1. Introduction

The rapid development of industrialization and the accelerated pace of product replacement have led to the generation of numerous used products [

1]. Directly discarding them will not only cause environmental pollution but also result in significant waste of recoverable resources. As a result, the recycling and remanufacturing of used products have become a prevalent option in today’s world [

2]. As a cleaner production method, remanufacturing can not only provide appropriate revenues, economic growth, carbon emission reduction, and many new job opportunities, but also create environmental incentives for manufacturers. Many countries have therefore enacted legislation requiring manufacturers to adopt integrated green management systems and remanufacturing practices throughout the product lifecycle, from material sourcing to end-of-life recycling.

Research in the management of the CLSC has analyzed the impacts of various factors on decisions and profits. These factors include information sharing [

3,

4], environmental awareness [

5,

6], government subsidies [

7,

8], return effort or return rate [

9,

10], and contract coordination [

11,

12], among others. However, the influence of dual competition in both forward and reverse channels on the CLSC has rarely been explored. In practice, manufacturers typically sell products through multiple retailers and outsource the collection of used products to numerous recyclers.

The profitability of a manufacturer implementing recycling and remanufacturing of used products exhibits dual dependencies. It depends on both the manufacturer’s endogenous decisions and the exogenous operational decisions of retailers and third-party recyclers. However, traditional investment return theory is limited in analyzing such strategic dependence issues. Game theory, particularly Stackelberg game models, offers an effective approach to analyzing these problems. This method has been widely applied in research on the CLSC management for remanufacturing.

Therefore, this paper employs Stackelberg game theory to investigate management decisions, contract design, and the impact of competition within a CLSC comprising one manufacturer, retailers , and recyclers . The proposed model and analysis contribute to understanding three key aspects: (1) Interactions among supply chain members in a CLSC under dual competitive markets; (2) The optimal operational decisions made by these members; and (3) The optimal profits achieved through decisions on ordering quantities and recycling quantities. It examines the effectiveness of a linear transfer-payment contract in retail competition and recycling competition.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature. The problem description, notations and assumptions are provided in

Section 3 followed by the model formulation in

Section 4. The numerical analysis is shown in

Section 5 and the last section concludes the paper with main findings, management insights, limitations and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

In this study, the literature relevant to this text is reviewed in three ways: competition in sales channels, competition in recycling channels, and dual competition in sales channels and recycling channels in closed-loop supply chains.

2.1. Competition in Sales Channels

The presence of multiple sales entities distributing products from the same manufacturer has intensified market competition. Consequently, scholars have extensively investigated decision-making in CLSC management involving sales competition within forward supply chain. Zheng et al. [

13] and Pal and Sana [

14] examined the effects of forward-channel sales competition on dual-channel CLSCs, which comprise a manufacturer, a retailer and a collector. The manufacturer may wholesale products to the retailer or sell directly to consumers, while the collector manages used product collection. Xie et al. [

15] developed a revenue and cost sharing contract to coordinate a CLSC with dual sales channels. Zheng et al. [

16] examined manufacturers’ reverse channel choices and coordination mechanism in CLSCs with competitive dual sales channels. Wei and Zhao [

17] incorporated fuzziness into collection and remanufacturing costs, using game theory and fuzzy set theory to study optimal pricing decisions for wholesale/retail prices and remanufacturing rates in a fuzzy CLSC with retail competition. Similarly, Ke et al. [

18] addressed pricing and remanufacturing decisions in a fuzzy CLSC with one manufacturer, two competitive retailers, and one third-party collector.

2.2. Competition in Recycling Channels

In light of the competitive landscape in used product collection, scholars have explored decision-making challenges in CLSC management, building on Savaskan’s foundational models. These studies typically address recycling competition within reverse supply chains. Ranjbar et al. [

2] evaluated optimal pricing and collection decisions in a three-level CLSC under channel leadership with competitive dual-recycling channels: retailer collection and third-party collection. Shu et al. [

19] analyzed the impact of two collectors’ fairness concerns on pricing decisions and coordination. Suvadarshini et al. [

20] analyzed three return-channel structures under simultaneous influences of competition, collection efficiencies, individual rationality, and information asymmetry. Gaula and Jha [

21] studied pricing and quality improvement strategies in a CLSC with dual collection channels. To explore consumer behavior effects on competitive dual-collection supply chains, Wang et al. [

22] developed two CLSC models: (1) retailer and third-party collection, and (2) manufacturer and third-party collection. He et al. [

23] proposed a hybrid game-theoretic CLSC model with a manufacturer, a retailer, and a third-party collector, devising collection functions accommodating varying competition levels-from monopoly to duopoly and hybrid scenarios.

2.2.3. Dual Competition in Sales Channels and Recycling Channels

To better align research with real-world complexities, a limited number of scholars have investigated optimization problems in CLSCs involving both retail competition and recycling competition. Giri et al. [

24] analyzed a CLSC with two dual channels: a forward dual channel where a manufacturer sells products through traditional retail and e-tail channels, and a reverse dual channel where it collects used products for remanufacturing through third-party logistics and e-tail channels. Similarly, Zhang et al. [

1] examined the impact of sales competition and recycling competition between manufacturer and retailer on CLSC management, while considering product quality and returns. They also designed an effective revenue-sharing contract to motivate retailers’ recycling efforts. Hosseini-Motlagh et al. [

25] studied a CLSC comprising a manufacturer investing in remanufacturing and energy-saving efforts, two retailers competing in sales, and two collectors competing in used product collection, proposing an energy-saving effort and cost-tariff contract for system coordination.

In summary, previous research has enriched the theoretical foundations of CLSC management, but most studies assume bilateral or trilateral monopolies within the supply chain, overlooking the influence of competitive factors. Some literature has considered competitions in sales and recycling, but only from the perspective of competition between two same entities. In reality, however, oligopolistic markets formed by multiple retailers are common within regional context, such as the dominance of Walmart, Carrefour, CR Vanguard, and Hualian in retail sectors. Additionally, a manufacturer typically outsources used product collection to multiple professional third-party collectors. Building on existing research and drawing on Cachon’s revenue function, this paper intends to explore decisions and contract coordination in a CLSC with competition in both retail and recycling, with one manufacturer, , and , to enhance the conclusion generalizability. The contribution of this study is twofold: (1) analyzing how retail and recycling competition separately impact decisions and profits of node enterprises and the supply chain, and (2) designing a linear transfer-payment contract to perfectly coordinate such a CLSC.

3. Problem Description and Notations

We consider the CLSC consisting of one manufacturer, retailers, and third-party collectors. The manufacturer engages in dual production modes: traditional manufacturing (using new materials) and remanufacturing (using used products). The retailers submit orders to the manufacturer and sell products to consumers. The third-party collectors collect used products from consumers and supply them to the manufacturer.

Figure 1.

The proposed CLSC model.

Figure 1.

The proposed CLSC model.

The notations and their definitions used in this paper are listed in

Table 1.

The mathematical models in this analysis rest on the following assumptions:

Assumption 1.

Remanufactured products are functionally and qualitatively equivalent to new products. Consequently, the manufacturer sells both to retailers at a uniform wholesale price [

26].

