Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

30 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

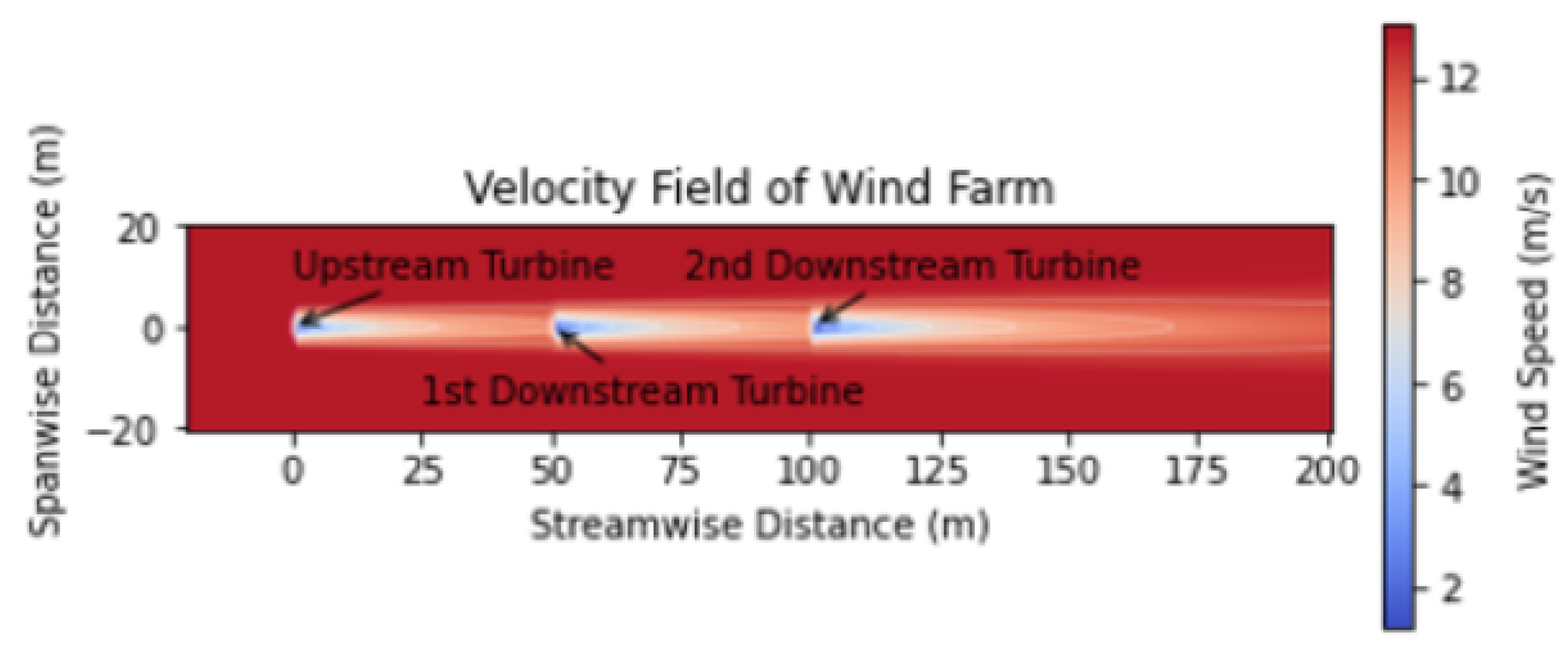

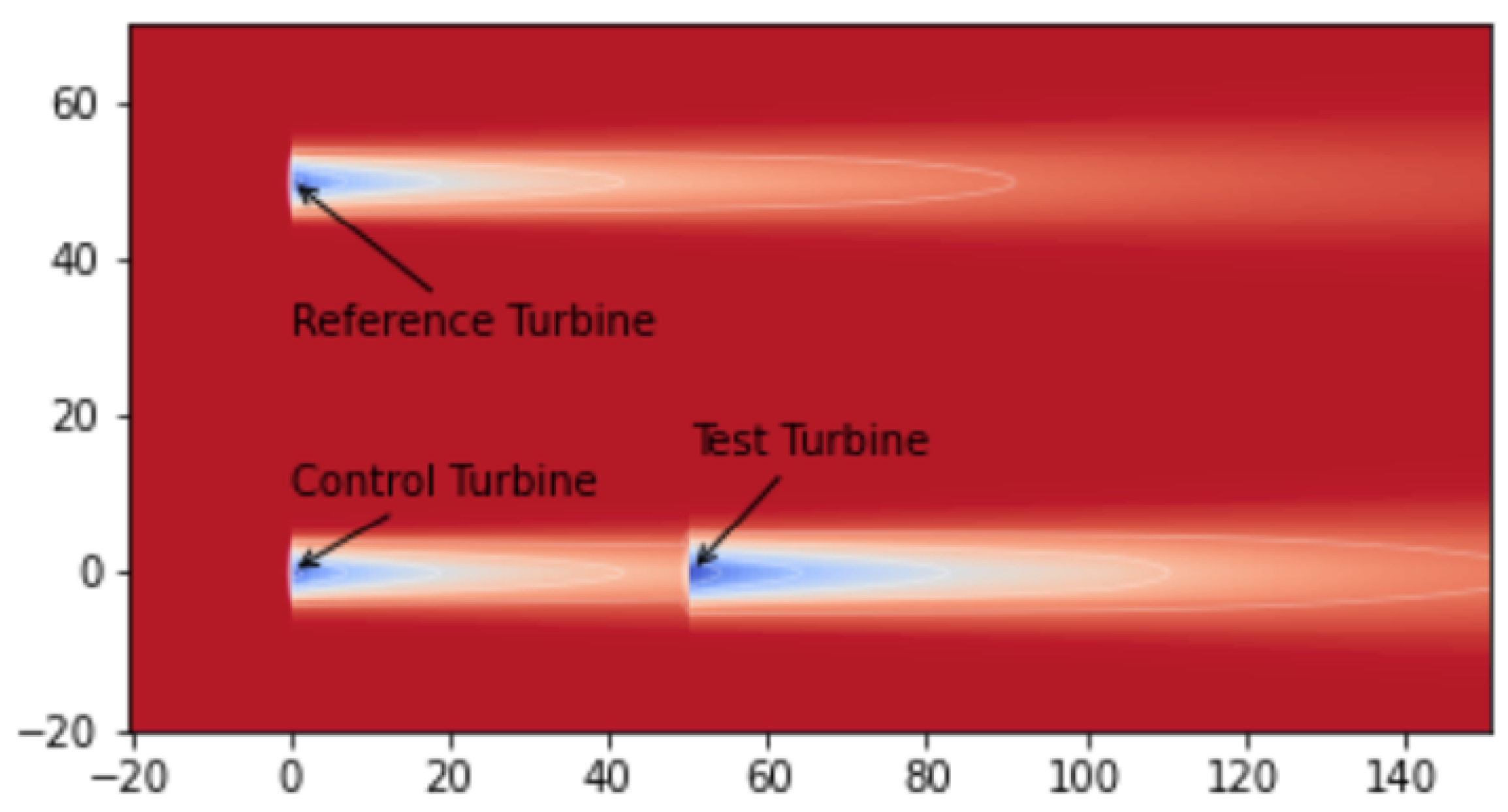

2. Wake Aerodynamics

3. Wake Models

3.1. Jensen Model

3.2. Multi-Zone Model

3.3. Jimenez Model

3.4. Bastankhah and Porté-Agel Model

3.5. Gaussian Model

3.6. Curl Model

3.7. Gauss-Curl Hybrid Model

3.8. Larsen Model

3.9. Wake Combination Models

3.10. Added Turbulence Models

3.10.1. Gaussian Model

3.10.2. Crespo Hernandez Model

4. Modeling Tools

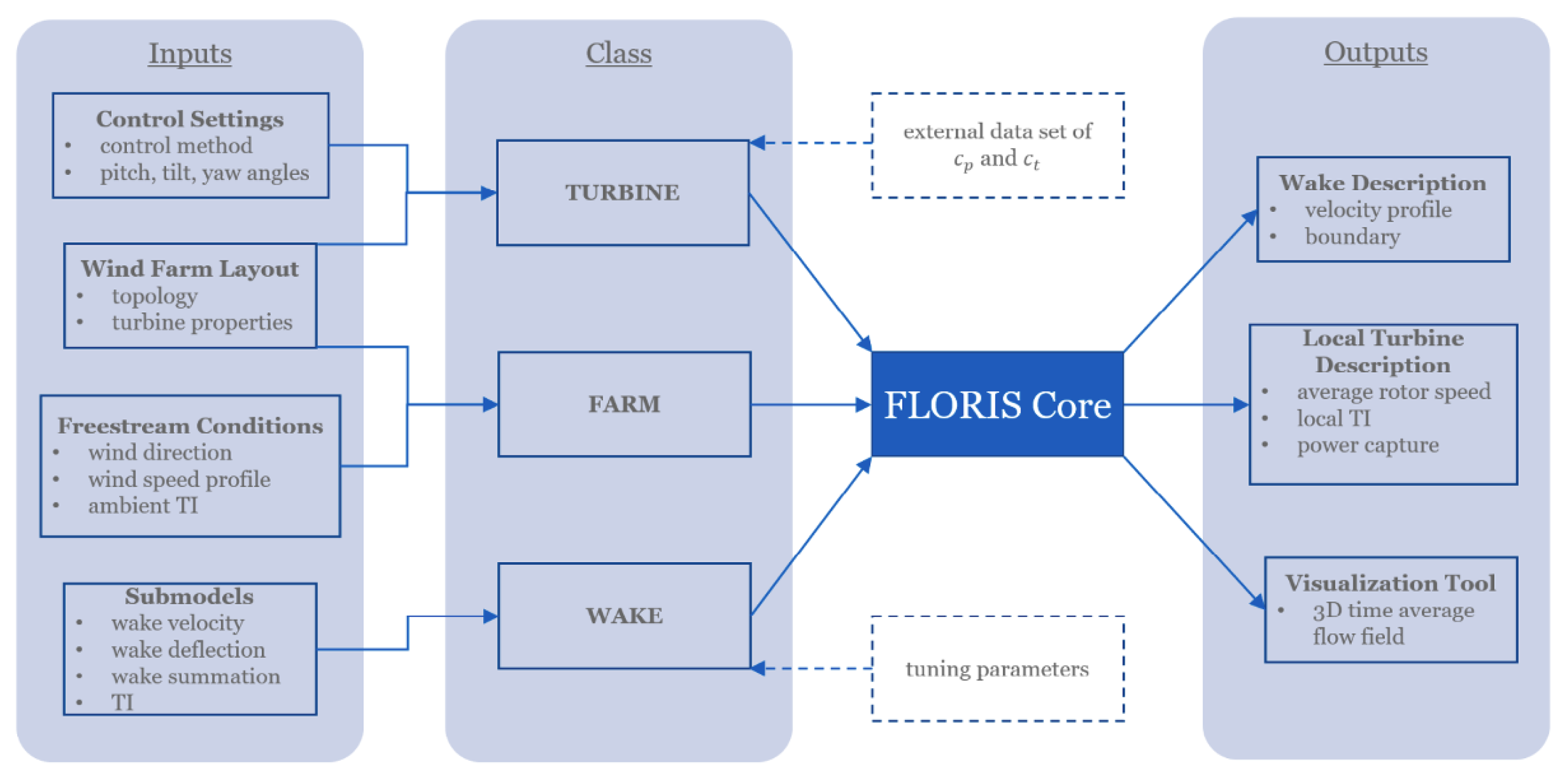

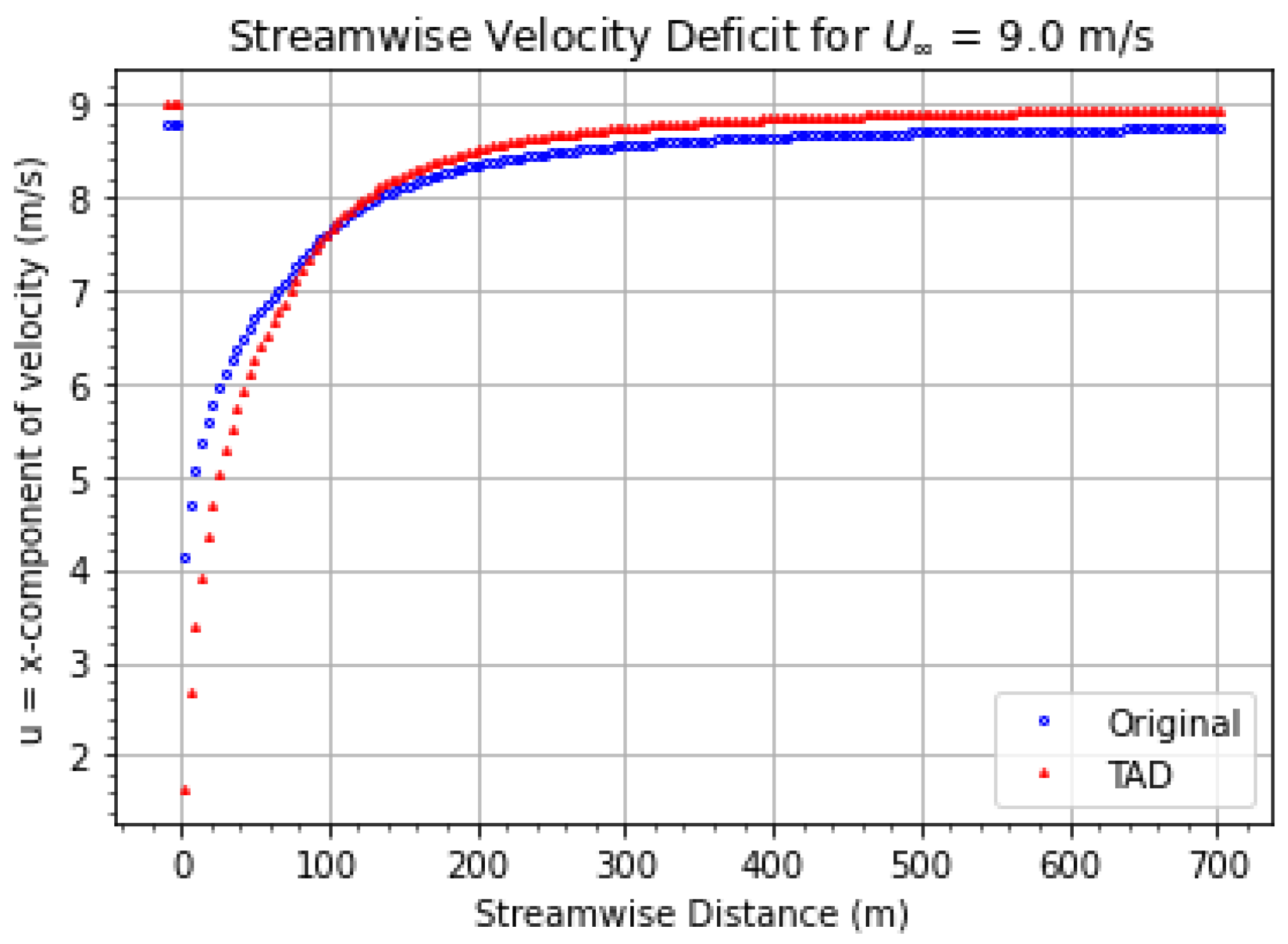

4.1. FLORIS

4.2. FLORISSE

4.3. OpenFAST

4.4. SOFWA

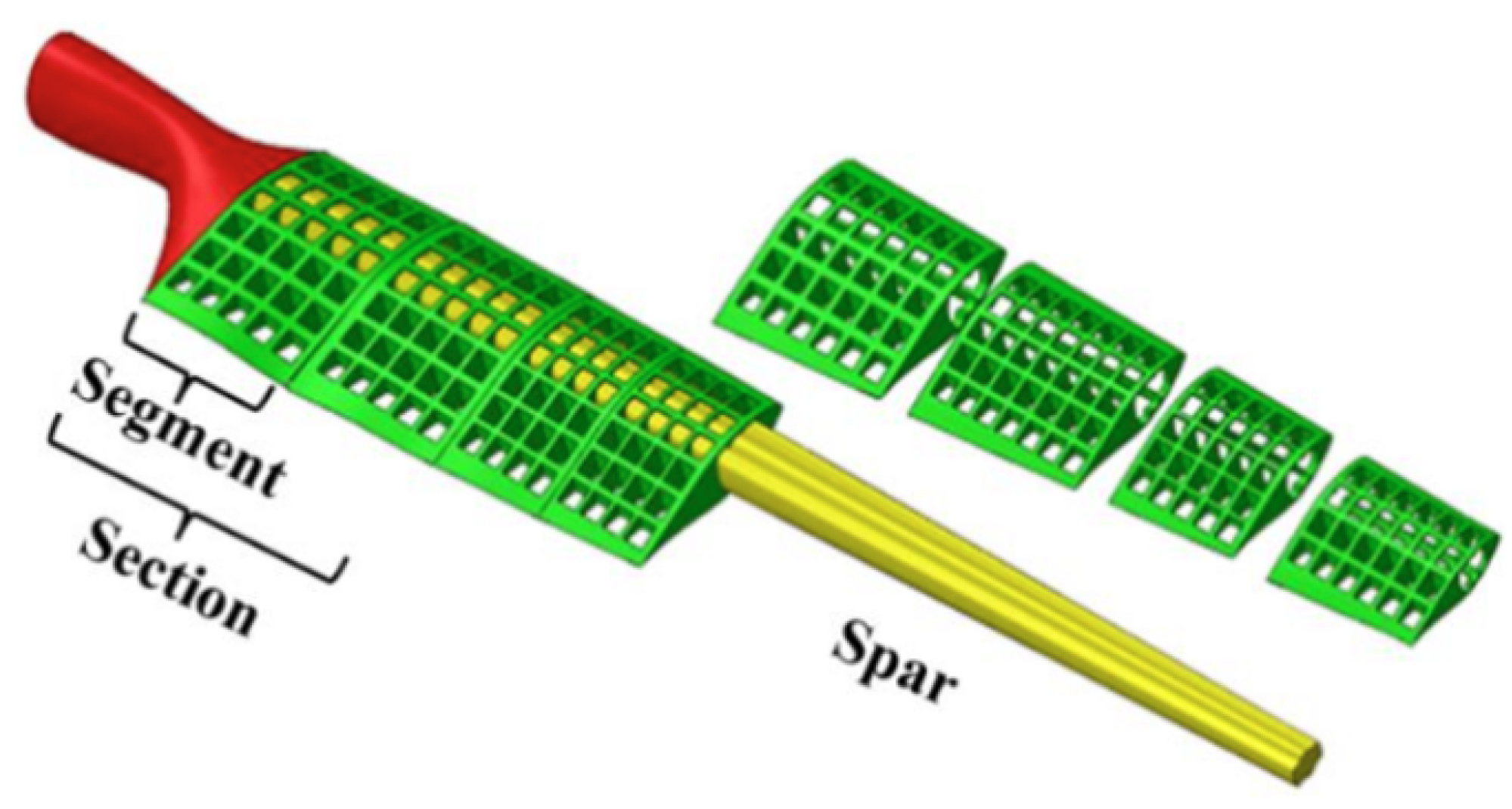

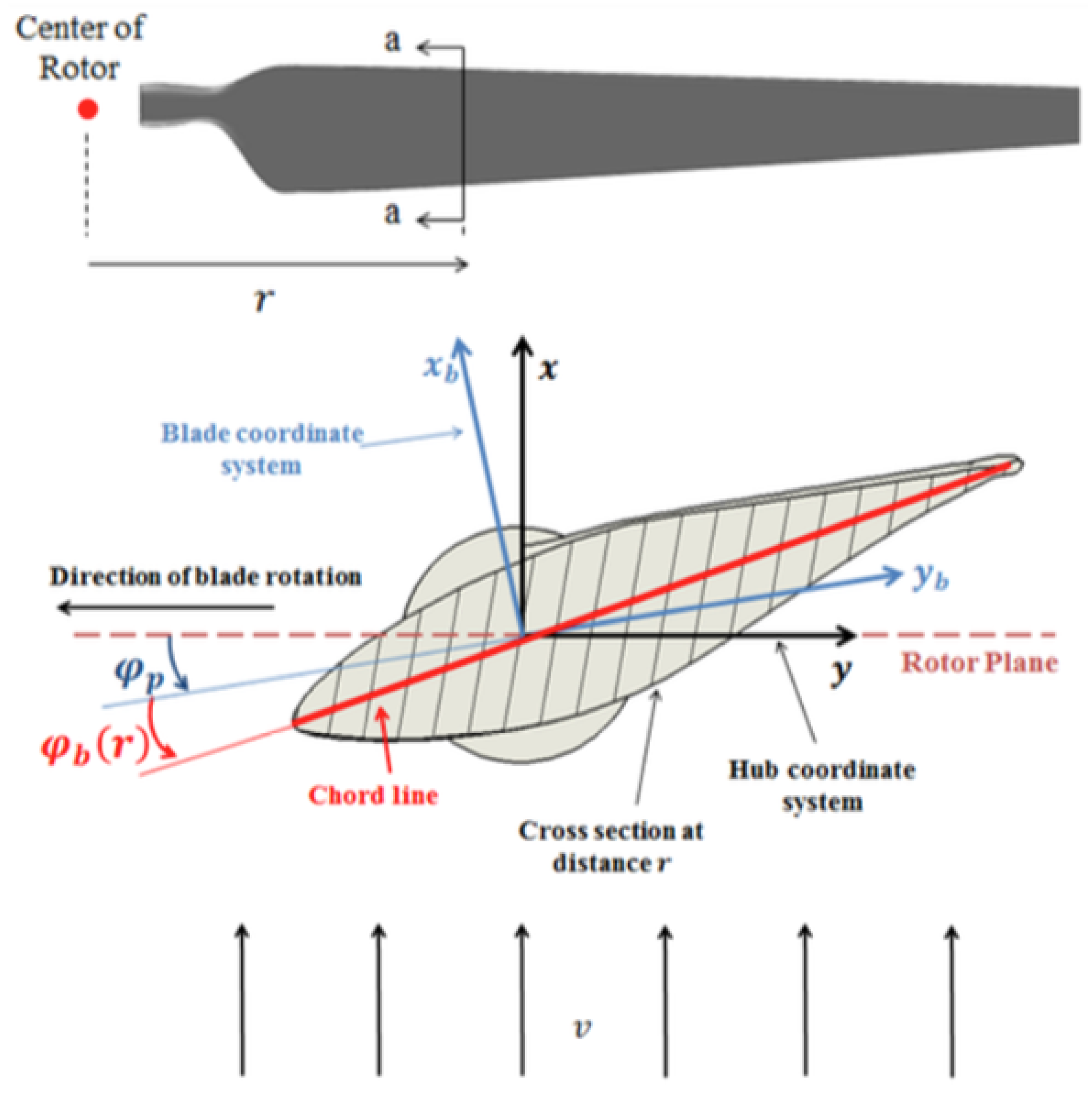

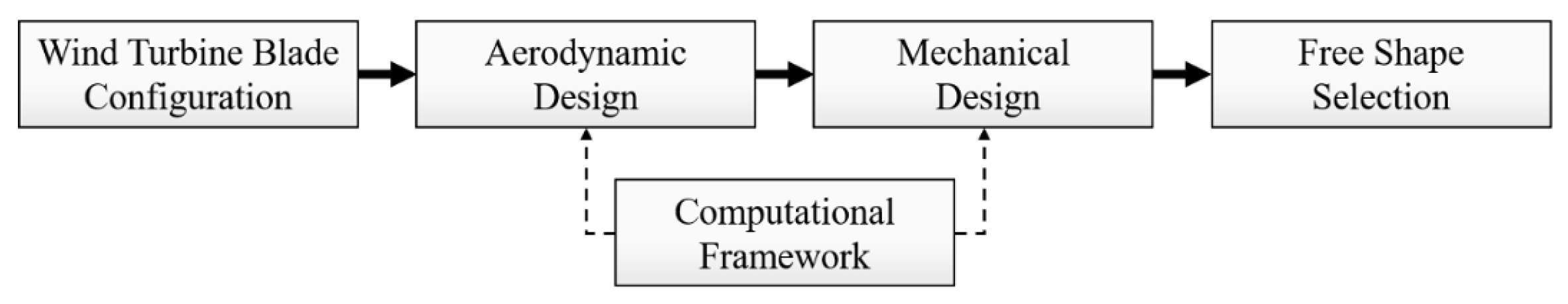

