Submitted:

29 April 2025

Posted:

30 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

1.1. Nutritional Security and Dietary Diversification in LMICs

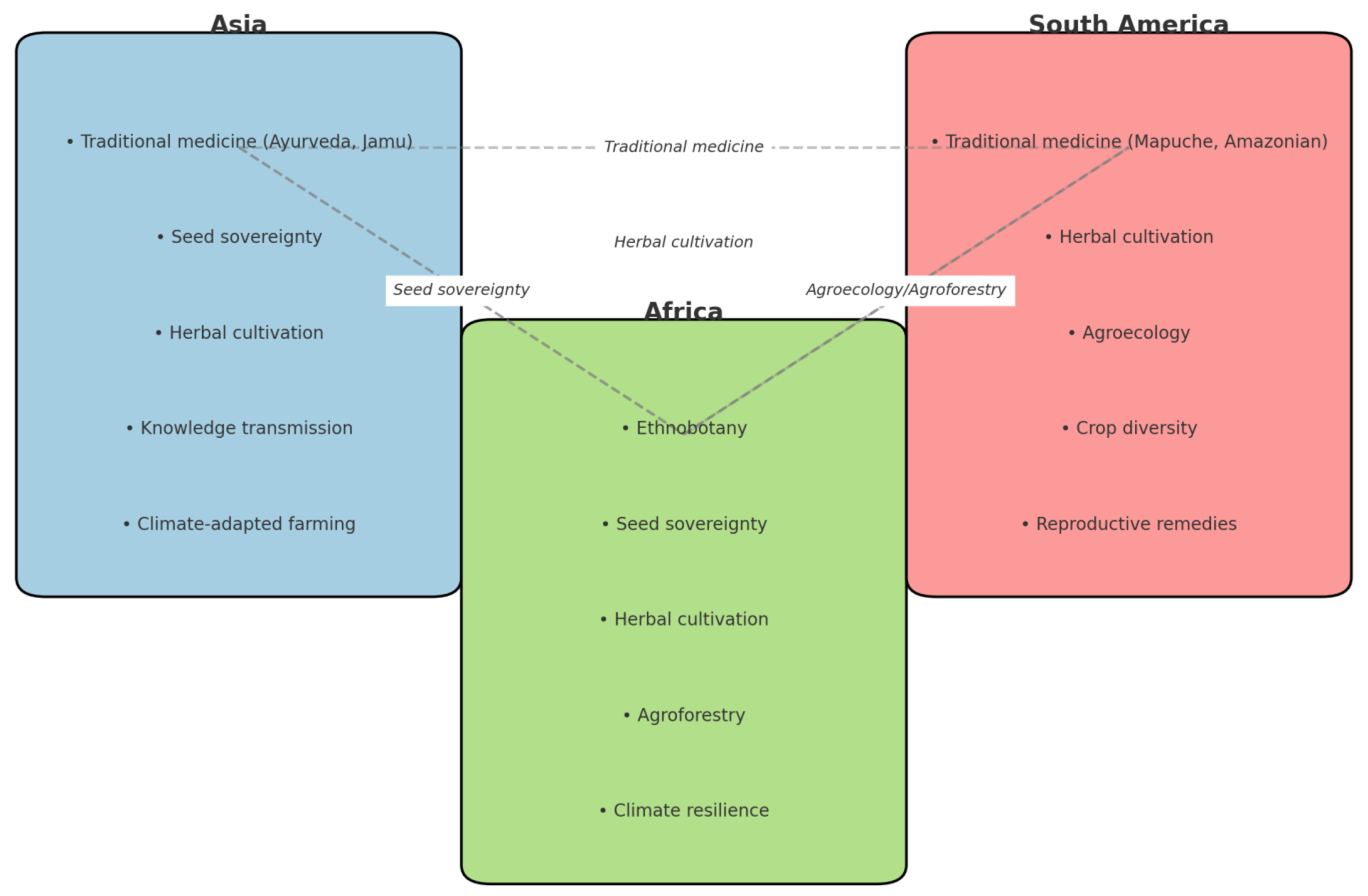

1.2. Asia

1.3. Africa

1.4. South-America

1.5. Empowerment and Psychosocial Well-Being Among Women in LMICs

1.6. Africa

1.7. South-America

1.8. Asia

1.9. Mitigating Environmental and Climate-Related Health Risks in LMICs

1.10. Preserving Medicinal Knowledge and Women's Reproductive Health in LMICs

2. Strengths and Limitations

2.1. Policy Implications

2.2. Policy Recommendations

- Legal Recognition: Acknowledge women's roles as traditional health practitioners and protect their rights under national law.

- Community-Based Conservation: Support women’s herbal gardens and seed banks through agroecological funding.

- Intellectual Property Protections: Enact fair benefit-sharing mechanisms for traditional remedies.

