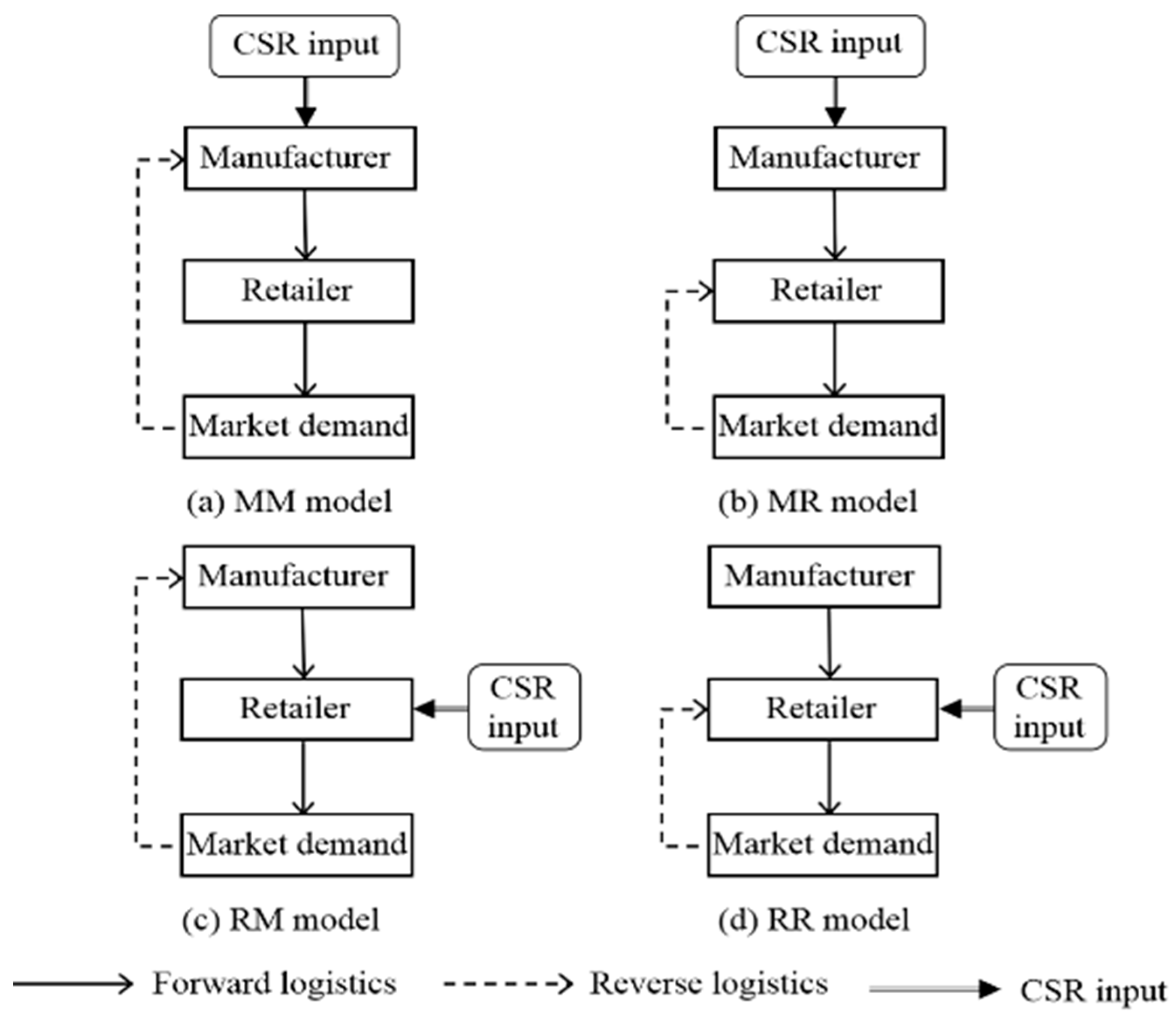

1. Introduction

With the general enhancement of people’s awareness of environmental protection, in order to deal with the environmental pollution caused by a large number of waste products, countries in the world have issued laws and regulations on waste product recycling, the environmental directives in the European Union (EU) [

1,

2] and Japan [

3] have been introduced earlier. Other countries, such as the United States, advocate that enterprises actively carry out recycling activities for used and end-of-life products and set up convenient recycling facilities to increase consumer participation in their recycling activities [

4]. The Chinese government also issued relevant guidance encouraging local authorities to accelerate the development of the waste recycling industry [

5]. In the process of recycling waste products, although the manufacturers currently handle the product recycling labor in the majority of industries, for example, Apple Inc. engages in self-recycling by issuing an announcement of trade-in through its official website, new participants in closed-loop supply chain (CLSC) are beginning to enter the collecting industry. For example, the retailer [

6] are also growing more enthusiastic about gathering the waste, Kodak, such as, entrusts the recycling of its disposable cameras to some large retailers and compensates them for the costs incurred in the recycling process through fixed payments.

In recent years, under the influence of government regulations and consumer preferences, more and more enterprises have begun to pay attention to corporate social responsibility (CSR) while pursuing profits. For example, the Guiding Opinions on the Fulfillment of Social Responsibilities by Central Enterprises issued by the Chinese government provides provisions and guidance for the disclosure of CSR by central enterprises, and requires enterprises to publish CSR reports every year since 2012. As a matter of fact, a global poll by Ernst & Young in 2002 revealed that 94% of corporations believed that adopting CSR behavior might have a positive impact on businesses [

7]. Meanwhile, in the real operation of enterprises, because the retailers are closer to consumers and have more abundant and accurate sales data, they have a better understanding of the demand market than the manufacturers, so it is easy to cause information asymmetry between the manufacturers and retailers [

8]. For example, retailers such as Walmart can obtain more accurate information about demand than manufacturers through rich consumption data.

Based on this, in the case of asymmetric market demand information of manufacturers, it is of great theoretical significance and practical value to discuss CSR input and recycling decision-making of member enterprises of CLSC for promoting environmental protection and sustainable development.

In view of the shortcomings and gaps in the above studies, we focus on the following three questions: First, how does the sensitivity coefficient of consumer CSR input affect the CLSC members and the overall operation? Second, how does the asymmetric demand information of manufacturer affect the profits and recycling strategies of CLSC members? Third, under the asymmetric market demand information of manufacturer, what is the best CSR input and recycling strategy for CLSC?

The following are the primary innovations in our paper:

(1) In the case of asymmetric demand information, the decision-making models in CLSC when both the manufacturer and retailer to carry out CSR input and recycling are constructed, and the influence of different CSR input strategies on the operation of CLSC are analyzed.

(2) The impact mechanism of consumer CSR input sensitivity coefficient and manufacturer demand information asymmetry on the product pricing, waste product recycling rate, CSR input level and performance of CLSC are revealed.

(3) The optimal CSR input and recycling channel selection strategy for CLSC under asymmetric demand information are established.

The remaining sections of our paper are structured as follows: In Part 2, we review the pertinent literature. We introduce the pertinent hypotheses and symbols used of our paper in Part 3. In Part 4, we establish game models and solve the optimal equilibrium results. We analyze the equilibrium results in Part 5. In Part 6, we carry out numerical simulation analysis. We present the key conclusions along with suggestions for additional research in Part 7.

5. Equilibrium Result Analysis

Property 1.

In the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, under the MM model, it satisfies: , , , , , , , .

Property 1 shows that in the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, when the manufacturer is responsible for CSR input and recovers by herself, the manufacturer’s CSR input level, waste product recycling rate, unit product wholesale price and sales price, and market demand are all positively correlated with the sensitivity coefficient of consumers’ CSR input, and the increase of the sensitivity coefficient of consumers’ CSR input is conducive to increase the profits for the manufacturer and retailer.

In fact, the increase in CSR input sensitivity coefficient of consumers not only prompts the manufacturer to increase CSR input level, but also increases wholesale prices, which can make up for the loss caused by CSR input. At the same time, the increase in wholesale prices will also lead retailers to increase sales prices, but it will not offset the positive effect of increasing consumer CSR sensitivity coefficient and CSR input level on market demand. Therefore, market demand will increase, which will improve the profits of the manufacturer and retailer, and enhance the enthusiasm of the manufacturer to recycle waste products and the recycling rate of waste products. Therefore, from the perspective of the government and enterprises, continuous cultivation and guidance of consumers’ CSR input sensitivity is one of the effective means to improve the recycling rate of waste products and achieve environmental protection.

Property 2.

In the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, under the MR model, it satisfies: , , , , , , , .

Property 2 shows that in the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, when the manufacturer is responsible for CSR input and the retailer recycles, the manufacturer’s CSR input level, waste product recycling rate, unit product wholesale price and selling price, market demand, and the profits of the manufacturer and retailer are all positively correlated with the sensitivity coefficient of consumers’ CSR input.

