1. Introduction

Bone metastases can develop in patients with all types of cancer at advanced stages. As previously reported, the incidence of bone metastasis varies according to the cancer type; lung, prostate, breast, and kidney cancers have high incidences [

1,

2]. Reports have also shown that bone metastasis is associated with poor prognosis [

3,

4,

5,

6]. For example, in prostate cancer, 5-year survival rates were 56% and 3% in patients without and with bone metastases, respectively [

3]. Moreover, in men with bone metastasis minus skeletal related events (SRE), hazard ratios (HR) for mortality were 6.6 (95% CI: 6.4–6.9), and in men with bone metastasis plus SRE they were 10.2 (95% CI: 9.8-10.7) [

4]. Similarly, in breast cancer, the 5-year survival rates were 75.8% and 8.3% in patients without and with bone metastases, respectively [

5]. Bone metastasis impairs physical function and quality of life (QOL) in patients with cancer due to multiple complications such as pathological fractures, paralysis due to spinal cord compression, and disuse syndrome. Hence, proper treatment of bone metastasis is essential to achieve a good QOL in patients with cancer [

7].

Bone-modifying agents (BMA) have been commonly used in patients with bone metastasis to prevent or treat SRE, although it is unclear whether the management of bone metastasis improves survival [

8,

9,

10,

11]. In the present study, we investigated whether BMA improved post-bone metastasis survival.

2. Materials and Methods

This study included 539 patients with cancer and bone metastasis who underwent rehabilitation at the Osaka International Cancer Institute between 2018 and 2020. The date of bone metastasis was obtained from medical records.

The cancer types were classified as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), breast, prostate, kidney, colorectal, bone and soft tissue, urinary tract, pancreas, esophagus, head and neck, liver, small cell lung cancer (SCLC), stomach, skin, thyroid, uterus, and biliary tract. The urinary tract included the bladder, renal pelvis, ureters, and urethra. Uterine cancer comprised the uterine cervix, uterine corpus, and uterine sarcoma. The biliary tract included the gallbladder, bile duct, and the duodenal papillae.

BMA treatments were defined as the administration of zoledronic acid or denosumab at least once after bone metastasis.

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate post-bone metastasis survival. The log-rank test was used for univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis was conducted using the Cox proportional hazards model. Associations of post-bone metastasis survival with age, BMA, cancer type, driver mutation, surgery, and/or radiotherapy for bone metastasis were retrospectively analyzed. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the EZR (64 bit) [

12].

3. Results

Of the 539 patients, 301 were age ≥ 65 years (55.8%) and 238 were < 65 years (44.2%). A total of 304 men (56.4%) and 235 women (43.6%) were included in this study. The primary origin types of cancer were: NSCLC, 105 (19.5%); breast, 84 (15.6%); prostate, 48 (8.9%); kidney, 34 (6.3%); colorectum, 30 (5.6%); bone and soft tissue, 27 (5.0%); urinary tract, 26 (4.8%); pancreas, 23 (4.3%); esophagus, 22 (4.1%); head and neck, 20 (3.7%); liver, 19 (3.5%); SCLC, 19 (3.5%); stomach, 18 (3.3%); skin, 14 (2.6%); thyroid, 11 (2.0%); uterus, 11 (2.0%); biliary tract, 7 (1.3%); and others, 21 (3.9%). Median post-bone metastasis survival largely varied according to cancer type: thyroid, 97.2 months (95% CI: 11.6–N/A [not applicable]); breast, 51.5 months (95% CI: 37.7–69.1); prostate, 47.2 months (95% CI: 30.2–79.3); and kidney, 38.8 months (95% CI: 18.9–85.9); all of which resulted in a longer than 24 month survival (