Assumption 2. The manufacturer acquires used products from third-party recyclers at a uniform price. All collected products meet remanufacturing quality standards.

Assumption 3.

Retailer competition adheres to a Cournot model, with the retail price facing retailerexpressed as:

Assumption 4.

Analogously, the acquisition price by recyclertakes the form:

Assumption 5.

The manufacturer serves as the Stackelberg leader in the CLSC, with retailers and recyclers acting as followers.

Assumption 6.

All node enterprises in the CLSC are rational profit-maximizers with complete market information.

Assumption 7.

An increase in order quantity by retailer may negatively impact retailer ’s profit (i.e., ). An increase in recycling quantity by recycler may negatively impact recycler j’s profit (i.e., ).

Assumption 8.

The unsold product inventories of retailer and retailer are interchangeable (i.e., ). The recycling volumes of recycler and recycler are interchangeable (i.e.,

The profit functions of the manufacturer, retailer

, recycler

, and the CLSC can be expressed as follows:

4. The Model

4.1. Centralized Decision-Making

Centralized decision-making is modeled for a single selling period under a Cournot competition involving both sales and recycling. In the centralized system, all supply chain members are vertically integrated, and an unbiased decision-maker decides order quantities of retailers and recycling quantities of recyclers to maximize the total profit (

). The decision vectors are

and

. The corresponding decision-making problem is:

By solving the equations and , Proposition 1 is obtained.

Proposition 1.

Under the centralized decision-making, the optimal order quantities and recycling quantities are:

Substituting andinto Equation (4) yields the optimal system profit ().

Proposition 2.

Under centralized decision-making, the optimal order quantities decrease as the number of retailers increases, and the optimal recycling quantities decrease as the number of recyclers increases.

4.2. Decentralized Decision-Making

Under decentralized decision-making, the manufacturer, as the leader of the CLSC, first determines the wholesale price

of the products and the recycling price

of used products to maximize its profit. Subsequently, competitive retailers determine their order quantities based on

, and competitive recyclers determine their recycling quantities based on

, to maximize their respective profits. This decision-making problem is formulated as follows:

Using backward induction, solve and to obtain: and . Substituting and into Equation (1) and solving and , the manufacturer’s optimal decentralized wholesale price and recycling price are derived. Substituting into and into yields the optimal decentralized order quantities for retailers and recycling quantities for recyclers.

Proposition 3.

Under decentralized decision-making, the optimal wholesale price, recycling price, order quantities, and recycling quantities are:

Proposition 4.

Under decentralized decision-making, the manufacturer’s optimal wholesale price and recycling price are independent of the numbers of retailers and recyclers. The optimal order quantities decrease as the number of retailers increases. The optimal recycling quantities decrease as the number of recyclers increases.

Using , , , and , the optimal profits for the manufacturer, for retailers, and for recyclers are derived under decentralized decision-making.

4.3. Coordinated Decision-Making

Proposition 5 can be obtained by comparing with and with .

Proposition 5.

The optimal order quantities and recycling quantities in decentralized decision-making are less than those in centralized decision-making.

Proposition 5 indicates that decentralized decision-making can result in a loss of profit for the CLSC, implying that there is still room for improvement in the equilibrium profit of decentralized supply chain compared to the optimal profit of the integrated supply chain. Therefore, as the leader of the CLSC, the manufacturer can provide a cooperation contract to induce retailers and recyclers to make centralized decisions. This will maximize the profit of supply chain while ensuring that the profits of supply chain members are no less than their corresponding profits under decentralized decision-making.

Here, a linear transfer-payment contract is introduced to coordinate the CLSC. The manufacturer provides a linear transfer payment contingent on the retailer’s order quantity, defined as for , aiming to incentivize retailers to increase their order quantities. Similarly, the manufacturer provides a linear transfer payment based on the recyclers’ recycling quantities, formulated as for , aiming to incentivize recyclers to increase their recycling volumes. Furthermore, the manufacturer strategically sets the minimum order quantity and the minimum recycling amount , with depending on competing retailers’ sales capacity and determined by recyclers’ recycling capacity. To achieve coordination under this contract, the manufacturer determines the reward-penalty factors for product ordering and used product collection.

Under the linear transfer-payment contract, the profit functions of the manufacturer, competitive retailers, and recyclers are as follows:

Proposition 6.

Under the linear transfer-payment contract, the CLSC can achieve perfect coordination when,, provided that the reward-penalty factorsand

satisfy the participation constraints of the manufacturer, retailers, and recyclers.

Proof 1.

To achieve perfect coordination in the CLSC, decentralized decisions by competing retailers, on order quantities, and by recyclers, on used product recovery volumes, under a linear transfer-payment contract must align with centralized decision-making outcomes. By taking the partial derivatives of

with respect to and of with respect to , setting them equal to zero, and solving the resulting system of equations simultaneously, we obtain:

By comparing

with

and

with

, we can conclude that:

Furthermore, to coordinate the CLSC, the manufacturer’s linear transfer-payment contract must satisfy the participation constraints of all supply chain members. This can be achieved by selecting appropriate values for the reward-penalty factors and .

Therefore, when the reward-penalty factors and satisfy the participation constraints of all supply chain members, the linear transfer-payment contract achieves perfect coordination of the CLSC with competition in both retailing and recycling. □

5. Numerical Analysis

To validate the findings in

Section 4, we will perform some numerical simulations on a CLSC consisting of one manufacturer,

retailers

, and

recyclers

. The values of key parameters are set as:

,

,

,

,

and

. Using these parameters, we will analyze the changing trends in the optimal values of decision variables and in the maximum profits under decentralized and centralized decision-making scenarios as the numbers of retailers and recyclers vary.