5. Flexible Blade Concept

6. Results and Discussion

| Rating | 20 kW |

| Rotor Orientation, Configuration | Upwind, 2 Blades |

| Blade Airfoils | S809 |

| Control | Fixed-Speed |

| Rotational Speed | 72 rpm synchronous speed |

| Cut-in, Rated, Cut-out Wind Speed [m/s] | 3.0, 13.5, 25.0 |

| Rotor, Hub Diameter [m] | 4.6, 0.429 |

| Hub Height [m] | 12.192 |

| Blade Pitch [°] | 2-14 |

| Tilt, Yaw Angle [°] | 0.0 |

| [m/s] | Original | TAD #1 | TAD #2 | TAD #3 | TAD #4 | TAD #5 | TAD #6 | TAD #7 | TAD #8 | TAD #9 | ||||||||||

| 5 | 0.447 | 0.817 | 0.464 | 0.851 | 0.460 | 0.841 | 0.458 | 0.833 | 0.451 | 0.829 | 0.447 | 0.822 | 0.442 | 0.816 | 0.435 | 0.803 | 0.424 | 0.787 | 0.423 | 0.786 |

| 6 | 0.484 | 0.793 | 0.486 | 0.814 | 0.489 | 0.811 | 0.487 | 0.803 | 0.482 | 0.798 | 0.483 | 0.795 | 0.481 | 0.789 | 0.478 | 0.777 | 0.471 | 0.770 | 0.470 | 0.765 |

