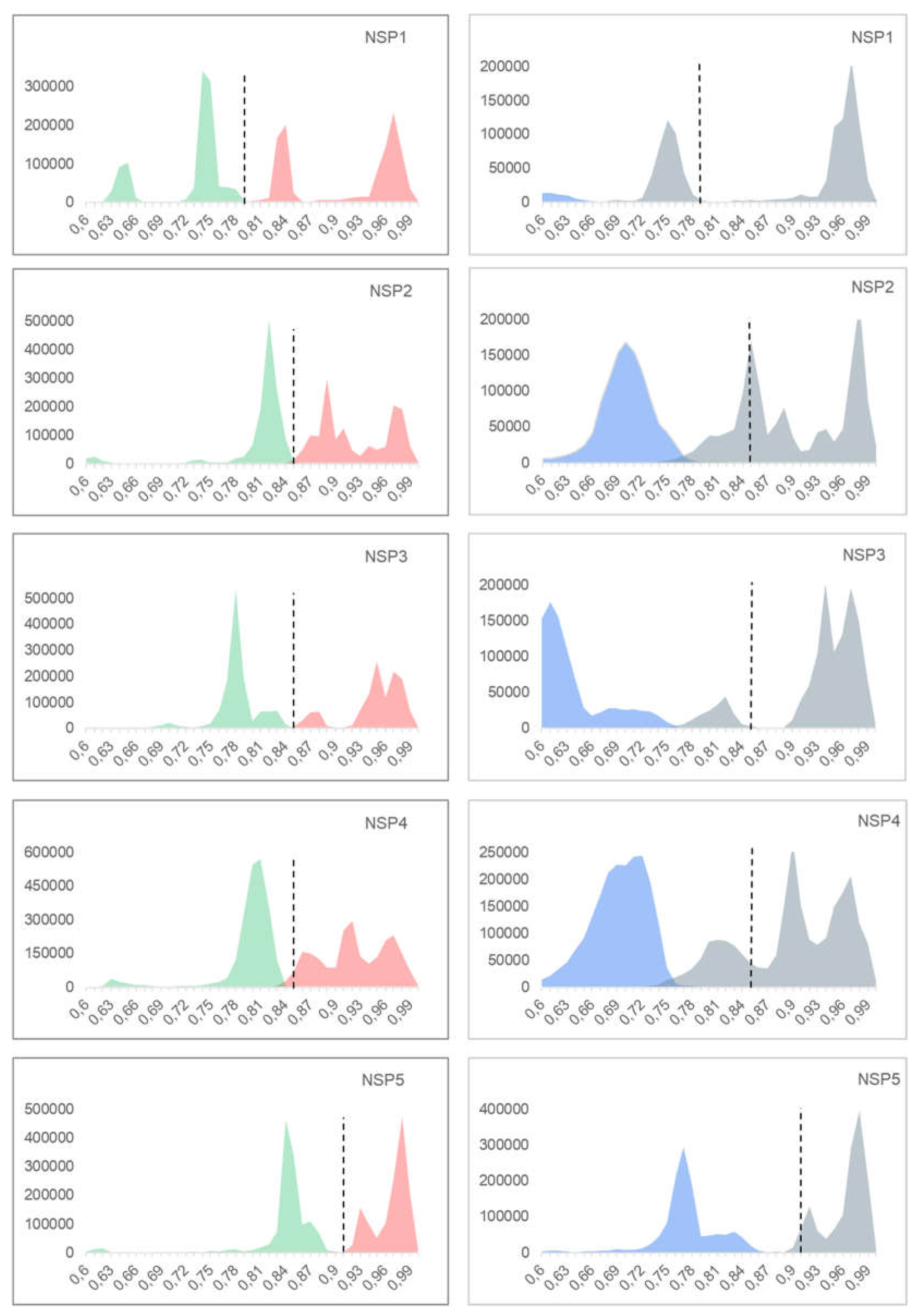

3.4. Other Models Analysis: Non-Structural Proteins

3.5. Comparison Between the p-Distance and K2P

4. Discussion

4.1. p-Distance Model vs. K2P

4.2. K2P Model

4.2.1. Proteins Forming the Triple Layer Particles

4.2.2. Nonstructural Proteins

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Base frequency and substitution rate of all genes and evolution models suggested by MegaX. | |||||||||||||

| Gene | Base frequency % | Nucleotide substitution frequencies | Evolution Model* | Gamma parameter | |||||||||

| G | A | T | C | G - T | G - A | G - C | A - T | A - C | T - C | Tree | Distance Matrix | ||

| VP7 | 31 | 36 | 18 | 15 | 1 | 9.2 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 11.1 | GTR + F + R8 | Kimura 2-parameter | 4 |

| VP4 | 30 | 37 | 18 | 15 | 1 | 9.5 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 12.2 | GTR + F + R7 | Kimura 2-parameter | 4 |

| VP6 | 30 | 34 | 19 | 17 | 1 | 12.6 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 16.3 | GTR + F + R5 | Kimura 2-parameter | 4 |

| VP1 | 30 | 38 | 17 | 15 | 1 | 14.0 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 20.7 | GTR + F + R10 | Kimura 2-parameter | 4 |