It can be seen from property 2 that with the increase of the CSR input sensitivity coefficient of consumers, the CSR input level of manufacturer, the recycling rate of waste products, the wholesale and selling price of unit product, the market demand, and the profits of the manufacturer and retailer all increase. In fact, the greater the CSR input sensitivity coefficient of consumers, it means that consumers will be more willing to buy the products of CSR enterprises, so enterprises will be motivated to respond to consumers’ purchasing behavior by increasing the level of CSR input, so as to form a good positive cycle. At the same time, the increase in CSR input level of enterprises will also bring corresponding cost expenditure. Therefore, enterprises will increase revenue by appropriately raising product prices on the one hand, and increase the recycling rate of waste products on the other hand to reduce production costs. As prices rise in tandem with demand, both the manufacturer and retailer gain more. Therefore, the increase of consumers’ CSR input sensitivity coefficient can indirectly promote enterprises’ CSR input level, increase the recycling rate of waste products, and improve the overall performance of member enterprises and CLSC system.

Property 3.

In the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, under the RM model, it satisfies: , , , , , , , .

Property 3 shows that in the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, when the retailer is responsible for CSR input and the manufacturer recycles, with the increase of consumers’ CSR input sensitivity coefficient, the retailer’s CSR input level, recycling rate of waste products, selling price and market demand will all increase, while the wholesale price of unit product will decrease, and the profits of the manufacturer and retailer will also increase all of them increase with the increase of the sensitivity coefficient of consumer CSR input.

It can be seen from property 3 that the increase of CSR input sensitivity coefficient of consumers not only promotes the retailer to increase CSR input level, but also increases consumers’ willingness to buy products of enterprises with CSR input behavior. Therefore, while promoting the increase of product selling price, the manufacturers is forced to reduce wholesale price. Therefore, the increase of CSR input sensitivity coefficient of consumers is more conducive to CSR inputs benefit. The increase in sales price will not offset the positive effect on market demand brought by the increase in CSR input level and the increase in consumers’ purchase intention. Therefore, market demand will increase, which will improve the profits of the manufacturer and retailer, and increase the enthusiasm of the manufacturer to recycle waste products and the recycling rate of waste products.

Property 4.

In the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, under the RR model, it satisfies: , , , , , , , .

Property 4 shows that in the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, when the retailer is responsible for CSR input and recycling, with the increase of consumers’ CSR input sensitivity coefficient, the retailer’s CSR input level, recycling rate of waste products, selling price and market demand will all increase, while the wholesale price of unit products will decrease, and the profits of both manufacturer and retailer will be equal. The sensitivity coefficient of CSR input increases with consumers.

It can be seen from property 4 that the situation in which the retailer is responsible for CSR input and recycling is similar to property 3. The increase of consumers’ CSR sensitivity coefficient is beneficial to the improvement of CSR input level, recycling rate of waste products and overall performance of CLSC system.

Property 5.

In the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, under the MM model, it satisfies: , , , , , , . , when , , when .

Property 5 shows that in the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, when the manufacturer is responsible for CSR input and recycling, the market demand will increase with the increase of the certain part of the manufacturer’s forecast market capacity, but the wholesale price, CSR input level, recycling rate of waste products, and selling price will all decrease. With the increase of the determining part of the market capacity of the manufacturer’s forecast, the retailer’s profit increases, and the manufacturer’s profit reaches the maximum when .

As can be seen from property 5, in the case that the manufacturer is responsible for CSR input and recycling, when , the market capacity predicted by the manufacturer is equal to the real market capacity, that is, the manufacturer can accurately predict the real market capacity information market at this time, and the profits of manufacturer, retailer and the overall under the asymmetry of demand information are equal to the profits under the symmetry of market demand information. Therefore, the equilibrium result when can be taken as the equilibrium result under the market demand information symmetry. When , the market demand and the overall profit of the CLSC system under the asymmetric demand information are larger. However, under the asymmetric demand information, the wholesale price, selling price, CSR input level, waste product recycling rate and manufacturer’s profit are all lower. When , the market demand information is asymmetric, the profits of manufacturer and retailer are smaller than that of market demand information is symmetric. However, under the asymmetric demand information, the wholesale price, sales price, CSR input level and waste product recycling rate are higher.

Property 6.

In the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, under the MM model, it satisfies: , , , , , , .

Property 6 shows that in the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, when the manufacturer is responsible for CSR input and the retailer recycles, the market demand and recycling rate of waste products will increase with the increase of the manufacturer’s prediction of market capacity, but the wholesale price, CSR input level and sales price will all decrease. Retailer’s profit rise as manufacturer’s forecast increase the portion of the market that determines capacity. Due to the complexity of the partial derivative analysis of manufacturer’s profit on its market forecast capacity, this paper will further explore in the numerical simulation part.

As can be seen from property 6, in the case that the manufacturer is responsible for CSR input and recycling, when , compared with market demand information symmetry (that is, when ), the overall profit of market demand and CLSC system under asymmetric demand information is larger. However, under the asymmetric demand information, the wholesale price, sales price, CSR input level and waste product recycling rate are all lower. When , compared with market demand information symmetry (that is, when ), the overall profit of market demand and CLSC system under asymmetric demand information is lower. However, under the asymmetric demand information, the wholesale price, sales price, CSR input level and waste product recycling rate are all higher.

Property 7.

In the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, under the RM model, it satisfies: , , , , , , . , when , , when .

Property 7 shows that when the manufacturer’s demand information is asymmetric, the market demand and CSR input level will increase with the increase of the certain part of the manufacturer’s forecast market capacity, but the wholesale price, waste product recycling rate and selling price will all decrease. With the increase of the determining part of the market capacity of the manufacturer’s forecast, the retailer’s profit increases, and when , the manufacturer’s profit reaches the maximum.

It can be seen from property 7 that the retailer is responsible for CSR input and the manufacturer recycles similar to Property 5. The asymmetric demand information of the manufacturer will reduce her own profit. When the market forecast capacity of manufacturer is higher than the real market capacity, it is conducive to increasing the profit of retailer. On the contrary, it will reduce the profit of retailer.

Property 8.

In the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, under the RR model, it satisfies: , , , , , , .

Property 8 shows that in the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, when the retailer is responsible for CSR input and recycling, the market demand, CSR input level and waste product recycling rate will increase with the increase of the manufacturer’s market forecast capacity, but the wholesale price and selling price will decrease. As the manufacturer increase the capacity determination part of the market forecast, the retailer’s profit increase. Due to the complexity of the partial derivative analysis of manufacturer’s profit on its market forecast capacity, this paper will further explore it in the numerical simulation part.

It can be seen from property 8 that the situation in which the retailer is responsible for CSR input and recycling is similar to property 6. Compared with the case of information symmetry, when the manufacturer’s predicted market capacity is higher than the true market capacity, the CSR input level, waste product recycling rate, market capacity and the overall performance of CLSC system are all greater.

It can be seen from property 5-property8 that the retailer’s profit increases with the increase, and when , the retailer’s profit at this time is just equal to the profit under the symmetry of market demand information. Therefore, , , it can be concluded that when the market forecast capacity of the manufacturer is higher than the real market capacity, it is conducive to increasing the retailer’s profit, and vice versa. That is, when the manufacturer’s market forecast capacity is higher than the real market capacity, it is conducive to increasing the retailer’s profit, and vice versa.

Proposition 1.

In the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, under four different situations, it satisfies: , .

Proposition 1 shows that the level of CSR input is highest when the manufacturer is responsible for CSR input and recycling, and the level of CSR input is lowest when the retailer is responsible for CSR input and recycling. When the retailer is responsible for CSR input and the manufacturer recycles, the recycling rate of used products is the highest, and when the manufacturer is responsible for CSR input and the retailer recycles, the recycling rate of used products is the lowest.

The above research conclusions reveal that regardless of whether the manufacturer or the retailer is responsible for CSR input, the recycling rate of the manufacturer is higher when the manufacturer is responsible for the recycling of waste products, which is because the asymmetric information demand of the manufacturer leads to its lower profit in the forward supply chain, and the manufacturer has stronger motivation to increase the enthusiasm of recycling waste products, which is obviously conducive to its own recycling and remanufacturing of waste products Get more profit. Therefore, in the CLSC with asymmetric demand information of manufacturer, the operation mode that the manufacturer is responsible for the recycling of waste products is more effective. Based on information symmetry and without considering CSR input of enterprises, (Savaskan et al. [

9] and Hong et al. [

45]) compared the difference in recycling effect between manufacturer recycling and retailer recycling in CLSC, and pointed out that retailer recycling mode is better than manufacturer recycling mode. However, in the case of asymmetric demand information and CSR input of the manufacturer or the retailer, the research shows that compared with the retailer recycling mode, the recycling effect of waste products is better when the manufacturer is responsible for recycling herself. This also indicates that the asymmetry of demand information and the difference of CSR input mode are one of the important factors affecting the selection of recycling channels in CLSC.

