1. Introduction

A circular economy approach promotes nutrient recovery from food waste (FW), reducing reliance on mined phosphorus (P) and synthetic nitrogen (N) fertilizers [

1]. Despite the environmental impact of mineral fertilizers, many nutrient-rich waste sources remain underutilized. Integrating bio-based fertilizers into agriculture could enhance soil quality and support sustainable food production [

2,

3,

4,

5].

The disposal of FW without recycling leads to the loss of valuable nutrients that could otherwise support agricultural productivity. Globally, FW represents approximately one-third of total food production, amounting to 1.3 billion tons annually [

6]. FW’s disposal via landfills and incineration causes severe environmental harm, while recycling focuses on converting FW into valuable chemicals and bioenergy [

7,

8]. FW can be converted into biofertilizers through composting and anaerobic digestion (AD). Composting produces nutrient-rich organic matter, while AD generates biogas and nutrient-dense digestate, offering a sustainable alternative to synthetic fertilizers [

9]. Research has explored FW recycling through AD, thermal hydrolysis, and dehydration to create biofertilizers as substitutes for inorganic fertilizers [

4,

5,

10,

11,

12]. Biofertilizers often result from fermenting or composting kitchen waste alongside other organic materials [

13].

Fertilizers significantly influence plant yield (PY), making accurate predictions essential for agricultural planning and food security. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool for prediction in environmental sciences [

14,

15,

16,

17] and, specifically, for optimizing crop yields based on fertilizer use [

18,

19,

20]. For example, X. Li et al. [

18] analyzed 35 years of fertilizer application and grain yield data in China, finding that backpropagation neural networks (BPNN) outperformed other ML models with an RMSE below 0.12 and R

2 > 0.80. Wang et al. [

19] optimized planting density and fertilizer rates using BPNN and regression methods. Thai et al. [

21] applied analysis of variance, linear mixed-effects models, and regression trees to evaluate winter wheat yields under different fertilizer practices. Similarly, L. Meng et al. [

20] demonstrated that Random Forest (RF) and adaptive boosting significantly improved yield predictions (R

2 = 0.85−0.98).

In addition to PY, the fertilizer value of FW after various treatments was assessed using internal efficiency of nitrogen utilization (IENU). IENU evaluates how efficiently crops use nitrogen for growth, measuring sustainability and optimization in crop production [

22,

23]. PY represents the agricultural output harvested per unit area, making it a widely used metric for assessing fertilizer impact on crop performance. Both metrics are crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of FW-based fertilizers and FW mitigation programs. However, while PY is frequently applied in such assessments, IENU has received limited attention in practical applications. No studies have employed ML models to predict FW-driven crop yields using PY and IENU metrics.

The study aims to achieve three key objectives: first, to develop a comprehensive dataset of fertilizers derived from FW; second, to identify and analyze crop yield data influenced by FW-based fertilizers; and third, to estimate the agronomic effectiveness of these fertilizers using statistical and ML models, particularly through PY and IENU. By addressing these objectives, the research aims to enhance the understanding of how FW-driven fertilizers influence crop productivity and nutrient utilization efficiency, ultimately providing valuable insights to improve waste recycling efforts and optimize agricultural practices

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiments About Kitchen Waste Recycling as Fertilizer for Plant Growth

2.1.1. In-House Experimental Procedures

The data for our experiments includes 102 cases from our research, published in previous studies [

13], and an additional 159 unpublished cases. The experimental methods for these data were based on the following methodology.

The preparation of the final fertilizer began with creating a model waste mixture composed of 100 g each of banana, tomato, lettuce, fruit juice, bun, and apple, along with 200 g each of flowers and paper. The ingredients were pre-cut with a knife and ground twice using a meat grinder to form a homogeneous paste. The model waste paste exhibited a total solids (TS) content of 54% and a volatile solids (VS) content of 90% (based on TS).

Various pre-treatment methods were applied before fertilizer production, involving combinations of microbial inoculation, natural decay, sterilization, and fermentation:

In the first scenario, effective microorganisms (EM) were added directly to the model waste.

In the second scenario, the waste was left to decay for 12 days before a double dose of EM was introduced.

In the third and fourth scenarios, the waste was sterilized after 12 days; however, only the third scenario included EM addition.

In the final scenario, the waste was allowed to decay and was sterilized but not inoculated with EM.

After pre-treatment, the waste was pre-dried, pelletized, and dried to produce the final fertilizer.

2.1.2. External Investigations

To supplement our experimental data, we extracted and standardized information from 20 additional published studies (

Table 1). Together, these datasets formed the comprehensive database for modeling purposes.

Table 1 summarizes key variables across the studies, including treatment types, seasons, growth durations, and plant species. Treatments involved various composting and digestion processes applied to crops such as ryegrass, lettuce, oat, winter wheat, corn, Kai choy, and barley. Growth periods ranged from 0.5 to 180 months, covering both warm and cold seasons. Some studies also evaluated combinations of FW, garden waste, and municipal solid waste for their effects on plant growth and productivity.

2.2. Dataset Preparation and Processing

The initial dataset consisted of 448 instances with seven features: nitrogen content (NC), volatile solids (VS), season, growth time (T), plant type, fertilizer dose (D), plant yield (PY), and input efficiency of nitrogen use (IENU). Due to a high proportion of missing values (45.5%), the VS variable was excluded from further analysis.

After removing missing target values, 420 instances remained for PY prediction and 342 for IENU prediction. While PY prediction utilized data from all 20 studies, IENU prediction excluded three studies [

28,

29,

36].

The study focused on two output parameters:

PY: Represented in kilograms of total solids per hectare (kg/ha), PY reflects the agricultural output per unit area.

IENU: Measured in kilograms of nitrogen per hectare (kg N/ha), IENU evaluates the effectiveness of nitrogen use in supporting crop growth.

Three explanatory features were analyzed:

NC: The nitrogen percentage in fertilizer affects crop growth and nitrogen efficiency.

T: The crop growth duration (in days) influences nutrient uptake and development.

D: The fertilizer amount applied per hectare impacts yield outcomes.