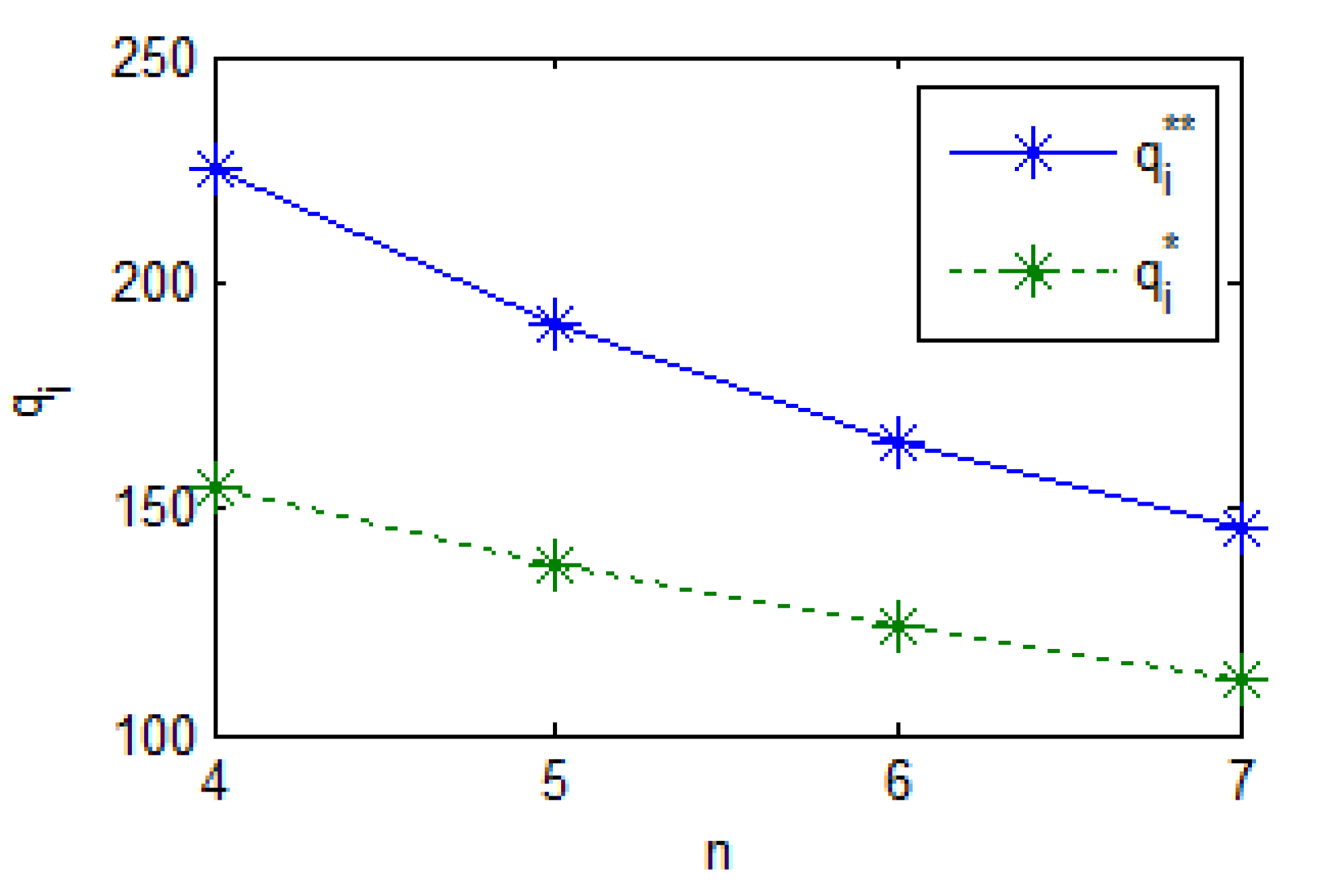

Figure 2 illustrates the variation of order quantities as

increases from 4 to 7. Three conclusions are drawn:

(1) Regardless of whether decision-making is decentralized or centralized, the optimal order quantities decrease as the number of retailers increases.

(2) Under decentralized decision-making, the optimal order quantities are consistently lower than those under centralized scenario.

(3) The gap between and gradually decreases as increases.