| 7 | 0.435 | 0.617 | 0.432 | 0.627 | 0.437 | 0.627 | 0.440 | 0.626 | 0.436 | 0.624 | 0.434 | 0.622 | 0.433 | 0.617 | 0.431 | 0.609 | 0.427 | 0.601 | 0.427 | 0.599 |

| 8 | 0.370 | 0.490 | 0.361 | 0.496 | 0.368 | 0.494 | 0.371 | 0.494 | 0.377 | 0.512 | 0.371 | 0.494 | 0.370 | 0.491 | 0.369 | 0.486 | 0.366 | 0.482 | 0.365 | 0.479 |

| 9 | 0.314 | 0.401 | 0.300 | 0.409 | 0.303 | 0.403 | 0.312 | 0.402 | 0.314 | 0.405 | 0.315 | 0.407 | 0.315 | 0.403 | 0.314 | 0.397 | 0.312 | 0.395 | 0.312 | 0.393 |

| 10 | 0.268 | 0.336 | 0.253 | 0.342 | 0.258 | 0.339 | 0.261 | 0.332 | 0.267 | 0.336 | 0.268 | 0.338 | 0.270 | 0.338 | 0.269 | 0.334 | 0.268 | 0.331 | 0.268 | 0.330 |

| 11 | 0.231 | 0.286 | 0.216 | 0.291 | 0.221 | 0.292 | 0.220 | 0.279 | 0.228 | 0.284 | 0.229 | 0.289 | 0.231 | 0.286 | 0.233 | 0.286 | 0.233 | 0.284 | 0.232 | 0.282 |

