Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

30 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- How can AI techniques be leveraged to systematically incorporate political, social, and cultural dimensions into macroeconomic modeling for Brazil?

- To what extent does this integrated approach enhance forecasting accuracy compared to traditional modeling approaches?

- Which factors across economic, political, social, and cultural dimensions most significantly influence Brazil's economic outcomes?

- How can an integrated AI-enhanced approach improve policy design and optimization in the Brazilian context?

- How do the relationships between different dimensions vary across Brazil's diverse regions, and what implications does this have for regional development strategies?

2. Methodology

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. Data Approach

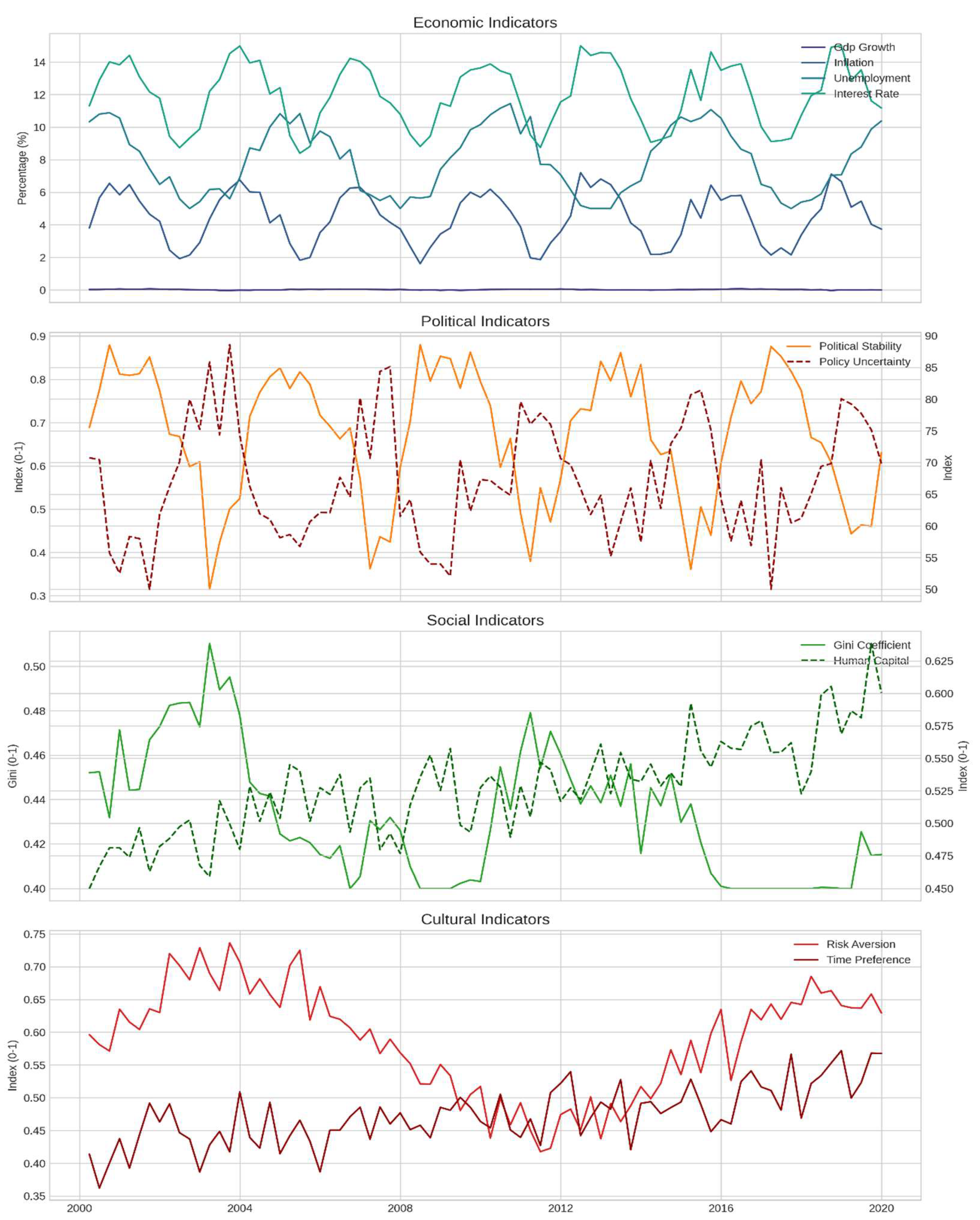

-

Economic dimension:

- GDP growth rate (%)

- Inflation rate (%)

- Unemployment rate (%)

- Interest rate (%)

- Exchange rate (BRL/USD)

-

Political dimension:

- Political stability index (0-1)

- Policy uncertainty index

-

Social dimension:

- Gini coefficient (0-1)

- Human capital index (0-1)

-

Cultural dimension:

- Risk aversion index (0-1)

- Time preference index (0-1)

- Cyclical patterns in economic variables, with cycles of varying frequency and amplitude

- Structural breaks corresponding to major political events (e.g., elections, impeachment)

- Gradual trends in social and cultural variables reflecting long-term development processes

- Correlations between variables across different dimensions based on theoretical relationships and empirical evidence

- Realistic noise and volatility patterns calibrated to historical Brazilian data

- Economic data: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), Central Bank of Brazil, Ministry of Economy, International Monetary Fund, World Bank

- Political data: Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset, World Governance Indicators, Economic Policy Uncertainty Index

- Social data: IBGE, Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA), World Bank, United Nations Development Programme

- Cultural data: World Values Survey, Hofstede Cultural Dimensions, regional surveys and ethnographic studies

2.3. AI-Enhanced Modeling Approach

2.3.1. Exploratory Data Analysis and Dimensionality Reduction

- Time series visualization by dimension to identify temporal patterns and potential structural breaks

- Correlation analysis to quantify bivariate relationships between variables across dimensions

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify the underlying structure of the multidimensional data and reduce dimensionality while preserving information

- The PCA approach is particularly valuable for understanding how variables from different dimensions cluster and interact. Mathematically, PCA transforms the original variables into a new set of uncorrelated variables (principal components) that capture the maximum variance in the data. For a data matrix with observations and variables, PCA finds a transformation matrix such that Equation (2.3.1): , where is the matrix of principal components. The columns of are the eigenvectors of the covariance matrix , ordered by their corresponding eigenvalues. This allows us to identify which combinations of variables across different dimensions explain the most variance in Brazil's economic system.