| VP2 | 29 | 38 | 18 | 15 | 1 | 14.3 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 22.3 | GTR + F + R8 | Kimura 2-parameter | 4 |

| VP3 | 32 | 38 | 16 | 14 | 1 | 14.3 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 20.7 | GTR + F + R10 | Kimura 2-parameter | 4 |

| NSP1 | 37 | 17 | 33 | 13 | 1 | 10.0 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 14.4 | GTR + F + R10 | Tamura 3-parameter | 0.88 |

| NSP2 | 37 | 18 | 31 | 14 | 1 | 12.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 16.5 | GTR + F + R10 | Tamura 3-parameter | 0.48 |

| NSP3 | 38 | 19 | 31 | 12 | 1 | 10.9 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 17.4 | GTR + F + R10 | Tamura 3-parameter | 0.56 |

| NSP4 | 39 | 19 | 27 | 15 | 1 | 8.0 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 10.6 | GTR + F + R10 | Tamura-Nei | 0.72 |

| NSP5 | 35 | 19 | 29 | 17 | 1 | 8.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 10.4 | GTR + F + R10 | Tamura 3-parameter | 0.51 |

| Average | 33.5 | 28.5 | 23.4 | 14.7 | 1.0 | 11.2 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 15.7 | |||

| * The evolutionary model used to construct the phylogenetic tree or the distance matrix. | |||||||||||||

References

- Desselberger, U. Rotaviruses. Virus Res 2014, 190, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knipe, D.M.; Howley, P.M.; Griffin, D.E.; Lamb, A.R.; Martin, M.A.; Roizman, B.; Straus, S.E. Rotavirus. In Fields Virology; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P.M., Eds.; Philadelphia, 2013; pp. 1347–1401.

- Guglielmi K, M.J.D.P.C.M.P.J. Genus Rotavirus: Type Species A. In Virus Taxonomy: Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses; Fauquet, C., Mayo, M., Maniloff, J., Desselberger, U., Ball, A., Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press, Holland.: Amsterdam, 2011; pp. 484–499. [Google Scholar]

- Ciarlet M, E.M. Rotaviruses: Basic Biology, Epidemiology and Methodologies. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Microbiology; Bitton, G, Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, USA: New York, 2002; pp. 2753–2773. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagomi, O.; Nakagomi, T.; Akatani, K.; Ikegami, N. Identification of Rotavirus Genogroups by RNA-RNA Hybridization. Mol Cell Probes 1989, 3, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthijnssens, J.; Ciarlet, M.; Heiman, E.; Arijs, I.; Delbeke, T.; McDonald, S.M.; Palombo, E.A.; Iturriza-Gómara, M.; Maes, P.; Patton, J.T.; et al. Full Genome-Based Classification of Rotaviruses Reveals a Common Origin between Human Wa-Like and Porcine Rotavirus Strains and Human DS-1-Like and Bovine Rotavirus Strains. J Virol 2008, 82, 3204–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackhall, J.; Fuentes, A.; Magnusson, G. Genetic Stability of a Porcine Rotavirus RNA Segment during Repeated Plaque Isolation. Virology 1996, 225, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miño, S.; Barrandeguy, M.; Parreño, V.; Parra, G.I. Genetic Linkage of Capsid Protein-Encoding RNA Segments in Group A Equine Rotaviruses. Journal of General Virology 2016, 97, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Alarcón, R.G.; Liotta, D.J.; Miño, S. Zoonotic RVA: State of the Art and Distribution in the Animal World. Viruses 2022, 14, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martella, V.; Bányai, K.; Matthijnssens, J.; Buonavoglia, C.; Ciarlet, M. Zoonotic Aspects of Rotaviruses. Vet Microbiol 2010, 140, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, N.; Bridger, J.; Kendall, K.; Gomara, M.I.; El-Attar, L.; Gray, J. The Zoonotic Potential of Rotavirus. Journal of Infection 2004, 48, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, H.; Matthijnssens, J.; Martella, V.; Ciarlet, M.; Bányai, K. Global Distribution of Group A Rotavirus Strains in Horses: A Systematic Review. Vaccine 2013, 31, 5627–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papp, H.; László, B.; Jakab, F.; Ganesh, B.; De Grazia, S.; Matthijnssens, J.; Ciarlet, M.; Martella, V.; Bányai, K. Review of Group A Rotavirus Strains Reported in Swine and Cattle. Vet Microbiol 2013, 165, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Kobayashi, N. Exotic Rotaviruses in Animals and Rotaviruses in Exotic Animals. Virusdisease 2014, 25, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dóró, R.; László, B.; Martella, V.; Leshem, E.; Gentsch, J.; Parashar, U.; Bányai, K. Review of Global Rotavirus Strain Prevalence Data from Six Years Post Vaccine Licensure Surveillance: Is There Evidence of Strain Selection from Vaccine Pressure? Infect Genet Evol 2014, 28, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simón, D.; Cristina, J.; Musto, H. Nucleotide Composition and Codon Usage Across Viruses and Their Respective Hosts. Front Microbiol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shackelton, L.A.; Parrish, C.R.; Holmes, E.C. Evolutionary Basis of Codon Usage and Nucleotide Composition Bias in Vertebrate DNA Viruses. J Mol Evol 2006, 62, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, S.; Shackelton, L.A.; Holmes, E.C. Rates of Evolutionary Change in Viruses: Patterns and Determinants. Nat Rev Genet 2008, 9, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjuán, R.; Nebot, M.R.; Chirico, N.; Mansky, L.M.; Belshaw, R. Viral Mutation Rates. J Virol 2010, 84, 9733–9748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, J.K.; Kirkegaard, K. Increased Fidelity Reduces Poliovirus Fitness and Virulence under Selective Pressure in Mice. PLoS Pathog 2005, 1, 0102–0110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignuzzi, M.; Stone, J.K.; Arnold, J.J.; Cameron, C.E.; Andino, R. Quasispecies Diversity Determines Pathogenesis through Cooperative Interactions in a Viral Population. Nature 2006, 439, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignuzzi, M.; Wendt, E.; Andino, R. Engineering Attenuated Virus Vaccines by Controlling Replication Fidelity. Nat Med 2008, 14, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, S.A.; Lee, C.A.; Zhao, Y.; Smidansky, E.D.; August, A.; Arnold, J.J.; Cameron, C.E. A Polymerase Mechanism-Based Strategy for Viral Attenuation and Vaccine Development. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 31618–31622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.P.; Daifuku, R.; Loeb, L.A. Viral Error Catastrophe by Mutagenic Nucleosides. Annu Rev Microbiol 2004, 58, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.C. Evolutionary History and Phylogeography of Human Viruses. Annu Rev Microbiol 2008, 62, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolhouse, M.; Gaunt, E. Ecological Origins of Novel Human Pathogens. Crit Rev Microbiol 2007, 33, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combe, M.; Sanjuán, R. Variation in RNA Virus Mutation Rates across Host Cells. PLoS Pathog 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthijnssens, J.; Ciarlet, M.; Rahman, M.; Attoui, H.; Estes, M.K.; Gentsch, J.R.; Iturriza-gómara, M.; Kirkwood, C.; Mertens, P.P.C.; Nakagomi, O.; et al. Recommendations for the Classification of Group A Rotaviruses Using All 11 Genomic RNA Segments. Arch Virol 2008, 153, 1621–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotavirus Classification Working Group: RCWG Home page [https://rega.kuleuven.be/cev/viralmetagenomics/virus-classification/rcwg] Newly Assigned Genotypes, List of accepted genotypes.

