Submitted:

29 April 2025

Posted:

30 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Cases

2.2. Recording and Analysis of Continuous Electrocardiogram

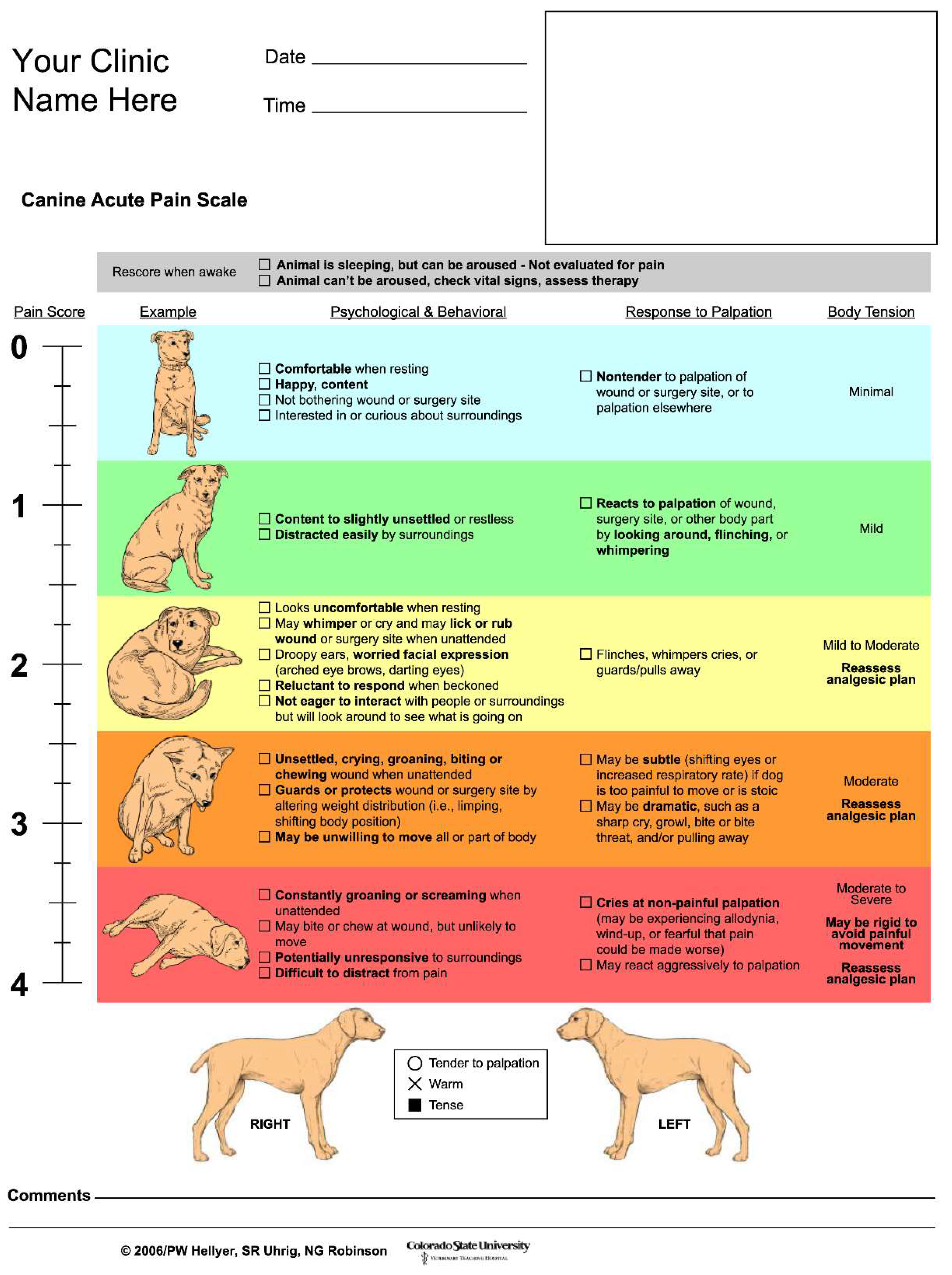

2.3. Postoperative Pain Evaluation

2.4. Electrocardiographic Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muir, W.M. Acid–base physiology. In Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia: The Fifth Edition of Lumb and Jones, 5th ed.; Grimm, K.A., Lamont, L.A., Tranquilli, W.J., Greene, S.A., Robertson, S.A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Ames, Iowa, USA, 2015; pp. 357–371. [Google Scholar]