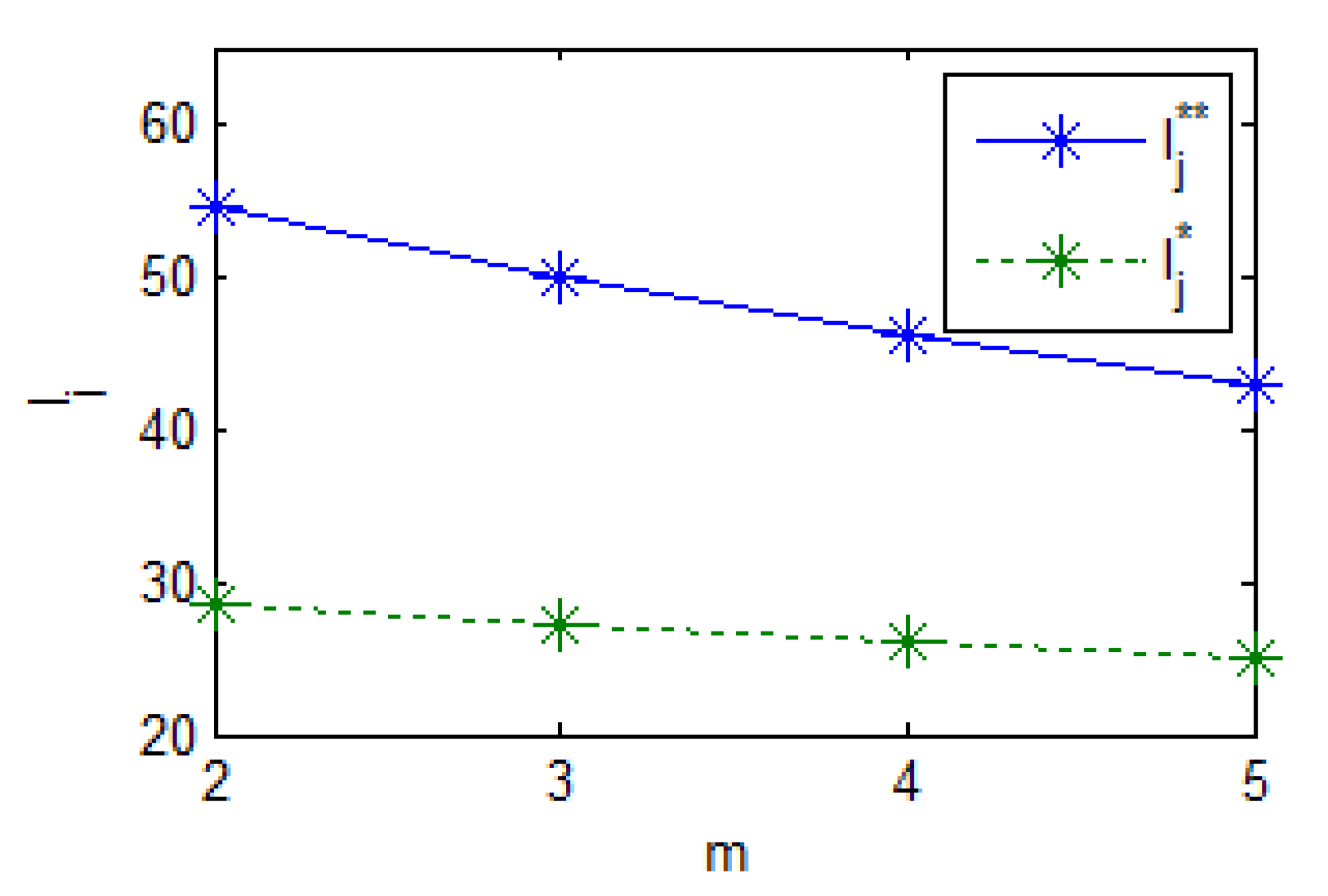

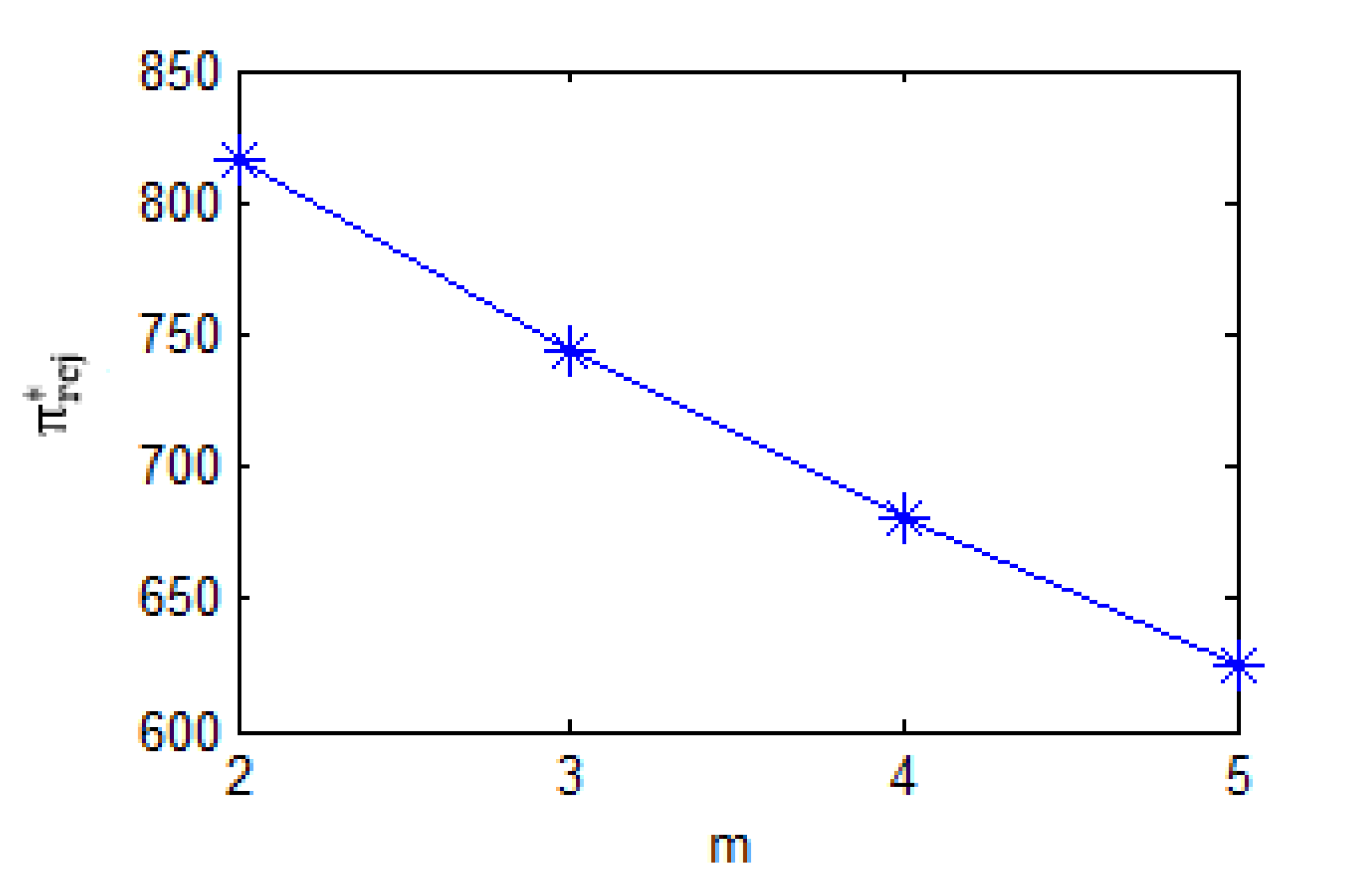

Figure 3 shows how the recycling quantities change as

increases from 2 to 5. From this figure, three key observations emerge:

(1) Under both decentralized and centralized decision-making, the optimal recycling quantities decline as increases.

(2) The optimal recycling quantities under decentralized decision-making are consistently lower than those under centralized scenario.

(3) As increases, the difference between and gradually decreases.

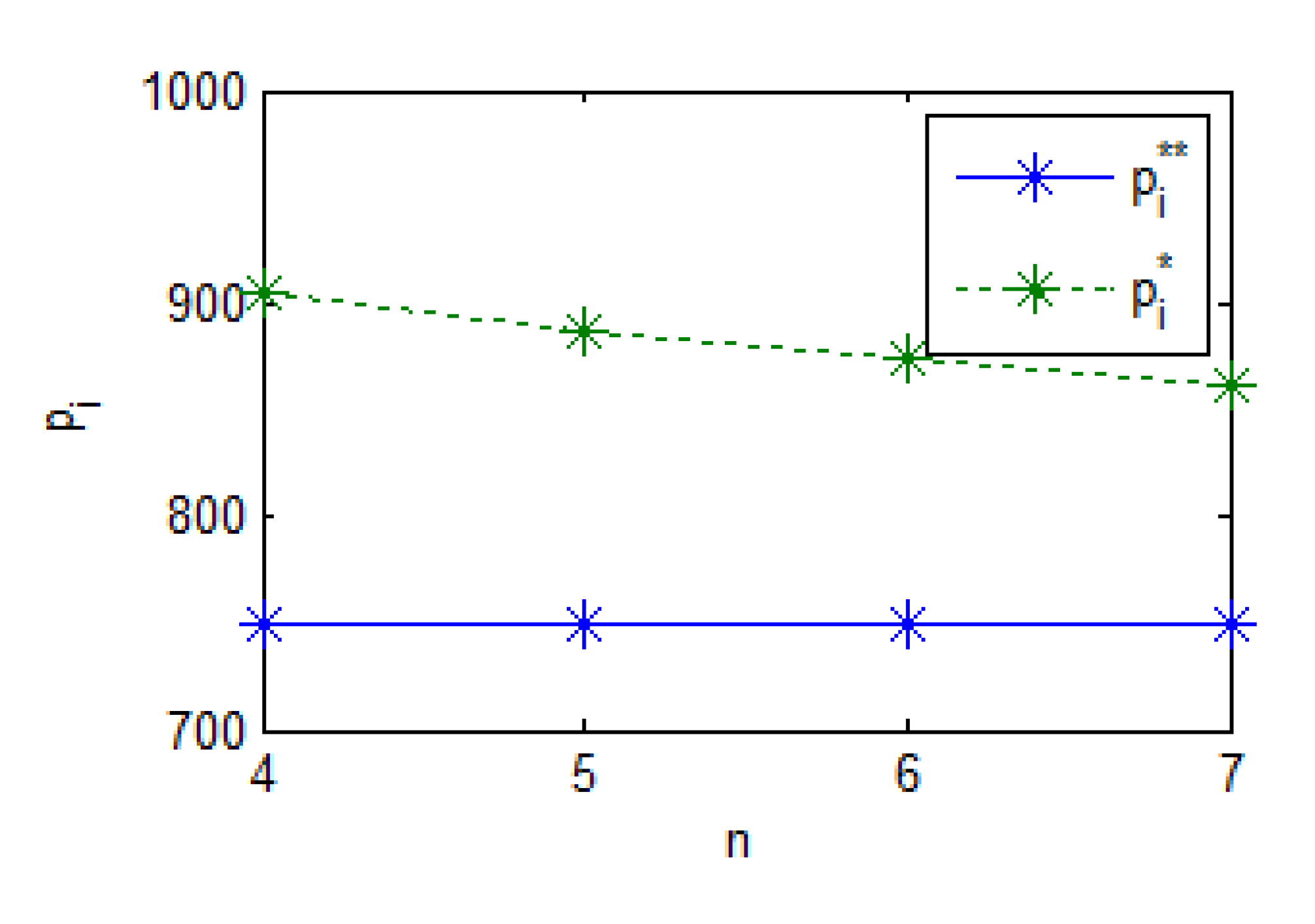

Figure 4 illustrates the variation in retail price as

increases from 4 to 7. Under centralized decision-making, the optimal retail price remains constant regardless of the number of retailers. In contrast, under the decentralized scenario, the optimal retail price decreases with an increasing number of retailers. As

increases, the discrepancy between

and

gradually decreases.