| 12 | 0.200 | 0.245 | 0.187 | 0.255 | 0.193 | 0.253 | 0.188 | 0.248 | 0.196 | 0.240 | 0.199 | 0.248 | 0.200 | 0.248 | 0.203 | 0.246 | 0.204 | 0.247 | 0.204 | 0.246 |

| 13 | 0.174 | 0.212 | 0.164 | 0.223 | 0.170 | 0.222 | 0.165 | 0.216 | 0.169 | 0.208 | 0.173 | 0.216 | 0.175 | 0.216 | 0.178 | 0.215 | 0.180 | 0.216 | 0.180 | 0.215 |

| [m/s] | TAD #1 | TAD #2 | TAD #3 | TAD #4 | TAD #5 | TAD #6 | TAD #7 | TAD #8 | TAD #9 | |||||||||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| 5 | 3.83 | 4.11 | 3.09 | 2.85 | 2.53 | 2.48 | 1.05 | 1.38 | 0.00 | 0.50 | -1.01 | -0.17 | -2.53 | -1.81 | -4.99 | -3.78 | -5.26 | -3.82 |

| 6 | 0.35 | 2.70 | 1.05 | 2.33 | 0.60 | 1.27 | -0.37 | 0.64 | -0.19 | 0.34 | -0.68 | -0.40 | -1.24 | -1.91 | -2.58 | -2.83 | -2.89 | -3.52 |