Proposition 2.

In the CLSC with asymmetric demand information, under four different situations, it satisfies: .

Proposition 2 shows that the market demand is greatest when the retailer is responsible for CSR input and the manufacturer recycles, while the market demand is minimum when the manufacturer is responsible for CSR input and the retailer recycles. Regardless of whether the manufacturer or the retailer is responsible for CSR input, the market demand is greater when the manufacturer recycles the used products. In the manufacturer-led CLSC, CSR input by channel follower is more conducive to increasing market demand.

6. Numerical Simulation Analysis

This section will analyze and verify the above properties and propositions through numerical simulation, and reveal the influence of consumer CSR input sensitivity coefficient on the optimal decision and profit of each member of the CLSC.

On the premise that the relevant parameter assumptions in this paper are satisfied, the values of the relevant parameters are assumed to be

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

(Liu et al. [

7]). According to the relevant research results of this paper, the specific simulation results are shown in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

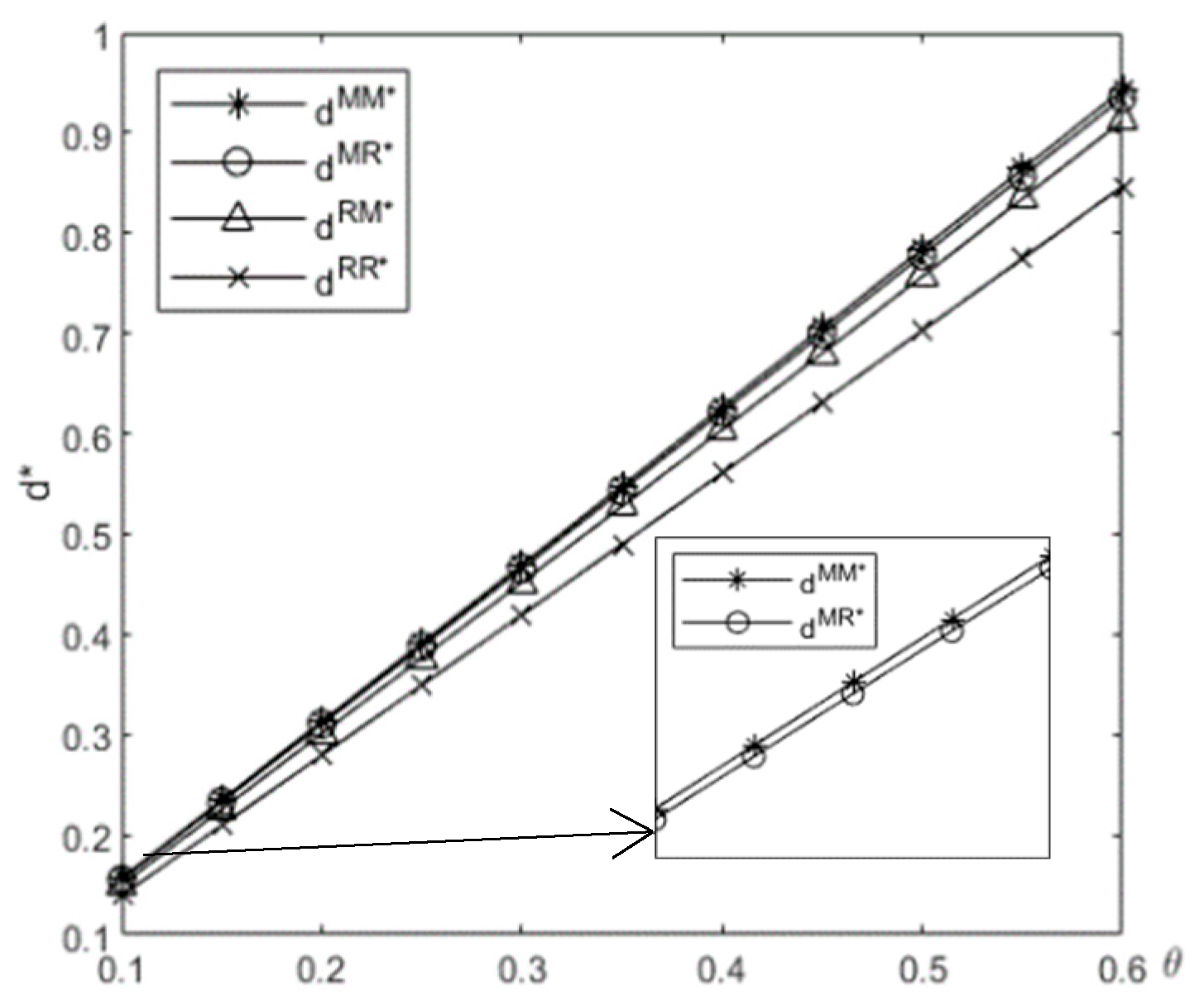

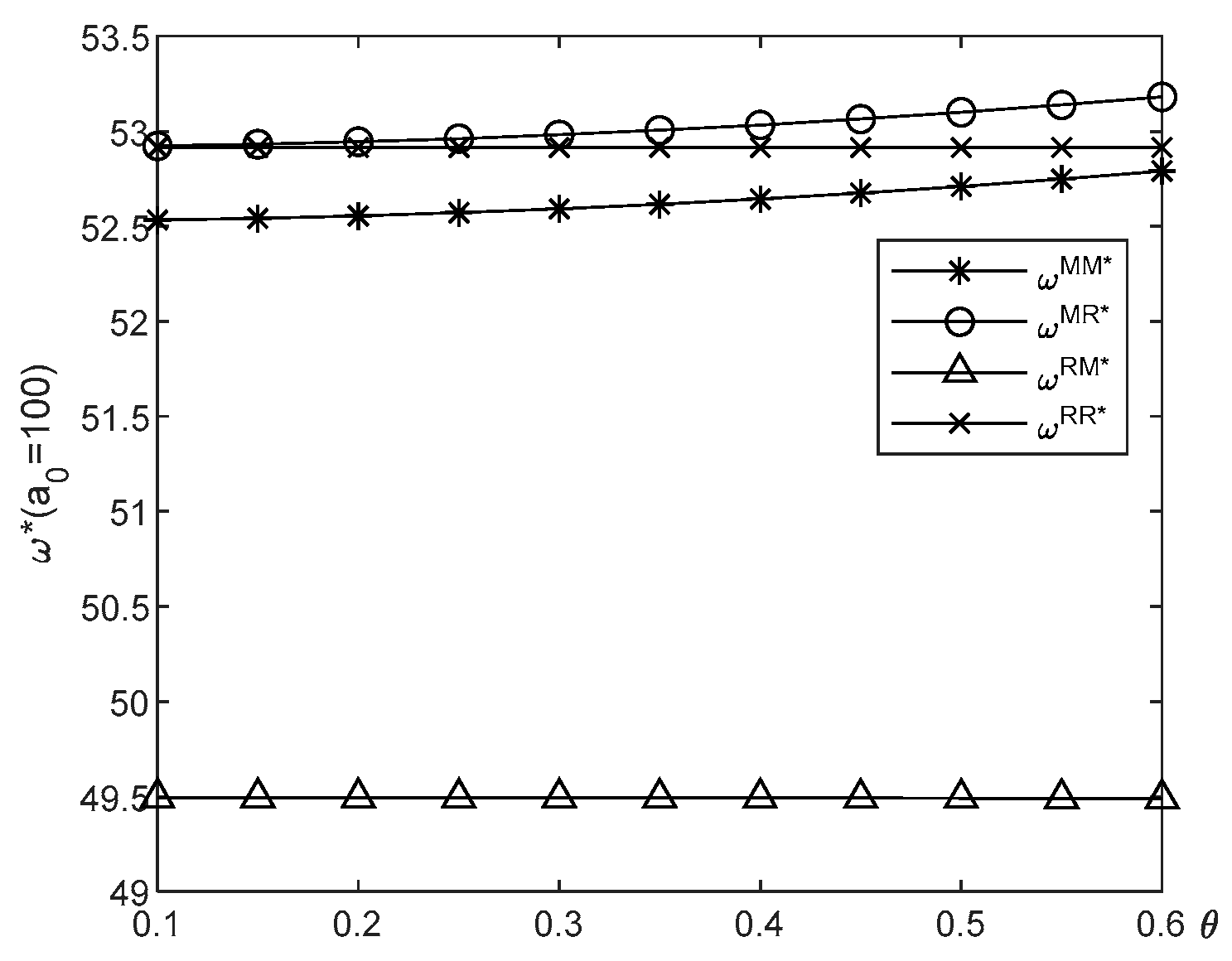

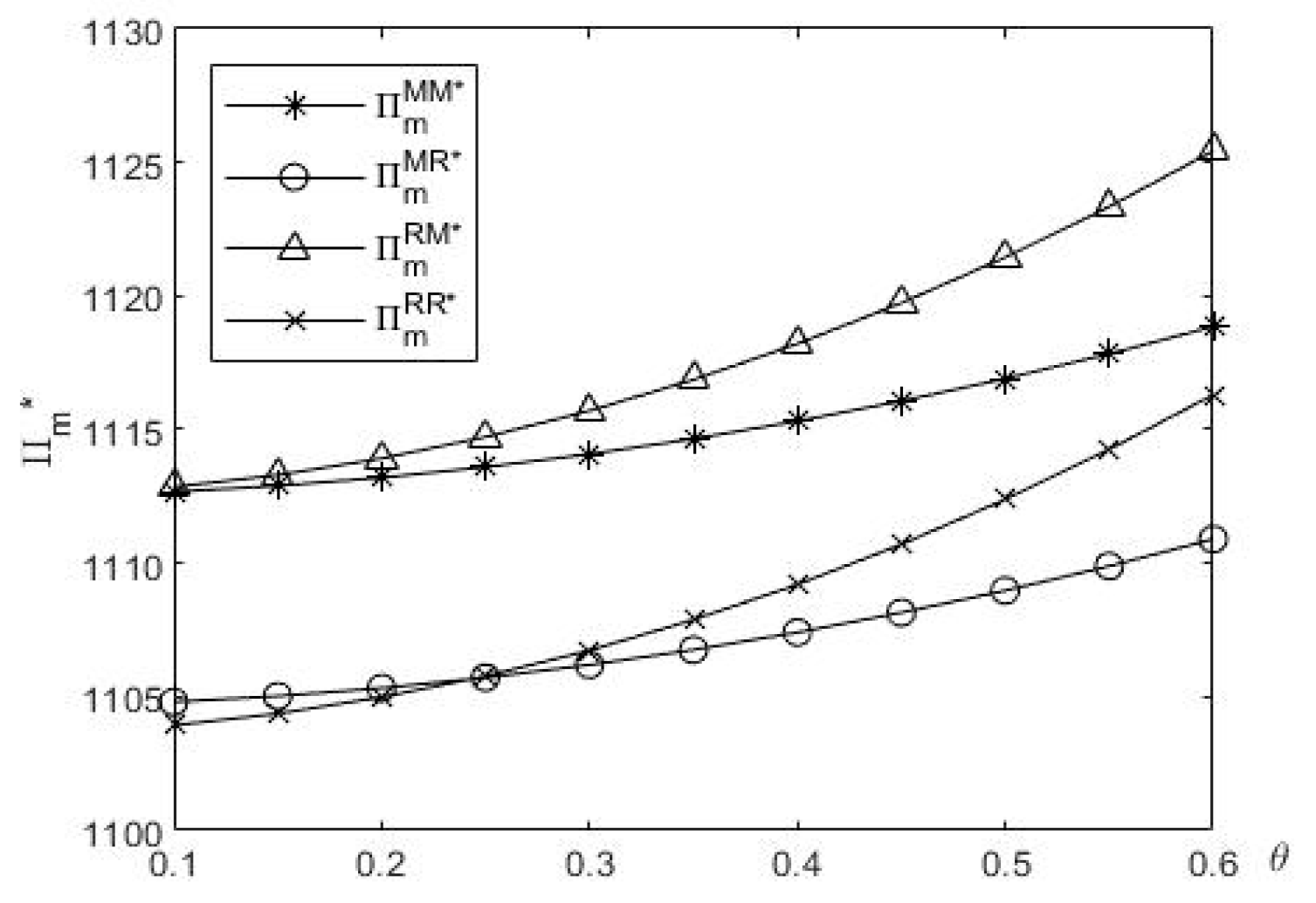

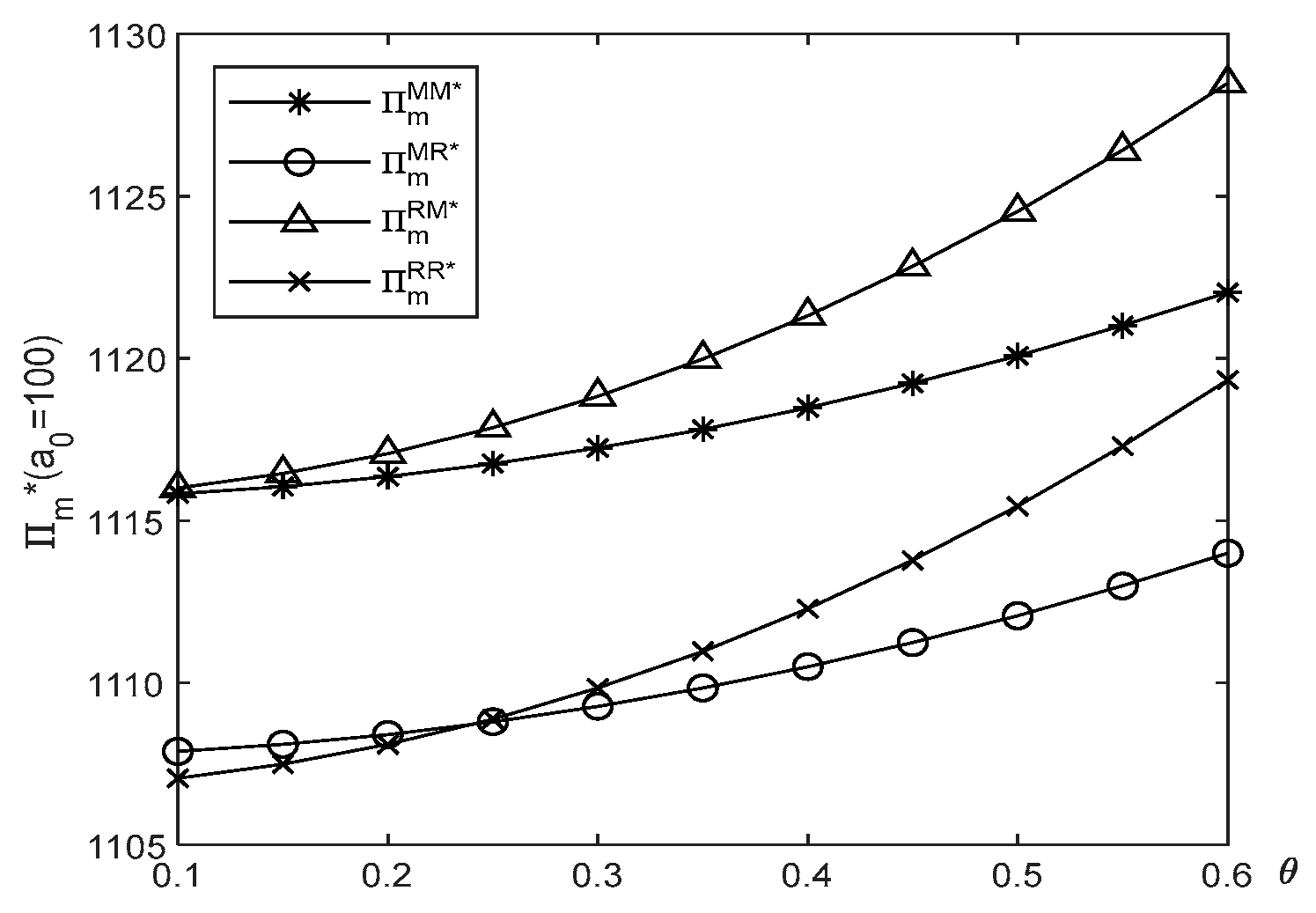

As can be seen from

Figure 2, under the four different situations, the CSR input level increases with the increase of consumers’ CSR sensitivity coefficient, and meets

. Since the highest product selling price that consumers are willing to pay is related to the sensitivity coefficient of CSR input and the level of CSR input is increasing, both the manufacturer and retailer have stronger motivation to increase the level of CSR input to increase his own profit, which also verifies the relevant conclusions of proposition 1. Counterintuitively, it can be seen from