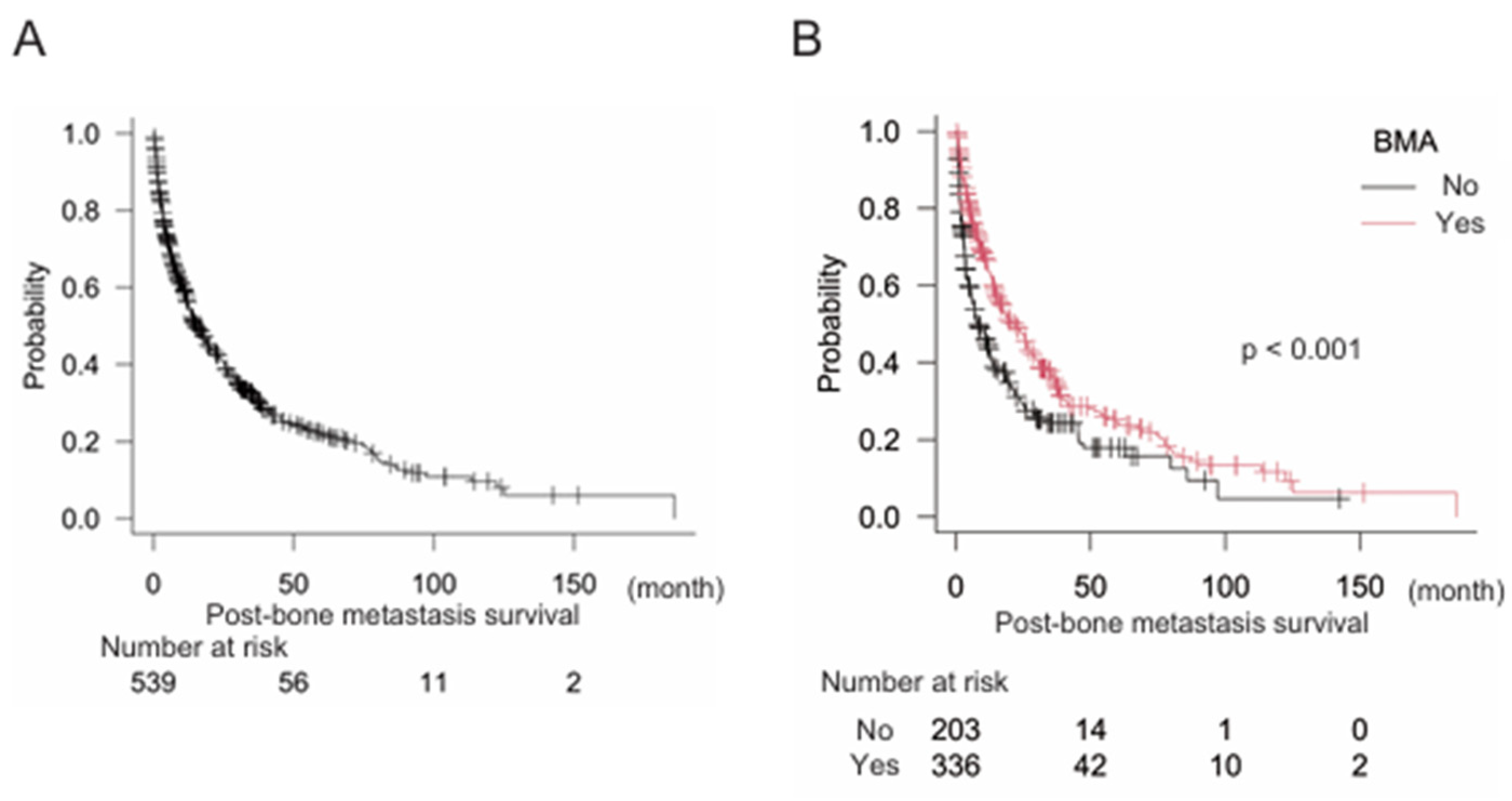

Table 1). In the present study, median post-bone metastasis survival was 15.2 months (95% CI: 12.8–19.2) for the overall population (

Figure 1A). We also analyzed the relationships between post-bone metastasis survival and age, sex, and BMA levels. Age was not significantly associated with post-bone metastasis survival in the overall population (age < 65, n = 238, median post-bone metastasis survival 15.1 months (95% CI: 12.5–19.8); age ≥ 65, n = 301, median post-bone metastasis survival 16.8 months (95% CI: 11.0–22.1) (p = 0.61). Sex and BMA were significant factors related to post-bone metastasis survival in the overall population in the univariate analyses: female, n = 235 median post-bone metastasis survival 26.0 months (95% CI: 19.0–31.0); male, n = 304 median post-bone metastasis survival 11.4 months (95% CI: 10.2–14.2) (p < 0.005); BMA (-) n = 203, median post-bone metastasis survival 7.8 months (95% CI: 5.8–12.5); BMA (+) n = 336, median post-bone metastasis survival 21.9 months (95% CI: 16.1–26.4) (p < 0.001) (

Figure 1B). Of note, multivariate analysis eliminated the significance of sex, but not BMA (

Table 2).