- Gender-Inclusive Health Systems: Integrate traditional healing into formal health care with training and certification for women healers.

- Research & Documentation: Fund participatory ethnobotanical research led by women to preserve and validate their knowledge.

3. Conclusions

Availability of data and material

Consent to participate

Consent for publication

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of interest

References

- Acevedo-Ortiz, M. A. , Lugo-Espinosa, G., Ortiz-Hernández, Y. D., Pérez-Pacheco, R., Ortiz-Hernández, F. E. & Granados-Echegoyen, C. A. 2024. Women's Leadership in Sustainable Agriculture: Preserving Traditional Knowledge Through Home Gardens in Santa Maria Jacatepec, Oaxaca. Sustainability (2071-1050),.

- Adefila, A. O. , Ajayi, O. O., Toromade, A. S. & Sam-Bulya, N. J. 2024. Integrating traditional knowledge with modern agricultural practices: A sociocultural framework for sustainable development. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture and Development.

- Adeloye, F. F. 2021. Influence of food preferences on rural and urban households’food security in Southwestern Nigeria.

- Amarasinghe, G. S. , Agampodi, T. C., Mendis, V., Malawanage, K., Kappagoda, C. & Agampodi, S. B. 2022. Prevalence and aetiologies of anaemia among first trimester pregnant women in Sri Lanka; the need for revisiting the current control strategies. BMC pregnancy and childbirth,.

- Amenu, E. 2007. Use and management of medicinal plants by indigenous people of Ejaji area (Chelya Woreda) West Shoa, Ethiopia: An ethnobotanical approach. In M. Sc. Thesis.

- Amjad, R. , Malik, S., Noreen, S., Ali, S., Zahra, S., Farooq, J., Shareef, M. & Ali, K. 2024. Traditional Pakistani Medicines in Modern World. Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Chinese.

- Anyamaobi, O.P. , Wokem, G.N., Enweani Bessie, I., Okosa, N.J.A., Opara, C.E. and Nwokeji, M.C., 2020. Antimicrobial effect of garlic and ginger on Staphylococcus aureus from clinical specimens in Madonna University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. International Journal of Recent Scientific Research, 11(3), pp.37840-37845.

- Anderson, K. 2022. Maya women, non-traditional agriculture and “care”: Rethinking feminist geographies of “care” from the Guatemalan Highlands. University of Toronto (Canada).

- Andrango, G. , Johnson, A. & Bellemare, M. F. 2020. Quinoa Production and Growth Potential in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru. Choices,.

- Asfaw, Z. 2000. Barleys of Ethiopia. Genes in the field: On-farm conservation of crop diversity.

- Ayim, I. , Ambenne, M., Commey, V. & Alenyorege, E. A. 2024. Health and nutritional perspectives of foods in the middle belt of Ghana. Nutritional and Health Aspects of Food in Western Africa.

- Balamurugan, S. , Vijayakumar, S., Prabhu, S., & Morvin Yabesh, J. E. (2017). Traditional plants used for the treatment of gynaecological disorders in Vedaranyam taluk, South India - An ethnomedicinal survey. Journal of traditional and complementary medicine, 8(2), 308–323. [CrossRef]

- <monospace>Belew, T. F. D. 2015. A review on production status and consumption pattern of vegetable in Ethiopia. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare, 5.

- Benefitting from a tribal community’s symbiotic relationship with nature: The healing system practiced by Irula women – Tamil Nadu – Tribal Cultural Heritage in India. (n.d.). Retrieved , from https://indiantribalheritage.org/? 22 April 1517.

- Boliko, M. C. 2019. FAO and the situation of food security and nutrition in the world. Journal of nutritional science and vitaminology,.

- Bomfim, B. L. S. , Da Fonseca Filho, I. C., Lopes, C. G. R. & De Barros, R. F. M. 2024. Indigenous agriculture in Brazil: review (2011-2021). Caderno Pedagógico, 3372. [Google Scholar]

- Bosman, M. J. C. , Kruger, A., Matenge, S. T. P., Van Der Merwe, M. & De Beer, H. 2012. Consumers' beliefs on indigenous and traditional foods and acceptance of products made with cow pea leaves.

- Botaro, A. & Mulugeta, G. 2020. Role of Women in Agro forestry Management in Tembaro District, Southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Forestry and Horticulture,.

- Bruna, N. 2019. Land of plenty, land of misery: Synergetic resource grabbing in Mozambique. Land,.

- Bull, B. & Rosales, A. 2020. The crisis in Venezuela. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies/Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe, 1-20.

- Cagayan, M. S. F. S. , Sia, I. C., Manzo, A. B., Hafalia, D. J. M., Dando, L. R. A. & Nava, L. M. H. 2017. Herbal Therapies for Women's Health in Indigenous Atis of Brgy. Sta. Barbara, Iba, Zambales. Philippine Journal of Health Research and Development,.

