1. Introduction

Metastases remain the major cause of cancer-related deaths [

1]. Drug development for metastatic disease has concentrated on treating the primary tumor in neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting to prolong the time for metastatic relapse. This has worked to some extent, but the problem remains and still today metastases remain incurable and are driving low survival rates in stage IV patients across cancer types. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop therapies that can effectively and specifically treat metastases.

Bone metastases are a major problem in most common cancers including, but not limited to, breast and prostate cancer [

2] where bone metastases remain incurable and a significant cause of mortality [

3,

4]. Deaths in bone metastatic patients are almost entirely due to skeletal complications [

5]. Bone metastases can be classified into osteolytic and osteoblastic (or mixed) metastases, depending on whether the cancer cells induce increased bone resorption or bone formation, respectively [

3].

Bone metastases account for about 75% of metastases in advanced breast cancer, being the most common metastatic site, followed by lung, liver and brain [

6]. Breast cancer bone metastases are typically osteolytic, accounting for 80% of breast cancer bone metastases, about 20% being osteoblastic [

3]. However, both osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions are typically observed in patients, but the type is classified based on the dominant type.

More than 90% of advanced prostate cancer patients develop bone metastases [

4], and prostate cancer is classified as a bone disease because of the high skeletal involvement. Prostate cancer bone metastases are typically osteoblastic, inducing a rapid growth of pathologic new bone [

3].

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a disease of the bone marrow that results in osteolytic bone loss [

7] associated with problems similar to bone metastases in breast cancer, and also remain incurable [

8]. Nearly 90% of MM patients develop myeloma bone disease associated with high risk of fracture and bone pain [

9].

In addition to the high mortality associated with bone metastases, they also account for many other complications that decrease the quality of life, including bone pain, hypercalcemia and increased risk of fractures [

2,

3]. The increased risk of fractures is related to all cancer types regardless of whether the cancer-induced bone changes are osteolytic or osteoblastic. Bone pain caused by metastases can become constant and very severe at end-stage disease [

10].

Upon diagnosis of bone metastases, treatment begins with the same chemotherapy that the patient has received as first-line treatment. Importantly, many current cancer treatments, including but not limited to aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer and androgen-deprivation therapy in prostate cancer, further increase bone loss and therefore make bone-related complications even worse [

11]. Cancer- and treatment-induced osteolytic bone loss can be treated with zoledronic acid in breast cancer [

12] and MM [

13]. Denosumab, another agent that prevents bone loss, is more commonly used in prostate cancer bone metastases. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that zoledronic acid and denosumab were comparable in increasing overall survival and disease progression, but denosumab was more effective in reducing the number of and increasing the time to develop skeletal-related adverse events, and with less observed toxicities [

14].

Because of the high unmet medical need driven by the high mortality rate and decreased quality of life, new treatment options are urgently needed, specifically with focus on bone metastases and MM bone disease. A key challenge is the limited recognition of the importance of bone metastases in drug development, which may result from several factors—particularly the perception that primary tumor models are more convenient, readily available and most commonly used in early stages of drug development. However, utilizing appropriate preclinical bone metastasis models would: 1) allow studying effects of therapies directly in bone metastatic microenvironment, 2) mimic the important clinical features of bone metastases, and 3) allow assessing effects on cancer-induced bone pain and quality of life.

A major limitation of most preclinical models is the lack of correct metastatic tumor microenvironment, especially in traditional cell culture and organoid models [

1], but also in the commonly used preclinical animal models. To get the most predictive and translational data from preclinical animal studies, the tumors should be growing in their natural tissue microenvironment. Bone is a peculiar organ and bone cells have many interactions with tumor cells, commonly explained by a concept called ‘vicious cycle of bone metastasis’ [

15]. This concept means that cancer cells increase bone turnover, resulting in an increased release of tumor growth promoting factors from the bone, leading to increased tumor growth. However, the vicious cycle does not include the vital role of immune cells in bone metastasis. Osteo-immuno-oncology (OIO) concept emphasizes the complex interactions between tumor, bone and immune cells [

16]. These new insights are critical for developing more effective therapeutic strategies that address all aspects of cancer. Integrating preclinical OIO models [

17] into translational research enables a more accurate representation of human disease, offering better prospects for treatment. This approach facilitates the identification of novel therapeutic targets and the development of treatments that can effectively modulate both the immune response and bone remodeling processes. As our understanding of these complex interactions deepens, integrating OIO into drug development becomes essential for addressing the multifaceted nature of bone metastatic diseases across various cancer types.