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nlshikawa, K.; Hoshino, Y.; Taniguchi, K.; Green, K.Y.; Greenberg, H.B.; Kapikian, A.; Chanock, R.M.; Gorziglia, M. Rotavirus VP7 Neutralization Epitopes of Serotype 3 Strains. Virology 1989, 171, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemey, P.; Salemi, M.; Vandamme, A.-M. The Phylogenetic Handbook, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2009; Volume 6, ISBN 9786021018187. [Google Scholar]

- Bonkoungou, I.J.O.; Damanka, S.; Sanou, I.; Tiendrebeogo, F.; Coulibaly, S.O.; Bon, F.; Haukka, K.; Traore, A.S.; Barro, N.; Armah, G.E. Genotype Diversity of Group A Rotavirus Strains in Children With Acute Diarrhea in Urban Burkina Faso, 2008-2010. J Med Virol 2011, 83, 1485–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciarlet, M.; Hoshino, Y.; Liprandi, F. Single Point Mutations May Affect the Serotype Reactivity of Serotype G11 Porcine Rotavirus Strains: A Widening Spectrum? J Virol 1997, 71, 8213–8220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciarlet, M.; Reggeti, F.; Pina, ’ C.I.; Liprandil, F. Equine Rotaviruses with G14 Serotype Specificity Circulate among Venezuelan Horses. J Clin Microbiol 1994, 2609–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morozova, O. V.; Sashina, T.A.; Epifanova, N. V.; Zverev, V. V.; Kashnikov, A.U.; Novikova, N.A. Phylogenetic Comparison of the VP7, VP4, VP6, and NSP4 Genes of Rotaviruses Isolated from Children in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, 2015–2016, with Cogent Genes of the Rotarix and RotaTeq Vaccine Strains. Virus Genes 2018, 54, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatte, V.S.; Maran, D.; Walimbe, A.M.; Gopalkrishna, V. Rotavirus G9P[4], G9P[6] and G1P[6] Strains Isolated from Children with Acute Gastroenteritis in Pune, Western India, 2013–2015: Evidence for Recombination in Genes Encoding VP3, VP4 and NSP1. Journal of General Virology 2019, 100, 1605–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sircar, S.; Malik, Y.S.; Kumar, P.; Ansari, M.I.; Bhat, S.; Shanmuganathan, S.; Kattoor, J.J.; Vinodhkumar, O.R.; Rishi, N.; Touil, N.; et al. Genomic Analysis of an Indian G8P[1] Caprine Rotavirus-A Strain Revealing Artiodactyl and DS-1-Like Human Multispecies Reassortment. Front Vet Sci 2021, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Navarro, R.; Malik, Y.S.; Willingham, A.L.; Kobayashi, N. Whole Genomic Analysis of a Porcine G6P[13] Rotavirus Strain. Vet Microbiol 2015, 180, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianiro, G.; Di Bartolo, I.; De Sabato, L.; Pampiglione, G.; Ruggeri, F.M.; Ostanello, F. Detection of Uncommon G3P[3] Rotavirus A (RVA) Strain in Rat Possessing a Human RVA-like VP6 and a Novel NSP2 Genotype. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2017, 53, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamim, S.; Matthijnssens, J.; Heylen, E.; Zeller, M.; Van Ranst, M.; Salman, M.; Hasan, F. Evidence of Zoonotic Transmission of VP6 and NSP4 Genes into Human Species A Rotaviruses Isolated in Pakistan in 2010. Arch Virol 2019, 164, 1781–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Yue, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Tang, C. Genomic Analysis Reveals G3P[13] Porcine Rotavirus A Interspecific Transmission to Human from Pigs in a Swine Farm with Diarrhoea Outbreak. Journal of General Virology 2021, 102, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, R.; Li, D.; Wang, J.; Xiong, G.; Wang, M.; Liu, D.; Wei, Y.; Pang, L.; Sun, X.; Li, H.; et