2.3.2. Network Analysis of Interdependencies

2.3.5. Regional Analysis

2.4. Mathematical Formulation of the Integrated Model

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance and Validation

3.1.1. Time Series Analysis of Multidimensional Indicators

3.1.2. Correlation Analysis of Cross-Dimensional Relationships

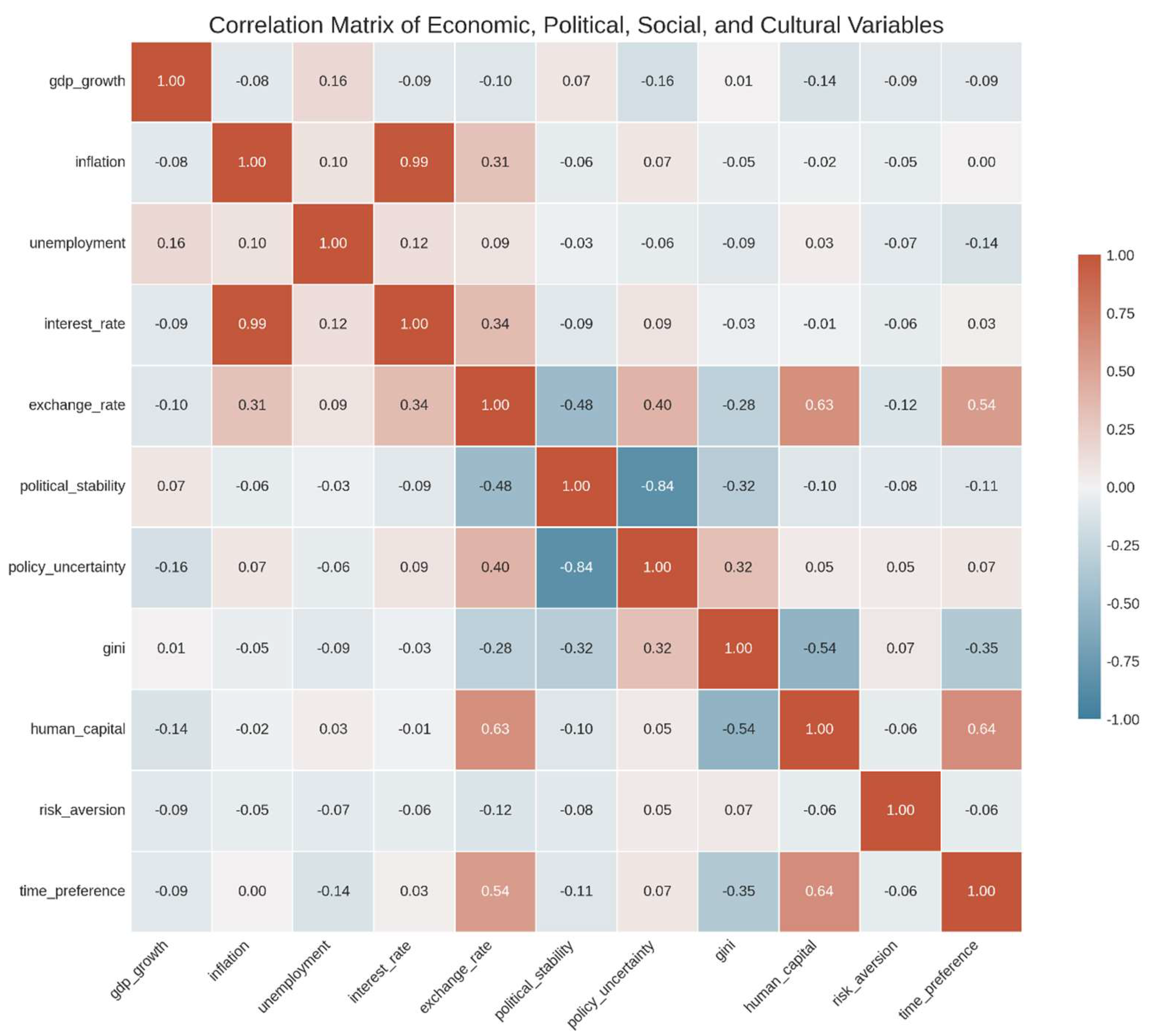

- Economic-Political Relationships: The strong negative correlation (-0.48) between political stability and exchange rate volatility highlights how political uncertainty affects Brazil's currency markets. Similarly, the strong negative correlation (-0.84) between political stability and policy uncertainty demonstrates how political instability translates into unpredictable policy environments.

- Economic-Social Relationships: The positive correlation (0.63) between human capital and exchange rate suggests that improvements in education and skills are associated with stronger currency performance, possibly reflecting increased economic competitiveness. The negative correlation (-0.54) between human capital and inequality (Gini coefficient) indicates that investments in human capital may contribute to reducing social disparities.

- Social-Cultural Relationships: The positive correlation (0.64) between human capital and time preference demonstrates how educational development is associated with more future-oriented cultural attitudes. Conversely, the negative correlation (-0.35) between inequality and time preference suggests that high inequality may discourage long-term planning and investment.

- Economic-Cultural Relationships: The positive correlation (0.54) between time preference and exchange rate indicates that more future-oriented cultural attitudes are associated with stronger currency performance, possibly reflecting increased saving and investment.

- Monetary Policy Relationships: The near-perfect correlation (0.99) between inflation and interest rates reflects the Central Bank of Brazil's inflation-targeting regime, where interest rates are adjusted in response to inflation pressures.

