1. Introduction

With growing awareness of environmental protection and sustainable development, an increasing number of enterprises are recycling end-of-use products and materials for remanufacturing, integrating these processes into closed-loop supply chains (CLSCs) alongside the traditional forward supply chain. For instance, Kodak has increased its remanufactured production by 51% from 2016 to 2022 in order to meet its sustainability goals [

1]. HP has also introduced a reuse and recycling program for unwanted equipment and printing consumables [

2]. Remanufacturing involves the specialized repair and restoration of used items such as automotive parts, engineering instruments, and machine tools [

3,

4]. The remanufactured products meet the same quality and performance standards as new ones while achieving significant energy, material, and cost savings. In addition, the process of recycling and remanufacturing used products benefits the environment by recycling waste and reducing carbon emissions. Remanufacturing can achieve near-zero solid waste generation and reduce air pollution emissions by over 80%, making it an effective approach to maximizing resource utilization and protecting the ecological environment [

5].

While in most industries the production process of remanufacturing can only be realized by manufacturers, the recycling process of remanufacturing can be also realized by retailers. Retailers have the natural advantage of being closer to consumers, who are increasingly interested in recycling used products [

6,

7,

8]. As remanufacturing technologies continue to mature, the value of used products has gradually increased, which has intensified recycling competition between manufacturers and retailers. The collection of used products by retailers introduces competition with manufacturers' collection efforts. However, manufacturers can also purchase recycled products from these retailers and recyclers, fostering a cooperative dynamic alongside the competition. For instance, Apple’s device exchange program operates through both online platforms and offline retail store channels [

9].

In a closed-loop supply chain, consumer purchasing behavior is influenced not only by the price and value of the product but also by the firm's advertising and marketing efforts. Through specific marketing tools, such as explanations of remanufacturing principles and processes on content platforms, consumers can develop greater confidence in the quality of remanufactured products [

10,

11]. In addition, advertising that promotes the environmental benefits of remanufactured products can resonate with consumers and increase their willingness to purchase [

12,

13,

14]. Such marketing efforts can be undertaken not only by manufacturers to promote their brand image and environmental values but also by retailers, who maintain closer connections with consumers [

15,

16]. Marketing often incurs certain costs, such as producing remanufactured content, purchasing traffic on web content platforms, and renting paid smart marketing software. For instance, to promote its "Move to Zero" initiative, Nike partnered with Ant Group to launch a green energy campaign. They introduced the "Nike Old Shoes New Life" mini-program on Alipay, enabling consumers to recycle their old shoes through the app. Participants earn corresponding Ant Forest green energy points, allowing them to unlock new green achievements and contribute to environmental sustainability [

17].

Cooperation among supply chain members plays a crucial role in building a sustainable supply chain. Empirical studies have shown that cooperation enhances supply chain performance by enabling the integration of internal and external resources, thereby promoting more sustainable development [

18]. In this article, we also explore the marketing cost-sharing contract between manufacturers and retailers.

The intricate interplay of competition and cooperation between manufacturers and retailers in a recycling-driven closed-loop supply chain inspires our investigation into determining the most appropriate marketing agents for such a system. Based on the above observations, in this paper we utilize the Stackelberg game model to construct a closed-loop supply chain model consisting of a manufacturer and a retailer. In the forward supply chain, the manufacturer sells goods to consumers through retailers; in the reverse supply chain, the manufacturer and retailers competitively recycle used products from consumers, and in addition, the manufacturer buys used products from retailers at a buyback prices. We discuss four scenarios of the model depending on the marketing agent: (1) no marketing effort (Model B), (2) a manufacturer exerting a marketing effort (Model M), (3) a retailer exerting a marketing effort (Model R), and (4) a centralized supply chain exerting a marketing effort (Model C). Based on this, we pose the following questions:

- (1)

When comparing the first three models, which is the preferred option for retailers, manufacturers, and the overall supply chain? How does the intensity of recycling competition influence their preferences?

- (2)

How do consumer surplus and environmental damage levels vary across different models?

- (3)

Can a marketing cost-sharing contract be implemented to optimize the profits for manufacturers, retailers, and the overall supply chain?

Our findings reveal that in the first three models, the manufacturer consistently prefers the retailer to undertake marketing efforts, regardless of the intensity of recall competition. However, when recycling competition is weak, the retailer prefers the manufacturer to handle marketing efforts, whereas under strong recycling competition, the retailer is willing to take on the marketing efforts himself. Consumer surplus is consistently highest when the retailer undertakes the marketing efforts. The environmental damage associated with different modes depends on the base demand. When the base demand is high, marketing effort by the retailer results in lower environmental damage. Conversely, when the base demand is low, marketing effort by the manufacturer leads to lower environmental damage. Additionally, we find that a marketing cost-sharing contract can always enhance the profitability of the entire supply chain. This cost-sharing arrangement can be naturally achieved when the manufacturer undertakes the marketing efforts.

The main innovations of this paper are as follows. When analyzing marketing behavior in a closed-loop supply chain, the competitiveness of recycling cannot be overlooked. This recycling competitiveness introduces a more complex competitive relationship between manufacturers and retailers. Previous studies on marketing in CLSCs have not addressed how this competitive recycling relationship influences marketing strategy choices. Conversely, our research examines how adopting promotional activities impacts recycling efforts in the reverse channel. Marketing behaviors in the forward channel not only help firms achieve greater market coverage but also generate increased revenue and demand, which subsequently influence recovery performance in the reverse channel. Similarly, recycling performance in the reverse channel can affect pricing and marketing decisions in the forward channel. Therefore, it is essential to study these two types of firm behaviors within an integrated closed-loop supply chain framework.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature.

Section 3 presents the model and hypotheses.

Section 4 provides the optimal solutions of the model.

Section 5 analyzes the results.

Section 6 discusses strategy selection and cost-sharing contracts through a numerical example. Finally,

Section 7 summarizes our findings and outlines future research directions. All proofs are provided in

Appendix A.

2. Literature Review

In this section, we review the relevant literature across three main areas: (1) recycling channel management in CLSCs, (2) channel competition in CLSCs and (3) marketing effort in CLSCs.

2.1. Recycling Channel Management in CLSCs

Recycling channel management in CLSCs is a crucial research direction in these studies. As a pioneering work, Savaskan et al. [

19] examined the selection of appropriate entities for recycling used products within a closed-loop supply chain. They analyzed three scenarios: (1) manufacturers managing recycling directly, (2) retailers handling recycling, and (3) outsourcing recycling to third-party entities. Their findings highlighted that retailers, being closer to consumers, are better suited to act as recyclers of used products. Similarly, several other literatures have explored the issue of optimal subjects for recycling activities under different conditions. Alegoz et al. [

20] used a two-stage model to depict CLSC, incorporating firms' discount factors and environmental sensitivities, and outlined conditions for manufacturers to outsource recycling to third parties. Zheng et al. [

21] analyzed the optimal recycling channel choice in a dual-channel structure comprising a direct sales channel and a traditional retail channel, finding that both the manufacturer and the retailer prefer to handle recycling independently. Giri et al. [

22] developed a model incorporating a dual forward channel and dual recycling channel structure, comprising a traditional retail platform and an e-platform. The model is used to derive optimal pricing and recycling decisions under varying power structures. Atasu et al. [

23] analyzed the influence of the collection cost structure on the optimal selection of the recycling channel. The authors noted that the manufacturer’s optimal choice of reverse channel is influenced by how the collection cost impacts the retailer’s sales and quantity decisions. Chuang et al. [

24] explored the optimal recycling channel selection for manufacturers operating with short product life cycles and volatile demand. Cheng and Wang [

25] investigated the optimal recycling channel selection in a closed-loop supply chain under conditions where consumers are uncertain about the quality of remanufactured products. Our paper examines the management of two competing recycling channels, considering both recycling inputs and returns within each channel.

2.2. Channel Competition in CLSCs

In this subsection, we review articles from the literature that address channel competition in closed-loop supply chains, focusing on two aspects: competition in forward supply chains and competition in recycling channels within reverse supply chains.

The following literature addresses the issue of channel competition in forward supply chains [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Zheng et al. [

26] They examined the impact of forward supply channel competition and power structures on a two-channel closed-loop supply chain. Their findings revealed that, under positive channel competition, each supply chain member shows a preference for assuming a leadership role. Jalapathy and Unnissa [

27] analyzed product pricing in the context of competition between new and remanufactured products. Qiang [

28] examined the optimal product quality and quantity in the context of market share competition among remanufacturers in a two-phase CLSC. Additionally, their analysis addresses the impact of remanufactured product design and consumer perception of remanufactured products on profits and market share. Zhang and Ren [

29] constructed a closed-loop supply chain consisting of remanufacturers, original manufacturers, and third-party collection platforms in which they accounted for demand competition. Hosseini et al. [

30] analyzed the competition between two dealers for used product services and examined the incentives provided to suppliers under such competitive conditions.