The most clinically relevant preclinical model for studying bone metastases involves tumors growing in bone microenvironment of either immunocompetent or immunodeficient mice, depending on the specific indication and research requirements. Methods to induce metastasis to bone are described for example by Kähkönen and co-workers [

18,

19]. In the current study, we established preclinical immunocompetent bone metastasis models for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), the most common cancers affected by bone metastases, and an immunodeficient model for MM bone disease, with focus of the model development being on clinical resemblance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Information, Welfare and Housing

Animal studies were conducted at PharmaLegacy Laboratories, a preclinical contract research organization (Shanghai, China), under ethical approval of local ethics committee, and all studies have been approved by the PharmaLegacy Laboratories IACUC.

Four to five weeks old mice were used in the studies (Shanghai Jihui Laboratory Animal Care, see strain information in

Table 1). The mice had ad libitum access to rodent food (irradiated, Xietong Organism biological technology co., Ltd., China) and in-house produced water.

Animal welfare was monitored daily, and the mice were weighed 2-3 times per week to monitor their wellbeing.

2.2. Intratibial Inoculation

The cell lines, their growth conditions and the number of inoculated cells are provided in

Table 1 below:

Table 1.

Cell line information.

Table 1.

Cell line information.

| |

Name of cell line |

Growing condition |

Number |

Mouse strain |

| |

4T1-luc

(mouse TNBC cells) |

RPMI-1640, 10% FBS |

1 x 10^4 |

BALB/c |

| |

RM-1-luc

(mouse CRPC cells) |

RPMI-1640, 10% FBS |

5 x 10^5 |

C57BL/6 |

RPMI-8226-luc

(human MM cells) |

RPMI-1640, 10% FBS |

1 x 10^6 |

NPG |

In all models, the cancer cells were adjusted to a volume of 10 µl in PBS, and slowly injected into the left tibia of each mouse anesthetized with 3 – 4% isoflurane. A fine needle was used to gently drill a hole through the proximal tibia to allow access to bone marrow cavity. When the needle was expected to be in the correct position, an X-ray image was taken to verify the correct location. After verifying the correct position, the cells were slowly inoculated into the bone marrow. After the inoculation, animal welfare was carefully monitored and pain medication was given for 2 consecutive days following the inoculation.

In the RM-1 model, the mice were castrated before the cancer cell inoculation. Appropriate pain medication was given 3 days after the surgery. The cancer cells were inoculated 7 days after the castration, when the mice had recovered from the surgery.

2.3. Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI)

Tumor growth in bone was monitored by Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) using IVIS Lumina XRMS (Revvity). Thirty minutes before imaging, the mice received intraperitoneal injection of luciferin, and 30 minutes after each luciferin injection, the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and kept sleeping for the duration of the imaging. For all mice, the bioluminescence intensity (p/s), indicating tumor burden, was analyzed at each imaging timepoint.

2.4. X-Ray Imaing

Cancer-induced bone changes were visualized by X-ray imaging under isoflurane anesthesia. One image visualizing both hind limbs was taken, and the un-inoculated leg was used as a control for the cancer-induced bone changes observed in the inoculated leg. The extent of cancer-induced bone changes was analyzed by scoring the lesions from 1 to 5, where score 1 was given to mice with clear yet small tumor-induced changes and score 5 was given to mice with major cancer-induced bone destruction.

2.5. Bone Pain

Bone pain was analyzed by mechanical allodynia using Von Frey filament test. For consecutive 3 days before the first measurement, the mice were allowed to adopt to the measurement surroundings. During the measurements, the mice were placed in a transparent plastic box with a wire mesh base. The following procedure was used: 1) In each test, a von Frey force of 0.4 g was perpendicularly delivered to the mid-plantar region of hindpaw for about 3-5 s; 2) If the mouse responded by withdrawing its paw, the next lower force was used; 3) If the paw was not withdrawn, the next higher force was used. This procedure was followed until the threshold level between a non-response and paw-withdrawal was determined. The force levels used were between 0.02 – 4 g. The 50% paw withdrawal threshold was calculated as follows:

Where Xf is the force of the last von Frey used, δ = 0.31 is the average interval (in log units) between the von Frey monofilaments, and k depends upon the pattern of the withdrawal responses.