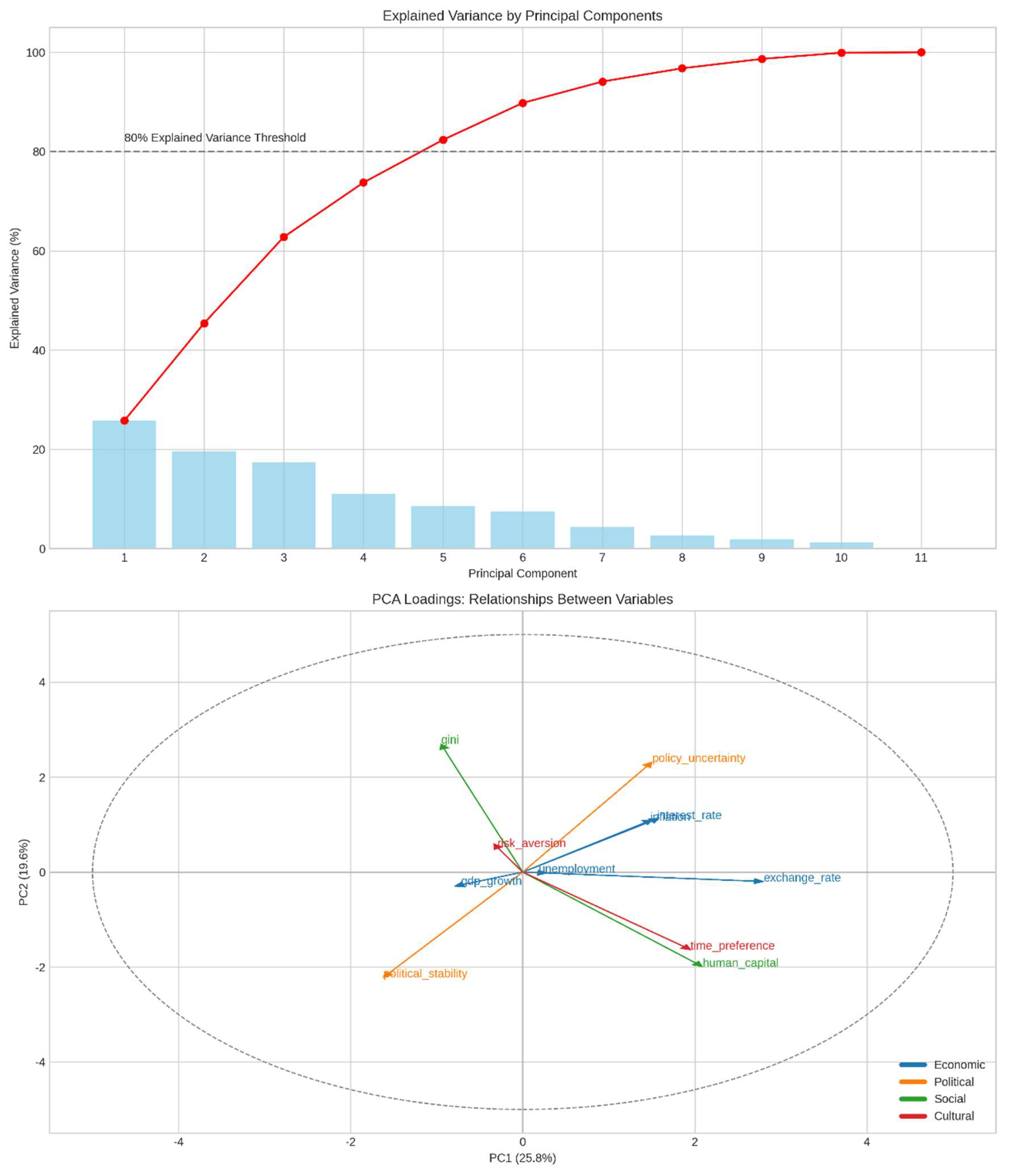

3.1.3. Principal Component Analysis of Multidimensional Data

- The first principal component (PC1) primarily captures the relationship between exchange rate, human capital, and time preference on the positive side, and political stability on the negative side. This component can be interpreted as representing "institutional development and future orientation," with higher values indicating stronger institutions, better human capital, and more future-oriented cultural attitudes.

- The second principal component (PC2) contrasts policy uncertainty and gini coefficient on the positive side with political stability and human capital on the negative side. This component can be interpreted as representing "socio-political instability," with higher values indicating greater policy uncertainty and inequality.

- Economic variables like GDP growth, inflation, and interest rates load on both components, reflecting their complex relationships with both institutional development and socio-political instability.