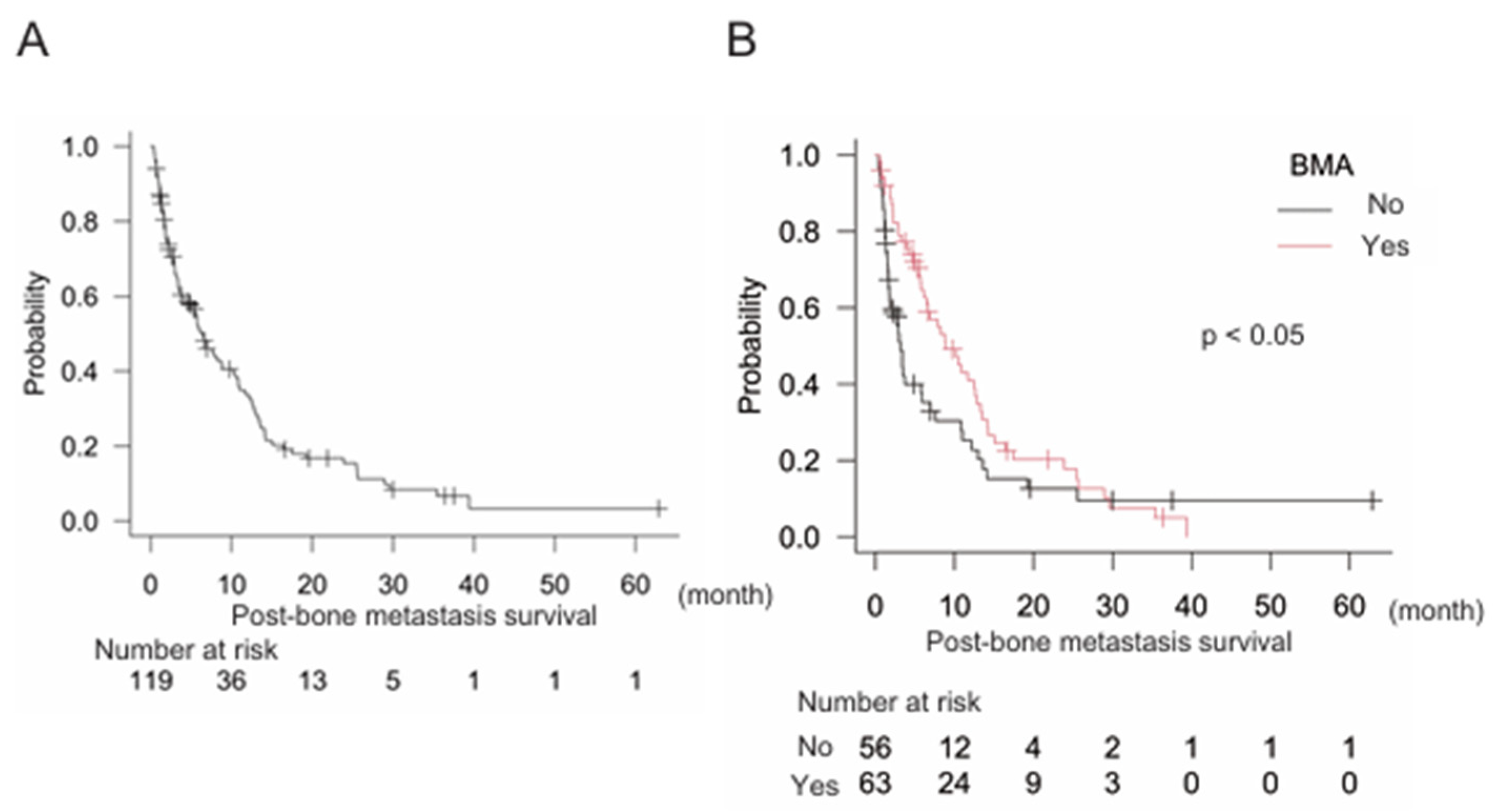

We further aimed to clarify the effects of BMA on post-bone metastasis survival. First, gastrointestinal (GI) cancers were examined and results showed that median post-bone metastasis survival was 6.4 months (95% CI: 4.0–8.8), n = 110 (

Figure 2A). Notably, treatment with BMA was significantly correlated with better post-bone metastasis survival in GI cancers: BMA (-) n = 56, median post-bone metastasis survival 3.1 months (95% CI: 1.7–5.9); BMA (+) n = 63, median post-bone metastasis survival 8.8 months (95% CI: 6.1–12.6) (p < 0.05) (

Figure 2B). Multivariate analysis also indicated that BMA significantly improved post-bone metastasis survival (

Table 3).