The following literature focuses on recycling competition within the reverse channel [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Huang et al. [

31] examined a closed-loop supply chain comprising manufacturers, retailers, and third-party collection platforms, where retailers and third-party platforms compete for the recycling of used products. They compared the performance of supply chains under competitive recycling with those using a single-channel recycling approach and found that dual-channel recycling outperformed under specific parameters. He et al. [

32] compared the recycling efficiency of decentralized recovery models involving retailers and manufacturers with that of centralized models and proposed two coordination mechanisms to improve the performance of decentralized recovery models. Wang et al. [

33] investigated whether manufacturers should establish a fully integrated closed-loop supply chain or outsource recycling activities to retailers in a competitive recycling market. Zhou et al. [

34] analyzed the equilibrium outcomes of recycling channels under the leadership of electric vehicle manufacturers and electric vehicle recyclers, taking into account the competition between automotive recyclers and third-party recyclers. Feng et al. [

35] examined the comparison between decentralized and centralized models in closed-loop supply chains, considering recycling competition and differences in recycling quality. Zhang et al. [

36] found that enterprises in the supply chain will opt for a competitive recycling model only when the intensity of competition exceeds a specific threshold. He et al. [

37] examined the optimal collection strategies under monopoly, duopoly, and mixed competition, considering customer sensitivity to the convenience of returning discarded products. Competition for recycled products is prevalent in practice. For example, common recycling channels for Apple products often include third-party platforms, offline stores, and official websites. To better align with real-world scenarios, our literature considers the competition between manufacturers and retailers in the recycling process.

2.3. Marketing Effort in CLSCs

Consumer behavior is also particularly important for the management of closed supply chains. Effective marketing efforts involve promoting the processes and principles behind remanufactured products to reassure consumers about their quality. Additionally, raising awareness of the environmental benefits of remanufactured products can boost consumer preference and increase their willingness to purchase. The impact of marketing activities has also been extensively examined in the closed-loop supply chain research literature [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

Taleizadeh et al. [

38] compared the marketing efforts of different supply chain agents in a closed supply chain, consisting of a manufacturer's direct sales channel and a traditional retail channel, but did not address the channel competition involved. Hong and Guo [

39] compared three different contracts between manufacturers and retailers in a closed-loop supply chain with social responsibility considerations, including pure price contracts, green marketing cost-sharing contracts, and two-part tariff contracts. Li et al. [

40] examined the case of retailer cost-sharing for the manufacturer’s greening inputs in a closed supply chain, where the retailer handles marketing efforts and the manufacturer focuses on product greening. They compared this with the scenario where the manufacturer shares the marketing costs with the retailer. Gao et al. [

41] analyzed optimal decisions for pricing, recycling effort, and marketing effort under three power structures in a closed-loop supply chain. These structures include manufacturer-dominated, retailer-dominated, and vertical Nash. Hu et al. [

42] compared different sales effort models under the influence of network externalities, including no marketing effort, retailers making marketing efforts, and manufacturers making marketing efforts. They accounted for network externalities in the forward channel but did not address competition in the recycling channel. Ma et al. [

43] analyzed the optimal recycling and marketing efforts under four reverse channel structures where retailers are responsible for marketing efforts considering fairness concerns.

However, the aforementioned articles that address marketing in closed-loop supply chain overlook competition in the recycling process. This paper aims to explore how competition in the recycling channel influences the choice of the optimal marketing strategy.

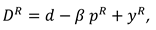

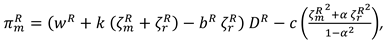

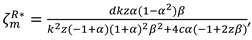

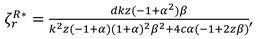

3. Problem Description

We consider a CLSC including a manufacture and a retailer. The manufacture produces a product with virgin materials and used materials which can be collected by himself and purchased from the retailer at a buyback price

. We define

as the cost saving per unit achieved by recycling used materials. The retailer purchases the product at a wholesale price

and sells it to consumers at a price

. The model’s notations are presented in

Table 1.

In the recycling market, the manufacturer and retailer compete to collect the used partial materials of the used products from consumers. A parameter

is used to illustrate the competition intensity between them. Consistent with Huang et al. [

30] and Hong et al. [

38], we assume the members’ recycling investments have a symmetric influence on each other as follows

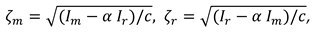

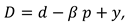

where

, and the

is the recycling cost parameter, which is assumed sufficiently large. Then the investment cost can be presented as,

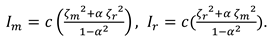

Fallowing Taleizadeh et al. [

38], the market demand can be increased by exerting the marketing effort with a level

, and the incurred cost is

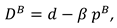

where

is the marketing cost coefficient. Hence, the demand can be expressed as

where

pertains to the market base and

is the price-demand coefficient. The other assumptions for this paper are listed as follows.

- (1)

We assume the product produced by the virgin and recycling materials have the same utility to consumers and all products are sold at the same price. In many industries, the technology of remanufacturing is relative mature, and the remanufactured products usually have the exact same appearance and function as the origin products. For example, Kodak sells new and remanufactured products at the same price and consumers cannot tell the difference.

- (2)

The unit producing cost is assumed to 0 [

42].

- (3)

We assume

and

to ensure that recycling competition is sufficiently strong; otherwise, recycling volumes could surpass new product production, which would be factually inaccurate [

38,

40].

- (4)

We assume

to ensure that the cost of the promotion is high enough to ensure the existence of an optimal marketing intensity solution [

38].

4. Model Formulation and Solution

We aim to examine the impact of marketing effort of different supply chain members on CLSCs considering recycling competition. Hence, four models are detailed as follow. The first model is our base model, in which we study the performance of supply chains without marketing efforts. In the second and third models, we examined separately the situation when the manufacturer exerts a marketing effort and the when the retailer exerts a marketing effort. In the fourth model, to compare the performance of centralized and decentralized supply chains, we study the centralized supply chain case with marketing effort.

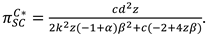

4.1. Model B (Without Marketing Efforts)

In this model, neither the manufacturer nor the retailer exerts marketing effort in the CLSC systems. The decision sequence can be described as follows. First, the manufacturer determines the recycling efforts

, the buyback price

and the wholesale price

. Then the retailer sets the recycling efforts

the product price

. And the demand function is

now, the profit functions of the manufacture and the retailer can be expressed as

With the aforementioned expression, we have Proposition 1.

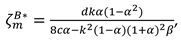

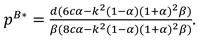

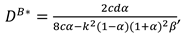

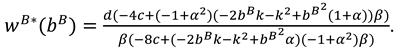

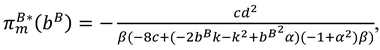

Proposition 1. In Model B, the optimal decisions of the manufacturer and retailer are

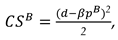

In this model, With the optimal decisions in Proposition 1, the optimal demand and the profits of the manufacturer, the retailer and total supply chain can be derived as

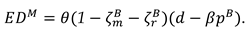

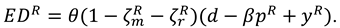

The consumer surplus and environment damage are

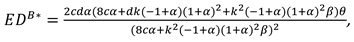

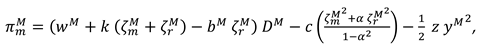

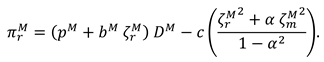

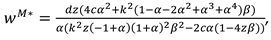

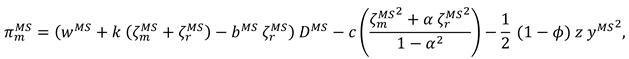

4.2. Model M (Manufacture Invests in Marketing Efforts)

In this model, the manufacturer exerts marketing effort in the CLSC systems. The decision sequence can be described as follows. First, the manufacturer determines the recycling efforts

, the buyback price

, the wholesale price

and the marketing effort intensity

. Then the retailer set the recycling efforts

the product price

. And the demand function is

now, the profit functions of the manufacture and the retailer can be expressed as

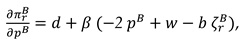

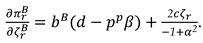

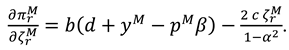

With the aforementioned expression, we have Proposition 2.

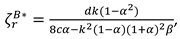

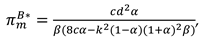

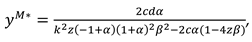

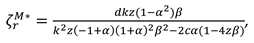

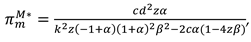

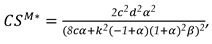

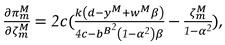

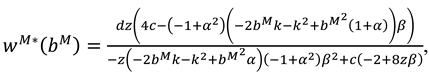

Proposition 2. In Model M, the optimal decisions of the manufacturer and retailer are

In this model, With the optimal decisions in Proposition 2, the optimal demand and the profits of the manufacturer, the retailer and total supply chain can be derived as

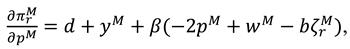

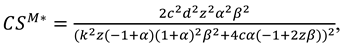

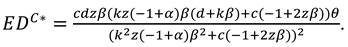

The consumer surplus and environment damage are

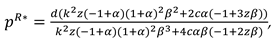

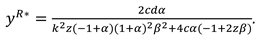

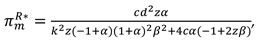

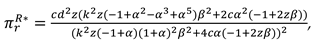

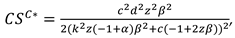

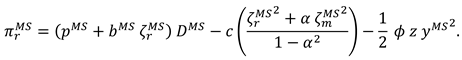

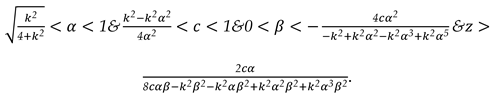

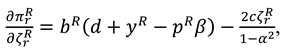

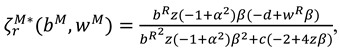

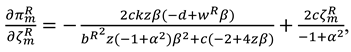

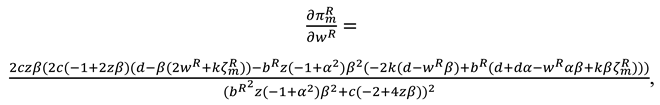

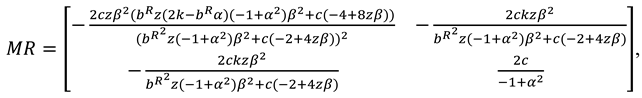

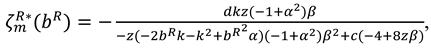

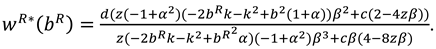

4.3. Model R (Retailer Invests in Marketing Efforts)

In this model, retailer exerts marketing effort in the CLSC systems. The decision sequence can be described as follows. First, the manufacturer determines the recycling efforts

, the buyback price

and the wholesale price

. Then the retailer set the recycling efforts

, the product price

, and the marketing effort intensity

. And the demand function is

now, the profit functions of the manufacture and the retailer can be expressed as

With the above expression, we have Proposition 3.