3.2. Economic Forecasting Enhancement

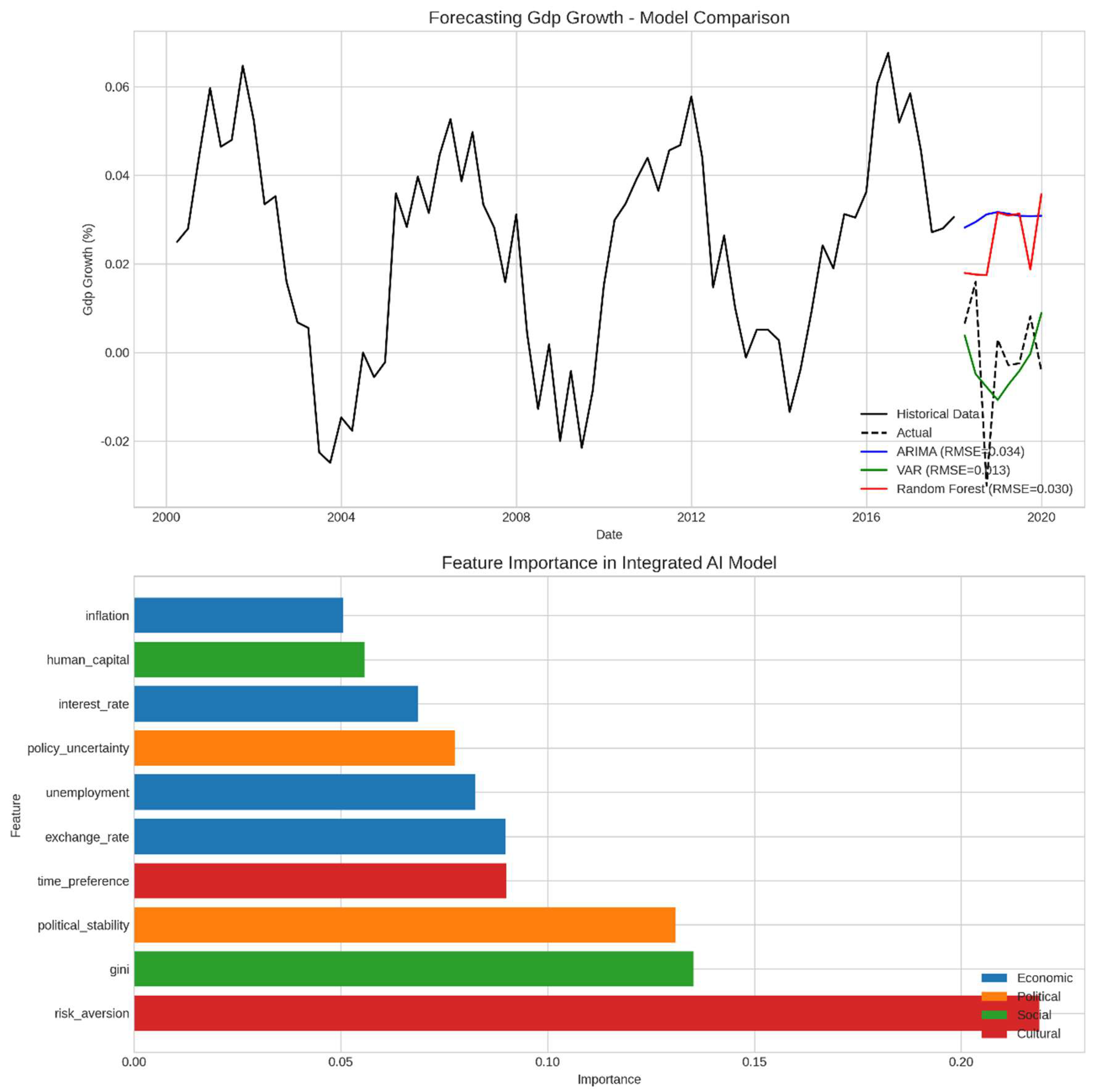

3.2.1. Comparative Analysis of Forecasting Models

3.2.2. Feature Importance Analysis

3.3. Network Analysis of Interdependencies

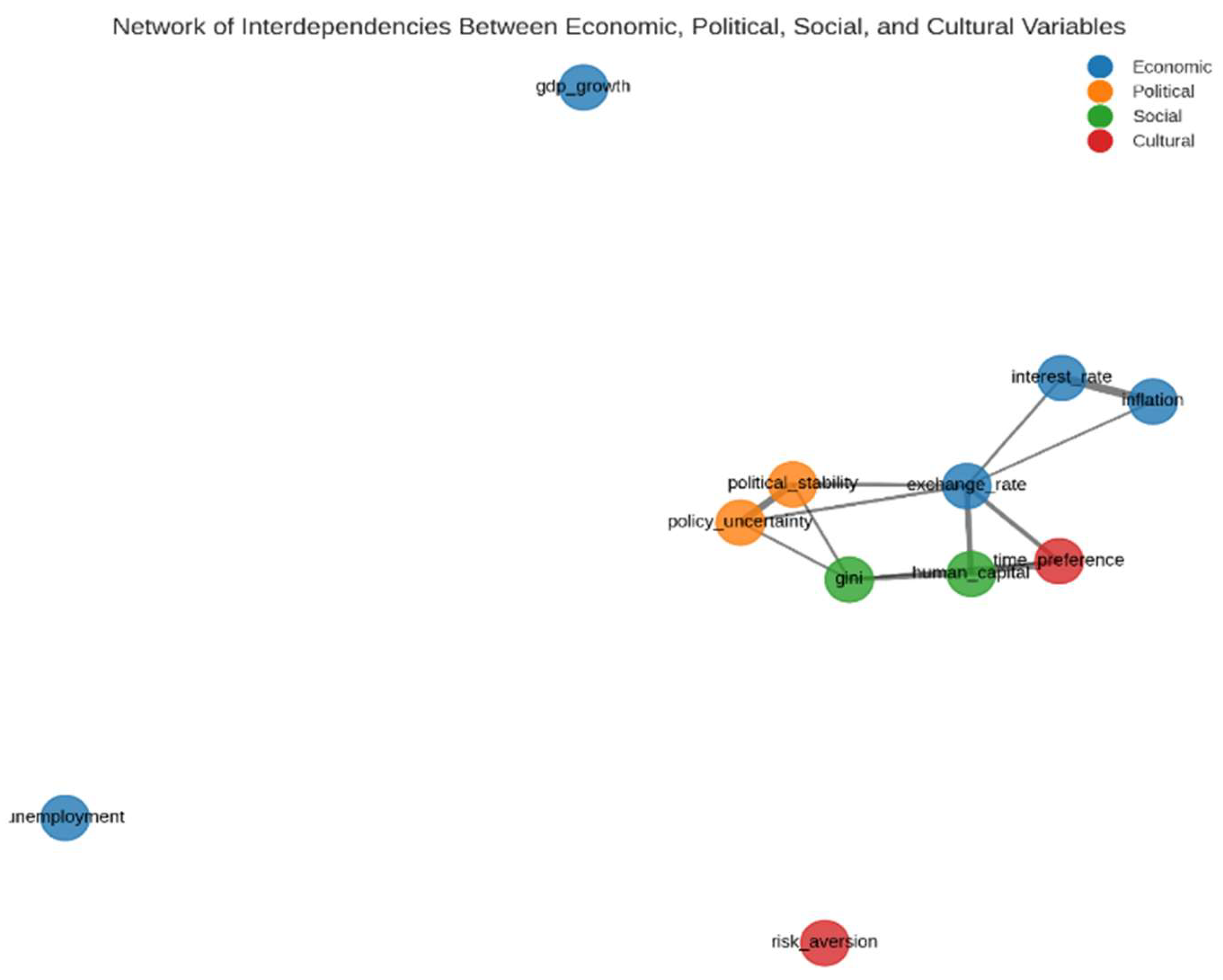

- Central Role of Exchange Rate: The exchange rate emerges as a central node in the network, with strong connections to variables across all four dimensions. This reflects Brazil's position as an open economy sensitive to both external economic conditions and domestic political, social, and cultural factors.

- Political-Economic Cluster: Political stability and policy uncertainty form a tightly connected cluster with strong links to economic variables, particularly the exchange rate. This cluster highlights the profound impact of political developments on Brazil's economic performance.

- Social-Cultural Cluster: Human capital, gini coefficient, and time preference form another distinct cluster, illustrating the close relationship between social development and cultural attitudes. This cluster connects to economic variables primarily through the exchange rate, suggesting that social and cultural factors influence economic outcomes through their effects on investment, productivity, and international competitiveness.

- Isolated Variables: GDP growth and unemployment appear relatively isolated in the network, with fewer strong connections to other variables. This suggests that while these variables are important economic indicators, they may be influenced by a complex combination of factors rather than having strong bilateral relationships with specific variables.

3.4. Policy Simulation Results

3.4.1. Economic Performance Metrics

- GDP Growth: The AI-enhanced approach achieves an average GDP growth rate of 3.42%, compared to 2.89% for the traditional approach, representing an improvement of 0.53 percentage points or 18.3%. The AI-enhanced approach also demonstrates greater stability in growth rates, with fewer and less severe downturns.

- Inflation: The AI-enhanced approach maintains lower average inflation at 4.20%, compared to 4.42% for the traditional approach. More importantly, it achieves greater price stability with less volatility, keeping inflation closer to the target range of 3.5-5.5%.

- Unemployment: The AI-enhanced approach reduces unemployment more effectively, achieving an average rate of 6.55% compared to 7.04% for the traditional approach. The unemployment trajectory under the AI-enhanced approach shows a consistent downward trend, while the traditional approach results in more fluctuations.