| 7 | -0.53 | 1.59 | 0.64 | 1.62 | 1.13 | 1.36 | 0.21 | 1.04 | -0.18 | 0.70 | -0.41 | -0.02 | -0.81 | -1.38 | -1.75 | -2.64 | -1.86 | -2.95 |

| 8 | -2.62 | 1.20 | -0.62 | 0.92 | 0.24 | 0.90 | 1.76 | 4.45 | 0.08 | 0.73 | 0.00 | 0.29 | -0.46 | -0.90 | -1.24 | -1.67 | -1.40 | -2.22 |

| 9 | -4.52 | 1.89 | -3.63 | 0.35 | -0.76 | 0.27 | -0.22 | 0.82 | 0.13 | 1.30 | 0.03 | 0.45 | -0.10 | -1.00 | -0.64 | -1.47 | -0.86 | -1.97 |

| 10 | -5.71 | 1.90 | -3.92 | 0.92 | -2.46 | -1.10 | -0.52 | 0.12 | -0.04 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.37 | -0.57 | 0.11 | -1.58 | -0.07 | -1.90 |

| 11 | -6.29 | 1.96 | -4.29 | 2.31 | -4.85 | -2.21 | -1.08 | -0.46 | -0.74 | 1.16 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 1.08 | 0.11 | 0.87 | -0.39 | 0.69 | -1.09 |

| 12 | -6.44 | 4.04 | -3.50 | 3.35 | -5.89 | -1.02 | -2.30 | -1.96 | -0.70 | 1.10 | -0.35 | 1.14 | 1.40 | 0.37 | 1.90 | 0.69 | 1.70 | 0.29 |

| 13 | -5.68 | 4.99 | -2.53 | 4.76 | -5.45 | 1.93 | -3.21 | -2.26 | -0.46 | 1.60 | 0.34 | 1.74 | 1.95 | 1.22 | 3.04 | 1.79 | 3.27 | 1.46 |

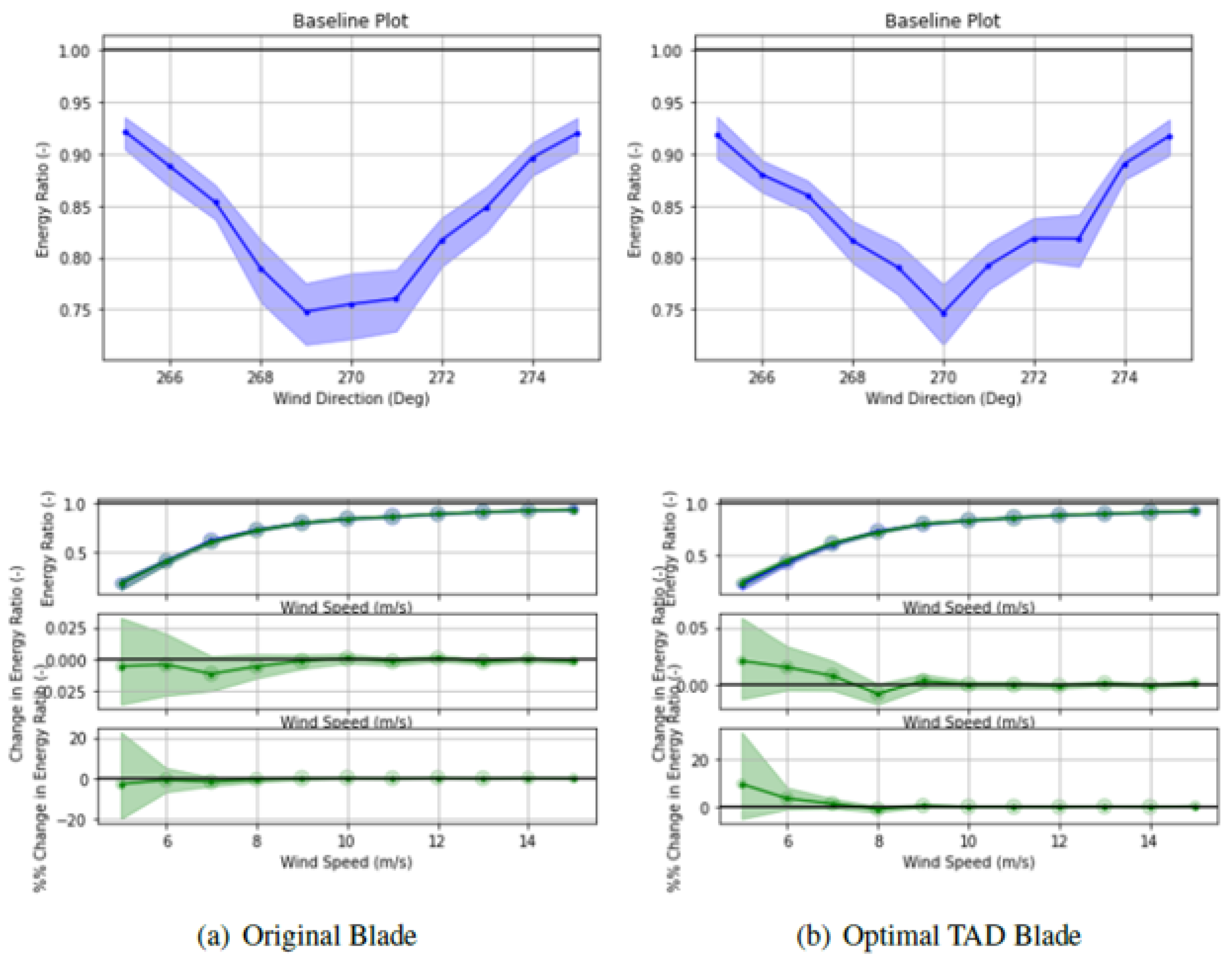

6.1. Optimal Blade Design

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEP | Annual Energy Production |

| AIF | Axial Induction Factor |

| BEM | Blade ELement Momentum |

| NSE | Navier-Stokes Equation |

| Re | Reynolds Number |

| TAD | Twist Angle Distribution |

| TI | Turbulence Intensity |

| TSR | Tip Speed Ratio |

| UAE | Unsteady Aerodynamics Experiment |

References

- Administration, U.E.I.; Department, E. April 2021 Monthly Energy Review; Government Printing Office, 2021.

- Author, N.G. 2018 Wind Technologies Market Report; 2019. [CrossRef]

- Wind, I. Long-term research and development needs for wind energy for the time frame 2012 to 2030. International Energy Agency Wind, Paris, France 2013.

- Hall, J.F.; Mecklenborg, C.A.; Chen, D.; Pratap, S.B. Wind energy conversion with a variable-ratio gearbox: design and analysis. Renewable Energy 2011, 36, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, T.; Jenkins, N.; Sharpe, D.; Bossanyi, E. Wind Energy Handbook (John Wiley & Sons, Chicester, United Kingdom) 2011.

- Manwell, J.F.; McGowan, J.G.; Rogers, A.L. Wind energy explained: theory, design and application; John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

- Sadeghilari, K. Aerodynamic Analysis of Wake Interaction and Load Mitigation for a Wind Turbine with Active Blade Morphing Control. Master’s thesis, State University of New York at Buffalo, 2022.