al. Reassortment and Genomic Analysis of a G9P[8]-E2 Rotavirus Isolated in China. Virol J 2023, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, A.; Gulati, B.R.; Maan, S.; Mor, S.; Kumar, D.; Soman, R.; Punia, S.; Chaudhary, D.; Khurana, S.K. Complete Genome Sequencing Reveals Unusual Equine Rotavirus A of Bat Origin from India. J Virol 2022, 96, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Zhang, X.; Shi, H.; Chen, J.; Shi, D.; Dong, H.; Feng, L. A G3P[13] Porcine Group A Rotavirus Emerging in China Is a Reassortant and a Natural Recombinant in the VP4 Gene. Transbound Emerg Dis 2018, 65, e317–e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, M.F.M.; Tort, L.F.L.; Goméa, M.M.; Assis, R.M.S.; Volotão, E. de M.; De Mendonça, M.C.L.; Bello, G.; Leite, J.P.G. VP7 Gene of Human Rotavirus A Genotype G5: Phylogenetic Analysis Reveals the Existence of Three Different Lineages Worldwide. J Med Virol 2011, 83, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Gauhar, M.; Bubber, P.; Ray, P. Phylogenetic Analysis of VP7 and VP4 Genes of the Most Predominant Human Group A Rotavirus G12 Identified in Children with Acute Gastroenteritis in Himachal Pradesh, India during 2013–2016. J Med Virol 2021, 93, 6200–6209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degiuseppe, J.I.; Martelli, A.; Barrios Mathieur, C.; Stupka, J.A. Genetic Diversity of Rotavirus A in Argentina during 2019-2022: Detection of G6 Strains and Insights Regarding Its Dissemination. Arch Virol 2023, 168, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takatsuki, H.; Agbemabiese, C.A.; Nakagomi, T.; Pun, S.B.; Gauchan, P.; Muto, H.; Masumoto, H.; Atarashi, R.; Nakagomi, O.; Pandey, B.D. Whole Genome Characterisation of G11P[25] and G9P[19] Rotavirus A Strains from Adult Patients with Diarrhoea in Nepal. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2019, 69, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estes, M.K.Z. Rotaviruses and Their Replication. In Fields virology; B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, S. E. Straus, Eds.; Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2007; pp. 1917–1974.

- Yasutaka Hoshino; Ronald W. Jones; Robert M. Chanock; Albert Z. Kapikian Generation and Characterization of Six Single VP4 Gene Substitution Reassortant Rotavirus Vaccine Candidates: Each Bears a Single Human Rotavirus VP4 Gene Encoding P Serotype 1A[8] or 1B[4] and the Remaining 10 Genes of Rhesus Monkey Rotavirus MMU18006 or Bovine Rotavirus UK. Vaccine 2002, 20, 3576–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorziglia, M.; Larralde, G.; Kapikian, A.Z.; Chanock, R.M. Antigenic Relationships among Human Rotaviruses as Determined by Outer Capsid Protein VP4 (Rotavirus VP4 Expression/Rotavirus VP4 Serotypes/Rotavirus VP8/Rotavirus VP5); 1990; Vol. 87.

- Chen, J.; Grow, S.; Iturriza-Gómara, M.; Hausdorff, W.P.; Fix, A.; Kirkwood, C.D. The Challenges and Opportunities of Next-Generation Rotavirus Vaccines: Summary of an Expert Meeting with Vaccine Developers. Viruses 2022, 14, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhama, K.; Saminathan, M.; Karthik, K.; Tiwari, R.; Shabbir, M.Z.; Kumar, N.; Malik, Y.S.; Singh, R.K. Avian Rotavirus Enteritis – an Updated Review. Veterinary Quarterly 2015, 35, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Comparison between Previous and Present Work | ||||||||

| Gene | Encoded protein | Notation | Cutoff Value | 2008* | This work (2024) | Current Genotype | ||