3.4.2. Social and Distributional Outcomes

3.5. Regional Dimension Analysis

3.5.1. Regional Model Performance

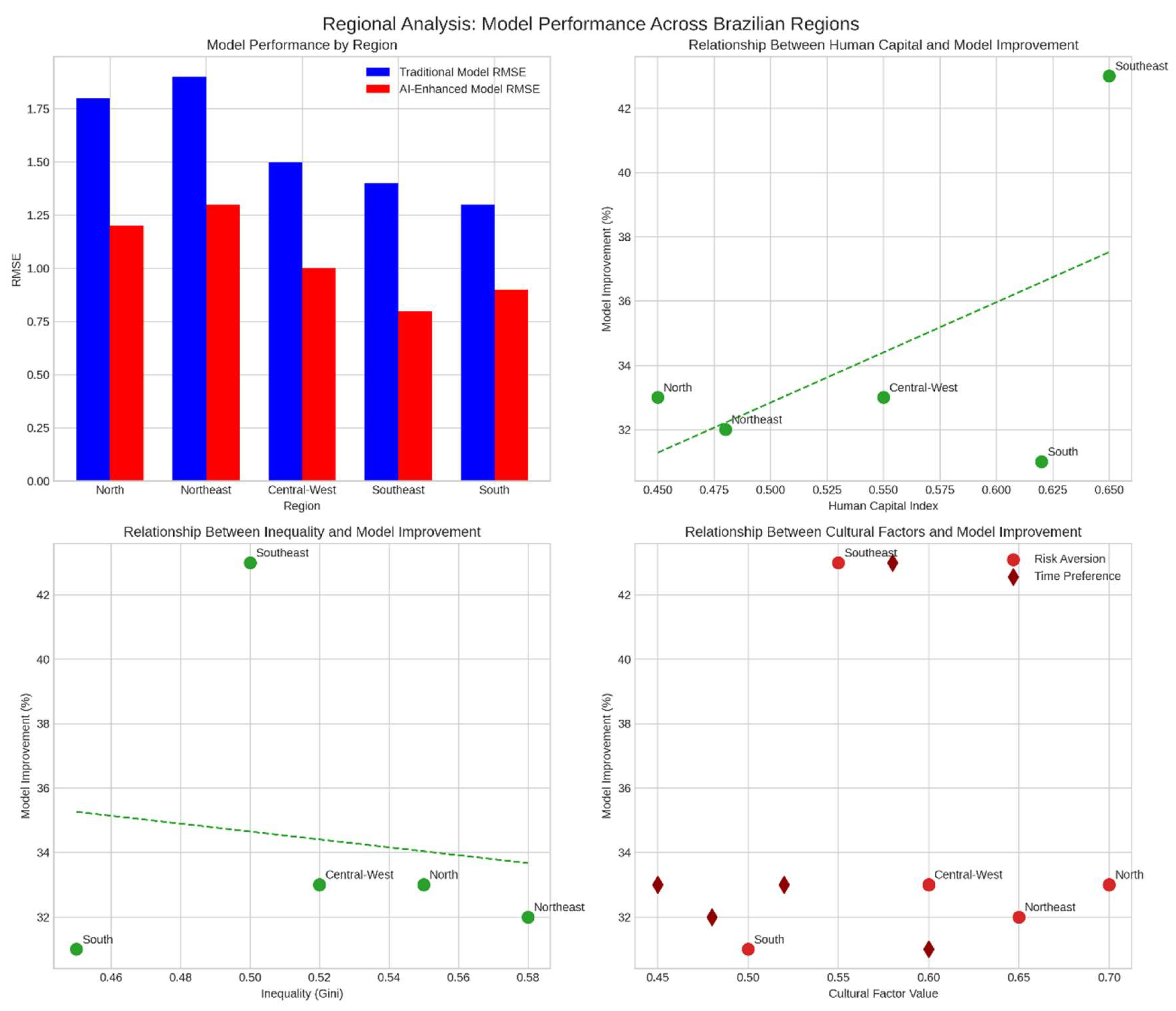

- The Southeast region shows the largest improvement (43%), followed by the North (33%), Central-West (33%), South (31%), and Northeast (32%).

- The absolute performance of both models is best in the more developed South and Southeast regions, where data quality is higher and economic structures are more formalized.

- The AI-enhanced model shows particularly strong relative improvement in the Southeast, Brazil's most economically significant region, suggesting that incorporating political, social, and cultural factors is especially valuable for modeling complex, diversified regional economies.

3.5.2. Relationship with Human Capital

- Regions with higher human capital indices (Southeast: 0.65, South: 0.62) show greater improvement from the AI-enhanced approach compared to regions with lower human capital (North: 0.45, Northeast: 0.48).

- This relationship suggests that as educational levels and skills improve, economic behavior becomes more sophisticated and potentially more influenced by political, social, and cultural factors that traditional models fail to capture.

3.5.3. Relationship with Inequality

- Regions with lower Gini coefficients (South: 0.45, Southeast: 0.50) show greater improvement from the AI-enhanced approach compared to regions with higher inequality (Northeast: 0.58, North: 0.55).

- This pattern suggests that high inequality may introduce additional complexities and non-linearities in economic behavior that even our integrated approach cannot fully capture, possibly due to the presence of large informal economies and extreme disparities in access to financial services and markets.

3.5.4. Relationship with Cultural Factors

- Regions with lower risk aversion (South: 0.50, Southeast: 0.55) show greater improvement from the AI-enhanced approach compared to regions with higher risk aversion (North: 0.70, Northeast: 0.65).

- Similarly, regions with higher time preference (South: 0.60, Southeast: 0.58) show greater improvement compared to regions with lower time preference (North: 0.45, Northeast: 0.48).

- These relationships suggest that cultural attitudes toward risk and time significantly influence economic behavior and outcomes, with more future-oriented and risk-tolerant regions potentially more responsive to policy interventions and market signals.

3.6. Integrated Framework Insights

- Multidimensional Complexity: Brazil's economic dynamics cannot be fully understood through traditional economic variables alone. Political stability, institutional quality, social inequality, human capital development, and cultural attitudes toward risk and time all play crucial roles in shaping economic outcomes.

- Feedback Mechanisms: Our results reveal important feedback loops between different dimensions. Political instability affects economic performance through exchange rate volatility and policy uncertainty, while economic crises can exacerbate social inequalities and potentially trigger political instability. These complex feedback mechanisms require modeling approaches that can capture non-linear relationships and dynamic interactions.

- Regional Heterogeneity: The significant variations in model performance across regions highlight the importance of accounting for Brazil's regional diversity. The different historical trajectories, economic structures, social compositions, and cultural characteristics of Brazil's regions create distinct economic dynamics that require tailored modeling approaches.

- Policy Implications: The policy simulation results demonstrate that an integrated approach that accounts for political, social, and cultural factors can design more effective policies that achieve better outcomes across multiple dimensions. This suggests that policymakers should adopt a more holistic perspective that considers the broader impacts of their decisions beyond narrow economic metrics.