- Casagrande, A. , Ritter, M. R. & Kubo, R. R. 2023. Traditional knowledge in medicinal plants and intermedicality in urban environments: a case study in a popular community in southern Brazil. Ethnobotany Research and Applications,.

- Castañeda, X. , García, C. & Langer, A. 1996. Ethnography of fertility and menstruation in rural Mexico. Social Science & Medicine,.

- Chagomoka, T. , Afari-Sefa, V. & Pitoro, R. 2013. Value chain analysis of indigenous vegetables from Malawi and Mozambique.

- Change, I. P. O. C. 2001. Climate change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Genebra, Suíça.

- Chebii, W. K. 2023. Governance of the Practice of Traditional Medicine in Selected Markets of Western Kenya. University of Nairobi.

- Chizari, M. , Lindner, J., & Bashardoost, R. (1997). PARTICIPATION OF RURAL WOMEN IN RICE PRODUCTION ACTIVITIES AND EXTENSION EDUCATION PROGRAMS IN THE GILAN PROVINCE, IRAN. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education, 4(3). https://www.academia. 1180. [Google Scholar]

- <monospace>De Meyer, E. , Ceuterick, M., Vanhove, W., Heytens, J., Mimbu, J. E., Van Damme, P. & De La Peña, E. 2025. Medicinal Plant Use and Diversity in the Urban Area of Idiofa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of Ethnobiology, 45, 38-50.

- De Silva, N. 2016. Sri Lanka’s Traditional Knowledge about Health and Wellbeing: History, Present Status and the Need for Safeguarding. Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Cultural Expressions of South Asia.

- De Silva, N. 2024. Indigenous Knowledge in Agricultural Production: The Sri Lankan Experience. Environmental and Ecological Sustainability Through Indigenous Traditions: Perspectives from the Global South. Springer.

- Diame, G. 2010. Ethnobotany and ecological studies of plants used for reproductive health: a case study at Bia biosphere reserve in the western region of Ghana. Department of Environmental Science, University of Cape Coast, Ghana,.

- Diversi, Y. Affirming Life and Diversity. Rural images and voices on Food Sovereignty in south India.

- Do Amaral Valèrio, E. 2019. Women's empowerment in Agriculture: a case of Northeast Brazil. Newcastle University.

- Drucza, K. & Peveri, V. Literature on gendered agriculture in Pakistan: Neglect of women's contributions. Women's Studies International Forum, 2018. Elsevier, 180-189.

- Effiong, J. 2013. Challenges and prospects of rural women in Agricultural production in Nigeria. Lwati: A Journal of Contemporary Research,.

- Emencheta, S.C. , Enweani, I.B., Oli, A.N., Okezie, U.M. and Attama, A.A., 2019. Evaluation of antimicrobial activities of fractions of plant parts of Pterocarpus santalinoides. 1: Biotechnology Journal International 23(3).

- Enweani, I.B. , Obroku, J., Enahoro, T. and Omoifo, C., 2004. The biochemical analysis of soursop (Annona muricata L.) and sweetsop (A. squamosa L.) and their potential use as oral rehydration therapy. Journal of Food Agriculture and Environment, 2, pp.39-43.

- Enweani-Nwokelo, I. B. , Urama, E. U., and Achukwu, N. O, 2025. Evaluation of the antimicrobial activities of Napoleona imperialis leaf extracts against multi-drug resistant bacterial isolates from diabetic foot ulcer. 7: African Journal of Clinical and Experimental Microbiology 26 (1).

- Erni, C. 2015. Shifting cultivation, livelihood and food security: New and old challenges for indigenous peoples in Asia. Shifting cultivation, livelihood and food security,.

- Ervilha, N. O. 2022. Climate-Smart Agriculture and Mozambique’s rural constellations. Ghent University.

- Ethnobotany, U. 2010. Herbal and Food Medicines amongst the Bangladeshi Community in West Yorkshire, UK. Ethnobotany in the New Europe: People, Health, and Wild Plant Resources,.

- Fact sheet: Iran—Women, agriculture and rural development. (n.d.). Retrieved , from https://www.fao.org/4/v9103e/v9103e07. 22 April.

- Fatima, B. 2024. Social-ecological resurgence through farmers’ traditional knowledge and agroecology in Pakistan.

- Faye, J. B. 2020. Indigenous farming transitions, sociocultural hybridity and sustainability in rural Senegal. NJAS-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences,.

- Ferdous, T. & Hossain, M. N. 2020. A review on traditional medicinal plants used to treat gynaecological disorder in Bangladesh. Bioresearch Communications-(BRC),.