- Mosley, C.A. Anesthesia equipment. In Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia: The Fifth Edition of Lumb and Jones, 5th ed.; Grimm, K.A., Lamont, L.A., Tranquilli, W.J., Greene, S.A., Robertson, S.A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Ames, Iowa, USA, 2015; pp. 23–85. [Google Scholar]

- Stanway, G.W.; Taylor, P.M.; Brodbelt, D.C. A preliminary investigation comparing pre-operative morphine and buprenorphine for postoperative analgesia and sedation in cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2002, 29, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demetriou, J.L.; Geddes, R.F.; Jeffery, N.D. Survey of pet owners’ expectations of surgical practice within first opinion veterinary clinics in Great Britain. J Small Anim Pract 2009, 50, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodbelt, D.C.; Blissitt, K.J.; Hammond, R.A.; Neath, P.J.; Young, L.E.; Pfeiffer, D.U.; Wood, J.L.N. The risk of death: the confidential enquiry into perioperative small animal fatalities. Vet Anaesth Analg 2008, 35, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, J.R.; Knowles, T.G.; Lascelles, B.D.X.; Murrell, J.C. Prescription of perioperative analgesics by UK small animal veterinary surgeons in 2013. Vet Rec 2015, 176, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, P.A.; Hillier, L.M. The enigma of pain in children: an overview. Pediatrician 1989, 16, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, M.; Rodan, I.; Griffenhagen, G.; Kadrlik, J.; Petty, M.; Robertson, S.; Simpson, W. 2015 AAHA/AAFP pain management guidelines for dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2015, 51, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, L.L.; Scott, E.M.; Nolan, A.M.; Reid, J.; Welsh, E.; Flaherty, D. Comparison of three methods used for assessment of pain in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998, 212, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagiwa, M.; Sakakura, Y. [Evaluation of throat discomfort with visual analogue scale (VAS)]. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho 1994, 97, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, R.D.; Lauritsen, J.; Ovesen, O.; Overgaard, S. The verbal rating scale is reliable for assessment of postoperative pain in hip fracture patients. Pain Res Treat 2015, 2015, 676212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, J. , Nolan, A.M., Hughes, J.M., Lascelles, B.D.X., Pawson, P., Scott, E.M. Development of the short-form Glasgow Composite Measure Pain Scale (CMPS-SF) and derivation of an analgesic intervention score. Anim Welf 2007, 16, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breivik, H.; Borchgrevink, P.C.; Allen, S.M.; Rosseland, L.A.; Romundstad, L.; Breivik Hals, E.K.; Kvarstein, G.; Stubhaug, A. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth 2008, 101, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akyrou, D.; Plati, C.; Baltopoulos, G.; Anthopoulos, L. Pain assessment in acute myocardial infarction patients. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 1995, 11, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, L.L.; Scott, E.M.; Nolan, A.M.; Reid, J.; Welsh, E. Relationship between physiological factors and clinical pain in dogs scored using a numerical rating scale. J Small Anim Pract 1998, 39, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, M.; Lombardi, F.; Guzzetti, S.; Rimoldi, O.; Furlan, R.; Pizzinelli, P.; Sandrone, G.; Malfatto, G.; Dell’Orto, S.; Piccaluga, E. Power spectral analysis of heart rate and arterial pressure variabilities as a marker of sympatho-vagal interaction in man and conscious dog. Circ Res 1986, 59, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccirillo, G.; Ogawa, M.; Song, J.; Chong, V.J.; Joung, B.; Han, S.; Magrì, D.; Chen, L.S.; Lin, S.F.; Chen, P.S. Power spectral analysis of heart rate variability and autonomic nervous system activity measured directly in healthy dogs with tachycardia-induced heart failure. Heart Rhythm 2009, 6, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amar, D.; Zhang, H.; Miodownik, S.; Kadish, A.H. Competing autonomic mechanisms precede the onset of postoperative atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003, 42, 1262–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövebrant, J. Surgical stress response in dogs diagnosed with pyometra undergoing ovariohysterectomy. Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences), Uppsala, Sweden, 2013.