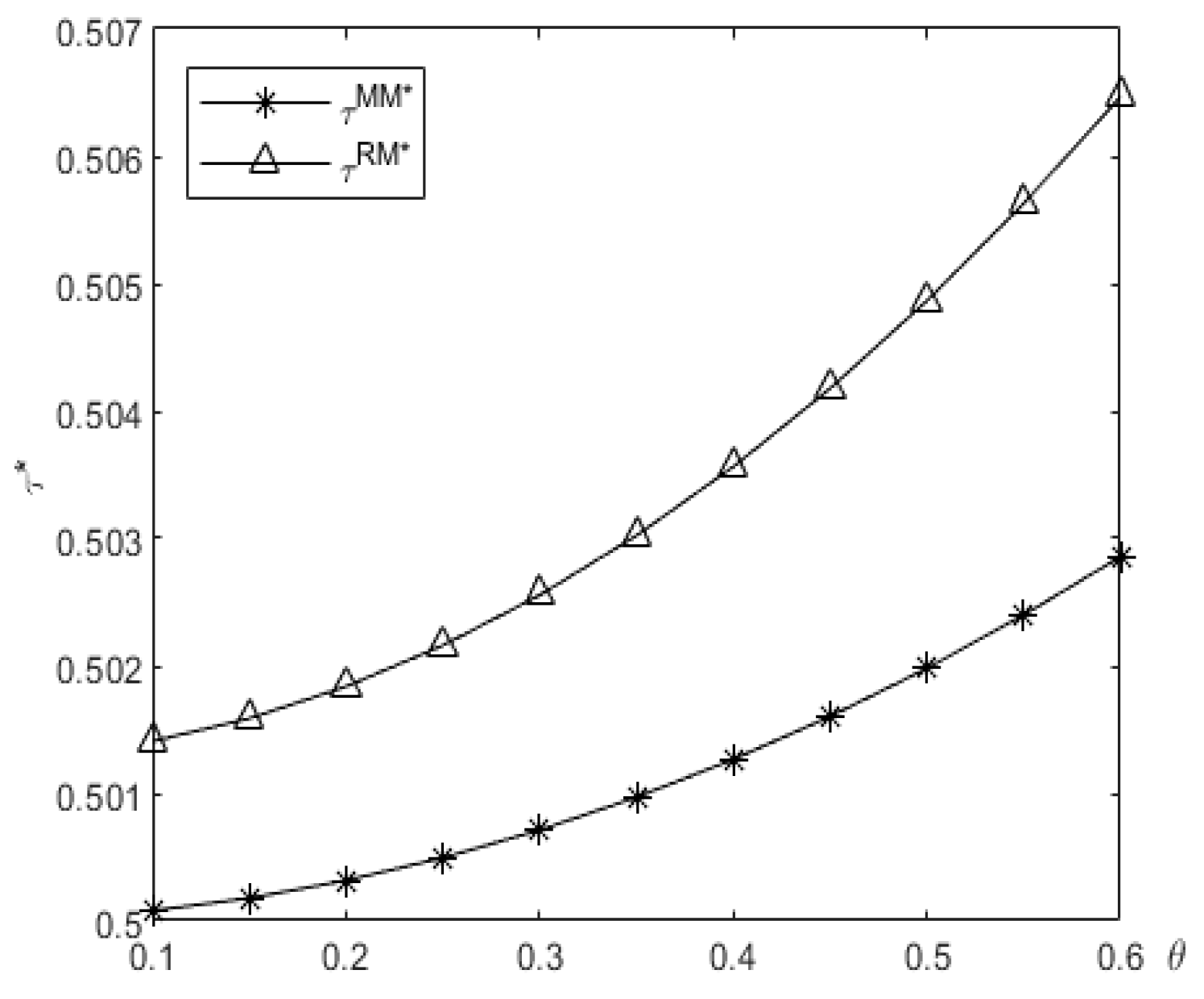

Figure 3 and

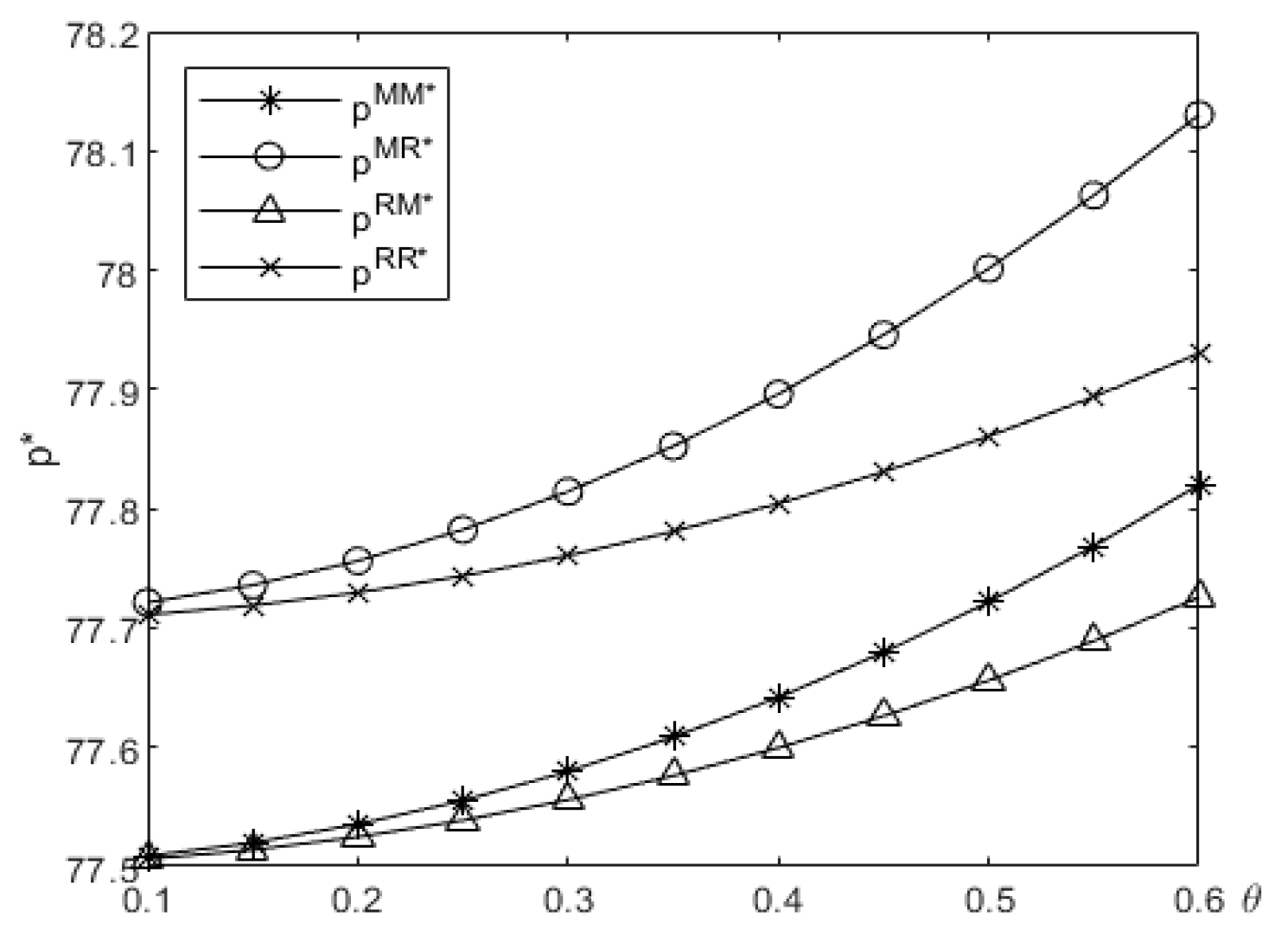

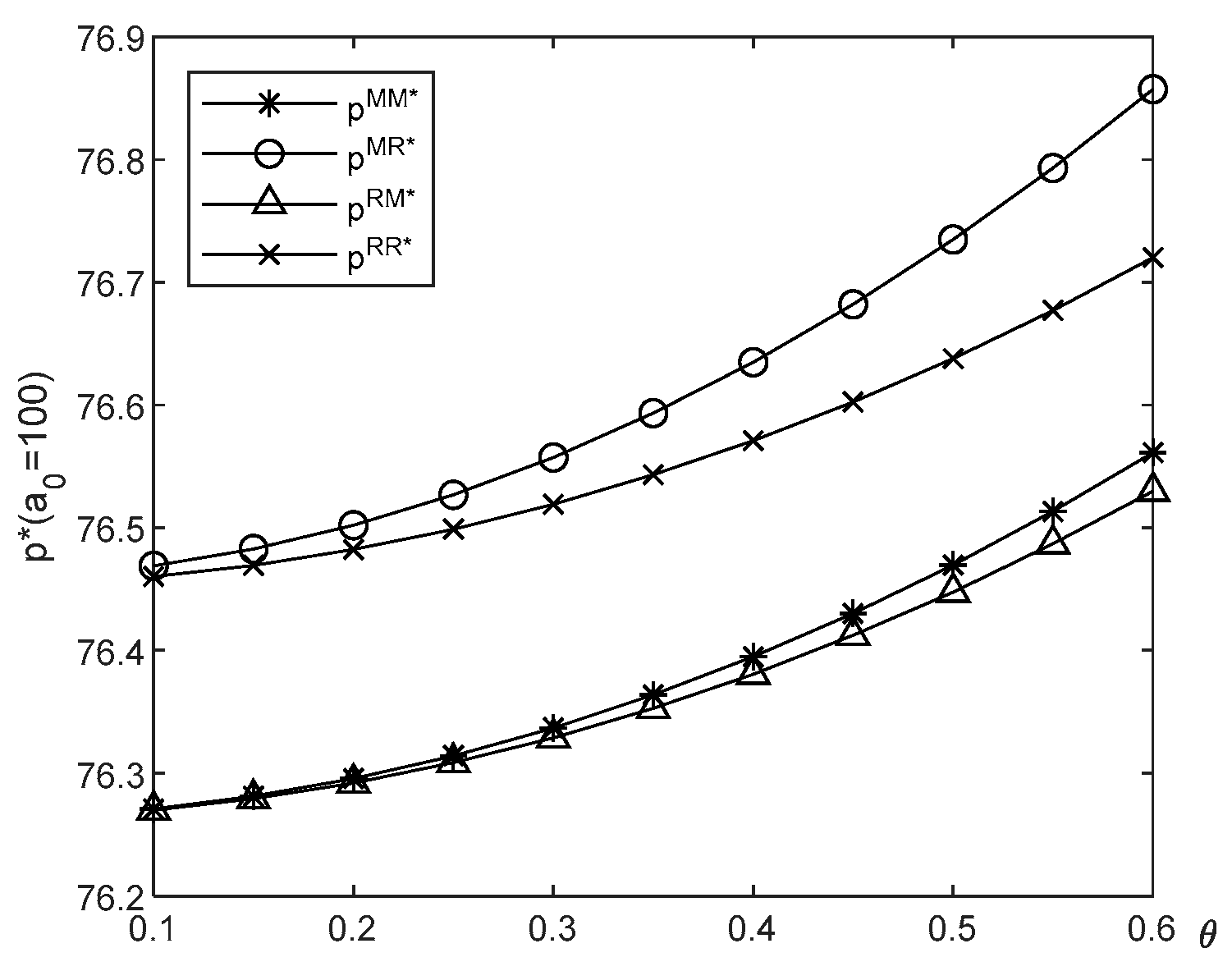

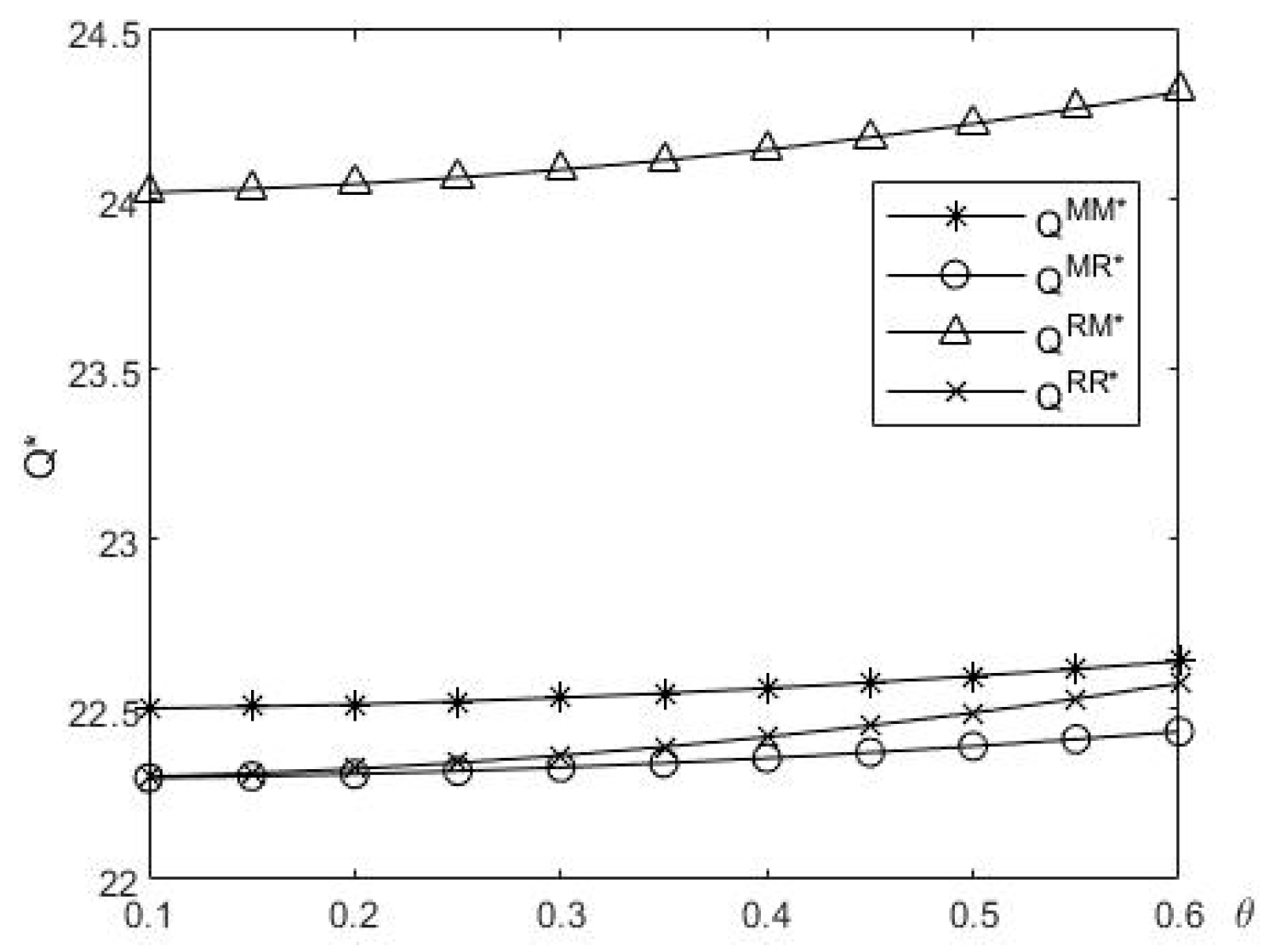

Figure 4 that the recycling rate of waste products by the manufacturer is higher than that by the retailer. In the case of information symmetry, many previous studies have pointed out that "because retailers are closer to consumers than manufacturers, it is better for manufacturers to be responsible for recycling by retailers", while this paper shows that the demand information of the manufacturer is incorrect. In this case, whether the manufacturer or the retailer is responsible for CSR input, the recycling effect by the manufacturer is better, which also validates the relevant conclusions of proposition 1.

For

,

without analytical solution comparative analysis, add a set of data with

and draw

Figure 6 and

Figure 8. By adding a set of data for comparison, it can be found that the change of

does not change the trend of graph change and the relative size relationship. From