- Garutsa, T. C. & Nekhwevha, F. H. 2016. Labour-burdened women utilising their marginalised indigenous knowledge in food production processes: The case of Khambashe rural households, Eastern Cape, South Africa. South African Review of Sociology,.

- Gauchan, D. & Shrestha, R. B. 2020. Community based seed systems for agrobiodiversity and resilient farming of smallholder agriculture in South Asia. Strengthening Seed Systems-Promoting Community Based Seed Systems for Biodiversity Conservation and Food & Nutrition Security in South Asia.

- Global Nutrition Report | Country Nutrition Profiles—Global Nutrition Report. (n.d.). Retrieved , from https://globalnutritionreport. 22 April.

- Gómez-Baggethun, E. , Gren, Å., Barton, D. N., Langemeyer, J., Mcphearson, T., O’farrell, P., Andersson, E., Hamstead, Z. & Kremer, P. 2013. Urban ecosystem services. Urbanization, biodiversity and ecosystem services: Challenges and opportunities: A global assessment.

- Gonçalves, M. & Hanazaki, N. 2023. Afro-diasporic ethnobotany: Food plants and food sovereignty of Quilombos in Brazil. Ethnobotany Research and Applications,.

- Guo, T. , García-Martín, M. & Plieninger, T. 2021. Recognizing indigenous farming practices for sustainability: a narrative analysis of key elements and drivers in a Chinese dryland terrace system. Ecosystems and People,.

- Haikera, H. K. 2021. Investigating the influence of cultural practices on pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum care in kavango regions, namibia in southern africa. Namibia University of Science and Technology.

- Harding, K. L. , Aguayo, V. M., Namirembe, G. & Webb, P. 2018. Determinants of anemia among women and children in Nepal and Pakistan: An analysis of recent national survey data. Maternal & child nutrition,.

- Hardon, A. & Lim Tan, M. 2024. Packaged Plants: Seductive supplements and metabolic precarity in the Philippines, UCL Press.

- Hoque, M. 2023. The impact of floods on the livelihood of rural women farmers and their adaptation strategies: insights from Bangladesh. Natural Hazards, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Huambachano, M. 2019. Traditional ecological knowledge and indigenous foodways in the Andes of Peru. Review of International American Studies,.

- Hull, T. H. & Hull, V. J. 2001. Means, motives, and menses: use of herbal emmenagogues in Indonesia. Regulating menstruation: Beliefs, practices, interpretations.

- Hussain, S. , Malik, F., Khalid, N., Qayyum, M. A. & Riaz, H. 2012. Alternative and traditional medicines systems in Pakistan: history, regulation, trends, usefulness, challenges, prospects and limitations. A compendium of essays on alternative therapy.

- Hussain, S. G. 2017. Identification and Modeling of Suitable Cropping Systems and Patterns for Saline, Drought and Flood Prone Areas of Bangladesh, Climate Change Unit, Christian Commission for Development in Bangladesh.

- Huynh, C. V. , Pham, T. G., Nguyen, T. Q., Nguyen, L. H. K., Tran, P. T., Le, Q. N. P. & Nguyen, M. T. H. 2020. Understanding indigenous farming systems in response to climate change: An investigation into soil erosion in the mountainous regions of Central Vietnam. Applied Sciences,.

- Inogwabini, B.-I. 2014. Conserving biodiversity in the Democratic Republic of Congo: a brief history, current trends and insights for the future. Parks,.

- Iyiola, A. O. & Adegoke Wahab, M. K. 2024. Herbal medicine methods and practices in Nigeria. Herbal medicine phytochemistry: applications and trends.

- Jahan, S. , Mozumder, Z. M. & Shill, D. K. 2022. Use of herbal medicines during pregnancy in a group of Bangladeshi women. Heliyon,.

- Jana, A. , Chattopadhyay, A. & Saha, U. R. 2022. Identifying risk factors in explaining women’s anaemia in limited resource areas: evidence from West Bengal of India and Bangladesh. BMC Public Health,.

- Jat, M. L. , Dagar, J. C., Sapkota, T. B., Govaerts, B., Ridaura, S., Saharawat, Y. S., Sharma, R. K., Tetarwal, J., Jat, R. K. & Hobbs, H. 2016. Climate change and agriculture: adaptation strategies and mitigation opportunities for food security in South Asia and Latin America. Advances in agronomy,.

- Kankanamalage, T. , Dharmadasa, R., Abeysinghe, D. & Wijesekara, R. 2014. A survey on medicinal materials used in traditional systems of medicine in Sri Lanka. Journal of Ethnopharmacology,.

- Karmakar, B. & Roy, S. 2024. Traditional and Unconventional Food Crops with the Potential to Boost Health and Nutrition with Special Reference to Asian and African Countries. Traditional Foods: The Reinvented Superfoods.

- Kay, M. A. 1996. Healing with plants in the American and Mexican West, University of Arizona Press.