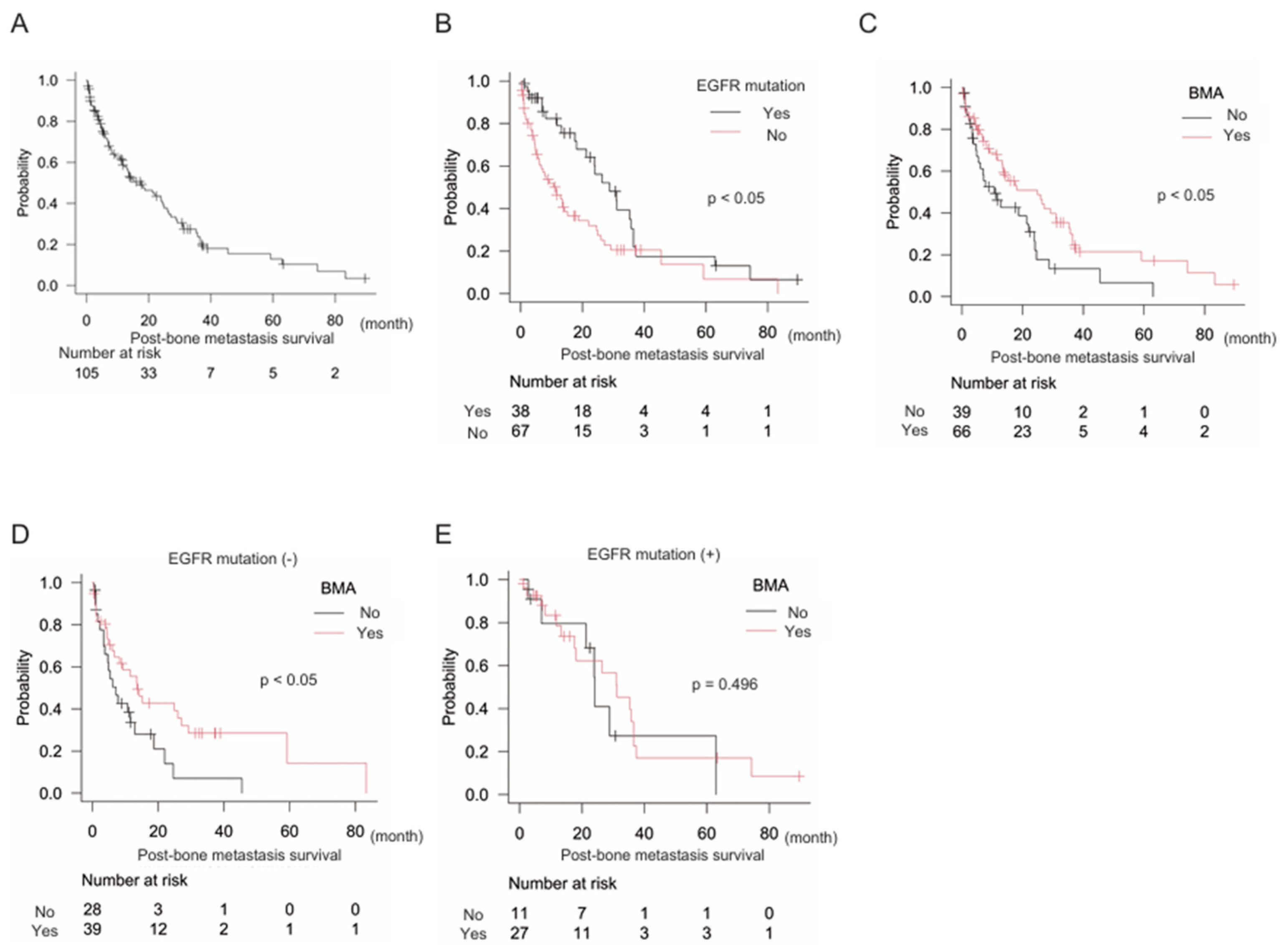

Next, we focused on NSCLC (n = 105), which included 80 (76.2%) adenocarcinomas, 23 (21.9%) squamous cell carcinomas, and two (1.9%) large cell carcinomas. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation was observed in 38 (36.2%) patients. Median post-bone metastasis survival in NSCLC was 17.6 months (95% CI: 11.5–24.6) (