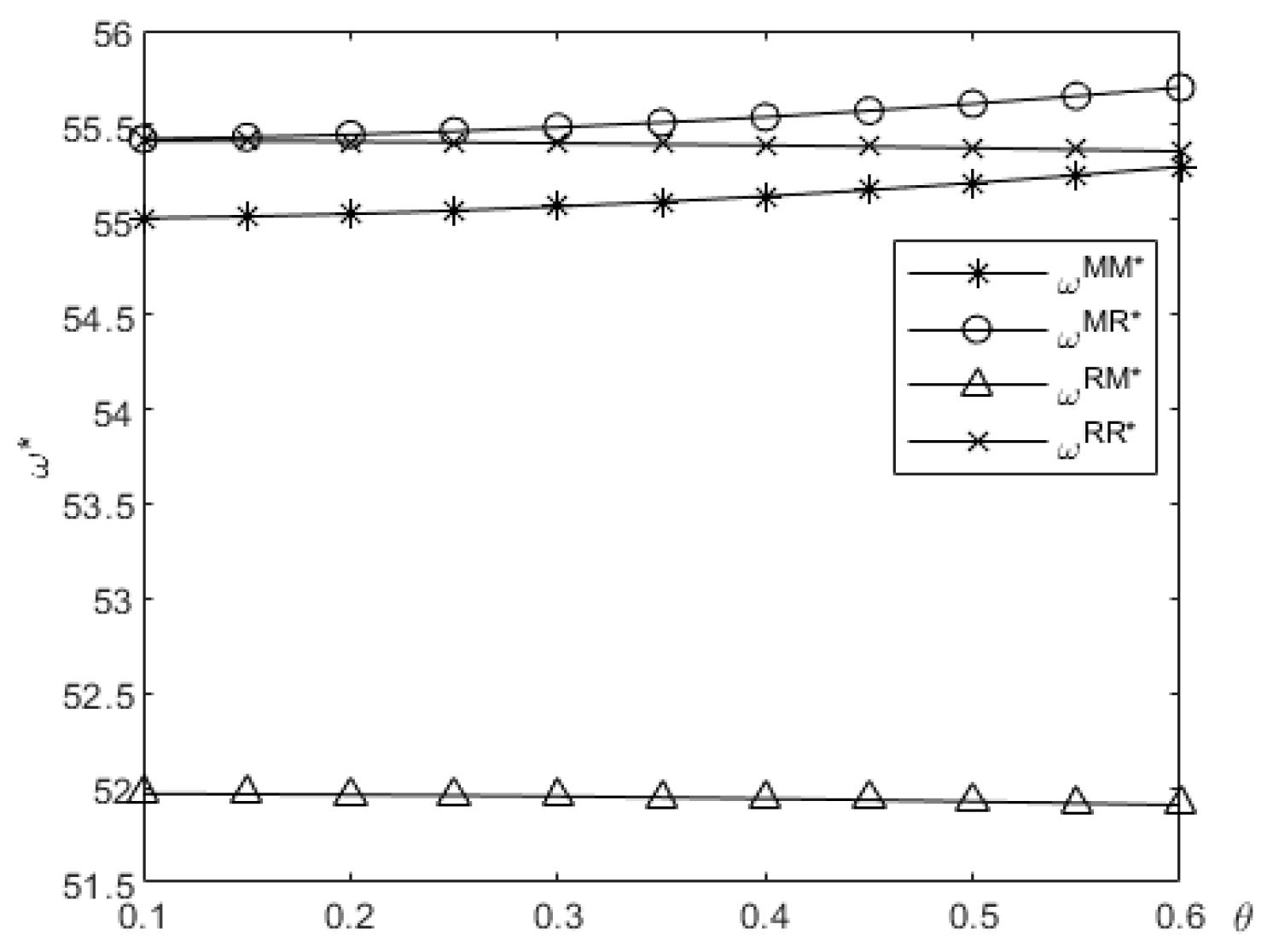

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, it’s clear that

, and with the increase of consumers’ CSR input sensitivity coefficient, CSR input by the manufacturer is conducive to increasing wholesale prices, thus making up for the losses caused by CSR input. On the contrary, when the retailer makes CSR inputs, the manufacturer will reduce wholesale prices to make up for the losses caused by retailer’s CSR input. This also confirms the relevant conclusion of property 3. As can be seen from

Figure 7 and

Figure 8,

, and with the increase of consumers’ CSR sensitivity coefficient, the sales price of new products will increase in four different situations. However, when the retailer is responsible for CSR input, the sales price will increase faster, because when the retailer is responsible for CSR input, they will increase the sales price to offset the loss caused by CSR input, while when the manufacturer is responsible for CSR input, the manufacturer will increase the sales price. The loss caused by CSR input will be offset by increasing wholesale prices, which will lead the retailer to increase the selling prices of products. As can be seen from

Figure 9,

, and the increase of CSR input sensitivity coefficient of consumers is conducive to increasing market demand. This is because with the increase of CSR input sensitivity coefficient of consumers, both the manufacturer and retailer choose to maximize his profit by increasing CSR input level, and at the same time, the increase of CSR input level will stimulate market demand.

Corollary 1. It can be seen from Figure 2, Figure 7 and Figure 9 that market demand mainly depends on sales price, while consumer CSR sensitivity coefficient and CSR input level are only secondary influencing factors on market demand.