3. Results

3.1. TNBC Bone Metastasis Model

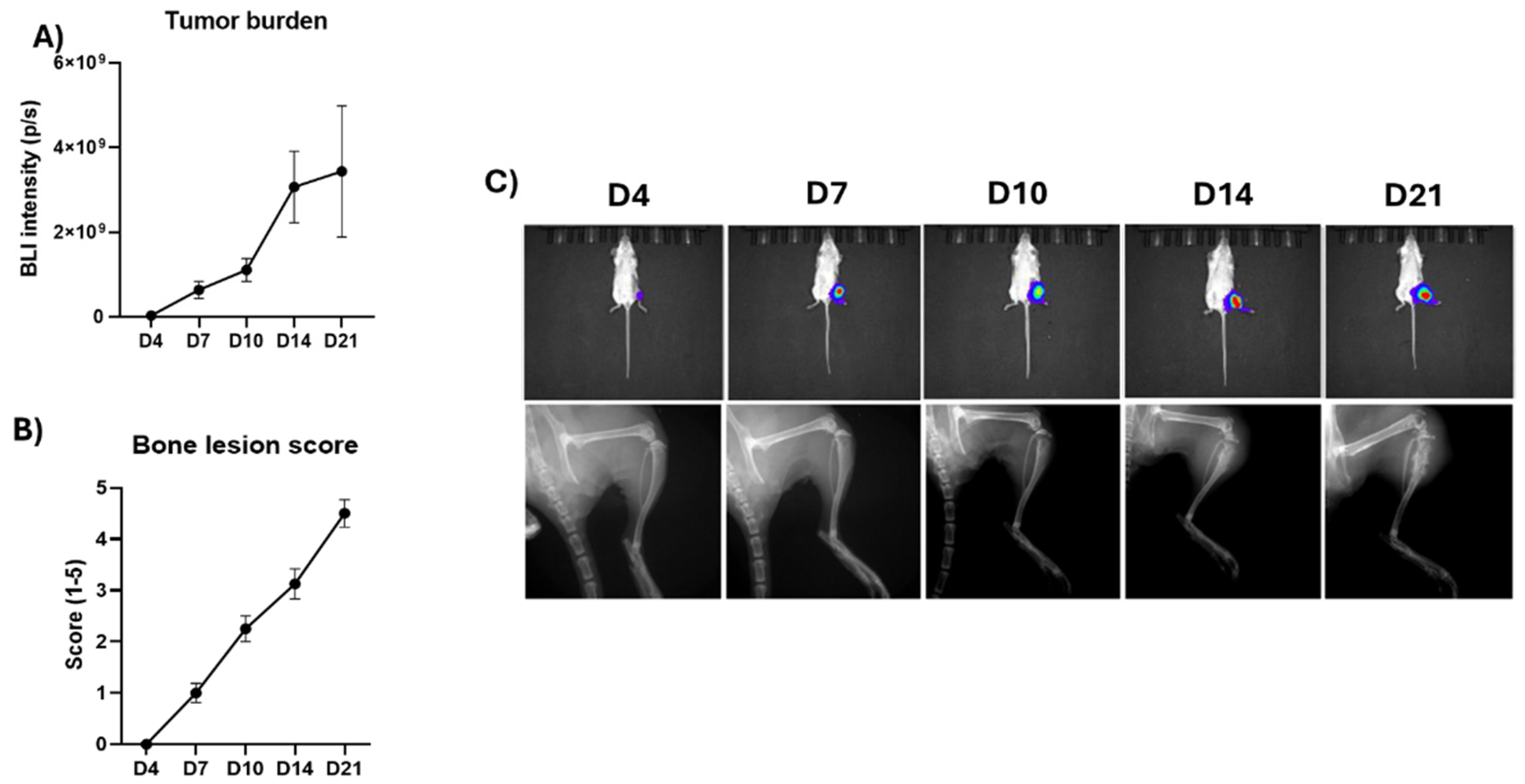

In the TNBC bone metastasis model using 4T1 mouse TNBC cells, 100% tumor take rate was observed. The bone metastases formed and grew rapidly, reaching a high tumor burden at the endpoint of the study (

Figure 1A,C upper row). 4T1 cells induced mainly osteolytic bone loss, and cancer-induced bone changes were observed earliest at day 7, and extensive bone loss at day 21 (

Figure 1B,C lower row). Due to the high tumor burden and extensive bone loss, the study was terminated 21 days after the cancer cell inoculation.