The data contain several missing and outlier values handled using different methods. Four versions of the dataset were created. The first version, Data 1, was created by discarding any records with missing values. Data 2 was then derived from Data 1 by eliminating outliers using the boxplot method. The third version, Data 3, was generated by imputing missing values to maintain the dataset’s integrity. Finally, Data 4 was produced by removing outliers from Data 3, similar to the procedure used to create Data 2, ensuring the dataset’s quality for further examination. These processed datasets were each randomly divided, allocating 80% of the cases to a training set and the remaining 20% to a testing set. The normalized, log, standardized transformation methods were deployed to test the change in error of prediction models.

2.3. Machine Learning Modeling Approach

This study utilized four ML models to predict PY and IENU: Gradient Boosting (GB), Cubist (CB), RF, and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB). These models were chosen to leverage their collective strengths in handling the diverse and complex data necessary for accurately predicting PY. They have been widely utilized in the prediction of agricultural production, demonstrating their effectiveness and reliability.

GB is a method ML that addresses regression and classification challenges by creating an ensemble of weak models, typically decision trees. The approach incrementally builds the model by optimizing a differentiable loss function at each step [

42]. GB has been reported as an effective model for predicting corn yields [

43].

CB is a regression-based predictive model incorporating nearest-neighbor corrections to enhance its predictions [

44,

45]. It constructs decision trees where the terminal leaves define rule-based “if-then” conditions. Each rule in the Cubist algorithm corresponds to a multiple linear regression model, improving predictive accuracy. CB has two key parameters that can be either default or fine-tuned: (1)

committees, which determine the number of boosting iterations, and (2)

neighbors, which specify the number of instances used to adjust rule-based predictions [

46,

47].

XGB is an optimized and scalable implementation of Gradient Boosting. It is specifically designed to improve performance and computational efficiency. It implements ML algorithms under the Gradient Boosting framework and is renowned for its performance and speed [

48]. XGB includes L1 and L2 regularization to prevent overfitting. In agriculture, XGB has been successfully applied to yield prediction, demonstrating high accuracy and the ability to model complex relationships in crop data [

49]. Studies have shown that XGB performs comparably to, or even outperforms, deep learning models when predicting yields using remote sensing data [

50]. Additionally, XGB has explicitly been utilized to predict PY in agricultural research [

51].

RF is an ensemble learning technique that generates multiple decision trees during training. For classification tasks, it predicts the mode of the classes, and for regression tasks, it calculates the mean prediction from all the individual trees. By averaging the outcomes of several trees, it mitigates overfitting and enhances generalization (Breiman, 2001). RF has been widely used for crop prediction due to its ability to handle large datasets with many features and its resistance to overfitting [

52].

2.4. Evaluation metrics

In addition to ML models, linear regression (LR) models were employed for comparison. A variety of metrics were employed to assess the performance of these models. R² (Coefficient of Determination) and RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) were used for ML models. R² quantifies the proportion of the variance in the response variable that the independent features can explain. RMSE evaluates the square root of the average of the squared differences between observed and predicted values, reflecting the model’s prediction accuracy. R², RSE (Residual Standard Error), RMSE, and AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) were used for LR models. RSE assesses the standard deviation of the residuals, indicating the typical size of the errors. AIC measures the relative quality of statistical models, balancing model complexity and goodness of fit. Combining these metrics mitigates individual disadvantages and sensitivities, enhancing evaluation efficiency [

15]. These metrics are presented in Equations 1 – 4 [

53,

54,

55].

where:

yi is the observed value;

is the predicted value;

N is the number of observations;

p is the number of predictors (independent variables);

k is the number of parameters in the model;

is the maximum value of the likelihood function for the model.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Exploratory Data Analysis

Table 2 encompasses six variables, each representing different aspects of agricultural research. The targets, PY and IENU, exhibit high variability with coefficients of variation (CV) of 136.61% and 286.76%, respectively. PY, with a mean of 2268.42 kg TS/ha and a range up to 18008.11 kg TS/ha , and IENU, averaging 32.26 kg N/ha with a range extending to 1285.71 kg N/ha , underscore the broad spectrum of outcomes in agricultural productivity and efficiency. Predictor variables NC, T, and D also show significant variability.

Table 3 outlines the frequency of various crops studied for growth using kitchen waste as fertilizer, reflecting multiple agricultural interests. Ryegrass dominates the dataset with a substantial frequency of 73.77%. “Grass” (unspecified species) accounted for 10.76%, while oats and lettuce followed with frequencies of 4.87% and 2.02%, respectively. Other crops, including barley, corn, and specific varieties of potato and rice, were less frequently represented (<2%), indicating a narrower research focus on these species.