- Keya, T. A. 2023. Prevalence and predictors of anaemia among women of reproductive age in South and Southeast Asia. Cureus,.

- Khalid, K. a. T. & Mohamed, N. 2020. MIDWIVES AND HERBAL REMEDIES: THE SUSTAINABLE ETHNOSCIENCE0. Kajian Malaysia: Journal of Malaysian Studies,.

- Kinyoki, D. , Osgood-Zimmerman, A. E., Bhattacharjee, N. V., Kassebaum, N. J. & Hay, S. I. 2021. Anemia prevalence in women of reproductive age in low-and middle-income countries between 2000 and 2018. Nature medicine,.

- Köhler, R. , Sae-Tan, S., Lambert, C. & Biesalski, H. K. 2018. Plant-based food taboos in pregnancy and the postpartum period in Southeast Asia–a systematic review of literature. Nutrition & Food Science,.

- Kozak, V. 2022. Food systems of the Andean Quechua: Countering industrial agriculture through harmonious living, food sovereignty, and traditional knowledge.

- Krier, S. E. 2011. Our roots, our strength: The jamu industry, women's health and Islam in contemporary Indonesia, University of Pittsburgh.

- Kropi, K. , Jastone, K., Kharumnuid, S. A., Das, H. K. & Naga, M. M. 2024. Cross-cultural study on the uses of traditional herbal medicine to treat various women's health issues in Northeast India. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine,.

- Kuo, G. , N’danikou, S., Dinssa, F., Roothaert, R., Rugalema, R., Simon, J., Wopereis, M. & Van Zonneveld, M. 2022. All-Africa Summit on Diversifying Food Systems with African Traditional Vegetables to Increase Health, Nutrition, and Wealth. Journal of Medicinally Active Plants,.

- Kumar, A. , A C, J. 2019. Medicinal Herbs for Home Gardens and their Uses. MEDICINAL AND AROMATIC PLANTS.

- Leguizamón, A. 2014. Modifying Argentina: GM soy and socio-environmental change. Geoforum,.

- Liang, Y. , Janssen, B., Casteel, C., Nonnenmann, M., & Rohlman, D. S. (2022). Agricultural Cooperatives in Mental Health: Farmers' Perspectives on Potential Influence. Journal of agromedicine, 27(2), 143–153. [CrossRef]

- Liyanagunawardena, S. 2022. Therapeutic practices in everyday life: illness and health seeking in a rural community in Sri Lanka. Open Access Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington.

- Luján, M. C. & Martínez, G. J. 2019. Etnobotánica médica urbana y periurbana de la ciudad de Córdoba (Argentina).

- M, M. S. , G, S., & M, S. (2021). Gynaecological Management in Siddha System of Medicine. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research, 39(4), 31494–31496. [CrossRef]

- <monospace>Manikyam, H. K. 2024. Medicinal plants and alternative therapies for reproductive system health. Nutraceuticals: A Holistic Approach to Disease Prevention, 237.

- Martín, J. G. 2016. Reproductive health care and indigenous peoples in Venezuela. Handbook on Gender and Health.

- Matsa, W. & Mukoni, M. 2013. Traditional science of seed and crop yield preservation: exploring the contributions of women to indigenous knowledge systems in Zimbabwe.

- Meinzen-Dick, R. , Quisumbing, A., Doss, C. & Theis, S. 2019. Women's land rights as a pathway to poverty reduction: Framework and review of available evidence. Agricultural systems,.

- Mendum, R. & Njenga, M. 2018. Integrating wood fuels into agriculture and food security agendas and research in sub-Saharan Africa. Facets,.

- Milburn, M. P. 2004. Indigenous nutrition: Using traditional food knowledge to solve contemporary health problems. American Indian Quarterly.

- Motta, R. & Teixeira, M. A. 2022. Food sovereignty and popular feminism in Brazil. Anthropology of food.

- Nabatanzi, A. , Walusansa, A., Nangobi, J. & Natasha, D. A. 2024. Understanding maternal Ethnomedical Folklore in Central Uganda: a cross-sectional study of herbal remedies for managing Postpartum hemorrhage, inducing uterine contractions and abortion in Najjembe sub-county, Buikwe district. BMC Women's Health,.

- Napagoda, M. T. , Sundarapperuma, T., Fonseka, D., Amarasiri, S. & Gunaratna, P. 2019. Traditional uses of medicinal plants in Polonnaruwa district in North Central Province of Sri Lanka. Scientifica,.

- Nisivaco, T. 2017. NAFTA and its effect on corn, migration and human rights in Mexico. DePaul University.

- Nuraini, A. , Rabbani, A. H., Jagatru, A. S., Azzahra, A. N., Azizia, M. S., Yasa, A., Saensouk, S. & Setyawan, A. D. 2024. Diversity and use medicinal plants for traditional women’s health care in Kalibawang, Wonosobo District, Indonesia. Asian Journal of Ethnobiology,.