3.2. CRPC Bone Metastasis Model

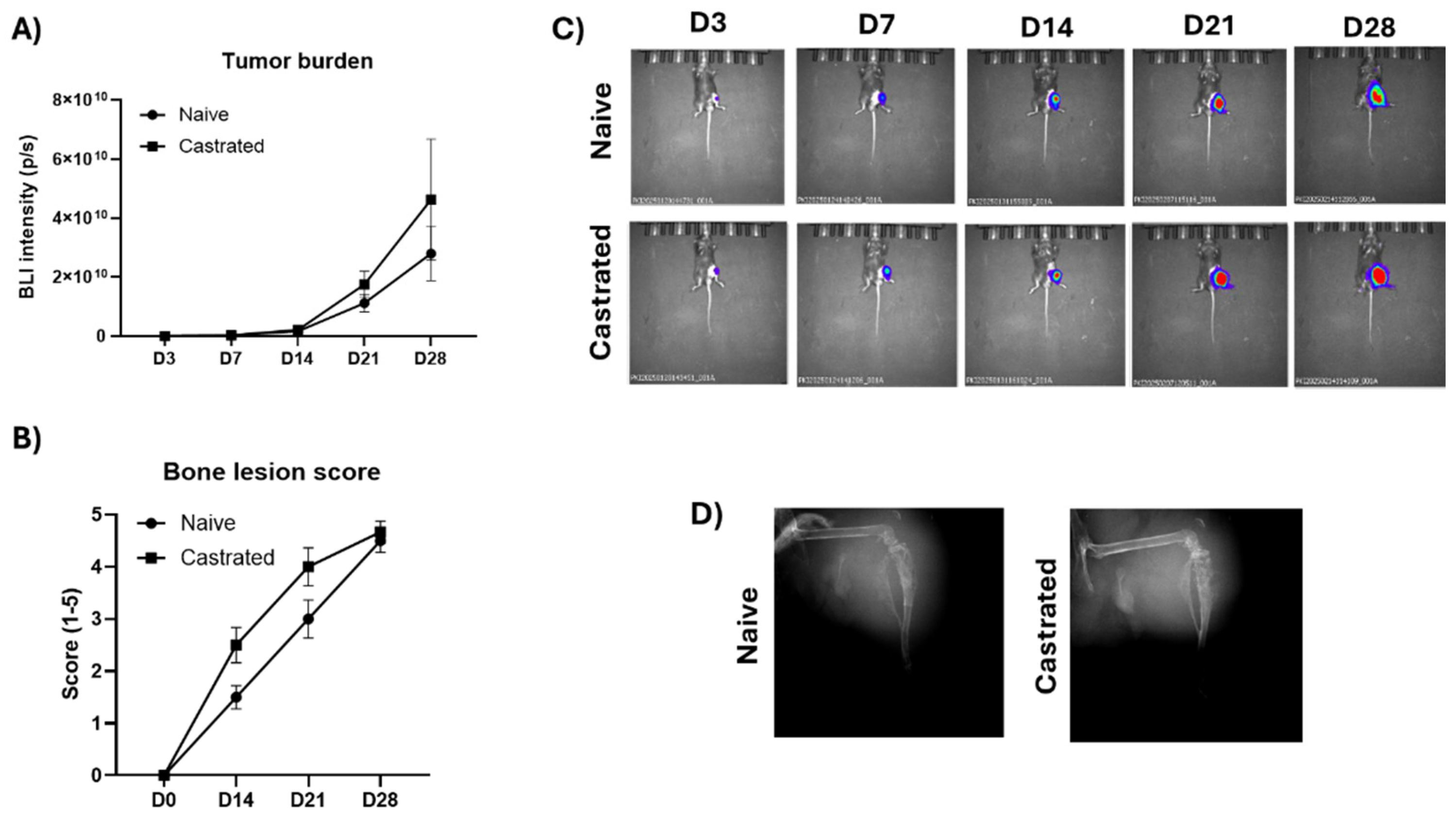

In the CRPC bone metastasis model using RM-1 mouse CRPC cells, 100% tumor take rate was observed in naïve and castrated mice. Extensive tumor growth was observed from day 14 forward and high tumor burden a the endpoint at day 28 (

Figure 2A,C). RM-1 cells induced mixed bone lesions including both osteolytic bone loss and osteoblastic rapid growth of pathologic new bone. Cancer-induced bone changes were observed earliest at day 14 and extensive bone loss at day 28 (

Figure 2B,D). Due to the high tumor burden and extensive bone loss, the study was terminated 28 days after the cancer cell inoculation. There were no differences in tumor growth or cancer-induced bone loss between naïve and castrated mice.