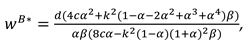

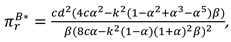

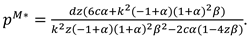

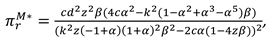

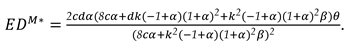

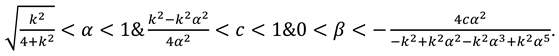

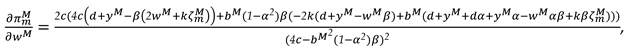

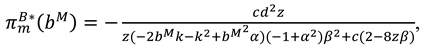

Proposition 3. In Model R, the optimal decisions of the manufacturer and retailer are

In this model, With the optimal decisions in Proposition 3, the optimal demand and the profits of the manufacturer, the retailer and total supply chain can be derived as

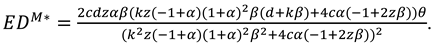

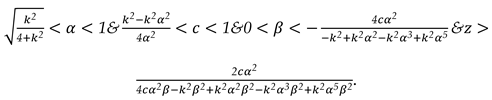

The consumer surplus and environment damage are

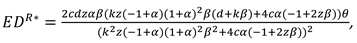

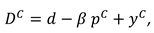

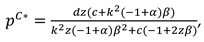

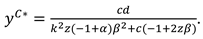

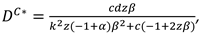

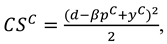

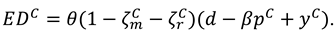

4.4. Model C (Centralized Supply Chain exerts Marketing Effort)

In this section, we integrate the manufacturer and the retailer into a single decision-making entity who determine the recycling effort in the two channels

and

, the product price

and marketing effort level

. And the demand function is

now, the profit functions of the centralized supply chain can be expressed as

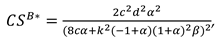

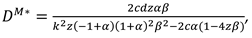

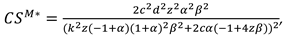

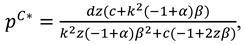

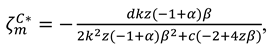

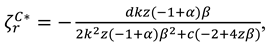

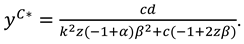

Proposition 4. In Model C, the optimal decisions of the centralized supply chain are

In this model, With the optimal decisions in Proposition 4, the optimal demand and the profit of the centralized supply chain can be derived as

The consumer surplus and environment damage are

5. Discussion

In this section, we compare the equilibrium results for the different models in the section 4 and analyze the effect of key parameters.

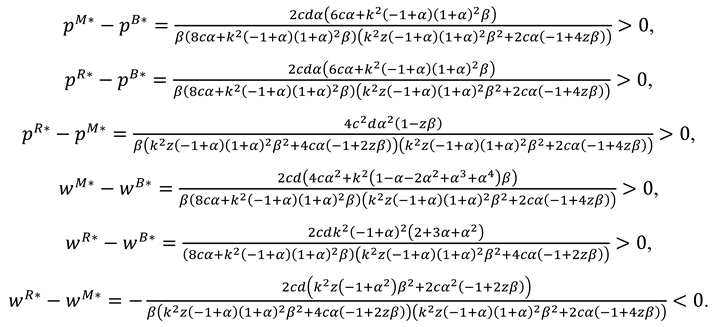

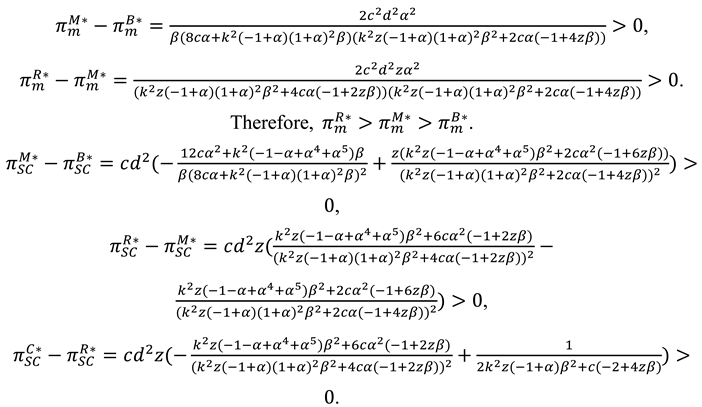

Corollary 1.

The optimal wholesale price, sales price in different model are as follows:

, .

Corollary 1 demonstrates that, (1) The sales price is highest in the centralized supply chain model, whereas it is lowest in the benchmark model without marketing efforts. This suggests that, regardless of which supply chain member undertakes the marketing effort, the associated costs are ultimately passed on to the consumer through higher product prices. (2) Compared to the model where the manufacturer undertakes marketing efforts, the model with retailer-led marketing results in a lower wholesale price but a higher sales price. When the manufacturer undertakes marketing, to cover marketing expenses and enhance its own profitability, the manufacturer raises the wholesale price, which in turn incentivizes the retailer to set lower selling prices to achieve significant increases in demand. In contrast, when the retailer handles marketing efforts, it directly targets consumers to boost sales and profitability. Retailers, being closer to the end consumer, can better tailor marketing strategies to consumer preferences. To support this, manufacturers are incentivized to keep the wholesale price lower to encourage the retailer’s promotional activities. The retailer, in turn, raises the sales price to recover marketing costs and maximize its margins.

Corollary 2.

The optimal buyback price of the recycling materials and optimal recycling efforts of manufacture and retailer are as follows: , , .

Corollary 2 states that (1) the selection of the supply chain member responsible for implementing recycling efforts does not influence the optimal price of recycled materials. (2) compared to the scenario where no marketing effort are undertaken, both manufacturer’s and retailer’s recycling efforts increase when marketing efforts are implemented. Marketing increases profitability by raising product sales, providing firms with more resources to invest in recycling efforts. Both the manufacturer and retailer see the value of recycling as a way to reduce raw material costs and improve their long-term competitiveness. (3) Supply chain members that implement marketing efforts also tend to enhance their recycling efforts, indicating a positive correlation between marketing initiatives and environmental responsibility.

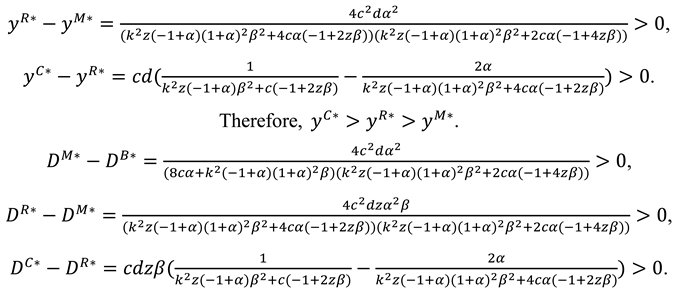

Corollary 3.

The optimal marking effort level and demand in different models are as follows:, .

Corollary 3 demonstrates that: (1) demand consistently increases with the adoption of marketing efforts, with the highest marketing intensity observed in a centralized supply chain, resulting in the highest demand. (2) The marketing investment is greater when retailers undertake marketing efforts compared to manufacturers. Consequently, market demand is also higher when retailers engage in promotions than when manufacturers do. This is because retailers are the final touchpoint in the supply chain, making them more invested in the success of marketing initiatives that directly impact consumer purchasing decisions.

Corollary 4.

The optimal profits of manufacturer and the entire supply chain in different models are as follows:, .

Corollary 4 demonstrates that (1) both the manufacturer’s and the retailer’s marketing efforts lead to increased profits for the manufacturer compared to a scenario with no marketing efforts. However, the manufacturer prefers the retailer to undertake the marketing effort rather than handling it himself. (2) Profit for the entire supply chain is highest under a centralized structure, driven by higher price and greater marketing intensity enabled by centralized decision-making. Among the remaining three models, when the retailer conducts marketing effort, the benefits of marketing are more directly aligned with their interests due to their closer connection to consumers, resulting in higher marketing intensity and, consequently, elevated prices. The retailer's preference for marketing models will be demonstrated through a numerical example in the next section.