- Obaji, M. , Enweani, I.B. and Oli, A.N., 2020. A unique combination of Alchornea cordifolia and Pterocarpus santalinoides in the management of multi-drug resistant diarrhoegenic bacterial infection. 1: Asian Journal of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences 10 (69).

- Odeyemi, O. , and Enweani-Nwokelo, I. B., 2025. Anti-dermatophytic activities and time-kill kinetics of the methanol extracts of Napoleona imperialis. African Journal of Clinical and Experimental Microbiology 2025; 26 (1): 81 – 93.

- Oli, A.N. , Obaji, M. and Enweani, I.B. 2019. Combinations of Alchornea cordifolia, Cassytha filiformis and Pterocarpus santalinoides in diarrhoeagenic bacterial infections. BMC Res Notes. [CrossRef]

- <monospace>Onah, G.T. , Ajaegbu, E.E. and Enweani, I.B., 2022. Proximate, phytochemical and micronutrient compositions of Dialium guineense and Napoleona imperialis plant parts. GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 18(3), pp.193-205.

- <monospace>Onuoha, V.C. , Enweani, I.B. and Okereke, O.E., 2020. Susceptibility Pattern of Different Parts of Moringa oleifera against Some Pathogenic Fungi, Isolated from Sputum Samples of HIV Positive Individuals Co-Infected with Pulmonary Tuberculosis. J. Adv. Microbiol, 20, pp.56-82.

- <monospace>Ong, H. G. & Kim, Y.-D. 2015. Herbal Therapies and Social-Health Policies: Indigenous Ati Negrito Women’s Dilemma and Reproductive Healthcare Transitions in the Philippines. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2015, 491209.

- Panjaitan, R. G. P. , Khairunnisa, K., Titin, T. & Akbarini, D. 2024. Medicinal plants used for menstrual regulators and pain relievers in Tumiang Village, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity,.

- Parkinson, V. 2013. Climate learning for African agriculture: the case of Mozambique. University of Greenwich: London, UK.

- Parraguez-Vergara, E. , Contreras, B., Clavijo, N., Villegas, V., Paucar, N. & Ther, F. 2018. Does indigenous and campesino traditional agriculture have anything to contribute to food sovereignty in Latin America? Evidence from Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Guatemala and Mexico. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability,.

- Parreño-De Guzman, L. E. , Zamora, O. B. & Bernardo, D. F. H. 2015. Diversified and integrated farming systems (DIFS): Philippine experiences for improved livelihood and nutrition. Journal of Developments in Sustainable Agriculture,.

- Patwardhan, B. & Partwardhan, A. 2005. Traditional Medicine: Modern Approach for affordable global health.

- Pearsall, D. M. 2008. Plant domestication and the shift to agriculture in the Andes. The handbook of South American archaeology.

- Ratnayake, S. , Reid, M., Hunter, D., Larder, N., Silva, R., Kadupitiya, H., Pushpakumara, G., Borelli, T., Mendonce, S. & Liyanage, A. 2023. Exploring social-ecological systems for mainstreaming neglected and underutilised plant foods: local solutions to food security challenges in Sri Lanka. Neglected Plant Foods of South Asia: Exploring and Valorizing Nature to Feed Hunger.

- Ria, A. 2025. A feminist perspective of the differentiated impacts of climate change, adaptation and women’s roles in coastal agriculture in Bangladesh.

- Rola, M. F. M. 1995. The role of women in upland farming systems: a case study of a Philippine village. Women in Upland Agriculture in Asia.

- Rural women’s role in sustainable development. (2023, ). Tehran Times. https://www.tehrantimes. 14 October 4900.

- Sabar, N. 2023. Empowering Women's Health: Ayurveda's Holistic Approach to Menstrual Harmony, Fertility and Menopause. Partners Universal International Innovation Journal,.

- Sahai, S. Commercialisation of indigenous knowledge and benefit sharing. UNCTAD expert meeting on systems and national experiences for protecting traditional knowledge, innovations and practices. Geneva, 2000.

- Sahai, S. 2004. Commercialisation of traditional knowledge and benefit sharing. Protecting and promoting traditional knowledge: systems, national experiences and international dimensions. United Nations, Geneva, Switzerland, 279-292.

- Sarapura, S. L. 2013. Gender and agricultural innovation in peasant production of native potatoes in the Central Andes of Peru. University of Guelph.

- Saxena, L. P. 2020. Community self-organisation from a social-ecological perspective:‘Burlang Yatra’and revival of millets in Odisha (India). Sustainability,.

- Schuster, W. T. 2023. O movimento de mulheres camponesas e a agroecologia como formas de emancipação e reconhecimento.