- Höglund, O.V.; Lövebrant, J.; Olsson, U.; Höglund, K. Blood pressure and heart rate during ovariohysterectomy in pyometra and control dogs: a preliminary investigation. Acta Vet Scand 2016, 58, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKune, C.M.; Murrell, J.C.; Nolan, A.M.; White, K.L.; Wright, B.D. Nociception and pain. In Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia: The Fifth Edition of Lumb and Jones, 5th ed.; Grimm, K.A., Lamont, L.A., Tranquilli, W.J., Greene, S.A., Robertson, S.A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Ames, Iowa, USA, 2015; pp. 584–626. [Google Scholar]

- Sessler, D.I. Perioperative thermoregulation and heat balance. Lancet 2016, 387, 2655–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morino, M.; Masaki, C.; Seo, Y.; Mukai, C.; Mukaibo, T.; Kondo, Y.; Shiiba, S.; Nakamoto, T.; Hosokawa, R. Non-randomized controlled prospective study on perioperative levels of stress and dysautonomia during dental implant surgery. J Prosthodont Res 2014, 58, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonell, W.N.; Kerr, C.L. Physiology, pathophysiology, and anesthetic management of patients with respiratory disease. In Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia: The Fifth Edition of Lumb and Jones, 5th ed.; Grimm, K.A., Lamont, L.A., Tranquilli, W.J., Greene, S.A., Robertson, S.A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Ames, Iowa, USA, 2015; pp. 513–558. [Google Scholar]

- Teramoto, M. [The effect of hemorrhagic acute anemia on wound healing]. Japanese Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 1980, 26, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y.; Hara, S. The effect of electro-acupuncture stimulation on rhythm of autonomic nervous system in dogs. J Vet Med Sci 2008, 70, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Mori, N.; Mitajiri, R.; Jiang, Z. [Study of mental stress evaluation based on analysis of heart rate variability]. Journal of Life Support Engineering 2010, 22, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, T.; Harada, T.; Mitsui, T.; Inokuma, M.; Hashimoto, M.; Miyauchi, M.; Murano, H.; Shibutani, Y. Spectral analysis of circadian rhythms in heart rate variability of dogs. Am J Vet Res 2001, 62, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bille, C.; Auvigne, V.; Libermann, S.; Bomassi, E.; Durieux, P.; Rattez, E. Risk of anesthetic mortality in dogs and cats: an observational cohort study of 3546 cases. Vet Anaesth Analg 2012, 39, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, K.A. , Kronen, P.W., Lascelles, B.D.X., Nolan, A., Robertson, S., Steagall, P.V. Guidelines for recognition, assessment and treatment of pain. J Small Anim Pract 2014, 55, E10–E68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case No. | Breed | Age | Sex |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Labrador Retriever | 11y | Male |

| 2 | Shiba Inu | 6y 2m | Female |

| 3 | Chihuahua | 14y 1m | Spayed Female |

| 4 | Miniature Dachshund | 11y | Male |

| 5 | French Bulldog | 9y 5m | Male |

| 6 | Beagle | 12y 11m | Spayed Female |

| 7 | Pug | 12y 10m | Spayed Female |

| 8 | Miniature Dachshund | 11y 7m | Male |

| 9 | Papillon | 11y | Castrated Male |

| 10 | Pembroke Welsh Corgi | 13y 3m | Spayed Female |

| 11 | French Bulldog | 8m | Castrated Male |

| 12 | Miniature Dachshund | 10y 7m | Spayed Female |

| 13 | Shih Tzu | 10y 10m | Castrated Male |

| 14 | American Cocker Spaniel | 9y 11m | Castrated Male |

| 15 | Jack Russell Terrier | 2y 11m | Female |

| 16 | Toy Poodle | 9y 3m | Spayed Female |

| 17 | Cavalier King Charles Spaniel | 5y 1m | Male |

| Case No. | Types of surgery | Expected degree of pain |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Partial mandibular resection / mandibular lymph node resection | Maximum |