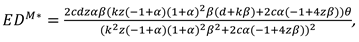

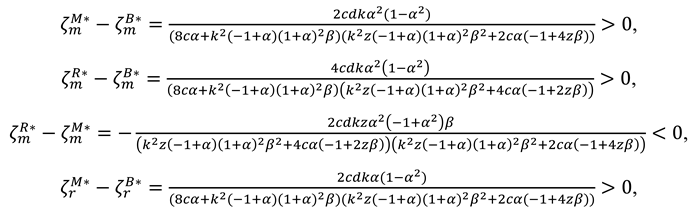

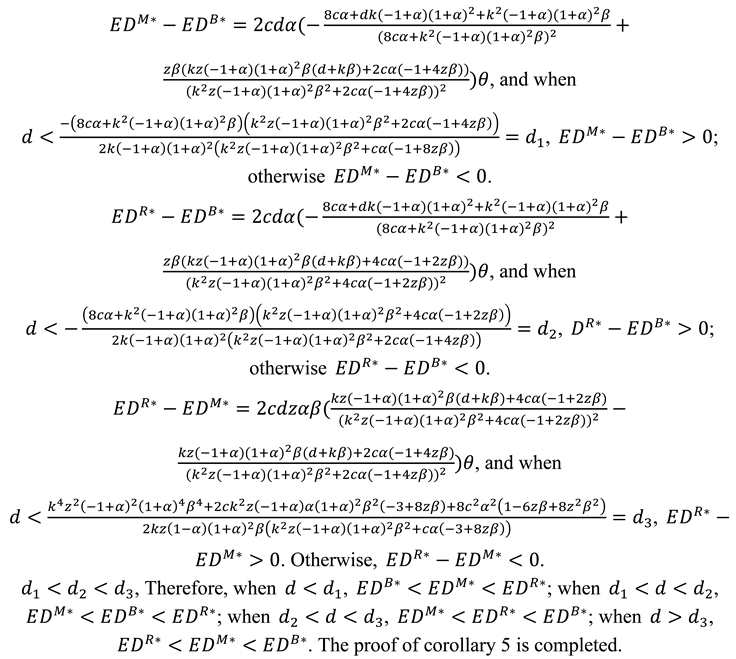

Corollary 5. The optimal consumer surplus and environment damage in the first three models are:

- (1)

;

- (2)

When then; when then; when , then ; when , then .

Corollary 5 indicates that (1) when the retailer undertakes marketing efforts, the consumer surplus is the highest among the three models. This outcome occurs because stronger advertising efforts attract more consumers, despite the higher product pricing. The manufacturer achieves the next highest consumer surplus when it undertakes advertising and marketing, with the lowest consumer surplus observed in the absence of any promotional efforts. (2) Model B has the least environmental impact when the market base is small, whereas Model M is the most environmentally friendly for a medium-sized market base, and Model R minimizes environmental harm when the market base is large. The reason are as bellows. Note that Corollary 3 reveals that marketing efforts by firms consistently lead to an increase in quantity demanded and production compared to scenarios without marketing, thereby exerting a negative impact on the environment. However, Corollary 2 indicates that recycling efforts in both recycling channels consistently increase when firms engage in marketing activities, which positively impacts the environment. Therefore, when the market base is small, the limited size of the market results in insufficient recycling efforts, allowing the negative environmental impact of marketing adoption to dominate. In contrast, when the market base is larger, firms undertake greater recycling efforts, allowing the positive environmental impacts of recycling to dominate.

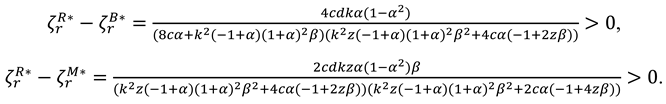

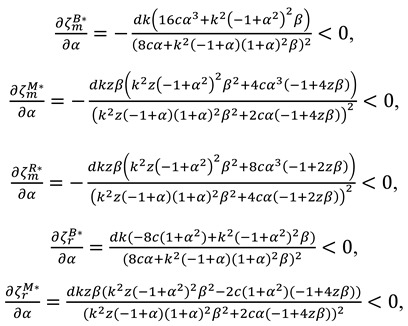

Corollary 6 Impact of the increased recycling intensity on the optimal decisions under Model B, Model M and Model R.

- (1)

.

- (2)

.

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

.

- (6)

.

- (7)

When , then , when , ; when , then and , when , then and .

Corollary 6 demonstrates that as recycling competition intensity increases: (1) the cost of collecting recycled materials rises, resulting in a decline in recycling efforts by both manufacturers and retailers. Manufacturers further reduce retailers' incentives to recycle by lowering buyback prices ; (2) the wholesale price decreases across all three models; and (3) in Model B, the market price increases, whereas in Models M and R, the market price decreases. This is because in Model B, the absence of marketing efforts means that prices are primarily driven by cost factors, and as recycling competition intensity () increases, the heightened pressure to secure recycled materials raises their costs, which firms pass on to consumers through higher product prices. In both Model M and Model R, as marketing efforts in both models strategically counteract the cost pressures of recycling competition. By leveraging marketing to boost demand and maintain competitiveness, firms in both models lower prices in response to increased recycling competition, resulting in a negative relationship between sales price and . (3) Advertising intensity declines in both Model M and Model R. This suggests that intensifying recycling competition in the reverse channel will not only reduce the supply chain's enthusiasm for recycling but also weaken their motivation for marketing in the forward channel. (4) Greater competitive intensity in recycling mitigates environmental damage when the market base is relatively small, as the benefits of reduced product production and emissions—driven by decreased demand under higher competitive intensity—take precedence. When the market base is relatively large, the negative environmental impacts of reduced recycling efforts are outweighed by the adverse effects of heightened recycling competition intensity, potentially resulting in greater environmental damage.

6. Numerical Analysis

In this section, we use a numerical example to analyze the results of the four models. We use the following parameters and they satisfy all the assumptions we propose in section 3. In addition, as our variable of analysis, and to satisfy the condition we assume that .