- Severi, C. 2016. Social sustainability and resilience of the rural communities: the case of soy producers in Argentina and the expansion of the production from Latin America to Africa. Université d'Avignon.

- Shahidullah, A. 2007. Master of Natural Resources Management (MNRM).

- Sher, H. , Aldosari, A., Ali, A. & De Boer, H. J. 2014. Economic benefits of high value medicinal plants to Pakistani communities: an analysis of current practice and potential. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine,.

- Sibanda, M. 2025. Feminist Agroecology: Towards Gender-Equal and Sustainable Food Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Agricultural & Rural Studies,.

- Sitoe, E. 2020. Medicinal ethnobotany of Mozambique: A review and analysis.

- Sunuwar, D. R. , Singh, D. R., Chaudhary, N. K., Pradhan, P. M. S., Rai, P. & Tiwari, K. 2020. Prevalence and factors associated with anemia among women of reproductive age in seven South and Southeast Asian countries: Evidence from nationally representative surveys. PloS one,.

- Torri, M. C. 2010. Medicinal plants used in Mapuche traditional medicine in Araucanía, Chile: linking sociocultural and religious values with local heath practices. Complementary health practice review,.

- Tsakok, I. 2021. Venezuela Agriculture and Food: Resilience or Total Collapse of Food Security Under Repeated Crises? : Policy Center for the New South.

- Tsegaye, B. 1997. The significance of biodiversity for sustaining agricultural production and role of women in the traditional sector: the Ethiopian experience. Agriculture, ecosystems & environment,.

- United Nations. 2015. Sustainable Development Goals, /: Available: http, 2025.

- Urama, E. U. , Enweani-Nwokelo, I. B., and Achukwu, N. O.,2025. Evaluation of invitro antimicrobial activity of Nauclea latifolia root extracts against multi-drug resistant bacterial isolates from diabetic foot ulcers. African Journal of Clinical and Experimental Microbiology, 9: 26 (1).

- <monospace>Uwaga, A. , Nzegbule, E. & Egu, E. 2021. Agroforestry practices and gender relationships in traditional farming systems in Southeastern Nigeria. International Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development, 24, 5587-99.

- Van Der Grinten, L. Mapuche Sustainable Farming: what we can learn from the biggest indigenous group of Chile.

- Vazeux-Blumental, N. , Manicacci, D. & Tenaillon, M. 2024. The milpa, from Mesoamerica to present days, a multicropping traditional agricultural system serving agroecology. Comptes Rendus. Biologies,.

- Wanjira, E. O. & Muriuki, J. 2020. Review of the status of agroforestry practices in Kenya. Background Study for Preparation of Kenya National Agroforestry Strategy (2021-2030). DOI,.

- Westengen, O. T. , Haug, R., Guthiga, P. & Macharia, E. 2019. Governing seeds in East Africa in the face of climate change: assessing political and social outcomes. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems,.

- Yakubu, S. A. 2024. Perceived Impact Of The Sun Shaded Agro-Forestry Project On The Livelihoods Of Cocoa Farmers In The Western North Region Of Ghana. University of Cape Coast.

- Zimmerer, K. S. & De Haan, S. 2017. Agrobiodiversity and a sustainable food future. Nature Plants,.

| Country | Indigenous Crops/Practices | Women’s Role | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iran | Rice, wheat and barley, pulses, saffron, and date palms | Planting, weeding, pest control, harvesting, and marketing | Lack of access to resources, limited land ownership, and exclusion from ag extension and education |

| India | Millet, pulses; women-led farming collectives / Millet cultivation, seed saving (Deccan Development Society) | Primary cultivators and decision-makers / Leaders in land reclamation, agroecology, seed saving | Land access, poor integration in national policy / Neglect of traditional grains in public policy |

| Nepal | Millet, legumes, community seed saving | Seed saving, knowledge transmission | Policy neglect, lack of extension services |

| Pakistan | Home gardening, underused indigenous crops / Traditional lentils, millet, sorghum | Informal food providers, limited support / Food producers, limited land rights, informal roles | Exclusion from formal ag programs / Limited access to land, ag extension, and credit |

| Bangladesh | Home gardens, pulses, local leafy greens / Homestead food production, local rice | Primary in-home gardening, food prep / Homestead cultivators, low policy engagement | High anaemia, weak local food systems / Hybrid seed dominance, weak support for women |

| Sri Lanka | Chena cultivation, traditional vegetables, crop rotation / Chena cultivation, ayurvedic systems, herbal medicine | Knowledge holders, labour contribution, food saving and preparation / Healers, food processors | Land use change, undervalued knowledge, urbanization, erosion of traditional systems |

| Philippines | Upland farming, tubers, banana varieties / Kaingin system, root crops, legumes, medicinal plants | Crop managers, food processors / Seed custodians, informal leaders | Deforestation, limited market access / Mining, militarization, policy neglect of indigenous areas |