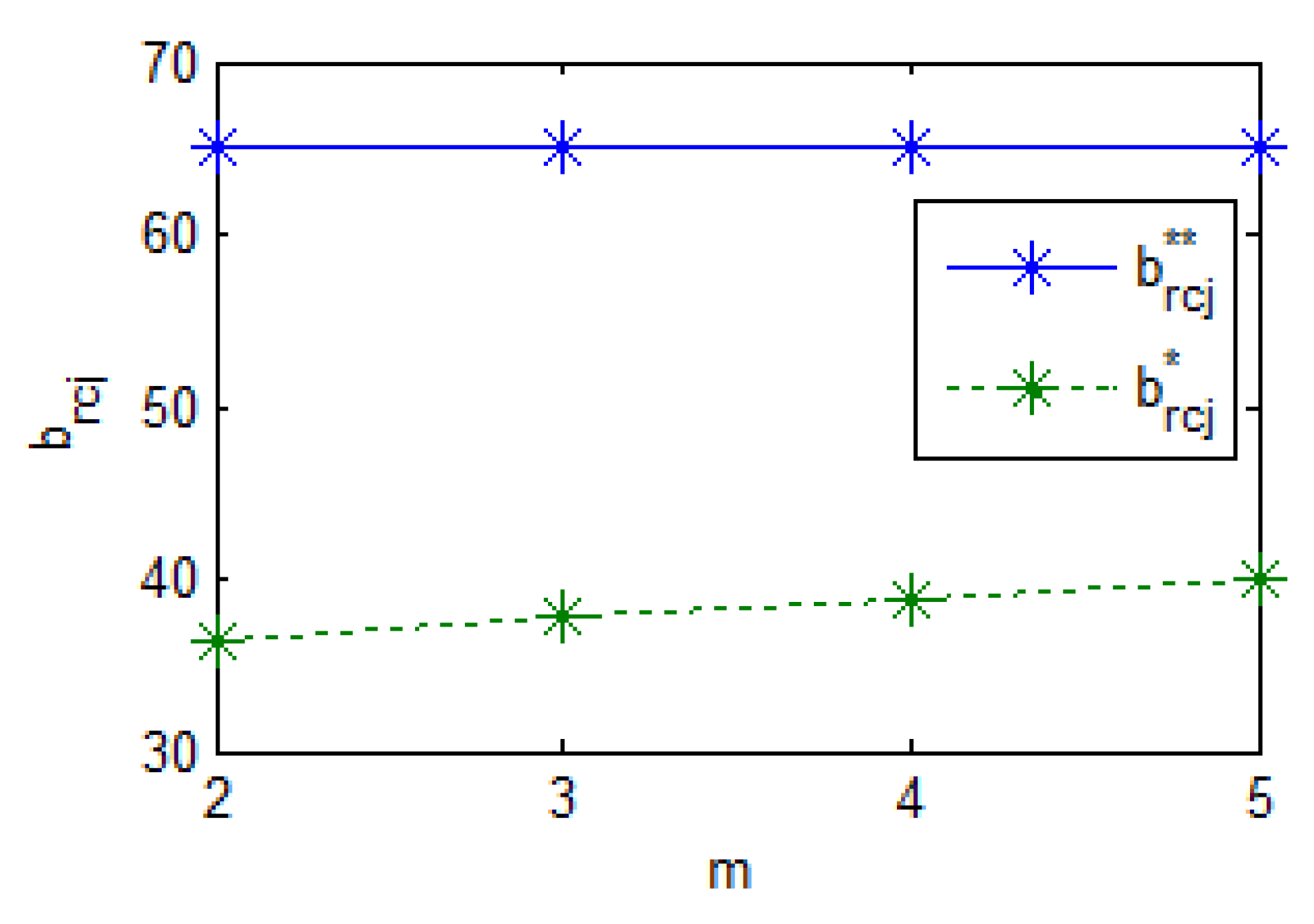

Figure 5 shows how the recycling price changes as

increases from 2 to 5. Under centralized decision-making, the optimal recycling price remains constant regardless of the number of recyclers. However, under decentralized decision-making, the optimal recycling price increases as the number of recyclers increases. As

increases, the difference between

and

gradually decreases.