6.1. Profits of Supply Chain and Environment Damage

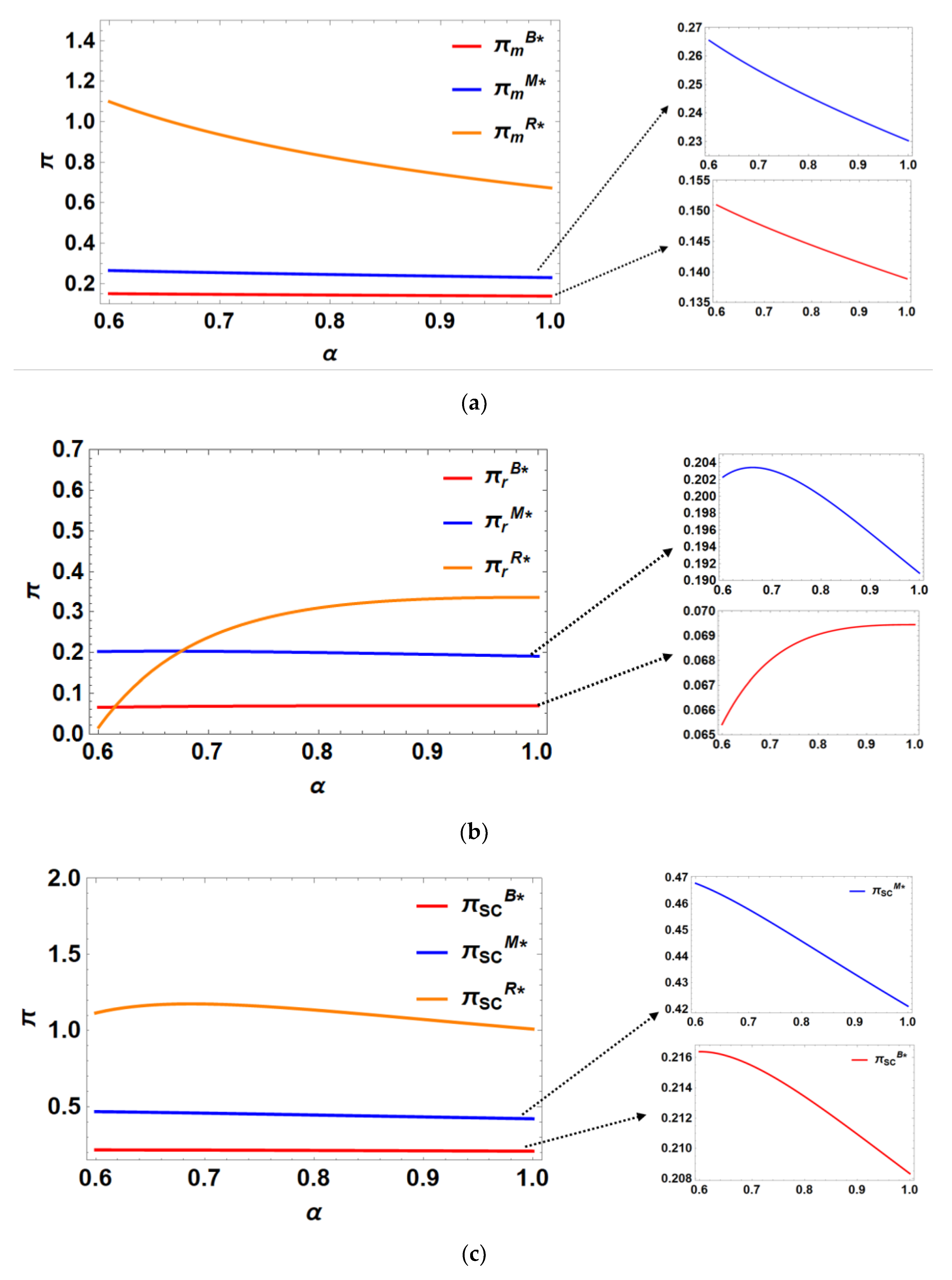

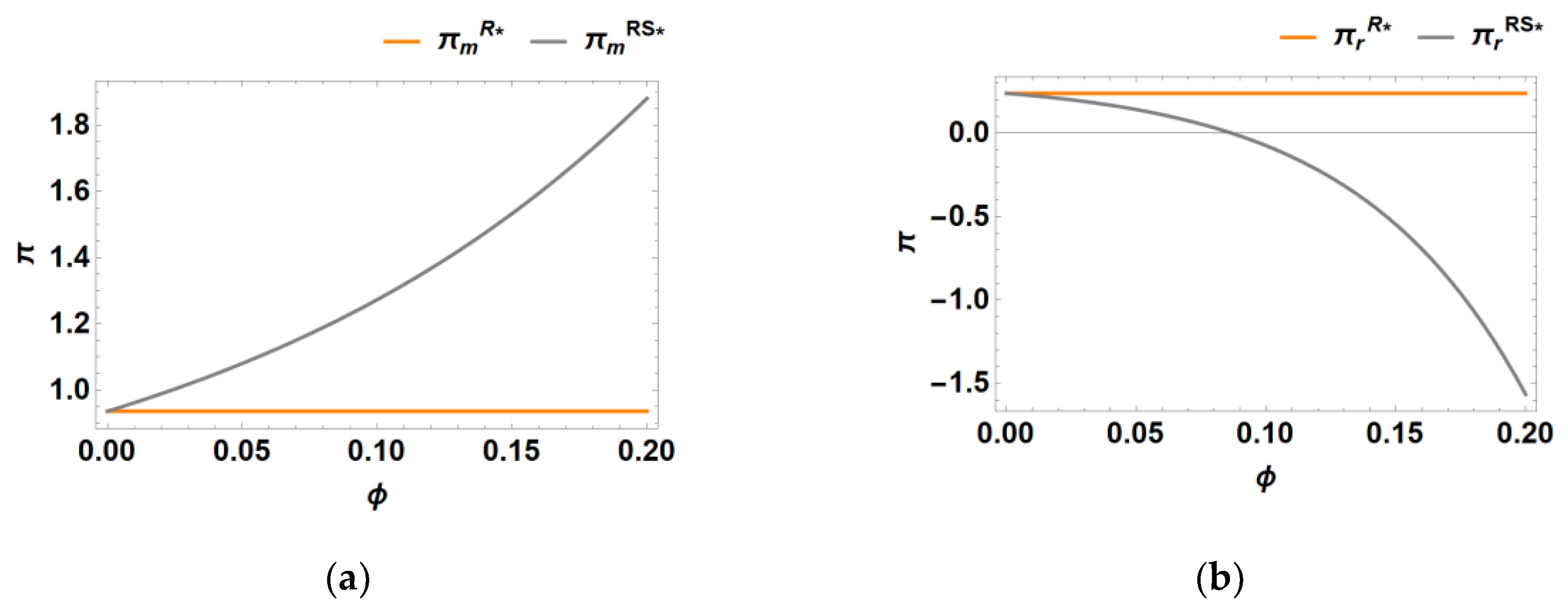

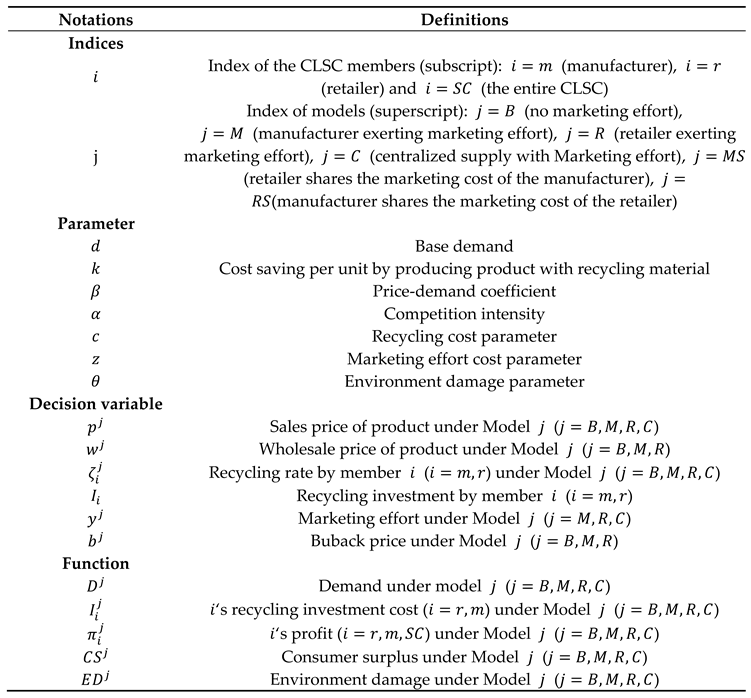

As shown in

Figure 1 (a), the manufacturer’s profit consistently decreases with increasing competitive intensity in recycling. This heightened competition raises recycling costs, making it more challenging for the manufacturer to achieve cost savings in remanufacturing. However,

Figure 1 (b) indicates that in both Model B and Model R, the retailer's optimal profit tends to increase as the competitive intensity of recycling rises. This increase in profit can be attributed to two factors: a decrease in wholesale prices driven by higher competition intensity, and a reduction in recycling costs resulting from lower recycling intensity. In Model M, however, as the manufacturer gains greater direct control over the market through advertising efforts, an increase in recycling competition intensity causes the retailer's profit to first rise and then fall.

From

Figure 1(c), it is evident that when retailers engage in marketing, the profit of the entire supply chain initially increases but then decreases as the intensity of recycling competition grows. As the intensity of recycling competition increases, it reduces the incentive for supply chain members to engage in recycling, thereby diminishing production cost savings on one hand. On the other hand, increased competition intensity reduces the retailer's incentive to recycle and their willingness to wholesale. Thus, the supplier is motivated to lower the wholesale price to encourage the retailer's wholesaling. This, in turn, mitigates the double marginalization effect and enhances the profitability of the entire supply chain. The interaction of these two forces reveals that as the intensity of competition increases, the profitability of the entire supply chain initially rises and then falls. Therefore, when the competition intensity is moderate, the effect of mitigating the double marginalization effect outweighs the negative impact of reduced recycling incentives.

Additionally, by comparing the three curves in

Figure 1(a), we can observe that the manufacturer always prefers the retailer, who is closer to the market and has pricing power, to undertake advertising efforts. In contrast, a comparison of the three curves in

Figure 1(b) reveals that when recycling competition intensity is low, the retailer prefers the manufacturer to carry out advertising efforts. However, when competition intensity is high, the retailer prefers to conduct market promotions themselves. This suggests that under high recycling competition intensity, the strategic preferences of the manufacturer and retailer can align.

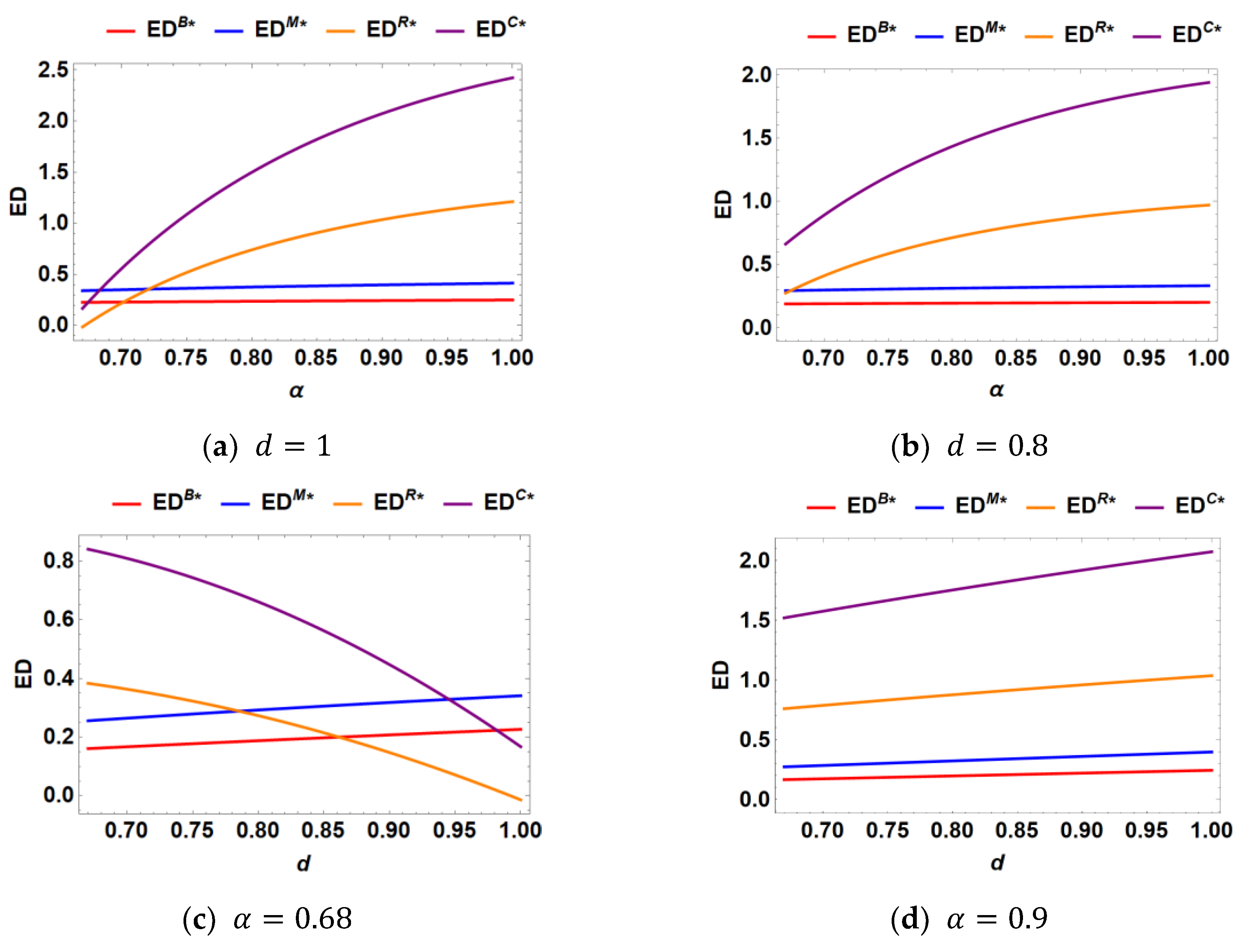

The variation of environmental damage with the intensity of recycling competition under the four models is illustrated in

Figure 2(a) and 2(b). Firstly, it can be seen from the figure that the sensitivity of environmental damage with the change of recycling competition intensity is the strongest in the case of centralized supply chain (Model C), followed by the case of retailer marketing (Model R), and the sensitivity is weaker in the case of Models B and M. The environmental damage is also greater with the increase of recycling competition intensity in the centralized supply chain (Model C). Moreover, as the intensity of recycling competition increases, the harm to the environment is greater. When the intensity of competition for recycling is low, the recycling effort under Model R and Model C is high, and firms adopt large quantities of recycled materials, so the environmental hazard is low. However, when the intensity of competition increases, the higher production volumes and insufficient recycling effort under both models lead to a sharp rise in environmental damage.