| 2 | Body surface mast cell tumor resection / superficial cervical and axillary lymph node resection | Maximum |

| 3 | Partial maxillary resection | Maximum |

| 4 | Partial maxillary resection / mandibular lymph node resection | Maximum |

| 5 | Cholecystectomy / castration | Maximum |

| 6 | Liver mass removal / splenectomy | Maximum |

| 7 | Partial mandibular resection / mandibular lymph node resection / medial retropharyngeal lymph node resection | Maximum |

| 8 | Partial mandibular resection / mandibular lymph node resection | Maximum |

| 9 | Cataract extraction(OU) | Mild to moderate |

| 10 | Cherry eye repositioning (OU) / conjunctival flap surgery(OD) | Mild to moderate |

| 11 | Femoral head and neck resection | Moderate to severe |

| 12 | Mammary gland tumor resection | Mild to moderate |

| 13 | Splenectomy / intraperitoneal lymph node resection / cystolithiasis extraction | Maximum |

| 14 | Knee joint extra-articular braking method(lateral suture) | Maximum |

| 15 | Phacoemulsification and aspiration (OS) / intraocular lens implantation(OS) | Mild to moderate |

| 16 | Knee joint extra-articular braking method (lateral suture) | Maximum |

| 17 | Phacoemulsification and aspiration (OS) / intraocular lens implantation(OS) | Mild to moderate |

| Case No. | Anesthetic protocol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Premedication | Induction agent | Maintenance anesthesia/Intraoperative analgesics | Post-operative analgesics | ASA classification | |