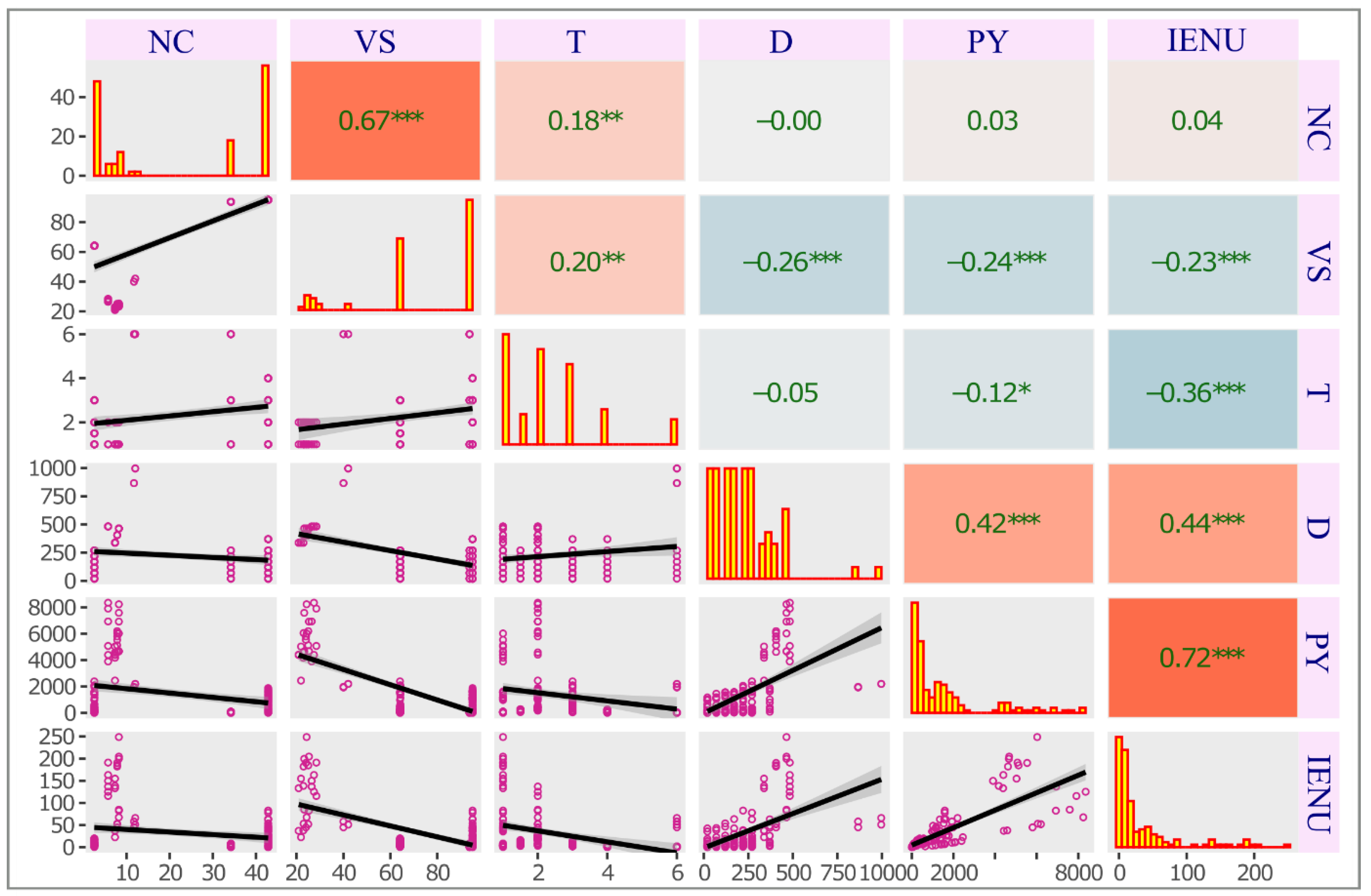

The correlation analysis was conducted using all available data. Given the non-normal distribution of the data and the presence of a significant number of ties, Kendall’s Tau was employed. Kendall’s Tau is less influenced by outliers, making it suitable for this dataset. For datasets with numerous ties, Kendall’s Tau-b provides a refined correlation measure by adequately accounting for these ties in its calculation. Examining the correlations between targets and predictors, D demonstrated positive, significant correlations with PY and IENU, with r-values of 0.42 and 0.44, respectively (P < 0.01) (

Figure 1). In contrast, VS and T had negative correlations with PY and IENU, with r-values around -0.24 (P < 0.01). NC showed no significant correlation with the targets. The absence of strong correlations among predictors indicates their independence, deeming them appropriate for PY and IENU prediction.

3.2. Prediction of Plant Yield

The initial dataset comprises 420 rows and includes four variables: NC, T, D, and PY. Following this omission, the dataset underwent several transformations, yielding four distinct versions tailored for detailed comparative studies. These versions are denoted as Data 1 (382 cases), Data 2 (324 cases), Data 3 (324 cases), and Data 4 (299 cases). These processed datasets were each randomly divided, allocating 80% of the cases to a training set and the remaining 20% to a testing set. To ensure consistent distributions of the target variable, mitigate data leakage, identify biases, and promote model generalization, the practice of checking the distributions of training and test data in ML prediction was implemented. The histograms illustrate the “PY” frequency distributions across four datasets, revealing right-skewed patterns in all training sets. Notably, Data 2 is the most promising for predictive modeling due to its training and test set distributions aligning more closely (Fig. S1).

3.2.1. Linear Regression

LR models applied to the four datasets produced R² values ranging from 0.18 to 0.41 (

Table 4), indicating modest explanatory power. Data 2 and 4, in particular, exhibited lower AIC values, suggesting a more suitable balance between fit and complexity than those for Data 1 and 3. However, introducing RMSE provides additional insight into the model’s predictive performance, with Data 2 and 4 showing lower errors, thus reinforcing their efficacy.

Despite the moderate explanatory power demonstrated by all models, the consistency in results between the transformed and untransformed predictors for Data 2 underscores the model’s robustness (lowest RSE, AIC, and RMSE). This aspect is particularly noteworthy as it highlights the model’s capability to effectively capture the underlying relationship between the predictors and PY, regardless of the scale or distribution of the predictor variables. However, the model’s explanatory power is limited, as the three variables collectively explain only 24% of the variation in the data. Analysis of the coefficients reveals that T has the most substantial impact on PY (62.42), followed by NC (-8.05), and then D (2.05).

The diminished predictive capacity of LR underscores the need for advanced modeling techniques to more accurately estimate PY in the context of highly variable crop yield data influenced by numerous factors [

56,

57]. LR typically yields modest results in such scenarios [

58]. Moreover, the inherent variability in crop yield, characterized by its specificity to each period and its intrinsic nonlinearity, further complicates prediction [

59].