Figure 3A). The EGFR mutation was a positive prognostic marker of post-bone metastasis survival: EGFR mutation (-) n = 67, median post-bone metastasis survival 11.5 months (95% CI: 6.0–15.2); EGFR mutation (+) n = 38, median post-bone metastasis survival 28.8 months (95% CI: 18.1–35.7) (p < 0.05) (

Figure 3B). Furthermore, treatment with BMA was also a positive prognostic indicator: BMA (-) n = 39, median post-bone metastasis survival 10.7 months (95% CI: 4.9–22.0); BMA (+) n = 66, median post-bone metastasis survival 24.9 months (95% CI: 13.3–31.2) (p < 0.05). In subgroup analyses, the EGFR mutation (-) group confirmed the significance of BMA for better post-bone metastasis survival: BMA (-) n = 28, median post-bone metastasis survival 7.2 months (95% CI: 3.4–12.9); BMA (+) n = 39, median post-bone metastasis survival 13.6 months (95% CI: 6.0–27.1) (p < 0.05). However, the EGFR mutation (+) group did not: BMA (-) n = 11, median post-bone metastasis survival 24.1 months (95% CI: 7.0–N/A); BMA (+) n = 27, median post-bone metastasis survival 31.2 months (95% CI: 17.6–36.5) (p = 0.496). The multivariate analysis consistently showed that both EGFR mutations and BMA levels were independent prognostic factors (

Table 4).