- Lundquist, J.; DuVivier, K.; Kaffine, D.; Tomaszewski, J. Costs and consequences of wind turbine wake effects arising from uncoordinated wind energy development. Nature Energy 2019, 4, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Longatt, F.; Wall, P.; Terzija, V. Wake effect in wind farm performance: Steady-state and dynamic behavior. Renewable Energy 2012, 39, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, A. Effects of Wake Interaction on Downstream Wind Turbines. Wind Engineering 2014, 38, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, B.; Guala, M.; Lei, L.; Zeng, P. Experimental investigation of the performance and wake effect of a small-scale wind turbine in a wind tunnel. Energy 2019, 166, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilip, D.; Porté-Agel, F. Wind turbine wake mitigation through blade pitch offset. Energies 2017, 10, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.; Gebraad, P.M.; Lee, S.; van Wingerden, J.W.; Johnson, K.; Churchfield, M.; Michalakes, J.; Spalart, P.; Moriarty, P. Simulation comparison of wake mitigation control strategies for a two-turbine case. Wind Energy 2015, 18, 2135–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.; Fleming, P.; King, R.; Martínez-Tossas, L.A.; Bay, C.J.; Mudafort, R.; Simley, E. Controls-oriented model for secondary effects of wake steering. Wind Energy Science Discussions 2020, pp. 1–22.

- MacPhee, D.W.; Beyene, A. Experimental and fluid structure interaction analysis of a morphing wind turbine rotor. Energy 2015, 90, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Caro, S.; Bennis, F.; Salinas Mejia, O.R. A simplified morphing blade for horizontal axis wind turbines. Journal of solar energy engineering 2014, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarino, S.; Bilgen, O.; Ajaj, R.M.; Friswell, M.I.; Inman, D.J. A review of morphing aircraft. Journal of intelligent material systems and structures 2011, 22, 823–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisshaar, T.A. Morphing aircraft systems: historical perspectives and future challenges. Journal of aircraft 2013, 50, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponta, F.L.; Otero, A.D.; Rajan, A.; Lago, L.I. The adaptive-blade concept in wind-power applications. Energy for Sustainable Development 2014, 22, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauleder, J.; van der Wall, B.G.; Abdelmoula, A.; Komp, D.; Kumar, S.; Ondra, V.; Titurus, B.; Woods, B.K. Aerodynamic performance of morphing blades and rotor systems. In Proceedings of the AHS International 74th Annual Forum & Technology Display, 2018, p. 1.

- Sofla, A.; Meguid, S.; Tan, K.; Yeo, W. Shape morphing of aircraft wing: Status and challenges. Materials & Design 2010, 31, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattalli, V.L.; Srivatsa, S.R. Wing Morphing to Improve Control Performance of an Aircraft-An Overview and a Case Study. Materials Today: Proceedings 2018, 5, 21442–21451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, A.; Hassanabad, A.H.; Dadvand, A. Aerodynamic shape optimization and analysis of small wind turbine blades employing the Viterna approach for post-stall region. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2016, 55, 2035–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loth, E.; Selig, M.; Moriarty, P. Morphing segmented wind turbine concept. In Proceedings of the 28th AIAA Applied Aerodynamics Conference, 2010, p. 4400.

- Gili, P.; Frulla, G. A variable twist blade concept for more effective wind generation: design and realization. Smart Science 2016, 4, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daynes, S.; Weaver, P. Design and testing of a deformable wind turbine blade control surface. Smart Materials and Structures 2012, 21, 105019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakpour Nejadkhaki, H.; Hall, J.F. A Design Methodology for a Flexible Wind Turbine Blade With an Actively Variable Twist Distribution to Increase Region 2 Efficiency. In Proceedings of the International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2017, Vol. 58127, p. V02AT03A025.

- Nejadkhaki, H.K.; Hall, J.F. Modeling and Design Method for an Adaptive Wind Turbine Blade With Out-of-Plane Twist. Journal of Solar Energy Engineering 2018, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejadkhaki, H.K.; Hall, J.F. Integrative Control and Design Framework for an Actively Variable Twist Wind Turbine Blade to Increase Efficiency. In Proceedings of the International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2018, Vol. 51753, p. V02AT03A004.

- Khakpour Nejadkhaki, H.; Hall, J.F. Control Framework and Integrative Design Method for an Adaptive Wind Turbine Blade. Journal of Dynamic Systems, Measurement, and Control 2020, 142, 101001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, R.D. Applied fluid dynamics handbook. vnr 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Cardell, G.S. Flow past a circular cylinder with a permeable wake splitter plate. PhD thesis, California Institute of Technology, 1993.

- Panton, R.L. Incompressible flow; John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

- Sanderse, B. Aerodynamics of wind turbine wakes Literature review 2009.

- Felli, M.; Falchi, M. Propeller wake evolution mechanisms in oblique flow conditions. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2018, 845, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, L.; Sørensen, J.N.; Crespo, A. Wind turbine wake aerodynamics. Progress in aerospace sciences 2003, 39, 467–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbay, A. Experimental investigations on the wake interferences of multiple wind turbines 2012.

- Porté-Agel, F.; Bastankhah, M.; Shamsoddin, S. Wind-turbine and wind-farm flows: a review. Boundary-Layer Meteorology 2020, 174, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NREL. FLORIS Wake Modeling Utility - FLORIS 2.2.0 Documentation, 2020.

- Ramírex Castillo, S.A. Engineering models enhancement for wind farm wake simulation and optimization 2019.

- Raach, S.; Campagnolo, F.; Ramamurthy, B.K.; Kern, S.; Boersma, S.; Doekemeijer, B.; van Wingerden, J.W.; Knudsen, T.; Kanev, S.; Aparicio-Sanchez, M.; et al. Classification of control-oriented models for wind farm control applications, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, N.O. A note on wind generator interaction 1983.

- Bay, C.; King, J.; Fleming, P.; Martínez-Tossas, L.; Mudafort, R.; Simley, E.; Lawson, M. FLORIS: A Brief Tutorial, 2019.

- Annoni, J.; Fleming, P.; Scholbrock, A.K.; Roadman, J.M.; Dana, S.; Adcock, C.; Porte-Agel, F.; Raach, S.; Haizmann, F.; Schlipf, D. Analysis of control-oriented wake modeling tools using lidar field results. Wind Energy Science (Online) 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebraad, P.M.; Teeuwisse, F.; van Wingerden, J.W.; Fleming, P.A.; Ruben, S.D.; Marden, J.R.; Pao, L.Y. A data-driven model for wind plant power optimization by yaw control. In Proceedings of the 2014 American Control Conference. IEEE, 2014, pp. 3128–3134.

- Jiménez, Á.; Crespo, A.; Migoya, E. Application of a LES technique to characterize the wake deflection of a wind turbine in yaw. Wind energy 2010, 13, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastankhah, M.; Porté-Agel, F. Experimental and theoretical study of wind turbine wakes in yawed conditions. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2016, 806, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.; King, J.; Bay, C.J.; Simley, E.; Mudafort, R.; Hamilton, N.; Farrell, A.; Martinez-Tossas, L. Overview of FLORIS updates. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, 2020, Vol. 1618, p. 022028.