3.2.2. Machine Learning

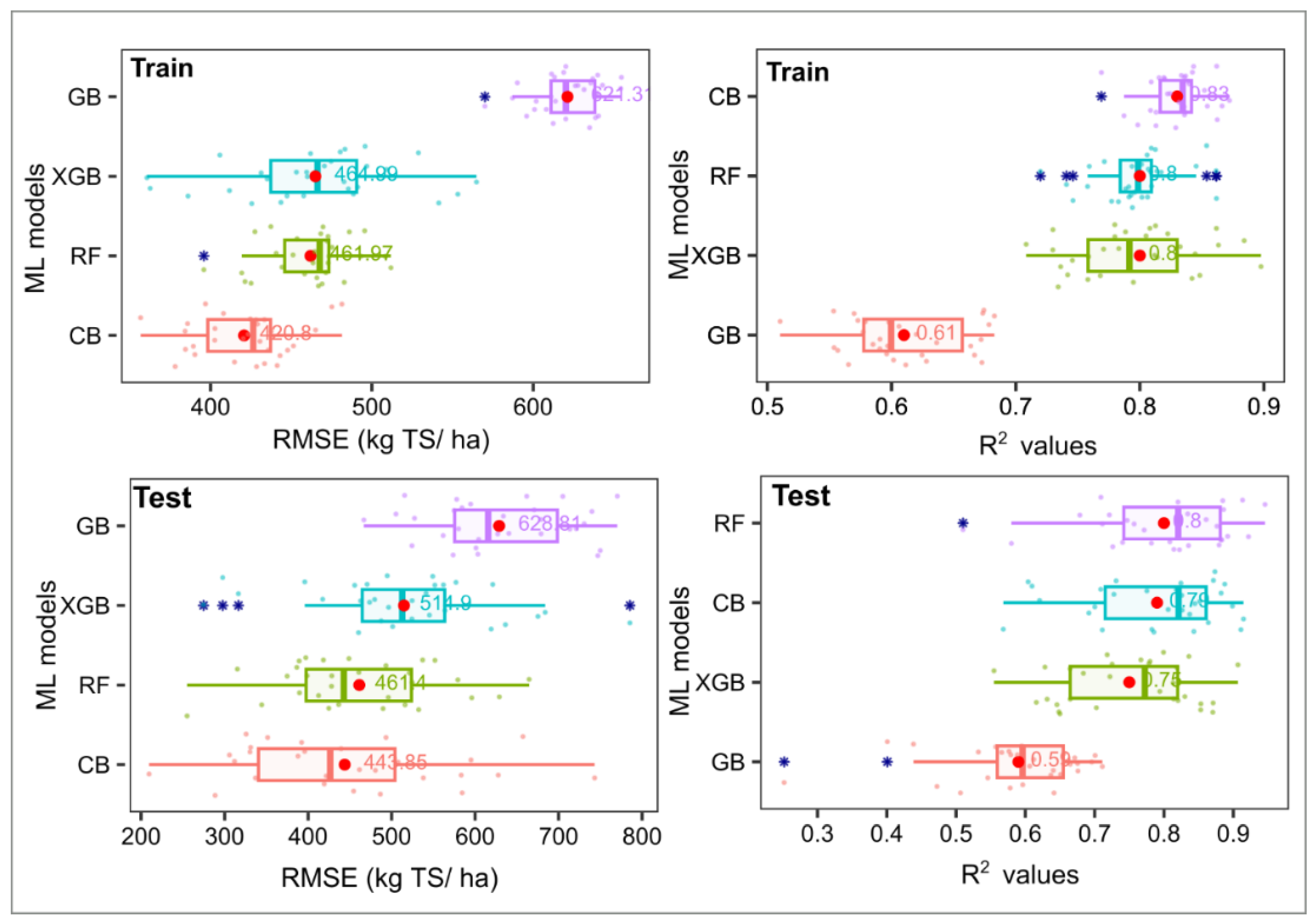

Initially, ML algorithms, including CB, XGB, RF, and GB, were employed to identify the most suitable dataset for PY prediction. Subsequent analysis revealed significant disparities among the four datasets (

Table 5). Data 2 consistently outperformed others, with the RF model yielding the lowest RMSE (493.22) and the highest R

2 (0.77). Therefore, Data 2 emerges as the optimal choice for subsequent prediction tasks.

To enhance the rigor of our analysis of Data 2, four ML models were trained using 80% of the data and the remaining 20% for testing. However, due to the random nature of the split, each 80/20 split varied, leading to inconsistent model performance outcomes. To mitigate this variability, 30 separate runs of the train/test splits were conducted, and the results were reported as the mean of these runs. This methodology aligns with the approach used by [

60], who applied a similar strategy in their study using RF to predict soybean yield; however, they also included multiple repetitions to optimize hyperparameters. Each run involved training and tuning the ML models using 10-fold cross-validation and normalization transformations (

Table S1). The RF and Cubist models exhibited superior generalization capabilities, with low RMSE and high R

2 values (0.79–0.83 in training and testing), demonstrating robustness in handling unseen data.

In contrast, XGB and GB models, despite their competitive performance during training, showed signs of slight overfitting, as evidenced by an increase in RMSE from training to testing phases. This indicates that while these models effectively capture complex patterns in training data, they may require careful tuning to enhance generalizability. Notably, the RF model consistently performed well, effectively capturing nuances in the training data while maintaining robust accuracy during testing, achieving a balanced trade-off between fitting and generalization.

The CB and RF models effectively predicted PY, with optimal parameters identified as committees 50 and neighbors 01 for CB, and ntree 100 and mtry 02 for RF. Previous research has employed various techniques and predictors in ML models for estimating PY, including cross-sectional and time-series predictions and predictors based on remote sensing and ground truth data (experimental plot-based designs) [

60,

61]. These diverse approaches have led to inconsistent findings and varying performance levels in ML models for PY prediction. For example, RF and Support Vector Machine models showed similar efficacy, capturing between 50% and 70% of the spatial and temporal variance in yields for crops such as silage maize, winter barley, winter rapeseed, and winter wheat [

62]. Furthermore, deep learning and RF models demonstrated strong performance at the field level for large-scale crop yield estimation, achieving mean R² values of 0.71 and 0.66 and RMSE values of 1127 kg/ha and 956 kg/ha, respectively [

63]. The RF model, in particular, presented promising results in wheat yield prediction, with an RMSE of 434, normalized RMSE of 0.149 grams per plot, and an R² of 0.74 [

64]

3.3. Prediction of IENU

The initial dataset contains 341 entries with four variables: NC, T, D, and PY. It was transformed into four distinct versions to facilitate comparative analysis: Data 1 (302 entries), Data 2 (256 entries), Data 3 (341 entries), and Data 4 (286 entries). Histograms demonstrated the distribution quality within these datasets (Fig. S2). Notably, Data 2 and Data 4 were identified as the most suitable for predictive modeling due to the close alignment between their training and testing distributions. The removal of outliers rendered the data more effective for predicting IENU.

3.3.1. Linear Regression

Data 2 exhibited the lowest testing RMSE (8.29), suggesting accurate predictions, and a comparatively low training RSE (6.864), indicating a robust model fit. Data 4, with a testing RMSE of 7.82, outperformed Data 2 in testing accuracy but has a slightly higher training RSE of 8.073, though still below Data 3’s. Conversely, Data 1 showed the poorest performance, with the highest testing RMSE (66.86) and training RSE (90.78), indicating the least accurate predictions and model fit. Data 3, despite the highest R2 value during testing, also had high testing RMSE (45.96) and training RSE (98.55), reflecting lower accuracy and fit.