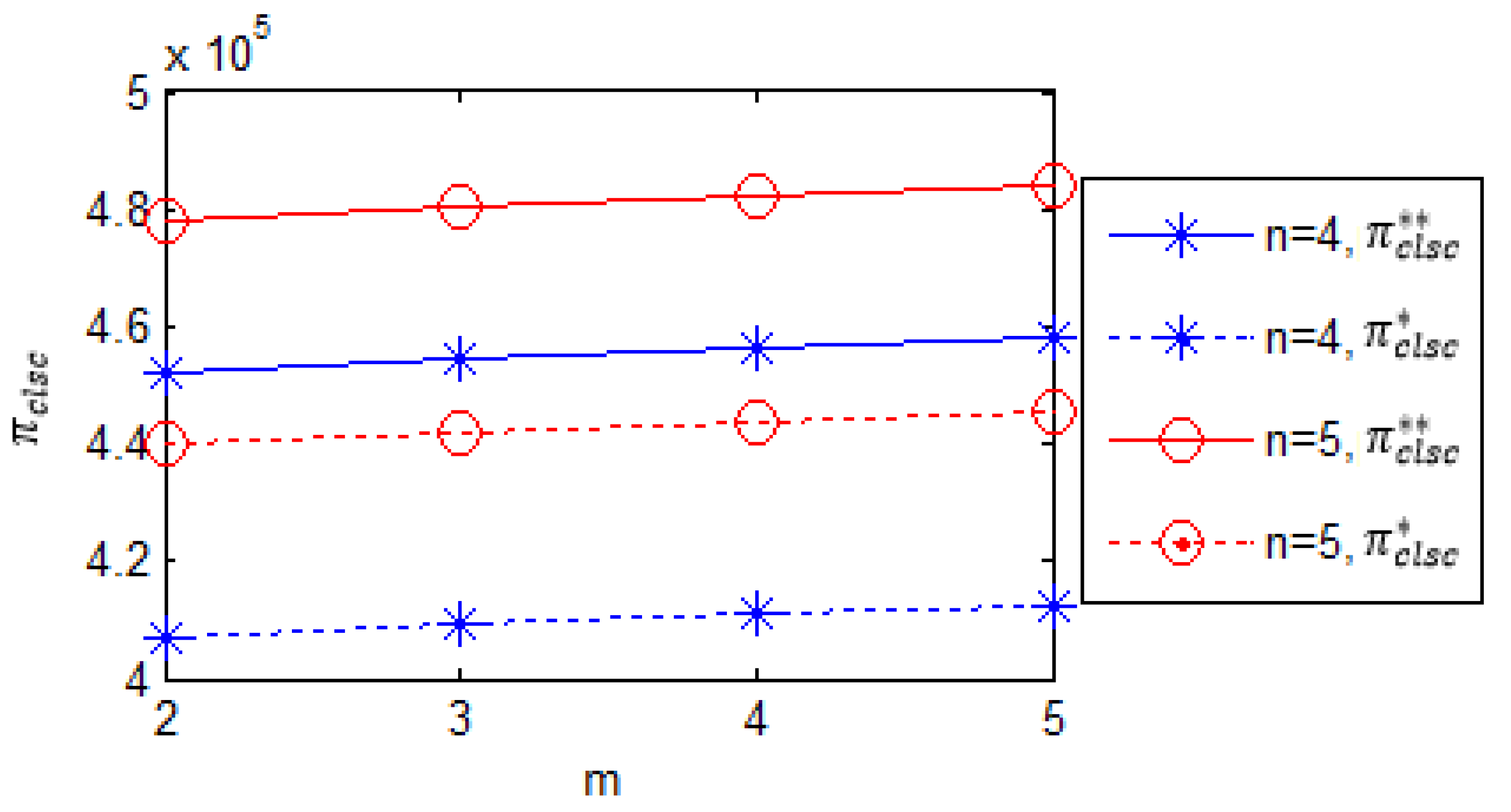

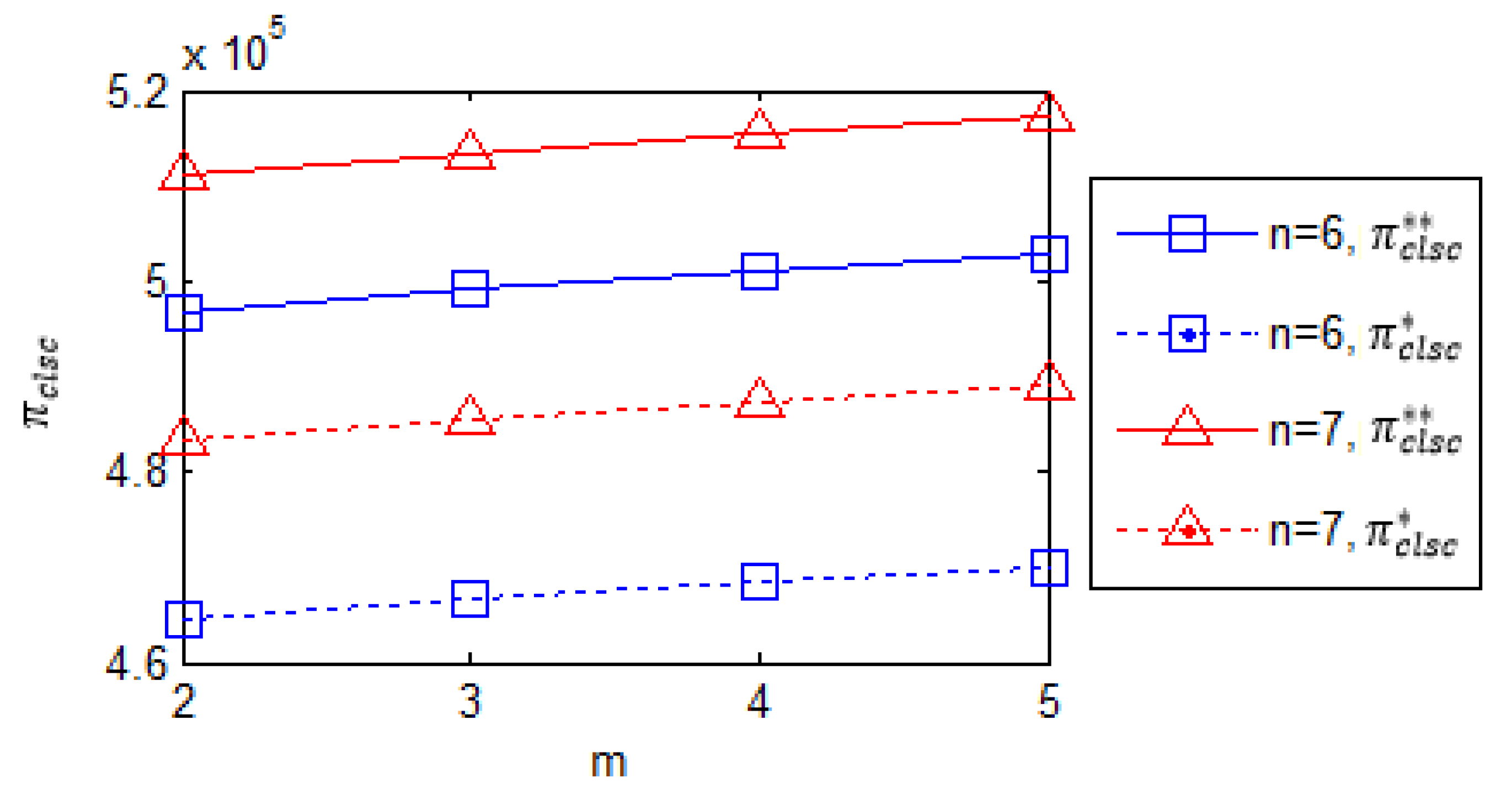

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show how the profits of the CLSC change as

varies from 4 to 7 and

from 2 to 5. From these figures, two conclusions are drawn:

(1) Under both decentralized and centralized decision-making, the optimal profits of the supply chain increase with the number of retailers or recyclers.

(2) The optimal profits of the supply chain under decentralized decision-making are always lower than those under centralized scenario. These lower profits indicate that the supply chains are in a state of discoordination.