| Nigeria | Amaranth, cowpea leaves, indigenous vegetables / Fluted pumpkin | Producers, marketers / Key cultivators | Stigma, poor market infrastructure / Low institutional support, limited land ownership |

| DR Congo | Spider plant, amaranth; traditional diets / Cassava, traditional leafy greens | Custodians of seeds, dietary managers / Caretakers of traditional diets and crops | Seed availability, import competition / Conflict, displacement, weak extension services |

| Ghana | Leafy greens, legumes, traditional home gardens / Cocoyam leaves, local leafy greens | Farmers, transmitters of indigenous knowledge / Market participants, custodians of nutrition | Fragmented policy support, funding gaps / Fragmented support, low visibility in policy |

| Ethiopia | Indigenous vegetables, low urban awareness / Teff, barley, sorghum landraces | Undervalued, low visibility in urban settings / Landrace preservationists, informal knowledge | Awareness, market development issues / Documentation gaps, limited female leadership |

| Mozambique | Root crops, traditional vegetables in rural areas / Informal seed systems | Central to rural food production / Central to household food systems, under-resourced | Urbanization, cash crop pressure / Urban migration, poor rural infrastructure |

| Kenya | Nightshade, amaranth; commercialised AIVs / Amaranth, cowpea leaves, AIVs | Leaders in cooperatives and markets / Leaders in cooperatives, agroecology, food markets | Scaling efforts, policy integration / Scaling agroecology, unequal gender participation |

| Rwanda | Pulses, root crops, and indigenous vegetables like Amaranth, African nightshade | Main cultivators | Limited access to quality seeds, land fragmentation, and declining indigenous knowledge transfer |

| Bolivia/Peru | Quinoa, potatoes, amaranth; seed preservation / High-altitude farming | Seed custodians, nutritional gatekeepers / Agrobiodiversity stewards, seed knowledge holders | Commercialisation pressure, gender exclusion / Commercial pressures on biodiversity |

| Brazil | Cassava, maize, beans; women-led agroecology / Medicinal plants (MMC agroecology) | Agroecology activists, land defenders / Feminist movement leaders, food and health activists | Deforestation, agribusiness threats / Agribusiness threats, deforestation, land violence |

| Chile | Quinoa, beans; home gardens, Mapuche traditions / Mapuche traditional farming | Cultural preservation through farming / Cultural preservationists | Monoculture forestry, land loss / Land dispossession |

| Mexico | Milpa system (maize, beans, squash, amaranth) | Seed selectors, food preparers / Milpa stewards, nutrition caregivers | Trade liberalisation, nutritional decline / Health-nutrition transitions |

| Argentina | Maize, sweet potatoes; land pressure / Community-based seed recovery | Marginalised in agri systems / Displaced food providers, landless farming efforts | GM crops, land concentration / Land inequality, GM crop dominance |

| Venezuela | Plantains, cassava; traditional survival farming / Informal indigenous farming | Keepers of traditional food systems / Survival farming leaders, caretakers of traditional food | Economic collapse, food scarcity / Input scarcity, insecurity |

| Tanzania | Indigenous vegetables, local grains, seed banking | Women’s groups improve mental health, seed resilience | Climate impacts, funding gaps for seed systems |

| Approach | Country of Origin | Time period | Brief description | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Siddha Gynecology (Magalir Maruthuvam) | India (Tamil Nadu) | Ancient (2000+ years ago) | A Siddha branch focused on women’s reproductive health including menstruation, fertility, pregnancy, and menopause. Emphasizes natural remedies, dietary regimens, and lifestyle management based on humoral theory (vali, azhal, iyam). | (M, 2021. ) |

| Home-based Herbal Remedies by Women | India (South India) | Ongoing/Traditional | Women in rural areas traditionally prepare herbal decoctions and oils for issues like PCOS, leucorrhoea, infertility, and postpartum recovery, using knowledge passed down generations. | (Balamurugan, 2017) |

| Medicinal Plant Cultivation by Women | India (Tamil Nadu, Kerala, NE states) | Traditional to Present | Women cultivate, preserve, and harvest medicinal plants in home gardens and temple groves. Their knowledge is vital for sustainable use of Siddha herbs and biodiversity conservation. | (Kumar, 2019) |

| Community Health through Women Healers | India (Tribal regions, Tamil Nadu) | Historical & Contemporary | Elderly women and midwives serve as primary care providers in rural Siddha communities, offering gynecological treatments and childbirth support with herbal knowledge in absence of modern facilities. | (Benefitting from a Tribal Community’s Symbiotic Relationship with Nature: The Healing System Practiced by Irula Women – Tamil Nadu – Tribal Cultural Heritage in India, n.d.) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).