Overall, Data 2 was the top performer, effectively balancing prediction accuracy and model fit, while Data 4 served as a viable alternative, although its low R

2 value indicates sensitivity in this metric. Despite the moderate explanatory power demonstrated by all models, the model’s explanatory power is limited, as the three variables collectively explain only 27 % of the variation in the data. In contrast, a multiple LR study by [

65] accounted for 74% of the variation in nitrogen use efficiency. Analysis of the coefficients reveals that T had the most substantial impact on IENU (2.96), followed by NC (0.12), and then D (0.03).

3.3.2. Machine Learning

The analysis demonstrates that Data 2 consistently outperformed other datasets across various regression models, yielding the lowest RMSE values and the highest R

2 scores (

Table 4). For instance, Data 2 exhibited an average RMSE of approximately 3.91 and an average R

2 of around 0.81, indicating superior predictive accuracy compared to other datasets. Conversely, Data 3 and 4 presented higher RMSE values ( 55.06 and 4.47, respectively) and lower R

2 scores (0.74 and 0.72, respectively), suggesting greater complexity or noise in these datasets. Therefore, based on these findings, Data 2 was the most favorable for regression modeling tasks.

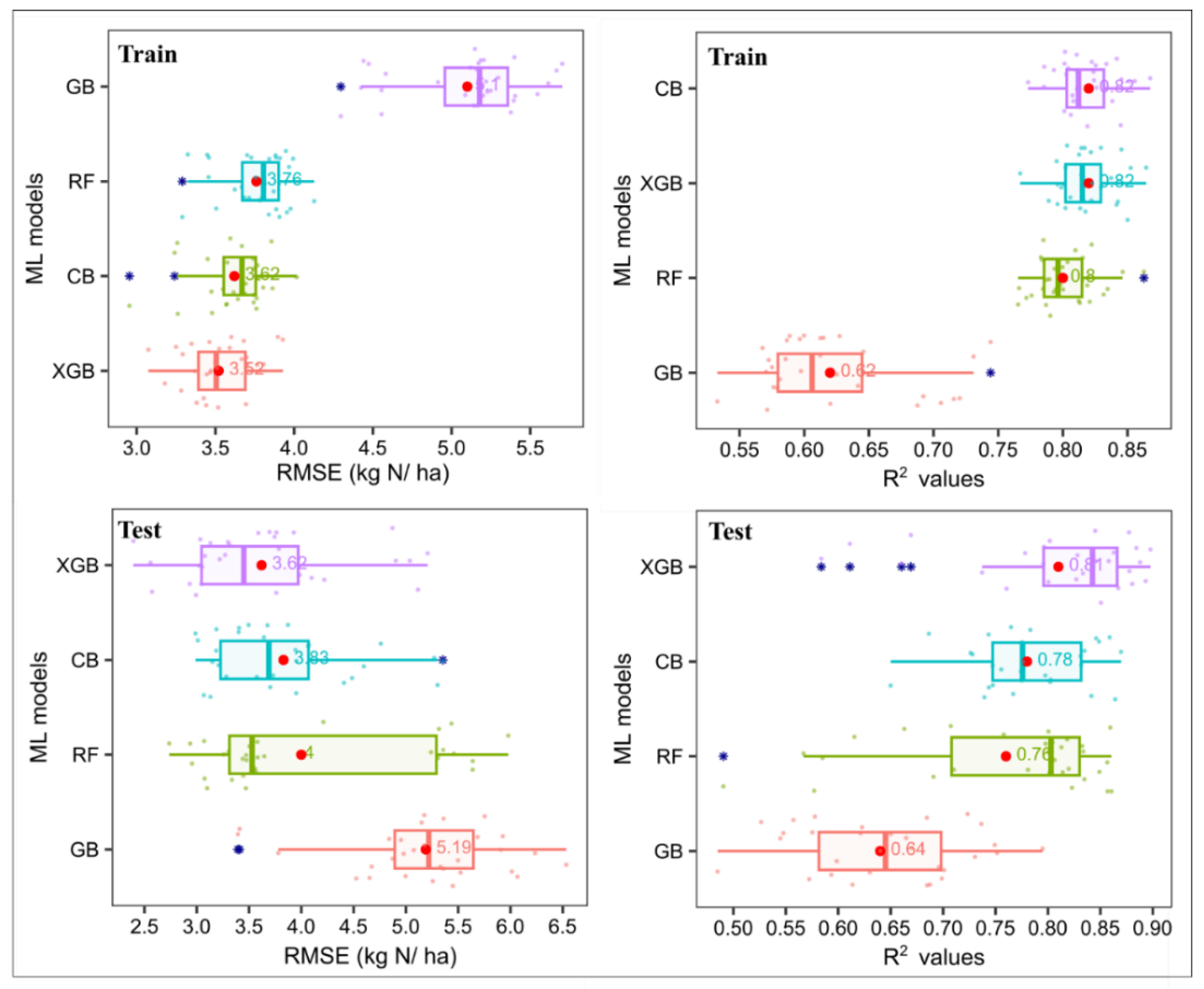

The ML models were assessed based on their performance metrics, including the mean RMSE and R

2, along with their respective standard deviations, for both the training and testing datasets (

Figure 2). CB demonstrated the lowest mean RMSE on the training data at 3.62 ± 0.22, indicating its ability to make accurate predictions while maintaining consistency across iterations. Regarding R

2 on the training data, both XGB and CB achieved high mean values of 0.82, suggesting their effectiveness in explaining the variance in the training data. On the testing dataset, XGB maintained its strong performance with a mean RMSE of 3.62 and a mean R

2 of 0.81, indicating its capability to generalize well to unseen data. CB also performed well on the testing dataset with a mean RMSE of 3.83 and a mean R

2 of 0.78. These results suggest that both XGB and CB exhibited promising performance in capturing the underlying patterns in the training data and making accurate predictions on new, unseen data. RF and GB models also demonstrated competitive performance, with mean RMSE values of 3.76 and 5.10, respectively, and mean R

2 values of 0.80 and 0.62, respectively, on the training dataset. However, their performance slightly decreased on the testing dataset, indicating potential overfitting or a lack of generalization ability compared to XGB and CB. While no studies have targeted predicting IENU precisely, several researchers have focused on nitrogen use efficiency [

66,

67,

68]. However, the metrics used in these studies are not directly comparable to those needed in this context. The results presented here build on the study by [

13], which applied only the Monod model to predict plant dry matter yield (kg d.m./ha) at each harvest based on plant nitrogen (N) utilization data (kg N/ha). The model, fitted to all available data, showed a strong overall fit, suggesting that nitrogen effectively drives yield dynamics. However, since Monod was applied to the entire dataset without independent validation, there is a risk of overfitting. As a result, its predictive accuracy for new, unseen inputs remains uncertain and may lead to incorrect estimations under different conditions.