| Strains | Genotypes | Strains | Genotypes | |||||

| VP7 | Glycosylated | G | 80 | 1,000 | 15 | 3172 | 36 | 42 |

| VP4 | Protease-sensitive | P | 80 | 190 | 27 | 2771 | 51 | 58 |

| VP6 | Inner capsid | I | 85 | 142 | 10 | 2463 | 26 | 32 |

| VP1 | RNA- polymerase | R | 83 | 58 | 4 | 1495 | 22 | 28 |

| VP2 | Core protein | C | 84 | 58 | 5 | 2754 | 20 | 24 |

| VP3 | Methyltransferase | M | 81 | 67 | 6 | 1507 | 20 | 23 |

| NSP1 | Interferon Antagonist | A | 79 | 100 | 14 | 2208 | 31 | 39 |

| NSP2 | NTPase | N | 85 | 71 | 5 | 2358 | 22 | 28 |

| NSP3 | Translation enhancer | T | 85 | 77 | 7 | 2294 | 22 | 28 |

| NSP4 | Enterotoxin | E | 85 | 100 | 6 | 3183 | 27 | 32 |

| NSP5 | pHosphoprotein | H | 91 | 113 | 6 | 2332 | 22 | 28 |

| Reference Strains for Each Genotypes | |||||||||||

| Strain name | VP7 | VP4 | VP6 | VP1 | VP2 | VP3 | NSP1 | NSP2 | NSP3 | NSP4 | NSP5 |

| RVA/Human-tc/USA/WaCS/1974/G1P[8] | G1 | P[8] | I1 | R1 | C1 | M1 | A1 | N1 | T1 | E1 | H1 |

| RVA/Human-tc/USA/DS-1/1976/G2P[4] | G2 | P[4] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | A2 | N2 | T2 | E2 | H2 |

| RVA/Human-tc/JPN/AU-1/1982/G3P[9] | G3 | P[9] | I3 | R3 | C3 | M3 | A3 | N3 | T3 | E3 | H3 |

| RVA/Human-tc/GBR/ST3/1975/G4P2A[6] | G4 | P[6] | I1 | R1 | C1 | M1 | A1 | N1 | T1 | E1 | H1 |

| RVA/Pig-tc/USA/Gottfried/1983/G4P[6] | G4 | P[6] | I1 | R1 | C1 | M1 | A8 | N1 | T1 | E1 | H1 |

| RVA/Pig-tc/USA/OSU/1975/G5P[7] | G5 | P[7] | I5 | R1 | C1 | M1 | A1 | N1 | T1 | E1 | H1 |

| RVA/Cow-tc/USA/NCDV-Lincoln/1971/G6P[1] | G6 | P[1] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | - | N2 | T6 | E2 | - |

| RVA/Human-wt/HUN/Hun5/1997/G6P[14] | G6 | P[14] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | A11 | N2 | T6 | E2 | H3 |

| RVA/Turkey-tc/IRL/Ty-3/1979/G7P[35] | G7 | P[35] | I4 | R4 | C4 | M4 | A16 | N4 | T4 | E11 | H14 |

| RVA/Human-wt/COD/DRC86/2003/G8P[6] | G8 | P[6] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | A2 | N2 | T2 | E2 | H2 |

| RVA/Human-tc/USA/WI61/1983/G9P1A[8] | G9 | P[8] | I1 | R1 | C1 | M1 | A1 | N1 | T1 | E1 | H1 |

| RVA/Human/IND/I321/1996/G10P[11] | G10 | P[11] | I2 | - | - | - | A1 | N2 | T1 | E2 | - |

| RVA/Human-wt/BGD/Dhaka6/2001/G11P[25] | G11 | P[25] | I1 | R1 | C1 | M1 | A1 | N1 | T1 | E1 | H1 |

| RVA/Human-tc/PHL/L26/1987/G12P[4] | G12 | P[4] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | A2 | N1 | T2 | E2 | H1 |

| RVA/Human-tc/THA/T152/1998/G12P[9] | G12 | P[9] | I3 | R3 | C3 | M3 | A12 | N3 | T3 | E3 | H6 |

| RVA/Horse-tc/GBR/L338/1991/G13P[18] | G13 | P[18] | I6 | R9 | C9 | M6 | A6 | N9 | T12 | E14 | H11 |

| RVA/Horse-tc/USA/FI23/1981/G14P[12] | G14 | P[12] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M3 | A10 | N2 | T3 | E2 | H7 |

| RVA/Cow/IND/Hg18/XXXX/G15P[21] | G15 | P[21] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | E2 | - |

| RVA/Mouse-tc/USA/EDIM/XXXX/G16P[16] | G16 | P[16] | I7 | R7 | C7 | M8 | A7 | N7 | T10 | E7 | H9 |

| RVA/Turkey-tc/IRL/Ty-1/1979/G17P[38] | G17 | P[38] | I4 | R4 | C4 | M4 | A16 | N4 | T4 | E4 | H4 |

| RVA/Pigeon-tc/PO-13/1983/G18P[17] | G18 | P[17] | I4 | R4 | C4 | M4 | A4 | N4 | T4 | E4 | H4 |

| RVA/Chicken-tc/DEU/06V0661/2006/G19P[31] | G19 | P[31] | I11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | H8 |

| RVA/Chicken-tc/IRL/Ch-1/1979/G19P[30] | G19 | P[17] | I10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | H10 |