3.3. MM Bone Disease Model

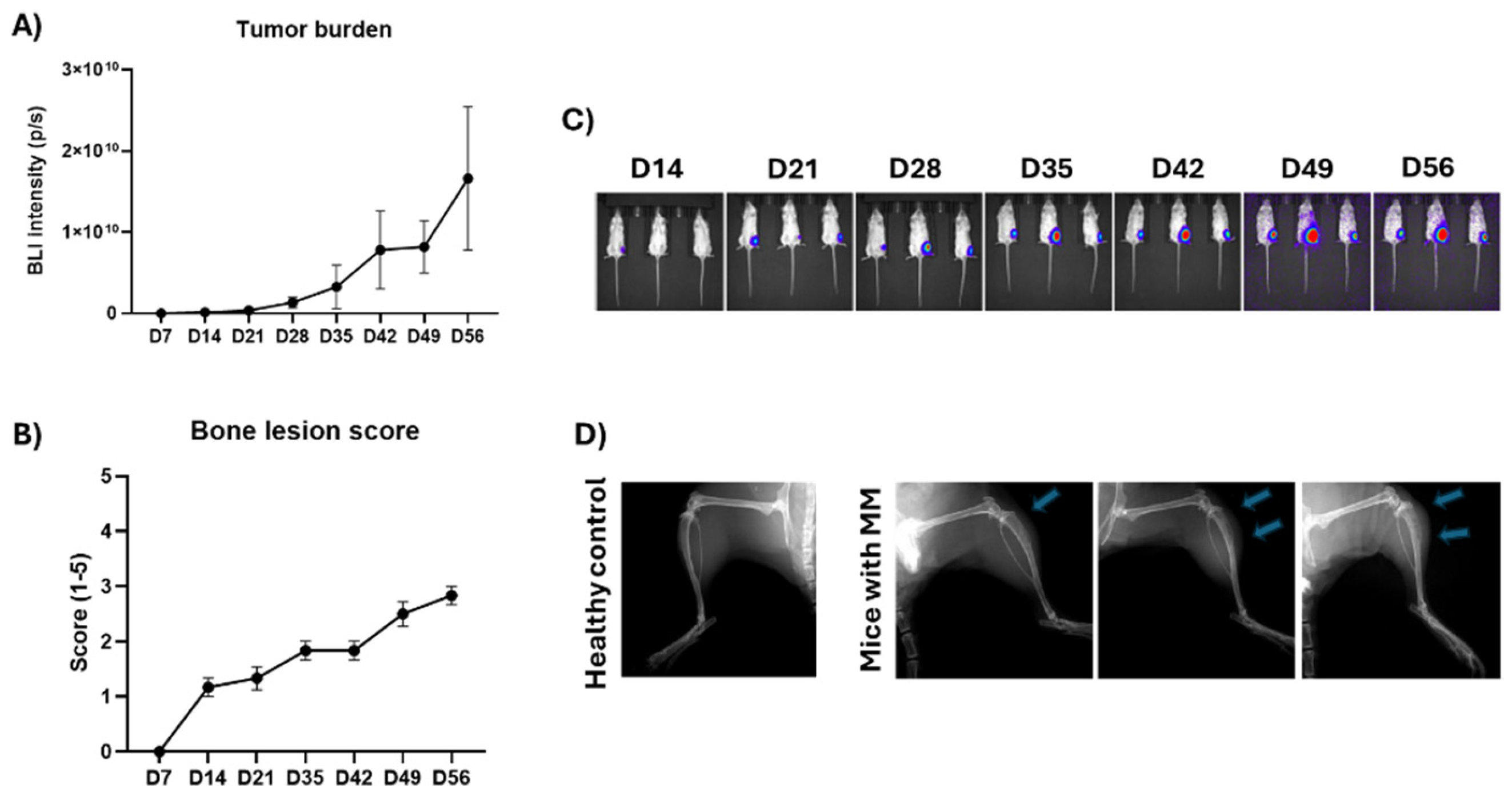

In the MM bone disease model using RPMI-8226 human MM cells, 100% tumor take rate was observed. Bone metastases formed early and grew steadily during the study (

Figure 3A,C). RPMI-8226 MM cells induced osteolytic bone loss that remained moderate during the study period. Cancer-induced bone changes were observed ealiest at day 14 and in all mice at day 21 (

Figure 3B,D). The mice were followed for 100 days until their clinical condition relapsed.