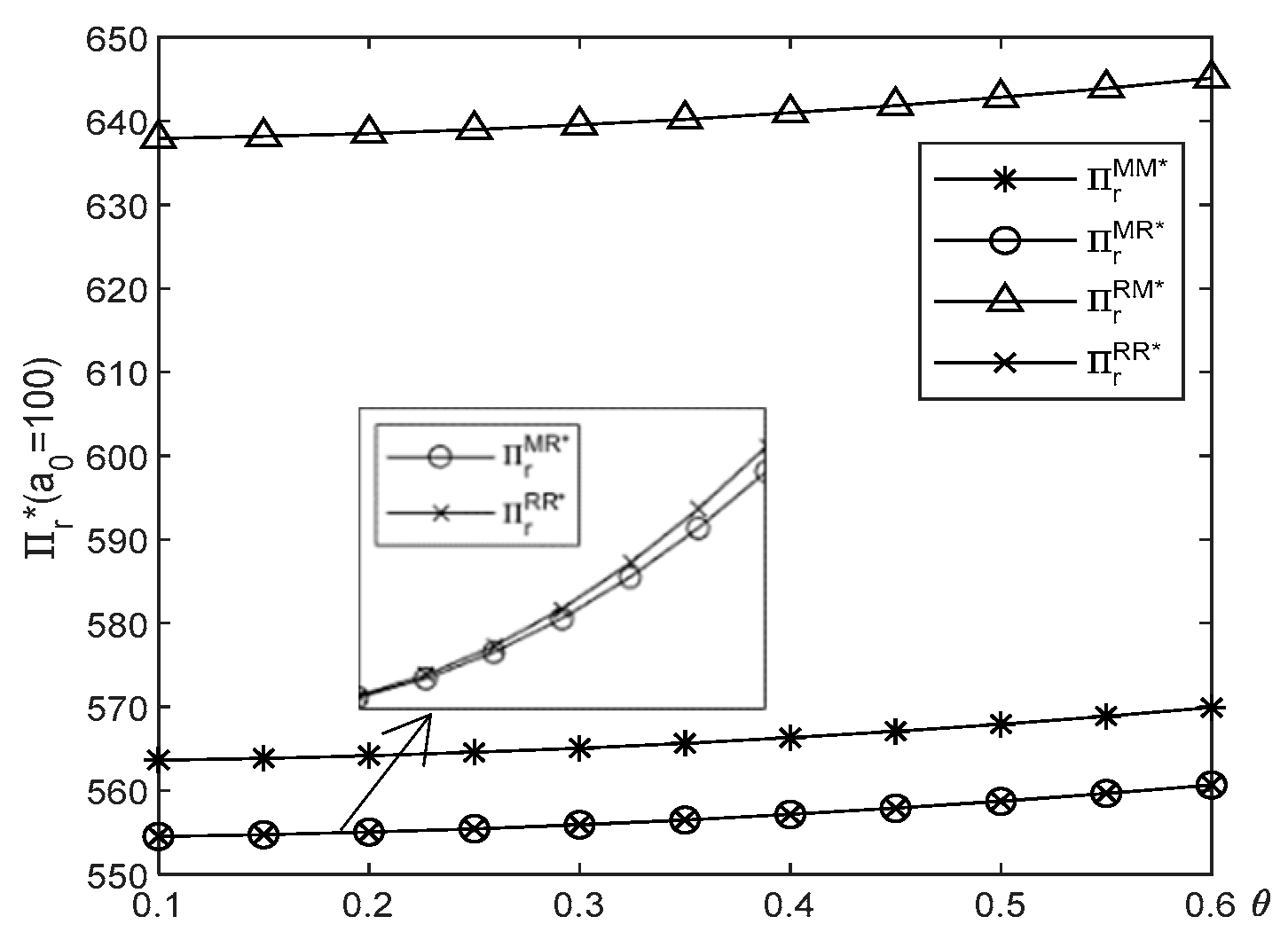

For

,

without analytical solution comparative analysis, add a set of data with

and draw Figure 11 and Figure 13. As can be seen from

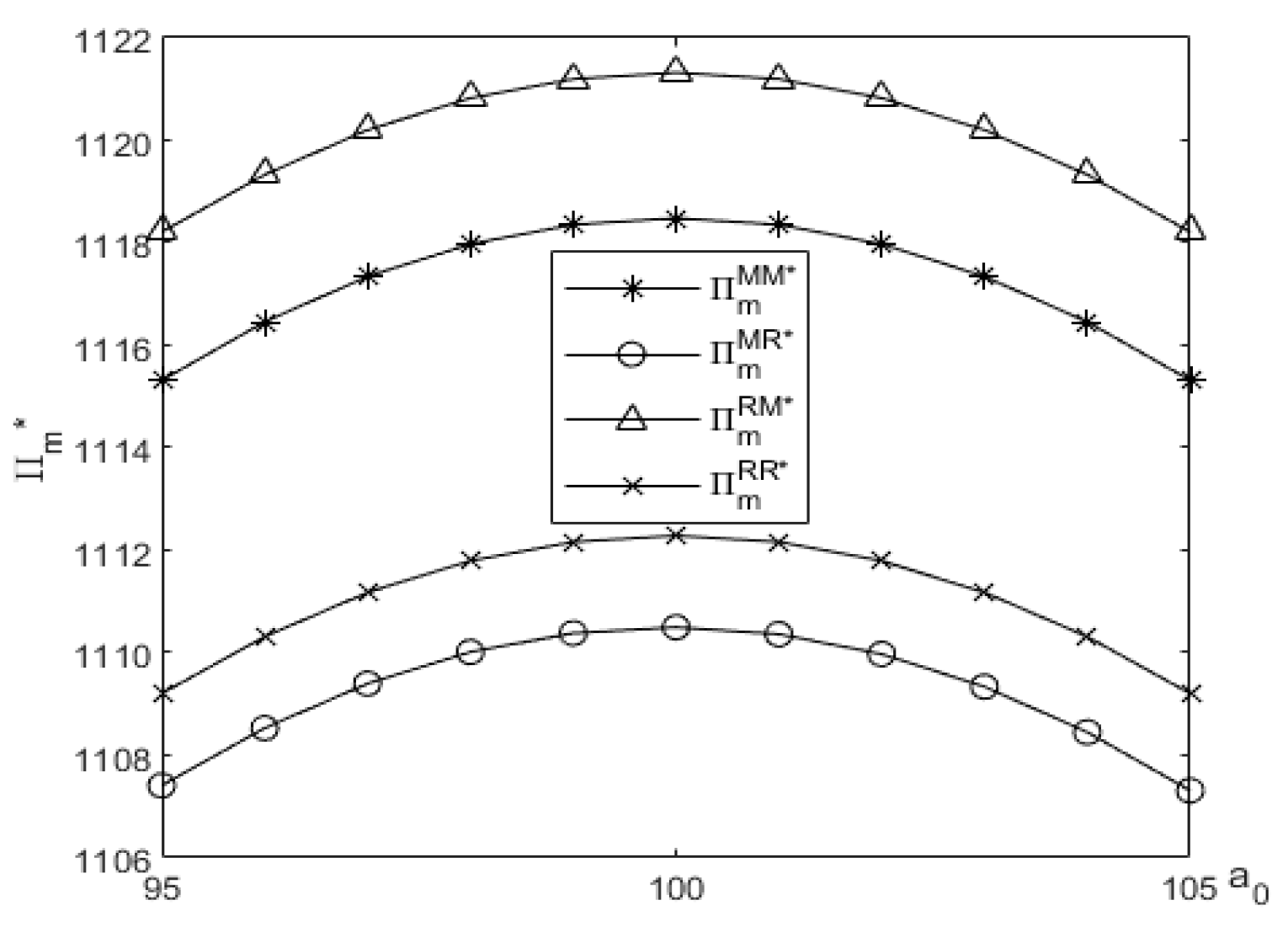

Figure 10 and

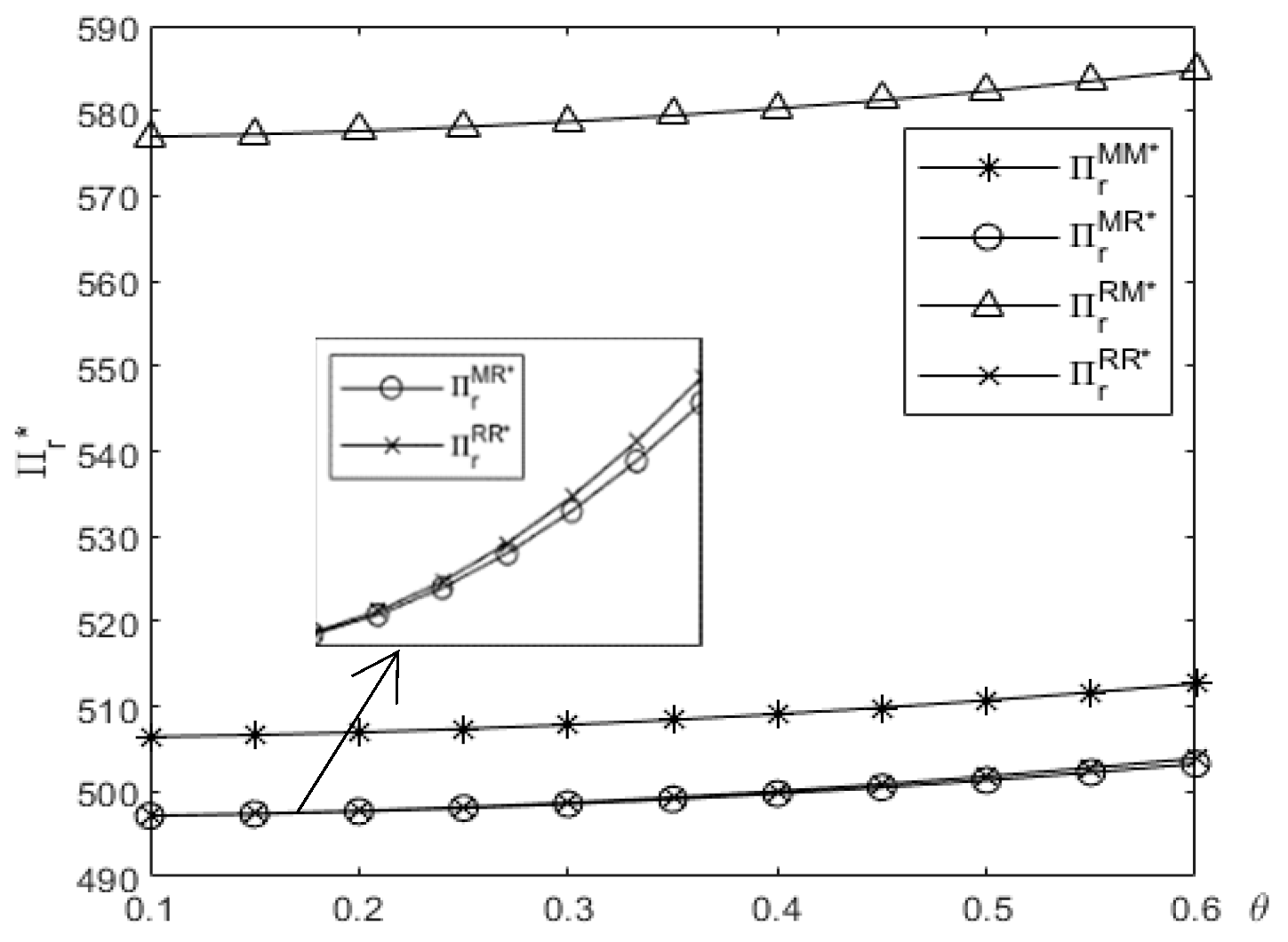

Figure 11, the recycling of waste products by the manufacturer is more conducive to maximizing her own profit, and in the four different cases, the increase of consumers’ CSR input sensitivity coefficient is conducive to the manufacturer obtaining higher profit. As can be seen from

Figure 12 and

Figure 13,

, and in any case, the increase of consumers’ CSR input sensitivity coefficient is conducive to the retailer to obtain greater profit. It can be further seen from

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 that when the retailer is responsible for the CSR input and the manufacturer recycles, it is more conducive to realizing the overall profit of the CLSC system. This also indicates that under the asymmetric manufacturer information, the manufacturer’s responsibility for recycling waste products is not only conducive to improving the recycling rate of waste products, but also conducive to increasing the overall performance of the CLSC. The channel follower’s responsibility for CSR input is conducive to increasing the market demand and the overall performance of CLSC. This also reveals that the asymmetry of the manufacturer demand information has a certain impact on the recycling channel, but has a low impact on the selection of CSR input members.

As can be seen from property 5, property 7 and

Figure 14, when the market capacity predicted by the manufacturer is equal to the real market capacity (that is, when the market demand information is symmetric), the manufacturer’s profit reaches the maximum. Therefore, when the market capacity predicted by the manufacturer is not equal to the real market capacity, the manufacturer’s profit is lower than the manufacturer’s profit under the information symmetry, so it is compared with the information symmetry. The asymmetric demand information of the manufacturer will lead to the reduction of her own profit. This also indicates that timely and accurate market demand information is particularly critical for the manufacturer. Manufacturers should constantly strengthen cooperation with retailers to improve the ability to obtain market demand information, which will help improve their own performance and maintain the stable operation of CLSC.

Proof of Theorem 1:

It can be seen from equation (2) that it is a concave function with respect to . According to the first order condition, the best feedback function of the retailer is , since the manufacturer does not know the true value of , therefore, the manufacturer can only substitute the predicted value into formula (1), it is easy to know the Hessian matrix of with respect to is . Under the assumption of scale parameter , , , , so the Hesse matrix is negative definite. According to backward induction, the equilibrium results under MM model can be obtained.

Proof of Theorem2:

The Hessian matrix of retailer profit with respect to is easily obtained from formula (4) as . With the proof of theorem 1, it is easy to obtain the Hessian matrix of manufacturer’s profit with respect to as

.

Under the assumption of scale parameter , , , so the Hessian matrix is negative definite. According to backward induction, the equilibrium result under MR Model can be obtained.

The proof process of theorem 3 and theorem 4 is similar to theorem 1 and theorem 2, which are omitted here.

Proof of Property 1:

According to theorem 1, we can easily find

, , , , .

Proof of Property 2:

According to theorem 2, it’s easy to get

,

,

,

,

.

The proof of properties 3 and 4 is similar to the proof of properties 1 and 2, and is also omitted here.

Proof of Property 5:

According to theorem 1, we can easily find

, , , , , , .

Proof of Proposition 1:

Theorem 1–Theorem 4, we can easily find

,

,

,

,

.