Figure 2 (c) and 2 (d) illustrates the variation of environmental damage with base demand, and we find that when the intensity of recycling competition is relatively low, as in

Figure 2 (c), the damage to the environment may appear to decline as base demand rises, because higher base demand enhances the scope for firms to take marketing and profitability actions, which strengthens the recycling behavior of the firms, and thus reduces the damage to the environment. However, when the intensity of recycling competition is higher, as in

Figure 2(d), a larger market base triggers greater environmental pollution because firms have less incentive to recycle and a higher share of new products in product manufacturing.

6.2. Marketing Cost Sharing

Marketing cost-sharing contracts are commonly employed in real-world business practices [

40,

44]. In this section, we examine a supply chain scenario where one party undertakes promotional efforts while the other party proposes a cost-sharing contract, and we analyze its impact on overall supply chain performance. We introduce an exogenous parameter,

, to represent the cost-sharing ratio.

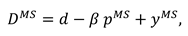

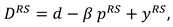

6.2.1. Under Model M

In this subsection, we analyze the retailer’s share of the marketing costs when the manufacturer undertakes marketing efforts. Consequently, the manufacturer’s profit function can be expressed as follows:

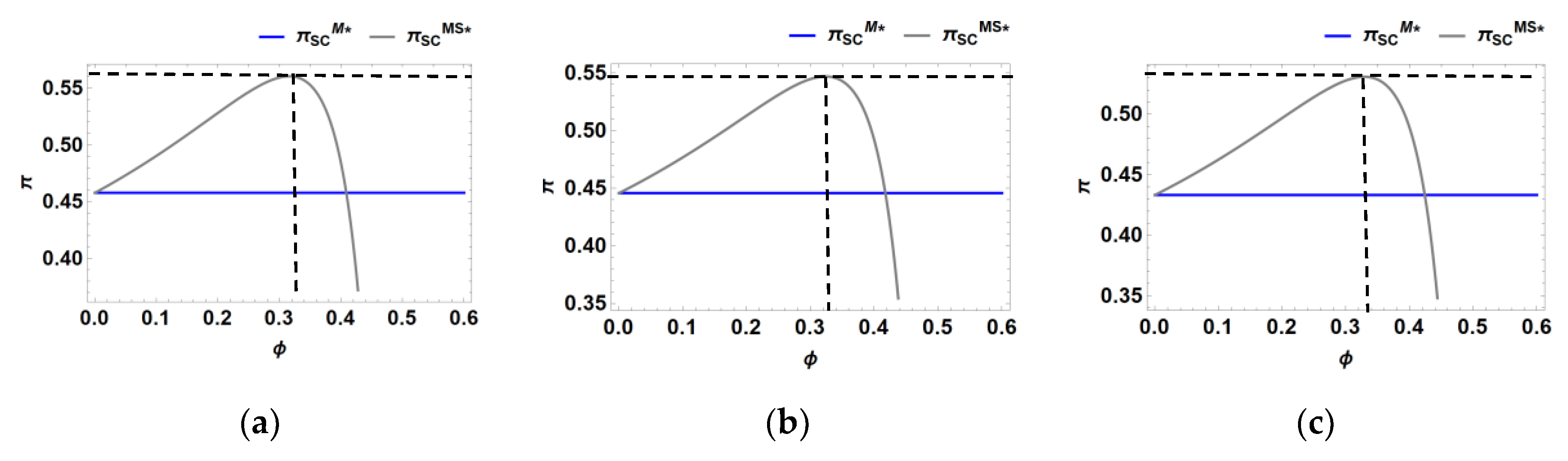

The

Figure 3 below illustrates the variation in overall supply chain profit with respect to the cost-sharing proportion

across two scenarios: manufacturer undertaking marketing efforts (Model M) and retailer sharing the cost of the manufacturer’s marketing efforts (Model MS).

From

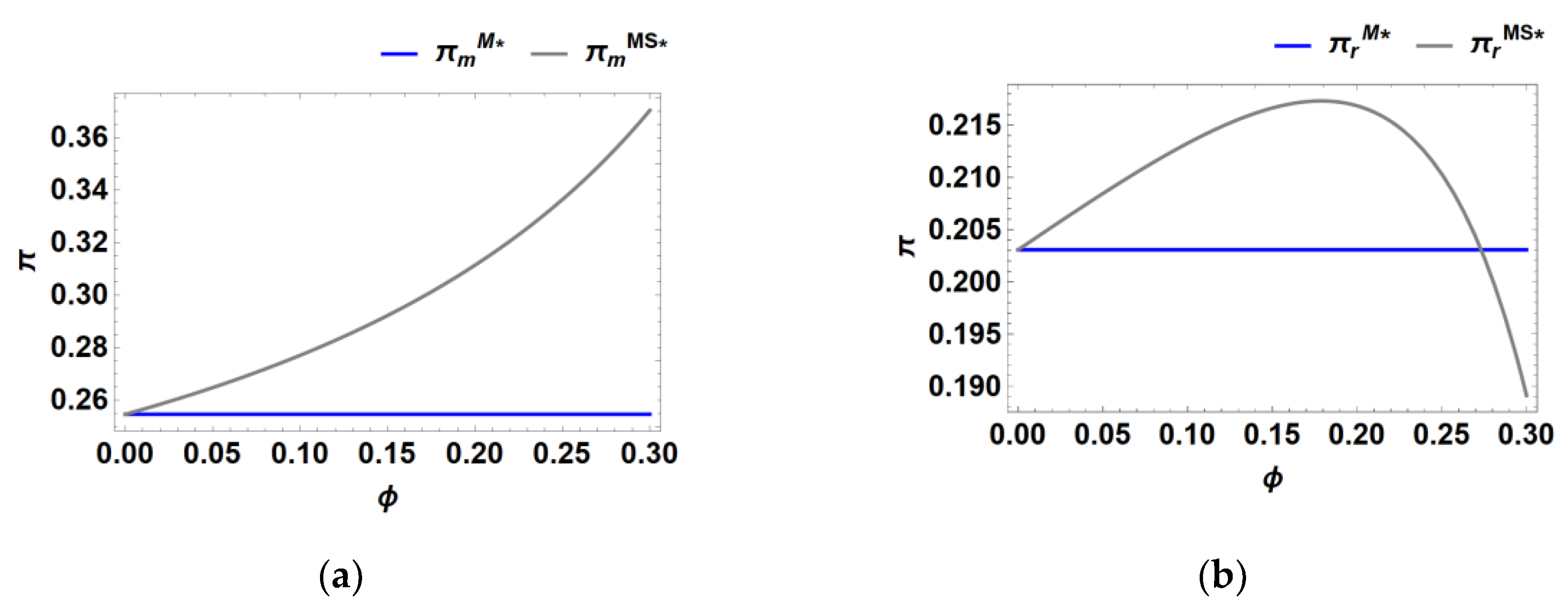

Figure 3 above, we observe that when a manufacturer engages in marketing promotions, there is always an optimal cost-sharing ratio that enhances the profitability of the entire supply chain. Moreover, this optimal ratio increases as the intensity of recycling competition grows. Next, we examine whether the retailer is willing to bear this cost-sharing arrangement and whether the manufacturer is inclined to accept it under natural conditions. Using α = 0.7, we illustrate the variation in (a) the manufacturer's profit and (b) the retailer's profit with respect to the cost-sharing ratio, considering scenarios where the manufacturer conducts promotions and the retailer participates in cost sharing.

The

Figure 4 indicates that the retailer is willing to share the manufacturer's marketing costs at a rate lower than a certain value of

, and the manufacturer is consistently willing to accept this cost sharing. This finding demonstrates that cost sharing by the retailer, when the manufacturer conducts promotions, can enhance profitability for both parties.

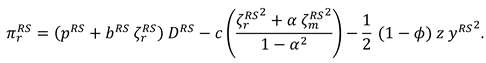

6.2.2. Under Model R

In this subsection, we analyze the manufacturer’s share of the marketing costs when the retailer undertakes marketing efforts. Consequently, the manufacturer’s profit function can be expressed as follows:

The

Figure 5 illustrates the variation in overall supply chain profit with respect to the cost-sharing proportion across three scenarios: a retailer undertaking marketing efforts (Model R), a centralized supply chain engaging in marketing efforts (Model C), and a manufacturer sharing the cost of the retailer’s marketing efforts (Model RS).

From

Figure 5, we observe that for the entire supply chain, an optimal cost-sharing ratio always exists that enhances the supply chain's performance compared to the scenario without cost sharing. However, this performance remains lower than that of a centralized supply chain. Additionally, the optimal subsidy ratio increases as the intensity of recycling competition rises.

Next, we analyze whether, under natural conditions, the manufacturer is willing to share the retailer’s costs and whether the retailer is inclined to accept the manufacturer’s cost-sharing proposal. The following figures illustrate (a) the manufacturer's profit and (b) the retailer's optimal profit under Models R and RS, respectively, when α = 0.7.