| RVA/Simian-tc/ZAF/SA11-H96/1958/G3P[2] | G3 | P[2] | I2 | R2 | C5 | M5 | A5 | N5 | T5 | E2 | H5 |

| RVA/Cat-tc/AUS/Cat97/1984/G3P[3] | G3 | P[3] | I3 | R3 | C2 | M3 | A9 | N2 | T3 | E3 | H6 |

| RVA/Cow-tc/USA/WC3/1981/G6P[5] | G6 | P[5] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | A3 | N2 | T6 | E2 | H3 |

| RVA/Human-tc/GBR/ST3/1975/G4P2A[6] | G4 | P[6] | I1 | R1 | C1 | M1 | A1 | N1 | T1 | E1 | H1 |

| RVA/Cat-tc/AUS/Cat2/1984/G3P[9] | G3 | P[9] | I3 | R3 | C2 | M3 | A3 | N1 | T6 | E3 | H3 |

| RVA/Human-tc/IDN/69M/1980/G8P4[10] | G8 | P[10] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | A2 | N2 | T2 | E2 | H2 |

| RVA/Cow-tc/THA/A5-13/1988/G8P[1] | G8 | P[1] | - | - | - | - | A14 | - | - | - | - |

| RVA/Cow-tc/USA/B223/1983/G10P[11] | G10 | P[11] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | A13 | N2 | T6 | E2 | H3 |

| RVA/Horse-tc/GBR/H-2/1976/G3P[12] | G3 | P[12] | I6 | R2 | C2 | M3 | A10 | N2 | T3 | E2 | H7 |

| RVA/Human-wt/IND/HP140/1987/G6P[13] | G6 | P[13] | I2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | E1 | H1 |

| RVA/Sheep-tc/ESP/OVR762/2002/G8P[14] | G8 | P[14] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | A11 | N2 | T6 | E2 | H3 |

| RVA/Ovine/CHN/Lp14/1981/G10P[15] | G10 | P[15] | I2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | E2 | H3 |

| RVA/Human/IND/RMC321/1989/G9P[19] | G9 | P[19] | I5 | - | - | - | A1 | N1 | T1 | E1 | H1 |

| RVA/Mouse/Brazil/EHP/1981/G16P[20 | G16 | P[20] | - | - | - | - | A7 | - | - | E7 | - |

| RVA/Rabbit/ITA/160-01/2002/G3P[22] | G3 | P[22] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | E5 | - |

| RVA/Pig-wt/ESP/34461-4/2003/G2P[23] | G2 | P[23] | I5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | E1 | H1 |

| RVA/Rhesus-wt/USA/TUCH/2002/G3P[24] | G3 | P[24] | I9 | R3 | C3 | M3 | A9 | N1 | T3 | E3 | H6 |

| RVA/Human-wt/NPL/KTM368/2004/G11P[25] | G11 | P[25] | I12 | R1 | C1 | M1 | A1 | N1 | T1 | E1 | H1 |

| RVA/Human-tc/ITA/PA260-97/1997/G3P[3] | G3 | P[3] | I3 | R3 | C3 | M3 | A15 | N2 | T3 | E3 | H6 |

| RVA/Cow-wt/ARG/B383/1998/G15P[11] | G15 | P[11] | I2 | R5 | C2 | M2 | A13 | N2 | T6 | E12 | H3 |

| RVA/Horse-wt/ARG/E30/1993/G3P[12] | G3 | P[12] | I6 | R2 | C2 | M3 | A10 | N2 | T3 | E12 | H7 |

| RVA/Pig/ITA/134/04-15/2003/G5P[26] | G5 | P[26] | I5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | E1 | - |

| RVA/Dog-tc/ITA/RV198-95/1995/G3P[3] | G3 | P[3] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | E8 | - |

| RVA/Pig/THA/CMP034/2000/G20P[27] | G2 | P[27] | I5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | E9 | H1 |

| RVA/Human-wt/ECU/Ecu534/2006/G20P[28] | G20 | P[28] | I13 | R13 | C13 | M12 | A23 | N13 | T15 | E20 | H15 |

| RVA/Cow-wt/JPN/Azuk-1/2006/G21P[29] | G21 | P[29] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | A13 | N2 | T9 | E2 | H3 |

| RVA/Turkey-tc/DEU/03V0002E10/2003/G22P[35] | G22 | P[35] | I4 | R4 | C4 | M4 | A16 | N4 | T4 | E11 | H4 |

| RVA/Chicken-tc/DEU/02V0002G3/2002/G19P[30] | G19 | P[30] | I11 | R6 | C6 | M7 | A16 | N6 | T8 | E10 | H8 |

| RVA/Pig-wt/IRL/61-07-ire/2007/G2P[32] | G2 | P[32] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RVA/Pheasant-wt/HUN/Phea14246/2008/G23P[x] | G23 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RVA/Pig-wt/CAN/CE-M-06-0003/2005/G2P[27] | G2 | P[27] | I14 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RVA/Cow-tc/JPN/Dai-10/2007/G24P[33] | G24 | P[33] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | A13 | N2 | T9 | E2 | H3 |