| 1 | Mid-Ket-Fent-Atr-Melx | P | OS/RFK | Fent-Ket | 2 |

| 2 | Mid-Ket-Fent-Atr-Melx | P | OS/RFK | Fent-Ket | 2 |

| 3 | Mid-Ket-Fent-Atr | P | OS/RFK | Fent-Ket | 2 |

| 4 | Mid-Ket-Fent-Atr-Melx | P | OS/RFK | Fent-Ket | 2 |

| 5 | Mid-Ket-Fent-Atr-Melx | P | OS/RFK | Fent-Ket | 2 |

| 6 | Mid-Ket-Fent-Atr | P | OS/RFK | Fent-Ket | 2 |

| 7 | Mid-Ket-Fent-Atr-Melx | P | OS/RFK | Fent-Ket | 2 |

| 8 | Mid-Ket-Fent-Atr-Melx | P | OS/RFK | Fent-Ket | 2 |

| 9 | Mid-Btr-Lid | P | OS/BL | Btr | 2 |

| 10 | Mid-Mor-Melx | P | OS | Bupre | 3 |

| 11 | Mid-Fent-Atr-Melx | P | P-TIVA/RF | Fent | 2 |

| 12 | Mid-Tram | A | OS | Bupre | 2 |

| 13 | Mid-Ket-Fent-Atr-Melx | P | OS/RFK | Fent-Ket | 2 |

| 14 | Mid-Ket-Fent-Atr-Melx | P | OS/RFK | Fent-Ket | 2 |

| 15 | Mid-Btr-Lid | P | P-TIVA/BL | Btr | 1 |

| 16 | Mid-Ket-Fent-Atr-RBCX | P | OS/RFK | Fent-Ket | 2 |

| 17 | Mid-Btr-Lid | P | P-TIVA/BL | Btr | 2 |

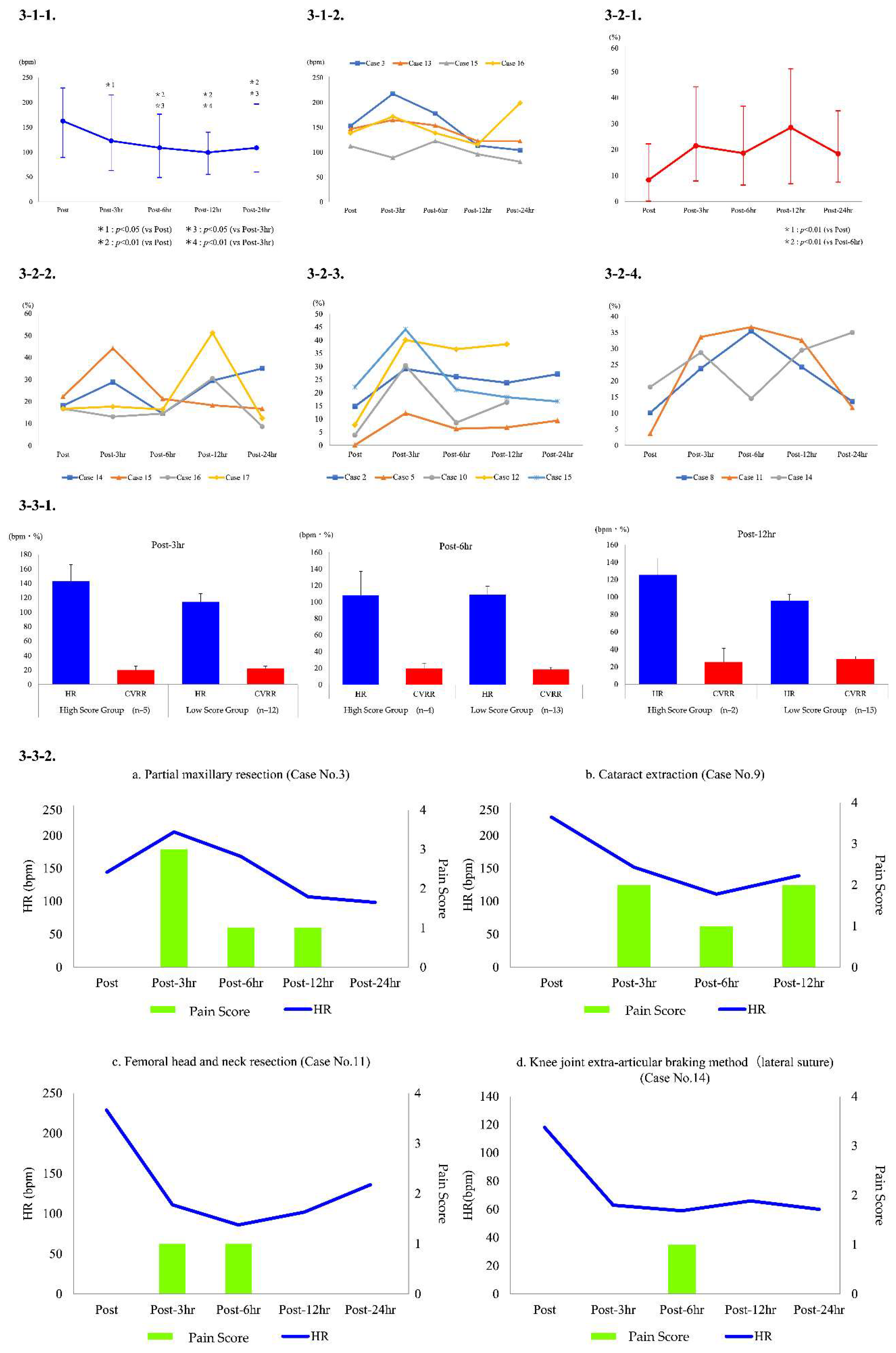

| Case No. | Presence or absence of additional postoperative analgesia and administered drug information | The Dog’s Acute Pain Scale | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-3h | Post-6h | Post-12h | Post-24h | ||

| 1 | Absent | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Absent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | Present; Fent i.v., ACE i.v. ×3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | Absent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | Absent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | Absent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | Absent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | Absent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | Absent | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| 10 | Absent | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 11 | Absent | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | Absent | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 13 | Absent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | Absent | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | Absent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | Absent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 17 | Absent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).