The

Figure 6 reveals an interesting dynamic: while the manufacturer shows a willingness to engage in marketing cost-sharing with the retailer, the retailer is reluctant to accept such an arrangement. This reluctance stems from the fact that when the manufacturer shares marketing costs, it gains greater influence over the retailer's marketing decisions. Moreover, as the supplier holds a first-mover advantage, it can leverage this position to increase its own profits by raising the wholesale price, ultimately reducing the retailer's profitability. Consequently, under natural circumstances, cooperation involving the manufacturer sharing the retailer's marketing costs is unlikely to occur unless the manufacturer is compensated with an additional fixed payment.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretic Contributions

Marketing in the forward channel and recycling competition in the reverse channel are integral components of CLSCs and exhibit a dynamic interplay that influences the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the system. Previous studies have predominantly examined marketing in the forward channel and recycling competition in the reverse channel as separate entities. However, in this paper, we integrate these two components into a unified framework, providing a holistic perspective on their interdependence and mutual influence. Our paper advances the theory of marketing strategy selection for manufacturers and retailers in CLSCs by incorporating an analysis of four distinct marketing models. In addition, this paper explores the potential for optimizing supply chains and enhancing the performance of supply chain members through the implementation of marketing cost-sharing contracts.

7.2. Main Results and Managerial Insights

Our main results are as follows:

- (1)

Implementing marketing measures consistently leads to higher profits for the manufacturer, retailer, and the overall supply chain compared to scenarios where no marketing efforts are undertaken. However, the manufacturer consistently prefers the retailer to undertake marketing efforts. In contrast, the retailer's strategic preference varies based on the intensity of recycling competition. Specifically, the retailer prefers the manufacturer to handle marketing when the competition intensity is low, whereas the retailer opts to undertake its own marketing efforts when the competition intensity is high.

- (2)

Retailer-led marketing leads to higher prices, greater marketing efforts, increased demand, enhanced recycling efforts and lower wholesale price compared to manufacturer-led marketing. However, buyback price of the recycled materials remains unaffected by which party undertakes the marketing. In addition, the environmental impact of different models is influenced by the underlying demand. As base demand increases, the order of models with the lowest environmental damage shifts progressively: no marketing, marketing by manufacturers, and marketing by retailers.

- (3)

Higher competitive intensity in recycling results in reduced recycling efforts, lower buyback prices, decreased wholesale prices, and diminished marketing efforts. However, in the absence of marketing, prices increase as recycling competition intensity rises. Conversely, when marketing is present, prices decrease as recycling competition intensity increases. As the intensity of competition rises, manufacturers' margins always fall, while retailers' margins tend to rise, and the margins of the entire supply chain rise and then fall. The impact of recycling competition intensity on environmental damage depends on base demand: it decreases with higher competition intensity when base demand is low but increases when base demand is high.

- (4)

There is always an optimal marketing cost-sharing ratio that enhances supply chain profits. When the manufacturer undertakes marketing, cost-sharing improves the profits of both the retailer and the manufacturer. However, when the retailer handles marketing, cost-sharing reduces the retailer's profits, necessitating a contract for coordination.

Our results provide the following key managerial insights:

- (1)

An optimal level of recycling competition, rather than excessively high or low intensity, enhances the profitability of the entire supply chain by strengthening the retailer’s position in recycling and balancing the power dynamics between the manufacturer and retailer. Moreover, at this appropriate level of competition, manufacturers and retailers are more likely to align their marketing strategies, such as delegating marketing responsibilities to retailers. Consequently, manufacturers can delegate suitable recycling tasks to retailers, positively impacting the overall supply chain.

- (2)

Under more efficient retailer-led marketing, retailers are often reluctant to accept profit-sharing arrangements from manufacturers, as such agreements increase the manufacturer's control over the market. However, manufacturers can achieve further improvements in overall profitability by implementing a sharing contract that includes a fixed subsidy.

7.3. Limitations and Future Studies

This paper has the following limitations: First, it examines scenarios where the manufacturer and retailer make separate marketing efforts but does not consider cases where they engage in simultaneous marketing. Second, it focuses on a single supply chain in the forward channel, while the increasing prevalence of manufacturers with their own direct marketing channels could be explored in future research. Finally, the demand in this paper is assumed to be fixed, leaving room for further investigation into marketing strategies under uncertain demand conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.T., L.W. and Z.L.; methodology, X.T., Z.L. and L.W.; software, X.T. and L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.T. and Z.L.; writing—review and editing, X.T. and L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and the anonymous review team for their highly constructive comments on earlier versions of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Proof of proposition 1. The first-order derivatives of

to

and

can be shown as:

The Hessian matrix of

is

Since

,

. To ensure that

is jointly concave with respect to

and

, we assume

. Further, by solving

and

we can obtain as follows:

Then, substitute (A4) and (A5) into Equation (5) and taking the first-order derivatives of

to

and

, we obtain

The Hessian matrix of

is

, We assume

to ensure that

is jointly concave with respect to

and

. By solving

and

, we obtain

Substitute (A9) and (A10) into Equation (5), we obtain

Then we find the

increases when

increases between

, and decreases when

increases over

. Then we obtain the optimal recycling price:

Substituting Equation (A12) to relative functions, we can obtain the optimal wholesale price, recycling efforts, sales price and profits.

Substituting the optimal decisions into

we can obtain the obtain the optimal consumer surplus and environment damage are

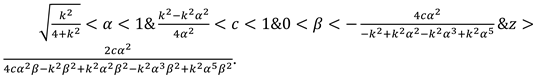

In order for the concave conditions of

and

and the non-negative demand function to be satisfy, we need the bellow conditions.

The proof of Proposition 1 is completed.

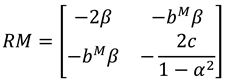

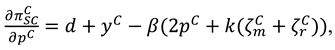

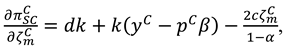

Proof of proposition 2. The first-order derivatives of

to

and

can be shown as:

The Hessian matrix of

is

Since

,

. To ensure that

is jointly concave with respect to

and

, we assume

. Further, by solving

and

we can obtain as follows:

Then, substitute (A17) and (A18) into Equation (18) and taking the first-order derivatives of

to

,

and

, we obtain

The Hessian matrix of

is

We assume

,

>0

to ensure that

is jointly concave with respect to

,

and

. By solving

,

and

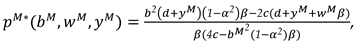

, we obtain

Substitute (A23), (A24) and (A25) into Equation (16), we obtain

Then we find the

increases when

increases between

, and decreases when

increases over

. Then we obtain the optimal recycling price:

Substituting Equation (A27) to relative functions, we can obtain the optimal wholesale price, recycling efforts, marketing efforts, sales price and profits.

Substituting the optimal decisions into

we can obtain the obtain the optimal consumer surplus and environment damage are

In order for the concave conditions of

and

and the non-negative demand function to be satisfy, we need the bellow conditions

The proof of Proposition 2 is completed.

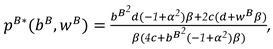

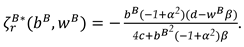

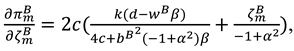

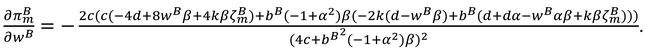

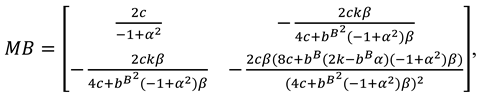

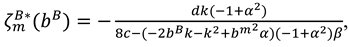

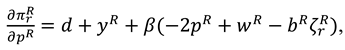

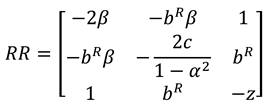

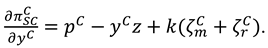

Proof of Proposition 3. The first-order derivatives of

to

,

and

can be shown as:

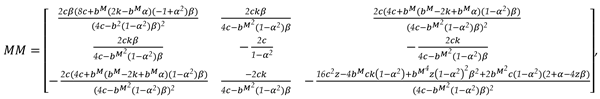

The Hessian matrix of

is

Since

,

,

. To ensure that

is jointly concave with respect to

,

and

, we assume

and

. Further, by solving

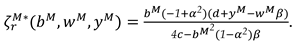

,

and

we can obtain as follows:

Then, substitute (A33), (A34) and (A35) into Equation (32) and taking the first-order derivatives of

to

and

, we obtain

The Hessian matrix of

is

We assume

,

to ensure that

is jointly concave with respect to

and

. By solving

and

, we obtain

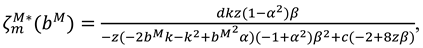

Substitute (A39) and (A40) into Equation (28), we obtain

Then we find the

increases when

increases between

, and decreases when

increases over

. Then we obtain the optimal recycling price:

Substituting Equation (A27) to relative functions, we can obtain the optimal wholesale price, recycling efforts, marketing efforts, sales price and profits.

Substituting the optimal decisions into

we can obtain the obtain the optimal consumer surplus and environment damage are

In order for the concave conditions of

and

and the non-negative demand function to be satisfy, we need the bellow conditions

The proof of Proposition 3 is completed.

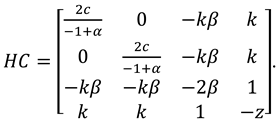

Proof of Proposition 4. The first-order derivatives of

to

,

,

and

can be shown as:

The Hessian matrix of

is

,

, We assume

,

to ensure that

is jointly concave with respect to

,

,

. By solving

,

and

, we can obtain as follows

Further, substituting Equation (A49), (A50), (A51) and (A52) into relative functions, we can obtain the optimal profit.