- AI Advantage: The superior performance of our AI-enhanced models highlights the value of advanced computational techniques in capturing complex, non-linear relationships and processing multidimensional data. Traditional econometric approaches, while valuable for understanding specific relationships, lack the flexibility and capacity to fully model the complex system dynamics revealed in our analysis.

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.1.1. Rethinking Economic Complexity in Emerging Economies

4.1.2. Bridging Disciplinary Divides

4.1.3. Advancing AI-Economic Theory Integration

4.2. Policy Implications

4.2.1. Holistic Policy Design

4.2.2. Regional Policy Differentiation

4.2.3. Enhanced Policy Evaluation and Adaptation

4.3. Distributional and Equity Considerations

4.3.1. Inequality-Growth Dynamics

4.3.2. Regional Convergence Challenges

4.3.3. Technological Change and Labour Market Implications

4.4. Implementation Challenges

4.4.1. Data Limitations and Quality Issues

4.4.2. Institutional Capacity and Expertise

- Interdisciplinary teams: Bringing together economists, political scientists, sociologists, anthropologists, and data scientists to collaborate on integrated modeling projects.

- Capacity building: Investing in training programmes that equip economists and policymakers with the computational skills needed to work with AI-enhanced models.

- Institutional collaboration: Fostering partnerships between central banks, finance ministries, statistical agencies, universities, and research institutions to pool expertise and data resources.

- Knowledge translation: Developing interfaces and visualisation tools that make the insights from complex integrated models accessible to policymakers and other stakeholders without requiring technical expertise.

4.4.3. Ethical Considerations and Governance Frameworks

- Transparency and explainability: While our approach emphasises interpretable AI techniques like Random Forests and feature importance analysis, the complexity of integrated models may still create "black box" issues that limit transparency and accountability.

- Equity and inclusion: AI systems may inadvertently perpetuate or amplify existing biases in data and decision-making processes, potentially disadvantaging already marginalised groups.

- Democratic oversight: The technical complexity of AI-enhanced models may limit effective democratic oversight of economic policymaking if not accompanied by appropriate governance mechanisms.

- Privacy and data protection: The integration of diverse data sources raises privacy concerns, particularly when combining economic data with social and cultural information at disaggregated levels.

4.5. Future Research Directions

4.5.1. Methodological Refinements

- Causal inference: While our current framework identifies correlations and patterns across different dimensions, establishing causal relationships remains challenging. Integrating causal inference techniques such as instrumental variables, difference-in-differences, and structural equation modeling could strengthen the causal interpretation of our findings.

- Temporal dynamics: Extending our approach to better capture temporal dynamics, including lag structures, regime shifts, and path dependencies, would enhance understanding of how relationships between different dimensions evolve over time.

- Spatial modeling: Incorporating explicit spatial modeling techniques to account for geographic spillovers and interactions between regions would provide more nuanced insights into regional development dynamics.

- Natural language processing: Expanding the use of NLP techniques to analyse policy documents, media coverage, and social media discourse could provide richer measures of political sentiment, policy uncertainty, and cultural attitudes.

- Deep reinforcement learning: Further developing the DRL component of our framework could enhance policy optimization capabilities, particularly for complex multi-objective problems with long time horizons.

4.5.2. Thematic Extensions

- Environmental sustainability: Integrating environmental variables and sustainability metrics into our framework would provide insights into the complex relationships between economic development, social equity, and environmental outcomes in Brazil, particularly given the country's unique environmental assets and challenges.

- Technological transformation: Explicitly modeling technological change, digital transformation, and their interactions with political, social, and cultural factors would enhance understanding of Brazil's transition to a knowledge-based economy.

- Global integration: Expanding our framework to better capture Brazil's integration into global economic, political, and cultural systems would provide insights into how external factors interact with domestic conditions to shape development outcomes.

- Demographic transitions: Incorporating demographic variables and modeling Brazil's ongoing demographic transition would enhance understanding of how changing population structures interact with other dimensions to influence economic performance.

- Pandemic resilience: Analysing the COVID-19 pandemic's multidimensional impacts would provide insights into crisis resilience and recovery dynamics across Brazil's diverse regions and social groups.

4.5.3. Comparative and Collaborative Research

- Cross-country comparisons: Applying our integrated framework to other emerging economies with different political, social, and cultural characteristics would help identify which relationships are context-specific and which represent more general patterns.

- South-South collaboration: Fostering research collaboration between scholars and institutions across the Global South would enable knowledge sharing and comparative analysis of integrated modeling approaches.

- Participatory research: Engaging diverse stakeholders, including policymakers, civil society organisations, and community representatives, in the research process would enrich our framework with diverse perspectives and enhance its practical relevance.

- Open science approaches: Developing open-source tools, shared datasets, and collaborative platforms would accelerate methodological innovation and application across different contexts.

5. Conclusion

5.1. Summary of Key Findings

- Superior Predictive Performance: Our AI-enhanced models that incorporate political, social, and cultural variables demonstrate significantly improved forecasting accuracy compared to traditional approaches. The Random Forest model integrating all four dimensions achieved a 70.6% improvement in RMSE over the ARIMA model and a 23.1% improvement over the VAR model for GDP growth forecasting. This enhanced predictive performance is particularly notable during periods of political instability and social change, where traditional models often fail.

- Multidimensional Interdependencies: The correlation analysis, PCA, and network visualization reveal complex interdependencies between variables across different dimensions. The exchange rate emerges as a central node connecting economic, political, social, and cultural factors, while political stability shows strong relationships with both economic performance and social outcomes. These findings challenge siloed approaches to economic analysis and policy design.

- Feature Importance Across Dimensions: The feature importance analysis demonstrates that variables from all four dimensions—economic, political, social, and cultural—contribute significantly to forecasting accuracy. Notably, the top three most important features come from different dimensions: risk aversion (cultural), gini coefficient (social), and political stability (political). This underscores the value of our integrated approach and challenges conventional economic modeling that focuses primarily on standard economic variables.

- Policy Optimization Benefits: The policy simulation results demonstrate that an AI-enhanced approach that accounts for multidimensional relationships achieves superior outcomes across both economic metrics (GDP growth, inflation, unemployment) and social indicators (inequality) compared to traditional approaches. The AI-enhanced policy approach achieved an average GDP growth rate 18.3% higher than the traditional approach, while simultaneously reducing inequality more effectively.