4. Limitations and Practical Applications

4.1. Limitations

This research, while innovative, confronts several limitations that future studies need to address. Firstly, the data variability and completeness issues stem from the datasets primarily from controlled experiments, which may not capture the full variability and complexities of real-world agricultural settings. Additionally, the high rate of missing data and the exclusion of certain variables could impact the robustness and generalizability of the findings. Secondly, the ML models, despite showing promising results, carry a potential risk of overfitting, particularly noted in models like XGB and Gradient Boosting when applied to unseen data. Enhancing the models’ generalization capabilities to various agricultural environments remains critical for future research. Thirdly, the experiments were conducted on a relatively small scale, and scaling these findings to more extensive commercial agricultural operations could introduce new challenges, such as logistical, economic, and climatic variations that were not accounted for in this study. Lastly, the effectiveness of FW-derived fertilizers is heavily dependent on the specific pre-treatment processes used, and different treatments may yield varying effectiveness across different soil types and crop species, which this study did not fully explore.

4.2. Practical Applications

Despite the limitations above, this study offers valuable insights with significant practical applications. It supports the shift towards more sustainable agricultural practices by demonstrating the effectiveness of FW-derived fertilizers, encouraging recycled organic waste, reducing reliance on chemical fertilizers, and minimizing environmental impact. The findings can help inform policymakers in developing guidelines and regulations that promote organic waste recycling into valuable agricultural inputs, encouraging circular economy practices in the farming sector [

69].

Furthermore, the application of ML models in predicting the outcomes of different fertilizer treatments can aid farmers and agricultural practitioners in optimizing the use of resources. This optimization leads to better crop yields and more efficient use of nitrogen, enhancing food security and sustainability. ML has recently been gradually used to develop decision support tools for modern agricultural systems, covering nutrient management to improve yields while reducing expenses and environmental impact [

61]. It can provide cost-effective and thorough nutrient assessment and decision-making solutions [

70,

71].

Additionally, integrating ML into agricultural practices offers an excellent opportunity for educational programs to teach new technologies in agronomy, fostering a new generation of tech-savvy farmers and researchers. Lastly, there is potential for commercializing the FW treatment processes and the related ML prediction models developed in this study. These can be offered to agricultural businesses as part of a service or technology package, enhancing their productivity and environmental sustainability.

5. Conclusions

This study provides key insights into the potential of FW-derived fertilizers for agronomic effectiveness and predicting PY and IENU via data-driven models. By rigorously filtering out missing values and outliers, Data 2 delivered reliable and consistent results. Correlation analysis revealed that decomposition duration positively impacted PY and IENU, while temperature and volatile solids had negative correlations. ML models outperformed LR, with RF and CB achieving high PY prediction accuracy and XGB excelling in IENU prediction. By integrating predictive simulations into fertilization planning, this study contributes to sustainable agriculture by enhancing resource efficiency and reducing reliance on synthetic fertilizers. Future research should explore larger datasets and additional environmental factors to refine ML-based fertilizer optimization strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Distributions of train and test sets across four versions of data of PY; Figure S2: Distributions of train and test sets across four versions of data of IENU; Figure S3: Comparison results of train/test data using ML models (data 4); Table S1: Techniques used in training and tuning ML models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. and X.C.N; methodology, KK. and X.C.N.; software, X.C.N.; validation, T.B.Q, C.C.N., P.K., I.K., A.C. and L.S.; data curation, K.K and P.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K., T.B.Q, C.C.N., P.K., I.K., L.S., A.C., and X.C.N.; writing—review and editing, K.K. and X.C.N; visualization, K.K. and X.C.N; funding acquisition, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research entitled “[FOODWASTE-FERT-ML] Application and comparison of the ML algorithms in valorisation of foodwaste as fertilisers” was co-financed by the scholarship for the research stay at Duy Tan University Nr BPN/BIL/2021/1/00235/U/0001 funded by Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange (Agreement signed on 5.01.2023).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Álvarez Salas, M.; Sica, P.; Rydgård, M.; Sitzmann, T.J.; Nyang’au, J.O.; El Mahdi, J.; Moshkin, E.; de Castro e Silva, H.L.; Chrysanthopoulos, S.; Kopp, C.; et al. Current challenges on the widespread adoption of new bio-based fertilizers: insights to move forward toward more circular food systems. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, M.; Bünemann, E.K. Quality of bio-based fertilizers is decisive for improving soil quality in Europe—A meta-analysis. Soil Use and Management 2025, 41, e70012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.; Hoang, S.A.; Bradney, L.; Rinklebe, J.; Kirkham, M.B.; Bolan, N.S. Value of dehydrated food waste fertiliser products in increasing soil health and crop productivity. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 111927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, J.C.; Lee, J.T.E.; Lim, J.W.; Song, S.; Tan, J.K.N.; Chiam, Z.Y.; Yap, K.Y.; Lim, E.Y.; Zhang, J.; Tan, H.T.W.; et al. Closing the food waste loop: Food waste anaerobic digestate as fertilizer for the cultivation of the leafy vegetable, xiao bai cai (Brassica rapa). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 715, 136789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Lu, D.; Qian, T.; Zhou, Y. Thermal hydrolyzed food waste liquor as liquid organic fertilizer. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 775, 145786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Counts. Global Challenges; https: //www.theworldcounts.com/challenges/people-and-poverty/hunger-and-obesity/food-waste-statistics, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. In “Energy-smart” food for people and climate: issue paper. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; The Food and Agriculture Organization, 2011.