3.4. Cancer-Induced Bone Pain

Cancer-induced bone pain was analyzed in the TNBC model at days 4, 7, 14 and 21 and in the CRPC model at days 4, 7, 14, 21 and 28. These schdules followed the timepoints of tumor burden and cancer-induces bone loss analysis. Bone pain was detected earliest at day 4, and it gradually increased towards the end of the studies. A significant correlation was observed for bone pain with tumor burden and cancer-induces bone loss (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

Clinically relevant preclinical bone metastasis models for breast and prostate cancer and MM bone disease were established. These models mimic important clinical features, including tumor-induced bone changes and pain, that are observed in bone metastatic TNBC and CRPC patients and MM patients with bone disease.

Efficacy of new cancer therapies is commonly tested in subcutaneous mouse models, where tumor cells are inoculated under the skin. This model system is useful for addressing some research questions, but it is not clinically relevant for studying efficacy on metastases with unique tumor microenvironment. Tissue microenvironment in metastastic organs has a strong impact on growth of metastases. Especially in bone metastases, tumor, immune and bone cells have many underlying interactions that help to promote the growth of bone metastases through the novel OIO concept. Such interactions can only be achieved when the tumors are growing in bone microenvironment. Testing the efficacy of a new therapy in preclinical bone metastasis models will therefore provide the most clinically relevant readout for the efficacy of the the therapy on bone metastases in patients.

In the preclincial models that were developed in this study, we observed similar effects of tumors on bone than are observed in bone metastatic patients. TNBC and MM cells induced ostelytic bone metastases and CRPC cells induced ostaoblastic bone metastases, indicating that the tumor cells are inteacting and secreting similar factors to promote bone effects that are also present in corresponding bone metastastic patients.

The quality of life is an important factor in advanced cancer patients. Bone metastastic patients experience increased risk of fractures, hypercalcemia and especially bone pain. In this study, we analyzed bone pain of the animals with a validated method commonly used for example in osteoarthritis research. Bone pain has been less studied in oncology studies, but the mechanisms have been reviewed for example by Jimenz-Andrade and co-workers [

10]. In this study, we analyzed bone pain in breast and prostate cancer models and observed that the magnitude of bone pain correlated strongly with tumor burden and cancer-induced bone loss.

The established models can be modified to address different research questions such as prevention of tumor growth or treatment of established tumors. For studying prevention of bone metastases, treatment is started at the same time with the tumor cell inoculation. In this study, we establised timepoints for studying efficacy on established tumors, where treatment is started when the tumors have already been formed and are growing. It has been speculated that there may be disrepancies between early treatment of micrometastases in animal models and treatment of macrometastases in patients [

1]. For studying effects of therapies on macrometastases, treatment should be started even later, but the maximum length of the study needs to be considered.

Preclinical bone metastasis models have been only considered for different bone-targeting therapies or therapies with high affinity to bone. Good examples of such approaches are radium-223, an approved therapy for bone metastatic CRPC, and bisphophonates, a class of compounds that inhibit activity of bone resorbing osteoclasts and help to prevent cancer-induced bone loss in breast cancer and MM [

1]. However, bone metastasis models should be widely used in any cancer drug development program for therapies in cancer indications with high probability to metastasize to bone such as breast and prostate cancer and MM, but also for example in lung and colorectal cancer. This would support new target identification and help to get clinically relavant information on efficacy of therapies on bone metastases and shorten the gap between preclinical and clincial development, considering that most patients included in clinical trials are late-stage patiens with bone metastastic disease.