- Martínez-Tossas, L.A.; Annoni, J.; Fleming, P.A.; Churchfield, M.J. The aerodynamics of the curled wake: A simplified model in view of flow control. Wind Energy Science (Online) 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neiva, A.; Guedes, V.; Massa, C.; de Freitas, D. A review of wind turbine wake models for microscale wind park simulation. ABCM International Congress of Mechanical Engineering, 2019.

- Niayifar, A.; Porté-Agel, F. A new analytical model for wind farm power prediction. In Proceedings of the Journal of physics: conference series. IOP Publishing, 2015, Vol. 625, p. 012039. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A.; King, J.; Draxl, C.; Mudafort, R.; Hamilton, N.; Bay, C.J.; Fleming, P.; Simley, E. Design and analysis of a spatially heterogeneous wake. Wind Energy Science Discussions 2020, pp. 1–25.

- Niayifar, A.; Porté-Agel, F. Analytical modeling of wind farms: A new approach for power prediction. Energies 2016, 9, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, A.; Herna, J.; et al. Turbulence characteristics in wind-turbine wakes. Journal of wind engineering and industrial aerodynamics 1996, 61, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doekemeijer, B.; Bossanyi, E.; Kanev, S.; Bot, E.; Elorza, I.; Campagnolo, F.; Fortes-Plaza, A.; Schreiber, J.; Eguinoa-Erdozain, I.; Gomez-Iradi, S.; et al. Description of the reference and the control-oriented wind farm models, 2018. [CrossRef]

- NREL. FLORIS. Version 2.2.0, 2020.

- Doekemeijer, B.; Storm, R.; Schreiber, J.; daanvanderhoek. TUDelft-DataDrivenControl/FLORISSE_M: Stable version from 2018-2019, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gebraad, P.; Thomas, J.J.; Ning, A.; Fleming, P.; Dykes, K. Maximization of the annual energy production of wind power plants by optimization of layout and yaw-based wake control. Wind Energy 2017, 20, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, A.; Muscari, C.; Schito, P.; Zasso, A. A Steady-State Wind Farm Wake Model Implemented in OpenFAST. Energies 2020, 13, 6158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.J.; Gebraad, P.M.; Ning, A. Improving the FLORIS wind plant model for compatibility with gradient-based optimization. Wind Engineering 2017, 41, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TU Delft DCSC Data Driven Control Group Revision. FLORISSE M Documentation, 2019.

- NREL. OpenFAST Documentation Release v2.5.0, 2021.

- Churchfield, M.; Lee, S.; Moriarty, P. Overview of the simulator for wind farm application (SOWFA). National Renewable Energy Laboratory 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Drela, M.; Youngren, H. XFOIL 6.94 user guide, 2001.

- Marten, D.; Wendler, J. Qblade guidelines. Ver. 0.6, Technical University of (TU Berlin), Berlin, Germany 2013.

- Hand, M.; Simms, D.; Fingersh, L.; Jager, D.; Cotrell, J.; Schreck, S.; Larwood, S. Unsteady aerodynamics experiment phase VI: wind tunnel test configurations and available data campaigns. Technical report, National Renewable Energy Lab., Golden, CO.(US), 2001.

- Moriarty, P.J.; Hansen, A.C. AeroDyn theory manual. Technical report, National Renewable Energy Lab., Golden, CO (US), 2005.

- Hansen, M. Aerodynamics of wind turbines; Routledge, 2015.

- Fleming, P.; King, J.; Dykes, K.; Simley, E.; Roadman, J.; Scholbrock, A.; Murphy, P.; Lundquist, J.K.; Moriarty, P.; Fleming, K.; et al. Initial results from a field campaign of wake steering applied at a commercial wind farm–Part 1. Wind Energy Science 2019, 4, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.; King, J.; Simley, E.; Roadman, J.; Scholbrock, A.; Murphy, P.; Lundquist, J.K.; Moriarty, P.; Fleming, K.; Dam, J.v.; et al. Continued results from a field campaign of wake steering applied at a commercial wind farm–Part 2. Wind Energy Science 2020, 5, 945–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| [m/s] | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| Original | 1994 | 1971 | 1888 | 1804 | 1735 | 1676 | 1626 | 1575 | 1527 |

| TAD #1 | 1994 | 1997 | 1903 | 1814 | 1751 | 1692 | 1634 | 1599 | 1558 |

| TAD #2 | 1994 | 1993 | 1903 | 1812 | 1738 | 1684 | 1637 | 1594 | 1556 |

| TAD #3 | 1994 | 1983 | 1901 | 1812 | 1737 | 1667 | 1601 | 1576 | 1535 |

| TAD #4 | 1994 | 1977 | 1898 | 1843 | 1742 | 1677 | 1615 | 1553 | 1503 |

| TAD #5 | 1994 | 1974 | 1895 | 1810 | 1746 | 1682 | 1628 | 1577 | 1532 |

| TAD #6 | 1994 | 1967 | 1888 | 1806 | 1739 | 1681 | 1621 | 1577 | 1533 |

| TAD #7 | 1994 | 1952 | 1875 | 1795 | 1726 | 1671 | 1619 | 1571 | 1529 |

| TAD #8 | 1994 | 1943 | 1863 | 1788 | 1722 | 1663 | 1615 | 1573 | 1534 |

| TAD #9 | 1994 | 1936 | 1860 | 1783 | 1718 | 1660 | 1610 | 1570 | 1531 |

| [m/s] | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| TAD #7 | 0.00% | -0.96% | -0.69% | -0.50% | -0.52% | -0.30% | -0.43% | -0.25% | 0.13% |

| TAD #8 | 0.00% | -1.42% | -1.32% | -0.89% | -0.75% | -0.78% | -0.68% | -0.13% | 0.46% |

| TAD #9 | 0.00% | -1.78% | -1.48% | -1.16% | -0.98% | -0.95% | -0.98% | -0.32% | 0.26% |

| [m/s] | Original | TAD #1 | TAD #2 | TAD #3 | TAD #4 | TAD #5 | TAD #6 | TAD #7 | TAD #8 | TAD #9 |

| 5 | 2.68 | 2.79 | 2.77 | 2.75 | 2.71 | 2.68 | 2.66 | 2.61 | 2.55 | 2.54 |

| 6 | 5.03 | 5.05 | 5.09 | 5.07 | 5.02 | 5.02 | 5.00 | 4.97 | 4.90 | 4.89 |

| 7 | 7.20 | 7.15 | 7.23 | 7.27 | 7.22 | 7.18 | 7.17 | 7.14 | 7.07 | 7.06 |

| 8 | 9.18 | 8.93 | 9.10 | 9.20 | 9.30 | 9.18 | 9.17 | 9.14 | 9.06 | 9.05 |

| 9 | 11.10 | 10.61 | 10.73 | 11.00 | 11.10 | 11.11 | 11.11 | 11.09 | 11.03 | 11.01 |

| 10 | 12.99 | 12.26 | 12.48 | 12.66 | 12.92 | 12.98 | 13.06 | 13.05 | 13.01 | 12.98 |

| 11 | 14.88 | 13.96 | 14.27 | 14.19 | 14.71 | 14.79 | 14.92 | 15.04 | 15.02 | |

| 12 | 16.76 | 15.70 | 16.18 | 15.81 | 16.38 | 16.65 | 16.74 | 17.00 | 17.08 | 17.06 |

| 13 | 17.96 | 16.89 | 17.44 | 16.95 | 17.44 | 17.86 | 17.97 | 18.27 | 18.43 | 18.44 |