- Elgarahy, A.M.; Eloffy, M.G.; Alengebawy, A.; El-Sherif, D.M.; Gaballah, M.S.; Elwakeel, K.Z.; El-Qelish, M. Sustainable management of food waste; pre-treatment strategies, techno-economic assessment, bibliometric analysis, and potential utilizations: A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2023, 225, 115558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razouk, A.; Tiganescu, E.; von Glahn, A.J.; Abdin, A.Y.; Nasim, M.J.; Jacob, C. The future in the litter bin – bioconversion of food waste as driver of a circular bioeconomy. Frontiers in Nutrition 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zeng, B.; Wang, P.; Li, J.; Cui, R.; Ren, L. Food waste anaerobic biogas slurry as fertilizer: Potential salinization on different soil layer and effect on rhizobacteria community. Waste Management 2022, 144, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Lim, J.W.; Lee, J.T.E.; Cheong, J.C.; Hoy, S.H.; Hu, Q.; Tan, J.K.N.; Chiam, Z.; Arora, S.; Lum, T.Q.H.; et al. Food-waste anaerobic digestate as a fertilizer: The agronomic properties of untreated digestate and biochar-filtered digestate residue. Waste Management 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, Z.; Hagare, D.; Jayasena, V.; Swick, R.; Rahman, M.M.; Boyle, N.; Ghodrat, M. Recycling of food waste to produce chicken feed and liquid fertiliser. Waste Management 2021, 131, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuligowski, K.; Konkol, I.; Świerczek, L.; Chojnacka, K.; Cenian, A.; Szufa, S. Evaluation of Kitchen Waste Recycling as Organic N-Fertiliser for Sustainable Agriculture under Cool and Warm Seasons. Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Nguyen, X.C.; Tran, Q.B.; Huyen Nguyen, T.T.; Ge, S.; Nguyen, D.D.; Nguyen, V.T.; Le, P.C.; Rene, E.R.; Singh, P.; et al. Machine learning-assisted evaluation of potential biochars for pharmaceutical removal from water. Environ. Res. 2022, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.C.; Bui, V.K.H.; Cho, K.H.; Hur, J. Practical application of machine learning for organic matter and harmful algal blooms in freshwater systems: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 54, 953–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, P.; Prabhakar, M.R.; Liu, C.; Li, F.; Nguyen, X.C.; Nageshwari, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, P. Predictive Capability of Phosphate Recovery from Wastewater Using a Rough Set Machine Learning Model. ACS ES&T Engineering, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.C.; Ly, Q.V.; Peng, W.; Nguyen, V.H.; Nguyen, D.D.; Tran, Q.B.; Huyen Nguyen, T.T.; Sonne, C.; Lam, S.S.; Ngo, H.H.; et al. Vertical flow constructed wetlands using expanded clay and biochar for wastewater remediation: A comparative study and prediction of effluents using machine learning. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Dai, W.; Gao, H.; Xu, W.; Wei, X. Correlation between Grain Yield and Fertilizer Use Based on Back Propagation Neural Network. Nongye Jixie Xuebao/Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Machinery 2017, 48, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Dong, Z.; Wu, Z.; Fang, K. Optimization of maize planting density and fertilizer application rate based on BP neural network. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 2017, 33, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Liu, H.; Ustin, S.L.; Zhang, X. Predicting maize yield at the plot scale of different fertilizer systems by multi-source data and machine learning methods. Remote Sensing 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, T.H.; Omari, R.A.; Barkusky, D.; Bellingrath-Kimura, S.D. Statistical analysis versus the m5p machine learning algorithm to analyze the yield of winter wheat in a long-term fertilizer experiment. Agronomy 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-María, G.E.; Moriconi, J.I.; Oliferuk, S. Internal efficiency of nutrient utilization: what is it and how to measure it during vegetative plant growth? J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 3011–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, I.J. Assessing internal crop nitrogen use efficiency in high-yielding irrigated cotton. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2011, 90, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-J.; Park, R.-D.; Kim, Y.-W.; Shim, J.-H.; Chae, D.-H.; Rim, Y.-S.; Sohn, B.-K.; Kim, T.-H.; Kim, K.-Y. Effect of food waste compost on microbial population, soil enzyme activity and lettuce growth. Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 93, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tampio, E.; Salo, T.; Rintala, J. Agronomic characteristics of five different urban waste digestates. J. Environ. Manage. 2016, 169, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gondek, K.; Filipek-Mazur, B. Accumulation of microelements in oat biomass and their availability in soil fertilised with compost of plant wastes (in Polish). Acta Agrophysica 2006, 8, 579–590. [Google Scholar]

- Keeling, A.A.; Griffiths, B.S.; Ritz, K.; Myers, M. Effects of compost stability on plant growth, microbiological parameters and nitrogen availability in media containing mixed garden-waste compost. Bioresour. Technol. 1995, 54, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordovil, C.M.; Cabral, F.; Coutinho, J. Potential mineralization of nitrogen from organic wastes to ryegrass and wheat crops. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 3265–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondek, K.; Filipek-Mazur, B. Fertilization Value of Green Waste Compost from Krakow. Problem Books on Progress of Agricultural Sciences 2003, 494, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Jasiewicz, C.; Antonkiewicz, J.; Baran, A. The Effect of Fertilization on Yielding and Nitrogen Content in Tall Oat Grass (In Polish) Problem Books on Progress of Agricultural Sciences 2006, 513.

- Wiater, J. The Sequent Impact of Organic Wastes on Yielding and Chemical Composition of Winter Whea. Problem Books on Progress of Agricultural Sciences 2003, 494, 525–532. [Google Scholar]

- Martyniak, D.; Prokopiuk, K.; Żurek, G.; Rybka, K. Measuring Fluorescence as a Means to Evaluate the Physiological Reaction to Growth Retardant Applied to Manage Turf. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiewicz, C.; Antonkiewicz, J. The Effect of a Dose and Kind of Fertilizer on Maize Nitrogen Concentration. In Proceedings of the Environmental Pollution by Nitrogen, Olecko, Poland; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jamison, J.; Khanal, S.K.; Nguyen, N.H.; Deenik, J.L. Assessing the Effects of Digestates and Combinations of Digestates and Fertilizer on Yield and Nutrient Use of Brassica juncea (Kai Choy). Agronomy 2021, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D.M.; Bary, A.I.; Thomas, D.R.; Fransen, S.C.; Cogger, C.G. Food Waste Compost Effects on Fertilizer Nitrogen Efficiency, Available Nitrogen, and Tall Fescue Yield. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2002, 66, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, F.; Junior, A.; Loss, A.; Malinowski, C.; Matias, M. Effects of food waste digested materials on Lactuva sativa growth and soil composition. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2022, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messiga, A.J.; Sharifi, M.; Munroe, S. Combinations of cover crop mixtures and bio-waste composts enhance biomass production and nutrients accumulation: a greenhouse study. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2016, 31, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.; Kim, W.; Oh, T.-K.; So, Y.-S. Nitrogen (N) use efficiency and yield in rice under varying types and rates of N source: chemical fertilizer, livestock manure compost and food waste-livestock manure compost. Applied Biological Chemistry 2023, 66, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragicevic, I.; Sogn, T.A.; Eich-Greatorex, S. Recycling of Biogas Digestates in Crop Production—Soil and Plant Trace Metal Content and Variability. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asagi, N.; Minamide, K.; Uno, T.; Saito, M.; Ito, T. Acidulocompost, a food waste compost with thermophilic lactic acid fermentation: its effects on potato production and weed growth. Plant Production Science 2016, 19, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondek, K.; Filipek-Mazur. Agro-chemical assessment of fertilizer value of composts of various origin (in Polish). Acta Agrophysica 2005, 5, 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. The Annals of Statistics 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhang, D.; Cui, T.; He, X.; Xiao, T.; Xie, C.; Li, H. Corn variable-rate seeding decision based on gradient boosting decision tree model. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, J.R. Combining instance-based and model-based learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning, Amherst, MA, USA, 1993.