| RVA/Cow-wt/JPN/Azuk-1/2006/G21P[29] | G21 | P[29] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | A13 | N2 | T9 | E2 | H3 |

| RVA/Mouse-tc/USA/ETD_822/XXXX/G16P[16] | G16 | P[16] | I7 | R7 | C7 | M8 | A7 | N7 | T10 | E7 | H9 |

| RVA/Bat-wt/KEN/KE4852/07/2007/G25P[6] | G25 | P[6] | I15 | - | C8 | - | - | N8 | T11 | E2 | H10 |

| RVA/Pig-wt/JPN/FGP51/2009/G4P[34] | G4 | P[34] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RVA/Human-tc/KEN/B10/1987/G3P[2] | G3 | P[2] | I16 | R8 | C5 | M5 | A5 | N5 | T5 | E13 | H5 |

| RVA/Pig-wt/JPN/TJ4-1/2010/G26P[X] | G26 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RVA/SugarGlider-tc/JPN/SG385/2012/G27P[36] | G27 | P[36] | I19 | R10 | C10 | M9 | A20 | N11 | T13 | E17 | H12 |

| RVA/Camel-wt/KUW/21s/2010/G10P[15] | G10 | P[15] | I1 | R1 | C2 | - | - | N2 | T2 | E15 | H3 |

| RVA/vicugna-wt/ARG/C75/2010/G8P[14] | G8 | P[14] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | - | N2 | T6 | E16 | - |

| RVA/Rabbit-tc/CHN/N5/1992/G3P[14] | G3 | P[14] | I17 | R3 | C3 | M3 | A9 | N1 | T1 | E3 | H2 |

| RVA/Alpaca-wt/PER/356/2010/G3P[14] | G3 | P[14] | I2 | R5 | C3 | M3 | A17 | N3 | T6 | E3 | H3 |

| RVA/Pheasant-tc/GER/10V0112H5/2010/G23P[37] | G23 | P[37] | I4 | R4 | C4 | M4 | A16 | N10 | T4 | E4 | H4 |

| RVA/Camel-wt/SDN/MRC-DPRU447/2004/G8P[11] | G8 | P[11] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | A18 | N2 | T6 | E2 | H3 |

| RVA/Human-wt/BRA/QUI-35-F5/2010/G3P[9] | G3 | P[9] | I18 | R3 | C3 | M3 | A19 | N3 | T3 | E3 | H6 |

| RVA/VelvetScoter-tc/JPN/RK1/1989/G18P[17] | G18 | P[17] | I4 | R4 | C4 | M4 | A21 | N4 | T4 | E4 | H4 |

| RVA/Rat-wt/GER/KS-11-573/2011/G3P[3] | G3 | P[3] | I20 | R11 | C11 | M10 | A22 | N2 | T14 | E18 | H13 |

| RVA/Fox-wt/ITA/288356/2011/G18P[17] | G18 | P[17] | I4 | R4 | C4 | M4 | A16 | N4 | T4 | E19 | H4 |

| RVA/Turkey-tc/IRL/Ty-3/1979/G7P[17] | G7 | P[17] | I4 | R4 | C4 | M4 | A16 | N4 | T4 | E11 | H14 |

| RVA/Human-wt/ITA/ME848-12/2012/G12P[8] | G12 | P[8] | I17 | R12 | C12 | M11 | A12 | N12 | T7 | E6 | H2 |

| RVA/Human-wt/SUR/2014735512/2013/G20P[28] | G20 | P[28] | R13 | C13 | M12 | A23 | N13 | T15 | E20 | H15 | |

| RVA/Common_Gull-wt/JPN/Ho374/2013/G28P[39] | G28 | P[39] | I21 | R14 | C14 | M13 | A24 | N14 | T16 | E21 | H16 |

| RVA/Alpaca-tc/PER/SA44/2014/G3P[40] | G3 | P[40] | I8 | R3 | C3 | M3 | A9 | N3 | T3 | E3 | H6 |

| RVA/Human-wt/BEL/BEF06018/2014/G29P[41] | G29 | P[41] | I2 | R2 | C2 | M2 | A3 | N2 | T6 | E2 | H3 |

| Strain name | VP7 | VP4 | VP6 | VP1 | VP2 | VP3 | NSP1 | NSP2 | NSP3 | NSP4 | NSP5 |

| RVA/Bat-wt/CMR/BatLi09/2014/G30P[42] | G30 | P[42] | I22 | R15 | C15 | M14 | A25 | N15 | T17 | E22 | H17 |

| RVA/Bat-wt/CMR/BatLi08/2014/G31P[42] | G31 | P[42] | I22 | R15 | C15 | M14 | A25 | N15 | T17 | E22 | H17 |

| RVA/Bat-wt/CMR/BatLi10/2014/G30P[42] | G30 | P[42] | I23 | R15 | C15 | M14 | A25 | N15 | T17 | E22 | H17 |

| RVA/Bat-wt/CMR/BatLy03/2014/G25P[43] | G25 | P[43] | I15 | R16 | C8 | M15 | A26 | N8 | T11 | E23 | H10 |

| RVA/Bat-wt/NLD/NPpipi1/2014/GxP[44] | - | P[44] | I23 | R17 | C16 | M16 | A27 | N16 | T18 | - | H18 |