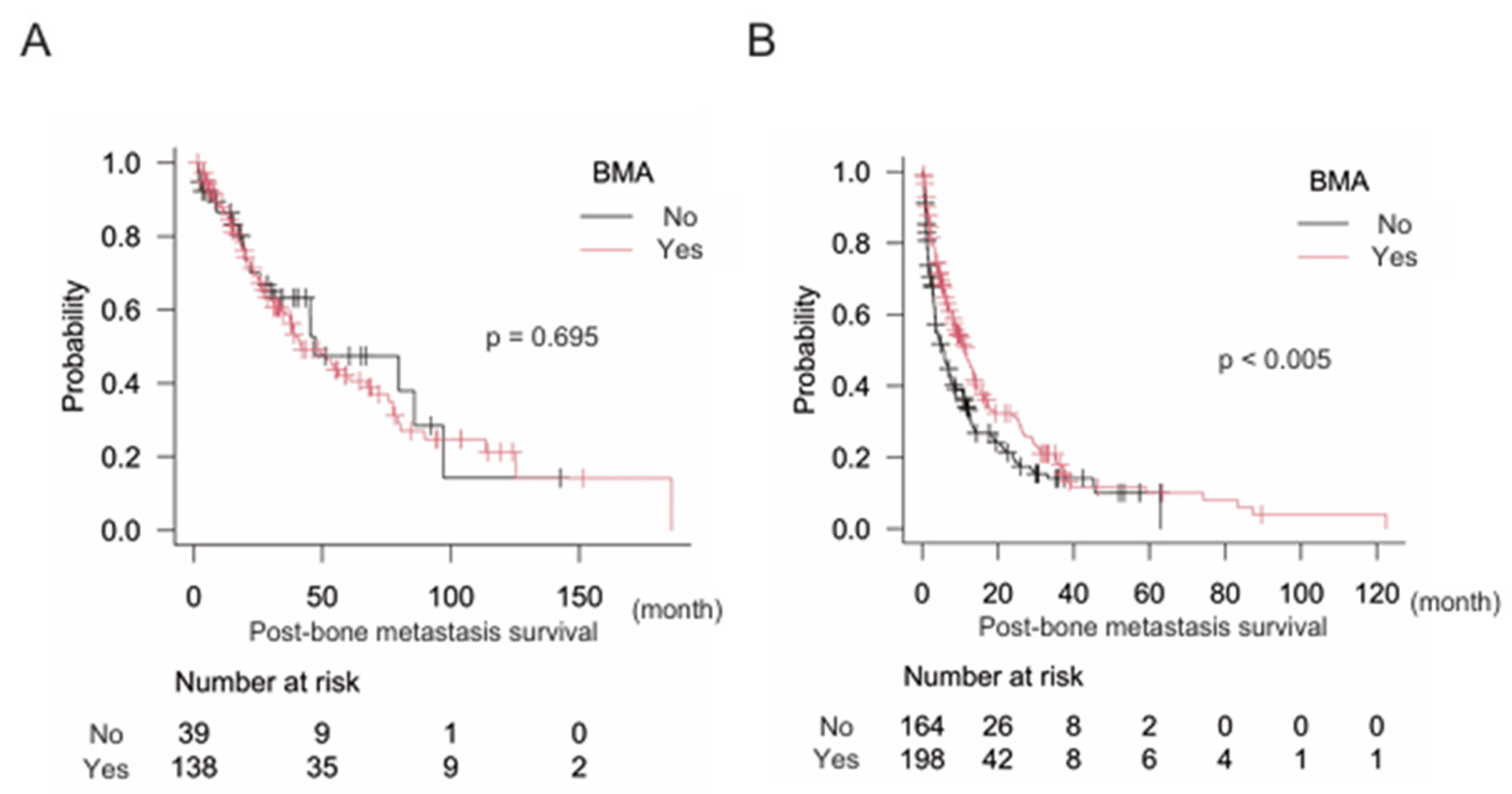

Finally, we attempted to identify the types of cancers in which BMA significantly improved post-bone metastasis survival. Results showed that BMA did not significantly improve post-bone metastasis survival in cancers with a better prognosis than 24 months including breast, kidney, prostate, and thyroid cancers: BMA (-) n = 39, median post-bone metastasis survival 47.2 months (95% CI: 25.7–97.2); BMA (+) n = 138, median post-bone metastasis survival 42.0 months (95% CI: 33.9–67.3) (p = 0.695). But, significantly longer post-bone metastasis survival was observed with BMA treatment in the counterpart (cancers with less than 24 months prognosis for survival): BMA (-) n = 164, median post-bone metastasis survival 5.8 months (95% CI: 3.5–7.4); BMA (+) n = 198, median post-bone metastasis survival 11.7 months (95% CI: 8.3–13.5) (p < 0.005) (

Figure 4A and B).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that treatment with BMA was a positive prognostic factor for post-bone metastasis survival, especially in cancers with a poor prognosis after bone metastasis (which did not include breast, kidney, prostate, and thyroid cancers). Consequently, the results from our study confirmed that BMA was a significant factor for improved post-bone metastasis survival.

An earlier report suggested a positive effect in patients treated with the BMAs docetaxel and zoledronic acid. These treatments provided better bone-metastasis progression-free survival (docetaxel with zoledronic acid 9.0 vs. docetaxel alone; 6.0 months; p < 0.05) and overall survival (OS) (docetaxel with zoledronic acid, 19.0 vs. docetaxel alone; 15.0 months; p < 0.05) than that provided by zoledronic acid alone in castration-resistant prostate cancer [

13], although another paper showed no significant effect [

14]. As recommended in clinical practice, BMA can reduce SRE, which may help maintain or improve performance status. Therefore, BMA is recommended for cancer patients with bone metastasis, although careful consideration should be given to atypical femoral fractures (AFF) and medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). Reports show that the incidence of AFF or MRONJ is less than 1% with BMA treatment [15, 16].

Advancements in cancer treatment, including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, have improved the survival of patients with several types of cancer [

17]. Similarly, post-bone metastasis survival might also improve due to advances in cancer treatment, although previous reports have not yet shown a positive effect, and patients with bone metastasis have demonstrated poor survival [18, 19]. Molecularly-targeted drugs have been associated with prolonged survival in patients with lung cancer and post-bone metastasis [

20]. In line with these findings, the results of our study demonstrate that the presence of EGFR mutations is significantly related to better post-bone metastasis survival. Physicians should be mindful that bone metastasis and primary lung lesions can be controlled by molecularly targeted drugs, leading to improved post-bone metastasis survival.