| [m/s] | Original | TAD #1 | TAD #2 | TAD #3 | TAD #4 | TAD #5 | TAD #6 | TAD #7 | TAD #8 | TAD #9 |

| 5 | -1.99 | -1.72 | -1.85 | -1.85 | -1.87 | -1.98 | -2.01 | -2.07 | -2.14 | -2.13 |

| 6 | -0.50 | -0.35 | -0.43 | -0.41 | -0.43 | -0.50 | -0.51 | -0.53 | -0.57 | -0.54 |

| 7 | 2.17 | 2.22 | 2.18 | 2.18 | 2.16 | 2.14 | 2.14 | 2.17 | 2.16 | 2.17 |

| 8 | 4.87 | 4.85 | 4.90 | 4.88 | 4.69 | 4.84 | 4.83 | 4.85 | 4.81 | 4.82 |

| 9 | 7.25 | 7.14 | 7.27 | 7.31 | 7.25 | 7.20 | 7.21 | 7.23 | 7.17 | 7.18 |

| 10 | 9.38 | 9.06 | 9.25 | 9.42 | 9.49 | 9.36 | 9.36 | 9.36 | 9.32 | 9.31 |

| 11 | 11.43 | 10.84 | 10.97 | 11.35 | 11.42 | 11.41 | 11.44 | 11.43 | 11.39 | 11.38 |

| 12 | 13.44 | 12.57 | 12.82 | 13.01 | 13.40 | 13.38 | 13.48 | 13.51 | 13.47 | 13.45 |

| 13 | 15.46 | 14.37 | 14.72 | 14.63 | 15.28 | 15.32 | 15.43 | 15.61 | 15.60 | 15.58 |

| [m/s] | Original | TAD #1 | TAD #2 | TAD #3 | TAD #4 | TAD #5 | TAD #6 | TAD #7 | TAD #8 | TAD #9 |

| 5 | -0.94 | -0.70 | -0.81 | -0.81 | -0.84 | -0.93 | -0.96 | -1.02 | -1.08 | -1.08 |

| 6 | 0.13 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.03 | -0.04 | -0.05 |

| 7 | 1.42 | 1.58 | 1.53 | 1.52 | 1.48 | 1.43 | 1.39 | 1.33 | 1.26 | 1.25 |

| 8 | 2.88 | 2.91 | 2.91 | 2.92 | 2.91 | 2.88 | 2.87 | 2.87 | 2.83 | 2.84 |

| 9 | 5.25 | 5.14 | 5.20 | 5.20 | 5.16 | 5.17 | 5.20 | 5.28 | 5.29 | 5.30 |

| 10 | 7.92 | 7.74 | 7.88 | 7.96 | 7.81 | 7.87 | 7.88 | 7.91 | 7.88 | 7.90 |

| 11 | 10.19 | 9.74 | 9.93 | 10.18 | 10.24 | 10.15 | 10.17 | 10.20 | 10.15 | 10.16 |

| 12 | 12.34 | 11.60 | 11.80 | 12.13 | 12.31 | 12.31 | 12.36 | 12.38 | 12.36 | 12.35 |

| 13 | 14.45 | 13.46 | 13.74 | 13.86 | 14.35 | 14.32 | 14.47 | 14.56 | 14.54 | 14.53 |

| [m/s] | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| TAD #3 | 2.58% | 0.75% | 0.99% | 0.21% | -0.87% | -2.58% | -4.66% | -5.65% | -5.61% |

| TAD #6 | -1.02% | -0.67% | -0.39% | -0.04% | 0.11% | 0.51% | 0.25% | -0.13% | 0.10% |

| TAD #7 | -2.58% | -1.26% | -0.80% | -0.45% | -0.07% | 0.41% | 1.03% | 1.44% | 1.76% |

| TAD #8 | -5.06% | -2.61% | -1.76% | -1.22% | -0.61% | 0.12% | 0.92% | 1.92% | 2.64% |

| [m/s] | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| TAD #2 | 7.23% | 13.50% | 0.51% | 0.42% | 0.32% | -1.40% | -4.01% | -4.64% | -4.78% |

| TAD #3 | 7.26% | 17.61% | 0.53% | 0.07% | 0.82% | 0.42% | -0.65% | -3.26% | -5.38% |

| TAD #6 | -0.64% | -1.40% | -1.13% | -0.91% | -0.58% | -0.22% | 0.11% | 0.27% | -0.20% |

| TAD #7 | -4.01% | -5.06% | -0.08% | -0.56% | -0.33% | -0.22% | -0.02% | 0.49% | 0.95% |

| TAD #8 | -7.23% | -12.76% | -0.34% | -1.31% | -1.06% | -0.64% | -0.37% | 0.16% | 0.88% |

| [m/s] | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| TAD #1 | 25.19% | 175.35% | 11.56% | 1.04% | -2.09% | -2.25% | -4.40% | -6.02% | -6.88% |

| TAD #3 | 13.58% | 95.81% | 7.10% | 1.13% | -0.77% | 0.53% | -0.09% | -1.73% | -4.11% |

| TAD #4 | 10.83% | 67.03% | 4.43% | 1.00% | -1.70% | -1.39% | 0.49% | -0.26% | -0.69% |

| TAD #6 | -1.71% | -18.39% | -1.66% | -0.53% | -0.79% | -0.50% | -0.17% | 0.16% | 0.14% |

| TAD #7 | -8.24% | -74.15% | -5.86% | -0.59% | 0.63% | -0.12% | 0.04% | 0.30% | 0.77% |

| TAD #8 | -15.12% | -132.05% | -11.24% | -2.01% | 0.80% | -0.46% | -0.37% | 0.15% | 0.61% |

|

| TAD #1 | TAD #2 | TAD #3 | TAD #4 | TAD #5 | TAD #6 | TAD #7 | TAD #8 | TAD #9 | |

| max In | 5.7% | 7.7% | 8.9% | 6.2% | 7.6% | 7.3% | 7.1% | 4.8% | 6.7% |

| max Red | -2.8% | -5.9% | -5.0% | -3.2% | -2.5% | -1.1% | -9.9% | -4.8% | -4.7% |

| 8.4% | 13.6% | 13.9% | 9.4% | 10.1% | 8.3% | 17.0% | 9.6% | 11.4% | |

| 2.9% | 1.8% | 3.9% | 3.1% | 5.0% | 6.2% | -2.8% | 0.1% | 2.0% |

| [m/s] | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 0.447 | 0.484 | 0.435 | 0.370 | 0.314 | 0.268 | 0.231 | 0.200 | 0.174 | |

| 0.464 | 0.489 | 0.440 | 0.377 | 0.315 | 0.270 | 0.233 | 0.204 | 0.180 | |

| ln [%] | 3.83 | 1.05 | 1.13 | 1.76 | 0.13 | 0.63 | 1.08 | 1.90 | 3.27 |

| [m/s] | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 0.817 | 0.793 | 0.617 | 0.490 | 0.401 | 0.336 | 0.286 | 0.245 | 0.212 | |

| 0.851 | 0.811 | 0.626 | 0.512 | 0.407 | 0.338 | 0.286 | 0.247 | 0.215 | |

| ln [%] | 4.11 | 2.33 | 1.36 | 4.45 | 1.30 | 0.62 | 0.11 | 0.69 | 1.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).