5. Conclusions

In this study we established clinically relevant preclinical bone metastasis models for TNBC, CRPC and MM bone disease. The established models closely recapitulate key clinical features, including tumor-induced bone remodeling and pain, offering a clinically meaningful platform for evaluating therapeutic efficacy in bone metastatic setting. Compared to conventional subcutaneous models, these bone-specific models better reflect the tumor microenvironment and the critical tumor–bone–immune interactions fundamental to disease progression, as highlighted in the emerging field of OIO. The ability to assess cancer-induced bone pain adds further translational value. Importantly, these models are adaptable for both prevention and intervention studies. Given the current lack of therapies specifically targeting bone metastases, these models provide a critical tool to bridge the translational gap. These preclinical models should be integrated into oncology drug development to ensure that therapeutic strategies effectively address the complex challenges of bone metastatic disease across a range of cancer indications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization TEK, JB, JMH; methodology, RY, YX; validation JW; formal analysis TEK, RY; investigation RY, YX; resources JW, JMH; data curation, JW; writing—original draft preparation TEK; writing—review and editing JB, JMH; visualization, TEK; supervision, JW, JB, JMH; project administration TEK, RY; funding acquisition, JW, JMH. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Business Finland, Tempo grant.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BLI |

Bioluminescence imaging |

| CRPC |

Castration-resistant prostate cancer |

| MM |

Multiple myeloma |

| OIO |

Osteoimmuno-oncology |

| TNBC |

Triple-negative breast cancer |

References

- Ganesh, K.; Massagué, J. Targeting metastatic cancer. Nat Med 2021, 27, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornetti, J.; Welm, A.L.; Stewart, S.A. Understanding the Bone in Cancer Metastasis. J Bone Miner Res 2018, 33, 2099–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.J.; Pollock, C.B.; Kelly, K. Mechanisms of cancer metastasis to the bone. Cell Res 2005, 15, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNatale, A.; Fatatis, A. The Bone Microenvironment in Prostate Cancer Metastasis. Adv Exp Med Biol 2019, 1210, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coleman, R.E. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res 2006, 12 Pt 2, 6243s–6249s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Song, X.; Yang, Q. Metastatic heterogeneity of breast cancer: Molecular mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Semin Cancer Biol 2019, 60, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, Z.S.; Kim, E.B.; Raje, N. Bone Disease in Multiple Myeloma: Biologic and Clinical Implications. Cells 2022, 11, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-delCastillo, M.; Chantry, A.D.; Lawson, M.A.; Heegaard, A.M. Multiple myeloma-A painful disease of the bone marrow. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2021, 112, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eda, H.; Santo, L.; Roodman, D.G.; Raje, N. Bone Disease in Multiple Myeloma. Cancer Treat Res 2016, 169, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Andrade, J.M.; Mantyh, W.G.; Bloom, A.P.; Ferng, A.S.; Geffre, C.P.; Mantyh, P.W. Bone cancer pain. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010, 1198, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.A.; Guise, T.A. Cancer treatment-related bone disease. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 2009, 19, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, C.L. Bone-modifying Agents (BMAs) in Breast Cancer. Clin Breast Cancer 2021, 21, e618–e630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terpos, E.; Zamagni, E.; Lentzsch, S.; Drake, M.T.; García-Sanz, R.; Abildgaard, N.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Schjesvold, F.; de la Rubia, J.; Kyriakou, C.; Hillengass, J.; Zweegman, S.; Cavo, M.; Moreau, P.; San-Miguel, J.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Munshi, N.; Durie, B.G.M.; Raje, N. Bone Working Group of the International Myeloma Working Group. Treatment of multiple myeloma-related bone disease: recommendations from the Bone Working Group of the International Myeloma Working Group. Lancet Oncol 2021, 22, e119–e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wajda, B.G.; Ferrie, L.E.; Abbott, A.G.; Elmi Assadzadeh, G.; Monument, M.J.; Kendal, J.K. Denosumab vs. Zoledronic Acid for Metastatic Bone Disease: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cancers 2025, 17, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guise, T.A. The vicious cycle of bone metastases. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2002, 2, 570–572. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kähkönen, T.E.; Halleen, J.M.; Bernoulli, J. Osteoimmuno-Oncology: Therapeutic Opportunities for Targeting Immune Cells in Bone Metastasis. Cells 2021, 10, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kähkönen, T.E.; Halleen, J.M.; Bernoulli, J. 2022 Preclinical Osteoimmuno-Oncology Models to Study Effects of Immunotherapies on Bone Metastasis. Chapter in the book Animal Models for the Development of Cancer Immunotherapy, pages 167-209. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Kähkönen, T.E.; Bernoulli, J.; Halleen, J.M. Novel and Conventional Preclinical Models to Investigate Bone Metastasis. Curr Mol Bio Rep 2019, 5, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähkönen, T.E.; Halleen, J.M.; Bernoulli, J. Immunotherapies and Metastatic Cancers: Understanding Utility and Predictivity of Human Immune Cell Engrafted Mice in Preclinical Drug Development. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).