Some plausible reasons for why we observed longer post-bone metastasis survival with BMA treatment can be proposed. The characteristics of individual cancers including aggressiveness of the tumor, sensitivity to antitumor agents, or radiotherapy may play a role. For example, in most cases, thyroid cancer is slow-growing [

21], suggesting that the expected prognosis of thyroid cancer might be better than that of more aggressive tumors, even after bone metastasis occurs. Additionally, bone formation is occasionally observed with molecularly-targeted drugs in NSCLC with EGFR mutations [

22], indicating that BMA may not be required when bone formation is sufficient without BMA treatment. Most cancers with poor post-bone metastasis survival appear to be less sensitive to antitumor agents or radiotherapy. In contrast, breast and prostate cancers tend to be sensitive to hormone therapy, indicating that BMA treatment may be less effective for post-bone metastasis survival in these cancers, even though BMA is essential for preventing and/or treating SRE [

7].

Independence in activities of daily living (ADL) is crucial for a good QOL and the loss of independence is a global social problem. Physical disabilities have been a focus of research on aging [

23]. In the oncology field, cancer patients have also experienced difficulties with ADL due to physical dysfunction [

24]. A previous study showed that cancer promotes locomotive syndrome, leading to poor QOL [

25]. Consequently, we are facing social issues regarding not only aging but also cancer-related weaknesses. Additionally, the impairment of physical function caused by bone metastasis leads to a decline in performance status, which is strongly related to prognosis. For instance, a previous study reported that bone metastases were a significant independent negative predictive factor for OS in lung cancer patients with mutated and wild-type EGFR, whereas lung or brain metastases were not associated with OS, highlighting the importance of managing bone metastasis [

6].

The present study had some limitations. First, the study may have had a selection bias since all included patients underwent rehabilitation at our institute, indicating that they were less healthy than those who were outpatients and visited the hospital on their own. Furthermore, the number of events was not large in the multivariate analysis; thus, the statistical power may not have been sufficient to reach a solid conclusion. Further investigation is warranted to address these limitations.

5. Conclusions

Treatment with BMA is recommended not only for the prevention and/or treatment of SRE, but also to improve survival, particularly in cancers with typically poor post-bone metastasis survival such as GI cancer and NSCLC without the EGFR mutation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T., K.N.; methodology, H.T.; formal analysis, H.T.; investigation, H.T.; data curation, H.T., Y.K.(Yuji Kato), R.N., Y.K.(Yurika Kosuga-Tsujimoto), S.K.(Shota Kinoshita); writing-original draft preparation, H.T.; writing-review and editing, H.T., R.S., M.W., T.W., S.T. and S.K.(Shigeki Kakunaga); project administration, H.T. ; funding acquisition, H.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Osaka Foundation for the Prevention of Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases (A2023-4).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of Osaka International Cancer Institute (IRB no. 22115-2, 1606279034-4).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate all staff in the Department of Rehabilitation at Osaka International Cancer Institute for the discussion regarding this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huang JF, Shen J, Li X, Rengan R, Silvestris N, Wang M, et al. Incidence of patients with bone metastases at diagnosis of solid tumors in adults: a large population-based study. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(7):482–482. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez RK, Wade SW, Reich A, Pirolli M, Liede A, Lyman GH. Incidence of bone metastases in patients with solid tumors: Analysis of oncology electronic medical records in the United States. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1–11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nørgaard M, Jensen AØ, Jacobsen JB, Cetin K, Fryzek JP, Sørensen HT. Skeletal Related Events, Bone Metastasis and Survival of Prostate Cancer: A Population Based Cohort Study in Denmark (1999 to 2007). J Urol. 2010;184(1):162–7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathiakumar N, Delzell E, Morrisey MA, Falkson C, Yong M, Chia V, et al. Mortality following bone metastasis and skeletal-related events among men with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis of US Medicare beneficiaries, 1999–2006. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011;14(2):177–83. [CrossRef]