Substituting the optimal decisions into

we can obtain the obtain the optimal consumer surplus and environment damage are

In order for the concave conditions of

and the non-negative demand function to be satisfy, we need the bellow conditions

The proof of Proposition 4 is completed.

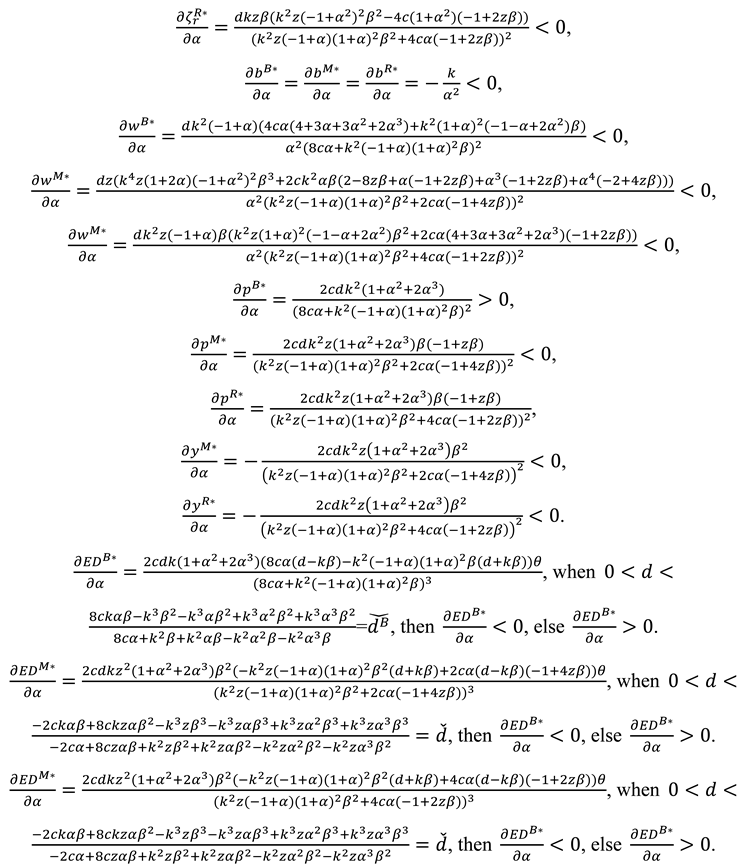

Proof of Corollary 1. The comparison of optimal wholesale price and sales price in different models are follows:

According to the conditions of (A17), (A34), (A52), (A66), we obtain the follow results.

The proof of Corollary 1 is completed.

Proof of Corollary 2. The comparison of optimal recycling price and recycling efforts in different models are follows:

According to the conditions of (A17), (A34), (A52), (A66), we obtain the follow results.

It is evident that

.

The proof of Corollary 2 is completed.

Proof of Corollary 3. The comparison of optimal marketing effort and demand in different models are follows:

According to the conditions of (A17), (A34), (A52), (A66), we obtain the follow results.

Therefore . The proof of Corollary 3 is completed.

Proof of Corollary 4. The comparison of optimal profits of manufacturer and supply chain in different models are follows:

According to the conditions of (A17), (A34), (A52), (A66), we obtain the follow results.

Therefore . The proof of Corollary 4 is completed.

Proof of Corollary 5. The comparison of optimal consumer surplus and environment in different models are follows:

According to the conditions of (A17), (A34), (A52), (A66), we obtain the follow results.

Due to in this paper, consumer surplus is half the square of demand, thus the size of consumer surplus under different models is the same as the demand relationship in the corollary i.e.

.

Proof of Corollary 6. The partial derivatives of the relevant variables with respect to the intensity of recycling competition are as follows:

The proof of Corollary 6 is completed.

References

- Kodak. Kodak Sustainability Report 2023. Available online: https://www.kodak.com/content/pdfs/Kodak-Sustainability-Report-2023-EN.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- HP. HP Planet Partners. Available online: https://www.hp.com/cn-zh/sustainable-impact/planet-product-recycling.html (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Atasu, A.; Sarvary, M.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Remanufacturing as a marketing strategy. Manage. Sci. 2008, 54, 1731–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide, Jr; V. Daniel, R.; Luk, N. Van, Wassenhove. OR FORUM—The evolution of closed-loop supply chain research. Oper. Res. 2009, 57, 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Opinions on Promoting the Development of the Remanufacturing Industry. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2010-05/31/content_1617310.htm (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Matsui, K. Optimal timing of acquisition price announcement for used products in a dual-recycling channel reverse supply chain. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 300, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K. Dual-recycling channel reverse supply chain design of recycling platforms under acquisition price competition. Int. J. Product. Econ. 2023, 259, 108769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Mao, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y. Quality and Pricing Decisions in a Dual-Channel Closed-Loop Supply Chain Considering Imperfect Product Recycling. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apple. Trade In. Available online: https://www.apple.com.cn/shop/trade-in (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Chen, C.K.; Akmalul’Ulya, M.; Mancasari, U.A. A study of product quality and marketing efforts in closed-loop supply chains with remanufacturing. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybern. 2018, 50, 4870–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Li, K.W.; Wang, Z.J. Pricing decisions in closed-loop supply chains with marketing effort and fairness concerns. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 6710–6731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Li, L.; Yang, Z. Perceived social green preference: The motivation mechanism of inducing green behaviour. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Y. Pricing strategies for bundled products considering consumers’ green preference. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 344, 130962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, G. Research on the Impact Mechanism of Self-Quantification on Consumers’ Green Behavioral Innovation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Yao, F.; Xiu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X. Multi-period closed-loop supply chain network equilibrium: Perspective of marketing and corporate social responsibility. IEEE Access 2020, 9, 1495–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, W.; Du, S.; Sun, X. How to achieve targeted advertising with the e-commerce platform’s membership system? Omega 2025, 130, 103156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nike. Move to Zero. Available online: https://www.nike.com.cn/sustainability (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaskan, R.C.; Bhattacharya, S.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Closed-loop supply chain models with product remanufacturing. Manage. Sci. 2004, 50, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegoz, M.; Kaya, O.; Bayindir, Z.P. A comparison of pure manufacturing and hybrid manufacturing–remanufacturing systems under carbon tax policy. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 294, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Chu, J.; Jin, L. Recycling channel selection and coordination in dual sales channel closed-loop supply chains. Appl. Math. Model. 2021, 95, 484–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, B.C.; Chakraborty, A.; Maiti, T. Pricing and return product collection decisions in a closed-loop supply chain with dual-channel in both forward and reverse logistics. J. Manuf. Syst. 2017, 42, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasu, A.; Toktay, L.B.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. How collection cost structure drives a manufacturer's reverse channel choice. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2013, 22, 1089–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.H.; Wang, C.X.; Zhao, Y. Closed-loop supply chain models for a high-tech product under alternative reverse channel and collection cost structures. Int. J. Product. Econ. 2014, 156, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, J. Decision-Making in Remanufacturing Supply Chains: Game Theory Analysis of Recycling Models and Consumer Value Perception. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Yang, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M. Dual-channel closed loop supply chains: Forward channel competition, power structures and coordination. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 3510–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalapathy, P.; Unnissa, M.M. Extended Warranty and Retailing Strategies in CLSC Competition with (Re) manufacturing Manufacturer. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Q.P. The closed-loop supply chain network with competition and design for remanufactureability. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 105, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.T.; Ren, M.L. Closed-loop supply chain coordination strategy for the remanufacture of patented products under competitive demand. Appl. Math. Model. 2016, 40, 6243–6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini-Motlagh, S.M.; Nouri-Harzvili, M.; Johari, M.; Sarker, B.R. Coordinating economic incentives, customer service and pricing decisions in a competitive closed-loop supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Song, M.; Lee, L.H.; Ching, W.K. Analysis for strategy of closed-loop supply chain with dual recycling channel. Int. J. Product. Econ. 2013, 144, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, N.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, B. Competitive collection under channel inconvenience in closed-loop supply chain. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 275, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; He, Q.; Jiang, B. Hybrid closed-loop supply chains with competition in recycling and product markets. Int. J. Product. Econ. 2019, 217, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wahab, M.I.M.; Goh, M. Channel leadership and performance for a closed-loop supply chain considering competition. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 175, 103151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Collection decisions and coordination in a closed-loop supply chain under recovery price and service competition. J. Ind. Manage. 2022, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, H.; Hang, T.; Meng, Q. How to Choose Recycling Mode between Monopoly and Competition by Considering Blockchain Technology? Sustainability 2024, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, N.; Jiang, B. Hybrid closed-loop supply chain with different collection competition in reverse channel. Int. J. Product. Econ 2024, 276, 109371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleizadeh, A.A.; Sane-Zerang, E.; Choi, T.M. The effect of marketing effort on dual-channel closed-loop supply chain systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybern. 2016, 48, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Guo, X. Green product supply chain contracts considering environmental responsibilities. Omega 2019, 83, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wu, H.; Sethi, S.P.; Zhang, X. Contracting green product supply chains considering marketing efforts in the circular economy era. Int. J. Product. Econ. 2021, 234, 108041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Han, H.; Hou, L.; Wang, H. Pricing and effort decisions in a closed-loop supply chain under different channel power structures. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2043–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Meng, L.; Huang, Z. Pricing and Sales Effort Decisions in a Closed-Loop Supply Chain Considering the Network Externality of Remanufactured Product. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Li, K.W.; Wang, Z.J. Pricing decisions in closed-loop supply chains with marketing effort and fairness concerns. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 6710–6731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S. Coordination of a socially responsible supply chain using revenue sharing contract. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2014, 67, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).