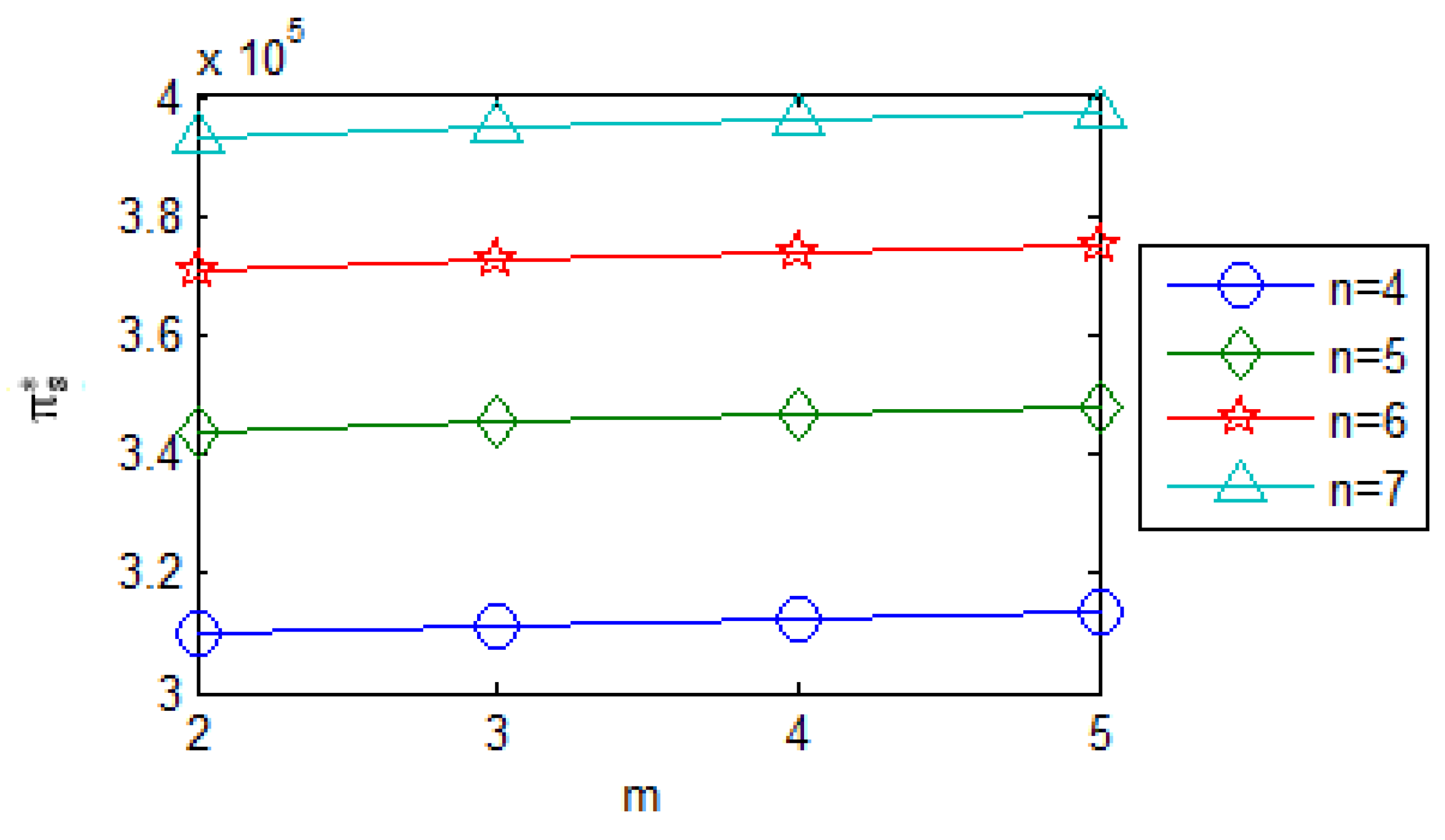

Figure 8 shows the variation in the manufacturer’s optimal profits as

ranges from 4 to 7 and

ranges from 2 to 5. Profits exhibit a positive correlation with retailer count and recycler count.

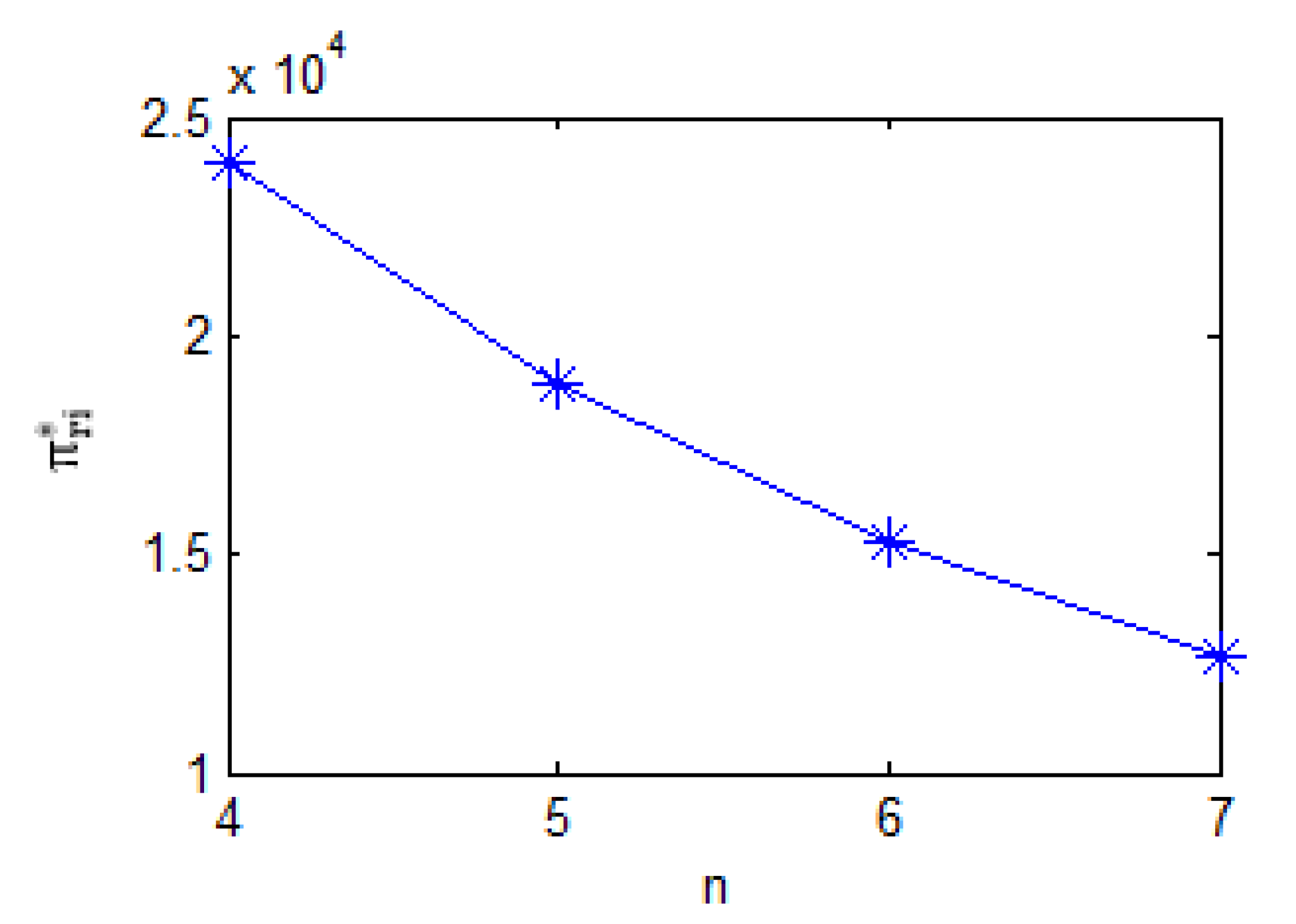

Figure 9 demonstrates a negative correlation between the number of retailers and their optimal profits, while

Figure 10 illustrates a similar inverse relationship between the number of recyclers and their optimal profits.