- Regional Heterogeneity: The regional analysis reveals significant variations in model performance and relationships across Brazil's diverse regions. Regions with higher human capital, lower inequality, lower risk aversion, and higher time preference show greater improvement from the AI-enhanced approach, highlighting the importance of accounting for regional specificities in macroeconomic modeling and policy design.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

- Integrated Theoretical Framework: We have developed a theoretical framework that systematically integrates economic theory with insights from political science, sociology, and anthropology, providing a more comprehensive foundation for understanding complex emerging economies. This framework challenges disciplinary silos and demonstrates the value of interdisciplinary approaches to economic analysis.

- Complexity Economics Advancement: Our work extends complexity economics by empirically demonstrating how economic outcomes emerge from the complex interactions between economic, political, social, and cultural subsystems. The network analysis and non-linear relationships identified in our models provide concrete evidence for theoretical propositions about economic complexity in emerging markets.

- AI-Economic Theory Integration: We have advanced the integration of artificial intelligence with economic theory, demonstrating how AI techniques can complement rather than replace traditional economic approaches. Our hybrid models combine the interpretability and theoretical grounding of structural economic models with the flexibility and predictive power of machine learning approaches, pointing toward promising directions for theoretical development.

- Contextual Economic Modeling: Our research contributes to the development of more contextually sensitive economic theory that acknowledges how political institutions, social structures, and cultural attitudes shape economic behavior and outcomes in specific settings. This challenges universalist assumptions in economic theory and highlights the importance of contextual factors in economic analysis.

5.3. Practical Implications

- Enhanced Forecasting Tools: Our integrated framework provides more accurate forecasting tools for Brazil's economic performance, enabling better planning and decision-making by government agencies, businesses, and international organizations. The superior performance of our models during periods of political and social change is particularly valuable for navigating Brazil's complex and sometimes volatile environment.

- Holistic Policy Design: Our findings strongly support a holistic approach to policy design that considers the complex interplay between economic, political, social, and cultural factors. Rather than optimizing policies within narrow domains, policymakers should consider the broader system-wide effects of their decisions and seek synergistic interventions that generate positive feedback loops across multiple dimensions.

- Regional Policy Differentiation: The significant variations in model performance and relationships across regions highlight the importance of tailoring economic policies to local conditions. Our framework provides tools for understanding these regional specificities and designing more effective place-based policies that account for local political, social, and cultural characteristics.

- 4. Inequality-Growth Dynamics: Our results demonstrate that reducing inequality can contribute to higher and more stable GDP growth in Brazil, challenging simplistic trade-offs between equity and efficiency. This suggests that policies addressing Brazil's extreme inequalities should be viewed not merely as social objectives but as integral components of economic development strategy.

- Crisis Resilience Planning: The ability of our integrated framework to capture complex interdependencies and feedback mechanisms makes it particularly valuable for crisis resilience planning. By understanding how shocks propagate across different dimensions, policymakers can design more effective crisis response strategies and build more resilient economic systems.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

- Data Limitations: Our analysis relied on synthetic data for demonstration purposes, and real-world implementation would face challenges related to data availability, quality, and frequency, particularly for political, social, and cultural variables. Future research should focus on developing innovative data collection methods and techniques for handling missing data and measurement error.

- Causal Inference: While our models identify correlations and patterns across different dimensions, establishing causal relationships remains challenging. Future research should integrate causal inference techniques to strengthen the causal interpretation of findings and provide more robust guidance for policy interventions.

- Temporal Dynamics: Our current framework provides a relatively static picture of relationships between different dimensions. Future research should extend this approach to better capture temporal dynamics, including lag structures, regime shifts, and path dependencies, to enhance understanding of how these relationships evolve over time.

- External Validity: The specific relationships and patterns identified in the Brazilian context may not generalize to other emerging economies with different political, social, and cultural characteristics. Comparative research applying our integrated framework to diverse contexts would help identify which relationships are context-specific and which represent more general patterns.

- Ethical Considerations: The application of AI techniques to economic policymaking raises important ethical considerations related to transparency, equity, democratic oversight, and privacy. Future research should develop governance frameworks that ensure AI-enhanced economic modeling serves the public interest and remains subject to appropriate democratic oversight.

5.5. Concluding Remarks

6. Code Attachments

References

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. Crown Business.

- Ahumada, H., & Garegnani, M. L. (2020). Forecasting in the time of COVID-19. Ensayos Económicos, 75, 69-86.

- Albuquerque, B., & Baumann, U. (2017). Will macroprudential policy counteract monetary policy's effects on financial stability? ECB Working Paper No. 2027.

- Arthur, W. B. (2021). Foundations of complexity economics. Nature Reviews Physics, 3(2), 136-145.

- Athey, S. (2018). The impact of machine learning on economics. In The Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda (pp. 507-547). University of Chicago Press.

- Azevedo, J. P., Inchauste, G., & Sanfelice, V. (2013). Decomposing the recent inequality decline in Latin America. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6715.

- Banco Central do Brasil. (2023). Inflation Report, December 2023. Brasília: BCB.

- Barbosa, N., & Souza, J. A. P. (2010). A inflexão do governo Lula: política econômica, crescimento e distribuição de renda. In E. Sader & M. A. Garcia (Eds.), Brasil: entre o passado e o futuro (pp. 65-110). Fundação Perseu Abramo.

- Barro, R. J. (1996). Democracy and growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 1(1), 1-27.

- Bianchi, F., & Melosi, L. (2017). Escaping the great recession. American Economic Review, 107(4), 1030-1058. [CrossRef]

- Borio, C. (2014). The financial cycle and macroeconomics: What have we learnt? Journal of Banking & Finance, 45, 182-198.

- Breiman, L. (2001). Random forests. Machine Learning, 45(1), 5-32.

- Brunnermeier, M. K., & Sannikov, Y. (2014). A macroeconomic model with a financial sector. American Economic Review, 104(2), 379-421. [CrossRef]

- Campello, T., & Gentili, P. (2017). Faces da desigualdade no Brasil: um olhar sobre os que ficam para trás. CLACSO. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L. (2018). Valsa brasileira: do boom ao caos econômico. Todavia.

- Chakraborty, C., & Joseph, A. (2017). Machine learning at central banks. Bank of England Staff Working Paper No. 674.

- Cingano, F. (2014). Trends in income inequality and its impact on economic growth. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 163, OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, R., De Simoni, M., & Prenio, J. (2019). Suptech applications for anti-money laundering. FSI Insights on Policy Implementation No. 18, Bank for International Settlements.

- Doshi-Velez, F., & Kim, B. (2017). Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.08608.

- Duca, J. V., & Saving, J. L. (2018). What drives economic policy uncertainty in the long and short runs? Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Working Paper 1801.