- Yong M, Jensen AØ, Jacobsen JB, Nørgaard M, Fryzek JP, Sørensen HT. Survival in breast cancer patients with bone metastases and skeletal-related events: A population-based cohort study in Denmark (1999-2007). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129(2):495–503. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto D, Ueda H, Shimizu R, Kato R, Otoshi T, Kawamura T, et al. Features and prognostic impact of distant metastasis in patients with stage IV lung adenocarcinoma harboring EGFR mutations: importance of bone metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2014;31(5):543–51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardley A, Davidson N, Barrett-Lee P, Hong A, Mansi J, Dodwell D, et al. Zoledronic acid significantly improves pain scores and quality of life in breast cancer patients with bone metastases: A randomised, crossover study of community vs hospital bisphosphonate administration. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(10):1869–76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen C, Li R, Yang T, Ma L, Zhou S, Li M, et al. Denosumab Versus Zoledronic Acid in the Prevention of Skeletal-related Events in Vulnerable Cancer Patients: A Meta-analysis of Randomized, Controlled Trials. Clin Ther. 2020;42(8):1494-1507.e1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohno N, Aogi K, Minami H, Nakamura S, Asaga T, Iino Y, et al. Zoledronic acid significantly reduces skeletal complications compared with placebo in Japanese women with bone metastases from breast cancer: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3314–21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Carrigan B, Wong MHF, Willson ML, Stockler MR, Pavlakis N, Goodwin A. Bisphosphonates and other bone agents for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2017(10). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stopeck AT, Lipton A, Body JJ, Steger GG, Tonkin K, De Boer RH, et al. Denosumab compared with zoledronic acid for the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced breast cancer: A randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(35):5132–9. [CrossRef]

- Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(3):452–8.

- Pan Y, Jin H, Chen W, Yu Z, Ye T, Zheng Y, et al. Docetaxel with or without zoledronic acid for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46(12):2319–26. [CrossRef]

- Qin A, Zhao S, Miah A, Wei L, Patel S, Johns A, et al. Bone Metastases, Skeletal-Related Events, and Survival in Patients With Metastatic Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2021;19(8):915–21.

- Scagliotti GV, Hirsh V, Siena S, Henry DH, Woll PJ, Manegold C, et al. Overall Survival Improvement in Patients with Lung Cancer and Bone Metastases Treated with Denosumab Versus Zoledronic Acid: Subgroup Analysis from a Randomized Phase 3 Study. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(12):1823–9. [CrossRef]

- Kaku T, Oh Y, Sato S, Koyanagi H, Hirai T, Yuasa M, et al. Incidence of atypical femoral fractures in the treatment of bone metastasis: An alert report. J Bone Oncol. 2020;23(April):100301. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold M, Rutherford MJ, Bardot A, Ferlay J, Andersson TML, Myklebust TÅ, et al. Progress in cancer survival, mortality, and incidence in seven high-income countries 1995–2014 (ICBP SURVMARK-2): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(11):1493–505.

- Hong S, Youk T, Lee SJ, Kim KM, Vajdic CM. Bone metastasis and skeletal-related events in patients with solid cancer: A Korean nationwide health insurance database study. Hsieh JCH, editor. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0234927. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson E, Christiansen CF, Ulrichsen SP, Rørth MR, Sørensen HT. Survival after bone metastasis by primary cancer type: a Danish population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016022. [CrossRef]

- Sugiura H, Yamada K, Sugiura T, Hida T, Mitsudomi T. Predictors of Survival in Patients With Bone Metastasis of Lung Cancer. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(3):729–36. [CrossRef]

- Bulfamante AM, Lori E, Bellini MI, Bolis E, Lozza P, Castellani L, et al. Advanced Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: A Complex Condition Needing a Tailored Approach. Front Oncol. 2022;12(July):1–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanaoka K, Sumikawa H, Oyamada S, Tamiya A, Inagaki Y, Taniguchi Y, et al. Osteoblastic bone reaction in non-small cell lung cancer harboring epidermal growth factor receptor mutation treated with osimertinib. BMC Cancer. 2023;23(1):1–9. [CrossRef]

- Dunlop DD, Hughes SL, Manheim LM. Disability in activities of daily living: patterns of change and a hierarchy of disability. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(3):378–83. [CrossRef]

- Neo J, Fettes L, Gao W, Higginson IJ, Maddocks M. Disability in activities of daily living among adults with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;61:94–106. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirahata M, Imanishi J, Fujinuma W, Abe S, Inui T, Ogata N, et al. Cancer may accelerate locomotive syndrome and deteriorate quality of life: a single-centre cross-sectional study of locomotive syndrome in cancer patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2023;28(4):603–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).