The minimum order quantity and recycling quantity required by the manufacturer within a linear transfer-payment contract are set as:

and

. Based on the participation constraints of the node enterprises and the condition

, the reward-penalty factors of the contract must satisfy the following derived conditions for each pair

in

,

,

.

Using the above system of inequalities and related parameters, we can obtain the following:

where: .

From

Table 2, two key conclusions can be drawn: (1) Under the linear transfer-payment contract, the profits of all supply chain members consistently exceed those under the decentralized scenario. (2) The total profit under this contract matches the maximum profit achievable by an integrated supply chain. These results demonstrate that the linear transfer-payment contract can achieve perfect coordination of the CLSC.

6. Conclusions

This paper investigates various aspects of product sales and used product recycling management, focusing on the competition effect and contract design in the CLSC. The study examines a CLSC consisting of a manufacturer, retailers, and recyclers, highlighting the impact of retailers’ and recyclers’ competition on order quantities, recycling volumes, and profits. A linear transfer-payment contract model is developed to maximize the total profit of the CLSC based on the Cachon profit function. The numerical results validate the theoretical analysis.

The main results of this study are summarized as follows.

Under decentralized decision-making, an increase in the number of retailers reduces their optimal order quantities and retail prices. In contrast, under centralized decision-making, more retailers lower optimal order quantities but leave the optimal retail price unaffected. For recyclers, decentralized decision-making results in decreased recycling volumes yet higher optimal recycling prices as their numbers grow. Under centralized decision-making, however, more recyclers reduce recycling volumes, while the optimal recycling price remains stable.

Competition among retailers or recyclers enhances profits for the supply chain and the manufacturer, whereas retailer competition erodes retailers’ profits, and recycler competition similarly diminishes recyclers’ profits.

When the order quantity reward-penalty factor and the recycling volume reward-penalty factor fall within specified ranges, the linear transfer-payment contract achieves coordination in a competitive CLSC comprising one manufacturer, retailers, and recyclers.

The following management insights can be drawn:

(1) The dominant manufacturer should collaborate with as many retailers and recyclers as possible, provided they are willing, as this benefits the manufacturer, the supply chain, and consumers.

(2) The manufacturer should coordinate the CLSC by establishing a linear transfer-payment contract with a larger pool of reliable retailers and recyclers, and setting the reward-penalty factors according to their participation constraints.

Further research should address the limitations of this study. First, this study assumes that new and remanufactured products are priced equally. Exploring scenarios where remanufactured products are sold at a discount relative to new ones could be a valuable extension. Second, the model in this paper does not account for the non-remanufacturing rate of used products. Future work could integrate the fuzzy set theory to quantify the non-remanufacturing rate. Third, manufacturer competition is excluded from the current framework. Given that product homogeneity intensifies market competition, extending the model to include multiple manufacturers would better reflect the real world dynamics.

References

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Mi, Y. Third-party remanufacturing mode selection for competitive closed-loop supply chain based on evolutionary game theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, Y.; Sahebi, H.; Ashayeri, J.; Teymouri, A. A competitive dual recycling channel in a three-level closed loop supply chain under different power structures: Pricing and collecting decisions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrjerdi, Y. Z.; Shafiee, M. A resilient and sustainable closed-loop supply chain using multiple sourcing and information sharing strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Z. Information sharing in a closed-loop supply chain with technology licensing. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 191, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, P.; Zhao, X.; Wang, M. The optimal combination between recycling channel and logistics service outsourcing in a closed-loop supply chain considering consumers’ environmental awareness. Sustainability-Basel. 2022, 14, 16385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, W.; Mishima, N. Optimal Decisions of Electric Vehicle Closed-Loop Supply Chain under Government Subsidy and Varied Consumers’ Green Awareness. Sustainability-Basel. 2023, 15, 11897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Sun, N. Government subsidies-based profits distribution pattern analysis in closed-loop supply chain using game theory. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 1715–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P; Xie, Z. Decision making and benefit analysis of closed-loop remanufacturing supply chain considering government subsidies. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e38487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Sun, S.; Gao, G.; Yang, R. Pricing and strategy selection in a closed-loop supply chain under demand and return rate uncertainty. 4or-Q. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 19, 501–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Peng, N. Manufacturer’s cooperation strategies of closed-loop supply chain considering recycling advertising. Rairo-Oper. Res. 2024, 58, 1555–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, D.; Younas, A.; Zhang, B. Coordination of closed-loop supply chain considering loss-aversion and remanufactured products quality control. Ann. Oper. Res. 2025, 349, 1225–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongen, I.; Ray, P.; Govindan, K. Creating a Sustainable Closed-Loop Supply Chain: An Incentive-Based Contract with Third-Party E-Waste Collector. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 462, 142351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Yang, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M. Dual-channel closed loop supply chains: forward channel competition, power structures and coordination. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 3510–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, B.; Sana, S. S. Game-theoretic analysis in an environment-friendly competitive closed-loop dual-channel supply chain with recycling. Oper. Manage. Res. 2022, 15, 627–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, W.; Liang, L.; Xia, Y.; Yin, J.; Yang, G. The revenue and cost sharing contract of pricing and servicing policies in a dual-channel closed-loop supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 191, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Chu, J.; Jin, L. Recycling channel selection and coordination in dual sales channel closed-loop supply chains. Appl. Math. Model. 2021, 95, 484–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhao, J. Pricing decisions with retail competition in a fuzzy closed-loop supply chain. Expert. Syst. App. 2011, 38, 11209–11216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, H.; Wu, Y.; Huang, H.; Chen, Z. Optimal pricing decisions for a closed-loop supply chain with retail competition under fuzziness. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2018, 69, 1468–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Dai, Y.; Ma, Z. Pricing decisions in closed-loop supply chains with competitive fairness-concerned collectors. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 4370697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvadarshini, P.; Biswas, I.; Srivastava, S. K. Impact of reverse channel competition, individual rationality, and information asymmetry on multi-channel closed-loop supply chain design. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 259, 108818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaula, A. K.; Jha, J. K. Pricing and quality improvement strategies in a closed-loop supply chain with dual collection channel. Int. J. Syst. Sci-Oper. 2023, 10, 2244416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Song, Y.; He, Q.; Jia, T. Competitive dual-collecting regarding consumer behavior and coordination in closed-loop supply chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 144, 106481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, N.; Jiang, B. Hybrid closed-loop supply chain with different collection competition in reverse channel. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2024, 276, 109371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, B. C.; Chakraborty, A.; Maiti, T. Pricing and return product collection decisions in a closed-loop supply chain with dual-channel in both forward and reverse logistics. J. Manuf. Syst. 2017, 42, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini-Motlagh, S. M.; Johari, M.; Ebrahimi, S.; Rogetzer, P. Competitive channels coordination in a closed-loop supply chain based on energy-saving effort and cost-tariff contract. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, L. Altruistic mode selection and coordination in a low-carbon closed-loop supply chain under the government’s compound subsidy: A differential game analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 366, 132863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).