| RVA/Rat-wt/CHN/RA116/2013/G3P[45] | G3 | P[45] | I3 | R3 | C3 | M10 | A22 | N3 | T3 | E3 | H13 |

| RVA/Shrew-wt/CHN/LW9/2013/G32P[46] | G32 | P[46] | I24 | R18 | C17 | M17 | A28 | N17 | T19 | E24 | H19 |

| RVA/Bat-wt/CMR/BatLy17/2014/G30P[47] | G30 | P[47] | I22 | R15 | C15 | M14 | A25 | N15 | T17 | E22 | H17 |

| RVA/Rat-wt/ITA/Rat14/2015/G3P[3] | G3 | P[3] | I1 | R11 | C11 | M10 | A22 | N18 | T14 | E18 | H13 |

| RVA/Bat-wt/CHN/GLRL1/2005/G33P[48] | G33 | P[48] | I25 | R19 | C18 | M18 | - | N19 | T20 | E25 | H20 |

| RVA/Bat-wt/CHN/YSSK5/2015/G3P[3] | G3 | P[3] | I8 | R20 | C2 | M1 | A9 | N3 | T3 | E3 | H6 |

| RVA/Bat-wt/CHN/BSTM70/2015/G3P[3] | G3 | P[3] | I8 | R3 | C3 | M3 | A29 | N3 | T3 | E3 | H6 |

| RVA/Raccoon-wt/JPN/Rac-311/2011/G34P[17] | G34 | P[17] | I26 | R21 | C19 | M19 | A30 | N20 | T21 | E26 | H21 |

| RVA/Pig-wt/BGD/214016006/2014/G9P[49] | G9 | P[49] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RVA/Alpaca-wt/PER/Alp11B/2010/G35P[50] | G35 | P[50] | I13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | E16 | H6 |

| RVA/Bat-wt/ZMB/ZFB14-126/2014/GxP[x] | - | - | I22 | - | - | - | - | N21 | T17 | E27 | - |

| RVA/Bat-wt/KEN/BATp39/2015/G36P[51] | G36 | P[51] | I16 | R22 | C20 | M20 | A31 | N22 | T22 | E27 | H22 |

| RVA/Bat/CRC/KCR10-93/2010/G20P[47] | G20 | P[47] | I13 | R13 | C13 | M12 | A32 | N13 | T23 | E20 | - |

| RVA/Bat/GAB/GKS-929/2009/G3P[2] | G3 | P[2] | I30 | R8 | C5 | M5 | A36 | N23 | T5 | E28 | H5 |

| RVA/Bovine-wt/UMN-VDL/2018/G37P[52] | G37 | P[52] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RVA/common-shrew/KS-11-2281/2011/GXP[X] | - | - | I27 | R23 | - | - | - | - | - | - | H23 |

| RVA/Bat-wt/KEN/11/2008/G30P[53] | G30 | P[53] | - | - | - | - | A33 | - | - | - | H24 |

| RVA/Bat-wt/GTM/56/2010/G38P[54] | G38 | P[54] | I28 | R24 | C21 | M21 | A34 | N24 | T24 | E29 | H25 |

| RVA/Bat-wt/NGA/59/2011/GXP[2] | - | P[2] | I16 | R8 | C3 | M5 | A35 | N3 | T3 | - | - |

| RVA/Bat-wt/GTM/53/2009/GxPx | - | - | I29 | R25 | - | - | - | N25 | T25 | - | - |

| RVA/Shrew-wt/GER/KS14-269/2014/G39P[55] | G39 | P[55] | - | R26 | C22 | M22 | A37 | N26 | T26 | E30 | H26 |

| RVA/JungleCrow-wt/JPN/JC-105/2019/G40P[56] | G40 | P[56] | I26 | R21 | C19 | M19 | A30 | N20 | T21 | E26 | H21 |

| RVA/MultimammateMouse-wt/ZMB/MpR12/2012/G41P[57] | G41 | P[57] | I31 | R27 | C23 | M23 | A38 | N27 | T27 | E31 | H27 |

| RVA/Shrew-wt/GER/KS11-0893/2010/G42P[58] | G42 | P[58] | I32 | R28 | C24 | L24 | A39 | N28 | T28 | E32 | H28 |

| Comparison between Models | ||||

| Gene | 2008* | This work | ||

| Strains Analyzed | Strains Analyzed |

P-Distyance Out the Cutoff |

K2P Out the Cutoff |

|

| VP7 | 1,000 | 3172 | 1 | 215 |

| VP4 | 190 | 2771 | 11 | 45 |

| VP6 | 142 | 2463 | 15 | 95 |

| VP1 | 58 | 1495 | - | 262 |

| VP2 | 58 | 2754 | 12 | 199 |

| VP3 | 67 | 1507 | - | 165 |

| NSP1 | 100 | 2208 | - | 502 |

| NSP2 | 71 | 2358 | 20 | 1234 |

| NSP3 | 77 | 2294 | 14 | 255 |

| NSP4 | 100 | 3183 | 76 | 1025 |

| NSP5 | 113 | 2332 | 20 | 252 |

| *Work of 2008 [4]. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).