- Quinlan, J.R. Learning with continuous classes. In Proceedings of the 5th Australian joint conference on artificial intelligence; 1992; pp. 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M.; Johnson, K. Applied Predictive Modeling; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2013; pp. 101–139. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, X.C.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; La, D.D.; Kumar, G.; Rene, E.R.; Nguyen, D.D.; Chang, S.W.; Chung, W.J.; Nguyen, X.H.; Nguyen, V.K. Development of machine learning - based models to forecast solid waste generation in residential areas: A case study from Vietnam. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2021, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, California, USA, 2016.

- Naghdyzadegan Jahromi, M.; Zand-Parsa, S.; Razzaghi, F.; Jamshidi, S.; Didari, S.; Doosthosseini, A.; Pourghasemi, H. Developing machine learning models for wheat yield prediction using ground-based data, satellite-based actual evapotranspiration and vegetation indices. European Journal of Agronomy 2023, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, F.; Yushchenko, A.; Stratmann, B.; Steinhage, V. Extreme Gradient Boosting for yield estimation compared with Deep Learning approaches. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 202, 107346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Khair, I.; Ifty, R.A.; Hossain, S.; Arefin, M.N.; Abid, F.B.A. Bangladeshi Agricultural Product Forecasting Approach Using Permutation Driven Machine Learning Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Recent Progresses in Science, 26-27 Dec. 2022, 2022, Engineering and Technology (ICRPSET); pp. 1–6.

- Belgiu, M.; Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2016, 114, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. Akaike, H. A New Look at the Statistical Model Identification. In Selected Papers of Hirotugu Akaike, Parzen, E., Tanabe, K., Kitagawa, G., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 1998; pp. 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas C Montgomery, E.A.P. , G Geoffrey Vining. Introduction to linear regression analysis, John Wiley & Sons, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, X.C.; Nguyen, T.P.; Lam, V.S.; Le, P.C.; Vo, T.D.H.; Hoang, T.H.T.; Chung, W.J.; Chang, S.W.; Nguyen, D.D. Estimating ammonium changes in pilot and full-scale constructed wetlands using kinetic model, linear regression, and machine learning. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 168142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazi, X.E.; Moshou, D.; Alexandridis, T.; Whetton, R.L.; Mouazen, A.M. Wheat yield prediction using machine learning and advanced sensing techniques. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 121, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Bari, B.S.; Yusup, Y.; Kamaruddin, M.A.; Khan, N. A Comprehensive Review of Crop Yield Prediction Using Machine Learning Approaches With Special Emphasis on Palm Oil Yield Prediction. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 63406–63439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamgholizadeh, S.; Parsaeian, M.; Baradaran, M. Seed yield prediction of sesame using artificial neural network. European Journal of Agronomy 2015, 68, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whetton, R.; Zhao, Y.; Shaddad, S.; Mouazen, A.M. Nonlinear parametric modelling to study how soil properties affect crop yields and NDVI. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 138, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.B.; Gentry, D.; Tryforos, A.; Fultz, L.; Beasley, J.; Gentimis, T. Soybean yield prediction using machine learning algorithms under a cover crop management system. Smart Agricultural Technology 2024, 8, 100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Klompenburg, T.; Kassahun, A.; Catal, C. Crop yield prediction using machine learning: A systematic literature review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 177, 105709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lischeid, G.; Webber, H.; Sommer, M.; Nendel, C.; Ewert, F. Machine learning in crop yield modelling: A powerful tool, but no surrogate for science. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2022, 312, 108698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Tao, F. Wheat yield predictions at a county and field scale with deep learning, machine learning, and google earth engine. European Journal of Agronomy 2021, 123, 126204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Honkavaara, E.; Hayden, M.; Kant, S. UAV Remote Sensing Phenotyping of Wheat Collection for Response to Water Stress and Yield Prediction Using Machine Learning. Plant Stress 2024, 12, 100464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Bai, Z.; He, P.; Xu, X.; Ma, J.; Masiliūnas, D. Space-time statistical analysis and modelling of nitrogen use efficiency indicators at provincial scale in China. European Journal of Agronomy 2020, 115, 126032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Tao, X.; Chen, X.; Li, X. Rapid prediction of winter wheat yield and nitrogen use efficiency using consumer-grade unmanned aerial vehicles multispectral imagery. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Cui, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhuang, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Determining effects of water and nitrogen input on maize (Zea mays) yield, water- and nitrogen-use efficiency: A global synthesis. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 9699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correndo, A.A.; Rotundo, J.L.; Tremblay, N.; Archontoulis, S.; Coulter, J.A.; Ruiz-Diaz, D.; Franzen, D.; Franzluebbers, A.J.; Nafziger, E.; Schwalbert, R.; et al. Assessing the uncertainty of maize yield without nitrogen fertilization. Field Crops Res. 2021, 260, 107985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; He, P.; Zhang, H.; Peng, W.; Qiu, J.; Lü, F. Applications of machine learning tools for biological treatment of organic wastes: Perspectives and challenges. Circular Economy 2024, 3, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durai, S.K.S.; Shamili, M.D. Smart farming using Machine Learning and Deep Learning techniques. Decision Analytics Journal 2022, 3, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Ouderji, Z.H.; Uzma; Yu, Z. ; Sloan, W.T.; You, S. Machine learning for sustainable organic waste treatment: a critical review. npj Materials Sustainability 2024, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).