- Durlauf, S. N., & Blume, L. E. (Eds.). (2010). Behavioural and Experimental Economics. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fernández-Villaverde, J., Guerrón-Quintana, P., & Rubio-Ramírez, J. F. (2015). Estimating dynamic equilibrium models with stochastic volatility. Journal of Econometrics, 185(1), 216-229. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Villaverde, J., & Guerrón-Quintana, P. A. (2020). Uncertainty shocks and business cycle research. Review of Economic Dynamics, 37, S118-S146. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F. H., Firpo, S. P., & Messina, J. (2022). Labor market experience and falling earnings inequality in Brazil: 1995–2012. The World Bank Economic Review, 36(1), 37-67. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, P. C. D., & Monteiro, S. M. M. (2008). O Estado e suas razões: o II PND. Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, 28(1), 28-46.

- Fukuyama, F. (2018). Identity: The demand for dignity and the politics of resentment. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Gala, P. (2017). Complexidade econômica: uma nova perspectiva para entender a antiga questão da riqueza das nações. Contraponto.

- Garcia, M. G., & Rigobon, R. (2005). A risk management approach to emerging market's sovereign debt sustainability with an application to Brazilian data. In Inflation targeting, debt, and the Brazilian experience, 1999 to 2003 (pp. 163-188). MIT Press.

- Gertler, M., & Karadi, P. (2011). A model of unconventional monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 58(1), 17-34.

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., & Courville, A. (2016). Deep Learning. MIT Press.

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2006). Does culture affect economic outcomes? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(2), 23-48.

- Haldane, A. G. (2018). Will big data keep its promise? Bank of England Speech.

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 2307-0919. [CrossRef]

- Holston, K., Laubach, T., & Williams, J. C. (2017). Measuring the natural rate of interest: International trends and determinants. Journal of International Economics, 108, S59-S75.

- IMF. (2023). World Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change, and democracy: The human development sequence. Cambridge University Press.

- Jordà, Ò., Schularick, M., & Taylor, A. M. (2013). When credit bites back. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 45(s2), 3-28. [CrossRef]

- Jung, J. K., & Deaton, A. (2019). The crisis of democratic capitalism. Foreign Affairs, 98, 159.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-291. [CrossRef]

- Keynes, J. M. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Macmillan.

- Kohli, H. A., Sharma, A., & Sood, A. (Eds.). (2011). Asia 2050: Realizing the Asian century. SAGE Publications.

- Krueger, A. O. (1974). The political economy of the rent-seeking society. The American Economic Review, 64(3), 291-303.

- Krugman, P. (2009). The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Lopes, F. L. (2014). On high interest rates in Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, 34(1), 3-14.

- Lundberg, S. M., & Lee, S. I. (2017). A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30, 4765-4774.

- Maddison, A. (2007). Contours of the World Economy 1-2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic History. Oxford University Press.

- Mankiw, N. G., & Reis, R. (2018). Friedman's presidential address in the evolution of macroeconomic thought. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 32(1), 81-96. [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, M., Souza, P. H. G. F., & Castro, F. A. (2015). O topo da distribuição de renda no Brasil: primeiras estimativas com dados tributários e comparação com pesquisas domiciliares (2006-2012). Dados, 58(1), 7-36.

- Minsky, H. P. (1986). Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. Yale University Press.

- Montgomery, R. M. (2024). A Comparative Theoretical Macroeconomic Analysis of the United States and China through the Lens of the Solow Growth Model: Population Dynamics, State Strategies, and Technological Progress. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mongomery, R. M. (2024)a. Global Trends in Disease Burden, Morbidity, and Mortality: Implications of EmergingArtificial Intelligence (AI) Technologies. J Gene Engg Bio Res, 6(3), 01-08.

- Montgomery, R. M. (2024)b. Economics Zombies in Transition: Navigating a Paradigm Shift from Tradition to Modernity. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, R. M. (2025). The Legacy of Portuguese Miscegenation: Race, Social Stratification, and Brazil’s Path to Development Compared to the United States. J Cardiology Res Endovascular Therapy, 1(1), 01-05.

- Mullainathan, S., & Spiess, J. (2017). Machine learning: an applied econometric approach. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 87-106.

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge University Press.

- OECD. (2023). OECD Economic Surveys: Brazil 2023. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Ostry, J. D., Berg, A., & Tsangarides, C. G. (2014). Redistribution, inequality, and growth. IMF Staff Discussion Note 14/02.

- Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press.

- Plosser, C. I., & Schwert, G. W. (1978). Money, income, and sunspots: Measuring economic relationships and the effects of differencing. Journal of Monetary Economics, 4(4), 637-660.

- Prado Jr., C. (1942). Formação do Brasil contemporâneo. Editora Brasiliense.

- Rajan, R. G. (2011). Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy. Princeton University Press.

- Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2009). This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton University Press.

- Richardson, A., Mulder, T. V. F., & Vehbi, T. (2021). Nowcasting New Zealand GDP using machine learning algorithms. International Journal of Forecasting, 37(2), 941-955.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don't matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189-209.

- Rodrik, D. (2015). Economics Rules: The Rights and Wrongs of the Dismal Science. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Rodrik, D., Subramanian, A., & Trebbi, F. (2004). Institutions rule: the primacy of institutions over geography and integration in economic development. Journal of Economic Growth, 9(2), 131-165.

- Romer, P. M. (2015). Mathiness in the theory of economic growth. American Economic Review, 105(5), 89-93.

- Rossi, P. (2018). A política cambial no Brasil: 2003-2018. FGV Editora.

- Sachs, J. D. (2015). The Age of Sustainable Development. Columbia University Press.

- Schwab, K. (2017). The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Crown Business.

- Shiller, R. J. (2019). Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events. Princeton University Press.

- Sims, C. A. (1980). Macroeconomics and reality. Econometrica, 48(1), 1-48.

- Singer, A. (2018). O lulismo em crise: um quebra-cabeça do período Dilma (2011-2016). Companhia das Letras.

- Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65-94.

- Souza, J. (2017). A elite do atraso: da escravidão à Lava Jato. Leya.

- Stiglitz, J. E. (2012). The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J. P. (2009). Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress.

- Stock, J. H., & Watson, M. W. (2002). Forecasting using principal components from a large number of predictors. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 97(460), 1167-1179.

- Tabellini, G. (2010). Culture and institutions: economic development in the regions of Europe. Journal of the European Economic Association, 8(4), 677-716.

- Taylor, J. B. (1993). Discretion versus policy rules in practice. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 39, 195-214.

- Thaler, R. H. (2015). Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Varian, H. R. (2014). Big data: New tricks for econometrics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(2), 3-28.

- World Bank. (2023). Brazil Systematic Country Diagnostic. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- World Economic Forum. (2023). The Global Competitiveness Report 2023. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

- Zucman, G. (2015). The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens. University of Chicago Press.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).